Pathological dissociation and

neuropsychological functioning in borderline

personality disorder

Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is charac-

terized by disturbed relational abilities, affective

dysregulation, lack of behavior control and dis-

turbed

cognition

(1–3).

Disturbed

cognition

includes dissociative symptoms, non-delusional

suspiciousness

and

quasi-psychotic

symptoms.

Although neurocognitive impairment has been

suggested to act as a moderator in the develop-

ment of the disorder (4), only a few studies have,

with a variety of results, been devoted to the

Haaland VØ, Landrø NI. Pathological dissociation and

neuropsychological functioning in borderline personality disorder.

Objective: Transient, stress-related severe dissociative symptoms or

paranoid ideation is one of the criteria defining the borderline

personality disorder (BPD). Examinations of the neuropsychological

correlates of BPD reveal various findings. The purpose of this study

was to investigate the association between dissociation and

neuropsychological functioning in patients with BPD.

Method: The performance on an extensive neuropsychological

battery of patients with BPD with (n = 10) and without (n = 20)

pathological dissociation was compared with that of healthy controls

(n = 30).

Results: Patients with pathological dissociation were found to have

reduced functioning on every neuropsychological domain when

compared with healthy controls. Patients without pathological

dissociation were found to have reduced executive functioning, but no

other differences were found.

Conclusion: Pathological dissociation is a clinical variable that

differentiates patients with BPD with regard to cognitive functioning.

V. Ø. Haaland

1,2

, N. I. Landrø

2

1

Department of Psychiatry, Sørlandet Hospital HF,

Kristiansand, Norway and

2

Center for the Study of

Human Cognition, Department of Psychology, University

of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Key words: personality disorders; dissociation;

cognition; cognitive science; neuropsychology

Vegard Øksendal Haaland, Sørlandet sykehus HF,

Psykiatrisk avdeling, Serviceboks 416, N-4604

Kristiansand, Norway.

E-mail: vegard.oksendal.haaland@sshf.no

Accepted for publication November 7, 2008

Significant outcomes

•

This study reports deficits in executive functioning, working memory and long-term verbal memory

performance in a subgroup of patients with BPD and pathological dissociation compared with that

in patients with BPD without pathological dissociation.

•

Patients with BPD who also show pathological dissociation seem to represent a more severely

disturbed subgroup of patients with BPD.

•

Pathological dissociation is a clinically important and relatively easily assessable psychopathological

variable.

Limitations

•

The sample is relatively small, a factor that in particular influences the size of the subgroup of

patients demonstrating pathological dissociation.

•

Dissociation is investigated both as a trait and as a categorical variable. The effect of dissociative

states per se is not studied.

Acta Psychiatr Scand 2009: 119: 383–392

All rights reserved

DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01323.x

Copyright

2008 The Authors

Journal Compilation

2008 Blackwell Munksgaard

ACTA PSYCHIATRICA

SCANDINAVICA

383

neuropsychological functioning of persons with

BPD. A recent review of neuropsychological cor-

relates of BPD suggests the existence of several

neuropsychological deficits (5). These deficits are

particularly pertinent to executive functions. Still,

more research would be needed to examine vari-

able results with regard to other neuropsycholog-

ical functions.

Dissociation can be defined as a disruption in the

usually integrated functions of consciousness,

memory, identity and perception (3). The occur-

rence of Ôtransient, stress-related severe dissociative

symptoms or paranoid ideationÕ is a defining

criterion of BPD that was added to the current

version of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

(DSM) (3). This criterion, which occurs in

around 75% of patients with BPD, shows excellent

specificity (1). According to the DSM-IV, disso-

ciative symptoms in patients with BPD are in

particular associated with situations with high

levels of stress (3), a relation that has been

demonstrated experimentally (6, 7).

Dissociative experiences also occur in the

general population (8) and measures like the

Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES) assess dis-

sociation as a continuous variable or a trait (9).

However, some studies indicate that dissociative

experiences are not uniformly distributed in

clinical groups the way a dimensional model of

dissociation would imply. Differences in mean

dissociative scores between different diagnostic

groups seem to depend on differences in the

frequency of high-dissociative individuals (10). A

taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences

revealed that two types of dissociation exists

(11). Non-pathological dissociation occurs along

a continuum and is considered a manifestation

of a dimensional construct or a dissociative

trait. Pathological dissociation is considered a

manifestation of a latent class variable or a

taxon.

Recent research has increasingly tended to

focus on associations between cognition and

dissociation. Non-pathological dissociation has

in this context been approached as a fundamen-

tal information-processing mechanism (12). Few

studies have focused on cognition and dissocia-

tion in clinical populations except for dissociative

disorders and none of those have focused on

pathological dissociation. In a sample of forensic

inpatients, a negative correlation was found

between executive test performance and dissocia-

tive symptoms (13). In patients with BPD,

dissociative

symptoms

have

been

related

to

difficulties in recalling specific autobiographic

memories (14).

Aims of the study

We sought to investigate associations between

dissociation and neuropsychological functioning

in patients with BPD. Our focus was on correla-

tions between total dissociative experiences and

neuropsychological performance, as well as on

comparison of the neuropsychological functioning

of patients with BPD with and without patholog-

ical dissociation with the performance of healthy

controls.

Material and methods

Participants with borderline personality disorder

This study was approved by the Regional Commit-

tee for Medical Research Ethics, and written

informed consent was obtained after the partici-

pants had been provided with a complete description

of the study. The sample consisted of 35 patients,

recruited through in- and outpatient settings from

different units of the Clinic for Mental Health –

Psychiatry and Dependency treatment at Sørlandet

Hospital HF – a general hospital in southern

Norway serving a population of about 265 000.

We aimed for a sample of patients with BPD who

may be considered representative of subjects in an

inpatient or outpatient setting. Knowing that com-

orbidity for axis I and axis II disorders is frequent in

patients with BPD (15, 16), we sought to limit the

exclusion criteria so as to include patients with the

most common comorbid disorders such as depres-

sion and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Patients had to be between 18 and 40 years of age

and were required to fulfill the DSM-IV (3) criteria

for BPD. Exclusion criteria were a history of head

trauma or epilepsy, significant neurological findings,

mental retardation and ongoing substance abuse. A

total of 47 patients were recruited for evaluation; of

these, 12 did not fulfill the criteria and five had not

completed the clinical measure for dissociative

experiences (DES). These were excluded from the

study, leaving the final clinical sample with a total of

30 patients. Twenty-six patients were diagnosed

with lifetime affective disorder – 10 in remission, 16

with PTSD, 11 with an anxiety disorder other than

PTSD, 9 with another personality disorder and 6

with substance abuse. All but six patients were

taking psychotropic medications of which the most

common were SSRIs and atypical antipsychotics.

