Everyday English for International Nurses

A guide to working in the UK

C3996_00.qxd 26/02/2004 13:42 Page i

For Churchill Livingstone:

Commissioning Editor: Ninette Premdas

Development Editor: Kim Benson

Project Manager: Darren Smith

Design: Erik Bigland

C3996_00.qxd 26/02/2004 13:42 Page ii

Everyday English for

International Nurses

A guide to working in the UK

EDINBURGH

LONDON

NEW YORK

PHILADELPHIA

SAN FRANCISCO

SYDNEY

TORONTO

2004

Joy Parkinson

BA

Author and Lecturer, London, UK

Chris Brooker

BSc, MSc, RGN, SCM, RNT

Author and Lecturer, Norfolk, UK

C3996_00.qxd 26/02/2004 13:42 Page iii

CHURCHILL LIVINGSTONE

An imprint of Elsevier Limited

© 2004, Elsevier Limited. All rights reserved.

First published 2004

The right of Joy Parkinson and Chris Brooker to be identified as

authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without either the

prior permission of the publishers or a licence permitting restricted

copying in the United Kingdom issued by the Copyright Licensing

Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK.

Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier's Health Sciences

Rights Department in Philadelphia, USA: (+1) 215 238 7869,

fax: (+1) 215 238 2239, e-mail: healthpermissions@elsevier.com. You

may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier Science

homepage (http://www.elsevier.com), by selecting ‘Customer Support’

and then ‘Obtaining Permissions’.

ISBN 0 443 07399 6

British Library of Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Note

Medical knowledge is constantly changing. As new information

becomes available, changes in treatment, procedures, equipment and

the use of drugs become necessary. The authors/contributors and the

publishers have taken care to ensure that the information given in this

text is accurate and up to date. However, readers are strongly advised

to confirm that the information, especially with regard to drug usage,

complies with current legislation and standards of practice.

Printed in China

C3996_00.qxd 26/02/2004 13:42 Page iv

Preface

This book is designed to help the large numbers of overseas nurs-

es who have chosen to practise in the UK. The content has been

adapted from the Manual of English for the Overseas Doctor, by

Joy Parkinson. The result is a book with a uniquely nursing focus.

It can be a daunting prospect for anyone to move to another

country to nurse; not only must you become familiar with the

organisation and regulation of nursing, but you need to learn how

English is spoken by people in everyday situations. The language

spoken by clients, patients and their families in the UK is vastly

different from that used overseas. Hence a large part of the book

is concerned with the vocabulary and language used in the

nurse–patient relationship.

The first three chapters provide information about nursing in

the UK, the nursing process, professional organisations and trade

unions, registering as a nurse, adaptation programmes and career

development, and the structure of the National Health Service

and Social Services.

Chapter 4 focuses on documentation and record keeping that

are vital to good practice. This chapter also deals with written

communication in the form of letters and e-mail.

Communication in nursing is covered in Chapter 5. This

includes taking a nursing history and many case-history dialogues.

The case histories are based on the Activities of Living Model of

Nursing and provide examples of dialogue between nurses and

patients or relatives in a wide range of situations.

Chapters 6 to 8 deal with the language of spoken English (col-

loquial English, idioms and phrasal verbs). This material is based

on the book for doctors, but it has been completely updated for

the 21st century.

v

C3996_00.qxd 26/02/2004 13:42 Page v

The last three chapters provide you with more useful informa-

tion – abbreviations used in nursing, useful addresses and web

sources, and units of measurement.

Further reading suggestions and references are included in the

chapters, and a general list of further reading is provided at the

end of the book.

We hope that this new book will be of great help to you during

your nursing career in the UK.

Joy Parkinson and Chris Brooker

London and Norfolk 2004

PREFACE

vi

C3996_00.qxd 26/02/2004 13:42 Page vi

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their families and colleagues for

their support and help.

Thanks to Gosia Brykczynska who wrote the first three chapters.

Thanks also to Annie Jennings, RGN, and Andrew Jennings,

MB, FRCS(Urol), for their help in updating the colloquial language,

to Kirsten and Stuart Dallas who offered help with one of the case

histories, and to all the staff at Elsevier who were involved in the

book – in particular, Ninette Premdas and Kim Benson for their

support and enthusiasm throughout the project.

vii

C3996_00.qxd 26/02/2004 13:42 Page vii

Contributor

Gosia Brykczynska PhD, RGN/RSCN, RNT, CertEd, Refugee Nurse

Project Officer, Royal College of Nursing, London, UK (Chs 1, 2

and 3).

C3996_00.qxd 26/02/2004 13:42 Page viii

Contents

1.

Nursing in the UK

1

2.

Registering as a nurse in the UK and career

development

13

3.

The National Health Service and Social Services

25

4.

Nursing documentation, record keeping and written

communication

37

5.

Communication in nursing

51

6.

Colloquial English

123

7.

Idioms: parts of the body

141

8.

Phrasal verbs

169

9.

Abbreviations used in nursing

193

10. Useful addresses and web sources

211

11. Units of measurement

223

General further reading suggestions

231

Index

233

ix

C3996_00.qxd 26/02/2004 13:42 Page ix

C3996_00.qxd 26/02/2004 13:42 Page x

This page intentionally left blank

Nursing in the UK

INTRODUCTION

Today nursing in the UK involves caring for the whole person

(holistic care). This includes emotional, social, psychological,

spiritual and physical factors rather than just a disease or injury.

Nursing care is based on the best evidence available (evidence-

based) and focuses on the individual needs of people using the

healthcare system. Nurses are concerned as much with helping

people to stay well, as with giving care when illness or injury

occurs. Promoting health, giving information and helping people

to learn about managing chronic illnesses is the focus of nursing

in the 21st century. The developments in medical science and

technology, and the breakdown in the traditional barriers

between the healthcare professions have meant that nurses must

now deal with many complex technical aspects of care and treat-

ment. Nursing in the UK is a regulated professional occupation

with a correspondingly thorough education system that meets the

practical and theoretical needs of a modern healthcare system.

Nurse education in the UK is designed to meet changing health-

care needs, the wishes of people needing healthcare, the growth

in complex treatments and the need for a standardised education-

al preparation resulting from membership of the European Union

(EU) (see Ch. 2).

Nurses in the UK base their practice on the systematic assess-

ment, planning, implementation and evaluation of care. In order

to do this they use the nursing process (see below) or integrated

care pathways. This is very different to task-based care, where

nursing activities were strictly allocated according to the nurse’s

seniority. The more complicated tasks, such as giving medicines,

were performed by senior nurses and simple tasks were under-

1

1

C3996-01.qxd 25/02/2004 18:20 Page 1

taken by the more junior nurses, while the most basic work such

as personal cleansing was carried out by unqualified nursing stu-

dents and nursing assistants or auxiliary nurses.

This chapter will help you to understand how nursing in the

UK is regulated, what nurses do and where they work, and how

they use the nursing process. Details about various professional

organisations and trade unions are also given.

HOW NURSING IS REGULATED IN THE UK

Nursing and midwifery are regulated by the Nursing and

Midwifery Council (NMC). The role of the NMC includes:

— Keeping a register of practitioners (656 000 qualified registered

nurses and midwives in 2003). In 2004 a new three-part regis-

ter – nursing, midwifery and specialist community public

health nursing – replaced a register with 15 parts. The nursing

part of the register has separate sections for first-level and

second-level nurses. The register also notes the particular

branch of nursing – adult, learning disability, children or men-

tal health. The second-level section of the register is for exist-

ing enrolled nurses, but this is closed to new UK applicants.

However, it must be open to existing second-level nurses who

qualified in certain other European countries in order to com-

ply with European Directives. All working nurses need to reg-

ister with the NMC to practise as qualified nurses in the UK.

This registration is renewed every 3 years (see periodic regis-

tration, Ch. 2).

— Setting standards for nursing and midwifery practice.

— Protecting the public and assuring the public that only nurses

and midwives who have reached the minimum standards set

by the NMC can become registered nurses and midwives.

The NMC hears cases of alleged professional misconduct (see

nursing documentation and record keeping, Ch. 4). If the practi-

tioner is found guilty, the NMC can deal with him or her in a vari-

ety of ways, including the removal of the practitioner from the

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

2

C3996-01.qxd 25/02/2004 18:20 Page 2

professional register, which stops him or her working as a regis-

tered nurse or midwife. In this way, the NMC monitors and reg-

ulates nursing and midwifery and ensures that high standards of

professional practice are maintained.

The NMC has produced a Code of Professional Conduct that

sets out the standards of professional conduct, responsibilities

and accountability expected of a registered nurse or midwife, and

explains a person’s entitlements and reasonable healthcare

expectations about nursing care.

As part of the need to practise safely and effectively as a nurse

and to work within ethical boundaries you need to be familiar

with, to understand and to apply to your practice all parts of the

Code of Professional Conduct. The main clauses of the code are

outlined in Box 1.1, but you should read the full document which

has subclauses that give more explanation.

