Myths and Truths of

Stretching

Individualized Recommendations for Healthy

Muscles

Ian Shrier, MD, PhD; Kav Gossal, MD

THE PHYSICIAN AND SPORTSMEDICINE - VOL 28 - NO. 8 -

AUGUST 2000

In Brief: Stretching recommendations are clouded by

misconceptions and conflicting research reports. This review of the current literature on

stretching and range-of-motion increases finds that one static stretch of 15 to 30 seconds

per day is sufficient for most patients, but some require longer durations. Heat and ice

improve the effectiveness of static stretching only if applied during the stretch. Physicians

should know the demands of different stretching techniques on muscles when making

recommendations to patients. An individualized approach may be most effective based on

intersubject variation and differences between healthy and injured tissues.

D

espite limited evidence, stretching has been promoted for years as an integral part of

fitness programs to decrease the risk of injury (1-6), relieve pain associated with

"stiffness" (5), and improve sport performance (4-6). Many different stretching

recommendations have come out of the medical literature, and new research has

challenged some long-held concepts about common stretching practices. As a result,

misconceptions and misinterpretations are common--not just among patients, but among

healthcare professionals, as well. Thus, many clinicians are at a difficult crossroads when

making sound recommendations to patients.

Proposed Stretching Benefits

Proposed mechanisms are thought to be either (1) a direct decrease in muscle stiffness

(defined as the force required to produce a given change in length) via passive viscoelastic

changes or (2) an indirect decrease due to reflex inhibition and consequent viscoelasticity

changes from decreased actin-myosin cross-bridging. Decreased muscle stiffness would

then allow for increased joint range of motion.

New evidence suggests that stretching immediately before exercise does not prevent

overuse or acute injuries (7,8). However, results from animal studies suggest that

continuous stretching (ie, 24 hours per day) over days, compared with intermittent

stretching of only minutes per day, outside of exercise periods may produce muscle

Page 1 of 10

The Physician and Sportsmedicine: Myths and Truths of Stretching

9/11/2000

http://www.physsportsmed.com/cover.htm

hypertrophy (9-11), which could theoretically reduce the risk of injury (9,12). However,

clinical research on stretching minutes per day is still inconclusive (13,14), and more

research is needed before definitive conclusions can be made.

With respect to alleviating the pain associated with stiffness, the weight of the evidence

suggests that the decrease in stiffness is not as important as the increase in "stretch

tolerance" (15-17). Briefly, an increase in stretch tolerance means that patients feel less

pain for the same force applied to the muscle. The result is increased range of motion, even

though true stiffness does not change. This could occur through increased tissue strength or

analgesia; however, increased stretch tolerance that occurs immediately after stretching

must be caused by an analgesic effect because tissue strength does not increase during 2

minutes of stretching. Unfortunately, evidence of a possible analgesic effect is recent, and

the underlying mechanism is unknown. After weeks of stretching, increases in stretch

tolerance could theoretically occur because stretch-induced hypertrophy may increase

tissue strength (9-11), and/or an analgesia effect may be present.

A Search for Answers

Despite the controversies mentioned previously, stretching still decreases pain and may

provide substantial benefits if used under appropriate conditions. However, the problem

remains on how to choose an appropriate stretching protocol. Most authors now believe

ballistic stretching (ie, bouncing) is dangerous (4-6,18). Time recommendations for

holding a stretch vary between 10 and 60 seconds (5,19-24). Clinicians are also faced with

choosing a method that may improve the effectiveness of stretching: superficial heat,

superficial ice, deep heat, and warm-up (25-30).

To determine which stretching techniques are most effective, we reviewed all studies cited

on MEDLINE and SPORTDiscus that compared stretching protocols for increasing range

of motion. We chose range of motion as the end point because it is the tangible objective

most people use when they stretch and because most studies have not addressed true

muscle stiffness.

We addressed the following questions: (1) How long and how many times should a stretch

be performed to obtain maximum benefit?, (2) Does temperature alter the effectiveness of

stretching?, and (3) Which stretching method is most effective: static, ballistic, or

proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) stretching?

Our review includes only studies of range of motion involving healthy muscle-tendon

units--not diseased or abnormal capsular or ligamentous restrictions such as adhesive

capsulitis that may require a different duration and frequency of stretching to increase

range of motion (31,32). In addition, we could not find any papers that investigated the

effects of stretching on injured patients. Any extrapolations of our review to injured

patients should be performed with caution.

Duration and Frequency

Before discussing the evidence on how long to hold a stretch, it is necessary to explain the

concept of viscoelasticity. Stretches must be held to obtain maximum range of motion

because muscles are not purely elastic, but rather viscoelastic. An elastic substance such as

a rubber band lengthens for a given force and returns to its original length immediately

upon release. The effect is not dependent on time. On the other hand, the flow and

movement of a viscous substance such as molasses depends on time (33). A viscoelastic

substance exhibits both properties. Therefore, muscle length increases over time if a

Page 2 of 10

The Physician and Sportsmedicine: Myths and Truths of Stretching

9/11/2000

http://www.physsportsmed.com/cover.htm

constant force is applied (creep, figure 1A: not shown), or the force decreases over time if

the muscle is stretched to a constant length and held (stress-relaxation, figure 1B: not

shown). When the force is removed, the substance slowly returns to its original length.

This is different from plastic deformation, in which a material such as a plastic bag

remains permanently elongated even after the force is removed (33). Note that though

stretches also affect tendons and other connective tissue, within the context of normal

stretching, the stiffness of the overall motion is mostly related to the least stiff section (ie,

resting muscle) and is minimally affected by the stiffness of tendons.

Patients are given many common protocols on stretch duration. In summary, for both the

immediate (within 60 minutes) and long-term (over weeks) range-of-motion increases,

research shows that one 15- to 30-second stretch per muscle group is sufficient for most

people, but some people or muscle groups require longer duration or more repetitions. For

immediate effects, stretching increases range of motion through both a decrease in

viscoelasticity and an increase in stretch tolerance (ie, the analgesic effect previously

discussed). With long-term stretching, viscoelasticity remains constant and the increased

range of motion occurs only because more force can be applied to the muscle before the

subject feels pain (ie, increased stretch tolerance).

Immediate effects. The immediate effects of stretching on range of motion have been

studied in animals and humans. In isolated rabbit extensor digitorum and anterior tibialis

muscles that were stretched for 30 seconds, viscoelastic effects increased muscle length

until the fourth stretch (34). These results are consistent with those of human hamstring

muscles that showed decreased stiffness with five repeated stretches (35).

However, Madding et al (24) found that increased hip abduction range of motion did not

differ between 15, 45, or 120 seconds of stretching. Although these results may appear

contradictory, viscoelasticity may vary by muscle group. In support of this theory,

Henricson et al (27) found that muscles differed in their response to heat plus stretching. If

true, the optimal duration and frequency for stretching may also vary by muscle group.

Alternatively, range of motion in humans might be primarily limited by pain (15-17). If

this theory is true, any smaller benefits obtained from decreased viscoelasticity with

longer-duration stretches would be overshadowed by the large changes in range of motion

from stretch-induced analgesia (stretch tolerance).

Long-term effects. The long-term effects of stretching on range of motion have been

studied in humans only. After 6 weeks, individuals randomized to stretch for 30 seconds

per muscle each day increased their range of motion much more than those who stretched

15 seconds per muscle each day. (A small increase in range of motion in the 15-second

group was not statistically significant.) No further increase was seen in the group that

stretched for 60 seconds (19).

In another study conducted over 6 weeks, the same researchers (22) found that one

hamstring stretch of 30 seconds each day produced the same results as three stretches of 30

seconds. However, the results of Borms et al (36) appear to contradict these findings

because 10-second stretches were as effective as 20- or 30-second stretches. Closer

inspection of Borms' data, however, reveals large variation among individuals, and the

study was performed over 10 weeks instead of 6 weeks. If one examines the data for

trends, it appears that the 20-second and 30-second groups reached a plateau after 7 weeks,

but the 10-second group increased gradually over the entire 10 weeks. Therefore, 30-

second stretches are likely to achieve the maximum benefit quicker (within 6 to 7 weeks)

than 10-second stretches, but the two programs eventually achieve similar results by 10

weeks.

Page 3 of 10

The Physician and Sportsmedicine: Myths and Truths of Stretching

9/11/2000

http://www.physsportsmed.com/cover.htm

Rationale for individualized programs. The above studies support the use of 30-second

stretches as part of a general fitness program. This may be appropriate for group exercise

classes in which one would want to use a duration that would benefit most individuals--

similar to the recommended dietary allowance for vitamins and minerals. However,

physicians and physical therapists usually treat individuals rather than groups.

