GRAMMAR-

TRANSLATION

METHOD

Małgorzata Szulc-Kurpaska

Grammar-Translation Method

2

The Prussian Method

The effect of the influence of Latin on:

On the way vernacular language were

supposed to be taught

The goals for which Latin was taught,

i.e.literacy and understanding of the classics

An educated person should be able to read

and understand the classics

Such a person should recite the rules of

grammar and proverbs

Grammar-Translation

Method

3

The key to learning a foreign language was

the knowledge of its grammar in the form

of memorized rules learned by heart,

accompanied by declensions and

conjugations

The knowledge of grammar provided

mental gymnastics for the intellect

Rules, i.e. explanations about were

presented first and then examples followed

(deductive presentation)

Grammar-Translation

Method

4

The main form of activity in class was

translation from the target language to

the native language and vice versa

The unit of the material for translation

as well as for the whole method was the

sentence, translation as performad both

orally and in writing

Some proverbs were learned by heart

Grammar-Translation Method

5

The learner’s native language had an

important role to play, it was used as a

medium of instruction

The teaching material contained

classical texts which were to be read

and subjected to grammatical analysis

Reading was emphasized but it was not

contemporary nor communicatively

useful

Grammar-Translation

Method

6

Vocabulary items were presented in the

form of bilingual lists to be memorized.

Verbatim word-for-word learning had an

important role to play in this method

The Reform Movement

7

Modern languages English, German and

French entered school curricula in the

18th century

They were taught in the Grammar-

Translation Method which caused

dissatisfaction with the results

The Reform Movement

8

-the primacy of spoken language and oral-based

methodology

-learners should first hear the language before they see

its written form

-the importance of phonetics and phonology

(International Phonetic Association was founded in 1886)

-the use of the target language for instruction

(translation should be avoided)

-teaching vocabulary in the context

-inductive grammar teaching (from examples to a rule)

rules after practice of grammar points in context

The Direct Method

9

The Direct Method originated in a

desire to do something that the schools

of the time were not doing, to teach

foreign languages as practical skills for

everydaypurposes of social behaviour

‘Direct’ comes from the absence of any

mediating role of grammar, translation

or dictionary

The Direct Method

10

The emphasis in this method was on

speaking and listening.

Correct pronunciation was of primary

importance

The forms of actvity were oral,

especially dialogues and question-and-

answer exchanges

The Direct Method

11

New material was first introduced orally

Vocabulary was chosen on the basis of

its practicality and its meaning was

demonstrated directly, with the use of

objects, pictures and gestures

Grammar of the target language was

taught inductively in a variety of oral

activities

The Direct Method

12

Never translate – demonstrate

Never explain – act

Never make a speech – ask questions

Never imitate – correct

Never speak in single words – use sentences

Never speak too much – make students

speak

Never use the book – use your lesson plan

Never jump around – follow your plan

The Direct Method

13

Never go too fast – keep the pace of the

student

Never speak too slowly – speak normally

Never speak too quickly – speak

naturally

Never speak too loudly – speak naturally

Never be impatient – take it easy

Markedness

14

In Markedness Differential Hypothesis,

markedness is defined in the following terms:

‘A phenomenon or structure X in some language

is relatively more marked than some other

phenomenon or structure Y if cross-linguistically the

presence of X in a language implies the presence of

Y, but the presence of Y does not imply the

presence of X’ (Eckman, 1985:290).

