EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS

RESEARCH SERIES NO.25

How employers manage

absence

STEPHEN BEVAN, SALLY DENCH,

HEATHER HARPER AND SUE

HAYDAY

Published in March 2004 by the Department of Trade and Industry.

URN 04/553

ISBN

0 85605 418 6

© Crown Copyright 2004

This and other DTI publications can be ordered at: www.dti.gov.uk/publications

Click the ‘Browse’ button, then select ‘Employment Relations Research Series’.

Alternatively call the DTI Publications Orderline on 0870 1502 500 (+44 870 1502

500) and provide the URN, or email them at: publications@dti.gsi.gov.uk

This document can be accessed online at: www.dti.gov.uk/er/emar

Postal enquiries should be addressed to:

Employment Market Analysis and Research

Department of Trade and Industry

1 Victoria Street

London SW1H 0ET

United Kingdom

Email enquiries should be addressed to: emar@dti.gov.uk

The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those

of the Department of Trade and Industry or the Government.

Foreword

The Department of Trade and Industry's aim is to realise prosperity for all. We

want a dynamic labour market that provides full employment, flexibility and

choice. We want to create workplaces of high productivity and skill, where

people can flourish and maintain a healthy work-life balance.

The Department has an ongoing research programme on employment relations

and labour market issues, managed by the Employment Market Analysis and

Research branch (EMAR). Details of our research programme appear regularly in

the ONS journal Labour Market Trends, and can also be found on our website:

http:/www.dti.gov.uk/er/emar

DTI social researchers, economists, statisticians and policy advisors devise

research projects to be conducted in-house or on our behalf by external

researchers, chosen through competitive tender. Projects typically look at

individual and collective employment rights, identify good practice, evaluate the

impact of particular policies or regulations, or examine labour market trends and

issues. We also regularly conduct large-scale UK social surveys, such as the

Workplace Employment Relations Survey (WERS).

We publicly disseminate results of this research through the DTI Employment

Relations Research series and Occasional Paper series. All reports are available

to download at

http:/www.dti.gov.uk/er/inform.htm

Anyone interested in receiving regular email updates on EMAR’s research

programme, new publications and forthcoming seminars should send their

details to us at:

emar@dti.gov.uk

The views expressed in these publications do not necessarily reflect those of the

Department or the Government. We publish them as a contribution towards

open debate about how best we can achieve our objectives.

Grant Fitzner

Director, Employment Market Analysis and Research

iii

The Institute for

Employment Studies

The Institute for Employment Studies is an independent, apolitical, international centre

of research and consultancy in human resource issues. It works closely with employers

in the manufacturing, service and public sectors, government departments, agencies,

professional and employee bodies, and foundations. For over 30 years the Institute has

been a focus of knowledge and practical experience in employment and training policy,

the operation of labour markets and human resource planning and development. IES is

a not-for-profit organisation which has a multidisciplinary staff of over 50. IES expertise

is available to all organisations through research, consultancy, publications and the

Internet.

IES aims to help bring about sustainable improvements in employment policy and

human resource management. IES achieves this by increasing the understanding and

improving the practice of key decision makers in policy bodies and employing

organisations.

iv

Contents

Executive Summary

vi

Introduction

1

Managing absence: the context

1

Managing absence: the policy context

1

Aims of the study

3

Absence management: literature review

3

Methods

8

Business and employment context

13

Business strategy: markets and competitors

13

Links to human resource (HR) strategy

14

Vulnerability to absence

14

The nature and extent of absence

17

Introduction

17

Types of absence

18

Policies

20

Extent of and trends in absence

26

Measurement and monitoring

29

Key points

30

Managing absence

31

Introduction

31

Unplanned absence

31

Planned absence

35

The cumulative impact

37

Line managers

38

Key points

39

Costs and benefits

41

Introduction

41

The costs of absence

41

The benefits of absence

49

Key points

51

Conclusions

53

How worried are employers about absence?

53

Which kinds of absence cause most problems?

53

How effectively do employers manage absence?

54

What differentiates those who cope well from those who do not?

54

How would they cope if there was a high take-up of the new leave entitlements? 55

Appendix A: Case studies

56

v

Financial Services case study

56

Food Retailer case study

69

Law Firm case study

78

Manufacturing Company case study

86

Merchant Bank case study

90

NHS Trust case study

99

School case study

107

Small Business case study

114

Small Engineering Company case study

119

IT Technology R&D case study

125

Telecomms Company cse study

132

Appendix B: Bibliography

139

Appendix C: Data Tools

143

HR Managers Topic Guide

144

Managers Topic Guide

156

Employees Topic Guide

167

Different types of absence

174

‘Map’ of topics for exploration with HR Managers

176

Appendix D: Absence Costing Tools

178

vi

Executive summary

In the main managing absences was not a major issue of concern for employers.

Indeed, in response to recruitment difficulties there were instances of

organisations introducing initiatives aimed at employees to improve their work-

life balance. Though management do not systemically collect information to

monitor absence, sickness absence was seen to be on the decline, while non-

sickness absence was on the increase (though from a low base). Generally,

unplanned absences caused more problems than planned absences.

Introduction

Background

Employee absence from work has received greater attention in recent years. This is

due in part to increased emphasis on employers’ ‘duty of care’ towards their

employees, concerns to maximise labour utilisation in competitive marketplaces and the

minimisation of the costs and disruption caused by absence from work.

In the UK there are several sources of data on absence. The Labour Force Survey (LFS)

publishes data on the percentage of employees absent from work due to illness or

injury on at least one day in a reference week. Data from the winter 2000/2001 LFS

show this rate to be 3.8 per cent of working days lost. Other data are derived from

surveys of employers. For example, the CBI conducts an annual survey of sickness

absence patterns. Its 2001 survey shows that an average of 7.8 days (3.4 per cent)

were lost per employee in 2000 (a similar figure to 1999). The 1998 Workplace

Employee Relations Survey (WERS98) collected data from establishments which

suggest that average daily absence rates for those with more than 25 employees stood

at 4.1 per cent.

Of course employee illness or injury are not the only causes of absence. Employees in

the UK now have a variety of statutory rights to time off work. More recently acquired

rights reflect both a shift in emphasis in EU and UK policy and a changing pattern of

demand from employees themselves, and have been introduced to facilitate employees

balance the demands of their work and their domestic responsibilities better. Employees

can now legitimately be absent from work for a wide range of reasons, including:

annual leave, maternity leave and ante-natal care, adoption leave, domestic

emergencies, paternity leave, parental leave, career breaks, civic responsibilities and

religious holidays. Policy makers are concerned to ensure that these provisions do not

place unnecessary or disproportionate burdens on employers.

vii

Aims of the study

The main aims of the study were:

l

To investigate how employers manage and cope with the consequences of different

types of absence

l

To provide real life examples of how employers manage absence

l

To investigate the costs and benefits, including any administrative burden

associated with implementing the legislation. To establish the context in which

employers provide for the recording, monitoring and developing of active absence

management practices.

Research approach

A case study approach was adopted. Since employers’ approaches to managing

absence might be expected to vary according to their labour use requirements case

studies were selected to provide examples where managing absence might be expected

to be an issue. Therefore, the sample of organisations included the following features:

l

A high proportion of female employees

l

Low skill substitution owing to size

l

Low skill substitution owing to skill specialisation

l

Low skill substitution due to high dependence on client relationships.

Interviews were conducted with human resource (HR) managers, line managers and, in

some cases, employees. In addition, examples of written policies were collected and

examined to provide a basis for documentary analysis.

Business and employment context

The fieldwork was conducted during 2001/2, a period of economic growth, low

unemployment, widely reported skill shortages and general labour market buoyancy.

Public sector organisations had clear goals relating to the delivery of public services

that are set against a range of externally determined standards and benchmarks.

Customer demand for these services was increasing faster than the resources available

to deliver them. In our two public sector organisations, adequate staffing levels were

critical to their ability to deliver the quality of service expected.

The nine private sector organisations had adopted business strategies compatible with

the markets within which they were operating. These were varied and related to price

competitiveness, fast turnaround and delivery times, the quality of the service offered,

specialist expertise and knowledge, ‘value for money’ and cost reduction. In many

smaller organisations there was no formalised HR strategy or infrastructure. However,

their approach to employees was usually well articulated and understood. Organisations

were seeking to fit their staffing needs to their business priorities, eg by adopting

flexible working practices to fit with customer demands.

In the main, managing absence was not a major issue of concern. Other labour related

issues were creating significantly greater pressures. The main concern was recruitment

and retention, particularly the ability to attract suitably skilled employees at a time of

viii

buoyant labour market conditions which, in a number of instances, led to initiatives

aimed at helping employees achieve an easier work-life balance.

The nature and extent of absence

Absence can be categorised in a number of ways. For the purposes of this study the

key distinctions were between planned and unplanned and long- and short-term

absence.

Unplanned absence included that attributed to the onset of illness (whether genuine or

not), and time off to deal with family and domestic emergencies, an ill dependent,

bereavement and urgent medical appointments. Most unplanned absence was short-

term. Planned absence included annual leave, maternity, paternity and parental leave,

religious holidays, career breaks, sabbaticals, time off for training and study, trade

union duties, time off for civic duties and for involvement in various voluntary and

community activities. Long-term sick leave and flexible working patterns (such as part-

time working or job-sharing) can also be regarded as planned absence. Planned absence

can be short- or long-term in nature.

Trends in absence within organisations were difficult to explore accurately, as very

little information was systematically collected and recorded. Sick and maternity leave

were usually recorded for pay reasons and to ensure compliance with statutory

obligations. However, these data were rarely being used to actively measure and

monitor absence. Nonetheless employers reported that sickness absence had generally

declined, that employees in less rewarding jobs were more likely to have higher levels

of unplanned sick leave and that sick leave was higher amongst young men (who were

seen to have more negative attitudes to work). More generally, employers reported that

there was a slight upward trend in the amount of non-sickness absence though overall

levels of take-up were relatively low. The take-up of parental leave was very limited

and this was attributed to it being unpaid and relatively little known. Provision above

the statutory minimum leave entitlements was generally restricted to select groups of

employees, depending on such factors as grade and/or role, line manager’s discretion

and their value to the organisation.

Managing absence

Policies relating to absence addressed two main issues:

l

Parameter setting for line managers and employees through defining what was

allowable and under what conditions

l

The management of absence, in particular monitoring and minimising sick leave.

Employers in this study consistently reported that unplanned short-term sick leave

was the most problematic to cope with on a day-to-day basis.

As a rule, the existence of formal policies to manage absence was a function of the

size of the organisation. Informality of practice was found in all of the case studies, but

the larger organisations also had policy documents to guide and regulate practice.

In smaller firms, practices to govern access to time off and to manage the

consequences of absence had built up informally over time, often relying on the

discretion of the owner or director. In practice, this meant that eligibility to time off for

domestic reasons, for example, may not be consistent or transparent. In addition,

ix

practices adopted to cover absence tended to be more ad hoc than in larger

organisations. There were a number of reasons for the use of formal policies to manage

absence:

l

Of creating an environment of trust and reciprocity within an organisation

l

Compliance with legislation and to ensure that employees were aware of their basic

rights

l

To inform managers and employees what was acceptable and what was not

l

Practices could become more formalised and controllable

l

As part of promoting better work-life balance for employees

l

To aid recruitment and retention.

Line and project managers played a major role and had great autonomy in deciding

whether and how to provide cover. As a result of this, it is difficult to discern clear

patterns in the type of leave allowed because there is considerable variation amongst

line managers in what they will allow, and among individual employees in what they

feel able to ask for, especially where policies are not very specific. The confidence,

attitudes and background of individual managers played a role. In organisations, where

HR played a supportive role and flexibility is accepted, managers seem much better

able to cope with absence. The overall culture of an organisation was very important in

managers’ abilities to cope with absences.

The decision making process in covering short-term and long-term unplanned and

planned absences was similar, and most organisations adopted more than one

arrangement to cover absence. The first general approach was to look internally, and

only if there was no internal capacity, would people from outside be brought in. In

deciding how to cover a particular absence, duration of the absence tended to be the

most influential factor.

Unplanned absence

A number of contextual factors were identified as influencing decisions on whether

cover was needed and the type of cover. These included:

l

The immediacy of the work to be covered and the nature of client relationships

l

How busy the team/department with the absence is at that particular time

l

How busy other teams/departments are

l

The overall level of absence

l

The degree to which there is skill flexibility between roles/jobs to be covered, or

specialist skills are required.

A decision is taken as to whether cover is needed. If it is, it is always the preferred

option to cover within a team or department. This may include asking colleagues to

take on extra (unpaid) work on a temporary basis, paying overtime, or using internal

‘pools’ or ‘banks’ of staff. Some larger employers deliberately employed extra

permanent staff to provide cover in business-critical areas. Once options to cover

internally had been explored and exhausted, external cover was brought in.

x

Planned absence

Short-term planned absence was covered in similar ways to unplanned absence.

Longer-term planned absence might be covered (usually in the following order) by:

l

Some reallocation of work within a team or department

l

Moving someone else within the company, perhaps as a development opportunity.

