image038

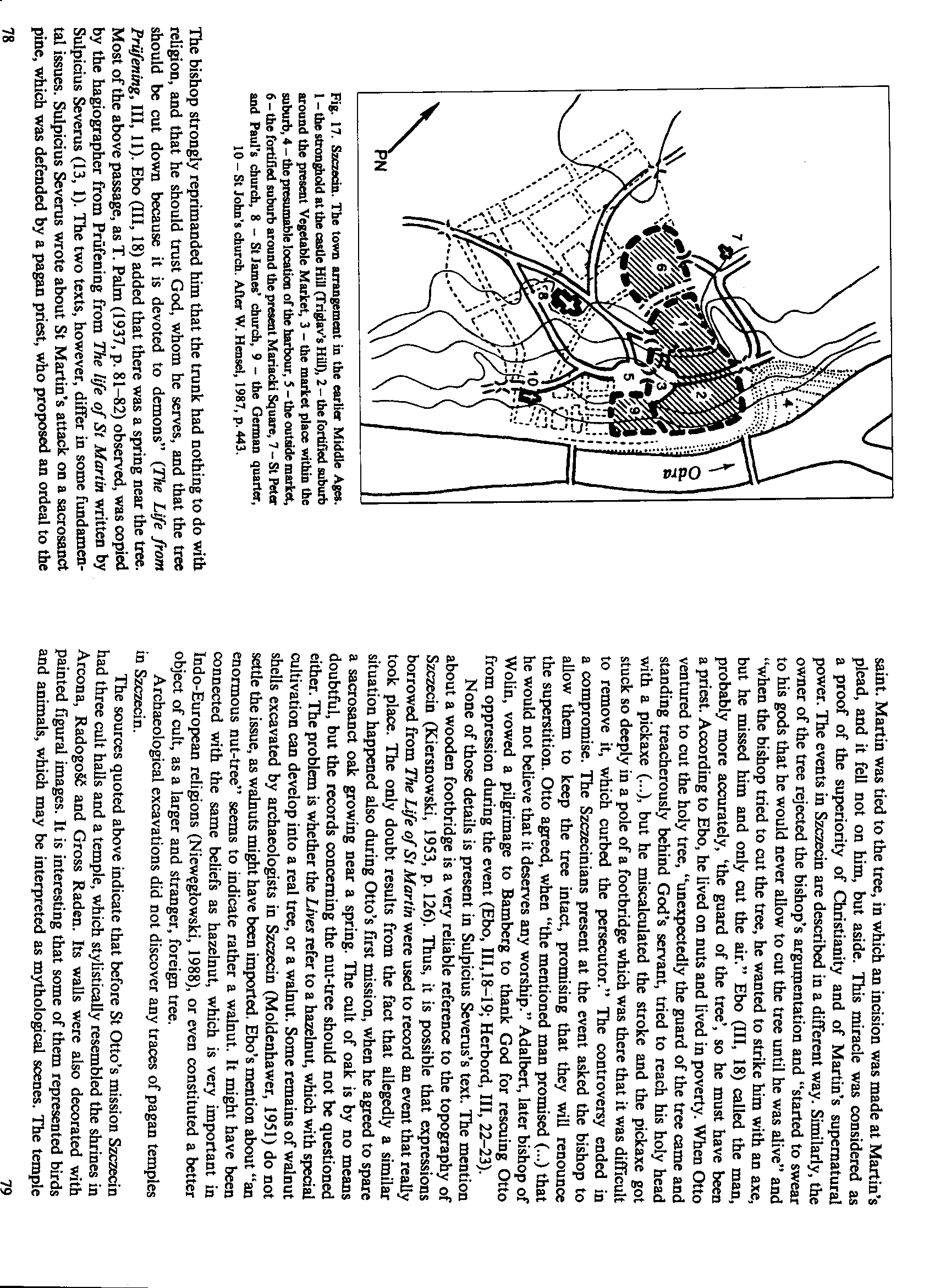

Fig. 17. Szczecin. The town arrangement in the earlier MiddJe Ages.

1 - the stronghold at the castle Hill <Trigłav’s Hill), 2 - the fortified suburb around the present Yegetable Market, 3 - the market place within the suburb, 4 - the presumable location of the harbour, 5 - the outside market,

6 - the fortiiled suburb around the present Mariacki Square, 7 - St Peter and Paul’s church, 8 - St James’ church, 9 - the German ąuarter,

10 - St John’s church. After W. Hcnsel, 1987, p. 443.

