Tale of Bygone Years: the Russian Primary

Chronicle as a family chronicle

A l e x a n d r R u k a v i s h n i k o v

This paper aims to develop a new approach to the investigation of the oldest

Russian historical text, the Tale of Bygone Years or Russian Primary

Chronicle. The purpose of this study is to examine methods by which the

chronicler constructed the Riurikid princely dynasty from legendary

forefathers to the author’s own time. How did the contemporary political

situation at the beginning of the twelfth century influence the presentation

of the Riurikids of the ninth and tenth centuries? What was the place of oral

traditions within the work? How did the ideology of princely power

interact with the presentation of family and kinship?

Introduction

A movement of the 1970s, subsequently called the ‘literary turn’, proposed

a new dimension in historical studies. Analyses moved beyond the search

for historical truth or the gathering of historical facts so stereotyped in

research from classical – positivist and Marxist – schools. In medieval

studies, this has led to the investigation of historiographic and hagio-

graphic texts as products of their epoch.

1

Walter Goffart’s book on

Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede and Paul the Deacon

2

took a further

step as it stimulated medievalists elsewhere ‘to locate texts as precisely as

possible in their environment’ and to study carefully, where possible, an

author of a text; or, to put it another way, ‘reading a text necessitates the

assembly of as much data as possible about the author’s chronological,

geographical, social and cultural locations as a key to unlock historical

context’.

3

Goffart’s work has sparked further debates, focusing on the

1

For the key parameters of the ‘linguistic turn’ see: H. White, The Content of the Form: Narrative

Discourse and Historical Representation (Baltimore, 1978); G. Spiegel, The Past as Text: The Theory

and Practice of Medieval Historiography (Baltimore and London, 1997).

2

W. Goffart, The Narrators of Barbarian History: Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede and Paul the

Deacon (Princeton, 1988).

3

M. Innes, ‘Introduction: Using the Past, Interpreting the Present, Influencing the Future’, in

Y. Hen and M. Innes (eds), The Uses of the Past in the Early Middle Ages (Cambridge, 2000),

pp. 1–9, at p. 4.

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1) 53–74 # Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003, 9600 Garsington

Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden MA 02148, USA

degree of authorial intent that can be ascribed to often anonymous and

shifting early medieval works,

4

and Walter Pohl has shown that in

constructing the past authors and scribes were constantly revising received

material in the light of immediate and contemporary concerns.

5

Russian material has never been actively involved in this interesting and

useful discussion, which has opened new and fascinating approaches for

medievalists. For example, the Tale of Bygone Years or Russian Primary

Chronicle (RPC ), which develops a story of ninth-, tenth- and eleventh-

century Rus’, has never been studied as a source for twelfth-century

history, the time when it was finally formed. In this case the figure of the

author was vital as he was a direct constructor of the past; but another,

sometimes even more important, role was played by the commissioner of

the work. The commissioner set the parameters of the author’s work, and

the overall direction of his argument. The RPC was a creation of,

primarily, Russian princes and, then, of Russian educated monks: in

this article it will be argued that this fact is crucial for understanding the

RPC ’s presentation of the Russian past. Moreover, in offering a very

particular presentation of the distant past, the RPC can be seen as engaging

with what some historians would call a ‘collective memory’, as identified

with ‘the common cultural pool which informed a vision of the collective

past, explaining how and why present society came into being’.

6

‘Collect-

ive memory’, as it was constructed, helped to shape collective identity, but

in the case of the RPC it was a collective memory focused on the

transmission of princely power within the ruling dynasty. In this sense,

then, it may be possible to study the RPC as a family chronicle, drawing

on the recent work of Elisabeth van Houts on the dynamics of family

memory and the processes whereby originally orally transmitted stories,

after several generations of constant shaping and reshaping on account of

changing political and cultural contexts, were used as the basis for written

versions of the family past.

7

RPC: the text and context

The RPC is the main primary source on the early medieval history of Rus’.

It is a narrative telling us a story from the very beginning of human

4

P. Magdalino (ed.), The Perception of the Past in Twelfth-Century Europe (London, 1992); Hen

and Innes (eds), The Uses of the Past.

5

W. Pohl, ‘History in Fragments: Montecassino’s Politics of Memory’, EME 10 (2001), pp. 343–74,

at p. 349.

6

M. Innes, ‘Introduction’, pp. 6, 7.

7

E. van Houts, Memory and Gender in Medieval Europe, 900–1200 (Toronto and Buffalo, 1999).

See examples of changing genealogies of European aristocracy: J. Dunbabin, ‘Discovering a Past

for the French Aristocracy’, in Magdalino (ed.), The Perception of the Past, pp. 1–14; G.M.

Spiegel, Romancing the Past: The Rise of Vernacular Prose Historiography in Thirteenth-Century

France (Berkeley, 1993).

54

Alexandr Rukavishnikov

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

history – from the Flood and the division of lands between the three sons

of Noah – until 1110. There is a large body of historiography concerning its

date and place of composition, and its sources. There is no evidence of

historical writing in Rus’ before the conversion to Christianity in 988.

Commercial and political treaties with the Greeks (911, 944, 971) inserted

in the RPC were written in Greek and translated (and also edited) in the

late eleventh or twelfth century. Some facts on Russo-Byzantine relations

in the ninth and early tenth centuries (for example, of the raid on

Constantinople in 860) were extracted by the author of the RPC from

the Continuation of George the Monk or, in two or three instances, from

other Byzantine sources.

8

Evidence of writing in the Russian vernacular

begins with the sermons of Archbishop Ilarion (c.1030–1040s), but there is

nothing to suggest that there was any Russian chronicle written in the first

half of the eleventh century. It is clear that the RPC ’s written sources were

complemented by material that was transmitted orally.

9

We can even

name several of the sources for these oral traditions among the high

nobility: the tysiatskii (military commander of a high rank) Ian Vyshatich

and his father, and also tysiatskii Vyshata. The RPC tells us that Ian died in

1106, at ninety years of age. The author of the RPC states that ‘he heard

many stories from him, which he used [inserted] in the chronicle’.

10

The

role of these individuals is reminiscent of the role of the Norman court in

shaping the parameters of Dudo of St-Quentin’s history of the Normans

(written between 996 and c.1020), according to the recent arguments of

scholars such as Eric Christiansen and Eleanor Searle. Christiansen’s

conclusions on Dudo – firstly, that ‘Dudo is not a reliable source for the

early history of the Normans; nor did he know of any; nor do we’,

11

and

secondly, that ‘he was not so much an author as a transmitter to posterity

of a body of material already formed in the memories and traditions of

some historically-minded Norman body: the family of the ruler, the

household warriors, the nobles, or the itinerant professional entertainers

of the period’

12

– suggest important questions to be posed of the RPC and

its sources.

There are three main versions of the text. The first version was

preserved in the Laurentian Chronicle (1377); the second in the Ipatian

8

S. Franklin and J. Shepard, The Emergence of Rus, 750–1200 (London and New York, 1996), p. 57.

See also I. Sorlin, ‘Les premie`res anne´es byzantines du Re´cit des temps passe´s’, Revue des e´tudes

slaves 63 (1991), pp. 8–18, at pp. 15–17.

9

N.K. Chadwick, The Beginnings of Russian History: An Enquiry into Sources (Cambridge, 1946),

p. 25; 2.?. 9VcNeSP, ‘=\PS_‘j P^SZS[[ic YS‘ (V_‘\^VX\-YV‘S^N‘a^[iW \eS^X)’, in 0.=.

.[R^VN[\PN

-=S^S‘d (ed.), =\PS_‘j P^SZS[[ic YS‘, 2 vols (Moscow and Leningrad, 1950),

II, 1–149, at p. 36.

10

=\Y[\S _\O^N[VS ^a__XVc YS‘\]V_SW

(Moscow, 1997), (hereafter =?>9), I, 281 (text).

11

E. Christiansen, ‘Introduction’, in Dudo of St. Quentin, History of the Normans, trans.

E. Christiansen, (Woodbridge, 1998), p. xv.

12

Christiansen, ‘Introduction’, p. xvii.

The Russian Primary Chronicle as a family chronicle

55

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

Chronicle (c.1410–1420s); and the third version in the Commission and

Academic copies (mid-fifteenth century) of the Novgorodian First

Chronicle.

13

For several reasons the Laurentian Chronicle remains the

best for reconstructing the twelfth-century text. Firstly, amidst all other

copies of the RPC it is the oldest one (1377) in which the text of the whole

chronicle was preserved. Secondly, only the Laurentian version includes a

note at the end, stating that ‘Silvestr, hegumen of St Michael’s [mon-

astery], hoping for favour from God, wrote these books named Chronicle

at []^V] prince Vladimir’s [court]. He was reigning in Kiev and I was

hegumen of St Michael’s [monastery] in 1116.’ The note ends with a

request for commemoration of Silvestr in prayers, underlining the

connection between Christian commemoration of the dead and remem-

brance of the past.

14

In all other copies the RPC is followed immediately by

the text of other, later chronicles and only in the Laurentian does this

concluding note survive.