Healthy controls

Thirty-one non-clinical comparison subjects were

recruited among non-healthcare employees at the

Haaland and Landrø

384

hospital, students having practicum at the hospital,

through newspaper advertisement or among friends

and relatives of the staff of the hospital. In addition

to the exclusion criteria that applied to the patient

group, selection criteria for the healthy controls

were no history of availing psychiatric services, no

history of psychotropic medication and no history

which indicated psychiatric disorders.

Clinical and diagnostic assessments

Diagnoses were established using the structured

clinical interviews for DSM-IV SCID-I (17) and

SCID-II (18) conducted by one of the authors

(V.Ø.H.). Twenty of the interviews with potentially

participating patients were videotaped. The rating

was repeated by an external experienced clinical

psychologist who was unaware as to whether the

patients were included in the study or not. The

inter-rater agreement for the ratings of the nine

criteria for BPD was found to be good (average

CohenÕs j = 0.640). Depression was measured

with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (19),

global functioning by the Global Assessment of

Functioning Scale (GAF) (3), whereas dissociative

symptoms were measured using the Norwegian

version of the DES (9) a 28-item rating scale where

each item is scored from 0 to 100. Individuals with

pathological dissociation can be identified using

eight items from the DES, the DES-T (11).

Neuropsychological assessment

Every participant underwent an extensive battery of

intellectual and neuropsychological tests, where

most cognitive domains were covered with several

tests to obtain stable and robust measures. Domains

covered included attention, working memory, exec-

utive functions, verbal and non-verbal long-term

memory, and general cognitive abilities. The neuro-

psychological battery was administered by a test

technician or a clinical psychologist trained in

standardized assessment. Participants were tested

individually, and the total time required for testing

was about 4 h divided into two sessions. The tasks

were given in the same order, and testing was

performed at the clinic in the same location for all

participants. The neuropsychological test battery

with definitions of the variables used grouped by

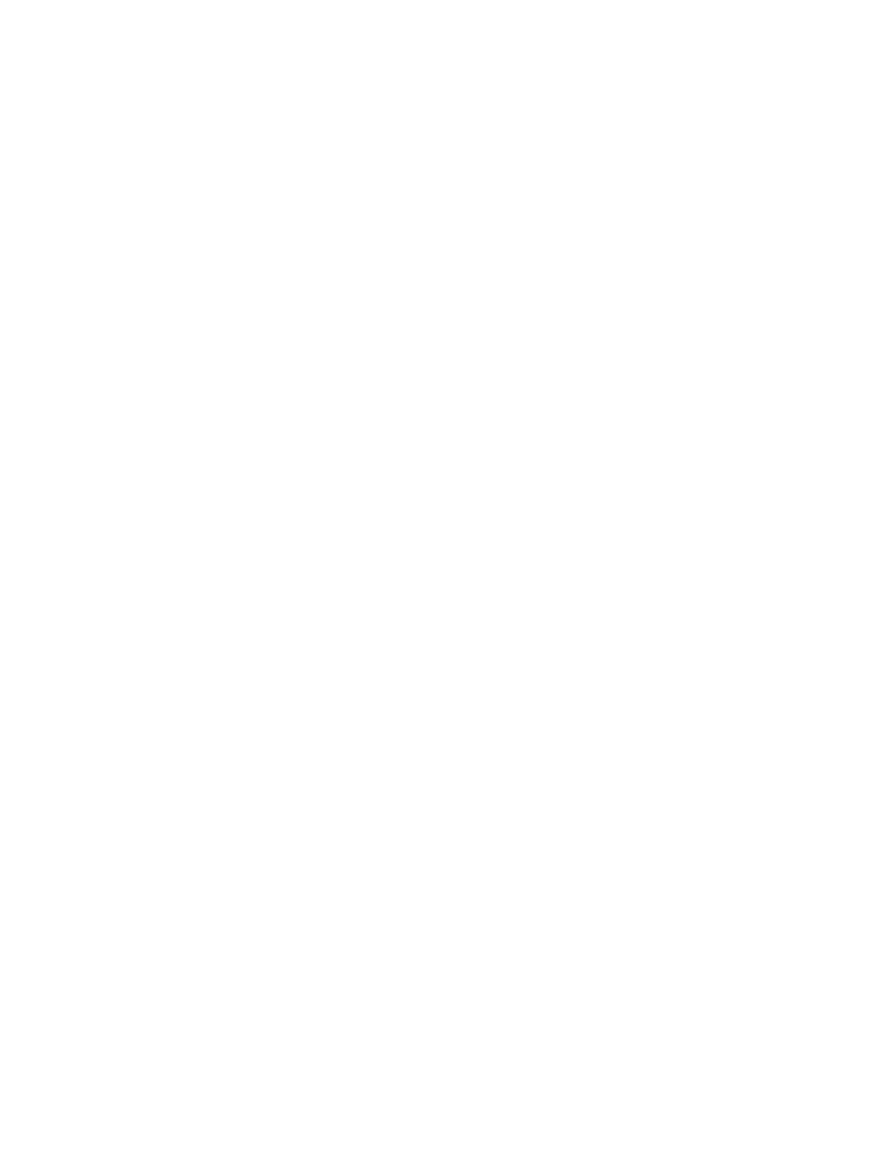

cognitive domain is presented in Table 1.

Measures of attention

The Digit Symbol-Coding subtest from WAIS-III

(20) and the Conners Continuous Performance

Test II (CPT-II) (21) were used as measures of

attention. In the Digit Symbol-Coding subtest,

symbols must be matched and drawn as fast as

possible under the corresponding digit. The CPT-II

asks participants to monitor a random series of

single letters, presented continuously at different

rates on a monitor. The space bar has to be pressed

when a letter is presented except for the letter ÔxÕ.

