Research Report

Eur Addict Res 2019;25:10–19

Intravenous Misuse of Methadone,

Buprenorphine and Buprenorphine-Naloxone

in Patients Under Opioid Maintenance Treatment:

A Cross-Sectional Multicentre Study

Fabio Lugoboni

a

Lorenzo Zamboni

a

Mauro Cibin

b

Stefano Tamburin

c

Gruppo InterSERT di Collaborazione Scientifica (GICS)

a

Department of Medicine, Addiction Medicine Unit, Verona University Hospital, Verona, Italy;

b

Department

of Psychiatry and Addictive Behaviours, Local Health Authority Serenissima, Venice, Italy;

c

Department of

Neurosciences, Biomedicine and Movement Sciences, University of Verona, Verona, Italy

Received: July 28, 2018

Accepted: December 5, 2018

Published online: January 9, 2019

Addicti

on

c

R

e

e

s ar h

Stefano Tamburin, MD, PhD

Department of Neurosciences

Biomedicine and Movement Sciences, University of Verona

Piazzale Scuro 10, IT–37134 Verona (Italy)

E-Mail stefano.tamburin

@

univr.it

© 2019 S. Karger AG, Basel

E-Mail karger@karger.com

www.karger.com/ear

DOI: 10.1159/000496112

Keywords

Benzodiazepine · Buprenorphine · Compliance · Concurrent

use · Misuse · Methadone · Mu agonist · Naloxone · Opioid ·

Opioid maintenance treatment · Overdose · Post-marketing

surveillance · Survey study

Abstract

Background: The act of intravenous misuse is common in

patients under opioid maintenance treatment (OMT), but in-

formation on associated factors is still limited. Objectives: To

explore factors associated with (a) intravenous OMT misuse,

(b) repeated misuse, (c) emergency room (ER) admission, (d)

misuse of different OMT types and (e) concurrent benzodi-

azepine misuse. Methods: We recruited 3,620 patients in 27

addiction units in Italy and collected data on the self-report-

ed rate of intravenous injection of methadone (MET), bu-

prenorphine (BUP), BUP-naloxone (NLX), OMT dosage and

type, experience of and reason for misuse, concurrent intra-

venous benzodiazepine misuse, pattern of misuse in relation

to admission to the addiction unit and ER admissions be-

cause of misuse. According to inclusion/exclusion criteria,

2,585 patients were included. Results: Intravenous misuse of

OMT substances was found in 28% of patients with no differ-

ence between OMT types and was associated with gender,

age, type of previous opioid abuse and intravenous benzo-

diazepine misuse. Repeated OMT misuse was reported by

20% (i.e., 71% of misusers) of patients and was associated

with positive OMT misuse experience and intravenous ben-

zodiazepine misuse. Admission to the ER because of misuse

complications was reported by 34% of patients, this out-

come being associated with gender, employment, type of

previous opioid abuse and intravenous benzodiazepine mis-

use. OMT dosage was lower than the recommended mainte-

nance dosage. Conclusions: We offered new information on

factors associated with intravenous OMT misuse, repeated

misuse and ER admission in Italian patients under OMT. Our

data indicate that BUP-NLX misuse is not different from that

of BUP or MET. Choosing the more expensive BUP-NLX over

MET will likely not lead to the expected reduction of the risk

of injection misuse of the OMT. Instead of prescribing new

and expensive OMT formulations, addiction unit physicians

and medical personnel should better focus on patient’s fea-

tures that are associated with a higher likelihood of misuse.

Care should be paid to concurrent benzodiazepine and OMT

misuse.

© 2019 S. Karger AG, Basel

Downloaded by:

Access provided by the University of Michigan Library

141.216.78.40 - 1/10/2019 11:34:42 AM

Misuse in Patients Under OMT

11

Eur Addict Res 2019;25:10–19

DOI: 10.1159/000496112

Introduction

Opioid maintenance treatment (OMT) with metha-

done (MET) or buprenorphine (BUP) increases retention

rate and reduces illicit opioid use, criminal behaviour and

the risk of HIV and viral hepatitis via needle sharing [1–3].

OMT plays a crucial role in the extinction of conditioned

addictive behaviour to opioids because it minimizes with-

drawal symptoms and attenuates the reinforcing effect of

street heroin, leading to its reduction or cessation [4].

Misuse and diversion, which include intravenous or

nasal administration, use of higher dosage, or illicit ac-

quisition, have been reported for OMT [5]. Patients

may prefer MET or BUP via nasal or injection route

because of the much shorter time to peak plasma con-

centration [6] that results in a higher reinforcing effect.

Injection of MET syrup and BUP tablets was reported

by several studies [1, 2, 7–15]. In addition to the nega-

tive effect on the treatment and rehabilitation of opioid

use, injection of MET and BUP raises the concern for

blood-borne infections, unwanted side effects or aller-

gic reactions to compounds that are present in MET

syrup and BUP tablets formulations (e.g., sorbitol or

silica), respiratory depression, local damage at the in-

jection site because larger-gauge needles are often used,

with venous thrombosis and pulmonary side effects [1,

2, 15–17].

Data on the prevalence of MET and BUP injection is

inconsistent across studies, with figures ranging from 5.0

to 35.8% for MET and from 9.1 to 46.5% for BUP [1, 9,

11, 12, 14, 18, 19].

Sublingual combination of BUP and low-dose nalox-

one (NLX) was marketed, assuming that NLX would an-

tagonize the euphoric properties of BUP, or precipitate

withdrawal symptoms in opioid-tolerant people when in-

jected intravenously, thus reducing the risk of diversion

and misuse [19, 20]. In contrast, when used sublingually,

BUP-NLX tablets skip hepatic first pass and offer good

plasma levels of BUP, with low NLX bioavailability result-

ing in low risk of severe and protracted withdrawal symp-

toms [21]. Despite these promising theoretical grounds,

post-marketing studies showed similar rates of injections

for MET and BUP-NLX, either as sublingual tablet or sol-

uble film formulations [22, 23].

According to previous reports, risk factors for OMT

misuse include younger age, risky behaviours associated

with opioid overdose, needle fixation (i.e., the act of in-

jecting becoming compulsive and rewarding), opioid and

benzodiazepine injection, polydrug abuse, self-treatment

of withdrawal symptoms, concurrent pain or psychiatric

symptoms, desire to obtain rapid onset of drug effect and

low OMT dosage [1, 7, 10, 11, 14, 18–20, 23].

Benzodiazepine is frequently co-prescribed with OMT

[24], despite the evidence that it is often misused [5, 25].

The combined use of benzodiazepine and opioid has been

associated with worse outcomes, higher risk of overdose

and admission to the emergency room (ER) and lower

adherence to OMT [26, 27]. Data on the concurrent in-

travenous misuse of benzodiazepine and single OMT ac-

tive principle is scanty [28].

In Italy, OMT is prescribed by public addiction units

that belong to the National Health Service. These addic-

tion units are general ones, in that they offer pharmaco-

logical treatment and rehabilitation to patients with dif-

ferent substance use disorders. Four OMT types may be

prescribed by addiction units in Italy, namely, MET low

concentration (0.1%), MET high concentration (0.5%),

BUP and BUP-NLX.

To offer new information on factors associated with

intravenous OMT injection, we studied a large sample

of patients under OMT recruited from a network of

addiction units in Italy, and collected data on the self-

reported rate of intravenous injection of MET, BUP

and BUP-NLX, OMT dosage and type, experience of

and reason for misuse, concurrent intravenous benzo-

diazepine misuse, pattern of misuse in relation to ad-

mission to the addiction unit, admissions to the ER

because of misuse, as well as demographic and clinical

variables. Among other substances of abuse, we fo-

cused on benzodiazepine because we were interested in

intravenous misuse. The aims of the study were (a) to

obtain reliable measures of intravenous injection of

different OMT types and benzodiazepine, and (b) to

explore factors associated with misuse, (c) repeated

misuse, and (d) admission to the ER because of misuse.

The findings of this study might help defining the

characteristics of the most vulnerable patients and pro-

vide useful information to better address and tailor

OMT.

Materials and Methods

From June to November 2015, 3,620 consecutive patients were

recruited from 27 Italian addiction units that belong to the Gruppo

InterSERT di Collaborazione Scientifica, a scientific collaborative

network dealing with substance use disorders and located in Italy.