In the animal study (34) that showed maximum benefit with four stretches, response varied

depending on the individual experimental muscle. Consequently, some muscles must have

achieved maximum benefit after two to three stretches, whereas others required five to six

stretches. In human long-term studies, some individuals gained much range of motion with

only 15 seconds of stretching, while others gained very little with 45 seconds (24).

Finally, all of the current research has been done on healthy tissue. Because muscle fatigue

decreases viscoelasticity (37), it is reasonable to predict that injuries (with torn tissue,

deposition of scar tissue, tissue reorganization, and muscle atrophy and weakness) will also

change viscoelasticity, though the direction of the change is not clear. Therefore,

healthcare professionals should be cautious about extrapolating these results to injured

athletes, who may require longer stretches to increase range of motion. (See "Safety

Concerns in Stretching," below.)

Rather than give everyone the same stretching recipe, we prefer to individualize our

prescription to account for intersubject variation and differences between healthy and

injured tissues. We advise patients to stretch until they feel a certain amount of tension or

slight pulling associated with this length, but no pain. As the stretch is held, stress-

relaxation occurs, and the force on the muscle decreases. When patients feels less tension

because of changes in viscoelasticity and an analgesic effect, they can then simply increase

the muscle length again until they feel the original tension. The second part of the stretch is

held until patients feel no further increase.

If patients return for follow-up and have not gained any range of motion, and they are not

overstretching (forcing a stretch, causing muscle spasm or pain), intersubject variability

cited above may be the reason, and the clinician should consider recommending that the

stretch be held longer. The effectiveness of this approach, however, remains to be tested.

Temperature Effects

In summary, passive warming of a muscle before stretching or icing during the stretch can

be used to increase the range of motion but will not prevent injury. Patients who include an

active warm-up period prior to stretching obtain the greatest range of motion. Contrary to

popular belief, warm-up performed without stretching does not increase range of motion.

Most of the research in this area has been done on animals using passive warming devices

such as heat lamps. Research in humans often uses activity to warm the muscle, but

activity affects the muscle in many ways--for example, calcium release and motor unit

recruitment patterns--besides simply raising the temperature. This may explain the

different results observed in animals and humans.

Passive warm-up and icing. Several studies examined the effect of temperature on range

of motion. When applied before a static stretch, neither heat nor ice significantly affected

the range of motion during active knee extension--a test of hamstring range of motion--

when compared with stretching alone (38). Though heat alone did not improve range of

motion, stretch plus heat was superior to stretch alone with respect to increases in hip

flexion, abduction, and external rotation (27); shoulder range of motion (30); and triceps

Page 4 of 10

The Physician and Sportsmedicine: Myths and Truths of Stretching

9/11/2000

http://www.physsportsmed.com/cover.htm

surae range of motion (25). Ice applied during a static stretch was the most effective

method for increasing range of motion during a passive static stretch (29), but only when

applied during the earlier stages of the stretch (30). Cold application during PNF stretching

did not improve range of motion above the normal PNF technique (26).

In summary, despite some conflicting results, applying either ice or heat during a static

stretch increases the range of motion compared with static stretch alone, but it has no effect

during PNF stretches. Because ice and heat both increase range of motion and decrease

pain, but have opposite effects on stiffness, the mechanism for the increased range of

motion is probably analgesia rather than decreased stiffness.

Active warm-up. Most people believe that the light activity performed during warm-up

will increase muscle temperature, decrease muscle stiffness, and increase range of motion.

Animal studies consistently show a decrease in stiffness if the muscle or tendon is

preheated (39-41). However, the range of temperatures studied is usually outside the

normal physiologic range in humans (39-41).

In humans, the effectiveness of active warm-up to decrease stiffness appears to be related

to the type of warm-up exercise and the muscle tested. For example, running appears to

decrease the stiffness of the calf muscles (42) but not the hamstring muscles (43); running

had no effect on range of motion in these studies. Stretching added after warm-up

decreases hamstring muscle stiffness (range of motion not reported); however, the effect

lasts less than 30 minutes, even if exercise continues after stretching (43). In the only study

that measured the effect of cycling, hamstring or quadriceps range of motion did not

change, although ankle range of motion increased (stiffness not measured ) (44). In another

study, 15 minutes of cycling increased passive hip flexion and extension (stiffness was not

measured) (45), but the pelvis was not properly stabilized during range-of-motion

measurement.

Although activity by itself does not have a major effect on range of motion, studies

consistently show greater range-of-motion increases after warm-up followed by stretching

than after stretching alone (42,44). This research has probably been the basis for the

recommendation to always warm up before stretching. The problem is that most people

interpret it to mean that stretching before exercise prevents injuries, even though the

clinical and basic science research suggests otherwise (7,8). A more precise interpretation

is that warm-up prevents injury (46-49), whereas stretching has no effect on injury (7,8).

Therefore, if injury prevention is the primary objective (eg, recreational athletes who

consider performance a secondary issue) and the range of motion necessary for an activity

is not extreme, the evidence suggests that athletes should drop the stretching before

exercise and increase warm-up.

Which Method Is Most Effective?

In general, PNF stretching has resulted in greater increases in range of motion compared

with static or ballistic stretching (26,50-56), though some results have not been statistically

significant (57-59).

Of the different types of PNF techniques, the agonist-contract-relax method (the hip

flexors, including quadriceps muscles, actively stretch the hamstrings, followed by a

maximal quadriceps contraction and passive holding) appears superior to the contract-relax

method (muscle contraction followed by passive stretching) (50,54-56), which appears

superior to the hold-relax technique (isometric contraction with resistance gradually

applied over 9 seconds) (50,54-56,60).

Page 5 of 10

The Physician and Sportsmedicine: Myths and Truths of Stretching

9/11/2000

http://www.physsportsmed.com/cover.htm

For those who prefer the simplicity of static stretching, one study (61) reported that static

stretching (continuous stretching without rest) is superior to cyclic stretching (applying a

stretch, relaxing, and reapplying the stretch), whereas two studies (62,63) suggested no

difference. All of these studies involved stretching the hamstring muscles, and

methodological reasons for the discrepancy were not apparent. More research is needed

before definitive conclusions can be made.

Take-Home Points

Many of the different proposed protocols for stretching have some support from the

published literature. The major points for clinical practice are:

!

Heat, ice, and warm-up all increase the effectiveness of stretching to increase range

of motion, but only warm-up is likely to prevent injury.

!

Although one 30-second stretch per muscle group is sufficient to increase range of

motion in most healthy people, it is likely that longer periods or more repetitions are

required in some people, injuries, and/or muscle groups.

!

Individuals should determine a strategy for themselves by simply holding a stretch

until no additional benefit is obtained.

!

Though PNF stretching is the most effective technique for increasing range of

motion, the mechanism is an increase in stretch tolerance, and the muscle actually

undergoes an eccentric contraction during the stretch. The increased analgesia may

aid in performance but theoretically increases the risk of injury when compared with

static stretches.

References

1. Best TM: Muscle-tendon injuries in young athletes. Clin Sports Med 1995;14

(3):669-686

2. Garrett WE Jr: Muscle strain injuries: clinical and basic aspects. Med Sci Sports

Exerc 1990;22(4):436-443

3. Safran MR, Seaber AV, Garrett WE Jr: Warm-up and muscular injury prevention: an

update. Sports Med 1989;8(4):239-249

4. Shellock FG, Prentice WE: Warming-up and stretching for improved physical

performance and prevention of sports-related injuries. Sports Med 1985;2(4):267-

278

5. Beaulieu JE: Developing a stretching program. Phys Sportsmed 1981;9(11):59-65

6. Stamford B: Flexibility and stretching. Phys Sportsmed 1984;12(2):171

7. Pope RP, Herbert RD, Kirwan JD, et al: A randomized trial of preexercise stretching

for prevention of lower-limb injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32(2):271-277

8. Shrier I: Stretching before exercise does not reduce the risk of local muscle injury: a

critical review of the clinical and basic science literature. Clin J Sport Med 1999;9

(4):221-227

9. Alway SE: Force and contractile characteristics after stretch overload in quail

anterior latissimus dorsi muscle. J Appl Physiol 1994:77(1):135-141

10. Leterme D, Cordonnier C, Mounier Y, et al: Influence of chronic stretching upon rat

soleus muscle during non-weight-bearing conditions. Pflügers Arch 1994;429

(2):274-279

11. Goldspink DF, Cox VM, Smith SK, et al: Muscle growth in response to mechanical

stimuli. Am J Physiol 1995;268(2 pt 1):E288-E297

12. Yang H, Alnaqeeb M, Simpson H, et al: Changes in muscle fibre type, muscle mass

and IGF-I gene expression in rabbit skeletal muscle subjected to stretch. J Anat

1997;190(pt 4):613-622

Page 6 of 10

The Physician and Sportsmedicine: Myths and Truths of Stretching

9/11/2000

http://www.physsportsmed.com/cover.htm

13. Hartig DE, Henderson JM: Increasing hamstring flexibility decreases lower

extremity overuse injuries in military basic trainees. Am J Sports Med 1999;27

(2):173-176

14. Hilyer JC, Brown KC, Sirles AT, et al: A flexibility intervention to reduce the

incidence and severity of joint injuries among municipal firefighters. J Occup Med