Measures of working memory

The Digit Span subtest from WAIS-III (20), a

variant of the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test

Table 1. Test battery used to assess neuropsychological and intellectual perfor-

mance grouped by cognitive domain

Neuropsychological domain and constituent items

Variables

Attention

Digit Symbol-Coding (WAIS-III) (20)

Total raw score

Conner Continuous

Performance Test (21)

Omissions; hit reaction time –

by block

Working memory

Digit Span (WAIS-III) (20)

Total raw score

Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (22)

Number of correct responses

Letter Number Span (23)

Number of correct responses

n-Back (24)

Number of correct responses

in each of the 1–3 back

conditions

Executive functions

Stroop Color-Word Test (25)

Stroop interference score:

time to read incongruent

list minus time to read

congruent list

Tower of London (TOL-4) (26)

0–3 points dependent of

number of trials to solve

each problem. Total score

was the sum of points over

all 10 problems

Controlled Oral Word Association (27)

Semantic and phonetic fluency

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (28)

Percent preservative errors

Trail Making Test (29)

Flexibility index [trail B (time)

minus trail A (time)]

Iowa Gambling Task (30)

Number of choices from the

advantageous decks minus

the number of choices from

the disadvantageous decks

Verbal long-term memory

Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (32)

Learning score: sum for trials

1–3; immediate free recall;

delayed free recall,

after 20 min

Visual long-term memory

Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure (29)

Immediate recall; delayed

recall, after 20 min; item

recognition with

50% distractors

Kimura Recurring Recognition

Figures Test (33)

Number of correct responses

General cognitive ability

Picture Arrangement (WAIS-III) (20)

Total raw score

Block Design (WAIS-III) (20)

Total raw score

Picture Completion (WAIS-III) (20)

Total raw score

Vocabulary (WAIS-III) (20)

Total raw score

Similarities (WAIS-III) (20)

Total raw score

WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3 edition.

Dissociation and cognition in BPD

385

(PASAT) (22), the Letter Number Span (LNS) (23)

and the n-back task (24) were used as measures of

working memory. In the Digit Span subtest, series

of orally presented numbers must be repeated

verbatim and in reverse. In PASAT (22), 60 CD-

recorded digits are presented at a rate of 3.0 s.

Participants are required to add each number to

the one that immediately precedes it, and articulate

the new number promptly. In the LNS (23), orally

presented sequences of letters and numbers must be

sorted and presented by listing numbers in ascend-

ing order and letters in alphabetical order. In the

n

-back task (24), the numbers 2, 4, 6 or 8 are

displayed randomly on a computer screen. The

task is to respond on the keyboard with the

number presented n positions back in the sequence.

In our study, four conditions were used, 0-, 1-, 2-

and 3-back. Participants completed three trials in

each condition, with 14 stimuli per trial.

Measures of executive functions

The Stroop Color-Word Test (25), a version of the

Tower of London (TOL-4) (26), the Controlled Oral

Word Association Test (COWA) (27), the Wiscon-

sin Card Sorting Test (WCST) (28), the Trail

Making Tests (TMT) (29) and the Iowa Gambling

Task (IGT) were used (30) as measures of executive

functions. The Stroop Color-Word Test (25) con-

sists of three white cards, each containing a 6

· 8

matrix of stimulus. The critical part of the test

involves inhibition of response to color words

printed in incongruently colored inks. The TOL-4

(26) is a problem-solving task involving forward

planning to match arrangements of colored balls.

The COWA (27) is a measure of phonetic and

semantic verbal fluency requiring the ability to

generate words beginning with the letters F, A and S

and words in the categories of animals and cloths,

each in 1 min. In the WCST (28) the principles

according to which a deck of cards must be sorted

has to be discovered. In TMT-A (29), lines have to

be drawn sequentially connecting 25 encircled

numbers distributed on a sheet of paper. In TMT-

B, the participants must alternate between numbers

and letters. A computerized version of IGT was used

(30). IGT is a decision-making task under condi-

tions of limited knowledge about reward and

penalty, involving choices from advantageous and

disadvantageous decks of cards.

Measures of verbal long-term memory

The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised

(HVLT-R) (31, 32) was used as a measure of verbal

long-term memory. This is a classical word list

learning task with a 12-item list, and three succes-

sive learning trials.

Measures of visual long-term memory

The Kimura Recurring Recognition Figures Test

(33) and the Rey Complex Figure Test (RCFT) (29)

were used as measures of visual long-term memory.

The Kimura (33) is a continuous recognition task

that involves recognizing 20 cards containing previ-

ously learned drawn figures among 100 cards which

are presented one by one. The RCFT (29) was used

along with a recognition task. It involves copying

and recalling a complex geometric figure. The

scoring of the figures followed the 36-point scoring

system described by Lezak (29).

Measures of general cognitive ability

The Vocabulary, Block Design, Picture Completion,

Picture Arrangement and the Similarities subtests

from WAIS-III (20) were used as measures of

general cognitive ability. In the subtest Picture

Arrangement, cartoon-type pictures must be rear-

ranged to make a logical story sequence. In Block

Design, a set of blocks has to be arranged to replicate

various patterns. In Picture Completion, the most

important part missing in each of a set of color

pictures has to be identified. The Vocabulary subtest

asks participants to define orally and visually

presented words, whereas in the Similarities subtest

they are asked to explain the similarity between pairs

of words. The original scoring procedure was used.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was completed by means of spss 16.0

(SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The DES-T (11)

score was computed and the clinical sample was

divided into a group belonging to the pathological

dissociation taxon and a group not belonging to

the pathological dissociation taxon. Pathological

taxon membership was determined by calculating

Bayesian posterior taxon membership probabilities

according to procedures described by Waller and

Ross (34). Analyses of variance (anova) and chi-

squared tests were used to compare the three

groups regarding demographic variables whereas

t

-tests and chi-squared tests were used to compare

the two clinical groups regarding clinical variables.

For the purpose of analysis, all neuropsycholog-

ical scores were transformed into standardized

scores based on the mean values and standard

deviations of the whole clinical sample. The stan-

dardized measures were grouped into five different

cognitive domains and summary scores were

Haaland and Landrø

386

computed. Prorated IQ was computed using the

sum of the scaled scores of those five subtests

multiplied with 11

⁄ 5 as raw score. Table 1 presents

the constituent test scores in each cognitive

domain. The correlations between the neuropsy-

chological domains and the DES and DES-T

scores in the clinical group were computed using

PearsonÕs r. The pathological taxon group and the

non-pathological taxon group were compared with

healthy controls with respect to neuropsychologi-

cal performance by the use of a multivariate

analysis of variance (manova) followed up with

anova

s. Where significant effects were demon-

strated, post hoc pairwise comparisons were con-

ducted using Bonferroni adjustments in order to

correct for multiple comparisons. Effect sizes were

also computed for those differences.

