1

A

LL

M

ATERIALS

ARE

FOR

PUBLICATION

ON

OR

AFTER

M

ONDAY

, A

PRIL

15, 2002

Photo Booklet

The photo booklet contains a photo of Glenn Murcutt and a selection of full color

reproductions of his works. This does not represent a complete catalogue of the Laureate’s

work, but rather a representative sampling. They are all 200 line screen lithographs printed

on high gloss stock. These replace the need for using black & white continuous tone prints.

They may be re-photographed using 85 line screens for black & white newspaper

reproduction, and they can be re-sized, either 50% larger or smaller with no degradation

in the image quality or moire effect. The same holds true for the B&W images in the media

text booklet. For color reproduction, you have a choice of digital scanning, requesting color

slides or a CD of hi-res images. You may also download image files. We can provide high

resolution (1200 dpi) TIFF or EPS files of the images using ZIP or HQX archive formats

for uploading directly to your FTP server or via e-mail. Call the Media Office listed below.

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs/drawings are courtesy of Glenn Murcutt. Permission is

granted for media use in relation to the Pritzker Architecture Prize. They may not be used for any

other advertising or publicity purpose without permission from the individual photographers. Photo

credit lines should appear next to published photos as indicated in these media materials.

The Hyatt Foundation

Media Information Office

Attn: Keith H. Walker

8802 Ashcroft Avenue

Los Angeles, CA 90048-2402

phone: 310-273-8696 or

310-278-7372

fax: 310-273-6134

e-mail: jenswalk@earthlink.net

http:/www.pritzkerprize.com

M

EDIA

C

ONTACT

Note to Editors: For complete details on the history of the Pritzker Prize

and previous laureates, see www.pritzkerprize.com.

Media Text Booklet

Previous Laureates of the Pritzker Prize ................................................. 2

Media Release Announcing the 2002 Laureate ................................. 3-6

Members of the Pritzker Jury ................................................................... 7

Citation from Pritzker Jury ....................................................................... 8

Comments from Individual Jurors ........................................................... 9

About Glenn Murcutt ........................................................................ 10-17

Description of Simpson-Lee House .................................................. 17-18

Fact Summary – Chronology of Works, Exhibits, Honors ............ 19-22

Drawings and B&W Photographs of Murcutt’s Works .................. 23-28

2002 Ceremony Site – Rome, Italy ................................................. 29-30

History of the Pritzker Prize ............................................................. 31-32

M

EDIA

K

IT

ANNOUNCING

THE

2002

P

RITZKER

A

RCHITECTURE

P

RIZE

L

AUREATE

2

1979

Philip Johnson of the United States of America

presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

1980

Luis Barragán of Mexico

presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

1981

James Stirling of the United Kingdom

presented at the National Building Museum, Washington, D.C.

1982

Kevin Roche of the United States of America

presented at The Art Institute, Chicago, Illinois

1983

Ieoh Ming Pei of the United States of America

presented at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

1984

Richard Meier of the United States of America

presented at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

1985

Hans Hollein of Austria

presented at the Huntington Library,

Art Collections and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, CA

1986

Gottfried Boehm of Germany

presented at Goldsmiths’ Hall, London, England

1987

Kenzo Tange of Japan

presented at the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

1988

Gordon Bunshaft of the United States and Oscar Niemeyer of Brazil

presented at The Art Institute, Chicago, Illinois

1989

Frank O. Gehry of the United States of America

presented at Todai-ji Buddhist Temple, Nara, Japan

1990

Aldo Rossi of Italy

presented at Palazzo Grassi, Venice, Italy

1991

Robert Venturi of the United States of America

presented at Palacio de Iturbide, Mexico City, Mexico

1992

Alvaro Siza of Portugal

presented at the Harold Washington Library Center, Chicago, Illinois

1993

Fumihiko Maki of Japan

presented at Prague Castle, Czech Republic

1994

Christian de Portzamparc of France

presented at The Commons, Columbus, Indiana

1995

Tadao Ando of Japan

presented at the Grand Trianon and the Palace of Versailles, France

1996

Rafael Moneo of Spain

presented at the construction site of The Getty Center, Los Angeles, CA

1997

Sverre Fehn of Norway

presented at the construction site of The Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, Spain

1998

Renzo Piano of Italy

presented at The White House, Washington, D.C.

1999

Sir Norman Foster of the United Kingdom

presented at the Altes Museum, Berlin, Germany

2000

Rem Koolhaas of The Netherlands

presented at The Jerusalem Archaeological Park, Israel

2001

Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron of Switzerland

presented at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, Virginia

P

REVIOUS

P

RITZKER

A

RCHITECTURE

P

RIZE

L

AUREATES

3

Los Angeles, CA — An Australian architect, Glenn Murcutt, who

works as a sole practitioner, primarily designing environmentally sensitive

modernist houses that respond to their surroundings and climate, as

well as being scrupulously energy conscious, has been named to receive

the 2002 Pritzker Architecture Prize. The 66 year old Murcutt lives and

has his office in Sydney, but travels the world teaching and lecturing to

university students.

In announcing the jury’s choice, Thomas J. Pritzker, president of

The Hyatt Foundation, said, “Glenn Murcutt is a stark contrast to most

of the highly visible architects of the day — his works are not large

scale, the materials he works with, such as corrugated iron, are quite

ordinary, certainly not luxurious; and he works alone. He acknowledges

that his modernist inspiration has its roots in the work of Mies van der

Rohe, but the Nordic tradition of Aalto, the Australian wool shed, and

many other architects and designers such as Chareau, have been

important to him as well. Add in the fact that all his designs are

tempered by the land and climate of his native Australia, and you have

the uniqueness that the jury has chosen to celebrate. While his primary

focus is on houses, one of his public buildings completed in 1999, the

Arthur and Yvonne Boyd Education Centre, has achieved acclaim as

well, critics calling it ‘a masterwork’.”

Pritzker Prize jury chairman, J. Carter Brown, commented, “Glenn

Murcutt occupies a unique place in today’s architectural firmament. In

an age obsessed with celebrity, the glitz of our ‘starchitects,’ backed by

large staffs and copious public relations support, dominate the headlines.

As a total contrast, our laureate works in a one-person office on the

other side of the world from much of the architectural attention, yet has

a waiting list of clients, so intent is he to give each project his personal

best. He is an innovative architectural technician who is capable of

turning his sensitivity to the environment and to locality into forthright,

totally honest, non-showy works of art. Bravo!”

The formal presentation of what has come to be known throughout

Australian Architect

Becomes the 2002 Laureate of the

Pritzker Architecture Prize

For publication on or after Monday, April 15, 2002

4

the world as architecture's highest honor will be made at a ceremony on

May 29, 2002 at Michelangelo’s Campidoglio in the heart of Rome. At

that time, Murcutt will be presented with a $100,000 grant and a bronze

medallion. Murcutt is the first Australian to become a Pritzker Laureate,

and the 26th honoree since the prize was established in 1979. His

selection continues what has become a ten-year trend of laureates from

the international community. In fact, architects from other countries

chosen for the prize now far outnumber the U.S. recipients, nineteen to

seven.

Bill Lacy, who is an architect spoke as the executive director of the

Pritzker Prize, quoting from the jury citation which states, “His is an

architecture of place, architecture that responds to the landscape and the

climate. His houses are fine tuned to the land and the weather. He uses a

variety of materials, from metal to wood to glass, stone, brick and concrete

— always selected with a consciousness of the amount of energy it took to

produce the materials in the first place.”

Lacy elaborated, “Murcutt’s thoughtful aproach to the design of such

houses as the Marika-Alderton House in Eastern Arnhem Land; the Marie

Short House in New South Wales; and the Magney House at Bingie Bingie,

South Coast, New South Wales, are testament that aesthetics and ecology

can work together to bring harmony to man’s intrusion in the environment.”

Ada Louise Huxtable, architecture critic and member of the jury,

commented further saying, “Glenn Murcutt has become a living legend,

an architect totally focused on shelter and the environment, with skills

drawn from nature and the most sophisticated design traditions of the

modern movement.”

Another juror, Carlos Jimenez from Houston who is professor of

architecture at Rice University, said, “Nurtured by the mystery of place

and the continual refinement of the architect’s craft, Glenn Murcutt’s

work illustrates the boundless generosity of a timely and timeless vision.

The conviction, beauty and optimism so evident in the work of this

most singular, yet universal architect remind us that architecture is

foremost an ennobling word for humanity.”

And from juror Jorge Silvetti, who chairs the Department of Archi-

tecture, Graduate School of Design at Harvard University, “The archi-

tecture of Glenn Murcutt surprises first, and engages immediately after

because of its absolute clarity and precise simplicity — a type of clarity

that soon proves to be neither simplistic nor complacent, but inspiringly

dense, energizing and optimistic. His architecture is crisp, marked and

impregnated by the unique landscape and by the light that defines the

fabulous, far away and gigantic mass of land that is his home, Australia.

5

Yet his work does not fall into the easy sentimentalism of a chauvinistic

revisitation of the vernacular. Rather, a considered, serious look would

trace his buildings’ lineage to modernism, to modern architecture, and

particularly to its Scandinavian roots planted by Asplund and Lewerentz,

and nurtured by Alvar Aalto.”

The purpose of the Pritzker Architecture Prize is to honor annually

a living architect whose built work demonstrates a combination of

those qualities of talent, vision and commitment, which has produced

consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built

environment through the art of architecture.

The distinguished jury that selected Murcutt as the 2002 Laureate

consists of its founding chairman, J. Carter Brown, director emeritus

of the National Gallery of Art, and chairman of the U.S. Commission

of Fine Arts; and alphabetically: Giovanni Agnelli, chairman emeritus

of Fiat from Torino, Italy; Ada Louise Huxtable, author and

architectural critic of New York; Carlos Jimenez, professor at Rice

University School of Architecture, and principal, Carlos Jimenez Studio

Houston, Texas; Jorge Silvetti, chairman, department of architecture,

Harvard University Graduate School of Design; and Lord Rothschild,

former chairman of the National Heritage Memorial Fund of Great

Britain and formerly the chairman of that country's National Gallery

of Art.

The prize presentation ceremony moves to different locations around

the world each year, paying homage to historic and contemporary

architecture. Last year, the ceremony was held in Charlottesville, Virginia

at Thomas Jefferson's home, Monticello, which the former president

and author of the Declaration of Independence, as well as accomplished

architect, designed. In 2000, the ceremony was held in Jerusalem in the

Archaeological Park surrounding the Dome of the Rock.

