In-game advertising

How ‘Company X’ can adopt an effective in-game

advertising strategy for their ‘product Y’ based on

consumers’ goals

Management summary

‘Company X’, subsidiary of Unilever and producer of s, is looking for new channels to

advertise their ‘product Y’. We were asked to conduct research on this new channel and

investigate the advertising opportunities of the channel to attract new customers for

‘Company X’. Further, ‘Company X’ would like to know what advertising strategy best

suites their brand.

Both the number of gamers and the spending on in-game advertising are growing. Early

adopters already had their first acquaintance with in-game advertising. Due to new

technologies dynamic in-game ads pose a new opportunity for advertisers to pay for ads

within the game, over a period of time, which can coincide with their actual real-life

campaigns. Measurement services that track gameplay and in-game advertising to give

an analysis of videogame consumption, have already been developed.

Video games are quickly becoming the most effective medium for reaching consumers

via product integration; it may generate the best consumer recall, awareness and calls to

action, such as purchasing or recommending the product. Results also showed that

players do not mind in-game product placements.

The central research question is: How can ‘Company X’ adopt an effective in-game

advertising strategy for their ‘product Y’ based on consumers’ goals? A first specific

objective is to gain insight in the consumers’ goals when consuming ‘product Y’. Second,

the aim is to search for the underlying values that drive this consumption of ‘Z’ through

means-end chain theory. Third, the objective is to present recommendations for the

marketing communication through the application of the MECCAS model.

Given the research objective, a qualitative or exploratory research is conducted. The

methodology relies on the means-end chain approach with data being collected through

laddering interviews. Based on the analysis of the strongest means-end chains and the

list of consumers’ statements related to attributes, consequences and values, a

MECCAS representation for ‘product Y’ will be elaborated.

Introduction

‘Company X’, subsidiary of Unilever and producer of s, is looking for new channels to

advertise their ‘product Y’. There is a special interest in games, mainly to get in direct

contact with young consumers (15-30 years). This target group is seen by ‘Company X’

as the most promising audience for future sales. The purpose is to increase the sales of

‘product Y’ through in-game advertising.

We were asked to conduct research on this new channel and investigate the advertising

opportunities of the channel to attract new customers for ‘Company X’. Further,

‘Company X’ would like to know what advertising strategy best suites their brand.

First, this study gives an overview of the game industry, in-game advertising and their

recent developments and trends. Second, a model for consumer choice behaviour is

presented. Finally, an advertising strategy model based on consumer behaviour is used

to present recommendations for the ‘product Y’ branded marketing communication

activities.

Based on the research, ‘Company X’ should gain more insight to the opportunities of in-

game advertising based on consumer choice behaviour when buying ‘product Y’. The

research should help ‘Company X’ to decide whether in-game advertising can be part of

the advertising strategy for ‘product Y’.

1. In-game advertising

There are at least 112 million gamers 13 years and older in the United States alone,

says a Yankee Group report, and the number will grow to 148 million by the end of 2008

(Shields, 2005). Video games have a track record of delivering significant audience,

which includes some of advertising's most coveted consumers - men aged 18 to 34.

According to ratings giant Nielsen, young men play an average of 12.5 hours of

videogames each week (Ramirez, 2006). However gamers are a far more diverse lot

than that oft-cited stereotype with women coming on strong, accounting for 25 percent of

console participation in the U.S. The female representation is even greater in some

international markets. In China the gainer gender breakdown is about 50-50 among

teens and young adults (Goldrich, 2006). Gamers can be thought leaders when it comes

to technology and new trends. And they have money to spend (Murphy, 2006).

Types of in-game advertising

Essentially there are three types of ads that run in games. The first, most basic

execution, is ambient advertising. It consists mainly of hoardings, billboards and

traditional signage placed throughout a game - for example, on the sides of buildings in

a motorsport game. Another format taking hold is advergaming, in which agencies or

game developers create short, simple games that revolve around the brand, and create

an 'entertaining' environment for the consumer. But the third, most interesting format, is

dynamic advertising. Associated with games that have online network connectivity,

brands can pay for ads within the game, over a period of time, which can coincide with

their actual real-life campaigns (Murphy, 2006).

