A Corpus Linguistic Investigation of Vocabulary-based

Discourse Units in University Registers

1

Douglas Biber

Northern Arizona University

Eniko Csomay

San Diego State University

James K. Jones and Casey Keck

Northern Arizona University

Abstract

The present study introduces an approach that combines corpus-linguistic and discourse-

analytic perspectives to analyze the discourse patterns in a large multi-register corpus.

The primary goals of the study were to identify Vocabulary-Based Discourse Units

(VBDUs) using computational techniques, and to describe the basic types of VBDUs as

distinguished by their primary linguistic characteristics, using Multi-Dimensional

analytical techniques. The secondary goals were to compare the distributional patterns of

spoken and written academic registers in their reliance on the different VBDU types, and

to illustrate the analysis of the internal organization of a text as sequences of VBDUs. The

three major registers analyzed in this study – university classroom teaching, university

textbooks, and academic research articles – represent a continuum in the extent to which

VBDUs are explicitly marked by surface/textual features.

1 Introduction

Over the past 30 years, there has been considerable interest in the linguistic

characteristics of texts and discourse. Research in this area has been carried out

from two major perspectives: one focusing on the surface linguistic

characteristics of texts and registers, and the other focusing on the internal

discourse organization of texts. Studies of the first type have usually been

quantitative, and in more recent years, they have been carried out on large text

corpora using the techniques of corpus linguistics; these studies often compare

the linguistic characteristics of texts from different spoken and written registers

(e.g., Prince 1978; Schiffrin 1981; Thompson and Mulac 1991; Fox and

Thompson 1990; Granger 1983; Collins 1991, 1995; Tottie 1991; Mair 1990;

Meyer 1992; Biber et al. 1999; Kennedy 1998; Biber et al. 1998). Studies of the

second type have usually been qualitative and based on detailed analyses of a

Douglas Biber et al.

54

small number of texts; these studies usually focus on the internal structure of texts

from a single register, such as written narratives or scientific research articles

(e.g., Mann et al. 1992; Hoey 2001; Bhatia 1993; Swales 1990; Paltridge 1997).

Surprisingly, few studies have attempted to combine these two research

perspectives (though see, for example, Henry and Roseberry 2001; Upton and

Connor 2001; Csomay 2002, forthcoming; Kanoksilapatham 2003). On the one

hand, most quantitative studies of text corpora have focused on lexical and

grammatical features, generally ignoring higher-level discourse structures or

other aspects of discourse organization. On the other hand, most qualitative

discourse analyses have focused on the analysis of discourse patterns in a small

number of texts from a single register, but they have not provided tools for

empirical analyses that can be applied on a large scale across a number of

registers. As a result, we know little at present about the general patterns of

discourse organization across spoken and written registers:

In comparison with the impressive strides corpus linguistics has made in

the fields of lexicography, grammatical description, register studies etc,

it has had relatively little to say in describing features of discourse [and]

the rhetorical aspects of texts. [Call for papers; Camerino conference on

Corpora and Discourse; September 2002]

One analytical issue for any attempt to combine corpus-linguistic and discourse-

analytic research perspectives is to decide on a unit of analysis with a linguistic

basis. In previous corpus-based studies, the unit of analysis has been the 'text',

such as a complete book, research article, or newspaper article. However, there is

often extensive linguistic variation within a text, associated with internal shifts in

communicative task, purpose, and topic. In some cases, text-internal topic/task

units can be readily identified, because they are marked by sections (in academic

articles) or chapter breaks (in textbooks). In other cases, though, it is difficult to

identify topic/task units, especially in spoken texts.

In the present study, the unit of analysis is the Vocabulary-based

Discourse Units (VBDUs), a topically coherent stretch of discourse identified on

a linguistic basis. In particular, we adapt previously established techniques from

computational linguistics (TextTiling; see Section 3 below) to automatically

identify VBDUs, based on the word use patterns within a text. In brief, TextTiling

is a technique that identifies stretches of discourse that are maximally dissimilar

in their vocabulary, based on the assumption that a shared set of words is used

repeatedly within a VBDU, while different sets of words are used from one

VBDU to the next.

The primary goals of the study are to: 1) identify and describe the basic

types of VBDUs, as distinguished by their primary linguistic characteristics; 2) to

compare spoken and written academic registers in their reliance on the different

VBDU types; and 3) to explore the internal organization of texts, as sequences of

VBDUs. To achieve these goals, we identify the VBDUs in a large multi-register

corpus of texts using TextTiling techniques. We then analyze the linguistic

Vocabulary-based Discourse Units in University Registers

55

characteristics of each VBDU, using Multi-dimensional Analysis (see Biber

1988, 1995, 2003). In the present paper, we briefly describe the analytical

techniques and illustrate the kinds of research findings that result from this

approach, based on analysis of three university registers: classroom teaching,

textbooks, and academic research articles.

2

Overview of Analytical Steps

To achieve the major goals listed above, five analytical steps are required:

(1) Identify all Vocabulary-based Discourse Units (VBDUs) in a large,

multi-register corpus, using TextTiling

(2) Analyze the linguistic characteristics of each VBDU, using Multi-

Dimensional Analysis

(3) Identify and interpret the basic VBDU Types, using Cluster Analysis

(4) Analyze the preferred VBDU types in each register

(5) Analyze the structure of particular texts as sequences of VBDU Types

The study reported here is based on analysis of texts from two major corpora: the

T2K-SWAL Corpus (TOEFL 2000 Spoken and Written Academic Language

Corpus; see Biber et al. 2002; Biber, Conrad et al. forthcoming), and the LSWE

Corpus (Longman Spoken and Written English Corpus; see Biber et al. 1999,

Chapter 1). Specifically, we focused on three registers: classroom teaching,

textbooks, and academic research articles (see Section 3 below for more details

on the sub-corpora used for analysis).

These registers represent three of the most important kinds of language

that students encounter in normal university life, ranging from the spoken

presentation of information in classroom contexts, to the highly edited and

specialized presentation of information in academic research articles. For our

purposes here, these registers also represent important differences in the explicit

marking of discourse units, ranging from formally marked sections in research

articles (e.g., ‘Introduction’, ‘Methods’, ‘Results’, ‘Discussion’) to more gradual

transitions between topics in classroom teaching. For this reason, we expected

that these three registers would provide an excellent test of the usefulness of this

analytical approach for large-scale corpus-based analyses of discourse structure.

3 Automatic

Identification

of

Vocabulary-based Discourse Units:

TextTiling

In the present study, we adapt Hearst’s (1994, 1997) TextTiling procedure to

automatically identify Vocabulary-Based Discourse Units. Conceptually, this is a

quantitative procedure that compares the words used in adjacent segments of a

text. If the two segments use the same vocabulary to a large extent, we conclude

that they belong to a single discourse unit. In contrast, when the two segments are

Douglas Biber et al.

56

maximally different in their vocabulary, we conclude that they are from different

Vocabulary-based Discourse Units (VBDUs). VBDU boundaries are marked

between text segments that are maximally different in their use of vocabulary.

For the present study, VBDUs were automatically identified in the

corpus with a computer program. The program processed texts through a 100-

word “window.” As the window moves through the text one word at a time, the

program compares the first 50 words in the window with the second 50 words.

For example, we first compared the vocabulary in the text segment with words 1-

50 to the segment with words 51-100. The window would then advance one

word, comparing the text segment with words 2-51 to the segment with words 52-

101. Each comparison produced a similarity value – the TextTiling score – that

represented the extent to which the vocabulary in the two 50-word segments is

the same or different. A valley in the TextTiling score represents the point where

the two adjacent segments are maximally different in their vocabulary. For the

present analysis, we treated a 25% difference between the peak and valley of the

TextTiling score as a VBDU boundary.

To illustrate, the following text extract from a classroom session shows

the location of a VBDU boundary, corresponding to a shift in topic and purpose.

