i

APPLICATION OF MEMBRANE BIOREACTOR SYSTEMS FOR

LANDFILL LEACHATE TREATMENT

by

Boonchai Wichitsathian

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the

degree of Doctor of Technical Science

Examination Committee: Prof. C. Visvanathan (Chairman)

Dr. Preeda Parkpian

Dr. Josef Trankler

Prof. Athapol Noomhorm

External Examiner: Prof. F.W. Günthert

Institut für Wasserwesen

Fakultät für Bauingenieur- und Vermessungswesen

Universität der Bundeswehr München

Neubiberg, Germany

Nationality: Thai

Previous Degrees: Bachelor of Industrial Chemistry

King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Thonburi

Bangkok, Thailand

Master of Environmental Technology

King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Thonburi

Bangkok, Thailand

Scholarship Donor: Royal Thai Government

Asian Institute of Technology

School of Environment, Resources and Development

Thailand

August 2004

ii

Acknowledgements

I would like to deeply express my profound gratitude to his advisor, Prof. C.

Visvanathan for kindly giving his stimulating ideas, valuable guidance, numerous

constructive suggestions and encouragement through his study at AIT. The author also

would like to thank Dr. Preeda Parkpian, Dr. Josef Trankler, Dr. David A. Luketina, Dr.

Lee Seung-Hwan, and Prof. Athapol Noomhorm for their valuable comments, critical ideas

and serving as members of examination committee.

I am greatly indebted to Prof. F.W. Gunthert for kindly accepting to serve as

External Examiner. His valuable advice, guidance and professional comments are highly

appreciated.

I gratefully acknowledge to Royal Thai Government for the financial support.

I am very grateful to Ms. Sindhuja Sankaran and Ms. Loshnee Nair for providing

comments and helping throughout my study at AIT.

I sincerely would like to thank all staffs and my lab colleagues in the

Environmental Engineering Program for friendship, help, and moral support, which

contributed in various ways to the completion of this dissertation.

Sincere gratitude is expressed to the Pathumthani municipality and Ram-indra

transfer station office, Thailand, for the useful information and assistance on the leachate

and sample collection.

Finally, I would like to express my deepest gratitude and dedicate this research

work to my parents, all family members and special friends, whose love, assisted me

through difficult times and contributed to the success of this study.

iii

Abstract

Landfill leachate is a complex wastewater with considerable variation in both quality

and quantity. The composition and concentration of pollutants are influenced by the types

of waste deposited, hydrogeological factors, and more significantly by the age of the

landfill site. In general, leachate is highly contaminated with organic contaminants

measured as chemical oxygen demand (COD) and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD),

and also with high ammonium nitrogen concentration. Biological processes have been

found ineffective for leachate from relatively old landfill. In leachate containing high

concentrations of organic and nitrogen compounds such cases result in possible serious

environmental problems near the landfill site.

This research was undertaken to investigate the performance of a membrane

bioreactor (MBR) using mixed yeast culture (YMBR) and mixed bacteria culture (BMBR)

in treating raw leachate containing high organic and nitrogen concentrations. The

inhibition effects of ammonium nitrogen and lead on yeast and bacteria cultures were

determined by measuring the oxygen uptake rate (OUR) using the respirometric method.

Furthermore, for both YMBR and BMBR, treating the stripped leachate, they were

assessed the treatment efficiency to compare the results with those treating the raw

leachate.

The inhibition experiment revealed that a bacteria culture was very sensitive to

ammonium nitrogen when it was compared to a yeast culture. Also the values of biokinetic

coefficients showed that the specific growth rate (µ) in bacteria system was influenced. At

ammonium concentration of 2,000 mg/L, the response of OUR inhibition in a bacteria

system was approximately 37% whereas it was around 6% in a yeast system. Furthermore,

both yeast and bacteria cultures were also sensitive to lead.

In a MBR, treating raw leachate, the COD removal rate for BMBR was slightly

lower than the YMBR for varied hydraulic retention time (HRT) at high volumetric

loading rate. The average COD removal efficiency in BMBR was 62±2% while in YMBR

was 65±2%. The YMBR could obtain higher COD removal rate at higher volumetric

loading rate than the BMBR. This indicated that the yeast system can treat leachate

containing high organic and nitrogen concentrations. The average TKN removal efficiency

for both BMBR and YMBR systems was from 14-25% and 19-29%, respectively. The

nitrite and nitrate concentrations (NO

2

-

and NO

3

-

) were found to be very low.

The comparative evaluation of treatment performance of MBR, treating stripped

leachate, was examined. The COD removal of both BMBR and YMBR was above 70% at

HRT 16 h and 24 h. As a result, the pretreatment with ammonia stripping prior to BMBR

showed more significant improvement in terms of COD removal when it was compared to

YMBR. This could be confirmed that the trend of inhibition effect on bacteria was

dependent upon the ammonium nitrogen concentration. The range of BOD concentration

of effluents from both YMBR and BMBR, treating the stripped leachate was from 30-55

mg/L. This level followed the present effluent standard. Although BOD could be reduced

to lower values with these methods, the treated leachate still contained a large quantity of

refractory organic compounds. This might be due to the contribution of the slowly

biodegradable organics and non-biodegradable organics contained in the leachate.

Therefore, they should be further treated in a post treatment for elevating the final effluent

to meet the present effluent standard or even increasing the biodegradable organics.

iv

Under the same operating conditions, the YMBR could run under transmembrane

pressure (TMP) 1.3-2.5 times lower than the BMBR with the significantly reduced

membrane fouling rate. This might be due to the soluble extracellular polymeric substances

(soluble EPS). Hence, yeast system could enhance membrane performance and had the

potential to improve the treatment system due to reduction of operational problems. In

addition, bacteria sludge showed a better dewatering quality compared to that of the yeast

sludge.

v

Table of Contents

Chapter Title

Page

Title Page

i

Acknowledgements

ii

Abstract

iii

Table of Contents

v

List of Tables

viii

List of Figures

x

List of Abbreviations

xii

1

Introduction

1

1.1 Background

1

1.2 Objectives of the Study

3

1.3 Scope of the Study

4

2

Literature Review

5

2.1 Introduction

5

2.2 Solid Waste Management Practices

6

2.3 Municipal Solid Waste Landfill

7

2.4 Municipal Solid Waste Landfill Leachate

7

2.5 Leachate Composition and Characteristics

8

2.6 Molecular Weight Distribution in Landfill Leachate

11

2.7 Factors Affecting Leachate Composition

12

2.7.1 Seasonal Variation

13

2.7.2 Landfill Age

14

2.7.3 Composition of the Waste Dumped

16

2.7.4 Geological Characteristic

16

2.7.5 Filling Technique

16

2.8 Leachate Treatment

17

2.8.1 Biological Treatment Processes

18

2.8.2 Physical Treatment

24

2.8.3 Chemical Treatment

30

2.8.4 Natural Leachate Treatment Systems

33

2.8.5 Co-Treatment with Municipal Wastewater

35

2.9 Combined Treatment Facility

36

2.9.1 Biological Treatment and Reverse Osmosis

36

2.9.2 Microfiltration and Reverse Osmosis

37

2.9.3

Denitrification-Nitrification/Ultrafiltration and Reverse Osmosis 38

2.9.4 MBR-UV and Ozone-Reverse Osmosis

39

2.10

Microbial Toxicity

39

2.11 Membrane Bioreactors

41

2.11.1 Membrane Configuration

42

2.11.2 Application of Membrane Bioreactors

44

2.11.3 Sludge Characteristics

45

2.12 Yeasts

49

2.12.1 Introduction

49

2.12.2 Applications of Yeasts for Wastewater Treatment

49

vi

2.13 Rationale for the Study and Proposed Treatment Sequence

52

2.13.1 Leachate Characteristic

52

2.13.2 Need for Ammonia Stripping

52

2.13.3 Need for Membrane Bioreactors

53

3

Methodology

54

3.1 Introduction

54

3.2 Leachate Characterization

54

3.3 Seed Study

55

3.3.1 Yeast and Bacterial Sludge

55

3.3.2 Acclimatization

56

3.4 Toxicity Studies

56

3.4.1 Ammonia Toxicity

57

3.4.2 Lead Toxicity

58

3.5 Ammonia Stripping

58

3.6 Membrane Bioreactor

59

3.6.1 Membrane Resistance Measurement

59

3.6.2 Experimental Set-up

60

3.6.3 Parametric Studies

62

3.6.4 Molecular Weight Distribution

62

3.6.5 Sludge Characterization

64

3.7 Ammonia Stripping Coupled Membrane Bioreactor

64

3.8 Analytical Methods

65

4

Results and Discussion

67

4.1 Simulation of Leachate Characteristic for Treatment of

Middle Aged Leachate

67

4.2 Biokinetic Studies

68

4.2.1 Acclimatization of Mixed Yeast and Bacterial Sludge

68

4.2.2 Kinetics of Yeast and Bacterial Growth

72

4.2.3 Toxicity Studies

75

4.3 Application of Yeast and Bacteria Based Membrane Bioreactors

in Leachate Treatment

80

4.3.1 Initial Membrane Resistance

81

4.3.2 Optimization of HRT in Terms of Membrane Bioreactor

Treatment Efficiency

82

4.3.3 Membrane Fouling and Membrane Resistance

89

4.4 Application of Yeast and Bacteria Based Membrane Bioreactors

in Ammonia Stripped Leachate Treatment

91

4.4.1 Ammonia Stripping Studies

91

4.4.2 Membrane Resistance and Membrane Cleaning

95

4.4.3 Performance of Ammonia Stripping Coupled Membrane

Bioreactor Process

97

4.5 Other Studies

106

4.5.1 Biodegradability of the Leachate

106

4.5.2 Molecular Weight Cut-off

110

4.5.3 Sludge Properties

115

4.5.4 EPS Formation

116

4.5.5 Conductivity and TDS

117

vii

4.5.6 Cost Analysis for Operation

117

5

Conclusions and Recommendations

119

5.1

Conclusions

119

5.2 Recommendations for Future Work

121

References

123

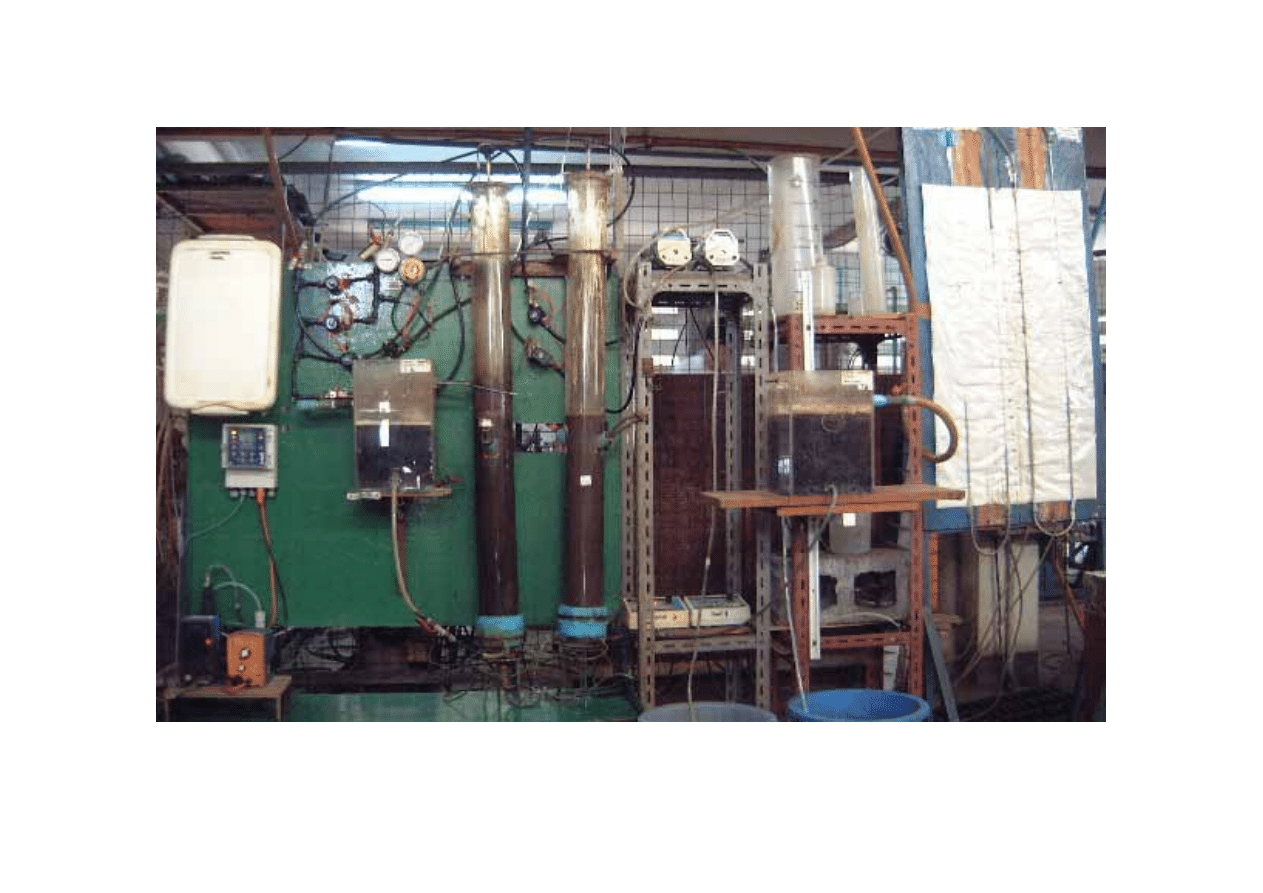

Appendix A: Pictures of Experiments

141

Appendix B: Leachate Characteristics and Experimental

Data of Acclimation

145

Appendix C: Experimental Data of Biokinetic Study and

Toxicity Study

149

Appendix D: Membrane Resistance Studies

155

Appendix E: MBR without Ammonia Stripping

163

Appendix F: Ammonia Stripping Studies

171

Appendix G: MBR with Ammonia Stripping

174

Appendix H: Other Studies

179

viii

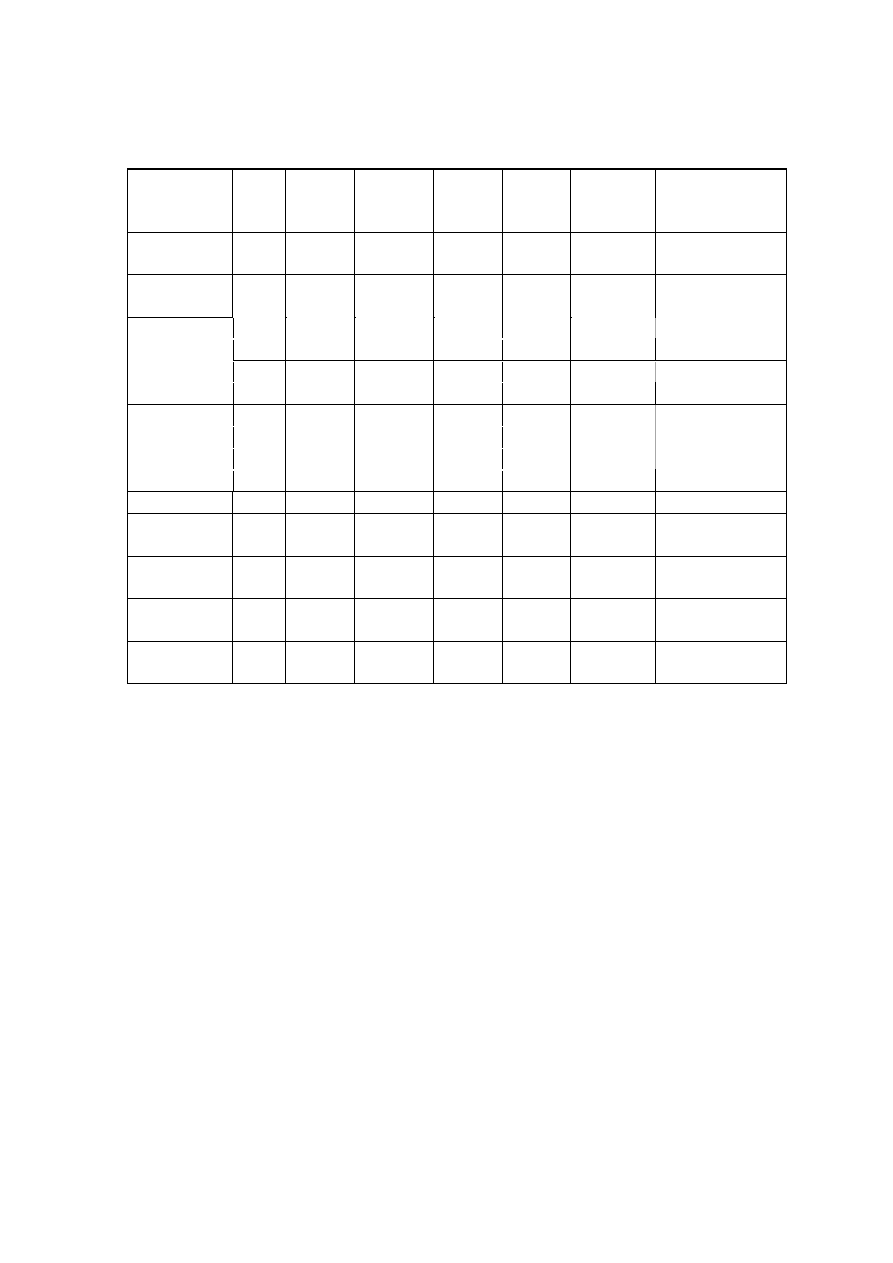

List of Tables

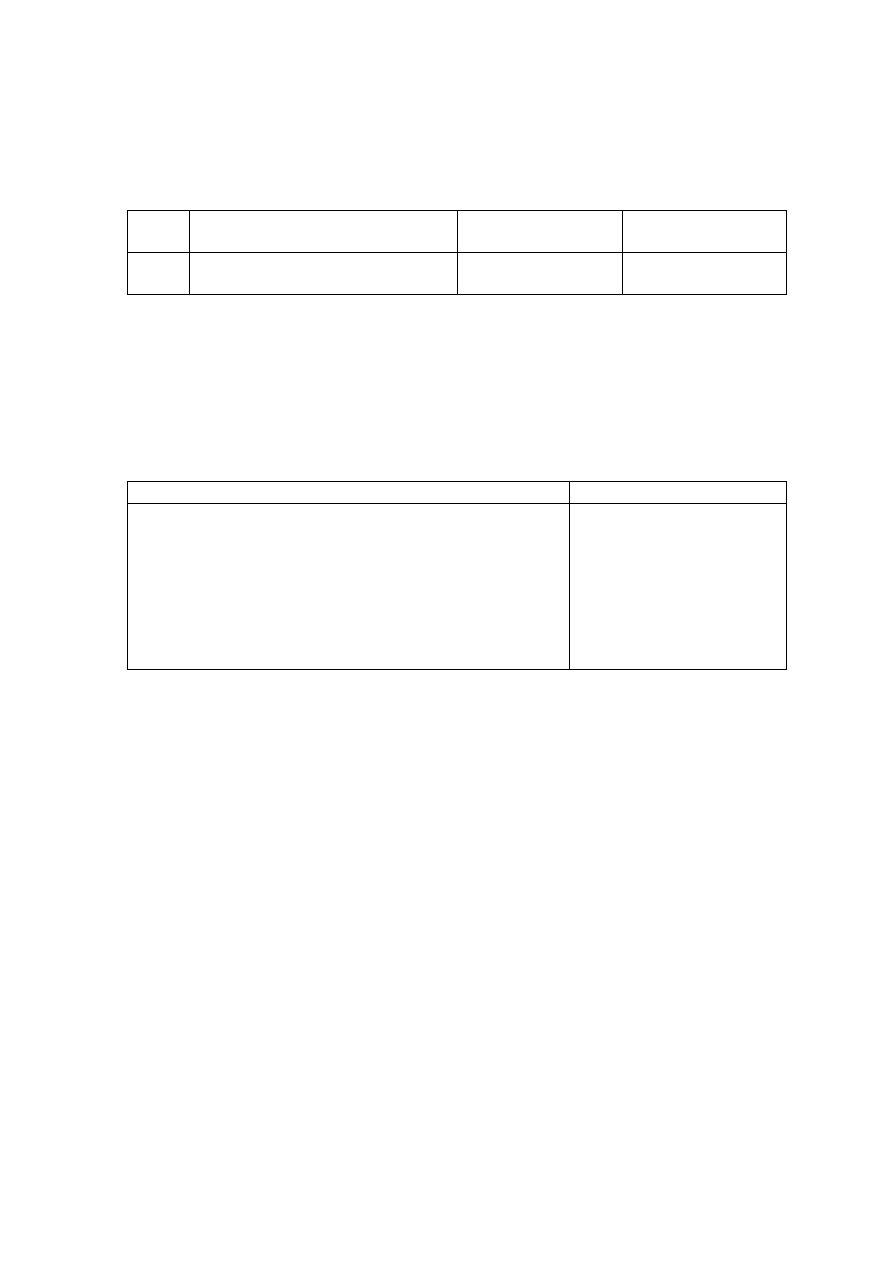

Tables Title

Page

2.1

Leachate Characteristic in Acidogenic and Methanogenic Phase

in a Landfill

8

2.2

Comparison of Leachate Characteristics of Landfills Surveyed in

Asia, Europe and America

10

2.3

Relation between Landfill Age, Leachate Characteristics and Treatments 11

2.4

Classification of Types of Substances Using Molecular Weight Cutoff

12

2.5

Variation of COD, BOD & BOD/COD with Increasing Landfill Ages

15

2.6

Nitrogen Concentrations from Various Sources

15

2.7

Nitrogen Concentration Ranges in the Leachate for Landfill Stabilization 15

2.8

Summary of Biokinetic Coefficient of Activated Sludge Process for

Landfill Leachate Treatment

19

2.9

Operational and Environmental Conditions for Nitrification-

Denitrification Processes

23

2.10

Treatment Efficiencies of Different Aerobic Biological Treatment

Systems

25

2.11

Treatment Efficiencies of Different Anaerobic Biological Treatment

Systems

26

2.12

Membrane Processes

28

2.13

Removal Efficiency of Moderate to High Concentrations of Pollutants

Using Nanofiltration, Ultrafiltration and Reverse Osmosis

28

2.14

Typical Reverse Osmosis Plant Performance for Leachate Purification,

Germany

30

2.15

Treatment Efficiencies of Different Physico-chemical Treatment Systems 34

2.16

Typical Leachate Composition at Each Stage of Leachate Treatment Plant 39

2.17

Inhibitory Effect of Various Toxicants

41

2.18

Advantages and Disadvantages of Membrane Bioreactors

43

2.19

Operating Conditions of Membrane Bioreactor Process for Treatment

of

Different

Kinds

of Wastewater

46

2.20

Operating Conditions of Yeast System Compared with Activated

Sludge Process

51

2.21

Performance of Yeast Based Treatment System in Dried Food Products

and Marine Product Industry

51

3.1

Composition of Simulated Leachate

55

3.2

Operating Conditions for Yeast and Bacteria Acclimatization

56

3.3

Operating Conditions for Yeast and Bacteria Mixtures in Respirometer

57

3.4

Description of the Chemical Cleaning

60

3.5

Technical Parameters of the Experimental Plant

60

3.6

Experimental Operating Conditions of YMBR and BMBR Systems

62

3.7

Characteristics of Ultrafiltration Membrane

64

3.8

Parameters and Their Analytical Methods

66

4.1

Compositions of Leachate Simulated from Leachates Obtained from

Pathum-thani Landfill Site (PS) and Ram-Indra Transfer Station (RIS)

67

4.2

Biokinetic Coefficients of Yeast and Bacteria Sludge for the Leachates

74

4.3

Effect of Free Ammonia Concentration on Yield Coefficient and the

Specific Growth Rate of the Bacterial Sludge

76

ix

4.4

Effect of Free Ammonia Concentration on Yield Coefficient and the

Specific Growth Rate of the Yeast Sludge

77

4.5

Substrate Utilization by the Yeast and Bacterial Sludge

79

4.6

COD Removal Efficiency in YMBR System at Different HRT

85

4.7

COD Removal Efficiency in BMBR System at Different HRT

86

4.8

TKN Removal Efficiency in YMBR System

88

4.9

TKN Removal Efficiency in BMBR System

88

4.10

Membrane Cleaning Frequency in the MBR Systems

90

4.11

Membrane Resistance in the MBR Systems

90

4.12

Variation in Ammonia Removal Efficiency

94

4.13

Determination of Membrane Resistance of Membrane Module after

Clogging in BMBR system (A = 0.42 m2; Pore Size = 0.1 µm)