Early adopters of in-game advertising

Growing number of companies are putting their product placements in video games

(Bannan, 2002). Companies like Coca-Cola, Paramount and DaimlerChrysler advertise

in the videogame Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory where the secret agents encounter Sprite

machines, film promotions and billboards with Jeep trucks (Shields, 2005; Ramirez,

2006). DreamWorks plans to employ in-game advertising to promote its coming

animated film, ‘Flushed Away’ (O’Malley, 2006). And T-Mobile UK even committed a six-

figure budget to an in-game ad campaign (New Media Age, 2006).

In-game advertising spending

Spending on in-game advertising and product placement amounted to $56 million last

year. Thanks to new ad-serving technology, next-generation gaming consoles and new

metrics to measure both, spending will reach $730 million by 2010, according to

research firm Yankee Group (O’Malley, 2006; Ramirez, 2006). One reason for the

projected jump in spending: new tools that could make advertisements in games more

effective by tailoring them to players' ages or locations, or even the time of day that a

game is played (Hershman, 2005).

New technologies

In-game ads have been around for nearly 20 years, but two problems kept the market

from growing very large. Before 2005, ads were "static," meaning they were built into the

code when the game left the factory and couldn't be changed or updated. Game makers

were missing out on at least 50 percent of ad dollars that came from time-sensitive

promotions for products like new movie releases. The second problem was metrics. How

would advertisers know if a gamer ever proceeded to level 10 and actually saw the ad

they had paid for? (Ramirez, 2006).

Both problems are now being solved. Next-generation consoles like the Xbox 360 and

the PS3 are built from the ground up for broadband support, making dynamic ads just as

viable as they already were on Net-connected PCs (Ramirez, 2006). Massive, an

advertising agency specialized in in-game advertising, has developed software for

serving dynamic ads (Adformatie, 2006). The consoles’ internet link lets Massive's

software modify ads as players progress through game (Richtel, 2005).

Nielsen announced a new videogame-measurement service that will track gameplay and

in-game advertising to give an analysis of videogame consumption (Ramirez, 2006).

This new all-electronic ratings service, Nielsen GamePlay Metrics, will establish new

metrics for the buying and selling of advertising in video games (Gaudiosi, 2006).

DoubleFusion takes the technology even further, presenting advertisements as video,

audio, and 3-dimensional objects woven seamlessly into games' virtual worlds. A player

driving around a racetrack might pass a billboard advertising Tom Cruise's latest movie,

hear Metallica's new single, or get extra points for driving over a Pirelli tire (Hershman,

2005).

Gaming and consumer behaviour

Nielsen Entertainment reports that video games are quickly becoming the most effective

medium for reaching consumers via product integration. The study found that product

integration in video games may generate the best consumer recall, awareness and calls

to action, such as purchasing or recommending the product (McClellan, 2005). Results

also showed that players do not mind in-game product placements (Hein, 2005). They

are choosing to play these games, so its imperative the advertising does not detract from

this experience (Murphy, 2006).

According to its supporters, game advertising can provide hours of interaction between

the brand and the consumer. Advertisers can use this medium to drive 10 or 15 minute

experiences. For example, imagine a game where you can order a pizza in-game, and it

arrives at your door 20 minutes later (Murphy, 2006).

2. Conceptual framework

To investigate the opportunities for ‘Company X’ to add ‘product Y’ advertisements in

games, we first have to know what the underlying mechanism of consumer choice

behaviour is. Consumers pursue certain goals when they are consuming ‘product Y’ s.

These goals are investigated through means-end chain theory. Finally, the MECCAS

model (‘Means-ends Conceptualization of the Components of Advertising Strategy’) is

used for advertising message development.