Results

Taxon membership

The computation of Bayesian posterior taxon

membership probabilities resulted in 10 taxon

members with pathological dissociation and 20

non-members among the patients with BPD. One

healthy control participant was also identified as a

taxon member and was excluded from further

analysis. The probability for every participant in

the remaining healthy control group was 0.04%

(the lowest possible value) indicating no scores

above cut-off for any of the DES-T items for any of

the participants. For the non-member patient

group, the average membership probability was

1.9% (range 0.04–7.0%), and for the member

group 89% (range 72.5–100%), indicating no

uncertainty with respect to membership status.

Demographic characteristics

Table 2 displays the mean values and standard

deviations in demographic and clinical variables

for the three groups including results of statistical

comparisons. The groups were statistically similar

in terms of all demographic variables except for

participantsÕ educational level. Post hoc tests

(Scheffe´) indicated that both the taxon member

group (P = 0.004) and the non-taxon member

Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics, and neuropsychological test performance of patients with borderline personality disorder with and without pathological

dissociation, and healthy controls

BPD Non-DES-T

(n = 20)

BPD DES-T

(n = 10)

Healthy controls

(n = 30)

Analysis

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

F

d.f.

P

Age (years)

25.5

5.6

23.7

4.8

25.9

6.4

0.52

2

0.597

Education (years)

12.9

2.6

12.0

1.6

14.8

2.1

8.18

2

0.001

MotherÕs education (years)

11.3

3.0

10.8

2.9

13.0

3.1

2.55

2

0.088

FatherÕs education (years)

12.9

4.5

12.2

3.5

13.8

3.0

0.77

2

0.471

t*

d.f.

P

Hamilton DRS

11.4

6.0

14.4

4.9

1.8

2.6

1.32

28

0.197

GAF

42.1

5.2

38.8

7.7

88.5

5.5

1.37

28

0.181

DES – total score

14.9

9.0

38.5

15.5

2.2

1.9

5.28

28

<0.001

DES – pathological

dissociation score

10.5

7.2

36.3

19.8

0.5

0.9

5.24

28

<0.001

n

%

n

%

n

%

v

2

d.f.

P

Gender

Male

4

20.0

0

0.0

4

13.3

Female

16

80.0

10

100.0

26

86.6

2.308

2

0.315

Handedness

Right

18

90.0

10

100.0

27

90.0

Left

2

10.0

0

0.0

3

10.0

1.550

2

0.461

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

F

d.f.

P

Neuropsychological performance

Attention

0.25

0.41

)0.44

1.29

0.59

0.59

7.27

2, 51

0.002

Working memory

0.27

0.64

)0.33

0.84

0.67

0.54

10.06

2, 51

<0.001

Executive functions

0.26

0.40

)0.40

0.69

0.68

0.32

25.19

2, 51

<0.001

Verbal long-term memory

0.24

0.67

)0.46

1.19

0.44

0.55

7.83

2, 51

0.001

Visual long-term memory

0.25

0.61

)0.10

0.61

0.60

0.53

5.67

2, 51

0.006

Prorated IQ

100.9

12.3

87.2

12.9

113.7

11.4

20.90

2, 51

<0.001

DRS, Depression Rating Scale; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; DES, Dissociative Experiences Scale; BPD, Borderline Personality Disorder; DES-T, Dissociative

Experiences Scale pathological dissociation Taxon member.

*Comparisons between the two clinical groups.

Dissociation and cognition in BPD

387

group (P = 0.016) had a significantly lower edu-

cational level than the healthy control group. No

differences were found between the two clinical

groups (P = 0.543).

Clinical characteristics

Between the two clinical groups, the analysis

showed no differences with respect to scores on

the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale or on the

GAF scale (Table 2). The analysis revealed signif-

icant differences between the two groups on

dissociative experiences both on the DES total

score and on the DES-T score. There were no

differences between the two clinical groups in the

frequencies of affective disorders (v

2

= 0.144;

d.f. = 1;

P

= 0.704)

or

PTSD

(v

2

= 0.268;

d.f. = 1; P = 0.605).

Overall analysis of neuropsychological performance

When comparing the two clinical groups and the

healthy control group with manova (Wilks lambda),

we found an overall group difference in neuro-

psychological test performance [F(12,92) = 4.36,

P

< 0.001]. anova revealed significant differences

between the three groups in all neuropsychological

domains (Table 2).

Neuropsychological performance of patients with BPD with

pathological dissociation

Post hoc

pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni

adjustments

revealed

significant

differences

between patients with BPD with pathological

dissociation and the healthy control group on

every cognitive domain: attention (P = 0.001),

working memory (P < 0.001), executive function-

ing (P < 0.001), verbal long-term memory (P =

0.002), non-verbal long-term memory (P = 0.004)

and general cognitive functioning (P < 0.001).

