image061

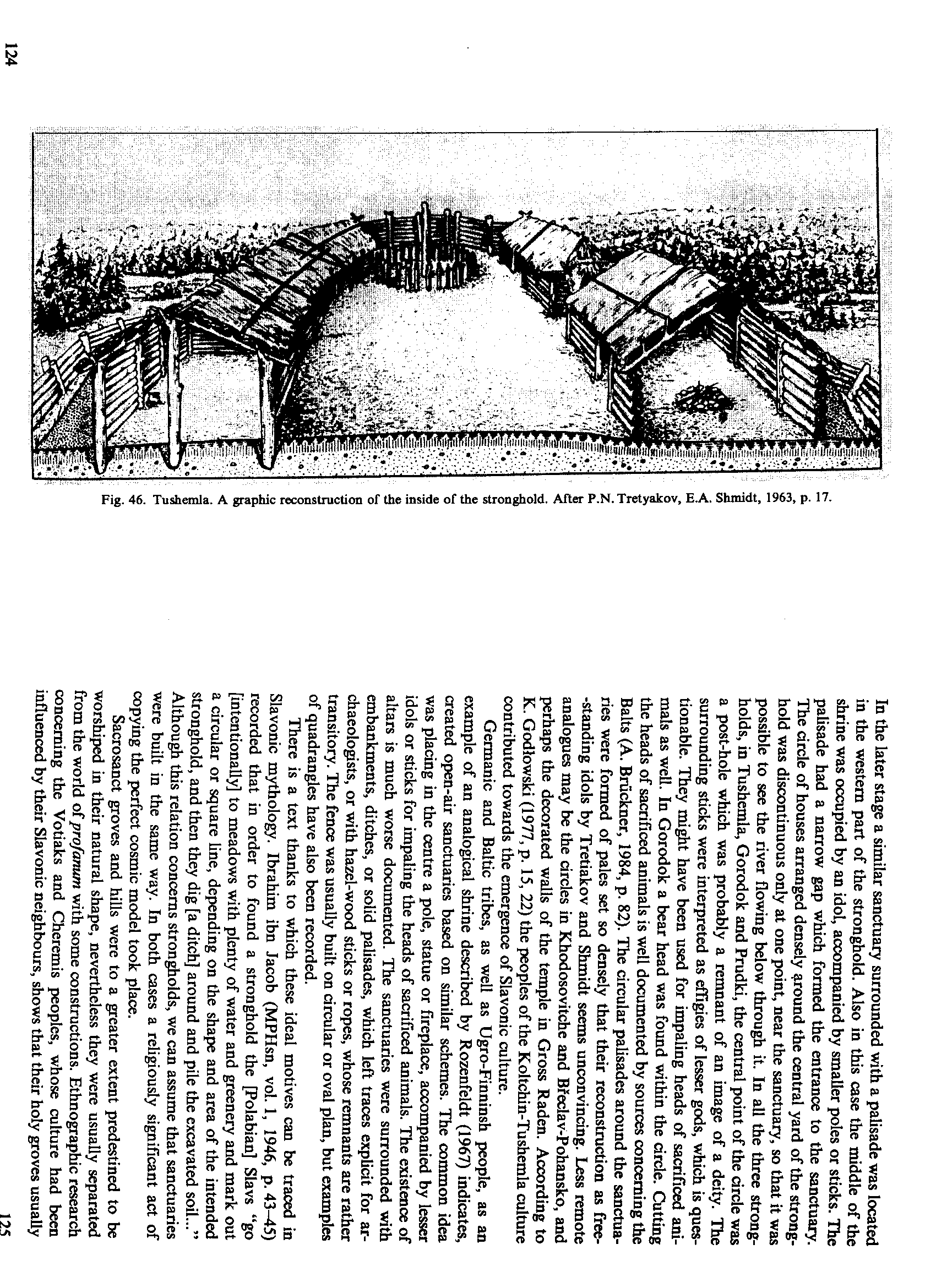

In the later stage a similar sanctuary surrounded with a palisadę was located in the western part of the stronghold. Also in this case the middle of the shrine was occupied by an idol, accompanied by smaller poles or sticks. The palisadę had a narrow gap which formed the entrance to the sanctuary. The tircle of houses arranged densely ^round the central yard of the stronghold was discontinuous only at one point, near the sanctuary, so that it was possible to see the river flowing below through it. In all the three strong-holds, in Tushemla, Gorodok and Prudki, the central point of the drcle was a post-hole which was probably a remnant of an image of a deity. The surrounding sticks were interpreted as effigies of lesser gods, which is ques-tionable. They might have been used for impaling heads of sacrificed ani-mals as well. In Gorodok a bear head was found within the drcle. Cutting the heads of sacrificed animals is well documented by sources conceming the Balts (A. Bruckner, 1984, p. 82). The drcular palisades around the sanctua-ries were formed of pales set so densely that their reconstruction as free--standing idols by Tretiakov and Shmidt seems unconvindng. Less remote analogues may be the drcles in Khodosovitche and Bfeclav-Pohansko, and perhaps the decorated walls of the tempie in Gross Raden. According to K. Godłowski (1977, p. 15, 22) the peoples of the Koltchin-Tushemla culture contributed towards the emergence of Slavonic culture.

Germanie and Baltic tribes, as well as Ugro-Finninsh people, as an example of an analogical shrine described by Rozenfeldt (1967) indicates, created open-air sanctuaries based on similar schemes. The common idea was placing in the centre a pole, statuę or fireplace, accompanied by lesser idols or sticks for impaling the heads of sacrificed animals. The existence of altars is much worse documented. The sanctuaries were surrounded with embankments, ditches, or solid palisades, which left traces explicit for ar-chaeologists, or with hazel-wood sticks or ropes, whose remnants are rather transitory. The fence was usually built on drcular or oval plan, but examples of ąuadrangles have also been recorded.