Means-end chains as goal hierarchies

Goals are pleasant consequences (end states or otherwise) to be desired or unpleasant

consequences to be avoided (Winell, 1987). Goals are organized in hierarchies to

facilitate their accomplishment (Gutman, 1997). Lower-level goals (subgoals) are

subordinate to higher-level goals (Bandura, 1988; Beach, 1990) and serve as means to

achieve higher-level goals (Bettman, 1979; Newell and Simon, 1972). This means that

satisfying lower-level goals helps in achieving higher-level goals. Higher-level goals

represent the deep layer of consumer motivation (Pieters, Baumgartner and Allen, 1995;

Reynolds and Gutman, 1988). Goals are the essential regulators of consumer choice

behaviour and influence both the direction of and the intensity of behaviour (Carver and

Scheier, 1981).

Thus, goals provide the primary motivating and directing factor for consumer behaviour.

Consumer choice can be regarded as a person’s movement through a goal hierarchy

(Bettman, 1979). The elements in a means-end chain – attributes, consequences and

values – can be considered to be elements in a goal hierarchy. The goal hierarchy final

goal can be at the personal values level. When the final goal is at this values level,

relevant attributes and desired consequences are the goal hierarchy’s subgoals. Thus, a

means-end chain can be conceptualized as a goal hierarchy with product goals at lower

levels linked to important goals at higher levels (Gutman, 1997).

This conceptualization of consumer goal hierarchies bears close resemblance to the

notion of means-end chain structures of consumers’ product knowledge (Gutman, 1982;

Olson and Reynolds, 1983). The objective of means-end theory is to understand what

makes products personally relevant to consumers by modeling the perceived

relationships between a product (defined as a collection of attributes) and a consumer

(regarded as a holder of values) (Pieters, Baumgartner and Allen, 1995). It proposes that

consumer product knowledge is hierarchically organized, spanning different levels of

abstraction (Howard, 1977; Gutman, 1982).

Means-end theory treats attributes, consequences and values as basic content of

consumer product knowledge stored in memory. Attributes are features or aspects of the

product or brand. The personal consequences associated with an attribute provide the

personal meaning of that attribute to the consumer. Consequences represent the

reasons why an attribute is important to someone and why it is positively or negatively

valenced (Reynolds, Gengler and Howard, 1995). Consequences acquire meaning

because they are seen as instrumental in achieving values central to the self. In this

sense, product attributes are the “means” by which a consumer is able to achieve the

desired “end” state of existence associated with value satisfaction. Values are assumed

to provide the motivation for choosing a product with certain attributes, and the aim is to

relate product attributes to the self via consequences of product use (Walker and Olson,

1991). Self-relevant and desirable product meanings are presumed to be the basis for

consumer preferences and choice (Gutman, 1982; Claeys, Swinnen and Van den

Abeele 1995).

MECCAS advertising model

Building on the means-end chain theory, Reynolds and Gutman (1984) have proposed

the “means-end conceptualization of the components of advertising strategy” or

MECCAS model. This model offers a framework to integrate the consumers’ perceptual

orientation (including the personal motivations embedded in the means-end chains) with

the current strategic positioning of a product (Vanoppen, Verbeke and Van

Huylenbroeck, 2002). The MECCAS model comprises elements of the advertising

strategy corresponding with each level of the means-end chain. In order to be effective,

the ad’s content elements should link message elements (describing product attributes)

to consumer benefits and the more abstract consequences. The ad’s content that

evokes these psychological consequences is crucial in activating the consumers’

motivational network, hence the term ‘leverage point’. If it works, the audience is brought

to ‘closure’ and eventually to the decision to buy (Vanoppen, Verbeke and Van

Huylenbroeck, 2002).