Bias-corrected (HedgesÕ gˆ) effect sizes with 95%

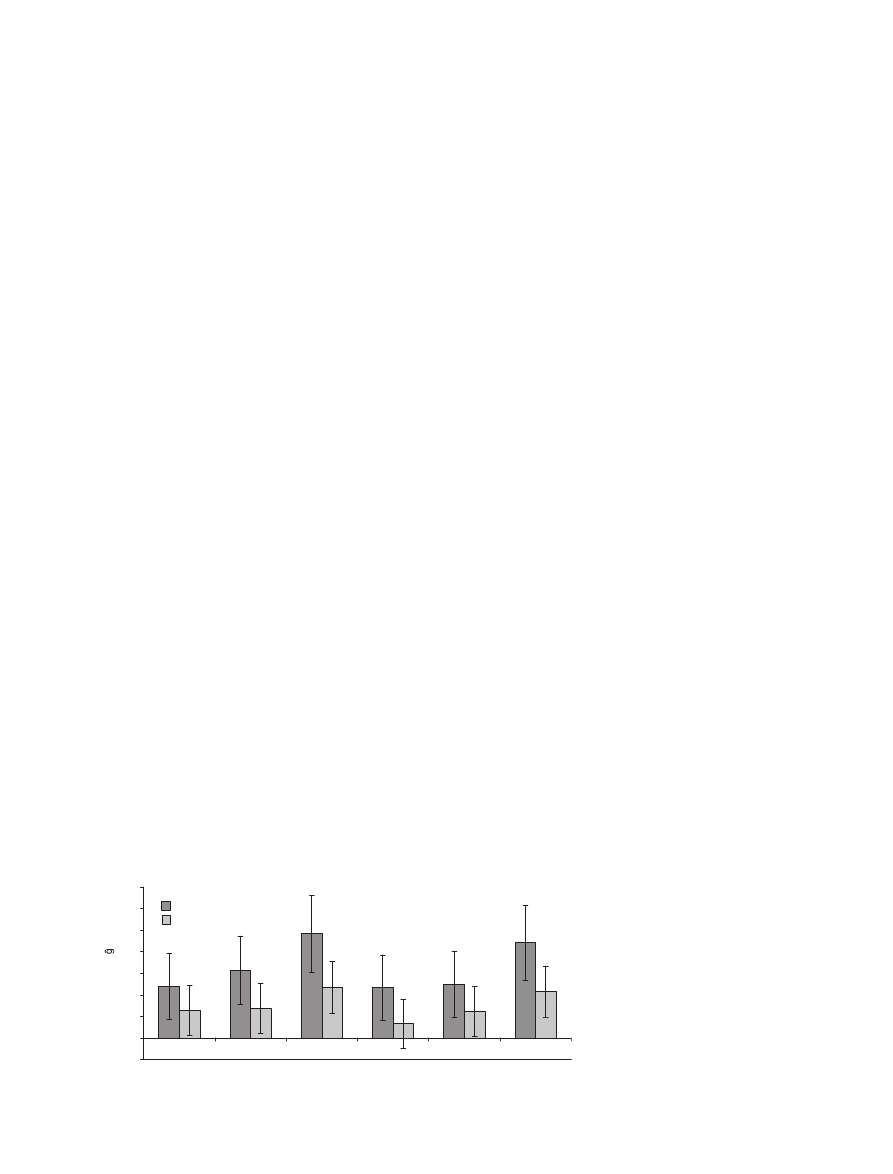

confidence intervals are presented in Fig. 1.

Neuropsychological performance of patients with BPD without

pathological dissociation

We found a significant difference between the

healthy controls and patients with BPD without

pathological dissociation on measures of executive

functioning (P = 0.004), but not on measures of

the other domains: attention (P = 0.388), working

memory (P = 0.307), verbal long-term memory

(P = 1.000),

non-verbal

long-term

memory

(P = 0.927) or general cognitive functioning

(P = 0.057). Bias-corrected (HedgesÕ gˆ) effect

sizes with 95% confidence intervals are presented

in Fig. 1.

Differences in neuropsychological performance between the

clinical groups

Patients with BPD without pathological dissocia-

tion showed better performance than patients with

BPD with pathological dissociation on measures of

working memory (P = 0.027), executive function-

ing (P = 0.002), verbal long-term memory (P =

0.002)

and

general

cognitive

functioning

(P = 0.001). No differences were found between

the two groups on measures of attention (P = 0.097)

or non-verbal long-term memory (P = 0.092).

Correlations between neuropsychological performance and

dissociation

In the combined clinical samples, there were

significant negative correlations between DES

total score and attention (r =

)0.56, P = 0.001),

and

between

DES-T

score

and

attention

(r =

)0.53, P = 0.003) and verbal long-term

memory (r =

)0.41, P = 0.025). Correlations

between the dissociation score and the other

–0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

Attention Working

memory

Executive

functions

Verbal LTM

Visual LTM

IQ

Effect sizes, Hedges (adjusted)

BPD/DES-T

BPD/NON-DES-T

Fig. 1.

Effect sizes (with error bars

indicating 95% CIs) of the differences

between the groups of patients with

BPD with and without pathological

dissociation and the healthy control

group on every cognitive domain.

Haaland and Landrø

388

neuropsychological domains and between the dif-

ferent domains are presented in Table 3.

Discussion

The association between pathological dissociation and

neuropsychological performance

To our knowledge, this is the first study that

explores associations between pathological disso-

ciation as a categorical variable and neuropsycho-

logical performance in patients with BPD. Patients

with BPD and pathological dissociation were

found to have reduced executive functioning,

working memory and long-term verbal memory

performance when compared with patients with

BPD without pathological dissociation. With

regard to the neuropsychological domains of

attention and long-term non-verbal memory, no

differences were found between the two groups.

When compared with healthy controls, patients

with BPD with pathological dissociation showed

reduced performance on every cognitive domain,

whereas patients with BPD without pathological

dissociation showed only reduced executive func-

tioning. The only neuropsychological domain that

seems to be consistently impaired in patients with

BPD, regardless of pathological dissociation, is the

executive one; a finding that concurs with previous

research (5).

This study contributes to the understanding of

cognitive functioning of patients with BPD. Path-

ological dissociation might be a clinical variable

that differentiates patients with BPD with regard to

cognitive functioning. These results elaborate the

findings from earlier examinations of executive

functioning,

working

memory

and

long-term

verbal memory in BPD (35–44). Different propor-

tions of pathological dissociative patients in differ-

ent study samples may be one factor that accounts

for the variability of the findings. This clinical

characteristic may also plausibly account for the

fMRI findings which connect specific frontolimbic

neural substrates to behavioral dyscontrol in

patients with BPD (45).

The two groups also differed with respect to

general intellectual abilities. The score of the

group with pathological dissociation was more

than 1 SD lower than the group without

pathological dissociation. This is a crucial finding

that, along with the results regarding the other

cognitive domains, allow for several hypotheses.

First, one could argue that reduced cognitive

abilities enhance the probability of pathological

dissociation. Second, one could hypothesize that

there is a common factor to reduced cognitive

abilities and pathological dissociation; it could be

a question of traumatic experiences that, at a

certain stage, would effect neurobiological devel-

opment. Third, it is, of course, possible that the

pathological dissociative phenomena per se cause

reduced test performance, i.e. pathological disso-

ciation during test uptake conflicts with the tasks

solved. Nonetheless, pathological dissociation and

reduced working memory, executive functions,

long-term verbal memory performance and IQ

seem to be co-occurring in patients with BPD.