The Code is sent to every practising nurse in the UK, and any

nurse who does not respect the Code of Professional Conduct

will have to answer for their actions or omissions to the NMC and

others, including the hospital or care home where they work, a

court of law or the Health Service Commissioner. The British pub-

lic demand nursing care that is of a high standard and effective,

NURSING IN THE UK

3

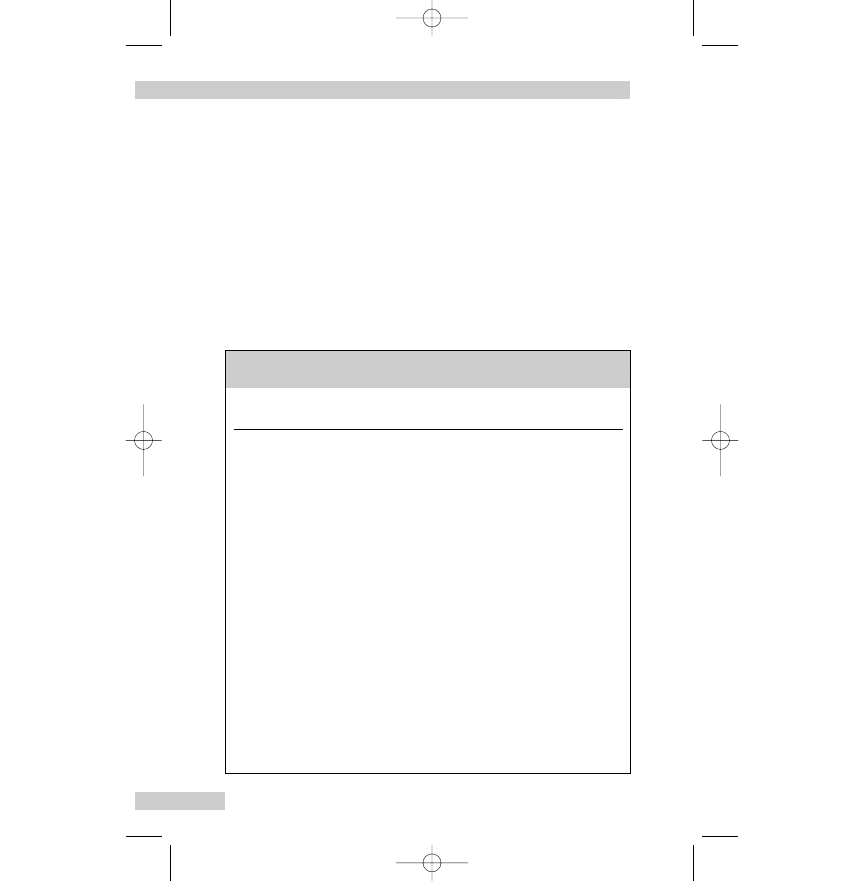

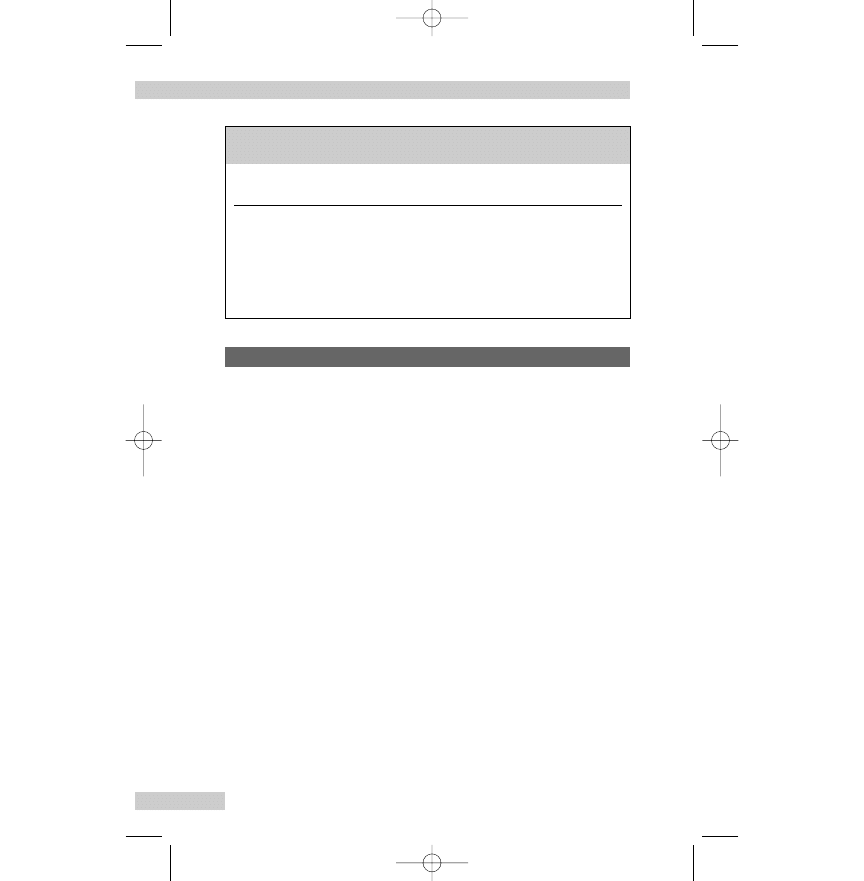

Box 1.1

The Code of Professional Conduct (NMC, 2002)

The Code of Professional Conduct says that, ‘as a registered nurse or

midwife, you are personally accountable for your practice. In caring for

patients and clients, you must’:

— ‘respect the patient or client as an individual’

— ‘obtain consent before you give any treatment or care’ (see Ch. 4)

— ‘co-operate with others in the team’

— ‘protect confidential information’

— ‘maintain your professional knowledge and competence’

— ‘be trustworthy’

— ‘act to identify and minimise the risk to patients and clients’.

Available online: http://www.nmc-uk.org

C3996-01.qxd 25/02/2004 18:20 Page 3

and nurses are constantly trying to raise their standards of care

and to identify areas for improvement. In fact, continuing profes-

sional development (CPD) and a commitment to life-long learn-

ing are both essential if the profession is to keep ahead of the

changes that are occurring and for nurses to feel confident in the

work that they are doing. For more information about CPD, post-

registration education and practice (PREP) and periodic registra-

tion, see Chapter 2.

PROFESSIONAL ORGANISATIONS AND TRADE

UNIONS

The vast majority of practising UK nurses and midwives, and stu-

dents join a professional organisation or trade union. There are

several trade unions to choose from (Box 1.2), but the two most

popular ones with nurses are the Royal College of Nursing (RCN)

and Unison, who have about 600 000 members between them.

A trade union works hard for the welfare and best interests of

its nurse members. Trade unions also provide professional

indemnity insurance for practising nurse members, as do several

private insurance companies. Nurses who are employed are cov-

ered for acts or omissions by their employer’s vicarious liability

arrangements. Professional indemnity insurance against claims for

professional negligence is increasingly important for nurses work-

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

4

Box 1.2

Trade unions and professional organisations

— The Royal College of Nursing

— Unison

— The Royal College of Midwives (RCM)

— GMB

— Mental Health Nurses' Association

— Community Practitioners' and Health Visitors' Association

— Community and District Nurses' Association.

See Chapter 10 for useful addresses and websites.

C3996-01.qxd 25/02/2004 18:20 Page 4

ing in independent or private practice, and the NMC recommends

that these nurses should have adequate insurance.

Many trade unions provide continuing education for nurses

through study days, courses, conferences and nursing journals.

Some organisations, notably the RCN and RCM, provide extensive

libraries. Furthermore, the RCN has one of the largest non-

university affiliated nursing libraries in the world.

The National Nursing Association (NNA) in the UK is the RCN.

It is a member of the International Council of Nurses (ICN), and

is the UK representative on the Standing Committee of Nurses in

Europe.

More information about the services offered by individual

trade unions and professional organisations can be found in an

article by Oxtoby & Crouch (2003) and by contacting the trade

union or professional organisation.

WHERE NURSES WORK – NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE

AND THE PRIVATE SECTOR

Most nurses and midwives (approximately 400 000) work for the

National Health Service (NHS), 80 000 work in the private sector

within independent hospitals, nursing homes, nursing agencies,

workplaces, prisons, embassies and the armed forces, and 20 000

work for general practitioners (GPs). Others work in education

institutions, in management, as independent practitioners, or as

self-employed consultants.

In the 1980s, new nurse education programmes, called Project

2000 (PK2), were introduced. This moved nurse education into

the higher education sector and nursing students were no longer

considered part of the nursing workforce, as they had been

before, and led to an increased employment of healthcare assis-

tants (HCAs) and auxiliaries. HCAs often give the ‘hands-on’ care,

and increasingly do more complex activities because the role of

nurses has expanded and changed.

Nurses today work not only in hospitals but also in the com-

munity. In fact over a third of all UK nurses work in the commu-

NURSING IN THE UK

5

C3996-01.qxd 25/02/2004 18:20 Page 5

nity – with people in their own homes and in clinics, and in the

workplace as occupational health nurses. Even when nurses are

employed in the acute healthcare sector they not only work on

the wards, but they also work in outpatient departments (OPDs)

often running and co-ordinating clinics on their own, such as in

pre-admission assessment, diabetic care, hypertension clinics,

well-men and well-women clinics, and so on. In addition, UK

nurses are increasingly taking on roles that used to be done by

doctors. This has meant that nurses can now ensure a faster and

more efficient service for people in their care.

Nurses in the UK can choose to work either for the NHS or

for the private healthcare sector. The private sector runs hospi-

tals (general and specialist), and many psychiatric hospitals and

specialist clinics (e.g. infertility clinics and drug detoxification

units). The private sector also provides much of the occupation-

al health services for industry and many private companies, and

run hundreds of nursing homes and other care facilities for older

people and other groups all over the UK. The care of older peo-

ple requires much dedication and is a difficult field of nursing,

but it can be very rewarding and certainly it is an area of nurs-

ing care that will increase in demand as more people live longer,

and proportionally more frail older people will require expert

nursing care.

Although private healthcare establishments are not bound by

NHS pay regulations, they generally pay very similar salaries and

in many instances pay slightly more. There are recruitment

guidelines and UK labour legislation helps to ensure fair and eth-

ical employment practices. Wherever a nurse works in the UK he

or she is protected by employment law and health and safety

regulations which, among other things, specify the maximum

number of hours of work to be undertaken in a specified period

of time, the minimum UK wage, and employment entitlements

and benefits.

Nursing in the UK reflects the challenges and the demands of

UK society as a whole. Nursing is considered a respected and val-

ued profession, and on the whole qualified nurses with several

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

6

C3996-01.qxd 25/02/2004 18:20 Page 6

years’ clinical experience and working full-time in a UK health-

care establishment, can expect to be adequately financially

rewarded for their expertise and practice. At the time of writing

the government is proposing a new financial package for quali-

fied nurses working in the NHS, which should redress some of

the financial problems and dissatisfactions of the past.

HIGH QUALITY CARE AND THE NURSING PROCESS

Whether you are at the beginning of your career, practising at an

advanced or specialist level, or just newly arrived to work in the

UK from abroad, all nurses must strive to achieve the five Cs of

good nursing practice:

— competent nursing

— commitment to nursing

— confidence in nursing research

— nursing compassion

— informed nursing conscience.

These aspects of caring nursing practice were first expressed by

Simone Roach, a Canadian nurse, in 1984 (Roach 1984). All five

aspects of nursing practice are needed for effective, high-quality

nursing care. It is the caring aspect of nursing work that is most

appreciated by people and their families, and nurses everywhere

are delivering good patient care by demonstrating competency,

commitment, confidence, conscience and compassion in their

work. In many parts of the world, including the UK, these aspects

of nursing care are best shown in nursing practice by using the

nursing process.

