HERMONITES

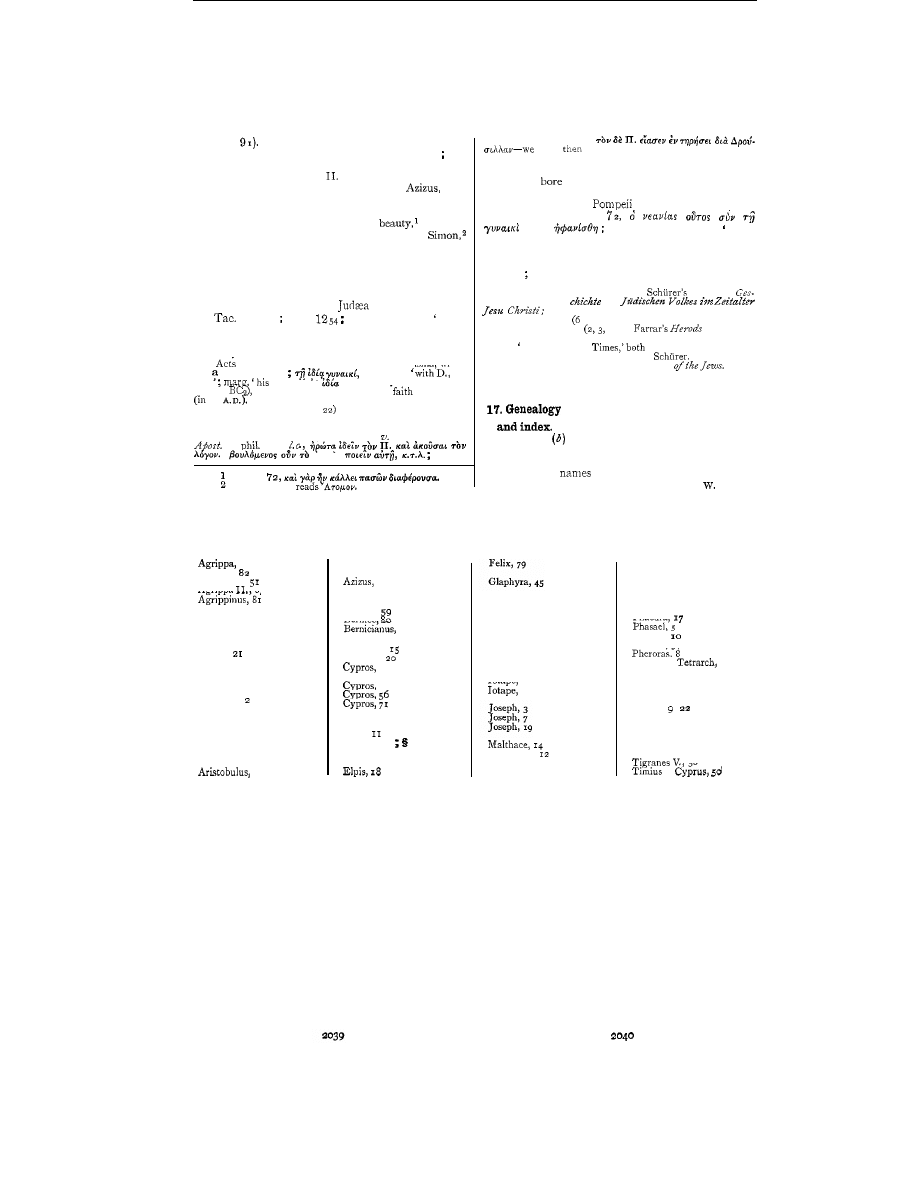

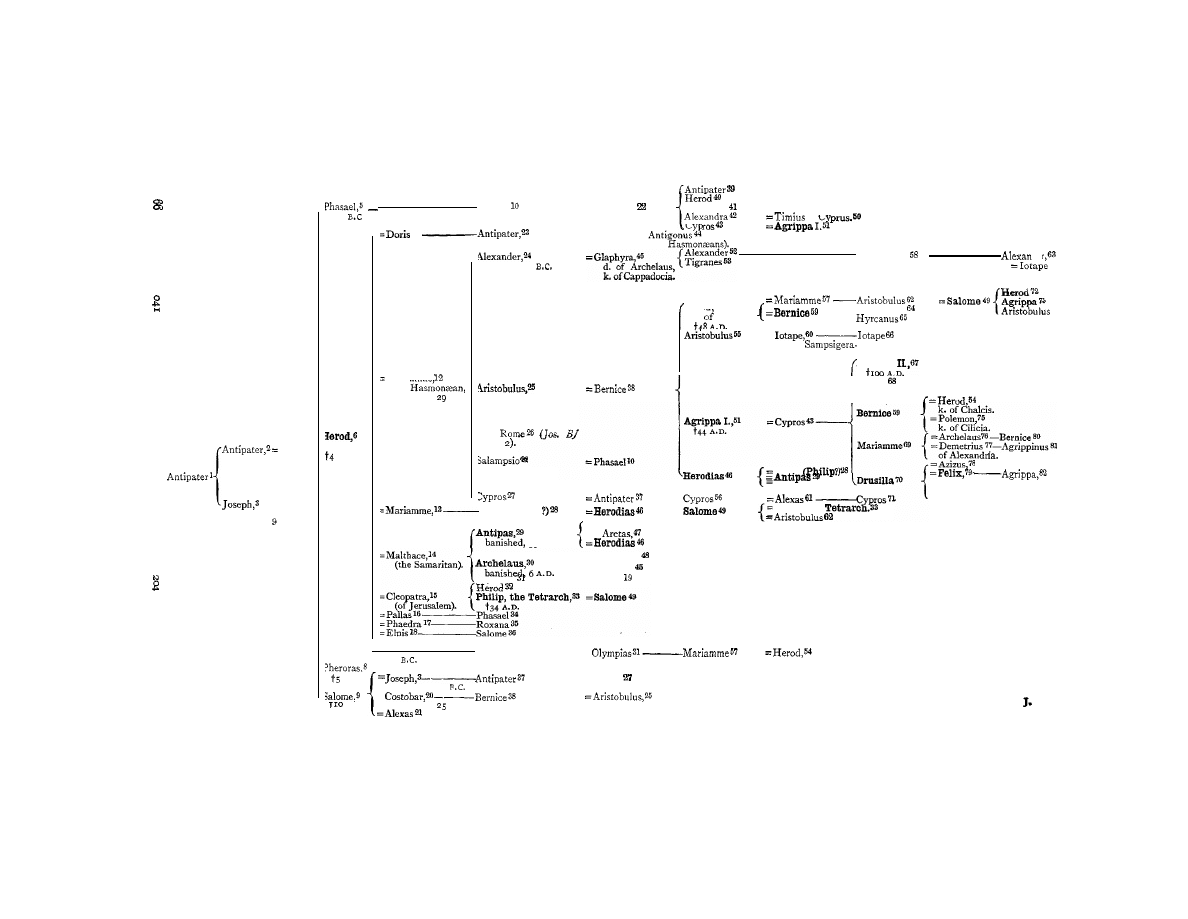

HEROD, FAMILY O F

during

a summer night will find their tent as com-

pletely saturated as if heavy rain had fallen (cp

D

E

W

,

HERMONITES

dwellers on Mt.

Hermon

(so

Ainsworth, etc.), Ps.

4 2 6

A V ;

RV 'the

the three summits of H

ERMON

See M

IZAR

.

HEROD

(FAMILY OF).

T h e ancestor of the

Herodian family was Antipater, whom Alexander

B.

c. )

had made governor

of Idumaea

Jos.

Ant. xiv.

The accounts of his

origin are contradictory.

of Damascus represented him as belonging to the

Jews

who returnedfrom Baby-

lon

(Jos.

because Nicolas was Herod's minister and

apologist Josephus rejects his testimony. His own belief

is that

Antipater was a n

of honourable family

6

;

cp

xiv. 8

I

)

.

The

had been subjugated by John Hyrcanus

in

and compelled to embrace Judaism.

In

course of time they came to regard themselves

as

ews

(Jos.

Ant. xiii. 9 ; though they were sometimes

they were only 'half-Jews'

xiv.

. . .

r e

On

'the other

when it was

Herod was

a s a Jew;

Ant.

xx. 8 7 ,

The stories

of the servile and Philistine origin of the

family, spread abroad by Jewish, and perhaps also

Christian, foes, are to be rejected

Just. Mart.

5 2 ,

Jul. Afr. in

Eus.

