Reframing resistance to change: experience

from General Motors Poland

Dorota Dobosz-Bourne and A. D. Jankowicz

Abstract

This paper describes the successful introduction of a kaizen scheme in a

General Motors factory plant in Gliwice, Poland. Employee value systems changed,

despite the presence of strong, pre-existing values that might have inhibited this process.

These findings are drawn on to examine the concept of ‘resistance to change’ and replace it

with a notion of ‘functional persistence’. Our case study illustrates how assuming this

position can aid the development of new work attitudes, as opposed to constraining the old

ones.

Keywords

Resistance to change; knowledge transfer; post-command economy; personal

values.

A background to work attitudes in Poland

Until 1989, Poland operated as a command economy that had its goals politically

determined by the monopoly of a national communist party taking many of its priorities

from Moscow (Kostera, 1996). In an economy of shortage with overwhelming customer

demand, industrial production aimed at maximizing supply within a centrally controlled

system that discouraged consideration of standards and quality at the point of

production/service delivery (Dobosz and Jankowicz, 2002). Closed borders and the

central allocation of production goals and resources eliminated competition from outside

of the Soviet bloc. Consequently management functions such as quality management, cost

control and marketing, were underdeveloped in the Polish economy (Kozminski, 1993).

The political nature of command economy operations strongly influenced the

development of Polish employees and managers during the communist years. Career

progression was severely limited for the 25 per cent of managers who, by the end of the

command period, were not members of the Nomenclatura list of previously vetted

members of the Polish United Workers’ Party (Szalkowski and Jankowicz, 2004).

Managers learned to avoid responsibility and risk, and developed networking and

political influence skills (Jankowicz, 2001; Obloj, and Kostera, 1994). However, this led

to conflict between people from different levels within the organizational hierarchy. As

the managerial role was largely conditional on party membership, Polish managers were

perceived as representatives of the system and its regime. This led to antagonism

between the workers and managers, and ‘them versus us’ behaviours emerged (Kostera,

1996). Mistrust of the system and a growing willingness to beat it were additionally

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

ISSN 0958-5192 print/ISSN 1466-4399 online q 2006 Taylor & Francis

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

DOI: 10.1080/09585190600965431

Dorota Dobosz-Bourne, Lecturer, School of Business and Management, Queen Mary, University of

London, London E1 4NS, UK (e-mail: d.dobosz-bourne@qmul.ac.uk); A. D. Jankowicz, Professor

of Constructivist Managerial Psychology, Luton Business School, University of Luton, Park

Square, Luton LU1 3JU, UK (e-mail: Devi.jankowicz@luton.ac.uk).

Int. J. of Human Resource Management 17:12 December 2006 2021 – 2034

reinforced by resentment, passivity and a mistrust of authority, values characteristic of

the Soviet style of management and its outcomes (Zaleska, 1998). Tischner (1992: 161,

present authors‘ translation) describes this attitude well: ‘Homo Sovieticus: chronically

suspicious, full of sour demands, unable to take responsibility or to commit himself, ever

ready to wallow in his own misery and misfortune.’

Prior to the explicit revolts of the 1980s, covert rebellion against the regime

demonstrated itself in Polish enterprises as a lack of discipline, commitment and orderly

progress – a rebellion, somewhat paradoxically, reinforced by government policy on

unemployment reduction and the fact that, under communism, the government

guaranteed everyone a job (Bednarzik, 1990).

Despite the government efforts to create an illusion of economic prosperity and social

equality in the Soviet bloc, Polish people inevitably compared the economic

achievements of the command economy with those of the West.

The constant close contact with other cultures, historically imposed, results in ambiguous

attitudes: for example, an admiration of Prussian efficiency clashes with the fact that for many

years, sabotage and not efficient work was a patriotic virtue ... Looking at other countries, Poles

tend to attribute their successes to what is lacking in the ‘Polish character’: order, efficiency,

method. Therefore, the system is a myth. (Czarniawska, 1986: 15)

Comparing themselves with the West, the Poles developed a perception that a free

market economy was a foolproof recipe for a prosperous and luxurious existence so

the enthusiasm and hope for dramatic change which exploded in the country after the

collapse of communism in 1989 was understandable. Poland wanted to transform its

economy into a free market and effectively catch up with the West (Kozminski, 1993).

An approach to the identification of values in multicultural cooperation

The changes of the 1990s and expansion of the European Union created numerous

possibilities for cooperation between Western and Eastern Europe. The emerging

markets attracted the attention of foreign investors, General Motors among them.

Clearly, the arrival of multinational companies would not always lead to a smooth

implementation of Western managerial practices and their subsequent economic success,

since the interaction between local workforce and foreign investors was inevitably going

to be affected by the cultural differences between the two groups. The values brought to

any multicultural collaboration by both sides determine the outcome of this process since

they govern action (Balnaves and Caputi, 1993) and the choices between more and less

preferred action that lead to institutionalization (Czarniawska and Joerges, 1996). Thus a

consideration of relevant values in the cultures involved in international cooperation, and

the extent to which these values differ as a function of the ‘cultural distance’ (Barkema

et al., 1996) between the cooperating organizations, is especially important for the

successful implementation of new management ideas.

In research on managerial values, particular values have traditionally been represented

as points or locations along a number of cultural dimensions, as identified by such

authors as Hofstede (1991) and Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1997). While this

approach to the study of values specifies value dimensions as a helpful first

approximation, it does not necessarily indicate the consequences for behaviour. This

broad-brush approach creates a generalist definition of values at the societal level

(Gesteland, 1999 exemplifies the insights possible) that does not, however, necessarily

reflect the particular personal values held by the individuals involved. In-depth

understanding at the personal level is important – Jankowicz (1996) provides instances

2022

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

of the way in which similar behaviour in different cultures may stem from different

values, and vice-versa: differing behavioural consequences drawn from similar personal

values. Therefore, in this paper we use a particular combination of qualitative and

quantitative research techniques (Kiessling and Harvey, 2005) to identify values at both

social and individual level.