The MECCAS model recommends that an advertising message must (Bech-Larsen,

2001): a) be based on the message-relevant knowledge (cognitive structure) of the

recipients, b) create or enforce a full means-end chain in the minds of the recipients, ie.

a cognitive chain that contains product attributes and consequences as well as personal

values, and c) anchor this means-end chain to the object (ie. product, brand) of the

message by exercising creative talent in the design of the linkage strategy and the

executional framework.

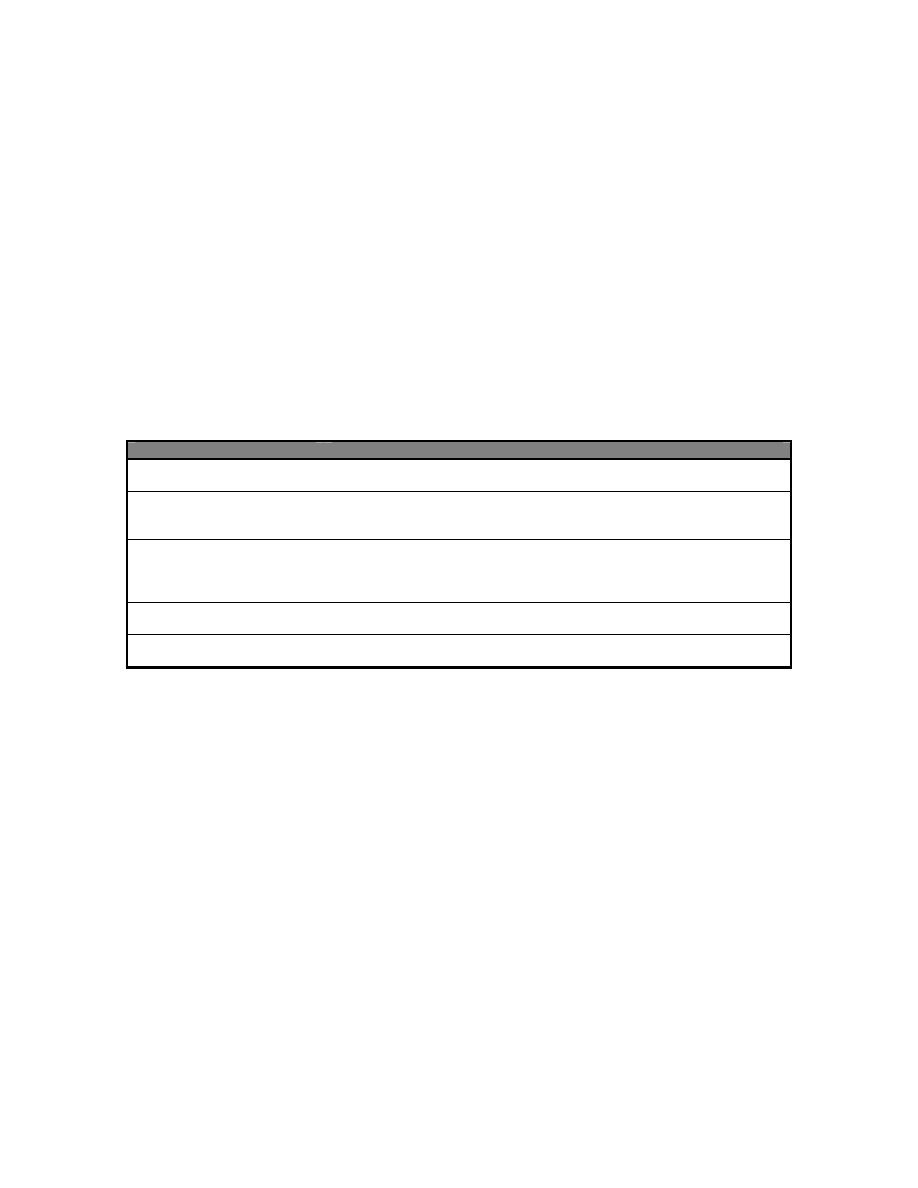

The following table presents and defines the various levels of the MECCAS model. The

driving force is the consumer value or end-level that the advertising strategy focuses on.