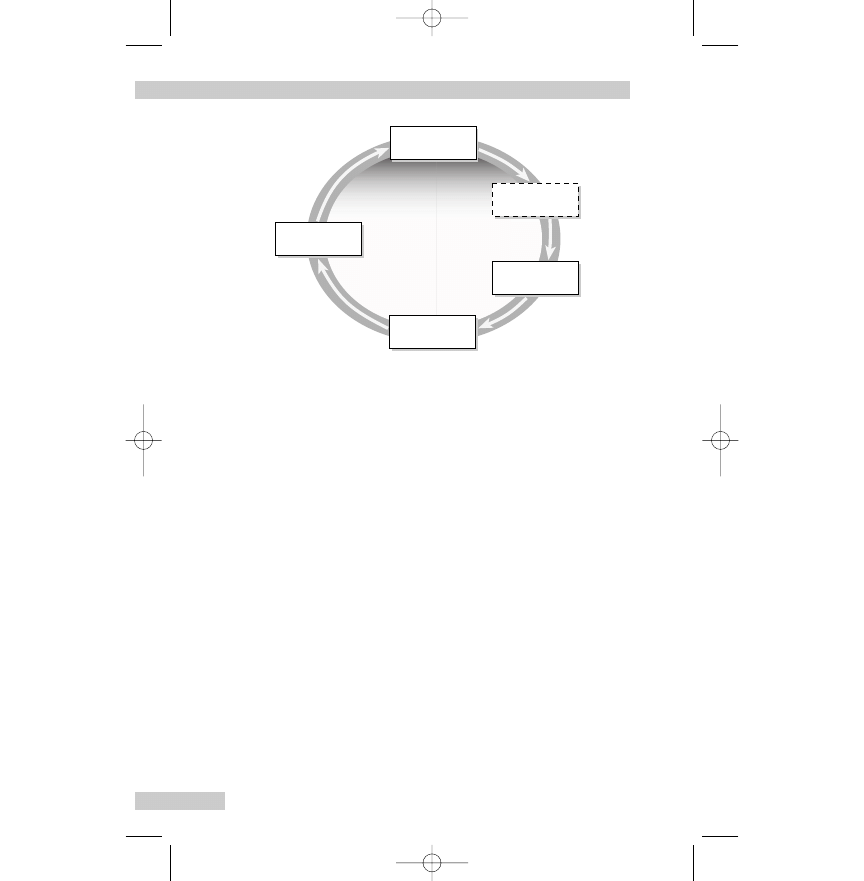

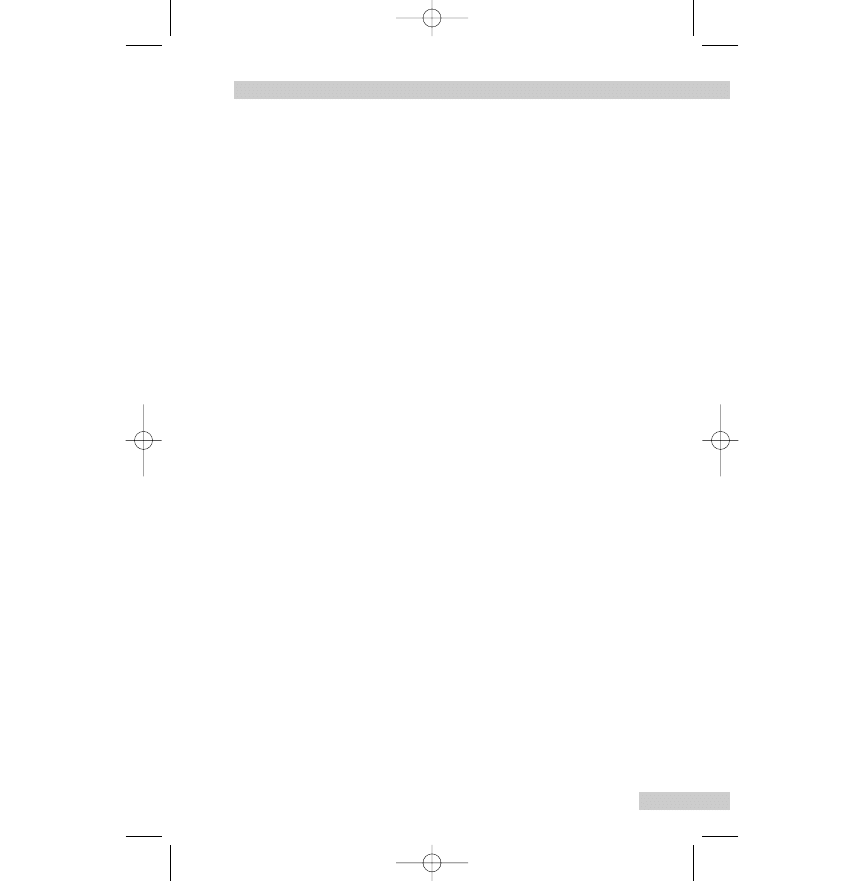

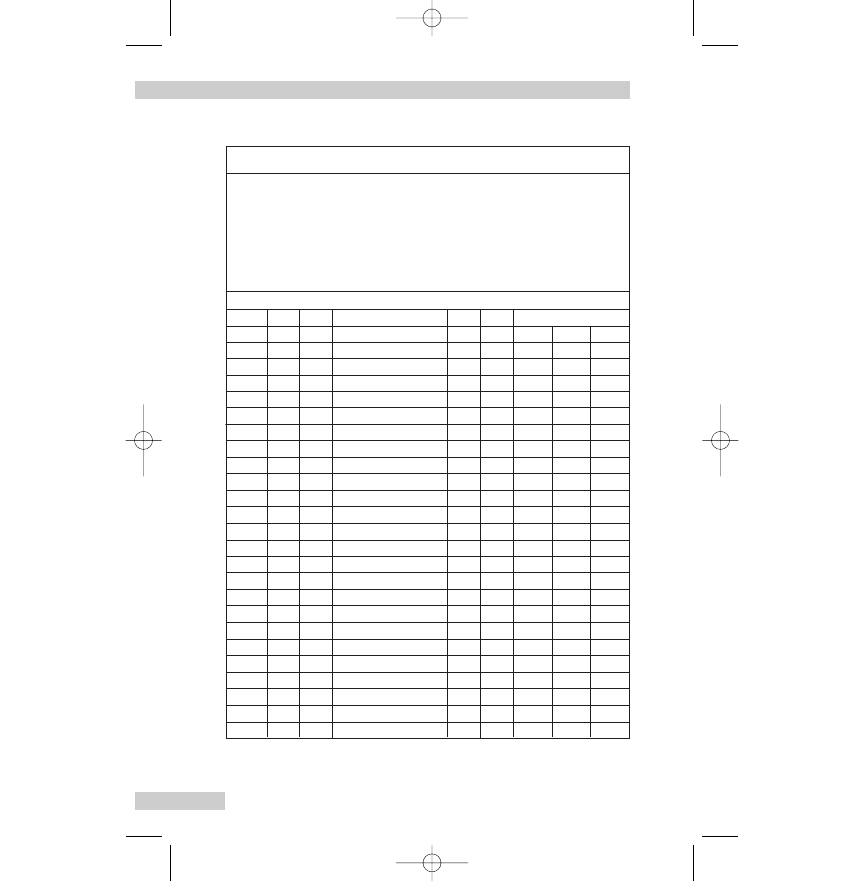

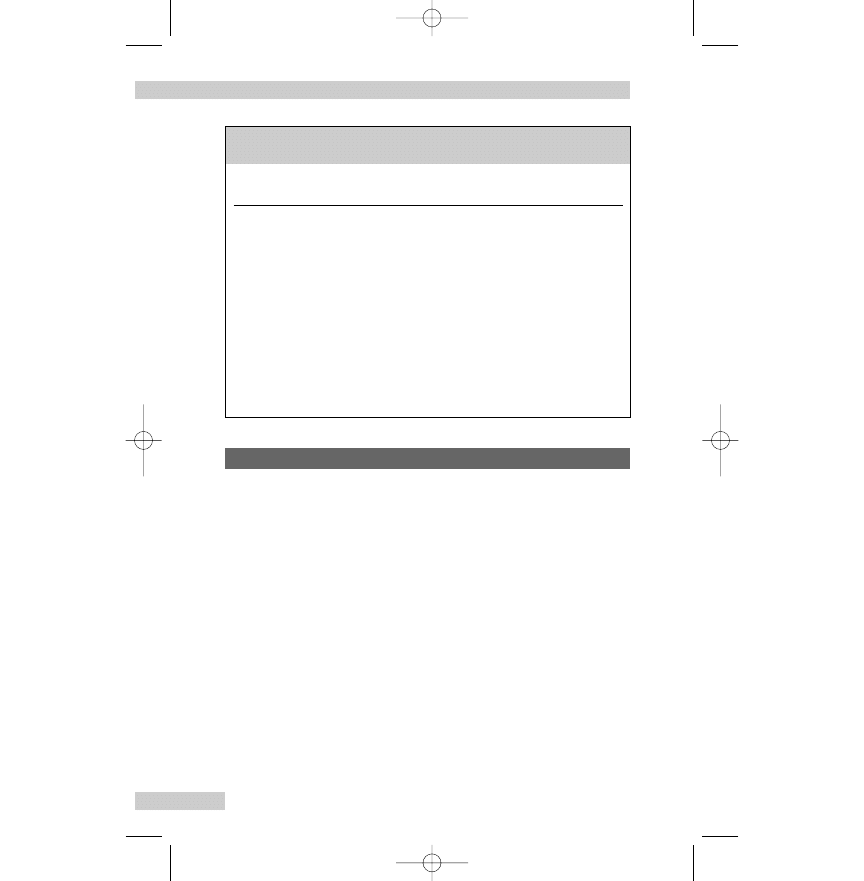

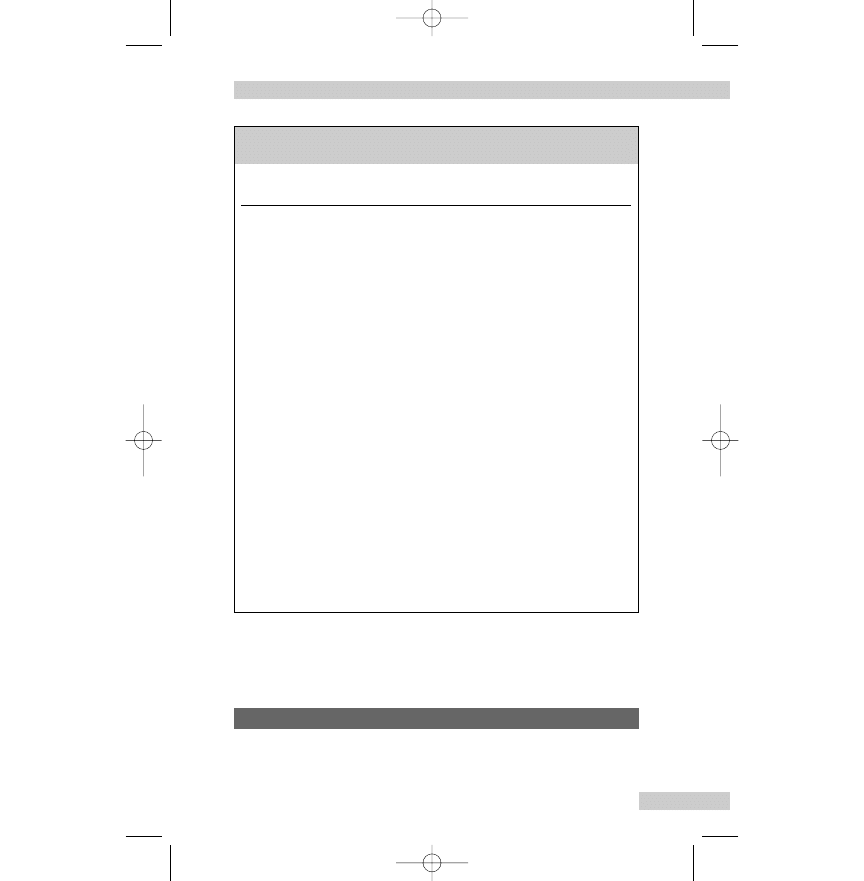

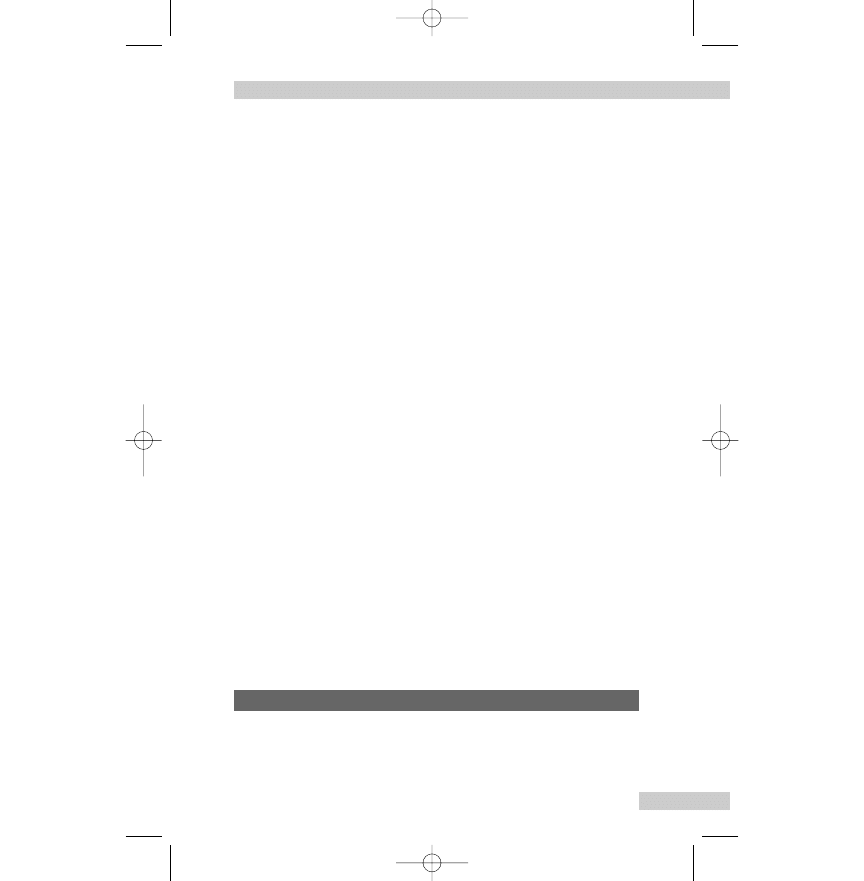

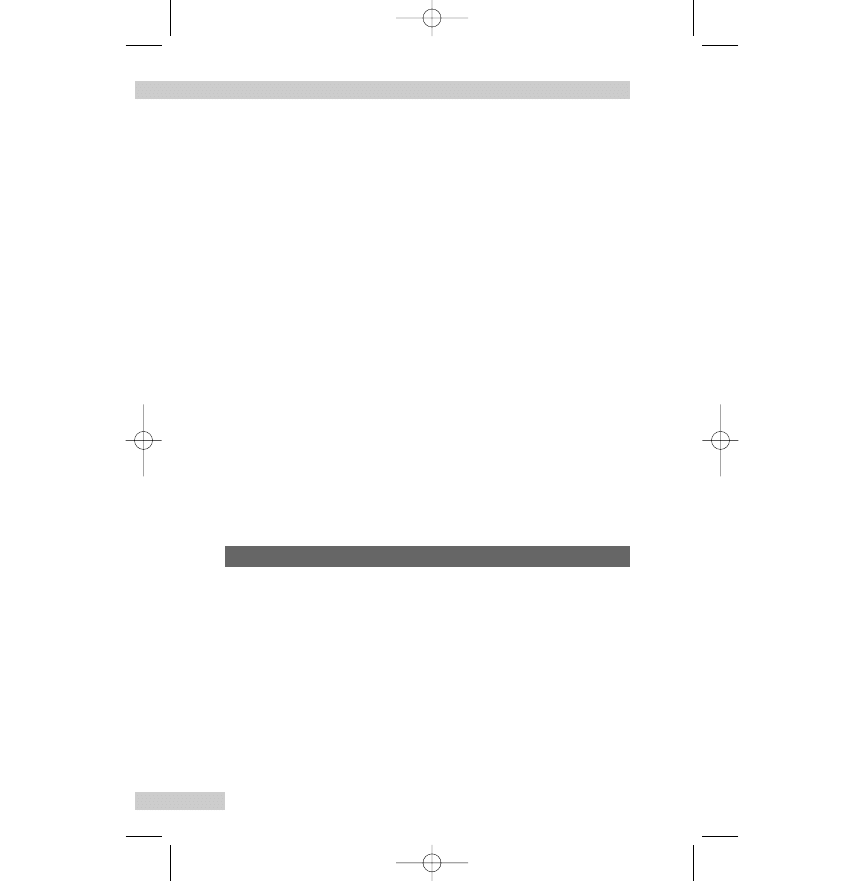

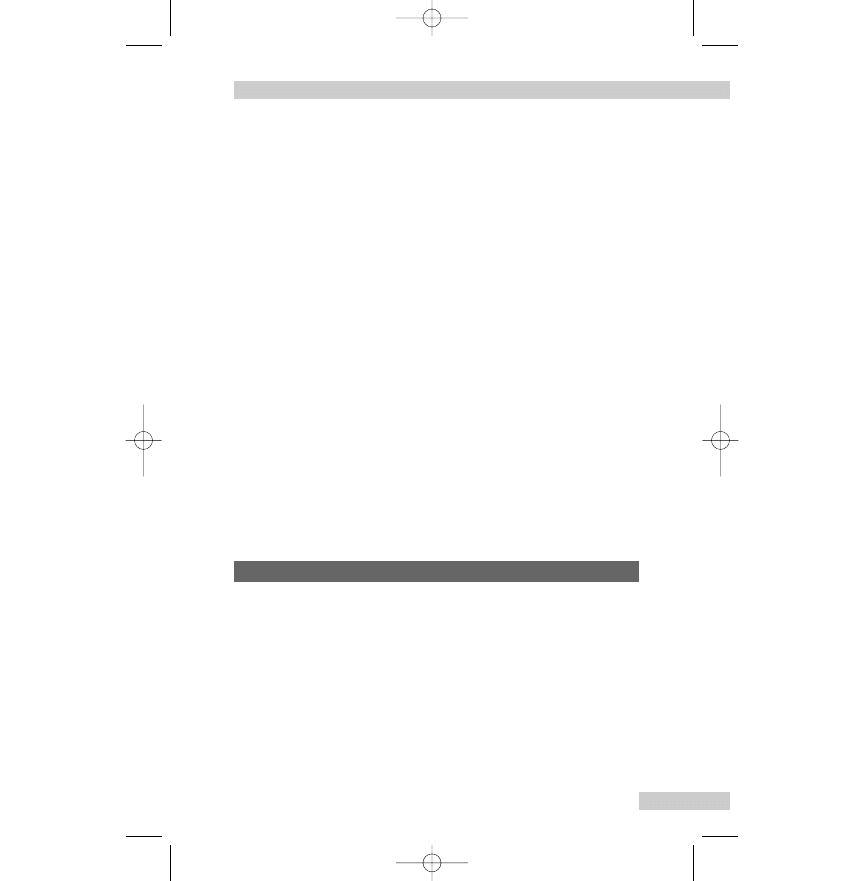

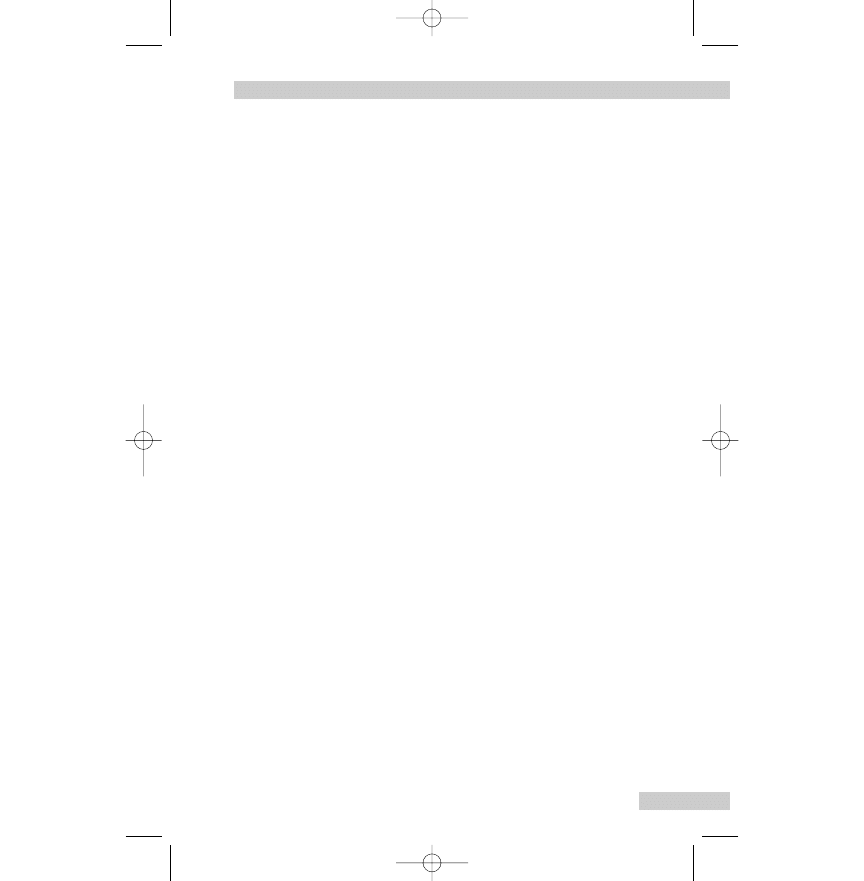

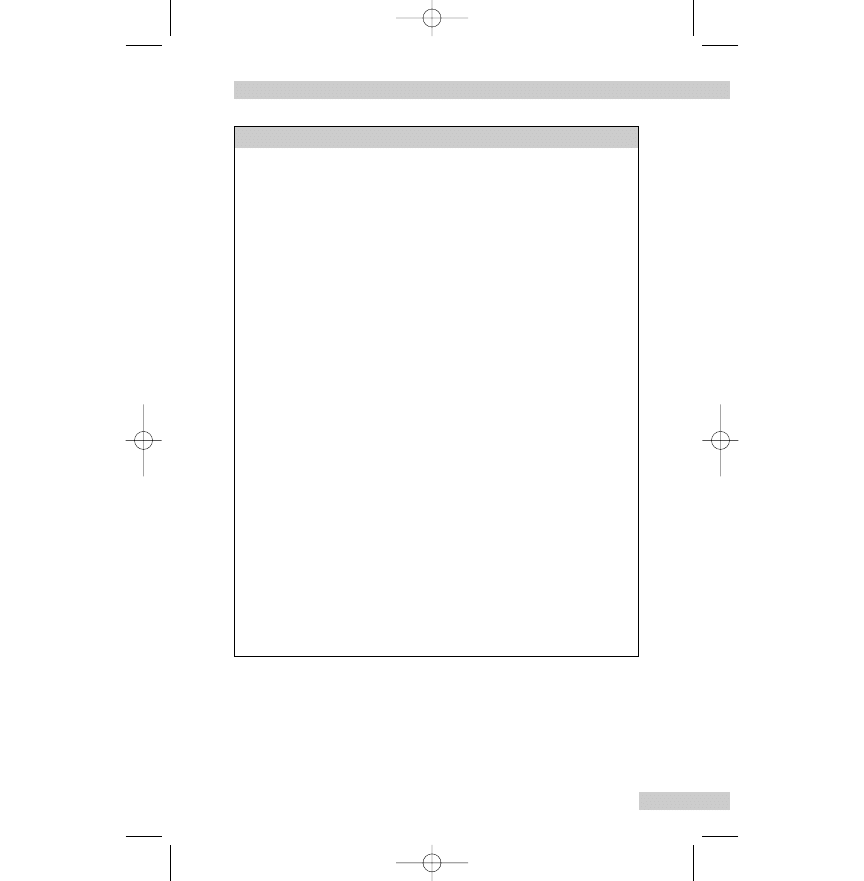

The nursing process is a systematic approach to nursing care.

It has four phases (Fig. 1.1):

— assessment

— planning

— implementation

— evaluation.

NURSING IN THE UK

7

C3996-01.qxd 25/02/2004 18:20 Page 7

Although the four phases are described in sequence, in reality

they overlap, and occur and recur throughout the period for

which a person is receiving nursing care.

The nursing assessment refers to assessing a person (patient

or client) for physical, psychological, social or spiritual needs

and deciding on their relative nursing value. The status of the

person is assessed in order to help with planning the nursing

care plan.

The care plan is prepared with a specific person in mind; how-

ever, it is possible to have a prepared standard care plan, which

is then adapted and individualised for a particular person’s needs.

This often happens on day-case surgery units and surgical wards

where routine surgical procedures are undertaken. Such an

approach ensures that not only are routine procedures undertak-

en, but also that the care can be individualised. Care plans may

be hand written or, as is increasingly the case, stored on comput-

ers. In both instances, the information is confidential and should

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

8

Assessment

Implementation

Planning

Nursing

diagnosis

Evaluation

Fig. 1.1

The nursing process. Reproduced with permission from

Brooker & Nicol (eds), Nursing Adults: the Practice of Caring,

Mosby, 2003.