Correlations between non-pathological dissociation and

neuropsychological performance

When using a dimensional model of dissociation,

we found a significant negative correlation between

the total DES score and performance in the

attention domain, but not between DES score

and

performance

on

the

neuropsychological

domains of working memory, executive functions,

long-term verbal memory, long-term non-verbal

memory or IQ. When treating the DES-T as a

dimensional variable, it was found to be signifi-

cantly negatively correlated with attention as well

as with verbal long-term memory, but not with

performance on the other domains. These findings

are crucial for two reasons:

First, we found different associations between

dissociation and neuropsychological performance

when applying a dimensional model compared

with the results when applying a categorical model.

Dimensional dissociation was negatively related to

attention and verbal memory, while categorical

(pathological) dissociation was negatively related

to working memory, executive functions and verbal

memory. When taking the DES total score pri-

marily as a measure of non-pathological dissocia-

tion, this implies

that non-pathological and

pathological dissociation are related to different

Table 3. Correlations between performance on neuropsychological domains and

measures of dissociation in patients with borderline personality disorder

Working

memory

Executive

functions

Verbal

LTM

Visual

LTM

Prorated

IQ

DES

DES-T

Attention

0.41*

0.61**

0.60** 0.37

0.47**

)0.56** )0.53**

Working

memory

0.75**

0.48** 0.46**

0.74**

)0.35

)0.20

Executive

functions

0.47** 0.50**

0.65**

)0.38

)0.22

Verbal LTM

0.53**

0.58**

)0.34

)0.41*

Visual LTM

0.61**

)0.25

)0.24

Prorated IQ

)0.30

)0.25

DES

0.89**

LTM, Long-term memory, DES, Dissociative Experiences Scale – total score; DES-T

Dissociative Experiences Scale pathological dissociation score. Correlation is sig-

nificant at the *0.05 (two tailed) and **0.01 (two tailed) levels.

Dissociation and cognition in BPD

389

cognitive functions. When using the DES-T results

dimensionally, we found approximately the same

results as when we used the DES, indicating that

research based on DES-T dimensionally as a

measure of pathological dissociation may produce

different results compared with that of studies

treating pathological dissociation as a latent class

variable.

Second, these findings allow for interesting

comparisons with studies investigating the rela-

tionship between dissociation and cognition in

non-clinical samples. High-dissociative persons

have been found to have an advantage on different

cognitive tasks in some studies (12, 46–48), a

disadvantage on different cognitive tasks in other

studies (49–52), whereas some studies report no

differences between high and low dissociative

participants in tests of executive functions and

working memory (53, 54). Although not signifi-

cant, all the correlations in our sample were

negative, indicating a common direction. The

reason for this may be that we used domain results

of the neuropsychological performance rather than

results on single tests or single variables. Another

explanation may be that in a clinical sample like

ours, with high proportions of persons with patho-

logical dissociation, the possible advantageous

effect of non-pathological dissociation would be

overshadowed. Our results differ, however, from a

recent study which suggests that patients with

dissociative disorders present elevated frontal

function and enhanced working memory perfor-

mance (55). A possible, but perhaps not plausible,

explanation for this discrepancy in results could be

that dissociation is associated with reduced frontal

functions in patients with BPD, but with elevated

frontal function in patients with dissociative dis-

orders. Another possibility is that a diagnosis of

dissociative disorders not necessarily implies mem-

bership in the pathological taxon as measured with

the DES-T.

Dissociation and treatment outcome

Dissociative symptoms have been associated with

poorer outcome following psychotherapeutic treat-

ment in patients with panic disorder, agoraphobia

and obsessive–compulsive disorder, as well as in

patients with affective, anxiety or somatoform

disorders (56–58). Although these studies did not

include patients with BPD, our study may give a

hypothesis for a neuropsychological-based expla-

nation to the findings. We found both dimensional

and categorical measures of dissociation to be

associated

with

dysfunctions

in

fundamental

cognitive abilities. It may therefore not be the

dissociation per se that results in poorer outcome,

but the cognitive functioning of the patients

involved in those studies. Such a hypothesis,

however, is not entirely congruent with the results

presented in a recent study by Braakmann et al.

(59) in which no negative prognostic value was

found of dissociative symptoms on the effect of

inpatient Dialectic Behavior Therapy. The authorsÕ

hypothesis is that this is because of the specific

focus on dissociative symptoms facilitated by an

inpatient setting. Further studies on the treatment

of BPD should investigate the prognostic value of

neuropsychological variables as well as psycho-

pathological measures.

Limitations

The two groups of patients with BPD were

homogenous with respect to demographic and

clinical variables, including depressive symptoms

and GAF values, except for degree of dissociative

symptoms. One could argue that patients in the

pathological dissociation group also had a disso-

ciative disorder; however, as SCID-D was not used

in this study, we cannot give answer to this

question.

These

findings

may

therefore

be

explained by comorbidity alone, but another and

in our view more plausible explanation would be

that patients with BPD who also show pathological

dissociation represent a more severe subgroup of

patients with BPD. Such an interpretation is

supported by studies showing enhanced working

memory performance in patients with dissociative

disorders (55).

Most patients in our sample were taking psy-

chotropic medication when the tests were con-

ducted, and no steps were taken to reduce what

influences medication may have had. For SSRIs,

some positive effects have been found on neuro-

psychological performance in healthy subjects (60).

Atypical antipsychotics have been found to have

some negative effects on attention, but no effect on

executive functions in healthy subjects (61). Con-

sidering that patients in both groups used medica-

tion and that SSRIs and atypical neuroleptics were

the most frequently used medication in both

samples, it is unlikely that medication influences

would have caused the reduced neuropsychological

performance found in this study.

Given the high comorbidity of DSM-IV axis I

and II disorders in BPD (15, 16), comorbidity was

not a criterion for exclusion except for severe

ongoing substance abuse. PTSD and lifetime

affective disorders were the most frequent comor-

bid disorders. When comparing the two groups

with and without pathological dissociation, we

Haaland and Landrø

390

found no differences in frequency of those comor-

bid disorders. Average GAF scores indicated that

patients were moderately affected. Our sample may

therefore be considered representative of patients

in general clinical settings, and inferences may be

drawn from this sample to these patients, but not

necessarily to the patient group with BPD and no

comorbid disorders without psychotropic medica-

tion. Future studies should take the effect of

comorbidity and medications systematically into

consideration.

Studies similar to ours, in which neuropsycho-

logical measures and its relations to psychopatho-

logical phenomenon are investigated, may expand

our understanding of the behavioral characteristics

of various psychiatric disorders. Further studies

will have to be undertaken to specify the connec-

tions that exist between pathological dissociation

in patients with BPD, various aspects of neuro-

psychological functioning and psychosocial func-

tioning and other outcome variables.