There are many difficulties with the RPC. First of all, it is impossible to

say for certain that any of the surviving versions have not been edited

since 1116. In addition, we cannot be sure that there was only one author,

the Silvestr mentioned in the Laurentian version. In fact, there is a strong

case that there were several earlier versions of the text, which were not

transmitted to the present. There is a voluminous historiography con-

cerning a number of hypotheses – which this essay will only skirt –

including A.A. Shakhmatov’s theory that the Commission and Academic

copies preserved an earlier version of the RPC written in 1093–1095, and

other attempts to identify the author of the final version of the RPC as

Nestor, a monk of the Caves monastery in Kiev, writing in the early 1110s.

In terms of the prehistory of the surviving texts, it is striking that precise

dating and detailed descriptions begin in the 1060s; this might indicate

that the earliest original written layer of the chronicle dates to this period.

15

Inner contradictions, such as the case of prince Vseslav of Polotsk, who is

13

The best edition of Russian chronicles so far is a new publication of =\Y[\S _\O^N[VS ^a__XVc

YS‘\]V_SW

(Full Gathering of Russian Chronicles) started in 1997. The first volume, the

Laurentian Chronicle, was published in 1997; the second volume, the Ipatian, in 1998; the

third volume, the Commission and Academic copies, in 2000 (;\PQ\^\R_XNm ]S^PNm

YS‘\]V_j _‘N^fSQ\ V ZYNRfSQ\ VUP\R\P

). The advantage of this edition is a new textual

review of all copies of the RPC by B.M. Closs and in some indices. I have used this new edition

for references, but it is worth noting that the text of the chronicles was just reprinted from earlier

editions, so it is possible to use them as well. The translation of the RPC into English by

S.H. Cross and O.P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor (Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text) was

published first in 1930, with a third reprint from the Mediaeval Academy of America Publication

60 (Cambridge, MA) in 1973. It is not as accurate as one would wish, so I have made my own

translations into English. Those who wish to check may find the relevant passages in the Cross/

Sherbowitz-Wetzor translation.

14

=?>9

, I, 286 (text).

15

The best book on the beginnings of the writing of the RPC continues to be: :.2. =^S_[mX\P,

6_‘\^Vm ^a__X\Q\ YS‘\]V_N[Vm

XI–XV PP, 2nd edn (St Petersburg, 1996).

56

Alexandr Rukavishnikov

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

mentioned as being still alive at the time the chronicle was written (R\

_SQ\ R[S

), but whose death is described under the year 1101,

16

remind us of

Dmitri S. Likhachev’s warning that ‘Russian history as it is presented in

the Tale of Bygone Years has itself the history of its creation, which is not

brief.’

17

In writing of an author or chronicler, we must understand that it

might not be one individual, but several, or rather, that we are dealing

with the final shaping of a composite and shifting text drawing on a variety

of traditions. In such a case, Silvestr’s work looks like only one link in a

chain of numerous rewritings of the chronicle, but his status at Vladimir

Monomakh’s court and the presence of his note in a copy of 1377 (which

was done 250 years later) prove that the hegumen’s work was of a

paramount importance and he really did compose, and not simply

copy, the text.

Nonetheless, as Christiansen and Searle have shown for Dudo, it is

important to study a text in the context of the time and place in which it

was finally shaped, and here the connection between the earliest extant

version of the RPC and Silvestr’s note of 1116 is of paramount importance.

As we have seen, the text runs from Noah until 1110, the time contem-

porary to Silvestr. There is a gap of six years between the last entry in the

RPC and the note. All this survives in a chronicle of 1377, rewritten by

scribes several times in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries (after Silvestr’s

note follows the text of the Suzdalian Chronicle – named after the city of

Suzdal’ in the north-east of Russia – running from 1111 till 1305). We

cannot be sure that there were no texts interpolated into the RPC after

1116, but there are strong arguments that there was no major rewriting, for

the Ipatian Chronicle, which has only minor differences to the Laur-

entian, was preserved independently in the Ukrainian (Volynia) tradition.

Furthermore, the Commission and Academic copies, in which the text of

1045–1074 is similar to the Laurentian, come from Novgorod (in north-

west Russia) and again were independently compiled. So there are strong

arguments that the final version of the RPC was finished in Kiev, c.1110–

1116, and then copied throughout Rus’ as an authoritative work on the

origins of Rus’ and Russian princes. We can therefore treat the RPC as a

narrative receiving its final shape at the beginning of the twelfth century in

Kiev and preserved in the Laurentian copy, which was made by a

Suzdalian monk, Laurentii, in 1377.

What do we know about Silvestr, hegumen of St Michael’s? What does

this strange note about writing ‘at prince Vladimir’ (]^V X[mUS

0YNRVZV^S

) in Silvestr’s famous inscription mean? Answers to these

questions will certainly help us to understand the context of Silvestr’s

16

=?>9

, I, 155, 274.

17

9VcNeSP

, ‘=\PS_‘j P^SZS[[ic YS‘’, II, 133.

The Russian Primary Chronicle as a family chronicle

57

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

work. Most of the ecclesiastical career of the hegumen Silvestr has fallen

into oblivion. He first appears in 1115 during the transmission of St Boris’s

and St Gleb’s relics to the stone church in Vyshegorod (Kiev’s ‘satellite

town’ or prigorod), when he is described as hegumen of St Michael’s

monastery in Vydubichi, one of the Kievan suburbs. On 1 January 1119 he

became the bishop of Pereyslavl’ and died in this position in April 1123.

18

Throughout Silvestr’s career, the dominant political figure was Vladimir

Monomakh (1053–1125), the prince of Kiev from 1113–25. There were very

strong links between these two men. Vladimir’s father, Vsevolod, was the

grandson of Vladimir the Saint (the first Christian prince in Rus’, who

ruled in Kiev from 980–1015), and the third son of the Kievan prince

Iaroslav. After Iaroslav’s death in 1054, Vsevolod received Pereyaslavl’ as a

patrimony, but his high status allowed him to found a monastery in Kiev,

dedicated to St Michael and under the control of St Michael’s church.

Construction was started in 1070, and finished in 1088. Vsevolod was the

Kievan prince from 1078–1093, while his sons, Vladimir Monomakh and

Rostislav-Michael

(1070–1093),

controlled

Pereyaslavl’.

Vladimir

remained the prince of Pereyaslavl’ until 1113. After moving to Kiev,

Pereyaslavl’ was governed by his son, Iaropolk. The positions of hegumen

at St Michael’s and the bishopric of Pereyaslavl’ were thus under the firm

control of first Vsevolod, and then his son, Vladimir Monomakh.

Silvestr was thus a close follower of Vladimir’s, and his note ‘at prince

Vladimir’ we thus have to decode as ‘at prince Vladimir’s court’, ‘at his

guidance’. If we look at the RPC ’s account of the late eleventh and early

twelfth centuries we find a number of entries praising prince Vladimir.

For example, under the year 1097 we have the characteristic: ‘Vladimir

_

loves the metropolitan, the bishops, the hegumens, and loves monks and

nuns still more. They come to him and he feeds them and gives them

drink, like a mother to her children. If he sees somebody noisy or agitated,

he never condemns, but is loving and calming.’

19

During the crucial wars

against the Kumans at the beginning of the twelfth century, Prince

Vladimir’s role was vital. After the 1103 victory, defeating the Kumans,

the Pechenegs and the Oguz, Vladimir – and not Sviatopolk, the Kievan

prince – summoned all the Russian princes for a feast and ‘gave alcohol

[O^Nf[\] to all the warriors’.

20

There is no doubt that Vladimir was

patronizing Silvestr’s work and that Silvestr was rewriting the RPC, in the

form we can observe in the Laurentian Chronicle, for this particular

prince.

18

=?>9

, II, 280; I, 291, 293.

19

=?>9

, I, 264 (text): ‘0\Y\RVZS^h

_ YlO\Pj VZSm X ZV‘^\]\YV‘\Z, V Xh S]V_X\]\Zh, V

Xh VQaZS[\Z

, ]NeS TS V eS^[Sej_XiV eV[h YlOm, V eS^[VdV YlOm. =^Vc\RmgNm X [SZa,

[N]V‘NfS V [N]NmfS

, NXi ZN‘V RS‘V _P\m. .gS X\Q\ PVRmfS YV flZ[N, YV P X\SZ

UNU\^S

, [S \_aRmfS, [\ P_m [N YlO\Pj ]^SXYNRNfS, V a‘SfNfS.’

20

=?>9

, I, 279 (text): ‘RNY S_V _Vc O^Nf[\ YlRSZ >a_j_XiZ’.