Each of these two VBDUs contains many words not found in the adjacent stretch

of discourse. For example, the first VBDU discusses culture and subculture, the

extent to which cultures are homogeneous, and issues and standards of right and

wrong. In contrast, in the adjacent VBDU, the instructor shifts to a summary

statement about radical individualism, the general beliefs of social commentators

and philosophy professors, and the overall goals that they are interested in this

semester. The TextTiling methodology simply compares the words in adjacent

stretches of discourse, automatically locating a VBDU boundary where discourse

segments are maximally different in the words that they use. Extract 1 below

illustrates how such shifts in vocabulary correspond to shifts in topic and/or

purpose.

Extract 1: Text extract from classroom teaching, showing the location of

VBDU boundaries. (The distinctive words in each VBDU are shown in

bold.)

Teacher:

Æ VBDU BOUNDARY

it's all relative to the individual culture. of course our culture today is

breaking apart. it's really very difficult to say we have a culture today.

we have just the collection of some cultures. so really we ought to say

that what's right is relative to the subculture. but then subcultures

probably are not as homogeneous as we tend to think we are. we're all

individuals and so even if I am a member of a subculture I'm probably

going to disagree on certain issues. so where does that put us? whether

it's right or wrong is relative too. there are no standards that are valid

beyond the individual person. if I think something is right, then it is

right for me. if I think something is wrong, it is wrong for me. if I think

Vocabulary-based Discourse Units in University Registers

57

it's right and you think it's wrong, then for you it is wrong, for me it is

right.

Æ VBDU BOUNDARY

and that's as far as we can go. that's radical individual relativism. and

many social commentators in the United States these days see such

radical individual relativism as a rampant disease that's about to destroy

our society and is usually thought by philosophy professors.… or people

in cultural studies any more. uh somehow we've survived, but uh we're not

really interested in that we're interested whether it's a correct theory or not.

and we're not really this semester interested whether it's a correct theory,

talk about that next semester. uh this semester we're interested in whether

or not Sartre should be called a relativist. and it certainly looks like it.

Æ VBDU BOUNDARY

Based on these techniques, we segmented all texts in our corpus into Vocabulary-

based Discourse Units. Table 1 shows the composition of the original corpus and the

number of VBDUs identified in each register.

Table 1: Corpus used for the analysis

Register

# of texts

# of Words

# of VBDUS

Classroom teaching

176

1,130,000

5,675

Textbooks

87

713,000

3,033

Research articles

256

657,000

3,002

Table 2 shows that VBDUs are on average around 200 words long in each

register, with the longest VBDUs being around 1,000 words. VBDUs in

classroom teaching and research articles are very similar in length, while some

textbook VBDUs are slightly longer. (We excluded all VBDUs shorter than 100

words from the quantitative analyses, because the quantitative distribution of

linguistic features cannot be reliably measured in short texts. Thus, the shortest

VBDUs in Table 2 are 101 words.)

Table 2: Descriptive statistics for VBDU length in each register

Register

N Mean

Std

Dev

Min

Max

Classroom teaching

5,675

198.8

82.6

101

775

Textbooks

3,033 234.5 108.7 101

1,084

Research articles

3,002

218.7

95.9

101

831

Douglas Biber et al.

58

4

Analyzing the Linguistic Characteristics of Each VBDU: Multi-

Dimensional Analysis

After the corpus had been segmented into VBDUs, it was necessary to undertake

a comprehensive linguistic analysis of each of these units. For this purpose, we

used Multi-Dimensional (MD) analysis. The MD analytical approach was

developed to identify and interpret the underlying patterns of linguistic variation

among registers in a corpus of texts (Biber 1988, 1995). The dimensions

identified in MD analysis have a linguistic/statistical basis, but they are

interpreted functionally. The linguistic content of each dimension is a group of

features (e.g., nouns, attributive adjectives, prepositional phrases) that co-occur

with a markedly high frequency in texts; these co-occurrence patterns are

identified statistically using factor analysis. The co-occurrence patterns are then

interpreted to assess their underlying situational, social, and cognitive functions.

In the present study, we applied the dimensions identified in an earlier

MD analysis of the T2K-SWAL Corpus. Table 3 summarizes the co-occurring

linguistic features that are grouped on each of the four dimensions in that

analysis. A full description of this MD analysis, and the interpretation of these

dimensions, is given in Biber (2003; see also Biber, Csomay et al. forthcoming).

For our analysis here, we computed ‘dimension scores’ for each VBDU

in our corpus (by summing the standardized frequencies for the features

comprising each of the four dimensions given in Table 3). Table 4 summarizes

the descriptive statistics for each register included in the study, with respect to

each of the four dimensions. For example, classroom teaching has a relatively

large positive score on Dimension 1 (mean dimension score of 2.1), reflecting a

dense use of the positive features on that dimension (contractions, demonstrative

pronouns, 1st person pronouns, present tense verbs, etc.) combined with the

relative absence of the negative features on Dimension 1 (nominalizations, longer

words, moderately common nouns, prepositional phrases, abstract nouns, etc.). In

addition, classroom teaching has moderately large positive scores for Dimension

3 (mean score of .3; ‘narrative orientation’) and Dimension 4 (mean score of .4;

‘academic stance’).

In contrast, textbooks and research articles have relatively large negative

scores for Dimension 1 (‘literate discourse’) and moderate negative scores for

Dimension 3 (non-narrative). These registers also have negative scores for

Dimension 2 (‘content-focused discourse’), with the research articles being more

marked on this dimension than textbooks.

Vocabulary-based Discourse Units in University Registers

59

Table 3: Summary of the four dimensions from the T2K-SWAL analysis

Dimension 1: Oral vs. literate discourse

Selected features with positive loadings:

demonstrative pronouns, pronoun it, 1st person pronouns, 2nd person

pronouns

present tense verbs, progressive aspect verbs, phrasal verbs,

activity verbs, mental verbs, communication verbs,

lexical bundles (pronoun-initial, WH-initial, verb-initial),

contractions, WH questions, clause coordination,

adverbial clauses, WH clauses, that-clauses, that-omission,

Selected features with negative loadings:

nominalizations, nouns, attributive adjectives, prepositional phrases,

agentless passives, by-passives, postnominal passives,

long words, type/token ratio, phrasal coordination,

WH relative clauses, to-clauses controlled by stance nouns

Dimension 2: Procedural vs. content-focused discourse

Selected features with positive loadings:

modal verbs (necessity, future), causative verbs, 2nd person pronouns,

to-clauses controlled by verbs of desire, conditional adverbial clauses

Selected features with negative loadings:

rare adjectives, rare nouns, rare adverbs, rare verbs,

simple occurrence verbs, to-clauses controlled by probability verbs

Dimension 3: Narrative orientation

Selected features with positive loadings:

pronouns: 3rd person, human nouns,

that-clauses controlled by non-factual verbs

communication verbs, past tense verbs

that-omission, that-clauses controlled by likelihood verbs

Dimension 4: Academic stance

Selected features with positive loadings:

that relative clauses, that-clauses controlled by stance nouns, adverbial

clauses

lexical bundles: preposition-initial, noun initial

adverbials: factual, attitudinal, likelihood

Douglas Biber et al.

60

Table 4: Dimension scores for VBDUs from each register

DIMENSION SCORES

Mean Std Dev

Min.

Max.

