JOZABAD

upon both the guilty parties

(v.

This done, he

gets rid of Jotham by making him flee to Beer

unknown locality)

for fear of his (half-)brother

Abimelech’

It is the fable which interests

us

Jotham is a mere

shadow.

Some scholars

Moore) think that it was

written by the author of

7-21,

with reference to the

circumstances of Abimelech.

The fable, however, is

applicable t o Abimelech only in

so

far a s such a bad

man was sure to bring misery on himself and on his

snbjects. T o do it justice we must regard it

as

a n

independent production,

disengage it from its

setting.

I t is no objection t o

this that

v.

forms a

somewhat abrupt conclusion (Moore). W e must not

expect too much harmony in

a

Hebrew apologue;

besides, the true closing words may have been omitted.

T h e proof, however, that the fable is not by the author

of

its setting is in the imperfect parallelism between

v.

and the application in

vv.

‘ I f in

good faith you anoint me

to

be king over you, come

and enjoy my protection; but if not, beware of the

ruin which

I

shall cause you’

this is the (present)

close of the fable.

‘If

you have acted in good faith

and integrity, making Abimelech your king, much joy

may you have from your compact; but if not, then

beware

of the

ruin which Abimelech will cause you, and

let him beware of the ruin which you will cause him.’

T h e bramble-king is self-deceived; h e thinks that he

can protect others, and threatens traitors with punish-

ment.

Jotham, however, speaks a t first ironically.

H e

affects to believe that the Shechemites really trust

Abimelech, and wishes them joy of their bargain.

he changes his tone.

H e foresees that they will soon

become disloyal, and threatens them with punishment,

not, however, for their disloyalty, but because they con-

spired with Abimelech to commit murder.

T h a t the

fable, moreover, is inconsistent both with

8 2 3

is

also manifest. T h e idea of

8 2 3

is that

king-

ship makes any human sovereign superfluous ; that of

9

that the practical alternatives are oligarchy and

monarchy, and that monarchy is better.

On the other

hand, the idea of the fable is that kingship is

a

burden

which no noble-minded man will accept, because it

destroys individuality.

Each noble-minded man is

either

a

cedar,

or

a fig-tree, or a vine.

By developing

his natural powers in his allotted sphere he pleases

‘gods and men

it is alien t o him t o interfere with

others.’

Compare this fable with that of King Jehoash

in

2

K.

b.

first

(see U

ZZIAH

) and then

king of Judah

K.

[A and

32-38

[B

and

v.

[A

v.

Ch.

23

[A],

27).

T h e only facts derived from the

annals are that he built the upper gate of the

perhaps, the upper gate of Benjamin (cp Jer.

Ezek.

that in his time

began to

despatch against Judah Rezin king of Aram and Pekah

son of Remaliah’ (cp

I

SAIAH

,

3).

T h e Chronicler states that Jotham fortified cities and

castles (see

F

OREST

),

and,

as

a

reward for his

piety, makes him fight with success against the Ammon-

ites ( c p A

MMON

,

In

I

Ch.

[A],

[L].

On the chronology of

reign, see C

HRONOLOGY

,

35.

3.

One of the b’ne Jahdai, belonging

to

Caleb

(I

Ch.

See A

BIMELECH

,

T.

K. C.

JOZABAD

[BKAL]).

The name of a Gederathite (see G

EDERAH

) and two

Manassites, warriors of David;

I

Ch. 124

v.

and

see

D

A

V

ID

,

11

[a

4. An overseer in the temple:

Ch.3113

perhaps the same as

JUBILEE

See Smend,

A T

64.

2613

A

chief of the Levites

:

Ch. 35

in

I

Esd.

J

ORAM

6.

b.

Jeshua,

a

Levite, temp. Ezra (see E

Z R A

I

]

Ezra

8

33

Esd.

8

63

RV J

OSABDUS

62

One of the b’ne Pashhur,

a priest in the list of those with

wives (see E

Z R A

i.,

5

end), Ezra

Esd. 9

8.

A Levite in the list of those with foreign wives (see E

ZRA

5 end),

Esd. 9 23 (J

OZABDUS

,

[BA])

identical with

(6)

and the two following.

Expounder of law (see

ii.,

13

cp

8,

16

[

I

]

Neh.87

[L], om.

Neh. 11

the list of inhabitants of Jerusalem (E

ZRA

ii.,

5 [b],

[I]

a)

JOZABDUS

[BA]

see above).

I

I

Esd

8.

I

9

[B],

[A]),

3.

I

Esd.

948

J

OZABAD

,

RV

re-

nembers

’

; cp Zechariah ;

Jozabar [Ginsb.

Ezra

I

.

Following some

MSS

and e d d . ] ;

[B];

[AL]) b. Shimeath, one of the murderers of

( 2

K.

I n

Ch.

(Z

ABAD

perhaps for Z

ACHAR

,

cp

’B,

makes Jozachar himself, not his mother, a n Ammonite

[see S

HIMEATH

).

See

JOZADAK

Ezra

8

etc. See J

EHOZADAK

.

JUBAL

Gen.

See C

AINITES

,

JUBILEE,

or JUBILE,

THE

YEAR

OF.

Accord-

ing t o Lev.

a t the completion of seven sabbaths

of years,

.trumpet of the jubilee

is to be sounded

‘throughout the land,’ on the tenth

and procedure.

day of the seventh

on the great day of

atonement.

T h e fiftieth year

announced is to be

‘hallowed,’- Le., liberty

is to be proclaimed every-

where to every one, and the people are to return

‘

every

man unto his possession and unto his family.’

T h e

year in other respects is to resemble the sabbatical

year there is to be no sowing, nor reaping that which

grows of itself, nor gathering of grapes (Lev.

T o

to fuller detail,- as regards real property

(Lev.

the law is that if any Hebrew under

pressure of necessity shall alienate his property he is t o

get for it

a sum of money reckoned according to the

number of harvests to be reaped between the date

of

alienation and the first jubilee year should he or any

relation desire to redeem the property before the jubilee,

this can always be done by repaying the value of the

harvests between the redemption and the jubilee.

T h e

fundamental principle

is

that the land shall not be sold

so as

to be quite cut off, for it is mine, and ye are

strangers and sojourners with me.‘

T h e same rule

applies to dwelling-houses of unwalled villages.

T h e

case is different, however, as regards dwelling-houses

in walled cities.

These may be redeemed within

a year

after transfer but if not redeemed within that period

they continue permanently in possession of the purchaser.

An exception to this last rule is made for the houses of

the Levites in the Levitical cities.

As regards property

in slaves (Lev.

the Hebrew whom necessity

has compelled to sell himself into the service of his

brother Hebrew is to be treated a s a hired servant and

a

sojourner, and to be released absolutely a t the jubilee

(vv.

39-43)

bondmen on the other hand

are to be bondmen for ever

44-46).

T h e Hebrew,

however, who has sold himself to astranger or sojourner

is entitled to freedom at the year of jubilee, and further

is

at any time redeemable by any of his kindred,- the

redemption price being regulated by the number of

years to

between the redemption and the jubilee,

according to the ordinary wage of hired servants

(vv.

2614

JUBILEE

47-55).

I n addition to these enactments Lev.

gives a supplementary

law

regulating the price of

a

piece of land that has been dedicated to God according

to the distance in time between the date of the dedica-

tion and the jubilee year, and also defining the

stances in which such a piece of land in the jubilee

year either reverts t o the original owner or permanently

belongs to

One further reference t o the year

of jubilee occurs in

Nu.

3 6 4

in the law a s to inherit-

ance by daughters,

As to origin, the law is plainly a growth out of the

law of the Sabbath.

T h e foundations of Lev.

25

are

laid in the ancient provisions of the Book

of the Covenant (Ex.

21

23

and in

T h e Book of the Covenant

enjoined that the land should lie fallow and Hebrew

slaves be liberated in the seventh year

Dt. required in

addition the remission of debts (see

S

ABBATICAL

Y

EAR

).

These regulations are in Lev.

25

carried over t o the

fiftieth year and amplified. T h e choice

of

the fiftieth

to

be the sacred year is evidently in parallelism with

the feast of Pentecost which is the closing day after the

seven weeks

of harvest.

A s

to the date

of

the law, this much a t least has t o

be observed, that no evidence of its existence has

reached

us

from

pre-exilic times.

Certainly in

Jeremiah's time the law acknowledged by the prophets

that described in Deut.

15,

according

to which the

rights of Hebrew slave-holders over their compatriots

were invariably to cease seven years after they had

been acquired.

This appears to follow from Jer.

where note that Jeremiah uses the term

17,

cp

v.

8).

Another

passage

is

Ezek.

46

where there is indication

of

a

law according to which

the prince' is a t liberty to alienate in perpetuity any

portion of his inheritance to his

sons

but if he give a

gift of his inheritance t o any other of his subjects, then

the change of ownership holds good only till the year

of liberty

after which the alienated property

returns to its original possessor, the prince.