96

4.14

Contribution of BOD at 5, 10 and 15 Days to the Total 20 Days BOD

108

4.15

Sludge Properties in the YMBR and BMBR Systems

115

4.16

MLSS and MLVSS Concentrations in Yeast and Bacteria Reactors

116

4.17

Bound EPS Concentration in the YMBR and BMBR Systems

116

4.18

Soluble EPS Concentration in the YMBR and BMBR Systems

116

4.19

Conductivity and TDS Concentrations in Leachate and Effluents

117

4.20

Cost of Chemical Used for pH Adjustment

118

4.21

Total Chemical Cost Requirement for Each Treatment System

118

x

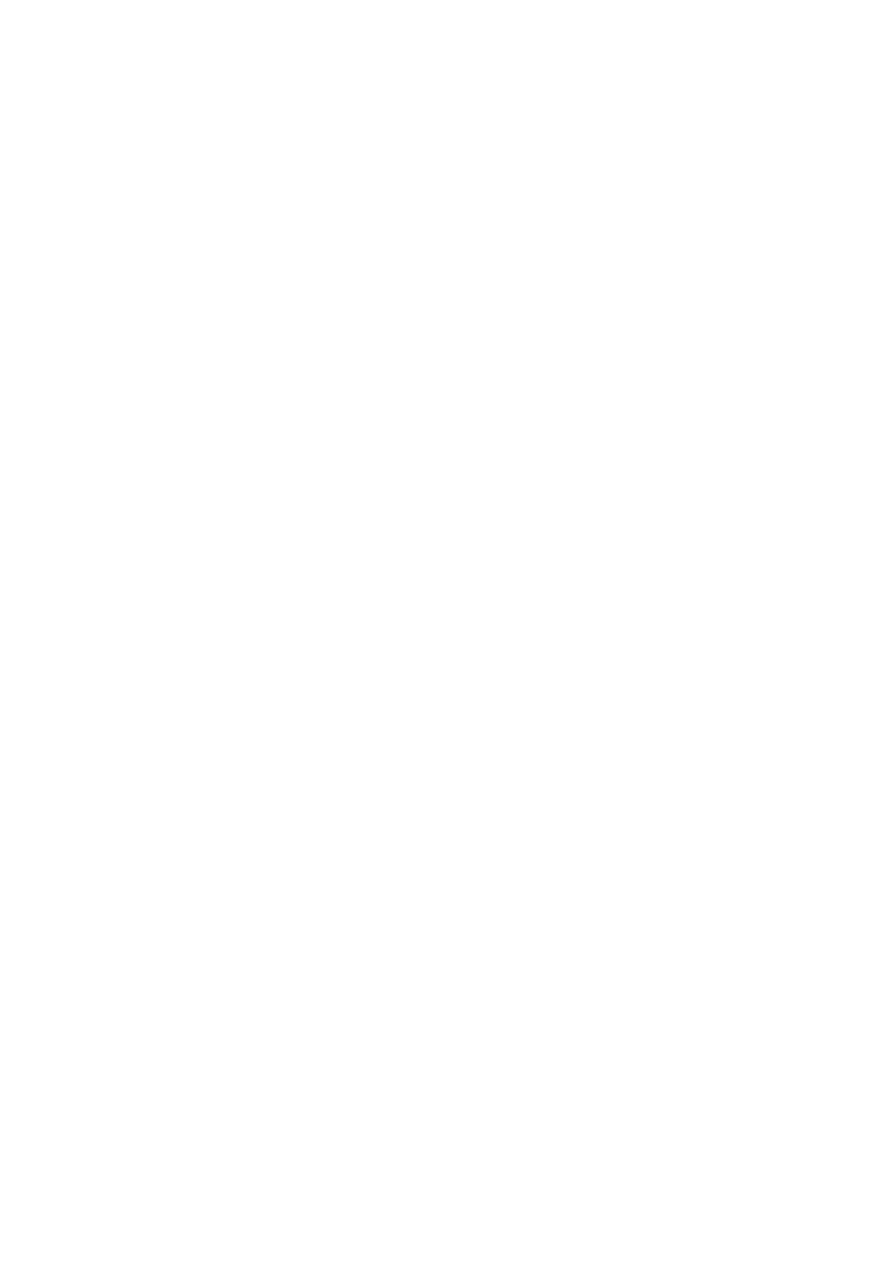

List of Figures

Figures Title

Page

2.1

Schematic Representation of a Typical Engineered Landfill

6

2.2

Changes in Significant Parameters during Different Phases of

Landfill Stabilization

7

2.3

Variation in Significant Pollutant Ratios with Increase in Age

of the Landfill

9

2.4

Water Movements in the Landfill

13

2.5

Leachate Productions and Rainfall Variation with Time

14

2.6

Treatment of Landfill Leacahte with Two Stage Reverse Osmosis

29

2.7

Schematic Diagram of Biological Treatment and Reverse Osmosis

for Leachate Treatment

37

2.8

Schematic Diagram of Microfiltration/Reverse Osmosis for

Leachate Treatment

38

2.9

Schematic Diagram of Denitrification-Nitrification/UF and

Reverse Osmosis for Leachate Treatment

38

2.10

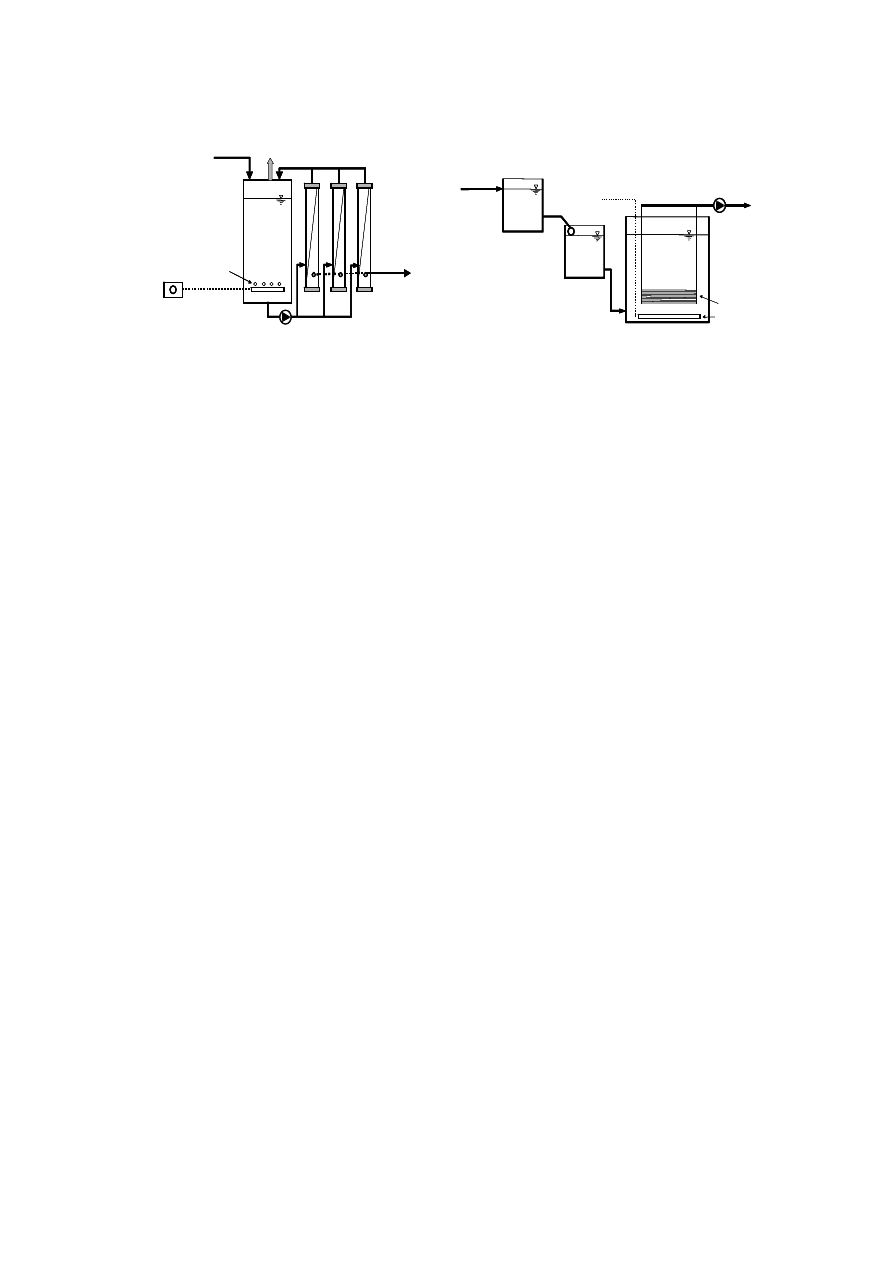

Schematic Diagrams of (a) External Recirculation MBR and

(b) Submerged MBR System

42

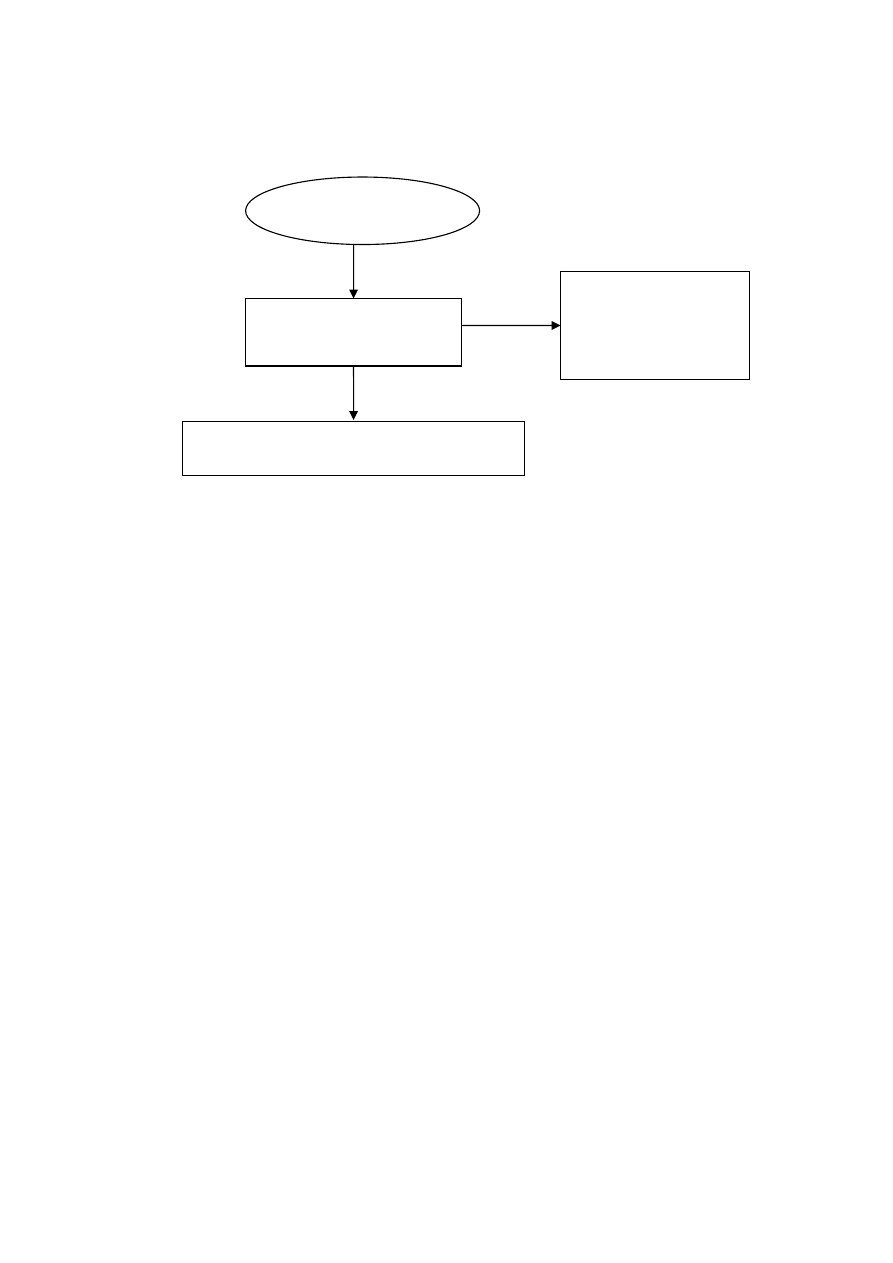

3.1

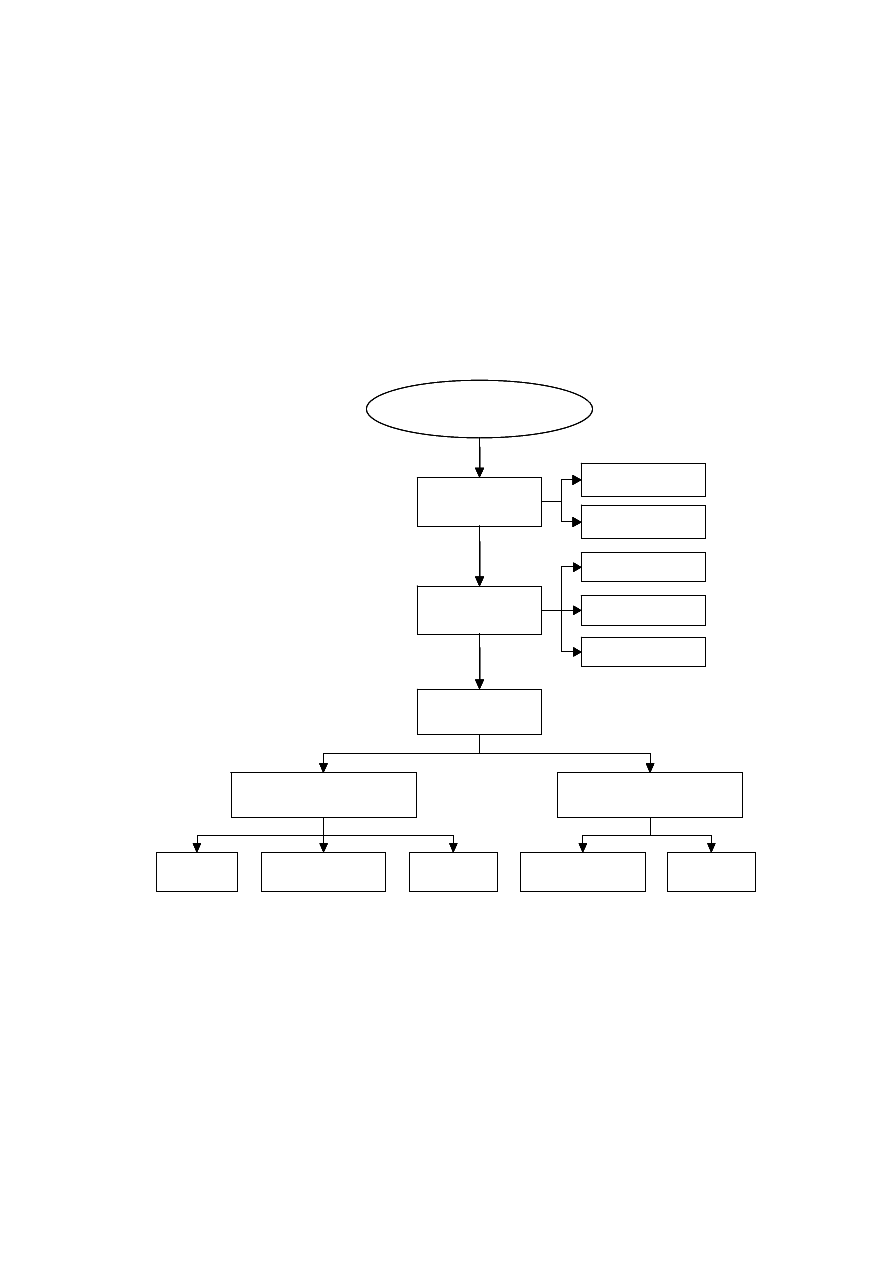

Flowchart Showing Different Stages of Experimental Study

54

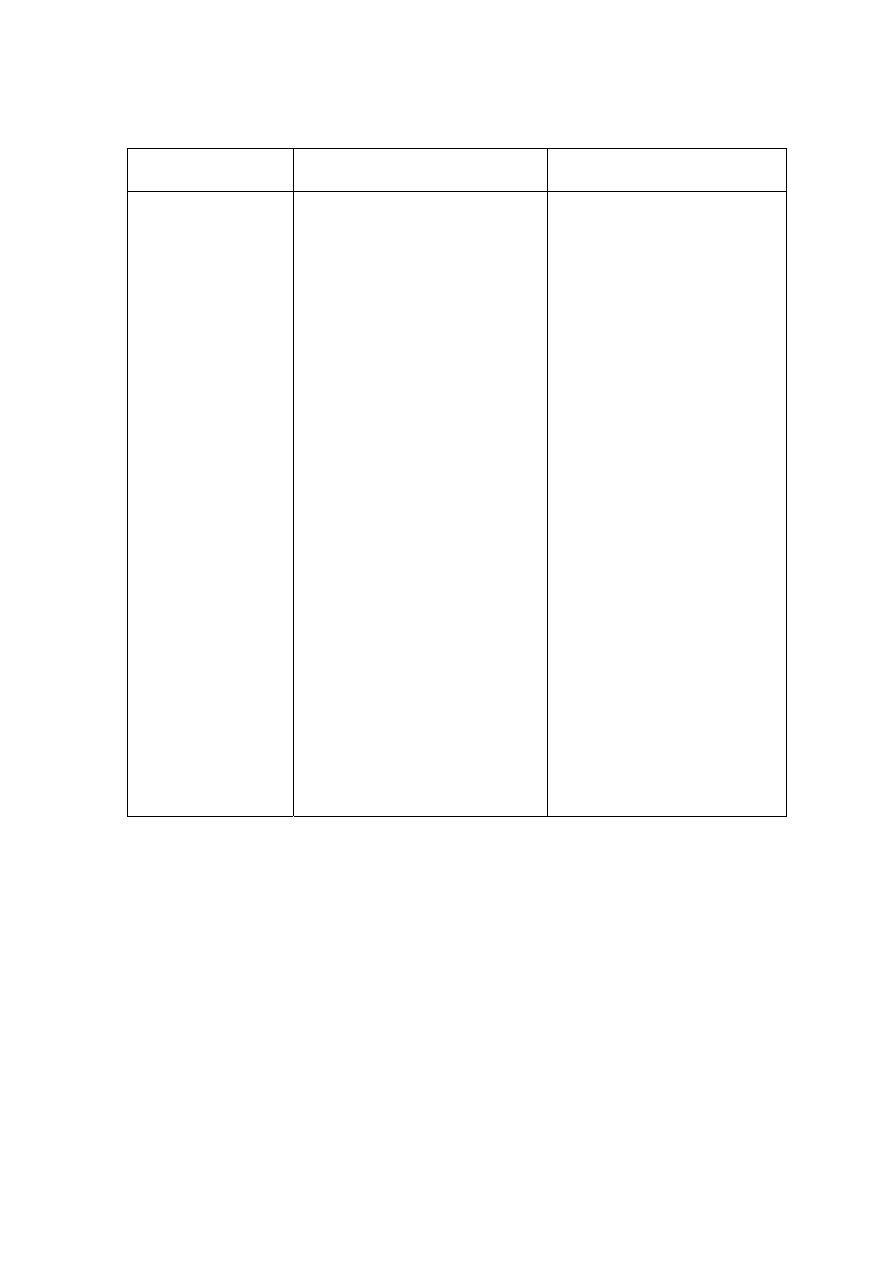

3.2

Diagram Illustrating the Enrichment Procedure

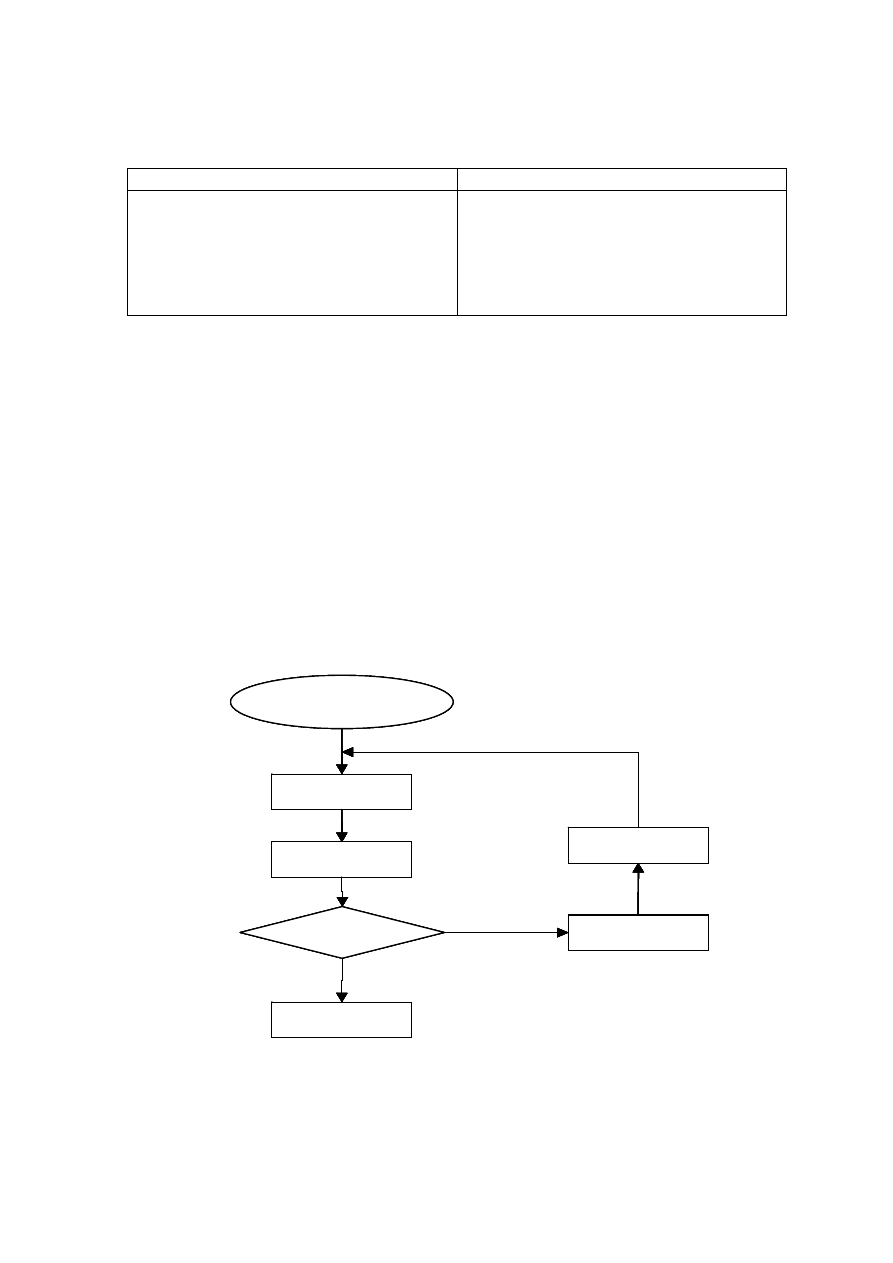

55

3.3

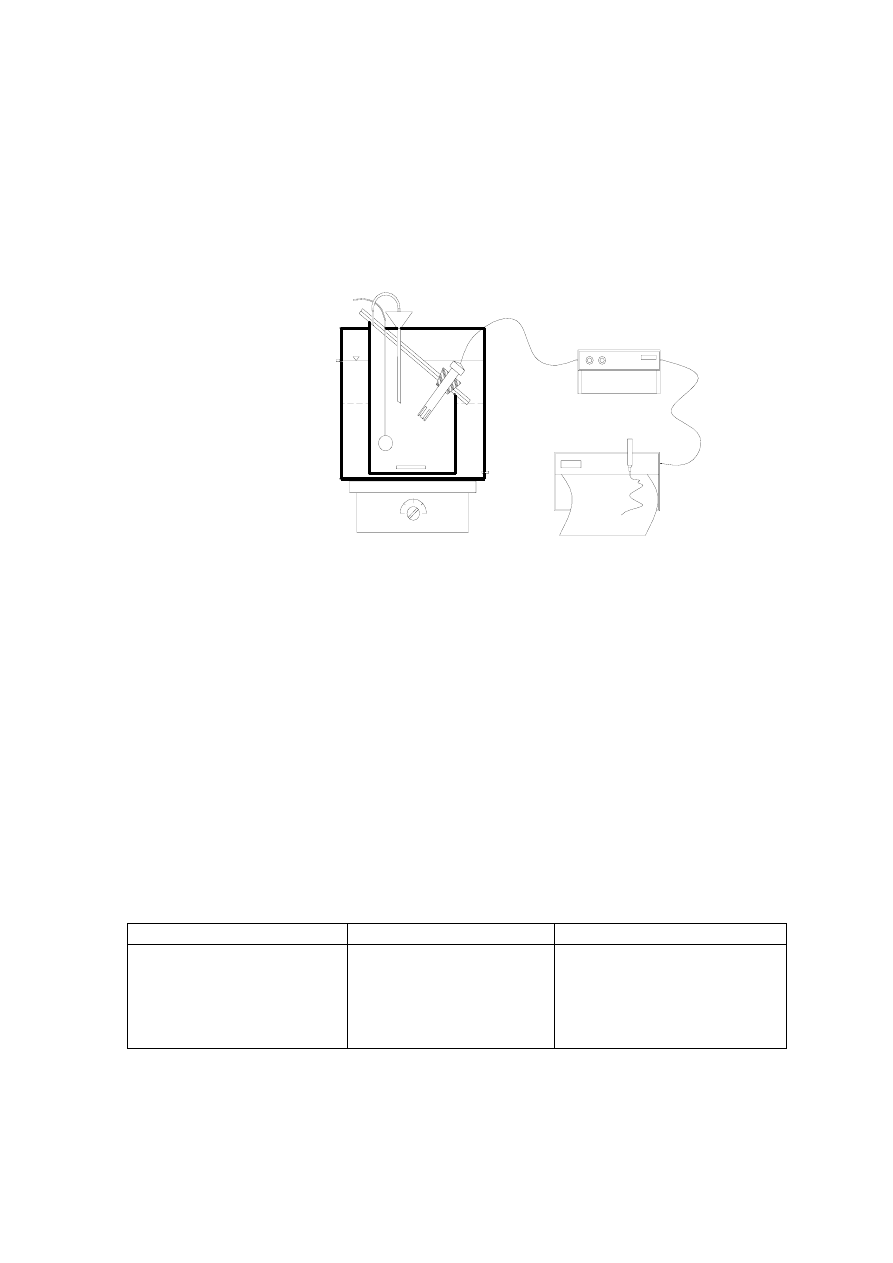

Respirometer

57

3.4

Experiments Conducted to Optimize Ammonia Stripping

59

3.5

Schematic Diagrams of Membrane Bioreactor with and without

Ammonia Stripping

61

3.6

Methodology for Performing Molecular Weight Cut-off Distribution

63

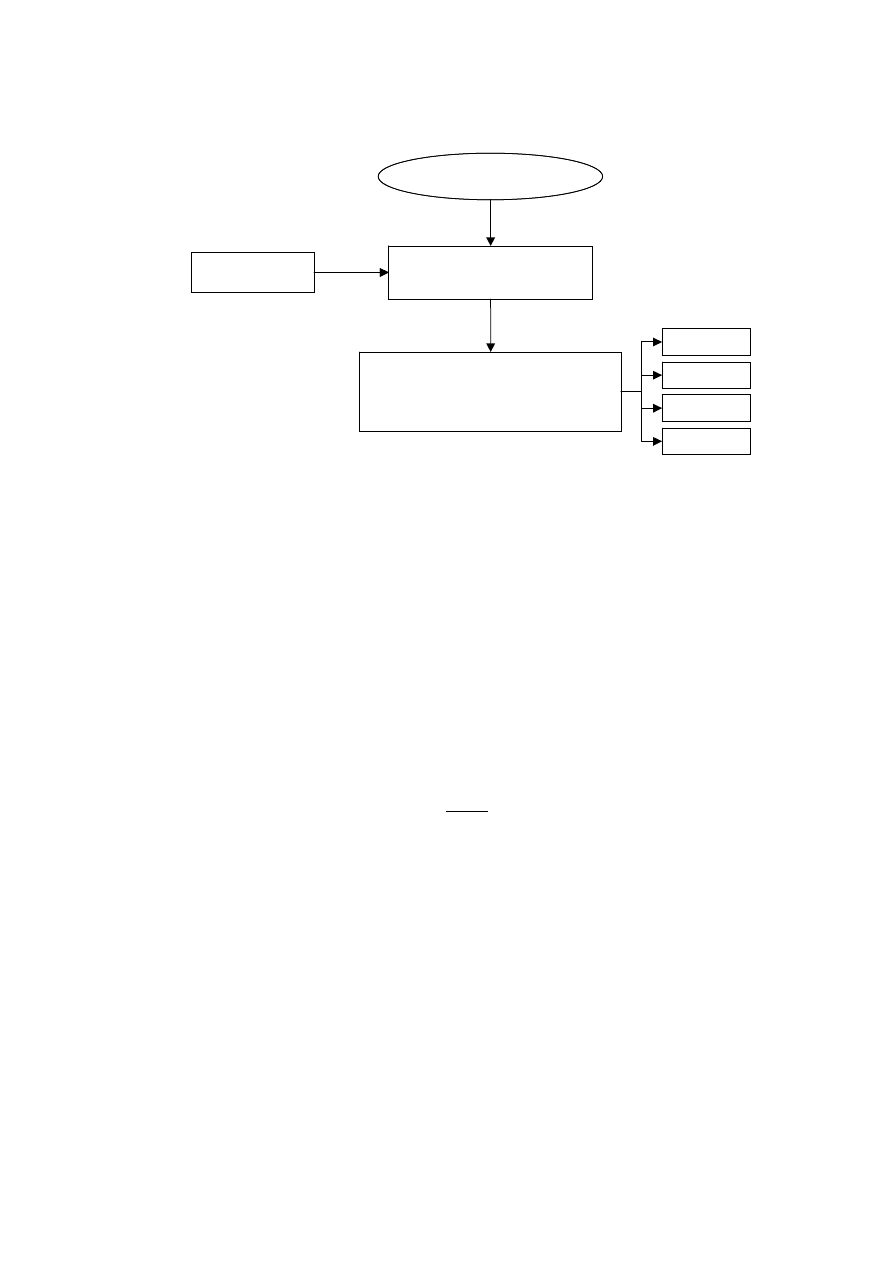

3.7 Flowchart Showing Ammonia Stripping Coupled MBR Process

65

4.1

Variation in F/M and COD Removal Efficiency in Yeast Sludge

69

4.2

Variation in F/M and COD Removal Efficiency in Bacterial Sludge

69

4.3

Increase in Biomass during Acclimatization of the Bacterial Sludge

70

4.4

Increase in Biomass during Acclimatization of the Yeast Sludge

71

4.5

Predominantly Spherical and Egg-shaped Yeasts with Budding in

the Yeast Reactor (x1500)

71

4.6

Bacteria Cells in the Mixed Bacteria Sludge: a) Gram Negative and

b) Gram Positive (x1500)

72

4.7

Specific Growth Rate of Mixed Bacteria Sludge with Increasing

Substrate Concentration

72

4.8

Specific Growth Rate of Mixed Yeast Sludge with Increasing

Substrate Concentration

72

4.9

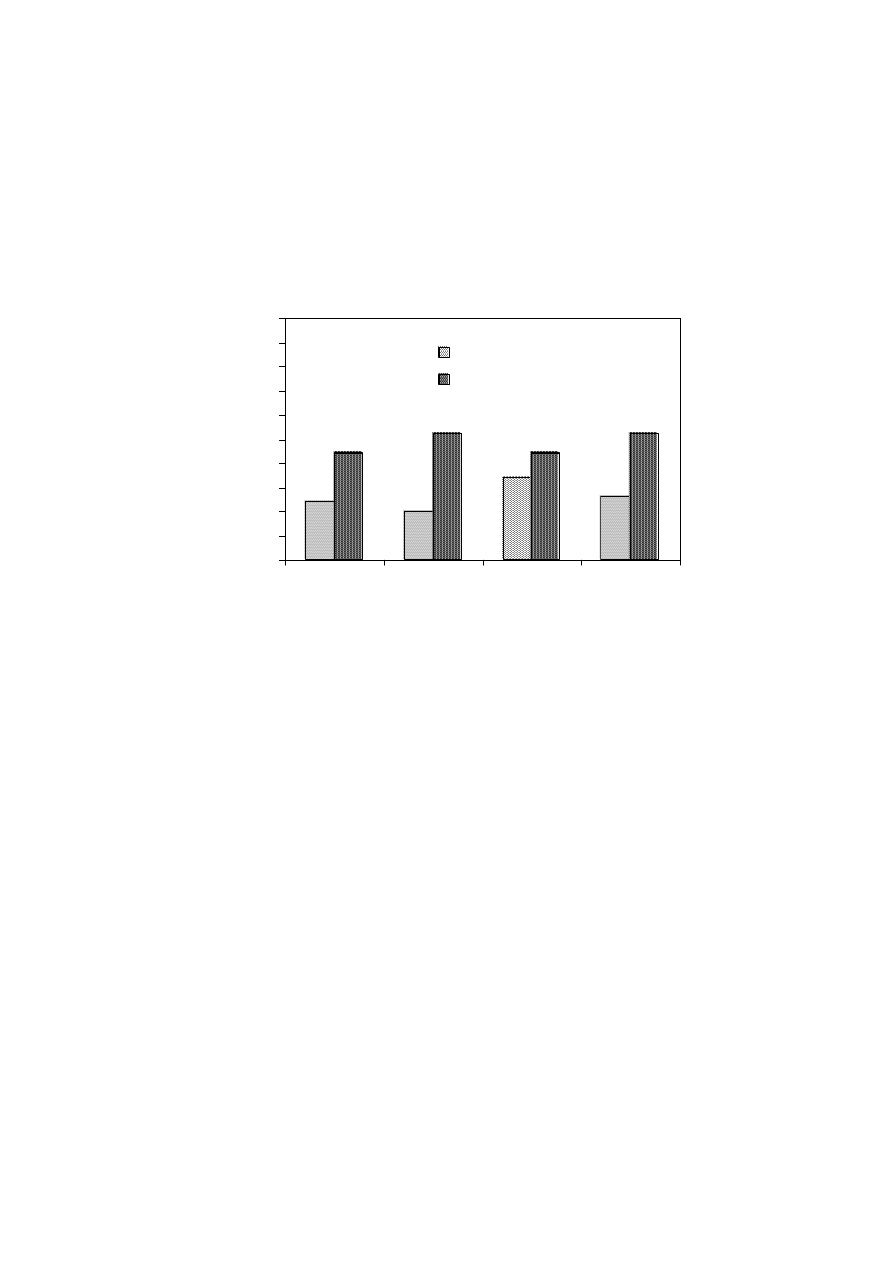

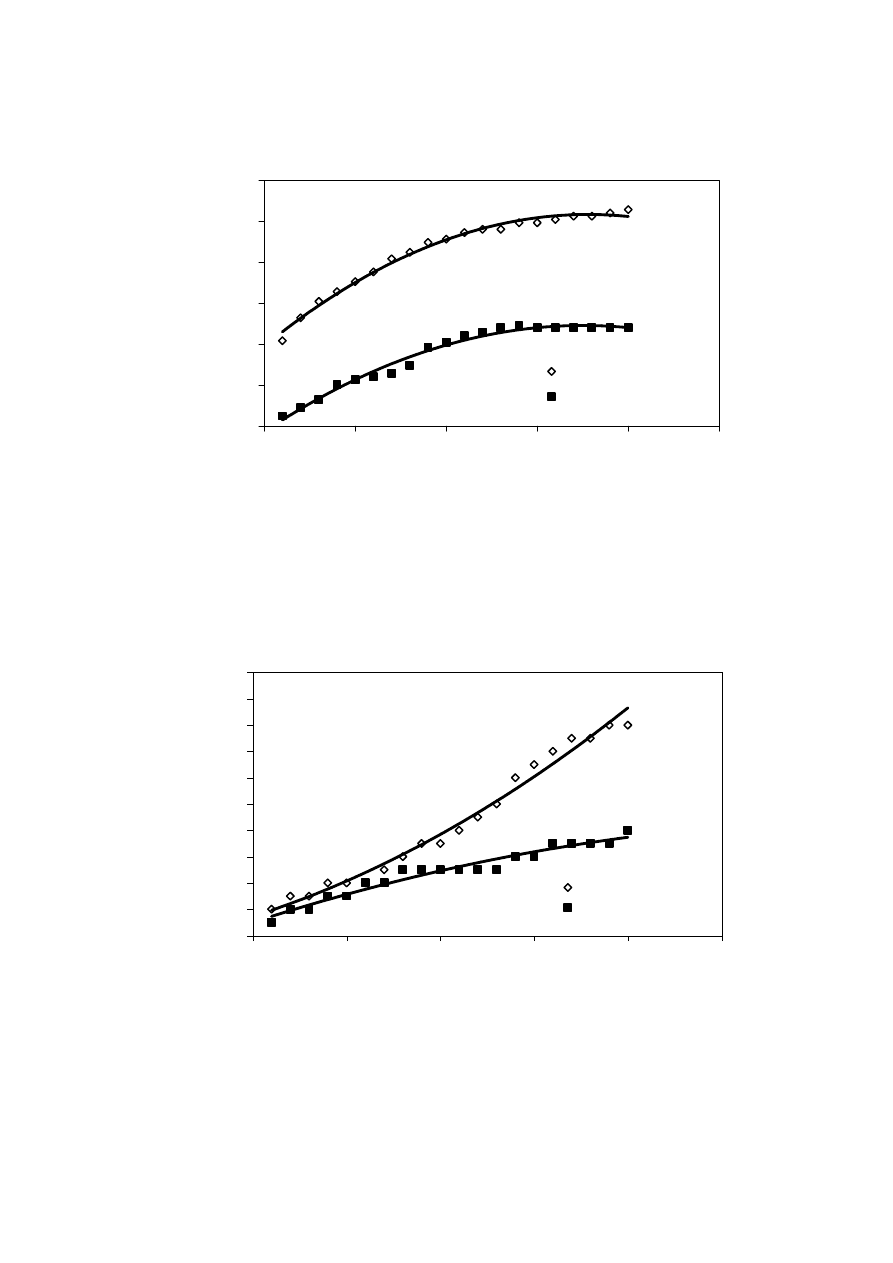

Inhibition of the Yeast and Bacterial Culture with Increasing

Ammonium Chloride Concentration

77

4.10

Inhibitory Effect of Lead in Bacterial Sludge

79

4.11

Inhibition Effect of Lead in Yeast Sludge

80

4.12

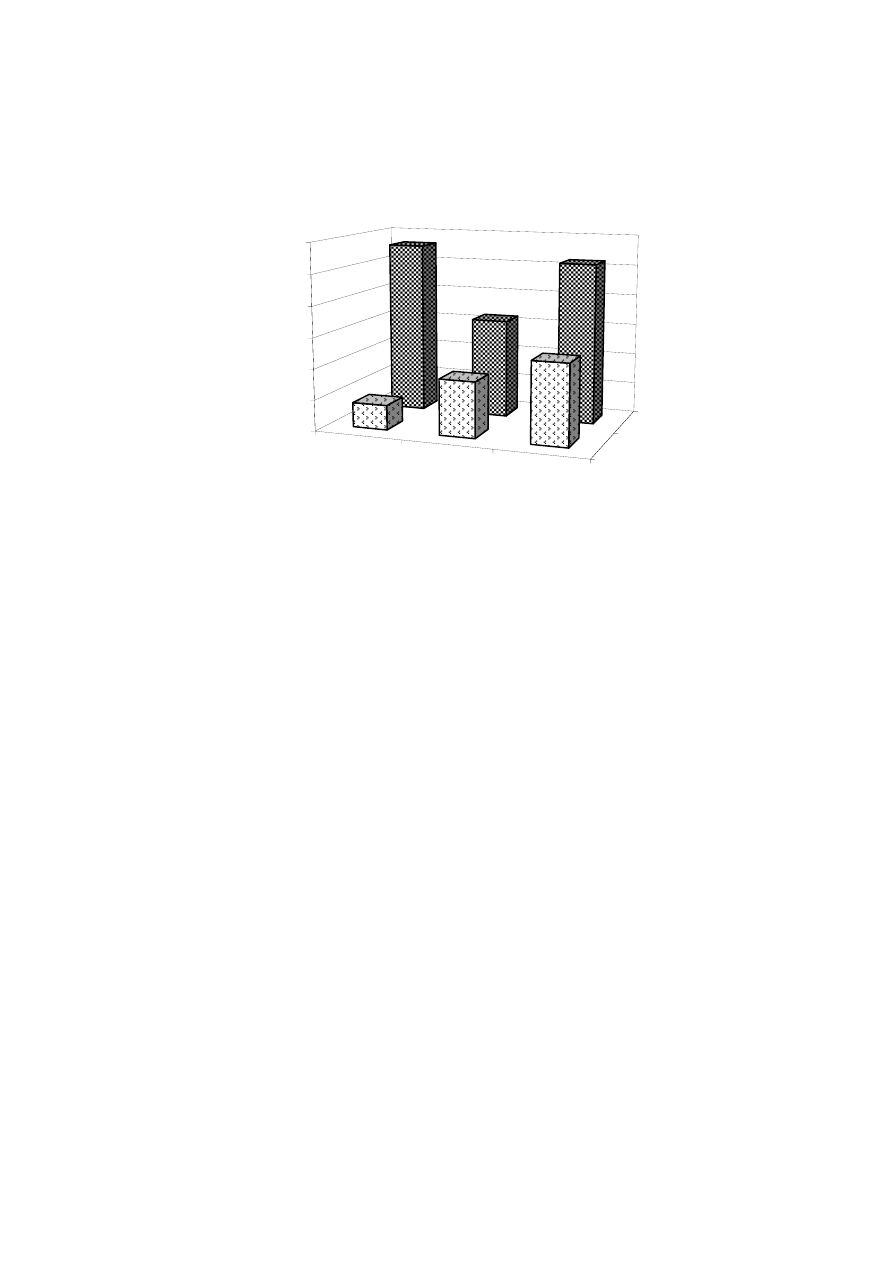

Variation in Transmembrane Pressure with Permeate Flux (a) YMBR

and (b) BMBR

81

4.13

Variation in Organic Load with HRT

83

4.14

Variation in MLSS in the MBR Systems

83

4.15

Variation in pH in the MBR Systems

84

xi

4.16

COD Concentration in the Influent and Effluent in the BMBR and

YMBR at Different HRT

84

4.17

COD Removal Efficiency in the BMBR and YMBR at Different HRT

85

4.18

Variations in COD Removal Rate as a Function of F/M Ratio

86

4.19

TKN Removal Efficiency in the YMBR and BMBR with HRT

87

4.20

Cleaning of membranes in the YMBR and BMBR system in

relation to TMP

90

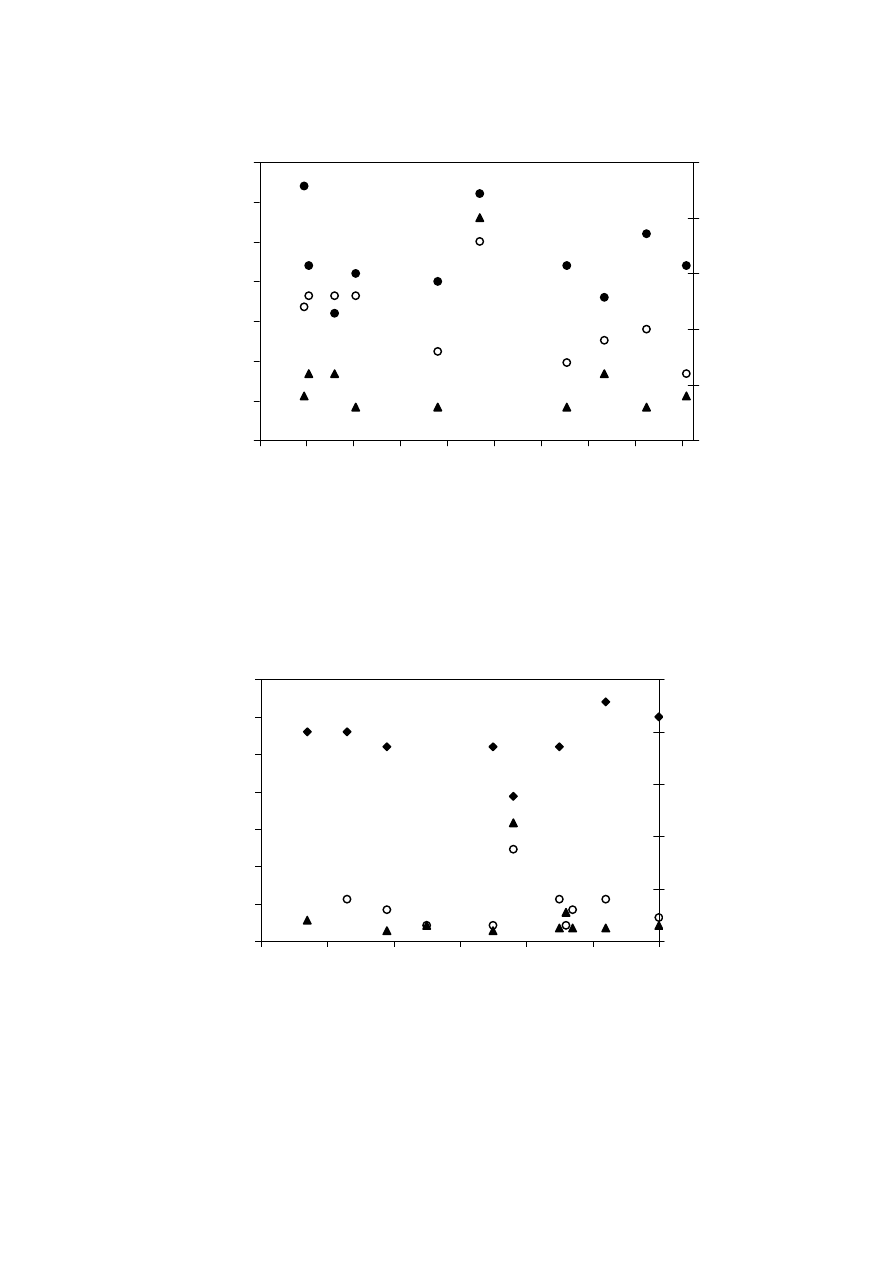

4.21

Variation in the Ammonia Removal Efficiency with pH

93

4.22

Ammonia Removal Efficiency with Varying Velocity Gradient and pH

93

4.23

Trans-membrane Pressure Variation in MBR Process for Ammonia

Stripped Leachate Treatment

96

4.24

Variation in COD at 16 and 24 h HRT

98

4.25

Variation in MLSS at 16 and 24 h HRT

98

4.26

COD Removal with and without Ammonia Stripping at 16 and 24 h HRT 99

4.27

Expected and Actual Improvement in COD Removal with Ammonia

Stripping in the YMBR and BMBR Systems

100

4.28

BOD in the BMBR and YMBR Effluent at 16 h HRT

101

4.29

BOD in the BMBR and YMBR Effluent at 24 h HRT

101

4.30

BOD Removal Efficiency in the BMBR and YMBR Systems

102

4.31

BOD/COD of the BMBR and YMBR Effluent

102

4.32

Influent and Effluent Nitrogen Content in BMBR at (a) 16 h HRT and

(b) 24 h HRT

103

4.33

Influent and Effluent Nitrogen Content in YMBR at (a) 16 h HRT and

(b) 24 h HRT

104

4.34

Overall TKN Removal in BMBR and YMBR with and without

Ammonia

Stripping

105

4.35

TKN Removal in MBR Process at 16 and 24 h HRT

106

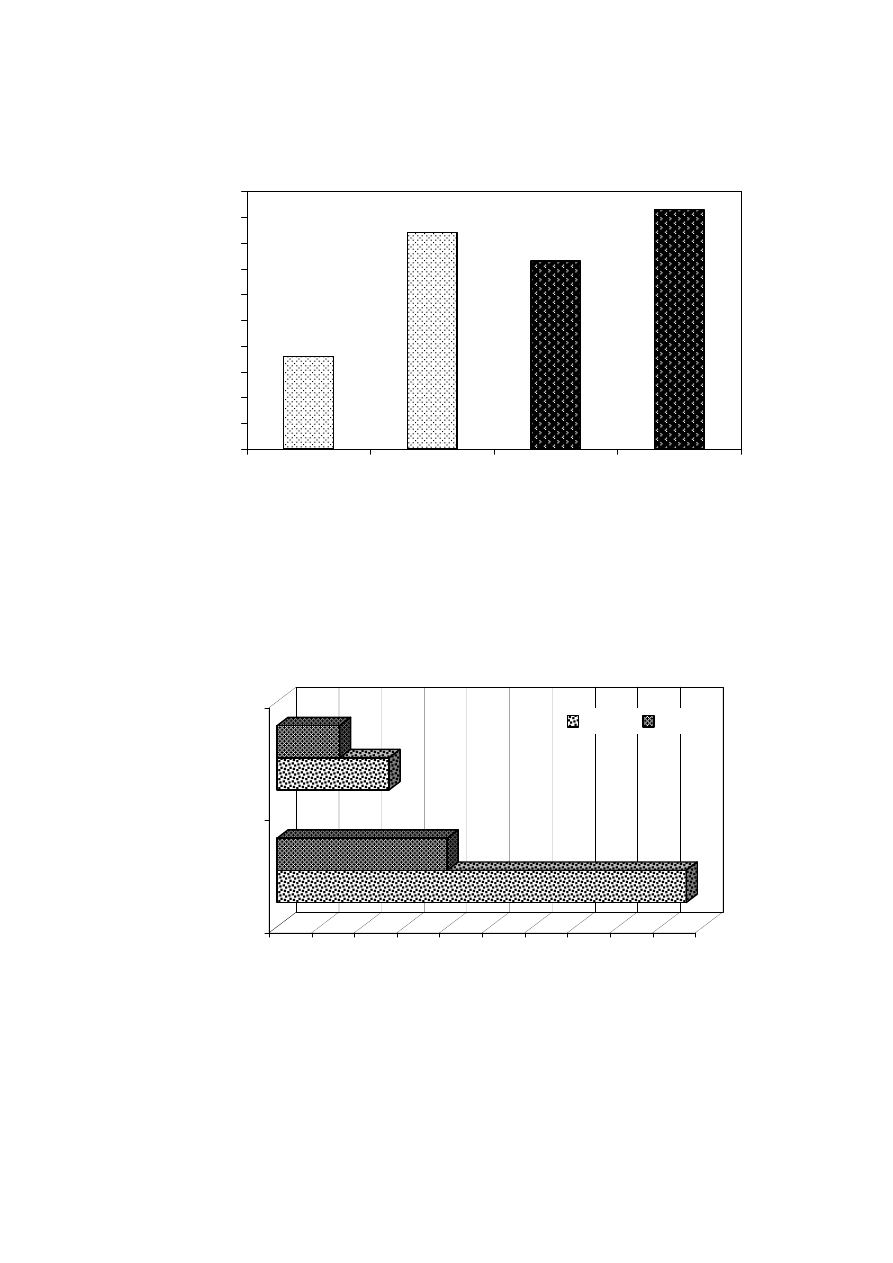

4.36

Change of OUR at Different Time Period for Leachate Sample

107

4.37

20 Days BOD of the Raw Leachate and Stripped Leachate

109

4.38

20 Days BOD of the YMBR and BMBR Effluents

109

4.39

Molecular Weight Cut-off of Raw Leachate, Stripped Leachate,

Bacterial and Yeast Effluents

111

4.40

Percent Contribution of Various Molecular Weight Compounds to

the Total COD

111

4.41

Molecular Weight Cut-off of Leachate (a) COD (mg/L) (b) COD (%)

113

4.42

Molecular Weight Cut-off of Leachate (a) BOD (mg/L) (b) BOD (%)

114

xii

List of Abbreviations

AAS

Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer

AnSBR

Anaerobic Sequencing Batch Reactors

AOX

Adsorbable

Organic

Halogens

AS

Activated

Sludge

BACFB Biological

Activated

Carbon Fluidized Bed Process

BOD

Biochemical Oxygen Demand

BMBR

Bacterial Membrane Bioreactors

C Carbon

cm

Centimeter

COD

Chemical Oxygen Demand

CST

Capillary Suction Time

d

Day

Da

Daltons

DO

Dissolved

Oxygen

DOC

Dissolved Organic Carbon

DSVI

Diluted Sludge Volume Index

EMBR

Extractive Membrane Bioreactor

EPS

Extracellular Polymeric Substances

F/M

Food/Microorganism

ratio

FS

Fixed

Solids

g

Gram

G

Mean velocity gradient

GAC

Granular Activated Carbon

h Hour

HRT

Hydraulic Retention Time

J Permeate

flux

k

Substrate removal rate

kDa

Kilo

Daltons

kg Kilogram

kPa

Kilo

Pascal

kWh

Kilowatt-hour

k

d

Endogenous decay coefficient

k

e

Mean reaction rate coefficient

K

s

Half-velocity

constant

L Liter

m Meter

m

2

Square

meter

m

3

Cubic

meter

m

3

/d

Cubic meter per day

mg/L

Milligram per liter

min

Minute

MAACFB Microorganism

Attached

Activated Carbon Fluidized Bed Process

MABR

Membrane Aeration Bioreactors

MBR

Membrane Bioreactor

MF

Microfiltration

MLSS

Mixed Liquor Suspended Solids

MLVSS

Mixed Liquor Volatile Suspended Solids

MW

Molecular

Weight

xiii

MWCO Molecular

Weight

Cut-off

MWW

Municipal Wastewater

N Nitrogen

NF

Nanofiltration

NH

3

-N

Ammonia Nitrogen

NH

4

-N

Ammonium Nitrogen

NO

2

-N

Nitrite Nitrogen

NO

3

-N

Nitrate Nitrogen

NOM

Natural Organic Matter

OLR

Organic Loading Rate

OUR

Oxygen Uptake Rate

P Phosphorus

Pa Pascal

PAC

Powder Activated Carbon

PS

Pathumthani Landfill Site

R Filtration

resistance

R

c

Resistance due to cake layer

R

m

Intrinsic

resistance

R

n

Resistance due to irreversible fouling

R

t

Total

resistance

RBC

Rotating Biological Contactor

RIS

Ram-indra

Transfer

Station

RO

Reverse

Osmosis

rpm

Rotations per minute

s Seconds

S

o

/X

o

Substrate/Biomass ratio

S

s

Readily

biodegradable

organics

SBR

Sequencing

Batch

Reactor

SCBP

Suspended Carrier Biofilm Process

SD

Standard

Deviation

SRT

Sludge Retention Time

SS

Suspended

Solids

SVI

Sludge Volume Index

T Temperature

TDS

Total Dissolved Solid

TOC

Total Organic Carbon

TKN

Total Kjedahl Nitrogen

TMP

Transmembrane

Pressure

TS

Total

Solids

TVS

Total Volatile Solids

U

Substrate Utilization Rate

UASB

Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket

UF

Ultrafiltration

USB/AF

Upflow Hybrid Sludge Bed/Fixed Bed Anaerobic

UV

Ultraviolet

VFA

Volatile Fatty Acid

VLR

Volumetric

Loading

Rate

VS

Volatile

Solids

VSS

Volatile Suspended Solids

X

s

Slowly biodegradable organics

xiv

Y Yield

coefficient

YMBR

Yeast Membrane Bioreactor

Ө

c

Solid retention time

o

C Degree

Celsius

∆P

Transmembrane Ppessure

µ Vicosity

µm

Micrometer

µ

max

Maximum specific growth rate

µS/cm

Microsiemens per centimeter

1

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Background

Rapid industrialization and urbanization has resulted in an immense environmental

degradation. Population growth and poor environmental management practices have led to

deterioration of environmental quality in most of the developing countries. The

composition of the domestic refuse has radically changed in character over the last fifty

years, due to the rise of an affluent society. In recent years, solid waste management has

gained focus in many countries. Source reduction, reuse and recycling of waste,

composting, incineration and landfill disposal are few of the solid waste management

approaches practiced in different countries. The suitability of these approaches differs from

place to place. Municipal solid waste disposal in the landfill is the most common, cheap

and easiest municipal solid waste management practice followed throughout the world.