HE

i.

see Schiir.

Hist.

T h e occurrence of

an Antipater of Ascalon on a tombstone in Athens

and of a Herod of Ascalon on one

at

is interpreted in favour of origin

from that town by Stark

Antipater

history

of the family

with

son, himself also called Anti-

§

T.

K.

C.

-

pater, or Antipas-a diminutive form,

perhaps used to avoid ambiguity during

his father's lifetime

(so Wilcken, in

Antipatros,' no. 17).

pater the younger, who may perhaps have succeeded to

his father's governorship,' threw himself devotedly into

the cause of Hyrcanus

in his struggle against the

usurpation of the crown and high-priesthood by his

brother Aristobfilus

in 69

B.C.

This

in

which Antipater enlisted the arms of the

king

ultimately cost the

Jews their independence. T h e bold and vigorous character of

Aristobiilus augured,

in

fact a resumption of the national policy

of the Hasmonzean house,

which the

were in sympathy. T h e accession of Queen Alexandra

had marked the abandonment of this policy, and the

adoption of the

abnegation of political development.

(On this

of ideals between the two sects, see I

SR

A

E

L

Momms.

Hist.

Rome, ET 4

132

Id.

2

161.)

T h e Pharisees attempted to attain their ohjects

under the merely nominal rule of the weak Hyrcanus, and it

was among them, as well

as

among the legitimist Sadducees,

that Antipater found support (Jos.

Ant. xiv. 13).

It is unnecessary to tell at length the story

of the over-

throw of the Maccabee state, effected by Pompeius as a

part

of his policy for

organization of Syria.

The gates of Jerusalem were opened to the legions of Pompeius

b y the party of Hyrcanus; hut the national party seized the

temple-rock and bravely defended it for three months

( A n t .

xiv.

T h e final result

of the struggle was the curtailment of Jewish territory. I n con-

formity with the general policy of Rome in the

of basing

rule upon the

urban communities, Pompeius 'liberated

Jos.

A n t .

xiv.

1 3

however calls him merely

Hence

R.

2

n., wrpngly

says,

Antipater

his career a s governor of

:

un-

less we suppose the 'governorship to have been merely a vague

commission of superintendence attached to the hereditary

This was

in

the autumn of 63

R

.C.

chieftainship.

A n t . xiii. 16

For

of

'Greek' in this connection,

as

contrasted

with 'Jewish, see

Die

des

I t signifies not nationality

so

much a s

mode of organization.

2023

from the Jewish rule

all

the coast towns from Raphia to

Dora,

and

all

the non-Jewish towns of the Peraea together with

Scythopolis and Samaria. T o

all

these communal freedom was

restored, whilst in other respects they were under the rule of the

governor-of the newly-constituted province of Syria.

T h e purely Jewish portion of the Hasmonrean king-

dom was left under Hyrcanus, who was recognised as

high priest, but had neither the title nor the powers of

a king (Jos.

Ant. xx.

T h e whole country was

made tributary, paying its taxes through the governor

of Syria (id.

Ant. xiv.

4 4

i.

76).

It is clear that as a civil governor Hyrcanus was a

complete failure, succumbing,

as he did, before the first

attack

of

Alexander, son of Aristobdus.

Gabinius

therefore deprived him of all his secular powers, and

divided the whole country

Samaria, Galilee,

and Perzea) into five independent districts.

These districts

were administered by

governing colleges with an aristocratic organisation (Jos.

I

.

85,

This

in

57

The two

following years

also

marked by abortive attempts on the

part of Aristobiilus or his

son

to

recover the lost crown (see on

the position of parties

at

this time,

ET,

T h e position

of Antipater at this period is described

by Josephus

(Ant. xiv.

Josephus calls Anti ater 'governor

of

the Jews'

;

so

also

quoted by Josephus

3).

This

office was probably

in

the main concerned with finance, for the

five districts above mentioned must have been connected, not

with the administration of law merely, but also with the arrange-

ments for collecting the taxes. In any case Antipater was an

officer, not of Hyrcanus, whose power was

at

this time purely

ecclesiastical, but of

Roman governor of Syria. T h e degree

to which this was evident

in practice depended entirely upon

the attitude of Antipater towards Hyrcanus, and it was easy

for him to act as though he were merely his first minister.

Probably he owed this position to Gabinius, who

'settled the affairs

of

Jerusalem according to the wishes o f

Antipater' (Jos.

Ant. xiv. 64).

It is, therefore, an inversion of the facts when Josephus

assigns to the initiative of Hyrcanus the services of

Antipater to

Egypt in 48-7

( A n t .

There was, 'in fact,

no

alterna-

tive open, once Pompeius had fallen. An additional

reason for this policy was that in

49

had

attempted to use the defeated rival

of

Hyrcanus against

the Pompeian party in Syria. The plan was frustrated

by the poisoning of Aristobfilus even before he left

Rome, and by the execution of his son Alexander at

Antioch by the proconsul of Syria,

the father-in-law of Pompeius. Antigonus, the second

son of

still lived and had strong claims on

Caesar's gratitude.

T h e personal services

of

Antipater,

however, carried the day he fought bravely and success-

fully for Caesar at Pelusium and in the Delta.

Hyrcanus

was consequently confirmed in his high-priestly office

and appointed hereditary ethnarch of the

e . ,

he was reinstated in the political authority of which he

had been deprived by Gabinius. Antipater was made

procurator

:

not the procuratorship

of

the

imperial period, but an office delegated, in theory, by

Hyrcanus; cp Momms.

Emp.

I n addition, he was granted Roman citizenship, and

freedom from taxation

Jos.

Ant.

8

3

i. 95).

The real control of the country was in the hands of Anti-

pater (Jos.

Ant. xiv.

;

), who strengthened

his position by appointing Phasael and

Herod

(two of

his sons by Cypros, an Arabian

xiv.

7 3 )

governors

former in Jerusalem and the south, the

latter in Galilee

( A n t . xiv.

This is the first occasion

on which we hear of Herod.

He was at this time,

according to Josephus

cp

only fifteen years old.

Probably we should read

twenty-five,' for Herod was about seventy at the time

of his death

331

see Schur.

Hist.

1383

Once again before his

Antipater had an oppor-

tunity of displaying that sagacity in choosing sides, to

which he owed his success.

2024

HEROD,

FAMILY O F

and made himself master of

H e was besieged in Apameia

the Caesarians under C. Antistius

who was assisted by

troops sent by Antipater (Jos.

Ant.

I

.

Dio Cass. 47 27).

The new governor

L.

obtaihed no advantage

over

and

siege continued

result when the

assassination of Caesar, and the arrival in Syria of

Cassius

one of his. murderers changed the aspect of affairs.

Both besiegers and besieged

over

and the

republican party was for a time a t least, dominant

East.

rulers

Palestine Antipater and Herod, displayed

their zeal for the party in

the 700 talents demanded a s

the Jewish contribution to the republican war-chest

(44 B

.c.).

In the following year, after the withdrawal of Cassius,

Antipater fell

a victim to poison administered at the

instigation of a certain Malichos.

Was Malichos a

leader of the Pharisaic section anxious for a reinstatement of the

old theocratic government under Hyrcanus (so Matthews,

N T

in Palestine 106 cp Jos.

Ant.

xiv. 11

or

was he prompted merely by

(so

cp

Jos.

11 3,

and ihid. 7) ? Or, thirdly, was he a patriot who

saw in the civil war

opportunity of getting rid of Roman

dominion altogether ;

including both Antipater and [if necessary)

Hyrcanus, who were its representatives (cp Jos.

11

8,

end)?

Lastly, was Hyrcanus himself possibly privy to the murder of

Antipater ?

the

services rendered by

Herod to the cause of Cassius were rewarded

by

his

The object of the conspiracy is not clear.

appointment as

of Coele-Syria

(Jos.

11

4 )

it was typical of the man

that he should have held this

originally under the

governor,

(id.

Ant.

xiv.

Already in Galilee he had given

proof of his energy and ability, and at the same time

of

his thorough enmity to anti-Roman sentiments, by

his

capture and execution of Ezekias,

a noted brigand chief

or

patriot, who

for

long had harassed the Syrian border

(Jos.

It was not long, however,

(41

the year in which Antigonus. son of

II., was defeated by Herod) Herod performed another

the defeat

of

and Cassius at Philippi

having thrown all the East into the power of Antonius.