Now since

Jeremiah

use of the same expression

with

reference to the liberation

of the slaves in the seventh year

it

is

exceedingly probable that Ezekiel also by

means the seventh year.

This view of the case gives additional probability to the

conjecture of

6,

n.

28

d )

and

sen that originally Lev.

25

also had reference to the

seventh year. For the law in its present form proves ( c p

Kue.

on

careful examination to be

a revision of a n

older form which probably belonged to

H.

Thus this

last, besides the injunction about the year of fallow

(Lev,

25

contained also a precept about the year of

liberation

Lev.

by which it under-

stood the seventh year

as

Jeremiah had done.

T h a t in

the year

of jubilee in its present form we are dealing

with a purely theoretical development of the sabbath

idea which was incapable of being reduced to practice

becomes evident from the simple reflection that in the

event

of such a year being observed there would occur

two consecutive years (the 49th and the

in which

absolutely nothing could be reaped, and a third (the

in which only some summer fruits could be ob-

tained, sowing being prohibited in the fiftieth. This

difficulty, which was perceived even by the author of

Leviticus

25

himself (cp

v.

has led many scholars

to make the impossible assumption that the forty-ninth

year is the year of jubilee (so,

Ew.

Ant.

375,

and Saalschiitz,

Arch.

following older writers such

as Scaliger, Petavius, and others).

In

order to

the difficulty Riehm

regards the com-

mand about the land lying fallow a s one that was

originally foreign to the law

of the year of Jubilee and

one that was never in force. This last character, how-

ever, belongs to the whole institution, not merely to

this particular part of it.

For the post-exilic period

2615

Deuteronomy.

.

also

have evidence of the non-observance

of

the

law.

T h e Talmudists and Rabbins are unanimous that

although the jubilee-years were reckoned they were not

observed.

As

regards the meaning

of

the name

or

simply

or

or

authorities are not agreed. According to Josephus

( A n t .

it

means

but the use

of

the

word

Ex.

19

Josh.

6

5,

makes it probable that the name

is de-

rived from the trumpet sound

with

which the jubilee

was to

be

proclaimed ; and it is not impossible that

the

old Jewish

tradi-

tional view

is

right when it says

that

means a

ram-for which

there

is a

probable confirmation in

then,

abbreviation for

a trumpet

of

ram's

horn.

See Dillmann

on

Ex.

would

thus mean the year that is

ushered

in

by the blowing

of

the ram's horn (Lev.

25

For

the earlier literature

see

Ex.

Winer,

art.

and

PRE

art. 'Sabbatjahr.

Recent

are Saalschiitz

2

Ew.,

A n i .

Wette

('64)

Keil

art:

'

Sabbatjahr,' in

; Riehm,

art.

Benzinger H A

474

Nowack, H A

2

W.

R.

B.

JUCAL

JEHUCAL.

JUDA,

RV

Judah,

City

of

(Lk. 139).

See

JUTTAH

JUDA

[Ti.

WH]),

I

.

Mk.

63,

RV

J

UDAS

3.

Lk.

3

30

RV

J

UDAS

4.

Lk.

RV

etc., cod.

87

V ;

Ti.

in

in Ezra and

in

Dan.

and Dan. [Theod.]

in

Macc.

as

well a s

in

we find both

and

T h e

name of the region occupied by the reorganized Jewish

community

in

the Persian, Greek, and Roman periods,

hut extended by Lk. to the whole of W . Palestine (Lk.

4

44

23

Acts

2

10

37

etc.

).

T h e limits of

as

a province varied a t different

periods.

I n the time of Jonathan the Maccabee

)

three tetrarchies of Samaria

[see

E

PHRAIM

,

L

YDDA

,

and R

AMATHAIM

) were added to

Judzea

(I

Macc.

10

30

11

34)

Judas himself had

already expelled the

from Hebron

(I

Macc.

5

65).

According t o Josephus

3

ex-

tended from

now

Berkit

p. 48) in the

N.

to a village called

Jordas

near Arabia on the

and from

Joppa on the W . to the Jordan on the

E.

T h e sea-coast,

a s far

as

Ptolemais

with the exception of Jamnia

and Joppa, belonged to

and according to Ptolemy

(v.

some districts beyond Jordan.

T h e latter

statement, however, is not to be adduced in illustration

of Mt.

19

I

the borders of

beyond Jordan

because here Mk.

10

I

(Ti.

W H ) contains the obviously

correct reading,

' t h a t is,

[first of all] the region beyond Jordan (cp Mk.

11

I,

' u n t o Jerusalem and unto Bethany').

I t should be

noticed, too, that Josephus mentions no trans-Jordanic

toparchy.

On

the death of Herod, Judaea, with

Samaria and

fell to the lot of

as

ethnarch

but on Archelaus' deposition his territory was

annexed to the Roman Province of Syria (see I

SRAEL

,,

89). In the fifth century

became part of the

division called

Four

of

the eleven

toparchies mentioned

Josephus

Eusehius are referred

to

in the

Talmud

and

Daroma,

corresponds

to

the

(see

Onk, Dt,

had

for its centre

Lod or

Lydda, so that the name

Daroma

is often used

in

the

Talmud

nstead

of

Lod. The

limited

the

application

to

a

place

Daroma

of

the Crusaders. The meaning

the

other names

is

clear.

T h e

table-land is otherwise known a s the

hill-country of Judah

but

is not confined ta

Z

ACHARIAS

,

I

O

.

[Ti. WH]) Lk.

3

RV

JODA.

As in

Hastings'

DB 2 792 a.

JUDAH

JUDAH

this high region

there are districts outside of it which

can boast of more varied scenery and of hardly less

historical interest.’

There is first that wonderful de-

pression which bounds

on the E.- the lower

Jordan valley and the Dead Sea, beyond which rises

the precipitous wall of the mountains of Moab.

T h e

three. roads into Judaea on this side start from the three

oases, Jericho, ‘Ain

and ‘Ain Jidi.

Next, the

border must be studied, not,

.however, here, but in dealing with that extensive and

but lately explored region-the N

ECEB

Then,

for the

boundary we have-ideally the

ranean- but really, except at intervals, the edge of the

great plateau itself. The low hills of the

[low-

land] are separated from the compact range to the

E.

by a

long series of valleys running

S.

from Aijalon. This is

western barrier of the hill-country.

I t is penetrated

by

a

number of defiles, which provide excellent cover

for defenders, and opportunity for ambushes and sur-

prises.

T h e importance

of

Beth-zur (cp B

ETH

-

ZUR

,

K

IRJATH

-

SEPHER

) arises from the fact that it is the one

fortress on the,

W.

flank of

S.

of Aijalon,

which the physical conditions make possible.

I n

conclusion, the last ten

of the

plateau

on

t h e

north

form

a

frontier which was the most accessible

s i d e of the

territory, but was well protected by

the fortresses of Benjamin.

See further, J

U D A H

;

N

EGEB

, S

HEPHELAH

,

P

ALESTINE

.

JUDAH

Ass.

I

.

Judah

the eponym of the tribe of

Judah, is represented a s the fourth son of Jacob by

J ex-

‘*

plains the meaning thus, ‘And she said,

Now will

I

praise Yahwk

therefore she called his

n a m e Judah (Yehudah)’ the saying in Gen.

498

starts

from the same

W e

presume, however, that the name (like Isaac, Jacob,

and Israel) is a popular adaptation of some fuller

perhaps Abihud

or

Ahihud (whence Ehud).

I t does

n o t ,

so

far a s we know, occur in the Amarna tablets.

indeed, thought we might read it in

a letter

of

Rib-addi of

( A m . Ta6.

no. 8642) but Winckler

reads here Jada.

One of the most striking characteristics of J is the

interest which this writer,

or

school

of writers, takes in

Judah.

That in J Judah takes the place

assigned to his brother Reuben (closely

connected with Judah, see

3)

in

E

in

t h e Joseph-story, has been noticed elsewhere (see

J

OSEPH

3).

According to Gen.

38,

Judah went t o

Adullam

(?)

and married the daughter of a Canaanite (?)

n a m e d Shua

his three sons were called, Er,

Onan, and Shelah. T h e first-born was married by Judah

Tamar

but E r and

were wicked, and were

by Yahwk.

As Tamar was not given to the third

son Shelah, she found a n expedient to become the

mother of two sons, Peres (?) and Zerah, by Judah.

T h e other legends relative to Judah (Judges, Samuel)

will b e most conveniently referred to in

3.

T h e

genealogies of Judah in

I

Ch.

41-23

will not be con-

here.

There is indeed much to reward

a

critical

examination of the puzzles which they contain but t o

condense the results of the special articles in a really

fruitful way would occupy too much space. See as

specimens,

C

HARASHIM

,

J

ASHUBI

-

LEHEM

,

S

HOBAL

.