Classroom teaching:

Dim. 1: 'Oral vs. literate'

2.1

1.9

-6.2

10.8

Dim. 2: 'Procedural vs. content-

focused'

0.0 0.8 -5.2 3.7

Dim. 3: 'Narrative orientation'

0.3

1.4

-3.5

9.7

Dim. 4: 'Academic stance'

0.4

1.2

-4.2

10.0

Textbooks:

Dim. 1: 'Oral vs. literate'

-2.8

1.5

-9.9

5.1

Dim. 2: 'Procedural vs. content-

focused'

-0.7 1.0 -8.2 2.9

Dim. 3: 'Narrative orientation'

-0.3

1.2

-3.8

6.2

Dim. 4: 'Academic stance'

0.0

0.9

-3.3

8.9

Research articles:

Dim. 1: 'Oral vs. literate'

-3.2

0.9

-6.6

0.4

Dim. 2: 'Procedural vs. content-

focused'

-2.7 1.2 -10.4 1.0

Dim. 3: 'Narrative orientation'

-0.6

0.8

-3.4

5.0

Dim. 4: 'Academic stance'

-0.5

0.7

-1.9

4.7

5

The Basic VBDU Types: Cluster Analysis

The next step in the study is to identify the VBDU types that are well defined

linguistically. A second multivariate statistical technique – Cluster Analysis – is

used to group VBDUs into 'clusters' on the basis of shared linguistic

characteristics: the VBDUs grouped in a cluster are maximally similar

linguistically, while the different clusters are maximally distinguished. The

dimensions of variation (see Section 4 above) are used as linguistic predictors for

the clustering of VBDUs. These clusters are then interpreted as 'VBDU types'

(see also Biber 1989, 1995).