Every other level is geared toward achieving the end-level (Shimp, 1993).

Level

Definition

Driving force

The value orientation of the strategy; the end-level to be focused on in the

advertising

Leverage point

The manner by which the advertising will “tap into”, reach, or activate the

value or end-level of focus; the specific key way in which the value is linked

to the specific features in the advertising

Executional framework

The overall scenario or action plot, plus the details of the advertising

execution. The executional framework provides the “vehicle” by which the

value orientation is to be communicated; especially the Gestalt of the

advertisement; the overall tone and style

Consumer benefit

The major positive consequences for the consumer that are to be explicitly

communicated, verbally or visually, in the advertising

Message elements

The specific attributes or features about the product that are communicated

verbally or visually

Table 1: Percy and Woodside (1983) in Shimp (1993)

In conclusion, the important point to remember about the MECCAS approach is that it

provides a systematic procedure for linking the advertiser’s perspective (the possession

of brand attributes and consequences) with the consumer’s perspective (the pursuit of

products to achieve desired end states, or values). Effective advertising does not focus

on product attributes/consequences per se; rather, it is directed at showing how the

advertised brand will benefit the consumer and enable him of her to achieve what he or

she most desires in life (Shimp, 1993).

3. Research objectives

The overall objective of this case study is to conduct research on the opportunities for

‘Company X’ for placing ‘product Y’ advertisements in games based on the goals

consumers pursue. The central research question is:

How can ‘Company X’ adopt an effective in-game advertising strategy for their ‘product

Y’ based on consumers’ goals?

A first specific objective is to gain insight in the consumers’ goals when consuming

‘product Y’ s. Second, the aim is to search for the underlying values that drive this

consumption of s through means-end chain theory. Third, the objective is to present

recommendations for the marketing communication through the application of the

MECCAS model.

4. Research methodology

The case at hand includes the assessment of features in combination with specific

product attributes as antecedents to consequences and values that consumers strive for.

Given the research objective, a qualitative or exploratory research is conducted. The

methodology relies on the means-end chain approach with data being collected through

laddering interviews. Laddering refers to an in-depth, one-on-one interviewing technique

used to develop an understanding of how consumers translate the attributes of products

into meaningful associations with respect to self, following Means-End Theory (Reynolds

and Gutman, 1988). Laddering is a frequently used approach for eliciting means-end

chains and is used to derive aggregate value chains - i.e., prototypical sequences of

attributes, consequences, and values for a sample of consumers (Pieters, Baumgartner

and Allen,1995). In a laddering interview, subjects are first asked to identify salient

attributes that distinguish choice alternatives in a product class. Next, they are prompted

to verbalize sequences of attributes, consequences and values, creating a chain of

elements with each element being directly linked to the element adjacent to it (Gutman,

1997).

The laddering interviews will be conducted one-on-one in an in-depth format, gathering

information through 40 personal laddering interviews. All respondents should be

experienced gamers. Attention will be paid to obtaining a sample with a wide diversity of

socio-demographic characteristics.

Using the Laddermap software (Gengler, 1997; Reynolds, Gengler and Howard, 1995),

each ladder recorded during the interviews will be encoded, whereby each statement will

be labeled as attribute, consequence or value. The software counts the number of links

between the encoded concepts and visualizes them in an implication matrix (showing

how frequently each concept implies another one). This implication matrix forms the

basis for drawing hierarchical value maps (Reynolds and Gutman, 1988; Vanoppen,

Verbeke and Van Huylenbroeck, 2002). Hierarchical value maps or consumer decision

maps (Reynolds, Westberg and Olson 1994) show the salient linkages between

attributes, consequences and values. The map indicates which values make products

personally relevant, and this information is useful in developing advertising strategies

(Reynolds and Craddock, 1988; Reynolds and Gutman, 1984; Reynolds, Westberg and

Olson 1994).