These may be temporary promotions or secondments

l

A temp

l

Employing a replacement on a fixed-term contract.

Bringing in cover from outside was usually confined to support, rather than operational

or strategic roles. The specialist skills and knowledge needed in the latter positions are

rarely readily available, although external consultants were sometimes used.

The cumulative impact of absence

It was very difficult to identify a point at which the level of absence becomes a

particular problem for employers. There were a range of intervening factors, for

example, the immediacy of the work, relationships with clients and customers, how

busy a department or company is, the attitudes of managers, and the overall culture of

the organisation. Some senior managers expressed concerns about potential increases

in the take-up of planned leave and options to work flexibly. They anticipated there

being a critical mass of employees who are not available during normal working hours.

However, there was no evidence that this had yet occurred. Indeed, the dominant

picture was one where employers found planned absence considerably more

manageable.

Costs and benefits

The costs of absence

Only two organisations were able to attribute any kind of financial cost to absence or

provide the data needed to calculate the cost. In neither case were these data

comprehensive. There were a number of reasons for this, including:

l

Availability of data

data on the amount of absence is often not collated centrally

or, for certain types of absence is not collected at all. Furthermore, the information

needed to calculate costs is often held by different parts of an organisation and is

difficult to co-ordinate.

l

Willingness to provide data

several employers were unwilling to provide cost data

due to the amount of time and effort required, the sensitive nature of these data,

the need to make assumptions and estimates, and there being insufficient benefit in

making the effort (there are other more urgent priorities).

The following costs arising from employee absence were identified:

l

Direct financial costs, for example, the salary and other benefits paid to an

employee who is absent, overtime payments, the costs of hiring temporary cover.

l

Indirect costs, for example, the time taken for a replacement to learn the new role

and become productive; diminished services and product quality; loss of business

xi

and reputation arising from absence. Although, when the need arose, managers

were seen to put significant effort into ensuring that these costs were only incurred

as a last resort.

l

Indirect cost on management time; including monitoring, consulting HR and

occupational health specialists, dealing with the individual involved, developing

strategies, arranging for cover, training and providing support to staff providing

cover. Overall, it was unplanned leave and some types of long-term sick leave that

had the greatest impact.

l

Indirect cost on HR time. HR managers generally saw managing absence and

enabling employees to work productively, flexibility and healthily as an integral part

of their role. The most costly type of absence in terms of HR time was sick leave;

and, all the organisations were proactively managing sick leave, in particular aiming

to minimise the amount taken.

l

The negative impact of absence on employee motivation, especially if it is not

properly managed, for example, where insufficient cover is provided or some

employees are seen to be abusing the system.

The benefits of absence

Employers generally found it difficult to identify benefits of absence. Nevertheless a

number of positive aspects emerged:

l

Providing opportunities for planned absence sends positive messages to employees

since they feel valued and prepared to reciprocate in terms of loyalty and putting in

extra effort when needed. Allowing employees time off to deal with emergencies

was said to improve productivity since employees spent less time at work worrying

about problems and trying to sort things out.

l

Providing development opportunities for other employees allowing them to show

their abilities in more senior positions. This was particularly associated with

providing cover for long-term, often planned, absence.

l

Requiring employers’ managers to rethink their labour resourcing requirements and

the organisation and allocation of work. Where this happened, it often led to wider,

sometimes unanticipated benefits to the business.

Conclusions

This study draws the following conclusions:

l

Employers were generally unconcerned about most types of absence. They had

other more pressing human resource priorities. Most effort was put into managing

and minimising the amount of absence due to illness, or absence attributed to this.

l

It is the unpredictability of some absence which caused the greatest problem.

l

The ease and effectiveness with which absence was managed varied between

employers. Some had ad hoc and somewhat reactive approaches, others had well-

established practices which allowed them to respond to most incidences of

absence.

l

Those who managed absence well were also more likely to have a climate of trust

and mutuality, a positive outlook amongst line managers and high levels of internal

skill substitution.

xii

l

Higher take-up of the new leave entitlements is an unlikely prospect for a number of

employers. Where take-up does increase, it seems likely that absence which is

planned and predictable will be the least problematic to manage.

About this project

The research was carried out as part of the Department of Trade and Industry’s

employment relations research programme. It was undertaken by Stephen Bevan, Sally

Dench, Heather Harper and Sue Hayday of the Institute of Employment Studies,

Brighton (www.employment-studies.co.uk).

1

1.

Introduction

Managing absence: the context

Employee absence from work has received greater attention in recent years. In part this

has been due to increased emphasis on employers’ ‘duty of care’ towards their

employees, a concern to maximise labour utilisation in competitive marketplaces and a

concern to minimise the costs and disruption caused by excessive absence from work.

In aggregate, there are several sources of data about absence in the UK. The Labour

Force Survey (LFS) publishes data on the percentage of employees absent from work

due to illness or injury on at least one day in a reference week. Data from the winter

2000/2001 LFS show this rate to be 3.8 per cent

1

of working days lost. Other data are

derived from surveys of employers. For example, the Confederation of British Industry

(CBI) conducts an annual survey of sickness absence patterns. Its 2001 survey

2

shows

that an average of 7.8 days (3.4 per cent) were lost per employee in 2000 (a similar

figure to 1999). The 1998 Workplace Employee Relations Survey

3

collected data from

establishments which suggest that average daily absence rates for those with more

than 25 employees stood at 4.1 per cent. While there are other employer surveys of

absence (conducted, for example, by the Industrial Society and by the Chartered

Institute of Personnel and Development), none are able to provide a definitive picture.

One of the reasons for this is that a core assumption of many of the surveys is that

employee illness or injury is the primary causes of absence. Yet in recent years it has

become clear that employees can be absent from work for a wider range of reasons. A

recent DTI survey

4

shows that fewer employers record data on absence for reasons

other than illness or injury, particularly paternity leave. This situation has been

influenced, in part, by a changing policy context.

Managing absence: the policy context

Employees in the UK now have improved statutory rights to time off work. These

developments reflect both a shift in emphasis in EU and UK policy, and a changing

pattern of demand from employees themselves. Many of these rights have been

introduced to allow employees opportunities to balance the demands of their work and

their domestic responsibilities. For many years UK employees have had statutory rights

to maternity leave and time off for trade union duties. The Employment Relations Act

(ERA) 1999 introduced further entitlements for:

1

Labour Market Trends, May 2001, p. 237

2

CBI, ‘2001 Absence and Labour Turnover Survey’, May 2001

3

Cully M. et al. (1999), Britain at Work: As depicted by the 1998 Workplace Employee

Relations Survey, London: Routledge

4

DTI Employers survey on Support for Working Parents, 2000

2

l

Thirteen weeks unpaid parental leave within the first five years of the child’s life

l

Unpaid leave to deal with an emergency involving a dependant

l

Improved and additional rights to maternity leave.

In addition, the Working Time Regulations (WTR) 1998 gave all employees a right to

four weeks paid leave from 1999; while in the course of this study the government

announced that it

1

would also provide employees with paid paternity and adoption

leave (due in April 2003) and extended maternity rights (including increased maternity

pay from April 2002, an increase in the period over which statutory maternity pay is

paid from April 2003 and an increase in relief for small employers for maternity pay

from April 2002).

In sum, there has been an extension to the range of current provisions under which a

proportion of the workforce might legitimately be absent from work. Some of these

absences can be anticipated and planned for, including:

l

Annual leave

l

Maternity leave

l

Time off for ante-natal care

l

Adoption leave

l

Career breaks

l

Absence for civic responsibilities

l

Religious holidays

l

Paternity leave

l

Parental leave.

Others may be unplanned, including:

l

Time off for domestic emergencies

l

Lateness

l

Short-term sickness absence.

While the intention of policy in this area is to improve provision for employees with no

previous rights to annual leave and for those with domestic caring responsibilities,

policy-makers are also concerned to ensure that such provisions do not place

unnecessary burdens upon employers. It might be argued, for example, that new rights

to time off work (including those recently proposed) could represent an additional

burden on employers, if they result in a significant increase in both the direct and

indirect costs associated with the need to manage the consequences of either planned

or unplanned absence from work.

1

Work and Parents: Competitiveness and Choice

Green Paper, (DTI, 2000) announcements

made in Budget 2001 and subsequent announcements.

3

It was a concern to assess the ways that employers manage a range of absence which

prompted the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) to commission the Institute for

Employment Studies (IES) to conduct a research study into current employer practice.

Aims of the study

The primary aims of the study were:

1. To investigate how employers manage and cope with the consequences,

organisational and administrative, of planned and unplanned absence of different

duration, and to identify the range and estimate the costs associated with coping

with different types of absence.

2. To provide a range of examples of how employers deal with different types of

absence and their consequences (eg arranges cover, hires temporary staff, re-

allocates workload etc.). This will focus on assessing both the direct and indirect

costs and benefits to the firm of the employers’ decision to manage absence.

3. To investigate whether the recent legislation will result in new administrative

burdens or other costs, and whether these are expected to be offset by a reduction

in reported sickness absence.

4. To gather other, contextual, information about employers’ approaches to measuring,

monitoring and managing absence, investigate the level and process of decision

making, and to broader work-life issues.

5. To compile a research report which details the key findings from the study in a

manner which allows policy makers to understand employer behaviour in the light of

new leave arrangements introduced under recent legislation.

Absence management: literature review

All of the mainstream literature in this area deals with the control of absence or the

management of attendance. Thus, its focus is the absentee worker rather than the

direct workplace consequences of absence and its management. Some passing

references are made in some work on the need for co-workers to cover absence, but

these are used as reasons for controlling absence rather than as a substantive issue for

study.

We have so far found no work which examines the strategies adopted by employers to

manage and cover planned or unplanned absence of the kind under scrutiny by the

current study.

It is interesting to note, however, that the tenor of the literature on absence has

changed over the last decade. It has done so in the following ways:

1. Reduced emphasis on control: much of the early literature has concentrated on

absence being a facet of employee behaviour which needs to be controlled and

minimised (Scott and Markham, 1982; Erwin and Iverson 1994). This has been an

approach perpetuated by the personnel profession and by the language used in this

field. As Bevan and Heron (1999) point out:

‘The persistent use of the term absenteeism, for example, reinforces a view

held by many line managers that individuals have a psychological disposition

towards absence or, put another way, indifference towards attendance.’ P.4

4

A key characteristic of the literature in this area is the implicit notion that non-

attendance per se, is always negative and that maximising attendance is a key

responsibility of the employer for reasons both of control and of operational

effectiveness.

2. Increased emphasis on line manager roles: in a development which mirrors greater

delegation of people management in many organisations, there has also been an

increased emphasis on the role played in managing absence by line managers

(Reynolds, 1990; Cole and Kleiner, 1992). This is, in part a tacit recognition of the

fact that local management is more likely to be able to identify and influence some

of the causes of absence and, indeed, to manage the consequences.

3. Greater recognition of non-medical absence: outside of the field of organisational

behaviour, the dominance of literature focusing on the medical causes of absence

has contributed to ‘sickness absence’ being seen as the most important cause of

non-attendance (Jenkins, 1985; Leigh, 1986). In the last decade, however, major

reviews of the literature (Johns, 1997; Harrison and Martocchio, 1998) have sought

to ensure that non-medical causes of absence (such as morale, organisational

climate, domestic caring responsibilities etc.) have been properly seen in context.

4. Growing recognition of the use of ‘sickness absence’ as generic term for wider

absence: some literature has begun to examine the extent to which employees are

absent for reasons other than sickness. Haccoun and Desgent (1993) found that

female employees were more likely to report that they were absent owing to the

illness of a child. Similarly, Nicholson and Payne (1987) found evidence that women

were more likely to be absent because of domestic problems. Haccoun and Dupont

(1987) conducted a study in a hospital which involved interviewing employees

returning from a period of either planned or unplanned absence. They found that 72

per cent admitted that they had not been ill. Among other activities (including

shopping) women reported that they had been tending to family matters. Men were

more likely to report ‘resting’. As this body of work grows, it becomes clearer that

researchers are accepting that employees are absent from work for a wider range of

reasons than illness. It is also clear, however, that illness is still frequently regarded

as only one of the ‘legitimate’ or valid reasons for absence from work

though this

view is slowly changing as the work-life debate gains greater prominence.

5. Interest in the consequences of absence: a narrow range of studies has looked at

the consequences of employee absence. Some have examined the impact on

individual performance (Bycio, 1992; Tharenou, 1993). These studies show that

supervisory performance ratings of employees with high absence tend to be lower,

as is attainment on accredited courses. Other work has examined wider

organisational impact. Moch and Fitzgibbons (1985) found that absence had a

negative impact on departmental production efficiency only when the absence was

unplanned. In a study of coal miners Goodman and Leyden (1991) found that

absence caused reduced workgroup familiarity which, in turn, led to reduced

productivity. In another related study of miners (Goodman and Garber, 1988),

unfamiliarity owing to absence was found to be related to an increase in accident

rates. Barber, Hayday and Bevan (1999) found that, in a retailing business, staff

absence was negatively correlated with customer satisfaction.

