The effects of Chinese calligraphy handwriting and relaxation training

in Chinese Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma patients: A randomized

controlled trial

Xue-Ling Yang

,

, Huan-Huan Li

, Ming-Huang Hong

, Henry S.R. Kao

a

Department of Psychology, Sun Yat-Sen University, Xin gang xi Road 135, Guangzhou 510275, Guangdong, China

b

Department of Psychology, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

c

Cancer Center of Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China

d

University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

International Journal of Nursing Studies 47 (2010) 550–559

A R T I C L E I N F O

Article history:

Received 7 January 2009

Received in revised form 1 October 2009

Accepted 23 October 2009

Keywords:

Calligraphy

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

Psychological intervention

Relaxation training

A B S T R A C T

Background: Chinese calligraphy handwriting is the practice of traditional Chinese brush

writing, researches found calligraphy had therapeutic effects on certain diseases, some

authors argued that calligraphy might have relaxation effect.

Objectives: This study was to compare the effects of calligraphy handwriting with those of

progressive muscle relaxation and imagery training in Chinese Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

patients.

Design and participants: This study was a randomized controlled trial. Two hundred and

eighty-seven Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma patients were approached, ninety (31%) patients

were recruited and randomized to one of the three treatment groups: progressive muscle

relaxation and guided imagery training group, Calligraphy handwriting group, or a Control

group. Seventy-nine (87.8%) completed all of the outcome measures.

Outcome measures: The primary treatment outcome was the changes of physiological

arousal parameters measured by pre- and post-treatment differences of heart rate, blood

pressure and respiration rate. The secondary outcomes included: modified Chinese version

of Symptom Distress Scale, Profile of Mood State-Short Form, and Karnofsky Performance

Status measured at baseline, during treatment (after the 2-week intervention), post-

treatment (after the 4-week intervention) and after a 2-week follow-up. Effectiveness was

tested by repeated measure ANOVA analyses.

Setting: Cancer centre of a major university hospital in Guangdong, China.

Results: Results showed that both of calligraphy and relaxation training demonstrated

slow-down effects on physiological arousal parameters. Moreover, calligraphy practice

gradually lowered participants’ systolic blood pressure (simple main effect of time at pre-

treatment measure, p = .007) and respiration rate (p = .000) at pre- and post-treatment

measures as the intervention proceeded, though with a smaller effect size as compared to

relaxation. Both of calligraphy and relaxation training had certain symptom relief and

mood improvement effects in NPC patients. Relaxation was effective in relieving symptom

of insomnia (p = .042) and improving mood disturbance, calligraphy elevated level of

concentration (p = .032) and improved mood disturbance.

Conclusions: Similar to the effects of relaxation training, calligraphy demonstrated a

gradually build-up physiological slow-down, and associated with heightened concentra-

tion and improved mood disturbance. Calligraphy offered a promising approach to

improved health in cancer patients.

ß

2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +86 20 84114265x807; fax: +86 20 84114266.

E-mail address:

(H.-H. Li).

Contents lists available at

International Journal of Nursing Studies

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/ijns

0020-7489/$ – see front matter ß 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:

What is already known about the topic?

There were documented treatment-related symptoms

and mood disturbance in NPC patients, but less is done to

relieve their symptom distress and mood disturbance in

China.

Relaxation training was effective in reducing treatment-

related symptoms and improving patients’ mood dis-

turbance and quality of life.

Calligraphy had some therapeutic effects on certain

diseases but less is known about its applicability and

acceptability among cancer patients.

What this paper adds

Similar to the effects of progressive muscle relaxation

and guided imagery training, calligraphy handwriting

demonstrated slow-down effects on physiological arou-

sal parameters, and was effective in heightening cancer

patients’ concentration level as well as improving their

mood disturbance.

Compared to that of relaxation training, calligraphy had a

gradually build-up effect in lowering physiological

arousal, although with a smaller effect size, which was

partly due to the characteristics of calligraphy hand-

writing practice and Chinese characters.

Chinese calligraphy handwriting offers a promising

approach to improved health in cancer patients.

1. Introduction

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma (NPC) is one of the most

common cancers in Southeast China, Taiwan and Hon-

gkong, with approximately 10–30 out of 100,000 people,

mostly men, diagnosed in Guangdong province yearly (

). NPC diagnosed at an early stage has relatively

better prognosis than most cancers due to advances in

medical care, especially in radiotherapy (RT) medicine

(

). However, high levels of depression and

anxiety in NPC patients had been observed in hospitalized

settings (

). One of the reasons was that the

acute symptoms related to intense RT treatment had

significant impact on NPC patients’ everyday experiences

(

). These distressful experiences

often involved severe pain in oral-pharyngeal cavity, dry

mouth and difficulty to swallow, noticeable alteration in

appearance,

difficulty

opening

mouth

and

hearing

damages (

).

Among psychosocial interventions for reducing treat-

ment-related symptoms and mood disturbance, relaxation

and imagery training were most investigated in controlled

trials, partly due to its low cost, ease of use and having few

if any negative side effects (

). Studies had

observed progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) and guided

imagery (GI) training could reduce anxiety and improve

quality of life among cancer patients (

), could reduce mood disturbance and emotional

suppression in breast cancer patients (

Findings of these studies conformed to the results of a

review article (

) that found relaxation

had significant beneficial effects on treatment-related

symptoms (such as nausea, pain, vomiting), emotional

adjustment (such as anxiety, depression, hostility, tension,

fatigue, confusion, vigor, overall mood), and physiological

arousal parameters (such as heart rate, blood pressure and

respiration). In view of these findings, the author

suggested that relaxation training should be implemented

into clinical routine for cancer patients in acute medical

treatment.

Art therapy, a complementary and alternative treatment

modality, had been proven to have therapeutic effects in

cancer patients (

Gotze et al., 2009; Svensk et al., 2009

).

Proponents of art therapy believed that the uninhibited

expression of feelings and emotions through art might help

to release the fear, anxiety and anger that many cancer

patients experienced. Art could also be viewed as a

distraction to the pain and discomfort of disease, allowing

patient relief from stress. Shufa, or Chinese calligraphy was

the writing of Chinese characters by hand using a soft-tipped

brush, was traditionally regarded in China as one of the fine

arts (

). To date, empirical studies on

Chinese calligraphy had been focusing mainly on how to

execute and appreciate it artistically by following the

practical experiences of the great masters. Little systematic

research had been done on the fundamental behaviors

associated with the calligraphy practice, such as visual

perception, emotions and physiological response. The

existing clinical researches on calligraphy handwriting

had found that calligraphy had treatment effects on some

behavioral and psychosomatic diseases, such as Attention

Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children (

), Alzheimer’s disease (

Kao, 2003; Kao et al., 2000a,b

),

hypertension (

Guo et al., 2001; Kao et al., 2001

) and diabetes

II (

). The authors further argued that the act

of brushing caused heightened attention and concentration

on the part of practitioners and resulted in their emotional

stabilization and physical relaxation (

The main purposes of the present study were to

compare the effects of calligraphy handwriting on NPC

patients’ physiological arousal parameters, symptom

distress, mood disturbance and functional status with

those of progressive muscle relaxation and imagery

training.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

The study was a longitudinal, randomized, controlled

trial with 2 intervention groups and a control group. A

3 2 4 mixed-effect factorial design was used for

assessing physiological arousal parameters, and a 3 4

mixed-effect factorial design was used for assessing the

secondary outcome measures. The protocol for this study

was approved by the Review Board of the investigator’s

institution.

2.2. Participants and setting

The study was carried out from June 2007 to March

2008 in the in-patient department of Cancer Centre of a

X.-L. Yang et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 47 (2010) 550–559

551

major university hospital in Guangdong, China. Patients

diagnosed with NPC based on the American Joint

Committee on Cancer Staging (

), and sched-

uled for RT, aged 18–80 were eligible for this study.