1990;32(7):631-637

15. Halbertsma JP, Mulder I, Goeken LN, et al: Repeated passive stretching: acute effect

on the passive muscle moment and extensibility of short hamstrings. Arch Phys Med

Rehabil 1999;80(4):407-414

16. Magnusson SP, Simonsen EB, Aagaard P, et al: Mechanical and physical responses

to stretching with and without preisometric contraction in human skeletal muscle.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996;77(4):373-378

17. Halbertsma JP, van Bolhuis AI, Goeken LN: Sport stretching: effect on passive

muscle stiffness of short hamstrings. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996;77(7):688-692

18. Stark SD: Stretching techniques, in The Stark Reality of Stretching. Richmond, BC:

Stark Reality Publishing, 1997, pp 73-80

19. Bandy WD, Irion JM: The effect of time on static stretch on the flexibility of the

hamstring muscles. Phys Ther 1994:74(9):845-852

20. Bohannon RW: Effect of repeated eight-minute muscle loading on the angle of

straight-leg raising. Phys Ther 1984;64(4):491-497

21. Anderson B, Burke E: Scientific, medical, and practical aspects of stretching. Clin

Sports Med 1991;10(1):63-86

22. Bandy WD, Irion JM, Briggler M: The effect of time and frequency of static

stretching on flexibility of the hamstring muscles. Phys Ther 1997;77(10):1090-1096

23. Zito M, Driver D, Parker C, et al: Lasting effects of one bout of two 15-second

passive stretches on ankle dorsiflexion range of motion. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther

1997;26(4):214-221

24. Madding SW, Wong JG, Hallum A, et al: Effect of duration of passive stretch on hip

abduction range of motion. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1987;8:409-416

25. Wessling KC, DeVane DA, Hylton CR: Effects of static stretch versus static stretch

and ultrasound combined on triceps surae muscle extensibility in healthy women.

Phys Ther 1987;67(5):674-679

26. Cornelius WL, Ebrahim K, Watson J, et al: The effects of cold application and

modified PNF stretching techniques on hip joint flexibility in college males. Res Q

Exerc Sport 1992;63(3):311-314

27. Henricson AS, Fredriksson K, Persson I, et al: The effect of heat and stretching on

the range of hip motion. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1984:110-115

28. Williford HN, East JB, Smith FH, et al: Evaluation of warm-up for improvement in

flexibility. Am J Sports Med 1986;14(4):316-319

29. Brodowicz GR, Welsch R, Wallis J: Comparison of stretching with ice, stretching

with heat, or stretching alone on hamstring flexibility. J Ath Training 1996;31:324-

327

30. Lentell G, Hetherington T, Eagan J, et al: The use of thermal agents to influence the

effectiveness of a low-load prolonged stretch. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther

1992;16:200-207

31. Tardieu C, Lespargot A, Tabary C, et al: For how long must the soleus muscle be

stretched each day to prevent contracture? Dev Med Child Neurol 1988;30(1):3-10

32. Kottke FJ, Pauley DL, Ptak RA: The rationale for prolonged stretching for

correction of shortening of connective tissue. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1966;47

(6):345-352

33. Caro CG, Pedley TJ, Schroter RC, et al: The Mechanics of the Circulation. New

York City, Oxford University Press, 1978

34. Taylor DC, Dalton JD Jr, Seaber AV, et al: Viscoelastic properties of muscle-tendon

Page 7 of 10

The Physician and Sportsmedicine: Myths and Truths of Stretching

9/11/2000

http://www.physsportsmed.com/cover.htm

units: the biomechanical effects of stretching. Am J Sports Med 1990;18(3):300-309

35. Magnusson SP, Simonsen EB, Aagaard P, et al: Biomechanial responses to repeated

stretches in human hamstring muscle in vivo. Am J Sports Med 1996;24(5):622-628

36. Borms J, Van Roy P, Santens JP, et al: Optimal duration of static stretching

exercises for improvement of coxo-femoral flexibility. J Sports Sci 1987;5(1):39-47

37. Taylor DC, Brooks DE, Ryan JB: Viscoelastic characteristics of muscle: passive

stretching versus muscular contractions. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1997;29(12):1619-

1624

38. Taylor BF, Waring CA, Brashear TA: The effects of therapeutic application of heat

or cold followed by static stretch on hamstring muscle length. J Orthop Sports Phys

Ther 1995;21(5):283-286

39. Warren CG, Lehmann JF, Koblanski JN: Heat and stretch procedures: an evaluation

using rat tail tendon. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1976;57(3):122-126

40. Strickler T, Malone T, Garrett WE: The effects of passive warming on muscle

injury. Am J Sports Med 1990;18(2):141-145

41. Noonan TJ, Best TM, Seaber AV, et al: Thermal effects on skeletal muscle tensile

behavior. Am J Sports Med 1993;21(4):517-522

42. McNair PJ, Stanley SN: Effect of passive stretching and jogging on the series elastic

muscle stiffness and range of motion of the ankle joint. Br J Sports Med 1996;30

(4):313-318

43. Magnusson SP, Aagaard P, Larsson B, et al: Passive energy absorption by human

muscle-tendon unit is unaffected by increase in intramuscular temperature. J Appl

Physiol 2000;88(4):1215-1220

44. Wiktorsson-Möller M, Öberg BA, Ekstrand J, et al: Effects of warming up, massage,

and stretching on range of motion and muscle strength in the lower extremity. Am J

Sports Med 1983;11(4):249-252

45. Hubley CL, Kozey JW, Stanish WD: The effects of static stretching exercises and

stationary cycling on range of motion at the hip joint. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther

1984:104-109

46. Safran MR, Garrett WE Jr, Seaber AV, et al: The role of warmup in muscular injury

prevention. Am J Sports Med 1988;16(2):123-129

47. Ekstrand J, Gillquist J, Liljedahl SO: Prevention of soccer injuries: supervision by

doctor and physiotherapist. Am J Sports Med 1983;11(3):116-120

48. Ekstrand J, Gillquist J, Moller M, et al: Incidence of soccer injuries and their relation

to training and team success. Am J Sports Med 1983;11(2):63-67

49. Bixler B, Jones RL: High-school football injuries: effects of a post-halftime warm-

up and stretching routine. Fam Pract Res J 1992;12(2):131-139

50. Etnyre BR, Lee EJ: Chronic and acute flexibility of men and women using three

different stretching techniques. Res Q 1988;59:222-228

51. Wallin D, Ekblom B, Grahn R, et al: Improvement of muscle flexibility: a

comparison between two techniques. Am J Sports Med 1985;13(4):263-268

52. Tanigawa MC: Comparison of the hold-relax procedure and passive mobilization on

increasing muscle length. Phys Ther 1972;52(7):725-735

53. Sady SP, Wortman M, Blanke D: Flexibility training: ballistic, static or

proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1982;63(6):261-

263

54. Etnyre BR, Abraham LD: Gains in range of ankle dorsiflexion using three popular

stretching techniques. Am J Phys Med 1986;65(4):189-196

55. Osternig LR, Robertson RN, Troxel RK, et al: Differential responses to

proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) stretch techniques. Med Sci Sports

Exerc 1990;22(1):106-111

56. Osternig LR, Robertson R, Troxel R, et al: Muscle activation during proprioceptive

neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) stretching techniques. Am J Phys Med 1987;66

Page 8 of 10

The Physician and Sportsmedicine: Myths and Truths of Stretching

9/11/2000

http://www.physsportsmed.com/cover.htm

(5):298-307

57. Lucas RC, Koslow R: Comparative study of static, dynamic, and proprioceptive

neuromuscular facilitation stretching techniques on flexibility. Percept Mot Skills

1984;58(2):615-618

58. Worrell TW, Smith TL, Winegardner J: Effect of hamstring stretching on hamstring

muscle performance. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1994;20(3):154-159

59. Sullivan MK, Dejulia JJ, Worrell TW: Effect of pelvic position and stretching

method on hamstring muscle flexibility. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1992;24(12):1383-

1389

60. Markos PD: Ipsilateral and contralateral effects of proprioceptive neuromuscular

facilitation techniques on hip motion and electromyographic activity. Phys Ther

1979;59(11):1366-1373

61. Bandy WD, Irion JM, Briggler M: The effect of static stretch and dynamic range of

motion training on the flexibility of the hamstring muscles. J Orthop Sports Phys

Ther 1998;27(4):295-300

62. de Vries HA: Evaluation of static stretching procedures for improvement of

flexibility. Res Q 1962;32:222-229

63. Starring DT, Gossman MR, Nicholson GG Jr, et al: Comparison of cyclic and

sustained passive stretching using a mechanical device to increase resting length of

hamstring muscles. Phys Ther 1988;68(3):314-320

Safety Concerns in Stretching

Although the main objective of this article was to compare the effectiveness of different

stretching regimens to increase range of motion, we also feel it is important to discuss

safety. Follow-up studies have not investigated the safety of different stretching

modalities, so all comments here and in the medical literature are theoretical.