Philip Johnson was the first Pritzker Laureate in 1979. The late Luis

Barragán of Mexico was named in 1980. The late James Stirling of

Great Britain was elected in 1981, Kevin Roche in 1982, Ieoh Ming Pei

in 1983, and Richard Meier in 1984. Hans Hollein of Austria was the

1985 Laureate. Gottfried Boehm of Germany received the prize in

1986. Kenzo Tange was the first Japanese architect to receive the prize

in 1987; Fumihiko Maki was the second from Japan in 1993; and Tadao

Ando the third in 1995. Robert Venturi received the honor in 1991, and

Alvaro Siza of Portugal in 1992. Christian de Portzamparc of France

was elected Pritzker Laureate in 1994. The late Gordon Bunshaft of the

United States and Oscar Niemeyer of Brazil, were named in 1988.

Frank Gehry was the recipient in 1989, the late Aldo Rossi of Italy in

6

1990. In 1996, Rafael Moneo of Spain was the Laureate; in 1997

Sverre Fehn of Norway; in 1998 Renzo Piano of Italy, in 1999 Sir

Nor man Foster of the UK, and in 2000, Rem Koolhaas of the

Netherlands. Last year, two architects from Switzerland received the

honor: Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron.

The field of architecture was chosen by the Pritzker family because

of their keen interest in building due to their involvement with developing

the Hyatt Hotels around the world; also because architecture was a

creative endeavor not included in the Nobel Prizes. The procedures

were modeled after the Nobels, with the final selection being made by

the international jury with all deliberations and voting in secret.

Nominations are continuous from year to year with over 500 nominees

from more than 40 countries being considered each year.

# # #

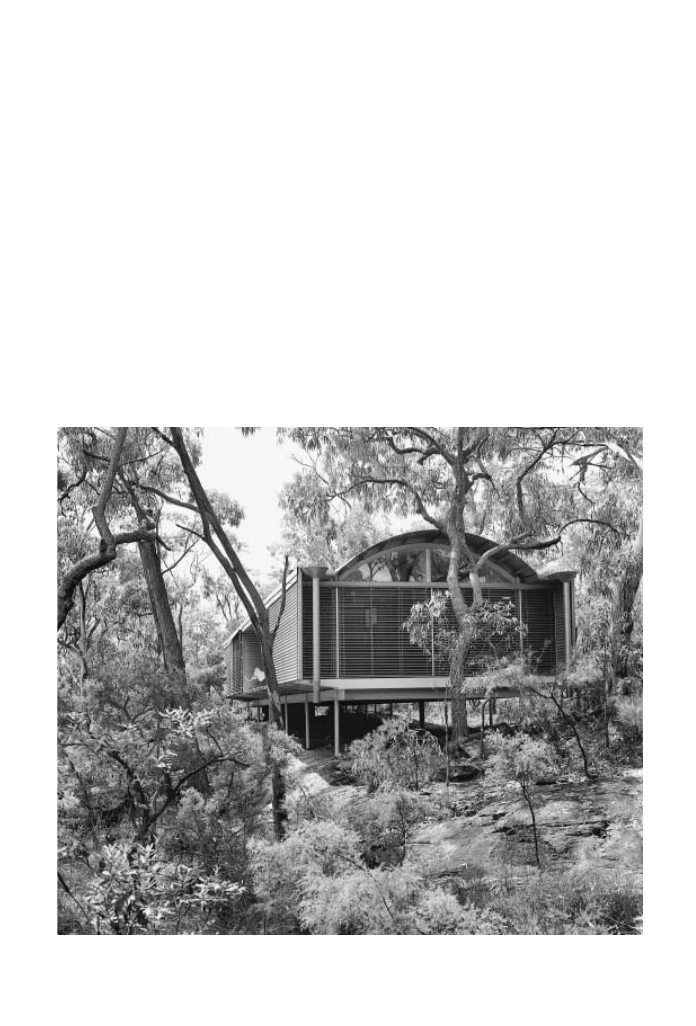

Ball-Eastaway House 1980-1983

Glenorie, Sydney, NSW

Photo by Anthony Browell

7

T

HE

J

URY

C

HAIRMAN

J. Carter Brown

Director Emeritus, National Gallery of Art

Chairman, U.S. Commission of Fine Arts

Washington, D.C.

Giovanni Agnelli

Chairman Emeritus, Fiat

Torino, Italy

Ada Louise Huxtable

Author and Architectural Critic

New York, New York

Carlos Jimenez

Professor, Rice University School of Architecture

Principal, Carlos Jimenez Studio

Houston, Texas

Jorge Silvetti

Chairman, Department of Architecture

Harvard University, Graduate School of Design

Cambridge, Massachusetts

The Lord Rothschild

F o r m e r C h a i r m a n o f t h e B o a r d o f T r u s t e e s , N a t i o n a l G a l l e r y

F o r m e r C h a i r m a n , N a t i o n a l H e r i t a g e M e m o r i a l F u n d

L o n d o n , E n g l a n d

E

XECUTIVE

D

IRECTOR

Bill Lacy

S t a t e U n i v e r s i t y o f N e w Y o r k a t P u r c h a s e

P u r c h a s e , N e w Y o r k

8

Citation from the Jury

Glenn Murcutt is a modernist, a naturalist, an environmentalist,

a humanist, an economist and ecologist encompassing all of

these distinguished qualities in his practice as a dedicated

architect who works alone from concept to realization of his

projects in his native Australia. Although his works have

sometimes been described as a synthesis of Mies van der Rohe

and the native Australian wool shed, his many satisfied clients

and the scores more who are waiting in line for his services are

endorsement enough that his houses are unique, satisfying

solutions.

Generally, he eschews large projects which would require him

to expand his practice, and give up the personal attention to

detail that he can now give to each and every project. His is an

architecture of place, architecture that responds to the landscape

and to the climate.

His houses are fine tuned to the land and the weather. He uses

a variety of materials, from metal to wood to glass, stone, brick

and concrete — always selected with a consciousness of the

amount of energy it took to produce the materials in the first

place. He uses light, water, wind, the sun, the moon in working

out the details of how a house will work — how it will respond

to its environment.

His structures are said to float above the landscape, or in the

words of the Aboriginal people of Western Australia that he is

fond of quoting, they “touch the earth lightly.” Glenn Murcutt’s

structures augment their significance at each stage of inquiry.

One of Murcutt’s favorite quotations from Henry David Thoreau,

who was also a favorite of his father, “Since most of us spend our

lives doing ordinary tasks, the most important thing is to carry

them out extraordinarily well.” With the awarding of the 2002

Pritzker Architecture Prize, the jury finds that Glenn Murcutt is

more than living up to that adage.

9

"Glenn Murcutt occupies a unique place in todayís architectural firmament. In an age obsessed

with celebrity, the glitz of our ëstarchitects,í backed by large staffs and copious public relations

support, dominate the headlines. As a total contrast, our laureate works in a one-person office

on the other side of the world from much of the architectural attention, yet has a waiting list of

clients, so intent is he to give each project his personal best. He is an innovative architectural

technician who is capable of turning his sensitivity to the environment and to locality into

forthright, totally honest, non-showy works of art. Bravo!"

J. Carter Brown

Chairman, Pritzker Jury

ìGlenn Murcutt has become a living legend, an architect totally focused on shelter and the

environment, with skills drawn from nature and the most sophisticated design traditions of the

modern movement.î

Ada Louise Huxtable

Pritzker Juror

"Nurtured by the mystery of place and the continual refinement of the architectís craft, Glenn

Murcuttís work illustrates the boundless generosity of a timely and timeless vision. The

conviction, beauty and optimism so evident in the work of this most singular, yet universal

architect remind us that architecture is foremost an ennobling word for humanity."

Carlos Jimenez

Pritzker Juror

"The architecture of Glenn Murcutt surprises first, and engages immediately after because of

its absolute clarity and pecise simplicity ó a type of clarity that soon proves to be neither

simplistic nor complacent, but inspiringly dense, energizing and optimistic. His architecture

is crisp, marked and impregnated by the unique landscape and by the light that defines the

fabulous, far away and gigantic mass of land that is his home, Australia. Yet his work does

not fall into the easy sentimentalism of a chauvinistic revisitation of the vernacular. Rather, a

considered, serious look would trace his buildingsí lineage to modernism, to modern

architecture, and particularly to its Scandinavian roots planted by Asplund and Lewerentz, and

nurtured by Alvar Aalto."

Jorge Silvetti

Pritzker Juror

ìGlenn Murcuttís buildings embrace both simplicity and elegance, but with a social and

environmental conscience. Although most of his work is small in scale, it is remarkable for its

purity and adherence to the guiding principles of modern architecture.î

Bill Lacy

Executive Director

T he bronze medallion awarded to each Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize is based on designs of Louis Sullivan,

famed Chicago architect generally acknowledged as the father of the skyscraper. On one side is the name of the prize. On

the reverse, three words are inscribed, “fir mness, commodity and delight,” T hese are the three conditions referred to by

Henr y Wotton in his 1624 treatise, The Elements of Architecture, which was a translation of thoughts originally

set down nearly 2000 years ago by Marcus Vitruvius in his Ten Books on Architecture, dedicated to the Roman Emperor

Augustus. Wotton, who did the translation when he was England’s first ambassador to Venice, used the complete quote

as: “T he end is to build well. Well-building hath three conditions: commodity, fir mness and delight.”

Note to editors: The following are some additional comments

from individual Pritzker Prize Jurors:

10

Note to editors: It would be impossible in this brief media kit to provide a

complete biography or to outline and discuss all of Glenn Murcuttís work. Rather

an attempt is made to highlight some important aspects of his life, and some

of his projects and thoughts on architecture. A detailed chronological list of

his projects and honors is provided in another section of this kit. A selected

bibliography is also provided for anyone wanting further research.

…about Glenn Marcus Murcutt

Glenn Murcutt is either one of Australia’s best kept secrets, or one of the

world’s most influential architects. Perhaps, both. On the other hand, we should

temper “secret” somewhat since he has been the subject of numerous books and

magazine articles throughout the world. One of the first definitive works was Glenn

Murcutt Works and Projects by Françoise Fromonot, first published in 1995. In

that book, she describes Murcutt as the “first Australian architect whose work has

attracted international attention.”