Based on the analysis of the strongest means-end chains and the list of consumers’

statements related to attributes, consequences and Values, a MECCAS representation

for ‘product Y’ s will be elaborated.

5. Planning and budget

We are able to conduct this research in a period of 13 days. The specific planning will be

preparation (3 days), interviews (2 days), analysis (5 days) and conclusions /

recommendations (3 days).

The budget for the study will be: 13 days * 8 hrs. * € 100,- = € 10400,-

6. Conclusion

This preliminary study shows that there still is a lot of research to be done on effective

advertising in games. We are convinced that the results of the proposed research will be

able to give ‘Company X’ more insight to the opportunities of in-game advertising based

on consumers’ goals and corresponding values. The research will help ‘Company X’ to

decide whether to adopt games as a new channel for advertising. Therefore,

recommendations on how to create an effective advertising message, given the

technological possibilities at present, are made to support marketing communications.

We would like to thank you for the opportunity to write this research proposal. We look

forward to continue the cooperation with ‘Company X’.

References

Adformatie (2006), “In-game reclame wordt interactief en meetbaar”, Adformatie 30/31,

27 July 2006, pp. 14

Bandura, A. (1988), “Self-regulation of motivation and action through goal systems, In:

V. Hamilton, G.H. Bower and N.H. Frijda (eds.), Cognitive perspectives on emotion and

motivation, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic

Bannan, K.J. (2002), “Companies try a new approach and a smaller screen for product

placements: video games”, New York Times, 5 March 2002

Bech-Larsen, T. (2001), “Model-based development and testing of advertising

messages: A comparative study of two campaign proposals based on the MECCAS

model and a conventional approach”, International Journal of Advertising 20, pp. 499-

519

Beach, L.R. (1990), “Image theory: Decision making in personal and organizational

contexts”, Chichester: Wiley

Bettman, J.R. (1979), “An information processing theory of consumer choice”, Reading:

MA: Addison-Wesley

Carver, C.S. and M.F. Scheier (1981), “Attention and self-regulation: A control, theory

approach to human behaviour”, New York: Springer Verlag

Claeys, C., A. Swinnen and P. Van den Abeele (1995), “Consumers’ means-end chain

for ‘think’ and ‘feel’ products”, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Special

Issue: Means-end Chains, Jerry Olson (guest editor), pp. 193-208

Gaudiosi, J. (2006), “Nielsen on In-Game Ads”, Next Generation, 17 October 2006

[http://www.next-gen.biz/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=4028&Itemid=36]

Gengler, C. (1997), Laddermap Means-End Software

Goldrich, R. (2006), “Epstein's Got Game For Ad Biz”, SHOOT; 10/6/2006, Vol. 47 Issue

17, pp. 1-11

Gutman, J. (1982), “A means-end chain model based on consumer categorization

processes”, Journal of Marketing 46, pp. 60-72

Gutman, J. (1997), “Means-end chains as goals hierarchies”, Psychology and Marketing,

6, pp. 545-560

Hein, K. (2005), “Gaming Product Placement Gets Good Scores in Study”, Brandweek,

vol. 46, no. 44 (05 12), pp. 16

Hershman, T. (2005), “Game On”, Technology Review, vol. 108, no. 5 (01 05), pp. 25

Howard, J.A. (1977), “Consumer behaviour: Application and theory”, New York:

McGraw-Hill

McClellan, S. (2005), “In-Game Integration Reaps Consumer Recall”, MediaWeek, vol.