Exclusionary criteria included: patients who had finished

surgical treatment in the last 3 months; patients who were

unable to read and write Chinese with a brush (e.g.,

illiteracy or physical disability); patients with cardiovas-

cular or respiratory diseases, e.g., essential or secondary

hypertension (systolic blood pressure equal to or greater

than 140 mmHg, and/or diastolic blood pressure equal to

or greater than 90 mmHg), abnormal heart rate or

abnormal

respiration.

287

eligible

patients

were

approached and 90 (31%) consented to participate. The

major reasons for refusal included no time or interest,

feeling lack of energy and concentration.

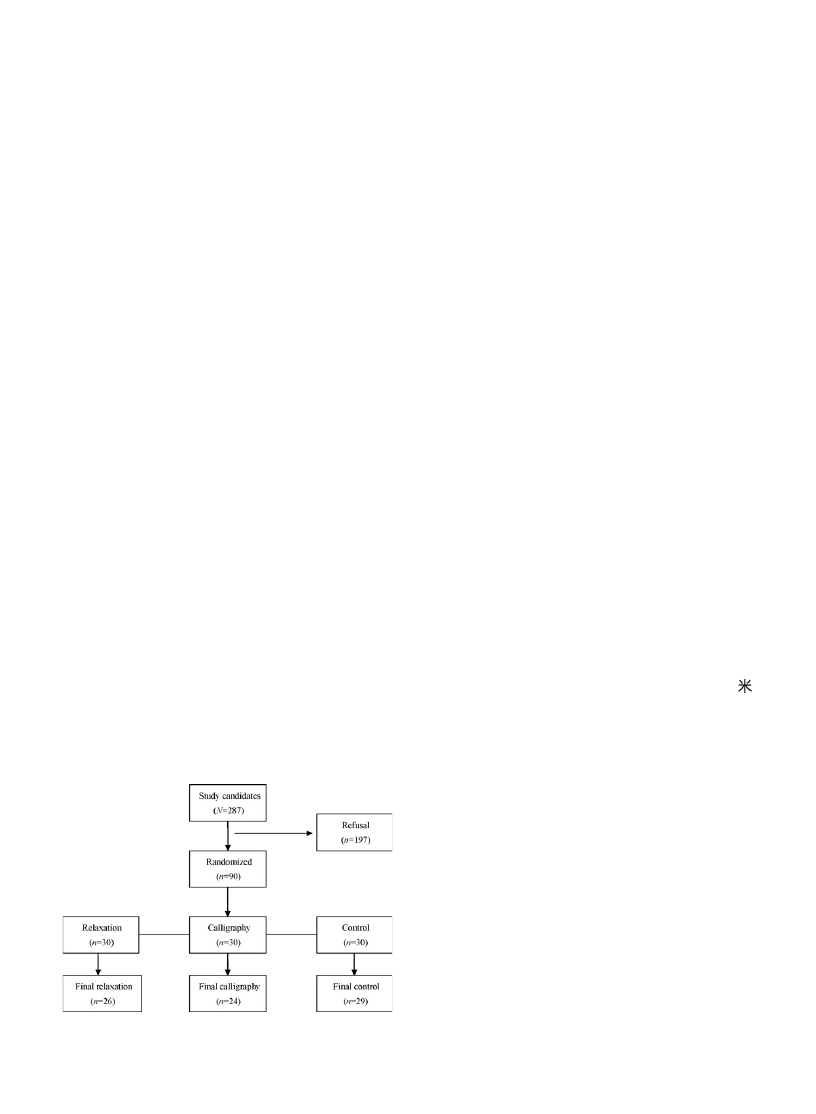

shows the flow chart of participants of this study.

90 patients who signed the informed consent were

included in the study and randomly assigned to one of

the three treatment groups: Relaxation (n = 30), Calligra-

phy (n = 30), and Control (n = 30). The randomization

procedure was accomplished by a computer-generated

table in blocks of 3 without any restriction or stratification.

By the end of the study, a total of 79 patients completed the

final assessments: Relaxation (n = 26), Calligraphy (n = 24),

Control (n = 29).

2.3. Procedures

To control for the potentially important confounding

variables that might have an impact on the outcome

measures, patients were monitored for any medication

usage, e.g., antidepressant, anti-hypertension drugs. No

such medication usage was reported. After the completion

of the final assessment, each participant was encouraged to

give feedback on effectiveness of the programs and

suggestions to improve the intervention procedure. The

reasons of participant dropout were also recorded.

2.4. Intervention

2.4.1. Relaxation training

The relaxation training lasted 30 min per day for 4

consecutive weeks; 20-min progressive muscle relaxation

(PMR) was followed by 10-min guided imagery (GI). PMR

was administered by a clinical therapist in a separate, quiet

and adequately lit inpatient ward following the abbreviated

form of Jacobsen’s procedure developed by

. For this study, the instructions led

participants in tensing and relaxing 12 major muscle groups

working from the hands and arms up to the head and down

to the feet. Participants were asked to focus on the contrast

between sensations of muscle tension and relaxation. The GI

training was delivered by a pre-recorded MP3 audio file read

by a female research associate following a script, while the

participant was in a relaxed position with the eyes closed.

The script began with suggestions for relaxation and deep

breathing, and then encouraged the participant to imagine a

pleasant special place without any pain and symptoms.

Continuous soft instrumental music provided background

to the narrator’s voice.

2.4.2. Calligraphy practice

The participants in Calligraphy Group practiced Chinese

calligraphy in a quiet, adequately lit inpatient room led by a

retired language teacher, who was a senior calligrapher. The

time duration of calligraphic writing was 30 min per day for 4

consecutive weeks as the same as that of relaxation group.

The content of Chinese calligraphy character was chosen

randomly in a handbook of calligraphy writing. To control for

the influence of emotional positiveness of the Chinese

character, rather than the calligraphy practice intervention

on outcome measures, especially on mood status ratings, 20

characters were randomly chosen in the handbook to

evaluate the emotional properties of these characters on a

5-point Likert scale (‘‘1’’ represented ‘‘very negative’’ and ‘‘5’’

represented ‘‘very positive’’) by 60 college students. The

result showed that the emotional positiveness of the sample

characters were 3.118 0.585. The calligraphic writing

involved brush handwriting by tracing the strokes and

structures of the characters displayed in a mixture of commonly

used calligraphic styles, i.e., the calligraphic brush was middle-

sized, the length of the pen was 28 cm, a 11 by 11 cm ‘‘

’’-

shaped pane was printed on the calligraphic rice paper.

2.5. Baseline and outcome measures

At baseline, demographic and clinical data were

collected either from the patients or from the medical

records prior to the interventions, and the consent to

access the patients’ medical records had been obtained

from the medical staff. Demographic information includ-

ing age, sex, education, marital status and clinical

information regarding disease and treatment modality

were collected on a demographic form.

2.5.1. Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was the change of physiological

arousal parameters assessed by heart rate (HR), blood

pressure (BP), and respiration rate (RR), which were

measured at pre- and post-treatment per treatment day,

5 days a week (i.e., Monday to Friday), and for 4

consecutive weeks. HR and BP were measured by Omron

Upper Arm Digital Sphygmomanometer, Model HEM-

7051. The RR was counted by a clinical nurse using a

Fig. 1. Flow chart of participants.

X.-L. Yang et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 47 (2010) 550–559

552

stopwatch who was blind to the study hypotheses. To

avoid the impact of diurnal fluctuation of physiological

parameters, the treatments and measures were set at fixed

time period across days, i.e., 10–12 am, or 3–5 pm, or 6–

8 pm. The measures were averaged to calculate a ‘‘pre’’

(pre-treatment) and ‘‘post’’ (post-treatment) score based

on at least 4 days of measures each week, otherwise the

data would be considered invalid. To avoid the influence of

physical activity on physiological parameters, participants

were asked to sit quietly for 5 min before measurements.