58

Alexandr Rukavishnikov

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

Claims to princely power in late eleventh- and early twelfth-century

Rus’ rested on descent from St Vladimir. Each line of Riurikids ruled its

own patrimony. Kiev was the main political centre of Rus’, the site of the

metropolitan see, and the richest and biggest city in Eastern Europe; and

by convention was usually ruled by the eldest, most powerful Russian

prince. There were no exact rules of succession in Rus’: brother might

follow brother, son his father, nephew his uncle. Everything depended on

the specific political situation, in which the role of local (city) elites of

nobility and merchants was significant in determining allegiances. Vlad-

imir Monomakh was not the eldest of St Vladimir’s descendants in the

1110s, but the most powerful one. His prestige by that time was extremely

high: he was the grandson of the Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI

Monomakh; and his first wife, Gytha, was the daughter of the last Anglo-

Saxon king, Harold. Furthermore, he had close matrimonial ties with

almost all the ruling families of Europe. Vladimir’s men were fighting

with Byzantines in Bulgaria (the Lower Danube region) in 1116–1117,

following in the footsteps of Vladimir’s famous forefather Sviatoslav,

whose career is vividly recounted in the RPC. It is possible to characterize

Vladimir’s power over Rus’ as virtually absolute. He reigned in Kiev and

his sons controlled Novgorod, Pereyaslavl’, Volynia, Turov, Smolensk,

Minsk, Suzdal’ and Rostov: almost two-thirds of all Russian land. All

Riurikids hostile to Vladimir’s regime were either incarcerated, like Gleb

of Minsk, or went to exile, as did Iaroslav of Volynia. Vladimir and his

sons controlled the famous Russian trade route ‘from the Varangians to

the Greeks’, i.e. the route from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Can we relate

the version of the past constructed in the RPC to this political situation?

Riurik, Oleg and Olga: constructing origins

In reading the RPC’s story of the first Russian princes, from Riurik to St

Vladimir, we are dealing with a literary work – and, as in a good story, we

have all types of characters in it. Each character acts according to

the narrative’s demands. The story was given its final shape in the 1110’s

by the hegumen Silvestr, under the close guidance of Prince Vladimir

Monomakh. The chronicler starts the family story with a progenitor: the

leader of the Varangians-Rus’, Riurik, and his two brothers, Sineus and

Truvor (see Table 1). As V. Thomsen demonstrated a century ago, all three

bear Scandinavian names.

21

The story tells us that after the expulsion of the

Varangians there were cruel wars between the different peoples of the Slavs

(Slovene and Krivichi) and the Finno-Ugrians (Meria), so they decided to

invite the Varangians-Rus’ to reign over them. So along came Riurik and

21

V. Thomsen, The Relations between Ancient Russia and Scandinavia and the Origin of the Russian

State (Oxford and London, 1877).

The Russian Primary Chronicle as a family chronicle

59

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

his brothers, and took power (Riurik placed himself in Novgorod – or in

Ladoga, according to another version – Sineus in Beloozero, and Truvor

in Izborsk). Together they governed the Slovene, Krivichi, Meria, Ves’

and the Muroma (the Slavs and Finno-Ugrians), until after the death of

Sineus and Truvor, Riurik seized sole power and ruled alone until his own

death. We know nothing about Riurik from other sources. Clearly, ‘it is

impossible to verify the historical base of the story’.

22

What the story does

do is emphasize the role of Riurik as a progenitor of the dynasty and the

first ruler of a huge territory in the north-eastern corner of Europe. Other

than the invitation, the RPC only tells us that before his death Riurik – his

son, Igor, being too young to rule – transferred power to Oleg, his

relative.

23

The author uses a special lexicon in both episodes – ‘to take

power’ (]^Vm PYN_‘j), ‘to possess power’ (\OYNRN‘V, PYNRS‘V), ‘to

transmit the reign’ (]^SRN_‘j X[mTS[jS). We have a legitimating story

of the genesis of Riurikovichi power over Rus’. I cannot agree with

Mel’nikova and Petrukhin, that the invitation to Riurik and his brothers

was ‘a boundary event, connecting myth and history according to the aims

of early historical description’.

24

There is no division between myth and

history in the RPC. It is all one story, one long narrative, without any

stages and periods. It is, rather, modern historians who are concerned to

delineate between myth and history, and place their belief in historical

dates. The chronicler’s inclusion of dates from 852 was not because he was

sure that before this there were only myths, nor was it due to him

searching for a ‘boundary event’ between myth and history. In fact, in

22

3

... :SYj[VX\PN and 0.M. =S‘^acV[, ‘9SQS[RN \ ‘‘]^VUPN[VV PN^mQ\P’’ V _‘N[\PYS[VS

R^SP[S^a__X\W V_‘\^V\Q^NbVV

’, 0\]^\_i V_‘\^VV 2 (1995), pp. 44–57, at p. 50.

23

=?>9

, I, 20–2 (text).

24

:SYj[VX\PN

and =S‘^acV[, ‘9SQS[RN \ ]^VUPN[VV PN^mQ\P’, p. 49.

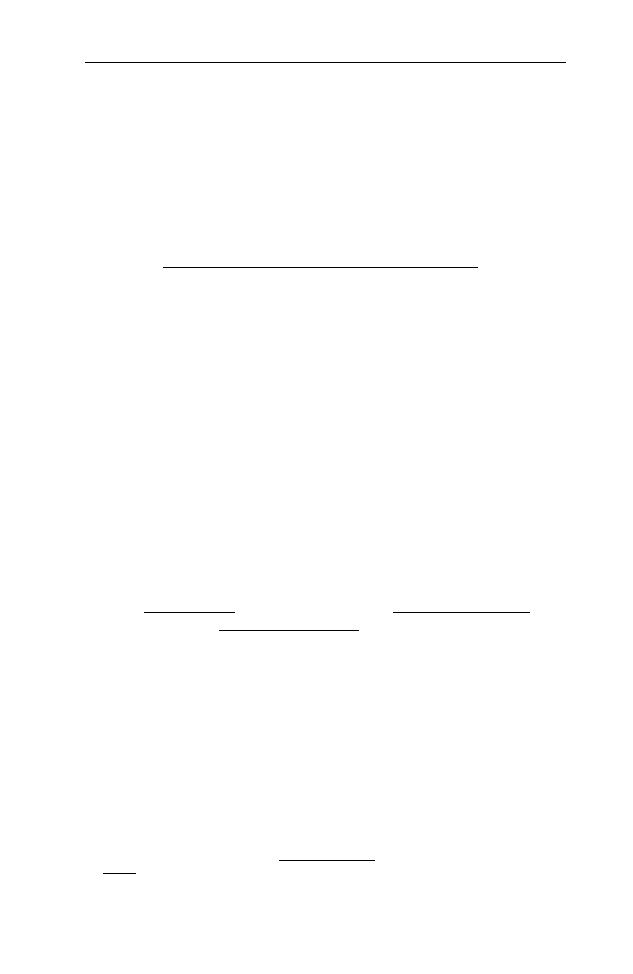

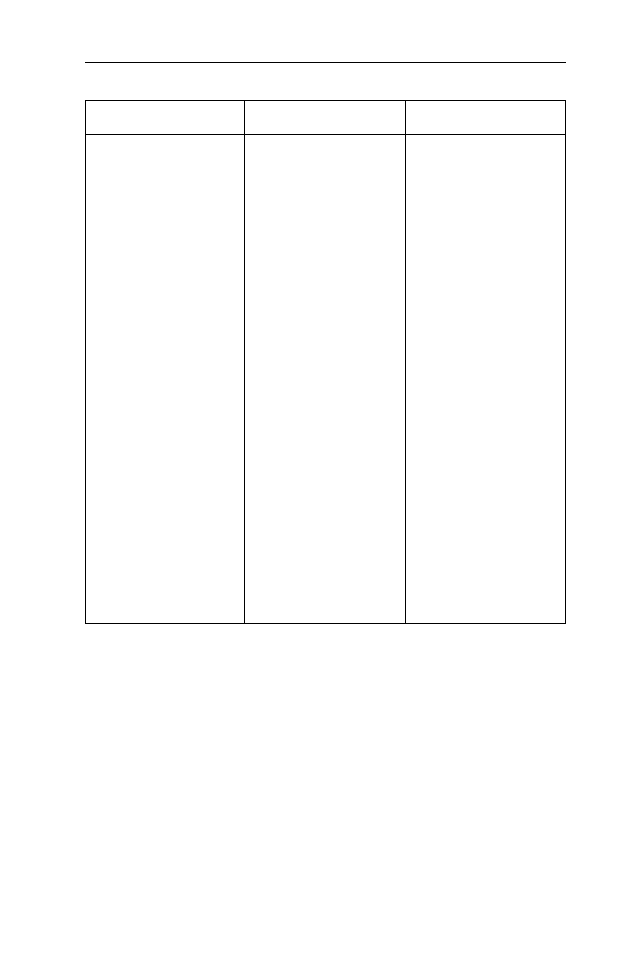

Table 1. The genealogical table of Russian princes in the

ninth and tenth centuries.

Riurik

d. 879?

|

Igor

Olga

d. 945?

|

d. 969?

|

Sviatoslav

d. 972

1. ?

| 2. Malusha

|

|

|

Iaropolk

Oleg

Vladimir

d. 980?

d. 977?

d. 1015

(no children)

(no children)

|

all Russian princes

60

Alexandr Rukavishnikov

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

establishing an origin legend that framed the power of the Riurikids as a

guarantee of order, and creating a template for the circulation of power

within a wide kin group, the story of Riurik provided a legitimizing

template for the political system. Another point is that the story explains

for the twelfth-century audience why Novgorodians have the right to

choose any Riurikid to govern them – a tradition vividly depicted in the

Suzdalian Chronicle (1169): ‘for a long time Novgorodians are free by the

forefathers of our princes, but even if it is so, if our first princes ordered

them to break the cross-kissing and shame their grandsons and great-

grandsons?’.