Partly

reason of the friendship which there had been be-

tween Antonius and Antipater in the days of Gabinius, partly

also no doubt by reason of the remarkable similarity in character

between the Roman and the

Herod had no difficulty

in securing the thorough support of Antonius. Deputation after

deputation from

Sadducaean party

Ant.

xiv.

appeared before Antonius with accusations against Phasael and

Herod ; but in vain. Hyrcanus himself was fain

t o

admit the

ability of the accused.

Antonius was only consulting the interests

of

peace

and good government in declaring both Phasael and

Herod tetrarchs (Ant.

xiv.

I n the following year (40

)

Herod experienced the

strangest vicissitudes

of

fortune. T h e Parthians were

induced by Antigonus to espouse his cause.

passed from Syria into Judaea, where the legitimists

the aristocrats, in the main Sadducees) rallied round Antigonus,

who, seeing that Hyrcanus was hound hand and foot to the

hated

was now the real representative of the

line. Hyrcanus and Phasael incautiously put them-

selves in the power of their enemies. The ears of Hyrcanus

were cut off in order to make it impossible for him ever again

to

hold the high-priesthood (Jos.

Ant.

happy in his knowledge that he had an avenger in his

who was free, dashed out his own brains.

Herod himself, too crafty to he deceived

by the

Parthians, had made his escape eastwards with his

mother Cypros, his sister Salome, and Mariamme, to

whom he was betrothed

Mariamme was also accom-

panied by her mother, Alexandra. These Herod de-

posited for safety in the strong castle of Masada by the

Dead Sea (Ant.

xiv.

1 3 9 ) .

H e himself made his way

with

difficulty to Alexandria, and at length arrived at

Rome, where he was welcomed both by Antonius and

by Octavian. Within a week he was declared king of

by the Senate his restoration indeed was to the

interest of the Romans, seeing that Antigonus had

allied himself with the Parthian enemy.

P. Ventidius, the legate

of

Antonius in Syria, succeeded

in expelling the Parthians from Syria and Palestine

(Dio

For a n earlier notice see above,

end.

Phasael

HEROD, FAMILY O F

Cass.

;

but neither he nor his subordinate Silo

gave Herod real help in regaining Jerusalem.

Herod was in fact compelled to rest content for this year (39

with the seizure

Joppa, the raising of the blockade of

Masada and the extermination of the robbers

patriots) of

Galilee

their almost inaccessible caverns of

in

the

see

I

).

Next year he joined

Antonius,

king of Commagene, in

Samosata, probably with the object of securing more effectual

assistance. At Daphne (Antioch), on his homeward journey, he

received

of the defection of Galilee, and the complete de-

feat and death of his brother Joseph a t the hands of Antigonus

It was not until the following year that the fall

of

Samosata enabled Antonius to reinforce Herod before

Jerusalem with the bulk of his army under C.

the new governor of Syria

(37

B

.c.).

Herod chose

this moment for the celebration of his marriage with

Mariamme, to whom he had been betrothed for the

past five years

( A n t .

xiv.

1514).

The ceremony toolc

place at

This central district of Palestine

remained loyal

to

Herod throughout these troublous

years, and a large part of his forces was recruited there-

from.

After a three months' siege Antigonus surrendered,

and was carried in chains to Antioch, where, by Herod's

Antonius had him beheaded

first king, we

are told,

to

he

so dealt with by the Romans (Jos. Ant.

xv.

Ant.

36).

This was the end of the

dynasty, and from this year dates Herod's

reign

(37

B

.

C

.

).

Herod's reign is generally divided into three

(

I

)

37-25

in which his power was consolidated

;

B.C.,

the period of prosperity

( 3 )

B

.c.,

the period of domestic

.

i.

The

During the early years of his reign Herod had to con-

tend with several enemies.

I t is true that the immediate execution of forty-five of the

most

wealthy and prominent of the Sanhedrin-;.e.,

of the

Sadducaean aristocracy, which favoured Antigonus (Jos. A n t .

9 4 ,

cp id.

xv.

the active

resistance of the rival house, whilst

confiscation of their

property filled the new king's coffers.

With the Pharisaic party resistance was of a more

passive nature; but the leaders

of

even the more

moderate section,

and

in advising the

surrender of Jerusalem, could only speak of

dominion

as a judgment of God, to which the people must submit.

Opposition on the part of the surviving members

of the

Hasmonrean house never ceased its mainspring

Alexandra, Herod's mother-in-law, who found an ally

in Cleopatra

of

Egypt.

The enmity of Cleopatra was

possibly due simply to pique

end). Hyrcanus,

who had been set at liberty, and was held in great

honour by the Babylonian Jews, was invited by Herod

to return to Jerusalem, and, on his arrival, was treated

with all respect by the

As Hyrcanus could no longer hold the high-priesthood (Lev.

21

a n obscure Babylonian Jew of priestly family

was selected for the post, which he occupied for a time ; but thk

machinations of Alexandra soon compelled Herod to depose

him in favour of

son of Alexandra (35

B

.c.).

T h e acclamations of the populace, when the young Hasmonrean

prince (he was

seventeen years of age) officiated a t the

Feast of Tabernacles, warned Herod that he had escaped one

danger only to incur a greater.

Shortlyafterwards Aristobfilus was drowned by Herod's

orders in the bath at Jericho.

Cleopatra constituted a real danger for Herod during

the first six years

of his reign, owing to her boundless

rapacity and her strange influence over Antonius.

In

34

B

.

C

.

she induced Antonius

to

bestow upon her the

whole of

(with the exception

of

Tyre and

Mariamme was Herod's second wife. H i s first wife

was

Doris

Ant.

xiv. 12

I

12

22

I

). By

her he had one

2026

HEROD,

FAMILY O F

Sidon), part of the Arabian territory (for the revenue of

which Herod was held responsible), and the valuable

district of Jericho (which Herod was compelled to take

in lease from the queen, for

talents yearly;

185). Loyalty, combined with prudence, enabled the

harassed king to resist the fascinations of the Egyptian

enchantress when she passed through

(Ant. xv.

When the Roman Senate declared war against

Antonius and Cleopatra, it was Herod's good fortune

not to be compelled to champion the failing cause.

In

obedience to the wishes of Cleopatra herself, he was

engaged in

a war with the Arabian king Malchus for no

nobler cause than the queen's arrears of tribute.

On

the news of Octavian's victory a t Actium (and Sept.

31

B.

C.

he passed over a t once to the victorious side (Jos.

Ant. xv.

6

7

Dio Cass.

51

7).

H e did not venture to

appear before Octavian until he had removed the aged

Hyrcanus on

a feeble charge of conspiracy with Malchus

the Arabian

(Ant.

63).

T h e interview upon which

his fate depended took place a t Rhodes.

Herod accurately gauged the character of Octavian and

frankly confessing his past loyalty

to

Antonius,

left

'it

to

Octavian

to

say

whether he should serve him

as

faithfully. It

should not be forgotten that Herod and Octavian

were

no

strangers

to

each other, and

that

no one was better able

to

estimate

the necessities of Herod's position during the past few

years than Octavian

;

probably Herod was in less danger than

i s

sometimes imagined.

T h e result was that Octavian confirmed Herods royal

title

;

and, after the suicide of Antonius and Cleopatra,

restored to him all the territory

of

which the queen had

deprived him, together with the cities of

Hippos,

Samaria,

Anthedon, Joppa, and Strata's Tower.

T h e 400 Celts who had formed Cleopatra's guard were

also given to him

i. 20

These external successes

were counterbalanced by domestic troubles.

These troubleshad their origin

in

the eternal breach between

Mariamme and her mother

on

the

one

side, and Herod's

own

mother and sister on the other. The contempt

of

was

returned with hatred by the

Salome. The

machinations

of

the

latter

bore fruit

when

in

a

paroxysm

of

anger and jealousy Herod ordered

Mariamme to

execution.

Renewed conspiracy soon brought her vile mother also

to

her

doom

B

.c.).

The extermination of the Hasmonaean family was

completed by the execution of Costobar, Salome's

second husband.

Salome's

first

husband Joseph had been put

to

death

in 34

B.C.

Costobar,

as

governor of Idumaea, had

given

asylum

to

the sons

of

Baba, a

scion of

the

rival house

;

these

also were

executed

and thus the

last

male

representatives of the

were swept from Herod's path

(25

B

.c.).

The

period

25-13

Secure a t last from external and internal foes, Herod

was free for the next twelve years to carry out his

programme of development.

H e was governing for

the Romans

a

part of the empire, and he was bound t o

spread western customs and language and civilisation

among his subjects, and fit them for their position in

the Roman world.