The addiction units participating to the Gruppo InterSERT di Col-

laborazione Scientifica offer a wide coverage of the population of

Italian addicted patients. The procedures and treatments were

comparable across the addiction units and representative of stan-

dard care in Italy.

Downloaded by:

Access provided by the University of Michigan Library

141.216.78.40 - 1/10/2019 11:34:42 AM

Lugoboni et al.

Eur Addict Res 2019;25:10–19

12

DOI: 10.1159/000496112

The inclusion criteria were (a) age ≥18 years, (b) having been

on oral MET, BUP, or BUP-NLX treatment for at least 3 months;

(c) willing to participate to the study and to answer the question-

naire on misuse.

The exclusion criteria were (a) severe liver dysfunction, (b) se-

vere renal dysfunction, (c) other organ failure or severe medical

disorders, (d) psychosis, (e) dementia or cognitive impairment.

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Hel-

sinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Verona Uni-

versity Hospital. All patients gave written informed consent for

participation in the study. No benefit was provided for participa-

tion in the study; it was voluntary and confidential.

For all the patients, demographic (gender: male, female; age

class: <

20, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, ≥50; employment status: fully

employed, temporarily employed, unemployed; family status:

living with parents, single, married/engaged, homeless) and clin-

ical variables (type of previous opioid abuse: smoked, snorted,

injected; OMT type: MET 0.1%, MET 0.5%, BUP, BUP-NLX,

OMT dosage: mg) were recorded, based on self-report with an

anonymous questionnaire. Daily oral morphine milligram equiv-

alent dosage was calculated using standard dosage conversion

calculations [29, 30].

Patients were asked to fill an anonymous questionnaire on the

self-reported presence of intravenous injection (yes, no), rate of

repeated misuse (once, 2–20 times, >

20 times), main reason for

misuse (reward/euphoria, reduce withdrawal symptoms, enhance

drug effects), experience related to misuse (positive, negative) of

their current OMT (MET 0.1%, MET 0.5%, BUP, BUP-NLX), con-

current intravenous benzodiazepine misuse (never, once, 2–20

times, >

20 times), temporal pattern of misuse in relation to the ad-

diction unit access (before, after, both), and ER admissions be-

cause of misuse complications (yes, no).

No time frame was specified for OMT/benzodiazepine intrave-

nous misuse, except for the question on the temporal pattern of

misuse in relation to access to the admission unit.

A preliminary version of the questionnaire was administered

to a beta tester group of patients, who rated each question for eas-

iness to understand and answer to, and modified according to the

suggestions of the respondents.

Questionnaires were distributed to patients by the addiction

unit staff together with a covering letter explaining the aims of the

study and directions on the distribution and collection of data [31].

Patients were asked to complete the questionnaires and return

them in sealed envelopes to ensure they remained closed until

analysis. Patients were reassured that return/non-return would

not impact the treatment and were requested to answer honestly

to the questionnaire [31].

Statistical analysis was carried with the IBM SPSS version 20.0

statistical package. The Pearson’s χ

2

test with Yates’s correction

for continuity was used for categorical variables, while the un-

paired t test and the non-parametrical Mann-Whitney U test

were used for continuous ones. Logistic regression model analy-

sis was used to explore the association with misuse (dependent

variable: yes, no), repeated misuse (dependent variable: single

misuse, repeated misuse), and admission to the ER because of

misuse complications (dependent variable: yes, no), with the re-

sults expressed as ORs and 95% CIs. The goodness of fit of the

logistic regression model was assessed using the Hosmer and

Lemeshow test [32]. p < 0.05 (2-tailed) was taken as the signifi-

cance threshold for all the tests.