Overall, therefore, the literature illustrates the continuing dominance of absence related

to ill-health in the consciousness of both researchers and practitioners. However, there

5

are signs that the emphasis of absence management is moving away from control of

absence and towards the encouragement of attendance. In addition, there is a

recognition that absence can frequently be attributed to a growing range of factors

beyond ill-health.

Costing methodologies

Within this category, there are two groups of material providing practical examples of

costing methods that will be useful to the study.

Tools to cost absence

While these are very few and far between, we found one or two useful examples:

1. Checklist produced by Cascio (2000) to derive the hidden costs of ‘Absenteeism and

Sick Leave’. The checklist, which comprises 11 key steps, is illustrated with worked

examples from a hypothetical manufacturing company. The chapter in which this

checklist is described also contains guidance on the interpretation of absence costs

data and the management of absence.

2. A simpler checklist is reported by Seccombe and Buchan (1993) for use among

nursing staff in the NHS. It differentiates between direct and indirect costs,

identifies the approaches used to cover for absent employees and attempts to

quantify the impact of absence on both quality of patient care and on productivity.

Contains a worked example.

3. An approach to costing absence which is based on predicted behaviour is described

and tested in a study by Martocchio (1992). Using measured job attitudes, this work

predicts absence behaviour among employees and then seeks to ascribe a cost to

this absence. This is the least useful study as it implies that absence is dispositional.

It also fails to differentiate between direct and indirect costs.

4. A detailed checklist devised by Oxenburgh (1991) as part of a publication on health

and safety management. Using a worked example, it focuses on employment costs

and lost productivity. It also combines ‘top-down’ approaches with ‘bottom-up’

methods. It makes puzzling assumptions about the allocation of HR costs.

5. An unpublished study by Berkowitz (1995). This used a checklist approach to

calculate the ‘full costs’ of absence due to illness or injury. It appears to be

comprehensive work, though little technical detail of the approach is available. No

occupational differences are examined.

While this was a somewhat disappointing result, it was not unexpected. On a positive

note, the Cascio, Oxenburgh and Berkowitz work was quite comprehensive and was of

considerable benefit in designing an absence-costing tool.

Tools to cost other labour flows

This is a field where the review has unearthed rather more which will be of practical

benefit. The main area covered by this work is employee turnover, where more work on

costing has been conducted.

Much of this work is rooted in human resource accounting approaches which were

popular in the USA in the 1970s and 1980s. Thus, the work of Bassett (1972),

Flamholtz (1973), Jeswald (1974), Fitz-enz (1984); and Dawson (1988) were attempts

6

to devise robust approaches to the calculation of replacement costs. For the most part,

this work is comprehensive, but is likely to be too complex to be used by managers in

organisations. Other, more practical approaches (Cawsey and Wedley 1979; Hall 1981;

Cascio 1987; Bland-Jones 1990; and Fair 1992) are more useful as they were based

on data to which employers were likely to have access and were presented in a more

logical manner. A detailed checklist produced by Hall (1981) remains one of the most

comprehensive and practical tools available. Important features include its approach to

costing lost productivity among replacement staff, its use of weighted averages in the

firm-level aggregation of job-specific data, and its worked examples.

The various approaches to costing employee turnover in the literature lead us to the

view that the four main elements of cost that can be identified are:

l

Separation costs: costs relating to the termination of the contract of employment

(eg exit interviews, payroll administration)

l

Temporary replacement costs: costs generated by the provision of temporary or

supplementary cover as a direct consequence of an employee leaving

l

Recruitment and selection costs: those costs incurred in replacing the single,

notional leaver

l

Induction and training costs: those costs incurred, after appointment, in establishing

the new incumbent in his or her post, and developing their skills and expertise to

the point at which they cease to be a net cost to the employing organisation.

Based on these headings, IES (Buchan, Bevan and Atkinson, 1988) has developed its

own turnover costing checklist by asking 20 employers to complete the checklist for

three different jobs (clerical, professional and managerial). The piloting exercise judged

the checklist against four main criteria:

l

Incidence: the extent to which the defined cost was commonly or normally incurred

during turnover

l

Variability: the potential variance in the magnitude of the cost incurred

l

Maximum magnitude: the extent to which the cost heading was a major contributor

to the overall cost of turnover

l

Accuracy of measurement: the degree to which an accurate measurement of the

defined cost was feasible, given the existence (or otherwise) of relevant data.

It was found that certain posts, and the way that a vacancy was covered, attracted

higher temporary replacement costs. It was also found that employers needed to make

assumptions about the cost of management time (by the hour or the day), and about

the time it took for a new recruit to become a net contributor to the organisation (the

learning curve productivity costs).

In using the principles of the Hall checklist and the checklist devised by IES for the

purpose of costing absence, a number of points should be noted which might

reasonably be expected to increase the values derived by them:

1. The checklists rely predominantly on identifiable direct costs. They make no

allowance for other items of cost which might reasonably be attributable to turnover

or absence, including lost sales, lost customers, sales opportunities not taken,

7

inability to take on new (or fulfil existing) contracts. These ‘opportunity’ costs can

be attributed both to the leaver/absentee and to those covering the vacancy or

spending time filling the vacancy or organising cover.

2. The salary element of costs do not account for National Insurance contributions or

other employer ‘on-costs’ such as pensions.

3. No allowance is made for any performance differential between leavers and their

replacements.

4. No account is taken of the differences in costs between internal and external cover

for absence.

5. No explicit account is taken of the duration of the absence being covered and its

impact on costs.

6. No account is taken of lost productivity among co-workers of a leaver/absentee both

while the vacancy remains unfilled and during the induction and initial training of a

new or temporary postholder.

At the same time, in a number of other respects, an individual incidence of turnover or

absence may result in short-term financial benefits. These include the following:

1. The saving of the employment costs of the leaver/absentee while the post is vacant

2. The difference in salary between the leaver/absentee and the replacement (assuming

the replacement is being paid at a lower level).

Neither of these factors is taken into account in the costing approaches reviewed to

date. To this extent, replacement and productivity figures arrived at through the use of

such checklists cannot be said to be ‘net costs’.

Contribution of the current study

The current study has a distinctive focus in several respects:

l

It places an explicit emphasis on the organisational consequences of a wide range

of absence. Previous work has focused primarily only on sickness absence, with

little attention given to the consequences for the employer.

l

In doing so it differentiates between planned and unplanned absence, anticipating

that different forms of absence may be easier to manage than others.

l

It seeks to identify and quantify the costs and benefits associated with various

forms of absence.

l

In looking in detail at employer practices, the study is also firmly set within a policy

context where the take-up of a widening range of policies and practices which

allow employee to take time off work is likely to increase.

It was expected that the study would provide qualitative evidence of the management

strategies being adopted to manage absence, and that it would highlight areas for

future research as employer practices change.

8

Methods

Case study research design

A case study approach for this research was chosen for two main reasons. First, case

studies allow a detailed appreciation to be gained of the business context of each

participating organisation. This is essential if the business consequences and costs of

managing absence is to be understood. Second, case studies allow a more detailed

understanding to be gained of the factors underpinning managerial decision-making

(such as the competitive position of the organisation, its culture and its history).

It was also felt important that the research should gather:

1. Detailed narrative accounts of how absence was being managed on a day-to- day

basis

2. The views of senior managers, line managers and employees about managing the

consequences of absence

3. Organisation-level data on the patterns of absence being experienced, together with

any data on costs and/or benefits which were available.

It was felt that a case study design (rather than, for example, a survey design) was

best suited to addressing the project aims. A total of 11 case study organisations were

included.

Selection of case study organisations

It was felt likely that approaches to managing absence might vary by employer type. In

order to examine this, it was decided to select case studies according to a number of

criteria. These criteria reflect some prior expectations about where problems in

providing cover might occur. Each is described below.

l

High proportion of female employees: in these organisations it might be expected

that there would be a high take-up of leave arrangements which focus on domestic

care responsibilities (eg maternity leave, emergency leave, parental leave etc.). In

these organisations it might be more likely that the cumulative impact of a

significant number of absences would be experienced.

l

Low skill substitution owing to size: in these organisations it could be hypothesised

that some absence will be difficult to cover owing to the small number of

employees. In such circumstances, it might be that low staffing levels do not allow

scope for transferability or cover.

l

Low skill substitution owing to skill specialisation: here, the organisation may find

the management of absence difficult if employees have specialist skills which make

internal transferability or external temporary replacement of staff difficult.

l

Low skill substitution owing to high dependence on client relationships: in these

organisations, the nature of employee relationships with customers and clients is

such that absence among some staff groups are difficult or costly to cover because

of client-specific knowledge or a high dependence of clients on certain key

individuals.

9

Data collection tools

A number of tools for collecting data were designed for the study. These appear in

Appendix C. In summary, they are:

1. Human resources (HR) manager discussion guide: this was intended to collect

information about the organisation’s policies and practices in relation to absence,

how these policies were initiated, their focus and their impact.

2. Line manager discussion guide: this was particularly focused on identifying the

practical steps which line managers took to organise cover for absence and to

examine the practical consequences of absence within the organisation.

3. Employee discussion guide: this guide was intended to collect views from employees

about how their own absence was covered, the impact this had on them, their

colleagues and clients. It was also intended to be a way of collecting views from

those employees affected by the absence of colleagues.

These tools were developed in consultation with the DTI and amended after the early

case studies were started. In addition, case study organisations were asked to provide

supporting material (eg details of formal absence policies), where available.

Costing tool

One of the aims of the study was to explore the extent to which employers are able to

ascribe financial costs or benefits to absence. Using examples from the literature, IES

developed an absence costing spreadsheet (see Appendix D) which collected data on:

