1483

Combination Therapy with Famciclovir and Interferon-a for the Treatment of

Chronic Hepatitis B

Adriana R. Marques, Daryl T. Y. Lau, Robin McKenzie,

1

Stephen E. Straus, and Jay H. Hoofnagle

Laboratory of Clinical Investigation, National Institute of Allergy and

Infectious Diseases, and Liver Disease Section, National Institute of

Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of

Health, Bethesda, Maryland

Interferon-a (IFN-a) treatment results in long-term remissions in only 25%–40% of

patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Famciclovir, the oral prodrug of

penciclovir, inhibits HBV DNA replication. Five adults with chronic HBV infection in

whom previous IFN-a therapy had failed were treated in a pilot study of overlapping IFN-

a and famciclovir therapy totaling 20 weeks. HBV DNA levels decreased by 0.9 log units

during the initial 4-week period of famciclovir alone, followed by a further decrease of 1.8

logs during the middle 12-week period of combination therapy. HBV DNA rose by 0.9 log

during the final 4-week period of IFN-a alone. Two patients cleared HBV DNA, and their

liver disease improved by clinical and histologic criteria. The combination of famciclovir and

IFN-a appeared to be at least additive in suppressing HBV DNA. Efficacy trials of combi-

nation therapy with famciclovir and IFN-a are warranted.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) has infected 2 billion people living

today, of whom 350 million are chronically infected. Of the

estimated 52 million people who died in 1995, HBV is believed

to have contributed to the deaths of

∼1.1 million of them [1].

Interferon-a (IFN-a) is the only drug approved by the US

Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chronic

HBV infection. IFN-a induces long-term remissions in only

25%–40% of treated patients. Therefore, the majority of pa-

tients with chronic HBV infection do not benefit from IFN-a

therapy.

Famciclovir is the oral prodrug of penciclovir, a nucleoside

analogue that is active against herpesviruses. Famciclovir has

been approved for treatment of acute herpes zoster and herpes

simplex virus infections. Penciclovir is also a potent inhibitor

of the HBV DNA polymerase [2] and has been shown to inhibit

HBV replication in vitro and in vivo [3].

The aim of this pilot study was to evaluate the safety and

antiviral and clinical effects of famciclovir alone and when used

Received 15 December 1997; revised 5 June 1998.

Presented in part: 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents

and Chemotherapy, Toronto, 28 September to 1 October 1997 (paper H-

035).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Na-

tional Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and written informed

consent was obtained from each patient. This study was conducted under

an independent IND held by the investigators and followed the guide-

lines for the conduct of research involving human subjects at the National

Institutes of Health.

1

Present affiliation: Johns Hopkins Bay View Medical Center, Baltimore.

Reprints or correspondence: Dr. Adriana R Marques, National Insti-

tutes of Health, Bldg. 10, Room 11N228, 10 Center Dr., Bethesda, MD

(amarques@atlas.niaid.nih.gov).

The Journal of Infectious Diseases

1998; 178:1483–7

This article is in the public domain.

0022-1899

in combination with IFN-a in patients with chronic HBV in-

fection who did not respond to previous therapy with IFN

alone.

Subjects and Methods

Five patients with chronic HBV infection entered and completed

the study. All patients had received previous therapy with IFN-a

without achieving prolonged HBV clearance. These patients were

1

18 years of age; had documented presence of hepatitis B surface

antigen (HBsAg) in serum for at least 6 months; had positive tests

for both hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and HBV DNA in serum

and elevated alanine aminotransferase levels on two or more oc-

casions, at least 1 month apart, during the 6 months before entry;

had compensated liver disease (prothrombin time

!

2 s longer than

normal, serum albumin level

≥3 g/dL, serum bilirubin level ≤4.0

mg/dL, and no history of ascites, wasting, hepatic encephalopathy,

or bleeding esophageal varices); had received no antiviral or im-

munomodulatory therapy for chronic HBV infection within 6

months before study entry; had no significant systemic illnesses

other than liver disease; and had no preexisting bone marrow

compromise, history of pancreatitis, renal insufficiency (creatinine

clearance of

!

60 mL/min or serum creatinine level

1

2.0 mg/100

mL), or coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis

C virus, or delta hepatitis virus.

Patients received famciclovir, 500 mg orally three times a day,

for a total of 16 weeks. After the first 4 weeks of therapy, IFN-a,

5 million units (MU) subcutaneously each day, was added and was

continued for 16 weeks. Thus, therapy was for 20 weeks: an initial

period of 4 weeks with famciclovir alone, a middle 12-week period

with both drugs, and a final period of 4 weeks with IFN-a alone.