I t is usually thought that by

a

special piece

of

good

fortune we have in the legend

of

Gen.

38,

just now described, a tradition respecting

the

development of the tribe of

Judah.

Reading the passage ethnologically we learn

H

I L L

COUNTRY

OF

B

ENJAMIN

, J

O R D A N

,

For

the gentilic see J

EW

.

Leah, born at

(Gen.

29

35).

See

GASm.

chap.

13.

Wildeboer,

that Judah had established itself on the

W.

side

of

the

Hill Country of Judah

in the district of Timnah and

Adullam, that the tribe allied itself to the Canaanites, but

did not flourish till it united with the tribe

of Tamar, which

dwelt more to the

to

however, the story records in legendary form the con-

quest of Baal-tamar, where was the sanctuary of the

original tribe of

Benjamin,

b y David, the leader of the

Baal-tamar, he thinks, was the place

afterwards called, by a strange distortion of the name,

This brings

us

face to face with more

than one deep and difficult problem which this scholar

has treated in a strikingly original manner (see

J

EARIM

,

S

AUL

, T

AMAR

).

W e shall return to Gen.

later

4,

end) it is enough here to repeat that Tamar

a word which in some other passages too has arisen

through textual corruption) a s

a woman‘s name is most

probably a corruption of some popular shortened form

of

just

as

‘Ir

( E V ‘ t h e city

of

palm-trees

in Judg.

is probably a corruption

of

‘Ir jerahme’el (see J

ERICHO

,

I t was union with

the Jerhameelites ( a tribe of Edomitish affinities) that

gave

to the clan or tribe of Judah

a

similar

cause seems to be assigned for the expansion of the

Jacob-tribe (see J

ACOB

,

3),

and also for the growth

of the Isaac-tribe, Abraham representing the

of

Rehoboth, Sarah the Israelites

or

perhaps

Jizrahelites (see

JACOB,

6).

In the earliest times

indeed Judah, Jerahmeel, Caleb, Kain (Kenites), and

must have closely resembled each other, and

probably we should add to the list Reuben, which (cp

Gen.

I

Ch. 4

I

53)

had clans closely connected

with those of Judah.

It was not therefore altogether

unnatural for the editor of Judg.

to ascribe to

Judah the conquest of Hebron

or

rather

and of Debir’ or rather Beth-zur

(see

S E P H E R

) ; in reality these were the achievements of

C

A L E B

which did not become one with Judah

till the time of David.

(On Judg.

see K

ENITES

.)

All the tribes mentioned, including Judah, seem to have

adhered for a long time to a nomadic or semi-nomadic

mode of life a large part of the Jerahmeelites remained

late (see

A

MALEK

, H

A M

J

ERAHMEEL

,

S

AUL

). I t may be remarked here that Reuben

see R

EUBEN

) very possibly derives its name from

Jerahme’el.

T h e leader who brought about, a t least t o a consider-

able extent, the union of these different clans

(so far a s

they were in his neighbourhood a t the time

of his operations) all of which were outside

the Israelitish territory, was David.

T h e steps by

which he reached his proud position a t the head of a

great inland

kingdom require renewed in-

vestigation.

H e was himself probably a Calebite of

Bethuel or

Debir

or

SEPHER

His sister Abigail bears the same

name as the former wife of Nabal, which probably is

really a tribal n a m e ; this might suggest that David’s

family was aware of a connection with another family

called Abigail (or Abihail) settled near Carmel

Jerahmeel) and Jezreel (cp D

AVID

,

I

,

n.

S

AUL

,

4,

and see below), though it is true that Abigail and

Abihail are ultimately traceable to Jerahmeel.

If

so,

like his sister, David strengthened the connection with

Jezreel by marriage (see N

ABAL

).

In spite

of

all this

neither Caleb nor Jerahmeel supplied the name of the

great tribe produced by a combination of smaller tribes

-but Judah.

N o doubt Judah had already been

extending its influence (cp Gen.

so that David only

recognised and acted upon accomplished facts.

was at first only

a

small Jndah that accepted David

as

its leader and prince (cp

I

where note that

the conquest of ‘ H e b r o n ’

or

rather

is

presupposed), nor can we say with documentary

Cp

Wildeboer,

JUDAH

JUDAH

how David became possessed of the territory

between the original southern border of Benjamin and

the northern limit of the Negeb (see N

EGEB

).

W e

need not therefore hesitate to accept Winckler's very

plausible view that the present narrative of David's

adventures during his outlaw period

is based upon

earlier traditions of a struggle on David's part for the

possession of the later Judahite territory.

Winckler's

interpretation of the details will of course be liable t o

criticism, partly from the

difficulty of the

historical problems, but chiefly from the fact that his

textual criticism is not as thorough and methodical a s

could be wished.

According

to

Winckler the Cherethites'and 'Pelethites' are

those semi-nomad

gentes of

the Negeb

to

which David by his

origin belonged their chief town was Ziklag from which as a

centre they went

about

making raids under

leadership.

This can hardly be accepted. Though temporarily

on

friendly

terms with the Cherethites and Pelethites David

(a

searching

sm suggests) wasafterwards

at

war with these tribes

confederations of clans) a t

a

later time again he made

with them (see

Nor does the text

favour the view that Ziklag' was the

chief

town either

of

the

'Cherethites' or

of

the 'Pelethites.'

Winckler is

also

of

that in the present narrative of David's earlier career (which is

admittedly ofcomposite origin) there have been brought together

two widely different legends, one of which gave Adullam (a place

,in the later Judahite territory)

as

David's original base of

operations, and the other 'Ziklag' in the land of

(see

to

which region Achish (who is represented

as

having been for

a

time David's liege lord) must

also

have

belonged. Of these two traditions the latter, Winckler thinks,

is the original and sole authentic one.

Independently the

present writer has arrived a t similar but much mnre

conclusions on certain points, and the same method which has

him to reach greater definiteness on these points has

led him

to

conclusions

on

oints of detail which seem adverse

to

other parts of Winckler's

As we have said, David was probablynot ( a s Winckler

represents) a

but a Calebite

not

Ziklag'

but Debir (see above) was his home.

W e

cannot put

on one side the Bethlehem-tradition quite a s

readily a s Winckler does.

Beth-lehem must spring

from some more possible name

that name

is

found-

it

is

Bethuel.

I t may be left

an

open question, however, whether both Beth-

lehem and

(or Bethel) are not broken down forms of $

primitive

This would account for Ephrathite

I

S.

17

on which name

Jerahmeelite) see

Similarly, though Adullam is certainly not David's

true starting-point, the name did not spring from the

brain of

a tradition-monger

Adullam,' may

be a corruption of

Carmel.

Carmel was

a

region friendly to David's family it is surely a plausible

view, that David, if he was a native of Debir

sepher), and closely allied with the clans of Jezreel and

Carmel, took Carmel as his earliest base of operations.

Nor

is there any inconsistency between this tradition

and the Ziklag tradition. Until David gave practical

effect to his aspiration after the imperial throne of an

expanded Israel there was no reason why he should not

be on the most friendly terms with the chieftains of

tribes like the

'

Cherethites and

Pelethites.'

There is a striking little narrative in

I

S.

which

throws some light on this (and

so

indeed, rightly under-

stood, does the story in Gen.

38).

From the fort (not

cave) of Carmel (not Adnllam) David, we are told, took

his father and mother to Mizpeh of Moab (rather to

Migrephath of

see

and confided

them to the care of the king or, as we might say,

chieftain (see K

ING

).

There his parents found a safe

asylum, all the time that he was in the fort

of Carmel.

I t should be noticed that Carmel is already

a

Judahite

place.

'Abide not in

(read, not

but

depart, and get thee into the land

of

Jndah, says Gad the ' p r o p h e t ' (see G

A D

So

David leaves Musur, and proceeds to the fort of Carmel

(

Adullam

see H

ARETH

.

W e must now return to Gen.

38,

assuming here the

corruptions of the text mentioned under

A

ZOPHIM.

Judahite family settles at

(not Adullam).

A

fusion with the Maonites was attempted, but had less

prosperous results than a Jerahmeelite alliance.

T h e

two clans which arose in consequence were called

respectively

and Zerah.

This seems to be a

record of the friendly intercourse between David when

a t Carmel and the

of Sarephath.

W e conclude then that David made Carmel his base

of operations for the conquest of territory for an

H e established

himself for

a

time in

but found it

necessary to retire, first to the wilderness of

Ziph, and then to that of En-kadesh (not En-gedi

see

K

ADESH

), where he was certainly in the land of

From Kadesh we may presume that he made his way

to

by favour of whose chieftain

Achish, or perhaps rather Nahash

(who, be it noted,

worships

I

S.

he found new headquarters

at

(see

I t was from this place that

he obtained his great warrior Benaiah (see J

EKABZEEL

)

and raided those parts of the Negeb which did not

belong

to

the Rehobothites and Zarephathites.