25

The circulation of power within a wide kin group is most clearly shown

by the RPC ’s treatment of two other figures whose careers are located in

this period: Askold and Dir. The RPC tells the story of two of Riurik’s

nobles not of his kin – Askold and Dir – asking their leader to send them to

attack Constantinople. Riurik permitted this and they sailed down the

Dnieper and came to Kiev and conquered the city.

26

The archaeology of

Kiev strongly suggests that there was no fortress or trade point until the end

of the ninth century, and Askold and Dir are not mentioned in other

sources. There is a detailed description of a Rhos attack on Constantinople

in 860, recorded by the patriarch Photius, and also by the Greek chronicler

in the Continuation of George the Monk, but no names of the Rus’/Rhos

leaders are reported.

27

The author of the RPC took the information about

this raid from the Continuation (866 in the RPC). Here the RPC uses

Askold and Dir to connect this raid with Riurik, with the passage

explaining that Riurik sent them to attack Constantinople. This follows

a similar logic to Dudo’s presentation of early Norman politics, in which

all known raids of independent Viking leaders in the late ninth and tenth

centuries were attributed to the legendary progenitor of the Norman

rulers’ dynasty, Rollo, or leaders (nobles) dependent on him.

28

Linguistic-

ally, Askold is probably a Scandinavian name,

29

but the derivation of Dir is

unclear; indeed the name is otherwise unattested. According to the RPC,

after the death of Riurik the new prince, Oleg, organized a military

expedition against Askold and Dir (882 in the RPC). He went with the

young Igor to Kiev, and found that Askold and Dir were rulers there.

Oleg hid some warriors in boats, others he left in the back

_ and Oleg

sent to Askold and Dir saying that he was Oleg’s and Igor’s merchant

25

=?>9

, I, 362 (text): ‘VURNP[N _a‘j _P\O\TS[i ;\PQ\^\RdV ]^NRSRi X[mUj [NfVc, [\ NgS

Oi ‘NX\ OiY\

, ‘\ PSYSYV YV VZh ]^SR[VV X[mUV X^S_‘h ]^S_‘a]N‘V VYV P[aXV VYV

]^NP[aXV _\^\ZYm‘V

’.

26

=?>9

, I, 20–1 (text).

27

Photios, Homilies, trans. C. Mango, Dumbarton Oaks Studies 3 (Washington, DC, 1958), pp. 82,

96–101; Theophanes Continuatus, Chronographia, ed. I. Bekker (Bonn, 1838), pp. 826–7.

28

Dudo, History, pp. 32–4, 42.

29

V. Thomsen, The Relations, p. 68.

The Russian Primary Chronicle as a family chronicle

61

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

sailing to the Greeks, and invited them to come. Askold and Dir came.

Oleg’s warriors, hidden in the boats, surrounded them, and Oleg said

to Askold and Dir: ‘You are not princes and not of their kin, but I’m of

their kin and this is (he showed Igor) the son of Riurik.’ And then his

warriors killed Askold and Dir

_ Oleg started to govern in Kiev.

30

This is a very significant episode, telling the reader that only Riurikovichi

or their kinsmen may rule in Rus’. Compare the RPC ’s similar treatment

of the Derevlians (the Slavic tribe in the Middle Dnieper region): when

the Derevlians kill Igor in 945, and Derevlian noblemen plan to marry

their prince, Mal, to Igor’s wife, Olga, and murder her son Sviatoslav, the

best Derevlians are cruelly destroyed by Olga, and Prince Mal ‘disappears’

from the pages of the chronicle. Like Askold and Dir, Mal is a potential

claimant whose failure is presented in terms of his lack of Riurikid blood.

31

Again we see the importance of Riurikid legitimacy for the chronicler,

who once more stresses the idea of the Riurikovichi’s unique right to

possess Rus’ as their own household (see Oleg’s words to Askold and Dir:

‘You are not princes and not of their kin, but I’m of their kin and this is (he

showed Igor) the son of Riurik’); here it is linked to the particular

importance of Kiev.

32

Riurik’s successor, Oleg, called Veshii or the Wise, is one of the most

mysterious figures in the RPC. We can divide his career, as it was depicted

by the chronicler, into three periods. First, in 882–885 Oleg conquered

Smolensk, Liubech and Kiev, and imposed tribute on some Slavonic

tribes (Derevlians, Severians and Radimichi) around the Upper and

Middle Dnieper. Second, in 907 he attacked Constantinople and in 911

concluded a treaty with the Byzantine emperors, Leo VI and Alexander.

Finally, in 912, he died. To understand the traditions surrounding Oleg it

is necessary to look at the role of oral transmission, and folklore parallels.

Franklin and Shepard argue that ‘local legend told of how Prince Oleg had

died in accordance with a pagan prophecy’.

33

The basis for this claim is the

story that a ‘sorcerer’ (P\YcP) predicted that Oleg would die due to his

favourite horse. Oleg ordered that the horse be kept but never led to him.

Many years later, after the war with the Greeks, he visited the horse’s

corpse and put his foot upon its forehead (Y\O), from which slithered out

30

=?>9

, I, 23 (text): ‘<YSQ

_ ]\c\^\[V P\V Ph Y\Rjmc, N R^aQVm [NUNRV \_‘NPV _ 6 ]^V_YN

X\ ._X\YRa V 2V^\PV

, QYNQ\Ym, mX\ Q\_‘j S_Zj V VRSZh Ph 1^SXV \‘ <YQN V \‘ 6Q\^m

X[mTVeN

, RN ]^VRS‘N X [NZ X ^\R\Zh _P\VZh. ._X\YRh TS V 2V^h ]^VR\_‘N. 6 Pi_XNXNP

TS P_V ]^\eVV VUh Y\Rjm

, V ^SeS <YSQh ._X\YRa V 2V^\PV: ‘‘0i [S_‘N X[mUV [V ^\RN

X[mTN

, [\ NUh S_Zj ^\Ra X[mTN (V Pi[S_\fN 6Q\^m) V _S S_‘j _i[h >l^VX\Ph’’. 6 aOVfN

._X\YRN V 2V^N

_ 6 _SRS <YSQh X[mTN P 8VSPS.’

31

=?>9

, I, 23 (text).

32

=?>9

, I, 55–60 (text): ‘0i [S_‘N X[mUV [V ^\RN X[mTN, [\ NUh S_Zj ^\Ra X[mTN (V

Pi[S_\fN 6Q\^m

) V _S S_‘j _i[h >l^VX\Ph.’

33

Franklin and Shepard, The Emergence of Rus, p. 318.

62

Alexandr Rukavishnikov

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

a snake that bit Oleg on the foot. From this Oleg fell ill and died.

34

We

have a close parallel to this in an Icelandic saga about Orvar/Oddr.

According to the saga, a sorcerer predicted that Orvar/Oddr would die on

account of a snake, which would slither from the skull of his horse, named

Faksi. Oddr killed Faksi, and after many years, and following various

voyages and exploits in distant lands, he returned to places where he had

lived in his youth, being sure that the prophecy would never come true.

Orvar/Oddr tripped on Faksi’s skull and hit it with his spear; a serpent

slithered out and bit him, causing his death.

35

We have several close

parallels between Oleg’s and Orvar/Oddr’s stories, for both were Vikings

and both travelled and struggled in distant lands. According to another

version of Oleg’s legend (‘others are saying’), he ‘went beyond the sea [i.e.

to Scandinavia] and a snake bit his leg, and he died from this’.

36

This

might indicate that both stories were based on the same legend. But

Rydzevskaia wisely reminds us that ‘a legend of a hero’s death by an

animal

_ is so widespread among different peoples and countries, that we

may suppose an independent existence of the Scandinavian and the

Russian versions’. We know of the Serbian fairy tale about a Sultan and

his horse; Danish stories that replace the horse with a dragon; and similar

German legends.

37

In an English version a female sorcerer predicted that a

knight would meet his death by his horse. The knight ordered the poor

animal to be killed. However, after returning from the Crusades he visited

the horse’s corpse, hurt his foot on a bone, and died.

38

Rather than seeing a

genealogical link tying all these stories back to a common ancestor, it is

perhaps more helpful to think of parallel local oral traditions rooted in

folklore. This material shapes the chronicler’s account of Oleg.

The role of local traditions is further suggested by a common feature

shared by the stories about the deaths of Askold and Dir, Oleg, and also

Igor, all of which identify the location of their graves in the present. About

Oleg’s grave the RPC states: ‘And all the people cried and carried him and

buried him on the hill, Shekovitza, where is his grave, called the grave of

Oleg, to the present day.’

39

Similarly, of Igor it relates: ‘And Igor was

buried, and there is his grave near the town of Iskorosten’ in the

Derevlians land to the present day.’

40

This formulation expresses a

34

=?>9

, I, 38–9 (text).