His relatively low profile can best be explained by the fact that he works

alone, primarily for clients who want houses that are not only environmentally

sensitive, but provide privacy and security in a structure that pleases all the senses.

In stark contrast to many of his contemporaries, Murcutt has declared, “I am not

interested in designing large scale projects. Doing many smaller works provides me

with many more opportunities for experimentation. Our building regulations are

supposed to prevent the worst; they in fact fail to stop the worst, and at best frustrate

the best — they certainly sponsor mediocrity. I’m trying to produce what I call

minimal buildings, but buildings that respond to their environment.”

“I have had to fight for my architecture. I have fought for it right from the

outset because councils have clearly found the work a threat. For many designs I put

to council, we either had to resort to a court for the outcome or better, negotiate a

satisfactory result, always trying to avoid a compromise. I have had the greatest

trouble with planning, building and health department staff, many of whom have

backgrounds unrelated to architecture, but offer very conservative judgments in

taste and aesthetics.”

What manner of man and architect is this who could so openly state his

opposition to the people who exercise so much control over what and how things

should be built? A look at his colorful family, as well as how and where he was

raised is a partial explanation. And “colorful” is a mild adjective in this application;

Murcutt’s life is the stuff of which movies are made.

Glenn Murcutt today readily credits his father as being a strong influence

toward his architectural career. This brief reflection of family history further explains

some of the influences that have shaped his work.

His father, Arthur Murcutt was born in Melbourne in 1899. By the time he

was thirteen, he ran away from home, seeking something more than what he would

describe later to his son, “the ugliness of life.” He worked at odd jobs, from station

hand to well sinker to sheep shearer before shipping off to Port Moresby, New

11

Guinea, which had just been declared an Australian Mandated Territory at the end

of World War I. There he worked as a bootmaker and saddler, as well as learning

carpentry, before setting off with a partner on an adventure to prospect for gold in

New Guinea. When they failed to find the precious metal, he landed work as

superintendent of a plantation and builder of houses, and even had time to indulge

his interest in music, buying a gold-plated saxophone.

When he returned to Port Moresby, he teamed up with another of his mates

to build a yacht in which the two of them would sail across the Pacific. The mate

was a fellow Australian, Errol Flynn, before he achieved his movie stardom in the

United States. Their cruise was canceled when the boat sank shortly after being

launched. As his father related the story, it sank due to sabotage to prevent Flynn

from leaving the country owing money.

By the time 1932 arrived, Arthur Murcutt was operating a sawmill in Wau

(still in New Guinea), but gold lured him and another partner into a second venture

in prospecting, this time with enough success that it made him a fairly wealthy man.

Two years into his gold mining days, he met and married Daphne Powys, the

daughter of a photographer from Manly, Australia.

In 1936, with things going well in the gold business, Arthur Murcutt and his

pregnant wife decided to go to the Berlin Olympics. During a stopover in London,

their first son, Glenn Murcutt, was born. Their return to Australia was via the

Aquitania to New York, and then a cross-country car trip to Los Angeles where

they sailed the Pacific to reach home. With such round-the-world travels under his

belt before the age of one, it’s no wonder that Glenn Murcutt would later visit

nearly every continent as a lecturer or visiting professor at leading universities. Of

this, he says, “Teaching has proved a wonderful way to learn. Not only have my

students provided challenges, but they are sounding boards for ideas, and my

association with other teachers has provided great stimulus.”

But back to 1937, when the Murcutt family go into the wilds of New Guinea

where they remained until the approaching Japanese at the outset of World War II

drove them back to Australia in 1941. Those first five years of life in New Guinea

had a profound influence on Glenn, whether actual memory or family recollections.

That family now included a brother and sister for Glenn, Douglas and Nola.

Glenn’s mother recounted to him how his father would take several books

with him each day when he went up to the gold mining area, and his father confirmed

that when Glenn was older, telling him, “I got my education in the forests of New

Guinea because I had time to read.” Jung, Freud and particularly Henry David

Thoreau were his father’s favorites, and the latter became one of Glenn’s as well.

“There is no doubt my father was a compulsive reader. He had many of Freud’s

first publications.”

Glenn quotes a passage from Thoreau, “But the civilized man has the habits

of the house. His house is his prison, in which he finds himself oppressed and

confined, not sheltered and protected. He walks as if the walls would fall in and

crush him, and his feet remember the cellar beneath. His muscles are never relaxed.

12

It is a rare thing that he overcomes the house, and learns to sit at home in it, and the

roof and the floor and walls support themselves, as the sky and trees and earth.”

Murcutt wanted to experience his Marie Short house for a 24-hour period,

which he did starting after the evening meal and every two hours going to a different

part of the house to see what was happening. Says Murcutt, “It was wonderful to be

there. I was in command. I was able to say if I wanted the wind to come in or not.

I wasn’t enslaved by the building. I could hear the frogs, the crickets; I could tell the

day was coming by the sounds of the birds waking. The moon came through the

skylight — patches of blue light entered the room. You can’t experience that easily

in the forest because you would be eaten by mosquitos. Here I was in a man-made

environment that is insect meshed, but able to experience ninety per cent of the

outside environment. I could open up the house and freeze or close it and stay

warm. That’s what a house should do — to operate the building like sailing a boat.”

He continues, “I also say that we should, as architects, observe how we dress

according to our different climates. We layer our clothing, put more on when its

cold, take more off when its hot — and I think our buildings should equally respond

to their climates. Very few of my buildings have air conditioning. To my very good

Finnish friends, I point out that they tend to put on more clothes, and we in Australia

think more about taking them off — that’s of course what most of my buildings

do.”

Glenn remembers their home in New Guinea, built by his father, with a

roof of light weight corrugated iron, and perched on stilts a full story above ground

to keep water and reptiles out, as well as affording some protection from quite

dangerous local people, who at least once were discouraged from attacking when

his mother fired a rifle over their heads. He elaborates, “The local people were very

angry about our living in their land; we simply occupied it and took from it. Yes,

they were dangerous. They were known as the Kukuku people, feared also by other

national New Guineans, and even today, they are still feared.”

Another childhood memory is that of aviation, which was a primary means

of transportation, as well as the delivery of mail and materials. Glenn quotes the

statistic that in the 1930’s, the Wau and Bulolo airports in New Guinea had three

times the number of passengers and cargo arriving and departing as any other

airport in the world. Many of the planes were Junker G/31 and W/34 models

whose wings and fuselage were covered with corrugated duralumin.

At one point, Glenn says he was concerned that he was becoming known as

the “corrugated Gal Iron King.” He points out that he hasn’t used galvanized iron

just to be using it as a gimmick. He says, “I use it because it’s an important material

for the things I want to do. It’s capable of giving me that thinness, that lightweight

quality, an edge, a fineness, economy and strength and profile. I’m able to bend it

and curve it in two dimensions. I love it because it reflects the quality of the light of

the day and surrounding colors. On a dull day, the building dulls down; on a bright

day, the building is bright. When laid with the ribs horizontal, the upper surface of

the corrugation picks up the sky light and the lower surface, the ground light —

13

accentuating the horizontal. That’s a material which responds to its environment.”

Speaking further about his use of corrugated iron, Murcutt says, “Horizontal

linearity is an enormous dimension of this country, and I want my buildings to feel

part of that. Take the iron sheeting on outside walls, for example, generally it runs

vertically, and I believe it should run horizontally. It’s not only logical in terms of

the material itself, but it’s logical in terms of a stud frame to fix it horizontally. If it

runs vertically, it competes with the trees. I don’t want to compete with trees, let

them complement the horizontality of the man-made iron sheets.”

But to return to earlier history, his father, Arthur Murcutt, proved to be an

astute business man, investing his gold earnings in land in Sydney, Australia, so

when World War II was over, he established a joinery shop in Manly Vale, having

learned carpentry from his work in New Guinea and in the Royal Australian Air

Force. He became increasingly interested in architecture, subscribing to Architectural

Forum, where he saw Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth house, and was so impressed

by it that he made it required reading for Glenn, who studied the article three times

before being quizzed by his father about the design.

This Miesian influence on the architecture of Glenn Murcutt would prove

to be long-lasting. He whole-heartedly adheres to the well-known principle “less is

more,” and another that “form is not the aim of our work, but only the result.” In

1974, when designing the Marie Short house in Kempsey, Murcutt protected the

house from insects, snakes and large lizards during floods when they would swim to

the high ground. He says, “A house set on the ground would see frogs, snakes, etc.

inside; being off the ground provided a place below the floor for these creatures

and dry, reptile free platform for human habitation.” There is a similarity to the

way Glenn suspended the wooden floor above ground for this house to the way

Mies had done with Farnsworth house to protect it from floods of the Fox River in

Illinois. His father also introduced him to the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, Gordon

Drake, the Keck brothers, Harry Weese, Edward Larrabee Barnes, Schindler, Philip

Johnson and Charles Eames, as well as some of Australia’s post-war modernists

such as Sydney Ancher and Arthur Baldwinson.

Murcutt senior designed and built several houses for his family (as well as

several speculative houses) over the years — all of which are evidence of his interest

in modern architecture. When Glenn was 13, his father assigned him the task of

making of a model house of where they lived at the time, and then photographing

it. Anyone looking at the model could see further evidence of his father’s efforts to

design in what would now be called a modernist idiom.

Glenn remembers that his father had a keen awareness of the environment,

saying, “He would take me up the hillside and analyze a plant with me. We’d do

that with all manner of species of plants and trees. He tried to stop people from

cutting the trees, and when he couldn’t stop them, he’d go out and plant seeds for

more.”

“There were lessons to be learned from dad every day,” continues Glenn,

“whether it was the landscape, nature, music, swimming, woodworking, and

14

household chores. I had learned to swim by the time I was two and a half. Dad

taught us to be disciplined, and how to accomplish a lot in every day. Yes, he scared

all five children, but he was also very warm.”

Glenn admits to doing rather badly in elementary school and the early years

in high school, but later on in high school, he had what he describes as some really

great teachers, singling out one particular piano teacher as being the best and most

gentle in Sydney. “I became quite reasonable at performances and started to play

some really interesting classical compositions by Bach, Liszt and Beethoven.”

At university, he remembers “the most gruelling experience” he’d ever had.