Mean-

time the Zarephathites were doing great mischief t o

kingdom by their incursions (cp especially

I

S.

and, if our treatment of the text is sound,

Saul met his death bravely struggling with them on the

ridge of hills near Carmel or Jerahmeel (see S

AUL

,

4).

I t is possibly to the following period that David's acquisi-

tion of a chieftainship in the Carmelite district is to be

assigned; this helps to account for his elevation to a

greater position a t Hebron

(the reading

Hebron

may be safely accepted).

This, however, was not

agreeable to the Zarephathites, and

a

fierce conflict

broke out between them and the new-made king.

David, however, became the

Gob and Gath

in

21

15-22

being corrupt fragments of Rehoboth,'

and

'

Rephaim

and

Baalperagim in

S.

5

of

and

respectively

see also Judg.

After this, the Rehobothites and

the Sarephathites became David's faithful servants

in

this character their names have come down to

us

a s

'

Cherethites

and

Pelethites.'

See P

ELETHITES

,

R

EHOBOTH

, Z

AREPHATH

.

It required doubtless a harder struggle t o overcome

the resistance of Abner, the general of Ishbosheth (or

rather perhaps Mahriel; see M

EPHIBOSHETH

,

I

),

whom Winckler, perhaps rightly, regards a s having

been in the first instance king of

all Israel

S.

2

T h e conquest

of J

ERUSALEM

was the neces-

sary preliminary of this.

Being taken by David himself

from the Jebusites, it formed originally no part of the tribe

of Judah but its possession secured the

of

the family of David on the throne of Judah, and in

Josh.

it is represented a s half-Judahite,

half-Jebusite.

On Solomon's supposed exclusion of

Judah from the departmental division of his kingdom

see

S

O

LOMON

,

T

AXATION

,

and

cp

Kittel on

I

K.

T h e tribe of Judah is referred to twice in the N T

(Heb.

Rev.

7 5 )

but the references require no

comment.

T h e isolation of Judah is its most notable geographical

Note that Timnah

is mentioned in Josh.

55-57

in

the same group with Maon, Carmel, and Ziph (which name

underlies Chezib in Gen.

38 5).

He was probably 'prince of

(

I

253,

crit. emend.).

See

3

The supposed reference

to

David

as

'head

of

Caleb' after

he had removed to Hebron can hardly be

(see

N

ABAL

).

Tradition rightly describes him as a

('king,'

chieftain

').

4

This may he implied too in the story

of

and

the

(Rehohothite) in

6 .

Perhaps

too

of

S.

should rather

(cp

R

EHOBOTH

,

and see Crit.

In this connection it may be noted that in the earlier and

much briefer story on which

I

S. 17 is probably based, Goliath

of

Gath' was probably 'Goliath of Rehoboth,' 'the valley

of

was 'the

of Jerahmeel,' and

was

'

enlarged tribe of Judah.