The time interval between pre- and post-treatment

assessments was 30 min in 3 treatment groups.

2.5.2. Secondary outcome measures

The following secondary psychosocial outcomes were

assessed at baseline, during treatment (i.e., after 2-week

intervention), post-treatment (i.e., after the final fourth

week) and after a 2-week follow-up.

2.5.2.1. Symptom distress. Symptom distress was mea-

sured by the modified Chinese version of Symptom

Distress Scale (SDS). The SDS was one of the first scales

developed to measure the construct of symptom distress,

defined as ‘‘the degree of discomfort from the specific

symptom being experienced as reported by the patient’’

(

). Studies have shown that

levels of symptom distress could be a significant predictor

of survival in patients with variety types of cancer (

and Sloan, 1995; Frederickson et al., 1991

). The original

SDS was a 13-item self-rating scale including: frequency

and intensity of nausea, appetite, insomnia, frequency and

intensity of pain, fatigue, bowel pattern, concentration,

appearance, breathing, outlook and cough. In previous

studies, Cronbach’s

a

coefficient of the SDS ranged from

0.70 (

) to 0.92 (

). Most studies reported a Cronbach’s

a

coefficient

greater than 0.80. In the present study, Cronbach’s

a

coefficient of the modified SDS was 0.80, test–retest

reliability over 1 week interval was 0.71.

In the present study, the original SDS was firstly

translated into Chinese according to back-translation

principles (

Baldacchino and Buhagiar, 2003

), and then

modified by adding 5 items that represented NPC patients’

distressing experiences associated with radiotherapy and

chemotherapy. The procedure was performed as follows:

20 NPC patients were interviewed by the researchers to

rate for their most distressing symptoms except the 13

items of original SDS, 5 items were attained upon the 95%

patients’ congruence. The 5 items were added as follows:

dry mouth, difficulty opening mouth, oral ulcer, hearing

difficulty and skin condition.

For the current study, the modified SDS was adminis-

tered consecutive items on 2 pages. The 18 items of the

modified SDS were calibrated scores ranging from 1 (no

distress) to 5 (extreme distress) in accordance with the

original SDS of McCorkle (

2.5.2.2. Mood disturbance. The Profile of Mood State-Short

Form (POMS-SF, Chinese version) was used to assess the

patient’s negative mood states in this study. The Chinese

version of POMS-SF was developed by

,

which consists of 30 items (based on the 65-item

questionnaire in the long form) and contains the same

six subscales: Tension-Anxiety (TA), Depression-Dejection

(DD), Anger-Hostility (AH), Fatigue-Inertia (FI), Confusion-

Bewilderment (CF), and Vigor-Activity (VA). A composite

score, the total mood disturbance (TMD) score, is

computed by summing each of the individual scores for

TA, DD, AH, FI and CF, with vigor scores subtracted to

indicate patients’ total mood disturbance. Each item of the

POMS-SF is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0

(not at all) to 4 (extremely). Cronbach’s

a

coefficient was

0.93 in a 289 hospitalized cancer sample (

). In this study, Cronbach’s

a

coefficient was 0.79.

2.5.2.3. Functional status. Karnofsky Performance Status

(KPS) provided a global indicator of functional status

(

). The scale ranges from

100 (Normal, no complaints, no evidence of disease) to 0

(Dead) with 10-point intervals, each with explicit descrip-

tors. Lower scores indicate greater symptoms and physical

restrictions. Inter-rater reliability between two indepen-

dent nurses was 0.92 in the current study.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint of intervention efficacy was the

change in physiological arousal parameters measured at

pre- and post-treatment, i.e., the significant interaction

effect of Prepost by Group. The secondary endpoints

included SDS scores, POMS-SF subscale scores, and KPS

rating measured at different time points, i.e., the significant

interaction effects of Group and Time.

Outcome data analyses were based on study completers

only. Baseline characteristics were compared among

groups using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for

quantitative variables and chi-square test for qualitative

variables performed by SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS Inc.,

Chicago, IL). The intervention effects on secondary out-

come measures were determined by using two-way

mixed-effects repeated measures ANOVA (RMANOVA)

with Group as between-subjects factor and Time (Time

1, pre-treatment; Time 2, during treatment; Time 3, post-

treatment; Time 4, 2-week follow-up) as within-subject

factor. The intervention effects on physiological para-

meters were assessed by using three-way RMANOVA with

Group as between-subjects factor and Time, Prepost as

within-subject factors. Partial Eta squared values were

reported as measures of effect size. If the sphericity

assumption was not met, the Huynh-Feldt correction

would be applied. Post hoc multiple comparisons were

performed by using the Least Significant Difference (LSD)

adjustment. The Group, Time and Prepost main effect

would be interpreted in light of significant three-way and

two-way interaction and would not be described further.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

A total of 90 NPC patients meeting inclusion criteria were

recruited. The demographic and clinical characteristics of

X.-L. Yang et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 47 (2010) 550–559

553

the sample at baseline (n = 90) assessment were presented

in

. The mean age of the sample was 49.63 10.81,

ranging from 22 to 71 years old. The majority of patients were

male (68.9%), and married (93.3%). Only 31 (34.4%) patients

had more than 9 years of education. 41 (45.6%) patients were

diagnosed with II stage NPC, 49 (54.4%) received a diagnosis of

III stage. All patients received RT as their current treatment.

The overall mean length of hospital stay was 55 9 days. There

was no statistically significant group difference on all of the

demographical and clinical variables.79 patients (87.8%)

completed the programs and provided valid data on outcome

measures. The numbers of dropouts by treatment groups

were: Relaxation, 4; Calligraphy, 6; Control, 1. The rates of

dropout were not significantly different across groups

(p = .140). Of the 11 dropouts, 3 patients (2 in Calligraphy

and 1 in Relaxation) reported that they were too tired to

complete the program, 4 patients (2 in Relaxation and 2 in

Calligraphy) provided insufficient data on physiological

parameters, 1 patient in Calligraphy group and 1 in Control

discharged prematurely from hospital due to economic or

family issues, 2 patients (1 in Relaxation and 1 in Calligraphy)

dropped out due to diminished interest. There were no

significant differences between the completers and non-

completers on demographic and clinical characteristics except

education (non-completers had a higher percentage of

illiteracy (

x

2

(1, n = 90) = 8.39, p = .039). No significant group

difference was found on baseline assessments of physiological

measures, SDS, POMS-SF, and KPS (all p > 0.05).

3.2. Intervention effects on physiological arousal parameters

summarizes the results of repeated measures of

ANOVO. For HR, both of relaxation and calligraphy

intervention significantly lowered participants’ post-treat-

ment heart rate, but no pre-post difference was found in

the control group (Prepost by Group interaction effect,

F(2,76) = 20.67, p = .000, partial

h

2

= .35). The mean change

of Pre-post measure was

1.72 bpm in Relaxation group,

and

1.14 bpm in Calligraphy group. There was no

significant difference on the Pre-post change scores

between the two intervention groups (p > .05).