Above all, the prime requirement

was that he must maintain peace and order

;

the

Romans knew well that no civilising process could go

so long as disorder and disturbance and insecurity

remained in the country.

Herod's duty was to keep the

peace and naturalise the Graeco-Roman civilisation in

Palestine (Rams.

Christ

ut Bethlehem

T h e great buildings were the most obvious fruit of

period.

Tower was entirely rebuilt

21

and furnished

a

splendid harbour (see

I

)

.

Samaria

also was

rebuilt and renamed Sebastb (Strabo

760).

Both these

a

temple

of

Augustus,

showed his zeal

for

empire by similar foundations in other cities, outside the limits

of

(Jos.

xv.95).

Connected with this

was

the

.establishment of games, celebrated every fourth year,

in

of the Emperor

16 5

I

..

.

.

at Caesarea;

id.

xv.

8

I

also

at

Jerusalem,

With this went, of course, the erection of the necessary

buildings (theatre, amphitheatre, and hippodrome at Jerusalem,

thesameat Jericho, Anf.xvii.635;

Cp Suet.

59

on the games and the

urbes'

by the 'reges amici atque socii.'

HEROD,

FAMILY O F

i.338; at

xv.

The games were necessarily

after

the Greek model. Even in

the

time

of the

Hellenism

in

this form had infected

Macc.

114) :

see

H

ELLENISM

.

The defensive system of the country was highly

developed, by the erection of new fortresses, or the re-

building of dismantled Hasmonaean strongholds. Some

of

these fortresses were destined to give the Romans much

trouble in the great war

64,

vii.

They

were designed by Herod for the suppression of brigandage

(a

standing evil) and the defence of the frontier against

the roving tribes of the desert

(Ant. xvi.

So success-

ful was he in fulfilling this primary requirement, that in

23

B.C.

Augustus put under his administration the

districts of Trachonitis, Auranitis, and

in-

habited by nomad robber-tribes, which the neighbouring

tetrarch Zenodorus had failed to keep in order

204

Strabo 756,

In

on the death of Zenodorus,

Herod was given his tetrarchy, the regions of

and Panias ( A n t . xv.

cp Dio Cass.

549) and he

obtained permission to appoint his brother

tetrarch of

On Herod's work cp Momms.

Prov.

of

Emp.

Much might be said

of

Herod's munificence both to

his own subjects and far beyond the limits of his

The Syrian Antioch

Ant.

53)

the cities

of

Chios

and Rhodes,

the new

foundation

of

in

Epirus, and

many

others, experienced Herod's

liberality.

The

Athenians and

counted

him

among their bene-

factors

21

I

T

;

cp

The

ancient

festival at

Olympia recovered something

of

its

old glory through

his

munificence

( A n t . xvi. 53). At

home,

in

B.c.,

he

remitted

one-third of the taxes

xv.

and

in

B

.C.

one-fourth

( A n t .

In

25

B

.C.

he had converted into coin

even

his

own

plate

in

order

to

relieve

the sufferers from famine

im-

porting

corn

from

Egypt

(Ant.

xv.

T h e greatest benefit of

all, however, in the eyes

of

Jews must have been his restoration of the Temple,

a

work which was carried

out

with the nicest regard for

the religious scruples of the nation

(Ant. xv.

116).

Begun in

B.

it was not entirely finished until the

time of the Procurator

(62-64

A.

D

.),

a

few

years before its total destruction (cp

Jn.

Its

beauty and magnificence were proverbial (cp Mt. 241

Mk.

Lk.

iii.

Period

of

domestic troubles,

last

nine years of Herod's life were marked in

a special

degree by domestic miseries. Of his ten wives (enumer-

ated

Jos.

Ant. xvii.

1 3

the first, Doris (col.

2026

n.

I

),

had been repudiated, along with her

son

Antipater

By his marriage with

Herod had hoped to give his position

a certain legitimacy.

Mariamme's mother, Alexandra, was thedaughter of Hyrcanus

II.,

whilst

her father, Alexander, was a

son of

(brother of Hyrcanus)

: consequently

Mariamme represented

the direct line of the

family.

The political intrigues of Mariamme's mother, and

the mutual enmity of Mariamme and Herods mother

(Cypros) and sister (Salome), effeetually frustrated these

hopes.

Of the three sons borne to Herod by

the youngest died in Rome

but

Alexander and

were fated to

on the

gibbet a t that very

which, thirty years before,

had seen Herods marriage with their mother.

Salome had

in

the second

also

a

large share,

standing the fact that Berenice, the wife of

was

her

own

Costobar, see above, end). The recall

of

the banished-Antipater, son

of

Doris, brought

a

more deadly

in-

triguer upon

the scene

(14

;

i.

23

I

). Under the combined

attack of Antipater and Salome, the two sons of Mariamme

incurred

the

of

the

The

reconciliation effected

by

Augustus

( A n t .

xvi.

in

B

.c.) at

and

two

years later

Archelaus, the Cappadocian king

(Ant.

xvi.

had

no

long continuance. The elements of discord and

intrigue were reinforced by

the arrival at

Herod's

court

of

the

Lacedmmonian adventurer Eurykles

26

The brothers

were

again accused of treason,

and

Augustus gave leave

to

Herod

The

wife

of Alexander

was

Glaphyra, daughter of Archelaus,

Glaphyra and Berenice were

also

on

king

of

Cappadocia.

terms of bitterest enmity

2028

HEROD,

FAMILY O F

t o

deal with them as he saw fit. They were tried at Berytus

before

C.

Saturninus, the governor of Syria

i. 27

and condemned to death. T h e execution took place a t

Antipater, whose life, says Josephus, was a mystery

iniquity'

next plotted with

to

remove the king by poison. Herods days, indeed,

were already numbered,

as he was afflicted with a

painful and loathsome disease

335).

He lived

long enough, however, to summon the arch-plotter

from Italy, and to bring him to trial before Quinctilius

Varus, then governor

of Syria, and finally to re-

ceive the emperor's permission

his execution

i.

Herod is said to have contemplated the wholesale massacre of

the chief men of Judaea, in the hippodrome of Jericho, in order

his funeral might be accompanied by the genuine lamenta-

tions of the people but Salome released them during his last

days

xvii.

We may reasonably doubt whether Jewish

tradition has not intensified the colours in which the closing

scenes of the hated king's life are painted

(Ant.

xvii. 8

I

).

Herod died in

4

five days after the execution

of

Antipater.

There is probably no royal

of any

age in which bloody feuds raged in an equal degree

between parents and children, between husbands and

wives, and between brothers and sisters' (Momms.

Prov.

Rom.

We cannot here discuss the question whether Herod

is rightly called the Great.

Certainly it is

not

easy

to

be strictly fair towards him but so much must be clear,

that, judged. by the standard of material benefits con-

ferred, few princes have less reason

to

shrink from the

test.

I n addition to the benefits of

his

rule at home,

-there were gains for the Jews of the Dispersion in Asia

Minor. By his personal influence with Agrippa, he

.obtained safety for their Temple contributions, exemption

from military service, and other privileges (Jos.

Ant.

xvi.

In estimating these services, Herod's posi-

tion in the imperial system must

Herod was only one of a large number of allied kings

socii),

whose use even of the royal title was dependent upon the

goodwill of the emperor and their exercise of royal authority no

less

In the most

case, their sovereign rights

were strictly limited within the boundaries of their own land

so

that a foreign policy was impossible. The right of

money was limited and as, of the Herodian line, only copper

coins are known, we must correct the impression of Herod's im-

portance derived from many of the statements of Josephus.

T h e fact that no tribute was imposed, at least upon

made

all

the more imperative Herod's obligations in respect of

.frontier defence and internal good government.

The-connection

of Herod the Great with the

N T is

Both Mt.

1211 and Lk.

that the

birth of Jesus took place during his reign

but the additional information given by

Lk.

as

to the date has caused serious

difficulties (see C

HRONOLOGY

,

On the narra-

tive

of the Massacre of the Innocents, see N

ATIVITY

.

As

a rex socius, indeed,

be could not bequeath his kingdom without the consent

Herod made several wills.

of

Rome.

It- had been, therefore,

a

distinct

of favour that, on his visit

to

Rome to accuse Alexander and

he had been given leave by Augustus to dispose

Antipater's wife was the daughter of Antigonus, the last

of

the Hasmonaean kings

(Ant.

xvii. 52).