2620

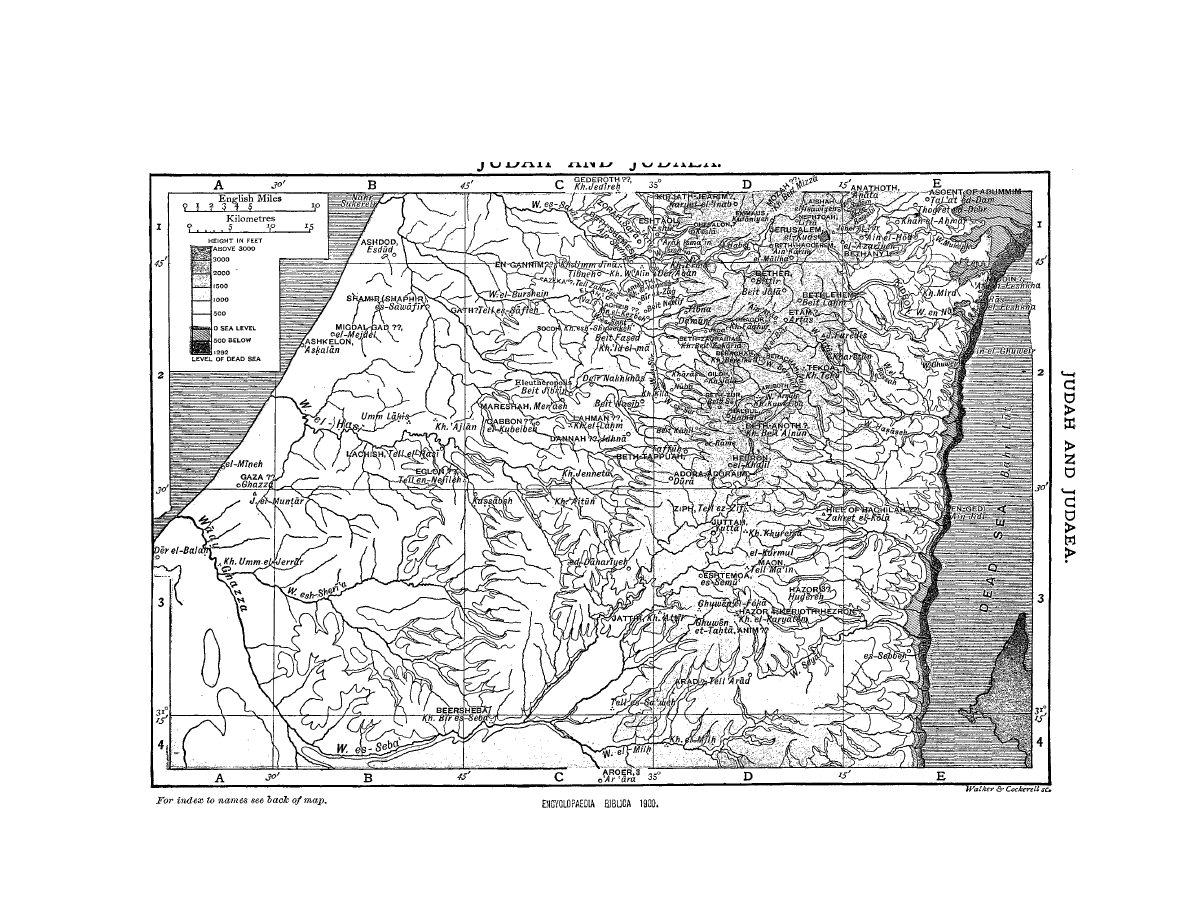

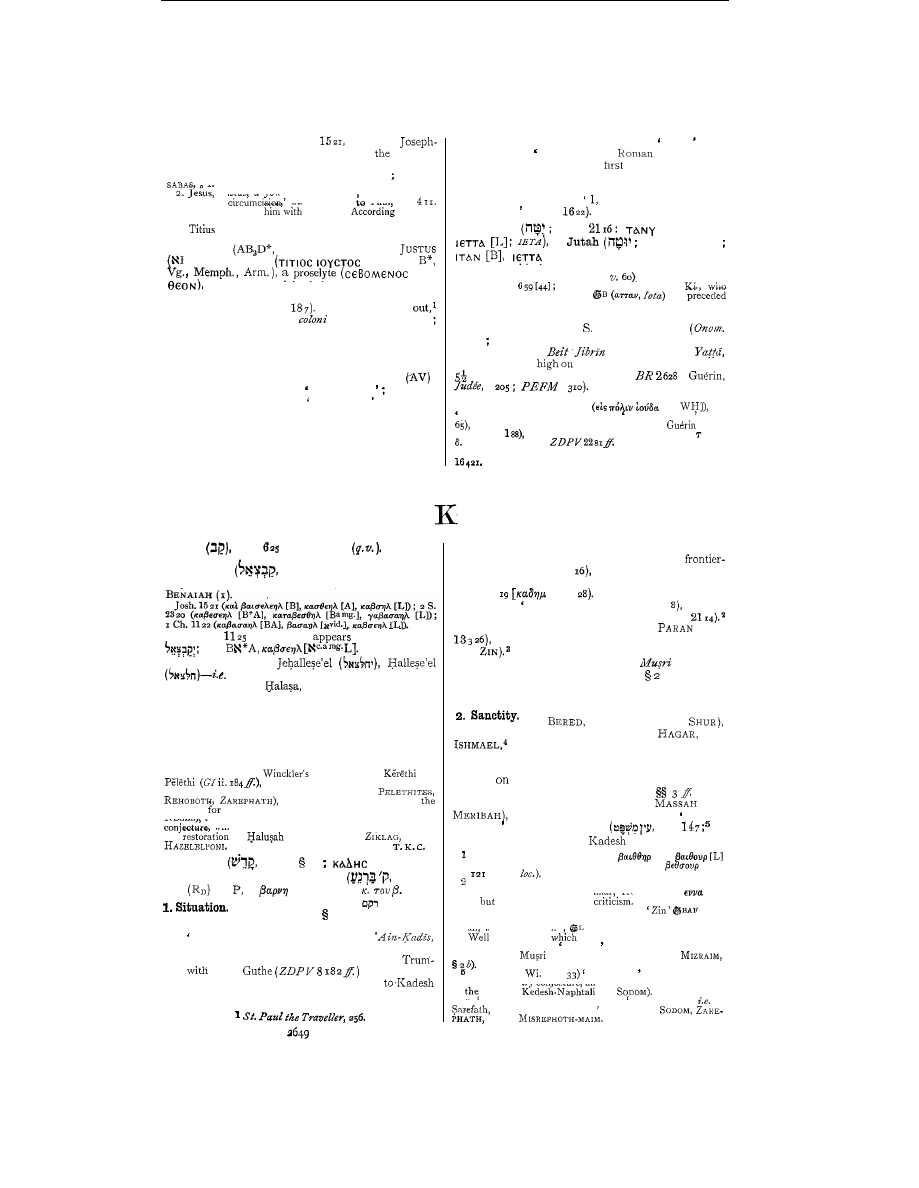

MAP OF JUDAH AND JUDEA

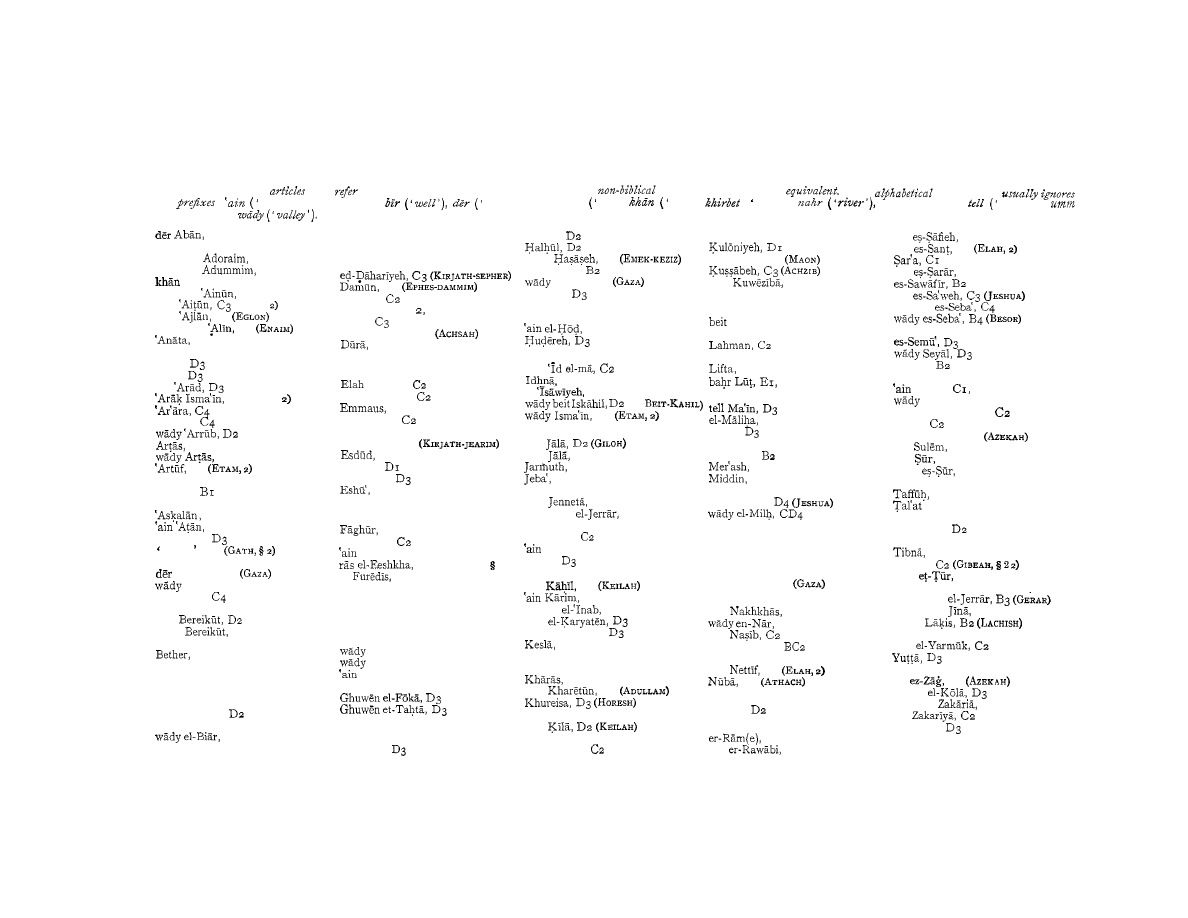

I N D E X T O NAMES

Parentheses indicating

that

to the place-names are in certain cases added

to

names having no biblical

T h e

arrangement

:

spring’),

beit

( ‘

house

’),

monastery ’),

ed-,

el-

the

’),

inn

’),

(

ruin

’),

viis

( ‘

summit

’),

mound’),

(‘

mother’),

D z

Achzib, Cz .

Adora or

D z

ascent of

E

I

el-+mar,

E r

(A

DUMMIM

)

Kh. beit

D z

Kh.

(E

TAM

,

Kh.

Bz

Kh. wady

Cz

E r

Anathoth,

E

I

Anim,

Arad,

tell

D

I

(E

TAM

,

Aroer 3,

Dz

D z

(E

TAM

,

I

)

C

I

Aruboth, D z

Ashdod,

Ashkelon,

Bz

Bz

Dz

(E

TAM

,

I

)

Kh. ‘Attir,

Azeka ? C z

el-Balah, A3

el-Bassah, E z

(B

ETH

-

BASI

)

Beersheba,

Berachah (Valley), Dz

Kh.

wady

D z

Beth-anoth, D z

D z

Beth-haccerem, D

I

Bethlehem

I

,

D2

Beth-shemesh, C

I

,

2

Beth-tappuah, Dz

Bethzacharias,

Beth-zur, D z

D z

(C

ONDUITS

)

Bittir, Dz

Cabbon, Cz

Chesalon, D

I

Dz

Dannah,

Dead Sea, E

I

,

3 , 4

Debir,

Kh. ed-Dilbeh, Cz

Dz

Eglon, BC2

(Valley),

Eleutheropolis,

D

I

En-gannim,

En-gedi, E 3

Kh. ‘Erma, D

I

B

I

Eshtaol,

Eshtemoa,

D

I

Etam? Dz

D z

beit Faged,

(E

PHES

-

DAMMIM

)

el-Feshkha, Ez

Ez

(D

EAD

S

EA

, 3)

J.

D z

(B

ETH

-

HACCEREM

)

Gath, Cz

Gaza, Az

Gederoth, D r

Ghazza, A2

Ghazza, A3

(G

ERAR

)

Ghuweir,

E2

el-Ghuweir, E z

Giloh, D z

el-Habs, D

I

Hachilah,

Halhul,

el-Kuds, D

I

wady

E z

tell el-Hasi,

el-Hasi, Bz

Hazor 3,

el-Kurmul, D 3

Kh.

D2

(A

CHZIB

)

Lachish, Bz

Lahm, D z

Kh. el-Lahm, Cz

Hazor 4, D3

Hebron, Dz

E

I

(E

N

-

SHEMESH

)

Laishah, D

I

D

I

2,

3,

4

Kh.

(A

DULLAM

)

C2.

el

D

I

(see

D

I

D

I

(M

ANAHATH

)

Maon,

Mareshah, Cz

el-Mejdel,

Cz

E z

beit

Kh.

Dz

Cz

Dz

Kh. Jedireh, C

I

Kh.

Cz

Kh. umm

A3

Jerusalem, D

I

beit Jibrin,

(E

LEUTHEROPOLIS

)

Jidi, E 3

Juttah,

beit

Dz

D

I

Karyat

D

I

Kh.

Kerioth-Hezron,

D

I

ain el-Kezheh, Cz

el-Khalil, Dz

Dz

(H

ARETH

)

Kh.

Dz

Kidron,

Ez

Kh.

Kirjath-Jearim, D

I

el-Kubeibeh,

Migdal-gad, Bz

Kh. el-Milh,

(A

RAD

)

el-Mineh, A2

Kh. Mird, Ez

Kh. beit Mizza, D

I

Mozah, D

I

W.

Mukelik, E

I

J.

el-Munfar, A3

deir

Cz

(I

R

-

NAHASH

)

E z

beit

(K

EILAH

)

tell en-Nejileh,

Nephtoah, D r

beit

Cz

D z

Phagor,

D z

W.

E

I

(B

AHURIM

)

tell

Cz

W.

Cz

W.

C

I

(B

ETH

-

SHEMESH

)

tell

Kh. bir

es-Sebbeh, E 3

(T

HE

D

EAD

S

EA

)

(T

HE

D

EAD

S

EA

)

Shamir,

Shaphir, Bz

Shems,

2

esh-Sheri‘a, AB3

Kh. esh-Shuweikeh,

Socoh,

nahr Sukereir, B

I

W.