Some clinicians believe ballistic stretching is dangerous because the muscle may

reflexively contract if restretched quickly following a short relaxation period (ie, eccentric

or lengthening contraction) (1), and eccentric contractions are believed to increase the risk

of injury (2,3). We agree with this concern, but it is important to add that ballistic

stretching is more controlled than most athletic activities. Therefore, it is likely to be much

less dangerous than the sport itself if performed properly and not overly aggressively.

The original theory that proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) techniques

increase range of motion through reciprocal muscle inhibition, thereby decreasing

electromyographic activity, was first disproved in 1979 (4,5) and again more recently

(6,7). Muscles are electrically silent during normal stretches until end range of motion

nears. Surprisingly, PNF techniques increase electrical activity and muscle stiffness during

the stretch (4,5,7), despite the observed increase in range of motion. This means that the

muscle eccentrically contracts during the PNF stretch, which most clinicians would

consider more dangerous than electrically silent muscle. PNF and ballistic stretching both

cause an eccentric contraction, but PNF stretching appears to have a more pronounced

analgesic effect. From a safety viewpoint, it does not seem prudent to "anesthetize" a

muscle during or immediately before it is required to perform higher-risk eccentric

contractions. The benefits of the greater increase in range of motion should be balanced

against a theoretical increase in the risk of injury. (There are no data on risk of injury with

PNF stretching.)

References

Page 9 of 10

The Physician and Sportsmedicine: Myths and Truths of Stretching

9/11/2000

http://www.physsportsmed.com/cover.htm

1. Stark SD: Stretching techniques, in The Stark Reality of Stretching. Richmond, BC:

Stark Reality Publishing, 1997, pp 73-80

2. Newham DJ, McPhail G, Mills KR, et al: Ultrastructural changes after concentric

and eccentric contractions of human muscle. J Neurol Sci 1983;61(1):109-122

3. Hunter KD, Faulkner JA: Pliometric contraction-induced injury of mouse skeletal

muscle: effect of initial length. J Appl Physiol 1997;82(1):278-283

4. Markos PD: Ipsilateral and contralateral effects of proprioceptive neuromuscular

facilitation techniques on hip motion and electromyographic activity. Phys Ther

1979;59(11):1366-1373

5. Moore MA, Hutton RS: Electromyographic investigation of muscle stretching

techniques. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1980;12(5):322-329

6. Magnusson SP, Simonsen EB, Aagaard P, et al: Mechanical and physical responses

to stretching with and without preisometric contraction in human skeletal muscle.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996;77(4):373-378

7. Osternig LR, Robertson R, Troxel R, et al: Muscle activation during proprioceptive

neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) stretching techniques. Am J Phys Med 1987;66

(5):298-307

Dr Shrier is director of the Consultation Service Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and

Community Studies at Sir Mortimer B. Davis-Jewish General Hospital in Montreal. Dr

Gossal is a staff physician in the Department of Family Medicine at Saint Mary's Hospital

at McGill University in Montreal. Address correspondence to Ian Shrier, MD, PhD, Centre

for Clinical Epidemiology and Community Studies, Lady Davis Institute for Medical

Research, SMBD-Jewish General Hospital, 3755 Côte Sainte Catherine Rd, Montreal, QB

H3T 1E2; e-mail to

ishrier@med.mcgill.ca

.

JOURNAL INDEX

COVER STORY

|

THIS MONTH

|

INFO FOR AUTHORS

|

SUBSCRIBE

|

BACK ISSUES ONLINE

|

INDEX

|

SEARCH

SITE INDEX

HOME

|

JOURNAL

|

PERSONAL HEALTH

|

RESOURCE CENTER

|

CME

|

CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING

|

ABOUT US

Copyright (C) 2000. The McGraw-Hill Companies. All Rights Reserved

E-mail Privacy Policy

This page was updated August 14, 2000 by

Ann Harste

.

Page 10 of 10

The Physician and Sportsmedicine: Myths and Truths of Stretching

9/11/2000

http://www.physsportsmed.com/cover.htm

Stretching

by Patti and warren Finke, Team Oregon

Economy is a measure of a successful training program. Running economy or using as little energy as possible is an

important part of long distance running. Economic runners use less mechanical energy during running and have a

greater degree of energy transfer between the body parts. This allows the body to perform with less energy

consumption by the involved muscles. One of the most important factors in this concept is flexibility. This is

because lack of flexibility restricts the range of motion and may limit the extent of energy transfers. We will not

discuss biomechanics of running, but hope to impress upon you the need for flexibility.

Muscles contain receptors called spindles and Golgi tendon organs that provide sensory information regarding

changes in the length and tension of the muscle. The main function of the spindles is to respond to stretch in a

muscle and, through reflex action, initiate a stronger contraction to reduce this stretch. The stretch reflex mainly

responds to voluntary movements and is responsible for maintaining upright posture. Impulses from the Golgi

tendon organs cause reflex relaxation of the muscle and its opposing muscle. When the actual stretch occurs, the

spindles resist the stretch. If the stretch is held longer than 6 seconds, the Golgi tendon organs respond allowing the

muscle to reflexively relax. This lengthens the muscle and allows it to remain in a stretched position for a long

period reducing the possibility of injury due to the stretching.

The purpose of a stretching program is to relax the muscle and work it through the necessary range of motion.

Stretching a muscle the wrong way or at the wrong time can activate the stretch reflex causing the muscle to

contract and become tighter rather than relaxed. Stretching should be done after a muscle has been warmed up. We

do not suggest stretching before running when the muscles are cold and tight. Several studies have shown that pre

run stretching may lead to injury rather than preventing it. A recent study of 1500 participants in the Honolulu

Marathon actually linked the pre workout stretching with a higher risk of injuries particularly in white males. The

warm up for your run should be 5-10 minutes of walking or slow jogging. If something feels tight, you might stop

to stretch that area. After the workout, which should include a 5-10 minute cool down period of the same gentle

exercise as warm up, is a good time for a short stretching routine. Do not stretch immediately after a long run or

strenuous workout when your muscles are apt to be fatigued and dehydrated. Rehydrate and rest before stretching.

The best time is to set aside a separate period 3-5 times per week for a complete stretching routine of the exercises

shown below which should take about 20 minutes. Many runners find a gentle stretching routine done before

bedtime a relaxing habit.

Stretching is done to relax the muscles and the connective tissue. The connective tissue needs 20 seconds to relax

and the muscles take about 2 minutes to relax. There are three basic types of stretching :

!

Ballistic Stretching: the old "bounce, bounce, bounce" stretches that actually make the muscles shorter and

tighter by activating the stretch reflex. These have been found to contribute to the risk of small muscle tears,

soreness and injury. They are not recommended.

!

Static Stretching: this is a slow gradual stretch though the muscle's full range of motion until resistance is

felt. The stretch should be done slowly and carefully to the point of slight pull or slight discomfort. It should

not be painful!

!

Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF) Stretching: this is more easily called the "hold- relax"

method of stretching which involves a contraction of the muscle followed by a relaxation and a stretch. The

tightening "fools" the stretch reflex, activating the Golgi tendon organ. This aids relaxing the muscle before

the actual stretch begins and allows you to stretch the muscle further.

Stretching is not a competitive sport. Flexibility differs with the individual. Your goal should be to achieve a good

level of flexibility for you, not to match anyone else's level.

The Stretches

Page 1 of 3

Stretching

9/11/2000

http://teamoregon.com/~teamore/publications/stretch.html

The stretches shown can be done either statically without the contraction phase or using the PNF method with the

contractions. The contractions are done by tightening the muscle, not actually moving it.

The more you run, the stronger and tighter the muscles of the lower back and the entire backs of the legs become.

The first three stretches are for these muscles. The muscles of the outside of the hips and legs also become tight and

need stretching.