“Sixty students,” he recalls, “undertook the final year five-day design exam. At the

end of the third day, three fourths of them had ‘designed’ and completed some

beautiful final drawings. By day four, only six of us were still there. By the end of

that day, only three of us remained. On the fifth day, I found a worthwhile idea and

went on to complete seven large freehand drawings.”

Murcutt continues, “What I learnt from that experience was that architecture

often requires time to evolve if it is to be of any consequence. I recall that those who

completed the design examination quickly, presenting some beautiful drawings, were

somewhat short on thinking!”

With a diploma awarded in December of 1961, he took a walking tour of

Tasmania with a school friend before starting work. A year later, he was able to

take a trip to Europe where he visited Italy, Yugoslavia, Greece, France, Holland,

Germany, Poland, Denmark, Sweden and Finland over a two year period. It was

on this journey that he saw his first Alvar Aalto building, a cultural centre in

Wolfsburg, Germany. He found it “remarkable in its sections, planning, use of

materials, detail and form.” He went on to Bremen to see Aalto’s 22-story high-rise

apartments. Glenn’s reaction: “Everything Aalto did started from first principles

and had a quality of being thoroughly thought through.” Little did he know that in

1992 he would be presented with the seventh Alvar Aalto Medal.

The jury for that award, specifically praised Murcutt’s work for “the

convincing synthesis of regional characteristics, climate-conditioned solutions,

technological rationality and unconstrained visual expression.” Glenn has since

commented that he thought it significant that Jørn Utzon, Alvaro Siza and Tadao

Ando were all previous winners of the Aalto Medal, and in his words, “all of them

sought to marry modern architecture to the place, the territory, the landscape.”

Following that trip to Europe, Glenn returned to Sydney to work in the firm

of Ancher, Mortlock, Murray & Wooley, until 1969 when he founded his own

architectural firm. He had long ago decided when he was still at university that he

would prefer to work at his profession as a sole practitioner, which he has done ever

since. He feels that by working alone, figuring where that next dollar is coming from

is far less pressing than in a large firm. “When the need arises,” he says, “such as a

very good project offered requiring more input than one person is able to do alone,

I work in association with other architects whom I greatly respect. This rather than

15

employing staff — that way, we share an equality. Further, as a one-man office, I

have been able to experiment with wind patterns, materials, light, climate, spaces,

and the characteristics of the site.”

As a result of a travel grant awarded to him by Royal Australian Institute of

Architects for “a degree of creativity in upgrading older houses using new techniques

without destroying them,” he made a second tour of Europe in 1973. It was on

that trip that he first saw the Maison de Verre by Pierre Chareau and Bernard

Bijvoët in Paris. Murcutt describes his visit there as “a liberating experience.” On

the way to Europe, a stopover in Mexico afforded him the opportunity to see Mies

van der Rohe’s Bacardi office building, which he described as “beautifully put

together.” He notes, “I saw some beautiful sculpture, water gardens in Mexico

City, but didn’t find out that they were by Luis Barragán until I returned home.”

Barragán has been another continuing influence on Murcutt. Another highlight of

that trip was a visit to Chicago where he saw Robie house (by Frank Lloyd Wright)

and a trip to Racine, Wisconsin to see the Johnson Wax administration building

and research tower. He also saw more of Mies’ and Louis Sullivan’s works.

Visiting Boston, he had the opportunity to visit Walden Pond, and the site

of Henry David Thoreau’s home. “I lived 25 years in one day, in terms of memory

and what my father had talked about concerning Thoreau,” says Glenn. “I was so

excited, I was tearful.” His father had read Thoreau and responded positively to

his philosophy, passing much of that on to Glenn.

In New York City, which he found incredibly exciting, but somewhat

frightening, he was, to quote him, “really impressed with the Chrysler Building,

Rockefeller Centre and the Ford Foundation Headquarters by Kevin Roche and

John Dinkeloo; to produce that environment in an office building was terrific.”

His travels have continued over the years, particularly as he has become a

much in demand lecturer and visiting professor in architecture schools all over the

world, visiting some twenty countries. In 1997, Murcutt married Wendy Lewin, a

fellow architect with whom he has worked on a number of projects. He has two

sons by a previous marriage: Nicholas, 37, who is an architect; and Daniel, 35, who

is an assistant library technician; and a step-daughter, Anna Lewin-Tzannes, 13.

Some seventeen years ago, in the foreword to a book by Philip Drew, titled

Leaves of Iron and sub-titled Glenn Murcutt: Pioneer of an Australian Architectural

Form, Murcutt wrote: “Landscape in Australia is remarkable. I have learned much

from scrutinising the land and its flora. There is an over-riding horizontality. The

flora is tough. It is in addition, durable, hardy and yet supremely delicate. It is so

light at its edges that its connection with the deep skyvault is unsurpassed anywhere.

The sunlight is so intense for most of the continent that it separates and isolates

objects. The native trees read not so much as members of a series of interconnected

elements, but as groupings of isolated elements. The high oil content of so many of

the trees combined with the strong sunlight results in the foliage shimmering silver

to weathered greys with an affinity towards the pink browns to olives. The foliage is

16

not dense generally and the shadows are therefore a dappled light. This distinguishes

our landscape from that of most other countries where the soft light serves to connect

the elements of the landscape, rather than separate them. My architecture has

attempted to convey something of the discrete character of elements in the Australian

landscape, to offer my interpretation in built form.”

And further, “When I consider the magic of our landscape. I am continually

struck by the genius of the place, the sunlight, shadows, wind, heat and cold, the

scents from our flowering trees and plants, and, especially the vastness to the island

continent. All these factors go to make a land of incredible strength combined with

an unimaginable delicacy.”

So it is not surprising when his words go on: “I am stirred to the point of

anger when I see what continues to be done by so called progress. The destruction

of the flora, the displacement of the fauna and all of it with the blessing, if not

active collusion of our subdivision regulations. I am not rejecting urbanization. I

am not seeking a kind of utopia in the bush — far from it. I am involved with and

recognize the importance of a varied milieu. I am opposed to the total taming of

this land and the loss of the wildness of the native scene. The land appeals for care

and we need to become friends with the landscape and not be threatened by it.”

But his design decisions are not simply based on aesthetics, his houses are

designed using materials that have consumed as little energy as possible in their

manufacture, and will consume as little as possible in the operation of the house.

His houses respond to all manner of climatic conditions, producing their own shade,

ventilation and in most cases function without air conditioning or heating other

than a fireplace. Some houses in the colder regions have back-up under-floor heating

which is not often used.

The Aboriginal people in Western Australia have a saying, “to touch this

earth lightly,” which is a plea for man not to disturb nature any more than necessary.

Because Glenn Murcutt’s architecture conveys that thought with his houses that

float above the land, if not on stilts a full story high, but on footings that disturb the

land minimally. It is not surprising to find another book authored by Drew in 1999,

titled Touch This Earth Lightly, and subtitled Glenn Murcutt in His Own Words.

A typical passage from that book about the Marie Short farm house illustrates

his passion for fitting the architecture to the site: “It gave me the opportunity to

really begin to understand what Australia was like. What its climate was like, the

humidity level, the amount of shade we require, the wind pattern, the sort of

evaporative factor we require in order to be comfortable in shade, in a climate such

as ours. One of the main discoveries was that anything less than a fully opening

wall was inadequate in our climate (at Kempsey). In my opinion, an opening wall

for summer conditions is essential to cooling all spaces. In summer and the change

of season, everyone, without exception, has commented on what a delightfully

temperate building it is, even on the most extreme days.”

The Australian bush fires are world-famous, and while Murcutt acknowledges

fire is important in his country especially for the propagation of many plants, he

17

has to plan ways to save his structures if they encounter fire. In the Simpson-Lee

house at Mt. Wilson, there is a pool alongside the entrance walkway that holds part

of the water necessary for the built-in sprinkler system in case of fire. (It also provides

a reflective medium for the sunlight that bounces onto the ceiling of the interior of

the house.) In the Munro farm house at Bingara, he devised a plan that had two

wells to collect the roof water. These supplied enough recirculated water to sprinkle

the house for 5-6 hours a day during the hottest season.

Controlling how much sunlight penetrates his houses and manipulating the

breezes at various times of the year and the day is another important facet to his

design process. He’s re-introduced in Sydney storm blinds, a version of Venetian

blinds for outside that are made of metal. He had learned in his school days that

once the heat entered a building, there was little else one could do but air-condition

the building so the sensible solution was to provide a system of screens or blinds

that prevents the sun from reaching the glass in the first place. Murcutt has developed

forms of slatted timber and metal screens for sun control which also achieve privacy

yet maintain the movement of air.

He also uses slats set at particular angles as screens above glass not only as

sun control, allowing the entry of winter sunlight and excluding it in the summer,

but also to allow for the appreciation of the sky from within the house day and

night and seasonally. Even the pitch of the roof is variable according to the latitude

and climate of the region. In some areas, he does overlapping layers of roofs so that

the air can move between the layers, extracting roof space summer heated air.

Murcutt says, “A building should be able to open up and say, ‘I am alive and

looking after my people,’ or instead, ‘I’m closed now, and I’m looking after my

people as well.’ This to me is the real issue, buildings should respond. Look at the

gills of a fish, or animals when they become hot. When we get hot, we perspire.

Buildings should do similar things. They should open and close and modify and re-

modify and blinds should turn and open and close, open a little bit without

complication. They should do all these things. That is a part of architecture for me,

the resolution of levels of light that we desire, the resolution of the wind that we

wish for, the modification of the climate as we want it. All this makes a building

live.”

One of Glenn’s favorite quotations, which he is not quite sure whether it

comes from his father or from Thoreau, whom his father was so fond of quoting:

“Since most of us spend our lives doing ordinary tasks, the most important thing is

to carry them out extraordinarily well.”

# # #

A detailed description of one of Murcutt’s houses will afford some further insight

into his design process. The following is an excerpt from the book by Françoise

Fromonot titled Glenn Murcutt - Works and Projects.

18

The Simpson-Lee House

Mount Wilson, New South Wales 1989-1994

With demanding clients, a spartan program (a sanctuary for a retired couple

of intellectual bent seeking withdrawal from the world), a magnificent site in the Blue

Mountains (150 kilometres north-west of Sydney) comprising two isolated plots and

some three hectares (approximately 7.5 acres) in total, a rich variety of flora, and an

extraordinary panorama of hills and forests, the conception and realization of this

project took nearly six years.