Before treatment, all patients initially underwent a thorough

medical evaluation, a battery of blood tests, abdominal ultra-

sound, and percutaneous liver biopsy. During therapy, patients

http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/

Downloaded from

1484

Concise Communications

JID 1998;178 (November)

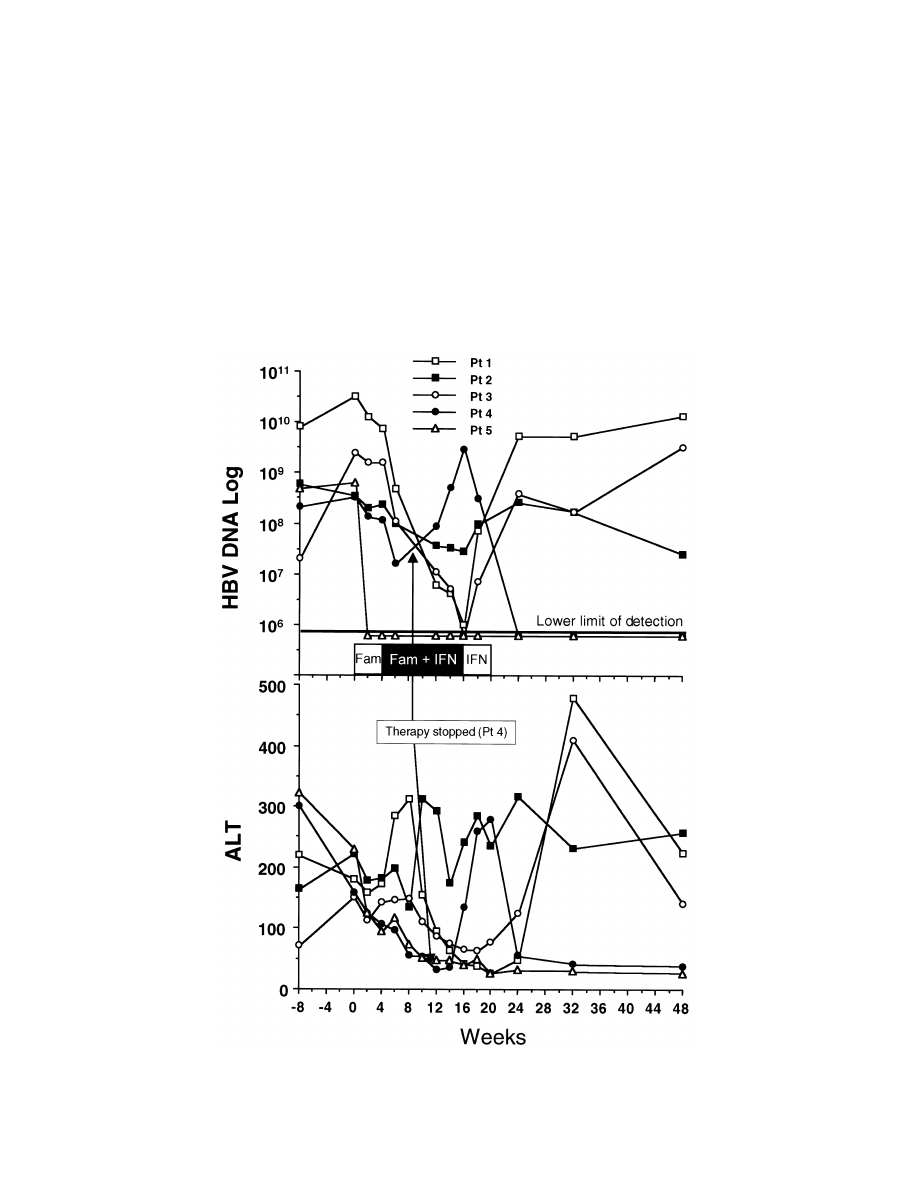

Figure 1.

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values and log changes in serum HBV DNA levels (copies/mL) over time in 5 patients treated

sequentially with famciclovir (Fam), combination therapy (

), and IFN.

Fam

1 IFN

were seen and evaluated every 2 weeks for biochemical and sero-

logic markers of hepatitis and for monitoring of side effects. Pa-

tients were then reevaluated at 1- to 2-month intervals and under-

went a repeat liver biopsy 12 months after starting treatment.

Serum aminotransferases were determined by a sequential

multiple autoanalyzer. HBsAg and HBeAg testing was done by

commercial EIAs (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago). HBV

DNA was quantitated in serum by branched DNA assay (Chiron,

Emeryville, CA), the lower limit of detection being

6

∼ 0.7 3 10

genome equivalents/mL.