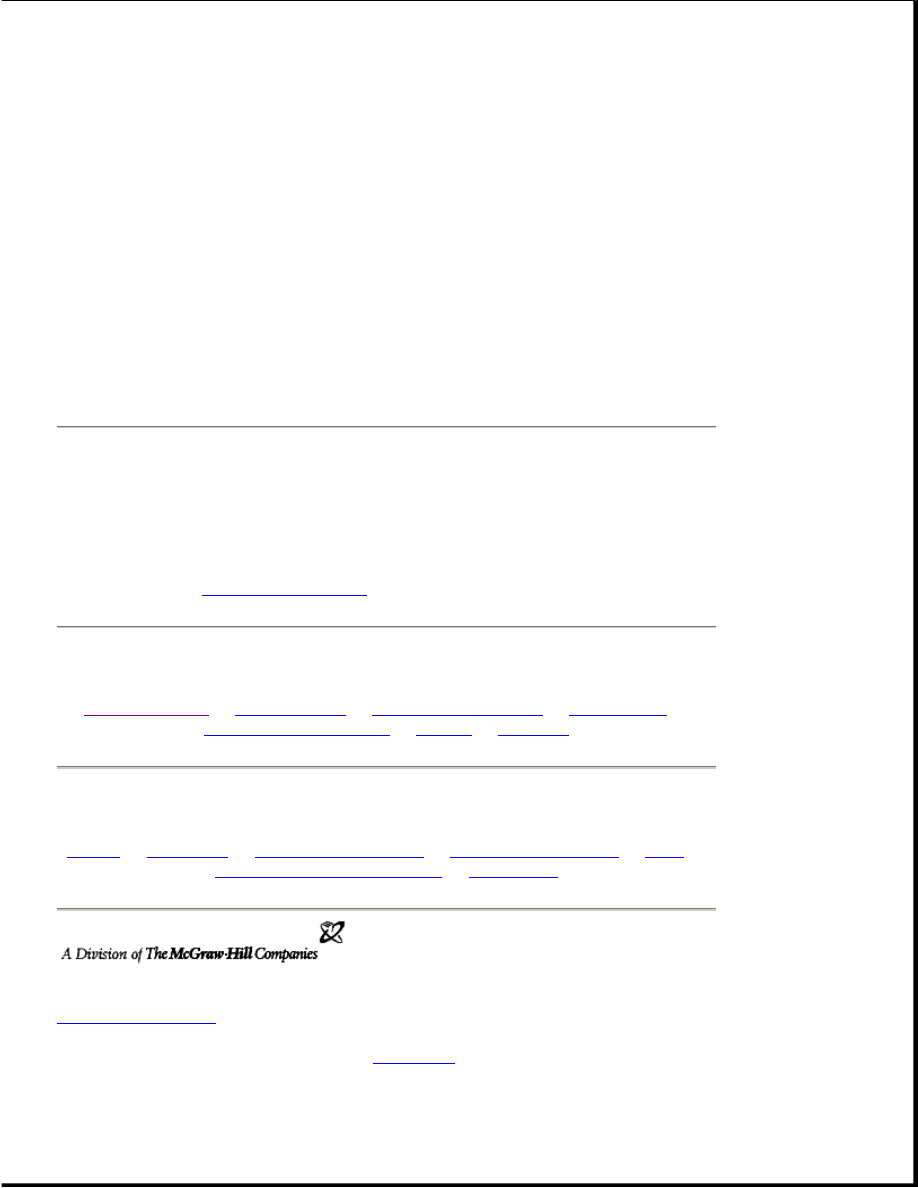

Lower Back Muscles

Position: Lie on your back, holding one knee to your chest with the other leg bent.

Make certain that the tailbone is lifted off the floor.

Contraction: Push out leg against arms, hold for 6 seconds.

Stretch: Relax, then pull leg toward chest and hold for 20 seconds. Repeat

contraction and stretch 5 times. Repeat with other leg. Repeat holding both knees to chest.

Hamstring Muscles in Backs of Thighs

Position: Lie on back with one knee bent. Position towel over bottom of shoe and

raise leg as far as comfortable.

Contraction: Push heel out and back, holding leg in place with towel, hold for 6

seconds.

Stretch: Relax, bring straight leg closer to vertical, hold for 20 seconds. Don't

worry if you can't straighten leg or bring it exactly to vertical. Repeat contraction and stretch 5 times. Repeat on

other leg.

Gastrocnemius and Soleus Muscles of the Calves

Position: Stand leaning against a wall, tree, etc. with one leg bent, the other straight

behind you with both heels on the ground.

Contraction: Lean forward with a straight back until stretch is felt in the calf. Go up

on back toes for 6 seconds.

Stretch: Come down off toes, put weight on outside of the foot mostly on the heel,

slighltly raise toes, lean forward with buttocks tucked in and hold for 20 seconds.

Repeat contraction and stretch 5 times. Repeat with back knee bent which stretches the

muscles lower down and the Achilles tendon. Repeat with other leg.

Outer Hip Muscles

Position: Lie down with one knee bent and shoulders flat. Pull one leg over the

other with the opposite hand.

Contraction: Push knee up towards ceiling against the hand and hold for 6

seconds.

Stretch: Relax and gently push the knee towards the floor while keeping the shoulders flat, hold for 20 seconds.

Repeat contraction and stretch 5 times. Repeat with other leg.

Page 2 of 3

Stretching

9/11/2000

http://teamoregon.com/~teamore/publications/stretch.html

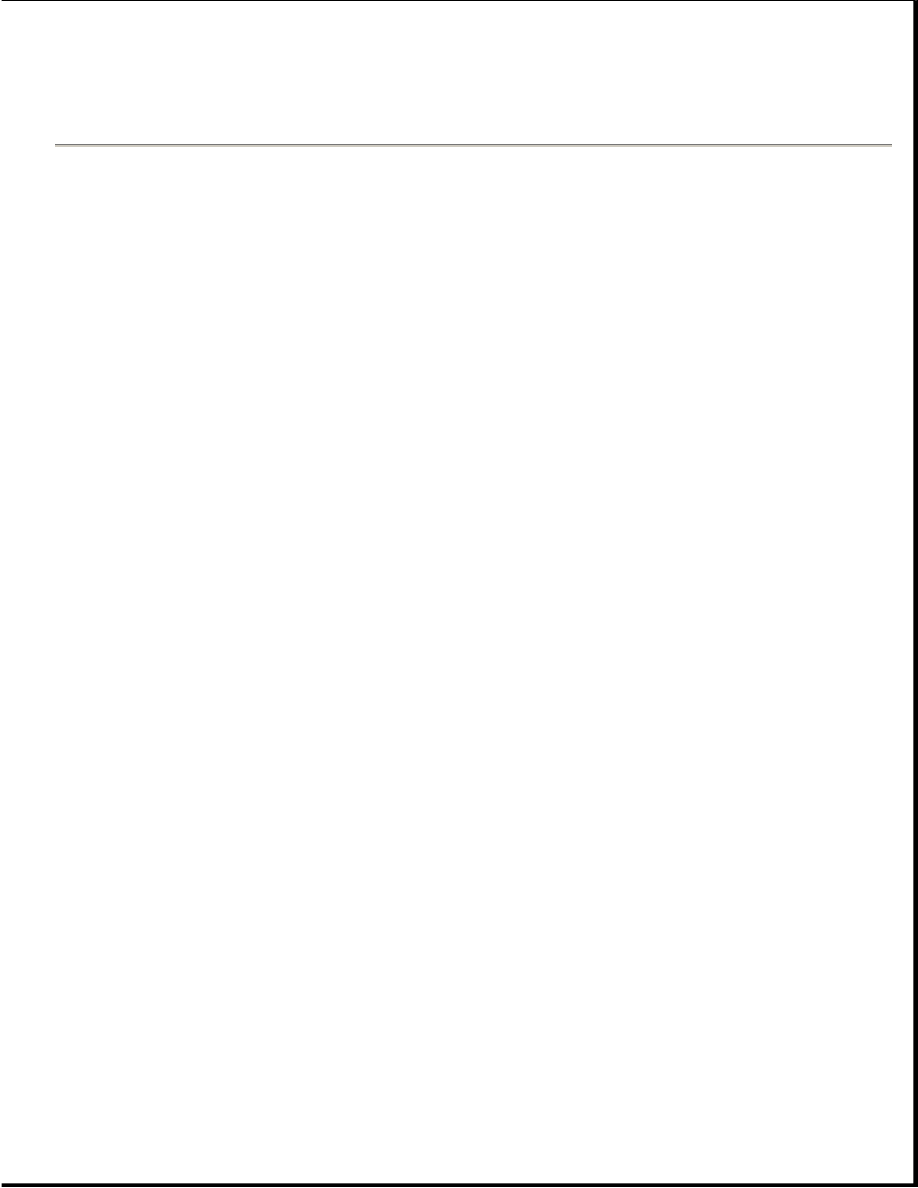

Ilio - Tibial Band

Position: Stand sideways 18-24 inches from wall or tree, use hand aginst wall for balance.