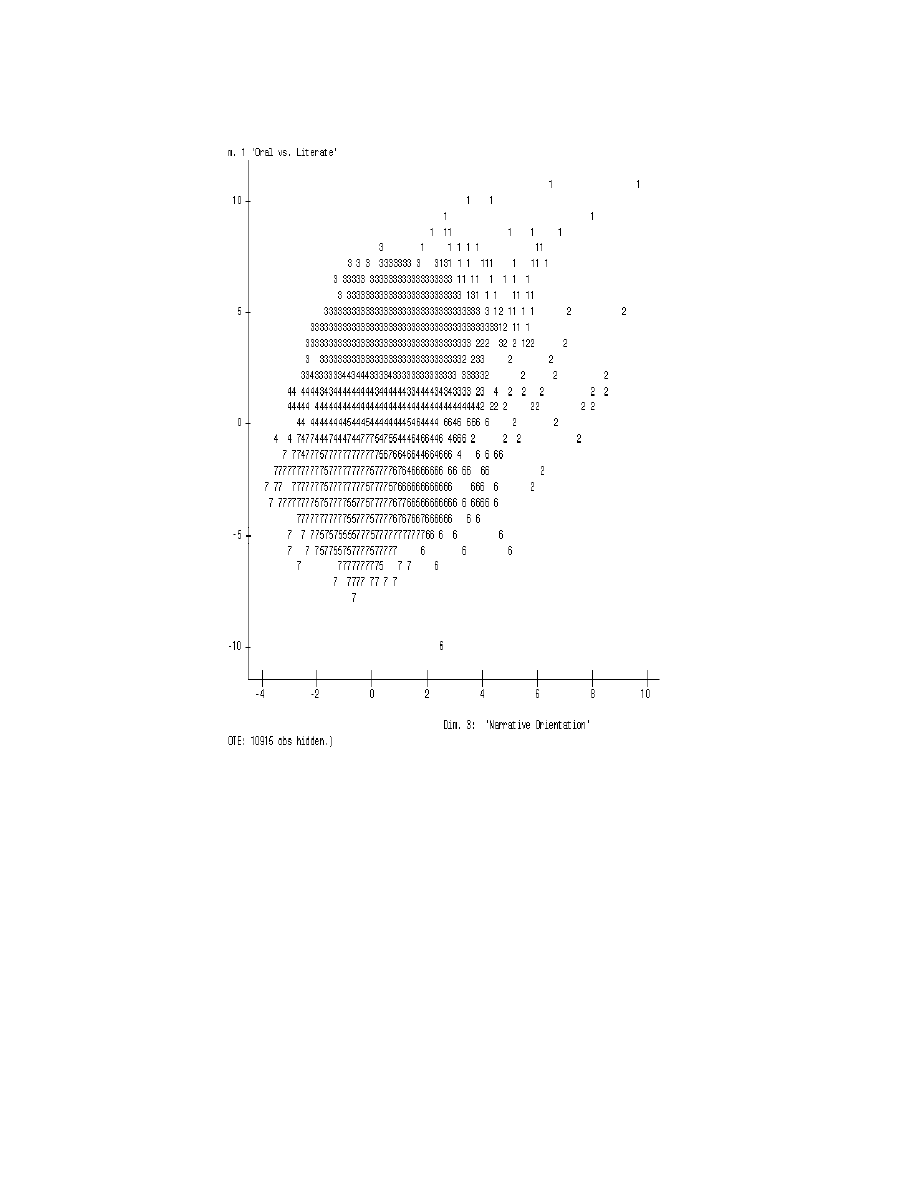

The methodology in this analytical step can be illustrated conceptually

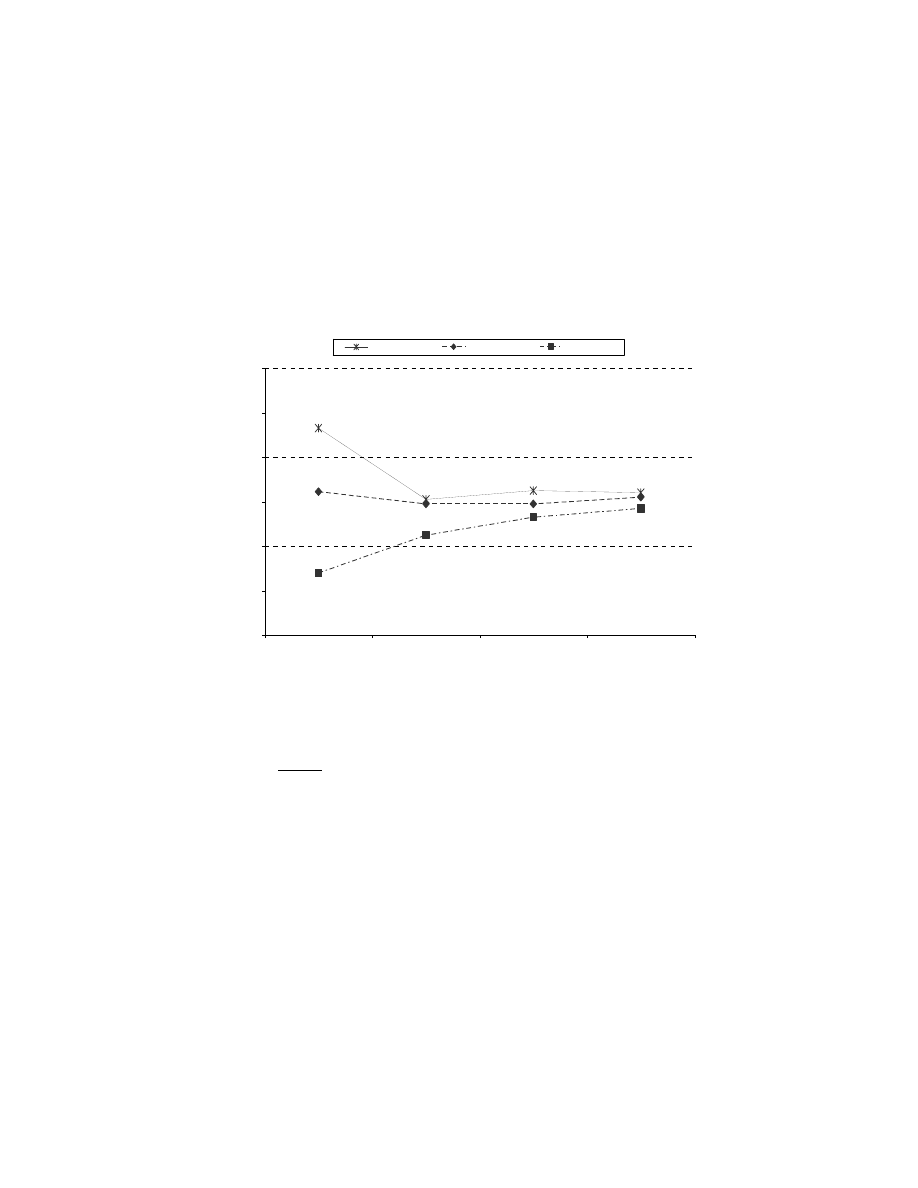

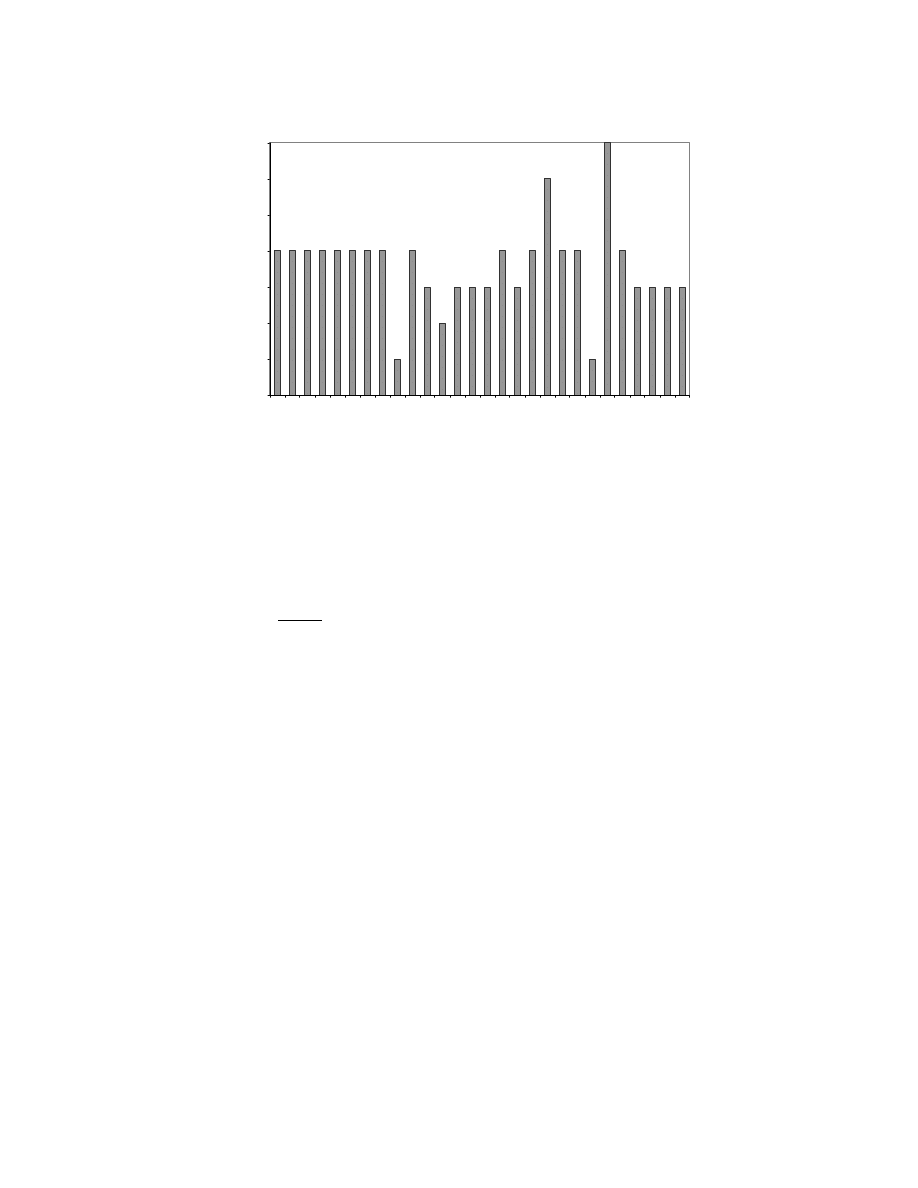

by the 2-dimensional plot in Figure 1. Each point on Figure 1 represents a VBDU,

plotting the scores for that VBDU on two dimensions: 1 and 3. The numbers in

the figure show the cluster number for each VBDU, based on the results of the

cluster analysis. VBDUs can be grouped together based on dimension scores. For

example, the VBDUs labelled with a '1' on Figure 1 all have large positive scores

on Dimension 1 (the vertical axis) and large positive scores on Dimension 3 (the

Vocabulary-based Discourse Units in University Registers

61

horizontal axis). Note that the grouping process here is based on the dimension

scores, regardless of register category.

Figure 1: Distribution of VBDUs along Dimensions 1 and 3, by cluster

Douglas Biber et al.

62

Cluster analysis performs this grouping statistically, based on the scores

for all four dimensions in a VBDU. Figure 1 shows the distribution across only

two dimensions (1 and 3); these two dimensions were chosen because they

provide a good visual display of how the VBDUs within each cluster are grouped

based on their dimension scores. However, the actual cluster analysis uses all four

dimension scores to identify the groupings of VBDUs that are maximally similar

in their linguistic characteristics.

Seven clusters were identified based on the groupings of the cluster

analysis produced by our statistical package (SAS).

2

Figure 1 shows the

distribution of clusters in only a 2-dimensional space, whereas the cluster analysis

actually considered a 4-dimensional space. It turns out that the other two

dimensions are important in defining some clusters. For example, Cluster 5 is not

sharply delimited in terms Dimensions 1 and 3, but all VBDUs in this cluster

have large negative scores on Dimension 2 ('content-focused').

Table 5: Cluster mean scores for each dimension

Cluster Frequency Dim. 1 Dim. 2 Dim. 3 Dim. 4

'Oral vs. 'Procedural vs. 'Narrative'

'Academic

Literate' Content-focused' Stance'

1: Extremely oral + narrative

77 6.8

-0.2

4.4

0.0

2: Oral + narrative + academic stance

60 1.9

-0.3

4.8

4.5

3: Oral

3059 3.3

0.1

0.5

0.4

4: Unmarked

2814 0.4

-0.1

-0.1

0.2

5: Literate + extreme content-focused

446 -3.2

-4.7

-0.6

-0.6

6: Literate + moderate content-focused + moderate narrative + moderate

academic stance

369 -2.5

-1.3

1.8

1.9

7: Literate + moderate content-focused

4885 -3.2

-1.5

-0.7

-0.3

Table 5 provides a descriptive summary of the cluster analysis results. This table

shows the number of VBDUs grouped into each cluster, and the mean score for

each cluster for each dimension. The clusters differ notably in their

distinctiveness: the smaller clusters are more specialized and more sharply

distinguished linguistically. For example, Cluster 2 has only 60 VBDUs;

linguistically, the VBDUs grouped in Cluster 2 have moderate positive scores on

Dimension 1 ('oral'); large positive scores on Dimension 3 ('narrative'); and large

Vocabulary-based Discourse Units in University Registers

63

positive scores on Dimension 4 ('academic stance'). Clusters 1, 2, 5, and 6 are all

small, 'specialized' clusters. In contrast, Cluster 3, 4, and 7 are very large,

'general' clusters. For example, Cluster 4 has 2,814 VBDUs and is unmarked on

all four dimensions.