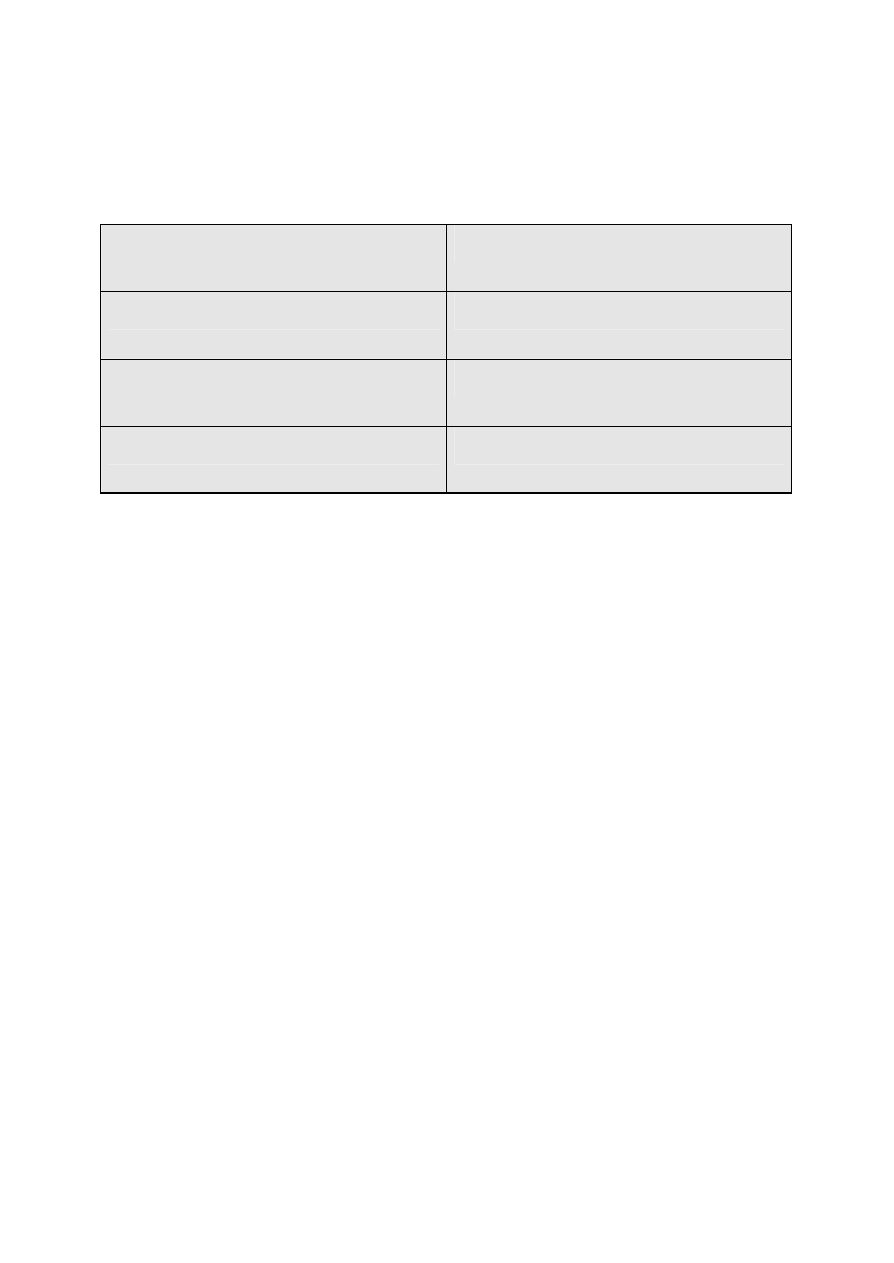

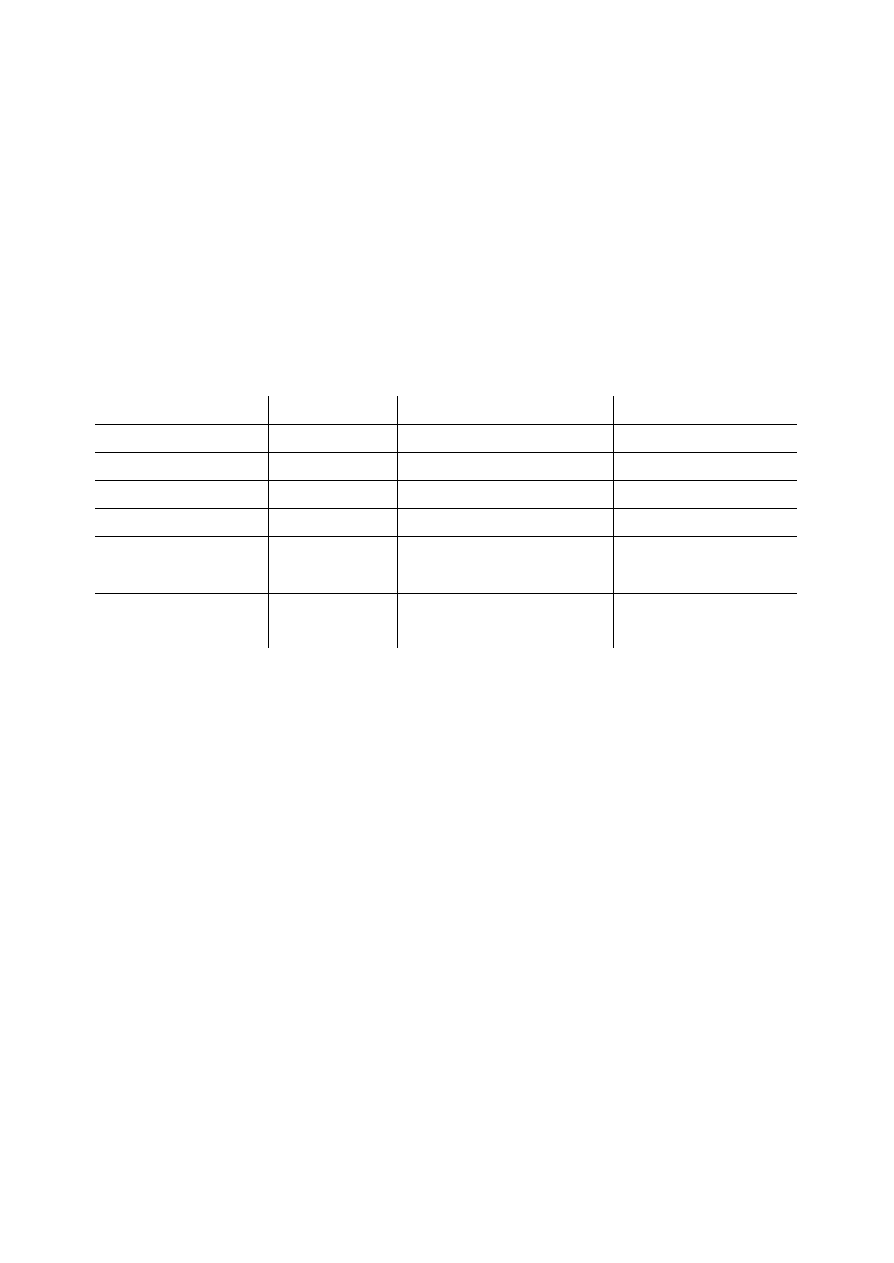

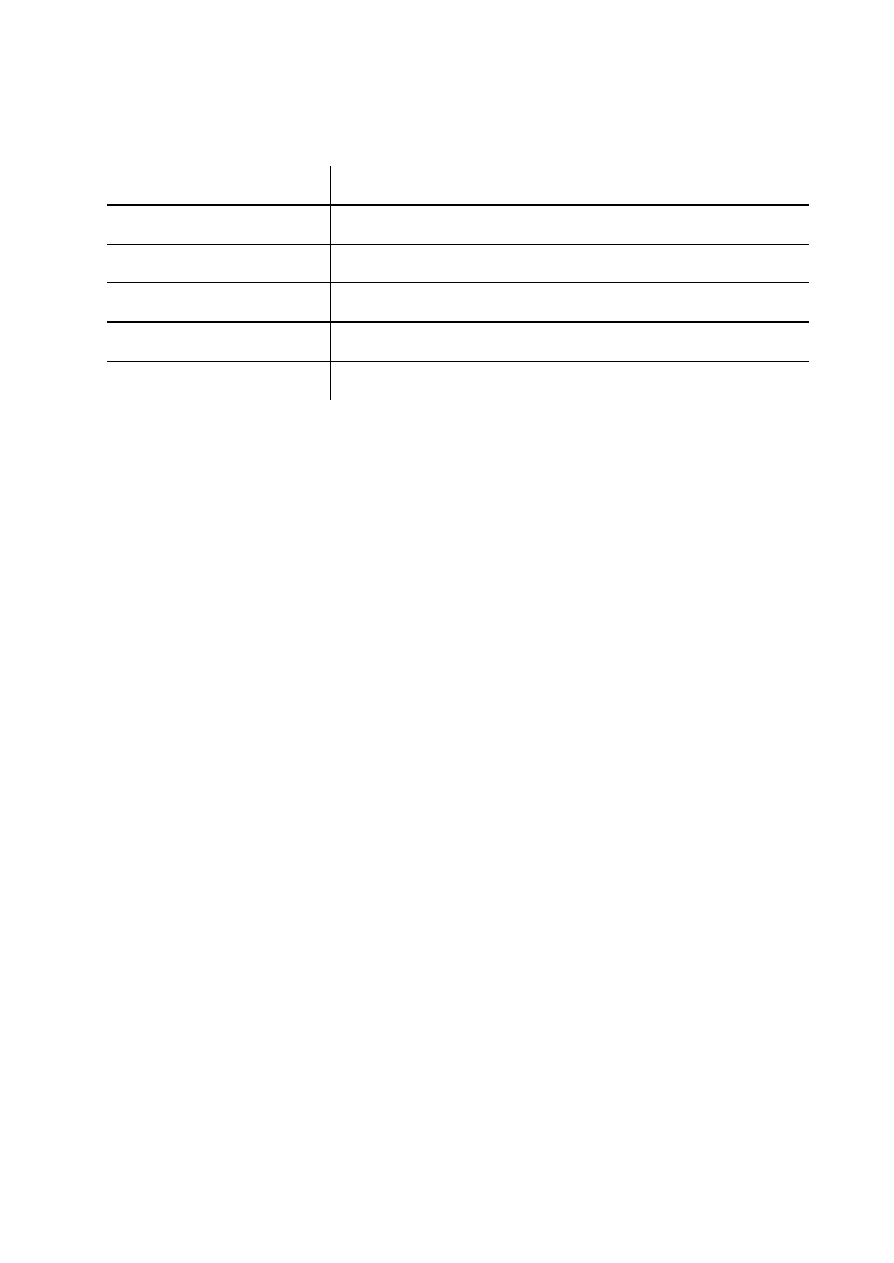

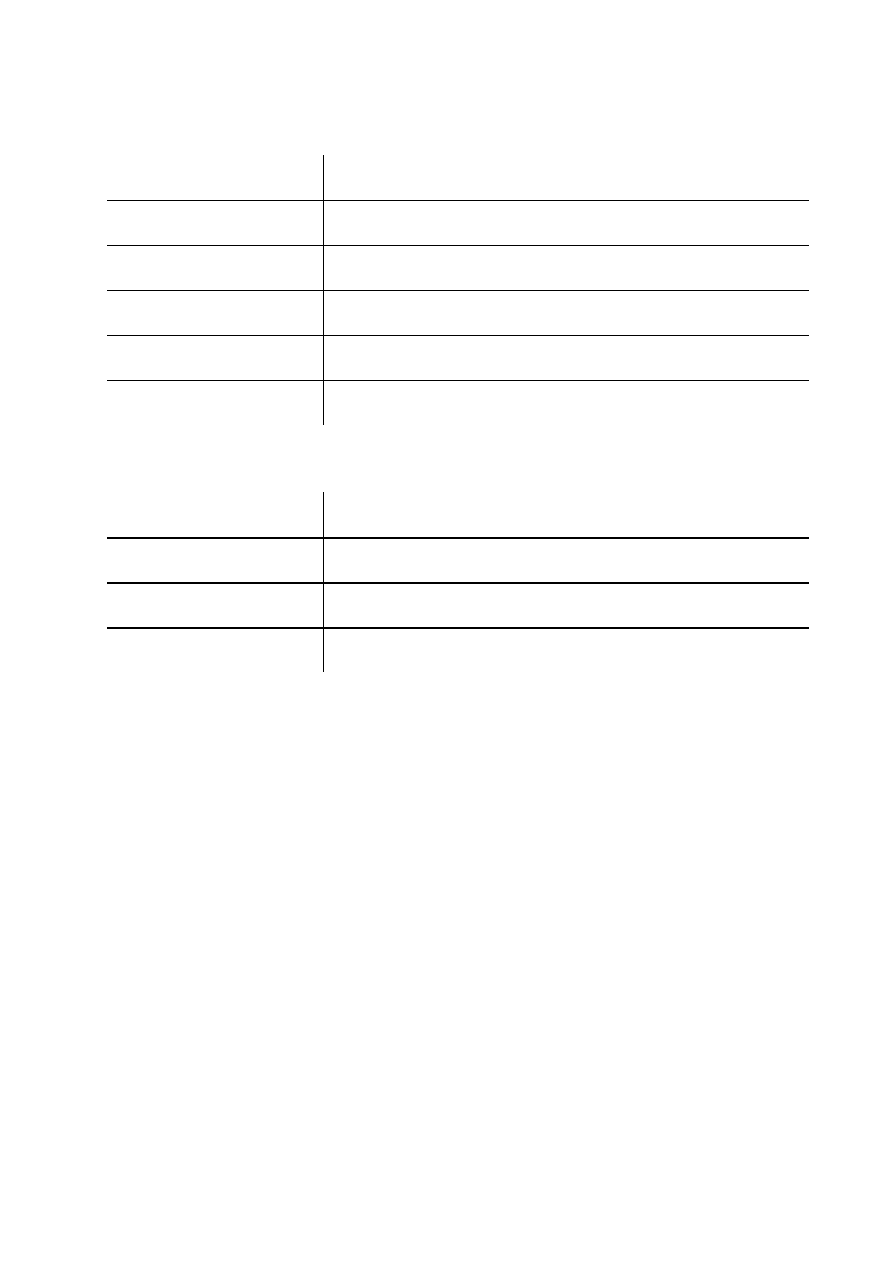

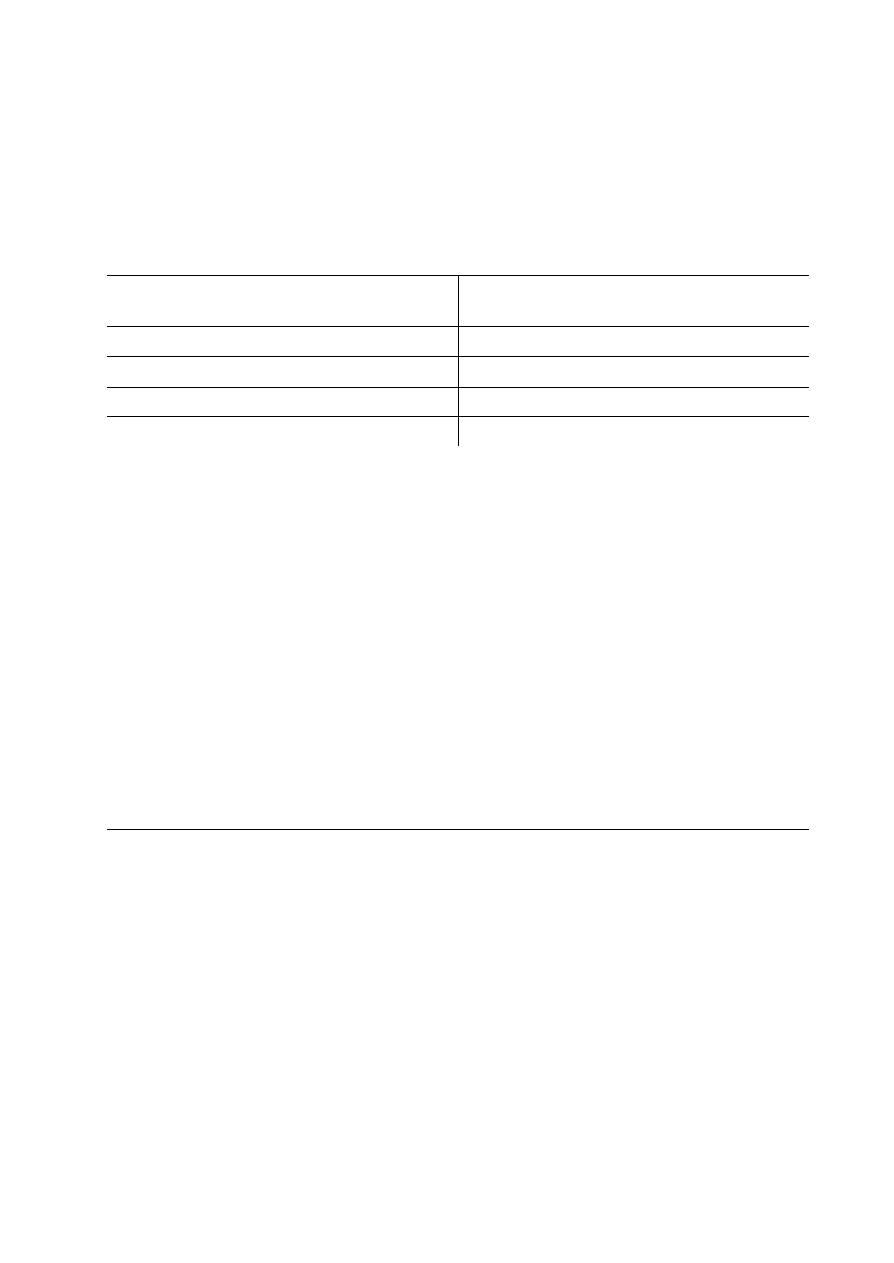

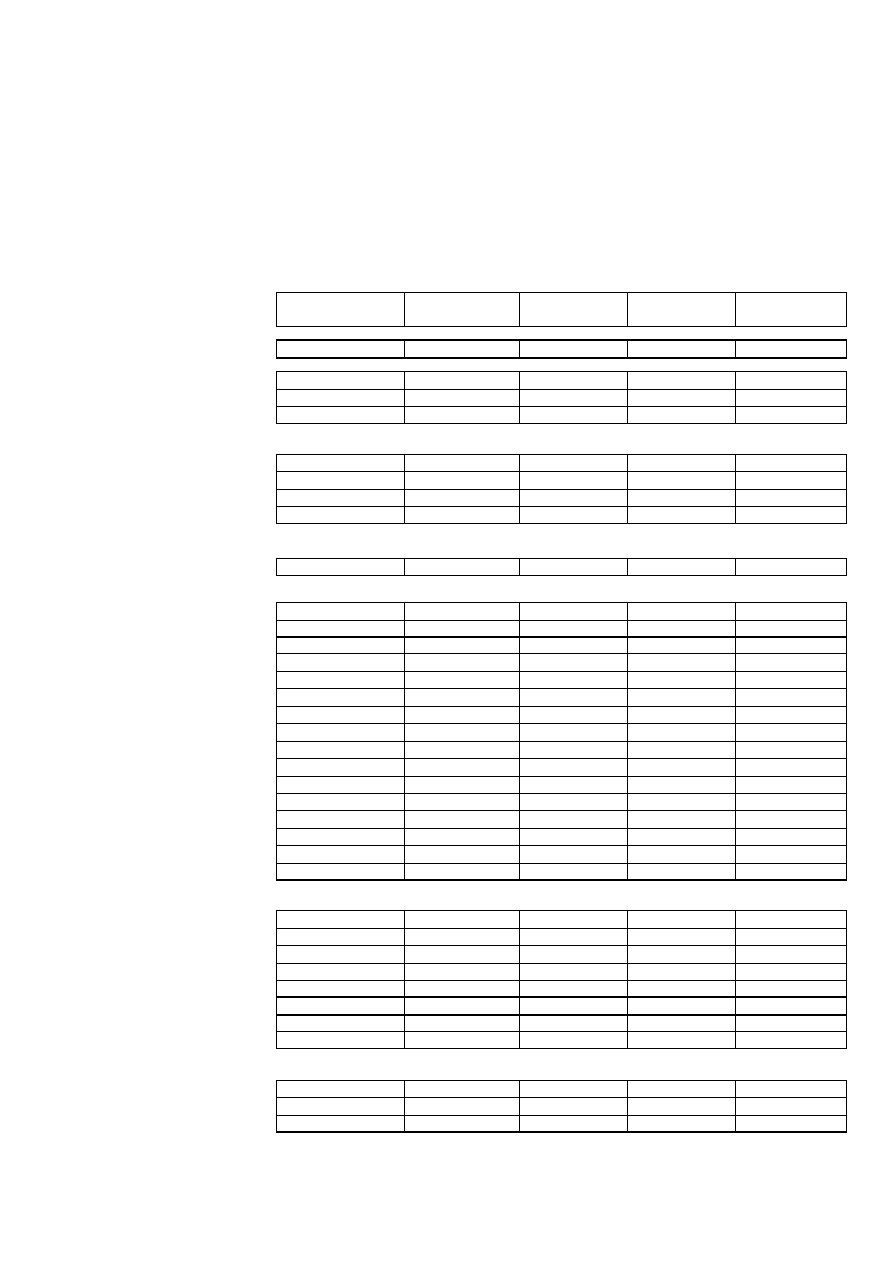

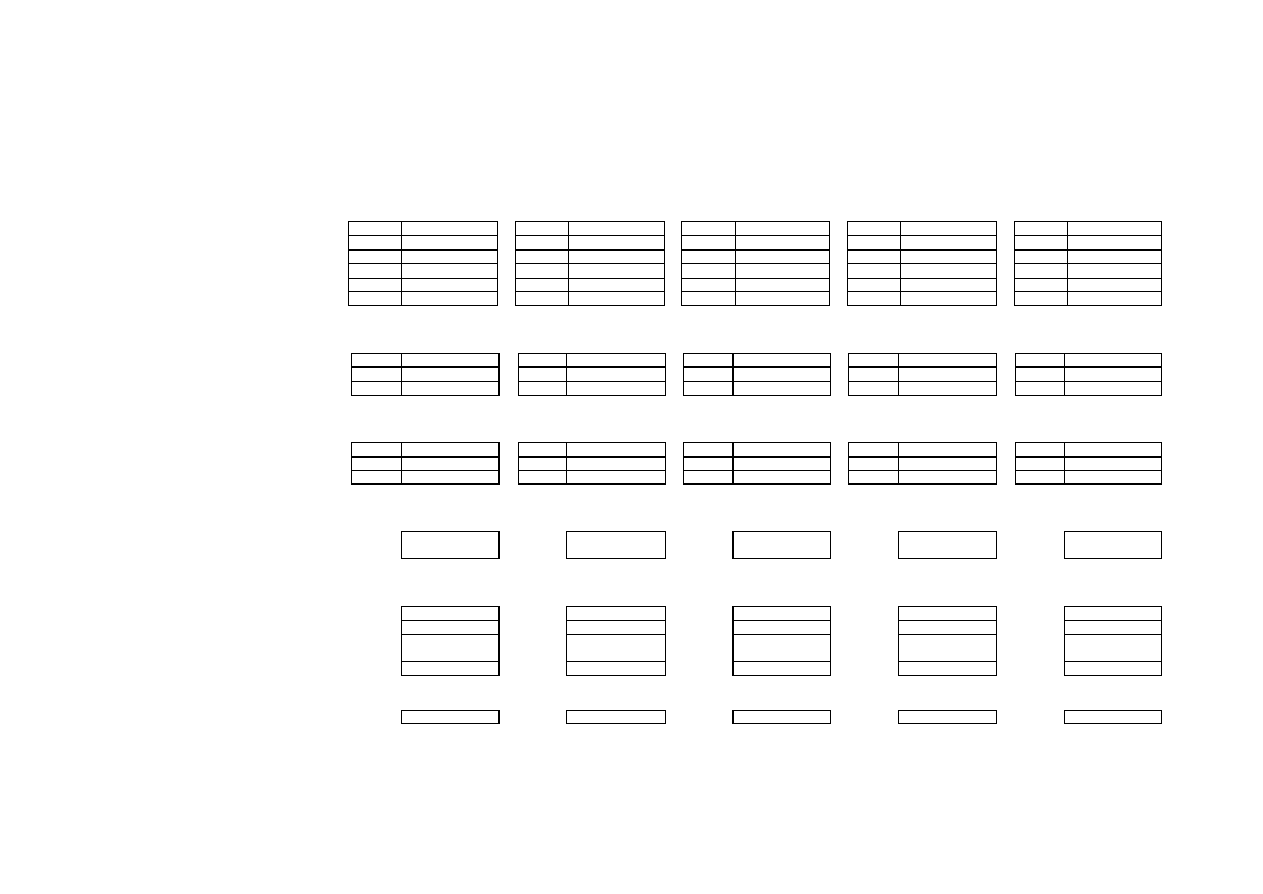

Table 1.1 Summary of case study organisations

Type of organisation

Number of

employees

Sample selection criteria

Small IT business

S

Low skill substitution

size

Small engineering company

S

Low skill substitution

size

School

M

Low skill substitution

skill specialisation

NHS trust

L

High proportion female employees

Food retailer

L

High proportion female employees

Law firm (secretarial function)

L

High proportion female employees

Financial services

back office

function

M

High proportion female employees

Financial services

call centre

L

Low skill substitution

client relationships

Financial services

complaints dept

S

Low skill substitution

client relationships

Telecomms R&D

L

Low skill substitution

skill specialisation

Merchant bank

L

Low skill substitution

client relationships

Manufacturing company

L

Traditional male manufacturing/low take-up

expected

Technical R&D

L

Low skill substitution

skill specialisation

S = small (less than 50 employees), M = medium (50 to 250 employees), L = large (over 250 employees)

10

1. Absence patterns, for the last full year, by employee group, type of absence, gender

and age group

2. Direct costs of absence, including the salary, NI, pension, bonuses and benefits of

those employees who are absent

3. Indirect costs of absence, including the costs of internal cover (overtime etc.) or

external cover (eg temporary or agency staff)

4. Absence management costs, including management time, HR or administrative time

spent managing absence

5. Information on benefits.

The costing tool was intended to collect data which was already held by the case study

organisations (eg absence patterns, salary data) as well as data which could be inferred

through questioning (eg estimates of time spent by line managers in the management

of absence).

While a key aim of the study was to collect data on the costs and benefits of absence

to employers, this proved exceptionally difficult for a number of reasons.

Availability of data

Most of the case study organisations found it difficult to provide data on their absence

patterns, the direct employment costs associated with these absence, and any indirect

or secondary costs. This was because:

l

These data did not exist at all (especially in the smaller organisations)

l

Only data on absence patterns was held

l

Data was held by different parts of the organisation and was difficult to co-ordinate.

In general, we found that even large employers with sophisticated HR systems and

personnel databases found it difficult to gather the data we asked for.

Willingness to provide the data