Contraction: While standing upright, hips directly under shoulders, push knees slightly away from the wall. Hold

for 6 seconds.

Stretch: Relax and bend hips toward wall dropping opposite shoulder, hold for 20 seconds. Repeat contraction and

stretch 5 times. Repeat on other side.

Other muscles frequently tight in runners, particularly those doing speed work or hill training are the quadriceps

and hip flexors in the fronts of the legs and the adductors in the inside of the thighs.

Quadriceps muscles in the front of the thighs

Position: Stand with pelvic tilt ( buttocks tucked in). Position towel around ankle and bend knee.

Contraction: Push bent knee slighly forward while holding leg in place with the towel. Hold for 6

seconds.

Stretch: Relax and pull leg backwards with the towell while retaining pelvic tilt, hold for 20

seconds. Repeat contraction and stretch 5 times. Repeat on other leg.

Hip Flexor Muscles

Position: Kneel on one knee. Position other knee slightly behind or directly over

ankle. Straighten upper body adding pelvic tilt (buttocks tucked in).

Contraction: Try to pull the knee on the floor forward, hold for 6 seconds.

Stretch: Relax, lean slightly forward maintaining pelvic tilt and hold for 20

seconds. Repeat contraction and stretch 5 times. Repeat on other side.

Adductors or the Inside Thigh Muscles.

Position: Sit with the soles of the feet together, hands on knees.

Contraction: Pull knees up against hands, hold for 6 seconds.

Stretch: Relax, let knees fall downward towards the floor, hold for 20 seconds.

Repeat contraction and stretch 5 times.

Other safe and useful stretches can be found in The Book About Stretching by

Sven-A. Solveborn, M.D.

Additional information on stretching can be found on the Web in

Stretching and Flexibility

by Brad Appleton.

Team Oregon Running Tips are Copyrighted by wY'east Consulting and Team Oregon which reserve all

commercial rights to republication.

Page 3 of 3

Stretching

9/11/2000

http://teamoregon.com/~teamore/publications/stretch.html

Home

|

Services

|

Bio

|

Benefits

|

Interests

Info

|

Articles

|

Tips

|

Links

|

|

Bottom

Instep Dance Magazine Articles

Reprints of monthly column as first appearing in Instep Dance Magazine.

April 1999

The Psoas - Stretching Revisited

By Rick Allen, DC

"Better health leads to better dancing."

Last December we examined the anatomy and function of the psoas muscle. We saw how

it is a hidden influence on posture and low back pain. My

January/February article

suggested stretches for the psoas. Last month I asked for suggestions from my readers for

the April column. Thank you, Dan Roberts, Certified Muscle Therapist from Reading,

Pennsylvania for alerting me to a better way to stretch your muscles, including the psoas.

It's called Active Isolated Stretching (AIS). While I had heard of the concept, it took

Dan's rave review by e-mail for me to research it further. Dan had taken extensive training

with the developer of AIS, Aaron Mattes, a kinesiologist and massage therapist from

Sarasota, Florida. Aaron is a consultant on stretching to the US Olympic Team. Likewise,

Jim and Phil Wharton from Gainesville, Florida have worked with many top-level athletes,

using the AIS technique to greatly improve their flexibility. The Whartons have

popularized this technique in their 1996 book, The Wharton's Stretch Book, and the

associated video, Breakthrough Stretching. I contacted their company, Maximum

Performance International (1-800-240-9805 or

www.aistretch.com

) and obtained

permission from Ron Boyle to reproduce the figures shown below which illustrate the AIS

technique.

As I pointed out in the January/February article, a key part of the answer to eliminating

common mechanical low back pain is to keep the muscles of the low back in balance. This

will improve your posture and dancing as well. Since the psoas often becomes tight and

shortened from sitting, the answer must include daily stretches and exercises to

counterbalance the tightening. I suggest you check out and incorporate AIS into your daily

routine. (For further information, I suggest you also check out the good review of

Cascade Wellness Clinic

"Dr. Rick Online"

Rick Allen, DC

221 NE 78th Avenue

Portland, OR 97213

503/257-1324

Page 1 of 3

The Psoas - Stretching Revisited

9/11/2000

http://www.teleport.com/~drrick/articles/97-99art/art32.html

stretching techniques that appeared in Outside magazine's Bodywork Column for March

1999.)

Active Isolated Stretching Technique

Active Isolated Stretching is similar to part

of the Proprioceptive Neuromuscular

Facilitation (PNF) stretching method used by

chiropractors, physical therapists, massage

therapists and other muscle specialist. It uses

the body's natural counter-balancing

neurological "wiring" to control muscles:

when you contract a muscle (the agonist)

your body automatically relaxes the

opposing muscle (the antagonist). For

example, when you tighten your biceps, your body automatically relaxes the triceps. The

full PNF pattern is done with the assistance of the doctor or therapist telling you to

"contract for about 6 seconds, relax, opposite contract, relax." It is abbreviated Contract-

Relax-Antagonist Contract-Relax or CRACR.