Josephus, in fact uses the title only once

(Ant.

xviii. 5

4,

I

S

. . .

Further

oh

we

Com-

parison with the expression

in

Ant.

xviii.

4

has

suggested that Jos. meant by the title

merely 'elder,'

marking himashead of the dynasty. Similarly it is in this

that it is applied to Agrippa

I . (Ant.

xvii.

. . .

but Agrippa claimed the

title in the other sense

his coins with the legend

as

I t

therefore not impossible that Jos.

abstained from giving the title, even though it was

popularly in use with reference to the first Herod. The verdict

that he was still only a common man' (Hitzig, quoted by Schiir.

Hist.

1467)

scarcely does justice to one who for thirty-four years

combated the combined hatred of

and Pharisees

and extended his frontier to the widest limit ever dreamed

hy Solomon.

Cp Jos.

Ant.

xv.

where Herod recognises that he

has

his kingdom

2029

HEROD,

FAMILY

O F

of his kingdom as he saw fit

(Ant.

xvi.

4 5 ) :

apparently

it was only on the express command of the emperor

that he refrained then from abdication.

On

his return to Jerusalem he announced to the people

assembled

the temple that his sons should succeed him-firs;

Antipater, and then Alexander and

The first

formal testament did in fact' designate Antipater

heir. but

as

the sons of

then dead, Herod, the son

high priest's daughter, was to succeed in the event of Antipater's

dying before the king

xvii. 32). After Antipater's disgrace

a

second will was made, bequeathing the kingdom to his youngest

son Antipas

(Ant.

xvii. 6

I

)

.

This was in its turn revoked by a

will drawn up in his last hours, by which he divided his realm

among three of his sons

:

Archelaus, to whom he left Judaea

with the title of king; Antipas, to whom he gave

Peraea, with the title of tetrarch and Philip, to whom he

gave the

N E

districts, also with the title of

(Ant.

xvii.

8

I ) .

Herod

[WH])

6

T

U

-

[Ti.

Mt. 141 Lk. 3 1

9 7

Acts 131

:

in.

correctly called 'king' in Mk. 6

14

7.

Antipas.

[Ti. WH]

14 o

cp Mk. 6

Sometimes

called simply Herod (Acts 4

27)

.

as

often by Josephus who also

calls

him Antipas

abbreviated form'of

Son of Herod the Great by the Samaritan

consequently full brother of Archelaus (Jos.

Ant. xvii.

By Herod's last will he received the prosperous

regions of Galilee and

with the title of tetrarch.

The confederation

of independent Graeco-Roman com-

munities called the Decapolis lay between the two parts

of his territory which brought in an annual revenue

of

two hundred talents (Ant.

xvii.

He had the char-

acteristically Herodian passion for building.

I n Galilee

he rebuilt Sepphoris (Ant.

xviii.

and in

aramptha

(see B

ETH

-

HARAN

)

;

and after

26

A.

D

.

he

created the splendid capital named by him

[g.

Little is told

us of the course of his long reign

(4

A . D . ) .

W e may believe that he was a

successful ruler and administrator

;

but the diplomacy

which distinguished Herod the Great became something

far less admirable in Antipas,

as

we may

see

from the

contemptuous expression

of the tetrarch

by Jesus

in Lk.

' G o ye, and tell that fox.'

Perhaps, however, this utterance should be restricted to the

particular occasion that called it forth and should not be

regarded as an epitome of the

character nevertheless

we have an illustration of this trait in the story

by Josephus

(Ant.

xviii. 45) of his

in forwarding

the report of the treaty with the Parthian king Artabanus to

Tiberius. Antipas certainly did not inherit his father's qualities

as

a

leader in war.

Perhaps it was consciousness

of his weakness in this

respect that prompted Antipas to seek the hand of the

daughter of the Arabian king Aretas

;

or he may have

been urged to the alliance by Augustus,

in

obedience to

the principle enunciated with reference to the inter-

marriage of reges socii by Suetonius (Aug.

48).

T h e connection with Herodias, wife of his half-brother

Herod

(son

of

the second Mariamme), gained Antipas

his notoriety

in evangelic tradition.

The flight of the

daughter of Aretas to her father involved him ultimately

in hostilities with the Arabians, in which the

was severely defeated-a divine punishment in the eyes

of .many, for his murder of John the Baptist (Ant.

xviii.

5

There was apparently

no

need for Antipas

to divorce his first wife in order to marry Herodias

but Herodias perhaps refused to tolerate

a possible

rival (Ant. xviii.

5

cp Ant. xvii.

The story of the connection of J

OHN

THE

B

APTIST

with the court of Antipas need not be repeated

here.

Later, the Pharisees warn Jesus that the tetrarch

seeks his life

( L k .

13

On the phrase the leaven

of Herod

(Mk.

8

15)

see H

ERODIANS

.

Again in the

Herod Antipas is the only Herod who bore the title

of tetrarch, we must refer to him an inscription on the island of

Cos

(CZG

and another on the island of

3

365

but nothing is known about his

connection with those places.

According to the Mishna

eighteen wives were

allowed to the king (see

quoteh by Schiir.

Hist.

1455

2030

HEROD,

F A M I L Y O F

closing scene in the life

of Jesus we meet with Antipas.

we are told by Lk.

sent

Jesus

to the

tetrarch ‘as soon as he knew that he belonged unto

Herod‘s jurisdiction.

The death of his firm friend Tiberius, and the

accession of Gaius (Caligula), in

37

A.

led to the fall

of Antipas.

T h e advancement of Agrippa

I.

to the position of king over

Philip’s old tetrarchy by the new emperor was galling to his

sister Herodias ; and against his better judgment Antipas was

prevailed upon by her to g o to Rome to sue for the royal title.

T h e interview with Gaius took place a t

Agrippa

meanwhile had sent on his freedman Fortunatus with a document

accusing Antipas of having been in treasonable correspondence

not

only with Seianus (who had been executed in

31

A

.D.),

also

with the Parthian kine Artabanus.

could not. in

fact, deny that his magazines contained a great accumulation of

arms (probably in view of his war with the Arabians).

T h e deposition and banishment of Antipas, how-

ever, were

in all probability due as much to the

caprice of the mad emperor

as to real suspicions of

disloyalty.

His place of banishment was Lugdunum

(Lyons)

in Gaul

(Jos.

A n t . xviii.

according to

96,

he died in

and it has been suggested that his place of exile was actually

Lugdunum Convenarum, a t the northern foot of the Pyrenees,

near the sources of the Garonne; but this will not save the

statement of Josephus.

A confused remark of Dio Cassius (59

seems to imply that he was put to death by Caligula.

Mt.

Herod the Great by

and

elder brother of Antipas

33

7).

Antipas

a claim for

3.

Herod

[Ti. W H ] :

crown against him before Augustus,

on the ground

that he had been himself named sole heir in the will

drawn up when Herod was under the influence of the

accusations made by Antipater against Archelaus and

Philip (see

6).

The majority of the people, under

the influence of the orthodox (the Pharisees), seized the

opportunity afforded by Herod‘s death to attempt to

re-establish the sacerdotal government under the Roman

protectorate.

Herod was scarcely buried before the

masses in Jerusalem gathered with the demand for the

deposition of the‘high-priest nominated by him, and for

the ejection of foreigners from the city, where the

Passover was just about to be celebrated. Archelaus

was under the necessity of sending his troops among

the rioters.

A deputation of fifty persons was sent to

Rome requesting the abolition of the monarchy.

To

Rome also went Archelaus claiming the kingdom-a

journey which probably suggested the framework of the

parable in

Lk. 19

Augustus practically confirmed

Herod’s last will, and assigned to Archelaus

proper, with Samaria and Idumaea, including the cities

of

Samaria, Joppa, and Jerusalem; but the

royal title was withheld, at least until he should have

shown that he deserved it (Jos.

Ant. xvii.

11

4 ,

6

3).

T h e city

of

Gaza was excepted from this arrangement,

and attached to the province of Syria.

Mt. 2

uses

the inaccurate expression

(and so Jos.

A n t . xviii.

4 3

T h e

troops indeed had saluted him as king on Herod’s death (Ant.

xvii.

but he refused

to

accept the title

it should be

confirmeh by Augustus

1

I

).

Probably in popular speech

i t

was given a s

a

matter of courtesy.

The coins with HPDAOY

must be his, for

no

other member of the family

bore the title; and, like Antipas, he used the family name of

Herod (so Dio

27

calls him

b

Josephus never calls him Herod.)