D E

I

(A

NATHOTH

)

beit

D z

wady

D2

(K

EILAH

)

D z

ed-Dam,

E

I

Tekoa, Dz

Kh. T e k b ,

Thogret ed-Debr,

E

I

(D

EBIR

)

D z

Tibneh,

jebel

D

I

Kh. Umm

Kh. Umm

C2

Umm

Kh.

bir

Cz

Zahret

Kh. beit

Dz

tell

tell ez-Zif,

Ziph, D 3

Zorah, C

I

JUDAH

JUDAH, HILL-COUNTRY

O F

course,

consult

the histories

of

Israel,

not

forgetting

the most

recent-that of

Winckler,

to

some of

whose

conclusions the

above

article

gives a n

independent

support.

b. Senuah, Neh.

11

doubtless

same

as

3.

A

Levitical family, according

to

the

of

I

[A]).

Here,

some would read

no.

the

original

name was

H

ARODITE

).

See

G

ENEALOGIES

i.,

7

4. A

Levite (the

above

clan

I

Esd.

9

(JU

D

AS

,

5.

A

priest's

son,

Neh.

12 36

(om.

BNA).

JUDAH,

HILL-COUNTRY O F

T. K.

c .

RV Josh.

11 20

7

21

Ch.

27

4,

and virtu-

ally Josh.

15

48

18

Judg.

1

Jer. 32

44

33

13,

or,

OF

(Lk.

1 6 5 ,

is the

special term for

a well-defined region to the north of

what was called the

some

25

miles long by

12

t o

17

broad, and from

2000

to 3000 feet above the

sea.

Under the title of

it forms the ninth

of

toparchies.'

It has for its centre the

ancient city

of

H

E B R O N

, between which and the Negeb

there is

a fertile plateau,

9

miles by

3,

which forms

a strong and agreeable contrast to the

table-

land in the north.

It is of this table-land that

travellers think when they speak

of

as

a stony

desolate region.

Apart from some breaks in the

plateau, which enjoy

a rich vegetation, such

as

Bethany,

the Valley of Hinnom, 'Ain

the W a d y

(see C

ONDUITS

,

3),

the valleys near Bethlehem, and

especially Hebron, the thinly covered limestone pro-

duces

a

very dreary effect ; one cannot help pitying the

few dwarf trees which wage

a doubtful struggle for exist-

ence with the boulders around them.

Nevertheless the austerity

of

this region

was

not

always

nearly

so

unmitigated

;

it did but

call out the

art

and

energy

of

man to counteract

it.

By

a

trained

historic imagination

we

can

recall

some of

the

vanished

glory the

traces

of

which,

indeed,

are

multitudinous. One

may

for

miles

in

perfect

solitude in

a

country of sheep and goats.

But the hills

are

crowned with ruins, and the sides of

the

hills are terraced,

and

by the

fountains

are

fragments of

walls

and heaps

of

stones which

indicate

the ancient

homes of

men.

T h e greatest elevation in the hill-country of Judah is

attained by the.

ft.), which ter-

minates

a mountain-ridge between Halhiil and Hebron.

T h e chief valleys are the WBdy Halil, which is joined

by the valley

Hebron, and beginning

NE.

of

Hebron,

first southward, then south-westward, and

finally unites with the WBdy el-Milh (coming from the

east), forming the

W N W . from

Hebron begins the

el-Afranj, which runs N W .

to join the

a t Ashdod.

This is probably

the 'valley

northward from Mareshah'

Ch.

1410

see Z

EPHATHAH

) where Asa

is said to have

defeated the Cushite invaders.

Farther south

the

broad and fruitful

which first of all runs

north, then turns westward, and

the name of the

WBdy

(see

V

ALLEY OF)

cuts through

the

At

(Socoh) is the point of

junction

of the WBdy

and the WBdy en-Najil.

This and other wadies

in

a

remarkable basin about

30 miles

long,

which divides the mountains

of

Judah

from the lower hills of the

Towards the

NW.

this basin is drained by the broad and fertile

which near the coast assumes the name

Nahr

(see

JABNEEL).

Not far from Tekoa is

the great WBdy

where is the ruin called

in the name of which some find an echo of

the Berachah of

I

Ch. 20

26

(see B

ERACHAH

, V

ALLEY

OF).

The Hebrew text

of

Josh. 15

48-60

reckons

as

belonging

to

this region

cities, some of which

can

be identified

with obvious certainty, such

as

Eshtemoli, Beth Tappuah,

Hebron, Maon, Carmel, Ziph,

Juttah,

characteristic.

Its boundaries are given in Josh.

( P )

; but these of course have no

relation to the

period.

T h e N. boundary coincides with

S.

boundary of Benjamin; only it

is

given with

greater fulness.

On the E. the boundary is the Dead

S e a ; on the

W.

the Mediterranean; on the

S.

a line

drawn from the southern tongue of the Dead Sea to the

(rather

see E

GYPT

, B

ROOK

O

F

) ,

and passing by the ascent of Akrabbim,

and other places (consult

ADDAR,

H

EZRON

, K

A R K A A

) .

T h e idealizing tendency

of

P

comes out in his inclusion of

within Judahite

territory.

There

is a n inconsistency with regard to

which Judg.

and Josh.

make

Judahite, whilst Josh

18

apparently assigns it to

Benjamin (cp

also with regard

to

J

ERUSALEM

It should be noticed that in

the earlier narratives we hear

of

(Judg.

and

A

DULLAM

(

I

see above), or rather Carmel,

as

belonging t o Judah we also read of

a Negeb of Judah

( I

27

IO

see N

EGEB

).

T h e natural divisions of the

territory are-the N

EGEB

, the

S

HEPHELAH

,

and the

Wilderness of Judah (see D

ESERT

,

a n d

3

I t

is urgently necessary to get

a

clear idea of each of these

without which the

significance of many

passages

will he

As to the names in Josh.

15

reference

must also be made to special articles.

Some progress

has doubtless been made in settling the readings (which

in

M T

a r e often incorrect), and consequently many

current identifications have not improbably been

in the present work with effect but much uncertainty

still attaches to many

of

the details (see

the names

of places

on the

S.

boundary).

Judah is not to be blamed for indifference to the

great struggle celebrated in Judg.

5

a

tribe of Judah

I n Dt. 337 (in

the Blessing

of

Moses

'),

however, we meet

with

a

prayer that

would bring Judah ' t o his

that the great schism might be healed,

and Judah

into the people

of Israel

it

is the saying of

a

N. Israelite.

T h e Blessing of Jacob

499

11

celebrates the fierceness and victorious

might of Judah and a t the same time its appreciation

of

the natural advantages of its land (Judah was

a

vine-country c p Joel

1

7

3

[4]

18

Ch. 26

IO,

a n d

H

EBRON

,

3).

Later history exhibits this tribe

as

tenacious, conservative, and even

perhaps not wholly unconnected with its Edomitish

a n d N. Arabian affinities.

T h e two Blessings' just referred to

are

the only

pre-exilic poetical passages in which the name

even in the exilic a n d post-

exilic poetry it is very rare.

Among the

prophets it is Jeremiah who uses the term

most frequently, though

abundance

of interpolations

in his book makes it difficult to estimate the exact

numbers.

The examination of the historical books

leads t o some interesting results.

T h e phrase

occurs in Judg.

16

S.

212

I

Ch.

316

Dan.

1 6 ; also

Ob.

12.

But some of these occurrences are of small

account, being due

to

glosses, and

S.

is strongly

corrupt (see J

ASHER

, B

OOK O

F,

T h e phrase

is not much commoner.

is, of

course, frequent.

According to

it may be

inferred from the use of Israel and Judah in passages

like

2

S.

3

IO

11

1

1

and

I

K.

that there was

a

sense of

the inner opposition between north and south before the

separation of the kingdoms.

The above article

on

a subject of great difficulty sums

up

some of the chief results of special

articles.

The reader will, of

did not at that time exist.

On

IO,

which seems to interrupt the connection, see

des

Test.

in

the list

of

Jos.

(B3

En-gaddi

is the

corresponding

name.

Schick

83

ventures

to

suppose

a

confusion between En-gedi and

2622

2621

JUDAH,

KINGDOM

O F

JUDAS

There are

also,

however, places which are omitted in

MT, but have an undeniable claim

to

be included in the list

;

and

after Josh.

15 59,

actually gives eleven names which (see

Di.) must have belonged to the original list. All the cities

mentioned here by

lay no doubt, immediately south

of

Jerusalem; among them

the well-known places Tekoa,

Bethlehem,

(see B

ETH

-

HACCEREM

) and Bittir (see

JUDAR, KINGDOM

OF.

JUDAR,

PROVINCE

OF

Ezra

5 8

RV,

AV

. .

,

See

JUDAH UPON

AT] JORDAN

t h e eastern limit of the territory of Naphtali (Josh.