The clusters can be regarded as Discourse Unit Types (VBDU Types),

because each cluster represents a grouping of VBDUs with similar linguistic

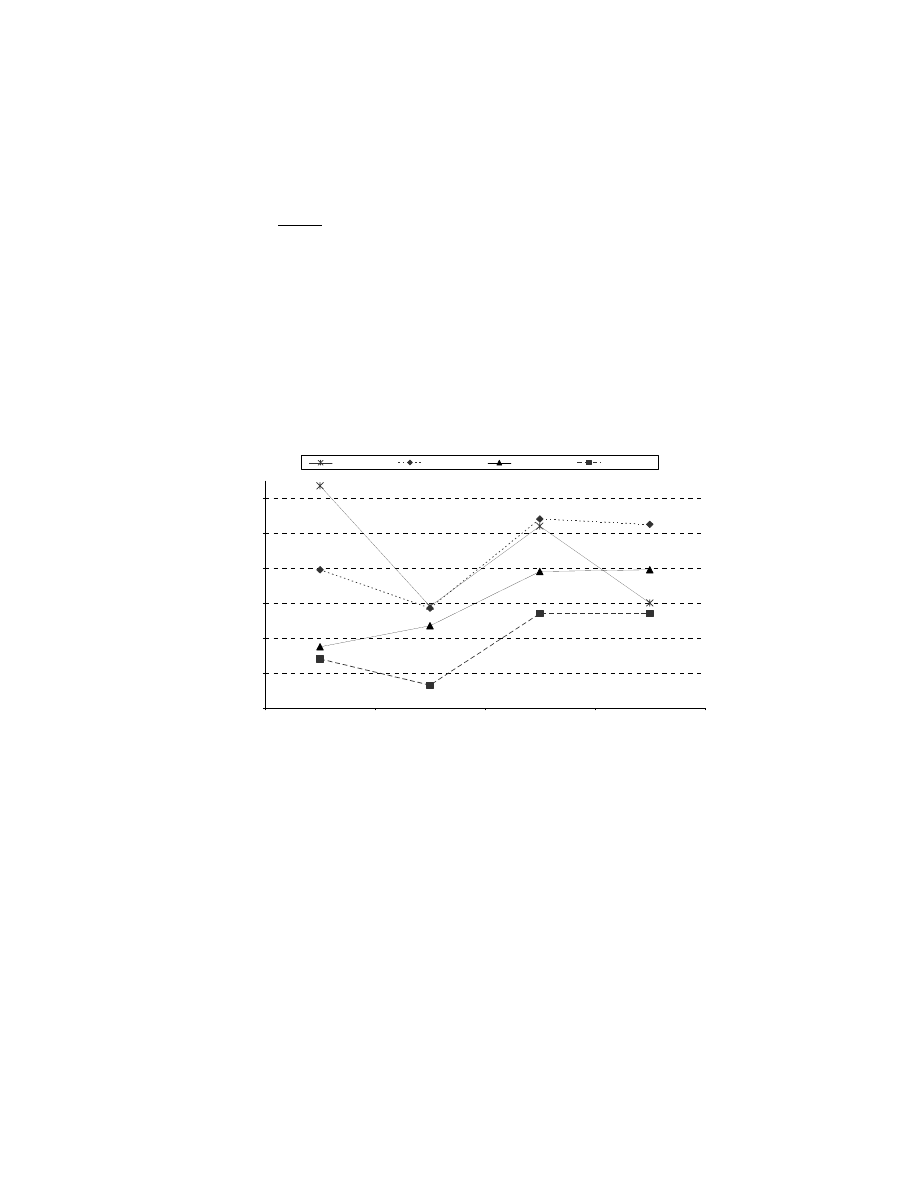

profiles. Figures 2 and 3 compare the linguistic characteristics of the seven types,

plotting their mean dimension scores. The 'general' VBDU types – 3, 4, and 7 –

are plotted in Figure 2. These three types are very large but not distinctive

linguistically: Figure 2 shows that these types are distinguished along Dimension

1, but they all have scores near 0.0 along Dimensions 2, 3, and 4. The following

text extracts show examples of a VBDU Types 3 and 4.

Multi-Dimensional profile for the general VBDU types

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

1

2

3

4

Dimensions

Di

m

ens

ion S

cor

e

VBDU Type 3

VBDU Type 4

VBDU Type 7

Figure 2: Multi-Dimensional profile for the general VBDU Types

Extract 2: VBDU Type 3 ‘Oral’

Teacher: many perhaps would appeal to things like the ten commandments.

well those are principles. “thou shalt not lie, thou shalt not uh kill”, these

are principles that tell you not to do certain sorts of things. and then if

people will appeal to them uh because they say these are the commands of

Douglas Biber et al.

64

God. Sartre would very much agree with (Kirky's) argue uh “thou shalt not

kill”, never? under no circumstances? under what circumstances? who

decides? what are the exceptions? what are not? it's not enough to know

that “thou shalt not kill”, you got to know when, where, to whom, etcetera.

and those details aren't supplied by the principle.

Extract 3: VBDU Type 4 ‘Unmarked’

Teacher: uh I've given you all a handout [unclear words] in her discussion,

some very brief descriptions of uh ethical principles that have been famous

throughout uh Western History. and I've raised the sorts of questions that

can be raised about them very briefly, so as to kind of give you the flavor of

why Sartre would claim that these principles really don't work, they are

failed ethical principles as it were. and I wont go into the detail of that any

more. I want to come quickly to the bottom line. Sartre thinks that the case

of the young Frenchman is typical not just of young Frenchmen during the

war, but of human reality. that this is not a special case, it's just a dramatic

case, which bares uh drives home the point. all of us are in the predicament

of making decisions everyday about what we should do. and most of us

probably think there is a right and a wrong (only). some ethical principle

out there which will tell us what to do.

Multi-Dimensional profile for the specialized VBDU types

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

1

2

3

4

Dimensions

D

im

ens

ion S

cor

e

VBDU Type 1

VBDU Type 2

VBDU Type 6

VBDU Type 5

Figure 3: Multi-Dimensional profile for the specialized VBDU Types

Vocabulary-based Discourse Units in University Registers

65

In contrast, the specialized VBDU types, plotted in Figure 3, are much

more distinctive linguistically. Type 1 is extremely 'oral' (Dim. 1), and has a

strong narrative orientation (Dim 3). Type 2 is moderately 'oral' (Dim. 1) with a

strong narrative orientation (Dim. 3) and a strong emphasis on academic stance

(Dim. 3). Type 5 is strongly 'literate' (Dim. 1) and very strongly content-focused

(Dim. 2). Finally, Type 6 is 'literate' (Dim. 1) with a moderate content-focus

(Dim. 2), narrative orientation (Dim. 3) and emphasis on academic stance (Dim.

4).

The text extracts below show examples of three of the specialized

VBDU Types (1, 5, and 6).

Extract 4: VBDU Type 1 ‘Extreme oral, narrative’ from a class session

Teacher: and I suppose that would be the case here, it's permissible for him

to stay home with his mother no one would say he did the wrong thing, it's

permissible for him to go and fight the Nazis, no one would say he did the

wrong thing if he did that. But now our young man is faced with the fact

that OK it's permissible to this, it's permissible to do that, but what do I do?

knowing it's permissible is not telling me to do it. I have to choose. I have

to decide between those options, both of which are permissible.

Student: well many times one has to decide on grounds [unclear words]

right or wrong, it's what one prefers or what you know I don't know

[unclear words]

Teacher: well

Student: [unclear words] ethics should always have a clear answer to every

situation?

Teacher: one would hope, but uh probably in vain. let's move on and see

what Sartre has to say about this.

The positive Dimension 1 and Dimension 3 features are underlined.

Extract 5: VBDU Type 5 ‘Literate, extreme content-focused’ from

academic prose

…. PCNA is an acidic nuclear protein, expression of which is directly

correlated with rates of cell proliferation and DNA synthesis. The

monoclonal antibody PC10 will "recognise"PCNA in conventionally fixed

and processed histological material. The tissue sample of the excised

pancreas was placed in buffered formalin for two to four hours and

transferred to 75% ethanol. Tissue was processed in chloroform and

embedded in wax before 4 m sections were cut. Sections were dewaxed

and taken down through graded alcohols; endogenous peroxidase activity

was blocked by incubating the sections in 3% hydrogen peroxide and

methanol for one hour. After washing in PBS, pH 7.4, each section was

treated with a drop of primary antibody (1:20 dilution in PBS). After

overnight incubation at 4C, the sections were washed in PBS,0.1% bovine

Douglas Biber et al.