On a related theme, we found several employers unwilling to give us cost data

because:

l

Their initial willingness waned when they realised the effort required

l

They felt the data was commercially sensitive (eg the merchant bank became

sensitive about releasing any pay data in the light of a legal case on pay and gender

which they subsequently lost)

l

They argued that there was not sufficient benefit to them to collate the data

their efforts were better expended elsewhere.

In many cases we found employers initially happy to provide this data, but

subsequently unwilling. We were made many promises, but none were fulfilled. In most

cases we felt we pushed the employer as far as we reasonably could for these data. In

one or two cases we ran the risk of them withdrawing from the study completely.

11

In order to encourage employers to provide the data we adopted the following

strategies:

l

IES took HR managers and others (eg information systems people) through the data

sheets explaining the purpose and content. We highlighted where they would be

likely to be able to use existing data and where estimation might be needed.

l

IES suggested that only data on particular employee groups need be provided

to

simplify the task.

l

IES offered to provide either face-to-face or telephone support in the completion of

the forms.

l

IES offered to provide research officer support on the employers’ premises if lack of

internal resources was an issue.

None of them took advantage of the latter two options, despite our efforts.

As a result we have obtained only patchy data on costs:

l

The law firm has provided some data for some staff groups

l

The school was able to prove very basic data, which appears in the case study

l

The financial services firm promised to complete the whole costing sheet, but finally

was only able to provide data on absence patterns

l

Neither micro firm had data of this kind

l

The manufacturing company refused to provide data on the basis that it felt it

would derive no benefits from doing so

l

The merchant bank felt the data would be commercially sensitive.

Analysis and reporting

The fieldwork resulted in the collection of a large amount of both qualitative and

quantitative data. Analysis and synthesis of these data has:

l

Focused on the organisation as the primary unit of analysis

l

Been dominated by qualitative data from a range of sources (although not all

participating organisations were able to provide access to employees)

l

Relied less on comprehensive data on costs than was originally hoped. It became

clear that most participating organisations were unable to supply detailed or

comprehensive data on patterns of absence or costs.

The case studies have been written as narrative accounts, each within a business

context. These appear in Appendix A and contain both qualitative and quantitative

data. Table 1.1 summarises the case studies which are presented.

