Manual for the use of the

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

A questionnaire measuring cognitive copingstrategies

Nadia Garnefski

Vivian Kraaij

Philip Spinhoven

© Copyright 2002 N.Garnefski, V.Kraaij, P.Spinhoven and DATEC (Leiderdorp, The Netherlands)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or

transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or

otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Manual for the use of the

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

A questionnaire measuring cognitive copingstrategies

Nadia Garnefski

Vivian Kraaij

Philip Spinhoven

1

Preface

This manual has been brought about as a result of a generally prevailing need for a questionnaire

that would be able to measure people's cognitive coping strategies separately from the behavioural

aspects of coping. The CERQ and its corresponding manual are the result of a project which having

started some three years ago will also require our attention in the years to come. Without the

effort of many others we would certainly not have succeeded in developing this questionnaire,

producing the manual and obtaining norm tables. Therefore, we wish to thank everyone who

directly or indirectly took part in bringing about this manual, especially all students who assisted

and thought along with us while collecting our data, the Koning Willem I College in Den Bosch and

all other schools that participated in our study, the Rijngeest Group in Leiden (formerly: Jelgersma

Policlinic), the Delft general practitioners' practice, as well as all secondary school students and

others who on a voluntary basis participated in our study and completed our questionnaire.

In the years to come we will continue our validity research. We therefore ask those who will use

this instrument in the future, to inform us of the results obtained and their (positive and negative)

experiences with this questionnaire. We will be grateful for any comments and suggestions.

Nadia Garnefski

Vivian Kraaij

Philip Spinhoven

∗

Leiden University

Division of Clinical and Health Psychology

P.O. Box 9555, 2300 RB Leiden

E-mail: Garnefski@fsw.leidenuniv.nl

2

3

Contents

Preface.....................................................................................................

1

Chapter 1: Introduction.................................................................................

5

Background.......................................................................................

5

Chapter 2: Description of the CERQ..................................................................

7

Meaning of the CERQ scales....................................................................

7

Description of the CERQ items................................................................. 8

Administering the CERQ........................................................................

9

Instructions for completing the CERQ.......................................................

9

Scoring the CERQ................................................................................

10

Using the CERQ in different populations.....................................................

10

Using the CERQ for diagnostic purposes...................................................... 10

Using the CERQ for scientific purposes....................................................... 11

Chapter 3: Description of the norm groups.........................................................

13

Chapter 4: Psychometric Properties of the CERQ.................................................

15

Dimensional structure of the CERQ...........................................................

15

Internal consistency: Cronbach's alpha....................................................... 17

Item-rest correlations........................................................................... 17

Stability (test-retest reliabilities)............................................................

19

Correlations between the CERQ scales.......................................................

20

Factorial validity................................................................................

20

Discriminative properties......................................................................

22

Construct validity...............................................................................

22

Chapter 5: Standardization of the CERQ............................................................

29

Interpreting the CERQ scale scores...........................................................

29

Group differences: means and standard deviations of the norm groups...............

29

Standardization..................................................................................

30

Norm tables....................................................................................... 30

Instruction for use of the norm tables.......................................................

31

Interpretation of scores on the CERQ scales................................................

32

References................................................................................................. 35

APPENDIX: CERQ Norm Tables.........................................................................

37

4

5

Chapter1

Introduction

The CERQ (Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire) is a multidimensional questionnaire

constructed in order to identify the cognitive coping strategies someone uses after having

experienced negative events or situations. Contrary to other coping questionnaires that do not

explicitly differentiate between an individual's thoughts and his or her actual actions, the present

questionnaire refers exclusively to an individual's thoughts after having experienced a negative

event. The CERQ is a very easy to administer, self-report questionnaire consisting of 36 items. The

questionnaire has been constructed both on a theoretical and empirical basis and measures nine

different cognitive coping strategies. The CERQ makes it possible to identify individual cognitive

coping strategies and compare them to norm scores from various population groups. In addition, the

questionnaire offers the opportunity to investigate relationships between the use of specific

cognitive coping strategies, other personality variables, psychopathology and other problems.

The CERQ can be administered in normal populations and clinical populations, both with adults and

adolescents aged 12 years and over. The CERQ can be used to measure someone's general cognitive

style as well as someone's cognitive strategy after having experienced a specific event. The

questionnaire has a Dutch and an English version.

Background

The regulation of emotions through cognitions is inextricably associated with human life. Cognitions

or cognitive processes help people regulate their emotions or feelings and not get overwhelmed by

the intensity of these emotions, for example during or after experiencing a negative or stressful life

event. Cognitive processes can be divided into unconscious (e.g. projection or denial) and conscious

cognitive processes, such as self-blame, other-blame, rumination and catastrophizing. The CERQ

focuses on the latter category, i.e. the self-regulating, conscious cognitive components of emotion

regulation. Although not many studies have explicitly addressed the cognitive side of emotion

regulation, within general coping research some attention has been given to these strategies.

A generally accepted definition of coping is given by Monat & Lazarus (1991, p.5) as “an individual's

efforts to master demands (conditions of harm, threat or challenge) that are appraised (or

perceived) as exceeding or taxing his or her resources”. It is common use to distinguish two major

functions of coping: 1) problem-focused coping, which comprises all coping strategies directly

addressing the stressor; and 2) emotion-focused coping, which includes the coping strategies aimed

at regulating the emotions associated with the stressor (Compas, Orosan & Grant, 1993). In general,

problem-focused coping strategies are considered to be more functional than emotion-focused

coping strategies (Thoits, 1995).

Although the above division of coping strategies refers to a generally accepted and much used

division and many coping instruments are based on it, it gives rise to a major conceptual problem,

i.e. that the division into problem-focused and emotion-focused coping is not the only dimension by

which coping strategies can be classified.

6

In fact, there is another major dimension that goes right across the boundaries of this division,

namely the cognitive (what you think) versus the behavioural (what you do) dimension (see also

Holahan, Moss & Schaeffer, 1996). An example of cognitive problem-oriented coping is 'making

plans'; an example of behavioural problem-oriented coping is 'taking immediate action'. Although

'making plans' (thinking about what you will do) and 'taking action' (actually acting) clearly refer to

different processes that are used at different moments in time, and 'making plans' does not always

mean that they will actually be carried out, generally speaking they are categorized under one and

the same dimension. As for the existing coping instruments it therefore applies that most coping

scales are composed of a mixture of cognitive and behavioural coping strategies, until now it has

not been possible to measure cognitive coping strategies separately from the behavioural coping

strategies. Although in the past few decades the relationship between the various coping strategies

and psychopathology has clearly been established (for reviews, see: Compas, Connor-Smith,

Saltzman, Harding Thomsen & Wadsworth, 2001; Endler & Parker, 1990; Thoits, 1995), it has hardly

resulted in insight into the extent to which certain influences could be specifically attributed to the

cognitive aspects of coping. Although considerable attention has been given to cognitive processes

as regulating mechanisms for certain developmental processes, as yet we do not know much of the

degree to which cognitive coping strategies regulate emotions and how it influences the course of

emotional processing after having experienced negative life events.

The CERQ has been developed in order to fill in this gap. The CERQ therefore measures 'cognitive'

coping strategies exclusively, separate from the 'behavioural' coping strategies.

7

Chapter 2

Description of the CERQ

The CERQ is a self-report questionnaire measuring cognitive coping strategies of adults and

adolescents aged 12 years and more. In other words, with the help of this questionnaire it can be

assessed what people think after having experienced a negative or traumatic event.

Cognitive coping strategies are defined here as strategies for cognitive emotion regulation, that is,

regulating in a cognitive way the emotional responses to events causing the individual emotional

aggravation (Thompson, 1991).

Cognitive coping strategies are assumed to refer essentially to rather stable styles of dealing with

negative life events, however not to such an extent that they can be compared to personality

traits. It is assumed that in certain situations people may use specific cognitive strategies, which

may divert from the strategies they would use in other situations. It may also be assumed that

potentially cognitive coping strategies can be influenced, changed, learned or unlearned, for

example through psychotherapy, intervention programmes or one’s own experiences.

Meaning of the CERQ scales

The CERQ distinguishes nine different cognitive coping strategies, of which, independently from

one another, clinical psychological literature has established their association with

psychopathology. These are:

1. Self-blame, referring to thoughts of blaming yourself for what you have experienced (Anderson,

Miller, Riger & Sedikides, 1994);

2. Acceptance, referring to thoughts of resigning to what has happened (Carver, Scheier &

Weintraub, 1989);

3. Rumination, referring to thinking all the time about the feelings and thoughts associated with

the negative event (Nolen-Hoeksema, Parker & Larson,1994);

4. Positive Refocusing, which refers to thinking of other, pleasant matters instead of the actual

event (Endler & Parker, 1990);

5. Refocus on Planning, or thinking about what steps to take in order to deal with the event

(Carver, et al., 1989; Folkman & Lazarus, 1989);

6. Positive Reappraisal, or thinking of attaching a positive meaning to the event in terms of

personal growth (Carver, et al, 1989; Spirito, Stark & Williams, 1988);

7. Putting into Perspective or thoughts of playing down the seriousness of the event when

compared to other events (Allan & Gilbert, 1995);

8. Catastrophizing, referring to explicitly emphasizing the terror of the experience (Sullivan,

Bishop and Pivik, 1995); and

9. Other-blame, referring to thoughts of putting the blame for what you have experienced on

others (Tennen & Affleck, 1990).

8

Description of the CERQ items

The questionnaire consists of 36 items, each referring exclusively to what someone thinks and not

to what someone actually does, when experiencing threatening or stressful life events. The items

are divided up proportionally over the nine scales, so that all CERQ subscales consist of 4 items.

Below the names of the subscales with their matching items (numbers corresponding with the

numbers of the items in the questionnaire itself) are given.

1) Self-blame

1. I feel that I am the one to blame for it

10. I feel that I am the one who is responsible for what has happened

19. I think about the mistakes I have made in this matter

28. I think that basically the cause must lie within myself

2) Acceptance

2. I think that I have to accept that this has happened

11. I think that I have to accept the situation

20. I think that I cannot change anything about it

29. I think that I must learn to live with it

3) Rumination

3. I often think about how I feel about what I have experienced

12. I am preoccupied with what I think and feel about what I have experienced

21. I want to understand why I feel the way I do about what I have experienced

30. I dwell upon the feelings the situation has evoked in me

4) Positive Refocusing

4. I think of nicer things than what I have experienced

13. I think of pleasant things that have nothing to do with it

22. I think of something nice instead of what has happened

31. I think about pleasant experiences

5) Refocus on Planning

5. I think of what I can do best

14. I think about how I can best cope with the situation

23. I think about how to change the situation

32. I think about a plan of what I can do best

6) Positive Reappraisal

6. I think I can learn something from the situation

15. I think that I can become a stronger person as a result of what has happened

24. I think that the situation also has its positive sides

33. I look for the positive sides to the matter

7) Putting into Perspective

7. I think that it all could have been much worse

16. I think that other people go through much worse experiences

25. I think that it hasn’t been too bad compared to other things

34. I tell myself that there are worse things in life

9

8) Catastrophizing

8. I often think that what I have experienced is much worse than what others have experienced

17. I keep thinking about how terrible it is what I have experienced

26. I often think that what I have experienced is the worst that can happen to a person

35. I continually think how horrible the situation has been

9) Other-blame

9. I feel that others are to blame for it

18. I feel that others are responsible for what has happened

27. I think about the mistakes others have made in this matter

36. I feel that basically the cause lies with others

Administering the CERQ

The CERQ can be administered both individually and in groups, using a computer or a pen-and-

paper version. The room in which the questionnaire will be completed needs to offer good

conditions for the subjects to concentrate: no distractions, no interfering noise, sufficient light,

and in the case of administration in a group, a placing so that there is enough room to complete the

questionnaire undisturbed and in private. As a rule, completing the CERQ takes less than 10

minutes.