66

serum albumin (BSA), and Tris-BSA. The second layer antibody,

biotinylatd goat anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA,

USA) was applied at a dilution of 1:50 and incubated for two hours at room

temperature. After washing in PBS, streptavidin-peroxidase (Jackson

Immunonuclear Laboratories, Westgrove, PA, USA) was applied to the

sections at a 1:5000 dilution in PBS with 1% BSA for 30 minutes at room

temperature. Diamino-benzidine-hydrogen peroxide was employed at a

chromogen, and a light haematoxylin counterstain was used. The PCNA

labelling index was estimated from a count of 2000 exocrine acinar cells …

The negative Dimension 1 features are underlined.

Extract 6: VBDU Type 6 ‘Literate, content-focused, narrative, academic

stance’ from a textbook

Given the cultural differences in the world and the tendency of all of us to

view our own way of life as "natural," it is no wonder that travellers often

feel culture shock, personal disorientation that comes from experiencing an

unfamiliar way of life. The box on page 64 presents one researcher's

encounter with culture shock.

December 1, 1994, Istanbul, Turkey.

‘Harbors everywhere, it seems, have two things in common: ships and cats.

Istanbul, the tenth port on our voyage, is awash with felines, prowling

about in search of an easy meal. People may change from place to place,

but cats do not. No cultural trait is inherently "natural" to humanity, even

though most people around the world view their own way of life that way.

What is natural to our species is the capacity to create culture. Every other

form of life - from ants to zebras - behaves in uniform, species-specific

ways. To a world traveller, the enormous diversity of human life stands out

in contrast to the behaviour of, say, cats, which is the same everywhere.

This uniformity follows from the fact that most living creatures are guided

by instincts, biological programming over which animals have no control.

A few animals - notably chimpanzees and related primates - have the

capacity for limited culture; they can use tools and teach simple skills to

their offspring.’

6

The Distribution of VBDU Types across Registers

Table 6 shows how the VBDU types cut across registers: the three registers in our

study utilize each of the seven types to differing extents. Research articles never

use Types 1-3, and they rarely use Type 4, but Types 5-7 are all relatively

common in this register. However, classroom teaching and textbooks use all

seven types. Classroom teaching rarely uses Type 5, but the remaining six types

are all used to some extent in this register. (The single Type 5 text in classroom

teaching is actually an instructor reading a passage from a written text.)

Vocabulary-based Discourse Units in University Registers

67

Textbooks are similar in using the full range of types, but they show different

preferences: Types 1 and 2 are rare in this register, while Types 3-7 all occur to

some extent. These patterns show that the VBDU type categories reflect different

topical and rhetorical considerations, which cut across the register categories. For

example, classroom teaching can include interactive, conversational Vocabulary-

based Discourse Units (Type 1) as well as monologues with a dense informational

purpose (Type 6). A full interpretation of the VBDU Types requires detailed

consideration of the functions of each type in each register.

7

Sequences of VBDU Types

Finally, it is possible to analyze the discourse structure of individual texts as