If it is the case that sociologists have neglected the impact of individual differences

on the social phenomena being observed, (Schein, 1996) while psychologists have

ignored the traditions of sociologists and anthropologists, who observe a phenomenon at

length and in depth before trying to understand it, it would appear important to use

techniques that focus on individual perspectives in depth without trivializing them. In

the present study, the repertory grid technique (Kelly, 1955) provides the former, while

extended observation and ethnographic interviews conducted in situ provide the latter,

the two together resulting in a richer and more precise picture than a more generalist

dimension-based approach to cultural values might offer. Kelly’s technique focuses on

constructs rather than concepts, a construct being a distinction that a person makes in

order to make sense of an issue. Importantly for our purposes constructs are always

expressed in the form of contrasts – in identifying our respondents’ priorities, we were

able to examine what each person values, but also, what s/he choose not to value by

behaving in a particular way (Fransella, 1995: 57 – 8). The combination of the two

approaches works well: unthreatening in its approach, the ethnographic interview builds

an atmosphere of mutual interest, affinity and closeness without excessive intrusion into

the interviewee’s privacy, preparing the way for an in-depth grid-based assessment of

personal values that many people might otherwise feel threatened by without such

preparation.

The ethnographic interview has a long tradition in knowledge transfer research

(Rogers, 1995) but the repertory grid may need some further description at this point. We

used it in three stages. In the first, interviewees’ personal constructs were elicited by

asking each person to focus on, and recognize important similarities in and differences

between, critical incidents (Flanagan, 1954) in their working life. Examples of such

constructs might be: ‘This incident was exciting and challenging, whereas in contrast,

these were dull, a matter of practicing standard operating procedures’; or ‘These

incidents were due to the expatriate managers’ misunderstanding of local custom and

practice, while these, in contrast, were due to the Polish employees’ misunderstanding of

the intentions behind the changes being introduced.’

In the second stage, each interviewee was asked to indicate the personal value

underlying each construct, by an iterative process (‘laddering’) that seeks to identify the

reasons underlying the preference choices implicit in each construct. (Thus, a construct

‘Conscientious timekeeping, (as opposed to) Constant late attendance at work’ might

result in a value ‘Order (as opposed to) Chaos’ given that, for this interviewee, being a

conscientious timekeeper is about being reliable; reliability is important because with it,

one can predict and keep track of events; and prediction is important because, without

it, Order dissolves into Chaos.)

Finally, for each interviewee, each item in the set of personal values derived in this

way was compared in a forced-choice technique to result in a prioritized list of personally

more central, and less central, core values. Jankowicz (2003) describes these and related

techniques in detail.

The empirical work was carried out in two divisions of General Motors, the Vauxhall

Luton plant in England and the Opel Polska plant in Gliwice, Poland. The ethnographic

interviews, followed by the three-step repertory grid process outlined above, were done

with 30 managers as key informants (Tremblay, 1982), 16 British, two German, and 12

Dobosz-Bourne and Jankowicz: Reframing resistance to change

2023

Polish, these last having been trained by the English ones. All were chosen because of

their direct and extensive involvement in the process of knowledge transfer from

England to Poland when the Opel Polska plant was set up on a greenfield site in 1996.

The individual grid information was used to supplement and amplify the individual

ethnographic account as outlined above; additionally, all constructs were pooled to

provide an aggregated picture of the constructs and values among all 30 interviewees.

This was done by a content analysis of the 211 constructs obtained from all 30

interviewees, using a boot-strapping procedure (Honey, 1979; Jankowicz, 2003) in which

an acceptably high researcher reliability was achieved. Categorization and coding by two

researchers working independently gave a final result of 79 per cent agreement, Cohen’s

kappa for this analysis being 0.77, with a high and stable Perrault – Leigh reliability index

of 0.86, (the 0.5 per cent confidence interval on the latter being 0.024). Personal values

were aggregated using a similar procedure.

Giving a meaning to kaizen in Opel Polska

In developing the greenfield site at Gliwice, General Motors followed their normal

practice of using the original Japanese terms (kaizen, andon and gemba) for the quality

development and improvement procedures which, together with TQM practices,

suggestion schemes, policy deployment procedures, some localized problem-solving

techniques (Nowak, 2005) and general procedural standardization across the whole plant,

made up their integrated approach to vehicle assembly. Kaizen may be based on an

incremental paradigm (Proctor et al., 2004), but General Motors used the Japanese term

rather than some Polish translation, as a blunt and deliberate signal that new ways of

thinking were required. More subtly, the lack of pre-existing associations to the initially

meaningless foreign term provided a clear field in which new and more desirable

associations might be formed – a clean slate, as it were.

Several stages, involving three distinct groups of people, were involved in the

elaboration of meaning that followed. We draw on the ethnography first before drawing

on the repertory grid findings on values.

One group consisted mainly of British managers, all with previous experience from

Toyota or Nissan in Japan and the UK, responsible for starting up the plant and

introducing kaizen to Poland. The second consisted of Polish supervisors selected

according to general ability and an openness to new concepts, with an average age of 28.

Most had no prior experience of vehicle manufacturing or assembly but had the

potential to take over the English managers’ responsibilities during the following

three years, (and by and large did). A third group was created to serve as translators,

both literally, until the first two groups developed facility in each other’s language but,

more importantly, as translators of the new ideas brought onto Polish ground by the

English managers; a translation process involving the negotiation of mutually

comprehensible meaning that made sense in a local cultural context but introduced new

cultural values (see, e.g., Latour, 1986; Rogers, 1995; and the discussion in Dobosz and

Jankowicz, 2002). These three groups of people were to see themselves as ‘the creators’

of Opel Polska. For the Polish participants in particular, this made for a feeling of

ownership quite unique among the sunset industries of the region (mainly coal and steel)

with their traditional, authoritative/authoritarian Polish style of management

(Jankowicz, 1994; Maczynski, 1994).

