Documents, Photography, Postmemory:

Alexander Kluge, W. G. Sebald, and the

German Family

Mark M. Anderson

Germanic Languages, Columbia

Abstract

The article examines two major German writers of documentary fic-

tion, Alexander Kluge and W. G. Sebald, who incorporate photographs into their

work as part of a complex strategy of realism. Both authors are strongly marked by

the legacy of Nazi propaganda and its manipulation of photographic images; both

authors reflect on the relationship between trauma, war, memory, and representa-

tion, especially with regard to family histories. Kluge’s emotionally flat documen-

tary account of the Allied bombing of his hometown reveals a problematic deaden-

ing of personal and familial relations. Sebald’s semiautobiographical fictions, whose

German narrators are riven by their disrupted family histories, can only be partially

understood through Marianne Hirsch’s notion of “postmemory.” Despite common

political and stylistic traits, the writings of Kluge and Sebald ultimately forge quite

different literary esthetics.

In the mid-1960s and the early 1970s, a new kind of visual realism began

to assert itself in European and American literature. This turn toward

the image—especially the photographic image—could be observed most

closely in literary works that incorporated actual pictures into the typo-

graphic text, not as illustrations but as constitutive, nonsupplementary

parts of the whole. It could also be seen in works that gave verbal descrip-

tions of photographs without actually showing them and yet made issues

of vision and visuality central to the story itself; Cortázar’s 1959 story “Las

Poetics Today

29:1 (Spring 2008) DOI 10.1215/03335372-2007-020

© 2008 by Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics

10

Poetics Today 29:1

Babas del Diablo” (“Blow Up”), where a photograph seems to hold the

evidentiary key to a crime, is the paradigmatic example of these. But above

all what W. J. T. Mitchell (1994) has termed the “pictorial turn” in postwar

cultural practice could be registered in a heightened awareness of the visual

character of the literary medium per se, from the “sculptural” graphics

of concrete poetry to the made-for-cinema crime thriller or sentimental

romance, organized as a series of camera “takes.” If Walter Pater, at the

end of the nineteenth century, famously described the arts to be aspiring

toward the “condition of music,” then in the age of the photograph and the

cinema, the literary arts seem to aspire to a “visual condition.”

While participating in this general turn in postwar European and Ameri-

can culture, German literature presents a special case because of the prob-

lematic status of the image after the Hitler period. Few governments had

mobilized visuality for such notorious ideological ends to such an extent

as the Nazis. Propaganda images in journals like the Völkischer Beobachter

and Der Stürmer, party control of documentary and feature films, even the

strategically visual organization (and subsequent media dissemination) of

political gatherings, marches, the führer’s public arrivals and departures—

all these images contributed to an enormous, genocidal, visual lie. After

the defeat of the Nazis, these mythic and mystifying images suddenly dis-

appeared, provoking a rupture in the collective national narrative but also

a combined fascination and uneasiness with this forbidden visual legacy.

Young German artists and writers coming of age during the student move-

ment of the late 1960s followed two distinct avenues of response: on the

one hand, a dehistoricizing, “American” celebration of popular images

(the “pop art” alternative) and, on the other hand, a fact-driven politiciza-

tion of the image that sought to recover a problematic, partly invisible past

(“documentarism”).

In German practice, these strategies often overlapped, operating as

they did in the charged context of student rebellion against Germany’s

1. W. J. T. Mitchell has been a powerful voice in the discussion of images and texts for

twenty-five years, from The Language of Images (1980) to What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and

Loves of Images

(2005). Clas Zilliacus (1979) provides an early but still useful overview of the

international trend toward documentary fiction, starting in the 1960s with authors such as

Truman Capote and Norman Mailer in the United States and Rolf Hochuth and Peter Weiss

in Germany. Various terms were coined for the new genre, including “faction,” “literature of

fact,” “factography,” “documentary literature,” and “documentarism” (ibid.: 97).

2. For a concise general discussion of “the power of images” in Nazi Germany, see the

online essay by David Crew (2006) on photography, the Holocaust, and the Nazi state as

part of a general discussion of German History after the Visual Turn. Rolf Sachsse’s Die

Erziehung zum Wegsehen

(2003) argues that the Nazi state carefully fostered “happy images” of

daily life under Hitler in order to encourage Germans to “look away” from its negative sides

and to “overlook” its victims.

fascist legacy, the anti–Vietnam War protest, and artistic provocation. For

instance, the young art student Anselm Kiefer caused an outrage by photo-

graphing himself performing the (illegal) Hitler salute while standing on

blocks in a bathtub filled with water or, in a later series entitled “Occu-

pations” (1969), in public squares in various European cities. The small,

black-and-white, amateur snapshots owed much to pop art strategies of

instantaneity, seriality, and the transgression of high and low culture; they

repeated the same rather banal and formally unimpressive image again

and again, much like Andy Warhol’s serial images of Marilyn Monroe or

the Campbell soup cans. But, at the same time, they pushed the political

and juridical limits of representation and nearly resulted in Kiefer’s expul-

sion from the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie. (Only the intervention of one of

his teachers, a camp survivor, saved him.)

On the literary front, the charismatic poet and novelist Rolf Dieter Brink-

mann mixed provocative photographic images with unconventional liter-

ary texts whose typographic layouts—as in the anthology Acid, coedited

with Rainer Rygulla, which would quickly achieve cult status—signaled

their allegiance to pop art, the Beat generation, and a general philosophy

of rebellion. The text/image question infuses all his writing, most obvi-

ously in his 1968 verse collection Godzilla, its twenty-two poems printed

over photographic images of female models in bathing suits. The images

could derive from the world of advertising or erotic magazines and are

cropped to focus on pelvis or breasts; the poems are by turns erotic, vulgar,

childlike, and sarcastic send-ups of the commercialization of sex. After his

death in 1975 in a traffic accident at the age of thirty-five, Brinkmann’s

widow published a facsimile edition of diaries and workbooks that made

clear just how important the notion of visual and typographic interaction

was for his creative impulse: “Starting in September 1971, Brinkmann cre-

ated four volumes of material that he worked on simultaneously. He cre-

ated collage texts with photos, press releases, advertisements, paper money,

postcards and letters” (Brinkmann 1987: from the first [unnumbered] page

of the editorial afterword). Elaborately titled “Investigations into the Defi-

nition of a Feeling for Rebellion” (there are also numerous subtitles), it has

secured Brinkmann’s posthumous fame as one of the most innovative and

iconoclastic writers of his generation, an angry German pop author of the

1960s who prepared the way for postmodern prose writers of the 1980s and

1990s.

But if everything in Germany in these years tended toward the politi-

cal, basic differences in what one might term the speed of the image dis-

tinguished various artistic practices. Pop art makes use of a “fast” image

in order to produce immediate, powerful, clashing impressions; as with

Anderson

•

Documents, Photography, Postmemory

11

1

Poetics Today 29:1

advertising, emphasis is placed on the readily consumable message, on the

“now” of aesthetic, sensual response or, at times, of political and social

anger. The same is true of some documentary literature that seeks immedi-

ate ideological effects and makes use of a readily identifiable political mes-

sage. But a modernist-inspired form of documentary literature, going back

to the Weimar experiments of Brecht, Döblin, Piscator, and others, prefers

instead a “slow” image, which delays and problematizes viewer response;

the image should lead to reflection, abstraction, critical examination of the

past and the ideological character of its representation. Thus, in the early

stages of German documentarism, whose political and moral anger was

fanned by the so-called “Auschwitz trials” of former camp guards and SS

officers in Frankfurt in 1963–65, documents often took on the role of legal

evidence, exposing the cover-up and obfuscation of the Nazi past during

the first two decades following the war. Peter Weiss’s 1965 play The Inves-

tigation

drew on legal transcripts, newspaper accounts, and the author’s

own attendance of the Frankfurt trial of Auschwitz guards and SS officers

in order to put the criminal facts (including the defendants’ actual names)

into visual form on the stage. Despite the play’s clear political orienta-

tion, its rigorously unemotional, highly formalized musical language (it

was subtitled “An Oratorio in Eleven Chants”) required audiences to do a

double take, reconciling monstrous crimes with mundane personal details,

historical atrocities with epic form. It premiered simultaneously in some

twenty German and European cities, seeking thereby to concentrate and

accelerate the play’s political and aesthetic impact.