The main body of the report contains a description and analysis of:

l

The business and employment context within which the participants were operating

(Chapter 2)

12

l

The absence which the participants were experiencing and their formal policies to

manage them (Chapter 3)

l

The practical approaches being taken to managing the consequences of absence

(Chapter 4)

l

The costs and benefits associated with the management of absence (Chapter 5)

l

Emerging themes from the study as a whole and the implications for both employers

and policy makers (Chapter 6).

13

2.

Business and employment

context

The study was conducted during a period of economic growth, low unemployment,

widely reported skill shortages and general labour market buoyancy. In these

circumstances it might be expected that most employers would have a heightened

sensitivity to absence among employees.

In this chapter we will briefly assess the strategic business and employment issues that

were being faced by the case study employers. In doing so, we will seek to establish to

what extent employee absence had become a strategic impediment to the meeting of

key business goals.

Business strategy: markets and competitors

The public sector organisations which participated in the study (the school and the NHS

trust) had clear goals relating to the delivery of public services. These were set against

a range of externally determined standards and benchmarks (GCSE passes, patient

episodes, waiting lists, costs etc.). In these organisations there was a strong sense that

‘customer demand’ for these services was increasing at a faster rate than the resources

available to deliver them. In both public sector organisations it was clear that adequate

staffing levels were held to be critical to their ability to deliver the quality of service

expected of them.

In the private sector the participating employers had adopted business strategies

compatible with the markets within which they were operating.

l

The manufacturing company was seeking to defend its dominant market share

through price competitiveness, fast turnaround of production and rapid delivery

times.

l

The merchant bank was trying to differentiate itself from its close competitors by

offering clients high quality service, an integrated and global product portfolio, and

exceptional expertise among its staff.

l

The law firm was aiming to dominate the market within an emerging business-to-

business sector, by developing deep expertise and specialised services at a high

price and with high quality people.

l

The food retailer was seeking to regain recently eroded market share by competing

on ‘value for money’, cost reduction and by maximising convenience.

Each of these businesses, to a greater or lesser extent, was able to articulate its

strategy towards its target markets, its competitive position, and the specific

14

characteristics of its product or service offer with which it hoped to reach its target

market and compete successfully with its rivals.

Links to human resource (HR) strategy

Most of the espoused business strategies of the case study organisations made explicit

mention of the internal capability or resources needed to achieve business goals. We

were interested in the extent to which HR strategy in these organisations would be

consistent with (and derived from) business strategy. It was expected that this

relationship would be most critical where employees (rather than technology,

equipment etc.) played a central part in delivering competitive advantage.

Some examples will illustrate the extent to which such coherence was found in the

case study organisations:

l

In the merchant bank, the recruitment, performance and retention of high quality

traders and analysts were central to profit growth. This was manifested by its long

hours, high rewards and client-centred approach. While global, real-time information

systems were also critical, the firm made sure that looking after its people was a

strategic priority.

l

In the small engineering company, the need for specialist engineers with particular

sensitivity to product quality issues was a critical contributor to the delivery of high

quality products to clients in their niche markets.

l

In the small internet company, client demands for greater support and guidance

have meant that the skills base of the employees has had to shift from being

predominantly technical to embrace commercial and consultancy skills.

Across most of the case study organisations we found that the ‘people’ part of the

broader business picture was well understood and readily articulated. Organisations

seemed to have a view of the ideal ‘fit’ between their main business priorities and their

staffing needs. In most cases this did not manifest itself as an explicit HR strategy

indeed, in the smaller organisations there were no HR managers.

Overall, the core staffing concerns which most of the employers had, surrounded

recruitment and retention. The ability to attract suitably skilled employees and then to

retain their services long enough for them to add value to the business were dominant

concerns, especially with buoyant labour market conditions. Indeed, these pressures

were the most frequently cited staffing impediments to meeting business goals. These

pressures were also commonly cited as drivers for the broader use of policies and

practices aimed at helping employees improve their work-life balance.

Vulnerability to absence

Although the focus of the study has been the management of absence, taking the

wider business picture in the case study organisations, absence was in no case the

staffing issue which was currently causing most concern. Indeed, the manufacturing

company curtailed its participation in the study, claiming that the management of

absence was not of sufficient concern (compared with other priorities) to warrant

spending more time on it.

15

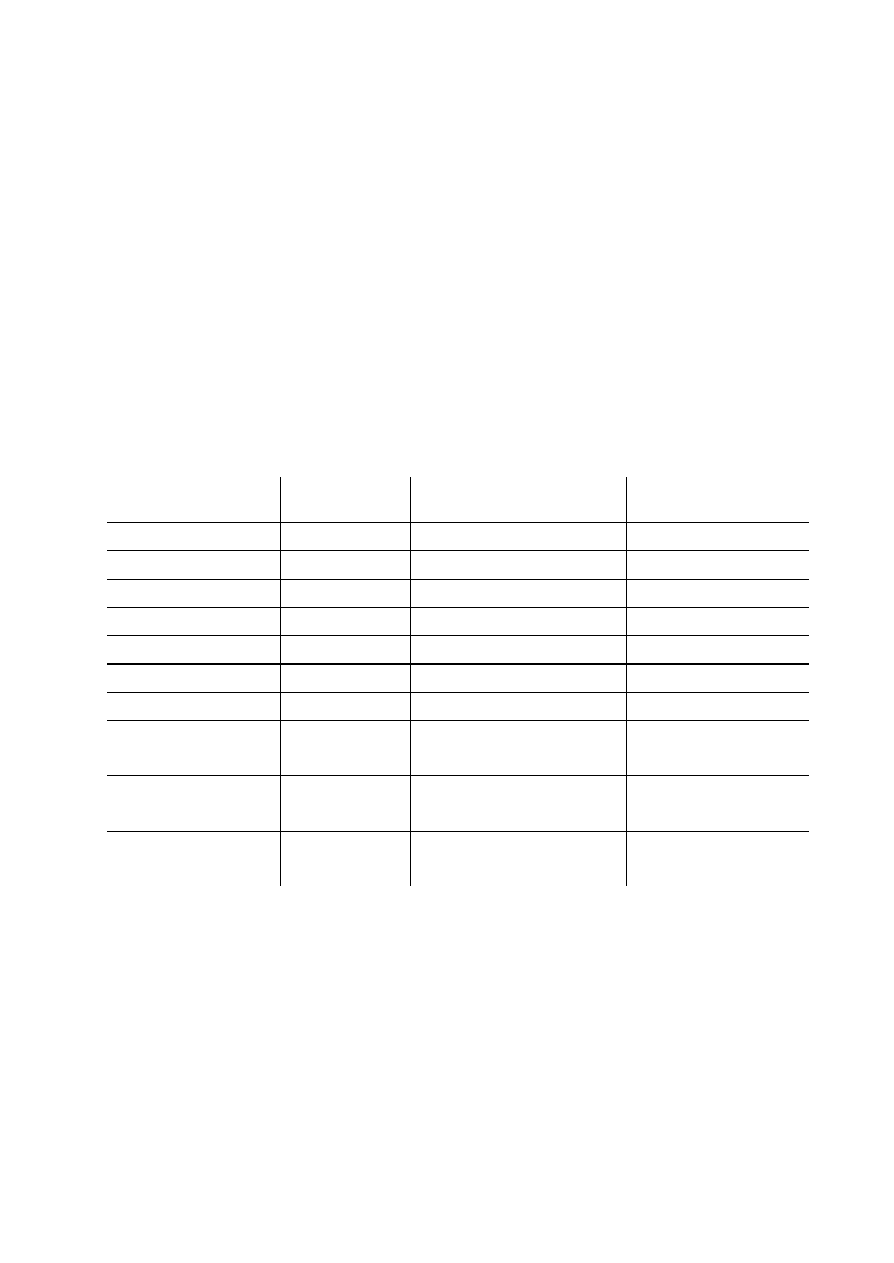

Nonetheless, there are circumstances where absence can have significant business

consequences. Indeed, it is possible to characterise the main business and employment

factors which might affect the vulnerability of organisations to absence. The typology