Results

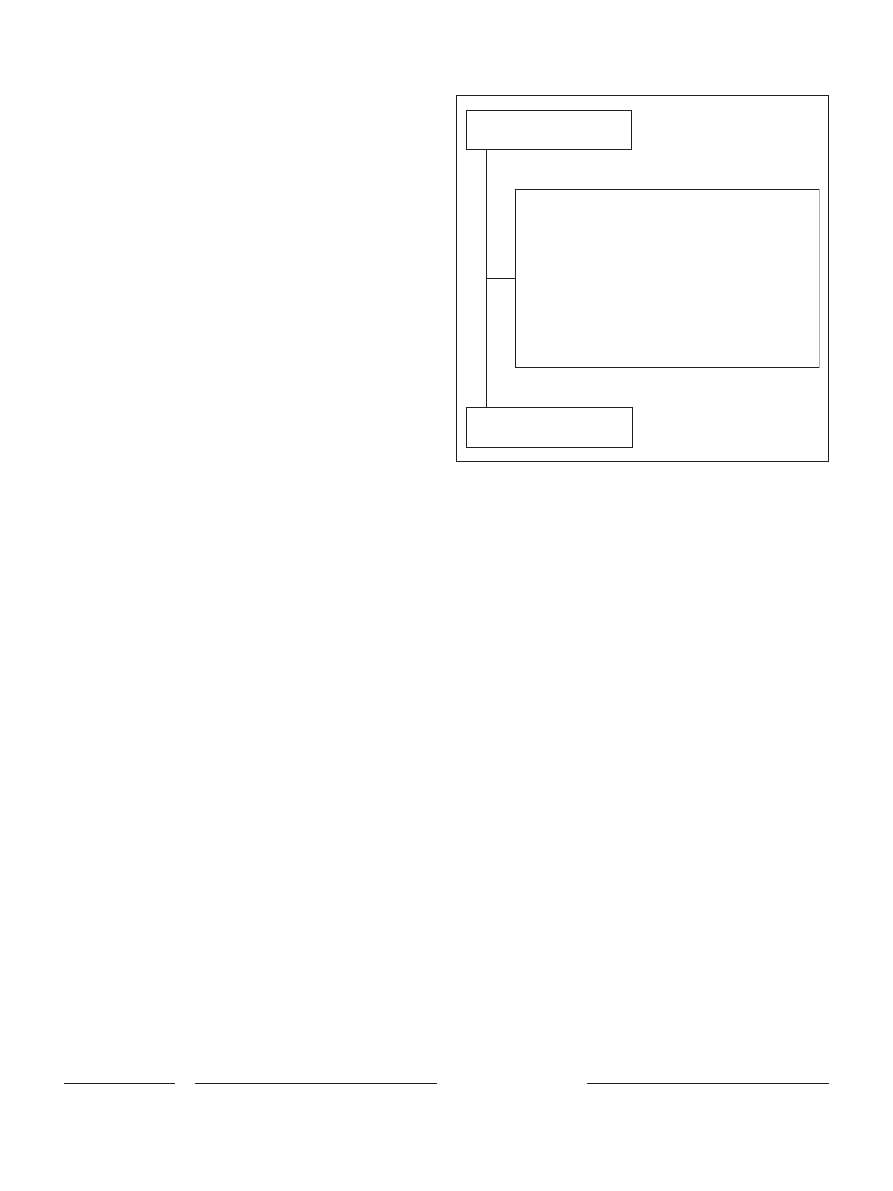

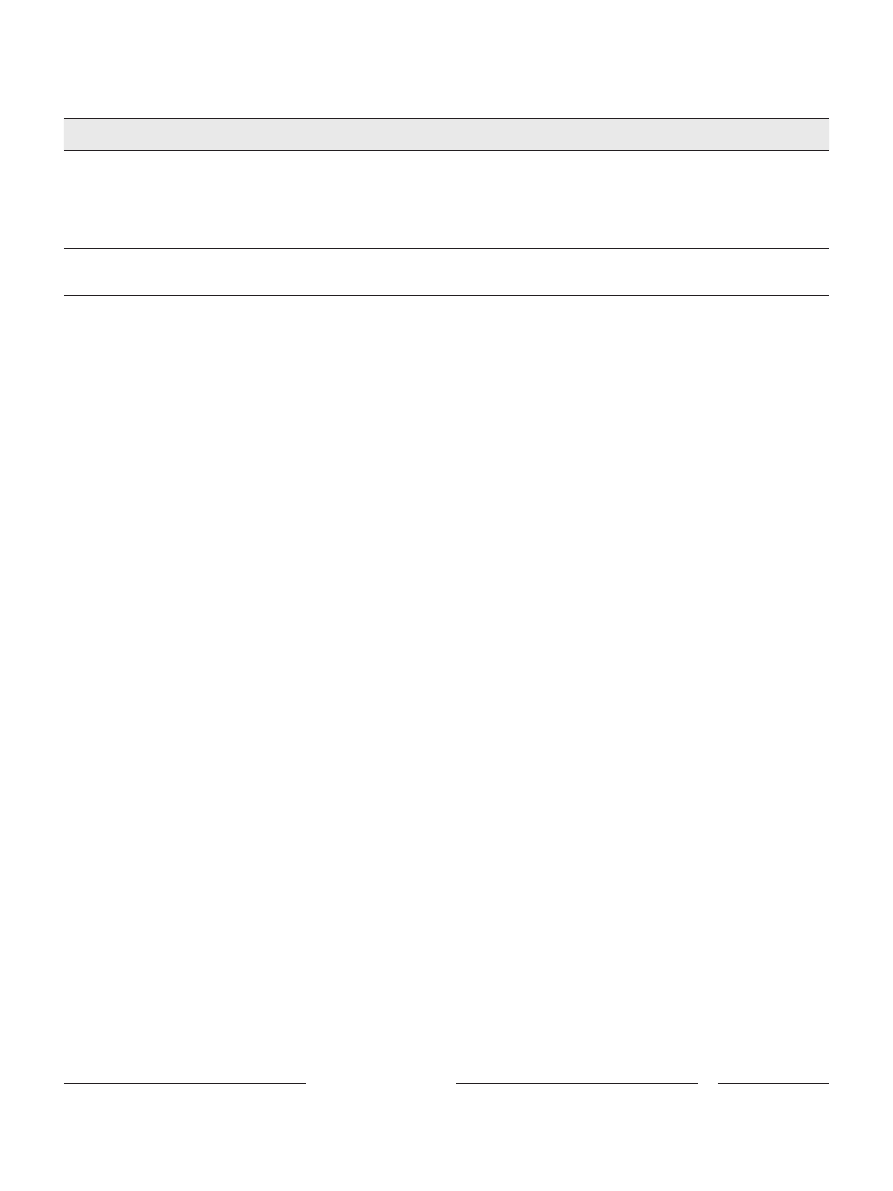

According to inclusion/exclusion criteria, 2,585

patients (2,079 males, 506 females; male/female ratio =

4.1) were included in the study (Fig. 1) and their data

analysed.

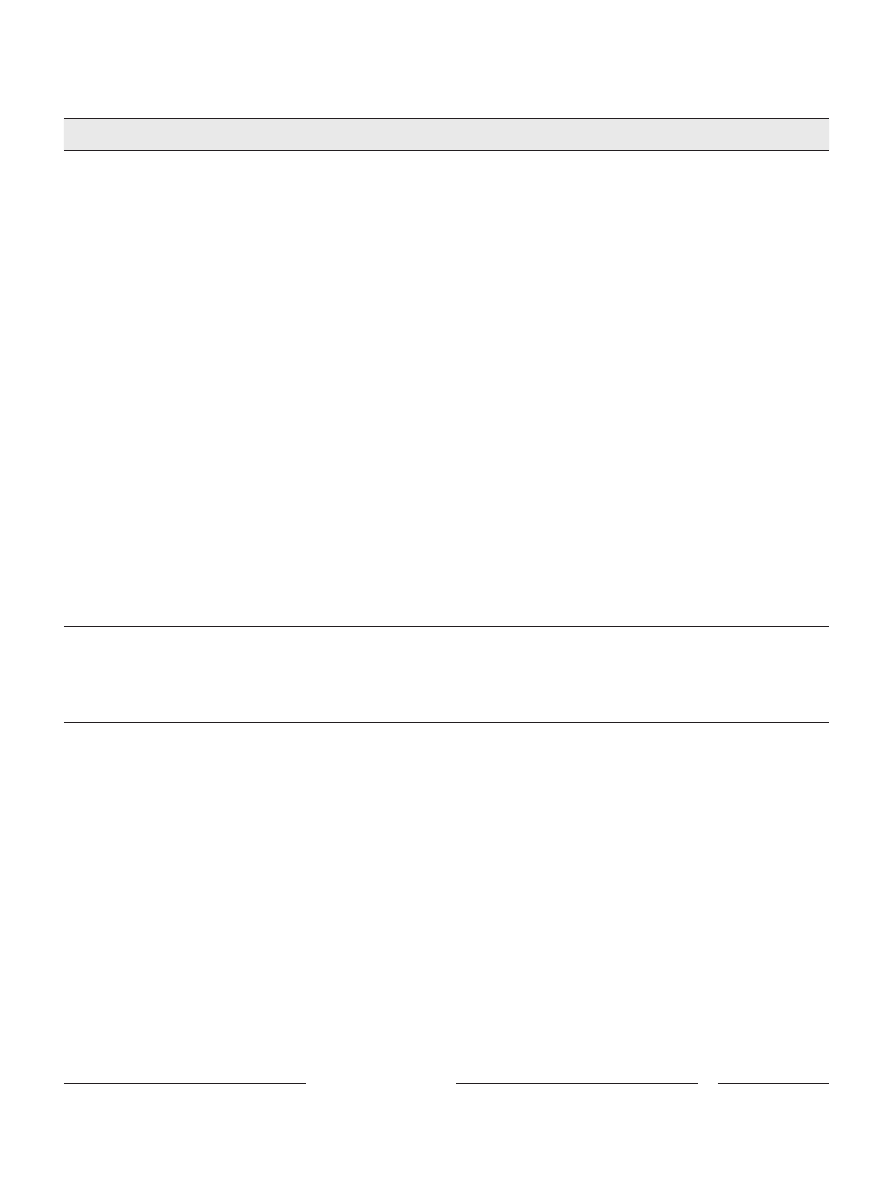

All the demographic characteristics of the patients

(age class, employment, family status) significantly dif-

fered according to gender (Table 1).

Among clinical variables, the type of previous opioid

abuse and OMT type significantly differed, while OMT

dosage was not significantly different according to gender

(Table 1). MET dosage was not significantly different

when comparing low concentration (MET 0.1%) to high

concentration (MET 0.5%) formulation, either in the

whole sample or according to gender (Table 1). BUP dos-

age was significantly higher when comparing BUP to

BUP-NLX formulation in the whole population (Mann-

Whitney U test: p = 0.006) and in males (p = 0.006), but

not in females (ns).

