Harvard Business Review Online | What Venture Trends Can Tell You

Click here to visit:

What Venture Trends Can Tell You

The venture capital industry is in for a shakeout—and smart

outsiders are watching.

by William F. Meehan III, Ron Lemmens, and Matthew R. Cohler

William F. Meehan III is a director in McKinsey & Company’s San Francisco office; Ron Lemmens, an alumnus of that office, is a

senior vice president at GE Consumer Finance in Stamford, Connecticut; Matthew R. Cohler is a consultant in McKinsey’s Silicon

Valley office.

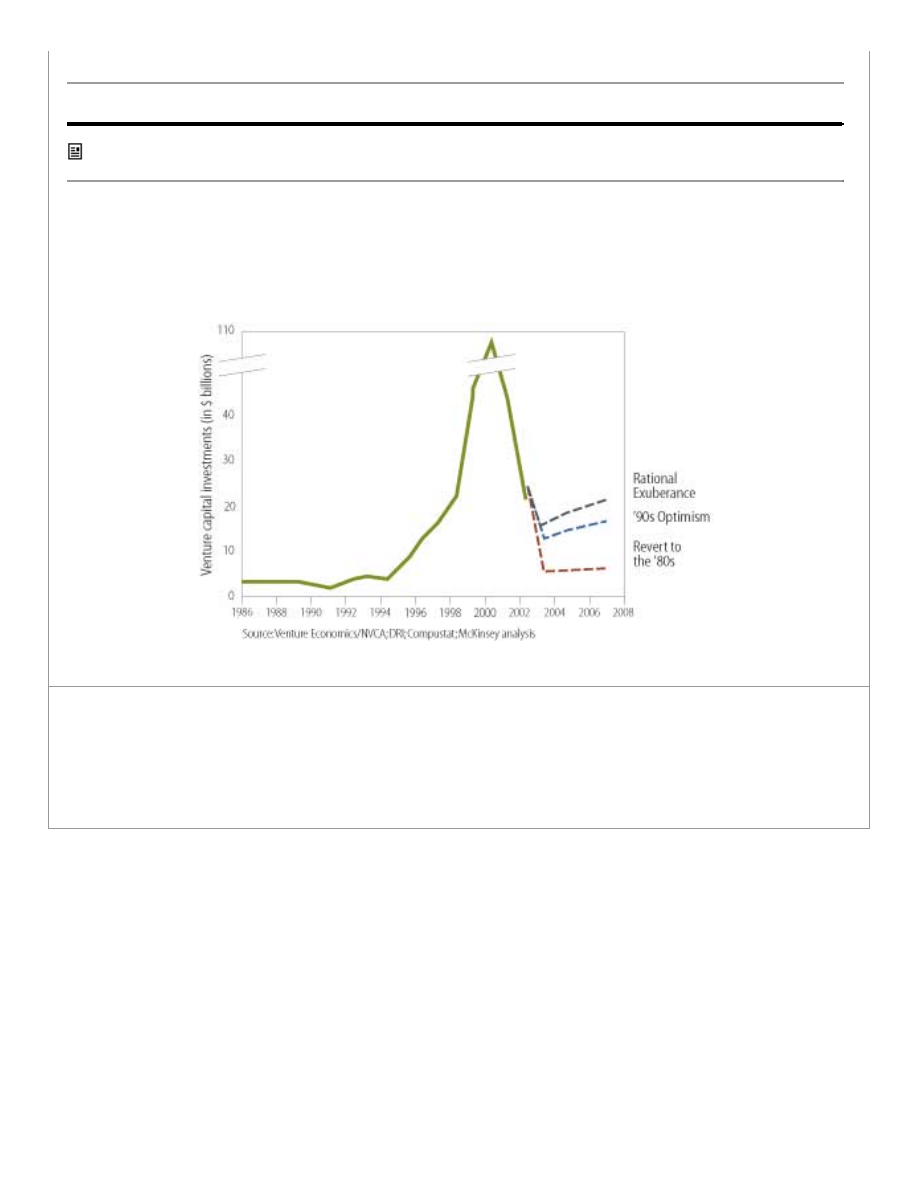

You can get whiplash watching the venture capital industry. Annual U.S. VC investments rocketed from under

$10 billion in the early 1990s to over $100 billion in 2000, then plunged back toward earth when the bubble

burst. It’s not going to be a soft landing. With annual investments now well below $25 billion, our projections

show that a gradual shakeout is likely—one that in the worst case could force up to half of all current VC firms to

close shop over the next several years.