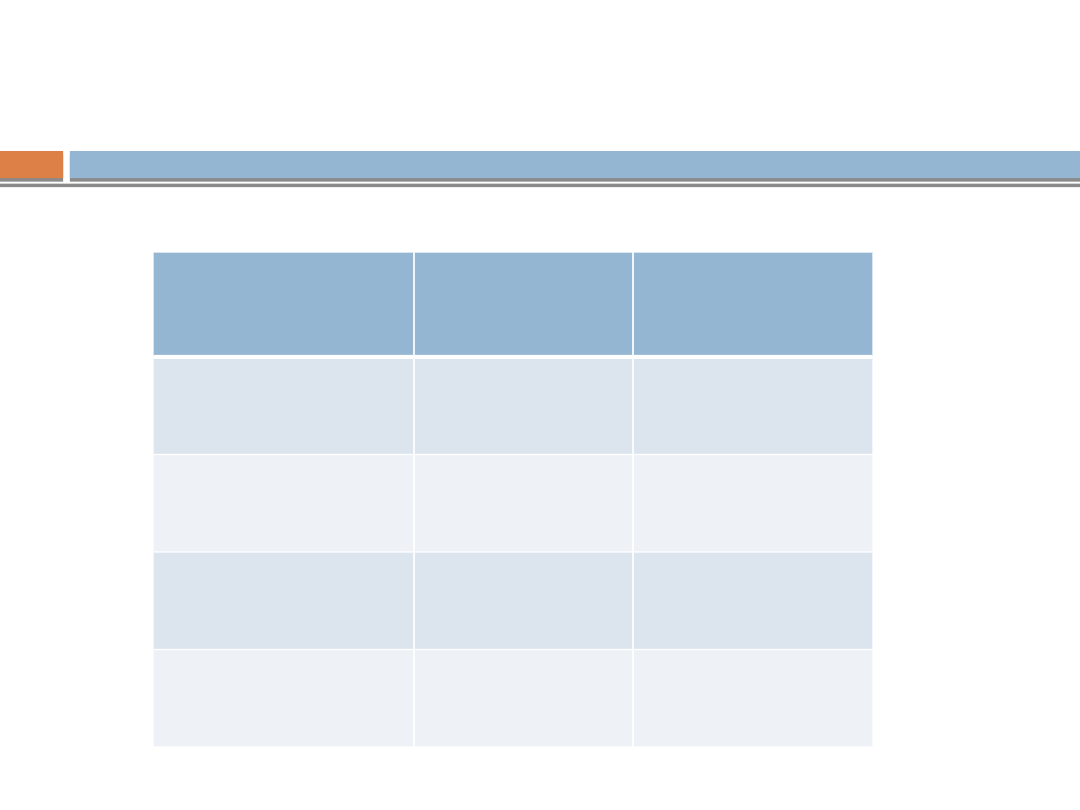

Markedness and L1

transfer

15

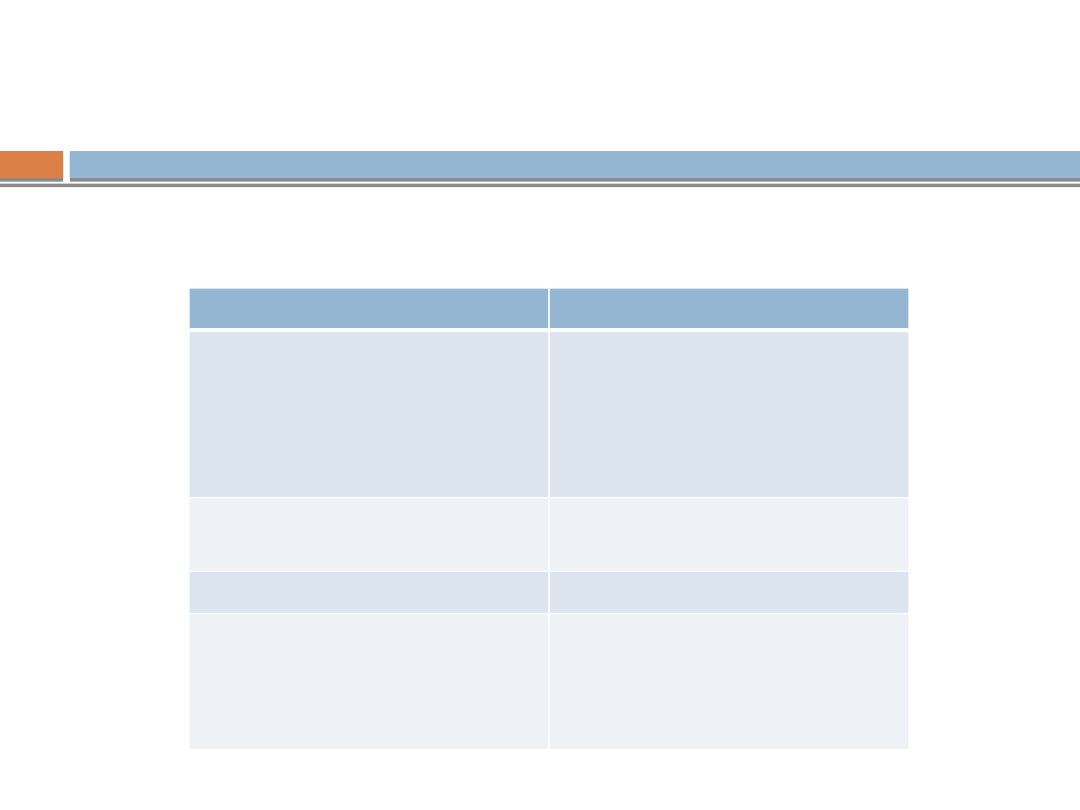

Native

language (L1)

Target

language

(L2)

Interlanguage

1 unmarked

unmarked

unmarked

2 unmarked

marked

unmarked

3 marked

unmarked

unmarked

4 marked

marked

unmarked

Markedness and L1 transfer

16

Markedness theory can help explain why some

differences between the native and the target language

lead to learning difficulty, while other differences do not.

The basic assumption is that unmarked settings of

parameters will occur in interlanguage before marked

settings, even if the L2 provides evidence of a marked

setting (as in case 4).

Thus it is predicted that no transfer will take place from

native to target language when L1 has a marked setting

(cases (3) and (4)).

The most obvious case of transfer is (2), where the

native language shows an unmarked setting and the

target language a marked one.

Universal Grammar and Typology

17

L1 unmarked forms are transferred into interlanguage.

L1 marked forms are not transferred into interlanguage.

Both the Typological approach and the Universal

Grammar approach have generated useful predictions

about the course of interlanguage and the influence of

the first language.

Language acquisition proceeds by mastering easier

unmarked properties before the more difficult marked

ones. There seem to be exceptions, however, in the

early stages of acquisition and where both first-

language and target-language constructions are

marked.

The Acculturation Model

18

Acculturation is defined by Schumann as ‘the

process of becoming adapted to a new

culture’.

is seen as an important aspect of SLA, because

language is one of the most observable

expressions of culture

and because in second language settings the

acquisition of a new language is seen as tied to

the way in which the learner’s community and

the target language community view each

other.

The Acculturation Model

19

The central premise of the Acculturation Model is:

... second language acquisition is just one aspect