For systolic blood pressure (SBP), relaxation and

calligraphy intervention significantly lowered partici-

pants’ post-treatment SBP, but no pre-post difference

was found in the control group (Prepost by Group

interaction

effect,

F(2,76) = 35.99,

p = .000,

partial

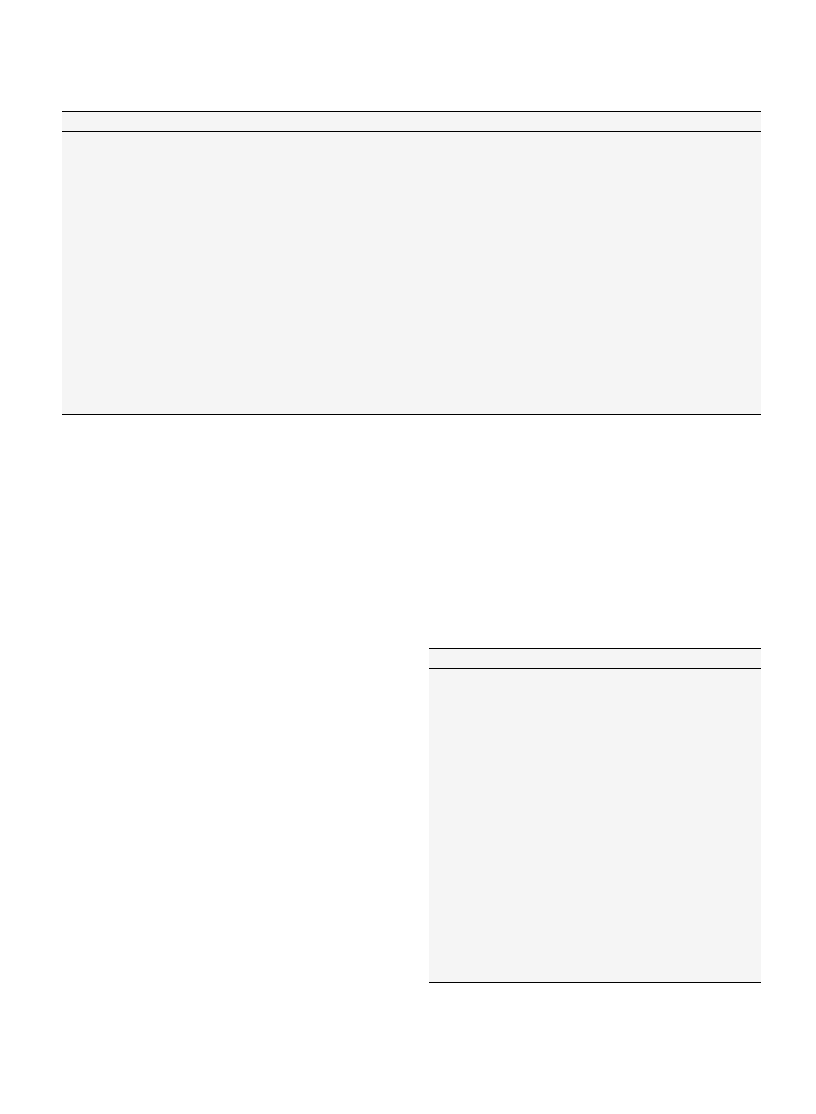

Table 1

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample at baseline measures.

Relaxation

Calligraphy

Control

F

p

Age

0.01

.995

30 or younger

1

2

1

31–55 years

17

15

18

56 years or older

12

13

11

Gender

0.05

.952

Male

21

20

20

Female

9

10

10

Marital status

1.48

.233

Single (divorced)

0

3

2

Married

30

27

28

Education

0.36

.700

6 years or less

7

7

6

7–9 years

13

11

13

More than 9 years

10

12

11

Stage of cancer

0.40

.673

I

0

0

0

II

14

11

14

III

16

19

16

IV

0

0

0

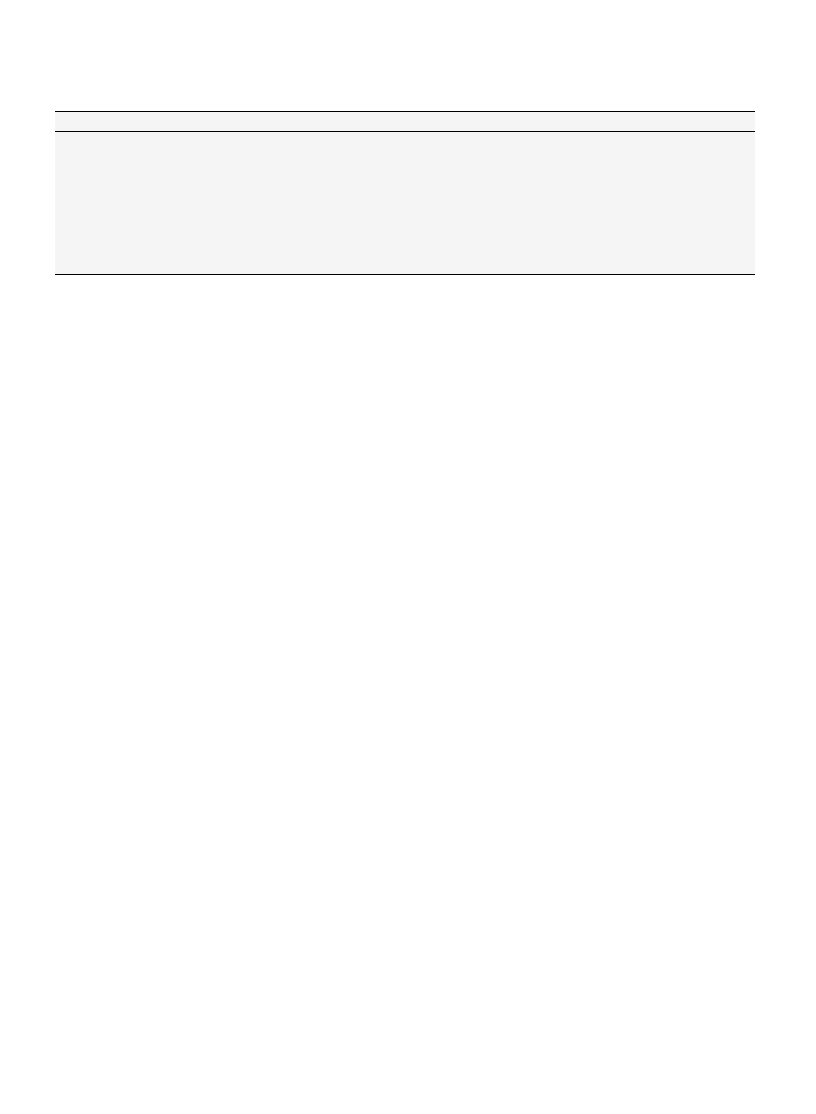

Table 2

Multivariate test of RMANOVA on significant physiological arousal

parameters.

Effects

F

df

p

Partial

h

2

HR

Prepost

81.31

1,76

.000

.517

Prepost Group

20.67

2,76

.000

.352

SBP

Time

8.68

3,74

.000

.260

Prepost

207.58

1,76

.000

.732

Prepost Group

35.99

2,76

.000

.486

Time Prepost

5.51

3,74

.002

.183

DBP

Time

11.67

3,74

.000

.321

Time Group

3.50

6,146

.003

.126

Prepost

355.44

1,76

.000

.824

Prepost Group

80.16

2,76

.000

.678

Time Prepost

6.89

2,74

.000

.218

Time Prepost Group

2.36

6,146

.033

.088

RR

Time

13.73

3,74

.000

.358

Time Group

5.21

6,146

.000

.176

Prepost

331.21

1,76

.000

.813

Prepost Group

95.56

2,76

.000

.715

Time Prepost

4.60

3,74

.005

.157

Time Prepost Group

5.56

6,146

.000

.186

Note: RMANOVA: repeated measure analysis of variance.

HR: heart rate; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood

pressure; RR: respiration rate.

Partial

h

2

: effect size estimate.

X.-L. Yang et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 47 (2010) 550–559

554

h

2

= .49). The mean change of Pre-post measure was

1.68 mmHg in Relaxation group,

1.41 mmHg in Calli-

graphy, and

.23 mmHg in Control. There was no

significant difference on the change scores between the

two intervention groups (p > .05). Post hoc comparison

revealed that calligraphy not only significantly lowered the

post-treatment SBP, but also gradually lowered the pre-

treatment SBP (simple main effect of Time at pre-

treatment measure in Calligraphy group, p = .007), while

relaxation only had treatment effect on post-treatment

measures (p < .05). Regardless of group status, the Pre-post

change score was gradually increased as the intervention

program went on, as was shown by a significant Prepost by

Time interaction (F(3,74) = 5.51, p = .002, partial

h

2

= .18).