35

From 3... >iRUSP_XNm, ‘8 P\]^\_a \O a_‘[ic ]^SRN[Vmc P _\_‘NPS R^SP[SWfSW ^a__X\W

YS‘\]V_V

’, in 3... >iRUSP_XNm, 2^SP[mm >a_j V ?XN[RV[NPVm P IX–XIV PP. (Moscow,

1978), pp. 159–236, at p. 186.

36

=?>9

, III, 109 (text): ‘VRagl SZa UN Z\^S, V aXYl[a UZVN P [\Qa, V _ ‘\Q\ aZ^S’.

37

>iRUSP_XNm

, ‘8 P\]^\_a \O a_‘[ic ]^SRN[Vmc’, pp. 186, 187, 189; 8.B. @VN[RS^, =\SURXV

_XN[RV[NP\P P /SY\S Z\^S

(Saint Petersburg, 1906), pp. 235–45.

38

A. Taylor, ‘The Death of Orvar–Oddr’, Modern Philology 19 (1921), pp. 93–106, at p. 93.

39

=?>9

, I, 39 (text): ‘6 ]YNXNfN_m YlRS P_V ]YNeSZ PSYVXVZ, V [S_\fN, V ]\Q^SO\fN SQ\

[N Q\^S

, STS QYNQ\YV‘_m SX\PVdN, SQ\ TS Z\QVYN V R\ _SQ\ R[V _Y\PS‘j Z\QiYN <YjQ\PN’.

40

=?>9

, I, 55 (text): ‘V ]\Q^SOS[h Oi_‘j 6Q\^j, V S_‘j Z\QVYN SQ\ a 6_X\^\_‘S[m Q^NRN P

2S^SPSch V R\ _SQ\ R[S

’.

The Russian Primary Chronicle as a family chronicle

63

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

concern in the chronicle to remember and honour these sites of memory.

We do not know if Oleg and Igor were indeed buried in the places

mentioned in the RPC (for example, the Commission and Academic

copies tell us that Oleg’s grave ‘is in Ladoga’, in the north of Rus’

41

), but

for the author it was important to specify the exact position, and indeed

the alternative traditions in the Commission and Academic copies suggest

the significance of this information.

42

Twelfth-century Russian cities

sought to connect their memory with the princely family, as a means of

bolstering their current status. Pskov claimed that Princess Olga was born

there, and the author of the RPC confirms that her sledge was still in Pskov

at the beginning of the twelfth century (_‘\m‘ P\ =_X\PS).

43

We thus

need to emphasize the significance of topography to the RPC as a family

chronicle: it was very important to describe the circumstances of the death

of a contemporary ruler’s ancestors, and to attach to exact spots memories

about their graves or places of demise. It is very difficult to say what the

immediate political value was of such a tradition of commemoration of

the burial places of ancestors; but within the dynasty the honouring and

remembrance of progenitors served as a tool to unite the numerous

Riurikids. Representatives of two rival lines, Vladimir Monomakh and

the princes of Chernigov (David and Oleg Sviatoslavichi), took part

in the transmission of St Boris’s and St Gleb’s relics (the sons of St

Vladimir) to the new church in Vyshegorod in 1115.

44

Although we can detect oral tradition underpinning the account of

Oleg, he also plays a significant role in the RPC ’s plot: the organizing of

Rus’ into a state focused on Kiev, and the masterminding of the first

successful attack on Byzantium. He gained power over southern Rus’: the

waterway along the Dnieper to the Black Sea was secured, and several

Slavonic tribes (the Derevlians, Severians, Radimichi and Polianians)

were in his hands. The chronicler tells us that Oleg prophesied that Kiev

would be a ‘mother of Russian cities’ (Metropolis), in a clear allusion to the

contemporary situation. After conquering Kiev, an important step for

Oleg was the foundation of cities and the imposition of a fixed tribute on

northern (the Slovene, Krivichi and Meria) and southern Rus’ tribes. Here

41

=?>9

, III, 109 (text): ‘S_‘j Z\QiYN SQ\ P 9NR\US’.

42

See also 0.M. =S‘^acV[, ‘8 R\c^V_‘VN[_XVZ V_‘\XNZ R^SP[S^a__X\Q\ X[mTS_X\Q\

XaYj‘N

’,

POLYTPOPON (Moscow, 1998), pp. 881–9, at p. 883; van Houts, Memory and

Gender, p. 94: ‘The object on which memorial tradition was most immediately focused was the

body of a dead person. Once buried, the burial place and tomb became the centre for the family

tradition of mourning and commemoration.’

43

=?>9

, I, 55 (text). Similarly, the bones of the pagan princes Iaropolk and Oleg, sons of

Sviatoslav, grandsons of Igor, were excavated, christianized and buried in the church of the

Mother of God (‘Tithe church’) in Kiev (1044 in the RPC, seventy years after their death!), see

=?>9

, I, 155 (text). Dudo mentioned the place of the battle between William Longsword and his

rebellious vassals: ‘And the place where the wonderful battle was fought is called ‘‘At the Field of

Battle’’ to the present day’ (Dudo, History, p. 68).

44

=?>9

, II, 280, 281 (text).

64

Alexandr Rukavishnikov

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

a clear pattern thus begins to emerge. Firstly, Riurik founded the state and

was the progenitor of the dynasty. Then Oleg united northern Novgorod

and southern Kiev, imposed the first taxes, and organized the new state.

Another of Oleg’s very significant functions was that of being Igor’s

mentor (fostri, kormilets): ‘Igor grew up and followed Oleg and obeyed

him. And [Oleg] brought him a wife from Pskov named Olga.’

45

Oleg and

Olga have the same name (Old Norse Helgi and Helga – the ‘saint’),

which, like the names of Riurik and Igor, seems to be princely in both

Russian and Scandinavian traditions.

46

War with the Greeks was the last of

Oleg’s achievements. The chronicler states that in 907 the Russian leader

attacked Byzantium: he destroyed everything around Constantinople

(palaces and churches), took a large number of captives and killed all of

them, gained a great tribute from the Greek emperors, and concluded a

peace treaty with them.

47

In 911 Oleg and the Greek emperors concluded

another treaty, also recorded in the chronicle. Textual analysis shows that

the wording of the treaty of 907 is based on the later treaty of 911. The

Greek text of the 911 document was translated into Russian in the eleventh

century, or even in the first half of the twelfth century, and then inserted

into the chronicle.

48

There is nothing about the Russian attack of 907 in

the Greek sources at all, and it looks as though the treaty of 907 was

constructed by the chronicler using the text of the later source.

Having observed certain principles in the narrative it becomes clear

that the activities of Oleg, Igor and Olga all share the same framework.

49

In tabular form this can be set out as follows in Table 2. Of course,

Olga’s death as a Christian was commemorated in a different manner

than those of the pagans Oleg and Igor. However, we can clearly see the

chronicler using their careers to discuss the same themes, and drawing on

a similar mixture of translated Greek sources and topographical tradi-

tions to do so.

The treaty of 944 and the aims of the chronicler’s work

It is worth comparing the chronicler’s depiction of the structure of

the early Russian polity, with its stress on Riurikid legitimacy and the

centrality of Kiev, with alternative testimonies. One of the few genuine

45

=?>9

, I, 29 (text): ‘6Q\^SPV TS PhU^N_‘Nfl, V c\TNfS ]\ <YUS, V _YafN SQ\. 6

]^VPSR\fN SZa TS[a \‘ =j_X\PN VZS[SZh <YQa

’.

46

=S‘^acV[

, ‘8 R\c^V_‘VN[_XVZ V_‘\XNZ’, p. 886: ‘The names of the first Russian princes –

Riurik (Hro¨rekr), Oleg (Helgi), Igor (Ingvar – is an anthroponym with the name Ingvi-Frair) –

seemed to be princely both in Russian and Scandinavian tradition.’

47

=?>9

, I, 29–31 (text).

48

See M. :NYV[QaRV, ‘>a__X\-PVUN[‘VW_XVS _PmUV P X PSXS _ ‘\eXV U^S[Vm RV]Y\ZN‘VXV’,

0VUN[‘VW_XVW P^SZS[[VX

1995 Q. 56 (81) (1996), pp. 68-91; 0VUN[‘VW_XVW P^SZS[[VX 1997

Q

. 57 (82) (1997), pp. 58–87.

49

=?>9

, I, 22, 32, 38, 42, 46, 54–5, 59–61, 67–9 (text).

The Russian Primary Chronicle as a family chronicle

65

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

tenth-century documents inserted into the RPC is a peace treaty between

Rus’ and Byzantium concluded in 944. It includes a list of the ambas-

sadors in Constantinople who took an integral part in the treaty’s

negotiation. What are the differences between this list and other parts

of the chronicle’s text? And what might these differences tell us about the

aims of the chronicler’s work?