Instructions for completing the CERQ

The CERQ can be used to measure cognitive coping styles as well as to measure a specific response

to a specific event. In order to assess which cognitive coping strategies people usually use when

experiencing something-unpleasant (cognitive coping style) the following (standard) instruction is

given at completion:

Everyone gets confronted with negative or unpleasant experiences and everyone responds to

them in his or her own way. By the following questions, you are asked to indicate what you

generally think, when you experience negative or unpleasant events. Please read the

sentences below and indicate how often you have the following thoughts by circling the

most suitable answer.

To assess which cognitive coping strategies people use when dealing with a specific event,

situation, trauma or illness, the instruction is adjusted to the specific circumstances. An example of

a specific (standard) instruction to be given at completion:

You have experienced (fill in the specific event). More people have had similar experiences,

and everyone deals with them in his or her own way. By means of the following questions,

you are asked what you think about experiencing (fill in specific event). Please read the

sentences below and indicate how often you have the following thoughts by circling the

most suitable answer.

Explain clearly that completing the questionnaire is about people's own views and that right or

wrong answers do not exist.

10

Scoring the CERQ

When completing the questions subjects themselves indicate on a five-point scale to which extent –

'(almost) never' (1), 'sometimes' (2), 'regularly' (3), 'often' (4), or '(almost) always' (5) – they make

use of certain cognitive coping strategies.

Of the 4 items included in a scale a sum score is made (simple straight count), which can range

from 4 (never used) to 20 (often used cognitive coping strategy). Not more than 1 of the 4 items

included in a scale may be 'missing'. In that case, the 'missing' score is replaced by the average of

the three remaining scores. In this manner, even in the case of a missing value, a scale score

ranging from 4 to 20 is obtained.

Using the CERQ in different populations

The CERQ is suitable for use in different populations such as adolescents, adults, elderly people,

students and psychiatric patients. Besides, experience has been gained in administering the

questionnaire to groups of various educational backgrounds. It has also turned out that the CERQ

can be very well administered in a number of specific populations, such as chronically ill

adolescents, individuals with fear of flying, groups of people characterized by having experienced

similar types of traumatic events (stalking, foot-and-mouth crisis).

The CERQ is also available in a Dutch version (Garnefski, Kraaij & Spinhoven, 2002).

Using the CERQ for diagnostic purposes

The CERQ can be used to diagnose individuals, with the purpose of assessing to which extent

someone deviates from his or her norm group regarding the use of the nine specific cognitive coping

strategies. In this manner the extent can be assessed to which someone uses adaptive and non-

adaptive cognitive coping strategies when dealing with negative events. This information can be

important to decide about the aim and content of treatment. For example, a starting point for

treatment could be to unlearn non-adaptive cognitive coping strategies and to learn adaptive

strategies.

Empirical research with the CERQ shows that especially the extents of Rumination, Catastrophizing

and Self-blame are related to reporting symptoms of psychopathology. These apparently non-

adaptive types of cognitive coping could therefore be an important line of approach for prevention

and/or treatment. Also, outcomes of the above research suggest a sort of 'protective' effect from

other cognitive coping strategies, such as Positive Reappraisal and Positive Refocusing. These could

perhaps be good starting points to learn functional cognitive coping strategies (Garnefski, Boon, &

Kraaij, 2003; Garnefski, van den Kommer, Kraaij, Teerds, Legerstee & Onstein, 2002

a

; Garnefski,

Kraaij & Spinhoven, 2001

a

; Garnefski, Kraaij & Spinhoven, 2001

b

; Garnefski, Legerstee, Kraaij, van

den Kommer & Teerds, 2002

c

; Garnefski, Teerds, Kraaij, Legerstee & van den Kommer, 2003;

Kraaij, Garnefski & van Gerwen, 2003; Kraaij, Garnefski, de Wilde, Dijkstra, Gebhardt, Maes & ter

Doest; 2003; Kraaij, Pruymboom & Garnefski, 2002).

11

Using the CERQ for scientific purposes

A major motive underlying scientific research is the identification of risk factors and protective

factors associated with the development and continuation of emotional and behavioural problems.

So far, empirical research involving the CERQ has demonstrated that cognitive coping strategies

themselves, i.e. without the behavioural component, are very well capable of predicting a

considerable part of the variance in scores of depression, anxiety and suicidality (e.g., Garnefski et

al, 2001

a

; Garnefski et al, 2001

b

; Garnefski et al, 2002

a

). This suggests, therefore, that the

cognitive side of coping is an important component deserving further research in a conceptually

unadulterated manner, i.e. without being mixed with behavioural components. It also suggests that

cognitive coping strategies should play an important and central role in theoretical models intended

to explain mental health problems.

The outcomes of the research carried out so far show that for various problems it is true that

symptom 'promoting' and 'protective' cognitive coping strategies can be identified. This is an

important finding, suggesting that in order to obtain a proper picture of the relationship between

cognitive coping and emotional dysfunctioning the combined action of the different strategies

requires further investigation. In this regard it could be of importance to investigate to what extent

cognitive coping profiles can be distinguished as well as the relationship between certain profiles

and psychopathology. For instance, the outcomes of the above research suggest that the presence

of symptoms of depression, anxiety or suicidality could point at the use of – perhaps long-

established – non-adaptive cognitive coping strategies like Rumination, Catastrophizing and Self-

blame.

12

13

Chapter 3

Description of the norm groups

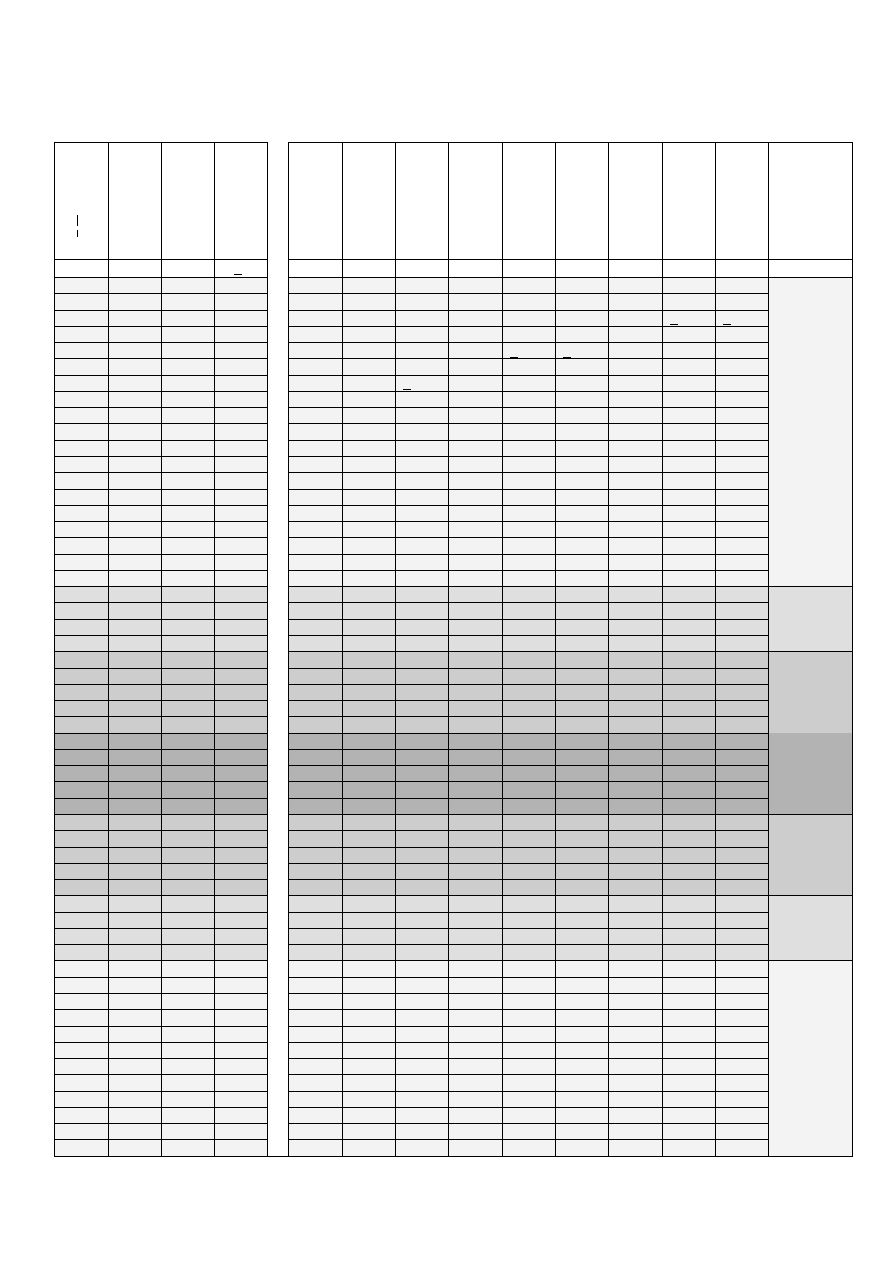

Table 1 gives an overview of the norm groups used in this manual. Below, four samples from the

general population are listed: 1) 586 adolescents 13-to-15 years of age; 2) 986 adolescents 16-to-18

years of age; 3) 611 adults from the general population, 18-to-65 years of age; and 4) 99 individuals

aged 66 years and over. In addition, data were collected from 218 adult psychiatric patients aged

18-to-65 years (5). From the Adults General Population follow-up data have also been collected.

Table 1: CERQ norm groups

Sample

Males

Females

Follow-up?

1. Early Adolescents (13-15)

253

333

-

2. Late Adolescents (16-18)

417

562

-

3. Adults General Population (18-65)

242

369

yes

4. Elderly People (66-97)

51

47

-

5. Psychiatric Patients(18-65)

92

121

-

Below, more specific information is given with regard to the data collection and characteristics of

the above samples.

1) Early Adolescents

The data for this sample have been collected at three different secondary schools in the west of

the Netherlands. This group completed the questionnaires during school hours in their own

classroom, under the supervision of a teacher and two psychology students. The study took place in

March 1998. The sample consisted of 586 adolescents aged between 13 and 15 years. The mean age

was 13 years and 11 months, the standard deviation being 0.69. There were 253 (43%) boys and 333

(57%) girls. The division over the various educational levels was as follows: 21 (4%) pupils attending

lower vocational education (VBO), 104 (18%) pupils attending lower secondary general education

(MAVO), 229 (39%) pupils attending higher general secondary education (HAVO) and 232 (40%) pupils

attending pre-university education (VWO). The sample consisted of second and third grade pupils.

2) Late Adolescents

This sample comes from a large school for intermediate vocational education in the south-east of

the Netherlands. Here, too, the questionnaires were completed at school, under the supervision of

two psychology students. This survey was carried out in October 1999. The sample consisted of 986

adolescents in the age group 16-to-18 years. The mean age was 16 years, 11 months, the standard

deviation being 0.75. There were 417 (43%) boys and 562 (57%) girls, all of whom were first-year

students.

14

3) Adults General Population

This sample comes from the directory of a family practice in a medium-sized town in the west of

the Netherlands. Following a written mailing in January 2000, 611 people aged between 18 and 65

years participated in the study on an individual basis. 242 (40%) of them were male and 369 (60%)

female. The mean age was 41 years, 11 months, the standard deviation being 11.51. Of the

respondents 383 (63%) individuals indicated to be married, engaged or living together. 216 (35%)

were either single or divorced. The educational level ranged from primary school (4%), lower

vocational (LBO) or lower general secondary education (MAVO/MULO) (20%), intermediate

vocational education (MBO) (16%), higher general secondary and pre-university education

(HBS/MMS/HAVO/VWO) (11%), to higher vocational and university education (48%).

From this sample follow-up data were collected after 14 months, again by means of a written

mailing. 290 individuals participated, of which 109 (38%) were male and 181 (62%) female.

4) Elderly People

This group comes from an earlier sample of people aged 65 years and over from the municipal

directory of a medium-sized town in the west of the Netherlands. Following a written mailing and a

telephone call in March 2000, 99 people aged 66-to-97 years participated individually in the survey.

