Cross-Cultural Research / February 2000

Jankowiak, Ramsey / FEMME FATALE

Femme Fatale and

Status Fatale: A Cross-

Cultural Perspective

William Jankowiak

Angela Ramsey

University of Nevada–Las Vegas

This article presents the results of a cross-cultural survey of 78 cul-

tures that documented (through the use of folklore, ethnographic

accounts, and interviews with ethnographers) the presence or ab-

sence of a femme fatale (a dangerous woman), and a “status fatale”

(a dangerous man). We found that 94% of the cultures had images

of a femme fatale, whereas only 42% of the sampled cultures had

images of a status fatale. Our sample revealed that emotional in-

volvement, rather than sexual gratification, was the primary moti-

vation for becoming involved with a stranger who possessed quali-

ties deemed culturally most desirable in the opposite sex. The

significance of the findings is related to contemporary debates in

evolutionary psychology and cultural anthropology.

57

Authors’ Note: The following individuals assisted in the collection of the

data used in preparing this report: Teresa Bradley, Helen Spauling, Todd

White, and all the students in the 1997 Spring Honors seminar class taught

at UNLV. We thank Jim Bell, Carol Ember, Lee Monroe, Ray Hames,

Barry Hewlett, Holly Mathews, Eliot Oring, Gary Palmer, Paul Shapiro,

Elizabeth Whitt, and two anonymous reviewers for commenting on an ear-

lier version of this article. We especially would like to thank Melvin Ember

for his suggestions.

Cross-Cultural Research, Vol. 34 No. 1, February 2000 57-69

© 2000 Sage Publications, Inc.

A recurrent theme in the Old Testament, Western literature, tele-

vision, and film is the seductive female or femme fatale. From Bib-

lical sirens such as Delilah, Bathshaeba, and Salome, to more con-

temporary embodiments such as Marlene Dietrich (in the film,

Blue Angel), Joan Collins (Alexis of the television show Dynasty),

and Heather Locklear (Amanda of the television show Melrose

Place), the fatale prototype is portrayed as an active agent who

uses physical attractiveness, intelligence, and guile to dominate

and often destroy husbands and lovers. In contrast to the femme

fatale or dangerous woman motif, there is the male equivalent, or

“status fatale,” who relies less upon physical appearance and more

on displaying the markings of social success that disguise an evil

essence. Like the femme fatale character, the status fatale is a per-

vasive image in Western literature. From the historical Casanova,

to the mythic Don Juan, to Hollywood’s remaking of the silent-film

version of the Dracula myth, leading male characters have been

portrayed as strangers who are attractive and in possession of the

markings that signify social distinction. The main purpose of this

article is to document the frequency of the fatale motif around the

world, based on our survey of 78 cultures. We also discuss the

asymmetry in the images—beauty in the female, status in the

male. Finally, we explore some of the correlates of the varying fa-

tale motifs.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Explanations for the dangerous woman, who may be old or

young, a neighbor or a stranger, range from structural (Collier &

Rosaldo, 1981; Hays, 1988; Herdt, 1981; Ortner, 1978) to psycho-

analytical (Barnouw, 1985; Lipset, 1997) to evolutionary (Smuts,

1992). However, no one has explored whether there is a corre-

sponding image of the dangerous male (or status fatale), or docu-

mented the frequency in which the fatale motif is found around the

world. Given the lack of research, it is difficult to determine

whether a particular motif is restricted to a given region, linked to

a culture’s social complexity, or representative of a cultural or

human universal. Moreover, most of this theoretically driven

analysis focuses almost exclusively on the cultural meaning of the

dangerous woman motif, while ignoring the theoretical implica-

tions of the dangerous man motif.