For diastolic blood pressure (DBP), the two intervention

groups had different impact on post-treatment measures,

and as the intervention proceeded, the treatment effects

had a trend to increase, indicated by a significant three-

way interaction effect (F(6,218) = 2.28, p = .040, partial

h

2

= .09) and all of the two-way interaction effect (all

p < .05). The mean change of Pre-post measure was

1.76 mmHg in Relaxation group,

1.46 mmHg in Calli-

graphy group, and

.099 mmHg in Control.

For RR, different groups exhibited different patterns of

treatment effect as the intervention proceeded, as indi-

cated

by

the

significant

three-way

interaction,

F(6,228) = 7.10, p = .000, partial

h

2

= .06. Relaxation train-

ing

significantly

lowered

post-treatment

RR

(F(1,76) = 433.41, p = .000, partial

h

2

= .85), the mean Pre-

post change was

1.14 breath per minute, and the change

became larger with the proceeding of intervention,

F(3,74) = 11.83, p = .000, partial

h

2

= .32. In Calligraphy

group, the Pre-post change was significant (F(1,76) = 69.26,

p = .000, partial

h

2

= .48), although with a less magnitude of

.47 breath per minute, and interestingly, the pre-

treatment RR gradually slowed down across time points

(F(3,74) = 8.25, p = .000, partial

h

2

= .06). No two-way

interaction or their main effect was found in Control group.

3.3. Intervention effects on symptom distress and functional

status

The two interventions had no significant effect on

average symptom distress score, which was calculated on

the basis of 18 individual items. However, the interven-

tions had different impacts on the following items of

modified SDS, as was indicated by significant Time by

Group interaction (see

): Insomnia (F(6,193) = 2.34,

p = .042), and Concentration (F(6,206) = 2.43, p = .032).

Relaxation significantly improved insomnia at Time 2

(F(2,76) = 7.56, p = .001) and Time 3 (F(2,76) = 5.97,

p = .004), and the treatment gain was maintained at 2-

week follow-up (F(2,76) = 6.38, p = .003); Calligraphy

group significantly scored lower than the other two groups

at

Time

2

(F(2,76) = 6.34,

p = .003)

and

Time

3

(F(2,76) = 3.69, p = .030) on Concentration, but the treat-

ment gain was not maintained at 2-week follow-up

(p = .066).

Relaxation and calligraphy exerted no significant

treatment effect on KPS ratings, however, patients’

functional status seemed to get better across the time

points, indicated by a significant Time main effect

(F(3,228) = 18.15, p = .000), a reflection of intervention

independent, gradual improvement of patient functioning

throughout the course of treatment.

3.4. Intervention effects on mood disturbance

As detailed in

, relaxation training and calligraphy

practice had different treatment effects on the following

subscales of POMS-SF: TA (F(6,184) = 2.75, p = .021), DD

(F(6,224) = 9.65, p = .000), AH (F(6,166) = 2.77, p = .025), FI

(F(6,174) = 4.77, p = .001), and TMD score (F(6,169) = 9.65,

p = .000), as were indicated by significant Time by Group

interaction effects. Relaxation lowered participants’ TA

score at Time 3, and maintained at follow-up; Relaxation

and Calligraphy group scored lower than Control on DD

subscale at Time 2 and Time 3, but the treatment effect was

not maintained at Time 4; Relaxation and Calligraphy group

scored lower on AH subscale than Control at Time 3, and

maintained at follow-up; Calligraphy lowered FI score at

Time 2 and Time 3, but the treatment gain diminished at

follow-up assessment.

4. Discussion

The present study tested the effects of Chinese

calligraphy handwriting practice in Chinese NPC patients,

Table 3

Significant intervention effects on items of Symptom Distress Scale (mean SD).

Measures

Relaxation

Calligraphy

Control

F

p

h

2

Insomnia

Time 1

2.08 .89

2.13 .99

2.03 .87

0.06

.938

.002

Time 2

1.81 .57

2.33 .57

2.52 .87

7.56

.001

.166

Time 3

1.46 .51

1.92 .58

1.46 .84

5.97

.004

.136

Time 4

1.23 .43

1.75 .68

1.83 .81

6.38

.003

.144

Concentration

Time 1

2.19 .75

2.12 .68

2.00 .76

0.49

.613

.013

Time 2

2.04 .53

2.04 .70

2.48 .79

6.34

.003

.143

Time 3

1.73 .67

1.54 .66

2.03 .68

3.69

.030

.088

Time 4

1.42 .64

1.21 .42

1.59 .63

2.81

.066

.069

Note: Each F tests the simple main effects of Group within each level combination of the other effects shown. These tests are based on the linearly

independent pairwise comparisons among the estimated marginal means.

Partial

h

2

: effect size estimate.

Time 1: measures at pre-treatment; Time 2: during treatment; Time 3: post-treatment; Time 4: 2-week follow-up.

X.-L. Yang et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 47 (2010) 550–559

555

which was compared with an established intervention

approach—progressive muscle relaxation combined with

imagery training and a control group. The primary

outcome analyses revealed that the 4-week calligraphy

practice intervention demonstrated a slow-down effect on

physiological arousal parameters (as was measured by HR,

BP, and RR) similar to those of relaxation training, though

in different patterns. The secondary outcomes analyses

revealed that calligraphy had certain symptom relief and

mood improvement effects in NPC patients, providing

further evidence on the efficacy of calligraphy practice as a

psychosocial intervention alternative.

4.1. Intervention efficacy

First of all, primary outcome analyses revealed that

similar to the effects of relaxation training, calligraphy

practice exerted short-term slow-down effects on physio-

logical arousal parameters, including slower heart rate,

decreased blood pressure, and decelerated respiration.

Moreover, calligraphy practice demonstrated gradually

build-up effects on SBP and RR measures, which were

shown by less magnitude of Pre-post change scores, and

simple main effects of time at pre-treatment measures. The

secondary outcome analyses revealed that calligraphy

improved the patients’ concentration level, reduced their

mood disturbance scores on Depression-Dejection, Anger-

Hostility and Fatigue-Inertia subscales.

Years of experimental investigation had found that

calligraphic handwriting act was capable of producing

improvements in the writer’s visual attention, physical

relaxation, emotional stabilization as well as cerebral

activation. A couple of experiments had been carried out to

assess the physiological changes of the writers during

calligraphic writing (

). Results indicated

that subjects experienced relaxation and emotional calm-

ness when they were writing Chinese calligraphy: their

respiration rate decelerated, heart rate slowed down, and

blood pressure and muscular activities dropped. On the

contrary, EEG data showed that cerebral activities

increased during Chinese calligraphy writing.

The above psychophysiological changes observed dur-

ing the process of calligraphy handwriting could be

explained by the characteristics of calligraphic practice

and Chinese character. The calligraphic writing act

involves one’s bodily function as well as one’s cognitive

activity. Motor control and maneuvering of the brush

follow the character configurations. There is, therefore, an

integration of the mind, body, and character interwoven in

a dynamic graphonomic process (

). This intimate

relationship underlies the interactive effects of Chinese

calligraphic handwriting on the mind and the body of the

writer. In addition, the Chinese character forms a perfect

geometric square pattern incorporating such features as

hole, linearity, symmetry, parallelism, connectivity, and

orientation, utilizing geometric and depth perception brain

Table 4

Significant intervention effects on subscales of POMS-SF measures (mean SD).