52% of them were female, 48% male. The mean age was 77 years, 2 months, the standard deviation

being 6.12. Of the respondents 50 (52%) indicated to be married or living together, 41 (42%) had

been widowed, and 6 (6%) were divorced or had never married. The majority (92%) lived on their

own, the others lived in an old people's home (3%), sheltered accommodation (3%) or in different

conditions (2%).

5) Psychiatric Patients

The data of this group were collected among outpatients of a psychiatric institution in the west of

the Netherlands. With this group, completing the CERQ was part of a larger set of questionnaires

that they had to fill out before the interview on admission to this clinic. For that reason the

questionnaire was completed on an individual basis. The survey took place between November 1999

and June 2001. 218 people aged 18-to-65 years participated, of whom 92 (43%) were male and 121

(57%) female. The mean age was 35 years, 8 months, the standard deviation being 11.32. Of the

respondents 113 (53%) indicated to be married, engaged or living together, 101 (47%) people were

either widowed, single or divorced. The educational level ranged from primary school (16%), lower

vocational (LBO) or lower general secondary education (MAVO/MULO) (32%), intermediate

vocational education (MBO) (10%), higher general secondary and pre-university education

(HBS/MMS/HAVO/VWO) (22%), to higher vocational and university education (18%).

15

Chapter 4

Psychometric properties of the CERQ

This chapter deals with various aspects concerning the internal structure, reliability and validity of

the CERQ.

Dimensional structure of the CERQ

First of all, in order to define the dimensional structure a Principal Component Analysis with

Varimax-rotation on item level was performed for the group of Early Adolescents aged 13-to-15

years, as this was the first group involved in a publication about the CERQ (Garnefski et al., 2001

a

;

Garnefski et al., 2001

b

; Garnefski et al., 2002

a

). The factor loadings matrix for this group is

represented in Table 2. This table shows all factor loadings >.40. From the curves of the plotted

eigenvalues it appeared that the nine-factor solution was quite justifiable. Eight factors had an

eigenvalue > 1, while the ninth factor had an eigenvalue of .97. The values of the communalities

ranged from .47 to .74. In the population of Early Adolescents the nine factors together explained

in all 64.4% of the variance. Table 2 shows also that the factors found were consistent with the

intended nine-factor structure. Almost all items included in one and the same dimension on a

theoretical basis, turned out to actually load on one and the same dimension on an empirical basis,

in most cases with a factor loading exceeding .40. Some deviations from the proposed structure

were found, though. For instance, one of the items of the scale 'Other-blame' loaded .34, i.e.

below .40. Also, the scales Refocus on Planning and Positive Reappraisal turned out to show some

overlap. Two of the items that theoretically should load on the dimension belonging to the other

items of Positive Reappraisal, appeared to load much stronger on the dimension made up by the

items belonging to Refocus on Planning. The two remaining items of the Positive Reappraisal scale

did indeed have a high factor loading on 'their own' dimension. This overlap could be explained by

strong correlations between items of the Refocus on Planning and Positive Reappraisal scales. For

further interpretation it is important to examine carefully whether the two scales separately still

show enough internal consistency.

In a further phase of the study the generalisability of these factors was examined. For this purpose

Principal Component Analyses were also performed for the remaining populations we studied,

namely the Late Adolescents (age 16-18), the Adults General Population (age 18-65), the Elderly

People (age 66-97) and the Psychiatric Patients (age 18-65). The Principal Component Analysis of

the Late Adolescents showed that in this group nine factors explained 62.2% of the variance. The

factor structure in this group proved to be roughly similar to the group of Early Adolescents. In this

group, too, the first two items of Positive Reappraisal ended up on one dimension with Refocus on

Planning, while the two remaining items of Positive Reappraisal made up their own dimension.

Apart from this, no deviations from the intended structure were found in this group, while almost

all factor loadings belonging to the dimension in question had values exceeding .40.

With the Adults the nine factors also explained a considerable part of the variance (68.1%). Here,

too, almost all factors were in accordance with the proposed structure, with factor loadings which

all turned out to exceed .59. The only deviation from the structure (also compared with the Early

Adolescents group) was that in the Adults group all items belonging to the Refocus on Planning and

Positive Reappraisal scales ended up on one dimension.

Here again, it is true that a careful inspection of the internal consistency of the two scales is

important.

16

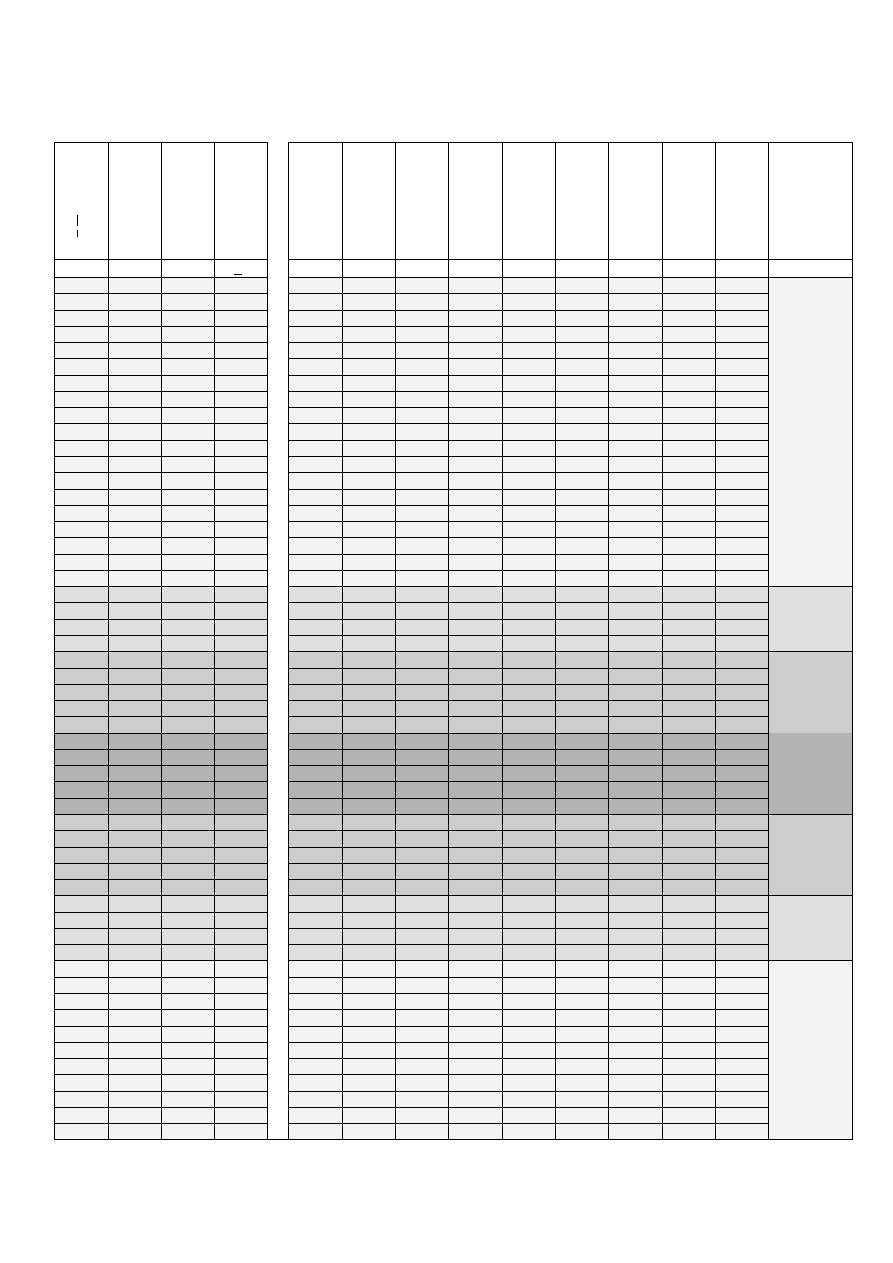

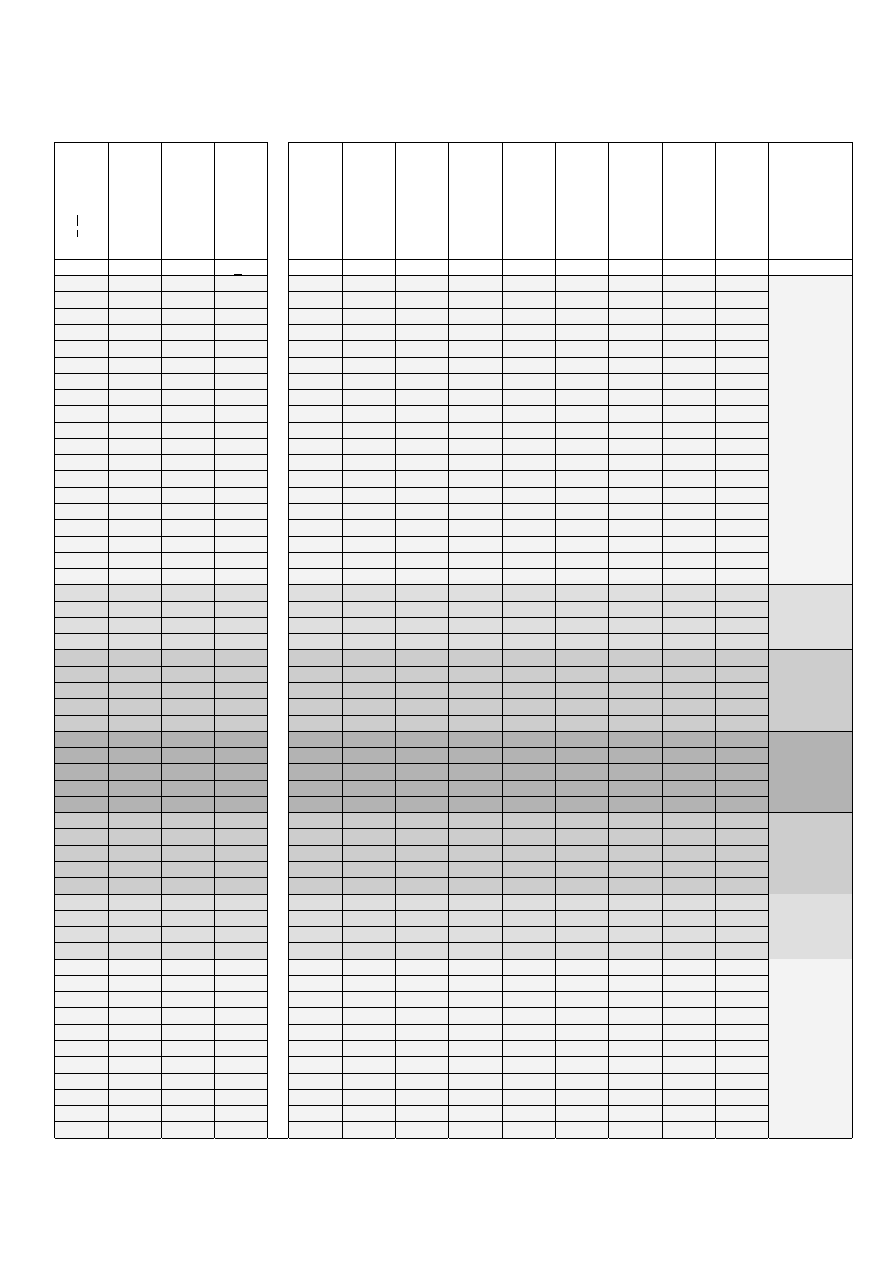

Table 2: Factor loadings PCA after Varimax rotation, Early Adolescents age 13-15 years

Components

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Self-blame

CERQ1

.72

CERQ10

.77

CERQ19

.57

CERQ28

.80

Acceptance

CERQ2

.66

CERQ11

.69

CERQ20

.59

CERQ29

.69

Rumination

CERQ3

.78

CERQ12

.73

CERQ21

.61

CERQ30

.60

Positive Refocusing

CERQ4

.81

CERQ13

.81

CERQ22

.66

CERQ31

.65

Refocus on Planning

CERQ5

.65

CERQ14

.62

(.44)

CERQ23

.50

(.41)

CERQ32

.59

Positive Reappraisal

CERQ6

.62

(.28)

CERQ15

.60

(.04)

CERQ24

.64

CERQ33

.58

Putting into Perspective

CERQ7

.72

CERQ16

.67

CERQ25

.55

CERQ34

.67

Catastrophizing

CERQ8

.58

CERQ17

.69

CERQ26

.77

CERQ35

.59

Other-blame

CERQ9

.78

CERQ18

.54

CERQ27

(.46)

(.34)

CERQ36

.79

17

With the Elderly People the nine factors explained 69.8% of the variance. As with the Adults group,

with this group the items belonging to the Refocus on Planning and Positive Reappraisal scales

turned out to have ended up on one dimension. Furthermore, with this group the items belonging

to Rumination and Catastrophizing also appeared to load on one and the same dimension. The

remaining dimensions were fully in accordance with the intended structure, with factor loadings of

.40 and more.