Film director, media theorist, television producer, and author Alexan-

der Kluge made his literary debut in 1962 with his pathbreaking series of

documentary-like “biographies” (Lebensläufe) of Nazi perpetrators, victims,

and other war participants. The cosigner of the Manifesto of Oberhausen

(1962), proclaiming the “collapse of the conventional German film,” Kluge

occupied the fertile zone between film and literature where photographic

images provided a common realistic element that would disrupt conven-

tional storytelling and filmmaking. But Kluge’s use of the documentary

mode was never simple, nor simply ideological. As Andreas Huyssen (1988:

122) has noted, Kluge’s strongest documentary writing has more to offer

than most of the 1960s documentarism because it goes beyond simple fac-

tual reportage and political enlightenment to embrace “the experiments

of the Weimar avant-garde, especially Brecht and the montage tradition.”

Typical of this technique is the mixture of image and text, in which fac-

tual historical information is indistinguishable from invented (if seemingly

realistic) narrative elements, which he used to superb effect in the par-

tially autobiographical, pseudo-documentary montage texts published in

Anderson

•

Documents, Photography, Postmemory

1

1977 under the ambiguous title Neue Geschichten (a title that can mean “new

stories” but also “new histories”).

A good example is his “The Aerial Attack of Halberstadt on April 8,

1945,” which describes the bombing of his hometown that he experienced

as a thirteen-year-old boy at the end of the war. Using photographs, tech-

nical drawings, newspaper interviews, and verbal narrations, it seems to

offer a series of discrete, individual perceptions of the bombing “from the

ground,” that is, as it was experienced by the participants: a movie-house

employee just after a bomb has partially destroyed the theater; a mother

attempting to flee her home with her children; two women in an antiair-

craft tower who are injured or killed; a high-ranking English officer who

participated in the bombing and who reflects on the event in a postwar

interview. The text pursues a primary documentary, political aim: to focus

attention on a historical event that was partially suppressed after the war

by the occupying Allied forces, who did not want to be reminded of the

“capitalist logic” of the bombing at this late stage in combat. Yet much of

the material is simulated, and as Kluge himself noted, the most “realistic”

parts, including a postwar interview by the Neue Zürcher Zeitung with one of

the raid’s English commanders, stem from his own very active imagination,

not the archive. His love of paradox and self-contradiction is constant. “I

invent almost nothing, but not everything that stands in quotes is actually a

citation,” he noted in a recent interview. “I always proceed realistically, but

because I consider reality to be the greatest liar of all, our errors are often

for me a more precise record than the so-called facts” (Hage 2003: 207).

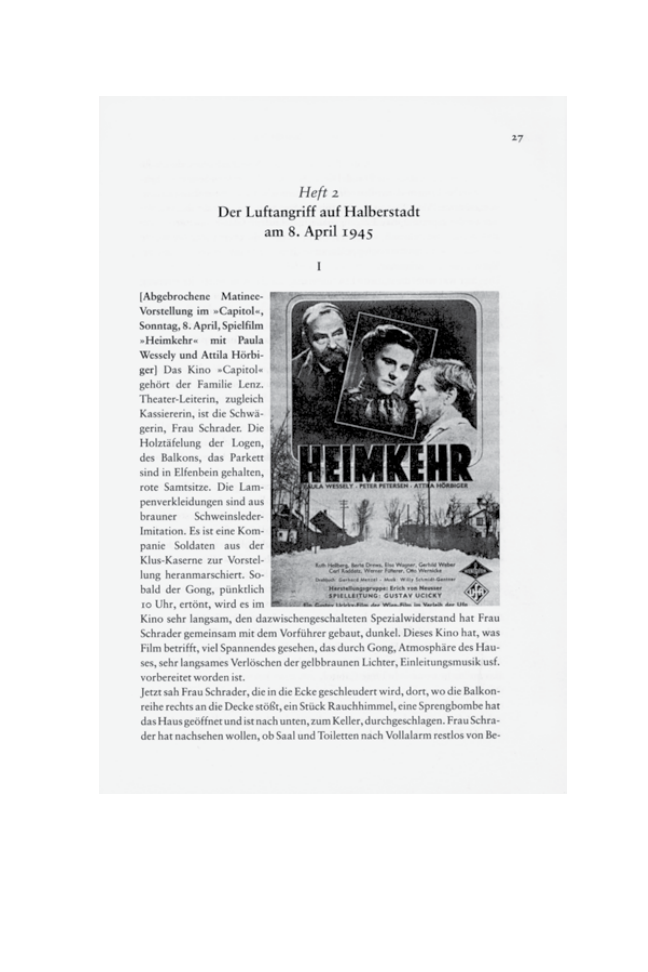

That the images in this text are not simple factual representations of

reality, to be seen (and seen through) at a single glance, is clear from the

opening picture of a poster for the popular movie Heimkehr (Homecoming)

(figure 1). In one sense, the advertisement serves as an appropriate contem-

porary document, since this film was playing, or is said by Kluge to have

been playing, in the Capitol cinema in Halberstadt when the first bombs

fell. But its use is highly ironic. Directed in 1941 by Gustav Ucicky and star-

ring Paula Wessely, the film is set in 1939 on the eve of the Nazi invasion of

Poland. Its tale of the courageous but persecuted ethnic German minority

in Poland thus served as a perfect foil for Propaganda Minister Josef Goeb-

bels’s claim that the invasion represented Poland’s “return home” into the

greater Reich (Heim ins Reich); Ucicky himself claimed the film should make

manifest the racial difference between Germans and Slavs. But the photo-

3. The film Heimkehr (Homecoming), described by Nazi censors as “politically valuable to the

State,” opened in 1941 at the Ufa Palast am Zoo in Berlin and received a number of prizes,

including that of the Venice film festival. After the war, Ucicky was banned from work-

ing as a director by the Allies. Nobel Prize–winning author Elfriede Jelinek has described

1

Poetics Today 29:1

Figure 1

Poster for the popular movie Heimkehr (Homecoming). From Kluge 2000:

27

Anderson

•

Documents, Photography, Postmemory

1

graph in Kluge’s text goes beyond the irony of historical content. Because

it is a reproduction of a publicity image which refers in turn to a cinematic

(and propagandistic) representation of the war, it serves as a mise en abîme

of photographic truth in general, suggesting the constructed nature of the

cinematic war image and even of Kluge’s own narrative. Where is the line

separating historical fact from propaganda and visual representation? In

no case is the understanding of this opening image immediate; its mean-

ing, or variety of possible meanings, emerges slowly over time as the prod-

uct of reading, rereading, research, and reflection. The poster functions in

this sense not as a document of reality but as a set of questions about reality

and its representation.

The subsequent images in Kluge’s text also present serious formal

obstacles to quick consumption: their grainy, dark, unfocused quality;

the black-and-white format, emphasizing their remoteness as historical

artifacts; the unfamiliarity of illustrations taken from technical manuals;

in some cases, the lack of captions or, contrarily, the lengthy theoretical

captions; and finally, the fragmented, discontinuous nature of the images,

which offer only snippets of the whole event. One should note, however,

that these formal “difficulties” are part of the rhetorical means by which the

images are put forward as “authentic” documents: since the images resist

catering to the viewer’s aesthetic enjoyment, since they are hard to read

(or simply dull or insignificant), they seem not to be aesthetic constructs.