Measures

Relaxation

Calligraphy

Control

F

p

h

2

TA

Time 1

5.00 1.98

4.96 1.90

4.90 2.93

0.01

.987

.000

Time 2

4.04 1.25

4.08 1.64

4.79 2.27

1.53

.223

.039

Time 3

3.08 1.52

3.50 1.69

4.04 1.54

3.39

.039

.082

Time 4

3.19 1.13

3.19 1.61

4.48 1.99

4.61

.013

.108

DD

Time 1

5.69 1.78

5.75 2.21

5.24 2.66

0.41

.662

.011

Time 2

4.42 1.68

4.46 2.02

5.79 2.73

3.43

.038

.083

Time 3

4.04 1.54

3.79 1.91

5.76 2.78

6.66

.002

.149

Time 4

4.15 1.22

3.83 1.55

4.62 1.82

1.71

.188

.043

AH

Time 1

3.73 1.87

3.50 1.82

3.76 2.52

.098

.906

.003

Time 2

2.73 1.43

3.12 1.19

3.52 1.94

2.39

.099

.060

Time 3

2.35 1.33

2.25 1.15

3.59 1.94

6.47

.003

.147

Time 4

2.28 1.06

2.46 1.25

3.24 1.68

3.77

.028

.091

FI

Time 1

5.65 2.38

5.42 2.54

5.38 2.29

0.10

.903

.003

Time 2

5.00 1.36

4.38 1.74

5.62 1.88

3.62

.031

.087

Time 3

5.00 1.79

3.46 1.53

5.59 1.76

10.65

.000

.219

Time 4

4.69 1.35

3.96 1.37

4.90 1.68

2.82

.066

.069

TMD

Time 1

36.16 8.08

37.83 10.34

36.03 13.20

0.21

.809

.006

Time 2

31.60 6.67

32.71 6.96

36.83 9.92

3.15

.048

.078

Time 3

29.04 6.28

28.17 6.36

35.66 9.20

8.06

.001

.177

Time 4

28.00 4.72

28.21 5.76

32.59 8.94

3.89

.025

.094

Note: Each F tests the simple main effects of Group within each level combination of the other effects shown. These tests are based on the linearly

independent pairwise comparisons among the estimated marginal means.

Partial

h

2

: effect size estimate.

POMS-SF: Profile of Mood State-Short Form; TA: Tension-Anxiety; DD: Depression-Dejection; AH: Anger-Hostility; FI: Fatigue-Inertia; TMD: total mood

disturbance.

Time 1: measures at pre-treatment; Time 2: during treatment; Time 3: post-treatment; Time 4: 2-week follow-up.

X.-L. Yang et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 47 (2010) 550–559

556

functions. The writer must follow the pattern with

heightened alertness in the process of writing, at the

meantime, the writing act involves a cognitive facilitation

and emotional calmness process, and thus the concurrent

physiological change (

). Moreover, because

of the softness of the brush tip, the handwriting act

involves a 3-D motion, which generates a powerful source

of impact on the writer’s perceptual, cognitive, and

physiological changes during its practice (

). As

the intervention went on, the calligrapher gained more

control over their maneuvering of the brush, which in turn

induced deeper inner calmness and physiological slow-

down.

Progressive muscle relaxation is a relaxation technique

of stress management developed by American physician

Edmund Jacobson in 1934, which is focused on tensing and

releasing tensions in the 16 different muscle groups. PMR

combined with imagery training had established effects on

a variety of outcome measures in cancer patients.

found relaxation and guided imagery training

was effective in reducing treatment-related nausea and

physiological arousal (as measured by HR and BP) in

chemotherapy cancer patients.

found PMR training was associated with an improvement

on anxiety and quality of life among colorectal cancer

patients. The effectiveness of PMR and GI training on

physiological arousal parameters, as was found in the

present study, had also been established by existing

findings (

Lehrer, 1978; Sheu et al., 2003; Sung et al., 2000

and would not be discussed here. However in the current

study, relaxation was not associated with improvement of

nausea, which might due partly to the statistical floor

effect of nausea, for nausea was not a serious complaint in

patients receiving radiotherapy as their current treatment.

It was observed in the current study that relaxation had an

improvement effect on insomnia, which was consistent

with the existing findings about insomnia research (

). Relaxation training was also associated with

improved mood, including Tension-Anxiety, Depression-

Dejection, Anger-Hostility subscale and total mood dis-

turbance. The mood regulation effect found in the study

was confirmatory to the notion of

that muscular tension was usually followed as a byproduct

of anxiety, one could lower and reduce anxiety by

understanding and learning how to self relax those

muscular tension. Besides anxiety, it was found that

relaxation was also beneficial for moods of depression and

anger, as was documented in other applied researches

(

Leon-Pizarro et al., 2007; Nunes et al., 2007

4.2. Intervention feasibility

Patients in relaxation group reported that relaxation

training could make them feel calm, gain more control over

their aversive feelings, was an effective way to focus on

bodily sensation instead of a painful reality. Patients in

Calligraphy group reported that calligraphy provided a

path to calmness and relaxation of emotion, inspired an

inner motivation to pursue spiritual growth and beauty

appreciation, learned a discipline of being focused and

present in spirit, eliminated their fear of death and feeling

of worthlessness temperately. Feedback on suggestions to

improve the intervention procedure revealed: most

patients (76%) in relaxation group complained that the

program schedule was too rigid to follow, i.e., on fixed time

period of the day, 31% patients reported that practice

before bedtime was preferred; in calligraphy group, most

suggestions focused on the short length of practice, i.e.,

30 min per day, 66% patients reported that 45–60 min was

more desirable.

4.3. Study implication

Researches showed that art therapy intervention in

cancer patients could serve as a catalyst for healing, could

benefit the patients in their quality of life (

), and

demonstrated a significant symptom relieving effect

(

). Historically, Chinese calligraphy

handwriting was regarded as the most abstract and

sublime form of art in Chinese culture, many calligraphy

artists were well-known for their longevity. ‘‘Shufa’’

(calligraphy) is often thought to be most revealing of

one’s personality (examples of calligraphy art could go to

website:

http://www.chinapage.org/calligraphy.html

). To

the artist, calligraphy is a mental exercise that coordinates

the mind and the body to choose the best styling in

expressing the content of the passage. It is a most relaxing

yet highly disciplined exercise indeed for one’s physical

and spiritual well-being. Recent researches found that

calligraphy also have therapeutic values in clinical mental

health setting (

). The findings in the

current study provided further empirical evidence for the

therapeutic value of calligraphy as a form of art therapy. As

was advocated by the International Society of Calligraphy

Therapy (ISCT), calligraphy may play potentially important

role in the field of art therapy in both Chinese and non-

Chinese populations. Like Chinese handwriting, alphabetic

handwriting mostly involves the control and coordination

of the muscles of the fingers, hand and arm, subject to

visual guidance and monitoring (

). With the softness of a Chinese

brush, rather than ball pen, fountain pen, pencil, etc., the

calligraphic effect, which transforms the flat surface into

an imaginary 3-dimensional reality, could be produced.

4.4. Study limitations and future directions

One major limitation of the current study was that

although calligraphy has its roots in orient culture, there

are difficulties to generalize to other cultures, for people

who are unfamiliar with its use, may feel stressful to

conduct it. However, some pioneers in western and Arabic

culture had shown great interest in English-letter (Arabic)

calligraphy & handwriting recently (

). The second limitation was the small numbers

per group mean, so the analysis should be considered

exploratory. The third one was related to the intervention

procedure. Because we had limited knowledge regarding

whether different calligraphic character style and hand-

writing preference would be associated with different

clinical outcomes, it might be valuable to assess those

X.-L. Yang et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 47 (2010) 550–559

557

hypotheses in future researches. Finally, the high refusal

rate indicated that the applicability of psychotherapy in

Chinese cancer patients should be carefully considered

before the initiation of intervention programs. The reasons

of the high refusal rate in this study might be related to the

facts that the Chinese were more likely to present

emotions as physical symptoms (

), to

inhibit outward expression of negative emotions (

), and to refuse help for their psychological

problems (

), these characteristics of Chinese

cancer patients might compromise their perceived effec-

tiveness and acceptance of psychotherapy. Nevertheless,

the reasonable dropout rate suggested the programs were

easy to comply, could substantially benefit the patients

with high motives and resolution. We recommend future

researchers to test out the long-term effects of calligraphy

in terms of quality of life, spiritual well-being, and disease

progression. Furthermore, efforts also were needed to

disseminate efficacious components of calligraphy prac-

tice in future studies.