With the Psychiatric Patients group yet again the general tendency was confirmed that items

belonging to the Refocus on Planning and Positive Reappraisal scales loaded on one dimension. All

of the remaining items turned out to load on the intended dimension, in all cases with a factor

loading exceeding .40. In this group the percentage of explained variance was 68.1%

From the various Principal Component Analyses there clearly emerge comparable pictures. In all

cases the dimensions explain over 60% of the variance. In most cases the dimensions are in full

accord with the scales established on a theoretical basis. The only consistent exception is the

overlap between the items belonging to the Refocus on Planning and Positive Reappraisal scales. In

most cases these items ended up on one and the same dimension. This is probably due to the rather

strong correlation between these two scales (varying from .62 with the Early Adolescents to .75

with the Elderly People). However, the internal consistency coefficients in the next section

demonstrate that the two scales in question can in fact be distinguished as two separate, reliable

scales. Also on a theoretical basis it is important to keep distinguishing these two subscales clearly

as two different concepts. While the concept of Refocus on Planning clearly focuses on thinking

about what steps to take in order to cope with the event (action-oriented), the concept of Positive

Reappraisal focuses on attributing a positive meaning to the event in terms of personal growth

(emotion-oriented). Also in the existing literature in the field of coping the two concepts are

clearly distinguished from each other. Still, the Principal Components Analyses and the correlation

analyses make it clear that the two concepts are closely linked. Therefore, this is certainly

important to take into account when interpreting the scores.

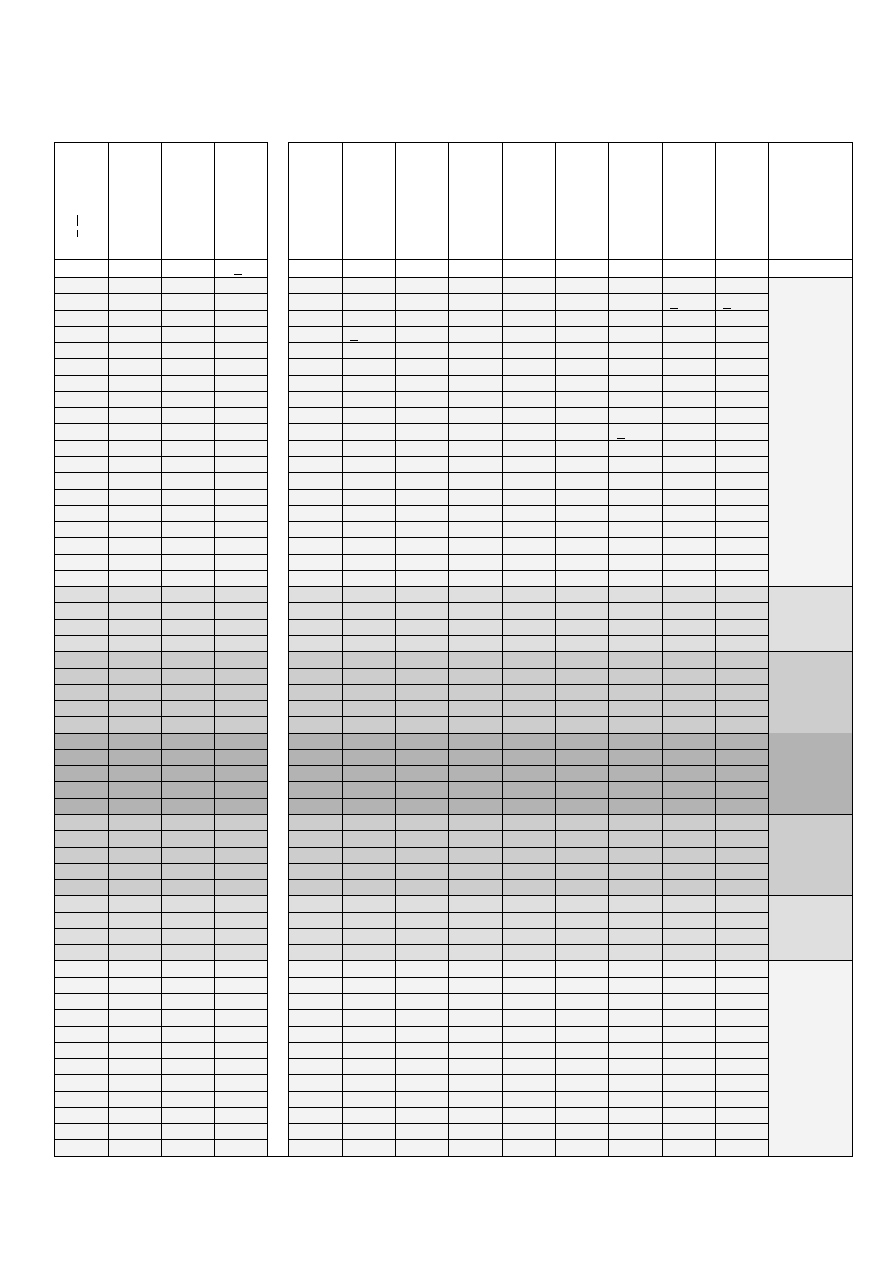

Internal consistency: Cronbach's alpha

To assess the internal consistency of the nine CERQ scales alpha coefficients were computed in all

research populations, the outcomes of which are given in Table 3. Generally speaking it can be

concluded that the alpha coefficients of the various subscales across the diverse populations can be

called good to very good (in most cases well over .70 and in many cases even over .80). Even the

lowest values, like .68 for Self-blame with the Late Adolescents and .68 for Other-blame with the

Early Adolescents are still acceptable when the number of items per scale is considered.

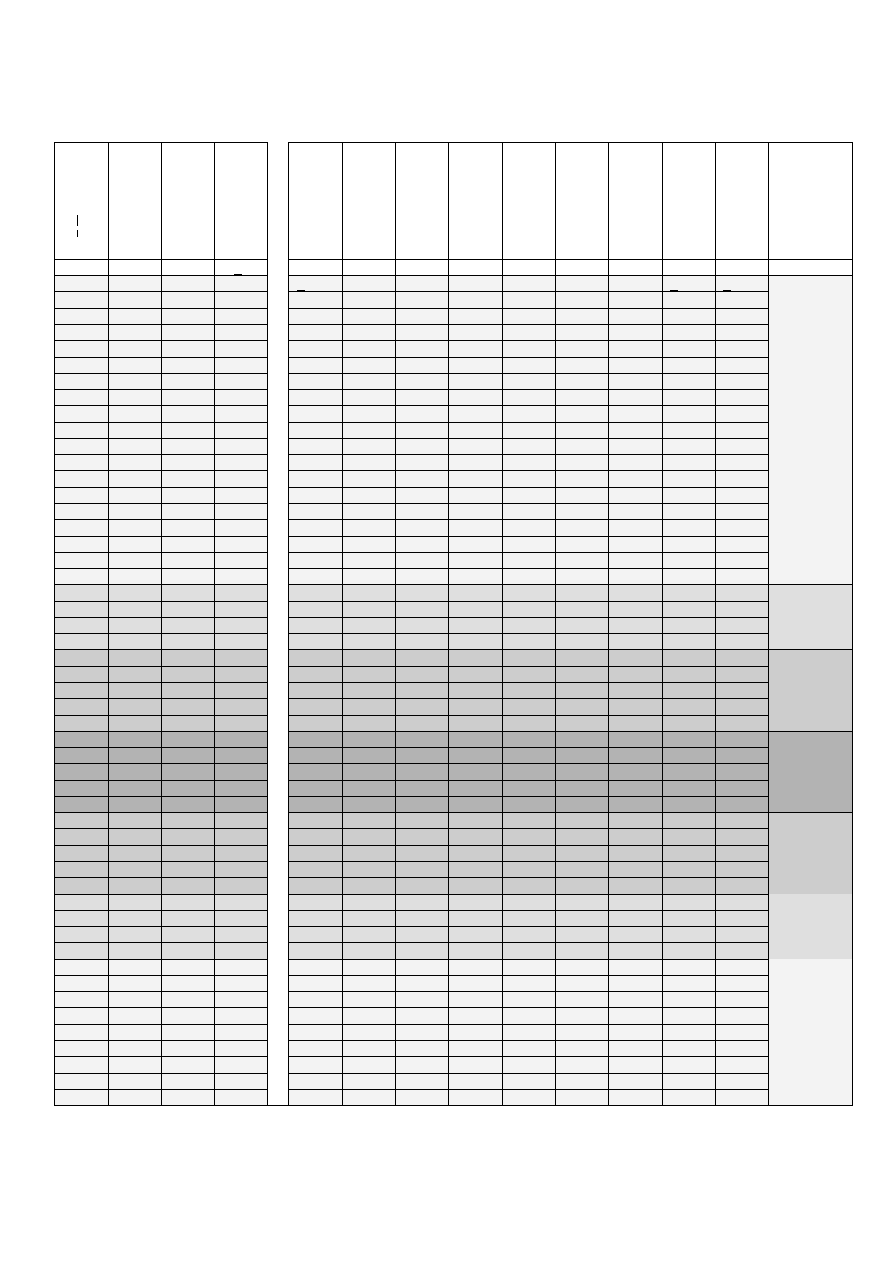

Item-rest correlations

Also, to assess the degree to which a certain item fits with the rest of the scale the item-rest

correlations were computed for the different groups (i.e. the correlations between an item and the

total score of the corresponding scale without adding the item involved). Table 4 gives an overview

of these item-rest correlations by indicating for each research population which range of item-rest

correlations has been found. Most item-total correlations turn out to be well over .40, whereas the

lowest value is not less than .35. These results confirm yet again that the scales are homogenous

and no items within the scales can be pointed at that would not fit and/or had better be removed.