Backing on to the west and south-west winds, the house faces to the views of

the east and north-east. Following the rocky massif that impedes extension to the rear,

the residence’s two pavilions stand on either side of a pond in a linear sequence.

Murcutt designed the plan as a striking horizontal progression from the access path to

the house. The path skirts the smaller studio pavilion, re-emerges as a walkway down

the length of the pool, crosses the residential pavilion, and finally escapes down the

stairway on the east side. As the path progresses, the ground beneath it slopes away, so

that the house gets further and further from the ground. This dramatizes the progression

and accentuates the sense of gradual detachment from the world sought by the

inhabitants, allowing Murcutt to terminate the building with a fine isolated vertical

member.

In the residential pavilion, the living room is symmetrically flanked by two

vestibules and two bedroom suites on either side of the kitchen, which is reduced to a

long strip of appliances. In the passage along the principal façade Murcutt reversed

his customary plan: the bedrooms, tucked under the lowest part of the roof, have

intimate proportions and very controlled light penetration. The north-east façade is

relatively dense owing to the interplay of six glazed bays, the sliding inset screens and

balustrades; the electrically operated aluminium Venetian blinds are guided by steel

braces that are tapered and lightened by perforations. With the exception of the solid

wood steps on the staircase and walkway, the house is wholly mineral: silver-painted

steel and aluminium for the structure, casings and large sloping planes of the roofs;

pale grey polished concrete on the floors; whitewash on all brick and plasterwork; and

glass. The construction system and main façade are similar to those of the Meagher

house; the back façade’s sloping glass panes and ventilation slats recall the Bingi (Bingie

Bingie) house.

The pressure from his clients pushed Murcutt to the limit of his architectural

principles. The spare design, simplified to its utmost, is almost monastic. The strongly

articulated longitudinal passage incorporates the elements in the landscape as much

as leads through the living spaces, turning it into the building’s raison d’etre. The

crystalline legibility of the spaces, barring only the two hidden bedroom units, asserts

the role of the principal actor: the site. The house also confirms Murcutt’s evolution

towards a sort of abstract expressionistic façade — a precious ribbed screen that

responds to the rhythms of the great trees filtering the sun and the view.

# # #

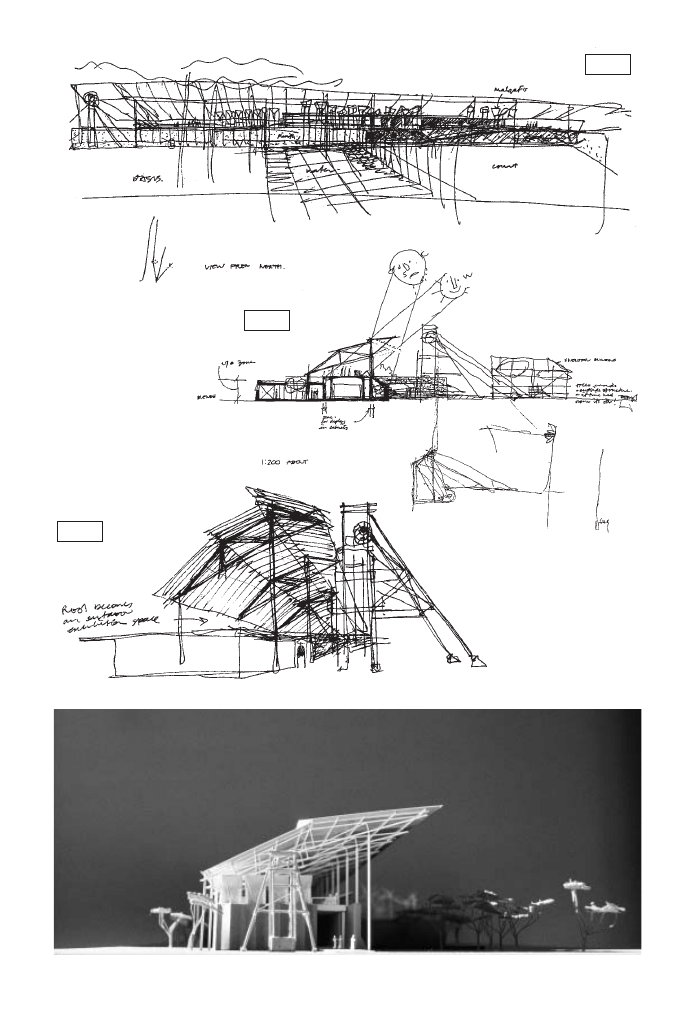

Concept sketch of the Simpson-Lee house by Glenn Murcutt on page 22.

1 9

Glenn Murcutt

2002 Laureate, Pritzker Architecture Prize

Biographical Notes

Birthdate and Place:

July 25, 1936

London, England

Education

D i p l o m a o f A r c h i t e c t u r e

U n i v e rs i t y o f N e w S o u t h Wa l e s

Te c h n i c a l C o l l e g e

S y d n e y, A u s t r a l i a

Awards and Honors

1973

Gray and Mulroney Award - RAIA

1973-1999

Received 25 Royal Australian Institute of

Architecture Awards (RAIA) - New South Wales

(NSW) and Northern Territory (NT)

State Awards

1973-1999

Two Sulman Awards for Public Housing NSW

Six Wilkinson Awards for Housing NSW

One Tracy Award for Public Buildings NT

One Burnett Award for Housing NT

National Awards

1973-2000

One Timber in Architecture Award

One Steel in Architecture Award of the Decade

Two Sir Zelman Cowan Awards for Public

Buildings

One Sir Zelman Cowan Commendation for

Public Buildings

Two Robin Boyd Awards for Housing

One Robin Boyd Commendation for Housing

One National Jury Special Award for Aboriginal

Housing

International Awards and Honors

1982

Biennale Exhibition - Paris, France

1985

Commonwealth Association of Architects (CAA)

Award for an Architecture of its Place and

Culture

1988

Jury member - AIA/Sunset Magazine Western

Division AIA Awards

1990-1991

Jury member - international competition for the

Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre, New

Caledonia - conducted by the Mission

Interministerielle des Grande Travaux - Paris,

France

1991

Biennale Exhibition - Venice, Italy

1992

Alvar Aalto Medal - Helsinki, Finland

Gold Medal - Royal Australian Institute of

Architecture

1993

Life Fellow - Royal Australian Institute of

Architecture

1995

Honorary Doctorate of Science - University of

New South Wales

1996

Biennale Exhibition - Venice, Italy

Order of Australia (AO)

Chair, international jury for student competition

for a shelter for Alvar Aalto's boat, Jyvaskyla,

Finland

1997

Honorary Fellow - American Institute of

Architects

Honorary Fellow - Royal Institute of British

Architects

F

ACT

S

UMMARY

1997-1998

Chair, International jury for a competition -

Peace Park - Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey

1998

Richard Neutra Award for Architecture and

Teaching from the Neutra Foundation and

CalPoly, Pomona, California, USA

1999

The Green Pin International Award for

Architecture and Ecology from the Academy

of Architects, Denmark

2000

Kenneth F. Brown Asia Pacific Culture &

Architecture Design Award

Jury Member - National Competition - Forum

Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra, Australia

Jury Member - Spirit of Nature, Wood

Architecture International Award, Finland

2001

Chair, Jury for the Aga Khan Award

Thomas Jefferson Medal for Architecture -

Monticello, Charlottesville, VA, USA

Honorary Fellow of the Royal Canadian

Institute of Architects

2002

Jury Member - Thomas Jefferson Medal

New International Award for an Architect who

has influenced thinking in Architecture from

the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts

Teaching

1970-1979

Design Tutor, University of Sydney

1985

Visting Professor, University of New South

Wales

1989-1997

Visiting Critic, Master of Architecture,

University of Melbourne

1990

Visiting Critic, Graduate School of Fine Arts,

University of Pennsylvania

1990-1992

Visiting Professor, University of Technology,

Sydney, Australia

1991-1995

Adjunct Professor, Graduate School of Fine

Arts, University of Pennsylvania

1991

Visiting Distinguished Architect, University of

Arizona, Tucson, Arizona

1992

Visiting Professor, PNG University of

Technology, Lae PNG

1994

Visiting Professor, University of Technology,

Helsinki, Finland

1995

Visiting Professor, University of Technology,

Sydney, Australia

1996

Visiting Professor, University of Hawaii,

Honolulu

1997

O'Neill Ford Chair, University of Texas,

Austin, Texas

Visiting Professor, PNG University of

Technology, Lae PNG

1998

Thomas Jefferson Professor, University of

Virginia

1999

Visiting Professor, School of Architecture,

Aarhus, Denmark

2000

Visiting Professor, University of California at

Los Angeles

2001

William Henry Bishop Visiting Professorial

Chair - Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

2002

Ruth and Norman Moore Visiting Professor,

Washington University in St. Louis, Mo

Distinguished J.L. Constant Lecturer,

University of Kansas, Lawrence

2 0

Addresses and Lectures

1974-1999

Addressed all Schools of Architecture and

RAIA in all states of Australia

1985

Architectural Association London, UK

1987

Colegio de Arquitectos de Mexico, Mexico

City

1988-1991

Architectural League New York, USA

1988

Visiting Architect, Architecture Week,

Auckland, New Zealand

Waigani Seminar, Port Moresby, Papua, New

Guinea

North Solomons Province University,

Bougainville, Papua, New Guinea

1988

Royal Australian Institute of Architects

Conference

1989

OAF Oslo and Trondheim, Norway

RIBA, London and Winchester, UK

Danish Academy/Institute of Architects,

Copehagen, Denmark

Finnish Association of Architects SAFA,

Helsinki, Finland

University of Milan, Italy

1990

ACSA/AIA Conference, Cranbrook Academy,

MI, USA

GSFA, University of Pennsylvania;

University of Texas, Austin, RISD; Arizona

State University, Phoenix; Harvard Graduate

School of Design; CalPoly Pomona, CA and

CalPoly San Luis Obispo, CA; University of

New Mexico, Albuquerque; University of

Virginia, Charlottesville; Frank Lloyd Wright

Foundation, Taliesin West; Parsons School of

Design New York; Architectural League,

Vancouver, Canada

1992

Papua New Guinea University of Technology,

Lae Papua, New Guinea; PNG Institute of

Architects, Port Moresby, Papua, New Guinea

Alvar Aalto Symposium, Helsinki, Finland

1994

Virginia Polytechnic Institute/State University

Blacksburg, USA; Virginia Design Forum;