C3996-01.qxd 25/02/2004 18:20 Page 8

be held/stored in a safe place (see Ch. 4). In the UK, patients are

entitled to know their diagnosis, to be included in care planning

and to be consulted at every point of the nursing process cycle.

This is to ensure fully informed and freely given consent to the

care proposed (see Ch. 4).

The implementation of the care plan is based on the initial

assessment process and the care delivered is expected to be

evidence-based (i.e. in accordance with the latest nursing

research findings and medical knowledge). If research findings

are not available the evidence may be developed from the collec-

tion of best expert practice in the field. It is the responsibility of

individual nurses to keep themselves updated in nursing practice,

as they are individually accountable for patient care.

The final stage of the nursing process is the evaluation. At this

point the nurse evaluates the effectiveness of the care delivered

and either decides to continue with the current care plan, con-

siders making changes, or moves on to another new assessment

and care plan, as the person is now at another stage and has dif-

ferent needs. Evaluation must be undertaken against some meas-

urement or established criteria (e.g. a pressure ulcer risk scale).

This stage of the care plan is very important, as otherwise the

nurse runs the risk of continuing to give ineffective and or inap-

propriate care.

The nursing process is used effectively by all nurses in the UK,

regardless of their speciality, and as you gain clinical experience

so it becomes easier to move through the stages of the process.

As you would expect the nursing process needs a caring and

knowledgeable approach and is usually made easier by using an

established model or theory of nursing practice, such as the

Roper, Tierney & Logan (1996) model of nursing based on activ-

ities of living or Orem’s self-care model (1995). The result is that

nursing care is being delivered more appropriately, effectively

and in ways that promote holistic well-being.

Nurses should record all the relevant information at all stages

of the nursing process (see Ch. 4).

NURSING IN THE UK

9

C3996-01.qxd 25/02/2004 18:20 Page 9

AN EXCITING FUTURE – EXPANDING THE ROLE OF

NURSES

In 1999 the UK Government issued a document for nurses to con-

sider: NHS Plan for England (Department of Health 1999) in

which it set out areas that it felt needed to be expanded and to

become more mainstream, so that more nurses could be involved

working in these areas in new and more challenging nursing

roles. The areas were:

— to be capable of and responsible for ordering medical investi-

gations, such as pathology tests and X-rays

— to be capable of making direct referrals to specialist services,

such as a pain control team or the continence adviser

— to have responsibility for both admitting and discharging a

range of patients with specified conditions according to a

protocol

— for more nurses to manage their own patient caseloads, e.g. in

the care of people with diabetes

— to increase the number of nurses who would be educated to

prescribe medicines and treatments

— for nurses to be responsible for resuscitation procedures,

including the use of defibrillation

— to be trained to undertake minor surgery and outpatient

procedures

— to be responsible for the administration of outpatient clinics

— to take lead roles and executive positions in local health ser-

vices and their management.

Nurses now have the chance to expand their practice, such as

prescribing medicines, and diagnosing and treating many minor

injuries and illnesses, as well as continuing to give holistic care,

especially for those people with chronic conditions. Nurses work

in ever more sophisticated and technologically advanced settings

(e.g. in oncology units, endoscopy suites, neonatal units and

renal and dialysis units). This requires a high level of basic nurs-

ing care, continuing post-basic specialist knowledge, a system of

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

10

C3996-01.qxd 25/02/2004 18:20 Page 10

advanced nursing education to reflect the increased and variable

nursing work environments and an ethical viewpoint that is

informed and sensitive to the needs of people and their families.

The next two chapters will help you to understand the routes and

methods of achieving these specialisations and to have a basic

understanding of the UK healthcare system and the role and func-

tion of nursing within it.

REFERENCES

Department of Health (DoH) 2000 The NHS plan. DoH, London.

Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) 2002 Code of professional

conduct. NMC, London.

Orem DE 1995 Nursing: concepts and practice, 5th edn. Mosby,

St. Louis.

Roach S 1984 Caring: the human mode of being, implications

for nursing. Perspective in caring. Monograph 1. Faculty of

Nursing, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Roper N, Logan WW, Tierney AJ 1996 The elements of nursing,

4th edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

FURTHER READING

Brooker C, Nicol M (eds) 2003 Nursing adults: the practice of

caring. Mosby, Edinburgh, Ch. 1.

Oxtoby K, Crouch D 2003 Value for money. Nursing Times

99(17):21–23.

Royal College of Nursing (RCN) 2002 Labour market review.

RCN, London.

NURSING IN THE UK

11

C3996-01.qxd 25/02/2004 18:20 Page 11

C3996-01.qxd 25/02/2004 18:20 Page 12

This page intentionally left blank

Registering as a nurse in

the UK and career

development

INTRODUCTION

Of all the European countries, the UK has the largest number of

overseas trained nurses working within the healthcare system. It

is estimated that there are about 42 000 internationally recruited

nurses practising in the UK, with another 16 000 waiting for place-

ments on supervised practice courses. Every nurse who works in

the UK needs to be registered with the Nursing and Midwifery

Council (NMC). Since 1919 nurses have been regulated in the UK

(Nurse Registration Act) and the NMC is the latest statutory body

set up by Parliament to perform this regulatory role. The NMC

was established in April 2002 and replaced The UK Central

Council for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting (UKCC). The

change in regulatory body coincided with a change in the way

that the nursing profession was to be organised and administered

around the country and was in keeping with major changes

occurring in the delivery of healthcare in the UK (see Ch. 3). One

of the NMC’s main functions is to protect the public by ensuring

that all those who are registered to work as Registered Nurses

(RNs) in the UK are considered to be safe and competent nurs-

ing practitioners (see Ch. 1).

This chapter will help you to understand how to obtain initial

registration with the NMC and the requirements for periodic reg-

istration. There is further information about adaptation courses,

and in addition the chapter will help you to develop your career

and be successful as a nurse in the UK.

13

2

C3996_02.qxd 25/02/2004 18:21 Page 13

NURSING PROGRAMMES AND OBTAINING

REGISTRATION

The first thing an overseas trained nurse must do to get onto the

NMC register is to write to the NMC (for the address see Ch. 10)

for an application pack. The pack gives information about pay-

ments and how to fill out the forms and what is needed to

become a nurse in the UK. Information on how to apply to the

NMC for registration can also be obtained from the NMC website

(http://www.nmc-uk.org). The first sum of money you send off

to the NMC is to cover the administration cost of processing the

application forms. Refugee nurses do not have to pay the initial

fee if they send the NMC a copy of the letter from the Home

Office confirming their refugee status.

It is the NMC who will determine whether you are a safe and

competent practitioner to work in the UK. This is done by look-

ing at all applications on an individual basis. The NMC will assess

several different things about you; for example, your nursing edu-

cation, character references (from your school of nursing and

employers), and experience and career pathway.

Nursing education models vary considerably around the world

and Registered Nurses may undertake courses that last anything

from 1 to 4 years. Some nurses have been educated at universi-

ties and colleges of higher education, others on pre-matriculation

courses (before leaving secondary school) and also in specialised

nursing further education institutes, which are often attached to

specific teaching hospitals.

In some countries nursing programmes follow a universal

healthcare career structure, where all or many of the healthcare

workers progress together through a generic health worker train-

ing programme. However, some individuals remain at particular

levels, while others will continue their education to gain more

experience and thereby change the role that they are qualified to

undertake. In other countries nurse education is completely sep-

arate from other healthcare professions. In the UK all nurse edu-

cation, wherever it is provided, follows the European Union (EU)

Directives on the nature and length of nurse education

programmes.

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

14

C3996_02.qxd 25/02/2004 18:21 Page 14

The majority of overseas trained nurses will be seeking to have

their name put on the nursing part of the register (for more infor-

mation on the three-part register, see Ch. 1) and most of these

will be for adult nursing. To be placed on the register you need

to demonstrate that your nursing education programme meets the

conditions outlined in Box 2.1.

These rules and regulations were agreed by the EU and have

been agreed as valid for the whole of Europe. This was agreed in

REGISTERING AS A NURSE IN THE UK AND CAREER DEVELOPMENT

15

Box 2.1

Nurse education programmes – conditions required

for UK registration

— Duration of at least 3 years of full-time nursing studies and which

included at least 4600 hours of nursing education.This means that

unrelated subjects, such as foreign languages, sport or philosophy, do

not count towards the nursing education hours, but applied subjects

such as healthcare ethics would be relevant.

— The nursing programme does not have to be delivered at a degree

level, but it should be undertaken after completion of full secondary

education and after reaching the age of 17.

— The nursing programme needs to be equally divided between theory

and practice and the programme must cover five main areas, i.e. med-

ical, surgical, women and children, mental health and community.

— Upon completion of the nursing education programme, nursing stu-

dents should be considered to be fully qualified registerable first-level

nurses and fully capable of obtaining the nursing diploma and right to

practise.This implies that the nursing education programme is consid-

ered to be complete in itself and without additional practice periods

and/or supervision, and that until nursing students obtain the nursing

diploma they are not considered to be fully qualified first-level nurses.

Apart from these requirements, the NMC requests that nurses complete

at least 6 months of nursing work in their home country to consolidate

their educational experience. Nurses trying to obtain UK registration

without 6 months' experience in their home country might experience

problems getting onto the register.

C3996_02.qxd 25/02/2004 18:21 Page 15

an effort to standardise the level of nurse education in Europe,

and thereby enable automatic recognition of qualifications

between the countries of the EU. Thus, if a qualified nurse from,

for example, Zambia obtains nursing recognition from the NMC

as a fully qualified first-level nurse in the UK, and obtains an NMC

Professional Identification Number (PIN) and is put on the UK

nursing register, the UK registration and recognition is valid

throughout the whole of Europe. It means that Registered Nurses

can easily move around within the EU for purposes of continuing

nurse training and obtaining professional work.

The same rules ensure that the levels of nurse education are

automatically raised overall. With the introduction of this type of

nurse education the countries of Europe were asked to close their

second-level nursing programmes. The only way to become a

nurse in the EU today is by undertaking a 3-year programme of

full-time education at post-secondary school level, as already

described. The only nurses in Europe who are practising on the

second-level register are those nurses who completed their train-

ing before the new regulations came into force, either from the

UK or from other EU countries.

Will your application be accepted?

The NMC may accept your qualifications, require you to do an

adaptation course, or insist on further training:

1. The NMC may fully recognise your qualifications, and because

the education programme was conducted in English and it

covered the European nursing education requirements you

can be admitted onto the register without any additional

requirements. This is the common situation if you have com-

pleted university degrees in nursing from North America,

Australia or New Zealand and have sufficient additional prac-

tical nursing experience.

2. The vast majority of all other nurses will receive a letter from

the NMC stating that their qualifications are sufficient for them

to be put on the NMC register but that now they must com-

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

16

C3996_02.qxd 25/02/2004 18:21 Page 16

plete an adaptation programme (supervised practice) in an

approved healthcare establishment in the UK over a specified

period of time. This can range from 3 months to 1 year, but

most commonly is for a period between 3 and 6 months.