However, landfill requires a close environmental engineering surveillance in its design and

operation as it is likely to generate leachate which would potentially contaminate nearby

groundwater and surface water. With the changing nature of domestic refuse composition

over the years, the proportion of refuse available for decomposition has greatly increased

and thus the organic strength of the leachate has increased, resulting in its greater potential

to pollute water. A need exist to focus on the environmental problems concerned with

domestic landfill disposal to protect the environment and prevent adverse health affects.

Surface water that percolates through the landfill and leaches out organic and

inorganic constituents from the solid waste is termed leachate. Landfill leachate production

starts at the early stages of the landfill and continues several decades even after landfill

closure. Landfill leachate is mainly generated by the infiltrating water, which passes

through the solid waste fill and facilitates transfer of contaminants from solid phase to

liquid phase. Due to the inhomogeneous nature of the waste and because of the differing

compaction densities that will be encountered, water will be able to percolate through and

appear as leachate at the base of the site. If no remedial measures are taken to prevent

continual inputs of water to the wastes, this could pose adverse environmental impacts.

Landfill leachate is high strength wastewater which contains high concentrations of

organic matter and ammonium nitrogen. There is a fluctuation in the composition of

organic, inorganic and heavy metal components in the leachate making them more difficult

to be dealt with. The composition depends on the landfill age, the quality and quantity of

solid waste, the biological and chemical processes occurring in the landfill, and the amount

of precipitation and percolation. When the leachate containing high strength organic matter

and ammonia is discharged without treatment, it can stimulate algae growth through

nutrient enrichment, deplete dissolved oxygen, and cause toxic effects in the surrounding

water environment. Landfill design and operation have a major impact and influence on the

leachate generation. This leachate varies from landfill to landfill and over time and space in

a particular landfill with fluctuations apparent over short and long-term periods due to

climatic, hydrogeology and waste composition variations (Keenan, et al., 1984). Generally,

leachate contaminants are measured in terms of chemical oxygen demand (COD) and

biological oxygen demand (BOD), halogenated hydrocarbons and heavy metals. In

addition, leachate usually contains high concentrations of inorganic salts - mainly sodium

2

chloride, carbonate and sulfate and is dependent on the waste composition land-filled. An

average fresh domestic refuse leachate can have a BOD of around 15,000 mg/L. When

compared to an average raw sewage BOD of 200 mg/L, it can be seen that landfill leachate

is around 75 times as strong in terms of its polluting potential.

Sufficient means have to be evolved to deal with landfill leachate so that its impact

can be minimized. Leachate treatment and prevention or minimization of leachate

generation is primarily the two prime options available for landfill leachate management.

Disposal of the leachate in the sewer is an attractive option, but the variation in the quality

of the sewage and leachate and remoteness of the landfill sites make this option difficult

practically. Leachate treatment has inevitably become a much more widespread

requirement at landfills. It is a technology which has only developed in 1980 in the UK,

but is now advancing rapidly as experience is being gained on full scale landfills

(Robinson, et al., 1992).The main environmental problem experienced at landfills has

resulted from a loss of leachate from the site and the subsequent contamination of

surrounding land and water. Improvements in landfill engineering has been aimed at

reducing leachate production, collecting and treating leachate prior to discharge and

thereby limiting leachate infiltration to the surrounding soil (Farquhar, 1989). However a

need exists to develop reliable, sustainable options to effectively manage leachate

generation and treatment. In designing a leachate treatment scheme, the process must

reflect the possibility that treatment techniques which work well for a young leachate may

become wholly inadequate as the landfill age increases.

There are difficulties concerned with the treatment of the leachate. First, the

variability and strength of the leachate have important waste treatment application. Second,

the changes encountered from landfill to landfill are such that waste treatment technology

applicable at one site may not be directly transferable to other location. Third, fluctuations

in the leachate quality which occur over both short and long interval must be accounted for

in the treatment design and long interval must be accounted for in the treatment design.

Current treatment practices in developed countries advocate leachate minimization

by operating landfills as dry as possible; this poses the problem of long-term landfill

stabilization. The alternative of operating the landfill as wet as possible by leachate re-

circulation does address the problem of leachate treatment by reducing organics. However,

this method does not prove effective in treating “hard COD” or refractory compounds and

nitrogen. Therefore, it does not meet municipal discharge standards. Various biological

treatment methods have been employed for the treatment of leachate from municipal solid

waste landfill. Extended aeration systems, sequencing batch reactors and aerated lagoons

can act as robust, stable and reliable means of treating leachate. These treatment systems

were found to be inefficient for leachate containing high strength organic substances and

ammonia nitrogen. In addition, the organic loading and pH are significant in influencing

the growth of nitrifying bacteria in nitrification process (Aberling, et al., 1992; Bea, et al.,

1997; Kabdasli, et al., 2000). Due to high ammonia concentrations in the leachate,

ammonia toxicity and sludge properties are affected in the biological treatment systems. A

reed bed treatment system can also be designed to treat effluent by passing it through the

rhizomes of the reed. However, such treatment systems would not deal satisfactorily

because reed bed are poor in removing ammonia. Additionally, ammonium concentration

as high as approximately 1,000 mg/L of untreated leachate feed, might be directly toxic

(Robinson, et al., 1992). The physical treatment systems used for treatment of the leachate

include activated carbon adsorption, filtration, evaporation; etc. These processes are

3

generally unsuccessful in removal of organic material from the raw leachate. The chemical

methods include coagulation and precipitation and oxidation of the organics. The

disadvantage of the coagulation and precipitation is that large amounts of sludge are

produced which is difficult to manage. Neither biological nor chemical/physical treatment

separately achieves high removal efficiency. Physical-chemical treatment is needed to

remove the metals and hydrolyze some of the organics whilst biological treatment is

necessary for stabilization and degradation of organic matter. Looking into these aspects,

landfill leachate treatment requires some advanced treatment technique, to meet the

required effluent standards.

Membrane bioreactor systems are an example of an emerging advanced leachate

treatment technology. Application of the membrane coupled activated sludge process in

leachate treatment is very promising because of the expected effluent quality. The design

of the membrane bioreactor is becoming more affordable and the equipment more reliable.

Membrane bioreactor systems are suspended growth activated sludge treatment systems

that rely upon the membrane equipment for liquid/solid separation prior to the discharge of

the leachate. Two reasons that exist for the poor removal efficiency of the individual

treatment system is the high percentage of high molecular weight organic material and

ammonium concentration to be removed and biological inhibition caused by the heavy

metal which may be present in the leachate.

Sufficient knowledge about the capability and the performance of membrane

bioreactors plants for leachate treatment is yet to be found. Moreover, membrane systems

are often subjected to clogging and this poses serious problems for operation and

maintenance. In order to reduce the problems of frequent membrane clogging, the

application of yeast culture to treat wastewater can be considered. The membrane

bioreactor system with yeast can be employed to treat the wastewater containing high

amount of dissolved solids, high concentrations of organic matter and other substances,

which are difficult to treat using conventional biological systems.

Consequently, depending on the characteristics of the leachate, a combination of

biological and physio-chemical processes can achieve high removal efficiencies. Thus, the

objective of this study is introducing the emerging technology of membrane bioreactors

and its role in leachate treatment. Thereafter, a rationale has been developed for the

treatment of the leachate produced under tropical conditions of Thailand. The experiments

have been conducted in the laboratory to find the performance of membrane bioreactor

using yeast culture (YMBR) and bacteria culture (BMBR) and coupled with ammonia

stripping for removal of organic substances from the landfill leachate. This treatment

system could act as an innovative approach in the future with regard to the landfill

management practices.

1.2 Objectives of the Study

The objectives of this study are to investigate the performance of membrane

bioreactor using yeast culture and bacteria culture and to examine the prospects of

applying membrane bioreactor in landfill leachate treatment. The specific objectives are as

follows:

4

1. To investigate and evaluate the performance of membrane bioreactor using yeast

culture (YMBR) and bacteria culture (BMBR) for the treatment of landfill leachate

containing high organic and high ammonia concentrations;

2. To investigate and evaluate the performance of ammonia stripping coupled

membrane bioreactor process for the landfill leachate treatment and to compare the

results with the treatment performance without pre-treatment;

3. To evaluate the respiratory inhibition effects of ammonia and lead concentrations on

mixed yeast and mixed bacteria culture;

4. To investigate the potential of ammonia stripping for ammonia removal and examine

the factors influencing the ammonia removal efficiency;

5. To understand the effect of membrane fouling through sludge characteristics.

1.3 Scope of the Study

To achieve the above mentioned objectives, the following tasks are undertaken:

1. Characterization and mixing of leachates obtained from Pathumthani landfill site

(PS) and Ram-indra transfer station (RIS) was done to simulate a medium-aged

leachate. The leachate COD concentration was maintained at 8,000±1,000 mg/L,

BOD/COD ratio at 0.40±0.05, and TKN concentration at 1,900±100 mg/L. This

laboratory simulated leachate was used to evaluate the performance of the treatment

process.

2. The yeast culture membrane bioreactor (YMBR) and bacteria culture based

membrane bioreactor (BMBR) were optimized varying the HRT and MLSS

concentrations. The optimum operational condition was evaluated in terms of organic

and TKN removal efficiencies and membrane filtration performance.

3. The removal of ammonia through ammonia stripping was carried out by varying the

pH, gradient velocity and contact time. The process efficiency was evaluated in

terms of ammonia removal efficiency. After the optimization of the operating

conditions of the ammonia stripping and the membrane bioreactor, the optimum

conditions were used to assess the efficiency of the membrane bioreactor using the

bacterial and yeast culture along with the ammonia stripping.

4. To evaluate the inhibition effects of ammonium (NH

4

-N) and lead (Pb) on mixed

yeast and mixed bacteria sludge. The NH

4

-N concentration was varied from 200 to

2,000 mg/L in both sludge. The lead nitrate (Pb(NO

3

)

2

) concentration in the bacteria

system was varied from 20 to 100 mg/L while in the yeast system was varied from 2

to 25 mg/L. The inhibitory effect was measured in terms of oxygen uptake rate

(OUR) using respirometric method.

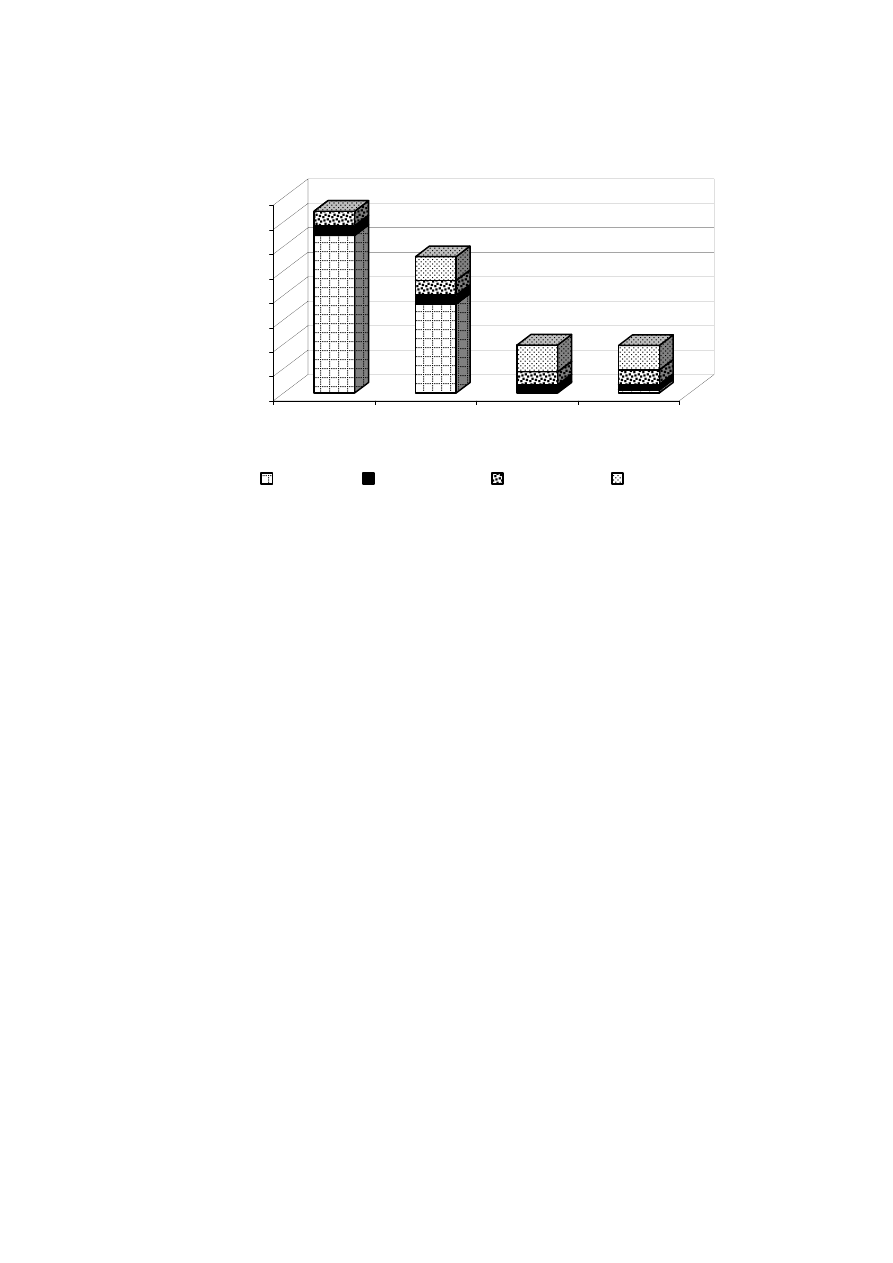

5. The sludge characteristics were analyzed to understand their relationship with the

EPS formation in the membrane bioreactor. The molecular weight cut-off was also

done in the sludge along with the fraction causing COD.

5

Chapter 2

Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

A landfill is any form of waste land, ranging from an uncontrolled rubbish "dump" to

a full "containment" site engineered with high standards to protect the environment. The

landfill is the most economical form of solid waste disposal as adverse environmental

effects and other risks and inconveniences are minimized, thereby allowing waste to

decompose under controlled conditions until it eventually transforms into relatively inert,

stabilized material (Robinson and Maris, 1983). Most landfills can be operated

satisfactorily for at least some period in their lifetime in this manner and in absence of any

significant negative environmental impact.

Unfortunately, in warmer climates, the increase in leachate production after

precipitation is rapid (Lema, et al., 1988) due to rainfall exceeding the amount which can

be effectively evaporated during winter or rainy seasons. Hence, leachate generation needs

to be controlled and effective leachate treatment options have to be identified in order to

avoid negative impacts caused by the leachate.

A common practice in controlling leachate generation is to control the water

infiltration in the landfill by waste compaction as it reduces the infiltration rate. Further, by

designing water proof covers and growing plants on the soil covers of the waste,

infiltration can be minimized. Figure 2.1 presents a typical engineered landfill. The landfill

leachate characteristic is controlled by solid waste characteristics, moisture content, pH,

redox potential, temperature, etc. The presence of moisture is necessary for the biological

conversions within the landfill and for landfill stabilisation, which occurs when there is

insufficient moisture. Degradation processes within the landfill are also temperature

dependent. The pH and redox potential set the conditions for the different phases of

degradation and biological processes within the landfill. Thus, the microbial composition

within the landfill effectively contributes to the landfill stabilization.

After the initial period of waste placement in a landfill, microbial processes proceed

under anoxic conditions. Hydrolytic and fermentative microbial processes solubilize the

waste components during the acid fermentation phase producing organic acids, alcohols,

ammonia, carbon dioxide and other low molecular weight compounds as major products.

This process occurs at a low pH (typically around 5) and is enhanced by the presence of

moisture within the landfill. After several months, the methane fermentation stage occurs.

Methanogenic leachate is neutral in pH and possesses moderate organic compounds which

are not easily degradable and are fermented to yield methane, carbon dioxide and other

gaseous end products (Harmsen, 1983; Farquhar, 1989).

6

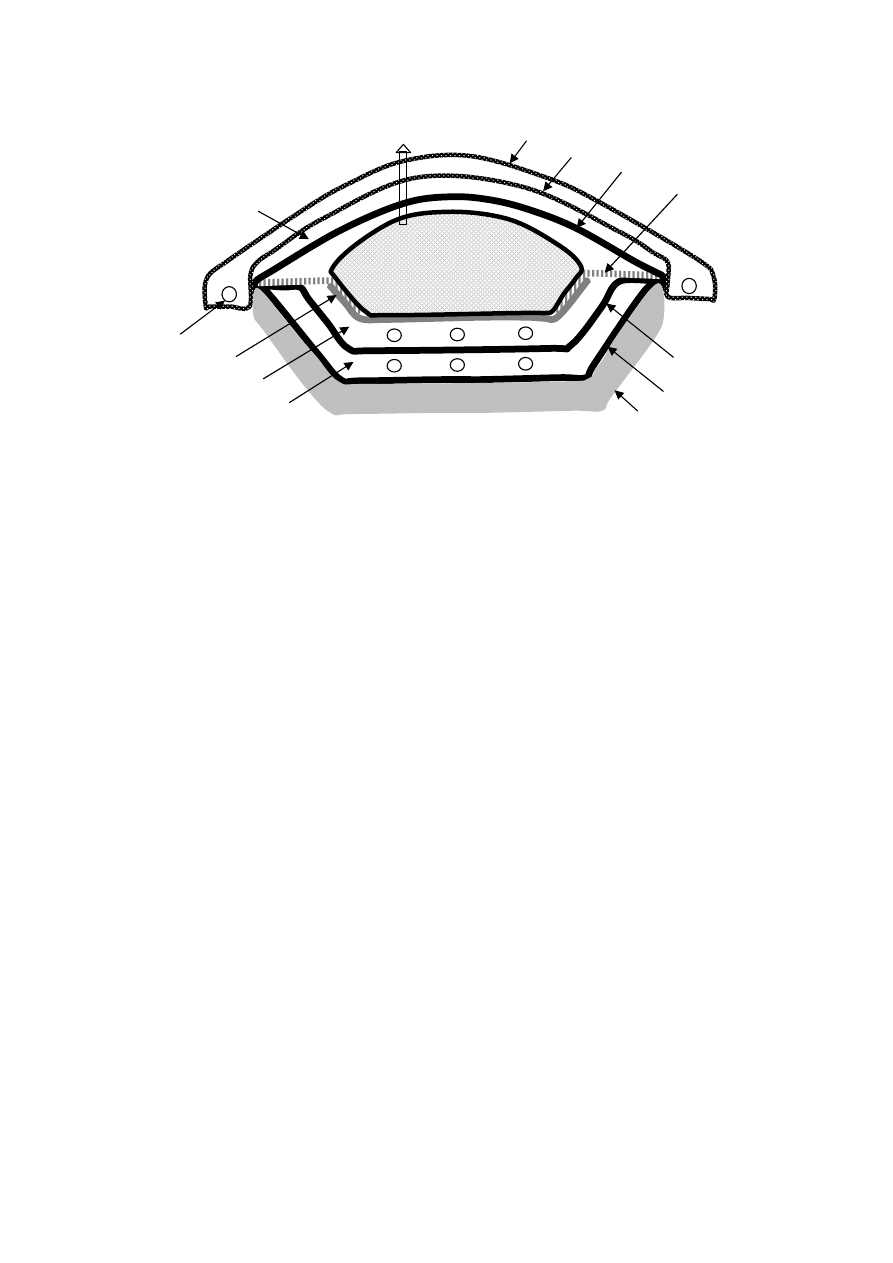

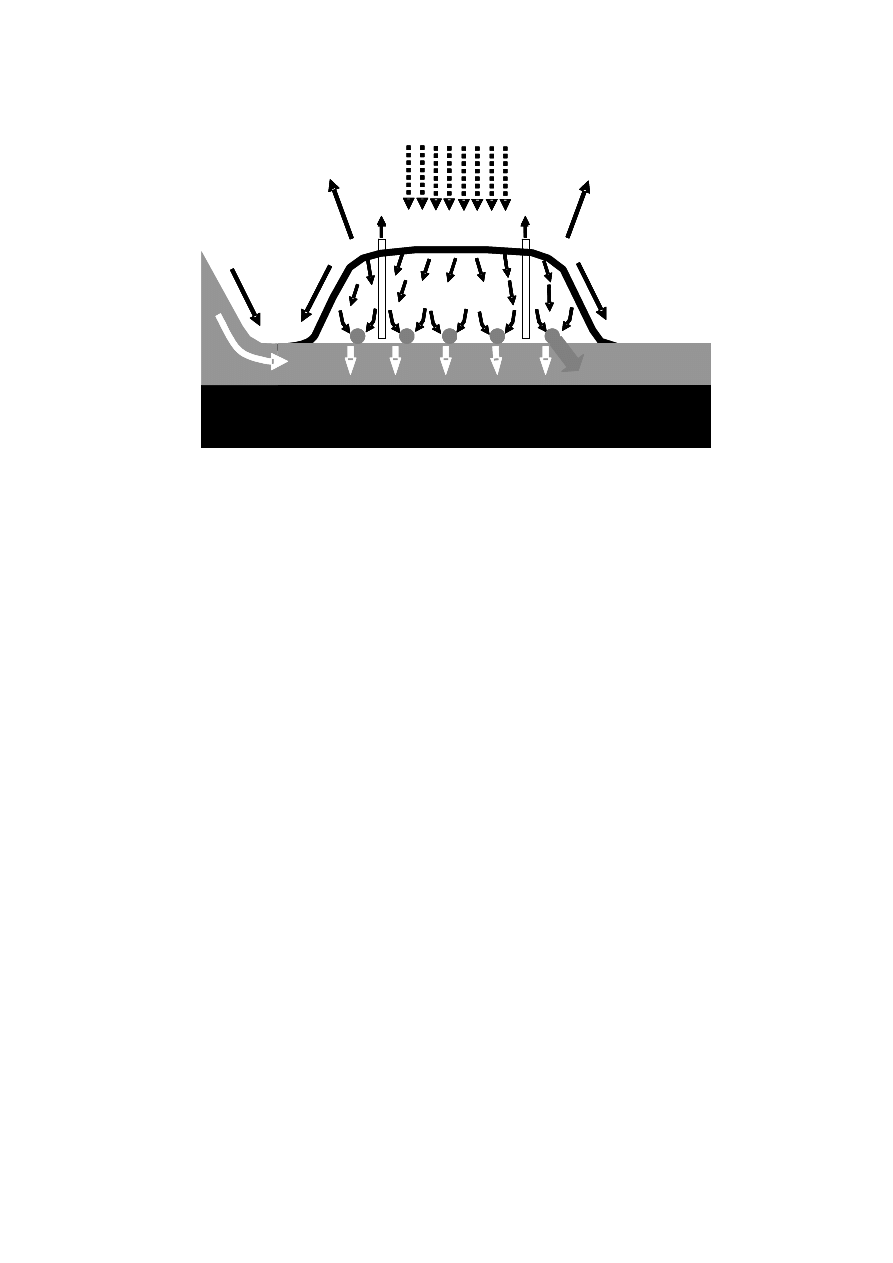

Figure 2.1 Schematic Representation of a Typical Engineered Landfill

2.2 Solid Waste Management Practices

The safe and reliable long-term disposal of solid waste is an important component in

solid waste management. Municipal solid waste consists of inorganic substances such as

boxes, grass clippings, furniture, clothing, bottles, food scraps, newspapers, and appliances

along with organic waste. There are different methods employed in solid waste

management. Few of the management practices are as follows:

(a) Reduction in the exploitation of the resources and the minimization of waste

(b) Increase in recovery/reuse by placing increased responsibility on the producer

(c) Incineration

(d) Composting

(e) Landfilling, etc.

Landfilling or the land disposal is today the most commonly used method for waste

disposal. Landfill has been the most economical and environmentally acceptable method

for the disposal of solid waste throughout the world. Even with the implementation of

waste reduction, recycling and transformation technologies, disposal of solid waste in the

landfill still remains an important component of the solid waste management strategies.

Concerns with the landfilling of solid waste are related to (1) the controlled release

of landfill gases that might migrate off-site and cause odor and other potentially dangerous

conditions, (2) the impact of the uncontrolled discharge of landfill gases on the green

house effect in the atmosphere , (3) the uncontrolled release of leachate that may migrate

down to underlying groundwater or to surface water, (4) the breeding and harboring of

disease vectors in an improperly managed landfills, and (5) the health and environmental

impacts associated with the release of trace gases arising from the hazardous materials.

2.3 Municipal Solid Waste Landfill

Perimeter

Collection Pipe

Low Permeability Soil

Collection

Pipes

Collection

Pipes

Drainage

Layer

Gas Vent

Solid waste

Lower Component

(Compacted Soil)

Upper

Component

Top Liner

(FML)

Native Soil Foundation

Filter

Layer

Leachate Collection

System

Leak Detection

System

Protective Soil

or Cover

Barrier Layer

(FML)

Filter Layer

Compacted

soil

Cap Drainage

System

Drainage Layer

Top Soil

Final Soil Cover

7

In the municipal solid waste landfill, biodegradable waste constituents are converted

into intermediates and end products, primarily by initial hydrolysis to intermediate

substrates which support acidogenesis and product are subsequently utilized as precursor

for gas formation during methanogenesis in the five degradation phases (Pohland and

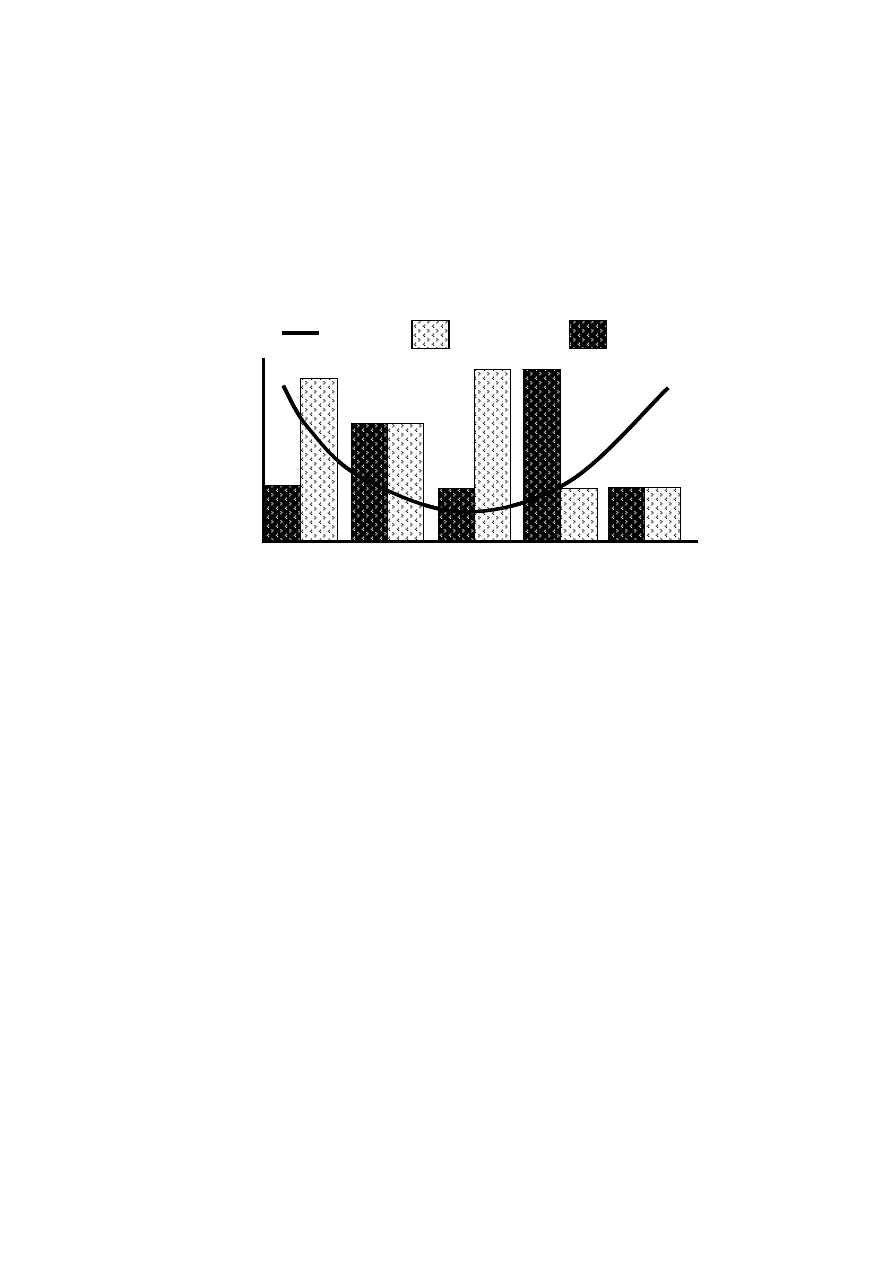

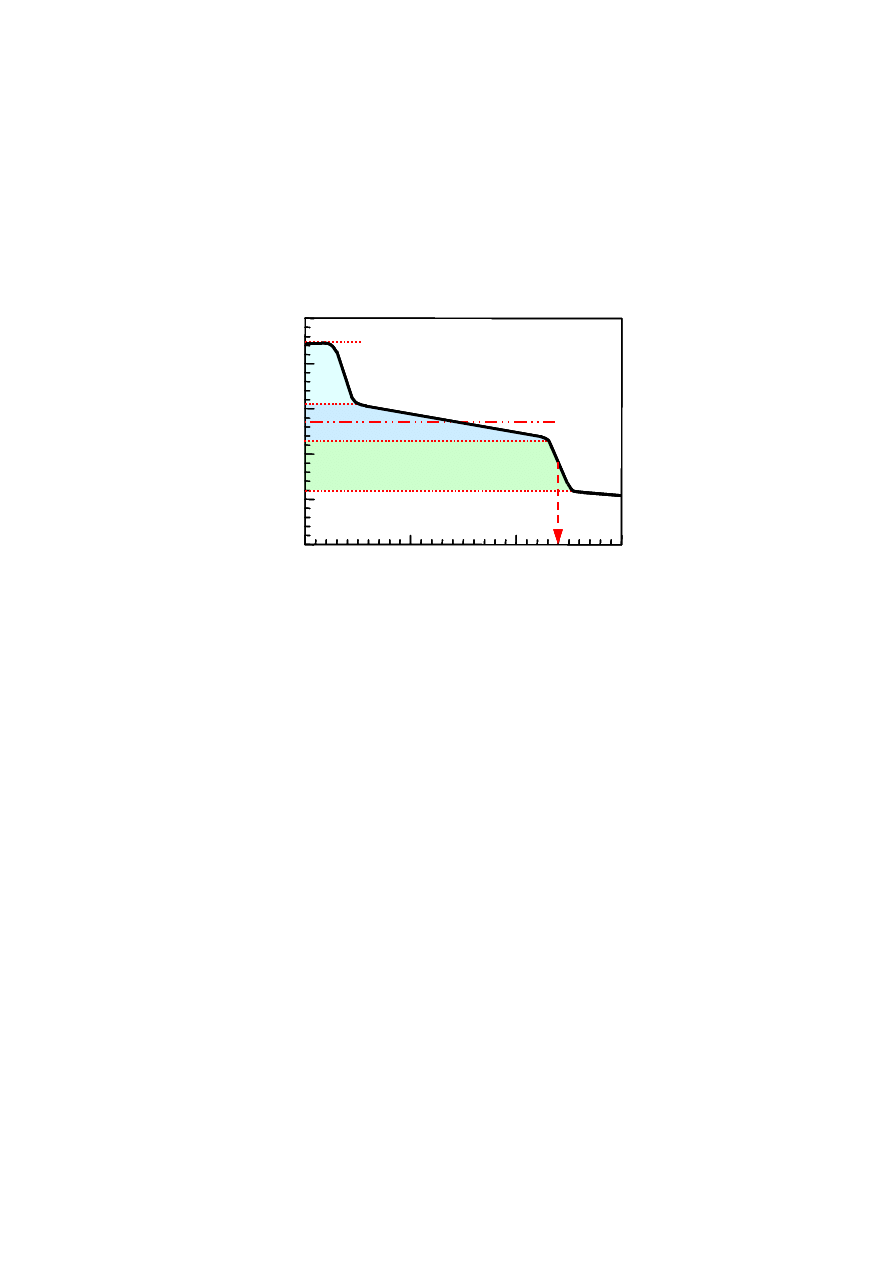

Harper, 1985; Pohland and Kim, 1999). Figure 2.2 represents variation in concentrations of

significant parameters during the five degradation phases.

Figure 2.2 Changes in Significant Parameters during Different Phases of Landfill

Stabilization (Pohland and Harper, 1985)

The trend in the degradation phase may not uniform throughout the landfill since

there are certain regions in the landfill which are dominated by a particular degradation

phase. Hence, the leachate generated is a combination of the products of different

microbial and physico-chemical processes taking place within the landfill.

2.4 Municipal Solid Waste Landfill Leachate

Landfill leachate is a high-strength wastewater formed as a result of percolation of

rainwater and moisture through waste in a landfill. The liquid medium absorbs nutrients

and contaminants from the waste and thus posing hazard to the receiving water bodies.

Leachate contains many substances, depending upon the types of waste disposed into the

landfill. Leachate may be toxic to life or may simply alter the ecology of the stream

watercourse, if not removed by treatment.

Depending on the geographical and geological nature of a landfill site, leachate may

seep into the ground and possibly enter groundwater sources. Though part of the

contaminants from the leachate can be removed by natural processes within the ground,

groundwater contamination can be hazardous as drinking water sources may be affected.