19

34

o

o

that

a

district in the N. by the Jordan belonged t o

Judah.

Evidently the text is corrupt. Read

and

(reaches) to the Jordan (Gra.

).

This was written twice,

a n d one of the 'Jordans' was wrongly emended into

Jndah.'

For

a

similar case in the Gk.

of

Jn. 325 see

J

O H N

THE

B

APTIST

,

6.

Ewald

(Hist.

would read

'(reaches) to

Chinneroth of Jordan and interpret

this

phrase on the analogy

of the phrase all

in

I

K.

15

as meaning the W.

shore of the Sea of Galilee (see

Another sug-

gestion is to emend

into

'(to) the side

(of)';

cp

Neub.

224.

is satisfactory.

T.

K.

C.

JUDAS

the

Gk.

form

of the Heb.

See I

SRAEL

,

28-45.

TUDAH

I

. I

9

see

4.

2

4),

see M

ACCABEES

i.,

4

; called

[A in

I

Macc.

4

The third son of

called

( I

Macc.

of Chalphi, called

in

I

Macc. 1381,

a

Jewish

general under Jonathan

(

I

Macc.

1170).

4.

Son of Simon

( I

Macc.

16

One evidently holding

a

high position in Jerusalem, who

took

in sending a letter

to

Macc.

1

I

O

).

Though identified with the Essene (cp

Jos.

i.

3 5 )

he

is

more probably the same as no.

6.

Lk.

Mt.

1

Judah] ;

see

I

.

7.

Judas

of James

[Ti.

WH],

one

of

the twelve apostles according to Lk.

6

and Acts

though not according to the lists in Mt. and

where

his place is taken by Thaddaeus.

H e is, without doubt,

the Judas not Iscariot

of

the Fourth Gospel (Jn.

who asked Jesus the question : Lord, what is come to

pass that thou wilt manifest thyself unto

us,

and not

unto the world?'

T h e expression ' J u d a s of James' is

most naturally and usually understood as meaning son

of

James'

but it can be interpreted as meaning

'

brother

of

James,' and this is the sense in which it has been

taken by the author of the epistle of J

U D E

Ecclesiastical tradition very early began its attempts to

harmonise the

four

lists of the twelve apostles, and one of the

results (since Origen)

was

the identification of Judas of James'

with Thaddaus; in late Syriac legend he appears

as

Judas

Thaddaeus and is the apostle of Syria and

ulti-

mately suffering martyrdom by stoning

at

Berytus

or

Aradus.

The similar Armenian legend claims him also for Armenia. In

the Roman Breviary (Oct.

qui et Judas

appellatur in

ex Catholicis

is said to have evangelized Mesopotamia and afterwards to have

accompanied Simon the Cananaan into Persia where they

crowned

a

successful ministry by suffering

a

glorious martyrdom

together.

It is worthy of particular notice, however, that the

oldest Syrian (Edessene) legend, which goes back to the

second

(?)

century, identifies Judas Jacobi with Thomas (see

Eus.

113

Jesus was

Judas

sent

to him

Thaddaus the apostle, one of the Seventy').

See M

ACCABEES

8.

Judas, Mk.

63,

see

9.

Judas

o

26

2231,

[Mk.

hk.

6

71

13

not

as TR],

cp

In Jn.

gives

so

in Jn. 124

but in

In

Mk.

D

gives

in Lk. 223

in

Jn.

6

7

Thrice in the Fourth

6 7 1

Tudas is

called the son

which

well be

a genuine tradition.

Also

I

Macc.

8

[A],

and

I

Macc. 4

13

the

2623

latter

a

corruption in the Gk.

As

for

the name

(twice applied to the father

of

Judas, Jn.

6

71

13

there is

a

well-supported reading in Jn.

which, according to Zahn and

confirm;

the view that

and

proceed from the Hebrew

designation

'a

man of Kerioth'; cp

Jos.

Ant.

vii.

1068

We should,

however have expected

suggests that

phrase

D

is derived from

Not understanding

the scribe thought of

'a

palm tree

which bears dates

a

Apart from this, it

is

a

plausible view that

is derived from Ish-kerioth, ' a

man of Kerioth. Such formations of names continued

to

he

used, as Dalman shows,

spite of the predominance

of

Aramaic.

Most scholars consider Judas to have been a native of the

Kerioth mentioned

Josh.

25

;

hut

in this

passage means 'group of places' (see

4)

and the spot or

district intended did not

to

and Well-

therefore prefer the

Korea

(Kerioth) of Jos.

xiv. 3

4,

etc. which was a beautifully situated place

N .

of Karn

Sartabeh (she Z

ARETHAN

). Since however the evangelists

find the name

so

much

is it to suspect that it may have been incorrectly kransmitted

(cp Boanerges Kananaios

Bar-jona) ! If

so,

we may not

un-

reasonably

that the true name is

' a

man

of Jericho.' I t would readily be remembered that one of the

disciples came from Jericho. Cp J

ERICHO

,

7.

We

know, however, that he was one of those whom the

Of the early history of Judas nothing is told

us.

Preacher of the Kingdom

of Heaven drew

to himself by the power of his will to be

'

And he

his companions and assistants.

goes u p into the

and

to

him whom he himself would, and they

unto him

'

(Mk.

3

13)

the

assures

us

that every

one

of the persons named was specially chosen by Jesus.

Twelve are named

three lists of the twelve are given,

and in each of the three Judas stands last (Mt.

Mk.

Lk.

see

A

PO

STLE

,

I

). Mt. and Mk. add,

'who also betrayed h i m ' ; Lk. adds, 'who became

traitor'

I n

the lists of Mt. and

of Mk. the eleventh, and in that of Lk. the tenth, is

called

6

or

Farrar has

offered the conjecture that this Simon was the father of

Judas Iscariot, and it is certain that in Jn. (see

I

)

Judas Iscariot is called the son of Simon.

I t is not

likely, however, that both father and son would belong

to the Twelve, and Simon was

a

very

name,

whilst

is very possibly a corruption of

(

a man of Cana'), which would make this Simon a

that we can say is that Simon and

Judas were probably companions whenever the Twelve

were sent out by two and two (Mk.

6

7).

There is no list

of the Twelve in the Fourth Gospel.

In

however, we receive early notice that Judas

-

-

Notice in

Iscariot was one of the Twelve, and

that it was he who was destined to

deliver

up Jesus (Jn.

6

71).

The notice

is suggested by

a

saying ascribed to Jesus

(v.

70);

'Have

chosen yon twelve, and one of

you

is

a

devil

It adds hut little, however, to the historical weight

of the Synoptic tradition, and the saying in

v.

70

appears

to

he

inconsistent with the equal confidence in

all

the disciples shown

Jesus according to the Synoptic tradition-a confidence

which is maintained unbroken till the last paschal meal.

T h e Fourth Evangelist further tells

us

(Jn. 124-6) that

t h e destined traitor murmured at Mary's costly gift

of

love a t Bethany, when she took a pound of

S

PIKENARD

and anointed

the

feet of Jesus he also mentions

a s the secret cause of this murmuring of Judas that he

was a thief, and having the box took away what was

put therein.'

So

at least the traditional text must be interpreted

but the phraseology is very awkward, and it

strange that

this habit of pilfering should be mentioned unless it were

to

Zahn,

2

561

Nestle,

Sacra,

14.

the

controversy between Nestle and Chase,

T

(9 140

189

240

'97

Jan. Feh Mar.

'98.

Dalman,'

3

.

Keim,

von

2

So

BDQL, etc.;

a purely literary

correction,

Jn.

The

and

Bakhuizen,

is not satisfactory.

2624

JUDAS

JUDAS

account for the

smallness of

the sum which (Mt.

at

least

says)

Judas

to

betray his

master.

It wouldseemthat here there

a

clear

case of

corruption, and that

a

very

early

editor

of

the

text

may

have miscorrected

the

corrupt passage before him.

Very

possibly

we

should read

he

was a

harsh

man

and used

t o

carry the common purse’

as

Prov.

The

statement about Judas is therefore worthy of

credit than

it

has sometimes received

from

advanced critics. It

may

be

nearer

to

the oldest tradition than the

vaguer

statement of

Mt.

Mk.

144.2

Weiss

2

443)

cannot account for the imputation of

thievish

intentions to Judas

in Jn.

except

on

the theory that the

apostle

John had found out thefts committed hy the greedy

Judas, and Godet speaks of

some one

who has accused John of

a

personal hatred to Judas. The difficulties disappear if

the

reading proposed above is accepted.

According to Mt. 26

Mk.

after the

anointing in Bethany ‘ o n e of the twelve called Judas

Iscariot’ (Mt.

nearly

so

Mk.) went to the

chief priests and offered to betray Jesus to

them.

On receiving their promise of

‘money’

Mk.)

or

‘thirty pieces of silver

[shekels]’

Mt.