Drawing on public and proprietary data, we analyzed past correlations of VC investments and returns with

changes in GDP, Nasdaq returns, and productivity. Using statistical models, we applied those correlations to

hypothetical future scenarios, yielding three projections for venture investment levels over the next three to five

years. (See the exhibit “Predicting Venture Investments.”)

Predicting Venture Investments

Sidebar F0307D_A (Located at the end of this

article)

Even the most optimistic projection suggests that the VC industry can profitably absorb no more than $15 billion

to $20 billion in annual investment during the next several years. The two other projections, which we think are

more realistic, suggest even less capacity for investment, between $5 billion and $15 billion annually. Currently,

the industry is awash in money and is struggling to invest or return to limited partners an $86 billion capital

overhang, or cumulative excess in uninvested capital. The shrinking capacity to absorb investment, combined

with this excess supply of capital, will likely lead to lower overall returns and an inexorable, gradual shakeout of

existing venture firms. Most vulnerable are firms that raised their first funds during the bubble, a group that

included 25% of all U.S. venture firms by the end of 2001. Nonetheless, history suggests that older, established

firms are not immune.

Following the behavior and fate of the VC industry is important to executives outside the venture capital

community as well as to industry insiders. For decades, venture capital has been a critical force in—and a

leading indicator of—business innovation. VC investment activity provides outsiders with early signs of key

trends emerging in high tech, communications, and biotechnology. These early signs can help executives

monitor technology transitions that may fundamentally disrupt business processes and can, in some industries,

help them track the growth of potential competitors and acquisition targets.

The conspicuous flow of venture capital into semiconductors and computer hardware in the early 1980s, for

example, represented nearly 50% of all venture deals in the first half of that decade, foreshadowing the rapid

expansion of business computing throughout the U.S. economy that followed. Similarly, the recent growth of VC

investment in biotechnology and medical devices—22% of all venture funding in 2002 versus just 6% to 13% in

the bubble years—presages the growing importance of life sciences for both medical and industrial applications.

http://harvardbusinessonline.hbsp.harvard.edu/b02/en/hbr/hbrsa/current/0307/article/F0307DPrint.jhtml (1 of 2) [01-Jul-03 17:48:12]

Harvard Business Review Online | What Venture Trends Can Tell You

Reprint Number F0307D

Predicting Venture Investments

Sidebar F0307D_A

An analysis of the relationship between venture capital investments, Nasdaq returns, and GDP growth suggests

three possible futures for VC investing. The first—Rational Exuberance—assumes 15% annual Nasdaq returns,

3.5% GDP growth, and a correlation between capital investment and GDP growth similar to the levels seen

between 1995 and 1998. The second—‘90s Optimism—assumes 10% Nasdaq returns, 3% GDP growth and an

investment level–GDP correlation similar to the 1990–1994 period. The third scenario—Revert to the

‘80s—assumes 5% annual Nasdaq returns, 2.5% GDP growth, and an investment level–GDP correlation similar

to pre-1990 levels.

Copyright © 2003 Harvard Business School Publishing.

This content may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or

mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without

written permission. Requests for permission should be directed to permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu, 1-

888-500-1020, or mailed to Permissions, Harvard Business School Publishing, 60 Harvard Way,

Boston, MA 02163.

http://harvardbusinessonline.hbsp.harvard.edu/b02/en/hbr/hbrsa/current/0307/article/F0307DPrint.jhtml (2 of 2) [01-Jul-03 17:48:12]

Document Outline

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

2003 07 what really works reprint

2003 07 what really works

4 0 1 2 Let Me Tell You What I Heard at a Conference Instructions

Chuck Berry You Never Can Tell

PF08 Chuck Berry You Never Can Tell

Computer Malware What You Don t Know Can Hurt You

2003 07 32

2003 07 06

2003 07 Szkola konstruktorowid Nieznany

edw 2003 07 s56

atp 2003 07 78

2003 07 33

edw 2003 07 s38(1)

edw 2003 07 s31

2003 07 26

2003 07 10

2003 07 17

edw 2003 07 s12

więcej podobnych podstron