Selected from a pool of 46,000 applicants, the general workforce of 1,800 was chosen

for similar attributes: young, relatively inexperienced, willing to learn and energetic

enough to perform repetitive tasks for long periods of time while maintaining good

2024

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

quality standards. The lack of experience was perceived as an advantage for a candidate,

since GM managers considered working experience in the Polish car industry as

undesirable due to the poor production and management standards of the past, and the

danger of importing ‘bad habits’ that might be incompatible with General Motors’ vision

of quality assembly work. What was looked for was, as far as possible, a tabula rasa to be

enscribed and developed by intense training and guided experience in the run-up to the

start of production.

A phase in which the theory of kaizen, andon and gemba was outlined and the values

underlying them articulated was followed by training in generic, transferable skills

related to job families (e.g. the handling and integrating of elements of standardized work,

together with a set of associated problem-solving techniques). On-the-job training

followed, supported by hands-on supervision by the expatriate managers. Visits were

organized to other GM plants. While the training content was focused on the development

of specific technical skills, one of the earliest attitudinal lessons for the Polish employees

was that the commitment to quality values was more than the token sloganizing their

parents’ generation had experienced on the shopfloors of the command economy. The

message was conveyed in such an intense way that it was initially viewed as excessive and

exaggerated, by the general employees to be sure, but by their Polish supervisors as well.

So, an example from the training phase: the basic training about quality, what it is, what it gives,

its measurable benefits, and ways of assessing and reporting it. It’s safe to say that all the

reporting requirements were met with utter distaste, That, yet again, to the limits of endurance,

one was required to take everything apart in fine detail because that’s the rule, that’s the

standard, and there’s no avoiding it. Having said that, this attitude eventually got into people’s

blood. (Polish Manager 1, Opel Polska)

The change objectives were clear, and the difficulties of introducing new ways of

thinking were not underestimated. Fortunately, the English managers had prior

experience of start-ups to draw on; (see also Wickens, 1987).

We decided to take things from Japan based on what would fit in with the local community of the

North East of England. And the similar type of thing, here, how it would fit in with a local, Polish

culture. But that’s not, to say, well, the culture would necessarily accept this. Because we have

to say, we might break the culture of the local area. And we do things differently, because we

have to do it, to avoid a clash of standards. We have to bring the best ideas and working practices

to the business and if that doesn’t quite fit in to the Polish culture, then we have to furnish a new

culture. (English Manager 1, Nissan UK, GME, Opel Polska)

The development of working practices at the level of individual behaviour was

coupled with an effort to create and shape culture at the broadest, plant-wide level, using

techniques and rituals to identify and support desirable general behaviour such as

attendance, punctuality, timekeeping, open communication and team-work. For this to

happen, change on a deeper level of personal values was required – in Kelman’s terms, a

matter of internalization rather than identification with supervisors, or mere compliance

as a function of behavioural sanctions (Kelman, 1958, 1970) – together with changes in

the fabric of day-to-day experience.

I’m particularly impressed by their [foreign managers’] systematic approach to their job. That

they really can think, react, divide and connect, analyse and partition, allocate work, collect

results and come to conclusions, all in a deliberate and measured way. Sure, it reflects an

enormously well developed training background; at the same time, those people really must

believe in what they’re doing, otherwise they couldn’t possibly keep it up on a day-by-day basis.

That’s what we lacked in the old days. (Polish Manager 1, Opel Polska)

Dobosz-Bourne and Jankowicz: Reframing resistance to change

2025

New ideas were introduced as clusters which need to coexist in order to be

successfully implemented. And so, the idea of kaizen was identified with the broader

issue of the careful organization of ones’ general creative efforts. Work uniforms were

reconstrued as symbols of single status and a resultant team spirit, rather than as the

military-style clothing designed to lower ones’ status, as they had been originally viewed

when first introduced. Individual responsibility, a trait that had been underdeveloped and

discouraged in the command economy (Kostera, 1995; Kozminski, 1993; Krysakowska-

Budny and Jankowicz, 1991; Lee, 1995), was encouraged through the creation of a

no-blame culture, performance related pay and TQM technique. It became clear that the

adoption of any single idea depended on the implementation of the remaining ideas from

its particular cluster at a more general, organizational and societal level.

Polish managers and employees had grown up in a recent culture in which the

legitimacy of power, its ownership and opposition, had been debated with considerable

sophistication at all levels of education and society (see, e.g., Czarniawska, 1986;

Milosz, 1981). The choice of symbol and the metaphors it embodied mattered. And so, it

is important to note that each cluster of previously unknown ideas was carefully planned

prior to introduction, with careful discussion of its meaning between the English and

Polish staff, a discussion in which, in the early stages, the role of the ‘translator’ staff was

crucial. This resulted in the need to adapt General Motors practices to the specifics of

Polish culture. For example, the introduction of a single-status canteen was all very well,

just one of the new practices whose function in expressing equality was straightforward;

but the nature of the menu was something else again.

There was a problem with the canteen and the food. The foreigners couldn’t understand why

there could be no meat on Fridays. And we had to explain to them that Poland is a Catholic

country, and we would rather not eat meat on Fridays ... But for them it was a complete novelty

and we had to convince them; eventually they got it.’ (Polish Manager 2, Opel Polska)

This was not a matter of providing alternatives, as one provides a ‘vegetarian option’

in the West; nor were the employees necessarily devout in their Catholicism. In this

culture, one simply did not serve meat on a Friday and that was that. Other practices

required substantial change and adjustment on the Polish side

For many people, it was just inconceivable that it was possible to collect sick absence records,

what their illness was, and when they’re due back ... But they accepted it, and I get the feeling

that the most important thing was that people realized the importance of being at work. If they

don’t turn up, we won’t produce any cars, so nobody will buy them, so we may as well shut

up shop and take a vacation. And they understand that. It seems to me that the most important

thing is that they realized the importance of their role, how crucial it is in all of this. (Polish

Manager 2, Opel Polska)

The point here being that absenteeism had been widely accepted in the old working

culture. Taking sick leave for trivial reasons, with a doctor’s certificate often obtained

illegally, was common practice for many employees, and systematic investigation

viewed as an unwarranted intrusion into one’s private life. Changing this attitude

required careful attention. As mentioned above, linking absenteeism with poor

production results was one of the strategies. Additionally, performance related pay and a

small prize for employees with model work attendance were introduced as incentives.