sequences of VBDUs, taking into account the VBDU Type of each unit. For

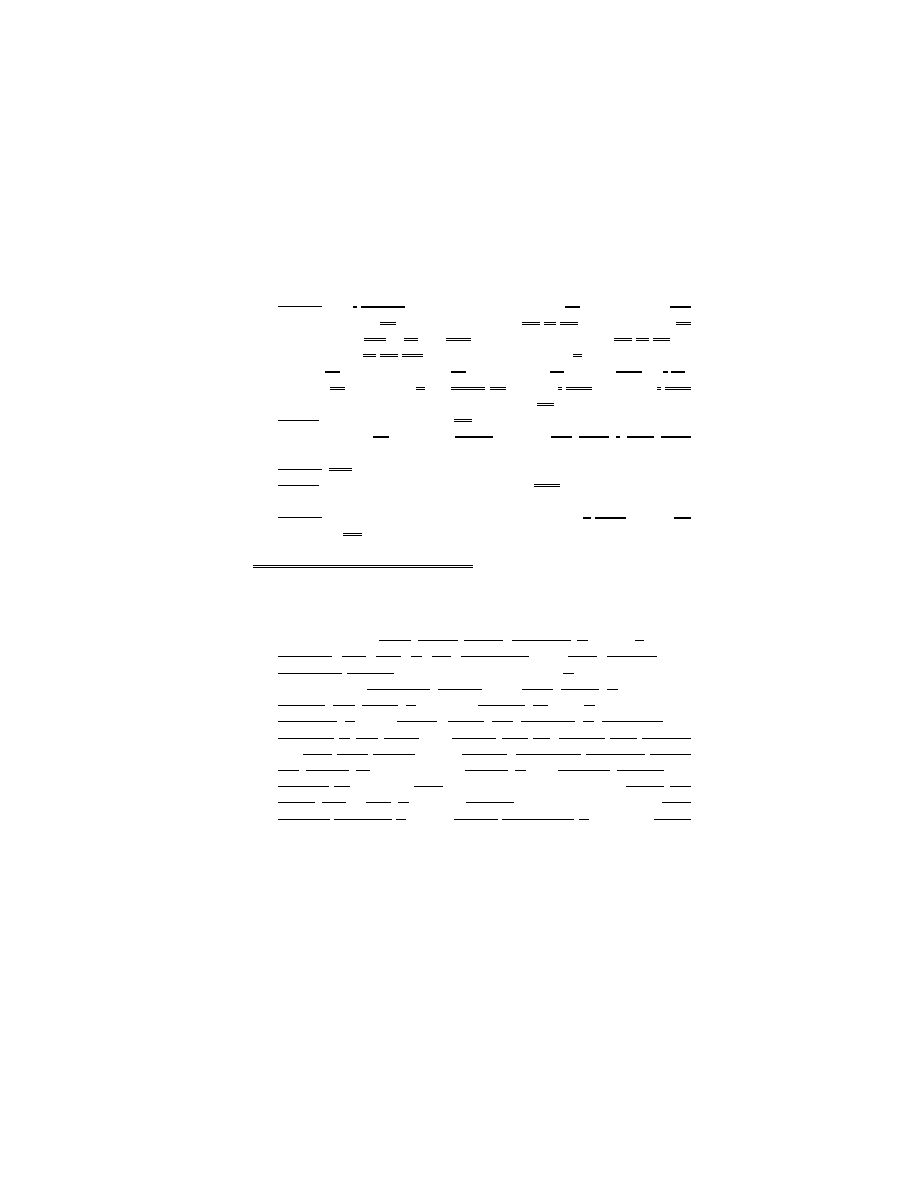

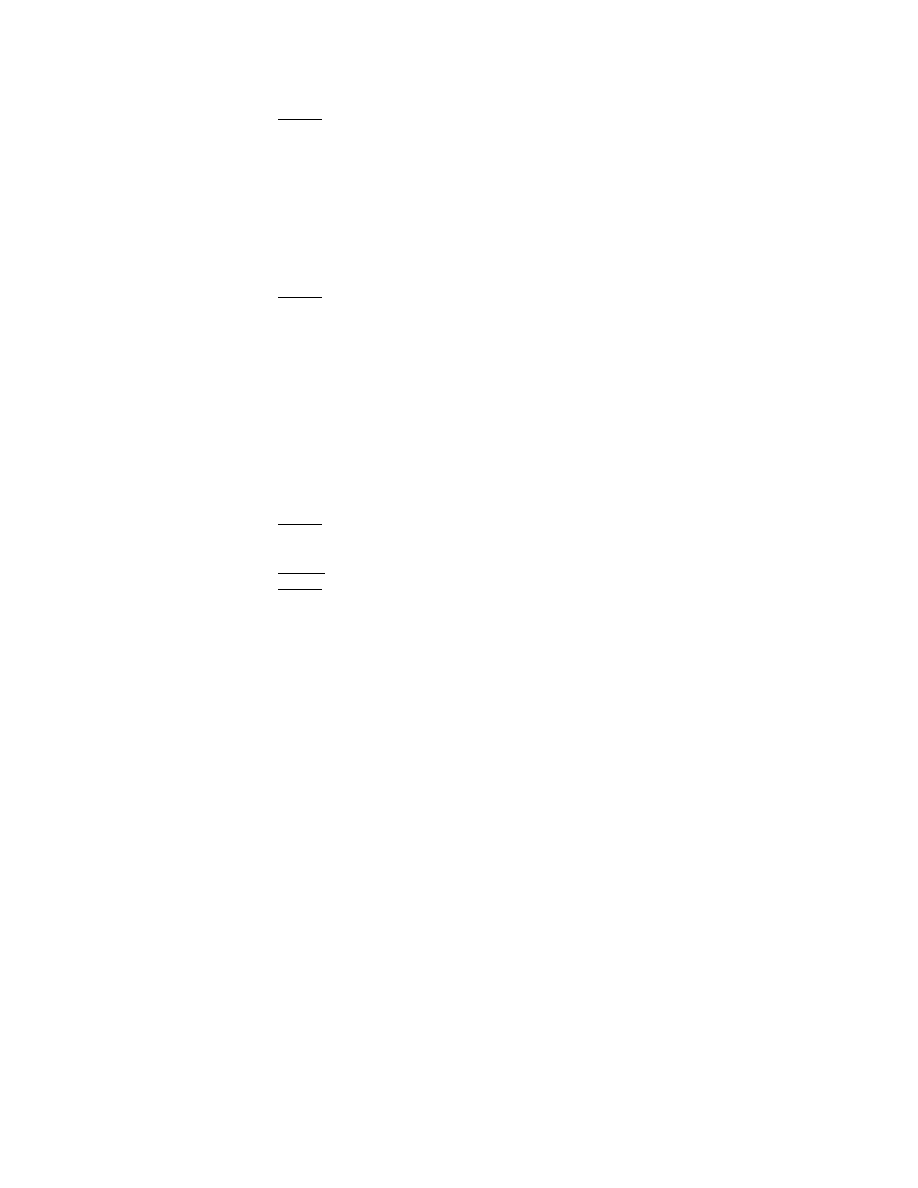

example, Figure 4 shows the progression of VBDUs in a classroom teaching text.

As the distribution across registers showed (Table 6), the majority of the class

sessions tend to rely on two general VBDU Types: ‘Oral’ (Type 3) and

‘Unmarked’ (Type 4). However, the other five VBDU Types are also present in

classroom talk.

The VBDU Type profile in Figure 4 demonstrates the distribution

pattern within a Philosophy class session. Besides the general VBDU Types

mentioned above, this class also uses VBDU Type 1 (‘Extremely oral narrative’),

as in VBDU Number 32, and Type 7 (‘Literate, content focused’), as in VBDU

Number 33. The variation in the VDBU Type reflects a change in linguistic

characteristics, and relates to a change in the communicative purposes of these

topically coherent discourse units.

Table 6: Distribution of VBDUs across DU Types (Clusters) and Registers

Register DU

type

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Total

Academic

Freq.

0

0

0

26

430

115

2,431

3,002

Percent 0.00 0.00

0.00

0.22 3.67 0.98 20.76

25.64

Row % 0.00 0.00

0.00

0.92 96.41 31.17 49.76

Col % 0.00 0.00

0.00

0.87 14.32 3.83 80.98

Classroom

Freq.

75

57

3,030

2,349

1

59

104 5,675

Percent 0.64 0.49 25.88 20.06 0.01 0.50

0.89

48.46

Row % 97.40 95.00 99.05

83.48 0.22 15.99

2.13

Col % 1.32 1.00 53.39

41.39 0.02 1.04

1.83

Textbooks

Freq.

2

3

29

439

15

195

2,350

3,033

Percent 0.02 0.03

0.25

3.75 0.13 1.67 20.07

25.90

Row % 2.60 5.00

0.95

15.60 3.36 52.85 48.11

Col % 0.07 0.10

0.96

14.47 0.49 6.43 77.48

Total

Freq.

77

60

3,059

2,814

446

369

4,485

11,710

Percent

0.66

0.51

26.12

24.03

3.81

3.15

41.72

100.00

Douglas Biber et al.

68

Figure 4: VBDU Type profile for a class lecture

The text extract below corresponds to the VBDU Numbers 32 to 35

illustrated in Figure 4. This text segment contains four consecutive VBDUs,

where each is a different type. VBDUs 32 and 33 are the same two discourse

units that we used to illustrate the TextTiling methodology in Section 3 above

(Extract 1).

Extract 7: Selected VBDUs from a class teaching session:

VBDU 32 = VBDU Type 1: Extremely oral + narrative

Teacher: it's all relative to the individual culture. of course our culture today

is breaking apart. it's really very difficult to say we have a culture today. we

have just the collection of some cultures. so really we ought to say that

what's right is relative to the sub-culture. but then subcultures probably are

not as homogeneous as we tend to think we are. we're all individuals and so

even if I am a member of a subculture I'm probably going to disagree on

certain issues. so where does that put us? whether it's right or wrong is

relative too. there are no standards that are valid beyond the individual

person. if I think something is right, then it is right for me. if I think

something is wrong, it is wrong for me. if I think it's right and you think it's

wrong, then for you it is wrong, for me it is right.

VBDU Type Profile for a class lecture

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

1

2

3

4

5

6

9

11 13 14 15 17 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 27 29 32 33 34 35 36 38 40

VBDU Number

V

BDU T

yp

e

Vocabulary-based Discourse Units in University Registers

69

VBDU 33 = VBDU Type 7: Literate + content-focused

Teacher: and that's as far as we can go. that's radical individual relativism.

and many social commentators in the United States these days see such

radical individual relativism as a rampant disease that's about to destroy our

society and is usually thought by philosophy professors. … or people in

cultural studies any more. uh somehow we've survived, but uh we're not

really interested in that we're interested whether it's a correct theory or not.

and we're not really this semester interested whether it's a correct theory,

talk about that next semester. uh this semester we're interested in whether

or not Sartre should be called a relativist. and it certainly looks like it.

VBDU 34 = VBDU Type 4: Unmarked

Teacher: after all, values are the result of my choices. my values are the

result of my choices. your values are the result of your choices. if that's not

relativism what is ? sounds like subjectivism. values are simply the result of

my choices, my preferences that sort of thing and makes values relative to

the individual person. so you could certainly argue the case that Sartre is

both a subjectivist and a relativist. at the end of the handout I raise a couple

of questions that I'd like you to think about. I'm not going to say what the

answer to these questions should be, but I would like you to consider

[unclear words]. is Sartre a subjectivist? what about his insistence that our

choices define for us a world and that we are totally responsible for this

world ? for Sartre choice is a very serious thing. when you choose a way of

life, a relationship to your life as he (would) put it

VBDU 35 = VBDU Type 3: Oral

Teacher: you're defining who you are and you're defining the world you

live in. you know when I go to what's the name of the ice cream store that

has fifty-five flavors?

Students: Baskin Robbins

Teacher: Baskin Robbins. when I go to Baskin Robbins and ask for the

strawberry, I'm not defining myself. I'm certainly not defining (them) the

world. When I make a Sartrian like choice of the world and of the self, it's

not a trivial matter such as taste for ice cream is trivial. It's ontologically

serious in that it shapes the nature of the world I see myself (in). When we

think of subjectivism we think that you know values are just like tastes.

The discourse structure of a text can be interpreted as sequences of VBDU types.

In the Philosophy class session in Extract 7, all VBDUs stay within the same

overall theme while each VBDU is different not only their linguistic features but,

correspondingly, in their communicative purposes.

VBDU 32 has features that had been associated with extremely oral,

narrative discourse. In this unit the teacher brings in a seemingly unrelated topic

to the overall theme. However, this ‘aside’ provides background to the main idea

presented in the next VBDU (33). By the extensive use of first and third person

Douglas Biber et al.