.Of the details of the administration of Archelaus we

know nothing, nor apparently did Josephus.

H e

indeed says that his rule

was violent and tyrannical

(cp

7 3 ,

and

Ant. xvii.

where he is charged

with

and

The description in the

parable is apt- Lk.

and

hence we can the better

the statement

in Mt.

222

respecting Joseph’s fear to

go to

Apparently Archelaus ‘did not take the pains to handle

gently the religious prejudices of his

Niese, however, rejects the reading

or

in

this passage, and restores

from

A n t . xviii.

7

2.

The proper title of Archelaus was ethnarch.

2031

HEROD,

F A M I L Y O F

Not only did he depose and set up high-priests a t

but he also took to wife Glaphyra, the daughter of the

Cappadocian king Archelaus (probably between

I

and

4

Glaphyra had been wife of Alexander, half-brother of

Archelaus, who was executed in 7

B.C.

(see

4,

iii.).

Her second

husband was Juba, king of

who

was indeed still

living when she married Archelaus.

Moreover, she had had

children by Alexander, and for this reason marriage with her was

After nine years of rule the chief men of

and

Samaria invoked the interference of the emperor, and

Archelaus

was banished to

in

G a u l

( A n t . xvii.

cp Dio

Cass.

55

It is to Archelaus that Strabo (765) refers when he says

that a

son of Herod was living, a t the time of his writing,

among the

for Vienna was their capital town. If

the statement of Jerome

that Archelaus’ grave was

near Bethlehem is trustworthy (cp

R

ACHEL

),

he must have re-

turned to Palestine to die.

The territory of Archelaus was taken

under the im-

mediate rule

of

Rome, and received

a governor of its

own of the equestrian order

see

I

SRAEL

,

90)

but it was under the general supervision

of the imperial legate of Syria (on the status of Judaea

at this time, see Momms.

R.

2

Forthwith, of course, the obligation to Roman tribute

fell upon the territory thus erected into a province

(hence, in

Jesus was brought face to face with

the whole question

of

the compatibility or otherwise of

Judaism with the imperial claims: cp Mt.

Mk.

Lk.

4 .

Herod

Jos.

Mk.

6

see below.] Son of Herod the Great by Mariamme,

daughter of Simon (son of

whom

Herod made high priest (about 24

In spite of Mk.

617

(see below), we cannot

hold that he ever really bore the name Philip; the

confusion, which is doubtless primitive, arose from the

fact that the son-in-law

of Herodias was called Philip

(see

2).

Herod’s first will arranged that

Philip should succeed in the event of Antipater’s dying

before coming to the throne (see

6) ;

but Philip was

disinherited owing to his mother’s share in Antipater’s

intrigues

(Ant. xvii.

4

30

7).

Philip lived and

died, therefore, in

a

private station, apparently in Rome

( A n t . xviii.

for it seems to have been in

that his half-brother Antipas saw Herodias.

It is

indeed only in connection with his wife Herodias, sister

of Agrippa

I.,

that the name of this Herod occurs in

the NT.

In Mk.

0

17

all MSS read

‘his

brother Philip’s wife

which it

appear that this Herod also bore the name Philip. When,

however, we find that Josephus knows only the name Herod

for him (cp

Ant. xvii. 13,

and

another

son of Herod the

also

bore the name Philip (see

suspicion is

aroused and this is confirmed when we find that of Philip’

is

omitted’ in Mt. 1 4 3 by D and some Lat. MSS (followed b y

Zahn

whilst

in

it

is omitted

NBD.

That’ Lk.

give the name is highly significant. An

appeal to the fact that several sons of Herod the Great bore the

name Herod cannot save the credit of

Mt.

and Mk. in this

particular ; for Herod

was a family and a dynastic

T h e coexistence in

family of the names Antipas and

Antipater

also no argument, for they are in fact different

names.

5 .

[Ti.],

[WH]

:

Mt.

H e deposed Joazar because of his share in the political

disturbances, and appointed his brother Eleazar. Soon Jesus

took the place of Eleazar. Finally Joazar

reinstated

(Ant.

xviii. 2

I

).

3

Sed

e t

propter

4

So Jos. Ant.

9

3.

I n

other places Boethos is the name

of her father.

The name

was

borne not only

Archelaus (see his coins,

8)

and Antipas (see

7),

after their rise to semi-royal

dignity hut also by two sons of Herod the Great who never

attained thereto-viz., the subject of this section, the son of the

second Mariamme, and also one of the sons of Cleopatra of

Jerusalem (Jos.

xvii.

13,

284).

T h e family belonged originally to Alexandria.

2032

HEROD, FAMILY

O F

Mk.

Daughter of Aristobdus

(Herods second son by Mariamme,

granddaughter of Hyrcanus).

Her

mother was Bernice (Berenice), daughter of' Salome,

Herod's sister. Herod of Chalcis (see

Agrippa

I.,

and the younger Aristobiilus, were therefore full brothers

of

Herodias.

According to Josephus

(Ant. xviii.

5

4 )

she

was wife first of her half-uncle Herod (see preceding

section), who is erroneously supposed to have been

also called Philip. The issue of this marriage was

the famous Salome who danced before Herod Antipas,

and thus became the instrument of her mother's venge-

ance upon the Baptist.

Herodias deserted her first

husband in order to marry his half-brother Antipas,

thus transgressing the law (cp Lev.

1816

Dt. 255).

I n

Mk.

6

the reading 'his daughter Herodias '

that of KBDLA. This would make

the girl

of Antipas and Herodias, bearing her mother's

name. Certainly the expression applied

to

her in the same

verse

is in

favour

of this

:

conversely if the ordinary

reading which designates the dancer

as

accepted

we

must admit

a

great disparity in

age

her and her

husband Philip the tetrarch if she is rightly called

28

A.D.

;

for

Philip died in

34

A.D.

at

the

age

of sixty

or

thereabouts. As the protest

of

in

to

the marriage by no means compels us to assume that the union

was recent, it is scarcely possible to maintain that a daughter

hy it must have been too

to dance at

a

banquet. In

our

ignorance of the chronology of the reign of Antipas

a

solution is

not

to

he had; though it is always possible by means

of

assumptions

to

create

a

scheme

that fits in with the received

reading (cp Schiir.

Hist. 2

28

n.,

and authorities there quoted).

It would scarcely be just to ascribe the action of

Herodias solely t o ambition; it was rather

a

case

of

real and intense affection.

I t is true that it was

Herodias who goaded her husband, in spite of his

desire for quiet and in spite of his misgivings

(Ant.

xviii.

7

to undertake the fatal journey to Rome but

she made what amends she could by refusing to accept

exemption from the sentence of exile pronounced upon

her husband by the emperor.

See above,

7.

6 .

Lk.

. . .

[Ti. WH].)

Son of Herod the Great by

Cleopatra,

a woman of Jerusalem (Jos.

Ant. xvii.

H e was

left in charge of Jerusalem and Judaea when Archelaus

hastened to Rome to secure his inheritance, but sub-

sequently appeared in Rome in support of his brother's

claims

61).

By the decision of Augustus in

accordance with the terms of Herod's last will (see 6 ) .

Philip succeeded to

a

tetrarchy consisting of Batanaea,

Auranitis, Gaulonitis, Trachonitis, and the district of

Panias (which last is, apparently, what Lk.

31

calls

'the

region,' though not indeed the whole.

of

it).

Cp

This list is obtained by combining

the different statements in Josephus

(Ant. xvii.

81

11

4

xviii.

46,

63).

Thus Philip's territory embraced the

poorest parts of his father's kingdom-those lying

E.

and

NE.

of the sea of Galilee as far as Mt. Hermon

:

the annual revenue from it was estimated a t one

hundred

The population was mixed, but was

mostly Syrian and Greek-;.e., it was predominantly

pagan.

Hence Philip's coins bear the image

of

Augustus or Tiberius

contrasting in this respect with those of Herod the Great (whicd

have neither name nor image of the emperor) and those of

Antipas (some of which bear the emperor's name, without his

image).

I n

addition, all the coins of Philip bear the image of a

temple (the splendid

temple

of Augustus

by Herod the

Great near the Grotto of

the source of the

Jordan

:

cp Jos.

'Ant.

xv.

10 3,

21 3).

Having been brought up, like all Herod's sons,

at Rome, Philip's sympathies were entirely Roman.

Owing to the non-Jewish character of his territory his

Hellenistic and Roman policy was more successful than

was the case

his brothers.

Of the events of his

Jos. Ant.

xvii.