5. Conclusions

Similar to the effect of relaxation training, calligraphy

demonstrated a gradually build-up physiological slow-

down, and associated with heightened concentration and

improved mood disturbance. Calligraphy was inexpensive,

easy to practice, and involved an innate art appreciation

and cognitive facilitation process. Calligraphy handwriting

offered a promising approach to improved health in cancer

patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the staff in Cancer Centre,

Sun Yat-Sen University, China. Heartfelt thanks are given

to all the men and women who participated in the study,

whose enthusiasm continues to inspire us. Special thanks

are given to Dr Ruth McCorkle, Yale University School of

Nursing, who provided the valuable user’s manual for the

Symptom Distress Scale.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding: Not applicable.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for this study was approved

by the Review Board of the investigator’s institution.

References

Baldacchino, D.R., Buhagiar, A., 2003. Psychometric evaluation of the

Spiritual Coping Strategies scale in English, Maltese, back-translation

and bilingual versions. J. Adv. Nurs. 42 (6), 558–570.

Bernstein, D.A., Borkovec, T.D., 1973. Progressive Relaxation Training: A

Manual for the Helping Professions. Research Press, Champaign, Ill.

Cao, S.M., Guo, X., Li, N.W., Xiang, Y.Q., Hong, M.H., Min, H.Q., 2006.

Clinical analysis of 1,142 hospitalized Cantonese patients with naso-

pharyngeal carcinoma. Ai Zheng 25 (2), 204–208.

Cheung, Y.L., Molassiotis, A., Chang, A.M., 2003. The effect of progressive

muscle relaxation training on anxiety and quality of life after stoma

surgery in colorectal cancer patients. Psychooncology 12 (3), 254–

266.

Cheung, Y.L., Molassiotis, A., Chang, A.M., 2001. A pilot study on the effect

of progressive muscle relaxation training of patients after stoma

surgery. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 10 (2), 107–114.

Chi, S., Lin, W.J., 2003. The preliminary revision of Brief Profile of

Mood States (BPOMS)-Chinese Edition. Chin. J. Ment. Health 17

(11), 767–770.

Degner, L.F., Sloan, J.A., 1995. Symptom distress in newly diagnosed

ambulatory cancer patients and as a predictor of survival in lung

cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 10 (6), 423–431.

Frederickson, K., Jackson, B.S., Strauman, T., Strauman, J., 1991. Testing

hypotheses derived from the Roy Adaptation Model. Nurs. Sci. Q. 4 (4),

168–174.

Gaur, A., Keith, B., 2006a. Calligraphy, East Asian. In: Encyclopedia of

Language & Linguistics, Elsevier, Oxford, pp. 177–179.

Gaur, A., Keith, B., 2006b. Calligraphy, Islamic. In: Encyclopedia of Lan-

guage & Linguistics, Elsevier, Oxford, pp. 178–179.

Gaur, A., Keith, B., 2006c. Calligraphy, Western, Modern. In: Encyclopedia

of Language & Linguistics, Elsevier, Oxford, pp. 181–187.

Gotze, H., Geue, K., Buttstadt, M., Singer, S., Schwarz, R., 2009. Art therapy

for cancer patients in outpatient care. Psychological distress and

coping of the participants. Forsch. Komplementmed. 16 (1), 28–33.

Greene, F.L., 2002. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: updating the

strategies in cancer staging. Bull. Am. Coll. Surg. 87 (7), 13–15.

Guo, N.F., Kao, H.S.R., Liu, X., 2001. Calligraphy, hypertension and the

type-A personality. Ann. Behav. Med. 23 S2001, S159.

Huang, H.Y., Wilkie, D.J., Chapman, C.R., Ting, L.L., 2003. Pain trajectory of

Taiwanese with nasopharyngeal carcinoma over the course of radia-

tion therapy. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 25 (3), 247–255.

Huang, H.Y., Wilkie, D.J., Schubert, M.M., Ting, L.L., 2000. Symptom profile

of nasopharyngeal cancer patients during radiation therapy. Cancer

Pract. 8 (6), 274–281.

Jones, G., 2000. An art therapy group in palliative cancer care. Nurs. Times

96 (10), 42–43.

Kao, H.S., Ding-Guo, G., Danmin, M., Xufeng, L., 2004. Cognitive facilitation

associated with Chinese brush handwriting: the case of symmetric

and asymmetric Chinese characters. Percept. Mot. Skills 99 (3 Pt 2),

1269–1273.

Kao, H.S.R. (Ed.), 2000. Chinese Calligraphy Therapy. Hong Kong Uni-

versity Press, Hong Kong, pp. 3–42.

Kao, H.S.R., 2003. Chinese calligraphy handwriting for health and reha-

bilitation of the elderly. In: Second World Congress of the Interna-

tional Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. Prague, May

18–22, 2003 Book of Abstracts, p. 63.

Kao, H.S.R., 2006. Shufa: Chinese calligraphic handwriting (CCH) for

health and behavioral therapy. Int. J. Psychol. 41 (4), 282–286.

Kao, H.S.R., Chen, C.C., Chang, T.M., 1997. The effect of calligraphy practice

on character recognition reaction time among children with ADHD

disorder. In: Roth, R. (Ed.), Psychologists Facing the Challenge of a

Global Culture with Human Rights and Mental Health. Proceedings of

the 55th Annual Convention of the Council of Psychologists, Graz,

Austria, July 14–18, 1997, pp. 45–49.

Kao, H.S.R., Gao, D., Wang, M., 2000a. Brush handwriting treatment of

cognitive deficiencies in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neurobiol.

Aging 21 1s, 14.

Kao, H.S.R., Gao, D., Wang, M., Cheung, H.Y., Chiu, J., 2000b. Chinese

calligraphic handwriting: treatment of cognitive deficiencies of Alz-

heimer’s disease patients. Alzheimer’s Rep. 3, 281–287.

Kao, H.S.R., Guo, N.F., Liu, X., 2001. Effects of calligraphic practice on EEG

and blood pressure in hypertensive patients. Ann. Behav. Med. 23,

S085.

Kao, H.S.R., Hoosain, R., Van Galen, G.P. (Eds.), 1986a. Graphonomics:

Contemporary Research in Hand Writing. North-Holland, Amster-

dam, p. 403.

Kao, H.S.R., Mak, P.H., Lam, P.W., 1986b. Handwriting pressure: effects of

task complexity, control mode and orthographic differences. In: Kao,

H.S.R., van Galen, G.P., Hoosain, R. (Eds.), Graphonomics: Contempor-

ary Research in Handwriting. North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp. 47–66.

Karnofsky, D.A., Burchenal, J.H., 1949. The clinical evaluation of che-

motherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod, C.M. (Ed.), Evaluation

of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Columbia Univ Press.

Lai, Y.H., Chang, J.T., Keefe, F.J., Chiou, C.F., Chen, S.C., Feng, S.C., Dou, S.J.,

Liao, M.N., 2003. Symptom distress, catastrophic thinking, and hope

in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Cancer Nurs. 26 (6), 485–493.