This verisimilitude, what Barthes might have termed their “reality effect,”

is strengthened by a brief narrative of the “unknown photographer,” who

is said to have taken pictures of the city during the raid. Ironically, he is

arrested by local authorities for suspicious activity and narrowly escapes

execution; but his story explains the origin, survival, and authenticity of

the images documenting the bombing. Like the editor of an eighteenth-

century novel introducing the manuscript he has supposedly found in a

trunk in the attic, Kluge pretends to be offering a piece of reality itself,

although characteristically neither he nor a first-person narrator ever

appears in the story itself.

In his introduction to the Neue Geschichten, Kluge (1988: 103) explicitly if

somewhat cryptically links the formal discontinuities of text and images

to his own experience of the bombing: “A few of the stories appear to

have been cut short. . . . The form of a bomb blast makes an impression.

Such a form is constituted by being cut short. On April 8, 1945, I was ten

meters away from such a blast.” This formal quality of being “cut short,” the

Heimkehr

as “the worst propaganda film the Nazis ever made” (ourworld.compuserve.com/

homepages/elfriede/wessely.HTM).

1

Poetics Today 29:1

emphasis on interruptions and gaps as the crucial components of historical

experience, is also embodied by the matter-of-fact, illustrative photographs

documenting the destroyed city. The very neutral, mechanical quality of

these images is part of the text’s documentary self-presentation, according

to which the “objective” eye of the camera simply records what happened

(“Geschichte” as history, not personal story). At the same time, this very

neutrality—emphasized by captions identifying particular street names

and neighborhoods—seems grotesquely inappropriate for the presenta-

tion of what is after all the brutal destruction of the author’s hometown,

the killing and horrific suffering of thousands of civilians, many of them

women and children. Kluge’s images are not just “slow,” they are “cold”;

justifiable as documents, they irritate or perplex the reader as elements of

a personal story that refuses to be personal.

This “coldness” of the documentary image expresses itself in both the

style and the content of the verbal text, which foregrounds the extreme

neutrality or even absence of the narrating self. Where is the child who

experienced the bombing “at ten meters”? Where is the adult reflecting

on the destruction of his home, the deaths of neighbors, friends, per-

haps close family members? The documentary, even “bureaucratic” or

“lawyerly” style is maintained even in descriptions of horrifying events.

Indeed, at times the story seems to mock the victims and their automaton-

like responses. After the bombing of the movie house, for instance, the

female manager thinks only of getting ready for the next show, since (we

are told) no “catastrophe” could disrupt her “attachment” to the cinema’s

daily schedule of six screenings. Confronted by the dismembered bodies

of the dead soldiers, she feels she should “put things in order at least here”

and then mindlessly places body parts “which no longer belong together”

in a laundry kettle (Kluge 2000: 29). In another sequence, Kluge presents

an elementary schoolteacher named Gerda Baethe, who attempts to save

herself and her three children. Here too the rigorously factual account

of the woman’s terrorized response is unsettling because she thinks like a

practically minded soldier following a “strategy from the ground,” not like

a mother or teacher. She refers to the children as “property” or “troops,”

pokes one of them in the side to see if “the little ones were still function-

ing,” and coolly reflects that she would save the boy and sacrifice the “less

valuable girls, who she believed could be replaced later” (ibid.: 43–44).

Formally, one can argue that Kluge is drawing here on what Helmut

Lethen (2002) has described as the “cold” tradition of the Weimar avant-

garde, the “new objectivity” of Brecht and Döblin that breaks with per-

sonalized, sentimental narratives and sees in photography and cinematic

montage a mechanical ideal of artistic representation. One might also

Anderson

•

Documents, Photography, Postmemory

1

argue that, in highlighting the mechanized, “inhuman” behavior of the vic-

tims, Kluge is realistically depicting the symptoms of trauma; the bombing

has produced an emotional short circuit that blocks the normal expression

of horror, mourning, and empathy. He himself has claimed that at the

time of the story’s composition, which coincided with the left-wing terror-

ist actions of 1976–77, he was interested in discovering a “patriotic core”

for his community by showing Germans in a state of complete powerless-

ness (Hage 2003: 208–9). And of course a “neutral” or “cold” manner of

presentation can heighten the reader’s sense of outrage at the bombings,

which took place when the war was almost over and served little military

purpose.

But at least part of the explanation is to be found in Kluge’s ambiva-

lent relation to the victims: their “inhumane” response stems not so much

from the trauma of the air raid as from their deeper identity (in his view)

as “typically” German subjects, who have been depersonalized, before the

bombing, by the interrelated forces of capitalism and fascism. The state

of traumatized powerlessness merely brings into sharper focus this “defa-

miliarization” (in the dual sense of an alienating inhumanity and lack of

family identity). The cinema employee’s first thoughts are not what might

be happening to her family members or relatives in another part of town

but how she can save her employers’ property; Gerda Baethe attempts to

save her children not out of an elementary maternal urge but as a military

“strategy” where civilians take part in the war effort. Both exist as puppets

who are pulled by the strings of warmongering capitalist and fascist logic,

not as private individuals or family members. (To gauge the ideological

character of Kluge’s depiction, one should contrast these responses with

media representations of the victims of the September 11 bombing of the

World Trade Center, which highlighted their last desperate attempts to

communicate with families, heroically save lives, etc., not their trauma-

tized, automaton-like responses.)

If Kluge’s “cold” text, with its unempathic narrative style and photo-

graphic documentation of the destruction, serves as the index of deficient

human subjectivity, it also marks his own unresolved, hostile relation to

the German victims, whom he can never quite stop thinking of as Nazi

and capitalist perpetrators. Although the section depicting Gerda Baethe

is introduced by the rather dreamy close-up image of a woman, we are

also told that she spent “fourteen glorious days” on a vacation before the

bombing, driving in a convertible with a Nazi who claims that “everything

is a question of organization” (Kluge 2000: 47). Kluge’s absence from the

text is a sign that his own affective, familial, and communal relationships

have been “cut short,” that a “homecoming” is no longer possible, indeed,

1

Poetics Today 29:1

that the very notion of “family” or “home” has been shattered—even and

perhaps especially for German Marxists caught in the ideological cross fire

of the Red Army Faction in the mid-1970s.

The compelling mix of image and verbal narrative in W. G. Sebald’s prose

works both compares and contrasts with the politicized, documentary

phase of West German literature in the 1960s and 1970s. Sebald followed

the Auschwitz trials on a daily basis as a student and has acknowledged his

admiration for the work of Peter Weiss, Alexander Kluge, Klaus Thewe-

leit, and others who combined verbal narratives, documents, and images

to contest Nazi-inspired accounts of the past. Like Kluge, Sebald uses

“slow” images; they are the opposite of the unabashedly trivial, hedonistic,

immediacy-seeking images of pop culture. Uncaptioned, often poorly lit

or focused, they too assert their documentary nature through the very lack

of any overtly pleasing or merely interesting aesthetic quality. A restau-

rant bill, a calling card, an old postcard—they offer themselves as innocu-

ous fragments of the real. But as with Kluge, the reality effect of Sebald’s

images compounds the difficulty of deciphering the verbal narrative, to

which they stand in an oblique but contiguous relation. For Sebald con-

ceived of the pictures as a form of writing. Just as the literary text aspires

to a condition of visuality, his photographs “call out” to be told as stories.