3. Some non-EU trained nurses will be asked to undertake more

pre-registration nurse education before they can be put on the

UK register. Meanwhile, some of their original nurse training

can be considered valid and academic credits can be awarded

towards the new UK pre-registration nursing education. This

process of giving credit for prior education is called

Accreditation of Prior Experience and Learning (APEL). Every

school of nursing in the UK can undertake this accreditation

process for overseas-trained nurses. APEL was put into place

to help adult mature entrants return to formal education to

obtain new skills, and now this process is being extended to

include previous achievements, even those gained overseas. It

is a long process, but well worth undertaking.

The NMC may ask you for more information before they make

a decision, or reject your application if your nursing course was

less than 3 years long or you cannot meet other requirements (see

Box 2.1).

Once you have completed all the requirements set by the NMC

and sent your initial registration payment to the NMC, you will

receive a PIN and a copy of the NMC Code of Professional

Conduct (see Ch. 1).

Adaptation programmes (supervised practice)

Unfortunately there are not enough places on adaptation pro-

grammes. Although almost all acute NHS Trusts and many

Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) do provide adaptation programmes,

there are still not enough to provide adaptation placements for

the large numbers of overseas trained nurses wishing to work in

the UK.

Adaptation programmes for overseas trained nurses are run

jointly by the NHS Trusts who provide access to the clinical areas

REGISTERING AS A NURSE IN THE UK AND CAREER DEVELOPMENT

17

C3996_02.qxd 25/02/2004 18:21 Page 17

and the necessary mentors and schools of nursing, who provide

the lecturers and teaching support. Some approved supervised

placements can also be undertaken in the independent sector,

predominantly in care homes for older people. There is a short-

age of placements for supervised practice because there are not

enough qualified nurses to undertake the training necessary to

become mentors, and the clinical areas are already completely

full of pre- and post-registration nursing students. The authorities

who commission and fund adaptation programmes are trying to

increase the number of placements. The NMC is also beginning

to look at other ways of assessing nurses’ readiness to practise in

the UK, such as by passing an examination, which may or may

not include a clinical component, but all these alternatives are still

a long way away.

It is because of these logistical problems that the NMC recom-

mends that overseas trained nurses do not arrive in the UK until

they have a guaranteed place on an approved adaptation course,

since at the time of writing there is an estimated 2- to 3-year back-

log in getting onto an adaptation programme in the UK.

Communication in English – International English Language

Testing System

Overseas trained nurses need to be able to demonstrate the use

of the English language to a level that is good enough to commu-

nicate with colleagues and patients and to function safely in the

clinical environment. The NMC currently requires that all overseas

trained nurses who completed their training in a language other

than English need to pass the International English Language

Testing System (IELTS) examination. The IELTS is a specific

English language test that is administered by the British Council

in centres worldwide. The IELTS test required for nurses is the

General Test, and this consists of several sections, such as com-

prehension and communication. All these sections need to be

completed successfully with a minimum grade of 5.5; however,

an overall grade of 6.5 must finally be achieved. Many nurses find

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

18

C3996_02.qxd 25/02/2004 18:21 Page 18

the examination difficult and not necessarily appropriate for nurs-

ing practice. The NMC is considering several other possibilities,

but one thing is sure – nurses whose first language is not English

will need to demonstrate that they have a reasonable command

of the English language. In addition to needing sufficient English

to function safely in clinical areas and with patients, overseas

trained nurses will need the equivalent of IELTS grade 6.5 in

order to undertake further nursing education at a UK university.

PERIODIC REGISTRATION AND CONTINUING

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Periodic registration

The nursing register is constantly being updated, and you will

need to update your right to be on the register by periodic regis-

tration. The right to practise as a nurse in the UK is not only

dependent on paying an initial fee, but you must also complete

a Notification of Practice form every 3 years and pay another fee,

and fulfil certain requirements for post-registration education and

practice (PREP) (Box 2.2).

Continuing professional development

Continuing professional development (CPD) can be gained in a

number of ways, for example:

— Reading professional articles in the nursing press, such as the

Professional Nurse, Nursing Times or Nursing Standard. Doing

literature searches relevant to your area of practice.

— Visiting other units.

— Ward teaching sessions, study days, conferences or seminars.

— Short courses, such as moving and handling, managing aggres-

sion and pain control. Longer courses, such as a degree, or

studies that lead to registration on another part of the NMC

nursing register, or the community public health nursing or

midwifery parts of the register.

REGISTERING AS A NURSE IN THE UK AND CAREER DEVELOPMENT

19

C3996_02.qxd 25/02/2004 18:21 Page 19

The important thing is that you are able to demonstrate an

approach to professional nursing that is consistent with the prin-

ciples of life-long learning. The way to do this is to keep a per-

sonal professional profile/portfolio that contains evidence of all

the CPD activities you have achieved over a 3-year period. This

is a requirement for PREP, and if you keep your profile up to date

you will always be ready for periodic registration.

It is vital to reflect on your CPD activities, so you can identify

what you have learned and its relevance to your practice.

Reflection is an important part of all nursing activity, which of

course ties into the evaluation stage of the nursing process (see

Ch. 1). Many overseas trained nurses will already have been

asked to undertake a reflective diary on their adaptation course,

so you will probably be familiar with this approach. Reflecting on

personal nursing practice is crucial to meaningful CPD.

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

20

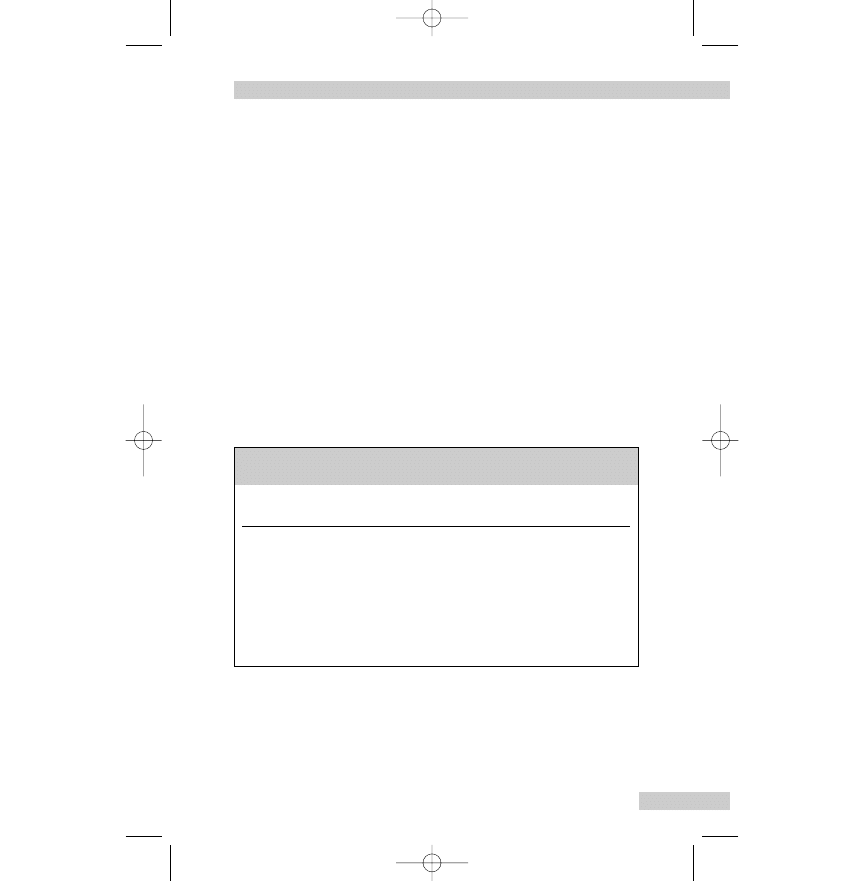

Box 2.2

Post-registration education and practice (PREP)

The requirements for periodic registration are:

— undertake a minimum of 5 days or 35 hours of learning that is rele-

vant to their practice (see Continuing Professional Development

(CPD), p. 19)

— work in some capacity by virtue of their nursing qualifications for a

minimum of 750 hours (100 days) during the last 5 years, or have

done a return to practice course

— keep a personal professional profile of their learning (see Further

Reading and Resources at the end of this chapter)

— comply with any request by the NMC to check (audit) how the

requirements have been met.

The NMC states that the CPD requirements for PREP can be achieved in

many different ways and need not cost a lot of money (see Further

Reading and Resources at the end of this chapter).

C3996_02.qxd 25/02/2004 18:21 Page 20

DEVELOPING YOUR CAREER

Some adaptation placements, nursing courses and all job vacan-

cies are published in the nursing press and sometimes in local

newspapers. It may also be a good idea to go to the local hospi-

tal or PCT headquarters and look at the job vacancies bulletin

board. The NMC also provides a website of job vacancies

(http://www.nmc4jobs.com). Whether you are applying for an

adaptation placement or for a first nursing job after completing

the supervised practice, you will need to complete a curriculum

vitae (CV) (see Further Reading and Resources at the end of this

chapter), to fill out an application form, and if short-listed you

will need to attend an interview. It is really important that the

application form is filled out correctly and that your CV is com-

plete, so that the reader (i.e. the prospective employer) knows

who you are, what you have done and why you want the job. If

you do not provide all the information you are unlikely to get

short-listed for an interview.

Many teachers of English as a Second Language (ESOL) and

IELTS classes will help you write a CV and explain how to fill out

application forms. In addition, you can ask for help from Job

Centres or your nursing mentors, whoever is more accessible and

appropriate. There are also many books about how to complete

application forms and a CV, and how to prepare for interviews.

These can be found in public and nursing libraries.

Preparing for a job interview is time well spent – you should,

for example, be familiar with the job description and any special

responsibilities of the post (see Further Reading and Resources at

the end of this chapter). If you are unable to attend on the date

given for an interview it is considered polite to inform the per-

sonnel department; as they were impressed enough to invite you

for interview they may well offer you another date. It is essential

to give yourself plenty of time to get to the interview, to be punc-

tual, to be prepared and to be positive about the experience,

however nervous you may be. If you find you are going to be late

for a reason beyond your control, it is a good idea if at all possi-

REGISTERING AS A NURSE IN THE UK AND CAREER DEVELOPMENT

21

C3996_02.qxd 25/02/2004 18:21 Page 21

ble to telephone and explain the situation. That way, they may

even offer you another time to attend the interview.

At the start of your UK nursing career (whether in the National

Health Service (NHS) or the private sector) you will be placed on

a fairly basic salary grade, most probably grade D or E (see Ch.

3). When you are ready for more responsibility and can work in

more specialised areas you will be given the opportunity to apply

for more senior posts and develop your nursing career. The NHS

pay and career structure is undergoing change, and a new system

of payment and assessing workloads and work definitions is

being piloted and will then be introduced nationwide (Agenda

for Change, Department of Health 1999).

Most employers require nurse managers, including ward sisters

and charge nurses to have at least a first degree in nursing or a

relevant subject and usually evidence of specialisation in the

work undertaken in the clinical area. Nursing degrees (first and

higher degrees) are offered by schools of nursing which are

based in universities. A degree can last from between 1 and

3 years, depending on the existing level of nursing education.

There are many opportunities for advancing your nursing career

through education, and many of these are sponsored by the NHS.

It is common nowadays for your manager to do periodic

reviews of your work with you. When you have a review meet-

ing it is important to talk about your career plans and to start

mapping out (planning and deciding) how you plan to achieve

your nursing goals. Moving around clinical areas is one way of

gaining new experience, but most UK nurses progress slowly

through a given specialty, becoming more expert in specific

aspects of nursing care (e.g. pain control, stoma care, tissue via-

bility or substance misuse).

REFERENCES

Department of Health (DoH) 1999 Agenda for change. DoH,

London.