58

Cross-Cultural Research / February 2000

Cultural explanations for the notion of the dangerous woman

have sought to explore male anxiety within an analytical frame-

work that assumes (without documentation) that male anxiety

and hostility toward women is a cultural universal, the intensity of

which varies depending upon a society’s degree of complexity. Ort-

ner (1978) aptly summarizes this perspective when she notes that

in egalitarian societies “women are generally considered danger-

ous to men, but in state-level [more socially stratified] societies,

they are said to be in danger from men, which justifies male protec-

tion and guardianship” (p. 27). Ortner does not elaborate upon the

source of the danger; the implication is that in egalitarian societies

the danger arises out of generalized fears of female sexuality,

whereas in more stratified societies the notion of the dangerous

woman reflects the importance of protecting family honor via the

control and regulation of female behavior (Ortner, 1981). Concur-

ring, Collier and Rosaldo (1981) believe that the origins of the dan-

gerous woman arose out of male-male sexual competition that

threatened male solidarity. Their model of the dominant—albeit

anxious—male holds that women’s sexuality makes them a source

of danger to men in two respects: (a) as a source of cuckoldry and

(b) as a source of male temptation to adultery that in turn threat-

ens male solidarity by creating conflict between men (Smuts,

1992, p. 25).

Smuts (1992) sought to synthesize Ortner’s (1978) cultural posi-

tion by combining it with an evolutionary framework that empha-

sizes the differential survival and reproductive strategies of males

and females (Buss, 1992; Symons, 1979; Townsend, 1998). Smuts

believes that male sexual anxiety, and thus the cultural projection

of fear of the dangerous woman, arises from sex differences in male

and female reproductive interests and the strategies used to

achieve those interests. In these societies, she adds, “women are

often portrayed as dangerous and polluting, and it is their sexual-

ity that makes it so” (Smuts, 1992, p. 25). Although neither Smuts

nor Ortner comments upon whether women may have related

anxieties about men’s behavior, we suspect they would agree that

women are also capable of similar cultural projections toward men.

In this way, gender anxiety is pan-human. By the same token, nei-

ther the cultural model nor the evolutionary model as presently

developed explores other possible motivations that may account

for the pervasiveness of male and female anxiety toward the oppo-

site sex.

Jankowiak, Ramsey / FEMME FATALE

59

From an evolutionary psychological perspective, it is assumed

that men desire nubile, physically attractive women, whereas

women prefer men who will obtain or have obtained some level of

social distinction (Buss, 1992; Symons, 1979; Townsend, 1998). If

the sex differences found in mate-selection criteria are manifesta-

tions of underlying erotic differences, it would follow that there

may be underlying concerns about being emotionally manipu-

lated, publicly humiliated, or physically harmed by what one most

desires in the opposite sex.

METHOD

We drew our data primarily from Murdock and White’s (1969)

standard cross-cultural sample (SCCS) of 186 societies, supple-

menting it where necessary with more recent ethnographic (e.g.,

Chagnon, 1992; Gregor, 1985; Lindholm, 1982; Tuzin, 1994) and his-

torical (e.g., Bascom, 1975; McLaren, 1994) sources. Because few

ethnographers comment upon the dangerous woman or male motif,

we relied almost entirely upon folklore to document the presence

or absence of femme fatale or status fatale in a given culture. We

did not sample, but rather read every available story.

Because many ethnographies did not explore a culture’s emo-

tional domain, the information on deep-seated anxieties and suspi-

cions is often thin or nonexistent for a given society. We therefore

relied on folklore, often collected by nonanthropologists, as our pri-

mary way to document the presence or absence of underlying fears

and misgivings toward the opposite sex (Cohen, 1990; McClelland,

1961). In addition, folktales are often morality tales that “motivate

behavior both because they are consciously employed in natural

settings to enjoin people to avoid certain dire consequences, and

because they show how ordinary actors may plausibly lead to the

very consequences they enjoin” (Mathews, 1992, p. 159). They con-

stitute, therefore, a rich source for documenting the prevalence of a

particular cultural theme.

We decided to rely upon folklore collections as our primary,

albeit not exclusive, means to document a culture’s awareness and

response to the dangerous woman/dangerous man image. We found

that the quantity of tales varied greatly between cultural areas.

For instance, the cultural areas of the Mediterranean, North Amer-

ica, South America, and East Asia have the most comprehensive

60

Cross-Cultural Research / February 2000

folklore collections. The Insular Pacific and sub-Saharan African

cultural areas, on the other hand, have the least comprehensive

collections. This presented problems with our sample. It would

have been ideal if every sampled culture had a comprehensive folk-

lore collection. From a data source of that size, we could have read-

ily determined whether a particular motif was truly present or

absent. However, this was seldom the case. Many cultures, espe-

cially those in the Insular Pacific and sub-Saharan Africa, often

had no more than five available folklore tales. Rather than drop

them from the sample, which would have meant dropping an addi-

tional 21 cultures, we decided to include in our sample any culture

that had at least one fatale motif. Significantly, in only 2 of the 21

cultures that had five or less tales did we fail to find evidence of a

fatale motif. In contrast, in only 3 (e.g., Utes, Ge, and Black Carib)

of 55 cultures that had 100 or more tales did we find no fatale motif.