70

pronouns, and present tense, the teacher creates a shared space for discussion,

making the theme both more personable (narrative), and maybe more accessible

to the students. Hence, VBDU 32 serves as a niche for VBDU 33, where the

teacher puts the main proposition forward: “… that's radical individual relativism

… this semester we’re interested in whether or not Sartre should be called a

relativist ...”

In VBDU 34, the teacher elaborates on the notion proposed further,

providing definitions and explanations to the main idea presented in the previous

unit (VBDU 33, linguistically ‘Unmarked’). Finally, in VBDU 35, the linguistic

characteristics indicate oral discourse – quite similar to VBDU 32. Not

surprisingly, in this discourse unit, the teacher is not creating the background for

a proposition next but instead, he gives further support to the notions presented

and discussed earlier; hence, this unit functions as a follow up. He brings in

another real-life example, and as a conclusion to the topic, draws parallels

between the example and the notions presented and supported in the previous

units.

8 Conclusion

The present paper has introduced an approach to integrating the strengths and

goals of corpus analysis and discourse analysis. This approach allows the

consideration of the internal discourse structure of individual texts, but based on

generalizable units of analysis identified through empirical analysis of a large

corpus. We have outlined the kinds of findings possible through this approach,

considering three university registers: classroom teaching, textbooks, and

research articles.

In our on-going research, we are extending this research approach in

several ways. First, we have undertaken perceptual analyses to investigate

whether human raters reliably identify Vocabulary-based Discourse Units in texts

from different registers, and whether VBDUs correspond to the Vocabulary-based

Discourse Units identified by human raters. Second, we are extending the

computational techniques for segmenting texts to incorporate a range of linguistic

indicators in addition to vocabulary distributions. We are undertaking much more

detailed interpretations of the discourse unit types in each register. And finally,

we are studying how sequences of VBDU-types work together in different

registers, supporting different major rhetorical patterns.

Notes

1. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Camerino

conference on ‘Corpora and Discourse’ (September 2002), published in

the conference proceedings (Biber, Csomay et al. forthcoming).

Vocabulary-based Discourse Units in University Registers

71

2. The number of clusters is determined by peaks in the cubic clustering

criterion and the Pseudo-F statistic produced by SAS.

References

Bhatia, V.K. (1993), Analysing genre: Language use in professional settings,

New York: Longman.

Biber, D. (1988), Variation across speech and writing, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Biber, D. (1989), The typology of English texts, Linguistics, 27: 3-43.

Biber, D. (1995), Dimensions of register variation: A cross-linguistic perspective,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D. (2003), Variation among university spoken and written registers: A new

multi-dimensional analysis, in P. Leistyna and C. Meyer (eds), Corpus

analysis: Language structure and language use, Amsterdam: Rodopi,

pp. 47-70.

Biber, D., S. Conrad, and R. Reppen (1998), Corpus linguistics: Investigating

language structure and use, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D., S. Johansson, G. Leech, S. Conrad, and E. Finegan (1999), Longman

grammar of spoken and written English, London: Longman.

Biber, D., S. Conrad, R. Reppen, P. Byrd, and M. Helt (2002), Speaking and

writing in the university: A Multidimensional comparison, TESOL

Quarterly, 36: 9-48.

Biber, D., S. Conrad, R. Reppen, P. Byrd, M. Helt, V. Clark, V. Cortes, E.

Csomay, and A. Urzua (forthcoming), Representing language use in the

university: Analysis of the TOEFL 2000 Spoken and Written Academic

Language corpus, TOEFL Monograph Series, Princeton, NJ:

Educational Testing Service.

Biber, D., E. Csomay, J.K. Jones and C. Keck (forthcoming), Vocabulary-based

discourse units in university registers, in A. Partington, J. Morley, and L.

Haarman (eds), Corpora and discourse, Bern: Peter Lang.

Collins, P. (1991), Cleft and pseudo-cleft constructions in English, London:

Routledge.

Collins, P. (1995), The indirect object construction in English: An informational

approach, Linguistics, 33: 35-49.

Csomay, E. (2002), Episodes in university classrooms: A corpus-linguistic

investigation, Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Flagstaff, AZ: Northern

Arizona University.

Csomay, E. (forthcoming), A Multi-dimensional analysis of discourse segments

in university classroom talk, in A. Partington, J. Morley, and L.

Haarman (eds), Corpora and discourse, Bern: Peter Lang.

Fox, B.A. and S.A. Thompson (1990), A discourse explanation of the grammar of

relative clauses in English conversation, Language, 66: 297-316.

Granger, S. (1983), The 'be' + past participle construction in spoken English,

with special emphasis on the passive, Amsterdam: North Holland.

Douglas Biber et al.

72

Hearst, M.A. (1994), Multi-paragraph segmentation of expository texts,

Technical Report 94/790, Computer Science Division (EECS),

University of California, Berkeley.

Hearst, M.A. (1997), TextTiling: Segmenting text into multi-paragraph subtopic

passages, Computational Linguistics, 23 (1): 33-64.

Henry, A. and R.L. Roseberry (2001), A narrow-angled corpus analysis of moves

and strategies of the genre Letter of Application, English for Specific

Purposes, 20 (2): 153-167.

Hoey, M. (2001), Textual interaction, London: Routledge.

Kanoksilapatham, B. (2003), A Corpus-based investigation of biochemistry

research articles: Linking move analysis with multidimensional analysis,

Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Georgetown University: Washington,

DC.

Kennedy, G. (1998), An introduction to corpus linguistics, New York: Longman.

Mair, C. (1990), Infinitival complement clauses in English, New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Mann, W.C., C. Matthiessen, and S.A. Thompson (1992), Rhetorical structure

theory and text analysis, in W. Mann and S.A. Thompson (eds),

Discourse description: Diverse linguistic analyses of a fund-raising text,

Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp.

39-78.

Meyer, C. (1992), Apposition in contemporary English, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Paltridge, B. (1997), Genre, frames, and writing in research settings,

Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Prince, E.F. (1978), A comparison of Wh-clefts and It-clefts in discourse,

Schiffrin, D. (1981), Tense variation in narrative, Language, 57: 45-62.

Swales, J. (1990), Genre analysis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, S.A. and A. Mulac (1991), A quantitative perspective on the

grammaticization of epistemic parentheticals in English, in E.C.

Traugott and B. Heine (eds), Approaches to grammaticalization,

Volume II, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 313-329.

Tottie, G. (1991), Negation in English speech and writing: A study in variation,

San Diego: Academic Press.

Upton, T.A. and U. Connor (2001), Using computerized corpus analysis to

investigate the text linguistic discourse moves of a genre, English for

Specific Purposes, 20 (4): 313-329.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Investigations of White Layer Formation During Machining of Powder Metallurgical Ni Based ME 16 S

Partington A linguistic account of wordplay

[Mises org]Boetie,Etienne de la The Politics of Obedience The Discourse On Voluntary Servitud

a probalilistic investigation of c f slope stability

The Language of Internet 8 The linguistic future of the Internet

Endoscopic investigation of the Nieznany

13 161 172 Investigation of Soldiering Reaction in Magnesium High Pressure Die Casting Dies

8 95 111 Investigation of Friction and Wear Mechanism of Hot Forging Steels

Fundamnentals of dosimetry based on absorbed dose standards

End of the book TestB Units 1 14

Investigation of Barite Sag in Weighted Drilling Fluids in Highly Deviated Wells

Middle of the book TestA Units 1 7

Investigation Of Economic Crimes Attention Of Dr J P Mutonyi

Middle of the book TestA Units 1 7

End of the book TestA Units 1 14

Investigation of bioactive compounds

3 T Proton MRS Investigation of Glutamate and Glutamine in Adolescents at High Genetic Risk for Schi

więcej podobnych podstron