The bishop strongly reprimanded him that the trunk had nothing to do with religion, and that he should trust God, whom he serves, and that the tree should be cut down because it is devoted to demons” (The Life from Prufening, III, II). Ebo (III, 18) added that there was a spring near the tree. Most of the above passage, as T. Palm (1937, p. 81-82) observed, was copied by the hagiographer from Prufening from The life of St Martin written by Sulpicius Severus (13, I). The two texts, however, differ in some fundamen-tal issues. Sulpicius Severus wrote about St Martin’s attack on a sacrosanct pine, whićh was defended by a pagan priest, who proposed an ordeal to the saint. Martin was tied to the tree, in which an incision was madę at Martin’s plead, and it fell not on him, but aside. This miracle was considered as a proof of the superiority of Christianity and of Martin’s supematural power. The events in Szczecin are described in a different way. Similarly, the owner of the tree rejected the bishop’s argumentation and “started to swear to his gods that he would never allow to cut the tree until he was alive” and “when the bishop tried to cut the tree, he wanted to strike him with an axe, but he missed him and only cut the air.” Ebo (III, 18) called the man, probably morę accurately, ‘the guard of the tree’, so he must have been a priest. According to Ebo, he lived on nuts and Iived in poverty. When Otto yentured to cut the holy tree, “unexpectedly the guard of the tree came and standing treacherously behind God’s servant, tried to reach his holy head with a pickaxe (...), but he miscalculated the stroke and the pickaxe got stuck so deeply in a pole of a footbridge which was there that it was difficult to remove it, which curbed the persecutor.” The controversy ended in a compromise. The Szczecinians present at the event asked the bishop to allow them to keep the tree intact, promising that they will renounce the superstition. Otto agreed, when “the mentioned man promised (...) that he would not believe that it deserves any worship.” Adalbert, later bishop of Wolin, vowed a pilgrimage to Bamberg to thank God for rescuing Otto from oppression during the event (Ebo, 111,18-19; Herbord, III, 22-23).

Nonę of those details is present in Sulpicius Severus’s text. The mention about a wooden footbridge is a very reliable reference to the topography of Szczecin (Kiersnowski, 1953, p. 126). Thus, it is possible that expressions borrowed from The Life of St Martin were used to record an event that really took place. The only doubt results from the fact that allegedly a similar situation happened also during Otto’s first mission, when he agreed to spare a sacrosanct oak growing near a spring. The cult of oak is by no means doubtful, but the records conceming the nut-tree should not be ąuestioned either. The problem is whether the Lives refer to a hazelnut, which with spedal cultivation can develop into a real tree, or a walnut. Some remains of walnut shells excavated by archaeologists in Szczecin (Moldenhawer, 1951) do not settle the issue, as walnuts might have been imported. Ebo’s mention about “an enormous nut-tree” seems to indicate rather a walnut. It might have been connected with the same beliefs as hazelnut, which is very important in Indo-European religions (Niewęgłowski, 1988), or even constituted a better object of cult, as a larger and stranger, foreign tree.

Archaeological excavations did not discover any traces of pagan temples in Szczecin.

The sources ąuoted above indicate that before St Otto’s mission Szczecin had three cult halls and a tempie, which stylistically resembled the shrines in Arcona, Radogość and Gross Raden. Its walls were also decorated with painted figural images. It is interesting that some of them represented birds and animals, which may be interpreted as mythological scenes. The tempie

79

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

image065 Fig. 52. Płock. The alleged pagan sanctuary, excavation site 3 (in Ihe abbey yard), layer V

image043 Fig. 20, Wolin. The second tempie. A - the tempie, B - the yard, C - the stable, D - the pa

image067 Fig. 53. Kiev. A town plan. The early medieval objects marked against the contemporary arra

S5003157 Fig. 1 Stara Słupia smelting site. The remains consist f " arranged in parallel rows w

S5003156 170 Fig. i Stara Słupia sneltlng site. The remains consist of slag pits arranged in paralle

Przegląd Geologiczny, vol. 55, nr 12/1, 2007 Fig. 17. “Bamówko-Mostno-Buszewo” (BMB) oil-gas field i

S5003156 170 Fig. i Stara Słupia sneltlng site. The remains consist of slag pits arranged in paralle

essent?rving?14 pp Essential Woodcarvixg Techniques W Fig 1.17 Ttoo grounders. Very narrow old Engli

essent?rving?15 Fig 10.16 The smali beech bowl being held in a caruers chops with a bar across its m

image008 Fig. 4. Possible reconstructions of the tempie in Old Uppsala, drawings based cm: A.-C. Sch

image023 Fig. 15. Korzenica-Garz. I, II, m - the alleged traces of temples in the stronghold; after

image042 Fig. 18. The topography of the early-raedjevaj Wolin. A - the presumed location of the temp

image047 Fig. 22. The location of the stronghold in Gross Raden. 1 - the stronghold in Gross Grónow;

image048 Fig. 24. Gross Raden. A graphic reconstruction of the settlement in phase A (9th century);

image049 1 m Fig. 26. The profile and plan of the remains of Ihe south-ea&tem wali base of the t

image055 Fig. 39. Starigard (Oldenburg). The sanctuary erected after the destruction of the church i

image063 Fig. 47. Trzebiatów. A plan of the town and its surroundings. A - the cult place on David H

więcej podobnych podstron