The simplest method of leachate treatment is disposal into the public sewer. However,

as there is considerable difference between the leachate and domestic wastewater

characteristics, the volume of leachate discharged is limited. Further, depending on

Carbon

Emission

Heavy Metal

Emission

Redox

Potential

Concentrat

io

n

Low

High

Aerobic

Acidogenic Methanogenic Oxidation Weathering

Degradation Phases

Carbon

Emission

Heavy Metal

Emission

Redox

Potential

Carbon

Emission

Heavy Metal

Emission

Redox

Potential

Concentrat

io

n

Low

High

Aerobic

Acidogenic Methanogenic Oxidation Weathering

Degradation Phases

8

leachate characteristics, it may be necessary to pre-treat leachate prior to discharge in

wastewater treatment plants so that it does not upset the biological process nor cause any

operational and maintenance problems in the treatment plant. In determining a treatment

scheme for leachate treatment, it is also necessary to determine whether the leachate

effluent meets sewer or water body discharge standards.

2.5 Leachate Composition and Characteristics

During the first few years (< 5 years), the landfill is in acidogenic phase and the

leachate generated is generally referred to as “young” or carbon-based leachate due to the

high concentration of organic carbon present. Landfill greater than 10 years old are

generally in the methanogenic phase and the leachate generated is referred to as “old” or

nitrogen-based leachate (Mavinic, 1998). Table.2.1 gives the characteristic of leachate

present in acidogenic and methanogenic phases.

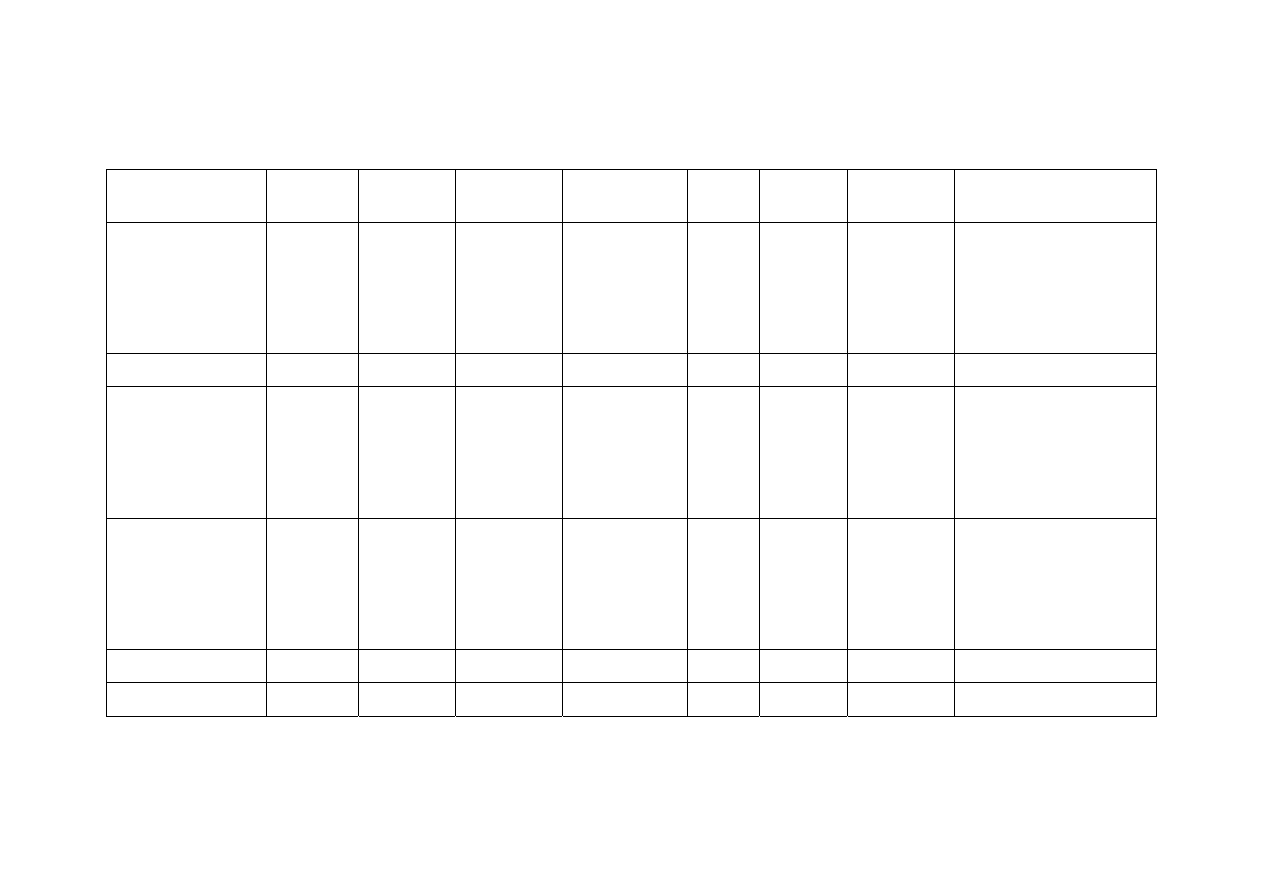

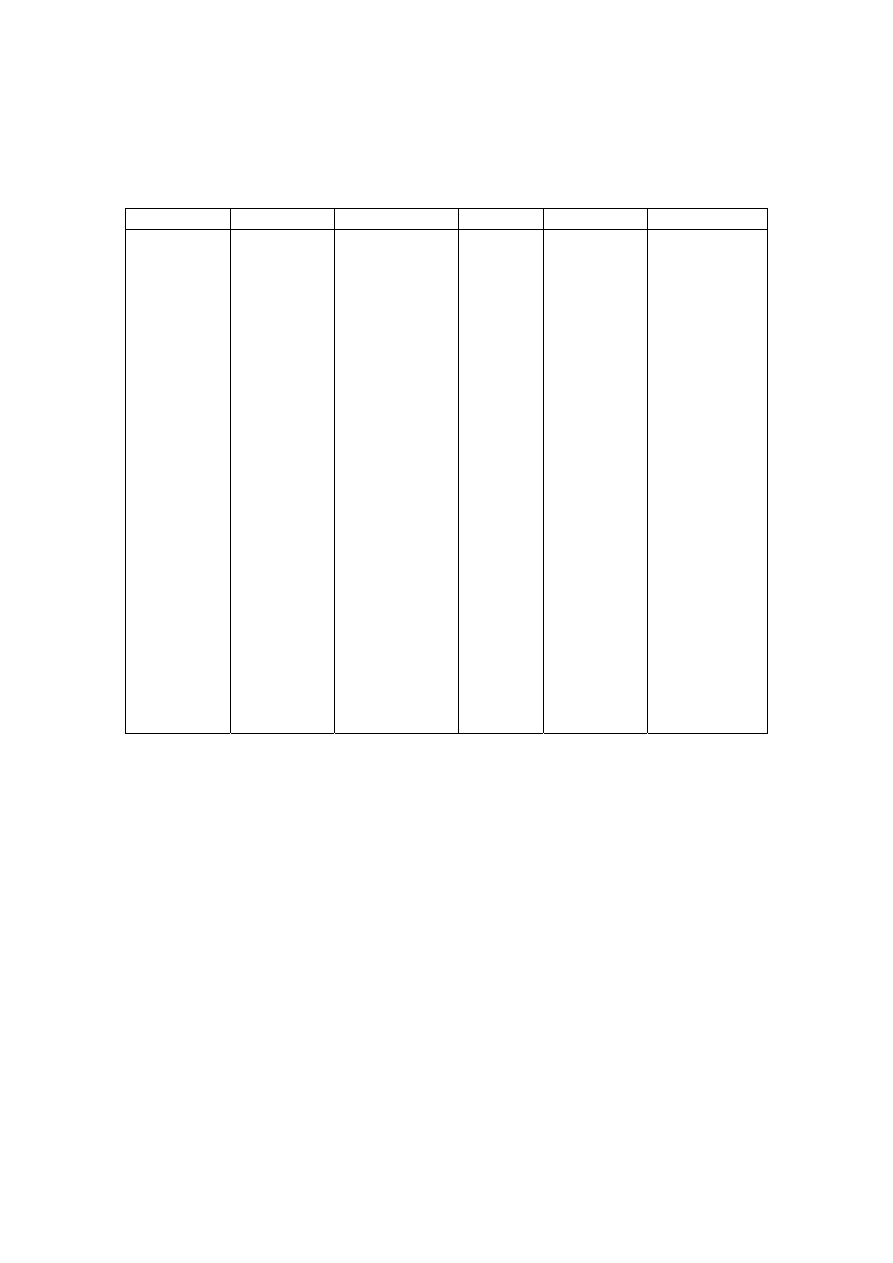

Table 2.1 Leachate Characteristic in Acidogenic and Methanogenic Phase in a Landfill

(Ehrig, 1998)

Parameter Unit

Average Range

Acidogenic Phase

pH

6.1

4.5 to 7.5

BOD

5

mg/L

13,000

4,000 to 40,000

COD

mg/L

22,000

6,000 to 60,000

BOD

5

/COD

0.58

-

SO

4

mg/L

500

70 to 1,750

Ca

mg/L

1,200

10 to 2,500

Mg

mg/L

470

50 to 1,150

Fe

mg/L

780

20 to 2,100

Mn

mg/L

25

0.3 to 65

Zn

mg/L

5

0.1 to 120

Methanogenic Phase

pH

8

7.5 to 9

BOD

5

mg/L

180

20 to 550

COD

mg/L

3,000

500 to 4,500

BOD

5

/COD

0.06

-

SO

4

mg/L

80

10 to 420

Ca

mg/L

60

20 to 600

Mg

mg/L

180

40 to 350

Fe

mg/L

15

3 to 280

Mn

mg/L

0.7

0.03 to 45

Zn

mg/L

0.6

0.03 to 4

The differences in leachate quality can be due to varied reasons, which can be

categorised into four major divisions, namely the waste (type of waste, degree of

decomposition, and possible seasonal variance), landfill environment (phase of degradation,

humidity, temperature etc.), filling technique (compacting, cover, height of landfill layers,

etc.) and sampling (method of analysis and point of sample collection).

The factors affecting the leachate quality is inter-related and affects the overall

variance in leachate quality and characterization. The changes in the BOD/COD,

9

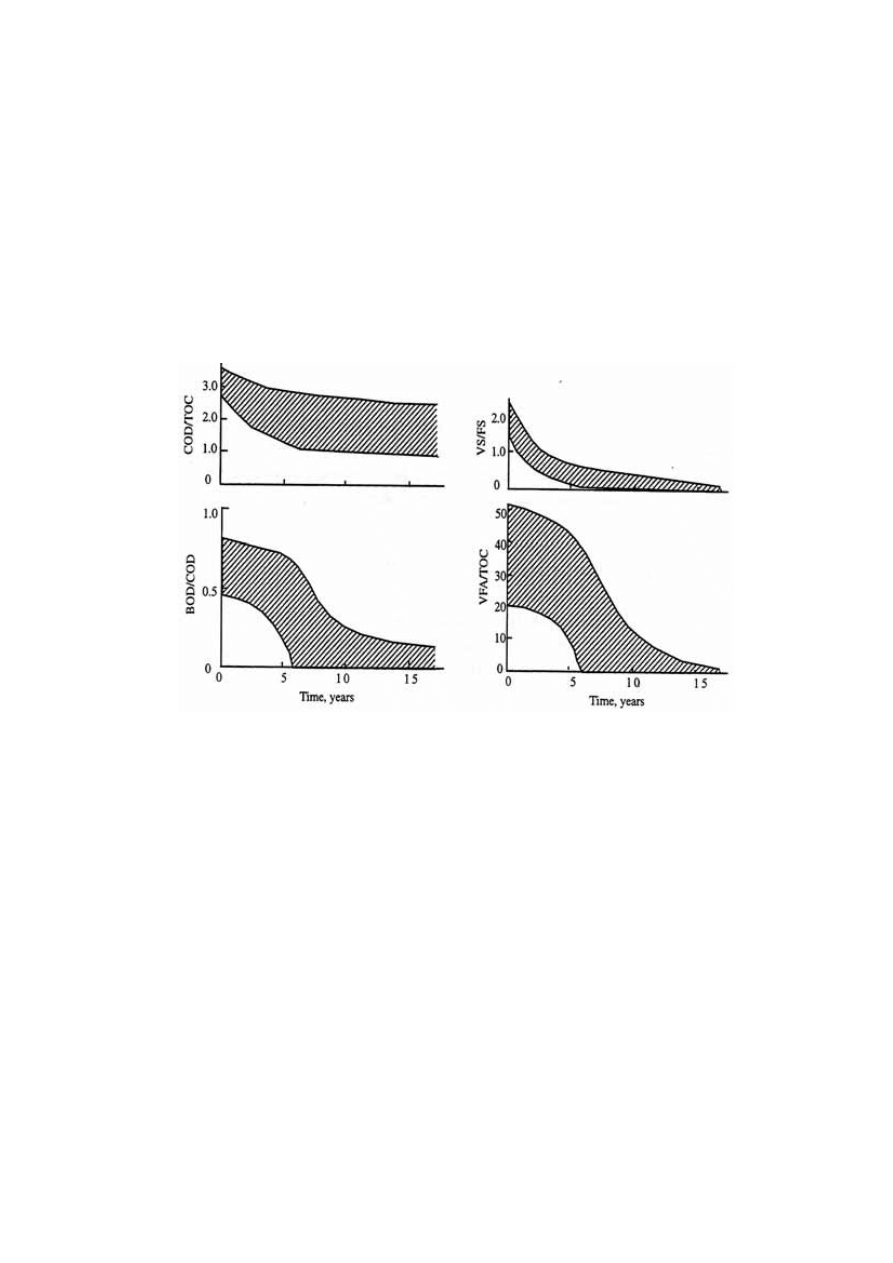

COD/TOC, VS/FS and VFA/TOC ratios of leachate are depends greatly on the age of the

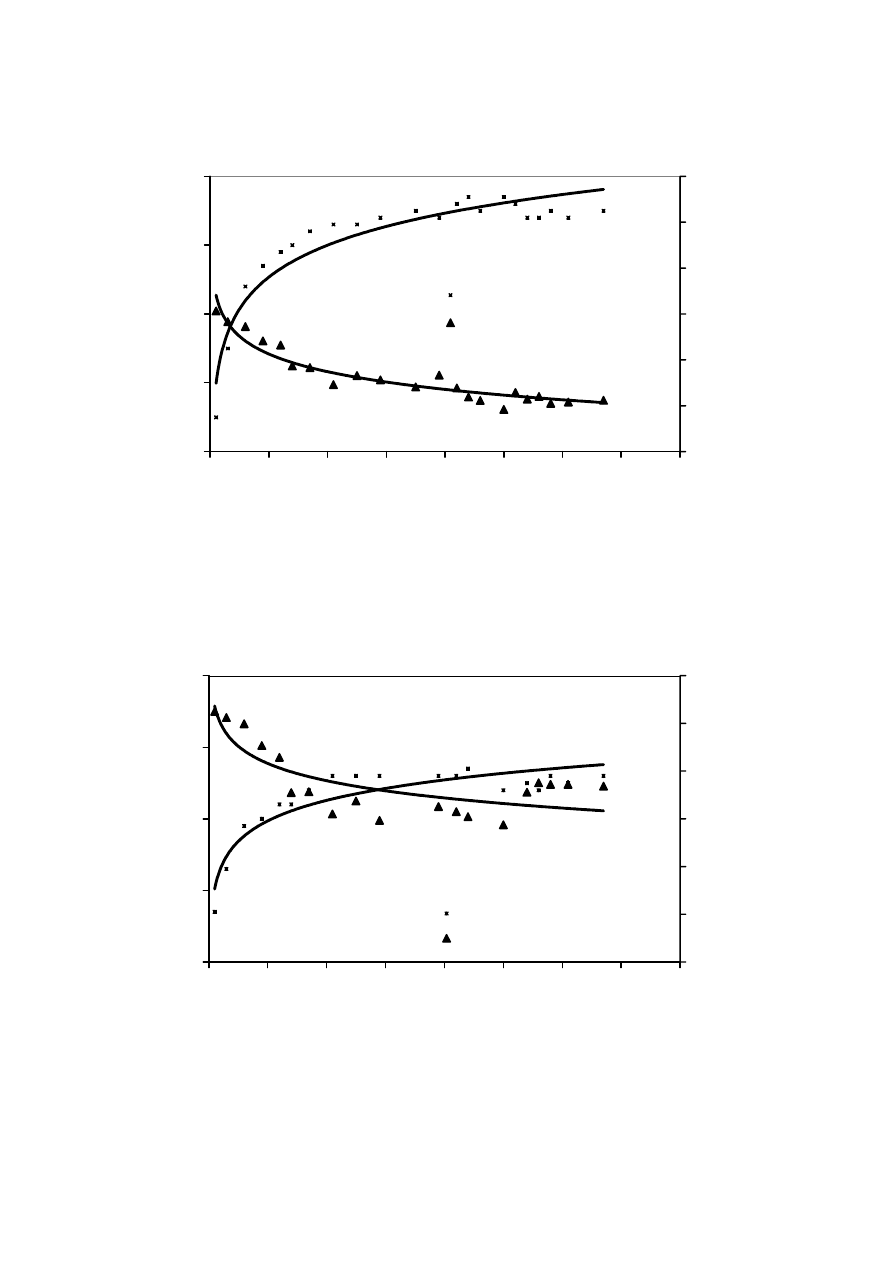

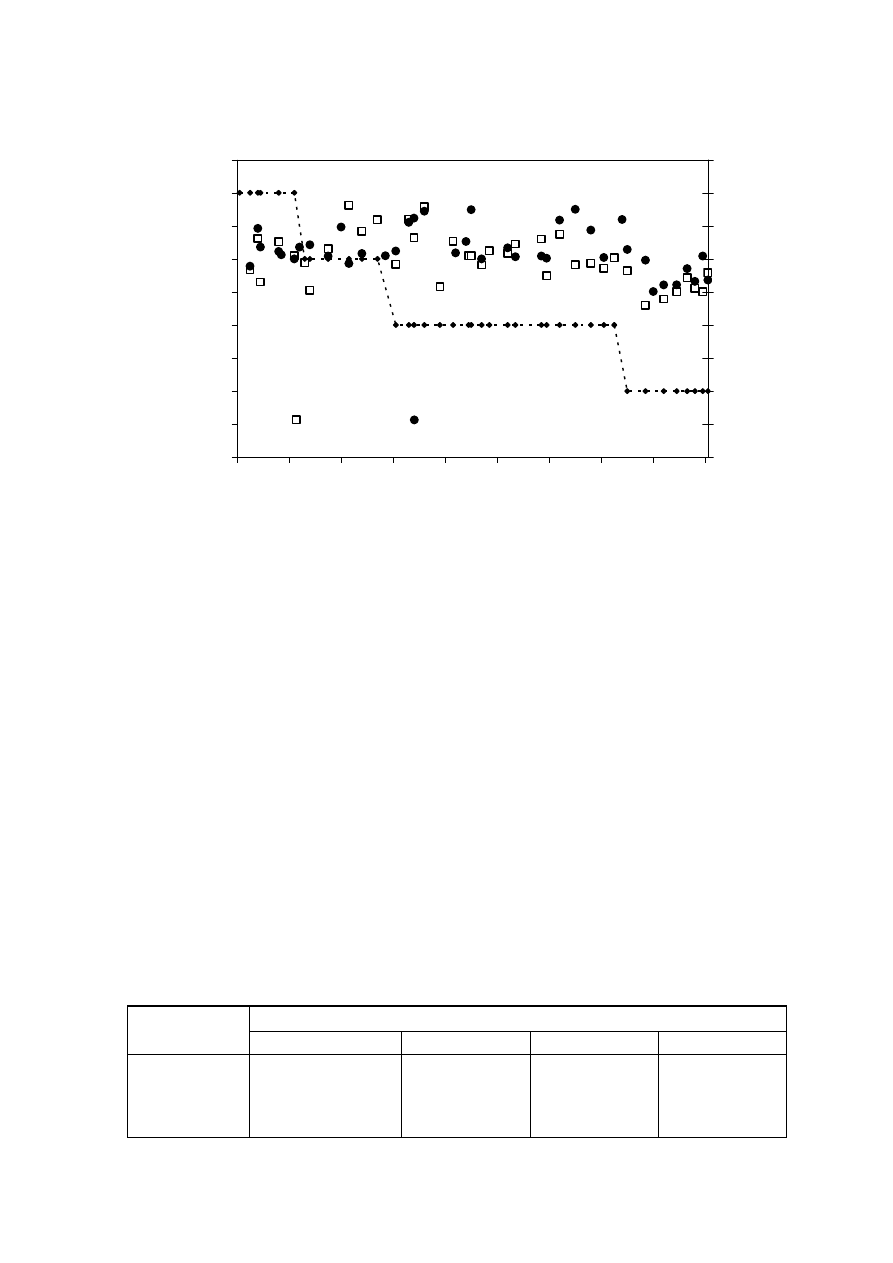

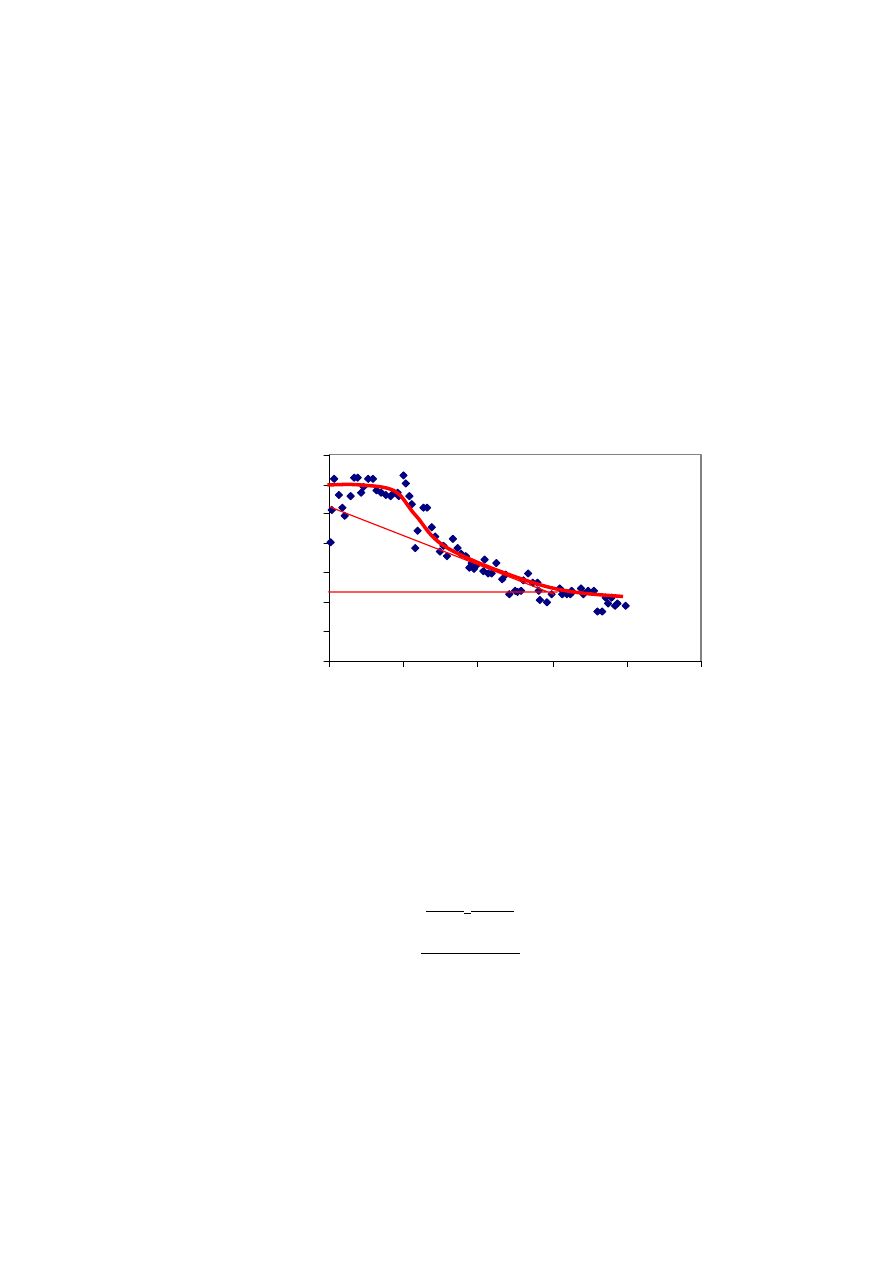

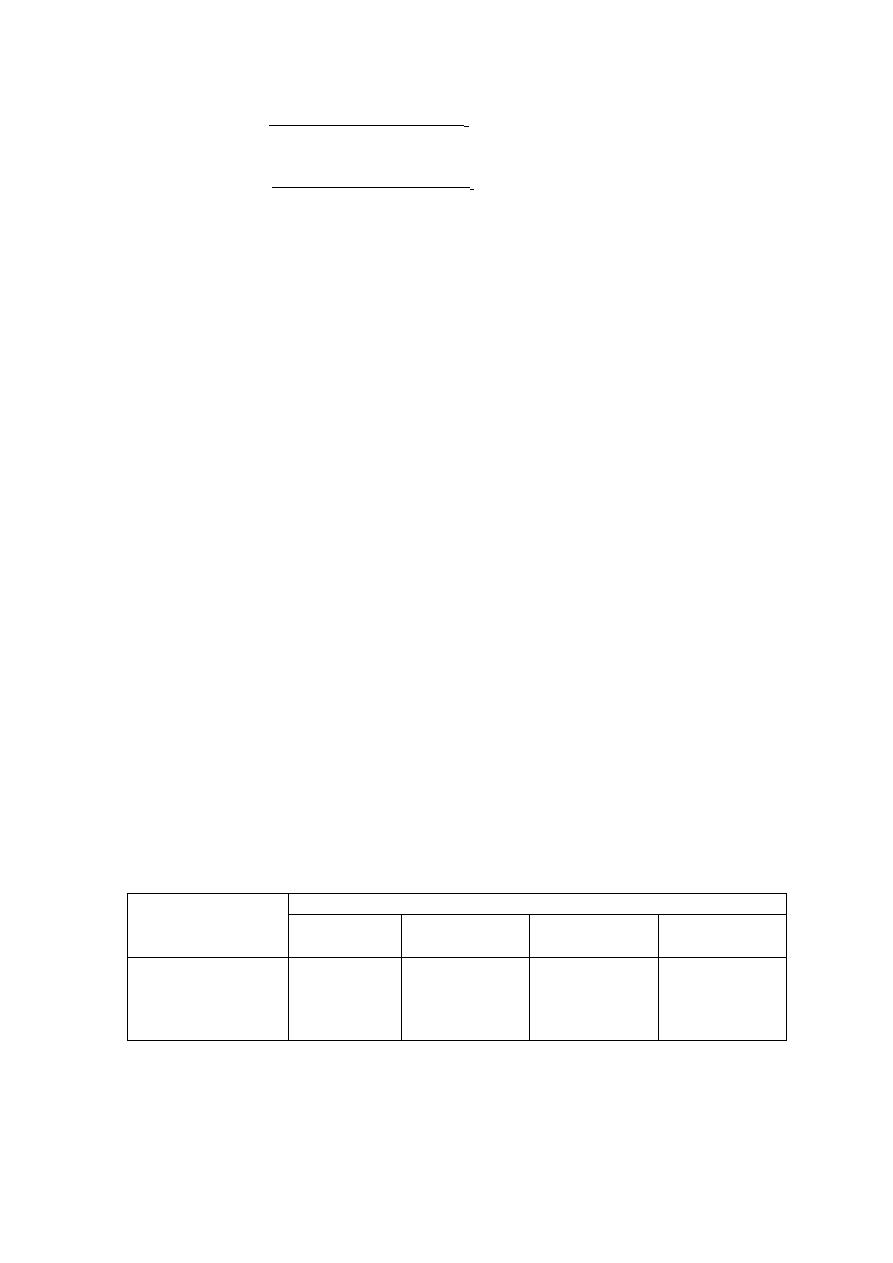

landfill (Chian and DeWalle, 1976; Kylefors, 1997). Figure 2.3 represents the trend of

leachate variation and over the period of time in the landfill. During the initial stages, the

landfill is aerobic rich in biodegradable organic content. As the landfill age increases, the

microorganism present in the landfill tend to degrade these organic compounds into

inorganic components. When anaerobic phase begins, the COD starts increasing causing a

decrease in BOD/COD ratio. This decrease in BOD/COD ratio observed, suggests the

change in biodegradability of the leachate with time. For young landfill, the ratio is around

0.5-0.8 while it reaches almost 0.1 in the old landfill. The reason for low biodegradability

in the old landfill could be due to the presence of humic and fluvic acids.

Figure 2.3 Variation in Significant Pollutant Ratios with Increase in Age of the Landfill

(Chian and DeWalle, 1976)

The ammonium concentration in the leachate also varies with age of the landfill, with

young leachate having a high COD (>5,000 mg/L) and low nitrogen content (< 400 mg

N/L) and old leachate having a high concentrations of ammonia (> 400 mg N/L) and

recalcitrant compounds and a low biodegradable organic fraction (BOD

5

/COD = 0.1).

Municipal solid waste landfill in Asia (except Japan) is characterized by 60 to 90 %

organic waste and 3 to 18 % plastic (Agamuthu, 1999). Leachate characteristics of landfills

surveyed in Asia including Thailand, Europe, and America are presented in Table 2.2. The

characteristic of leachate from different landfill site as reported show a great variation. It is

dependent on the solid waste composition, landfill site location, and local climate. The

BOD and COD concentrations decrease as the landfill age increases.

10

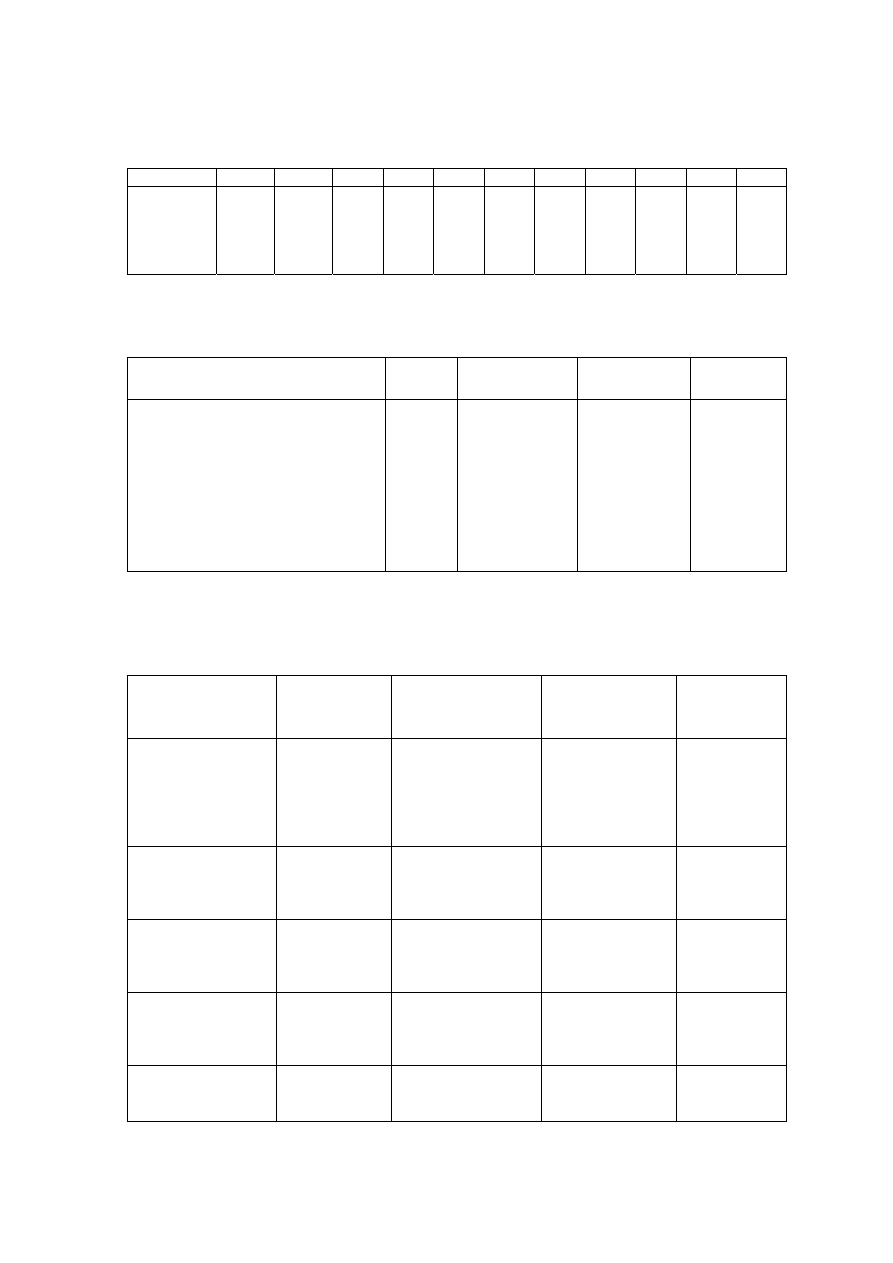

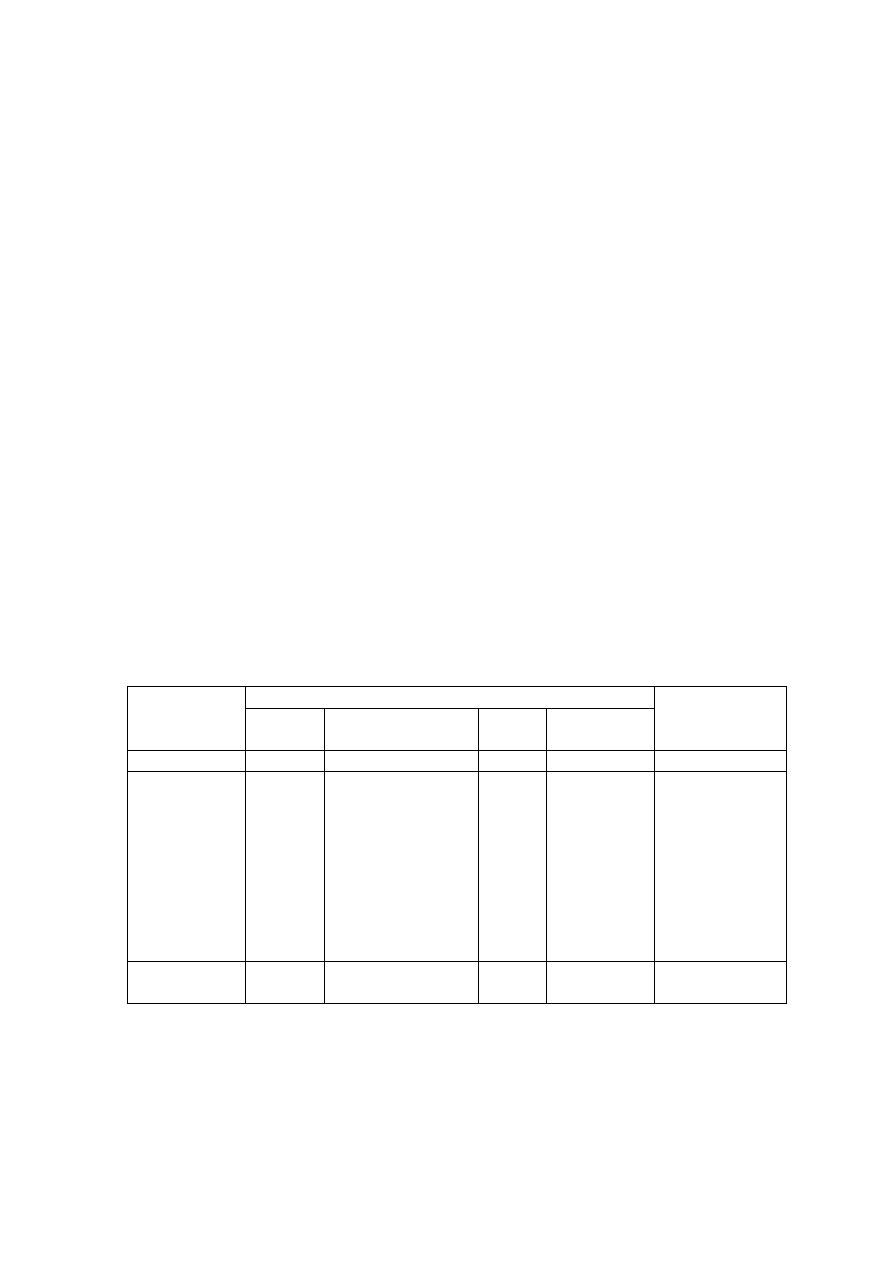

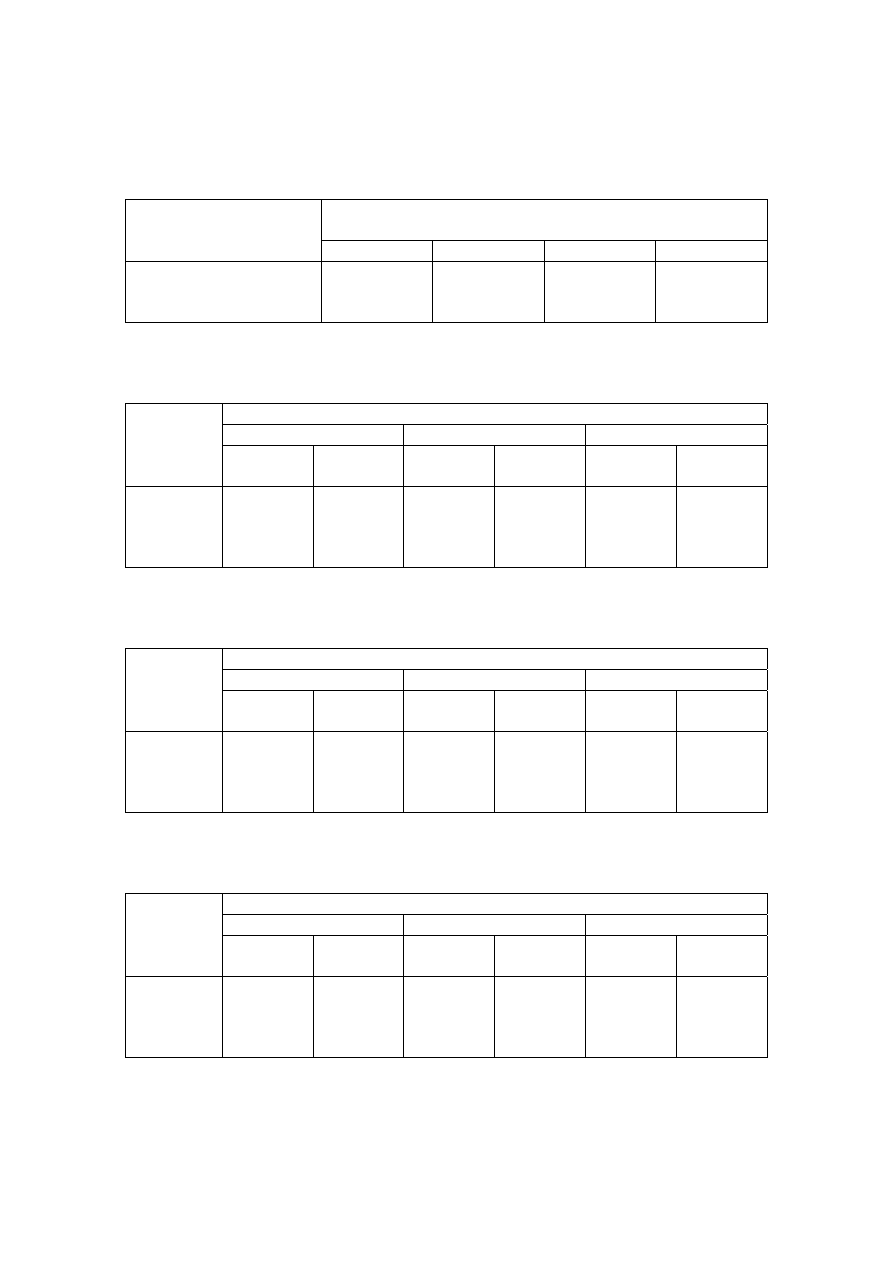

Table 2.2 Comparison of Leachate Characteristics of Landfills Surveyed in Asia, Europe and America