of acculturation and the degree to which a

learner acculturates to the target language group

will control the degree to which he acquires the

second language. (Schumann, 1978:34).

Schumann, J. 1978. ‘The acculturation model for

second language acquisition’ in R. Gingras, ed.

Second Language Acquisition and Foreign

Language Teaching. Arlington, VA.: Center for

Applied Linguistics.

Social and psychological distance

20

Acculturation, and hence SLA, is determined by the degree

of social and psychological distance between the learner and

the target language culture.

Social distance is the result of a number of factors which

affect the learner as a member of a social group in contact

with the target language group.

Psychological distance is the result of various affective

factors which concern the learner as an individual. The social

factors are primary. The psychological factors come into play

in cases where the social distance is indeterminant (i.e.

where social factors constitute neither a clearly positive nor

a clearly negative influence on acculturation).

Social distance

An example of a ‘good’ learning situation is when:

the target language and L2 groups view each other as socially

equal;

the target language and L2 groups are both desirous that the L2

group will assimilate;

both the target language and L2 groups expect the L2 group to

share social facilities with the target language group (i.e. there is

low enclosure);

the L2 group is small and not very cohesive;

the L2 group’s culture is congruent with that of the target

language group;

both groups have positive attitudes to each other;

the L2 group envisages staying in the target language area for

an extended period.

21

Psychological distance

22

The psychological factors are affective in nature:

language shock (i.e. the learner experiences

doubt and possible confusion when using the

L2);

culture shock (i.e. the learner experiences

disorientation, stress, fear, etc. as a result of

differences between his or her own culture and

that of the target language community);

motivation;

ego boundaries.