The virologic and clinical criteria for responses to treatment

were as follows: A complete virologic response was defined as clear-

ance of both HBV DNA and HBeAg from the serum, whereas a

biochemical response was defined as the fall of serum alanine

aminotransferase levels to within the normal range. Liver biopsy

specimens were graded with respect to the degree of necrosis, in-

flammation, and fibrosis according to the histology activity index

scoring system [4]. A histologic response was defined as a decrease

of at least 3 points in the inflammation score without an increase

in the fibrosis score.

http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/

Downloaded from

JID 1998;178 (November)

Concise Communications

1485

Table 1.

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), histology activity index score, and liver biopsy pathology

in patients before treatment (week 0) and 7 months after stopping therapy (week 48).

Patient

ALT

a

HBV DNA

b

HBeAg

Histology activity

index score

c

Liver pathology

Week 0

Week 48

Week 0

Week 48

Week 0

Week 48

Week 0

Week 48

Week 0

Week 48

1

180

223

32,160

13,140

1

1

15

17

Chronic hepatitis with

marked activity and

bridging fibrosis

Chronic hepatitis with

marked activity and

bridging fibrosis

2

222

256

344

25

1

1

12

12

Chronic hepatitis with

moderate activity and

bridging fibrosis

Chronic hepatitis with

moderate activity and

bridging fibrosis

3

147

140

2490

3176

1

1

11

14

Chronic hepatitis with

mild activity and ex-

tensive nodular frag-

ments, consistent with

cirrhosis

Chronic hepatitis with

marked activity and

bridging fibrosis (in-

complete cirrhosis)

4

158

38

331

!

0.7

1

1

12

8

Chronic hepatitis with

moderate activity and

portal fibrotic

expansion

Chronic hepatitis with

mild activity and early

bridging fibrosis

5

230

25

630

!

0.7

1

2

16

4

Chronic hepatitis with

marked activity and

bridging fibrosis

Chronic hepatitis with

minimal activity and

portal fibrotic

expansion

a

Normal,

!

41 U/L.

b

HBV DNA was quantitated by branched DNA assay. Lower limit of detection:

genome equivalents/mL.

6

0.7

3 10

c

Range of scores: 0–22.

Results

Five men, 25–44 years old, were studied. Three were Cau-

casian and had acquired HBV infection during adulthood; the

other 2 patients were Asian and were believed to have acquired

the infection during infancy or childhood. Symptoms of liver

disease were either absent or mild, fatigue being the only com-

mon symptom. Alanine aminotransferase levels at entry ranged

from 147 to 230 U/L (normal,

!

41). HBV DNA levels ranged

from

to

genome equivalents/mL. The his-

8

10

3.31

3 10

3.2

3 10

tology activity index ranged from 11 to 16 (potential range of

scores, 0–22).

Famciclovir was generally well tolerated; 1 patient required

a dose reduction because of headaches and vertigo. Symptoms

resolved promptly without recurrence despite continuation of

therapy. IFN-a was associated with its expected side effects [5].

Both famciclovir and IFN were stopped after 7 weeks of the

combination in 1 patient (patient 4) because of thrombocyto-

penia (platelet count, 27,000/mm

3

). Platelet counts gradually

returned to baseline levels 4 weeks after stopping therapy.

The changes in the HBV DNA and serum alanine amino-

transferase levels over time for each patient are shown in figure

1. During the initial 4 weeks of famciclovir therapy, HBV DNA

levels decreased in all patients (average decrease, 0.9 log units).

During the combination phase of therapy, HBV DNA levels

decreased on average by a further 1.8 logs. In the final 4 weeks

of IFN-a alone, HBV DNA levels rose from the nadir by an

average of 0.9 log. In general, serum aminotransferase levels

decreased with the decrease of HBV DNA levels during ther-

apy. After stopping therapy, serum aminotransferase levels

increased concurrently with HBV DNA levels. HBV DNA be-

came undetectable during combination therapy in 1 patient who

became HBeAg-negative on follow-up, with normalization of

his serum alanine aminotransferase levels. A second patient,

whose therapy was stopped early because of thrombocytopenia,

had spontaneous resolution of his chronic hepatitis during fol-

low-up. After discontinuation of therapy, his HBV DNA levels

increased, followed by an increase in his serum alanine ami-

notransferase levels. The serum alanine aminotransferase levels

peaked

∼4 weeks after the peak HBV DNA values, associated

with decreasing HBV DNA values. He subsequently had nor-

malization of serum alanine aminotransferase levels and be-

came HBV DNA–negative and intermittently HBeAg-negative.