GSFA University of Pennsylvania; Bartlett

School, London, UK; University of

Technology, Helsinki, Finland; School of

Architecture/SAFA Oulu, Finland; Architecture

School/Association of Architects, Stockholm,

Sweden; Association of Architects, Basel,

Switzerland

1995

AIA/Rice Design Alliance, Houston, Texas;

AIA Salt Lake City; Pompidou Centre, Paris;

Architectural Association London, UK;

Schools of Architecture in Tubingen,

Darmstadt, Karlsruhe, and Kaiserslautern,

Germany and Venice, Italy; Alvar Aalto

Symposium, Jyvaskyla, Finland

1996

Hawaii University; Jerusalem Seminar in

Architecture, Israel

1997

Mississippi AIA; University of Texas,

Austin;Texas A&M; University of Florida;

University of California at Berkeley;

University of Mississippi; PNG Institute of

Architects, Port Moresby, Papua, New Guinea

1998

CalPoly Pomona, University of Washington,

Seattle; Alaska Design Forum, Anchorage and

AIA Fairbanks, Alaska

1999

Danish Academy of Architects/School of

Architecture, Copenhagen, Denmark and

Aarhus; Columbia University/AIA New York;

Montana State University/AIA, Bozeman, MT;

Lloyd Rees Lecture Museum of

Contemporary Art, Sydney; Canberra

Museum and Gallery

2000

Maki Lecture, Washington University, St.

Louis, MO; University of California, Los

Angeles; Portland Museum, Maine;

Federation of Icelandic Architects,

Reykjavik, Iceland; Alvar Aalto

Symposium, Jyvaskyla, Finland.

2001

Lectures in Caracas, Venezuela;

Lecce, Italy; University of North

Carolina, Raleigh; University of

Virginia, Charlottesville; Buenos Aires,

Argentina; Santiago and Valparaiso,

Chile; Royal IArchitectural Institute of

Canada, Halifax, Nova Scotia

2002

Lectures in Bangkok, Thailand;

University of Washington in St. Louis,

Mo; University of Arizona, Tucson;

University of Kansas, Lawrence;

Danish Academy of Fine Arts,

Fredericia, Denmark; TAF

International Celebration of

Architecture, "RÿROS 2002" Norway

Chronological List of Selected

Projects and Built Works

1960-1962

Devitt house, Beacon Hill, Sydney

(altered since completion)

1968-1972

Daphne Murcutt house, Seaforth,

Sydney

1968-1969

Glenn Murcutt house, Mosman, Sydney

(alteration/addition; altered since

completion)

1968-1970

Glenn Murcutt house, Beauty Point,

Sydney (project)

1969-1972

Douglas Murcutt house, Belrose, Sydney

1970

Robertson house, East Killara, Sydney

(alteration/addition; altered since

completion)

Hinder house, Gordon, Sydney

(alteration/addition to a Syd Ancher

house)

1971

Lowy house, Mosman, Sydney

Walker house, Killara, Sydney

(alteration/addition to a Syd Ancher

house)

1972

Needham house, Woy Woy, Sydney (in

association with Guy Maron)

Restaurant Paragon, Katoomba, New

South Wales (renovation)

Omega Project house for Ralph

Symonds Homes

Cullen house, Balmain, Sydney

(completed 1974)

Armstrong house, Grenfell, NSW

(completed 1980)

1972-1973

Laurie Short house, Terrey Hills,

Sydney, NSW

1973

Luscombe house, Bayview, Sydney

Wallis house, Manly, Sydney

(renovation/addition)

1974

Marie Short house, Kempsey, New South

Wales (completed 1975)(extension 1980)

Hetherton house, Balmain, Sydney

(completed 1982)

1975

Jureidini house, Mosman, Sydney

(alteration/addition of Murcutt's former

house)

Leaves of Iron - Glenn Murcutt by Philip Drew

Three Houses - Architecture in Detail by E. M. Farrelly

Glenn Murcutt - Works and Projects by Francoise Fromonot

Touch This Earth Lightly by Philip Drew

Glenn Murcutt by Flora Giardiello Postiglione

Glenn Murcutt - A Singular Architectural Practice

Practice Images Group - to be published May 2002

Publications

2 1

1975

Meehan house, Kempsey, New South

Wales (completed 1977)

Redmond house, Giralang, Canberra

(completed 1977)

1976

Stitt house, Longueville, New South Wales

(alteration/addition; completed 1977)

Done house, Mosman, Sydney (alteration/

addition; completed 1978)

1977

Ockens house, Cromer, Sydney

(completed 1978)

Reynolds house, Woollahra, Sydney

(completed 1979)

Nicholas farm house, Mount Irvine, New

South Wales (completed 1980)

Berowra Waters Inn, Sydney (phase 1,

completed 1978)

1978

Young house, Jindabyne, New South

Wales (alteration/addition; completed 1980;

since altered)

Carruthers farmhouse, Mount Irvine, New

South Wales (completed 1980)

1979

Project house for Devon-Symonds Pty

Ltd, North Rocks, New South Wales

Isherwood house, Mosman, Sydney

(alteration/addition; since altered)

Hawksford Point Piper, Sydney (project)

Nielsen Park Kiosk, Vaucluse, Sydney

(project)

Crouch house, Cobbity, Sydney (in

association with Wendy Lewin and Alec

Tzannes; project)

Offices for Marsh & Freedmann,

Woolloomooloo, Sydney (conversion,

completed 1980, since altered)

Hornery house, Warrawee, Sydney (in

association with Civil & Civic, completed

1982)

1980

Competition for the renovation of the

'Engehurst' villa designed by the architect

John Verge, in association with the

conference 'Pleasures of Architecture'

organized by Royal Australia Institute of

Architects, Sydney

Markovic house, Palm Beach, Sydney (in

association with Wendy Lewin and Alex

Tzannes; project)

Fountain house, McMahons Point, Sydney

(in association with Wendy Lewin and Alec

Tzannes)

Uther house, Hunters Hill, Sydney

Murcutt-Robertson house, Kempsey, New

South Wales (extension to Marie Short

house)

Carpenter house, Point Piper, Sydney

(completed 1983)

Zachary's Restaurant, Terrey Hills,

Sydney (completed 1983)

Ball-Eastaway house and studio, Glenorie,

Sydney (Graham Jahn and Rad Milatich,

assistants; Alec Tzannes, site visits;

completed 1983)

1981

Ward house, Hornsby Heights, Sydney

(project)

Maestri house, Blueys Beach, New South

Wales

Museum of Local History and Tourist

Office, Kempsey, New South Wales

(phase 1 completed 1982)

Fredericks house, Jamberoo, New South

Wales (Wendy Lewin, assistant;

completed 1982)

New Catholic Presbytery and Community

Hall, Mona Vale, Sydney (Graham Jahn,

assistant; completed 1983)

Munro house, Bingara, New South Wales

(Graham Jahn, assistant; completed 1983)

Rabbit house, Merewether, New South

Wales (Graham Jahn, assistant; completed

1983)

1982

Ramsden & Kee house, Blackheath, New

South Wales (completed 1983)

Newport house, Hunters Hill, Sydney

(addition)

Berowra Waters Inn, Sydney (phase 2;

Graham Jahn, assistant; completed 1983)

Magney house, Bingie Bingie, South Coast,

Sydney (completed 1984)

1983

Finlay house, Hallidays Point, New South

Wales (John Smith, assistant; Alec

Tzannes, site visits; completed 1984)

Littlemore house, Woollahra, Sydney

(Wendy Lewin, assistant; completed 1986)

Aboriginal Alcoholic Rehabilitation Centre,

Bennelong's Haven, Kinchela Creek, New

South Wales (project 1983-85)

Pratt house, extension of Raheen, Kew,

Melbourne (in association with Melbourne

architects Bates, Smart & McCutcheon;

completed 1994)

1985

Edwards-Neil house, Lindfield, New South

Wales (project 1985-88)

Herbarium and Visitors Centre, Botanical

Gardens, Wollongong, New South Wales

(project)

1986

Field Study Centre, Cape Tribulation, Far

North Queensland (project 1986-87)

Harrison house, Waverley, Sydney (in

association with Alec Tzannes; phase 1

completed 1989; phase 2 completed 1991)

Magney house, Paddington, Sydney

(renovation; James Grose, site assistant;

Andrew Mc Nally and Sue Barnsley,

landscape architects; completed 1990)

1987

Carey house, Springwood, New South

Wales

Minerals and Mining Museum, Broken Hill,

New South Wales (project 1987-89; Reg

Lark, assistant)

Museum of Local History, Kempsey, New

South Wales (phase 2, completed 1988)

Cultural Centre for the University of North

Solomon, Arawa, Papua, New Guinea

(project 1987-88)

Offices for Marsh & Freedman, Redfern,

Sydney (renovation/conversion, completed

1989)

1988

Done house, Mosman, Sydney (Reg Lark,

assistant; completed 1991)

Meagher house, Bowral, New South Wales

(Andrea Wilson, assistant; James Grose,

site assistant; completed 1992)

Muston house, Seaforth, Sydney

(completed 1992)

1989

Simpson-Lee house, Mount Wilson, New

South Wales (completed 1994)

1991

Marika-Alderton house, Aboriginal

Community, Yirrkala, Eastern Arnhem

Land, Northern Territory (completed 1994)

1992

Preston house, St. Ives, Sydney (Sue

Barnsley, landscape architect;

(completed 1994)

Landscape Interpretaion Centre, National

Park of Kakadu, Northern Territory (in

association with Troppo Architects,

Darwin; completed 1994)

2 2

Murcutt guest studio, Kempsey, New

South Wales

1993

Conversion of Customs house

(architects Mortimer Lewis, James

Barnet, Walter Liberty Vernon, then

George Oakschott) Circular Quay,

Sydney (in association with Wendy

Lewin of Lewin Tzannes Architects)

Williams house, Pearl Beach, New South

Wales

1996

Douglas Murcutt house, Woodside,

Adelaide, South Australia (completed

1999)

Olsen house, Norton Summit, South

Australia

Ken and Judy Done Gallery, Mosman,

Sydney

Hardeman-McGrath house, Birchgrove,

Sydney (extension with Nicholas

Murcutt)