Pidginization Hypothesis

23

When social and/or psychological distances are

great, the learner fails to progress beyond the

early stages, with the result that his language is

pidginized. Schumann refers to this account of

SLA as the pidgnization hypothesis.

Forms observed in pidgins:

‘no+V’ negatives,

uninverted interrogatives,

the absence of possessive and plural inflections,

and restricted verb morphology.

Pidginization Hypothesis

24

Schumann suggests ‘pidginisation may

characterise all early second language

acquisition and ... under conditions of social and

psychological distance it persists (1978a:110).

When pidginisation persists the learner fossilises.

That is, he no longer revises his interlanguage

system in the direction of the target language.

Thus early fossilisation and pidginisation are

identical processes. Thus continued pidginisation

is the result of social and psychological distance.

Pidginization Hypothesis

25

The degree of acculturation leads to

pidgin-like language in two ways:

it controls the level of input that the

learner receives;

it reflects the function which the learner

wishes to use the L2 for

Functions of language

26

Schumann distinguishes three broad functions

of language:

the communicative function, which concerns

the transmission of purely referential,

denotative information;

the integrative function, which involves the

use of language to mark the speaker as a

member of a particular social group;

the expressive function, which consists of the

use of language to display linguistic virtuosity

(e.g. in literary uses).

The Nativisation Model

27

Andersen sees SLA as the result of two general forces

which he labels nativisation and denativisation.

Nativisation consists of assimilation; the learner

makes the input conform to his own internalised view

of what constitutes the L2 system.

The learner simplifies the learning task by building

hypotheses based on the knowledge he already

possesses (e.g. knowledge of his first language).He

attends to an ‘internal norm’.

Nativisation is apparent in pidginisation and the early

stages of both first and second language acquisition.

The Nativisation Model

28

Denativisation involves accommodation (in the

Piagetian sense); the learner adjusts his

internalised system to make it fit the input.

The learner makes use of inferencing strategies

which enable him to remodel his interlanguage

system in accordance with the ‘external norm’

(i.e. the linguistic features represented in the

input language).

Denativisation is apparent in depidginisation (i.e.

the elaboration of a pidgin language which

occurs through the gradual incorporation of forms

from an external language source) and also later

first and second language acquisition.

The Nativisation Model

29

Nativisation

Denativisation

Growth independent of

the external norm

Assimilation

Accommodation

Growth towards an

external norm

Restricted access to

input

Adequate access to

input

Pidginisation

Depidginisation

creation of a unique

first/second language

acquisition

first/second language as

increasing

approximation towards

external ‘target’ norm

Accommodation Theory

30

Giles’s primary concern is to investigate how

intergroup uses of language reflect basic social

and psychological attitudes in interethnic

communication.

the relationship that holds between the learner’s

social group (termed the ‘ingroup’) and the

target language community (termed the

‘outgroup’).

However, whereas Schumann explains these

relationships in terms of variables that create

actual social distance, Giles does so in terms of

perceived social distance

Accommodation Theory

31

Whereas for Schumann social and

psychological distance are static (or at

least change only slowly over time),

for Giles intergroup relationships are

dynamic and fluctuate in accordance

with the shifting views of identity held by

each group.

Giles agrees with Gardner (1979) that

motivation is the primary determinant of

L2 proficiency

Accommodation Theory

32

He considers the level of motivation to be a reflex of how individual learners

define themselves in ethnic terms. This is governed by a number of key variables:

Identification of the individual learner with his ethnic group: the extent to which

the learner sees himself as a member of a specific ingroup, separate from his

outgroup;

Inter-ethnic comparison: whether the learner makes favourable or unfavourable

comparisons between his own ingroup and the outgroup; this will be influenced

by the learner’s awareness of ‘cognitive alternatives’ regarding the status of his

own group’s position, for instance when he perceives the intergroup situation as

unfair;

Perception of ethno-linguistic vitality: whether the learner sees his ingroup as

holding a low or high status and as sharing or excluded from institutional power;

Perception of ingroup boundaries: whether the learner sees his ingroup as

culturally and linguistically separate from the outgroup (= hard boundaries) or

as culturally and linguistically related (= soft boundaries);

Identification with other ingroup social categories: whether the learner identifies

with few or several other ingroup social categories (e.g. occupational, religious,

gender) and as a consequence whether he holds adequate or inadequate status

within his ingroup.