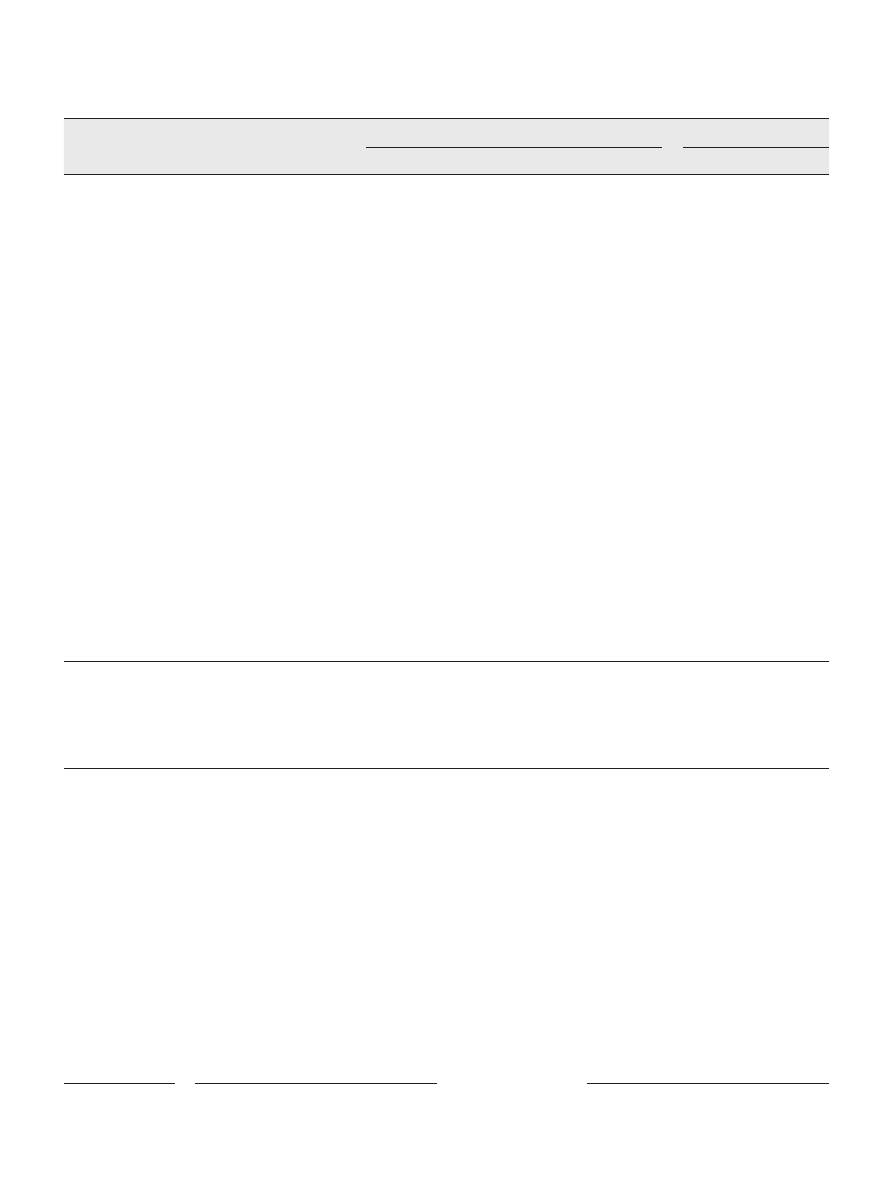

In the whole population, misuse of current OMT was

significantly more frequent for MET 0.5% (29%) than

MET 0.1% formulation (25%, p = 0.035), the rate of re-

peated misuse of current OMT was significantly higher

for BUP-NLX (once: 15%, 2–20 times: 35%, >

20 times:

50%) than BUP formulation (37, 26, and 37%; p = 0.008),

Assessed for eligibility

(n = 3,620)

Excluded (n = 1,035)

No urinalysis data (n = 14)

Opioid maintenance treatment <6 months (n = 105)

Unwilling or no time to participate in the study (n = 652)

Severe liver dysfunction (n = 41)

Severe renal dysfunction (n = 10)

Organ failure or severe medical disorders (n = 16)

Psychosis (n = 22)

Cognitive impairment (n = 18)

Incomplete questionnaire or missing data (n = 127)

More than 1 reason (n = 30)

Eligible and included

(n = 2,585)

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study and reasons for patients’ exclusion.

Downloaded by:

Access provided by the University of Michigan Library

141.216.78.40 - 1/10/2019 11:34:42 AM

Misuse in Patients Under OMT

13

Eur Addict Res 2019;25:10–19

DOI: 10.1159/000496112

the temporal pattern of OMT misuse in relation to the

addiction unit access was significantly different across

OMT types (p = 0.032), and admission to the ER because

of misuse complications was significantly more frequent

for MET 0.5% (38%) than MET 0.1% formulation (30%,

p = 0.001; Table 2).

In men, the rate of repeated misuse of current OMT

was significantly higher for BUP-NLX (once: 15%, 2–20

times: 38%, >

20 times: 47%) than BUP formulation (34,

26, and 40%; p = 0.027), the main reason for current OMT

misuse was significantly different when comparing BUP

(reward/euphoria: 29%, reduce withdrawal symptoms:

58%, enhance drug effects: 13%) to BUP-NLX (31, 41,

and 28%; p = 0.042), the temporal pattern of OMT mis-

use in relation to the addiction unit access (overall: p =

0.018, MET 0.1 vs. MET 0.5%: p = 0.026; BUP vs. BUP-

NLX: p = 0.035) significantly differed, and admission to

the ER because of misuse complications was significant-

ly more frequent for MET 0.5% (38%) than MET 0.1%

formulation (29%; p < 0.001; online suppl. Table 1;

for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/

doi/10.1159/000496112).

In women, the misuse of current OMT was significant-

ly more frequent for MET 0.5% (29%) than MET 0.1%

formulation (18%; p = 0.019; online suppl. Table 2).

Distribution of the patients according to intravenous

OMT vs. benzodiazepine misuse indicated that the ma-

jority of them did not misuse any of the 2 drug classes

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients

Overall

†

(n = 2,585)

Males

†

(n = 2,079)

Females

†

(n = 506)

p value

‡

Age class, years, n (%)

<0.001

<20

33 (1)

15 (1)

18 (4)

20–29

577 (23)

445 (21)

132 (26)

30–39

756 (29)

604 (29)

152 (30)

40–49

879 (34)

722 (35)

157 (31)

≥50

340 (13)

293 (14)

47 (9)

Employment, n (%)

0.005

Fully employed

1,068 (41)

891 (43)

177 (35)

Temporarily employed

535 (21)

421 (20)

114 (23)

Unemployed

982 (38)

767 (37)

215 (42)

Family status, n (%)

<0.001

Living with parents

1,285 (50)

1,068 (51)

17 (43)

Single

606 (23)

517 (25)

89 (18)

Married/engaged

611 (24)

421 (20)

190 (37)

Homeless

83 (3)

73 (4)

10 (2)

Type of previous opioid abuse, n (%)

0.003

Smoked

484 (19)

364 (17)

120 (24)

Snorted

488 (19)

407 (20)

81 (16)

Injected

1,613 (62)

1,308 (63)

305 (60)

OMT type, n (%)

0.014

MET 0.1%

590 (23)

462 (22)

128 (25)

MET 0.5%

1,356 (53)

1,075 (52)

281 (56)

BUP

400 (15)

341 (16)

59 (12)

BUP-NLX

239 (9)

201 (10)

38 (7)

OMT dosage, mg

MET 0.1%

51.0±52.7

51.6±54.4

48.6±46.0

ns

MET 0.5%

50.1±45.0

49.8±41.7

51.2±55.8

ns

BUP

10.6±11.8

*

10.6±12.1

*

10.3±9.9

ns

BUP-NLX

8.1±9.8

8.0±10.4

8.4±5.9

ns

†

Percentage of column.

‡

p value for comparison between males and females (Pearson’s χ

2

test for categorical variables, unpaired t test or Mann-Whitney U

test for continuous ones).

* Significant BUP versus BUP-NLX comparison (Mann-Whitney U test).

ns, non significant; BUP, buprenorphine; MET, methadone; NLX, naloxone; OMT, opioid maintenance treatment.

Downloaded by:

Access provided by the University of Michigan Library

141.216.78.40 - 1/10/2019 11:34:42 AM

Lugoboni et al.

Eur Addict Res 2019;25:10–19

14

DOI: 10.1159/000496112

(58%), while the remaining population was divided into

3 groups of similar size, that is, those misusing OMT

(13%), benzodiazepine (15%) and both (14%; p < 0.0001;

Table 3).