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

22

C3996_02.qxd 25/02/2004 18:21 Page 22

FURTHER READING AND RESOURCES

Banks C 2003 How to ... excel at interview. Nursing Times

99(33):58–59.

Hyde J 2002 In: Brooker C (ed). Churchill Livingstone’s

dictionary of nursing, 18th edn. Churchill Livingstone,

Edinburgh, p 512–518.

Hoban V 2003 How to ... write a CV. Nursing Times

99(27):52–53.

Registering as a nurse or midwife in the UK, see the NMC

website: http://www.nmc-uk.org

REGISTERING AS A NURSE IN THE UK AND CAREER DEVELOPMENT

23

C3996_02.qxd 25/02/2004 18:21 Page 23

C3996_02.qxd 25/02/2004 18:21 Page 24

This page intentionally left blank

The National Health

Service and Social

Services

INTRODUCTION

Since 1948 the healthcare system in the UK has been structured

around the National Health Service (NHS) and social welfare has

been delivered by local Social Service agencies. Both systems are

maintained from the contributions of UK taxpayers, but the servi-

ces are available to everyone, whether they pay taxes or not, such

as children and some older people.

Although the NHS and Social Services have changed dramati-

cally over the years, most people in the UK still want a national

healthcare and social welfare system to continue to serve the

whole population. Currently, the NHS is undergoing further struc-

tural change, which is aimed at improving the services to the pub-

lic and making NHS workers more accountable to patients and

UK taxpayers.

There are over a million people working for the NHS, as

healthcare professionals and individuals supporting the clinical

staff, such as electricians, gardeners, managers and clerical staff.

The public sector NHS provides over 75% of the healthcare deliv-

ered in the UK.

This chapter will help you understand how the NHS is organ-

ised in England (services in Wales may be different and in

Scotland services are organised differently) and explain the vari-

ous roles of people within the NHS and the close links between

the NHS and Social Services.

25

3

C3996_03.qxd 26/02/2004 13:45 Page 25

THE STRUCTURE OF THE NHS

The NHS is the responsibility of the Department of Health (DoH)

with a remit to deliver comprehensive healthcare to the public.

This ranges from primary care, including access to general prac-

titioners (GPs), screening programmes, maternity care, mental

health, secondary (surgical and medical) care in hospitals, spe-

cialist hospitals, and through to care of chronically ill people and

those needing palliative care.

New developments in medical science place extra demands on

the NHS and means that treatment provision needs to keep

changing, as do the medicines that doctors and nurses can pre-

scribe. It is one of the aims of the DoH to ensure that all treat-

ments delivered by the NHS are evaluated and evidence based.

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) is the gov-

ernment agency set up to evaluate new treatments and drugs and

provide guidance (see Further Reading and Resources at the end

of this chapter). This is to guarantee that the best care is deliv-

ered by the most cost-effective method.

In the last few years the DoH has launched NHS Direct, an

innovative service with a completely new approach to healthcare.

NHS Direct is a telephone helpline (0845 4647), which aims to

empower individuals and prevent the inappropriate use of GPs

and emergency departments for minor conditions, by providing

information and healthcare advice. NHS Direct is operated

24 hours a day by qualified nurses and health workers. The oper-

ators recommend what the caller should do (e.g. call an emer-

gency ambulance, make an appointment to see their GP, or take

a simple self-care remedy). The service empowers people to take

responsibility for their health and the choices that they make. NHS

Direct also provides web-based information about healthcare and

the NHS (www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk).

The DoH manages the overall health and social care system,

develops policy and manages changes in the NHS, regulates and

inspects health and social care establishments and services and

intervenes when necessary to improve services.

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

26

C3996_03.qxd 26/02/2004 13:45 Page 26

The work of the DoH is divided into two main areas:

— Strategic Health Authorities (SHAs), based on specific geo-

graphical regions. The SHAs ensure that NHS Trusts deliver the

healthcare that has been commissioned, and they oversee var-

ious aspects of workforce planning (e.g. monitoring and

arranging the training of healthcare workers, including nurs-

es). They work with NHS Trusts and universities to plan and

support clinical placements for overseas trained nurses (see

Ch. 2). The SHA is responsible for strategic healthcare plan-

ning and for ensuring that national priorities are integrated

into the work of the Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) and NHS

Trusts (see below). Thus the SHA is concerned with primary

healthcare and community services, which are organised by

the PCTs, and acute hospital (secondary) services provided by

NHS Trusts. Mental healthcare (delivered by mental health

nurses) may be delivered either through the services of a spe-

cial Psychiatric NHS Trust (covering inpatient and outpa-

tient/community services) or by a Community NHS Trust (i.e.

a PCT) or a General NHS Hospital Trust.

— Special health authorities, called Special Trusts. Special Trusts

are usually considered to be secondary care providers or

sometimes tertiary referral centres, such as the Hospital for

Sick Children in London. Other Special Trusts include some

inpatient units designated for forensic psychiatry.

Primary Care Trusts

PCTs work closely with Social Services (see below) and other

agencies and organisations to assess local health needs, plan,

develop and deliver community and primary healthcare services,

and commission secondary services for the local population, in

order to improve health and reduce inequalities in health. PCTs

are responsible for public health and various intermediate care

services. The SHA is responsible for the performance manage-

ment of PCTs. Over recent years there has been a huge shift in

how and where healthcare is delivered and much more care is

THE NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE AND SOCIAL SERVICES

27

C3996_03.qxd 26/02/2004 13:45 Page 27

provided within the community (person’s home, care homes,

NHS walk-in centres, healthcare clinics, etc.) by Primary

Healthcare Teams (PHCTs) comprising nurses, midwives, doctors,

therapists, etc. In addition, pharmacists, dentists, opticians and

optometrists, and podiatrists all work within the community.

Primary Healthcare Team

GPs usually work in a group practice with several doctors who

work within a team comprising practice nurses, district nurses

(DNs), health visitors (HV), community midwives, community

mental health nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists,

speech and language therapists, counsellors and podiatrists, etc.

Other professionals involved include school nurses (school health

advisers), dieticians, etc. The PHCT delivers basic medical servic-

es, community care and liaises with local acute NHS Trusts for the

continued and ongoing care of their patients. Practice nurses and

GPs are usually the first point of contact for the person who is

unwell or needs healthcare advice.

The nursing and midwifery roles within the team include:

— The practice nurse is a Registered Nurse (adult) who works

alongside the GP in the GP surgery and often runs specialised

clinics (e.g. immunisation, family planning and diabetic clin-

ics). Some practice nurses are also nurse practitioners who

perform many activities that are considered to be an extension

of traditional nursing roles. Nurse practitioners are educated

(usually to degree level) to diagnose and manage many basic

conditions and to prescribe medications from the Nurse

Prescribers’ Formulary (NPF). Suitably qualified district nurses

and health visitors also prescribe from the NPF.

— District nurses (DNs), who are also called community nurses,

are responsible for the nursing care provided for people in

their homes or in care homes. DNs are Registered Nurses (usu-

ally adult branch, although some are paediatric or learning dis-

ability nurses) who have undertaken additional education at a

university to obtain a degree in community nursing. A DN

usually supervises a small nursing team of staff nurses and

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

28

C3996_03.qxd 26/02/2004 13:45 Page 28

nursing assistants. Various health and social care professionals

may ask for a DN to assess a person in their home or a patient

may make a self-referral; similarly, a hospital may request that

a DN provide nursing care for a person following discharge

from hospital.

— Health visitors (HV) are Registered Nurses who have under-

gone further university nursing education in order to work in

the community and who specialise in health promotion, health

education and health maintenance. HVs do not deliver hands-

on nursing care. They concentrate on the welfare of small chil-

dren and mothers, but some HVs also work with older people

or groups with specific needs, such as refugees. In every geo-

graphical area there will be a designated HV who is responsi-

ble for children with special needs and those children who

may be at risk of being neglected or abused physically, men-

tally or sexually by their parents or carers.

— Community midwives provide professional care during preg-

nancy and labour and look after newly delivered mothers and

their babies in the community. Most babies are born in a

District General Hospital in the UK and in many areas com-

munity midwives accompany women into hospital to conduct

the delivery and take the woman and new baby home after a

few hours if all is well. Community midwives attend home

births, especially for women who have already had a child and

are expected to have a straightforward delivery. They also pro-

vide care for women who have been discharged following a

booked hospital delivery. In an uncomplicated delivery the

woman and baby are often discharged home to the care of the

community midwife within 12 hours.

— Community mental health nurses also work in the community,

but they specialise in the care of people with mental health

problems. They work with people in their own homes,

community-based mental health units, drugs and alcohol servi-

ces and the criminal justice system. They liaise with other

members of the PHCT, psychiatrists from local NHS Mental

Health Trusts, clinical psychologists and social workers.

THE NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE AND SOCIAL SERVICES

29

C3996_03.qxd 26/02/2004 13:45 Page 29

Other community health professionals

See Box 3.1 for an outline.

Ambulance Trusts

The Ambulance Service provides emergency care in the event of

serious illness or accident. Ambulance paramedics will stabilise

the person’s condition and then transport them to the most

appropriate emergency department (e.g. the local District

General Hospital). There is no charge for an emergency ambu-

lance, which is summoned by telephoning (999). You must ask

the operator for an ambulance, explaining as clearly as possible

the nature of the problem and the location. The Ambulance

Service itself is divided into emergency services and patient trans-

port services.

Secondary Care – NHS Acute Care Trusts

Secondary hospital care in the UK is delivered by NHS Trusts.

Acute care hospitals and some inpatient continuing care units

(e.g. for the care of older people) are part of NHS Trusts.

Hospitals are managed by a chief executive who is accountable

to the Executive Board of the Hospital Trust. Increasingly, the

management of hospitals is delegated to specific clinical direc-

torates within the Trust. Secondary care is provided in outpatient

departments, day case units and inpatient beds.

Nursing staff

Many nurses wear a uniform of some sort, which varies from hos-

pital to hospital and even within a hospital according to rank but

also according to nursing department. For example, paediatric

nurses often wear colourful tops and tabards, while those in

intensive care wear theatre tops and trousers, and mental health

nurses and senior nurses may wear their own clothes.

Within each Hospital Trust there will be a chief nurse (who

may be known as the nursing director, etc), who also sits on the

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

30

C3996_03.qxd 26/02/2004 13:45 Page 30

Trust board. The chief nurse provides professional nursing lead-

ership and is responsible for the overall implementation of nurs-

ing policies in a Trust and for the smooth running of the nursing

department.

THE NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE AND SOCIAL SERVICES

31

Box 3.1

Other health professionals working in the community

— Community pharmacists: most work within the NHS although they

are independent practitioners. A typical pharmacist on the high

street will have a working relationship with their local GP surgeries.

Medicines and surgical/nursing supplies written out on a GP's or

nurse's prescription form will be dispensed by the pharmacist. A

standard NHS prescription charge applies to each item, but most

people are exempt and do not pay for prescriptions.These include

children and pregnant women, people aged over 60 years, people

receiving certain social security benefits and people with certain

conditions (e.g. diabetes mellitus). Community pharmacists also

offer advice to the public about minor ailments and all aspects of

medication.

— Dentists are independent practitioners and some work with NHS

patients and provide services to patients at NHS rates. However,

there are few dentists who provide care under the NHS and currently

PCTs are employing more dentists to deliver NHS dental care.There

are several NHS dental hospitals in the UK, which provide for patients

with maxillofacial and dental problems.These hospitals also train and

provide practical placements for specialist personnel such as dental

nurses and speech and language therapists and of course dentists and

postgraduate dental surgeons.