18

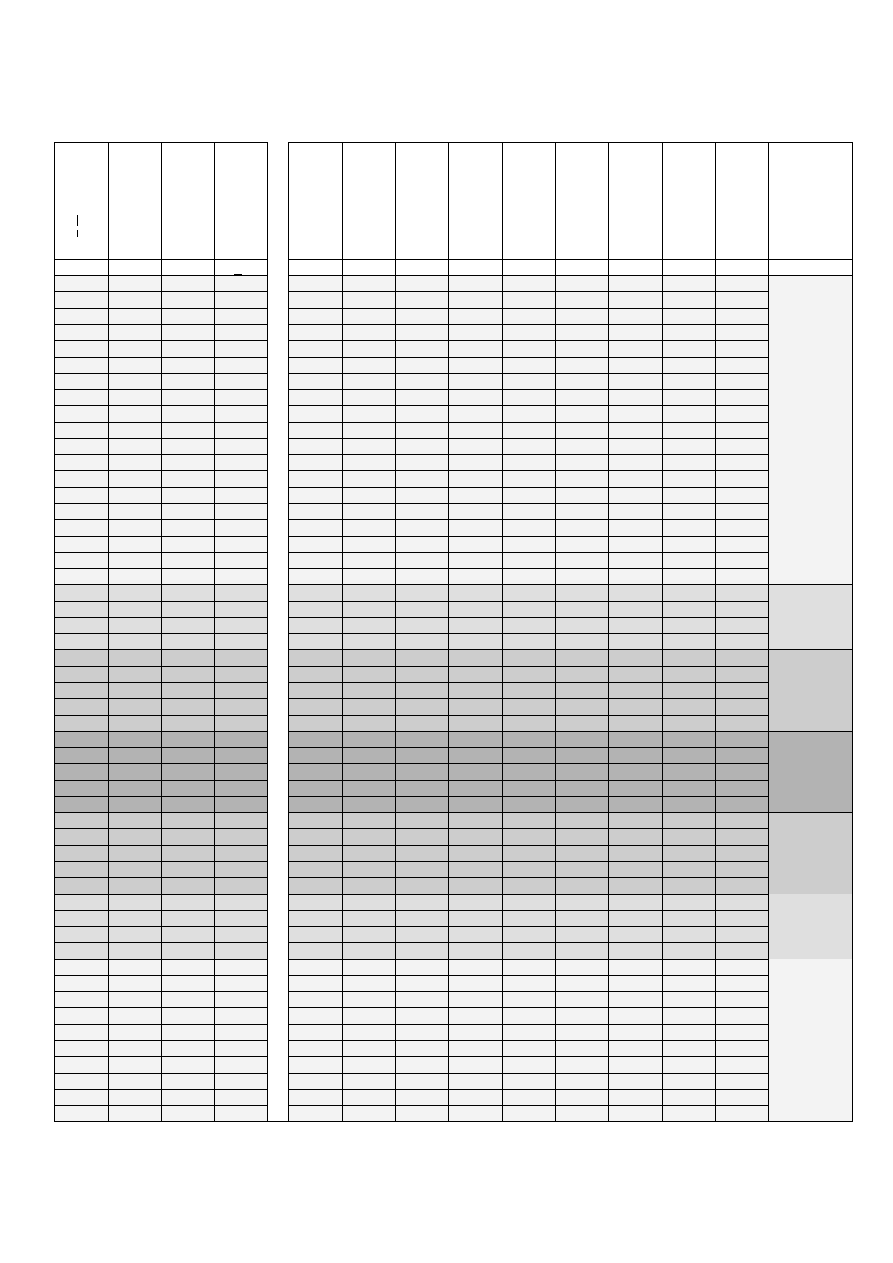

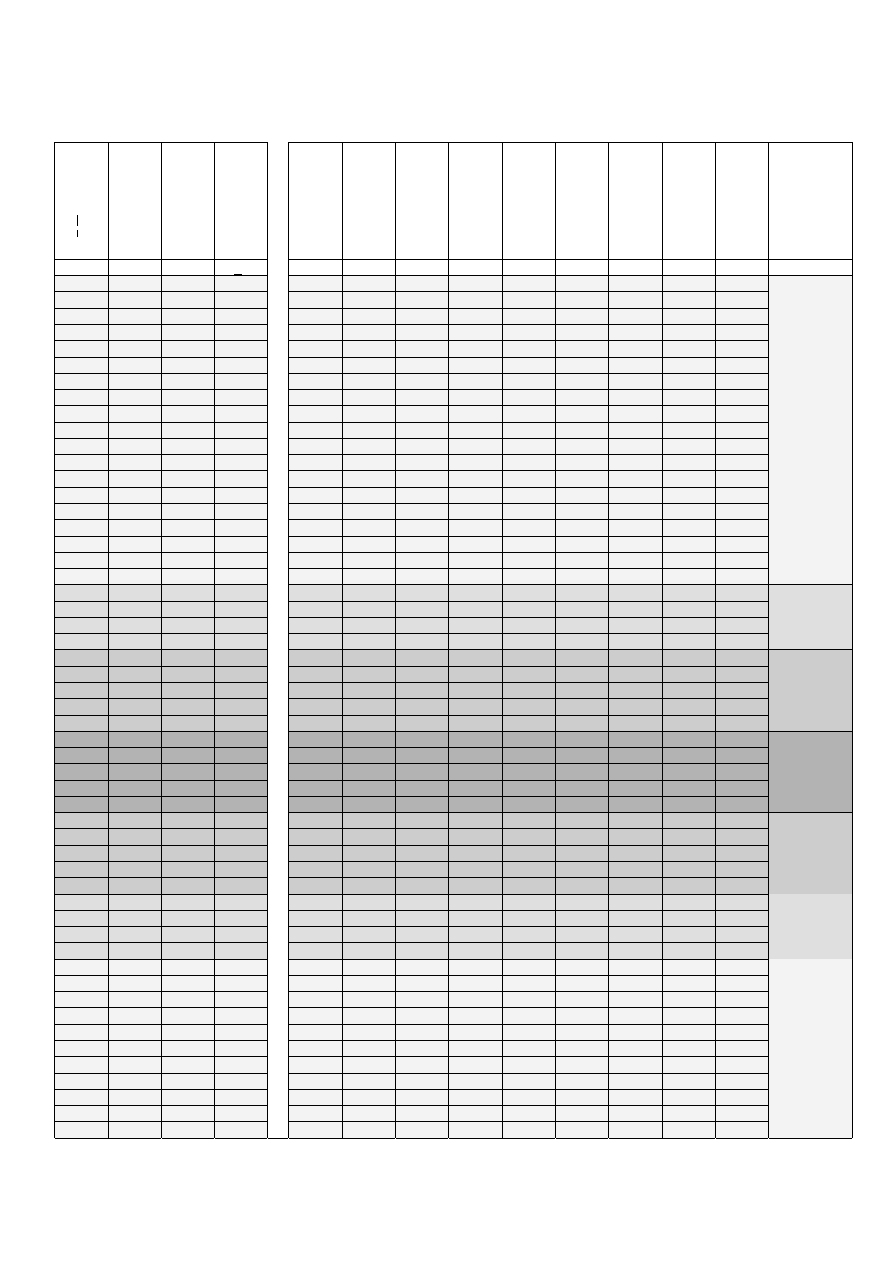

Table 3: Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the CERQ scales in five subgroups

Subscales (4 items per scale)

Early

Adolescents

Alpha

Late

Adolescents

Alpha

Adults

Alpha

Elderly

People

Alpha

Psychiatric

Patients

Alpha

Self-blame

.81

.68

.75

.77

.85

Acceptance

.80

.73

.76

.82

.72

Rumination

.83

.79

.83

.78

.81

Positive Refocusing

.81

.78

.85

.82

.81

Refocus on Planning

.81

.76

.86

.77

.84

Positive Reappraisal

.72

.76

.85

.80

.81

Putting into Perspective

.79

.76

.82

.76

.81

Catastrophizing

.71

.74

.79

.80

.80

Other-blame

.68

.73

.82

.80

.83

Table 4: Item-rest correlations of the nine CERQ scales in five subgroups (range of values)

Subscales

Early

Adolescents

Item-rest

correlation

Late

Adolescents

Item-rest

correlation

Adults

Item-rest

correlation

Elderly People

Item-rest

correlation

Psychiatric

Patients

Item-rest

correlation

Self-blame

.59-.61

.35-.53

.48-.61

.50-.70

.67-.72

Acceptance

.49-.65

.44-.62

.38-.65

.56-.66

.38-.61

Rumination

.62-.70

.57-.62

.62-.69

.57-.62

.50-.71

Positive Refocusing

.61-.65

.48-.64

.62-.72

.51-.75

.59-.65

Refocus on Planning

.61-.66

.53-.60

.67-.72

.45-.63

.63-.75

Positive Reappraisal

.47-.55

.52-.59

.65-.72

.56-.68

.60-.66

Putting into Perspective

.58-.64

.49-.59

.56-.74

.48-.66

.55-.66

Catastrophizing

.41-.58

.44-.63

.41-.71

.45-.68

.45-.65

Other-blame

.43-.52

.46-.58

.59-.71

.54-.75

.57-.74

19

Stability (test-retest reliabilities)

The CERQ was administered twice to the Adults General Population. Therefore, the data of this

group have been used to compute the test-retest correlations. There was a 14-month interval

between the two measurements. For the interpretation of the test-retest data it is, therefore,

important to take into account this relatively long intervening period of time, because it is

reasonable to assume that in such an interval a change of circumstance will occur more easily or

more often than had there been a shorter intervening period of time. Table 5 shows the results of

test-retest correlations and paired t-tests.

The test-retest correlations range between .48 (Refocus on Planning) and .65 (Other-blame). These

values suggest that we are talking about reasonably stable styles, although certainly not

comparable to personality traits. This is confirmed by the outcomes of the paired t-tests, which

test whether the mean individual difference scores of the first and second measurements deviate

significantly from zero. Without a Bonferroni correction, in a number of cases a small, though

significant, difference turned out to exist between someone's pre- and post-measurement. After

the Bonferroni correction, the correction which needs to be applied to correct for the chance of

finding accidental differences when performing multiple bivariate t-tests, the existence of a

significant difference between pre-and post-measurement appeared to hold for only one of the nine

cognitive coping strategies. When using the Bonferroni correction, the normally applicable criterion

for significance, i.e. p<.05, is divided by the number of tests carried out, namely nine. The result,

the value of .006, is then used as the criterion to define whether a p-value found is significant or

not (p<.006). This significant difference concerns the cognitive coping strategy Acceptance. The

other mean difference scores do not significantly deviate from zero after the Bonferroni correction.

These findings correspond with the expectations that hold for the concept of cognitive coping

strategies and support the assumption that although cognitive coping strategies refer to personal

coping styles, it should potentially be possible to influence, change, learn and unlearn them. This is

an important point for mental health intervention. To obtain a definite answer about the degree of

stability of cognitive coping strategies, though, more data would have to be collected in different

research groups, with shorter intervening periods between test and retest.