Thailand

1,2

Malaysia

3

Parameter

Phitsanuklok Pathumthani Nakhonpathom Pathumthani On-Nutch

Air

Hitam

Sabak

Bernam

Taman

Beringin

HongKong

4

USA

5

Europe

6

Years in

operation 1

3

4

9 20 5 7 16 6 10 1 5 16

-

Alkalinity 300-4,700 918-4,250 960-2,740

6,620

-

1,540-

9,000

1,200-

1,550

3,750-

9,375

10,700-

11,700

3,230-

4,940

800-

4,000

5,810 2,250

300-

11,500

pH 7.1-8.3

8.2-8.9

8.2-8.5

8.1

7.5

7.6-8.8

8.0-801

7.8-8.7

8.1-8.6

7.6-8.1

5.2-6.4

6.3

-

5.3-8.5

Chloride

-

1,220-5,545

655-2,200

2,530

-

1,625-

3,200

420-

1,820 875-2,875

2,320-

2,740 522-853

600-800 1,330

70

-

SS 1,950

29-110

8.4-15.7

12.5

488

410-

1,250

111-920

420-1,150

40-53

3-124

-

-

-

-

TS 6,700

350-1,598

274-1,200

848

11,320

13,930-

15,380

-

10,300-

13,680

-

-

100-700

-

-

-

COD 4,900-11,000

1,488-3,200

800-3,575 3,200 1,200

1,724-

7,038

1,250-

2,570

1,960-

5,500

2,460-

2,830 641-873

10,000-

40,000 8,000 400

150-

100,000

BOD 3,000-7,150

198-260

100-240 280 130

1,120-

1,800

726-

1,210

562-1,990

-

-

7,500-

28,000

4,000 80

100-

90,000

TKN

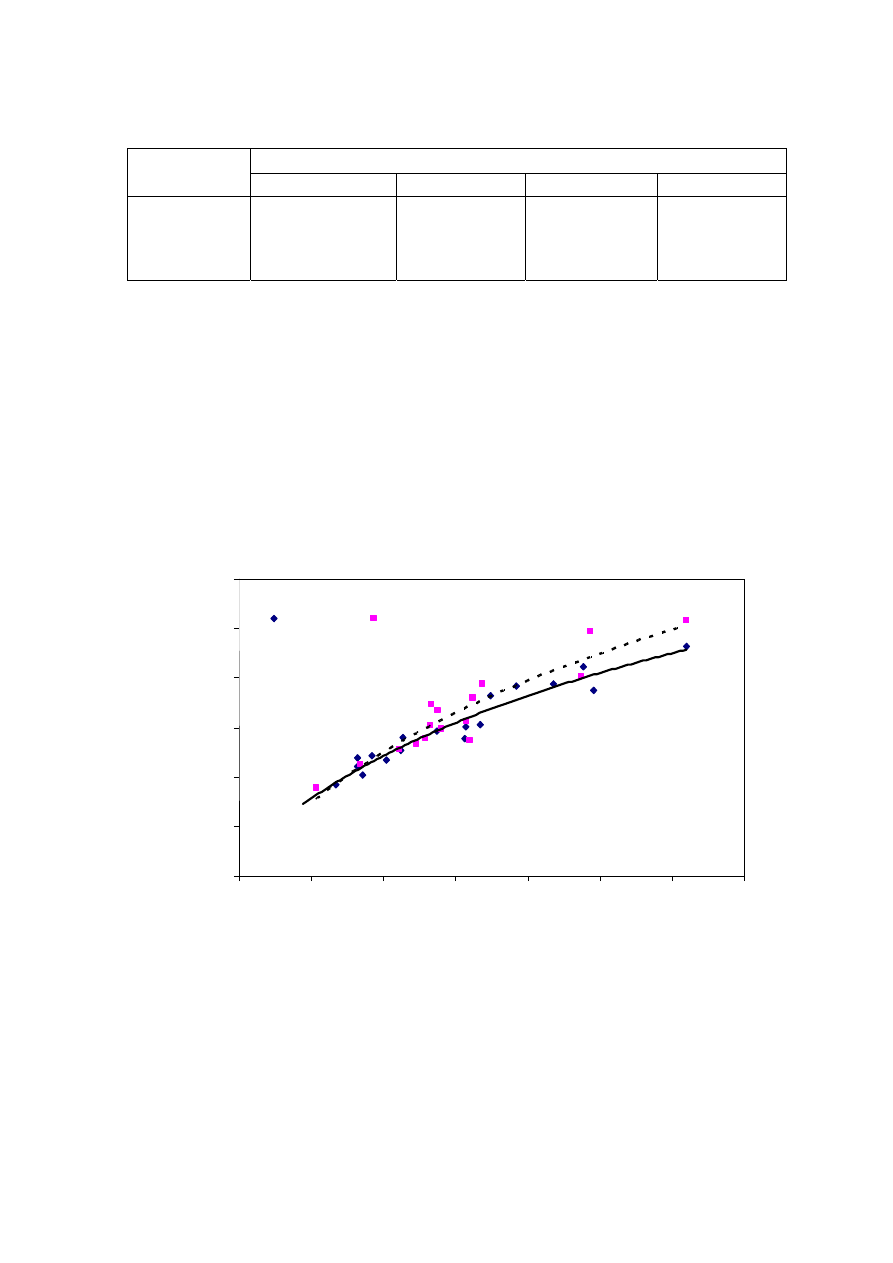

-

240-452

64-1,260

1,256

700

131-930

-

104-1,014

2,219-

2,860

889-

1,180

-

-

-

50-5,000

NH

3

-N

150-1,250

-

-

-

-

2-32

3-8

2-47

1,190-

2,700

784-

1,156

56-482

-

-

1-1500

Ni

0.02-1.56

0.01-0.42

0.1

0.25

0.035

0.13-0.95

-

0-0.6

-

-

-

-

-

0.02-2.05

Cd

0.037

0.02

0.001

0.002

-

0-0.23

0-0.001

0-0.15

-

-

-

<0.05

<0.05

0.14

Pb

0.03-0.45

0.07

0.05

-

0.52

0-5.37

0-0.03

0-3.45

-

-

-

0.5

1.0

1.02

Cr

-

0.01-0.52

0.08-2.9

0.07

-

0.24-0.94

-

0.04-0.70

-

-

-

-

-

0.03-1.60

Hg

0.50-1.70

-

-

-

0.684

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

0.05

Note: All data with the exception of pH values are in mg/L.

1. Pollution Control Department, 2000 3. Agamuthu, 1999 5. Qasim and Chiang, 1994

2. Sivapornpun, 2000 4. Robinson and Luo, 1991 6. Andreottola and Cannas, 1992

11

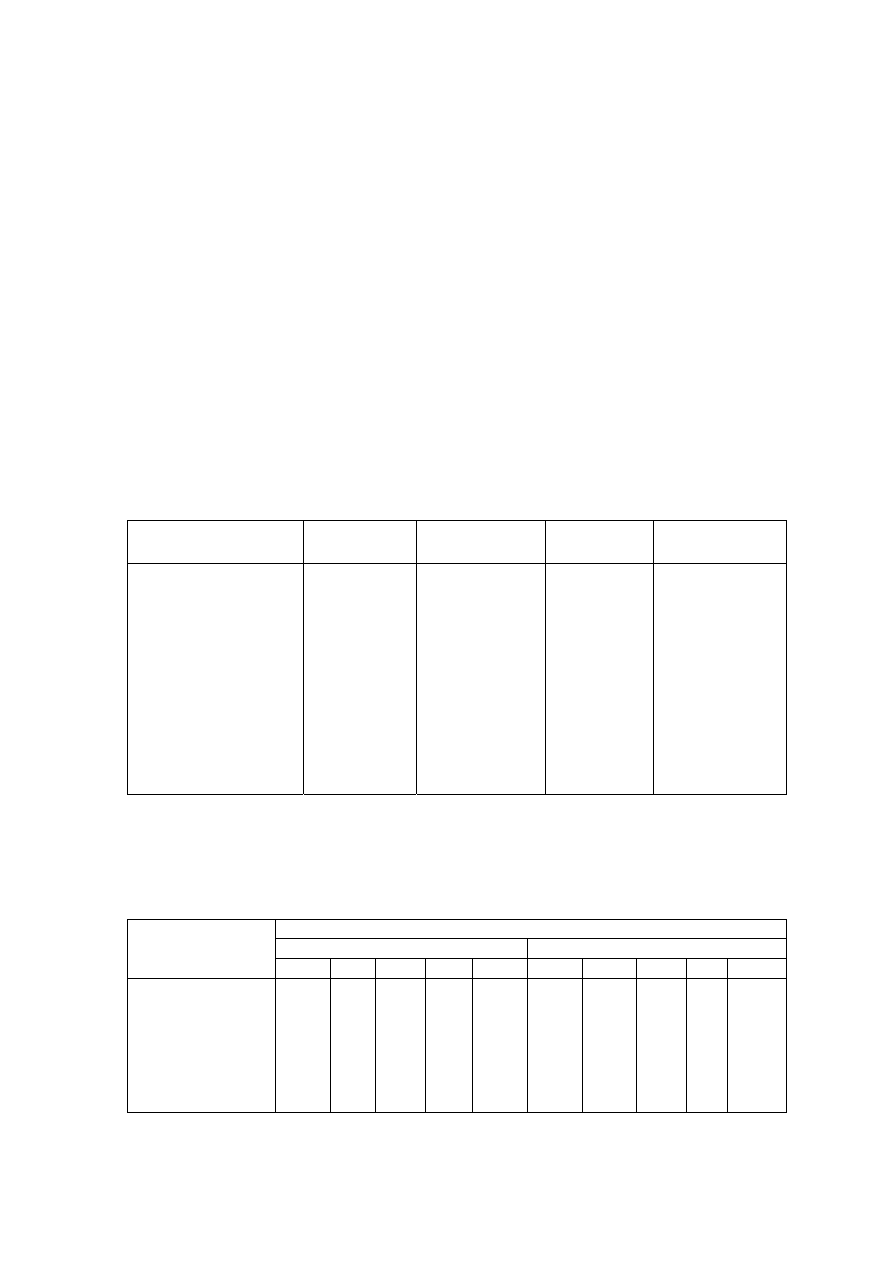

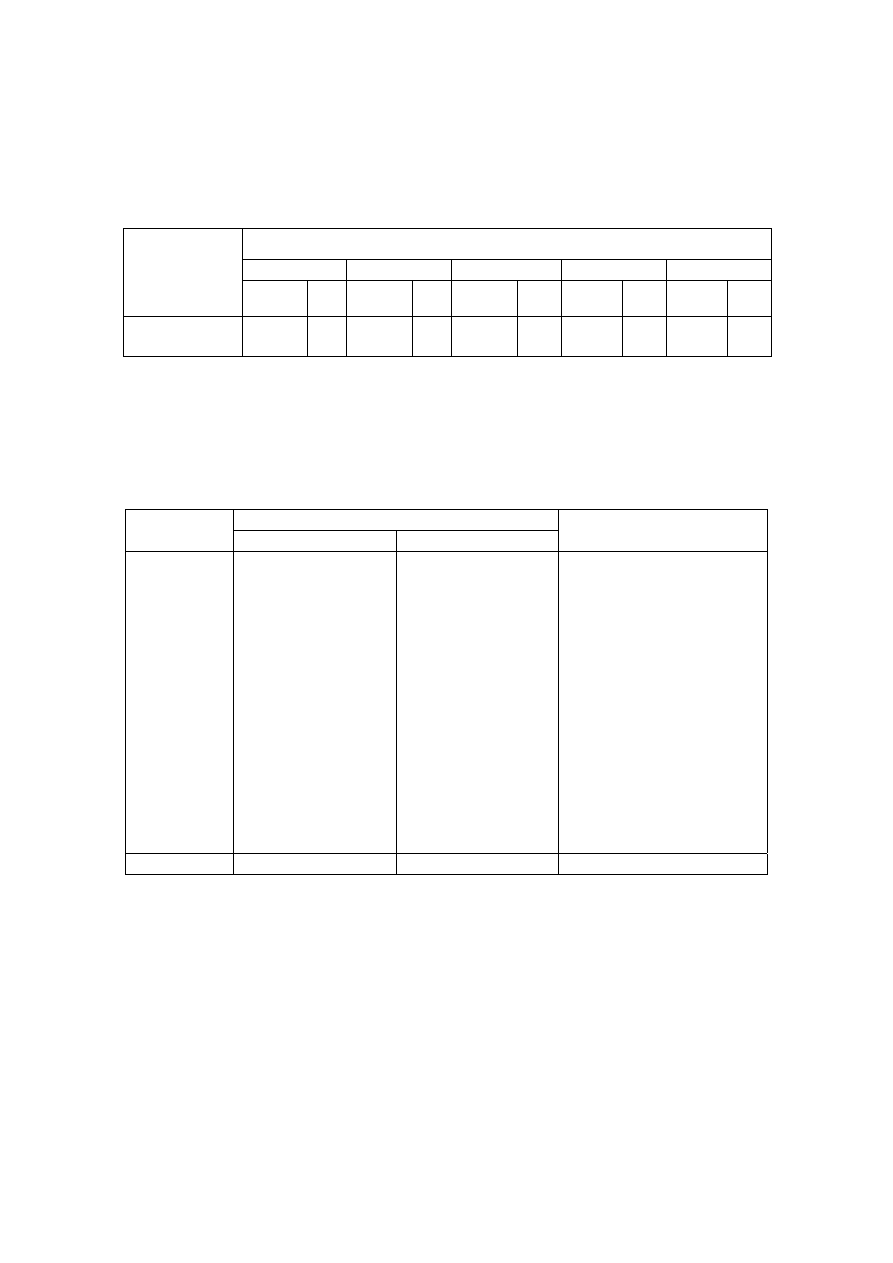

Table 2.3 presents the general leachate characteristics with age and suitability of

treatment options in terms of biodegradable, intermediate and stabilized landfill leachate.

As the young landfill is rich in organic, biological treatment is more appropriate than

physico-chemical which is suitable for the old landfill. However, effectiveness of

combined treatment process for the treatment of a leachate produced at specific landfill age

has not been considered. Individual treatment options cannot be a long-term solution for

leachate treatment as they are not effective in treating leachate generated at different period

of time and do not adapt to changing leachate characteristics.

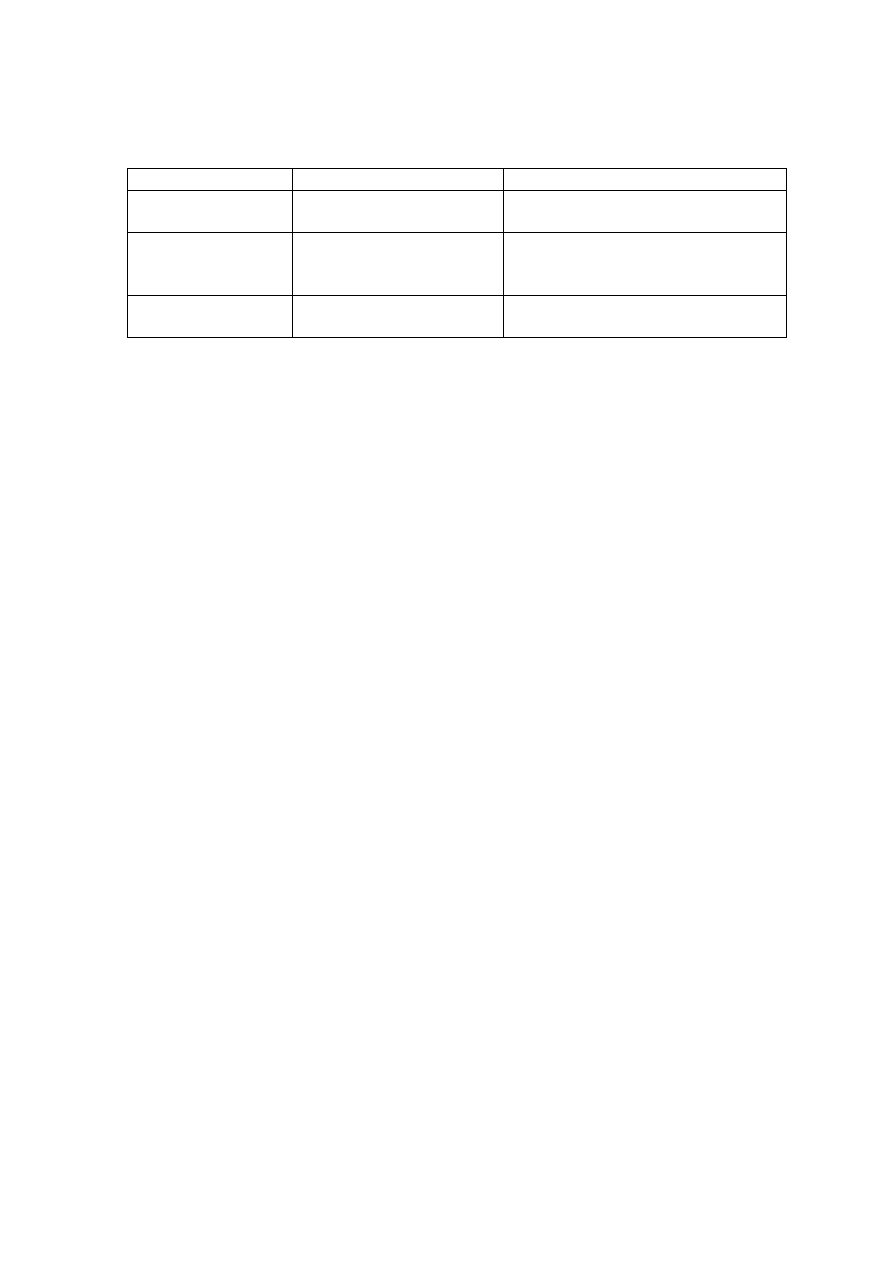

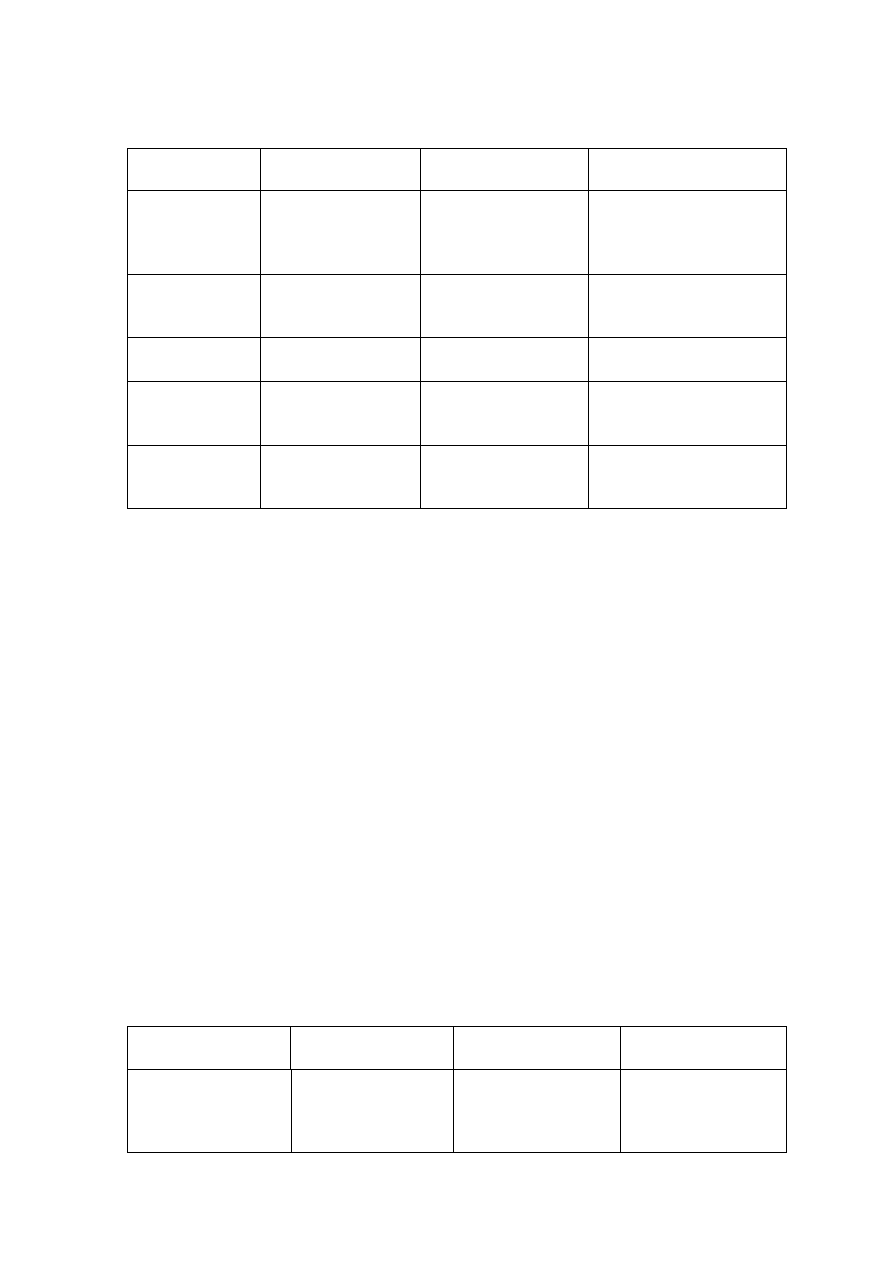

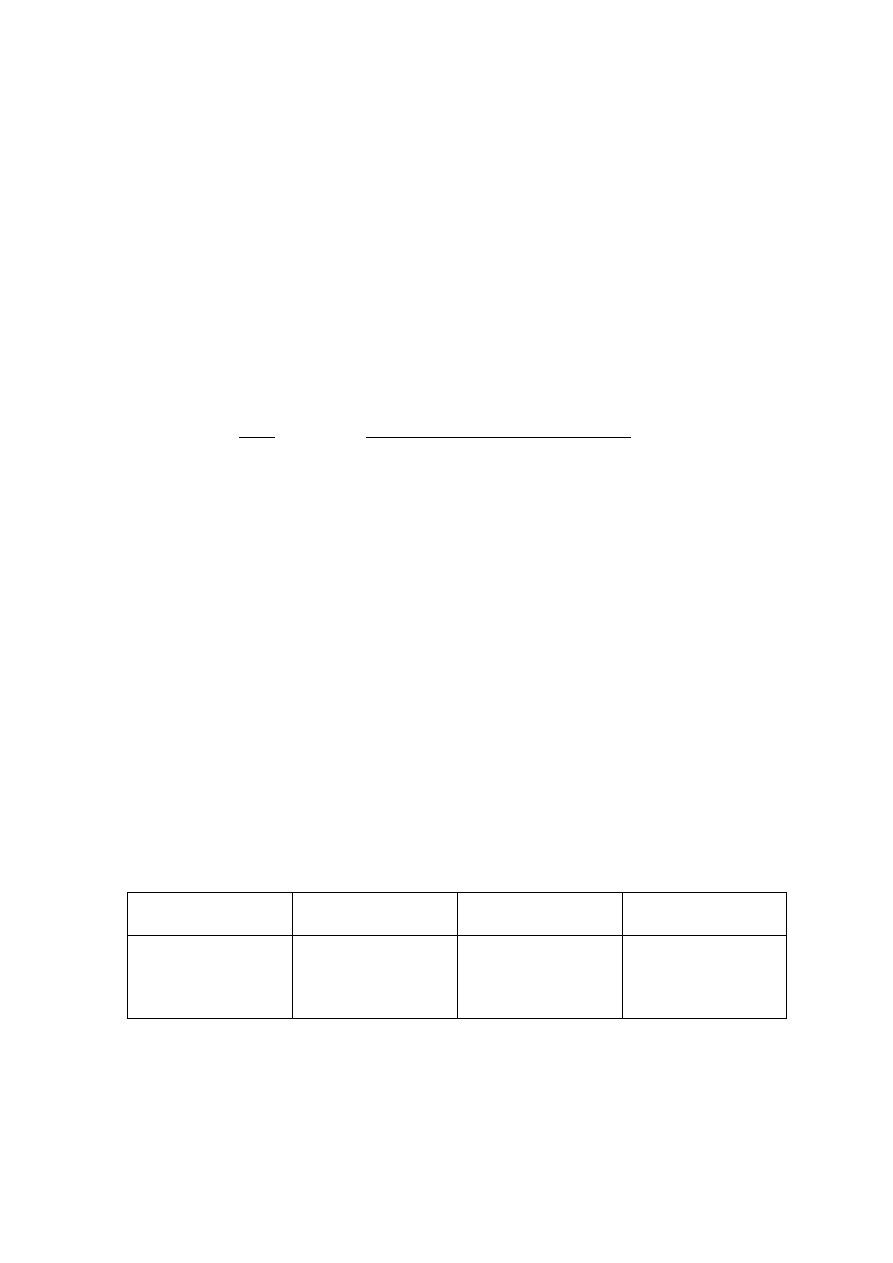

Table 2.3 Relation between Landfill Age, Leachate Characteristics and Treatments

(Amokrane, et al., 1997)

Landfill Age (years)

< 5 (young)

5 to 10 (medium)

> 10 (old)

Leachate Type

I (biodegradable)

II (intermediate)

III (stabilized)

pH

< 6.5

6.5 to 7.5

> 7.5

COD (mg/L)

> 10,000

< 10,000

< 5,000

COD/TOC

< 2.7

2.0 to 2.7

> 2.0

BOD

5

/COD

< 0.5

0.1 to 0.5

< 0.1

VFA (% TOC)

> 70

5 to 30

< 5

Process Treatment

Efficiency

Biological Treatment

Good

Fair

Poor

Chemical Oxidation

Fair-poor

Fair

Fair

Chemical Precipitation

Fair-poor

Fair

Poor

Activated Carbon

Fair-poor

Good-fair

Good

Coagulation-flocculation Fair-poor Good-fair

Good

Reverse Osmosis

Fair

Good

Good

2.6 Molecular Weight Distribution in Landfill Leachate

Ultrafiltration (UF) is demonstrated to be an effective method for characterizing

leachate on the basis of molecular weight (MW) distribution (Gourdon, et al., 1989; Tsai,

et al., 1997; Yoon, et al., 1998; Kang, et al., 2002). The UF cell is operated in a batch

mode with nitrogen gas applied to pressurize the system, producing a driving force for

leachate to permeate through the membranes.

The organic components of leachate are mainly composed of water soluble

substances. The suspended solid content of leachate is generally very low. Organic matter

is dependent on the waste composition and degree of degradation. The predominant

substances in each fraction are given in Table 2.4.

Low molecular weight organics are composed mainly of easily degradable volatile

fatty acids, which contribute to 90 % of this fraction. The most frequently occurring fatty

acids are: acetic, propionic and butanic acids.

Medium molecular weight compounds with molecular weight between 500 and

10,000 Da are characteristic of fulvic acid and humic fraction present in leachate. This

group is dominated by carboxylic and hydroxylic groups and are difficult to degrade, thus

termed refractory compounds. The high molecular weight organic fraction varies from 0.5

% in methanogenic landfill leachate to 5 % in acidogenic landfill leachate. These

compounds are more stable and possibly originate from cellulose or lignin.

12

Table 2.4 Classification of Types of Substances Using Molecular Weight Cutoff (Chian,

1977; Harmsen, 1983)

Division Molecular

Weight

Substances

MW <500 Da

Low Molecular Weight

Volatile fatty acids

Amino acids, Alcohol, Organic acids

MW 500-10,000 Da Medium Molecular

Weight

Carboxyl and aromatic hydroxyl

groups

Fulvic-like substances

MW >10,000 Da

High Molecular Weight

Carbohydrates, Proteins

Humic carbohydrate-like substances

Thurman and Malcolm (1981) reported humic substances (hydrophobic acids)

accounted for about 50 to 90 % of the dissolved organic carbon (DOC) present in leachate,

whereas Imai, et al. (1995) indicated that humic substances contributed to only 30 % of the

DOC. This implies that non-humic substances (hydrophobic neutrals and bases,

hydrophilic acids, neutrals and bases) may be more important than humic substances in

terms of refractory characteristics of leachate.

The effectiveness of a treatment process can be related to the removal of specific

organic fraction in leachate. Both fulvic and humic substances are inert to biological

treatment. The accumulation of high molecular humic carbohydrates were found to affect

bacteria flocculation (Chian and DeWalle, 1976). Therefore, fractionating the organic

based on molecular weight, is an indication of the removal efficiency and degradation

potential of the biological system.

Generally, leachate is highly contaminated with organic concentrations measured as

BOD and COD, with ammonia, halogenated hydrocarbons and heavy metals. The humic

substances constitute an important group of organic matter in leachate (Chain, 1977;

Lecoupannce, 1999). These substances can be compared with humic substances of natural

organic matter (NOM). Humic substances are refractory anionic macromolecules of

medium MW (1,000 Da MW- fluvic acids) to high MW (10,000 Da MW-humic acids).

They contain both aromatic and aliphatic components with primarily carboxylic and

phenolic functional groups. In many case, 500 to 1,000 Da MW fluvic-like fraction

increases with landfill ages and after a biological treatment (Mejbri, et al., 1995).

Therefore, a post treatment step is usually required for complete removal of organics

(Rautenbach and Mellis, 1994).

2.7 Factors Affecting Leachate Composition

In order to arrive at an appropriate treatment process, it is necessary to understand

the leachate characteristic and the factors affecting it. Generally, the quantity of leachate is

a direct function of the amount of external water entering the landfill. Landfill leachate is

composed of the liquid that has entered the landfill from external sources, such as surface

drainage, rainfall, groundwater and the liquid produced from the decomposition of waste.

A generalised pattern of leachate formation is presented in Figure 2.4.

13

Figure 2.4 Water Movements in the Landfill

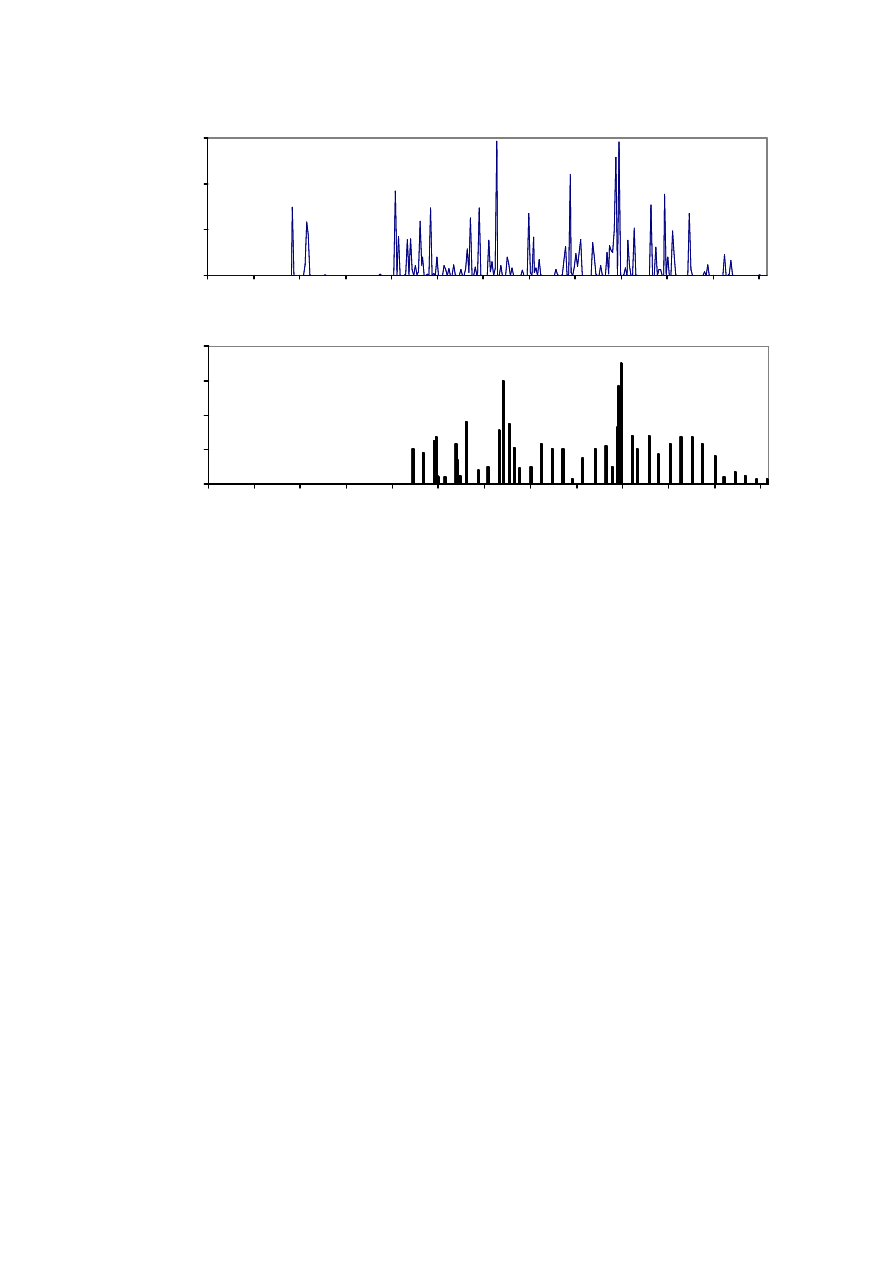

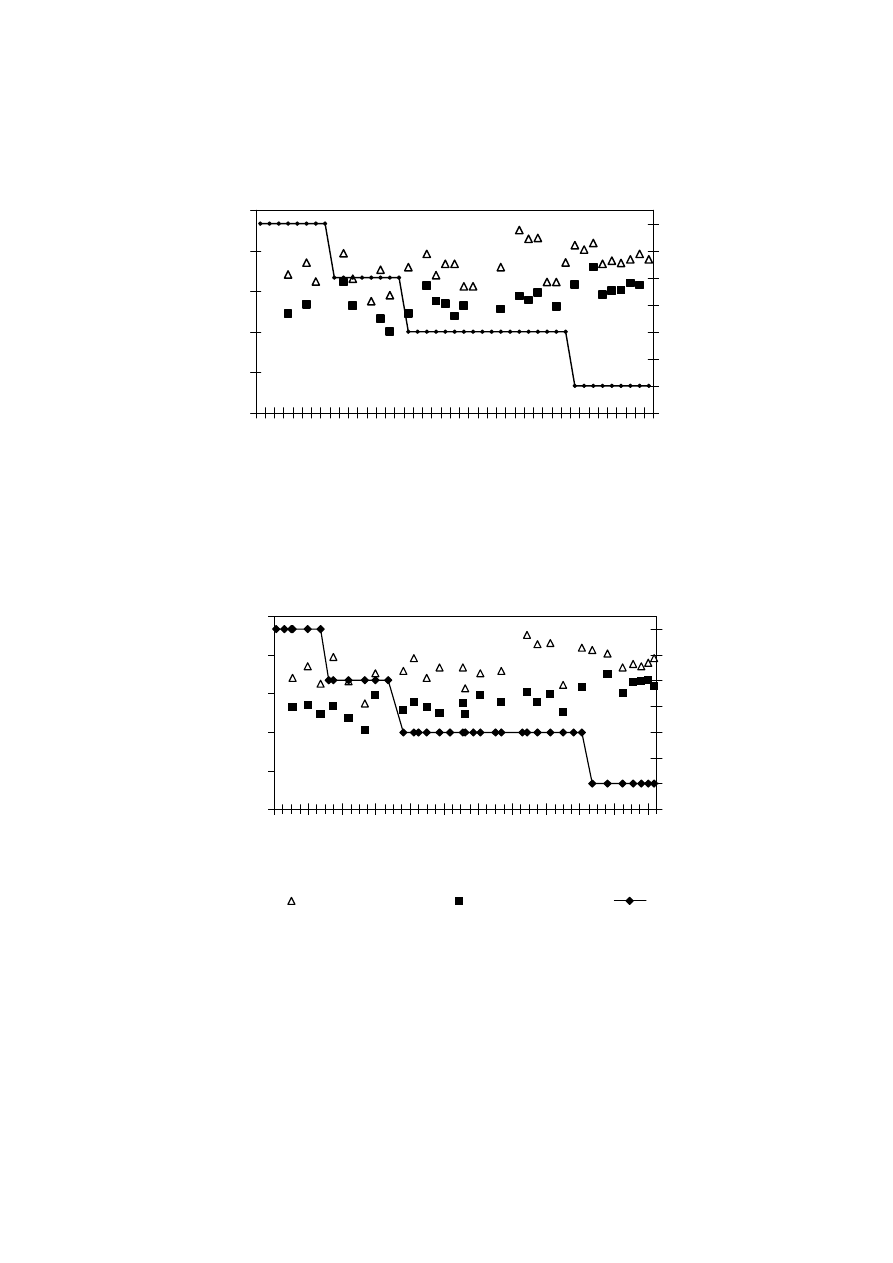

2.7.1 Seasonal Variation

Rainfall acts as a medium of transportation for leaching and migration of

contaminants from a landfill. Rainfall also provides the required moisture content for

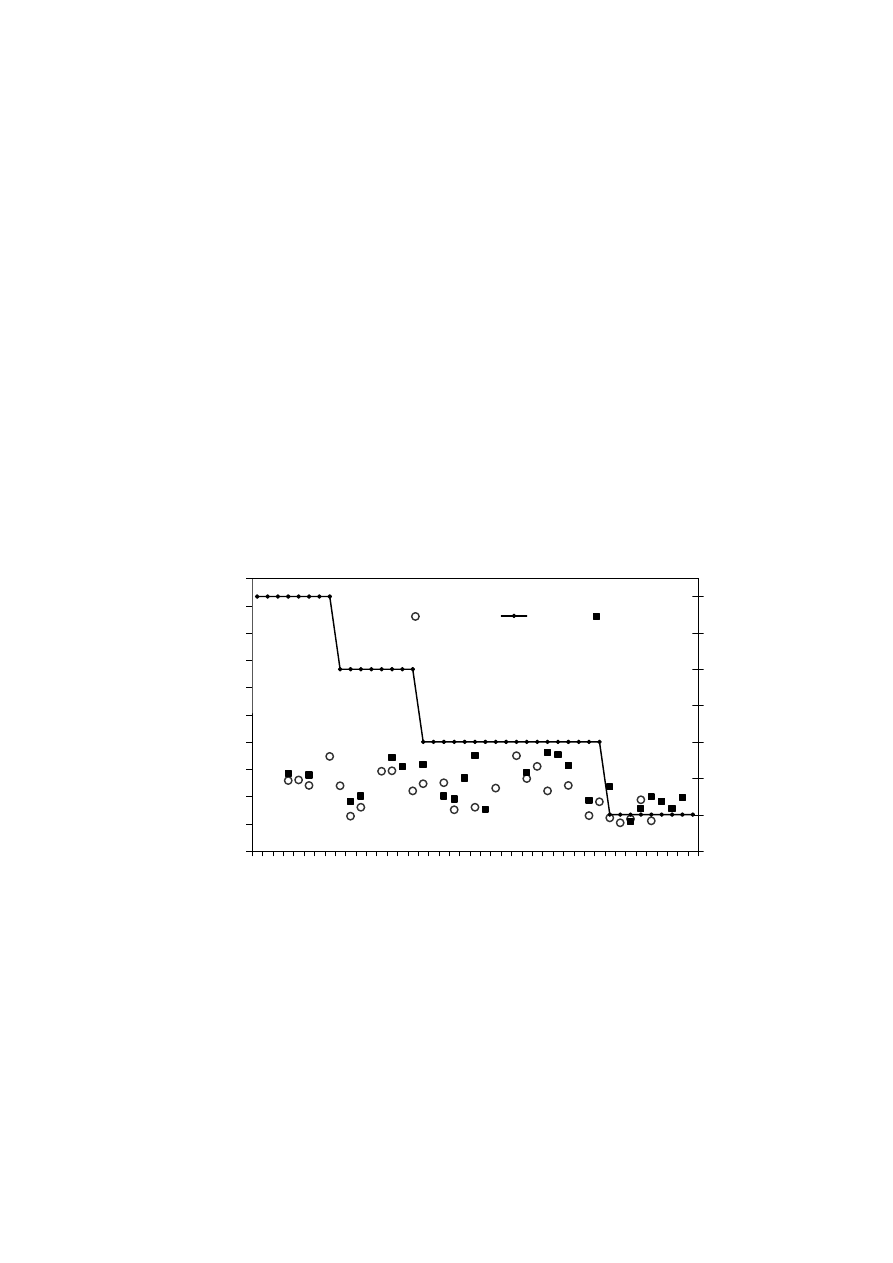

methane production and biological activity. Figure 2.5 shows that the leachate production

varies to a great extent with the amount of rainfall. It has been experienced that in hot and

humid climates, leachate production is much higher and varies more than in hot and arid

regions due to intensive microbial activity

(Trankler, et al., 2001). During dry season, the

leachate production is very low due to the evaporation whereas in raining season, the

leachate production is related to amount of rainfall intensity. Therefore, when designing a

landfill for disposal of municipal waste, and developing a treatment scheme for leachate

treatment, the quality and quantity of leachate may be influenced by climate and microbial

activity

.