— Opticians are also independent practitioners, but most work with NHS

patients and provide services to people at NHS rates. Some

optometrists and opticians work in NHS hospitals, but the majority

practise in the community. Certain groups of people do not pay for

eye care; these include pregnant women and children. People aged

over 60 years and those with conditions such as diabetes or glaucoma

are exempt from some charges.

C3996_03.qxd 26/02/2004 13:45 Page 31

Currently the nursing posts open to qualified Registered

Nurses are graded from D to I:

— A D grade staff nurse is considered the first nursing post that

a newly qualified nurse undertakes. A D grade post is really a

‘consolidation’ post, where the new nurse graduate consoli-

dates the training and education that he or she has received

before seeking promotion after a year or two. Initially, most

overseas trained nurses will be D grade until they become

used to nursing in the UK. However, depending on a nurse’s

previous experience and learning, he or she may be upgraded

very quickly.

— An E grade is for a more experienced staff nurse.

— A staff nurse is responsible to the F or G grade nurse known

as the ward sister/charge nurse (male) or ward manager.

Some hospitals use F grade for senior staff nurses, whereas

others use it for junior ward sisters/charge nurses. Apart from

staff nurses, ward sisters/charge nurses, healthcare assistants

and nursing students there will be senior nurses, clinical nurse

specialists, research nurses, lecturer–practitioners and nurse

consultants who are also employed by some PCTs.

— Senior nurses (G, H or I grade) usually have a managerial role

as well as responsibilities for a clinical speciality. Some senior

nurses have responsibility for several wards or units and they

are responsible to a general manager for organisational issues

and to the chief nurse for professional issues. Some senior

nurses have taken on the role of the modern ‘matron’, a post

that is intended to give mid-level nursing managers more

authority over hospital matters, and especially control over

issues such as the cleanliness of the hospital. There are many

clinical nurse specialists working in hospitals (and the com-

munity), especially in specialised areas such as pain control,

palliative care, stoma care and oncology. The nurse will have

undergone further education at a university and be a role

model for colleagues, acting as mentor and educationalist. The

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

32

C3996_03.qxd 26/02/2004 13:45 Page 32

lecturer–practitioner has a commitment to a student group at a

university, teaches and undertakes nursing research, in addi-

tion to the role of specialist nurse.

There is quite a difference between the pay of the D grade

nurse who is starting a career in nursing and a G or H grade

nurse. However, this pay arrangement is in the process of change,

as the government is piloting a new system of payment and

assessing workloads and work definition (Department of Health

1999) prior to its introduction nationwide. The new pay deal will

be beneficial to junior nurses, but to progress in the nursing

career structure it is necessary to undertake further training and

education (see Ch. 2).

Medical staff

Medical staff posts in hospitals are structured, with the post of

consultant (e.g. a nephrologist) being at the top of the clinical

speciality:

— Consultant: a physician or surgeon who has completed a

lengthy postgraduate specialisation.

— Associate specialist: an experienced doctor who is nominally

under the supervision of the consultant.

— Staff grade: a doctor who provides support for consultants.

— Specialist registrar: a doctor undertaking higher specialist

training.

— Senior house officer: a doctor undertaking basic specialist

training.

— House officer (pre-registration): a newly qualified doctor in the

year following qualification.

Surgeons in the UK are addressed as Mr or Mrs/Miss/Ms.

The introduction of European Union Working Directives has

reduced junior doctors’ hours and this has meant that some nurs-

es are trained to undertake some of the work traditionally done

by junior doctors.

THE NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE AND SOCIAL SERVICES

33

C3996_03.qxd 26/02/2004 13:45 Page 33

Professions allied to medicine and other staff

There are many other groups of professionals working in hospi-

tals (e.g. radiographers, technicians, medical scientists, physio-

therapists, speech and language therapists, play therapists, teach-

ers (in children’s hospitals) and social workers). You will also

encounter translators and healthcare advocates, who are bilingual

native speakers of various languages.

SOCIAL SERVICES

Social Services are provided by Local Authorities (local govern-

ment). For example, Norfolk County Council provides services for

the people who live in the county of Norfolk. Social Service

departments have a statutory responsibility to provide care for

groups that include:

— children and young people

— people with disabilities, including sensory impairments

— people who have problems with alcohol and drugs

— older people

— people with mental health problems.

Care and support is provided in the person’s own home or in

small community-based care units. People needing these services

will have a named social worker to co-ordinate and monitor the

care package. The care package may include help with personal

care, day centres, respite care and home modifications such as

bath rails and stair lifts.

As you advance in your UK nursing career you will have a

great deal of contact with social workers. Joint working between

health and social care professionals is vital for effective care plan-

ning and delivery. This is especially so in discharge planning, and

in the community where there is considerable overlap between

the work of health and social care professionals. In many areas,

such as mental health and children, health and Social Services

have formed a single Social Services & NHS Trust which aims to

provide high-quality care.

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

34

C3996_03.qxd 26/02/2004 13:45 Page 34

REFERENCES

Department of Health (DoH) 1999 Agenda for change. DoH,

London.

FURTHER READING AND RESOURCES

Clinical guidance, see the National Institute for Clinical

Excellence (NICE) website: www.nice.org.uk

Medicines and healthcare products, see the Medicines and

Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) website:

www.mhra.gov.uk

Public health (infection control, poisons, chemical and radiation

hazards), see the Health Protection Agency (HPA) website:

www.hpa.org.uk

THE NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE AND SOCIAL SERVICES

35

C3996_03.qxd 26/02/2004 13:45 Page 35

C3996_03.qxd 26/02/2004 13:45 Page 36

This page intentionally left blank

Nursing documentation,

record keeping and

written communication

INTRODUCTION

Accurate record keeping and careful documentation is an essen-

tial part of nursing practice. The Nursing and Midwifery Council

(NMC 2002) state that ‘good record keeping helps to protect the

welfare of patients and clients’ – which of course is a fundamental

aim for nurses everywhere. You can look at the full Guidelines

for records and record keeping by visiting the NMC website

(www.nmc-uk.org).

It is equally important that you can also communicate by letter

and e-mail with other health and social care professionals, to

ensure that they understand exactly what you mean.

NURSING DOCUMENTATION AND RECORD KEEPING

High quality record keeping will help you give skilled and safe

care wherever you are working. Registered Nurses have a legal

and professional duty of care (see Code of Professional Conduct,

Ch. 1). According to the Nursing and Midwifery Council guide-

lines (NMC 2002) your record keeping and documentation should

demonstrate:

— a full description of your assessment and the care planned and

given

— relevant information about your patient or client at any given

time and what you did in response to their needs

— that you have understood and fulfilled your duty of care, that

you have taken all reasonable steps to care for the patient or

37

4

C3996_04.qxd 26/02/2004 13:53 Page 37

client and that any of your actions or things you failed to do

have not compromised their safety in any way

— ‘a record of any arrangement you have made for the continu-

ing care of a patient or client’.

Investigations into complaints about care will look at and use

the patient/client documents and records as evidence, so high

quality record keeping is essential. The hospital or care home, the

NMC, a court of law or the Health Service Commissioner may

investigate the complaint, so it makes sense to get the records

right. A court of law will tend to assume that if care has not been

recorded then it has not been given.

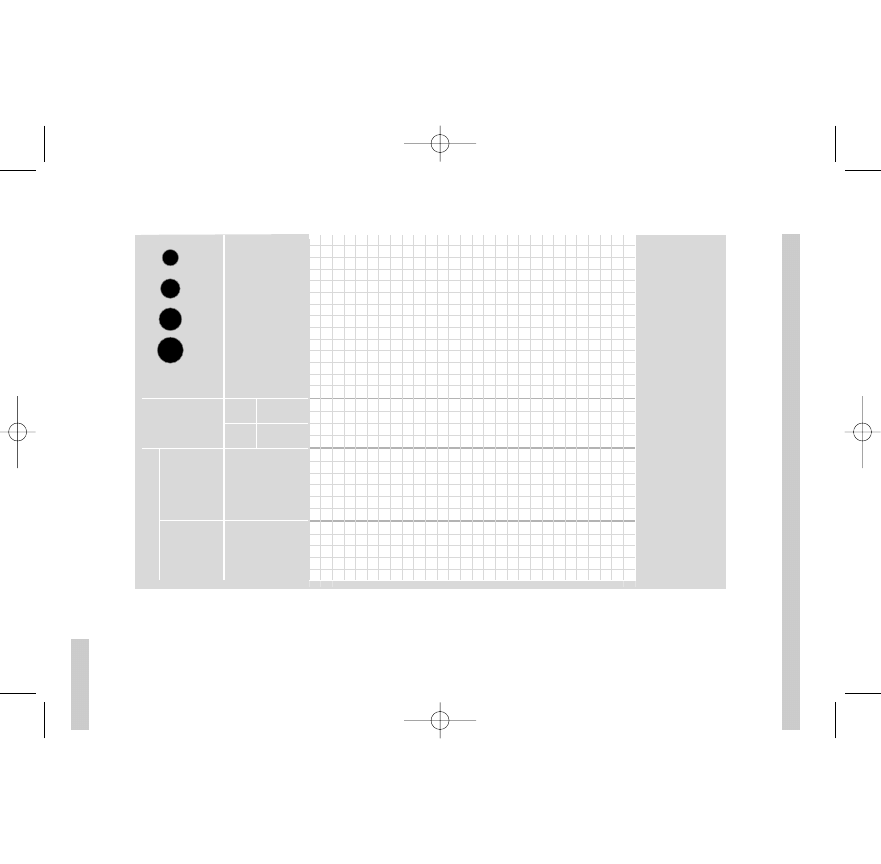

Documentation

You will see lots of different charts, forms and documentation.

Every hospital, care home and community nursing service will

have the same basic ones, but with small variations that work best

locally. The common documents that you will use include some

of the following.

Nursing assessment sheet

The nursing assessment sheet contains the patient’s biographical

details (e.g. name and age), the reason for admission, the nursing

needs and problems identified for the care plan, medication,

allergies and medical history.

Nursing care plan

The documents of the care plan will have space for:

— Patient/client needs and problems.

— Sometimes, nursing diagnoses will be documented but these

are not used as frequently as in North America.

— Planning to set care priorities and goals. Goal-setting should

follow the SMART system, i.e. the goal will be specific, meas-

urable, achievable and realistic, and time-oriented. For exam-

PARKINSON AND BROOKER: EVERYDAY ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL NURSES

38

C3996_04.qxd 26/02/2004 13:53 Page 38

ple, a SMART goal would be that ‘Mr Lee will be able to drink

1.5 L of fluid by 22.00 hours’. Some goals, such as reducing

anxiety, are not easily measured and it is usual to ask patients

to describe how they feel about a problem that was causing

anxiety.

— The care/nursing interventions needed to achieve the goals.

— An evaluation of progress and the review date. This might

include evaluation notes, continuation sheets and discharge

plans. In some care areas you might record progress using a

Kardex system along with the care plan.

— Reassessing patient/client needs and changing the care plan as

needed.

Vital signs

The basic chart is used to record temperature, pulse, respiration

and possibly blood pressure. Sometimes the patient’s blood pres-

sure is recorded on a separate chart. Basic charts may also have

space to record urinalysis, weight, bowel action and the 24-hour

totals for fluid intake and output. More complex charts, such as

neurological observation charts, are used for recording vital signs

plus other specific observations, which include the Glasgow

Coma Scale score for level of consciousness, pupil size and reac-

tion to light, and limb movement (Fig. 4.1).

Fluid balance chart

This is often called a ‘fluid intake and output chart’ or sometimes