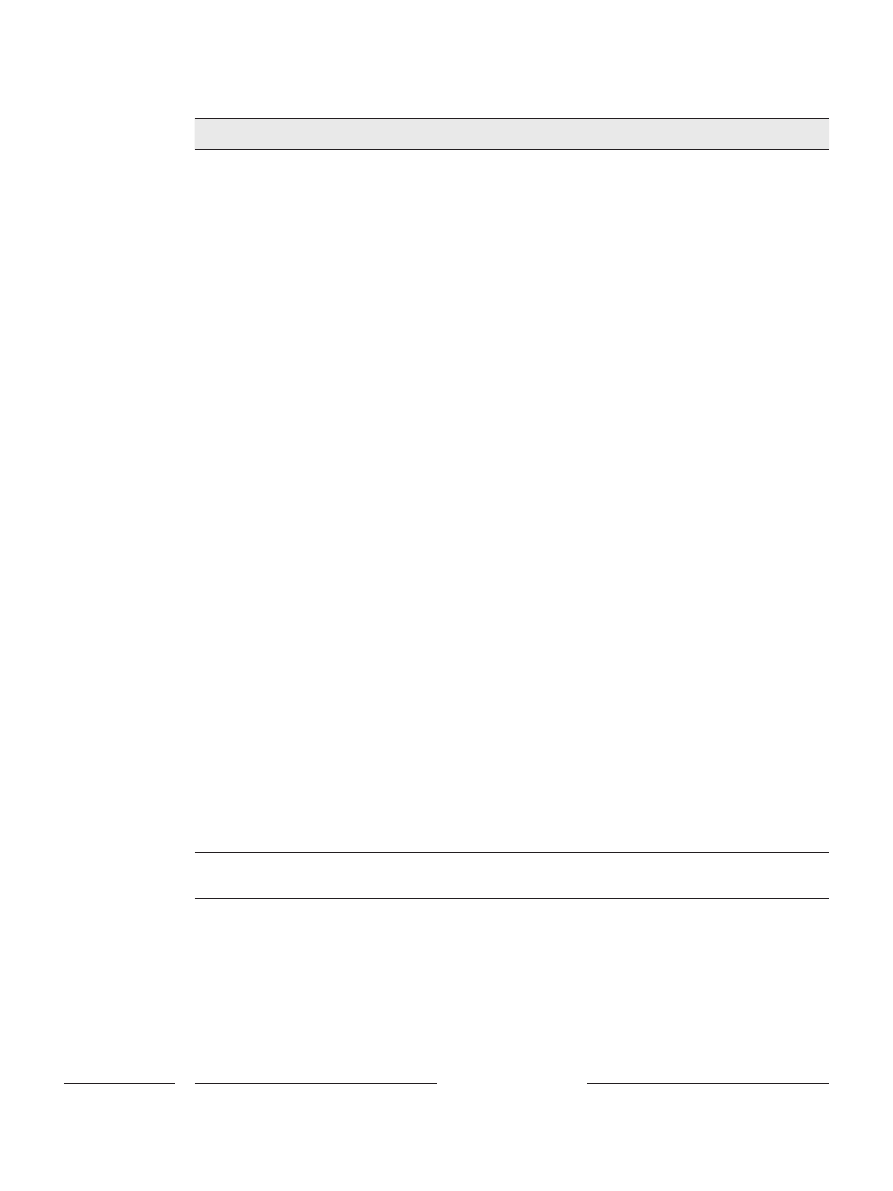

The multivariate logistic regression model showed

that gender, age class, type of previous opioid abuse,

and intravenous benzodiazepine misuse were signifi-

cantly associated with OMT misuse (Table 4), while

the other covariates (employment, family status, OMT

type, daily oral morphine milligram equivalent dos-

age, pattern of benzodiazepine misuse) were not sig-

nificant.

According to the multivariate logistic regression mod-

el, the experience of OMT misuse, and intravenous ben-

zodiazepine misuse were the only variables significantly

associated with repeated OMT misuse (Table 4), while the

other covariates (gender, age class, employment, family

status, type of previous opioid abuse, OMT type, daily

oral morphine milligram equivalent dosage, main reason

for OMT misuse, temporal pattern of benzodiazepine

misuse) were not significant.

The multivariate logistic regression model showed

gender, employment, type of previous opioid abuse and

intravenous benzodiazepine misuse to be significantly as-

Table 2.

Characteristics of intravenous misuse in the whole population (n = 2,585)

OMT type, n (%)

p value

MET 0.1%

†

MET 0.5%

†

BUP

†

BUP-NLX

†

Overall

‡

MET

§

BUP

¶

Misuse of current OMT (n = 2,585)

ns

0.035

ns

Yes (n = 718, 28%)

146 (25)

399 (29)

101 (25)

72 (30)

No (n = 1,867, 72%)

444 (75)

957 (71)

299 (75)

167 (70)

Repeated misuse rate for current OMT (n = 718)

0.035

ns

0.008

Once (n = 206, 29%)

49 (33)

109 (27)

37 (37)

11 (15)

2–20 Times (n = 182, 25%)

33 (23)

98 (25)

26 (26)

25 (35)

>20 Times (n = 330, 46%)

64 (44)

192 (48)

38 (37)

36 (50)

Main reason for current OMT misuse (n = 718)

ns

ns

ns

Reward/euphoria (n = 204, 28%)

38 (26)

115 (29)

28 (28)

23 (32)

Reduce withdrawal symptoms (n = 380, 53%)

85 (58)

206 (52)

58 (57)

31 (43)

Enhance drug effect (n = 134, 19%)

23 (16)

78 (19)

15 (15)

18 (25)

Experience of current OMT misuse (n = 718)

ns

ns

ns

Positive (n = 320, 45%)

70 (48)

174 (44)

41 (42)

35 (49)

Negative (n = 398, 55%)

76 (52)

225 (56)

60 (58)

37 (51)

Temporal pattern of OMT misuse (n = 718)

0.032

ns

ns

Before access to the AU (n = 208, 29%)

55 (37)

109 (27)

27 (27)

17 (24)

After access to the AU (n = 321, 45%)

58 (40)

174 (44)

56 (55)

33 (46)

Both (n = 189, 26%)

33 (23)

116 (29)

18 (18)

22 (30)

Concurrent BZD misuse (n = 2,585)

ns

ns

ns

Never (n = 1,831, 71%)

418 (71)

936 (69)

299 (75)

178 (74)

Once (n = 238, 9%)

54 (9)

121 (9)

40 (10)

23 (10)

2–20 times (n = 236, 9%)

60 (10)

133 (10)

23 (6)

20 (8)

>20 times (n = 280, 11%)

58 (10)

166 (12)

38 (9)

18 (8)

Temporal pattern of BZD misuse (n = 754)

Before access to the AU (n = 374, 50%)

90 (52)

201 (48)

54 (53)

29 (48)

ns

ns

ns

After access to the AU (n = 177, 23%)

43 (25)

96 (23)

22 (22)

16 (26)

Both (n = 203, 27%)

39 (23)

123 (29)

25 (25)

16 (26)

ER admission because of misuse (n = 2,585)

0.001

0.001

ns

Yes (n = 887, 34%)

178 (30)

513 (38)

120 (30)

76 (32)

No (n = 1,698, 66%)

412 (70)

843 (62)

280 (70)

163 (68)

†

Percentage of column.

‡

p value for the comparison between the 4 OMT types (Pearson’s χ

2

test).

§

p value for the comparison between the 2 MET formulations (MET 0.1 versus MET 0.5%, Pearson’s χ

2

test).

¶

p value for the comparison between the 2 BUP formulations (BUP vs. BUP-NLX, Pearson’s χ

2

test).

ns, non significant; AU, addiction unit; BZD, benzodiazepine; BUP, buprenorphine; ER, emergency room; MET, methadone; NLX, nalox-

one; OMT, opioid maintenance treatment.

Downloaded by:

Access provided by the University of Michigan Library

141.216.78.40 - 1/10/2019 11:34:42 AM

Misuse in Patients Under OMT

15

Eur Addict Res 2019;25:10–19

DOI: 10.1159/000496112

sociated with admission to the ER because of misuse com-

plications (Table 4), while the other covariates (age class,

family status, OMT type, daily oral morphine milligram

equivalent dosage, rate of repeated OMT misuse, main

reason for OMT misuse, experience of OMT misuse, tem-

poral pattern of OMT and benzodiazepine misuse) were

not significant.

Discussion

The present multicentre study, which is to the best of

our knowledge, one of the largest one on OMT misuse,

yielded the following main findings: (a) OMT misuse was

found in 28% of patients with no difference between

OMT types, and was associated with gender, age, type of

previous opioid abuse and intravenous benzodiazepine

misuse; (b) repeated OMT misuse was reported by 20%

(i.e., 71% of misusers) of patients, and was associated with

positive OMT misuse experience and intravenous benzo-

diazepine misuse; (c) 34% of patients reported admission

to the ER because of misuse complications, this outcome

being associated with gender, employment, type of previ-

ous opioid abuse and intravenous benzodiazepine mis-

use.

Baseline demographic (age, employment, family sta-

tus) and clinical variables (type of previous opioid

abuse, OMT type) significantly differed according to

gender, indicating that male and female cohorts did not

overlap. In keeping with previous reports [28, 31, 33],

men were largely overrepresented in our sample, and

this gender unbalance might have biased the findings

for the whole population and their generalization to

women. Univariate analyses for OMT types were per-

formed in the whole sample and separately according

to gender, and it suggested some differences between

men and women. They included (a) OMT misuse was

significantly more frequent for MET 0.5% vs. MET

0.1% in women; (b) repeated OMT misuse rate was sig-

nificantly higher for BUP-NLX vs. BUP in men; (c) ad-

mission to the ER because of misuse complications was

significantly higher for MET 0.5% vs. MET 0.1% in

men; (d) the main reason for misuse significantly dif-

fered when comparing BUP-NLX vs. BUP in men.