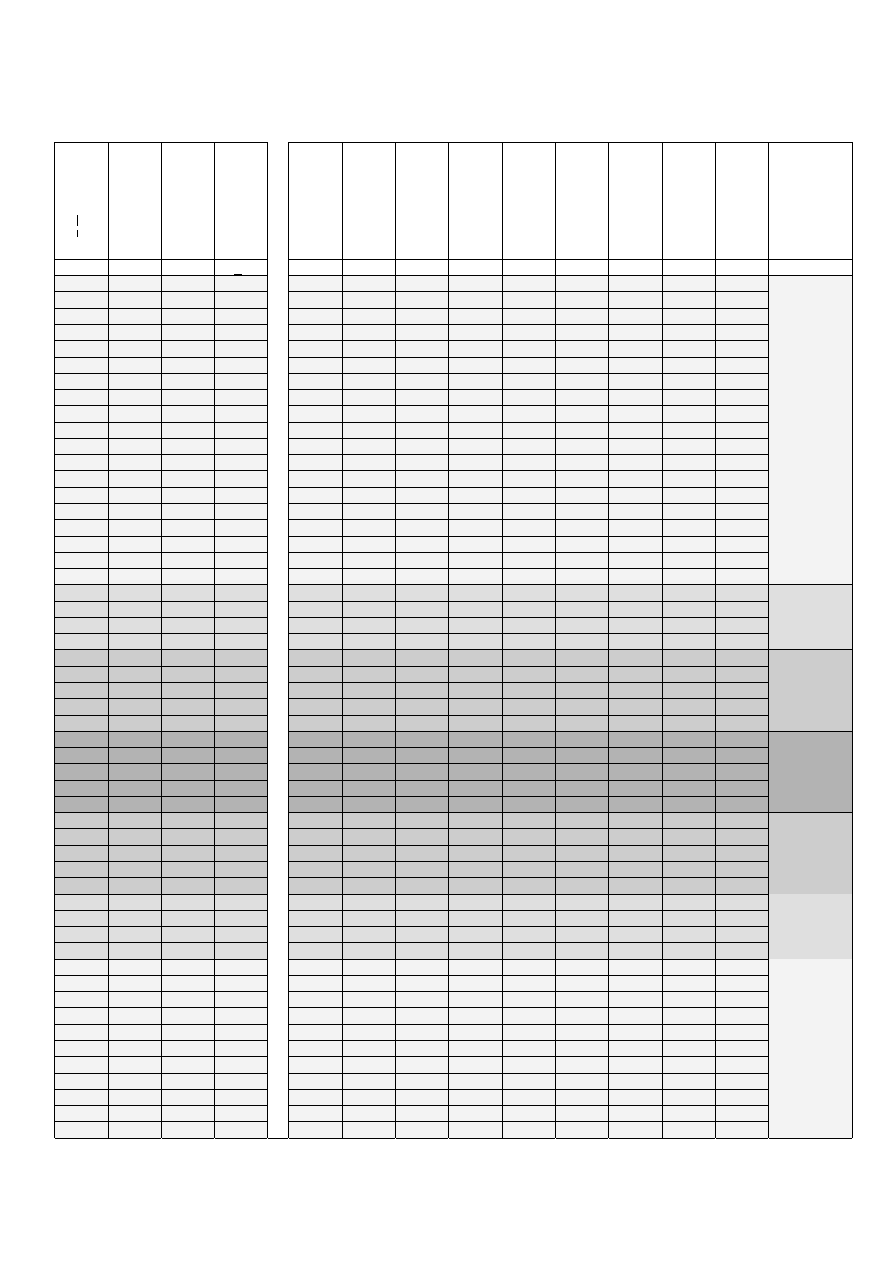

Table 5: Test-retest reliabilities of the CERQ scales after14 months (Adults General Population age 18-65 years)

Subscales

r

1-2

N

Measurement

1

M (sd)

Measurement

2

M (sd)

t-test

(paired)

Self-blame

.54***

287

8.22 (2.95)

8.61 (3.03)

-2.30*

Acceptance

.49***

287

11.03 (3.51)

10.41 (3.25)

3.06**

Rumination

.60***

287

10.50 (3.73)

10.10 (3.57)

2.06*

Positive Refocusing

.51***

285

9.91 (3.45)

9.75 (3.46)

0.77

Refocus on Planning

.48***

287

13.08 (3.87)

12.59 (3.58)

2.23*

Positive Reappraisal

.57***

287

12.45 (4.06)

12.34 (3.70)

0.52

Putting into Perspective

.55***

288

11.63 (3.90)

11.23 (3.76)

1.82

Catastrophizing

.62***

287

6.07 (2.45)

6.01 (2.49)

0.45

Other-blame

.65***

287

6.37 (2.70)

6.02 (2.39)

2.79**

*: p<.05; **: p<.01; ***: p<.001

20

Correlations between the CERQ scales

In order to examine the extent to which the nine CERQ subscales are interrelated, Pearson

correlation coefficients have been computed for all populations. Table 6 presents an overview of

the correlations between the CERQ scales for all populations studied, indicating in bold print the

highest and lowest values found respectively. Generally speaking the correlations pattern

corresponds fairly well between the five groups. Yet, on the whole the adolescent groups show

slightly higher correlations between the scales, whereas with the Elderly People and Psychiatric

Patients the scales correlate somewhat less. For the research involving the CERQ it is especially

important that on the whole correlations be not too high, i.e. not structurally exceeding .70 to .80.

Table 6 shows that generally correlations range between .30 and .70 (moderately high to

substantial). Only for the correlation between Refocus on Planning and Positive Reappraisal two

values exceeding .70 are found, but for the correlation between these two subscales, too, it holds

that the majority of coefficients does not exceed .70 (the mean correlation being .67). The table

clearly demonstrates that some scales are less strongly interrelated than others. This can be

explained by the fact that some concepts are simply more closely related than others. As

mentioned before, the strongest relation has been found between Refocus on Planning and Positive

Reappraisal. Also, relatively high correlations were discovered for the relationship between Positive

Reappraisal and Putting into Perspective (a mean correlation of .58). For the remaining

combinations of scales the mean correlation coefficient values were less than .50. In general,

therefore, it can be concluded that the intercorrelations of the CERQ scales support the CERQ's

multidimensionality.

Factorial validity

The factor analyses in the various populations have already shown that apart from a few

exceptions the factor structure was almost invariant across the various subgroups. This finding

points to factorial validity of the CERQ scales. As the different populations at the same time

represent diverse age groups, it may also be concluded that the factor structure is also almost

invariant with respect to age. In order to examine the factorial validity with respect to gender, the

whole Early Adolescents group, the whole Late Adolescents group and the whole Adults General

Population group were divided into a male and a female group. Next, the factor structures obtained

in these groups were compared. This was not done for the Elderly People group nor the Psychiatric

Patients group, because division resulted in sample groups of less than 100 which would render the

factor analysis less reliable.

The results demonstrated that the CERQ's 9-factor structure is also invariant with regard to gender.

Also, the overlap between Refocus on Planning and Positive Reappraisal was found in all groups.

The only exception was that in the Late Adolescents group some overlap between the factors of

Other-blame and Catastrophizing was found for the girls, while the boys showed some overlap

between Putting into Perspective, Planning and Positive Reappraisal. With the Early Adolescents

both for the boys and the girls 65% of the variance was explained, while for the men as well as the

women from the Adults population 69% of the variance was explained. With the Late Adolescents,

in the case of the girls 64% and the boys 62% respectively of the variance was explained.

21

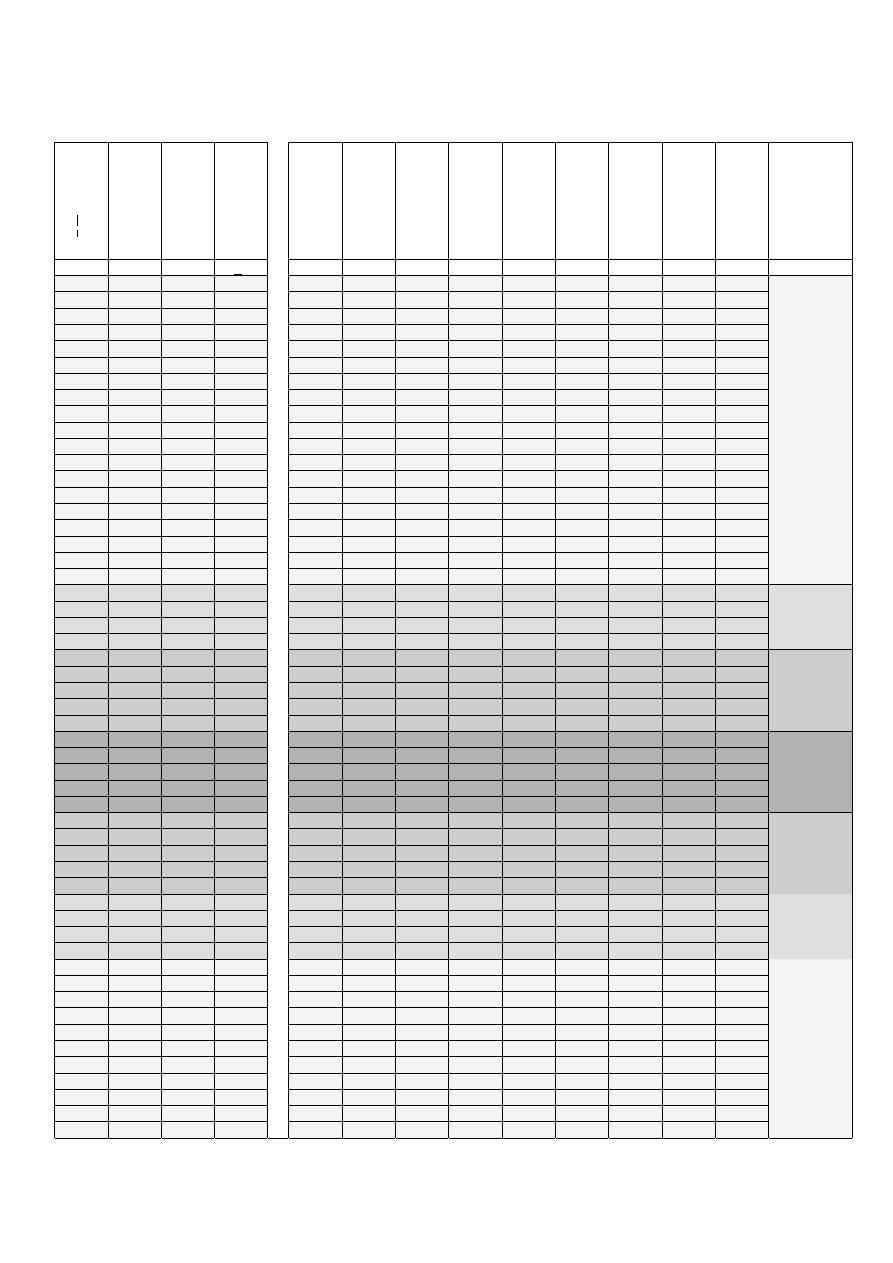

Table 6: Pearson correlations between the nine CERQ scales for five subgroups (Range of values)

Subscales

Group

1

Self

r

Acc

r

Rum

r

PRef

r

Plan

r

PosR

r

Pers

r

Cat

r

Self-blame (Self)

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5

-

Acceptance (Acc)

1

.49***

-

2

.41***

-

3

.37***

-

4

.40***

-

5

.33***

-

Rumination (Rum)

1

.55***

.57***

-

2

.46***

.56***

-

3

.41***

.38***

-

4

.31**

.55***

-

5

.34***

.34***

-

Positive Refocusing

(PRef)

1

.23***

.46***

.29***

-

2

.10**

.32***

.19***

-

3

.12**

.32***

.13**

-

4

.29**

.25*

.14

-

5

-.01

.23**

.13

-

Refocus on Planning (Plan)

1

.51***

.58***

.56***

.38***

-

2

.39***

.53***

.51***

.42***

-

3

.41***

.43***

.49***

.39***

-

4

.41***

.54***

.44***

.47***

-

5

.24**

.36***

.35***

.35***

-

Positive Reappraisal (PosR)

1

.40***

.46***

.42***

.44***

.62***

-

2

.27***

.51***

.38***

.47***

.71***

-

3

.37***

.43***

.34***

.49***

.69***

-

4

.38***

.48***

.31**

.51***

.75***

-

5

.24**

.38***

.18*

.48***

.57***

-

Putting into Perspective (Pers)

1

.42***

.53***

.41***

.49***

.49***

.52***

-

2

.33***

.46***

.25***

.44***

.52***

.65***

-

3

.32***

.40***

.14**

.52***

.46***

.61***

-

4

.46***

.47***

.30**

.37***

.55***

.58***

-

5

.36***

.38***

.11

.32***

.40***

.57***

-

Catastrophizing (Cat)

1

.33***

.36***

.52***

.22***

.30***

.22***

.17***

-

2

.38***

.27***

.48***

.07*

.21***

.12***

.06

-

3

.21***

.19***

.49***

.00

.06

-.06

-.06

-

4

-.20

.09

.44***

-.03

.00

-.11

-.16

-

5

.10

.11

.46***

-.06

-.01

-.13

-.20**

-

Other-blame

1

.32***

.35***

.39***

.30***

.40***

.38***

.29***

.42***

2

.25***

.20***

.29***

.13***

.22***

.18***

.18***

.54***

3

.09*

.18***

.33***

.04

.16***

-.01

.04

.49***

4

.00

.04

.07

.19

.28**

.28**

.17

.07

5

-.12

-.03

.29***

.03

-.01

-.08

-.06

.47***

***:p<.001; **:P<.01; *:P<.05

1

Group 1: Early Adolescents; Group 2: Late Adolescents; Group 3: Adults General Population; Group 4: Elderly People;

Group 5: Psychiatric Patients

22

Discriminative properties

In determining its validity the discriminative properties of a test are also of importance. That is,

when specific scales in specific populations are expected to show higher means, this should be

reflected in the differences between the mean scores. On the basis of the literature it is expected

for the CERQ that the Psychiatric Patients' mean scores should be higher especially on scales like

Rumination, Self-blame and Catastrophizing. Another expectation in keeping with general findings

in the literature would be that on most of the CERQ scales women should show higher mean scores

than men. Furthermore, we expect that with age the use of most cognitive strategies will also

increase. The next chapter on the standardization of the CERQ includes a table (Table 16)

representing the differences between means.