Taylor house, Barrington Tops, New

South Wales

Another Aboriginal house, Yirrkala,

Northern Territory (completed 1998-99)

1995-98

Schnaxl house, Newport, Sydney

1998

House at Mt. White, New South Wales

(project)

1996-98

Beckwith/Deakins Terrace house,

Paddington, Sydney

1996-99

'Bowali' Visitors Information Centre,

Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory

(with Troppo Architects, Darwin, NT)

Arthur & Yvonne Boyd Education Centre,

Riversdale, New South Wales (in

collaboration with Wendy Lewin and

Reg Lark)

1997-2001

House Bowral, Southern Highlands, NSW

1997-2000

C. Fletcher & A. Page house, Kangaroo

Valley

1997-

Lightning Ridge Community Facility

2002-

Works in Progresss or Under Contruction

New house, Yorke Peninsula, South

Australia

New house, Merewether, Newcastle, New

South Wales

Winery, Lake George, New South Wales

Sales Outlet, Winery, Mudgee, New

South Wales (in association with Wendy

Lewin)

Eco-Hotel, Great Ocean Road, Victoria

(in association with Wendy Lewin)

Convention/conference/accommodation

facility, Barrington Tops, New South

Wales (in association with Wendy Lewin)

New house, Kew, Melbourne, Victoria

Extensions to two houses at Mt. Irvine,

New South Wales (early farmhouses

designed in 1978 by Glenn Murcutt)

Extension to farmhouse at Jamberoo,

designed by Glenn Murcutt in 1981-82

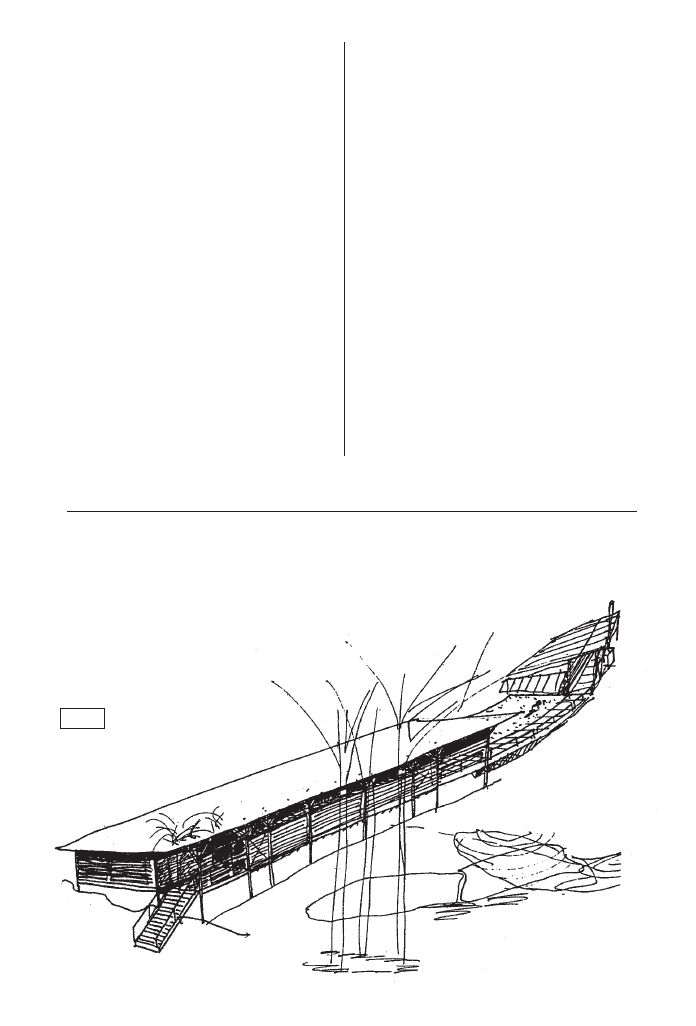

Concept Sketch of the Simpson-Lee House

by Glenn Murcutt

Mount Wilson, New South Wales

1989-1994

Films/Videos

Touch the Earth Lightly by Peter Hyatt,

Melbourne, Australia

The Tin Man by Catherine Hunter,

Channel 9 Network Australia

fig.

11

23

Ball-Eastaway House

Glenorie, Sydney, NSW

Drawings and Sketches by Glenn Murcutt of Selected Projects

C. Fletcher & A. Page House

Kangaroo Valley, NSW

Magney House

Paddington, Sydney, NSW

fig. A1

fig. A2

fig. D2

fig. D1

fig. C2

fig. C3

24

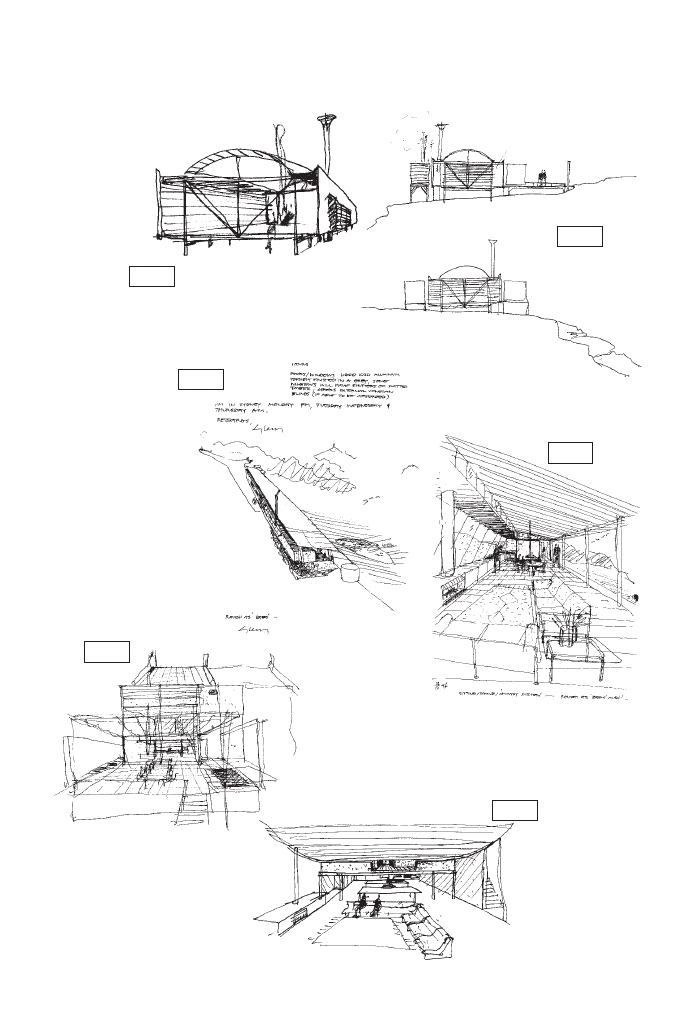

Minerals and Mining Museum

Broken Hill, NSW

fig. F2

fig. F1

fig. F3

157b

Photo by Glenn Murcutt

The model for the entrance to the Museum.

25

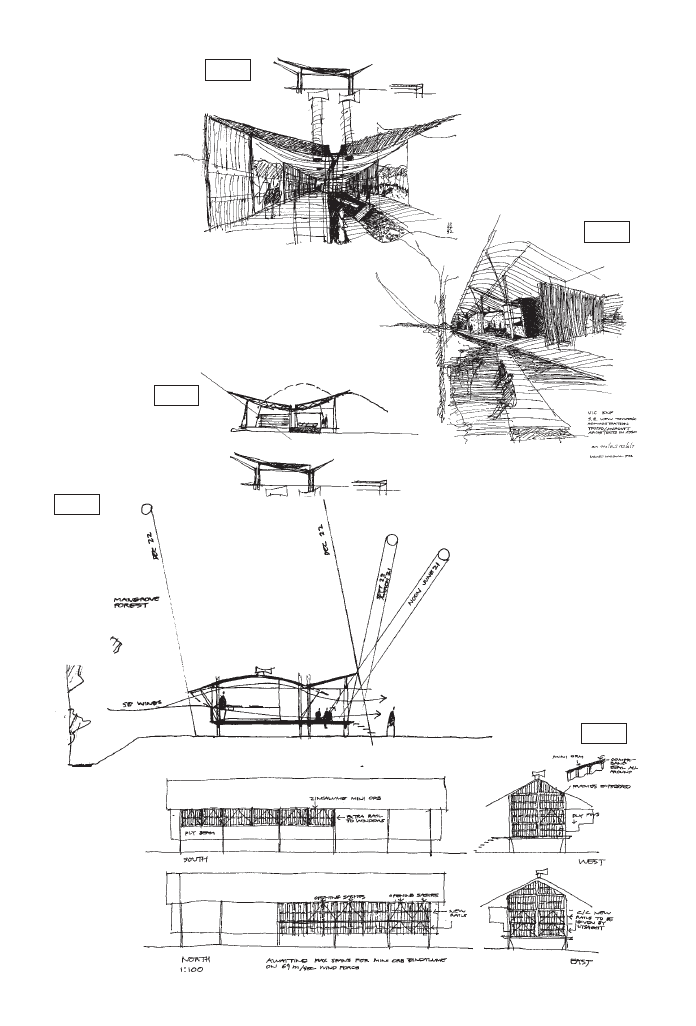

'Bowali' Visitors Information Centre

Kakadu National Park

Northern Territory

(Project in collaboration with

Troppo Architects,

Darwin, Northern Territory)