However, these findings should be interpreted with

caution because of the univariate model, and the differ-

ent statistical power for male and female populations,

the former being more than 4 times larger than the lat-

ter. Multivariate analyses documented gender-related

differences, in that female sex appeared to be signifi-

cantly and inversely associated with OMT misuse (OR

0.74) and admission to the ER because of misuse com-

plications (OR 0.59).

The main finding of this study was that, in keeping

with previous reports [1, 9, 11, 14, 18, 19, 31, 34], nearly

one third of patients under OMT reported misuse, this

outcome not being influenced by OMT type or dosage in

the multivariate model. In accordance with previous

studies [35, 36], age class was significantly and inversely

associated with misuse, suggesting that younger patients

under OMT should be more strictly monitored. We

could not document any significant association between

other demographic variables, such as family and employ-

ment status, and misuse, thus not confirming previous

reports [11, 31, 34].

Our data contradict the notion that BUP-NLX may re-

duce diversion and misuse [19, 21] but are in keeping with

post-marketing reports of non-significant difference be-

tween BUP-NLX and BUP or MET injection rate in OMT

patients [22, 23], and experimental evidence that BUP and

BUP-NLX are similarly reinforcing in recently detoxified

heroin abusers [37]. Opioid pharmacology may explain this

apparently paradoxical finding. BUP has a higher binding

affinity for the mu opioid receptor and a longer effect than

Table 3.

Distribution of the patients according to intravenous OMT and BZD misuse

Overall

†

(n = 2,585)

Males

†

(n = 2,079)

Females

†

(n = 506)

No misuse, n (%)

1,489 (58)

1,187 (57)

302 (60)

Misuse of OMT only, n (%)

342 (13)

282 (14)

60 (12)

Misuse of BZD only, n (%)

378 (15)

299 (14)

79 (15)

Concurrent OMT and BZD misuse, n (%)

376 (14)

311 (15)

65 (13)

p

value (Pearson’s χ

2

test, 2 × 2 table)

<0.0001

<0.0001

<0.0001

†

Percentage of column.

BZD, benzodiazepine; OMT, opioid maintenance treatment.

Downloaded by:

Access provided by the University of Michigan Library

141.216.78.40 - 1/10/2019 11:34:42 AM

Lugoboni et al.

Eur Addict Res 2019;25:10–19

16

DOI: 10.1159/000496112

NLX [38]. NLX dose in the BUP-NLX formulation might

not be sufficient to antagonize BUP effect on the mu recep-

tor [28] and/or its antagonist effect might be too short. This

view is supported by an experimental study showing that

intranasal administration of BUP-NLX causes modest but

transient unpleasant effect related to opioid withdrawal,

followed by delayed agonist effect of BUP [38].

One fifth of our patients, and nearly 3 quarters of mis-

users, reported repeated OMT misuse, which was signifi-

cantly associated with positive misuse experience in the

Table 4.

Results of the multivariate logistic regression model analysis

Significant covariates

OR (95% CI)

p value

Dependent variable 1: OMT misuse

Gender

Male

1

Female

0.74 (0.57–0.96)

0.021

Age, years

<30

1

30–39

0.44 (0.34–0.58)

<0.001

40–49

0.26 (0.20–0.35)

<0.001

≥50

0.17 (0.12–0.24)

<0.001

Type of previous opioid abuse

Smoked

1

Snorted

1.54 (1.02–2.32)

0.04

Injected

4.95 (3.52–6.96)

<0.001

Intravenous BZD misuse

Never

1

Once

3.32 (2.45–4.52)

<0.001

2–20 times

3.56 (2.61–4.84)

<0.001

>20 times

4.03 (3.02–5.38)

<0.001

Dependent variable 2: repeated OMT misuse

Experience of OMT misuse

Negative

1

Positive

3.13 (2.17–4.52)

<0.001

Intravenous BZD misuse

Never

1

Once

1.75 (1.06–2.89)

0.028

2–20 times

1.81 (1.10–2.98)

0.02

>20 times

2.02 (1.25–3.28)

0.004

Dependent variable 3: admission to the ER because

of misuse complications

Gender

Male

1

Female

0.59 (0.36–0.96)

0.035

Employment

Fully employed

1

Temporarily employed

1.74 (1.05–2.86)

0.031

Unemployed

2.49 (1.63–3.82)

<0.001

Type of previous opioid abuse

Smoked

1

Snorted

ns

Injected

3.89 (1.78–8.47)

0.001

Intravenous BZD misuse

Never

1

Once

ns

2–20 times

2.71 (1.61–4.57)

<0.001

>20 times

2.97 (1.80–4.87)

<0.001

Here only covariates that turned out to be significant in the multivariate logistic regression model analysis are reported.

ns, non significant; BZD, benzodiazepine; ER, emergency room; OMT, opioid maintenance treatment.

Downloaded by:

Access provided by the University of Michigan Library

141.216.78.40 - 1/10/2019 11:34:42 AM

Misuse in Patients Under OMT

17

Eur Addict Res 2019;25:10–19

DOI: 10.1159/000496112

multivariate analysis. The finding that positive effect of

misuse was similar between MET, BUP and BUP-NLX

might explain why OMT type did not influence repeated

misuse in the multivariate model, and is in keeping with a

previous report of misuse experience influencing repeat-

ed misuse [33]. Male patients injected BUP-NLX more

frequently than BUP to enhance drug effects than to re-

duce withdrawal symptoms, suggesting that BUP-NLX

might reduce misuse in patients who are more sensitive to

the negative effect of withdrawal, while it may worsen this

phenomenon in those who prefer a long-lasting drug ef-

fect. Future studies should explore whether these differ-

ences across patients, or their personality profiles, can

help predicting misuse to different OMT formulations.

Another variable that may have influenced misuse is

the ease of injecting, which is higher for BUP and BUP-

NLX than MET, the latter being more viscous and requir-

ing larger gauge needles [39].

One third of our patients reported admission to the ER

during their lifetime because of misuse complications.

This number is higher than that of patients reporting mis-

use to current OMT because the answer encompassed ad-

missions due to any OMT, either current or previous,

and/or other drugs, including benzodiazepine. Reasons

for ER admission were based on self-report and could not

be cross-checked with ER/hospital databases because the

questionnaires were anonymous. Employment was sig-

nificantly associated to ER admissions, in that temporar-

ily employed and unemployed patients had ORs of 1.74

and 2.49, respectively, in comparison to fully employed

ones. This finding underscores the importance of social

factors and the role of psychosocial support to improve

misuse outcomes [31].

In accordance with previous reports [1], previous opi-

oid injection was associated with a higher likelihood of

misuse (OR 4.95) and ER admission (OR 3.89) in com-

parison to smoking and snorting. Injection provides fast-

er drug delivery and onset compared to the oral route,

and once people start injecting opioids, they often engage

in risky injection practices [40]. This finding suggests

more caution when delivering OMT to patients who pre-

viously injected opioids.

Concurrent intravenous benzodiazepine misuse was

reported by 29% of patients, half of whom misused also

OMT. Benzodiazepine misuse and its frequency were

associated with OMT misuse, repeated misuse and ER

admission, suggesting that it represents the variable

more significantly correlated to OMT misuse outcomes

in our study. This finding is in keeping with previous

studies and suggest considering overall drug misuse in-

stead of focusing on OMT misuse only [31], and paying

attention to concurrent anxiety disorders or sleep dis-

orders that may require benzodiazepine prescription

[24, 41].

The main strengths of this study are the large sample size

and the multicentre design that allowed sampling a large

population of Italian patients under OMT. Another

strength is the high return rate (78%), in that only 18% of

patients refused to participate to the study, and 4% of the

questionnaires were incomplete and thus not analysed.

These figures are higher than those from a similar report on

Finnish OMT patients, where the return rate was 60% [31].

The main limitation of the present study is that OMT

dosage was below the recommended maintenance dose

range. The average daily dose of MET, either high or low

concentration, was around 50 mg, while international ap-

plied guidelines, such as the NICE guidance, suggest the

usual maintenance dose range of 60–120 mg daily [42].

Similarly, the average BUP daily dose was 11 mg and that

of BUP-NLX was 8 mg, both of them below the usual

maintenance daily dose range of 12–24 mg [42]. The low

OMT dosage might be the main reason for intravenous

misuse in our patients and a potential bias in the interpre-

tation of the data, since previous studies reported an as-

sociation between sub-optimal OMT doses and higher

misuse to reduce withdrawal symptoms [11, 20, 31, 34].