8

I

inaccurately describes Philip

as

full

The Greek cities of

the

Decapolis

of course, outside

brother of

Philip's jurisdiction.

HEROD, FAMILY O F

thirty-seven years of rule

( 4

A.D.)

we know

indeed nothing beyond the summary given by Josephus.

His

rule

was

marked by moderation and quiet and his whole

life

was

spent in his

own

territory.

His

were

attended by

a

few chosen friends, and

the seat on

which he

sat

to

give judgment always followed him

;

so

that when

any

one, who wanted his assistance, met him

he made

no delay, hut

down the tribunal wherever he

be, and heard the

case'

(Ant.

xviii.

46).

seems to

have had scientific

from

t h e

story

of

his supposed discovery and

of the Jordan

were

really connected

a

subterranean passage

with

the

circular lake called

stades from Caesarea

10

7).

Apart from his evident administrative ability, Philip

retained only one quality of his race-the passion

for building.

Early in his rule h e rebuilt Panias

at the head-waters

of the Jordan,

and named it Caesarea; he also created the city

of Julias, formerly the village

of

Bethsaida.

S e e

B

ETHSAIDA

,

I

.

H e was only

once married-to Salome, the daughter

of Herodias-

and died without issue. After his death his territory was

attached to the province

of

Syria, retaining, however,

the right of separate administration of its finances

(Ant.

xviii.

46).

Gaius

on

his accession (37

A.D.)

gave i t

to Agrippa

I. with the title of king.

7.

Herod

[Ti.],

[WH],

Acts

Josephns and Coins).

Son of

(Herod the Great's son

by

Mariamme

I . ) and Bernice (daughter

of

Salome,

Herod the Great's sister: Jos.

Ant.

H e was called after his grand-

Shortly before the death

of

Herod the Great, Agrippa and

his mother

were

sent

to

Rome, where they

were

befriended by

Antonia, widow of the elder Drusus (brother of the emperor

Tiberius). Agrippa and

the younger

Drusus (the emperor's

son) became fast friends'

when Drusus died, in

2 3

A

.D.

Agrippa found himself

to

leave Rome with nothing

the memory of his debts and extravagances. He retired to

a

stronghold in Idumaea, and meditated suicide but

his wife

appealed

to

his sister Herodias, with the

result that Antipas

gave

him

a

pension and the office

of

(controller of the market)

at

Tiberias. Before

very

long there was

a

quarrel, and Agrippa resumed his career

as adventurer. For

a

time he was with the Roman governor

Flaccus in Antioch; but ultimately he arrived again in Italy

after running the gauntlet of his creditors

xviii.

6

He attached himself

to

Gaius the grandson

of

Antonia. An incautiously uttered wish for the speedy ac-

cession of Gaius (Caligula) was overheard and reported to the

old emperor, and Agrippa lay in prison during the last six

months of Tiherius.

Caligula, on his accession (37

A.D.)

a t

set

Agrippa free, and bestowed upon him what had been

the tetrarchy of his half-uncle Philip, together with that

of

Lysanias

A

BILENE

Lk.

31

c p Dio Cass.

with the title of king (cp Acts 121) and the right

to wear the diadem; h e also presented him with a

golden chain equal in weight to his iron fetters

(Ant.

xviii.

6

IO).

The Senate conferred upon him the honorary

rank

of

praetor (Philo, in

6 ) . Three years

later h e obtained the forfeited tetrarchy of Herod

Antipas

(Ant. xviii.

H e adroitly used his influence

with the emperor to induce him to abandon his mad

design of erecting

a statute of himself in the temple

at

Jerusalem

(Ant. xviii.

8

Agrippa

Rome when

Gaius fell by the dagger

of Chaerea (Jan. 41

A .

D . ) ,

and by his coolness a t

a critical moment contributed

largely to securing the empire for Claudius

(Ant.

xix.

4

).

In return for this service he received Judaea

and Samaria, being also

in his previous

possessions

'he also obtained consular rank

(Ant.

Cypros was daughter of Phasael, whose wife was his cousin

Salampsio, Herod the Great's daughter by the

Mariamme.

Apparently this abandonment was only temporary

:

a

peremptory decree

was

finally sent, and the crisis

was

averted

only by

the

emperor's assassination. The account given by

Josephus of the manner of Agrippa's intervention differs

from

that given by Philo

Leg.

and seems worked

up on conventional'lines-this romantic apocryphal element is

very conspicuous in the whole account

of

Agrippa's life.

xviii.

5

4).

'*

father's friend Agrippa (see

4).

HEROD,

FAMILY OF

Dio Cass.

6 0 8 ,

These grants were confirmed by solemnities

in the

(cp Suet.

Claud.

25).

For his brother

Herod he obtained the grant of the kingdom of Chalcis

in Lebanon.

In part also at least his influence must be

seen

in

the edicts published by

in favour of

the Jews throughout the empire, freeing them from

those public obligations which were incompatible with

their religious convictions. In pntting under Agrippa

the whole extent of territory ruled by his grandfather,

it was certainly the design of Claudius to resume the

system followed

at

the time

of

Herod the Great and to

obviate the dangers

of

the immediate contact

the Romans and the Jews (Mommsen,

Prow.

of

Now began the second period in Agrippa's life, in

which the spendthrift adventurer appears as

a

model

of Pharisaic piety.

He began his three years of actual

rule with significant acts-the dedication in the temple

of the golden

received from Gaius, the offering of

sacrifices in all their details, and the payment

of

the

charges of a great number

of

Nazirites (cp Acts

21

24).

He loved to live continually in Jerusalem, and strictly

observed the laws of his country, keeping himself in

perfect purity, and not allowing a single day to pass

over his head without its sacrifice' (Jos.

xix.

:

so in the Talmud, if the references are not in part to the

younger Agrippa).

His appeal to Petronius, governor

of Syria, in the matter of an outrage against Judaism

in the Phoenician town of Dora was based on general

grounds of policy and national self-respect, and need

not be traced specially to his correct attitude with

regard to Pharisaism.

It was undoubtedly

a

conse-

quence of this attitude that, though of

a

disposi-

tion

he began

a persecution of the

Christians (Acts

121). James the great was sacrificed,

and Peter escaped only by a miracle.

Agrippa's action against the Christians is supposed by some

to have been due to the famine over

'

all the world (Acts 11

a

generalisation which cannot be entirely defended by the

that marked the reign of Claudius (Suet.

Claud.

or the enumeration of the occasions mentioned hy

authors (in Rome, a t the beginning of his reign, Dio

Cass. GO

.

in Greece in his eighth

or ninth year, Eus.

2

in

in

eleventh year,

Ann. 12 43.

Cp

Zahn,'

2

Just a s little can we defend the words

. .

of the inscr. of

in

referring to famine

Minor in 57

A.D.

Rams. Stud.

IV.,

96,

p.

The ex-

aggeration

I

S

natural.

I t is indeed true that often subsequently

public calamities were the signal for persecution (cp Blass, Act.

the famine referred to in the prophecy of

Agabus occurred in 45-46

A

.D.

Rams.

pp. 49,

after the death of Agrippa. Nevertheless the latest

date that will fit the prophecy is

if not earlier. Such

a

prophecy might well be regarded outside the Christian circle

as

a threat.

The outspoken Jewish sympathies

of the king cost

him the affection of the towns that adhered to the

Romans, and of the troops organised in Roman

fashion

:

at any rate the report of his death was re-

ceived with outrageous jubilation on the part of the

troops in

on the coast

Jos.

Ant. xix. 9

I

xx.

8

7).

T h e striking incident recorded in the Mishna

is

to

b e referred to this Agrippa rather than to Agrippa

When

at

the Feast of Tabernacles (consequently

41

A

.D.)

he read,

to

custom. the Book of Deuteronomv. he burst into

cried

The question as

to how far Agrippa was sincere in

all this is difficult.

I t must be remembered that Agrippa was not only a vassal

king (see

4),

but a Roman citizen, belonging by ado

to

the Gens

(cp the inscr. quoted under B

ERE

N

I

CE

,

2 162

n.), so that he owed concessions to the imperial

system that were not in strictness compatible with his position

a s a Jewish monarch. This fact must have been recoguised by

the strictest Jew (always excepting the fanatical Zealots), who

must perforce have tacitly consented to the king's playing

behalf of the nation two contradictory parts. I t is true, the

Strictly justified by

HEROD,

FAMILY

O F

difficulty with which he had to grapple was only

standing

problem of his house. As compared with his grandfather, how.

ever, he had this advantage-that rival claims were silenced.

or rather in his own person he combined those of both

and Herodians. At the same time, his long residence

Rome, where he had been in closest contact with the main.

spring of the imperial machinery, had given him an insight into

the possibilities of his rule far superior to that possessed by any

other member of the

Two episodes of his reign show

clearly that he grasped these possibilities.