Whenever possible, an ethnographer who had worked with a

sample population was questioned about the presence or absence

of stories, proverbs, or folk understandings describing the femme

fatale or status fatale motif. Some of these people were contacted

by phone (e.g., Thomas Gregor, personal communication, 1997;

Philip Kilbride, personal communication, 1997; Charles Lindholm,

personal communication, 1997), some by e-mail (e.g., Barry Hew-

lett, personal communication, March, 1997), and some were inter-

viewed at a professional meeting (e.g., Richard Lee, personal com-

munication, 1997; Nancy Mullenix, personal communication,

1997; Gary Palmer, personal communication, 1997; Helen Regis,

personal communication, 1997). Utilizing these outside sources, we

were able to expand our sample to 78 societies.

Definition of Fatale and Its Attributes

We assumed that cultures value physical attractiveness and

social distinction and thus have stories noting positive outcomes

arising from encountering individuals who possessed these

desired attributes. What we wanted to determine was whether any

cultures caution against an individual indiscriminately pursuing

someone who has these admired attributes. The femme fatale or

dangerous woman motif was coded as present if the tale implicitly

or explicitly noted that someone suffered in some way due to

involvement with a physically attractive female. A male beauty

fatale was coded as present if suffering resulted from contact with

Jankowiak, Ramsey / FEMME FATALE

61

a physically attractive male. The tale was considered to have a

status fatale motif if it noted that someone suffered as a result of

his or her involvement with a person of social distinction.

In addition to examining the universality of the femme fatale

and status fatale motif, we also wanted to test the Ortner (1978)

and Smuts (1992) hypothesis that the manifestation of the danger-

ous woman motif varies by the degree of social stratification. We

therefore clustered our sample into two categories: egalitarian and

stratified. If the stratification hypothesis is correct, we should find

more femme fatales in egalitarian societies than in stratified socie-

ties, and we should find fewer status fatales in egalitarian than in

stratified societies. Societies were classified as egalitarian if all

persons of a given age or sex category had equal access to economic

resources, power, and prestige, whereas they were classified as

stratified if there was unequal access to status positions and

prestige.

The motivation for becoming involved with a stranger was coded

as sexual, romantic, or both. Sexual desire was coded as present if

the encounter was brief and did not result in a long-term associa-

tion. Love was coded as present if the encounter resulted in mar-

riage, some form of long-term association, or the presence of a deep

attachment was noted. If the story noted the presence of sex and

love together, we coded both motivations as present. If the tale did

not mention love or sex, or was unclear about duration, it was

coded as not clear.

Coding reliability was ensured by having two graduate students

independently read the accounts and record whether the context

illustrated a person’s humiliation or death due to contact with

either an attractive or prestigious woman or man. Discrepancies

were reanalyzed and recorded; in three instances, consensus could

not be established through discussion, and the sample society was

dropped from the study.

DISCUSSION

The femme fatale motif was nearly universal in the cultures

examined (73 out of 78 cultures, or 94%), much more common than

the male beauty fatale (n = 20 out of 78, or 26%), and the status

fatale (n = 25 out of 50 cultures, or 50%). We did not find a single

story that dealt with a female status fatale.

62

Cross-Cultural Research / February 2000

Overall, we found that all the fatales are clustered around a per-

sona that embodies what, from an evolutionary perspective

(Symons, 1979), is presumably the most erotically desirable in the

opposite sex. For men, it is physical attractiveness, and for women,

it is evidence of social standing. In addition, the fatale characters

are overwhelmingly active agents of manipulation. This is consis-

tent with Smuts’s (1992) suggestion that the dangerous woman or

femme fatale motif stems less from societal factors and more from

underlying bio-psychological proclivities that are muted or inten-

sified depending upon the social context.

To provide a more revealing illustration of our findings, eight

ethnographic examples are presented below to highlight the anxi-

ety, romantic expectations, and conflict that are recurrent themes

in the fatale folktales. Indigenous representations of femme fatale

can be found in the first four examples.