There is a text thanks to which these ideał motives can be traced in Slavonic mythology. Ibrahim ibn Jacob (MPHsn, vol. 1, 1946, p. 43-45) recorded that in order to found a stronghold the [Polabian] Slavs “go [intentionally] to meadows with plenty of water and greenery and mark out a circular or sąuare linę, depending on the shape and area of the intended stronghold, and then they dig [a ditch] around and pile the excavated soil...” Although this relation concerns strongholds, we can assume that sanctuaries were built in the same way. In both cases a religiously significant act of copying the perfect cosmic model took place.

Sacrosanct groves and hills were to a greater extent predestined to be worshiped in their natural shape, nevertheless they were usually separated from the world of profanum with some constructions. Ethnographic research conceming the Votiaks and Cheremis peoples, whose culture had been influenced by their Slavonic neighbours, shows that their holy groves usually

125

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

141 Hydrological conseąuences of human action.. In the western part of the Lakę Region such waters o

22 Waldemar Deluga 18 ICONOGRAPHY OF THE GREEK CATHOLIC CHURCH In the western part of the Ukrai

31967 musc dev052 care to, at any time, improve yourself in any particular part of your body without

image078 Fig. 66. The sanctuary in Rzhavintse. Top: a plan of the stronghold with sounding excavatio

image002 ORBIT 8 is the latest in this unique series of anthologies of the best new SF. Fourteen sto

image002 ORBIT 4 The latest in a unigue. up to-the minute series of SF arC thologies. ORBIT 4 is “A

image003 In spite of their spece-sutts they felt the scorcltirtg fury of tlić biesi.

image025 IN TIMES TO COME The cover story next monih u "The Sccond Kind of Loncliness," by

image001 In the heart ofłhe Aloskonwilderness, lho greatflłl danger comes nołfrom nat

image002 Meet the new kid on the Scandinavian crime writing błock... One cold morning, in the wind-l

image004 IN THE BECINNING THERE WAS MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT SHELLEYS *. MONUMENTA

image009 IN J8"ES COME The rext issue leads offwith a new novel—"The Outpostcr"—by Go

image009 in times feo come • Gofdon R. CHckson 5 newcst novoi, The Far Cafl,** is a radie*! de* port

image011 IN TIMES TO COME "The Prllcher Mass" łs Ihe tnie ol Gordon R Ockson 9 new novel.

image013 IN THE MATTER OF THE ASSASSIN MEREFIRS The law is an instrument that some men play mor

image019 / In the Juty 1941 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. Robert A. Heinlein s

więcej podobnych podstron