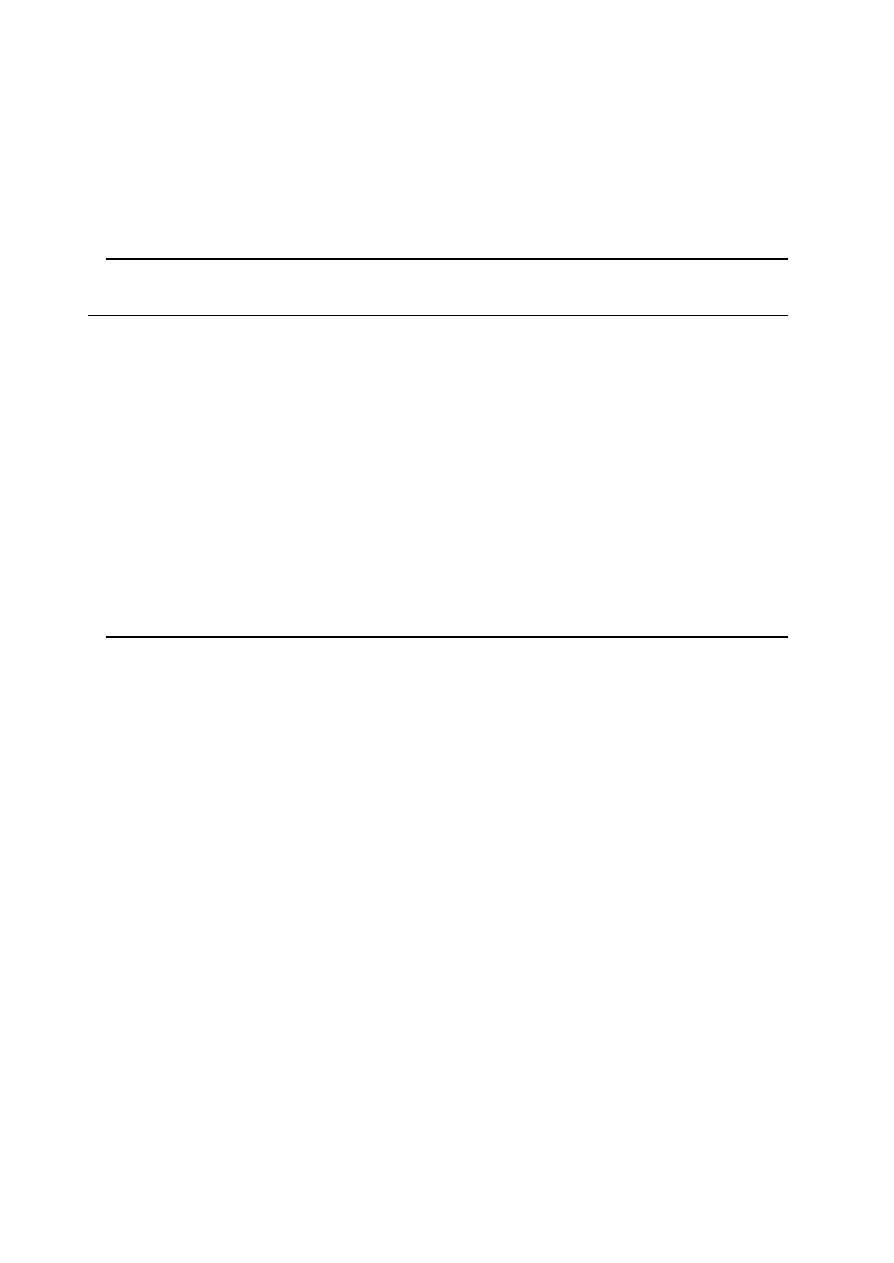

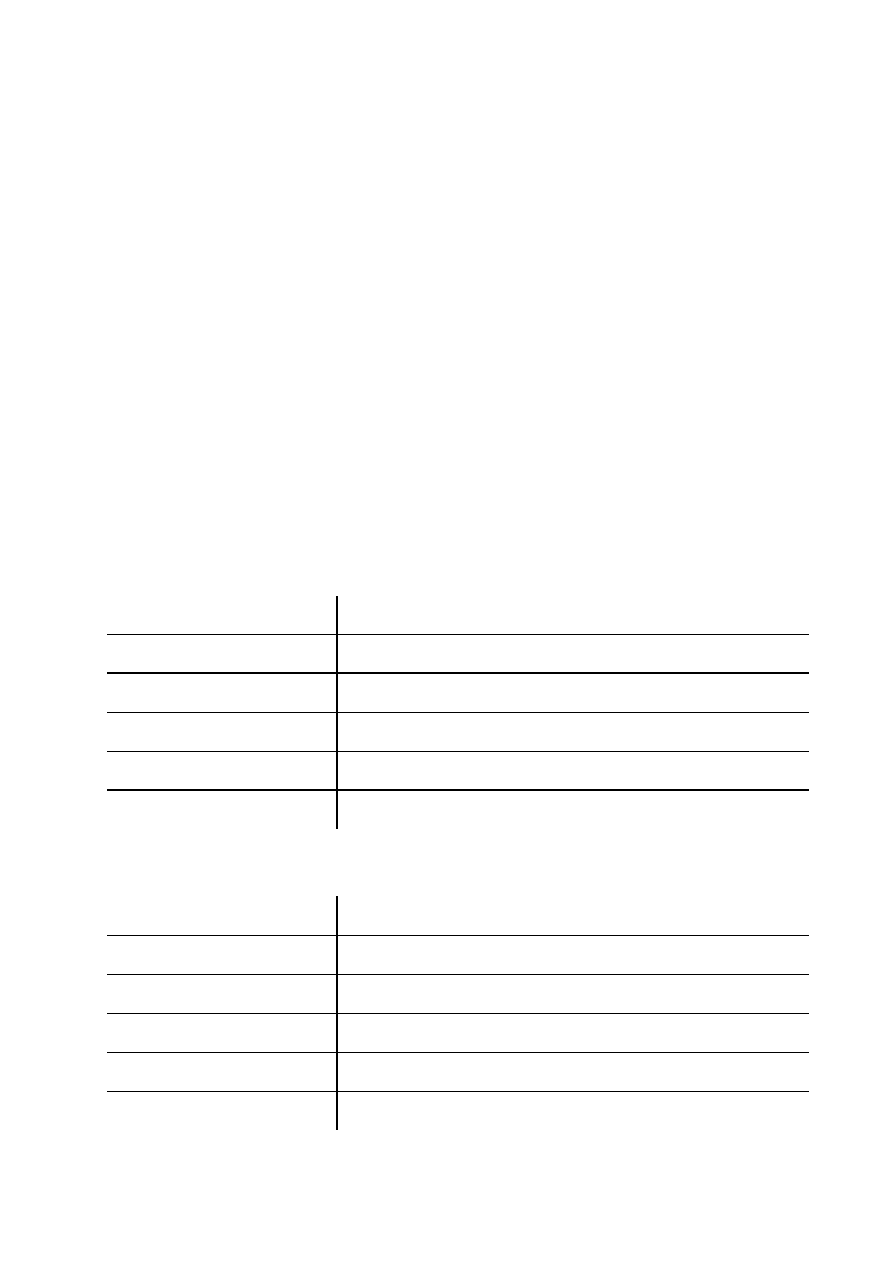

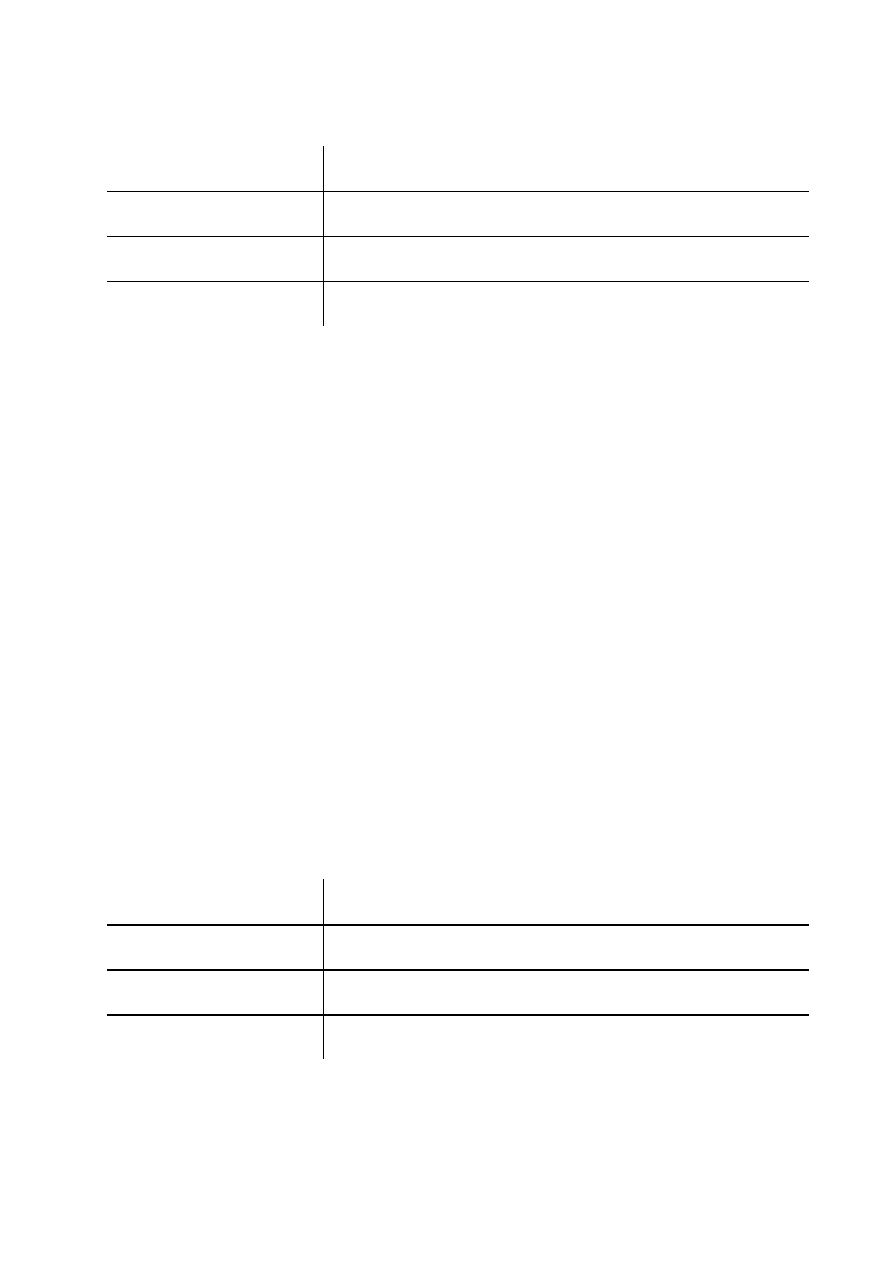

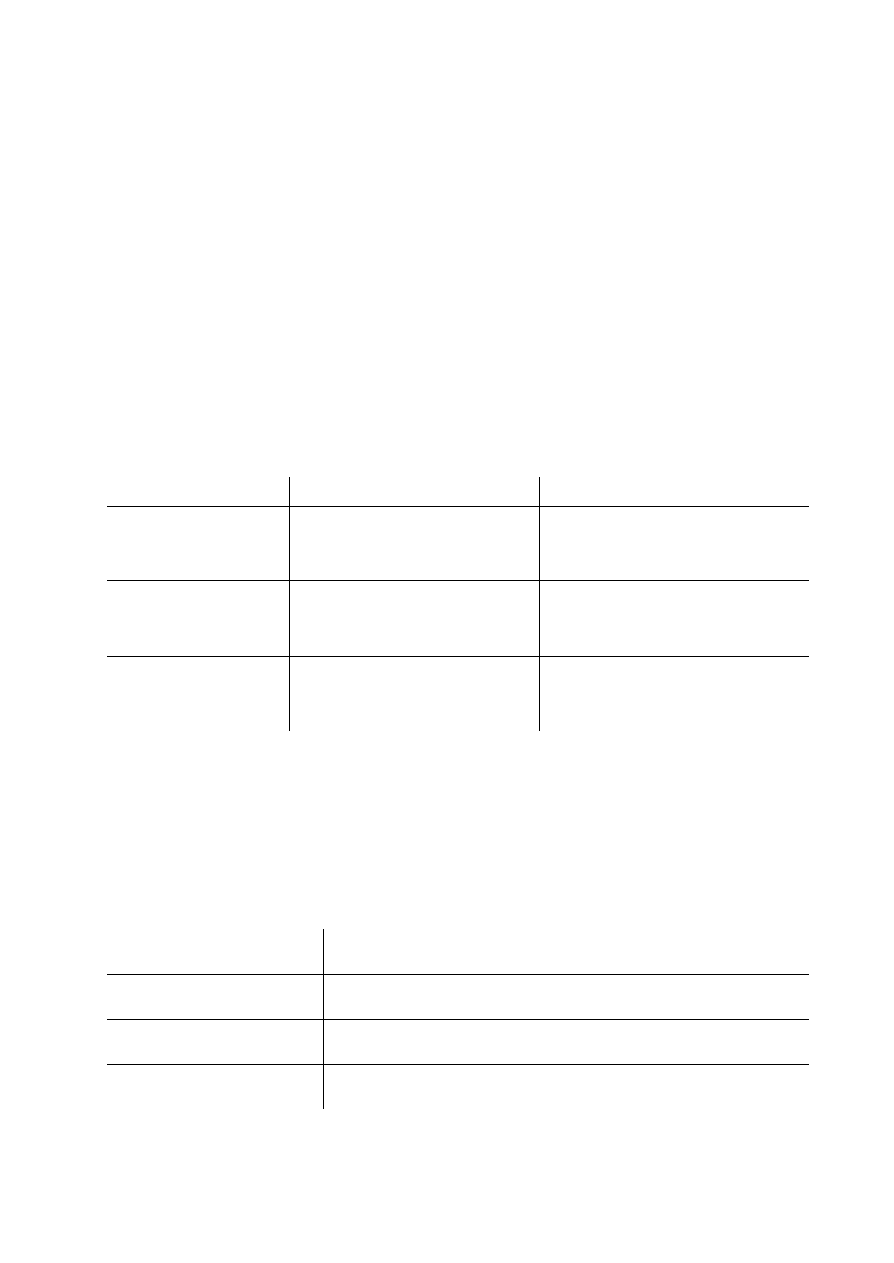

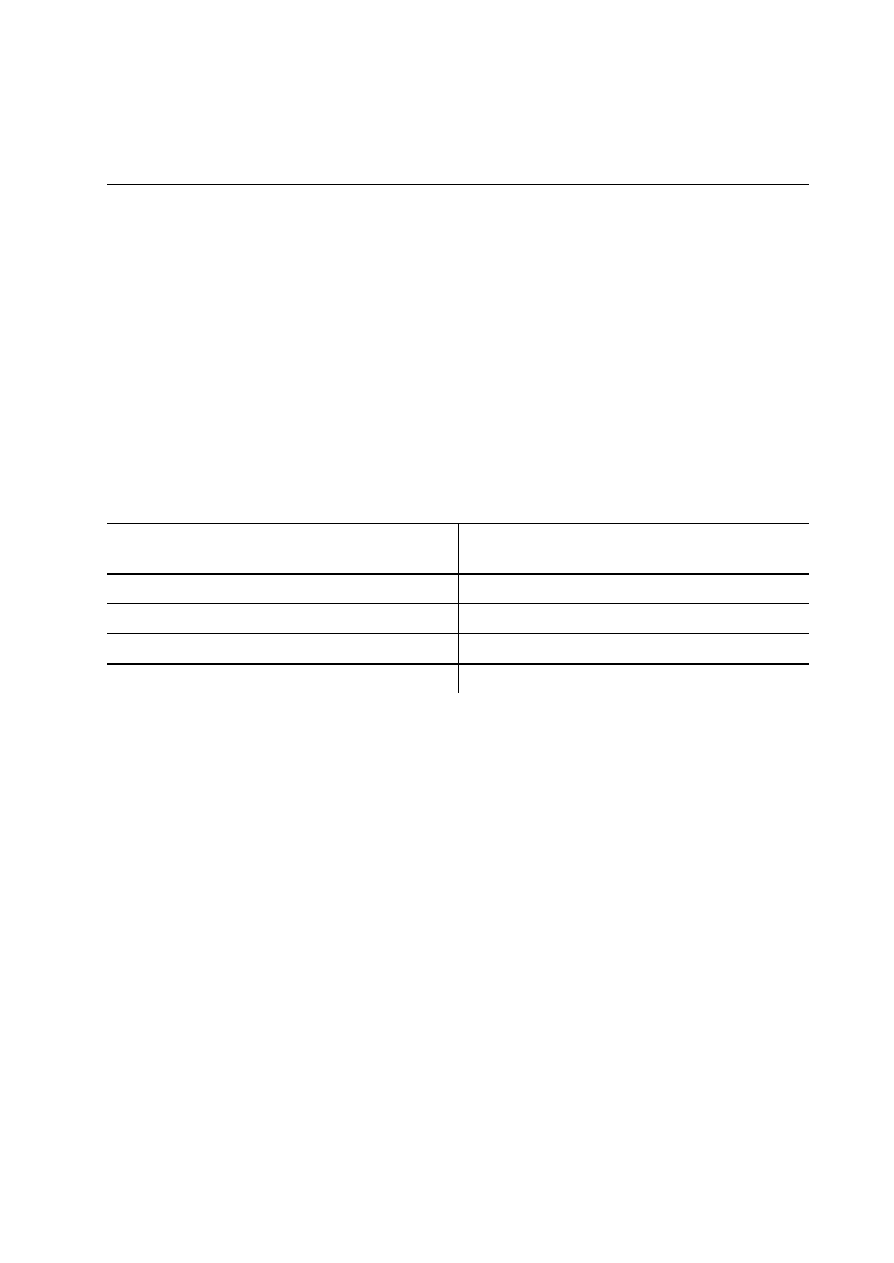

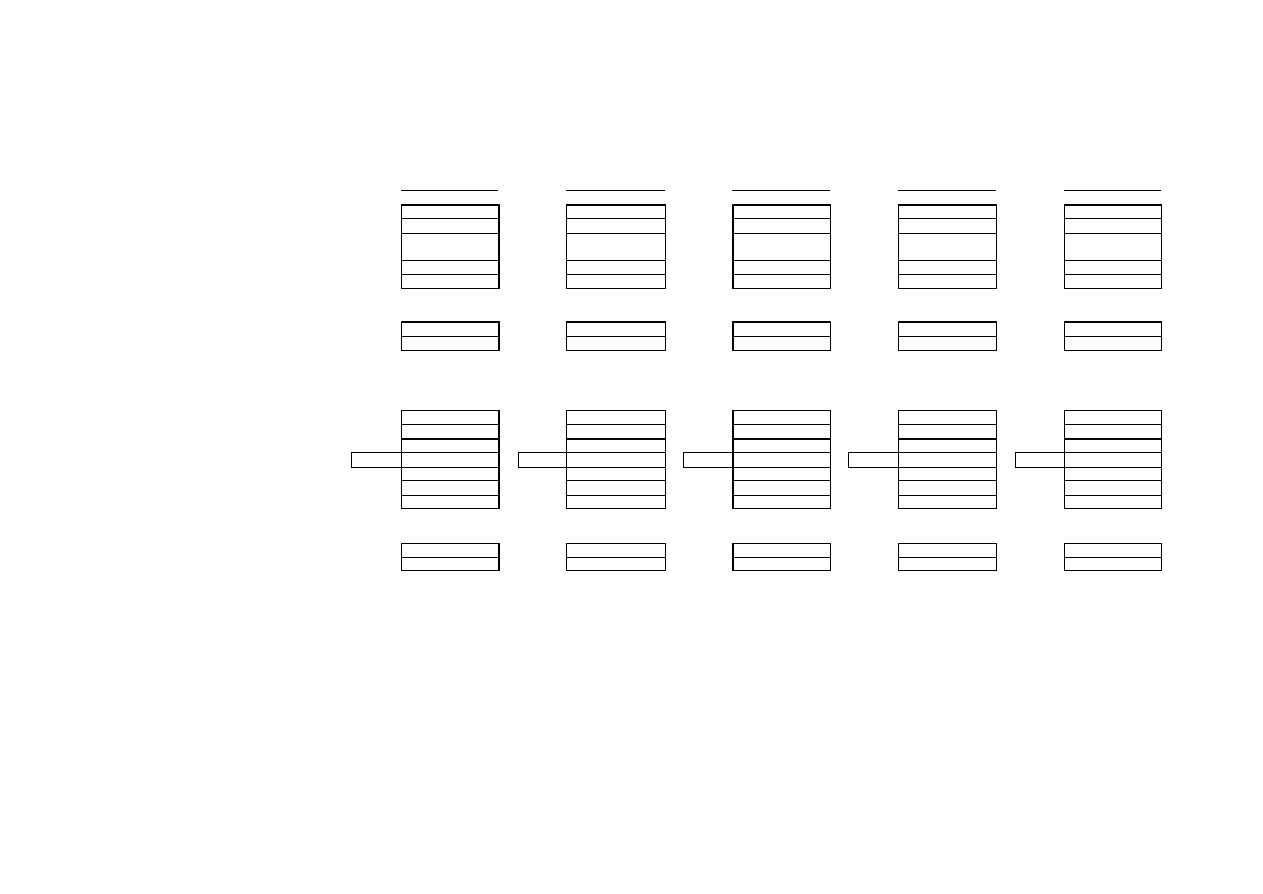

in Figure 1 is an attempt to do this.

This typology represents the two dominant aspects of managing absence which the

current debate suggests are of importance to employers. The first, Business Impact,

can include financial costs, non-financial costs (eg work quality), lost business, inability

to take on extra work etc. The second, Ease of Organising Cover, reflects the balance

between planned and unplanned absence and the extent to which either internal or

external skill substitution is possible. Firms in each of the four zones depicted in the

typology might have the following characteristics:

Zone A

Absence is difficult to cover and has a high business impact. Here, it might

be expected that this zone would contain firms with fewer skill substitution

opportunities, especially if competitive advantage was substantially derived from client

relationships, if the firm is small, if take-up of absence opportunities is high, and if a

high proportion of the absence is unplanned.

Zone B

Absence is relatively easy to cover but has a high business impact. Here,

firms may have a high degree of predictability in their absence (or readily substitutable

skills), making cover relatively easy to organise, but may still bear significant financial

and non-financial costs as a result of absence.

Zone C

Absence is relatively easy to cover and has low business impact. In these

firms, absence is easy to cover (high proportion of planned absence or readily available

Figure 1: Vulnerability to absence

Difficult to

cover

Low impact

on business

Easy to

cover

High impact

on business

D

A

C

B

16

substitution) and the consequences for the business are relatively insignificant (eg in

terms of cost, lost business etc.).

Zone D

Absence is difficult to cover but has low business impact. Here it might be

expected that a high proportion of absence is unplanned or is not easy to cover, but

that the business impact (either in terms of costs or lost business) is relatively low.

According to this typology, the scenario depicted in Zone A represents a state where

the balance between access by employees to legitimate absence from work and the

business consequences of granting such access, may begin to place intolerable costs

on business which are unlikely to be outweighed by any benefits. Conversely, the

scenario depicted in Zone C represents a situation in which (assuming the same level of

absence as in Zone A) most employee demand for absence can be met with acceptable

costs and business consequences, and in which a number of benefits to the firm

additionally accrue. For example, the need to provide cover for colleagues may

represent an opportunity for skill development and the broadening of experience for

those providing the cover. It might be hypothesised from this typology that the factors

likely to have most impact on a firm’s position in the model will include:

1. Levels of planned or predictable absence

the higher the level the lower the

impact on the business

2. The ease of internal or external skill substitution

the greater this is the lower the

impact on the business

3. The actual or perceived benefits accrued from granting employees access to policies

allowing absence

the greater these benefits the lower the impact on business.

The extent to which evidence from the case studies supports these hypotheses is

discussed in the remaining chapters of the report.

17

3.

The nature and extent of

absence

Introduction

As we have seen, the number of ways an employee may now be legitimately absent

from work has recently increased. This was reflected by the experiences of most of the

case study organisations.

This chapter discusses the different types of absence and their classification into

planned and unplanned absence. Chapter 4 looks at the implications of these different

groups of absence for managers, in particular the ways in which cover is arranged. All

types of absence matter to employers. Planned absence is easier to manage; by

definition, plans can be made to cope with this. Unplanned absence creates greater

problems. However, it is difficult to identify a precise level at which absence presents

particular difficulties. The nature of the business and competitive pressures all play a

role. These issues are discussed in Chapter 4.

Absence is an issue for employers, or time would not be devoted to developing

absence policies. The nature of policies is discussed later in this chapter. The types of,

and reasons for, introducing absence policies help to illustrate some of the pressures on

employers, and situations in which absence is problematic. For example, sickness

absence is a major concern for employers. Policies aim to monitor and proactively

manage sickness absence. Policies addressing other types of absence, for example,

ensure that legislative requirements are met, and set parameters and guidance to

employers and employees. These all aim to ensure consistency of treatment and

transparency within organisations.

In this chapter we explore:

l

The range of types of absence being experienced by organisations

l

Their formal policies relating to absence management

l

Trends in the patterns of absence being experienced

l

The factors underlying these patterns

l

Approaches to the measurement and monitoring of absence.

Examples from the case studies will be used to illustrate key points throughout the

chapter.

18

Types of absence

There are a number of ways in which absence can be categorised. They may be:

l

Unplanned or planned

l

Short-term or long-term.

In addition, absence may result from statutory rights or may be based on employer

discretion. Absence may also be paid or unpaid.

We found that the extent to which absence were planned or unplanned, and whether

they were short-term or long-term have particular implications for how cover is

arranged and the type of cover used. Each type of absence is discussed below. The

cover arrangements put in place to address each are discussed in Chapter 4.

Unplanned absence

The main type of unplanned absence encountered by case study employers was sick

leave, or at least absence which is attributed to illness. This type of absence is taken

for a range of reasons and these are listed below:

l

Genuine illness or injury

l

Illness amongst other family members, in particular children

l

High living at the weekend or during an evening

l