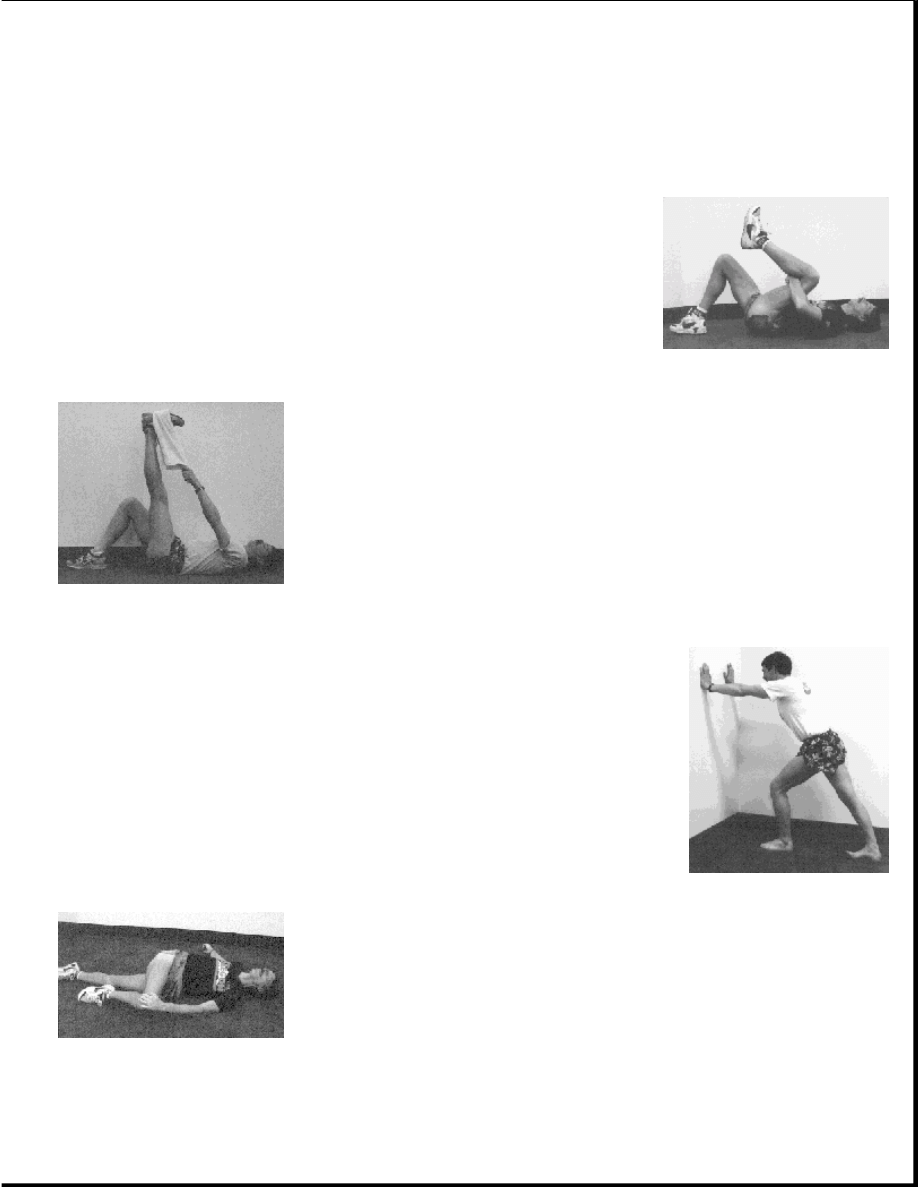

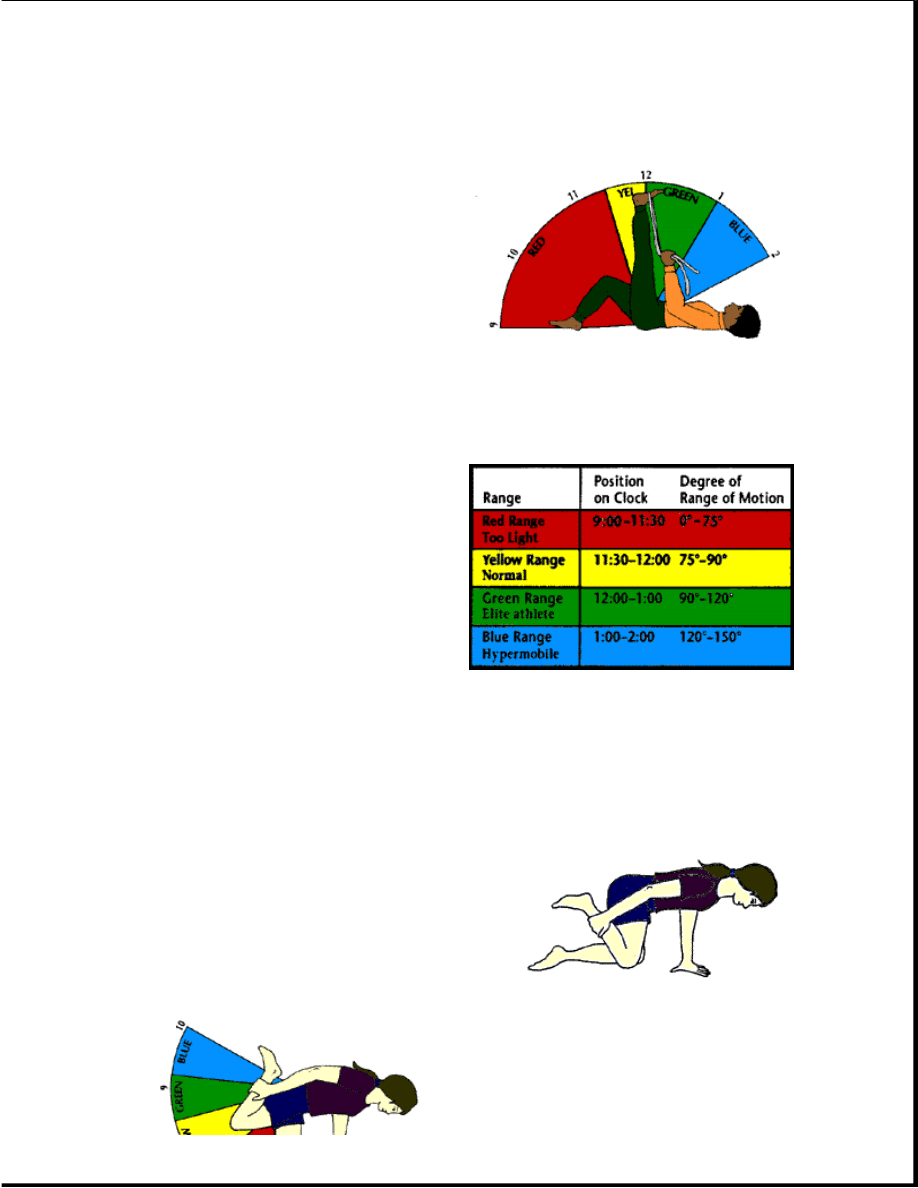

For example, to stretch the hamstring using

the AIS technique, lie on your back with

one leg bent and the other pointing straight

up with a towel or soft rope looped around

the arch of the foot (figure 1 above). (The

Whartons recommend a 9-foot section of

5/8-inch braided polypropylene or dacron

rope. I found some at Home Depot for

about $.40/foot.) Next, draw that leg

toward your chest by tightening the

quadriceps muscles on the front of the leg.

Go just a bit farther than your natural end point by pulling gently on the towel or rope

while continuing to contract the quadriceps. Hold for 2 seconds. Release the stretch before

the muscle reacts to being stretched - before it goes into a reactive protective contraction.

The safe range is shown in figure 2. Repeat this 10 times for each leg. The Wharton's

video gives you an excellent sense of the extent and timing of the movement.