“One doesn’t know [the photographic subjects],” he noted in an interview

about the old photographs he collected and used as inspiration for his own

texts. “And so you have to start thinking hypothetically. Along this route,

you inevitably slip into fiction, the telling of stories. While writing, you see

ways of departing from the images or entering into them to tell your story,

to use them instead of a textual passage, etc.” (Scholz 2000: 51).

Like Kluge, Sebald has also banished color from his images. But unlike

earlier documentary German literature, where the black-and-white format

served primarily to reinforce the realist impression, his use of the format

also recalls the black ink and white page of the surrounding verbal text:

one medium merges into the other. The format also invests the subjects

and the passage of time with a dated quality that is basic to their stories. In

these photographs, the contemporary world is “always already” past; even

snapshots taken recently look old and so hark back to an earlier era. Many

of the images are in fact old photos or postcards—not “ready-mades” that

can circulate as consumable signs of contemporary culture but “ghosts”

4. Interesting in this regard is Kluge’s autobiographical comment that his parents divorced

six months before the bombing took place: “In a sense I became a lawyer in the middle of

the war. I would have done everything to bring the two of them back together. Everything I

think today takes nourishment from this time” (Hage 2003: 209).

Anderson

•

Documents, Photography, Postmemory

1

that have come back from a previous time, their mere existence a challenge

to the reality and permanence of the here and now. “I believe that black-

and-white photography, or rather the gray areas [in it] precisely indicate

this territory between life and death. In the archaic imagination, there was

generally a vast no-man’s land where people continually wandered about”

(ibid.: 52). Far from representing a rejection of present reality, this concep-

tion of history coincides with Benjamin’s messianic notion of a “Jetztzeit”

in which past catastrophes, suffering, and death are part of the reader’s

(or viewer’s) charged apprehension of the present. The text’s documen-

tary gaze simply takes in a much broader range of human and political

history.

Sebald’s critics have consistently overlooked the political aspect in his

literary writing, focusing instead on questions of memory, identity, trauma,

and the “postmodern” epistemological uncertainties of his fictions. But

political polemic was instrumental in his literary breakthrough and emerged

from a sustained critical reflection on what might be called an “ethics” of

documentary realism that began in the early 1980s. In an article of 1982

that provided the basis for his book Luftkrieg und Literatur (translated into

English as The Natural History of Destruction), he laments the general failure

of German writers to provide objective, factual accounts of the destruction

of German cities by Allied bombing. The few works that tried to repre-

sent its cataclysmic nature reach for pathos-laden, apocalyptic, mythical,

and overly literary formulations that cannot do justice to the event—stylistic

failures that, for Sebald, amount to moral failures. A notable exception is

Hans Erich Nossack’s “report” of the Hamburg firebombing in July 1943,

entitled The End (Der Untergang), which is based on firsthand observation. As

Sebald points out, Nossack developed his reportorial style from Stendhal

(also a witness to military devastation in Napoleon’s Italian campaigns),

whose diaries had taught him to “express himself as plainly as possible,

without the usual literary adjectives, without flowery images, more like a

writer of letters and almost in everyday language

.” Nossack’s style in the “report”

(Bericht) of the destruction of Hamburg maintains the documentary style

that would become a “model” for the West German documentary litera-

ture of the 1960s and 1970s, especially that of Kluge. “In direct contrast to

5. During his lifetime, much of the critical response to Sebald’s writing was limited to news-

paper and magazine reviews. Since his death in 2001, academic studies have proliferated so

quickly that it is now difficult to give an overview. Excellent starting points are the recent

anthologies W. G. Sebald: A Critical Companion (Long and Whitehead 2004) and Sebald. Lek-

türen

(Atze and Loquai 2005). Anne Fuchs’s (2004) perceptive and broad treatment of mem-

ory and trauma, which, however, consistently underplays the political dimension of Sebald’s

writing, is representative of the tenor of current academic studies.

10

Poetics Today 29:1

the traditional approach to writing fiction, Nossack experiments with the

prosaic genre of the report, the documentary account, the investigation, to

make room for the historical contingency that breaks the mould of [tradi-

tional] novels” (Sebald 2005: 80–81; translation slightly altered).

Documentary realism is here the ethically valid stylistic response to

catastrophe. Quoting Canetti’s claim that the “precision” and “responsi-

bility” in the diary of a Japanese survivor of Hiroshima provide the “essen-

tial” literary form for “a thinking, seeing human being today,” Sebald

(ibid.: 86) makes a sweeping pronouncement about Nossack’s text that

sounds like his own literary manifesto: “The ideal of truth contained in

the form of an entirely unpretentious report proves to be the irreducible

foundation of all literary effort. It crystallizes resistance to the human ten-

dency to repress any memory that might in some way be an obstacle to

the continuance of life.” Precisely because the traumatized survivor of the

Hamburg bombing cannot remember—he “dare not look back, since there

was nothing behind him but fire”—the memory and transmission of this

event are delegated to those individuals who are “ready to live with the risk

of remembering” (ibid.: 86–87). The writer, and especially the German

writer, has the moral obligation to preserve those painful memories that

normal life tends to efface.

Two years later, Sebald extended this reflection to the representation

of Jewish suffering. In an analysis of Günter Grass’s Diary of a Snail, he

praises those parts of the novel based on actual documentation, such as

the author’s own observation of an election campaign or “the impressively

real details” of the Danzig Jews’ exile furnished by a Jewish historian living

in Tel Aviv; Grass himself, he notes, could not provide these documentary

passages since, like other German writers, he “still know[s] little of the real

fate of the persecuted Jews” (ibid.: 113). The weakest parts of the novel are

his essayistic digressions, which are “pure invention” (ibid.: 114). The sar-

casm in these last words is programmatic: “mere” fiction detracts from the

authenticity—moral and esthetic—of Grass’s text.

Unlike Kluge, Weiss, Grass, and many other German documentarists, how-

ever, and despite what seems like an emotionally neutral, report-like tone

of voice, Sebald’s texts are neither objective nor cold. Throughout works

such as The Emigrants and Austerlitz, one senses the narrator’s subdued

but unmistakable empathy for his subjects’ tales of emigration and loss;

access to history is always through an individual’s personal story. In this

regard, he departs from Kluge’s textual practice, which repeatedly focuses

on the anonymous, collective, bureaucratized aspects of modernity, on its

human disfiguration and “defamiliarization.” Sebald seeks out instead the

Anderson

•

Documents, Photography, Postmemory

11

personal and the eccentric in his subjects, seemingly intent on salvaging

what he can of an individual identity that has been damaged or closed

off. In a very literal sense, his stories are “familiar”—not just because of

their casual presentation of his subjects’ quotidian activities but because

they explicitly focus on family relations. And although the narrator keeps

himself quietly out of the spotlight, his own family narrative is subtly inter-

twined with that of his protagonists. Family photograph albums, memoirs,

and diaries play a fundamental role in the telling of these stories, both

formally and affectively.

An essay by J. J. Long (2003) on Sebald’s use of photography in The Emi-

grants

helps clarify the importance of these family images. Like most critics,

Long argues against a realist, “indexical” understanding of the images as

objective history or memory; rather, they emerge from the intersubjective,

emotionally freighted link between narrator and protagonist and can best

be understood as “postmemories.” Drawing on Marianne Hirsch’s discus-

sion of postmemory and the family photo albums of Holocaust survivors,

he notes that many of the photographs in The Emigrants serve the needs of

the second generation to discover, remember, and mourn a past that is just

beyond their actual experience and memory but nonetheless haunts them.