On the other side, though high rainfall leads to increased leachate production, it

reduces leachate strength due to the dilution. The quality of leachate produced may be

regarded as proportional to the volume of water percolating through the landfill waste.

Reduction of the quantity of water entering the tip is therefore of great importance in

reducing the rate of leachate generation (Tatsi and Zouboulis, 2002). Few researchers have

measured the temporal variation in leachate production as 2-45 L/s, depending largely on

the precipitation over the landfill (Martin, et al., 1995). The influence of seasonal variation

in the landfill leachate quality and quantity varies from place to place which is also

influenced by other factors. It is necessary to consider the hydrological and leachate quality

data while suggesting a treatment for leachate to avoid environmental deterioration

problems caused by direct disposal.

Precipitation

Ground

Ground

Leachate

Surface runoff

Surface

runoff

Evaporation

Evaporation

Storage

Gas

Gas

Ground water

Ground water

Leachate

14

Figure 2.5 Leachate Productions and Rainfall Variation with Time

(Visvanathan, et al., 2003)

2.7.2 Landfill Age

Leachate sampling and analysis are of importance in assessing the changes in

leachate quality over a period of time. A distinction of the age of a landfill can be made on

the basis of the dominating degradation phase within the fill and the composition of the

leachate generated. The response of landfill leachate quality and quantity to the climatic

variation depends on the age of the landfill. Few significant variations such as a decreasing

trend of BOD/COD are evident as the landfill age increases. The BOD/COD ratio depicts

the biodegradability of the leachate, with a ratio of 0.5 indicating a readily degradable

organic material while a value of 0.1 or below represents a high fraction of poorly

degradable organic material in the leachate (Table 2.3). The variation in the quality of

leachate from a landfill in Taiwan composed of ten different units closed each year is

expressed in Table 2.5. From the given table, it could be observed that as the landfill gets

stabilized, BOD and COD concentrations reduce along with decrease in biodegradability.

Nitrogen concentration is another indicator which signifies the age of the landfill leachate

as presented in Table 2.6 and 2.7. The ammonia concentration in leachate is high due to

hydrolysis, decomposition, and fermentation of biodegradable substrate. Owing to the

anaerobic conditions within landfill, nitrite and nitrate concentrations are low. In the first

few years, the ammonia concentration tends to increase slightly over time and then

decreases as the landfill age increases. Thus, it could be appropriate to say that looking at

the leachate characteristic, the age of the landfill can be predicted to a great extent.

0

20

40

60

80

1/

1/

02

31

/1

/0

2

2/

3/

02

1/

4/

02

1/

5/

02

31

/5

/0

2

30

/6

/0

2

30

/7

/0

2

29

/8

/0

2

28

/9

/0

2

28

/1

0/

02

27

/1

1/

02

27

/1

2/

02

Date/Month/Year

0

20

40

60

1/

1/

02

31

/1

/0

2

2/

3/

02

1/

4/

02

1/

5/

02

31

/5

/0

2

30

/6

/0

2

30

/7

/0

2

29

/8

/0

2

28

/9

/0

2

28

/1

0/

02

27

/1

1/

02

27

/1

2/

02

L

e

ac

h

ate

P

ro

d

u

cti

o

n

(

L

/d

)

Ra

in

fa

ll

(

m

m

)

0

20

40

60

80

1/

1/

02

31

/1

/0

2

2/

3/

02

1/

4/

02

1/

5/

02

31

/5

/0

2

30

/6

/0

2

30

/7

/0

2

29

/8

/0

2

28

/9

/0

2

28

/1

0/

02

27

/1

1/

02

27

/1

2/

02

Date/Month/Year

0

20

40

60

1/

1/

02

31

/1

/0

2

2/

3/

02

1/

4/

02

1/

5/

02

31

/5

/0

2

30

/6

/0

2

30

/7

/0

2

29

/8

/0

2

28

/9

/0

2

28

/1

0/

02

27

/1

1/

02

27

/1

2/

02

L

e

ac

h

ate

P

ro

d

u

cti

o

n

(

L

/d

)

Ra

in

fa

ll

(

m

m

)

15

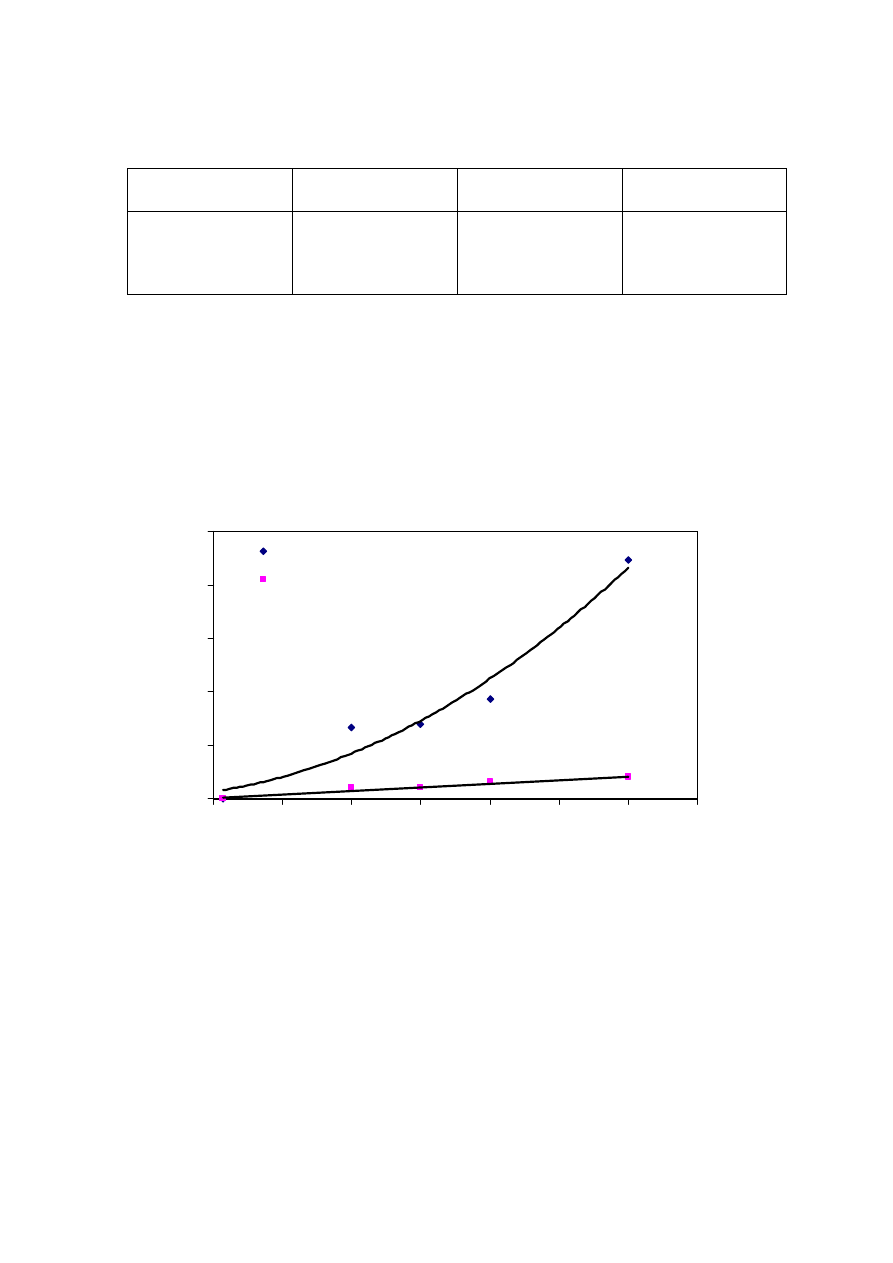

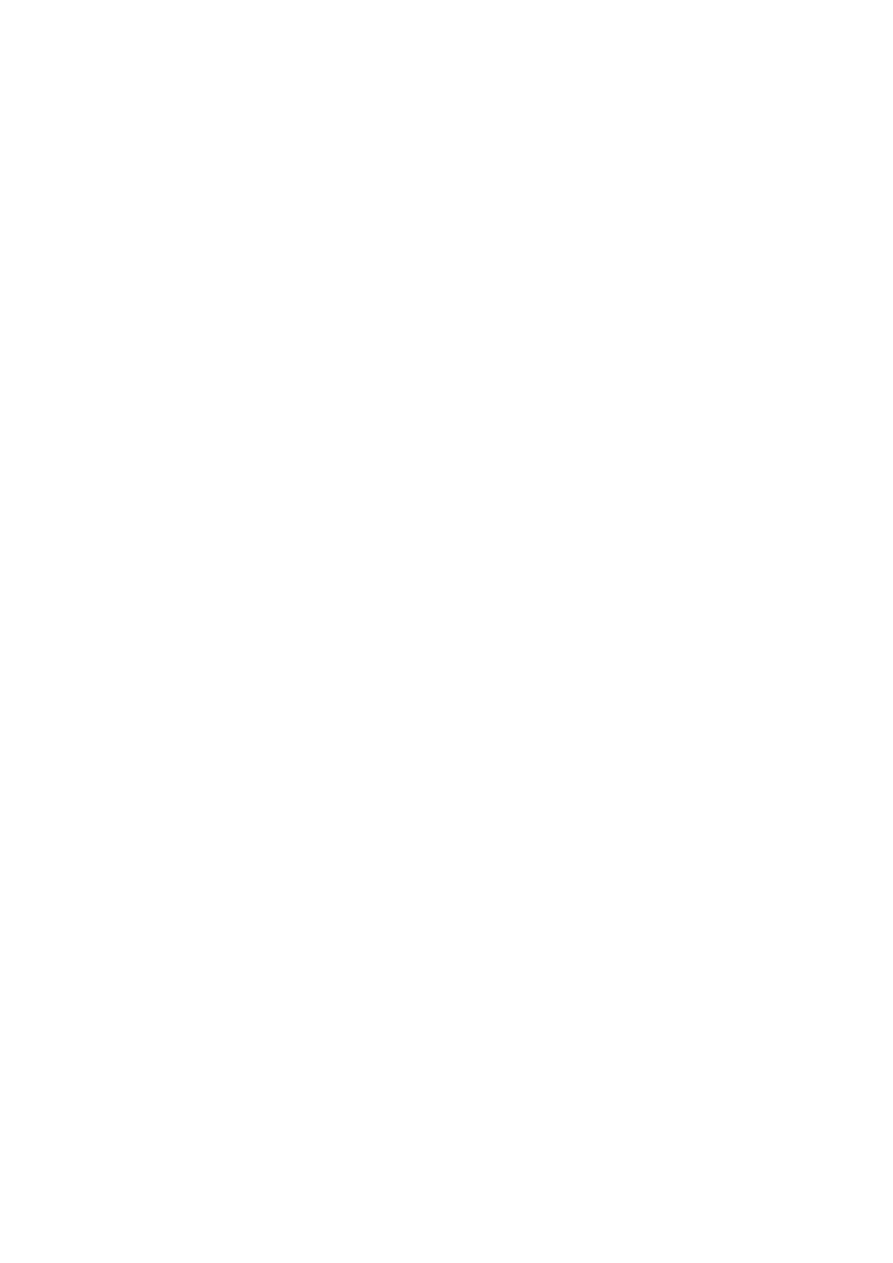

Table 2.5 Variation of COD, BOD & BOD/COD with Increasing Landfill Ages

(Ragle, 1995)

Age (year)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

11

BOD

(mg/L)

25,000

10,000 290 260 240 210 190 160 130 100 80

COD

(mg/L)

35,000 16,000 1,850 1,500 1,400 1,200 1,200 1,150 1,100 1,050 1,000

BOD/COD 0.71 0.60 0.17 0.17 0.16 0.16 0.14 0.13 0.10 0.08 0.08

Table 2.6 Nitrogen Concentrations from Various Sources

Sample

Age

(Year)

NH

3

-N

(mg/L)

Organic-N

(mg/L)

NO

3

-N

(mg/L)

Sewage

1

-

15

10

0

Young leachate

1

1

1,000-2,000

500-1,000

0

Pillar Point (Hong Kong)

6

2,563

197

2.5

Ma Yau Tong (Hong Kong)

2

10 1,156

24 1.1

Several sites (Germany)

1

12

1,100 - -

Du Page Co. (Illinois)

1

15

860

-

-

Rainham (UK.)

1

24

17

-

-

Waterloo (Canada)

1

35

12

-

-

Sources: 1 McBean, et al., 1995. 2 Robinson and Luo, 1991

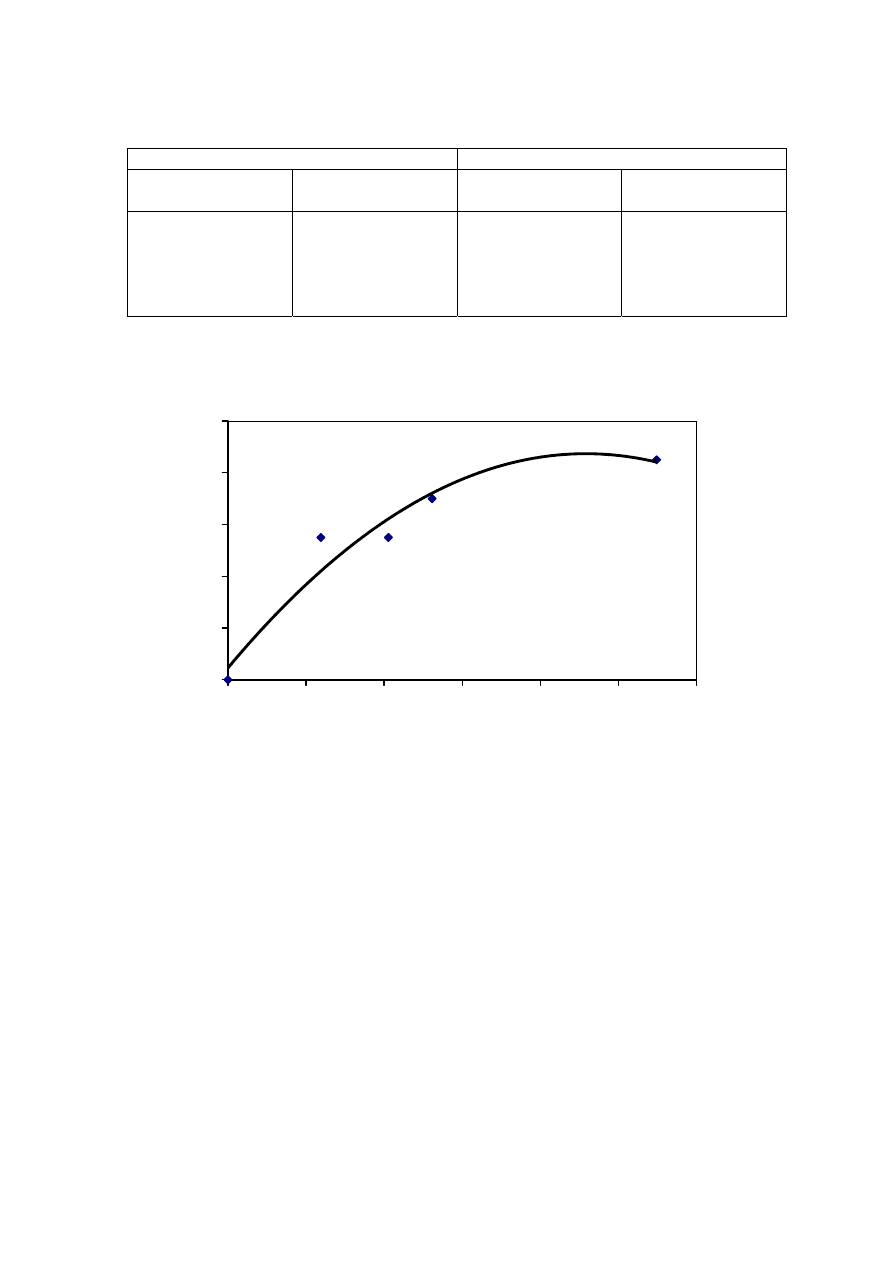

Table 2.7 Nitrogen Concentration Ranges in the Leachate for Landfill Stabilization

Leachate/Gas

Constituent

Transition

Phase

Acid Formation

Phase

Methane

Fermentation

Phase

Final

Maturation

Phase

TKN (mg/L)

180-860

14-1,970

May be low due to

microbial assimilation

of nitrogeneous

compounds

25-82

Low due to

microbial

assimilation of

nitrogeneous

compounds

7-490

NO

3

-N (mg/L)

0.1-5.1

Increasing due

to oxidation of

ammonia

0.05-19

Decreasing due to

reduction to NH

3

or

N

2

gas

Absent

Complete

conversion to NH

3

or N

2

gas

0.5-0.6

NH

3

-N (mg/L)

120.125

2-1,030

Increasing due to NO

3

reduction and protein

breakdown

6-430

Decreasing due to

biological

assimilation

6-430

NH

3

/TKN Ratio

0.1-0.9

0-0.98

Protein breakdown;

biological

assimilation

0.1-0.84

0.5-0.97

Nitrogen Gas (%)

70-80

Influence of

trapped air

60-80

Decreasing due to

dilution with CO

2

< 20

Artefact of trapped

air; denitrification

> 20

Aerobic

metabolism

16

2.7.3 Composition of the Waste Dumped

The leachate quality is greatly affected by refuse composition. Organic material

present in the waste mainly comprises of kitchen waste while the inorganic constituents

consists of the plastic, glass, metal, etc. The leachate composition depends upon the ratio

of organic and inorganic components present in the waste disposed in the landfill. It is

estimated that approximately one half of the municipal solid waste is typically composed

of cellulose and hemicellulose (Fairweather and Barlaz, 1988; Barlaz, et al., 1989), which

are considered readily degradable in the environment. The organic content leached into the

leachate is as a result of hydrolysis and degradation of higher molecular weight organic

compounds by the microorganisms present in the waste. However, it has been shown that

readily degradable refuse components can sometimes persist for surprisingly long periods

of time in landfills owing to several environmental factors that limit the microbial growth

(Suflita, et al., 1992; Gurijala and Suflita, 1993). The other factors which influence the

leachate are the moisture content, nutrients and organic loading in the solid waste disposed.

2.7.4 Geological Characteristic

As the leachate percolates through the underlying strata, many of the chemical and

biological constituents originally contained in it will be removed by filtering and

adsorptive capacity of the material composing the strata. In general, the extent of this

action depends on the characteristics of the soil and especially the clay content. With this

potential, it can allow the leachate to percolate into the landfill for elimination or

contamination, thereby playing a role in affecting the leachate quantity. The influence of

soil particle size, the type of soil in the underlying ground and cover material are factors

that further influence leachate production and strength.

2.7.5 Filling Technique

Various factors during the filling of the municipal solid waste in the landfill

influence the leachate quality and quantity to a great extent.

Filling Height: The surface to volume ratio of the waste in landfill has an impact

over the infiltration, heat transfer and gas exchange occurring within the landfill. It is

expected that an increase in landfill height may limit the affect of seasonal variation in the

leachate composition and can preserve the heat from the microbial action to enhance

further degradation. However, aerobic conditions can be hindered due to limitations in gas

transfer, thereby converting it into anaerobic conditions, thus affecting the leachate quality.

Density: Waste with low density results in a larger volume of air infiltrating through

the landfill and thus promoting aerobic degradation process. This enhances the degradation

of easily degradable waste fractions and complex organic and also elevates temperature

within the landfill which can in turn improve conversion into inorganic constituents. A

prolonged aerobic phase can lead to a drought condition within the fill and reduce

degradation rates.

Enhanced Stabilization: In order to reduce the time required for leachate treatment,

it is necessary to enhance leachate stabilization. Stabilization can be accomplished by two

ways namely, pre-treatment by size reduction, mixing and pre-composting or by using flow

systems to influence the environmental conditions within the landfill. Continuous flow

17

entails the re-circulation of leachate or abstraction of gas within the fill. Kylefors (1997)

reported that leachate re-circulation affects landfill stabilization by removing the waste

products after degradation from the liquid phase, allowing the addition and distribution of

microorganisms and nutrients with the landfill and maintaining homogeneous conditions

within the fill.

Separation of Leachate: Different waste categories at municipal solid landfills will

generate leachate with varying characteristics. Since, this contributes to the complexity in

leachate treatment, it may be beneficial to sort waste in terms of the leachate characteristics

in order to improve the efficiency of the treatment (Kylefors, 1997). This can be achieved

by separation of leachate based on waste characteristics and by separation of leachate

based on degradation phases. Further, the composition of the waste landfilled can also be

altered by the addition of nutrients, seed and buffers to improve the microbial processes

within the fill. Generally, a combination of digested sewage sludge and alkaline ash is

added to enhance methanogenesis.