1.

The pursuit of a beautiful woman may result in serious problems

that range from humiliation to death. In the Southern Nigeria Ibo

tale, “A Pretty Stranger Who Killed A King,” a man falls for a strik-

ingly pretty woman who is really a witch in disguise; after falling

asleep she cuts off his head (Bascom, 1975, p. 33).

2.

In South America, among the Mocovi Indians, there are numerous

“Fox as Trickster” tales that deal with a fox who transforms itself

into a woman for the sake of seduction. The man who is the object of

the seduction and/or other characters who serve as obstacles to the

seduction (object’s wife, parents, etc.) are often destroyed by the

fox/woman (Wilbert & Simonean, 1988, pp. 160-161).

3.

The Australian Aborigines believe that there are spirits who live in

the water who can assume the shape of a pretty woman “who will

sing all day and night sweetheart songs as they lay on rock places

like the crocodile do in cold weather time. . . . [It is assumed that

once a man hears their magic-songs], he must go to that water-girl

who will hold him with her finger like crab till him dead” (Harney,

1959, p. 40).

4.

The male anxiety over wanting yet fearing that which they desire is

a familiar theme in Chinese literature. There are many well-known

and popular stories involving a fox fairy or spirit (hulijin) who

takes the form of a beautiful woman in order to seduce and then kill

her lover. Chinese young men often tease one another that a par-

ticularly beautiful woman might be a fox fairy. As such, these sto-

ries constitute cautionary tales that remind men that beautiful

women can be potentially dangerous (Jankowiak, 1993, p. 183).

5.

The image of the male beauty and status fatale is illustrated in the

Dinka tale, “Ngor and the Girls.” Ngor, who is extremely handsome

Jankowiak, Ramsey / FEMME FATALE

63

as well as skilled in dancing and ritual chanting, attracts girls so

strongly that they impose themselves on him, dance with him,

accompany him, and sleep with him. In the end, he eats them all,

leaving only their heads (Deng, 1974, p. 168).

6.

The combination of the male beauty and status fatale is found in

the Southern Nigerian Hausa story, “The Disobedient Daughter

Who Married A Skull.” In the tale, a young woman is frightened

and publicly humiliated when she is attracted to a very handsome

stranger who turns out to be a being from the spirit world who

wants to eat her (Bascom, 1975, p. 59).

7.

A representation of intentional trickery sometimes used by a status

fatale is found in the Hindu tale, “Shall I Show You My Real Face?”

In the tale, a tiger takes the shape of a learned and respected Brah-

man who is able to marry villagers’ daughters who are impressed

with his knowledge. In the end, these girls are humiliated after

their offspring turns out to be tiger cubs (Ramanujan, 1991).

8.

Another example of a status fatale is found in the Eskimo tale of the

“Raven Who Married the Arrogant Girl Who Refused Men.” In this

story, a young, attractive girl suffers when she chooses to follow her

own romantic inclinations and ignore the advice of her parents.

After stubbornly refusing various marriage proposals by her

numerous suitors, she meets a well-dressed stranger bearing gifts

and accepts his offer to marry. She quickly is plunged into despair,

however, when she discovers that her husband is not a human

being, but a raven who lives high up on a rock. Amidst sobs, she

runs away from her husband, and it is said that since the experi-

ence she has lost her arrogance and has married the first man who

came to the settlement asking for her (Boas, 1964, pp. 157-158).

Although our data lend some validation to our theoretical

“Smuts-Ortner model,” it is noteworthy that the “man as sexual

predator” theme is not more pervasive in our sample findings. As

noted, only 25 out of 50, or 50%, of complex societies have stories

involving a status fatale. Perhaps the status fatale stories reflect

less the concerns of a senior generation’s attempts at socialization

and more the individual’s fear of being misled by blindly following

his or her impulses.

Men, due perhaps to their ability to idealize physical attractive-

ness, are much quicker to become involved with a stranger who is

attractive. Thus, 20 out of 78, or 26% of the femme fatale stories

involve encounters with women who are unaware of (or indifferent

to) a male’s interest (see Table 1). From an evolutionary perspec-

tive, this may reflect an underlying sex difference in how men and

women respond to an encounter with an unfamiliar member of the

64

Cross-Cultural Research / February 2000

opposite sex.