One of the most surprising claims in Long’s analysis is that these family

images counteract the omnipresent forces of melancholy, historical catas-

trophe and metaphysical pessimism in Sebald’s writings. The “affiliative

gaze” of this second-generation German narrator allows him “to suture

himself into the stories of others and construct a sense of narrative and

biographical continuity as a compensation for exile and loss. . . . The com-

bination of narrative and photography in [The Emigrants] can thus be seen

as an attempt, at the level of form, to counteract the dispersal, dissipation,

and rupture inherent in the historical process” (ibid.: 137).

Long’s reading is consistent with the restorative and inclusive role that

Hirsch (1997) attributes to the family photos of Jewish life in a Polish village

before its destruction during the Second World War, which have been col-

lected in the Tower of Memory in the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

in Washington, DC. Their very conventionality, she writes, “provides a

space of identification for any viewer participating in the conventions of

familial representation; thus the photos can bridge the gap between view-

ers who are personally connected to the event and those who are not. They

can expand the postmemorial circle.” More than a mere list of the vic-

tims’ names or even than a narrative of destruction, these photographs of

the Jewish world “lost to genocide and exile” can contain “the particular

mixture of mourning and re-creation that characterizes the work of post-

memory” (ibid.: 251).

1

Poetics Today 29:1

This notion of postmemory has an obvious persuasive force for Sebald’s

historical position, which differs from that of documentarists like Kluge

and Weiss who experienced the war as adolescents or young adults. “Born

in a village in the Allgäu Alps in May 1944,” he noted in an interview, “I

was one of those who remained almost untouched by the catastrophe then

unfolding in the German Reich [but which] nonetheless left traces in my

memory” (Sebald 2003: vii–viii; translation slightly altered). However, one

might ask whether Hirsch’s (and by extension Long’s) description of post-

memory is not too generous a category, which all but erases the historical

subjectivity of different viewers. By “expanding” the postmemory circle to

“viewers who are personally connected to the event and those who are not,”

Hirsch effaces not only the difference between direct witnesses and would-

be witnesses but also the continuing ideological force of the original event

for present viewers. Despite his manifest empathy for the non-German

victims, Sebald’s German narrator cannot be brought unproblematically

into the same identificatory model of commiseration and “familial look-

ing” that his Jewish protagonists engage in. Despite consensus about the

Holocaust, second-generation Germans and Jews do not have the same

“postmemories.”

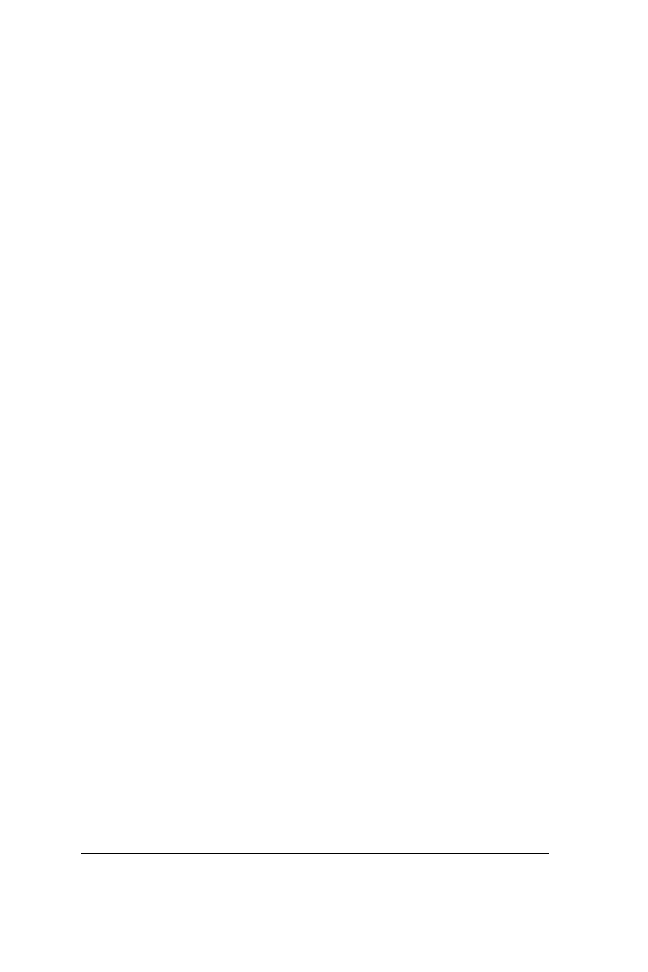

Consider what happens when Sebald’s narrator confronts the pictures

in his family album in the autobiographical story at the end of his first

prose collection Vertigo (see figure 2). In “Il Ritorno in Patria,” his return

to the Bavarian village of his birth summons his memory of the gypsies

who camped at the outskirts of town in the summer months after the war.

Whenever he walked past them, his mother would pick him up and carry

him in her arms. “Across her shoulder I saw the gypsies look up briefly

from what they were about, and then lower their eyes again as if in revul-

sion” (2000: 183). Who these gypsies were, how they managed to survive

the war, or why they had chosen that particular spot for their summer

camp are historical questions that occur to the narrator only as an adult,

years later:

for example, when I leaf through the photo album which my father bought as a

present for my mother for the first so-called Kriegsweihnacht. In it are pictures

of the Polish campaign, all neatly captioned in white ink. Some of these photo-

graphs show gypsies who had been rounded up and put in detention. They are

looking out, smiling, from behind the barbed wire, somewhere in a far corner of

the Slovakia where my father and his vehicle repairs unit had been stationed for

several weeks before the outbreak of war. (Ibid.: 184–85)

Sandwiched into this verbal narrative and, significantly enough, right

after the word “Bilder” (“pictures”) in the German text is the image of a

Anderson

•

Documents, Photography, Postmemory

1

Figure 2

Image from “Il Ritorno in Patria” in Sebald’s Vertigo (2000: 184), where

returning to the Bavarian village of his birth evokes memories of the gypsies who

camped at the outskirts of town during the summer months after the war.

1

Poetics Today 29:1

smiling gypsy mother and child; pasted onto a black page and captioned in

white ink with the word “Zigeuner” (“gypsies”), it clearly comes from the

narrator’s family album.

In an interview, Sebald called attention to the autobiographical origin

of the photo, noting that the picture meant nothing to him when he leafed

through the album as a child but set off a series of uncomfortable histori-

cal speculations when he came across it in the mid-1980s. “It seems to me

quite eye-opening, however, that as early as late-summer 1939 there was a

German NCO [i.e., Sebald’s father] who took pictures of gypsies behind

barbed wire somewhere in Slovakia. It shows that before the war actually

started gypsies were being rounded up and interned in open-air camps in

this puppet-state.” Note also that it was not just the photo that produced

a feeling of alienation but also the belated, accidental, slightly uncanny

manner of its rediscovery. “Only much later did it strike me that there was

a whole tale in that one image” (Bigsby 2001: 145).

Sebald’s use of this image recalls Roland Barthes’s discussion of the

nineteenth-century photograph of a criminal condemned to death in order

to suggest that all photographic subjects bear within them the sign of their

future death and thus of their “pastness” in relation to the present viewer.

As I have written in another context, the picture of the gypsy mother and

child behind barbed wire, on the eve of a war in which their people were

systematically persecuted and murdered by the Nazis, inevitably brings

to mind their “pastness” as historical subjects—with the important dif-

ference that the German narrator’s familial identity is caught up in the

history of their disappearance (Anderson 2003: 109). Because this image

comes from his family album, what was originally offered by the father as

a Christmas present to enrich the family narrative becomes, decades after

the war is over, the basis for the son’s increasingly estranged memory of

his own childhood. Unlike the affective relations that Sebald’s narrator

has chosen to have with the Jewish characters in The Emigrants, his actual

family history is now marked by discord and shame. Even the memory of

his mother in her “protective” maternal role brings back the image of the

gypsies, “who look up briefly . . . and then lower their eyes again as if in

revulsion.”