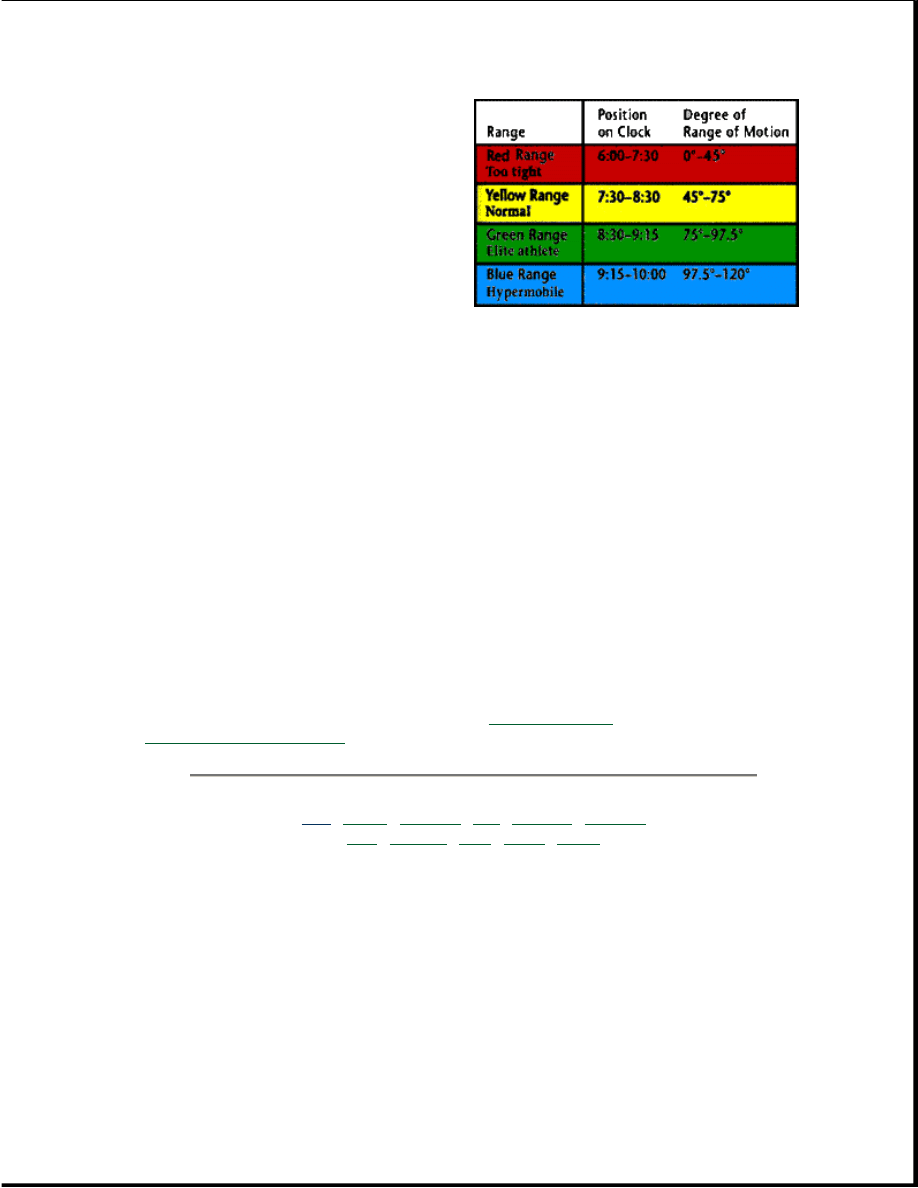

Active Isolated Stretching of the Psoas

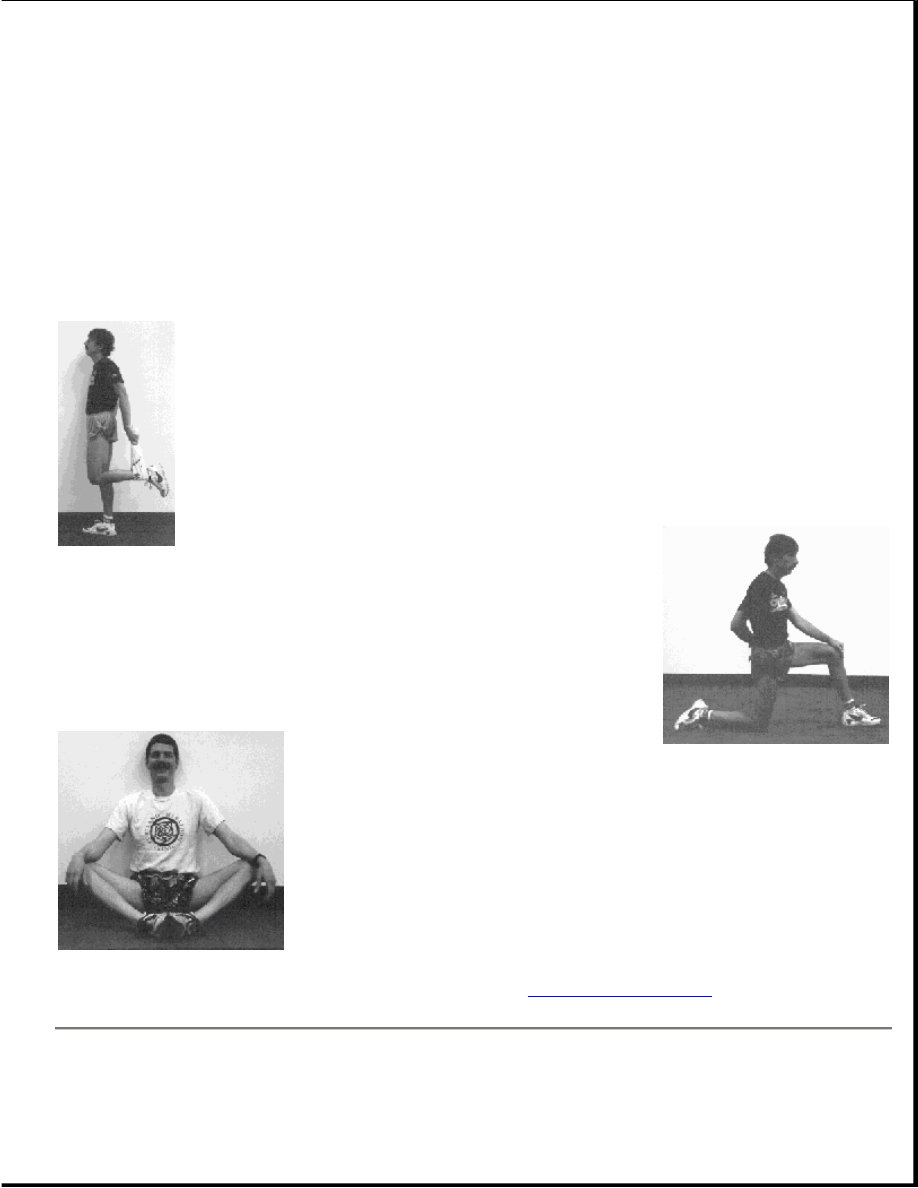

As explained in the Wharton's book, to stretch the

right psoas, "Position yourself on your hands and

knees (figure 3). Reach back with you right hand

and grasp your right ankle. Reaching it will

require that you lift your right foot to meet your

hand. Hang on tightly.

Using the hamstrings and the gluteus maximus

[buttocks], lift the exercising leg up until the thigh

is parallel to the ground - or aligned horizontally

with your body (figure 4). Be careful not to arch

your back (hyperextension). [The safe range is

shown in figure 5.] You may use your hand for

Page 2 of 3

The Psoas - Stretching Revisited

9/11/2000

http://www.teleport.com/~drrick/articles/97-99art/art32.html

gentle assistance at the end of the stretch."

Wrapping up

The Wharton's video and book give full sequences that warm up and stretch practically the

whole body, so I suggest you look at them rather than just stretching one muscle. They

show both stretching by yourself and with an assistant. Take care in doing the assisted

stretches. An inexperienced assistant could use too much force and strain the muscle.

The AIS technique is one I suggest you add to your arsenal. It is not the only technique, so

I suggest you work with it and compare the results with your current stretching routine.

[You do stretch daily, don't you?]

Once again, take care of your psoas, improve you posture and improve your life and,

especially, your dancing!

Next article: I've received a few more ideas from readers. I'll keep you in suspense until

next month.

Dr. Rick Allen is a chiropractor, massage therapist and dance student in Portland, Oregon. Dr. Rick

welcomes your questions and suggestions for future articles. However, he cannot make specific diagnoses or

treatment recommendations unless you visit him in person. He can be reached by phone: 503-257-1324,

mail: 221 NE 78th Avenue, Portland, OR 97213, e-mail:

drrick@teleport.com

or World Wide Web:

http://www.teleport.com/~drrick/

Top

|

Home

|

Services

|

Bio

|

Benefits

|

Interests

Info

|

Articles

|

Tips

|

Links

|

© 1999 Dr. Rick Allen

Page 3 of 3

The Psoas - Stretching Revisited

9/11/2000

http://www.teleport.com/~drrick/articles/97-99art/art32.html

Stretching your limitations

by Christine von Ulrich - Healthy Alternatives Office

It is known that all WPI students stretch their minds everyday! Anyone who hangs around this school and talks to

all of you could easily see that your minds are consistently being summoned, and therefore, stretched - if not by

IQPs and studies, then by recreational hobbies or clubs. Your minds are being stretched so why not put the rest of

your bodies into the motion as well! That is, in addition to stretching that big muscle in your head, stretch the rest

of your muscles... stretch your muscle power!

You are probably asking yourself at this point - "what am I talking about!" Well, it is simply this: your muscles, as

strong as they are, could not get any stronger and may even cause you aches and pains if they are not adequately

STRETCHED. Daily activities such as walking, sitting, or sleeping do not provide for any adequate stretching, and

may unevenly stretch some muscles while tightening others. The two most recommended ways of stretching are

called static stretching, and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) stretching. Ballistic stretching is also a

way of stretching and does improve one's range of motion (ROM), however there is a greater chance of injury since

part of ballistic stretching consists of muscle contraction as well.

When one performs a static stretch, the target muscle is lengthened to the point at which one feels the muscle is

stretched (usually a "slight" discomfort - but NO pain). This position is held for 10-30 seconds, relaxed, and then

usually repeated 2-3 times per target muscle, possibly using variations of the same stretch (i.e. hamstring stretch:

sitting - one leg extended in front, other leg bent in front; standing - one leg extended in front and resting on a table;

standing - upper torso is bent forward, both knees slightly bent to relieve pressure on lower back).

When doing a PNF stretch, the target muscle group is briefly contracted (approximately 5-6 seconds) against

resistance after the limb is at its end-ROM, and the contraction is less than maximal. This technique of PNF is

called Contract Relax. The second PNF technique is the Contract Relax Agonist Contract technique. With this

technique a partner tells the exerciser to "meet my resistance," the exerciser contracts, then relaxes, and the partner

attempts to move the limb beyond this point passively. PNF stretching was originally used in clinical settings.

However, in recent years this method of improving ROM has received more widespread use.

So now that you know more about stretching, you will take some time out of your busy day and begin to stretch on

a regular basis... Right?! Chances are if any one of you are like me you will have the good intentions to do it but...

you know the rest. But, GOOD NEWS - stretching could be done any time, any place, with any one... anyway, how

do you ask? You could stretch while sitting and reading Newspeak, watching SocComm's movie channel, while

talking on the phone, during a coffee break, in the bathroom, in the living room, at your desk, waiting for the bus,

...you get the picture.

So stretching is not just for pre- and post-exercise anymore. Stretching can actually help your muscles become

stronger since when muscles are tense and contracted they do not work efficiently. It can reduce your stress after

coming back from class or work!

Below are some examples of simple, yet helpful stretches. Do them for your mind and body!

If you are interested in finding out in tangible and comparable numbers how flexible you are, go to the WELLNESS

FAIR on February 14th. This event will run from 10am - 2pm in the lower wedge, and the Healthy Alternatives

Office will be conducting sit-and-reach tests to measure hamstring flexibility, and back extension tests to measure

back flexibility for anyone who is interested!

Return to this week's Index

Page 1 of 2

Stretching your limitations

9/11/2000

http://www.wpi.edu/News/Newspeak/950131/LIMITS.html

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

PNF Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation, Fizjoterapia, PNF

PNF stretching

MOTU PROPRIO Summorum Ponti

cwiczenia na bazie PNF

Stretching, Pasje, Hobby, Nauka, Studia, Szkoła, Technik masażysta

Marvel Super Heroes Gates of What If AIM Facility Map

PNF, MEDYCYNA FIZJOTERAPIA, Kinezyterapia

NEUROMODULATORY

Martial Arts Stretching

neuromobilizacje, studia pielęgniarstwo

Odnowa biologiczna stretching

Kinezyterapia ćwiczenia# 04 2008 Chod o kulach i PNF

PNF do druku

Fiozofia PNF

KONCEPCJA PNF, KINEZYTERAPIA

67 PNF – omów zasady i zastosowanie metody

więcej podobnych podstron