Marika- Alderton House

Yirrkala Community,

Eastern Arnheim Land

Northern Territory

fig. B3

fig. B2

fig. G2

fig. G3

fig. G1

26

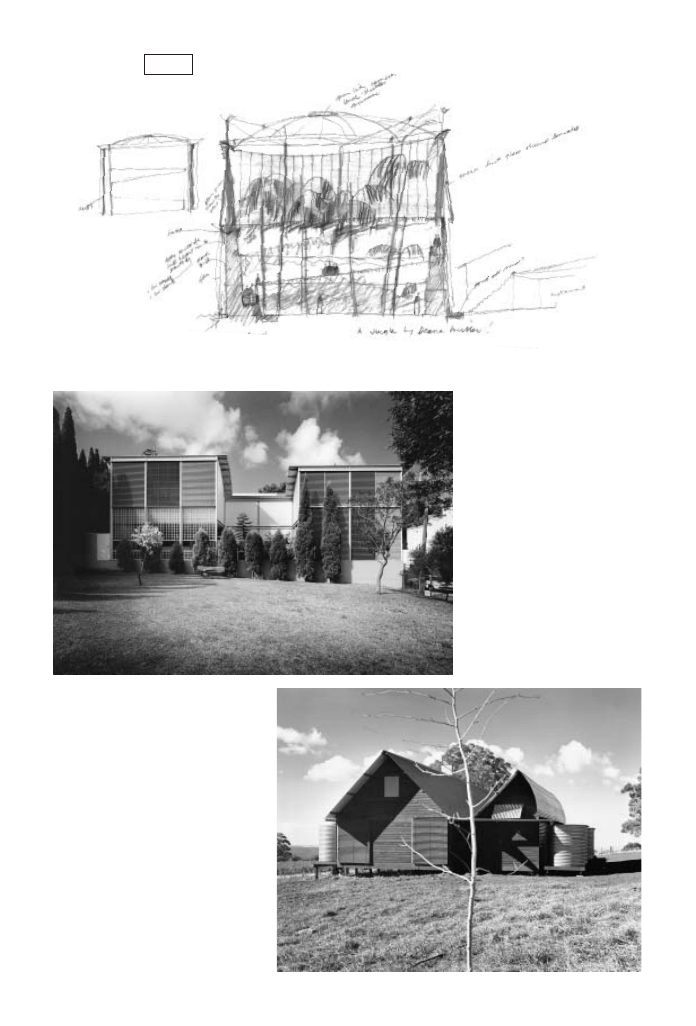

Littlemore House

Woollahra, Sydney, NSW

Photo by Max Dupain

Photo by Max Dupain

Herbarium and Visitors Centre

Botanical Gardens

Woolongong, NSW

fig. 25D

25C

25A

Nicholas Farm House

Mount Irvine, NSW

27

Laurie Short House

Terrey Hills, Sydney

1972-1973

Photo by Max Dupain

Photo by Max Dupain

Photo by Max Dupain

27A

27C

27B

28

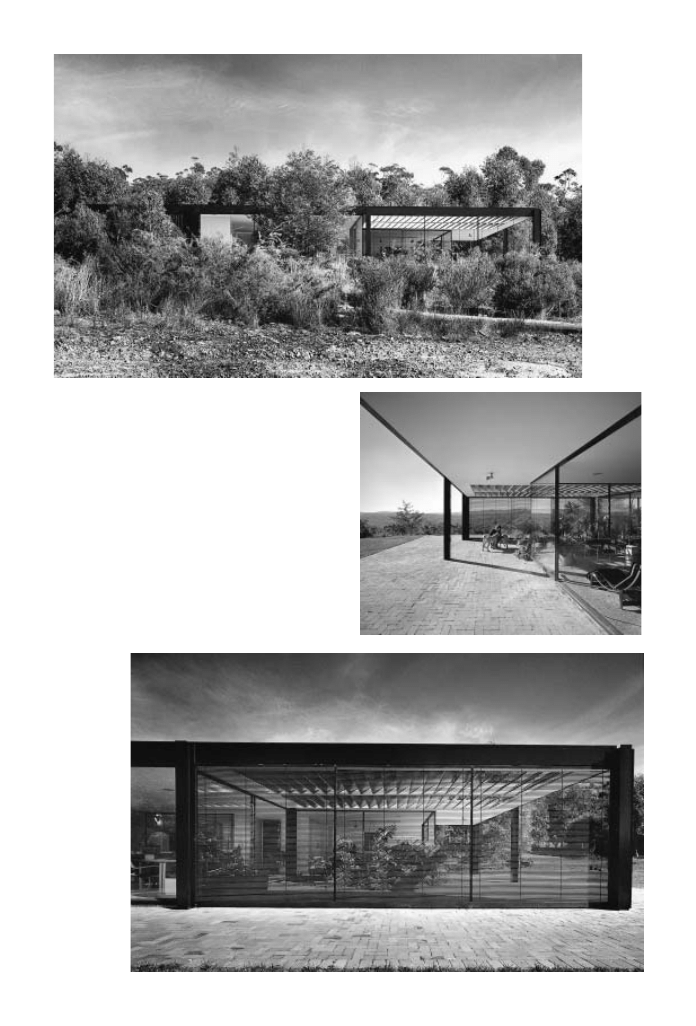

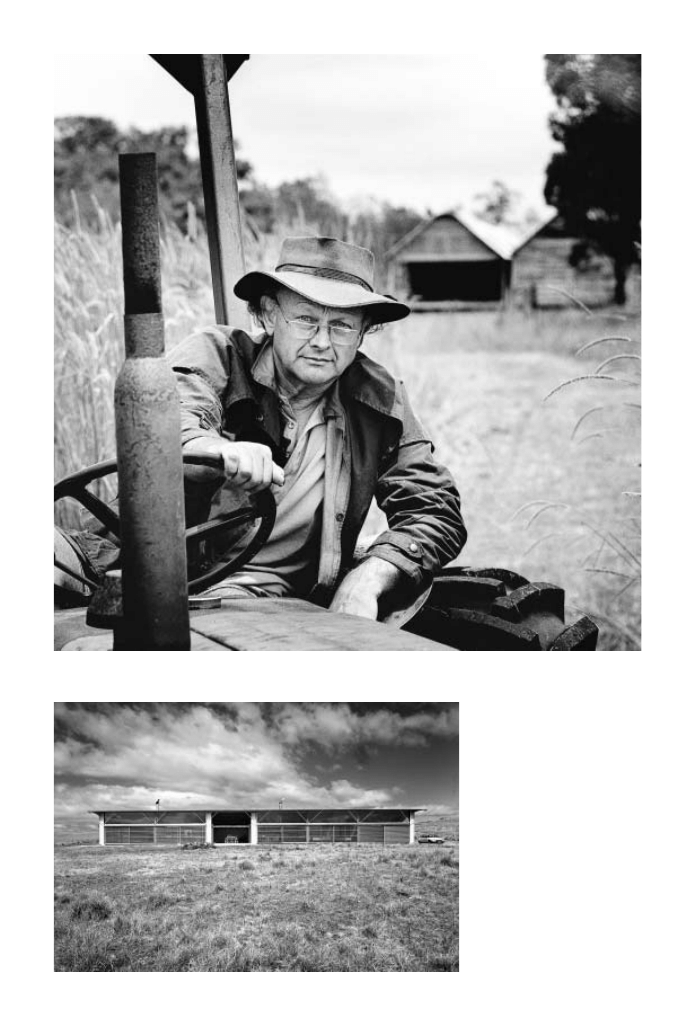

Glenn Murcutt on tractor for his

other activity, farming.

Magney House

Bingie Bingie

South Coast, NSW

1982-1984

Photo by Anthony Browell

28A

Photo by Max Dupain

28B

29

"Michelangelo is often thought of principally as a sculptor and painter, rather

than as an architect," says J. Carter Brown, chairman of the jury that selects the

Pritzker Laureate each year. "But right in the religious and political center of Rome,

he was commissioned to design a remarkable architectural project at the top of the

Capitoline Hill, the Campidoglio, Rome's ancient Capitol Hill. It is a place spanning

more than 2000 years of history. In 1471, Pope Sixtus IV donated large bronze statues

to the Campidoglio, creating what is now arguably the oldest public museum in the

world. The She-wolf suckling the two traditional founders of Rome, Romulus and

Remus, was placed inside the Palazzo dei Conser vatori, and became the symbol of

the city. With Papal authority, Michelangelo moved the equestrian statue of Marcus

Aurelius to the center of the plaza, and created a magically beautiful star-shaped

pavement design. (His design was not in fact actually completed until 1940; and to

conserve the statue, one of the great monuments of antiquity, the original has been

moved into the adjoining museum, and a faithful replica installed in the center of the

plaza, following Michelangelo's design.)"

The guests assembling from around the world for the Pritzker Prize will walk

up the monumental ramp (cordonata) to the top of the Capitoline Hill, where chairs

will be placed on the piazza facing the central building (the Palazzo Senatorio which

today houses the offices of the mayor and the city council chambers), where, in front

of the fountain, the ceremony will take place to present the $100,000 Pritzker

Architecture Prize to Australian architect Glenn Murcutt. On either side of the piazza

is the Palazzo dei Conser vatori and the Palazzo Nuovo, both of which comprise the

Capitoline Museum.

Following the ceremony, guests will be transported to the Palazzo Colonna

for a reception and dinner. The first historical information on the Colonna family

residence dates from the 13th century. Since that time, the family has provided

numerous princes of the Catholic Church, including several Cardinals and Popes.

Today, the family home doubles as a private art gallery for the art collections that

span six centuries.

The international prize, which is awarded each year to a living architect for

lifetime achievement, was established by the Pritzker family of Chicago through their

Hyatt Foundation in 1979. Often referred to as “architecture’s Nobel” and “the

profession’s highest honor,” the Pritzker Prize has been awarded to seven Americans,

and (including this year) nineteen architects from thirteen other countries. The

presentation ceremonies move around the world each year paying homage to the

architecture of other eras and/or works by previous laureates of the prize.

Thomas J. Pritzker, president of The Hyatt Foundation, in expressing gratitude

to the Mayor of Rome, Honorable Walter Veltroni, for making it possible to hold

the event in this remarkable setting, stated, “Last year, we were in Monticello, the

home designed by one of the fathers of our country, Thomas Jefferson. It is relevant

that Jefferson's American architecture talents owed a primary debt to Italy. He was

very much inspired by the 16th century Italian architect Andrea Palladio's book, I

Quattro Libri dell'Architettura; and the dome of Monticello was modeled after the

ancient temple of Vesta in Rome, just as the dome of the library of his University of

Virginia was inspired by Rome's Pantheon." Pritzker went on to describe how Jefferson

wrote to a friend,, "Roman taste, genius, and magnificence excite ideas." "This year,"

Michelangelo's Campidoglio in Rome

Will Be the Setting for the 2002 Pritzker Prize Ceremony

30

Pritzker continued, "we will be in Rome, virtually the cradle of much of our western

civilization, and more specifically, in a space designed by Michelangelo in the 16th

century that is still functioning today as the seat of government for this great city.

And this magnificent setting overlooks the heart of the ancient city, the Roman

Forum."

Coinciding with the Pritzker Architecture Prize ceremony being held in Rome,