One might multiply examples of this kind of cultural negotiation over meanings as the

changes were effected but, to appreciate the processes and dynamics involved, it is

necessary to examine the enduring Polish values and orientation to change – a matter of

2026

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

500 years of history rather than 50 years of command economy or two years of the

General Motors’ change intervention.

The reception of these ideas in the Polish experience

The successful introduction of procedures that marry creativity with organization has

often been problematic for Poland in the past, both historically and in the more recent

times of the command economy.

The institution of the Liberum Veto (a requirement that all parliamentary Acts be

passed unanimously) was first introduced in 1652 and used extensively until 1764 prior to

its replacement by majority voting in 1791 just four years before the final partition of

Poland. This concept of consensus rule was principled and creative in its time, but was

fatally vulnerable to misuse by local factions and external powers alike, and, taken

together with the institution of a monarchy elected since 1370 (a principled and creative

approach to some of the problems associated with primogeniture) contributed to a state of

anarchy from the mid-seventeenth century onwards (Davies, 2005; Kasprzyk, n.d.). The

communist years left Poland with a cultural heritage in which organization and discipline

were not recognized as important by the average worker. Combined with a tradition of

sabotage and mistrust in the communist system, these attitudes made attempts to

introduce a systematic approach to work very difficult under the command economy (see

esp. Roney, 1997). Consequently, the issue of order versus anarchy, and the articulation

of an appropriate balance in the form of personal values, have been problematic in Polish

culture for many generations.

The following comment taken from one of the early training visits concerns the

practices of organization and discipline in the German Opel plant, and is a good reflection

of the possible interpretation of such practices by the average Pole.

They all work homogenously so that their progress has added value. And this is what I liked

there. The approach to their duties involves reliability but without exaggeration in diligence. If

anyone ever tells me that Germans are hard-working, I will ridicule them. They are merely

systematic to the verge of idiocy, to the averagely imaginative Pole. You might say they are sad

drones at work. All they do at work is work, nothing else!’ (Polish Manager 1, Opel Polska)

Turning to the repertory grid results, it is noticeable that the value for Order, Control

and Direction – as distinct from Freedom of Spirit – is among the top four most

frequently mentioned by the Polish interviewees: see Table 1.

Equally, it is clear that the reason that this value is placed as the most frequent is that it

was particularly important to the English managers as well as the Poles; moreover, three

other values were as important to the Poles: Self-actualization, Progress, and Being

esteemed and respected. But the issue is crucial.

Historically, Poles like to see themselves as people with a free spirit and a great sense

of style (see Hoffman, 1989). The Polish word ‘fantazja’ standing for ‘imaginativeness’

identifies a trait which is greatly valued in Polish culture (Dyczewski, 2002) and

literature, (e.g. Gombrowicz, 2003; Slowacki, 2004; Zeromski, 2001) since it provides an

outlet for individual creativity. Significantly, it is diametrically opposed to the notion of

being systematic and well organized, traits traditionally considered as boring and

unnecessary; the contrast appeared frequently among the constructs elicited in the

repertory grid. But it means more than that. There are also connotations of being

independent, free of subjugation, as distinct from being obedient to standard operating

procedures. In a self-paced working environment, issues of self-discipline are raised.

‘Poles see no harm in a little disorder. To them lines and queues stand for regimentation

Dobosz-Bourne and Jankowicz: Reframing resistance to change

2027

and blind authority. I once saw a Pole crash a cafeteria line just to “stir up those sheep”’

(Hall, 1966: 128).

Although fantazja can be beneficial in the process of continuous improvement where

creativity is important, other characteristics, such as the Polish tendency to be disorganized,

and the chaotic approach to work, might prove devastating. Shaping a group of young,

energetic Polish employees who value fantazja into a team engaged in continuous

improvement in a systematic way might seem impossible, particularly when one considers

the full constructs (the meaning being asserted and the meaning being contrasted) involved,

together with the values that underlie them. Kaizen requires discipline and organization if

one is to reap the benefits in creative work improvement. Attributes which seem to be

opposed in the Polish employees’ psyche need to co-exist. How might this be achieved?

The second-most frequently mentioned personal value indicates a possible way forward.

The relative frequency of this value confirms that the GM culture at Gliwice was driven by

a vision of progress shared by both Western and Polish managers. Both groups involved in

the knowledge transfer were thereby open to change, the Western managers because it was

their responsibility to bring it about, and the Poles because they had been selected for their

willingness to learn and their openness to personal change. Now, the concept of ‘progress’

overlaps considerably in English and Polish (Jankowicz, 2004). Both languages encode the

same two distinct aspects of development inherent in the notion of ‘progress’: development

as initiation, and development as onward movement. (For example, to ‘develop a project’

can mean ‘to start a project’ or ‘to make ongoing improvements in the project’.) And

(remembering that the full meaning of a construct is conveyed by taking its contrast into

account), the same two contrasts are made in English and Polish: development versus stasis

(zastoj) and development versus stagnation (stagnacja); the concepts are linguistically

isomorphic. For our Polish respondents, it was the latter aspect that was at stake, for kaizen

is precisely about onward improvement; and stagnation, in turn, was described by some of

these respondents as something that lacks fantazja.