In the first place, Table 16 clearly shows that, as expected, the Psychiatric Patients score higher on

Self-blame, Rumination and Catastrophizing than the Adults of the General Population do.

Secondly, women do in fact show a higher mean score than men on most scales. Thirdly, the use of

most cognitive strategies seems to increase with age. On the other hand, with the Elderly People

the use of certain cognitive coping strategies seems to decrease somewhat. With these results,

therefore, the CERQ scales demonstrate that the discriminative properties are in agreement with

the expectations.

Construct validity

Below, the correlations between the CERQ scales and various measures considered relevant are

described, with the purpose of gaining insight into the CERQ's construct validity. The following

sections clearly show that the strongest correlations are found between a number of CERQ scales

and the scales of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS) that are related as regards

content. With respect to the correlations between the CERQ scales and other concepts it is shown

that on the whole they are in line with expectations. Moderate to fairly strong relations have been

found for a number of CERQ scales and Personality, Self Esteem and Self-Efficacy, which shows that

although related concepts are involved, the extent of their relation is not such that they can be

called the same concepts. Also, some clear relations have been found between a number of CERQ

scales and various Psychopathology indicators, which is an important finding from the point of

intervention and/or treatment.

The CERQ and the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS)

For validation purposes both in the survey among Late Adolescents and the survey among Adults

General Population the CERQ has been administered simultaneously with the Coping Inventory for

Stressful Situation (CISS: Endler & Parker, 1990). Table 7 shows the correlations between the nine

CERQ subscales and the three CISS subscales, Task-oriented Coping, Emotion-oriented Coping and

Avoidance-oriented Coping. On the whole it can be stated that the picture of the correlations found

in the Late Adolescents group matches the correlations found in the Adults General Population

group and that the correlations between the CERQ and CISS subscales can be interpreted in a

theoretically meaningful manner.

23

Table 7: Correlations between the CERQ and the CISS

Coping subscales (CISS)

Task-oriented Coping

Emotion-oriented Coping

Avoidance-oriented Coping

CERQ subscales

Late-

Adolescents

Adults

Late-

Adolescents

Adults

Late-

Adolescents

Adults

Self-blame

.37***

.24***

.54***

.39***

.12***

.15***

Acceptance

.50***

.32***

.32***

.23***

.22***

.19***

Rumination

.44***

.28***

.56***

.50***

.24***

.29***

Positive Refocusing

.27***

.35***

.06

.06

.37***

.38***

Refocus on Planning

.68***

.70***

.30***

.17***

.32***

.28***

Positive Reappraisal

.64***

.59***

.14***

-.02

.33***

.35***

Putting into Perspective

.48***

.40***

.20***

.08*

.31***

.28***

Catastrophizing

.21***

-.03

.52***

.57***

.17***

.20***

Other-blame

.22***

.13**

.38***

.47***

.16***

.13**

*:p<.05; **:p<.01; ***:p<.001

In both groups – as expected - high correlations were found between the CERQ Refocus on Planning

and Positive Reappraisal subscales on the one hand and the CISS Task-oriented Coping subscale on

the other hand. These scales all reflect the active coping with or management of the problem. Also

Acceptance and Putting into Perspective had reasonably high correlations with Task-oriented

Coping.

Also high correlations were found between CERQ subscales Self-blame, Rumination and

Catastrophizing on the one hand and the CISS Emotion-oriented Coping subscale on the other, all

referring to a certain way of being preoccupied with your emotions and in general considered less

functional strategies. In addition, Other-blame showed a reasonably high correlation with Emotion-

oriented Coping.

Less high correlations were found between the CERQ scales and the Avoidance-oriented scale. A

fairly high correlation, though, was found between Avoidance-oriented Coping and the Positive

Refocusing scale, the latter of which can of course also be considered as a sort of avoidance.

The CERQ and the NEO 5-Factor Personality Test (NEO-FFI)

In order to examine the relationship between cognitive coping strategies and personality, the CERQ

has been administered to one of the research populations, i.e. the Adults General Population,

simultaneously with the NEO-FFI. The NEO measures the five factors of personality: neuroticism,

extraversion, openness to experience, altruism and conscientiousness (Hoekstra, Ormel & de Fruyt,

1996). Not too high correlations are expected to be found between the five personality factors and

the cognitive coping strategies, because cognitive coping strategies pretend to measure something

else than personality. Some relationship is expected, though, with the Neuroticism factor, because

generally speaking this concept shows a considerable overlap with depressive complaints and/or

psychopathology symptoms. The highest correlations are indeed found between the CERQ

Rumination, Catastrophizing and Other-blame scales on the one hand and Neuroticism on the other

hand (Table 8).

24

Table 8: Correlations between the CERQ and the NEO-FFI

Personality Subscales (NEO-FFI) – Adults

CERQ subscales

Neuroticism

Extraversion

Openness

Altruism

Conscientiousness

Self-blame

.12*

-.11

.14*

-.02

-.14*

Acceptance

.12*

-.11

.07

.09

.02

Rumination

.30***

-.08

.23***

.08

-.07

Positive Refocusing

-.08

.17**

.06

.13*

.03

Refocus on Planning

-.06

.11

.29***

.17**

.12*

Positive Reappraisal

-.20**

.28***

.24***

.20**

.14*

Putting into Perspective

-.07

.13*

-.03

.15*

.09

Catastrophizing

.41***

-.18**

-.07

-.07

-.15*

Other-blame

.35***

-.19**

-.03

-.18**

-.05

*:p<.05; **:p<.01; ***:p<.001

The CERQ and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

Furthermore, the relationship between cognitive coping strategies and Self-Esteem has been

examined by administering the CERQ to the Late Adolescents group simultaneously with the

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale has one outcome

measure, in which a high score refers to a high self-esteem. Cognitive coping strategies that are

assumed to be less functional are expected to correlate negatively to the self-esteem measure,

whereas cognitive coping strategies considered to be more functional will not correlate or do so

positively. In Table 9 the correlations are represented. The results show that Self-blame,

Rumination and Catastrophizing do in fact correlate significantly and negatively with Self-Esteem,

whereas Positive Refocusing and Positive Reappraisal correlate with Self-Esteem positively and

significantly, although not very strongly.

Table 9: Correlations between the CERQ en de Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

CERQ subscales

Self-Esteem (SES) -

Late-Adolescents

Self-blame

-.31***

Acceptance

-.06

Rumination

-.24***

Positive Refocusing

.14***

Refocus on Planning

.04

Positive Reappraisal

.17***

Putting into Perspective

.07*

Catastrophizing

-.29***

Other-blame

-.14***

*:p<.05; **:p<.01; ***:p<.001

25

The CERQ and the Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale

In addition, in the Late Adolescents group the CERQ was administered simultaneously with

Schwartzer's (1993) Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. A high score on the Self-Efficacy Scale refers to

a high extent of self-efficacy. Some relationship is expected to be found between the strategies

that are considered more positive and the measure of self-efficacy, while the strategies that are

considered more negative are assumed not correlate or to correlate negatively with this measure.

As expected, the highest correlations are found for Acceptance, Positive Refocusing, Refocus on

Planning and Putting into Perspective, while the concept seems hardly or not related to the use of

the 'more negative' strategies (Table 10).

Table 10: Correlations between the CERQ and the Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale

CERQ subscales

Self-Efficacy -

Late-Adolescents

Self-blame

.01

Acceptance

.24***

Rumination

.07*

Positive Refocusing

.23***

Refocus on Planning

.32***

Positive Reappraisal

.41***

Putting into Perspective

.29***

Catastrophizing

-.10**

Other-blame

.04

*:p<.05; **:p<.01; ***:p<.001

The CERQ and Depression (SCL-90/GDS)

In all five research populations the relationship with depression has been examined. For the Early

Adolescents, Late Adolescents, Adults General Population and Psychiatric Patients this was done by

administering the CERQ simultaneously with the Depression subscale of the SCL-90 (Arrindell &

Ettema, 1986; Derogatis, 1977). Only for the Elderly People depression has been measured with the

use of the GDS (Geriatric Depression Scale: Brink, Yesavage, Heersema, Adey & Rose, 1982) instead

of the SCL-90.

Relationships in the various populations are expected to correspond more or less. It is also expected

that the less functional strategies will correlate negatively to Depression, while the more functional

strategies will show a positive correlationship. On the whole, strong relationships appear to exist

between the Self-Blame (Elderly People excepted), Rumination and Catastrophizing strategies on

the one hand and Depression on the other hand. Regarding the 'more positive' strategies the

expectation is confirmed only for Adults and Elderly People that Positive Reappraisal has a negative

relationship with the measure of depression (see Table 11).

26

The CERQ and Anxiety (SCL-90)

In four of the five research populations also the relationship with Anxiety has been examined, i.e.

in the Early Adolescents, Late Adolescents, Adults General Population and Psychiatric Patients

groups. This was done by administering the CERQ simultaneously with the SCL-90 Anxiety subscale

(Arrindell & Ettema, 1986; Derogatis, 1977). Expectations here correspond to the expectations that

apply to the relationship between cognitive coping strategies and Depression. Here too, strong

relationships in all four groups appear to exist between the Self-blame, Rumination and

Catastrophizing strategies on the one hand and Anxiety on the other (see Table 12). In addition, as

regards the 'more positive' strategies a negative relationship between Positive Reappraisal and

Anxiety is found only for the Adults (see Table 12).

Table 11: Correlations between the CERQ and the SCL-90 Depression subscale / Geriatric Depression Scale

Depression (SCL-90) / Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)

CERQ subscales

Early

Adolescents

Late

Adolescents

Adults

Elderly

People

Psychiatric

Patients

Self-blame

.49***

.41***

.26***

.01

.39***

Acceptance

.30***

.24***

.18***

.27*

.18**

Rumination

.54***

.45***

.44***

.42***

.44***

Positive Refocusing

.07

-.07*

-.07

-.15

-.10

Refocus on Planning

.28***

.12***

.01

-.01

-.01

Positive Reappraisal

.14**

-.02

-.15***

-.27*

-.06

Putting into Perspective

.22***

.03

-.09*

.07

.06

Catastrophizing

.36***

.43***

.57***

.46***

.43***

Other-blame

.16***

.23***

.33***

-.03

.28***

*:p<.05; **:p<.01; ***:p<.001

Table 12: Correlations between the CERQ and the SCL-90 Anxiety Scale

Anxiety (SCL-90)

CERQ subscales

Early

Adolescents

Late-

Adolescents

Adults

Psychiatric

Patients

Self-blame

.40***

.32***

.20***

.38***

Acceptance

.27***

.21***

.17***

.17*

Rumination

.54***

.36***

.35***

.45***

Positive Refocusing

.15***

-.02

-.02

-.08

Refocus on Planning

.29***

.13***

-.01

.06

Positive Reappraisal

.19***

.03

-.17***

.01

Putting into Perspective

.23***

.06

-.08*

.05

Catastrophizing

.26***

.38***

.54***

.45***

Other-blame

.15***

.21***

.29***

.23**

*:p<.05; **:p<.01; ***:p<.001

27

The CERQ at first measurement and Anxiety and Depression (SCL-90) at follow-up

Follow-up data have been collected from the Adults General Population. During this second

measurement the SCL-90 Depression and Anxiety scales have once again been administered

(Arrindell & Ettema, 1986; Derogatis, 1977). The correlations between the CERQ scales and the

Depression and Anxiety scores at follow-up are given in Table 13. The interval between first

measurement and follow-up amounted to 14 months. Despite this relatively long period of time a

number of CERQ subscales can very clearly predict Depression and Anxiety scores over a longer

period of time. Significantly positive relationships are found once more between Self-blame,

Rumination and Catastrophizing on the one hand and Depression and Anxiety on the other, with

Positive Reappraisal showing once more a significantly negative relationship with both SCL-90

subscales.