However, the daily oral morphine milligram equivalent

dosage was not significant in any of the 3 multivariate

analyses, possibly arguing against the importance of this

factor.

We may speculate that the low OMT dosage in our

sample might be related to the finding that 45% of the pa-

tients started misuse after accessing the addiction unit. In

Italy, outpatients receive OMT directly and with no cost

from the National Health Service addiction units, while

other sources, such as prescription from general practi-

tioners and private addiction specialists, are nearly ab-

sent. The large number of addiction units involved in this

study is representative of standard care in Italy, and thus

we recommend that caution to OMT under-dosage be

exercised in order to avoid intravenous misuse. Male pa-

tients experienced misuse more frequently for MET 0.5%

(45%) than MET 0.1% (39%) and for BUP (53%) than

BUP-NLX (43%). Since OMT misuse is known to be di-

rectly related to drug availability [43], this finding under-

scores the importance of strict monitoring of misuse in

the addiction units, especially for high concentration

MET and BUP.

Another limitation is that data was self-reported by pa-

tients, who, despite being assured of the confidentiality of

Downloaded by:

Access provided by the University of Michigan Library

141.216.78.40 - 1/10/2019 11:34:42 AM

Lugoboni et al.

Eur Addict Res 2019;25:10–19

18

DOI: 10.1159/000496112

the survey, might have under-reported some sensitive

pieces of information because of shame or fear of negative

judgement [31]. However, studies based on self-report

are considered sufficiently reliable and valid in the field

of addiction medicine [44], and there was no other way

to collect information on misuse that is usually not re-

corded in the patient’s clinical files. Other limitations are

that respondents might have been the more motivated

and compliant patients, and the absence of data on psy-

chiatric comorbidity.

In conclusion, we offered new information on OMT

misuse in a large group of Italian patients. Our data indi-

cate that BUP-NLX misuse is not different from that of

BUP or MET. These results may be helpful for better tai-

loring OMT to reduce misuse and its complications. For

example, particular care should be paid to men and pa-

tients who previously injected opioids or with intrave-

nous benzodiazepine misuse, in that they are at higher

risk of misuse and worse outcome with OMT. They also

indicate that choosing the more expansive BUP-NLX

over MET will likely not lead to the expected reduction of

the risk of injection misuse of the OMT. Addiction unit

physicians and medical personnel should better focus on

patient’s features that are associated with higher likeli-

hood of misuse.

Acknowledgements

None.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Hel-

sinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Verona Uni-

versity Hospital. All patients gave written informed consent for

participation to the study. No benefit was provided for participa-

tion in the study that was voluntary and confidential.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

None.

Authors Contributions

F.L.: designed the study, gathered the data, developed the data-

base, interpreted the data, drafted and revised the manuscript. L.Z.:

designed the study, gathered the data, developed the database, in-

terpreted the data and revised the manuscript. M.C.: designed the

study, gathered the data, interpreted the data and revised the man-

uscript. S.T.: designed the study, developed the database, conduct-

ed the statistical analysis, interpreted the data, drafted and revised

the manuscript. All authors read and approved of the final version

of the manuscript.

Appendix

Members of the Gruppo InterSERT di Collaborazione Scientifica

(GICS) in alphabetical order: L. Andreoli, V. Balestra, O. Betti, C.

Biasin, C. Bossi, A. Bottazzo, A. Bove, R. Bressan, B. Buson, E. Cac-

camo, V. Calderan, S. Cancian, F. Cantachin, D. Cantiero, G. Can-

zian, D. Cargnelutti, L. Carraro, D. Casalboni, R. Casari, G. Certa, P.

Civitelli, M. Codogno, T. Cozzi, D. Danieli, L. De Cecco, A. Dei Ros-

si, E. Dell’Antonio, R. Del Zotto, M. Faccini, M. Fadelli, E. Favero, A.

Fiore, B. Fona, A. Franceschini, E. Gaiga, M. Gardiolo, N. Gentile, G.

Gerra, N. Ghezzo, M. Giacomin, L. Giannessi, G. Giuli, G. Guescini,

B. Hanife, S. Laus, G. Mantovani, A. Manzoni, S. Marescatto, M.

Mazzo, D. Meneghello, C. Meneguzzi, D. E. Milan, D. Mussi, M.

Monfredini, E. Nardi, F. Nardozi, A. Natoli, M. Pagnin, P. Pagnin, A.

Pani, V. Pavani, P. Pellachin, F. Peroni, V. Peroni, T. Pezzotti, M. C.

Pieri, L. Povellato, D. Prosa, B. Pupulin, G. Raschi, C. Resentera, M.

Residori, P. Righetti, M. Ripoli, P. Riscica, V. Rizzetto, M. Rotini, A.

Rovea, R. Sabbioni, D. Saccon, E. Santo, E. Savoini, M. Scarzella, P.

Simonetto, C. Smacchia, M. Stellato, C. Stimolo, L. Suardi, M. Trev-

isan, G. Urzino, A. Vaiana, A. Valent, M. Vidal, A. Zamai, A. Zanchet-

tin, V. Zavan, G. Zecchinato, M. Zerman, G. Zinfollino.

References

1 Humeniuk R, Ali R, McGregor C, Darke S:

Prevalence and correlates of intravenous

methadone syrup administration in Adelaide,

Australia. Addiction 2003;

98:

413–418.

2 Nordmann S, Frauger E, Pauly V, Orléans V,

Pradel V, Mallaret M, et al: Misuse of bu-

prenorphine maintenance treatment since in-

troduction of its generic forms: OPPIDUM

survey. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;

21:

184–190.

3 Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M: Bu-

prenorphine maintenance versus placebo or

methadone maintenance for opioid depen-

dence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2014:CD002207.

4 Bell J: Pharmacological maintenance treat-

ments of opiate addiction. Br J Clin Pharma-

col 2014;

77:

253–263.

5 Casati A, Sedefov R, Pfeiffer-Gerschel T: Mis-

use of medicines in the European Union: a

systematic review of the literature. Eur Addict

Res 2012;

18:

228–245.

6 Dale O, Hoffer C, Sheffels P, Kharasch ED:

Disposition of nasal, intravenous, and oral

methadone in healthy volunteers. Clin Phar-

macol Ther 2002;

72:

536–545.

7 Robinson GM, Kemp R, Lee C, Cranston D:

Patients in methadone maintenance treatment

who inject methadone syrup: a preliminary

study. Drug Alcohol Rev 2000;

19:

447–450.

Downloaded by:

Access provided by the University of Michigan Library

141.216.78.40 - 1/10/2019 11:34:42 AM

Misuse in Patients Under OMT

19

Eur Addict Res 2019;25:10–19

DOI: 10.1159/000496112

8 Darke S: Self-report among injecting drug us-

ers: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend 1998;

51:

253–263.

9 Chevalley AE, Besson J, Croquette-Krokar M,

Davidson C, Dubois JA, Uehlinger C, et al:

Prevalence of methadone injection in three

Swiss cities. Presse Med 2005;

34:

776–780.

10 Rosenblum A, Parrino M, Schnoll SH, Fong

C, Maxwell C, Cleland CM, et al: Prescription

opioid abuse among enrollees into metha-

done maintenance treatment. Drug Alcohol

Depend 2007;

90:

64–71.

11 Roux P, Villes V, Bry D, Spire B, Feroni I,

Marcellin F, et al: Buprenorphine sniffing as a

response to inadequate care in substituted pa-

tients: results from the Subazur survey in

south-eastern France. Addict Behav 2008;

33:

1625–1629.

12 Winstock AR, Lea T, Sheridan J: Prevalence of

diversion and injection of methadone and bu-

prenorphine among clients receiving opioid

treatment at community pharmacies in New

South Wales, Australia. Int J Drug Policy

2008;

19:

450–458.

13 Maremmani I, Pacini M, Pani PP, Popovic D,

Romano A, Maremmani AG, et al: Use of

street methadone in Italian heroin addicts

presenting for opioid agonist treatment. J Ad-

dict Dis 2009;

28:

382–388.

14 Judson G, Bird R, O’Connor P, Bevin T, Loan

R, Schroder M, et al: Drug injecting in pa-

tients in New Zealand methadone mainte-

nance treatment programs: an anonymous

survey. Drug Alcohol Rev 2010;

29:

41–46.