Acknowledgements

We thank study participants, colleagues at Sørlandet Hospital

HF for assistance in recruiting the participants, Torunn

Haaland PhD for valuable language consultation, and research

nurse Gro Steensohn for assisting us with the data collection.

The study was financially supported by Sørlandet Hospital HF

and the Southern Norway Regional Health Authority. The

content of this manuscript and the manuscript itself have never

been published either electronically or in print.

Declaration of interest

None.

References

1. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, Widiger TA, Livesley

WJ

, Siever LJ. The borderline diagnosis I: psychopathol-

ogy, comorbidity, and personality structure. Biol Psychi-

atry 2002;51:936–950.

2. Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, Linehan MM, Bohus M.

Borderline personality disorder. Lancet 2004;364:453–461.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statisti-

cal manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR, 4th, text

revision edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric

Association, 2000.

4. Judd PH. Neurocognitive impairment as a moderator in the

development of borderline personality disorder. Dev Psy-

chopathol 2005;17:1173–1196.

5. LeGris J, van Reekum R. The neuropsychological correlates

of borderline personality disorder and suicidal behaviour.

Can J Psychiatry 2006;51:131–142.

6. Stiglmayr CE, Shapiro DA, Stieglitz RD, Limberger MF,

Bohus M

. Experience of aversive tension and dissociation

in female patients with borderline personality disorder – a

controlled study. J Psychiatr Res 2001;35:111–118.

7. Stiglmayr CE, Ebner-Priemer UW, Bretz J et al. Dissocia-

tive symptoms are positively related to stress in borderline

personality disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2008;117:139–

147.

8. Ross CA, Joshi S, Currie R. Dissociative experiences in the

general population. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:1547–1552.

9. Bernstein EM, Putnam FW. Development, reliability, and

validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986;

174:727–735.

10. Putnam FW, Carlson EB, Ross CA et al. Patterns of dis-

sociation in clinical and nonclinical samples. J Nerv Ment

Dis 1996;184:673–679.

11. Waller NG, Putnam FW, Carlson EB. Types of dissociation

and dissociative types: a taxometric analysis of dissociative

experiences. Psychol Methods 1996;1:300–321.

12. de Ruiter MB, Phaf RH, Elzinga BM, van Dyck R. Disso-

ciative style and individual differences in verbal working

memory span. Conscious Cogn 2004;13:821–828.

13. Cima M, Merckelbach H, Klein B, Shellbach-Matties R,

Kremer

K

. Frontal lobe dysfunctions, dissociation, and

trauma self-reports in forensic psychiatric patients. J Nerv

Ment Dis 2001;189:188–190.

14. Jones B, Heard H, Startup M, Swales M, Williams JMG,

Jones RSP

. Autobiographical memory and dissociation in

borderline personality disorder. Psychol Med 1999;29:

1397–1404.

15. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED et al. Axis I

comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Am J

Psychiatry 1998;155:1733–1739.

16. Becker DF, Grilo CM, Edell WS, McGlashan TH. Com-

orbidity of borderline personality disorder with other

personality disorders in hospitalized adolescents and

adults. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:2011–2016.

17. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured

Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Re-

search Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I

⁄ P). New York:

Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute,

1997.

18. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured

Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders,

(SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press,

Inc., 1997.

19. Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary

depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967;6:278–296.

20. Wechsler D, Nyman H, Nordvik H. Wais-III: Wechsler

Adult Intelligence Scale: manual (Norwegian edition), 3rd

edn. Stockholm: Psykologifo¨rlaget, 2003.

21. Conners CK. ConnersÕ Continuous Performance test

(CPTII). Technical guide and software manual. North

Tonawanda, NY: Multi Health Systems Inc., 2002.

22. Gronwall DM. Paced auditory serial-addition task: a

measure of recovery from concussion. Percept Mot Skills

1977;44:367–373.

23. Gold JM, Carpenter C, Randolph C, Goldberg TE, Wein-

berger

DR

. Auditory working memory and Wisconsin

Card Sorting Test performance in schizophrenia. Arch

Gen Psychiatry 1997;54:159–165.

24. Callicott JH, Ramsey NF, Tallent K et al. Functional

magnetic resonance imaging brain mapping in psychiatry:

methodological issues illustrated in a study of working

memory in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology

1998;18:186–196.

25. Lund-Johansen M, Hugdahl K, Wester K. Cognitive func-

tion in patients with ParkinsonÕs disease undergoing ste-

reotaxic thalamotomy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry

1996;60:564–571.

26. Shum D, Short L, Tunstall J et al. Performance of children

with traumatic brain injury on a 4-disk version of the

Dissociation and cognition in BPD

391

Tower of London and the Porteus Maze. Brain Cogn

2000;44:59–62.

27. Spreen O, Strauss E. A compendium of neuropsychological

tests: administration, norms, and commentary, 2nd edn.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

28. Heaton RK. Wisconsin card sorting test manual. Odessa,

FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., 1981.

29. Lezak MD. Neuropsychological assessment, 3rd edn. New

York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

30. Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR, Lee GP. Different

contributions of the human amygdala and ventromedial

prefrontal cortex to decision-making. J Neurosci 1999;19:

5473–5481.

31. Brandt J. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test: development

of a new memory test with six equivalent forms. Clin

Neuropsychol 1991;5:125–142.

32. Benedict RHB, Schretlen D, Groninger L, Brandt J. Hop-

kins Verbal Learning Test – Revised: normative data and

analysis of inter-form and test-retest reliability. Clin Neu-

ropsychol 1998;12:43–55.

33. Kimura D. Right temporal-lobe damage. Perception of

unfamiliar stimuli after damage. Arch Neurol 1963;8:264–

271.

34. Waller NG, Ross CA. The prevalence and biometric

structure of pathological dissociation in the general

population: taxometric and behavior genetic findings.

J Abnorm Psychol 1997;106:499–510.

35. Lenzenweger MF, Clarkin JF, Fertuck EA, Kernberg OF.

Executive neurocognitive functioning and neurobehavioral

systems indicators in borderline personality disorder: a

preliminary study. J Personal Disord 2004;18:421–438.

36. van Reekum R, Conway CA, Gansler D, White R, Bachman

DL

. Neurobehavioral study of borderline personality dis-

order. J Psychiatry Neurosci 1993;18:121–129.