Both patients had improvement in the inflammation score of

the histology activity index. Despite transient reduction in virus

load during treatment, the other 3 patients continued to be

HBeAg- and HBV DNA–positive. They presented with a mild

flare of serum aminotransferases after stopping therapy, asso-

ciated with an increase in HBV DNA levels. Two patients also

had mild elevations in serum alanine aminotransferase levels

during therapy. Repeat liver biopsies 6–8 months after stopping

therapy showed no improvement in disease activity in these

patients (table 1).

Discussion

Chronic HBV infection can lead to cirrhosis, hepatocellular

carcinoma, and death. The natural history of liver disease

caused by persistent infection with HBV, however, can be quite

http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/

Downloaded from

1486

Concise Communications

JID 1998;178 (November)

variable. Nonetheless, the frequent finding of chronic active

hepatitis or cirrhosis on liver biopsy and the strong link between

HBV infection and hepatocellular carcinoma underscore the

need for effective antiviral therapy [6].

Currently, IFN-a is the only approved treatment for chronic

HBV infection. A 4- to 6-month course of IFN-a in doses of

5 MU daily or 10 MU thrice weekly results in suppression of

HBV replication and improvement in liver disease in 25%–40%

of patients [5]. Studies have shown that individuals maintain

their response during long-term follow-up, and sustained re-

sponders are more likely to have loss of serum HBV DNA

detection by polymerase chain reaction and HBsAg, suggesting

virus clearance [7, 8].

Unfortunately, the majority of patients with chronic HBV

infection do not respond to IFN therapy. Several patient var-

iables have been reported to influence the response to IFN-a.

The features that best predict a beneficial response to treat-

ment are high initial serum aminotransferase levels, low copy

number of circulating viral DNA, active histologic changes

(inflammation and necrosis) and fibrosis in the liver biopsy, a

short duration of the disease, and an absence of complicating

illnesses [9].

Management of the many patients in whom IFN-a therapy

fails is controversial. Retreatment seems to be rarely beneficial.

In a study of retreatment of 10 children with chronic HBV

infection, the response to a second course of IFN therapy

was poor, with only 1 patient becoming HBeAg- and HBV

DNA–negative [10]. In another study of IFN-a retreatment

of adult patients with chronic HBV infection, 2 (11%) of 18

responded to therapy, and 2 additional patients became HBV

DNA–negative with sustained HBeAg positivity [11].

Other approaches to the management of patients in whom

IFN-a therapy initially fails include retreatment with longer

courses of IFN-a, retreatment with IFN-a preceded by a short

course of corticosteroids, or retreatment when the patient

appears to be a better candidate for therapy, that is, when

alanine aminotransferase levels are higher, HBV DNA levels

are lower, or both.

Famciclovir is the oral form of the antiviral compound

penciclovir (9[4-hydroxy-3-hydroxymethylbut-1-yl] guanine).

Penciclovir inhibits duck HBV replication in vitro and in

animal experiments [2, 3]. Recent clinical trials showed fam-

ciclovir to be well-tolerated and to suppress HBV replication

in patients with chronic HBV infection [12, 13]. Famciclovir

has also been shown to decrease HBV replication and improve

liver function in patients with decompensated cirrhosis or re-

current hepatitis B after transplantation [14].

Because the baseline HBV DNA level is an independent

predictor of a response to IFN-a, we tested the hypothesis of

using a nucleoside analogue inhibitor of HBV DNA replication,

famciclovir, to augment the potential for a response to IFN-a.

This strategy underlies phase III studies in which IFN is used

in combination with lamivudine, another nucleoside analogue

with potent activity against HBV, to treat IFN-naive patients

and patients in whom IFN has failed. In a study of 226

IFN-naive patients, who were randomized to lamivudine and

IFN-a or the respective monotherapies, there was no significant

increase in the rate of HBeAg seroconversion [15]. The results

from the combination therapy trial in patients who did not

respond to IFN are not yet available.

In this pilot study, the combination of famciclovir and

IFN-a appeared to be safe and possibly additive in suppress-

ing HBV DNA and resulted in clearance of HBV DNA by

branched DNA assay in 2 of 5 patients, with accompanying

improvement of their liver disease as demonstrated by nor-

malization of serum aminotransferase levels and improvement

of the histology activity index on liver biopsy. One patient also

had clearance of serum HBeAg. It is of interest that both pa-

tients who responded to therapy were Asian men, who probably

acquired the infection in infancy or childhood and are thus less

likely to respond to IFN-a alone. This is an uncontrolled study,

and further follow-up and larger studies are needed to better

discern the rate and durability of serologic and biochemical

responses to this combination treatment regimen.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yoon Park for her help in the care of study participants.