Judas sought for.

a n opportunity to betray him.

Lk.

altogether

disconnects the transactjon from the scene of the

anointing.

After noticing that every night Jesus camped

on the Mount of Olives

which

prepares the way for the notable statement in

mentions that the

was drawing near, and

that the chief priests and scribes were seeking for

a way

t o effect the destruction of Jesus.

Then Satan entered

into Judas, called Iscariot, of the number of the twelve’

t h e rest of the notice agrees with that of Mt. and Mk.

Evidently the assumption that Satan had entered into

Judas is

a humane one : treason against the Holy

One was too

a

crime for

a

disciple in his right

mind t o have committed.

I t should also be noticed

t h a t all the Synoptists (Mt.

Lk.

944)

mention that after Peter’s confession

of Jesus’

ship, Jesus spoke of his being ‘delivered

up

into the

hands of men.’ Mt. says that the disciples were ‘very

sorry’

Mk. and Lk. that they ‘understood not the

saying.’

never have guessed (nor did the

apostles guess) that one of them was capable of com-

mitting treason.

Quite

a different account

is

given in Jn.

Nothing is said of the visit

of

Judas to the chief priests

a n d

of

the promised payment of his

treason, nor of his deliberate search for

an opportunity t o betray Jesus.

I t was

a t the Last Supper that the hateful idea occurred t o

Judas, and it was inspired by the devil (13227). Jesus

openly declared

that one of his chosen

would ‘lift up his heel’ against him, to fulfil the old

scripture

(Ps.

Yet he gave one more special

proof of love to the traitor, and it was after this that

S a t a n took full possession of his captive.

Therefore

Jesus says t o him, That thou

do quickly’ ; Judas

went out, ‘ a n d it was night.‘ I t

is a modification of

the Synoptic tradition that we have here, though Lk.

h a s already suggested it by

reference to Satan.

I t

w a s not to any common temptation that

at last Judas

fell

he was taken by storm.

How, according

to

the original suggestion of treason (Jn. 1 3 was

made plausible, there

is

no direct evidence to show.

From

however, we infer that, according to

the evangelist, Judas was one of those who entertained

unspiritual views of Messiahship.

When the last hope

Both

and

are

upon a

and

have come out of

and

out of

was suggested

13

29.

Mt. assigns the niggardlyquestion ‘To what purpose etc.,

the disciples; Mk. to ‘some’ (of

Mt. is

right.

I n

no

mention is made of

a

murmuring

against the lavishness of the gift of love. Certainly it would

have spoiled

narrative

to have referred to this detail. Zahn

2517) thinks the view that there were

two

not

Impossible. It is at any rate more in accordance with our

experience

to

sup

that two divergent forms of the

same tradition were in

is one of

words.

2625

that Jesus would make himself king of Israel by force

had vanished, the evangelist possibly considered that

the love which Judas must formerly have had for Jesus

diminished, and that finally under Satanic influence it

turned into its opposite-hate. Godet regards the

nine picture

as

truly historical than that given by the

Synoptists, on the ground that in the former the relations

between Jesus and Judas ‘form an organic part of the

description of the repast, and are presented under the

form

of a series of historical shades and gradations.” A

very different view is taken by Keim, and

a

critical student

cannot fail to admit the force of Keim’s arguments.

What, then,

is the Synoptic description of the repast?

I t is the Paschal

that

and the Twelve

are eating.

Jesus has seen through

Judas before this solemn evening, but

has made no chancre in his

towards him.

Now, however, he announces the fact,

One of

you

will-betray me, even he that eats with me.’

I s it

I ?

asks each man sorrowfully.

It

is

one of the

twelve, he that dips with me in the dish

.

.

.

Good

were it for that man if he had not been born’ (Mk.

cp Mt.

T h e accounts

d o not entirely agree.

It is only Mt. who expressly

states that Judas the traitor also put the question, I s

it

I

?’-and the way in which the statement

is

introdnced

suggests that it is a n addition

to

the earlier story

(Mt. 2625).

as

we have seen, diverges most

widely from the simple form of the Synoptic narrative.

T h e account of the betrayal itself also is very variously

given.

All the Gospels agree that it was by an armed

band that Jesus was arrested, and that

Judas was its guide.

the scene of the

arrest, however, a n d the circumstances

are

different in the Synoptic Gospels a n d in Jn. respectively,

a n d it is for our present purpose especially noteworthy

that nothing is said in

Jn. of the kiss with which

according to the Synoptists Judas ventured t o greet

Jesus.

Mk. and Lk. give the simplest narrative

Mt.

(26

makes Jesus answer the traitor with

ad quod

(Vg.), a n untranslat-

able phrase, while Lk. gives, ‘Judas, betrayest thou

the

Son of Man with

a

kiss,’

what is prob-

ably the true reading in Mt.,

‘Thou feignest,’

a

part,’ ‘Thou art no friend of

T o Jn. the outward details of the act of Satanic

treachery

are

indifferent.

T h e end of the traitor

is

told in Mt.

27

3-10

18-20.

T h e discrepancies between the two accounts are remark-

*.

able, and the silence of Mk. and

Jn.

is also

noteworthy.

Mt. states that Judas,

on

finding that Jesus was condemned, was

struck with remorse, and brought back the thirty shekels

t o the chief priests, confessing that he had ‘betrayed

innocent blood.’ Then he hurled the ‘pieces of silver

into the sanctuary

and departed

to this

is added

a

further statement, complete in itself, ‘ a n d

he went away and hanged himself’

we are not

T h e chief priests, however, with

characteristic scrupulosity, would pot put the money

into the sacred treasury

but bought with it

the potter’s field to bury strangers in.

This field

on

(‘87)

3

criticism

that

form

of

the speech

of

Jesus is rhetorical does not go

to

the heart of the

matter.

The

form

he

but the idea

is

appropriate

t o

the

occasion.

Friend, (do) that for which thou

art

come,’

rendering of

is

most

unnatural

;

Judas

Lad

done his

work

the

of the

chief

had

to

do

the rest.

Yet

most

moderns

RV,

if

anything had preceded

which

made such

natural

Judas said,

“What shall I do?”’), it would be right to follow RV.

rendering, ‘Friend, wherefore art

come,’ is much

natural, but it is ungrammatical. There must be

an

error

the text.

(an unsuitable word, whether

we

render

‘Comrade’

or

‘Good Friend’) should come after

o

(so D a c

f

L c

i

It is

a

corruption of

a

dittographed

o

D

in

fact gives

EQ o

can

hardly have

come out of any other word than

2626

JUDAS

JUDAS

received the name, Field of blood,’ and

so

a prophecy

of Jeremiah

(or

rather Zechariah) was

Here

we have Iscariot represented a s a second Ahithophel,

who,

so

far a s intention went, betrayed David to his

enemy, and hanged himself

( 2

S.

23).

T h e account in Acts can be

advantage

to the sense, from the speech of Peter

in which it occurs,

and may perhaps be a later insertion.

It is, however, at

any rate of early date.

I t states that,

so

far from

restoring the money, Judas ‘acquired

a

field

see

F

IELD

,

9 ) with his unrighteous reward and falling

headlong (on the field) he burst asunder in the midst,

and all his bowels gushed out.’ Hence that field was

called Akeldama,

or

‘ T h e field of blood’ (see

A

CELDAMA

).

So,

it

is

added, the prophecies in Ps.

6925

and

1 0 9 8

were fulfilled.

Clearly here is a mere

popular explanation of ‘Akeldama,’ and not less

evidently here is the expression of the popular sense

of

justice a s regards the end of

traitor.

A

more elaborate and tasteless story is given by

(Fragm.

it seems to he an independent version of the

popular legend reminding

us

partly of Acts

1

18,

partly of the

legend of the edd of Antiochus Epiphanes in

9

Returning to the two biblical accounts, we note that

De Quincey

( Works,

6

21-25)

endeavours to remove the

discrepancies,

by purely arbitrary means.

This

is

quite needless.

Both the modes of death assigned t o

Judas were conventionally assigned to traitors and

enemies

of

God, and more especially that given in Acts

t o which there is a striking parallel in the story of the

death of the traitor Nadan-in the tale. of Ahikar.

Mr.

Harris

that

in Acts

may have been, not

but

‘having swollen out

the existing reading he accounts

for by a tradition which identified Judas with a poisonous

serpent, and he illustrates by upon thy belly shalt thou

go in Gen.

3

14.

See Did Judas commit suicide

July

rgoo.

T h e psychological attempts to explain the character

of

Judas

so

a s to comprehend the crime ascribed t o him

are numerous.

His despair has been

regarded a s a proof of original nobility

of character (Hase)

he has even been regarded a s

having sought‘the attainment

of

a

good

by evil

means

Neander too was touched by

the

same

anxiety for the misguided apostle.

‘If Jesus is the Messiah

so

he considers Judas to have

reasoned, ‘it will not