The remaining categories in the top five that between them make up almost 75 per cent

of the values mentioned relate to the Maslovian needs of self-actualization, esteem and

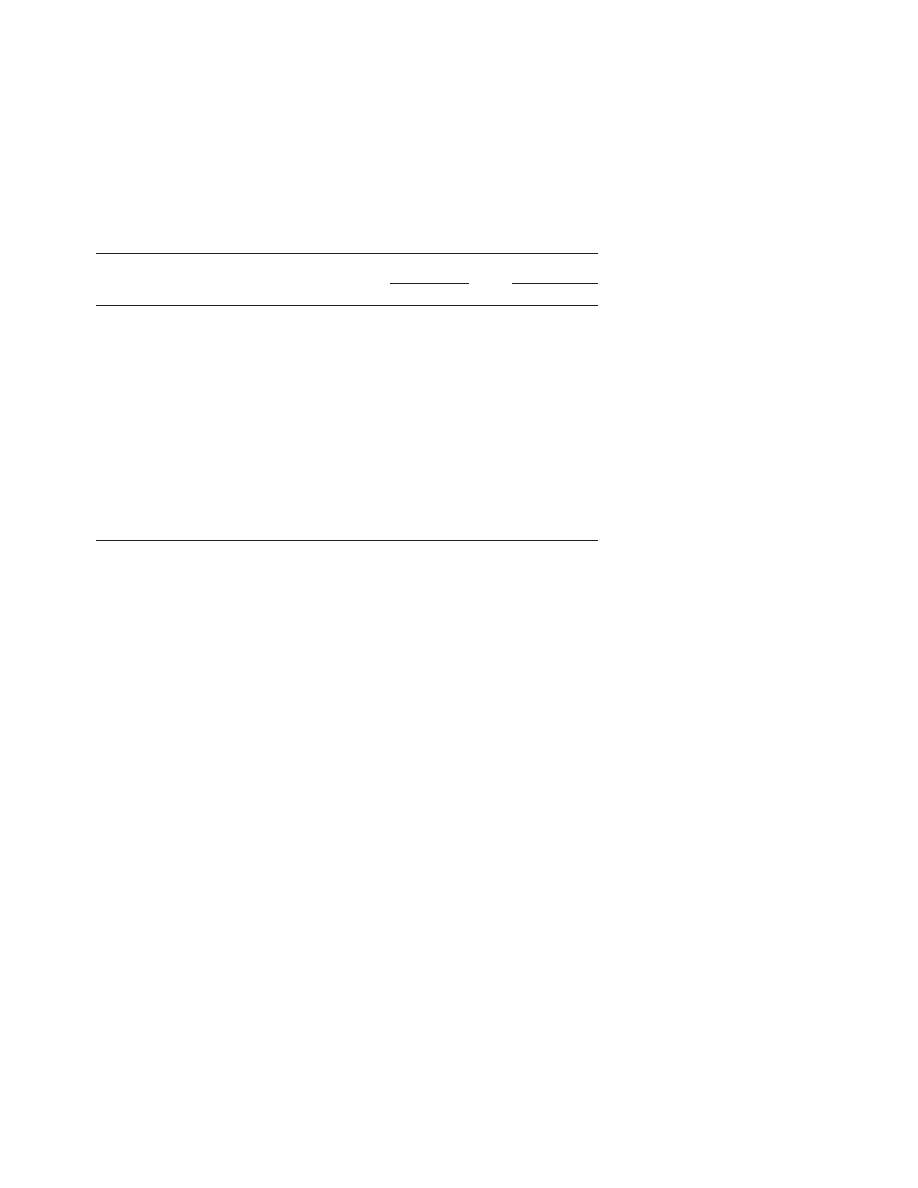

Table 1 Content-analysed values for 28 UK and Polish managers

No.

Personal value

Total

UK managers

Polish managers

n

%

n

%

1

Order, control and direction:

versus freedom of spirit

24

17

29.3

7

19.4

2

Self-actualization

15

9

15.5

6

16.7

3

Progress

15

8

13.8

7

19.4

4

Being esteemed and respected

10

3

5.2

7

19.4

5

Relationships

9

5

8.6

4

11.1

6

Satisfaction/contentment

5

5

8.6

0

0

7

Pride

4

4

6.9

0

0

8

Good world/peace

4

2

3.4

2

5.6

9

Security

3

2

3.4

1

2.8

10

Optimism

2

1

1.7

1

2.8

11

Sharing

1

1

1.7

0

0

12

Meaningfulness

1

1

1.7

0

0

13

Patriotism

1

0

0

1

2.8

Total

94

58

99.8

36

100.0

2028

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

social interaction. The overall picture created by all five might be interpreted as a concern

for development but not at all costs. Perhaps the readiness of Poles to accept change

easily stems from the need for self-actualization rather than order and control.

All these people working here realize that one has to produce goods to the highest standard, the

highest quality. And that’s for several reasons. One very relevant factor, quite apart from

the awareness that goods which aren’t of high quality wouldn’t sell, seems to be that here we

have a factor which is fundamentally Polish, and that’s a factor which I would characterize as

aspiration ... Young people have this about them; they’re ambitious. In contrast to older people

who come to work to earn money, younger people are engaged, somehow, and want to be told,

well, yes, it’s you who are building this car. You can tell that from the way they keep taking

photographs of themselves with the cars, they’re identifying themselves with it. (Polish Manager

1, Opel Polska)

Both the ethnography and the repertory grid data indicate that, for the Polish staff in

particular, the value of progress was closely related to learning, risk taking and challenge.

Within the GM quality system, these values gained behavioural expression through

carefully and explicitly planned tasks and procedures designed to be monitored and

measured. While this involved order and control, it was clear to the Polish employees that

these procedures made for freedom of spirit because they represented an effective and

flexible use of their time, and the Polish sample came to accept the relationship between

the two as meaningful. It was the time management training provided as part of the

generic skills training phase (see above) that created the possibility of self-managed

choice over how one is to partition one’s time within the constraints of the production

requirements: ‘People do things that are more work for them; it’s more difficult for them

but they understand the importance of doing it’. (English Manager 2, Nissan UK,

Vauxhall Luton, Opel Polska)

Commercial and production indicators show that the start-up of the General Motors

plant at Gliwice was a success. During 2000, for example, the plant recorded the best

quality and performance figures of all GM plants worldwide. It would appear that the

introduction and implementation of new managerial practices, and the development of a

culture of continuous improvement in Opel Polska, played a large part. In learning new

ways of construing, the Polish employees successfully managed the tension between

progress/freedom, and organization/planning.