On the

of

Jerusalem he began the building of a wall which, if completed,

would have rendered the city im regnable to direct assault.

I t

was

stopped by the emperor

report of C. Vibius

who, as governor of Syria, had the duty of watching the

interests in the protected states in his neighhourhood (Jos.

Ant.

xix.

; cp

5

Of still greater significance

was the conference of vassal princes of Rome assembled by

Agrippa a t Tiberias,

Antiochus of Commagene,

ceramus of Emesa Cotys of Armenia Minor, Polemon of

Pontus, and Herod

Chalcis. This was rudely broken up by

Marsus himself (Ant.

8

I

)

.

The

skill with which Agrippa brought into alliance

with

the Pharisaic element, which, alike

in

its

moderate and in its extreme

constituted the

backbone of the nation,

the intention of finding

therein a basis for a really national policy, proves him

to have possessed statesmanlike qualities even superior

to those of Herod the Great.

His premature death

prevented the realisation of his schemes; but

it

is at

least doubtful whether we shall not be right in holding

that the glory of the Herodian rule reached its real

culmination in Agrippa's reign.

Of Agrippa's death we have two accounts.

According to Josephus he went to Caesarea in order to

celebrate games in

of the emperor (Ant. xix. 8

can only refer to the safe return

of Claudius from his victorious British expedition spring of

44

A

.D.

: cp Dio Cass. GO 23

;

Suet.

T h e leading

men of the kingdom were there gathered (Acts1220 mentions

particularly a deputation from

T

re and Sidon, introduced by

Blastns, the. king's chamberlain

the second day of the

festival, as

entered the theatre clad

a robe of silver tissue

gleaming in the sun, Agrippa was saluted by his courtiers as

more

The shouts of

and

as

if

to

a divine being, remind us of Acts 12

god's voice and not

man's'

Shortly afterwards

looking upwards, the king spied an owl sitting over his head

of the ropes, and recognised it as the messenger of doom

(alluding to the omen which,

his early imprisonment

portended his good

A n t .

xviii. 6

7).

He

was seized

that instant with severe pains, and

in five days he was dead.

Though more detailed, this account agrees substantially with

that in the NT.

It has been suggested, however, that the two narra-

tives are actually connected with each other, and that

the intermediate stage is marked by the rendering

of

the story in Eusebius

in which the owl

of

Josephus appears as an angel. T h e narrative of Acts

is not without its apocryphal features.

Note especially the expression 'he was eaten of worms'

23,

For this there is no warrant

Josephus, who describes perhaps an attack of peritonitis

8'

To

be eaten

of worms was the conventional ending of tyrants and monu-

mental criminals

queen of Cyrene, Herod.

4

Sulla the Dictator, Plut., who gives other instances.

Antiochns Epiphanes,

Macc. 9

not in

I

Macc. G

8

;

end of Herod the Great is evidently regarded as very similar).

I n this

tradition, Christian and pagan, took its revenge.

8.

Herod

-

[Ti. WH], Acts

;

6

simply, or

in Jos.

and after his accession

His full

name, Marcus Julius Agrippa, is found

coins and inscriptions, see

Hist.

2

n.

).

He was only seven-

teen years old at the time of his father's death, and

though personally inclined to the contrary,

was advised not to allow him to succeed to his father's

kingdom

( A n t . xix.

9

I

) .

Son of Agrippa

I.

and Cypros.

HEROD,

FAMILY O F

The

government had here, as elsewhere

lighted

on the right course,

had not the energy to carry

out

irrespective of accessory considerations (Momms. Prow.

2

The death of the elder Agrippa, in

had as its consequence the final absorption of all Palestine

west of the Jordan (with the exception of certain parts of

Galilee subsequently given to his son) within the circle of

directly-governed territory

5 9).

Agrippa

resided in Rome, where he was able to

use his influence with some effect

on

behalf of the Jews

1 2 6 3 ) .

His uncle, Herod of Chalcis, had

been invested by Claudius with the superintendence of

the temple and the sacred treasury, together with the

right of nominating the high priest (Ant. xx.

1 3 )

on

his death in 48

these privileges were transferred to

Agrippa

Agrippa also received his uncle's kingdom

of Chalcis

(50

A

.

D

. :

Four years later he

surrendered this, and received in return what had been

the tetrarchy of Philip

Gaulonitis, and

Tracbonitis), with Abila, which had been the tetrarchy

of

This was in

53

A.D.

This

realm was further enlarged by Nero, who conferred

upon

the cities and territories of Tiberias

Taricheae

on the sea of Galilee, and the city of Julias

with fourteen surrounding villages

Ant.

xx. 84). This accession of territory was made prob-

ably in

56

A.

D.

(see Schur.

Hist. 2

n.

).

Agrippa gratified his hereditary passion for building

by the improvement of his capital Caesarea (Philippi),

which he named Neronias (see his coins), and by adding

to the magnificence of the Roman colony of Berytus

(Ant.xx.94).

In all other directions his hands were

tied, and the history of the previous few years must have

convinced him that it was no longer possible for

a Jewish

king to play any independent part.

It is probable that

his general policy should be ascribed to astuteness rather

than to indolence and general feebleness (Schur. Hist.

2196). By training he was far more a Roman than

a

Occasionally, indeed, he yielded to the claims of

his Jewish descent (see, however, col. 754, top) but as

a rule he was utterly indifferent to the religious interests

of his time and country, and the subtleties of the scribes

can only have amused him.

(See

'

Agrippa

und der

Judaa's nach

Untergang Jerusalems,'

I n Acts 25 13-26

32

we have a n interesting account of

a n appearance of Paul before the Jewish king and the

Roman governor Festus a t Caesarea. T h e utterance of

Agrippa in 2628 has been well explained by B. Weiss

in 'Texte

Untersuch.

Gesch. der

Christ. Lit.'

3 4). Inaccordance with what we know

of Agrippa's character, it must be viewed as

a virtual

repudiation of that belief

the prophets which was

attributed to him by Paul.

King Agrippa ! believest

thou the prophets,' Paul, had said

I know that thou

believest

27).

T h e gently ironical rejoinder amounts

t o this .:

on slight grounds you would make me a believer

in your assertion that the Messiah has come.'

(For

another view see

CHRISTIAN,

N

AME

OF,

754,

n.

I

) .

Agrippa did

all in his power to restrain his country-

men from going to war with Rome and rushing

on

destruction

and he steadfastly maintained

his own loyalty

to Rome, even after his

cities

joined the revolutionary party.

There was

no other

course to pursue. T h e catastrophe was inevitable the

last

of the Herods could not help witnessing, and to

some extent aiding it.

For a time he was at Rome

but on his return to Palestine he went to the camp of

Titus, where he remained until the end of the war.

Probably he was present at the magnificent games with

which Titus celebrated at Caesarea (Philippi) his con-

quest of Jerusalem

21). On the conclusion of

the war Agrippa's dominions were extended in

a northerly

There is indeed no mention of the conferring of the right

of

appointing the high priest but Agrippa is found exercising

it

His coins, almost without exception, bear the name and

image of the reigning emperor-Nero, Vespasian, Titus, and

Domitian.

HEROD,

FAMILY

O F

direction.

In 75

he went to Rome, and was raised

to the

of praetor (Dio Cass.

66

15).

W e know that

he corresponded with Josephus about the latter's

History

the

Jewish

which he praised for its accuracy

(Jos.

65

1 9 ) .

He appears

to

have died in

third year

He left

no

descendants

perhaps, indeed, he was never married.

His

were incorporated in the province of Syria.

9. Berenice.

-

[Ti.

W H ]

:

the

form of

The oldest of the three

daughters

of

Agrippa I. (Jos. Ant. xix.

She was betrothed to Marcus, son

of Alexander the Alabarch but he died

before the marriage took place

( A n t .

5

I

).

About

41

being then about thirteen years old, Berenice

became the second wife

of

her uncle Herod of Chalcis,'

by whom she had two

sons,

Bernicianus and Hyrcanus

116).

When Herod died

in

48

A.D.

Berenice

joined her brother

Rome, and black stories were

circulated as to their

With the object of