The treaty of 944 is preserved in the chronicle in its entirety. It is an

original charter, presumably, kept in the prince’s archive in Kiev, which

was translated from Greek into Russian, and interpolated into the RPC. It

is not known if it was translated and simultaneously inserted in the

chronicle, or whether there was a more complex multi-stage process. The

lexicon of the treaty, as it is now in the RPC, contains words and terms that

appeared in Russian chronicles and ecclesiastical texts rather late. For

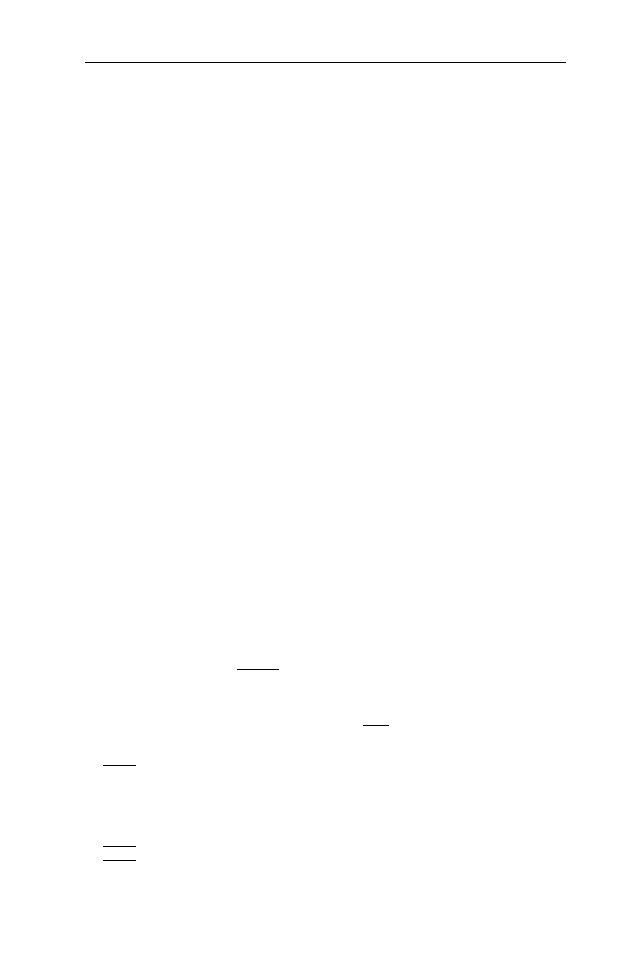

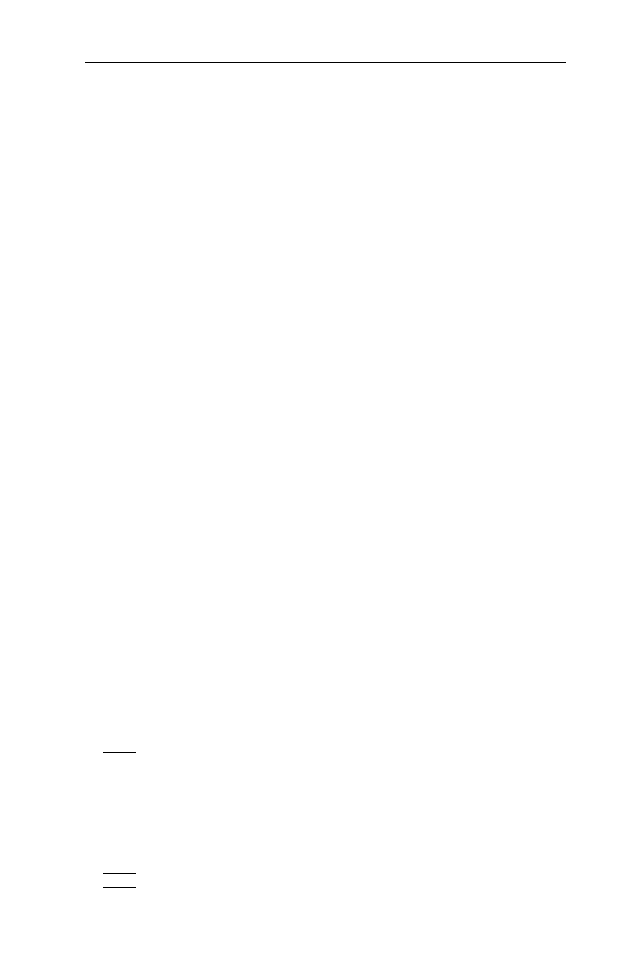

Table 2. Careers of Oleg, Igor and Olga

Oleg

Igor

Olga

1. 879: Obtaining power

after Riurik’s death.

2. 882–885: State

building (conquering of

Smolensk, Liubech,

Kiev; imposing tribute

on Slavonic tribes).

3. 907: ‘Oleg went to

the Greeks’. Successful

war and return home:

‘and came Oleg to Kiev

taking gold and silks,

and vegetables, and

wines

_’.

4. 911: Peace treaty with

the Greeks.

5. 912: The story of his

death. Starts with: ‘And

Oleg was ruling in Kiev

having obtained peace

with all countries and

autumn came

_’.

1. 913: Obtaining power

after Oleg’s death.

2. 914: State building

(‘Igor went to the

Derevlians and won a

victory over them and

imposed a tribute

greater than Oleg’s’).

3. 941: ‘Igor went to the

Greeks’. Unsuccessful

war, but then (944) a

successful one: ‘[Igor]

took from the Greeks

gold and silks for all of

his warriors and

returned back to Kiev.’

4. 944: Peace treaty with

the Greeks.

5. 944: The story of his

death. Starts with: ‘Igor

started to rule in Kiev

having obtained peace

with all countries and

autumn came

_’.

1. 945: Obtaining power

as a regent after Igor’s

death (Olga’s son

Sviatoslav was too

young to rule).

2. 946–947: State

building (imposition of

a new system of taxation

over the Derevlians and

Slovene).

3. 955: ‘Olga went to the

Greeks’. She was

baptised and then

received from the

emperor ‘gold and

silver, silks and different

pottery

_’.

4. - - - - - - - -

5. 969: Death of Olga.

Praise in Christian

manner for all of her

virtues.

66

Alexandr Rukavishnikov

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

example, the term ‘grand prince’ (PSYVXVW X[mUj) appeared from the

mid-twelfth century.

50

So it looks as if the treaty was translated relatively

late, and perhaps immediately inserted into the RPC. There have also been

some speculations that the compiler who added the treaty to the chronicle

might have changed or added some details, such as the names of cities.

51

The list of ambassadors contained within the treaty gives an invaluable

snapshot of the Russian polity in the middle of the tenth century, which

contrasts significantly with that portrayed in the chronicle text; for this

reason alone it is improbable that it has been subject to wholesale

tampering. It names twenty-four individuals, and then indicates the

person who was responsible for sending each individual ambassador to

Byzantium. The list runs as follows:

Ivor ambassador of Igor, great prince of Rus’

Vuefast of Sviatoslav, son of Igor

Iskusevi of princess Olga

Sludi of Igor, nephew (net’ ) of Igor

Uleb of Vladislav

Kanizar of Predslava

Shikhbern of Sfandr, wife of Uleb

Prasten of Turdr

Libiar of Fast

Grim of Sfirk

Prasten of Iakun (Hakon), nephew (net’) of Igor

Kari of Tudok

Karshev of Turdr

Egri of Evlisk

Voist of Voik

Istr of Amind

Prasten of Bern

Iatviag of Gunnor

Shibrid of Aldan

Kol of Klek

Steggi of Eton

Alvad of Gud

Frudi of Tuad

Mutr of Outin.

52

We can not be sure that the chronicler used the proper spellings of all

the names in the list as the translation from the original Greek might not

always have been correct, and few of these individuals appear otherwise in

50

:NYV[QaRV

, ‘>a__X\-PVUN[‘VW_XVS _PmUV’, p. 87.

51

Franklin and Shepard, The Emergence of Rus, pp. 107, 117, 118.

52

=?>9

, I, 46–7 (text).

The Russian Primary Chronicle as a family chronicle

67

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

the chronicle. The first three names in the list are well known to us: Igor,

prince of Kiev; his son, Sviatoslav; and Igor’s wife, Olga. That Olga’s

name is in third position is very significant, for all Igor’s male relatives

(his nephews) are below her. Igor’s nephew, Igor, is in fourth place.

It is interesting to note that he bore the same name as his uncle, for

there were no Riurikovichi with the same name in the following three

generations. The next Igor – the youngest son of the Kievan prince

Iaroslav – died in 1060. Another nephew – Iakun – is only eleventh in

the list, and we do not know why. Iakun is a Slavonic spelling of a

Scandinavian name, Hakon. It is significant that such a name was never

used by Riurikovichi, but it is well known as a name of noblemen in

twelfth-century Rus’. (Iakun, a nobleman from Smolensk, is mentioned

in the Ipatian Chronicle in 1159; Iakun, son of Miliata, a Kievan noble-

man, is mentioned in the same chronicle in 1162;

53

and there are several

noblemen with the name Iakun in Novgorodian chronicles from the

twelfth century.) It is highly possible that the first Igor’s nephew (Igor) was

a son of the Kievan prince’s brother, who bore a royal name; Iakun

(Hakon) is a Scandinavian noble name (even a king’s name), and his name

and relatively low position might be explained if his kinship with Igor

came through the maternal rather than the paternal line.