15, no. 44 (05 12), pp. 4

Murphy, J. (2006), “Gaming's advertising appeal”, Media Asia; 9/8/2006, pp.13

Newell, A. and H. Simon (1972), “Human problem solving”, Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall

New Media Age (2006), “T-Mobile to push Mates Rates tariff through first in-game ads”,

New Media Age, 16 February 2006, pp. 5

O'Malley, G. (2006), “In-game hits next level with 'Flushed' “, Advertising Age; 9/25/2006,

Vol. 77 Issue 39, pp. 8

Perry, L. and A.G. Woodside (eds.) (1983), “Advertising and consumer psychology”,

Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books, D.C. Heath and Company

Pieters, R., H. Baumgartner and D. Allen (1995), “A means-end chain approach to

consumer goal structures”, International Journal of Research in Marketing, 12, pp. 227-

244

Olson, J.C. and T.J. Reynolds (1983), “Understanding consumers’ cognitive structures:

Implications for marketing strategy”, In: L. Percy and A.G. Woodside (eds.), Advertising

and consumer psychology, Lexington, MA: Lexington Books

Ramirez, J. (2006), “The New Ad Game”, Newsweek; 7/31/2006, Vol. 148 Issue 5, pp.

42-43

Reynolds, T.C. and A.B. Craddock (1988), “The application of the MECCAS model to the

development and assessment of advertising strategy”, Journal of Advertising Research

28 (2), pp. 43-54

Reynolds, T.C., C.E. Gengler and D.J. Howard (1995), “A means-end analysis of brand

persuasion through advertising”, International Journal of Research in Marketing 12, pp.

257-266

Reynolds, T.C. and J. Gutman (1984), “Advertising is image management”, Journal of

Advertising Research 24, no. 1, pp. 27-37

Reynolds, T.J. and J. Gutman (1988), “Laddering theory, method, analysis, and

interpretation”, Journal of Advertising Research, 28, pp.11-34

Reynolds, T.J., S. Westberg and J.C. Olson (1994), “A strategic framework for

developing and assessing political, social issue and corporate image advertising”, In:

Kahle (ed.), Advertising and consumer psychology, Lexington, MA: Lexington Books

Richtel, M. (2005), “A New Reality In Video Games: Advertisements”, New York Times,

April 11 2005

Shields, M. (2005), “A new dynamic”, Brandweek, 16 May 2006, Vol. 46, Issue 20, pp.

SR30

Shimp, T.A. (1993), “Promotion Management and Marketing Communications”, third

edition, Orlando, FL: The Dryden Press

Vanoppen, J., W. Verbeke and G. Van Huylenbroeck (2002), “Consumer value

structures towards supermarket versus farm shop purchase of apples from integrated

production in Belgium”, British Food Journal, 10, pp. 828-844

Walker, B.A. and J.C. Olson (1991), “Means-end chains: Connecting products with self”,

Journal of Business Research 22, pp. 111-118

Winell, M. (1987), “Personal goals: The key to self-direction in adulthood”, In: M.E. Ford

and D.H. Fort (eds.), Humans as self-constructing living systems: Putting the framework

to work, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Rubenstein A Course in Game Theory SOLUTIONS

Stinchcombe M B , Notes for a Course in Game Theory

Osborne M J , A Course in Game Theory Solution Manual

Balliser Information and beliefs in game theory

Using the In Game Menus

5th Lecture How To Advertise In A Poker Game

Prywes Mathematics Of Magic A Study In Probability, Statistics, Strategy And Game Theory Fixed

Egelhoff Tom C How To Market, Advertise, And Promote Your Business Or Service In Your Own Backyard

Elkies Combinatorial game Theory in Chess Endgames (1996) [sharethefiles com]

55 Defending In The Modern Game Progression 1 – 1v1 Stop

Game of Thrones The Sword in the Darkness poradnik do gry

56 Defending In The Modern Game Progression 2 Pressure

S Belavenets Basic principles of game are in middlegame (RUS, 1963) w doc(1)

59 Defending In The Modern Game Progression 5 3v3 Pres

Play Action 1 Skin in the Game Jackie Barbosa

How to Debate Leftists and Win In Their Own Game Travis L Hughes

All in a day vocabulary and grammar game

Chapter 3 Tactical play in all stages of the game

więcej podobnych podstron