Such photos in Sebald’s writings—and there are many of them—thus

serve a referential, autobiographical function, without which his ideo-

logical critique of German history, and of his own German family his-

tory, would lose much of its bite. For the overriding problem for second-

generation Germans like the author of Vertigo was not just the Holocaust

itself but the parents’ postwar silence, selective forgetting, or deliberate

falsifications. “The first line of defence was always, ‘I can’t really remem-

Anderson

•

Documents, Photography, Postmemory

1

ber exactly what happened,’” Sebald recalled about his father’s refusal to

talk about his wartime activities. “If you pressed harder then the atmo-

sphere would become increasingly uncomfortable and arguments would

set in” (Bigsby 2001: 143). The inclusion of the family photo in this story

documents what the father would not tell his son—a gap in narration that

has a collective dimension, since it also exists for the millions of German

children in his generation who had a father who served “somewhere in

the East.” “I still don’t know to this day, exactly what my father did or did

not do,” he admitted in the same interview. What he did know—in part by

looking at the kind of photographs that Hirsch (1997: 257) describes as the

“building blocks” of postmemory—is that “the horrendous occurrences

and atrocities [happened] as soon as the Germans marched into Poland in

September 1939” (Bigsby 2001: 143).

The same “defamiliarization” of German family memories can also be

provoked by images of Jews. A revealing example from The Emigrants is the

photo album that the narrator discovers while researching the life of his

elementary schoolteacher in the story “Paul Bereyter.” As a child, he had

no knowledge that his teacher was different from any of the other German

residents in their town, but after this man’s suicide in December 1983, he

learns that, as a “quarter Jew,” the character referred to in the story as

Bereyter was denied the right to teach German children and forced to take

a tutor position with a French family. One series of photographs from the

album shows him smiling with his Jewish fiancée in an idyllic Bavarian

setting before his exile; another shows him with the French family, having

swung within a month “from happiness to misfortune” and become so thin

that “he seems almost to have reached a physical vanishing point” (Sebald

1996: 49). Here again the photographs serve as documentary evidence of

persecution that was covered up after the war and that causes in the narra-

tor a belated sense of responsibility and shame vis-à-vis his own childhood.

Every image of and by children in “Paul Bereyter,” from the narrator’s

own classroom drawings to the group pictures of smiling pupils, takes on

a different meaning and affective value in light of this belated discovery.

Only now can he understand why his teacher might have felt oppressed by

teaching German children or why he would sometimes take off his glasses

and polish them with such assiduity “that it seemed he was glad not to have

to see us for a while” (ibid.: 35).

Sebald explicitly stresses the importance of documentation and refer-

entiality in this story, which not coincidentally begins with a picture of

6. It goes without saying that such remarks about Sebald’s difficult relation with his father

are not meant to equate the suffering of second-generation Jews and Germans but to under-

score their differences.

1

Poetics Today 29:1

the site where the teacher’s suicide took place and an explicit quotation

from the Allgäu newspaper that originally reported the news. The news-

paper is identified by its actual name (Anzeigeblatt), and the correct date of

the obituary is given. Significantly, the narrator initially attempts to imag-

ine his former teacher in various everyday scenes prior to his suicide. But

these attempts, he claims, do not bring him any closer to the man, “except

at best for brief emotional moments of the kind that seemed presumptu-

ous to me. It is in order to avoid this sort of wrongful trespass that I have written

down what I know of Paul Bereyter

” (ibid.: 29; my emphasis). What follows,

consistent with Sebald’s remarks on the obligation of German writers to

preserve Jewish memories with actual documentation rather than invented

stories, is the result of the author’s own research, interviews, and analysis;

the photographs of “Bereyter” (whose actual name was Armin Müller) all

stem from a family album that Sebald was given access to, probably by

Müller’s second wife, who apparently gave him permission to use them

for his story. The fact that Sebald added fictional elements to this actual

historical account, changing Müller’s name and interpolating aspects of

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s biography into the narrative, does not diminish its

documentary, denunciatory character. “The story of the schoolteacher in

The Emigrants

is completely authentic, including the ghastly way in which

this man ended his own life,” Sebald insisted in an interview. “The photo-

graphs are photographs from his album” (Bigsby 2001: 155).

It is worth remembering the political and aesthetic context of the period

in which this story took shape, which stretches from Sebald’s discovery

of Müller’s suicide in January 1984 to the story’s first publication in 1990.

These are the very years in which Bavaria and Austria were roiled by reve-

lations of the local Nazi past—the years in which a high school student

in Passau became the “Nasty Girl” by publishing incriminating details

from the biographies of prominent citizens or in which Austrian president

Kurt Waldheim was forced to admit his selective memory of his activities

during the war. In 1988 conceptual artist Hans Hacke provoked outrage

simply by redecorating the town square of Graz as it had looked after the

Anschluss

with Germany in March 1938, complete with swastikas and Nazi

banners. Another scandal-provoking “commemoration” of the Anschluss

in the same year was Thomas Bernhard’s play Heldenplatz, which con-

fronted spectators with their own auditory self-image by playing tapes of

the enthusiastic chants with which they (or their parents) welcomed Hitler

to Vienna fifty years earlier on the square just outside the theater. Debate

7. Much of the biographical information presented here has not been published before: it

stems from my own research and discussions with Sebald’s family members, Sonthofen resi-

dents, and former colleagues of Armin Müller.

Anderson

•

Documents, Photography, Postmemory

1

raged for weeks after the premiere, graffiti pro and contra was scribbled

on public walls, and one irate woman apparently attacked Bernhard on

the street with an umbrella. Of course this kind of resistance to historical

memory was not limited to Austria or rural Bavaria: Sebald can hardly

have missed the heated academic debates in France and England in this

period about Holocaust revisionists such as Robert Faurisson and David

Irving, who sought to use the very tools of historians to deny the fact of

the Jewish genocide. This was the historical context for the emergence of

The Emigrants

, whose implementation of documentary “evidence” cannot

simply be ascribed to a strategy of postmodernist narrative irony.

On the other hand, it is also clear that, in his actual writing practice,

Sebald did not employ the photographs in his texts as mere records of the

past. While holding to political and moral ideals about literary documen-

tarism put forward in Germany during the 1960s and 1970s, as we have

attempted to show, he also insisted that fact and fiction are both “hybrids,”

that our most personal and vivid memories are often false, that histori-

ography rests on faulty sources, and therefore that photographs are com-

prised of a similarly “irritating” mix of truth and falsification. The first

story in his first prose collection seems, in this regard, a manifesto on real-

ism and the vagaries of memory. Based partly on Stendhal’s half-fictional

autobiography La vie d’Henry Brûlard (itself a hybrid text with many draw-

ings that appears to have given Sebald the idea for his own use of images),

it quotes one of the major nineteenth-century French realist novelists in

order to point out how fragile and self-interested human memory actually

is, especially for someone traumatized by scenes of war: “[Stendhal] writes

that he was so affected by the large number of dead horses lying by the

wayside, and the other detritus of war . . . that he now has no clear idea

whatsoever of the things he found so horrifying then. It seemed to him

that his impressions had been erased by the very violence of their impact”

(Sebald 2000: 6).