37. OÕLeary KM, Brouwers P, Gardner DL, Cowdry RW.

Neuropsychological testing of patients with borderline

personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1991;148:106–111.

38. Swirsky-Sacchetti T, Gorton G, Samuel S, Sobel R, Genetta-

Wadley A, Burleigh B. Neuropsychological function in

borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychol 1993;49:

385–396.

39. Kunert HJ, Druecke HW, Sass H, Herpertz SC. Frontal lobe

dysfunctions in borderline personality disorder? Neuro-

psychological findings. J Personal Disord 2003;17:497–509.

40. Sprock J, Rader TJ, Kendall JP, Yoder CY. Neuropsycho-

logical functioning in patients with borderline personality

disorder. J Clin Psychol 2000;56:1587–1600.

41. Bazanis E, Rogers RD, Dowson JH et al. Neurocognitive

deficits in decision-making and planning of patients with

DSM-III-R borderline personality disorder. Psychol Med

2002;32:1395–1405.

42. Beblo T, Saavedra AS, Mensebach C et al. Deficits in visual

functions and neuropsychological inconsistency in Bor-

derline Personality Disorder. Psychiatry Res 2006;145:127–

135.

43. Haaland VØ, Landrø NI. Decision making as measured

with the Iowa Gambling Task in patients with borderline

personality disorder. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2007;13:699–

703.

44. Stevens A, Burkhardt M, Hautzinger M, Schwarz J, Unckel

C

. Borderline personality disorder: impaired visual per-

ception and working memory. Psychiatry Res 2004;125:

257–267.

45. Silbersweig D, Clarkin JF, Goldstein M et al. Failure of

frontolimbic inhibitory function in the context of negative

emotion in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychi-

atry 2007;164:1832–1841.

46. de Ruiter MB, Phaf RH, Veltman DJ, Kok A, van Dyck R.

Attention as a characteristic of nonclinical dissociation: an

event-related potential study. NeuroImage 2003;19:376–

390.

47. Veltman DJ, de Ruiter MB, Rombouts SA et al. Neuro-

physiological correlates of increased verbal working

memory in high-dissociative participants: a functional

MRI study. Psychol Med 2005;35:175–185.

48. DePrince AP, Freyd JJ. Dissociative tendencies, attention,

and memory. Psychol Sci 1999;10:449–452.

49. Wright DB, Livingston-Raper D. Memory distortion and

dissociation: exploring the relationship in a non-clinical

sample. J Trauma Dissociation 2002;3:97–109.

50. Kindt M, van den Hout M. Dissociation and memory

fragmentation: experimental effects on meta-memory but

not on actual memory performance. Behav Res Ther

2003;41:167–178.

51. Freyd JJ, Martorello SR, Alvarado JS, Hayes AE, Christ-

man JC

. Cognitive environments and dissociative tenden-

cies: performance on the standard Stroop task for high

versus low dissociators. Appl Cogn Psychol 1998;12:S91–

S103.

52. Giesbrecht T, Merckelbach H, Geraerts E, Smeets E. Dis-

sociation in undergraduate students: disruptions in execu-

tive functioning. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192:567–569.

53. Bruce AS, Ray WJ, Bruce JM, Arnett PA, Carlson RA. The

relationship between executive functioning and dissocia-

tion. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2007;29:626–633.

54. Wright DB, Osborne JE. Dissociation, cognitive failures,

and working memory. Am J Psychol 2005;118:103–113.

55. Elzinga BM, Ardon AM, Heijnis MK, De Ruiter MB, van

Dyck R, Veltman DJ. Neural correlates of enhanced

working-memory performance in dissociative disorder: a

functional MRI study. Psychol Med 2007;37:235–245.

56. Michelson L, June K, Vives A, Testa S, Marchione N. The

role of trauma and dissociation in cognitive-behavioral

psychotherapy outcome and maintenance for panic disor-

der with agoraphobia. Behav Res Ther 1998;36:1011–1050.

57. Rufer M, Held D, Cremer J et al. Dissociation as a pre-

dictor of cognitive behavior therapy outcome in patients

with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Psychother Psycho-

som 2006;75:40–46.

58. Spitzer C, Barnow S, Freyberger HJ, Grabe HJ. Dissociation

predicts symptom-related treatment outcome in short-term

inpatient psychotherapy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2007;

41:682–687.

59. Braakmann D, Ludewig S, Milde J et al. Dissoziative

Symptome im Verlauf der Behandlung der Borderline-

Perso¨nlichkeitssto¨rung [Dissociative symptoms during

treatment of borderline personality disorder]. Psychother

Psychol Med 2007;57:154–160.

60. Dumont GJH, de Visser SJ, Cohen AF, van Gerven JMA.

Biomarkers for the effects of selective serotonin reuptake

inhibitors (SSRIs) in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol

2005;59:495–510.

61. de Visser SJ, van der Post J, Pieters MSM, Cohen AF, van

Gerven JMA. Biomarkers for the effects of antipsychotic

drugs in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001;

51:119–132.

Haaland and Landrø

392

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

The Relationship Between Personality Organization, Reflective Functioning and Psychiatric Classifica

Developmental protective and risk factors in bpd (using aai)

Functional Origins of Religious Concepts Ontological and Strategic Selection in Evolved Minds

Changes in passive ankle stiffness and its effects on gait function in

Assessment of thyroid, testes, kidney and autonomic nervous system function in lead exposed workers

2010 3 MAY Immunology Function, Pathology, Diagnostics, and Modulation

Functional Origins of Religious Concepts Ontological and Strategic Selection in Evolved Minds

Changes in passive ankle stiffness and its effects on gait function in

Impaired Sexual Function in Patients with BPD is Determined by History of Sexual Abuse

Clinical and neuropsychological correlates of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy detected metabo

Assessment of thyroid, testes, kidney and autonomic nervous system function in lead exposed workers

Curcumin improves learning and memory ability and its neuroprotective mechanism in mice

Relationship Between Dissociative and Medically Unexplained Symptoms in Men and Women Reporting Chil

Demidov A S Generalized Functions in Mathematical Physics Main Ideas and Concepts (Nova Science Pub

2008 4 JUL Emerging and Reemerging Viruses in Dogs and Cats

Angielski tematy Performance appraisal and its role in business 1

więcej podobnych podstron