Childcare arrangements breaking down at short-notice. This is often attributed to

illness, particularly in organisations with little access to emergency leave and with

limited flexibility

l

Negative feelings about the job, managers, the organisation

l

Problems at work, eg poor relationships with other employees

l

A general feeling of being disaffected: ‘Other people take time off so why

shouldn’t I?’

In many case study organisations, managers talked about ‘Mondayitis’ and the

prevalence of sickness absence on Mondays and Fridays. This was something they

were looking to control.

Other types of unplanned absence include time off:

l

To deal with family and other domestic emergencies

l

When a dependant is ill

l

Due to bereavement

l

For medical or dental appointments.

In many cases, patterns of short-term and unplanned absence were perceived by

managers as attributable either to the disposition of the individual employee (for

example, likely to have Mondays off because of over-indulgence at the weekend), or to

the individual’s domestic circumstances.

19

Planned absence

Planned absence includes statutory leave and those under which an employer has some

sort of obligation, although not necessarily compulsion, to allow employees time off.

The main types of planned absence are:

l

Annual leave

l

Maternity leave

l

Paternity leave

l

Parental leave

l

Religious holidays

l

Career breaks, usually for family reasons

l

Sabbaticals, for example, to go travelling

l

Time for training and study

l

Trade union duties

l

Time off for civic duties, for example, jury service

l

Time off for involvement in various voluntary and community activities at the

discretion of an employer, for example, being a school governor or a member of the

Territorial Army.

All these types of absence refer to instances where employees are absent during their

‘normal’ working hours. There are also cases where individuals’ own ‘normal’ working

hours do not correspond with the ‘normal’ working hours of other employees or their

business unit, ie where employees have flexible working practices such as reduced or

alternative hours. This is not ‘absence’ in the same sense. Employees are performing

their usual work and most employers offer some form of flexible working. They do so

because they recognise it is beneficial to their business, eg it can boost morale, help

retain skilled staff and keep staff turnover low.

Again, in the course of the study the government also announced that it would be

introducing a right for parents of young children to request to work flexibly and have

the request seriously considered by the employer

1

. However, in conducting the case

studies, some employers talked about flexible working as a form of planned absence.

Once sickness becomes long-term it is nearly always treated as a form of planned

absence. The end point of this might be less clearly identifiable than that of other types

of planned absence. However, once it is known that an illness is going to last for a

matter of weeks or months, the way in which cover is approached has closer alignment

with planned absence. In some circumstances, for example, recovery from an accident

or surgery, absence is largely regarded as planned. An employer usually knows

approximately how long this is likely to take, or at least that the absence will continue

for a relatively prolonged period.

1

In June 2001 the Government announced that a Work and Parents Taskforce would be

established to look at how best to implement a legislative right for parents of young children

to request flexible working.

20

Long-term and short-term absence

The definition of long- and short-term absence is not precise. We found little evidence

that once an absence is over a certain number of days or weeks, it is regarded as long-

term. It is frequently more a question of degree. However, the length of an absence

does have implications for the type of cover which is seen as most appropriate. This is

discussed further in Chapter 4.

There is some relationship between the extent to which an absence is planned or not

and whether it is long- or short-term. Most longer-term absence is planned: for

example, maternity, paternity and parental leave, and long-term sick leave.

Most unplanned absence is short-term as, almost by definition, once an absence

becomes long-term it can be planned around. However, some types of planned absence

is also short-term, for example, time off for various civic duties.

While longer-term absence was commonly regarded as easier to manage on a day-to-

day basis, the high costs of compensation claims for work-related stress etc. were

causing considerable concern in both public and private sector organisations. Senior

managers have pressured HR and occupational health specialists to find solutions to

limit costs and promote well-being. In this context, it was surprising to find little

evidence of interest in preventing short-term sick leave from becoming long-term.

Policies

Policies relating to absence address three main issues. They set parameters for line

managers and employees through defining what is permissible and under what

conditions, for example, the number of days of emergency leave and whether these are

paid. In some organisations, rather than a definitive list, managers are provided with

tools for making decisions on a case-by-case basis about whether absence or flexible

working patterns should be allowed. This was the case in the financial institution. The

second type of policy addresses the management of absence. The main example here is

sick leave. Many organisations have a policy aiming to monitor and minimise this.

A further aspect of policy is the arranging of absence cover (and this is discussed in

Chapter 4). We came across few explicit policies in relation to this; rather,

organisations have a set of practices which are applied.

Policies defining rights to absence

Smaller firms are less likely to have written policies relating to any aspect of absence.

Depending on the nature of the firm, custom and practice define how absence is

managed. One of the very small firms we visited was unusual in having a written

employment contract which set out policies, for example, in relation to sick leave,

parental leave and emergency leave. This had come about due to bad experiences in

the past and the need to be explicit with employees about their basic rights. The

director in the other small firm had clear views about how employees should be

treated, and the responsibilities of employer and employee, but there was no explicit

policy on absence.

As a firm grows in size, the need for more explicit policies emerges. This is usually to