We also thank the members of the Data Safety Monitoring Board,

Judith Falloon, Leslye D. Johnson, and Emil Miskovsky.

References

1. The world health report 1996—fighting disease, fostering development. World

Health Forum 1997; 18:1–8.

2. Korba BE, Boyd MR. Penciclovir is a selective inhibitor of hepatitis B virus

replication in cultured human hepatoblastoma cells. Antimicrob Agents

Chemother 1996; 40:1282–4.

3. Lin E, Luscombe C, Wang YY, Shaw T, Locarnini S. The guanine nucleo-

side analog penciclovir is active against chronic duck hepatitis B virus

infection in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1996; 40:413–8.

4. Knodell RG, Ishak KG, Black WC, et al. Formulation and application of

a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymp-

tomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology 1981; 1:431–5.

5. Hoofnagle JH, di Bisceglie AM. The treatment of chronic viral hepatitis. N

Engl J Med 1997; 336:347–56.

6. Perrillo RP. Interferon in the management of chronic hepatitis B. Dig Dis

Sci 1993; 38:577–93.

7. Niederau C, Heintges T, Lange S, et al. Long-term follow-up of HBeAg-

positive patients treated with interferon alfa for chronic hepatitis B. N

Engl J Med 1996; 334:1422–7.

8. Lau D, Everhart J, Kleiner D, et al. Long term follow-up of patients with

chronic hepatitis B treated with interferon alfa. Gastroenterology 1997;

113:1660–7.

9. Perrillo RP, Schiff ER, Davis GL, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of

interferon alfa-2b alone and after prednisone withdrawal for the treatment

of chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 1990; 323:295–301.

10. Giacchino R, Timitilli A, Cristina E, et al. Repeated course of interferon

treatment in chronic hepatitis B in childhood. Arch Virol Suppl 1992; 4:

273–6.

11. Janssen HL, Schalm SW, Berk L, de Man RA, Heijtink RA. Repeated courses

of alpha-interferon for treatment of chronic hepatitis type B. J Hepatol

1993; 17:S47–51.

http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/

Downloaded from

JID 1998;178 (November)

Concise Communications

1487

12. Trepo C, Atkinson GF, Boon RJ. Efficacy of famciclovir in chronic hepatitis

B: results of a dose finding study [abstract 247]. Hepatology 1996; 24:

188A.

13. Main J, Brown JL, Howells C, et al. A double blind, placebo-controlled study

to assess the effect of famciclovir on virus replication in patients with

chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Viral Hepat 1996; 3:211–5.

14. Singh N, Gayowski T, Wannstedt CF, Wagener MM, Marino IR. Pretrans-

plant famciclovir as prophylaxis for hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver

transplantation. Transplantation 1997; 63:1415–9.

15. Heathcote J, Schalm S, Cianciara J, et al. Lamivudine and intron A com-

bination treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. [abstract

GS2/O7]. J Hepatol 1998; suppl 1:43.

http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/

Downloaded from

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Chronic Pain Syndromes After Ischemic Stroke PRoFESS Trial

Chronic Pain for Dummies

Chronic Pain Syndromes After Ischemic Stroke PRoFESS Trial

Ebsco Farezadi Chronic pain and psychological well being

Evidence for Therapeutic Interventions for Hemiplegic Shoulder Pain During the Chronic Stage of Stro

Chronic Prostatitis A Myofascial Pain Syndrome

Lumbar lordosis and pelvic inclinations in adults with chronic lumbar pain

Serum cytokine levels in patients with chronic low back pain due to herniated disc

Treating Non Specific Chronic Low Back Pain Through the Pilates Method

Chronic Hepatitis

1-Kefir chroni przed mutacjami w DNA, ZDROWIE-Medycyna naturalna, Poczta Zdrowie

Dozwolony użytek chronionych utworów, Kulturoznawstwo UAM, Ochrona właśności intelektualnej

Nauczyciele będą chronieni jak funkcjonariusze publiczni, 03. DLA NAUCZYCIELI

Akumulator do?UTZ?HR COMBINE HARVESTERS M3370 M3380

Jak chronić własne dziecko przed narkotykami

DIY Combination Solar Water and Nieznany

więcej podobnych podstron