Lehrer, P.M., 1978. Psychophysiological effects of progressive relaxation

in anxiety neurotic patients and of progressive relaxation and alpha

feedback in nonpatients. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 46 (3), 389–404.

Leon-Pizarro, C., Gich, I., Barthe, E., Rovirosa, A., Farrus, B., Casas, F., Verger,

E., Biete, A., Craven-Bartle, J., Sierra, J., Arcusa, A., 2007. A randomized

trial of the effect of training in relaxation and guided imagery tech-

niques in improving psychological and quality-of-life indices for

X.-L. Yang et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 47 (2010) 550–559

558

gynecologic and breast brachytherapy patients. Psychooncology 16

(11), 971–979.

Luebbert, K., Dahme, B., Hasenbring, M., 2001. The effectiveness of

relaxation training in reducing treatment-related symptoms and

improving emotional adjustment in acute non-surgical cancer treat-

ment: a meta-analytical review. Psychooncology 10 (6), 490–502.

Lyles, J.N., Burish, T.G., Krozely, M.G., Oldham, R.K., 1982. Efficacy of

relaxation training and guided imagery in reducing the aversiveness

of cancer chemotherapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 50 (4), 509–524.

McCallie, S.M., Blum, M.C., Hood, J.C., 2006. Progressive muscle relaxation.

J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 13 (3), 51–66.

McCorkle, R., Jepson, C., Malone, D., Lusk, E., Braitman, L., Buhler-Wilk-

erson, K., Daly, J., 1994. The impact of posthospital home care on

patients with cancer. Res. Nurs. Health 17 (4), 243–251.

McCorkle, R., Young, K., 1978. Development of a symptom distress scale.

Cancer Nurs. 1 (5), 373–378.

Monti, D.A., Peterson, C., Kunkel, E.J., Hauck, W.W., Pequignot, E., Rhodes,

L., Brainard, G.C., 2006. A randomized, controlled trial of mindfulness-

based art therapy (MBAT) for women with cancer. Psychooncology 15

(5), 363–373.

Morin, C.M., Hauri, P.J., Espie, C.A., Spielman, A.J., Buysse, D.J., Bootzin, R.R.,

1999. Nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia. An Amer-

ican Academy of Sleep Medicine review. Sleep 22 (8), 1134–1156.

Mumford, D.B., 1995. Cultural issues in assessment and treatment. Curr.

Opin. Psychiatry 8, 134–137.

Nunes, D.F., Rodriguez, A.L., da Silva Hoffmann, F., Luz, C., Braga Filho, A.P.,

Muller, M.C., Bauer, M.E., 2007. Relaxation and guided imagery pro-

gram in patients with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy is not

associated with neuroimmunomodulatory effects. J. Psychosom. Res.

63 (6), 647–655.

Pan, J.J., Zhang, S.W., Chen, C.B., Xiao, S.W., Sun, Y., Liu, C.Q., Su, X., Li, D.M.,

Xu, G., Xu, B., Lu, Y.Y., 2009. Effect of recombinant adenovirus-p53

combined with radiotherapy on long-term prognosis of advanced

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 27 (5), 799–804.

Ragsdale, D., Morrow, J.R., 1990. Quality of life as a function of HIV

classification. Nurs. Res. 39 (6), 355–359.

Sheu, S., Irvin, B.L., Lin, H.S., Mar, C.L., 2003. Effects of progressive muscle

relaxation on blood pressure and psychosocial status for clients with

essential hypertension in Taiwan. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 17 (1), 41–47.

Su, R.V., Chen, C.C., 1979. Diagnostic and therapeutic implications of

Chinese calligraphy in psychiatric occupational therapy (author’s

transl). Taiwan Yi Xue Hui Za Zhi 78 (4), 419–432.

Sung, B.H., Roussanov, O., Nagubandi, M., Golden, L., 2000. Effectiveness

of various relaxation techniques in lowering blood pressure asso-

ciated with mental stress. Am. J. Hypertension 13 (4, Suppl. 1),

S185–S1185.

Svensk, A.C., Oster, I., Thyme, K.E., Magnusson, E., Sjodin, M., Eisemann,

M., Astrom, S., Lindh, J., 2009. Art therapy improves experienced

quality of life among women undergoing treatment for breast

cancer: a randomized controlled study. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.)

18 (1), 69–77.

Van Galen, G.P., Teulings, H.L., 1983. The independent monitoring of form

and scale factors in handwriting. Acta Psychologica 54, 9–22.

Visser, A., Op’t Hoog, M., 2008. Education of creative art therapy to cancer

patients: evaluation and effects. J. Cancer Educ. 23 (2), 80–84.

Walker, L.G., Walker, M.B., Ogston, K., Heys, S.D., Ah-See, A.K., Miller,

I.D., Hutcheon, A.W., Sarkar, T.K., Eremin, O., 1999. Psychological,

clinical and pathological effects of relaxation training and guided

imagery during primary chemotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 80 (1–2), 262–

268.

Wang, J.P., Chen, H.Y., Su, W.L., 2004. Reliability and validity of Profile of

Mood State-Short Form in Chinese patients. Chin. J. Ment. Health 18

(6), 404–407.

Wen, S.L., Zhang, J.B., Ye, M.Z., Han, Z.L., Tao, J., 2000. Mental health status

of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 8

(1), 52–54.

Ying, Y.W., Lee, P.A., Tsai, J.L., Yeh, Y.Y., Huang, J.S., 2000. The conception of

depression in Chinese American college students: cultural diversity

and ethnic minority. Psychology 6, 183–195.

Ying, Y., 1997. Psychotherapy for East Asian Americans with major

depression. In: Lee, E. (Ed.), Working with Asian Americans: A Guide

for Clinicians. NY7 Guilford Press, pp. 252–264.

Yoo, H.J., Ahn, S.H., Kim, S.B., Kim, W.K., Han, O.S., 2005. Efficacy of

progressive muscle relaxation training and guided imagery in redu-

cing chemotherapy side effects in patients with breast cancer and in

improving their quality of life. Support. Care Cancer 13 (10), 826–833.

Young-Mason, J., 2003. Alhabeeb’s calligraphy ‘‘Peace and beauty’’: a

bridge to understanding. Clin. Nurse Spec. 17 (2), 112–113.

X.-L. Yang et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 47 (2010) 550–559

559

Document Outline

- The effects of Chinese calligraphy handwriting and relaxation training in Chinese Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma patients: A randomized controlled trial

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

A systematic review and meta analysis of the effect of an ankle foot orthosis on gait biomechanics a

Glińska, Sława i inni The effect of EDTA and EDDS on lead uptake and localization in hydroponically

the effect of interorganizational trust on make or cooperate decisions deisentangling opportunism de

Ebsco Cabbil The Effects of Social Context and Expressive Writing on Pain Related Catastrophizing

Microwave drying characteristics of potato and the effect of different microwave powers on the dried

The Effects of Performance Monitoring on Emotional Labor and Well Being in Call Centers

the effect of sowing date and growth stage on the essential oil composition of three types of parsle

Junco, Merson The Effect of Gender, Ethnicity, and Income on College Students’ Use of Communication

On Computer Viral Infection and the Effect of Immunization

The Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Markers of Blood Lipids, and Blood Pressure in Patients

the effect of water deficit stress on the growth yield and composition of essential oils of parsley

Kowalczyk Pachel, Danuta i inni The Effects of Cocaine on Different Redox Forms of Cysteine and Hom

The effects of handwriting experience on functional brain

The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells implication for inflammation, heart disease, and

Sailing Yacht Performance The Effects of Heel Angle and Leeway Angle on Resistance

76 1075 1088 The Effect of a Nitride Layer on the Texturability of Steels for Plastic Moulds

Curseu, Schruijer The Effects of Framing on Inter group Negotiation

Evidence for the formation of anhydrous zinc acetate and acetic

więcej podobnych podstron