Table 13: Correlations between the CERQ and SCL-90 Depression and Anxiety scales at follow-up

CERQ subscales

Depression second

measurement

(SCL-90)

Adults

Anxiety second

measurement

(SCL-90)

Adults

Self-blame

.20**

.12*

Acceptance

.15*

.14*

Rumination

.28***

.27***

Positive Refocusing

-.04

-.05

Refocus on Planning

.02

-.01

Positive Reappraisal

-.13*

-.16**

Putting into Perspective

-.06

-.06

Catastrophizing

.47***

.52***

Other-blame

.32***

.33***

*:p<.05; **:p<.01; ***:p<.001

The CERQ and Hostility (SCL-90)

In two of the five research populations the relationship with hostility has also been examined,

namely in the Late Adolescents and the Psychiatric Patients groups. This has been done by

administering the CERQ simultaneously with the SCL-90 Hostility subscale (Arrindell & Ettema,

1986; Derogatis, 1977). Especially the Other-blame subscale was expected to show a correlation

with Hostility, which proved to be the case for both groups. In addition, for both groups

Catastrophizing, Self-blame, and Rumination also showed significant relationships with Hostility

(see Table 14).

The CERQ and other measures of Psychopathology (SCL-90)

The Psychiatric Patient group was the only research population to whom the whole SCL-90 was

administered (Arrindell & Ettema, 1986; Derogatis, 1977). Regarding Depression, Anxiety and

Hostility, we refer to the previous sections. The correlations between the remaining SCL-90

subscales with the CERQ are given in Table 15.

28

The picture that emerges is very clear: positive, significant relationships are found between the

CERQ Self-blame, Rumination, Catastrophizing and Other-blame scales on the one hand and the

various measures of Psychopathology on the other. There seems to be a sort of general relationship

between the use of specific cognitive strategies and various kinds of psychopathology. It is not

possible to indicate cognitive strategies that are or are not specifically related to certain forms of

psychopathology.

Table 14: Correlations between the CERQ and the SCL-90 Hostility subscale

Hostility (SCL-90)

CERQ subscales

Late-Adolescents

Psychiatric

Patients

Self-blame

.29***

.18*

Acceptance

.15***

.01

Rumination

.19***

.19**

Positive Refocusing

-.05

.02

Refocus on Planning

.09**

-.08

Positive Reappraisal

.04

-.10

Putting into Perspective

.05

-.03

Catastrophizing

.35***

.23**

Other-blame

.32***

.32***

*:p<.05; **:p<.01; ***:p<.001

Table 15: Correlations between the CERQ and the remaining SCL-90 scales

Other Psychopathology measures (SCL-90) – Psychiatric Patients

CERQ subscales

Phobic

Anxiety

Somatization

Obsession-

Compulsion

Interpersonal

Sensitivity

Sleeping

Disturbances

Global

Severity

Self-blame

.17*

.27***

.34***

.30***

.20**

.39***

Acceptance

.02

.12

.15*

.08

.13

.16*

Rumination

.28***

.34***

.43***

.40***

.30***

.47***

Positive Refocusing

-.11

-.01

.01

-.08

-.09

-.07

Refocus on Planning

-.13

.00

.05

.00

.02

.00

Positive Reappraisal

-.12

.05

.06

-.06

.05

-.02

Putting into Perspective

-.10

.03

.14*

-.01

.01

.04

Catastrophizing

.41***

.36***

.36***

.43***

.33***

.48***

Other-blame

.15*

.17*

.25***

.40***

.21**

.31***

*:p<.05; **:p<.01; ***:p<.001

29

Chapter 5

Standardization of the CERQ

Interpreting the CERQ scale scores

To all CERQ scales it applies that the higher the score on a specific subscale, the more the person

in question uses this cognitive coping strategy. Of course, in different research populations

different means and standard deviations are found. In the following section on group differences

these data of the different norm groups are represented.

Group differences: means and standard deviations of the norm groups

The means and standard deviations of the various research populations are listed in Table 16, the

data for males and females being presented separately.

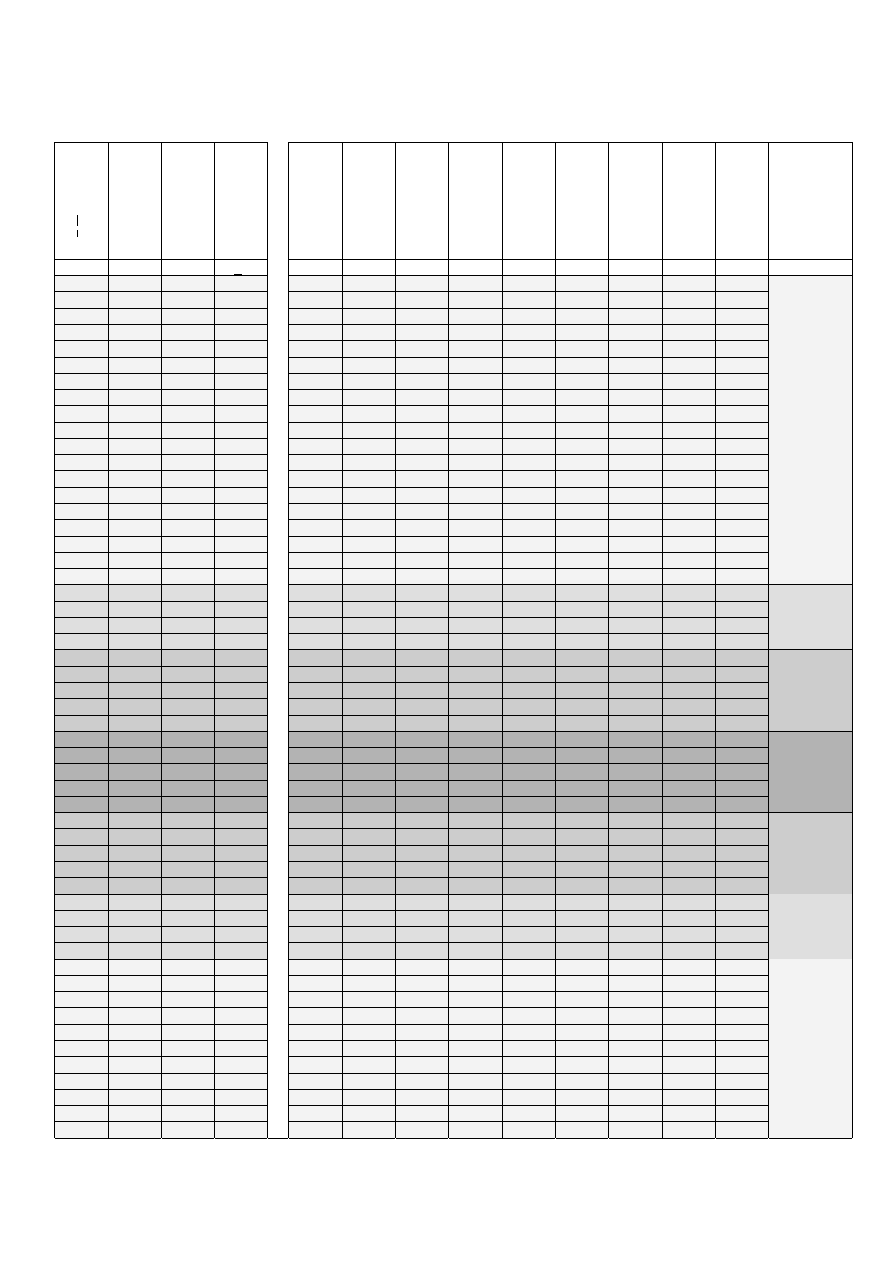

Table 16: Means and standard deviations of the five subgroups for each CERQ subscale

Subscales

Early

Adolescents

Late

Adolescents

Adults

Elderly People

Psychiatric

Patients

Males

Females

Males

Females

Males

Females

Males

Females

Males

Females

Self-blame

M

6.81

7.57

7.78

8.20

8.37

8.21

7.94

6.89

10.44

10.88

sd

2.83

2.87

2.69

2.96

2.83

3.19

2.87

3.59

4.33

4.39

Acceptance

M

8.60

9.18

9.66

10.48

10.43

10.89

11.93

12.44

11.34

11.97

sd

3.53

3.12

3.51

3.53

3.67

3.58

4.64

4.52

3.47

3.74

Rumination

M

7.11

8.83

8.34

10.26

9.49

10.80

8.81

10.13

11.95

12.90

sd

2.70

3.58

3.34

3.68

3.56

3.86

3.46

3.47

4.30

3.88

Positive Refocusing

M

8.79

9.51

10.43

11.26

9.37

10.13

11.22

11.71

9.00

9.30

sd

3.49

3.29

3.81

3.65

3.70

3.51

4.26

3.81

3.42

3.20

Refocus on Planning

M

9.13

10.01

10.92

11.46

12.76

12.92

11.93

11.49

12.79

12.24

sd

3.73

3.39

3.73

3.45

3.85

3.88

4.10

3.49

4.19

3.83

Positive Reappraisal

M

8.38

8.67

10.91

10.93

11.86

12.45

11.33

10.92

10.03

10.40

sd

0.19

2.92

3.79

3.61

4.01

4.11

4.25

3.98

4.06

3.83

Putting into Perspective

M

8.89

9.48

10.55

10.93

11.29

11.62

11.83

11.91

9.81

10.62

sd

3.69

3.08

3.66

3.66

3.81

3.92

4.00

3.63

3.53

4.04

Catastrophizing

M

5.66

5.88

6.77

6.93

5.67

6.62

6.42

7.62

8.77

8.42

sd

2.13

2.34

2.71

3.05

2.31

3.02

3.46

3.16

3.88

3.77

Other-blame

M

6.10

5.84

7.04

6.34

6.20

6.53

5.82

6.23

7.67

7.26

sd

2.11

1.96

2.81

2.51

2.50

2.93

2.71

2.86

3.50

3.15

30

Comparison between the various groups clearly shows that the mean CERQ scale values can clearly

distinguish between the diverse research populations. The general picture emerging from the table

is that on the whole Late Adolescents make more use of the diverse cognitive coping strategies

than Early Adolescents and that in turn Adults make more use of the majority of cognitive coping

strategies than Late Adolescents. Exceptions are the Positive Refocusing, Catastrophizing and

Other-blame strategies, the use of which seems to have decreased somewhat in adulthood. To both

Early and Late Adolescents it applies that females make more use of all strategies, except for

Other-blame. Although the distinction between males and females seems to decrease as they grow

older, females keep making use of the majority of strategies more often than males. This does not

hold for Self-Blame. For Adults, aged 18-to-65 years, males report this strategy more often than

females. With the Elderly People, the use of some cognitive strategies seems to decrease, whereas

others are reported more often. For instance, there is less Self-Blame and Rumination, as opposed

to more Acceptance and Positive Refocusing. Still, a difference between males and females remains

visible. With the Psychiatric Patients the gender differences seem to be smaller. Compared to the

Adults General Population norm group the Psychiatric Patients group score considerably higher on –

among other things – the Self-Blame, Rumination and Catastrophizing strategies, whereas they

make less use of the Positive Refocusing, Positive Reappraisal and Putting into Perspective

strategies.

Standardization

In order to assess whether an individual uses a specific strategy more or less often in comparison to

other people, his or her raw score will have to be compared to the mean scores of the people in the

population comparable to him or her, the so-called norm group. The five research populations, i.e.