Similarly, in an essay on Auschwitz survivors Jean Améry and Primo

Levi, Sebald emphasized that even direct witnesses of Nazi crimes, that

is, “the people who knew what went on” in the death camps, cannot give

us a “true understanding” (“keinen wahren Begriff ”) of their experience,

since the original memory trace is too disturbed. Writing “translates” this

chaotic, pre-linguistic trace within the mind’s recording faculty (“Gedächt-

nis”) into an ordered, discursive “recollection” (“Erinnerung”) that distorts

8. “Fact and fiction . . . are not alternatives. They are both hybrids with the constituent

parts in different measure” (Bigsby 2001: 153). Compare Kluge’s account of “realism” quoted

above, in which he defines reality as “the greatest liar of all” (Hage 2003: 207).

1

Poetics Today 29:1

and betrays its truth content in the very act of mediation (Sebald 1989).

But this insight became the basis for his portrait of emigrants and exiles

who are not victims of the Holocaust but of some less definable experi-

ence of human loss. Extrapolating from this area of traumatized and mel-

ancholic memory, the author of The Emigrants gradually came to see the

entire psychic apparatus of “normal” memory, knowledge, and perception

as informed by the same subjective need for stable, reassuring representa-

tions: “I do think that we largely delude ourselves with the knowledge that

we think we possess, that we make it up as we go along, that we make it

fit our desires and anxieties and that we invent a straight line of a trail in

order to calm ourselves down” (Wood 1998: 25–26).

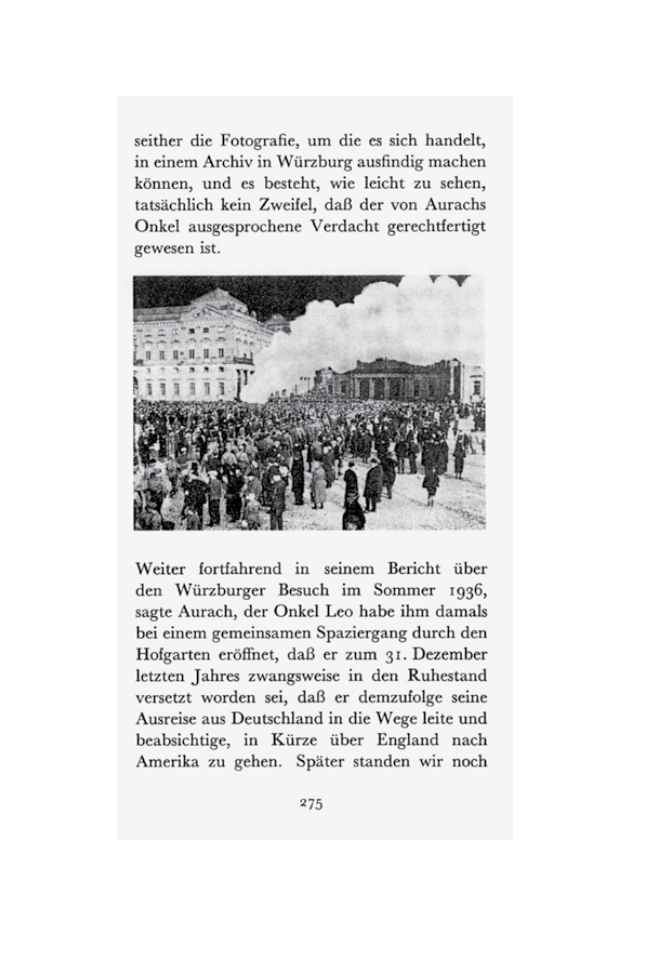

In the last story of The Emigrants we can see both the merit and the prob-

lematic nature of this conception of history for a second-generation Ger-

man author. In “Max Ferber,” we see a photograph of the square before

the Wuerzburg castle (residenzplatz) showing a large crowd of people and

a cloud of smoke billowing up into the sky (figure 3). The image was first

published in the official Nazi daily newspaper in order to document the

book burning that took place there in May 1933. But as Ferber’s uncle

claimed at the time, the Nazis had clearly doctored the image to make it

look this way—a falsification of politics and history, he maintains, that

exposes the mendacity of the Nazi regime “from the very start” (Sebald

1996: 184). Others in the family disagree, and the uncertainty about the

authenticity of the image is left in the air until the narrator visits a Ger-

man archive and proves there can be “no doubt” that the uncle’s suspi-

cions were justified. However, in the very process of unraveling this mix of

reality and propaganda by the Nazis, the narrator inevitably calls to mind

his own manipulation of photographs in his literary texts and the inherent

epistemological instability of the medium itself. For if photographs are the

most convincing form of documentation of the real, they are also the easi-

est to manipulate; indeed, their manipulability has been part of their iden-

tity since their invention in the nineteenth century and a source of con-

troversy ever since. As Alain Jaubert (1989) showed in his study of Stalin’s

“erasure” of Trotsky from official Soviet photographs, the images used to

persuade viewers of a certain empirical reality were in fact instruments of

historical falsification. A similar paradox bedeviled the recent attempt to

document war crimes perpetrated by the German army through photo-

graphs from Soviet archives. Though well intentioned, the organizers of

the exhibition misread some of the images, presenting them as “proof ” of

Wehrmacht

atrocities, whereas closer analysis appeared to reveal a differ-

ent set of victims and perpetrators (Musial 1999). Again, visual material

requires interpretation and can resist definitive explanation just as surely

Anderson

•

Documents, Photography, Postmemory

1

Figure 3

This photographic image from “Max Ferber,” the last story of The Emi-

grants

, shows a cloud of smoke billowing above a large crowd of people assembled

in the square before the Wuerzburg castle (residenzplatz). From Sebald 1996: 184.

10

Poetics Today 29:1

as any written document or, for that matter, a realistic passage in a work of

fiction.

The difficulty of ascertaining the truth of a documentary image is not,

however, an argument in favor of historical indeterminacy or “undecid-

ability”—at least not in Sebald’s or Kluge’s case. As the above discussion

should have made clear, their self-conscious, “difficult” use of images in fic-

tional texts should spur the reader to closer and more attentive engagement

with the nature of historical reality and the documents used to describe it.

Sebald’s narrator in “Max Ferber” himself goes to the archive to investi-

gate the authenticity of a questionable photo. But their images also serve

to complicate the reader’s epistemological understanding of the documen-

tary text by posing a series of textual riddles or games that call attention

to the fictional process itself. For instance, though Kluge’s text goes to

great lengths to certify the origin of certain photographs documenting the

bombing of Halberstadt, it never explains its access to the dialogue and

inner thoughts of the numerous protagonists; the origin of the narrative

voice remains a paradox. Similarly, in explicit reference to the doctored

image of the residenzplatz, Sebald noted that it “pulls the rug from under

the narrator’s business altogether, so that as a reader you might well ask,

What is he on about? Why is he trying to make us believe that pictures are

real?” This overt narrative destabilization—the strategy “of making things

seem uncertain in the minds of the readers” (Wood 1998: 27)—exposes the

cracks in the documentary surface, acknowledges the gaps in the narra-

tive, and calls attention to its own textual unreliability, all in classic mod-

ernist fashion. In this respect, their “slow,” self-conscious documentarism

is the reverse of, say, Steven Spielberg’s simulated documentary style in

Schindler’s List

, filmed with a handheld camera and in black and white,

which encourages viewers to believe that the images on the screen are real,

that they are seeing “history” unfold before their very eyes. Challenging

the reader to believe in and simultaneously doubt the authenticity of their

images, Kluge and Sebald ultimately question the notion that the world

and its representations can be divided into entirely separate categories of

truth and fiction, into factual “documents” and aesthetic constructs. There

is no “pure” historical document.