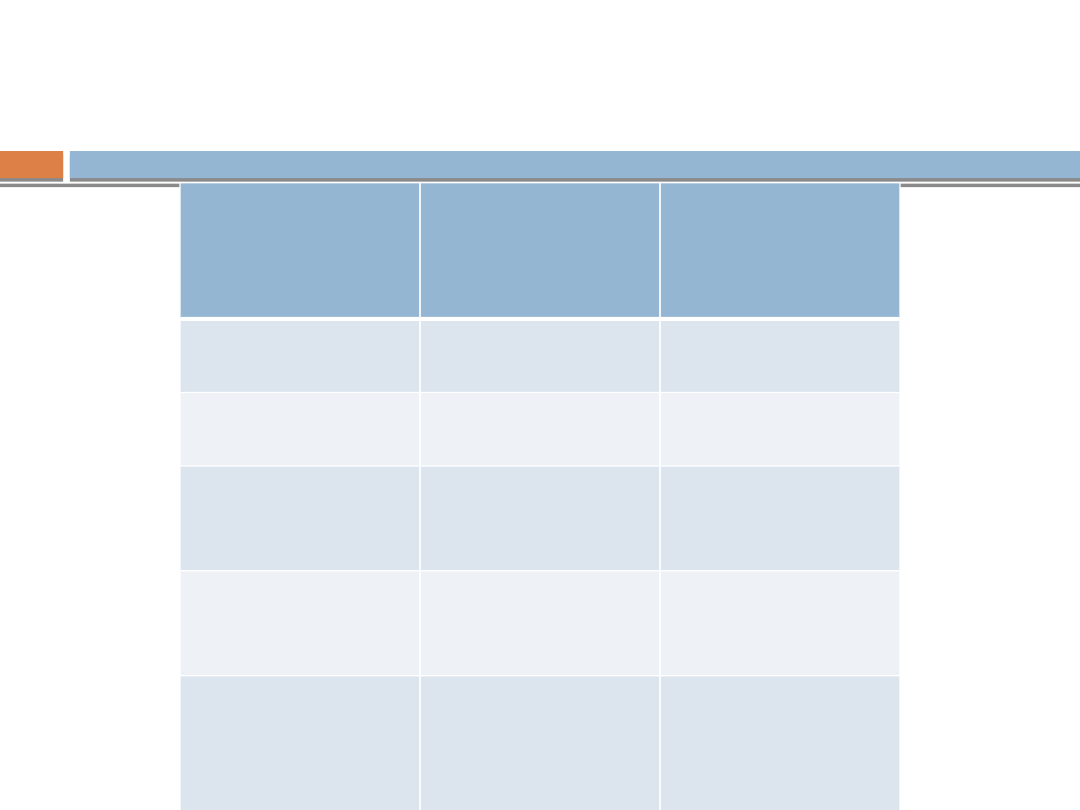

Accommodation Theory

33

Key variables

High

motivation

High

proficiency

Low

motivation

Low

proficiency

Identification

with ingroup

weak

strong

Inter-ethnic

comparison

in-group is not

seen as inferior

in-group is seen

as inferior

Perception of

ethno-linguistic

vitality

low perception

high perception

Perception of

ingroup

boundaries

soft and open

hard and closed

Identification

with other

social

categories

strong

identification –

satisfactory in-

group status

weak

identification –

inadequate in-

group status

The non-systematic variability

34

Native-speaker language use is also characterised by

non-systematic variability. This is of two types:

performance variability is not part of the user’s

competence; it occurs when the language user is

unable to perform his competence.

It is not difficult to find examples of free variation,

although the examples are likely to be idiosyncratic.

For example, I sometimes say [ofn] and sometimes

[oftn]. Or I have used ‘variation’ and ‘variability’

interchangeably. I alternate between ‘that’ and ‘who’

as subject relative clauses in non-restrictive relative

clauses.