Bottom Liners and Top Covers: The bottom liners are selected to prevent seepage

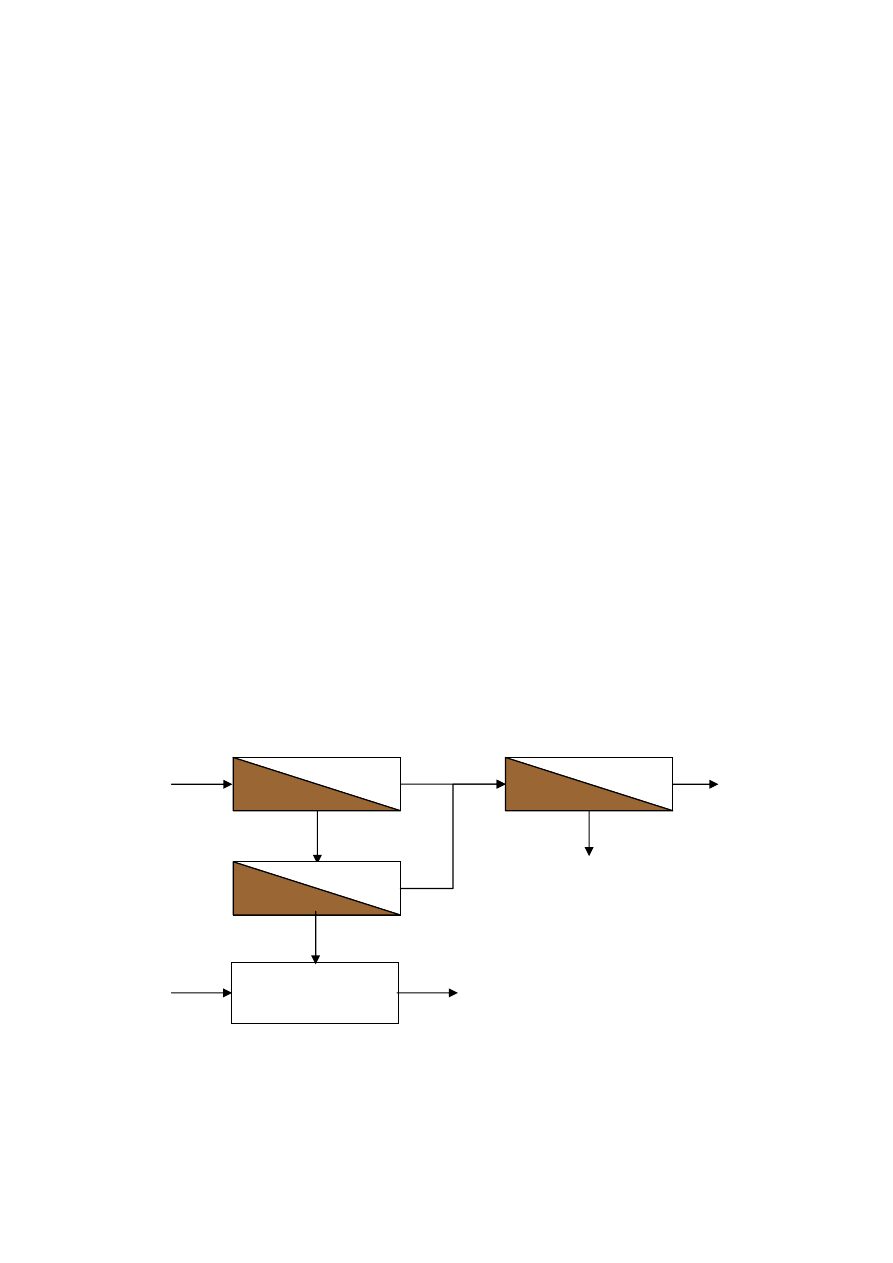

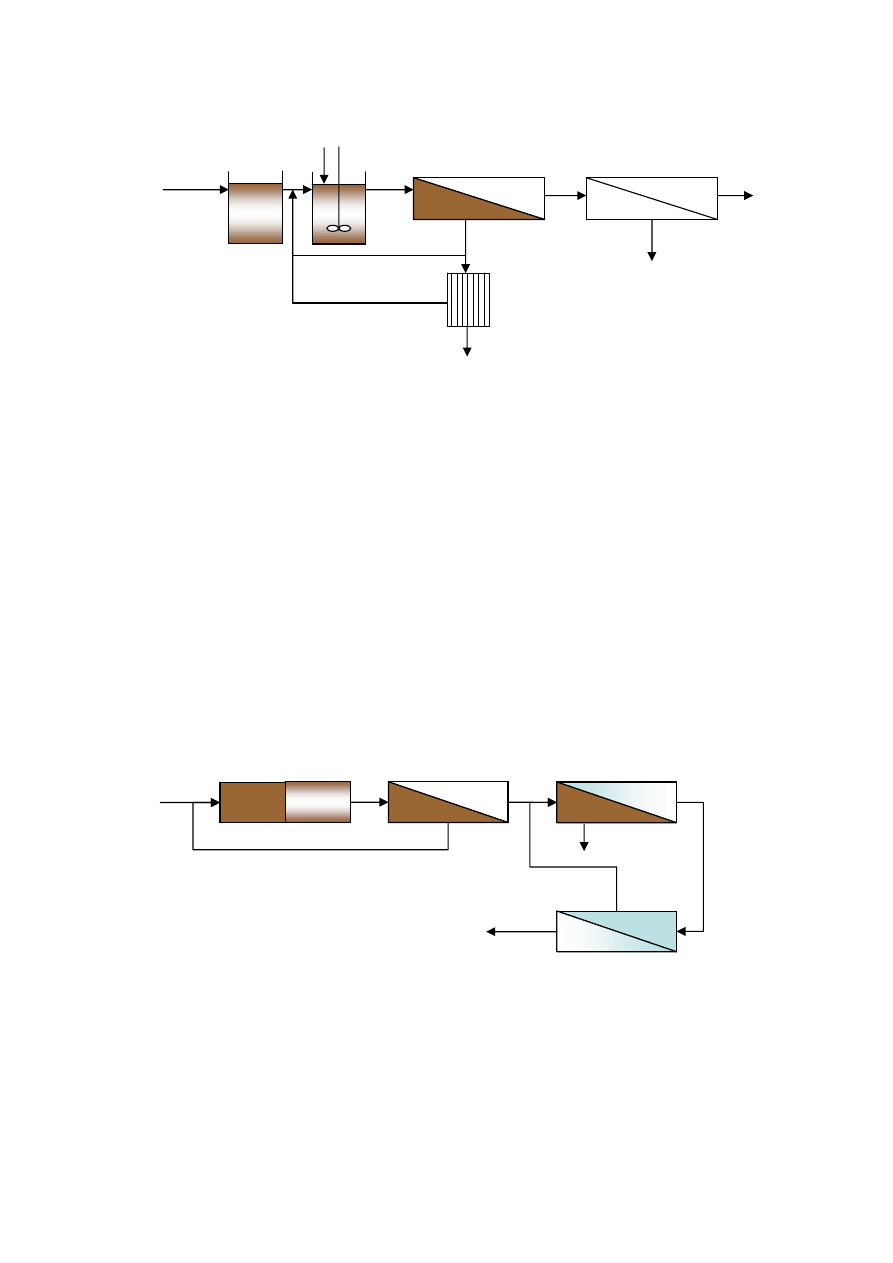

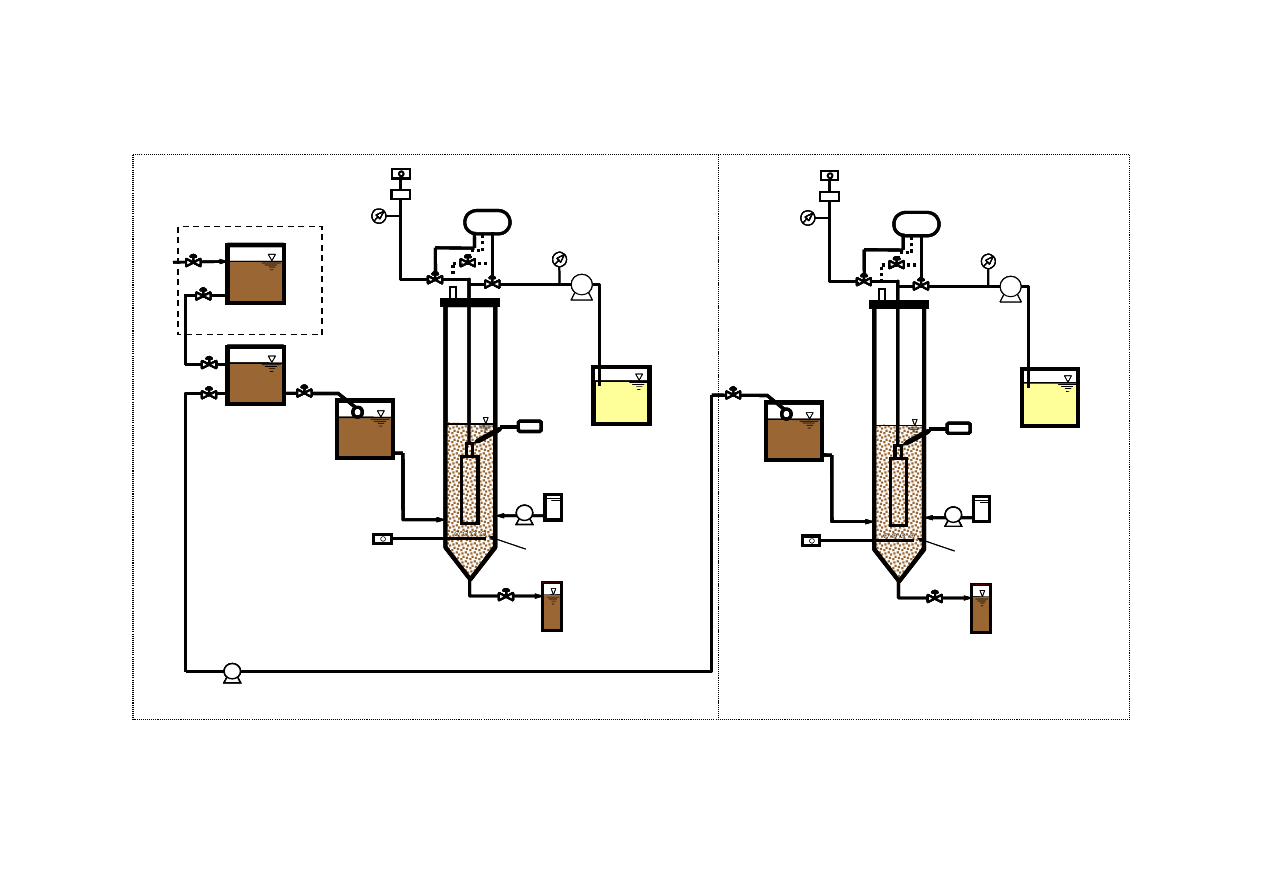

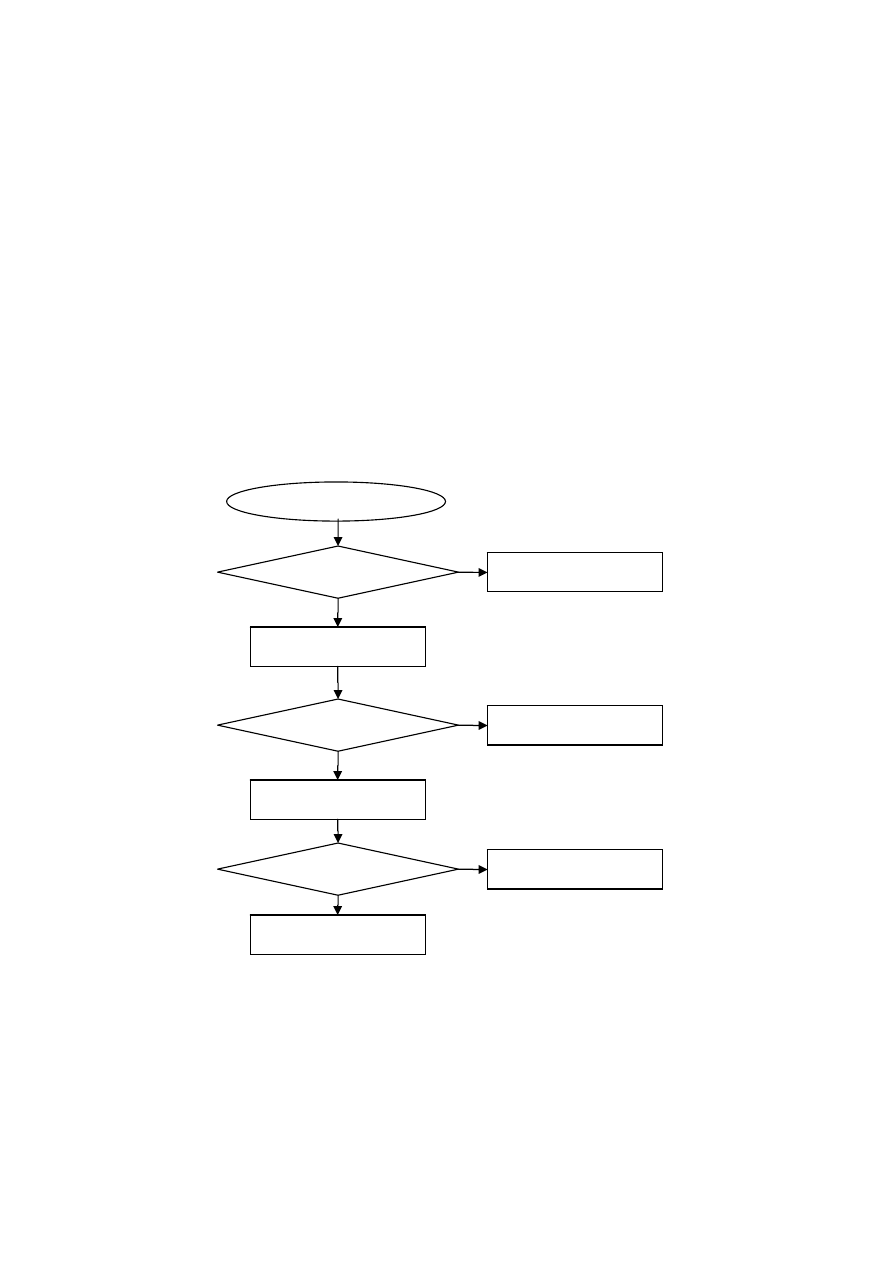

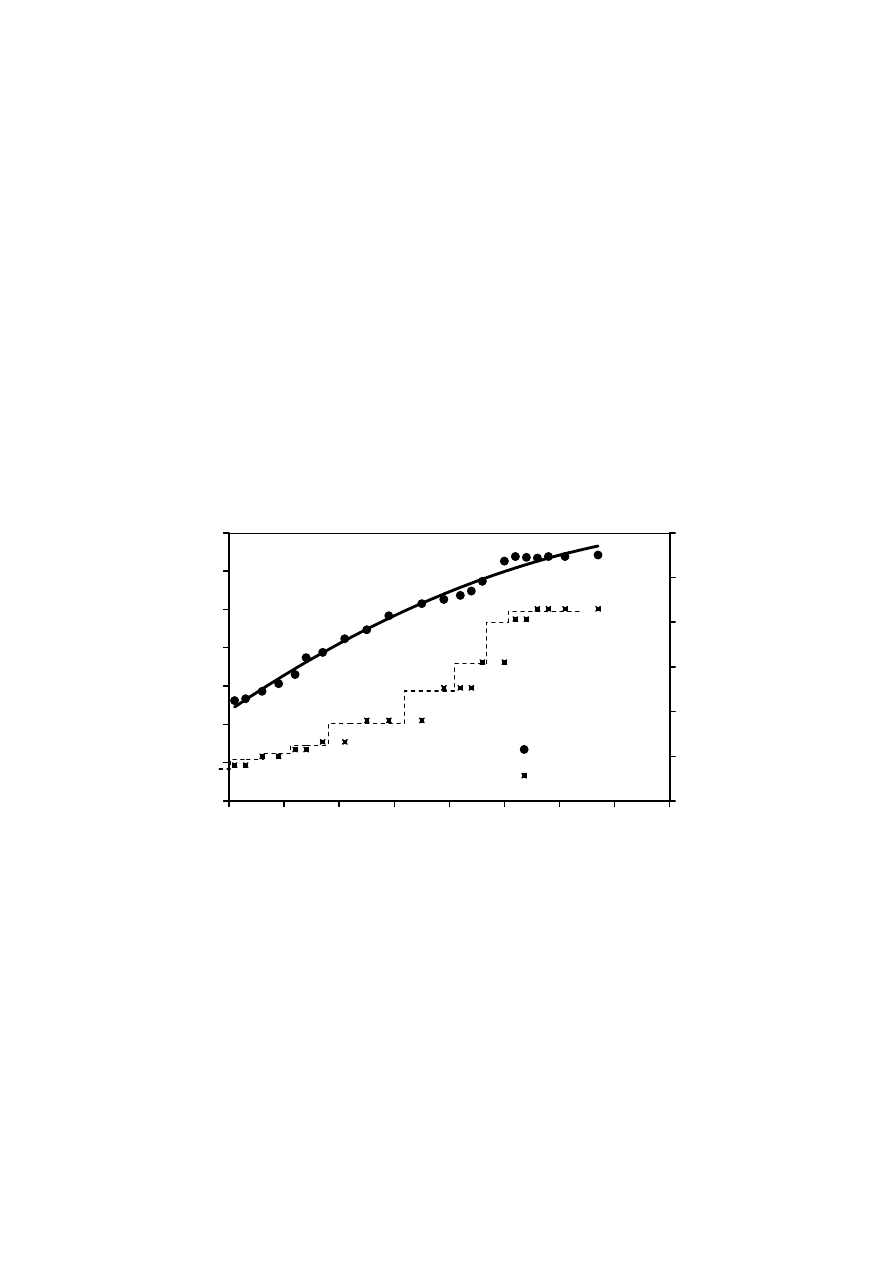

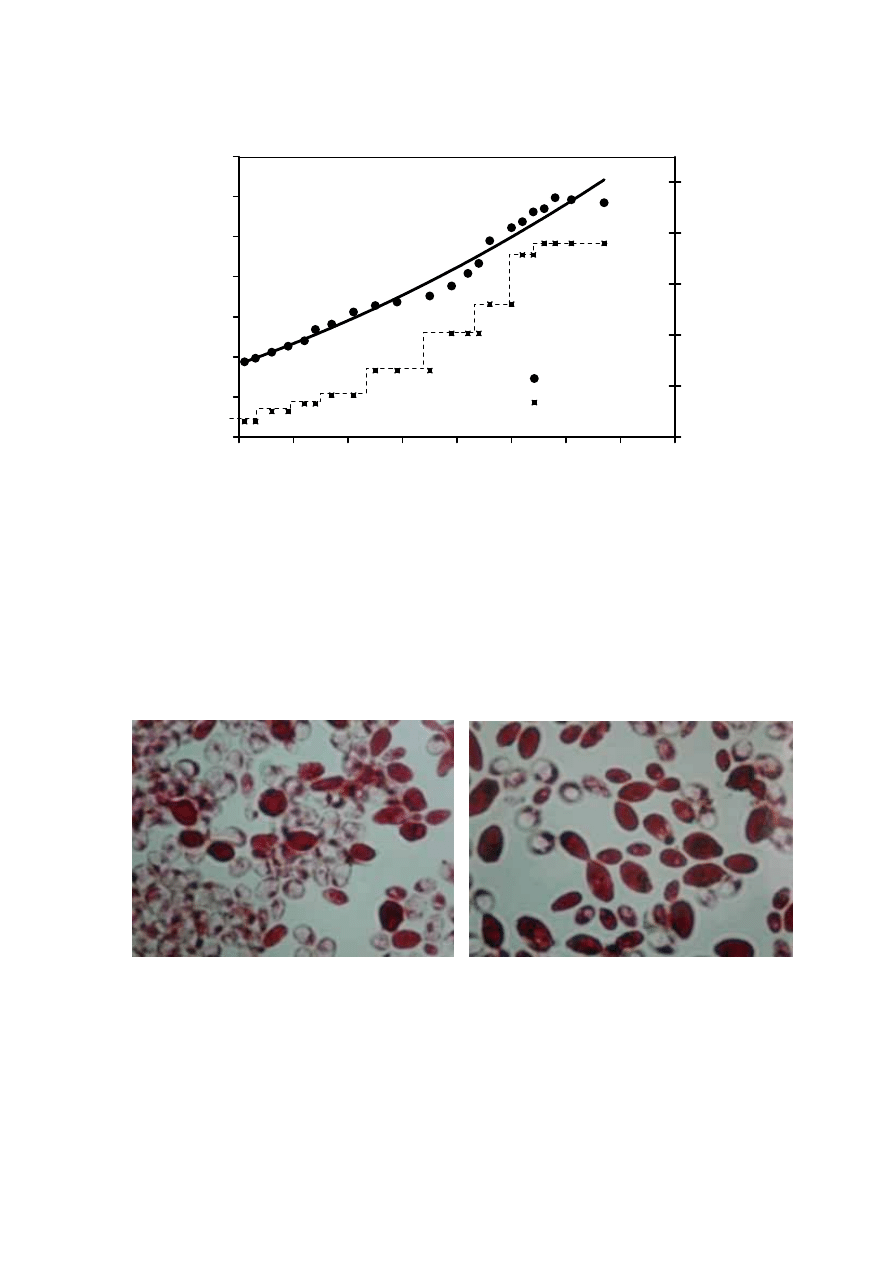

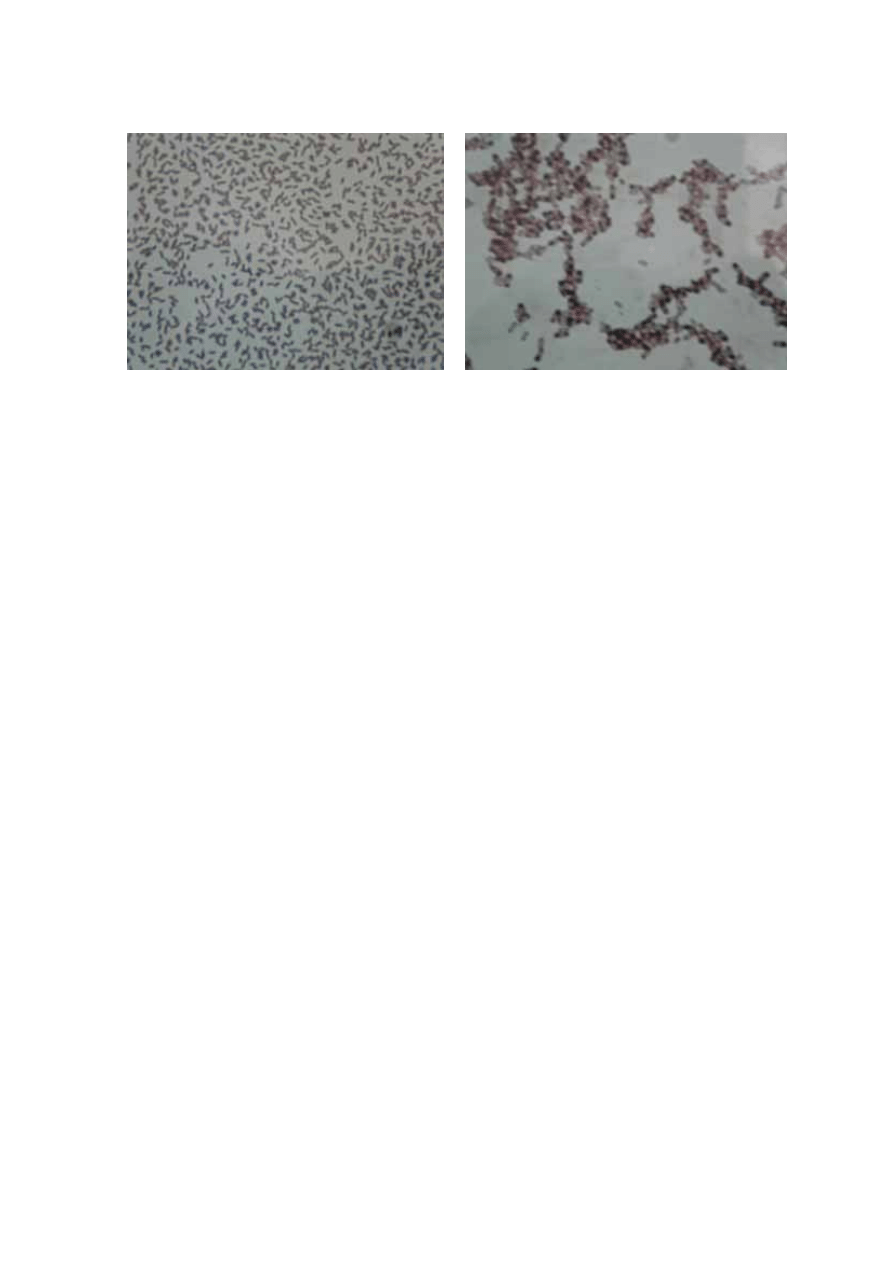

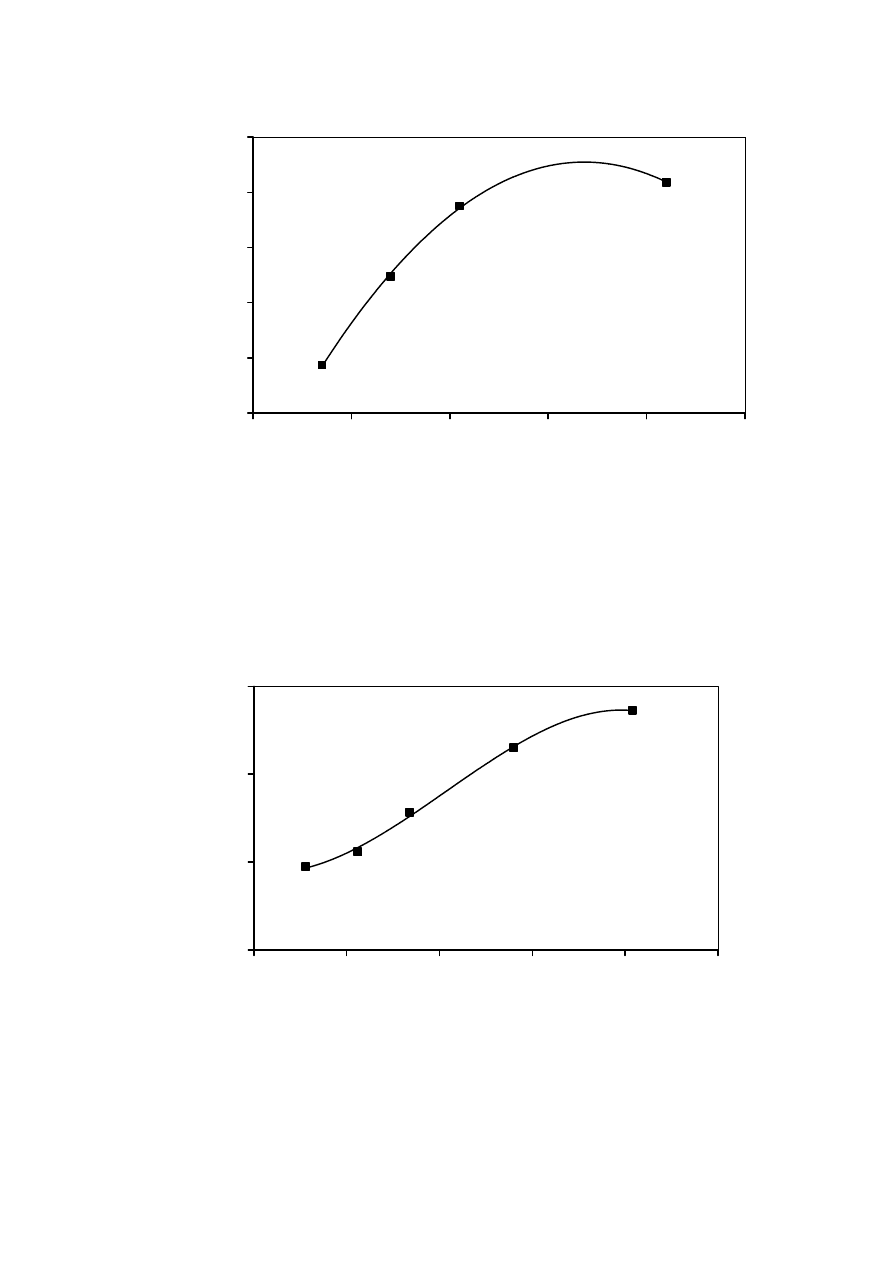

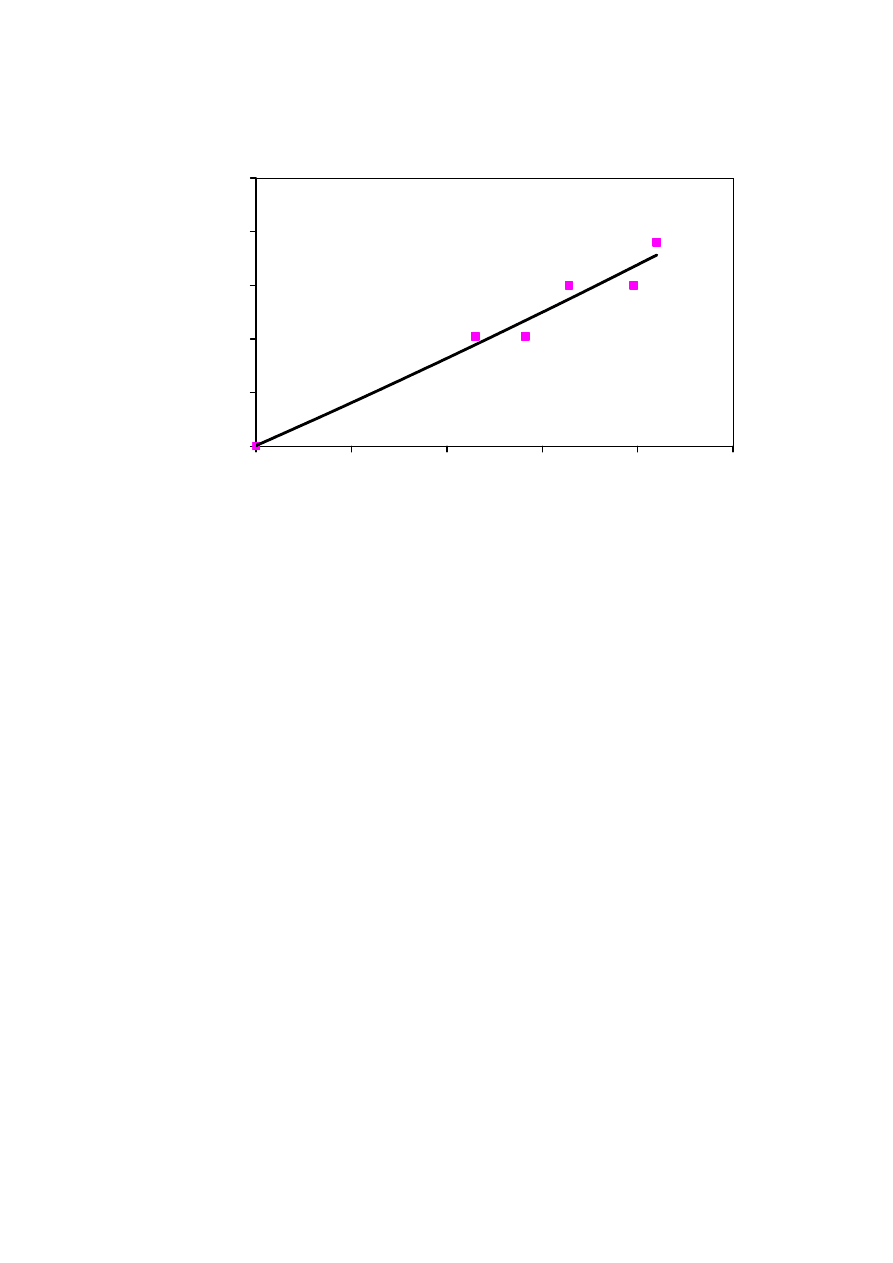

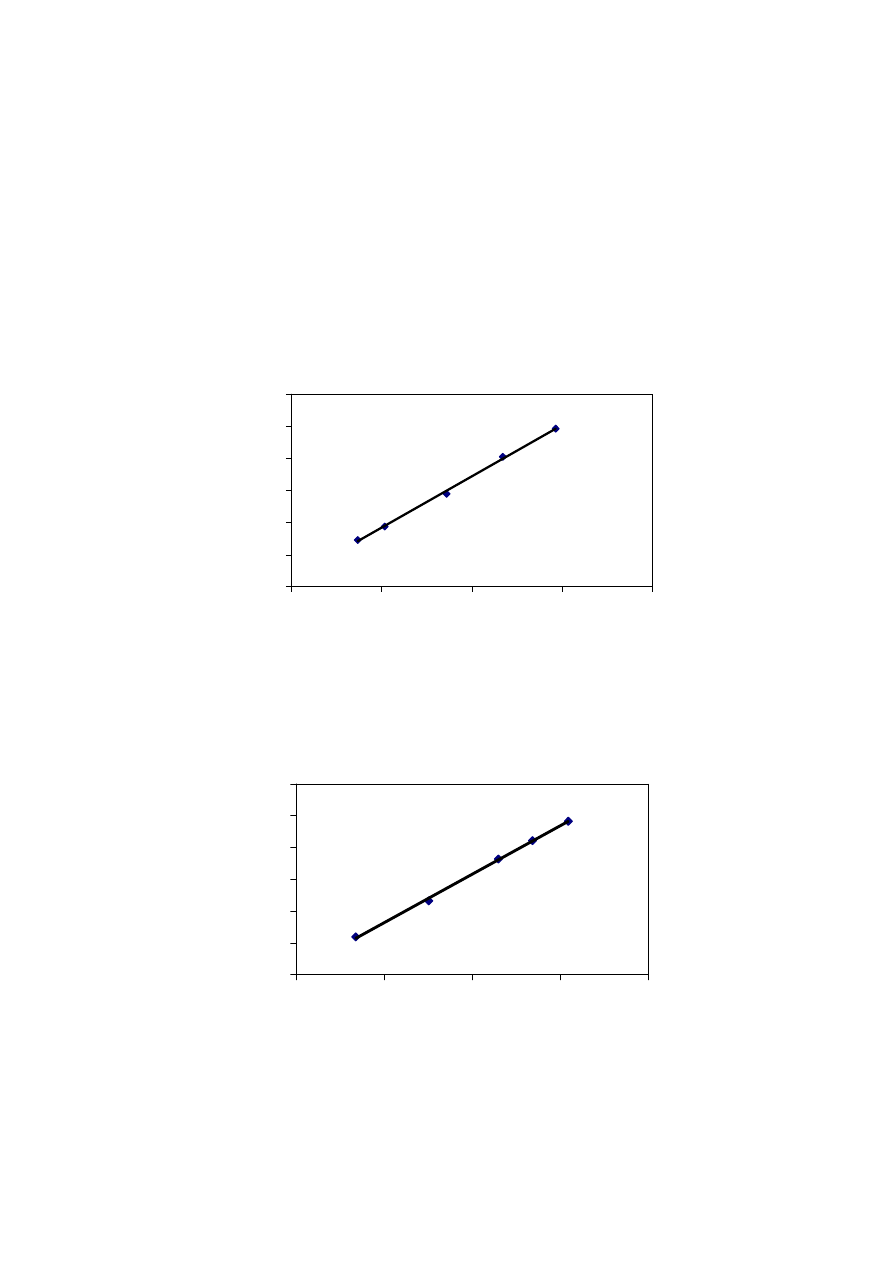

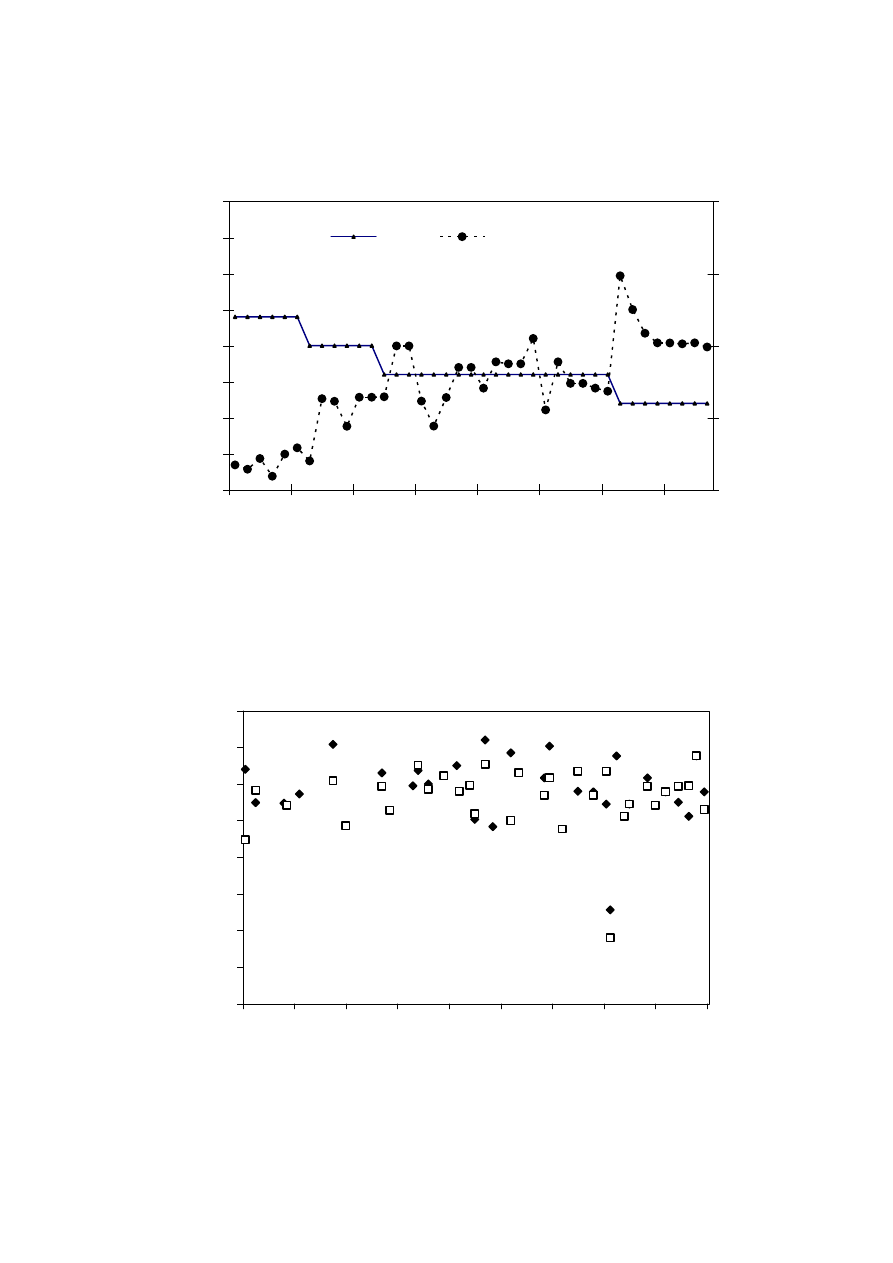

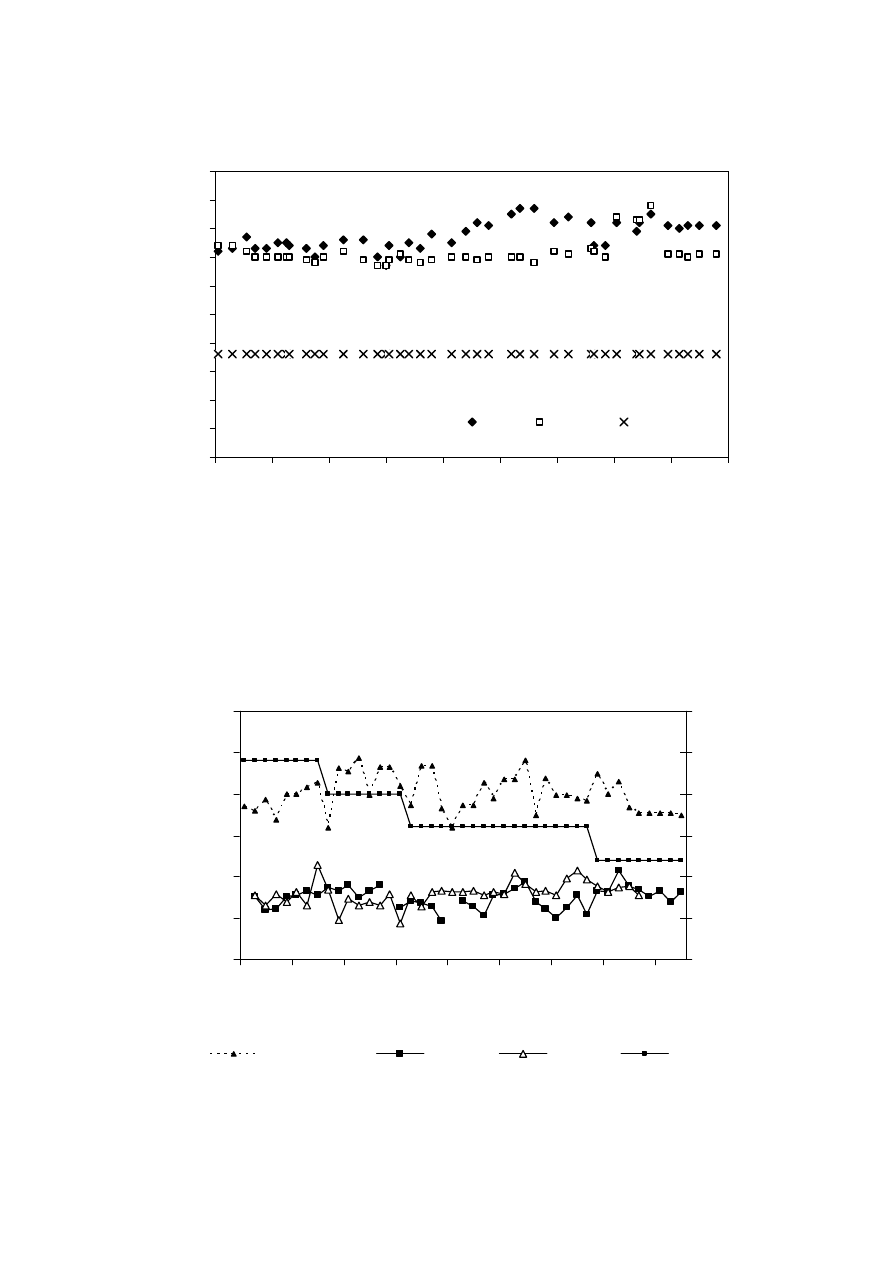

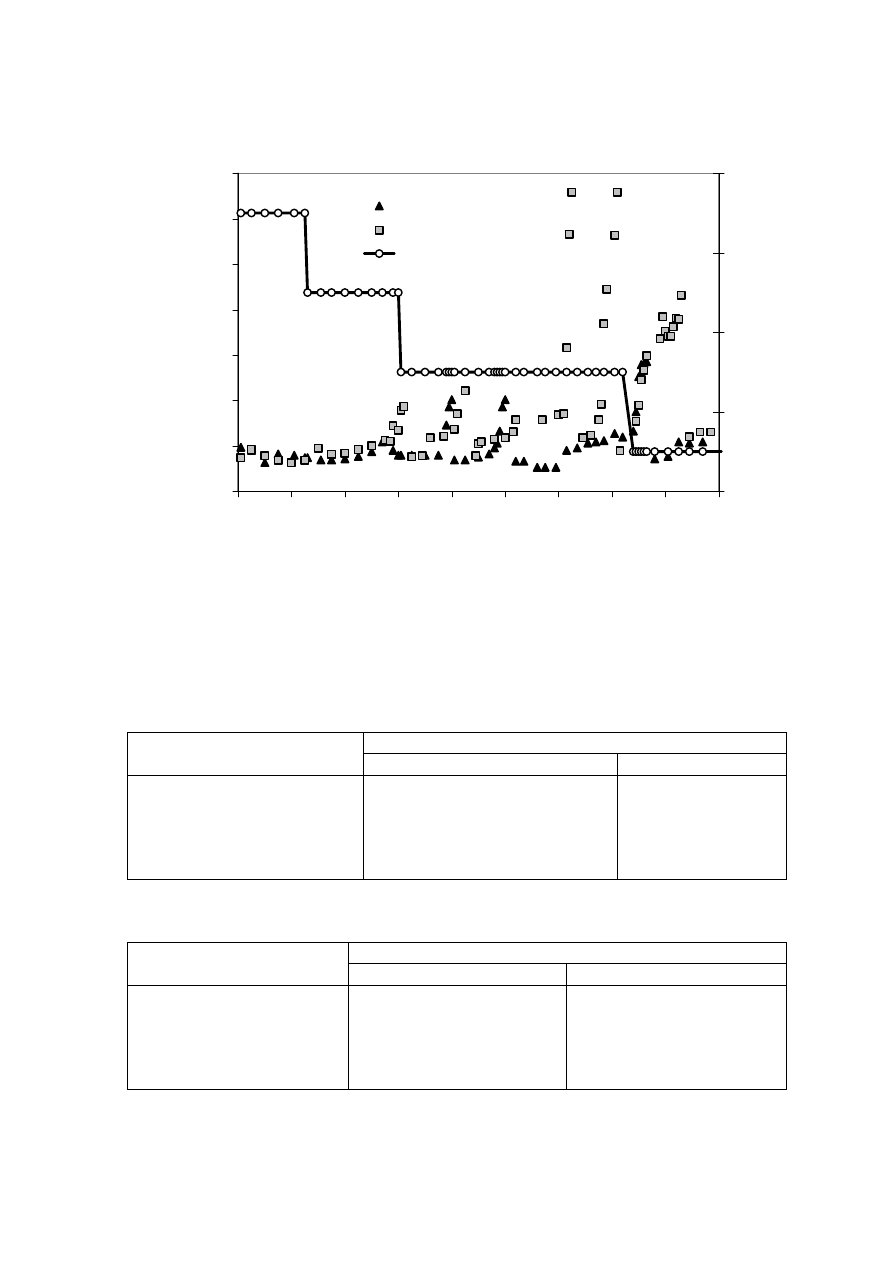