In one sense, kaizen, andon, gemba and the suggestion scheme might be seen as a

safety-valve: as a ‘vent’ or outlet for the imagination and creativity that make up the

Polish notion of fantazja. Of course, the employees’ suggestions for improvement could

only be put into effect by being systematized as part of the quality procedures in an

organized and planned manner – only those ideas that could be systematized and tested

could be realized. In this way, General Motors linked creativity with order, and

introduced this combination as a financially rewarding practice (employees being

remunerated for successful ideas) as part of a quality system to which, since it became a

required working procedure, there was no alternative. This not only encouraged people

to implement new practices, but also provided the only way to achieve good results and

rewards.

The language of ‘resistance to change’

How might one conceptualize this account? The conventional way would be to see the

experience at Opel Polska as an instance of resistance to change, successfully handled.

The Western managers acted as change agents engaged in a necessary and inevitable

Dobosz-Bourne and Jankowicz: Reframing resistance to change

2029

conflict with the Polish managers and employees who had a position to defend; but the

outcomes were positive, since the resistance was overcome. This kind of analysis

obscures more than it illuminates, however. Typically, it places the change agent on the

side of the angels, and the people being changed as mulish and obstinate, resisting

innovations that have proved successful elsewhere. (And sometimes, it neglects the

possibility of incompetence: that change agents have misunderstood the situation, or

simply that they are not very good trainers.) Rather more seriously, though, the military

metaphor, with its images of conceptual and procedural invasion, forceful attack on

entrenched positions, and the final breakthrough when those positions are abandoned and

all opposition is overcome, trivializes the processes involved.

This is because, although the approach does make some concession to the notion that

existing positions may have value to the people being changed, it tends to be couched in

terms that discourage any detailed examination of the functionality of those positions;

nor does it encourage negotiation and debate over the values themselves. The concept of

resistance to change as taught in the basic management texts (see, e.g., Hellriegel et al.,

1995: 662) seems always to express each of the reasons for resistance in negative terms.

To take just three examples: Existing perceptions are discussed in terms of ‘the

perceptual error of perceptual defence’ without taking into account that it is the change

agent, rather than objective circumstances in the phenomenal flow of events, that sets the

terms of reference as to what is or is not accurate perception. In citing Personality as a

factor (and, quite rightly, cautioning the reader against over-emphasizing its importance),

it is nevertheless just the negative traits such as ‘dogmatism ... dependency ... low self-

esteem’ that are quoted. In discussing the role of existing habits as a source of resistance,

it is the negative factors such as the need for comfort and security that are cited.

Yet one could easily conceptualize the role of existing perceptions in terms of

cognitive mechanisms, leaving the issue of perceptual ‘error’ as an open one. One really

should use the full, professional personality trait labels (liberalism versus dogmatism,

self-sufficiency versus dependency, low self-esteem versus high self-esteem), instead

of automatically assuming that a position of resistance is necessarily based on the

negatively evaluated characteristic. And one might discuss habit in terms of well-

practiced coping skills or of the need for a measure of predictability in one’s daily

experience, rather than as some kind of self-protective search for security. (See

Jankowicz, 1996 for a fuller account.)

Now, there is no doubt that GM possessed powerful sanctions – the ability to provide or

withhold labour in a region where one in four adults were unemployed (GUS, 1998), and in

effect, used them in selecting a biddable workforce that saw the arrival of General Motors

as a chance to create something significantly different from the past, an open-minded

approach that enabled them to redefine their role in post-communist industry where being

members of the secondary world economy was not an acceptable option. Nevertheless, it

is clear from the foregoing that there was still an issue of disparate perspectives, and strong

disagreements between the westerners and the indigenous employees.

Notice how these were resolved: not through conflict, but through the negotiation of

mutually sensible meanings. After recruitment, the threat of termination of employment

was not used, as an account based solely on power differentials might suggest. The new

practices were introduced through careful and delicate discussion between foreign

managers and Polish staff before the introduction of the new practices and the

implementation of a system of sanctions. The usefulness of the values brought to Poland

was first presented, discussed and negotiated with Polish employees, and only then

implemented in the plant, creating a field in which agreement might be possible. New

values, embedded in Western ideas, proved to be meaningful replacements for some of

2030

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

the values that characterized Polish car assembly in the past but only because, as

Alexashin and Blenkinsopp (2005), and Gilbert and Gorlenko (1999) have emphasized, a

transfer of Western managerial values succeeds only in proportion to the effort made to

understand and articulate the new with the existing cultural values, particularly the

disparate ones.

As Roney (2000) has suggested in describing the introduction of TQM into newly

privatized Polish companies, quality systems of this kind are imprinted with values and

assumptions that need to be shared by both parties if transfer is to be successful. Where

this is not the case, clashes are best addressed by promoting selected, pre-existing values

that are consistent with the new, in order to adjust to the local context (Roney, 1997: 4);

and our own account above has provided several instances.

However, we have also shown that it is possible to promote values that are

inconsistent with local norms provided they are introduced skilfully. Employees can

accept a new practice if it is argued to provide a better alternative, not to an existing

practice per se, (which might bring new and old values into contention) but by

responding to an appeal to existing values of what is ‘better’. The point is not to change

all the values, for that is impossible, but to find a fit between the old and the new within

the existing matrix of ideas, norm, values and institutions.