Personal differences of sensibility and talent aside, Sebald’s use of

photographs, intertextual citations, and historical sources differs from

Kluge’s because of their specific historical positions. Kluge experienced

the war firsthand and began writing about it at a time when large sectors

of West German society had a vested interest in forgetting or denying its

recent Nazi past. Like Weiss and other documentarists of the 1960s and

1970s, he saw literary fiction as a means of disseminating information and

Anderson

•

Documents, Photography, Postmemory

11

raising political consciousness, not despite but because of his modernist use

of documentary material. For Sebald, writing some twenty years later,

this political dimension of literature had by no means disappeared; the

ongoing historical amnesia in the Bavarian society of his youth, as well as

contemporary debates about Holocaust revisionists, kept it very much in

the forefront. Unsurprisingly, the polemical tone of his documentarism is

sharpest when dealing with German perpetrators in World War II in which

his own family narrative is implicated—a legacy of Sebald’s politicization

during the 1960s and a generational rift with his parents he never com-

pletely overcame.

Without any direct experience of this war, however, Sebald has only

second-generation “postmemories” with which to bridge the gap and con-

nect himself imaginatively to its participants. Whereas Kluge’s “cold” texts

are characterized by authorial distance, impassivity, and sarcasm, which

confirm the alienation of his subjects, Sebald’s empathic narratives “famil-

iarize” and personalize them, representing suffering from within and seek-

ing to reestablish family connections—though his texts also repeatedly

insist on the difference between German and Jewish memories. Kluge’s

documentarism limits itself to registering the immediate physical mani-

festations of destruction; the absence of interiority and affect signals the

ongoing effect of trauma and what I have called “defamiliarization,” which

works in formal as well as affective registers. Arising at a later historical

juncture, Sebald’s fiction deals instead with individuals whose trauma lies

deep in their past; documents in his texts are part of the fragile, epistemo-

logically uncertain, but morally urgent task to salvage meaning from the

ruins of their personal histories. The incorporation of photographs thus

serves to “refamiliarize” victims whose lives have been torn apart by war,

exile, and emigration—an accomplishment that is all the more poignant

given the contrary effect of such images on his own German family. Melan-

cholic but also strangely restorative, these ghostlike pictures attempt noth-

ing less than to bring the dead to life—even as they question the reality of

the living.

1

Poetics Today 29:1

References

Anderson, Mark M.

2003 “The Edge of Darkness: On W. G. Sebald,” October 106: 103–21.

Atze, Marcel, and Franz Loquai, eds.

2005 Sebald. Lektüren (Eggingen: Edition Isele).

Bigsby, Christopher

2001 “In Conversation with W. G. Sebald,” in Writers in Conversation with Christopher Bigsby,

2:139–65 (Norwich, CT: Arthur Miller Center for American Studies).

Brinkmann, Rolf Dieter

1987 Erkundungen für die Präzisierung des Gefühls für einen Aufstand: Träume. Aufstände/ Gewalt/

Mord. Reise Zeit Magazin. Die Story ist schnell erzählt. (Tagebuch)

(Reinbek: Rowohlt).

Crew, David F.

2006 “What Can We Learn from a Visual Turn? Photography, Nazi Germany, and

the Holocaust,” H-Net (h-net.msu.edu/cgi-bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=H-German&

month=0609&week=c&msg=9DTccQc5QnxMbKetMn1tXA&user=&pw=, posted Sep-

tember 18.

Fuchs, Anne

2004 Die Schmerzensspuren der Geschichte. Zur Poetik der Erinnerung in W. G. Sebalds Prosa

(Cologne: Böhlau).

Hage, Volker

2003 Zeugen der Zerstörung. Die Literaten und der Luftkrieg (Frankfurt: Fischer).

Hirsch, Marianne

1997 Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-

versity Press).

Huyssen, Andreas

1988 “An Analytic Storyteller in the Course of Time,” October 46: 117–28.

Jaubert, Alain

1989 Making People Disappear: An Amazing Chronicle of Photographic Deception (Washington,

DC: Pergamon-Brassey’s International Defense Publishers).

Kluge, Alexander

1988 “Selections from New Stories, Notebooks 1–18,” translated by Joyce Rheuban, October 46:

103–15.

2000 “Der Luftangriff auf Halberstadt am 8. April 1945,” in Chronik der Gefühle, 2:27–82

(Frankfurt: Suhrkamp).

Lethen, Helmut

2002 Cool Conduct: The Culture of Distance in Weimar Germany, translated by Don Reneau

(Berkeley: University of California Press).

Long, J. J.

2003 “History, Narrative, and Photography in W. G. Sebald’s Die Ausgewanderten,” Modern

Language Review

98: 117–37.

Long, J. J., and Anne Whitehead, eds.

2004 W. G. Sebald: A Critical Companion (Seattle: University of Washington Press).

Mitchell, W. J. T.

1994 Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation (Chicago: University of Chi-

cago Press).

Musial, Bogdan

1999 “Bilder einer Ausstellung. Kritische Anmerkungen zur Wehrmachtsausstellung,”

Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte

4: 563–93.

Nossack, Hans Erich

2004 The End: Hamburg 1943, translated by Joel Agee (Chicago: University of Chicago

Press). Der Untergang, first published as part of the collection “Interview mit dem Tode”

(“Interview with Death”) in 1948.

Anderson

•

Documents, Photography, Postmemory

1

Sachsse, Rolf

2003 Die Erziehung zum Wegsehen. Fotografie im NS-Staat (Dresden: Philo Fine Arts).

Scholz, Christian

2000 “Aber das Geschriebene ist ja kein wahres Dokument,” Neue Zürcher Zeitung 48:

51–52.

Sebald, W. G.

1989 “Überlebende als schreibende Subjekte. Jean Améry und Primo Levi, Ein Gedenken,”

Zeit und Bild: Frankfurter Rundschau am Wochenende

, January 28, ZB 3.

1996 The Emigrants, translated by Michael Hulse (New York: New Directions).

2000 Vertigo, translated by Michael Hulse (New York: New Directions).

2003 On the Natural History of Destruction, translated by Anthea Bell (New York: Random

House).

2005 Campo Santo, edited by Sven Meyer, translated by Anthea Bell (London: Penguin).

Weiss, Peter

1967 [1965] The Investigation, translated by Jon Swan and Ulu Grosbard (New York: Pocket

Books).

Wood, James

1998 “An Interview with W. G. Sebald,” in Brick 59: 23–29.

Zilliacus, Clas

1979 “Radical Naturalism: First-Person Documentary Literature,” Comparative Literature 31

(2): 97–112.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Ekrany Alexander Kluge

Mark Hebden [Inspector Pel 19] Pel and the Perfect Partner Juliet Hebden (retail) (pdf)

Mark Hebden [Inspector Pel 14] Pel and the Party Spirit (retail) (pdf)

FIDE Trainers Surveys 2011 12 Alexander Beliavsky Winning and Defending Technique in the Queen Endin

Anderson, Kevin J Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow

Mark Hebden [Inspector Pel 18] Pel Picks Up the Pieces Juliet Hebden (retail) (pdf)

Anderson Evangeline Red and the Wolf PL

Eric C Anderson Take the Money and Run, Sovereign Wealth Funds and the Demise of American Prosperit

Mark Hebden [Inspector Pel 08] Pel and the Pirates (retail) (pdf)

Anderson, Kevin J Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow

Between The Land And The Sea Derrolyn Anderson

Mark Hebden [Inspector Pel 06] Pel and the Bombers (retail) (pdf)

David Neel Alexandra With Mystics and Magicians in Tibet

Mark Paul A Tangled Web Polish Jewish Relations in Wartime Northeastern Poland and the Aftermath Pa

Mark Hebden [Inspector Pel 15] Pel and the Missing Persons (retail) (pdf)

Barth Anderson Bringweather and the Portal of Giving and Taking

Mark Hebden [Inspector Pel 09] Pel and the Prowler (retail) (pdf)

The Photographer and the Actor

więcej podobnych podstron