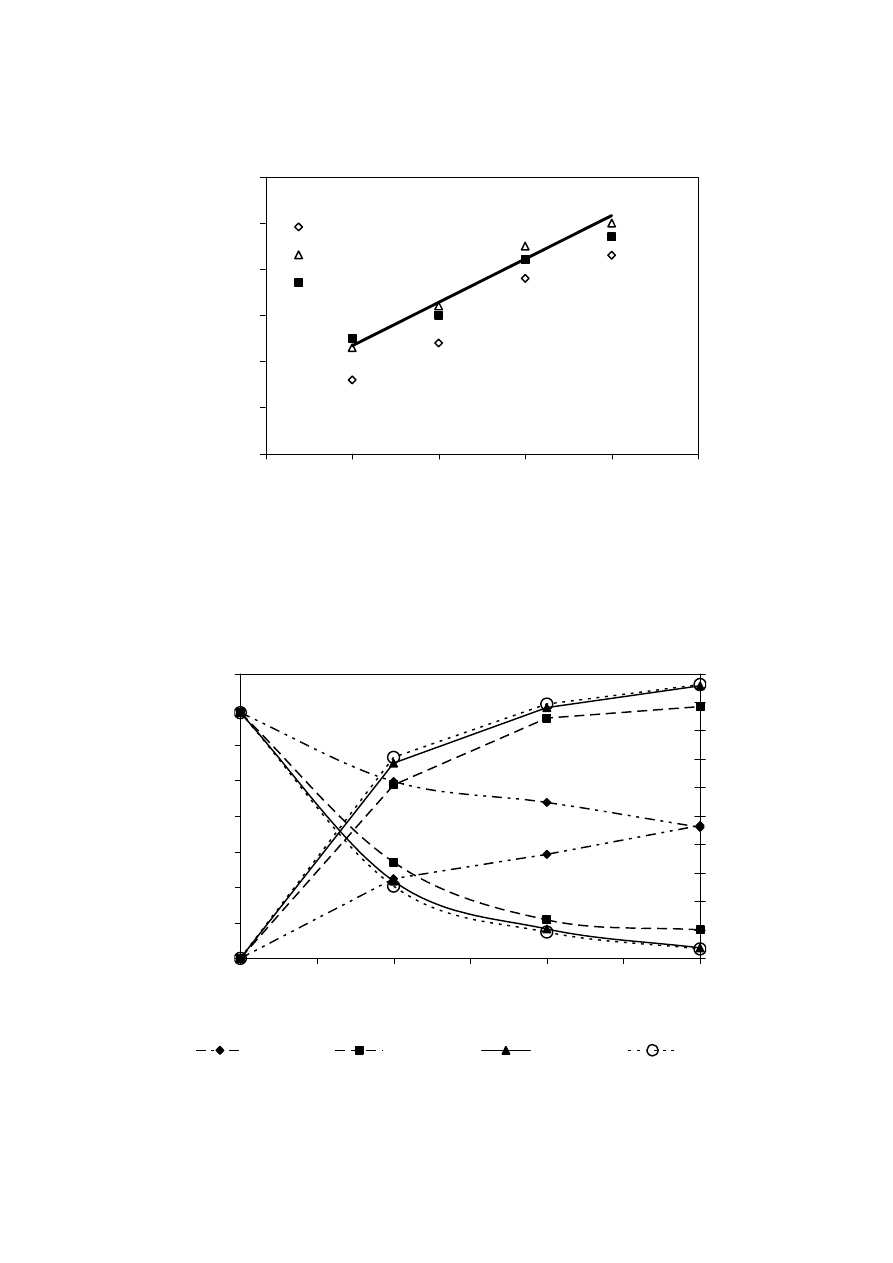

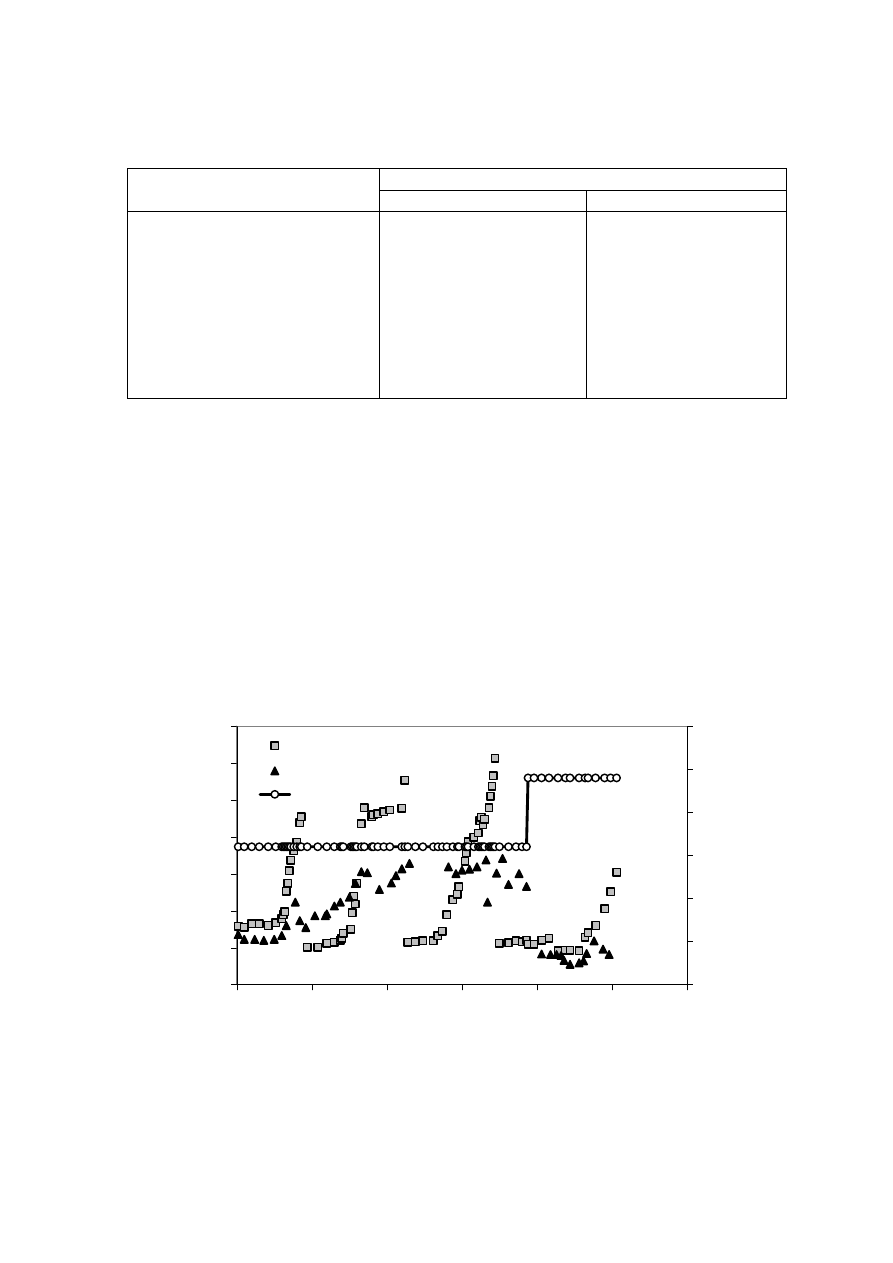

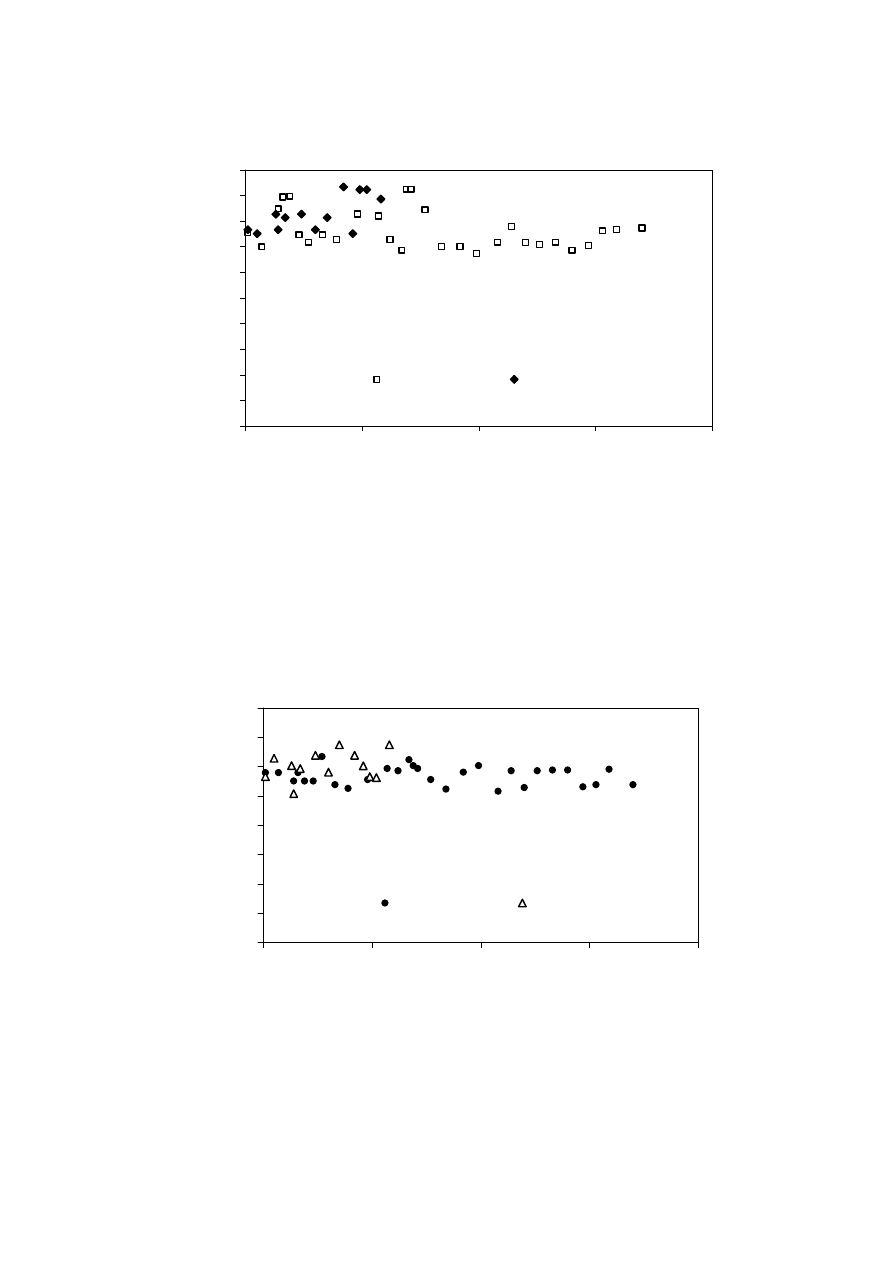

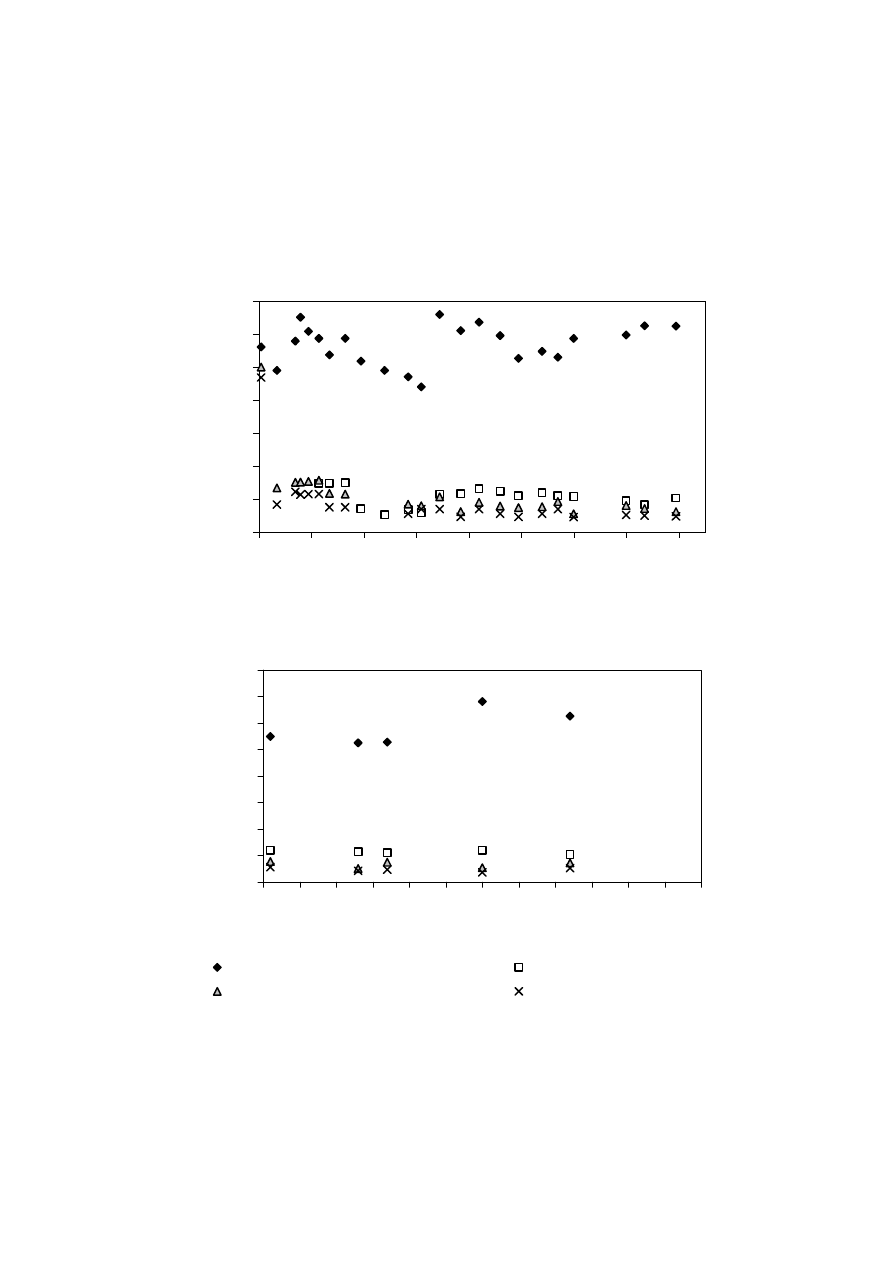

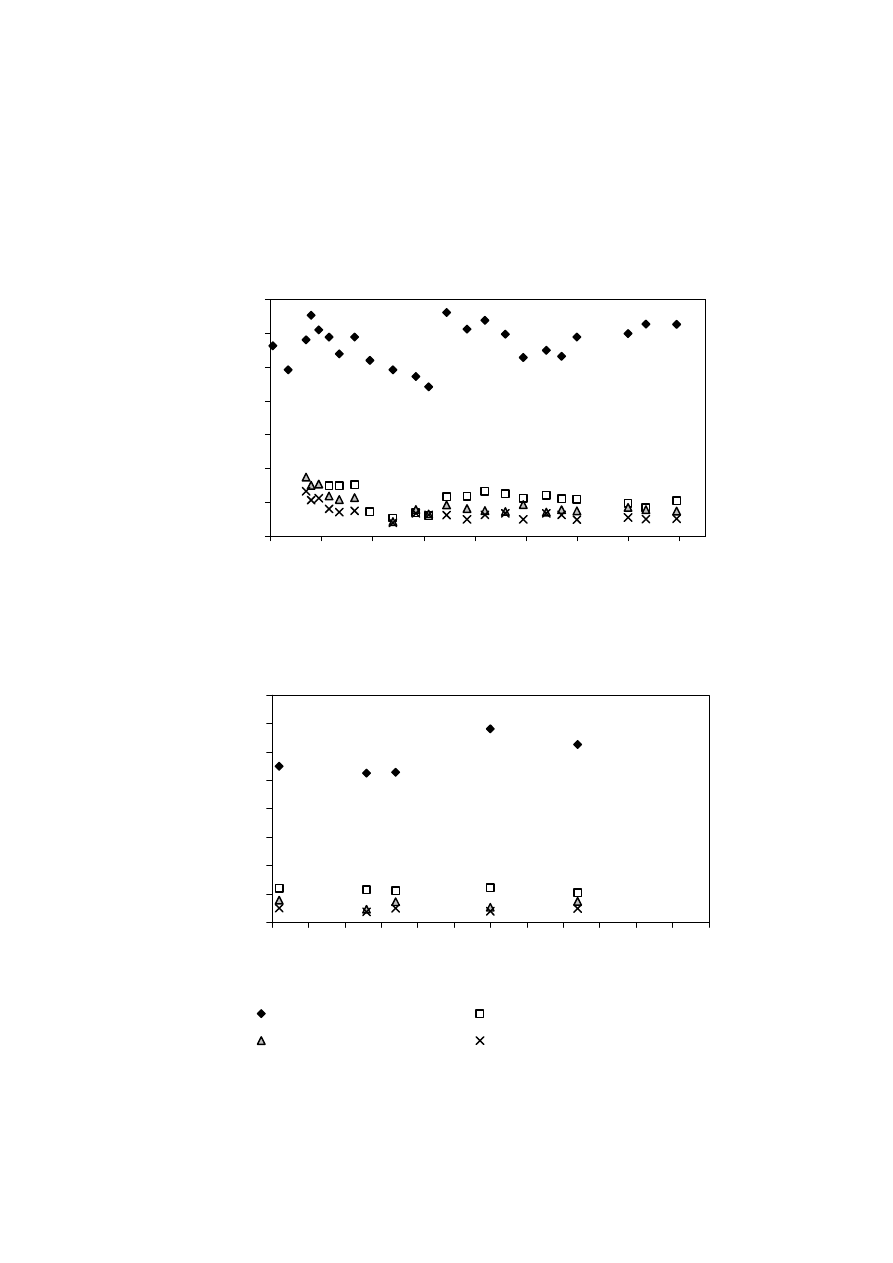

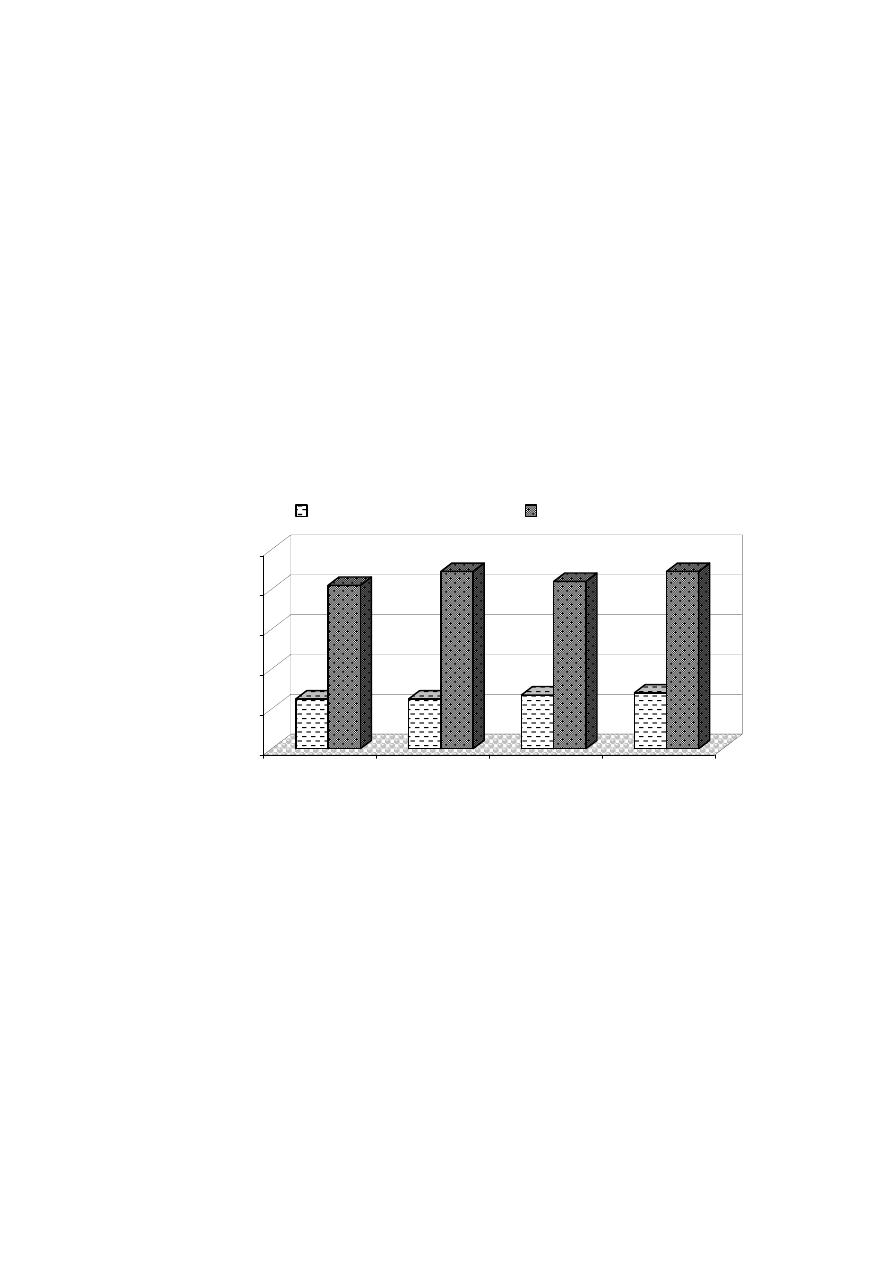

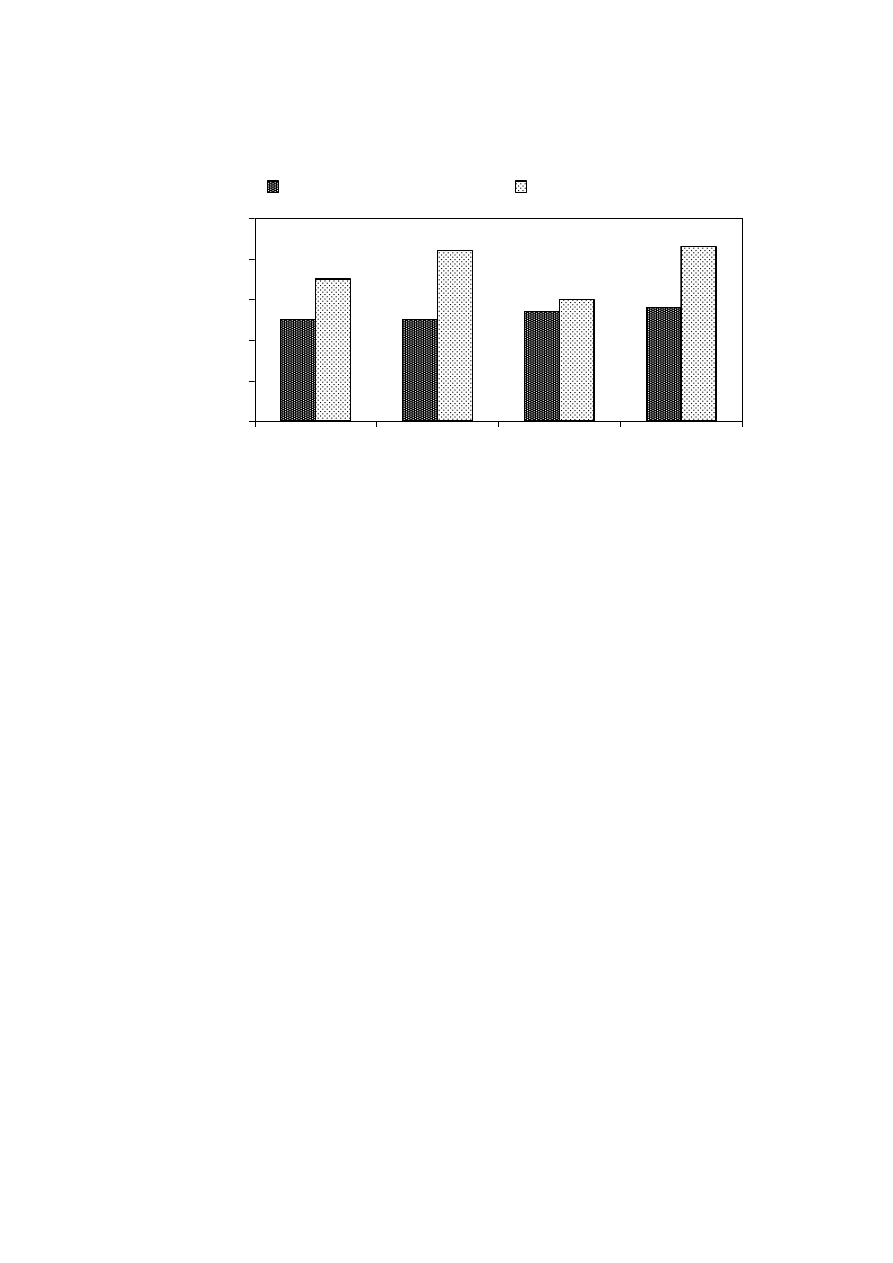

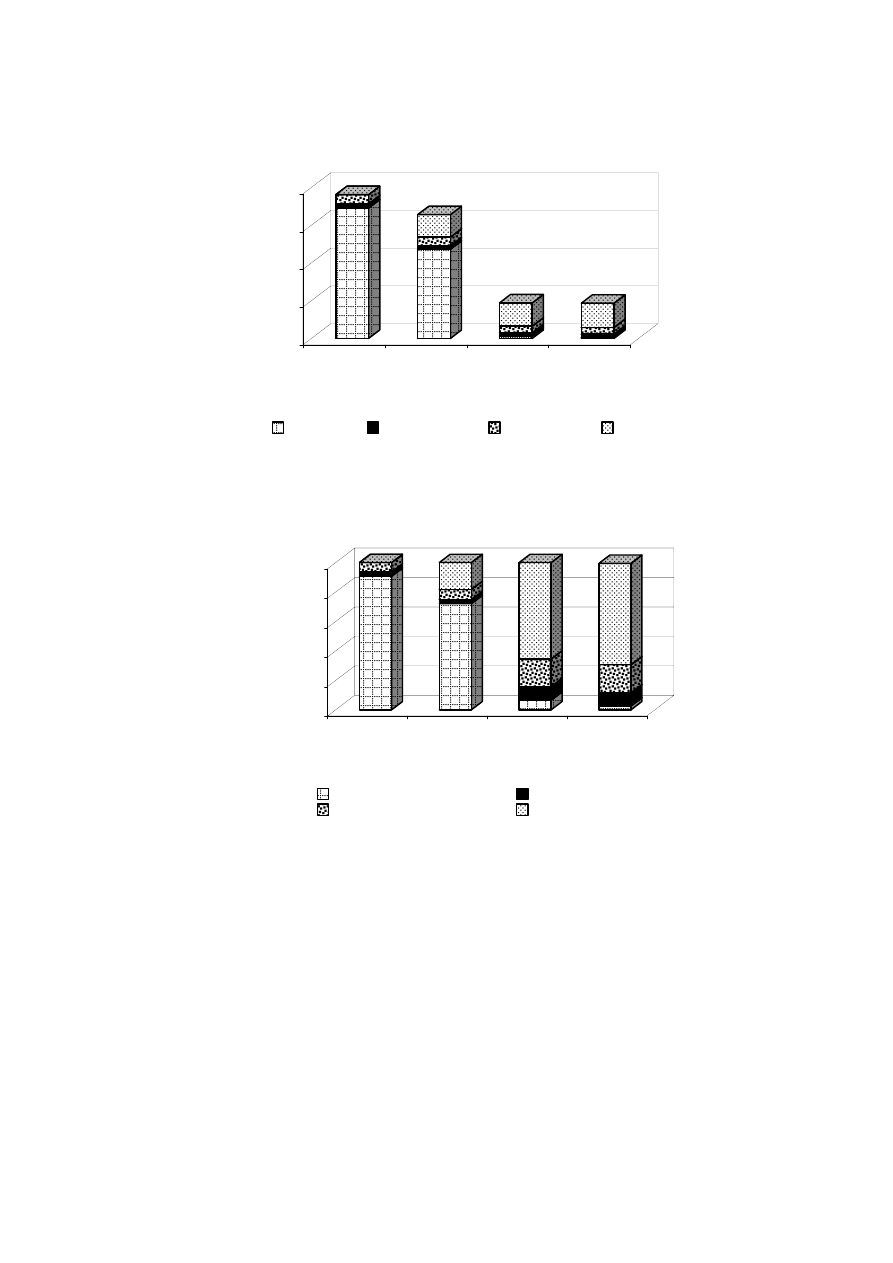

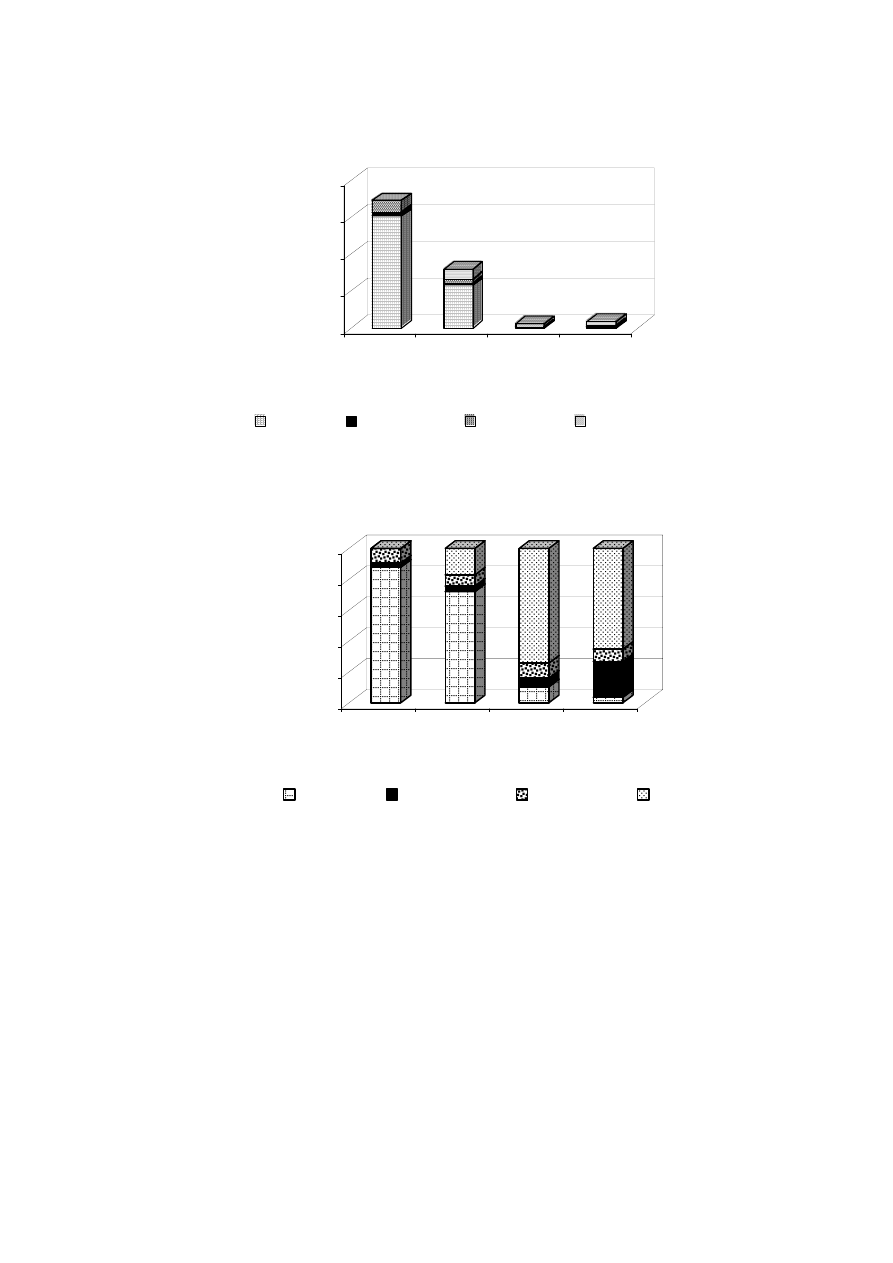

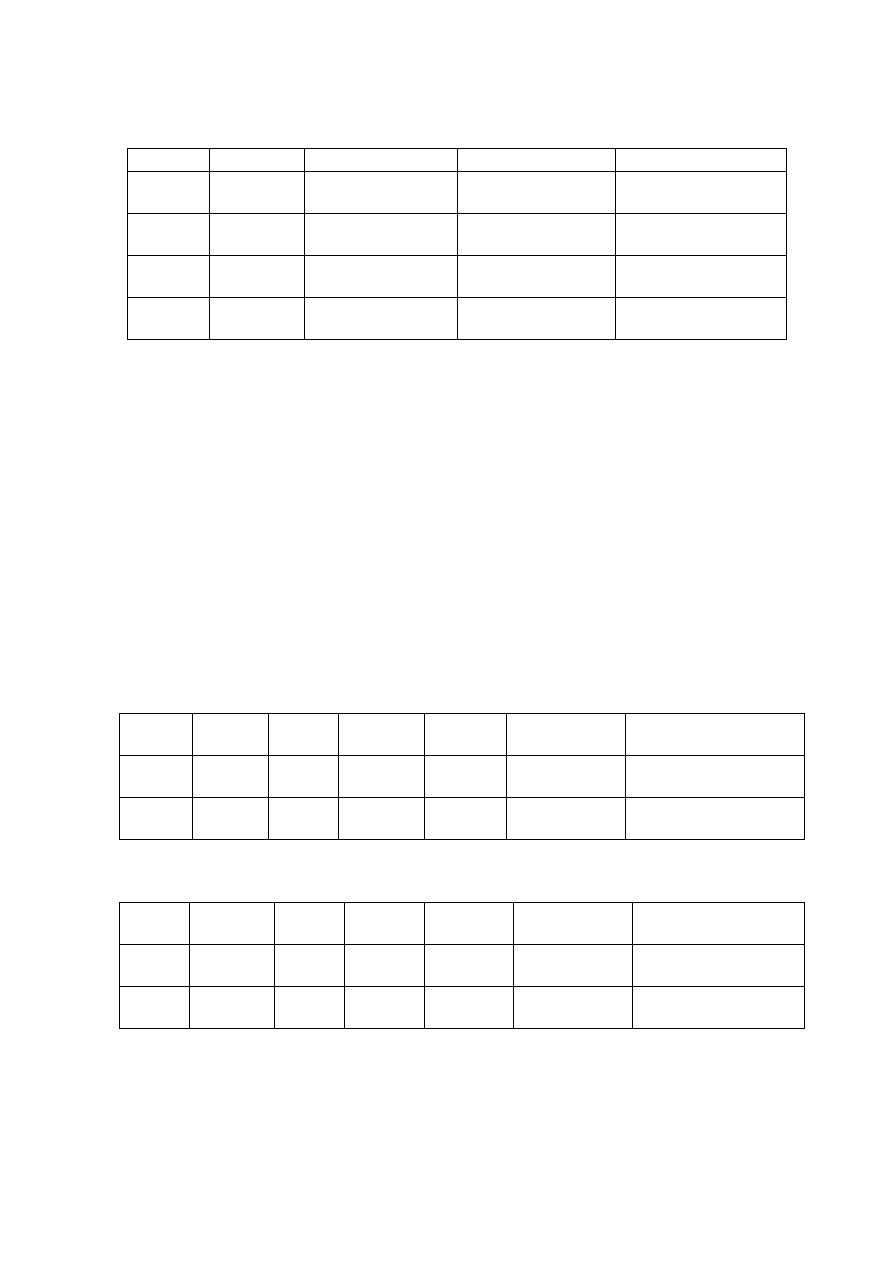

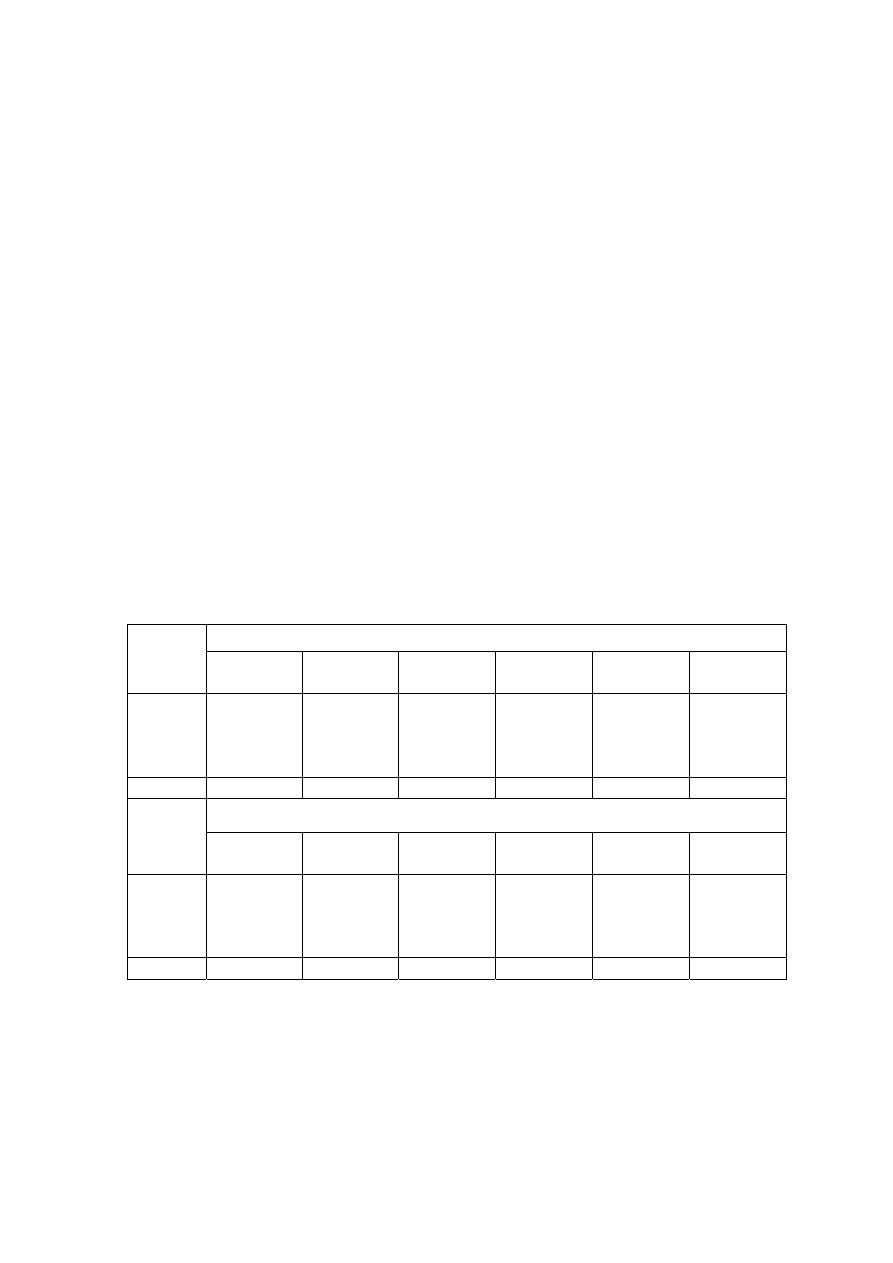

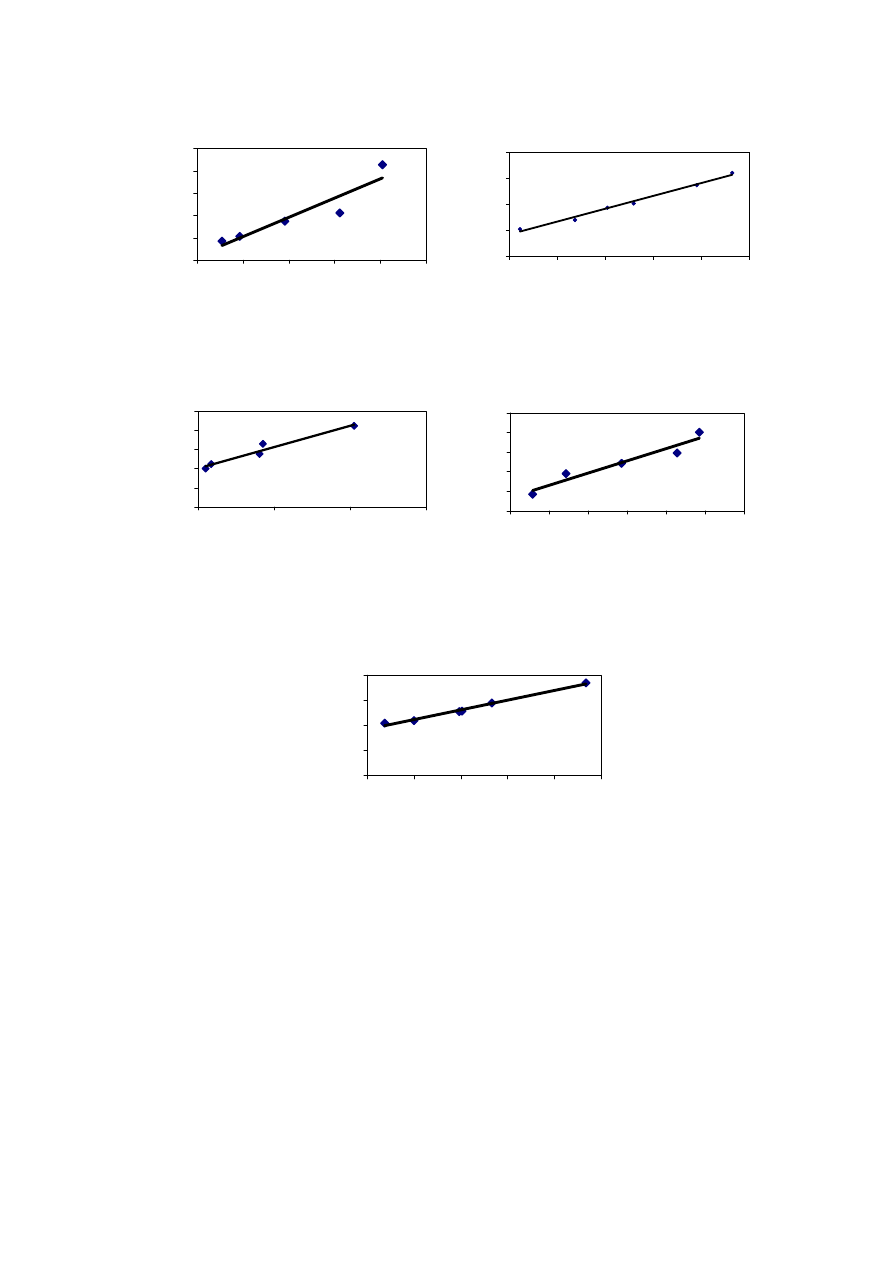

of leachate into the groundwater sources, whilst top covers aid in maintaining moisture