It may be more useful to replace the terminology of ‘resistance to change’ with the

notion of ‘functional persistence’, as Fransella (1995) has suggested. We have shown

how change can be introduced by building on values that local people were persisting

with, namely, the values of creativity and freedom. The reluctance of Polish employees

to adopt certain practices such as organization, planning and self-discipline, despite

being destructive and unreasonable from the outsider’s viewpoint, was a rational choice

for them in protecting their sense of freedom and their need for creative expression. What

was required was a demonstration that personal and organizational success (the enduring

and persistent good that sets the criterion for what might be ‘better’) could be achieved

by avoiding a simple contrast between organization and planning on the one hand, and

self-expression and freedom on the other. The way in which these constructs were

articulated could be elaborated (Kelly, 1955). Organization might be contrasted with

chaos, self-expression with stasis. It might indeed be possible to achieve personal

and organizational success by combining organization and self-expression. In fact, a set

of organized procedures might be constructed that make self-expression possible: kaizen,

andon and gemba.

As demonstrated in this paper the success of an intervention that changed values

depended on the development of a fit between existing values and new ones within an

existing matrix of ideas, norms, values and institutions. In the case of Opel Polska, that

was a matter of interpreting the changes as congruent with pre-existing Polish cultural

standards of the good. At a time when Polish culture is engaged in a redefinition of its

relationships with other cultures, and a re-exploration of its west-European identity

(Mikulowski-Pomorski, 1991, 1993), the level of resolution at which the desirability of

change at Opel Polska is determined becomes a matter of importance: do we choose the

region, Poland as a whole, Europe, or indeed the global community as the ‘wider society’

within which judgements of authenticity are to be made?

The example of the introduction of kaizen, along with organization and self-discipline

in Opel Polska, shows that basic constructs and values, although being very difficult and

resistant to change, can be changed if an alternative for their elaboration is provided.

Therefore, the new idea must be considered in terms of its usefulness in replacing an

existing idea in accordance with the recipients’ criteria. The whole process should be

Dobosz-Bourne and Jankowicz: Reframing resistance to change

2031

focused on the negotiation over meaning leading to the elaboration of constructs that both

parties could use.

This issue might be examined further in the context of the debate on globalization,

Amin (1997) and Holden (2002) being particularly useful here. For the individual

manager working to bring about change, the most useful way of resolving the matter

of where the good – the appropriateness of a change over which there are contending

views – is determined is to ask where the level of resolution might lie.

References

Alexashin, Y. and Blenkinsopp, J. (2005) ‘Changes in Russian Managerial Values: A Test of the

Convergence Hypothesis?’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(3):

427 – 44.

Amin, A. (1997) ‘Placing Globalization Theory’, Theory, Culture and Society, 14(2): 123 – 37.

Balnaves, M. and Caputi, P. (1993) ‘Corporate Constructs: To What Extent are Personal Constructs

Personal?’, International Journal of Personal Construct Psychology, 6: 119 – 38.

Barkema, H.G., Bell, J.H.J. and Pennings, J.M. (1996) ‘Foreign Entry, Cultural Barriers and

Learning’, Strategic Management Journal, 17: 151 – 66.

Bednarzik, R.W. (1990) ‘Helping Poland Cope with Unemployment’, Monthly Labor Review,

113(12): 25 – 34.

Czarniawska, B. (1986) ‘The Management of Meaning in the Polish Crisis’, Journal of

Management Studies, 23(3): 313 – 31.

Czarniawska, B. and Joerges, B. (1996) ‘Travels of Ideas’. In Czarniawska, B. and Sevon, G. (eds)

Translating Organizational Change. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Davies, N. (2005) God’s Playground: A History of Poland, 2nd edn. London: Oxford University

Press.

Dobosz, D. and Jankowicz, A.D. (2002) ‘Knowledge Transfer of the Western Concept of Quality’,

Human Resource Development International, 5(3): 353 – 67.

Dyczewski, L. (ed.) (2002) Values in the Polish Cultural Tradition. Washinton, DC: The Council

for Research in Values and Philosophy.

Flanagan, J.C. (1954) ‘The Critical Incident Technique’, Psychological Bulletin, 51: 237 – 58.

Fransella, F. (1995) George Kelly. London: Sage.

Gesteland, R.R. (1999) Cross-Cultural Business Behavior: Marketing, Negotiating and Managing

across Cultures. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press.

Gilbert, K. and Gorlenko, E. (1999) ‘Transplant and Process-oriented Approaches to International

Management Development: An Evaluation of British-Russian Cooperation’, Human Resource

Development International, 2(4): 335 – 54.

Gombrowicz, W. (2003) Trans-Atlantyk. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Literackie.

GUS (1998) Rocznik Statystyczny Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (Statistical Yearbook of the Republic

of Poland). Warsaw, Poland: Glowny Urzad Statystyczny.

Hall, E.T. (1966) The Hidden Dimension: Man’s Use of Space in Public and Private. London:

Bodley Head.

Hellriegel, D., Slocum, Jnr, J.W. and Woodman, R.W. (1995) Organizational Behavior, 7th. edn.

Minneapolis, MN: West Publishing Company.

Hoffman, E. (1989) Lost in Translation: A Life in a New Language. London: Vintage.

Hofstede, G. (1991) Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. London: McGraw-Hill.

Holden, N.J. (2002) Cross-Cultural Management: A Knowledge Management Perspective.

London: Pearson Education.

Honey, P. (1979) ‘The Repertory Grid in Action’, Industrial and Commercial Training, 11: 452 – 9.

Jankowicz, A.D. (1994) ‘The New Journey to Jerusalem: Mission and Meaning in the Managerial

Crusade to Eastern Europe’, Organization Studies, 15(4): 479 – 507.

Jankowicz, A.D. (1996) ‘On “Resistance to Change” in the Post-command Economies and

Elsewhere’. In Lee, M., Letiche, H., Crawshaw, R. and Thomas, M. (eds) Management

2032

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Education in the New Europe: Boundaries and Complexity. London: International Thomson

Business Press, pp. 139 – 62.

Jankowicz, A.D. (2001) ‘Limits to Knowledge Transfer: What They Already Know in the Post-

command Economies’, Journal of East-West Business, 7(2): 37 – 59.

Jankowicz, A.D. (2003) The Easy Guide to the Repertory Grid. Chichester: Wiley.