54

The next pair –

Vladislav and Predslava (fifth and sixth on the list) – seems to be a couple,

for they both bear Slavonic names frequently mentioned in Russian

medieval sources. However, there is one very important difference:

Vladislav is a noble (boyar) name (a nobleman Vladislav is mentioned

by the Ipatian Chronicle in 1172

55

and there are many other examples for

the same period); Predslava is a name frequently used by the Riurikid

family. For example, Predslava, the daughter of St Vladimir, is mentioned

in the RPC in 1016; she played a prominent role in the dynastic dispute

that followed Prince Vladimir’s death.

56

Several daughters of Russian

princes of the late eleventh to the early thirteenth centuries also bore this

name. There are no indications that boyars or other nobles of that time

called their daughters Predslava. We may only suppose that Predslava was

a sister or a daughter of Igor, but there is no direct evidence of this.

Seventh on the list is Sfandr ‘wife of Uleb’. An Uleb was mentioned as an

53

=?>9

, II, 503, 518 (text).

54

E. Searle, Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840–1066 (Berkeley, Los Angeles

and London, 1988), pp. 160–1; D.A. Bullough, ‘Early Mediaeval Social Groupings: The

Terminology of Kinship’, Past and Present 45 (1969), pp. 3–18, at pp. 13–14: ‘

_ it is clear that

kinship was non-unilineal or bilateral: that is to say, every individual had in general the option of

tracing relationships to other individuals through either parent and operative relationships

(those involving rights and obligations) were created among the consanguines on both sides,

although consanguineal relationships on the father’s side tended to have greater advantages and

disadvantages.’

55

=?>9

, II, 557 (text).

56

=?>9

, I, 135, 140 (text).

68

Alexandr Rukavishnikov

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

ambassador of Vladislav (fifth on the list). It is highly possible that Sfandr

was thus his spouse, for it would have been senseless to use the phrase ‘wife

of Uleb’ without elsewhere having included him. It is odd that Sfandr sent

her own ambassador, while her husband, Uleb, was himself one. It might

be there was a mistake in the translation from the Greek, but another

reason may be that Sfandr’s role in Rus’ society was much more important

than her husband’s. There is another Uleb in the list of Russian merchants

who were also involved in the negotiations in Constantinople. Of course,

Sfandr was not the wife of the merchant Uleb, but we can see from this

how popular the name ‘Uleb’ was in tenth-century Rus’. There are other

examples of this name in early Russian chronicles: one Uleb was a posadnik

(mayor) of Novgorod in the late eleventh century;

57

another was a Kievan

tysiatskii, mentioned by the Ipatian Chronicle in 1146 and 1147.

58

By

contrast, there is no name ‘Sfandr’ in the Russian chronicles at all. We thus

have strong indications in the treaty’s text of women playing an important

role in Rus’ society of the tenth century. Indeed, in this list of the most

prominent and powerful, of the first seven mentioned, three are women.

But what of the questions posed earlier concerning the textual

differences within the chronicle, and the aims of the RPC ’s author?

Firstly, are there any dissimilarities between the body of the RPC and the

text of treaty? Close scrutiny reveals several striking differences. First of all,

only Igor, Sviatoslav and Olga appear in the chronicle; while both

nephews, Vladislav, Predslava, Uleb, Sfandr and all the others in the

ambassadorial list were mentioned only in the document of 944. There are

other characters whose role in the RPC might be expected to warrant a

mention in the treaty, but who are conspicuous by their absence. For

example, Svenald, senior voevoda (military commander) of Igor and then

of Sviatoslav, is mentioned by the RPC in 945 and 946, whilst Asmund,

mentor of Sviatoslav, appears in 946.

59

These two do not, however, appear

in the treaty, which is a striking anomaly. Secondly, the one and only

document of 944 tells us much more about Igor’s family, and particularly

about collateral kin, than the whole of the RPC. It might be that the

chronicler possessed no information about Igor’s nephews and other

relatives; however, it is more probable that this information was deliber-

ately suppressed in order to reinforce the idea of Vladimir’s descendants

possessing exclusive rights of power over Rus’. We might compare this

with Searle’s observations on ‘nonrecognition of kin’ as ‘the most

important fiction’ in Dudo of St-Quentin’s account of the Norman

ducal house: ‘The suppression of the memory of any but a single child in

Dudo’s myth can be interpreted as a political act to maintain the unique

57

=?>9

, III, 164 (text).

58

=?>9

, II, 324–6, 344–5 (text).

59

=?>9

, I, 54–5 (text).

The Russian Primary Chronicle as a family chronicle

69

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

legitimacy of Richard.’

60

This nonrecognition of kin is a very important

feature whereby family memory can be reworked to fit the agenda of the

present, and the RPC gives several fine examples. Askold and Dir were not

of Oleg and Igor’s kin and they were murdered. We do not know about

their children or relatives. Riurik had only one child – Igor. The only child

of Igor was Sviatoslav. He had three sons – Iaropolk, Oleg and Vladimir.

The first two had no children, so only the sons and daughters of

Vladimir, the first Christian ruler of Rus’, appear in the chronicle. It is

obvious now that one of the main objects of the author was to show that

the RPC is the chronicle of the descendants of St Vladimir – the Christian

princely descendants – and there is no space for their kinsmen. We have a

straight line of power transmission from Riurik to Vladimir. In other

words, the chronicler’s prime political idea was to substantiate the rights

of only the Vladimirikids to absolute power over Rus’. In the treaty, we see

an ethnically mixed society, with women enjoying high political status,

and a wide range of collateral kinship links with the ruling dynasty

creating claims to power and tying together an extensive and apparently

decentralized polity. In the chronicle, we are provided with a linear

narrative of descent in one lineage, from which all current Russian rulers

claimed their origins: the descendants of Riurik, and of Vladimir, the first

Christian ruler of Rus’.

Vladimir: family memory and political legitimacy

We can trace the various techniques so far identified – the manipulation of

diverse traditions to legitimate the present political system – in the RPC ’s

telling of the story of Vladimir. According to the RPC, Sviatoslav had

three sons – Iaropolk, Oleg and Vladimir. It is very significant that we do

not know the name of the mother (or mothers) of the first two. We may

only suggest that she was certainly of a higher rank than Vladimir’s

mother, Malusha. Malusha was Olga’s housekeeper (XYle[VdN) and

slave, for Vladimir was called ‘slave’s son’ (^\OVeVe) by the Polotskian

princess, Rogneda.

61

If the pagan Sviatoslav contracted many other

marriages during his short but turbulent life, the chronicler names only

Malusha. Also we find out from the RPC that Malusha’s father was Malk

of Liubech and her brother was Dobrynia.

62

Dobrynia’s role in the RPC is

an important one: he was Vladimir’s mentor and played an active role in

his nephew’s struggle for the Kievan throne. Thus we know about

Vladimir’s paternal, and maternal lineage. All the Russian princes of

60

E. Searle, Predatory Kinship, p. 93.

61

=?>9

, I, 69, 76 (text).

62

=?>9

, I, 69 (text).

70

Alexandr Rukavishnikov

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries were descendants of Vladimir:

the RPC is their family story, the story of the Vladimirikids (grandsons

and great-grandsons of St Vladimir). It was thus essential to preserve and

present Vladimir’s genealogy, including both his Scandinavian fore-

fathers and Slavic ancestors. We may suppose that for the chronicler it

was important to underline Vladimir’s mixed origin, as his descendants,

remembering their Scandinavian roots, were ruling Slavic lands. The

Novgorodians (people from northern Rus’) asked Sviatoslav to send

Vladimir to govern them, the same as they had invited Riurik and his

brothers to come a century before. For the twelfth-century Riurikids it

was necessary to explain their rights to govern in Novgorod, as well as the

roots of the Novgorodian tradition of inviting princes to rule.

After Olga’s death (969) Sviatoslav divided his territories into three:

Iaropolk got Kiev, Oleg was given the Derevlians’ land; and Vladimir

went to Novgorod. This division of Rus’ lands before Sviatoslav’s death is

another of the chronicler’s interesting textual strategies. The chronicler

felt it necessary to point out that this division occurred in 970, two years

before Sviatoslav’s murder, in order that power was seen to have been

transmitted successfully to his inheritors, his three sons. As mentioned

above, after Igor’s death the prince of the Derevlians, Mal, claimed the

Kievan throne, which precipitated a purely Riurikid family dispute. No

strangers, no other noblemen, no other kinsmen took part, only Sviato-

slav’s three sons. The war between the brothers began as follows. Oleg and

Liut, the son of the senior commander Svenald, were hunting in the same

forest. It seems that Oleg, acting like the possessor of absolute power,

killed Liut for trespassing on Oleg’s prerogative. This, of course, is the

view of affairs as seen from the twelfth century, but for the chronicler it is

more than likely that princes of the tenth century possessed the same

qualities as the princes contemporary to him. Svenald, Liut’s father (at this

time Iaropolk’s chief commander), persuaded his leader to attack Oleg.

Iaropolk won the battle near the Derevlian town of Vruchii. The story

continues:

Oleg ran with his warriors into Vruchii. There was a bridge over the

ditch leading to the town gates, and there was a crush on the bridge.

People were stuffing each other into the ditch and Oleg was pushed

from the bridge with many other strangled men and their horses.