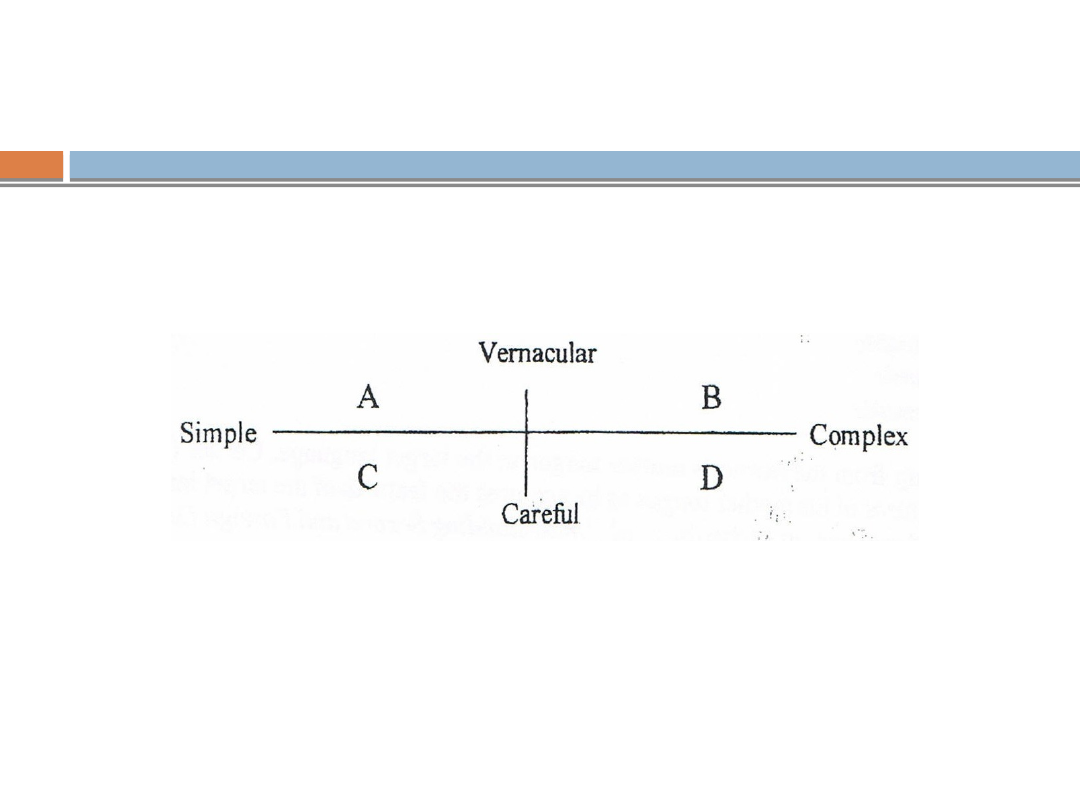

Capability continuum

35

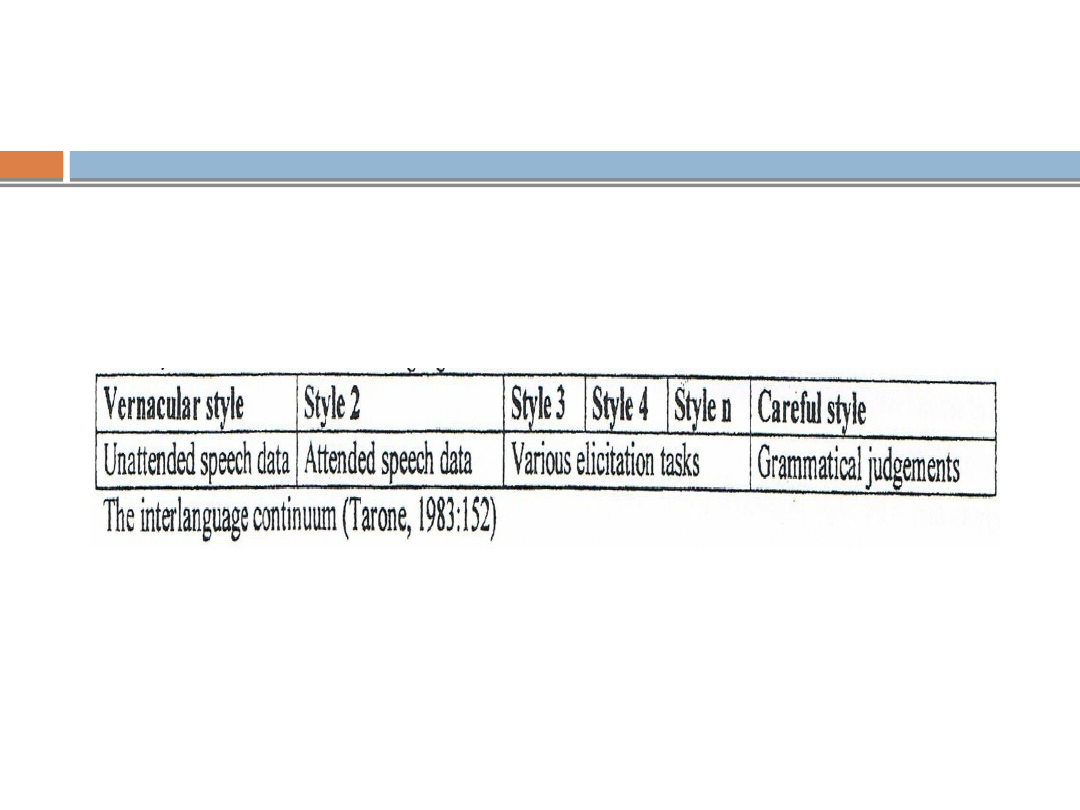

Tarone (1983) represents the effects of situational context as

a continuum of interlanguage styles. At one end of the

continuum is the vernacular style which is called upon when

the learner is not attending to his speech.. This is the style

which is both most natural and most systematic.

At the other end of the continuum is the careful style, which

is most clearly evident in tasks that require the learner to

make a grammatical judgement (e.g. to say whether a

sentence is correct or incorrect). The careful style is called

upon when the learner is attending closely to his speech.

Thus the stylistic continuum is the product of differing

degrees of attention reflected in a variety of performance

tasks. Tarone views the stylistic continuum as competence,

not performance.

Capability continuum

36

Linguistic and situational

context

The effects of the linguistic and situational

context interact to influence jointly the

learner’s use of interlanguage forms.

The linguistic contexts are seen as a

continuum ranging from ‘simple’ (e.g. single

clause utterances for the third person

singular ‘-s’) to ‘complex’ (e.g. subordinate

clauses for the third person singular ‘-s’),

The situational contexts are also viewed as

a continuum from careful to vernacular.

37

Linguistic and situational contexts

38

Capability continuum

In which of the spaces is the third person

present tense ending

–s

most likely to be

used correctly?

C

39

Slajd z punktami

Punkt 1

Podpunkt (wcisnij tab zeby wciac)

Punkt 2 (kolejne punkty dodajesz

enterem)

40

Capability continuum

Tarone, E. 1979. ‘Interlanguage as chameleon’. Language