1

The literature notes that for females, the dominant

response to an unfamiliar male is an assessment of threat or dan-

ger (Linder, Lewis, & Kenrick, 1995), whereas the more typical

response for males to an unfamiliar female is an increase in sexual

attraction (Allen, Kenrick, Linder, & McCall, 1989; Dutton & Aron,

1974; Kenrick & Johnson, 1979). This sex difference may account

for the scarcity of the passive agent (or unintentional fatale; n = 2

out of 33, or 6%) compared to the active agent (or intentional status

fatale; n = 31 out of 33, or 94%). If the male becomes injured in his

pursuit of the woman, it is entirely due to his blind obsession, and

not her manipulation. In contrast, there are only two cases in which

a woman blindly pursues a male beauty or status fatale, reinforc-

ing the notion of a different sexual aesthetic for men and women.

Sex-linked criteria may also account for the relative infre-

quency of folktales portraying men as pursued solely for their

physical appearance. If we compare egalitarian and state-level

societies, we find that only 25% (7 out of 28) of the egalitarian socie-

ties and 26% (13 out of 50) of the state-level societies are concerned

with the dangers of becoming involved with a good-looking

stranger. However, the occurrence of a male beauty fatale (n = 18

out of 20, or 90%) appears to be localized and restricted primarily

to tropical environments, with 16 of the tales found in sub-Saharan

Africa. Physical attractiveness in this context may represent

something other than a desire for physical attractiveness in and of

Jankowiak, Ramsey / FEMME FATALE

65

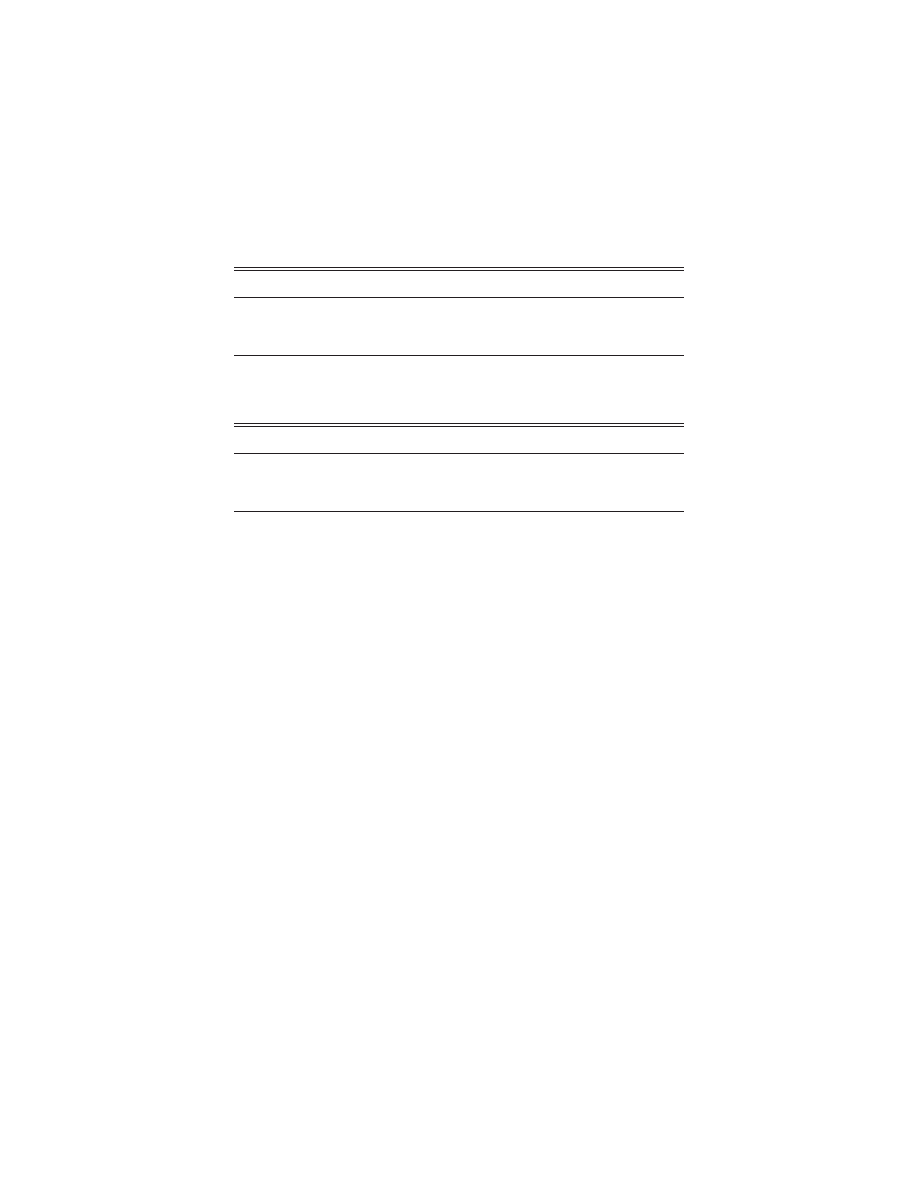

TABLE 1

Status Fatale and Social Complexity

n

%

Egalitarian

7 of 28

25

Complex

25 of 50

50

Total

33 of 78

42

TABLE 2

Male Beauty Fatale

n

%

Egalitarian

7 of 28

25

Complex

13 of 50

26

Total

20 of 78

25.6

itself. In these regions, symmetrical appearance and healthy skin

tone imply good health. Perhaps a “good looking” man in the trop-

ics, where there is a higher occurrence of parasitic infections, is

representative of good health or, in this context, a status object.

Here, physical attractiveness is an index of social well being. On

the other hand, the relative absence of male beauty fatale stories

(n = 2) in other tropical environments, suggests that this type of

fatale is restricted to sub-Saharan culture, and thus should be

regarded as an artifact of culture and not biology (Barry Hewlett,

personal communication, March, 1997).

The Smuts-Ortner model suggest that the origins of male anxi-

ety toward women stem from the desire to control female sexual

behavior. However, if you look at the motives attributed in the sto-

ries for a person’s involvement with a stranger of the opposite sex,