And Iaropolk came into Oleg’s town, taking his power, and com-

manded that Oleg be found

_ And one Derevlian told how he had

seen Oleg pushed from the bridge. And Iaropolk sent to search for his

brother. And they were taking corpses out of the ditch from the

morning to the afternoon, and they found Oleg amidst the corpses, and

carried him and put him on a carpet. And Iaropolk came and cried over

The Russian Primary Chronicle as a family chronicle

71

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

him

_ And buried him in the place near Vruchii, and there is his grave

to the present day. And Iaropolk took his power.

63

Once again we come across two main features of the family chronicle: the

transmission of power from one prince-Riurikovich to another, and a

vivid description of Oleg’s death that points out the exact place of his

grave. Though Oleg’s bones were taken in 1044 and buried in Kiev, his

original burial place was still of prime significance in the chronicler’s own

time.

This was the beginning and not the end of the war. Vladimir learned

that Oleg had been killed, and retreated to Scandinavia. So Iaropolk sent

his men to Novgorod and became an autocrat of Rus’.

64

Two years later

(980) – as discussed above, the chronology of the RPC is artificial – Prince

Vladimir returned to Novgorod with the Varangians and sent Iaropolk’s

men back to their master. The last act in the drama of Sviatoslav’s sons was

the conquering of Kiev by Vladimir, and Iaropolk’s murder.

65

The son of

Malusha became the autocrat of Rus’. However, before the decisive fight

with Iaropolk, Vladimir had won another ‘battle’: the story inserted in the

chronicle of his ‘matchmaking’ with Rogneda. We see here another

striking piece rich with parallels from several traditions and rooted in

folklore. Vladimir proposed marriage to the daughter of the ruler of

Polotsk. She refused as he was ‘a son of the slave’, and so the angry

Vladimir conquered Polotsk, killed Rogneda’s parents and brothers, and

married her anyway.

66

We have some close parallels to this in Scandina-

vian sources: the stories of Asa in the Ynglinga saga; and of Gudrun, the

daughter of Iarnsneggi, in the saga about Olav Trygvasson in Heimskrin-

gla.

67

Reading this account there are several questions that naturally arise.

First of all, why have such a narrative in the chronicle? Rogneda (Old

Norse Ragnheithr) was the mother of Iaroslav and Iziaslav, Vladimir’s

sons, whose descendants were Russian princes of the late eleventh and

early twelfth centuries. Again, as in Malusha’s case, it was essential for the

author to show Rogneda’s origin and her ancestors. Her father, Rogvolod

63

=?>9

, I, 74–5 (text): ‘=\OSQfl TS <YjQa _ P\V _P\VZV Ph Q^NRh ^SX\ZiV 0^aeVV. /mfS

eS^S_j Q^\OYl Z\_‘h X\ P^N‘\Zh Q^NR[iZh

. @S_[meS_m R^aQh R^aQN, ]VcNca Ph Q^\OYl,

V _]Sc[afN <YjQN _ Z\_‘a P RSO^j

, ]NRNca YlRjS Z[\UV, V aRNPVfN X\[V eSY\PSdV. 6

PhfSRh M^\]\YXh Ph Q^NRh <YjQ\Ph

, ]S^Sm PYN_‘j SQ\, V ]\_YN V_XN‘j O^N‘N _P\SQ\

_ 6

^SeS SRV[h 2S^SPYm[V[h

: ‘‘.Uh PVRSch, mX\ PeS^N _]Sc[afN _ Z\_‘a’’. 6 ]\_YN M^\]\YX

V_XN‘j O^N‘N

, V PYNeVfN ‘^a]jS VUh Q^\OYV \‘ a‘^N V R\ ]\YaR[S, V [NYSU\fN <YjQN

Pi_]\RV ‘^a]jm

, [S_\fN V, V ]\Y\TVfN V [N X\P^S. 6 ]^VRS M^\]\YXh [NRh [SZh

]YNXN_m

_ 6 ]\Q^SO\fN <YjQN [N ZS_‘S a Q\^\RN 0^aeSQ\, V S_‘j Z\QVYN SQ\ V R\ _SQ\

R[S

_ 6 ]^Vm PYN_‘j SQ\ M^\]\YXh.’

64

=?>9

, I, 75 (text).

65

=?>9

, I, 76–8 (text).

66

=?>9

, I, 75–6 (text).

67

@

.;. 2TNX_\[, 6_YN[R_XVS X\^\YSP_XVS _NQV \ 0\_‘\e[\W 3P^\]S (_ R^SP[SWfVc

P^SZS[ R\

1000 Q.): @SX_‘i, ]S^SP\Ri, X\ZZS[‘N^VW (Moscow, 1993).

72

Alexandr Rukavishnikov

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

(Old Norse Ragnvaldr), was the ruler of Polotsk, a Scandinavian. It was

surprising enough to find Polotsk as Rogvolod’s city because we know that

it had been given by Riurik to ‘his own man’ a century before; here the

details of the RPC ’s account perhaps shed dubious light on its claims of

Riurikid autocracy. Another important detail that the chronicler stressed

was that Vladimir killed ‘Rogvolod and his two sons’: that is, Rogneda’s

male relatives. Polotsk was united with Kievan Rus’, and Vladimir and

Rogneda’s descendants governed there. But it remains very significant that

the chronicler emphasized the murder of Rogneda’s male relatives. In

other words, no one had the right to pretend to the Riurikovichi’s power

over all Rus’, and no alternative lines or alternative claims even to

individual cities were to be acknowledged.

Conclusion

Rereading the RPC as a literary work that took its final shape in the 1110’s,

composed by the hegumen, Silvestr of Vydubichi, and commissioned by

the Kievan prince, Vladimir Monomakh, gives a new dimension to the

study of early Russian history. We can observe how the political situation

at the beginning of the twelfth century influenced the work of the

chronicler. The Russian lands were the sole possession of the Riurikids:

the members of the clan had absolute power over this territory on the very

edge of Christendom. As his brothers died, this power was given by the

Slavic and the Finno-Ugrian tribes to the progenitor of the dynasty,

Riurik, and was transmitted to his only son, Igor. All pretenders to this

power were murdered (as were Askold and Dir), or ‘disappeared’ (as did

Mal). Local ruling families were destroyed (like Rogvold and his sons) and

their possessions were absorbed into the lands of the Riurikids (as was

Polotsk). Kiev, the centre of Vladimir Monomakh’s territories in the mid-

1110’s, was proclaimed the capital (Metropolis) of all Russian lands by Oleg

Veshii, and was at the centre of all family disputes after that. Thus we can

see how the contemporary concerns of the beginning of the twelfth

century were projected onto the past; and the rights of the Riurikids to

absolute power over Rus’, and the central importance of Kiev, were

substantiated by the RPC.

We can also see how the chronicler elaborately used oral memories. The

investigation of the careers of Oleg, Igor and Olga shows that they have

much in common, suggesting that oral memories were flexible and could

be adapted to fit into the narrative. We cannot actually be sure that Riurik,

Oleg and Igor were even relatives, as more than 150 years separates their

time from the chronicler’s own. Their stories might or might not be

substantially corrupted, and we will never know to what degree. Oral

‘memories’ might even be the author’s own invention, and such visible

The Russian Primary Chronicle as a family chronicle

73

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

signs as the princes’ graves or bones might be a ‘fiction’ as well. However,

the role of these stories in shaping family memory (in our case that of the

Riurikids), and cohering kin into a single unit, was a very important one –

especially for a family as large as were the Riurikids at the beginning of the

twelfth century.

Finally, the recognition and nonrecognition of kin is central to the

creation of family memory. This is connected with the transmission of

power and the substantiation of the Riurikids’ sole rights to be absolute

rulers. A vivid example is the story of Riurik’s kinsman, Oleg, and the

Kievan rulers, Askold and Dir. Oleg killed both because they were not of

Riurik’s kin. The chronicler in the body of the RPC did not list all of Igor’s

relatives mentioned in the treaty of 944. They were omitted from the

narrative because only descendants of St Vladimir had come to rule in

eleventh- and twelfth-century Rus’. Thus we have a select number of

Riurikids in the history. All others fell into oblivion. Oral and family

memory are selective, and so too was the author of the RPC.

Moscow Lomonosov State University

74

Alexandr Rukavishnikov

Early Medieval Europe 2003

12 (1)

# Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

22 The climate of Polish Lands as viewed by chroniclers, writers and scientists

Fish The Path Of Empire, A Chronicle of the United States as a World Power

Alexander Motyl Putin s Russia as fascist system

Drobilka Family 2 Russian s Intense Love Leona Lee

Drobilka Family 1 Russian s Innocent Love Leona Lee

Chekov Billionaire s 6 Russian Billionaire s Family Leona Lee

Chronic Hepatitis

PREZENTacja dla as

3 1 Krzywa podazy AS ppt

Jacobsson G A Rare Variant of the Name of Smolensk in Old Russian 1964

PGUE AS

opracowanie cinema paradiso As dur

[Papermodels@emule] [Maly Modelarz 1960 11] Russian PO 2

family spaghetti

Family 2

Levy J Grand Russian Fantasie

as spr 5 id 69978 Nieznany (2)

AON as id 66723 Nieznany (2)

więcej podobnych podstron