Learning 29, 181-191.

Tarone cited evidence from the research literature indicating

that learner utterances are systematically variable in at least

two senses:

linguistic context may have a variable effect on the learner’s

use of related phonological and syntactic structures;

the task used for the elicitation of data from learners may

have a variable effect on the learner’s production of related

phonological and syntactic structures.

Tarone maintained that the evidence shows that

interlanguage speech production varies systematically with

context and elicitation task.

41

Non-systematic variability

Ellis’s Variable Competence Model

Ellis has argued that in addition to systematic variability, there is non-systematic variability in

interlanguage. In the early stages of second-language acquisition new forms are used that have

not yet been integrated into the learner’s form-function variation. This process Ellis saw to involve

non-systematic variability in the interlanguage. Systematic variability occurs only when the new

forms have been accommodated by restructuring of the existing form-function system to one that

more closely approximates that of the target language.

Ellis gave the example of a learner who used two different negative rules (no+verb and

don’t+verb) to perform the same illocutionary meaning in the same situational context, in the

same linguistic context, and in the same discourse context. Nor was there evidence for any

difference in the amount of attention paid to the form of the utterance. Ellis argued that the two

forms were in free variation and that such variability in use is non-systematic until reorganisation

phase begins when the forms are distinguished in terms of situational, linguistic, and discourse

use.