Jankowicz, A.D. (2004) ‘Do they do HRD in the Post-command Economies? The Measurement of

Meaning Transfer across Cultural Boundaries’. In Garavan, T., Collins, E., Morley, M.J.,

Carberry, R., Gubbins, C. and Prendeville, L. (eds) Proceedings of the Fifth UFHRD/AHRD

Conference on Human Resource Development Research and Practice Across Europe. Limerick:

Intersource Group Publishing.

Kasprzyk, M. (n.d.) ‘The History of Poland: Decline and Partition’. online at: http://www.kasprzyk.

demon.co.uk/www/Decline.html (accessed 5 October 2005).

Kelly, G.A. (1955) The Psychology of Personal Constructs, 1st edn. New York: Norton.

Kelman, H.C. (1958) ‘Compliance, Identification, and Internalization: Three Processes of Opinion

Change’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2(1): 51 – 60.

Kiessling, T. and Harvey, M. (2005) ‘Strategic Global Human Resource Management Research in

the Twenty-first Century: An Endorsement of the Mixed-method Research Methodology’,

International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(1): 22 – 45.

Kostera, M. (1995) ‘Differing Managerial Responses to Change in Poland’, Organization Studies,

16(4): 673 – 97.

Kostera, M. (1996) Postmodernizm w Zarzadzaniu (Postmodernism in Management). Warsaw:

Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne.

Kozminski, A.K. (1993) Catching up? Case Studies in Organizational and Management Change in

the Former Socialist Block. Albany, NJ: SUNY Press.

Krysakowska-Budny, E. and Jankowicz, A.D. (1991) ‘Poland’s Road to Capitalism’, Salisbury

Review, 10(1): 28 – 31.

Latour, B. (1986) ‘The Powers of Association’. In Law, J. (ed.) Power, Action and Belief. London:

Routledge and Kegan Paul, pp. 261 – 77.

Lee, M. (1995) ‘Working with Choice in Central Europe’, Management Learning, 26(2): 215 – 30.

Maczynski, J. (1994) ‘Culture and Leadership Styles: A Comparison of Polish, Austrian and US

Managers’, Polish Psychological Bulletin, 25(4): 303 – 15.

Mikulowski-Pomorski, J. (1991) ‘New Challenge for a New Europe’. In Hausner, J., Jessop, B. and

Nielsen, K. (eds) Markets, Politics and the Negotiated Economy: Scandinavian and Post-

Socialist Perspectives. Krakow, Poland: Academy of Economics Press, pp. 113 – 24.

Mikulowski-Pomorski, J. (1993) ‘The Drifting Society’. In Jessop, R., Hausner, J. and Nielsen, K.

(eds) Institutional Frameworks of Market Economies. Aldershot: Avebury Press.

Milosz, C. (1981) The Captive Mind. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Nowak, W. (2005) ‘Dwie Minuty kontra Trzy’, (‘Two Minutes versus Three’) 25 April Gazeta

Wyborcza, 15(628): 12 – 14.

Obloj, K. and Kostera, M. (1994) ‘Polish Privatization Program: Symbolism and Cultural Barriers’,

Industrial and Environmental Crisis Quarterly, 1: 7 – 21.

Proctor, T., Hua Tan, K. and Fuse, K. (2004) ‘Cracking the Incremental Paradigm of Japanese

Creativity’, Creativity and Innovation Management, 13(4): 207 – 15.

Rogers, E.M. (1995) Diffusion of Innovations, 2nd edn. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press.

Roney, J.L. (1997) ‘Cultural Implications of Implementing TQM In Poland’, Journal of World

Business, 32(3): 152 – 68.

Roney, J.L. (2000) Webs of Resistance in a Newly Privatized Polish Firm: Workers React To

Organizational Transfromation. New York and London: Garland Publishing.

Schein, E. (1996) ‘Culture: The Missing Concept in Organization Studies’, Administrative Science

Quarterly, 41(2): 229.

Slowacki, J. (2004) Kordian. Krakow: GREG.

Szalkowski, A. and Jankowicz, A.D. (2004) ‘The Development of Human Resources During the

Process of Economic and Structural Transformation in Poland’, Advances for Developing

Human Resources, 6(3), Special issue: 346 – 54.

Dobosz-Bourne and Jankowicz: Reframing resistance to change

2033

Tischner, J. (1992) Etyka Solidarnosci oraz Homo Sovieticus (The Ethic of Solidarity and Homo

Sovieticus). Krakow, Poland: Wydawnictwo Znak.

Tremblay, M.A. (1982) ‘The Key Informant Technique: A Non-ethnographic Application’. In

Burgess, R. (ed.) Field Research: A Sourcebook and Field Manual. London: Allen and Unwin.

Trompenaars, F. and Hampden-Turner, C. (1997) Riding the Waves of Culture, 2nd edn. London:

Nicholas Brealey.

Wickens, P. (1987) The Road to Nissan: Flexibility, Quality, Teamwork. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Zaleska, K.J. (1998) ‘Polish Managers in Subsidiaries of Multinational Corporations: International

Business as an Agent of Change’, Unpublished PhD thesis Canterbury: University of Kent.

Zeromski, S. (2001) Przedwiosnie ( Early Spring). Warsaw: Rytm.

2034

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

General Motors (GM), Kody błędów DTC PL

Defining the General Motors 2 Mode Hybrid Transmission

William Pelfrey Billy, Alfred, and General Motors, The Story of Two Unique Men, a Legendary Company

Basic AC Generators and Motors

General performance motors EN 12 2008

Basic AC Generators and Motors

General performance motors EN 12 2008

Education in Poland

15 Sieć Następnej Generacjiid 16074 ppt

Solid Edge Generator kół zębatych

37 Generatory Energii Płynu ppt

40 0610 013 05 01 7 General arrangement

Eksploatowanie częstościomierzy, generatorów pomiarowych, mostków i mierników RLC

Biomass Fired Superheater for more Efficient Electr Generation From WasteIncinerationPlants025bm 422

więcej podobnych podstron