15 Bouquié R, Wainstein L, Pilet P, Mussini JM,

Deslandes G, Clouet J, et al: Crushed and in-

jected buprenorphine tablets: characteristics

of princeps and generic solutions. PLoS One

2014;

9:e113991.

16 Quaglio G, Talamini G, Lechi A, Venturini L,

Lugoboni F, Mezzelani P; et al: Study of 2708

heroin-related deaths in north-eastern Italy

1985–98 to establish the main causes of death.

Addiction 2001;

96:

1127–1137.

17 Weimer MB, Korthuis PT, Behonick GS,

Wunsch MJ: The source of methadone in

overdose deaths in Western Virginia in 2004.

J Addict Med 2011;

5:

188–202.

18 Moratti E, Kashanpour H, Lombardelli T,

Maisto M: Intravenous misuse of buprenor-

phine: characteristics and extent among

patients undergoing drug maintenance

therapy. Clin Drug Investig 2010;

30(suppl

1):

3–11.

19 Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP: Fac-

tors contributing to the rise of buprenorphine

misuse: 2008–2013. Drug Alcohol Depend

2014;

142:

98–104.

20 Comer SD, Sullivan MA, Vosburg SK, Ma-

nubay J, Amass L, Cooper ZD, et al: Abuse

liability of intravenous buprenorphine/nalox-

one and buprenorphine alone in buprenor-

phine-maintained intravenous heroin abus-

ers. Addiction 2010;

105:

709–718.

21 Soyka M: New developments in the manage-

ment of opioid dependence: focus on sublin-

gual buprenorphine-naloxone. Subst Abuse

Rehabil 2015;

6:

1–14.

22 Bruce RD, Govindasamy S, Sylla L, Kamarul-

zaman A, Altice F: Lack of reduction in bu-

prenorphine injection after introduction of

co-formulated buprenorphine/naloxone to

the Malaysian market. Am J Drug Alcohol

Abuse 2009;

35:

68–72.

23 Larance B, Lintzeris N, Ali R, Dietze P, Mat-

tick R, Jenkinson R, et al: The diversion and

injection of a buprenorphine-naloxone solu-

ble film formulation. Drug Alcohol Depend

2014;

136:

21–27.

24 Chen KW, Berger CC, Forde DP, D’Adamo C,

Weintraub E, Gandhi D: Benzodiazepine use

and misuse among patients in a methadone

program. BMC Psychiatry 2011;

11:

90.

25 Pauly V, Pradel V, Pourcel L, Nordmann S,

Frauger E, Lapeyre-Mestre M, et al: Estimated

magnitude of diversion and abuse of opioids

relative to benzodiazepines in France. Drug

Alcohol Depend 2012;

126:

13–20.

26 Herbert A, Gilbert R, Cottrell D, Li L: Causes

of death up to 10 years after admissions to

hospitals for self-inflicted, drug-related or al-

cohol-related, or violent injury during adoles-

cence: a retrospective, nationwide, cohort

study. Lancet 2017;

390:

577–587.

27 Sun EC, Dixit A, Humphreys K, Darnall BD,

Baker LC, Mackey S: Association between

concurrent use of prescription opioids and

benzodiazepines and overdose: retrospective

analysis. BMJ 2017;

356:j760.

28 Vicknasingam B, Mazlan M, Schottenfeld RS,

Chawarski MC: Injection of buprenorphine

and buprenorphine/naloxone tablets in Ma-

laysia. Drug Alcohol Depend 2010;

111:

44–

49.

29 Nielsen S, Degenhardt L, Hoban B, Gisev N:

Comparing Opioids: A Guide to Estimating

Oral Morphine Equivalents (OME) in Re-

search. Technical Report No. 329. Sydney,

National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre,

University of New South Wales, 2014.

30 Lugoboni F, Zamboni L, Federico A, Tambu-

rin S; Gruppo InterSERT di Collaborazione

Scientifica (GICS): Erectile dysfunction and

quality of life in men receiving methadone or

buprenorphine maintenance treatment. A

cross-sectional multicentre study. PLoS One

2017;

12:e0188994.

31 Launonen E, Wallace I, Kotovirta E, Alho H,

Simojoki K: Factors associated with non-ad-

herence and misuse of opioid maintenance

treatment medications and intoxicating drugs

among Finnish maintenance treatment pa-

tients. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;

162:

227–

235.

32 Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic

Regression (ed 2). New York, Wiley, 2000.

33 Duffy P, Baldwin H: The nature of methadone

diversion in England: a Merseyside case

study. Harm Reduct J 2012;

9:

3.

34 Vidal-Trecan G, Varescon I, Nabet N, Bois-

sonnas A: Intravenous use of prescribed sub-

lingual buprenorphine tablets by drug users

receiving maintenance therapy in France.

Drug Alcohol Depend 2003;

69:

175–181.

35 West NA, Severtson SG, Green JL, Dart RC:

Trends in abuse and misuse of prescription

opioids among older adults. Drug Alcohol

Depend 2015;

149:

117–121.

36 Krause D, Plörer D, Koller G, Martin G, Win-

ter C, Adam R, et al: High concomitant mis-

use of fentanyl in subjects on opioid mainte-

nance treatment. Subst Use Misuse 2017;

52:

639–645.

37 Comer SD, Collins ED: Self-administration of

intravenous buprenorphine and the bu-

prenorphine/naloxone combination by re-

cently detoxified heroin abusers. J Pharmacol

Exp Ther 2002;

303:

695–703.

38 Walsh SL, Nuzzo PA, Babalonis S, Casselton

V, Lofwall MR: Intranasal buprenorphine

alone and in combination with naloxone:

abuse liability and reinforcing efficacy in

physically dependent opioid abusers. Drug

Alcohol Depend 2016;

162:

190–198.

39 Guichard A, Lert F, Calderon C, Gaigi H, Ma-

guet O, Soletti J, et al: Illicit drug use and in-

jection practices among drug users on metha-

done and buprenorphine maintenance treat-

ment in France. Addiction 2003;

98:

1585–1597.

40 Jones CM: Trends and key correlates of pre-

scription opioid injection misuse in the Unit-

ed States. Addict Behav 2018;

78:

145–152.

41 Bouvier BA, Waye KM, Elston B, Hadland SE,

Green TC, Marshall BDL: Prevalence and cor-

relates of benzodiazepine use and misuse

among young adults who use prescription

opioids non-medically. Drug Alcohol De-

pend 2018;

183:

73–77.

42 NICE: Methadone and buprenorphine for the

management of opioid dependence. https://

w w w . n i c e . o r g . u k / g u i d a n c e / T A 1 1 4 /

chapter/1-Guidance (accessed on November

4, 2018).

43 Degenhardt L, Larance BK, Bell JR, Winstock

AR, Lintzeris N, Ali RL, et al: Injection of

medications used in opioid substitution treat-

ment in Australia after the introduction of a

mixed partial agonist-antagonist formula-

tion. Med J Aust 2009;

131:

161–165.

44 Darke S, Topp L, Ross J: The injection of

methadone and benzodiazepines among Syd-

ney injecting drug users 1996–2000: 5-year

monitoring of trends from the illicit drug re-

porting system. Drug Alcohol Rev 2002;

21:

27–32.

Downloaded by:

Access provided by the University of Michigan Library

141.216.78.40 - 1/10/2019 11:34:42 AM

Document Outline

- TabellenTitel

- TabellenFussnote

- TabellenTitel

- StartZeile

- Zwischenlinie

- TabellenFussnote

- TabellenTitel

- TabellenFussnote

- TabellenTitel

- TabellenFussnote

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

10 Metody otrzymywania zwierzat transgenicznychid 10950 ppt

10 dźwigniaid 10541 ppt

wyklad 10 MNE

Kosci, kregoslup 28[1][1][1] 10 06 dla studentow

10 budowa i rozwój OUN

10 Hist BNid 10866 ppt

POKREWIEŃSTWO I INBRED 22 4 10

Prezentacja JMichalska PSP w obliczu zagrozen cywilizacyjn 10 2007

Mat 10 Ceramika

BLS 10

10 0 Reprezentacja Binarna

10 4id 10454 ppt

10 Reprezentacja liczb w systemie komputerowymid 11082 ppt

więcej podobnych podstron