Ellis (1986) drew a more “internal” picture of the learner in his variable competence model. Ellis

hypothesised a storehouse of “variable interlanguage rules” depending on how automatic and

how analysed the rules are. He drew a sharp distinction between planned and unplanned

discourse. In order to examine variation. The former implies less automaticity, and therefore

requires the learner to call upon a certain category of interlanguage rules, while the latter, more

automatic production, predisposes the learner to dip into another set of interlanguage rules.

Ellis, R. 1986. Understanding Second language Acquisition. Oxford: OUP.

42

Stages of interlanguage

a stage of random errors, a stage that Corder

called “presystematic”, in which the learner is

only vaguely aware that there is some systematic

order to a particular class of items; examples:

John cans sing.

John can to sing.

John can singing.

(experimentation and inaccurate guessing)

43

Stages of interlanguage

the second emergent stage of interlanguage finds the

learner growing in consistency in linguistic production. The

learner has begun to discern a system and to internalise

certain rules.

L: I go New York.

NS: You’re going to New York?

L: [doesn’t understand] What?

NS: You will go to New York?

L: Yes.

NS: When?

L: 1972

NS: Oh, you went to New York in 1972.

L: Yes, I go 1972.

44

Stages of interlanguage

The third stage is truly a systematic stage in which the learner is

now able to manifest more consistency in producing the second

language. The most salient difference between the second and the

third stage is the ability of learners to correct their errors when

they are pointed out.

L: Many fish are in the lake. These fish are serving in the

restaurants near the lake.

NS: [laughing] The fish are serving?

L: [laughing] Oh, no, the fish are served in the restaurants.

A final stage, which Brown calls the stabilisation stage in the

development of interlanguage systems Corder (1973) called a

“postsystematic” stage. Here the learner has relatively few errors

and has mastered the system to the point that fluency and

intended meanings are not problematic. This fourth stage is

characterised by the learner’s ability to self-correct.

45

Document Outline

- Slide 1

- Grammar-Translation Method

- Grammar-Translation Method

- Grammar-Translation Method

- Grammar-Translation Method

- Grammar-Translation Method

- The Reform Movement

- The Reform Movement

- The Direct Method

- The Direct Method

- The Direct Method

- The Direct Method

- The Direct Method

- Markedness

- Markedness and L1 transfer

- Markedness and L1 transfer

- Universal Grammar and Typology

- The Acculturation Model

- The Acculturation Model

- Social and psychological distance

- Social distance

- Psychological distance

- Pidginization Hypothesis

- Pidginization Hypothesis

- Pidginization Hypothesis

- Functions of language

- The Nativisation Model

- The Nativisation Model

- The Nativisation Model

- Accommodation Theory

- Accommodation Theory

- Accommodation Theory

- Accommodation Theory

- The non-systematic variability

- Capability continuum

- Capability continuum

- Linguistic and situational context

- Linguistic and situational contexts

- Capability continuum

- Slajd z punktami

- Capability continuum

- Non-systematic variability

- Stages of interlanguage

- Stages of interlanguage

- Stages of interlanguage

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

grammar translation method

The Grammar Translation Method

Grammar Translation Method

16 Merkmale der Grammatik Übersetzungs Methode und der ALAV Methodeid 16689

prezentacja techniki tłumaczeniowe w audiovisual translation11, moczulski

Practical grammar, WillimMańczak 104 MODALS, Translate the following into English using an appropria

Methods in Translating Poetry

prezentacja techniki tłumaczeniowe w audiovisual translation1

Grammar Lessons Translating a Life in Spain

25 Methodische Vorgehensweise im Grammatikunterricht

26 Induktive und deduktive Methode bei der Grammatikvermittlung – Vorteile und Nachteile, bevorzugte

prezentacja finanse ludnosci

prezentacja mikro Kubska 2

Religia Mezopotamii prezentacja

Prezentacja konsument ostateczna

Strategie marketingowe prezentacje wykład

motumbo www prezentacje org

więcej podobnych podstron