54 out of 60 (90%) of the stories (where the motivation could be

determined) involve emotional involvement beyond sexual gratifi-

cation.

3

This finding suggests that the origins of the cultural pro-

jection of the femme fatale may reflect a fear of becoming emotion-

ally damaged rather than just a fear of inappropriate sexual or

social encounters. Moreover, this finding is consistent with the

research on the pervasiveness of romantic love cross-culturally

(Jankowiak & Fisher, 1992) that found evidence of romantic pas-

sion in 89.5% of all sample cultures.

The low number of stories (n = 6) that name the pursuit of sexual

gratification as the primary reason for involvement could repre-

sent a translation bias or self-censorship on the part of the story-

tellers. However, the same thing could be said about love stories. It

is significant that given this bias, there are more love stories than

sex stories. This would seem to indicate that the cautionary tales

are warnings against emotional attachments rather than against

unfortunate sexual acts (see Table 3).

CONCLUSION

Our findings reveal that the female seducer, and, to a lesser

extent, the male seducer, is found in folktales around the globe.

The seducers seem incapable of love or are portrayed as willfully

using the love experience to manipulate and dominate the lover.

Cultures recognize the horrific danger of such an encounter; there

are often tales that depict these encounters as leading to

66

Cross-Cultural Research / February 2000

destruction and chaos. By perpetuating these tales, cultures can

instruct their members how to avoid romantic manipulation and,

more importantly, how to recognize authentic human affection.

The Smuts-Ortner model of cultural complexity and sex-linked

reproductive strategies may account for the transformation in

men’s and women’s posturing toward the opposite sex, but they are

not sufficient to account for the origins of the underlying anxiety

that gives rise to the fatale tales found around the world. Whether

the concern is with physical beauty or social distinction, our study

shows that the predominant motive for becoming involved with

another is as much about emotional attachment as it is sexual ful-

fillment. Our study suggests that what human beings around the

world fear is the prospect of becoming emotionally involved with

someone who does not share or reciprocate their sentiments. At the

level of individual psychology, this suggests that the anxieties are

not unique to one gender, but rather are similar for both.

Notes

1. Ethnocentrism and the sexual encounter involve two different

processes. First, there is the fear of the stranger; second, there is a sexual

attraction to novelty, especially physical attractiveness (Don Brown, per-

sonal communication, June, 1997). For men, this may heighten the excite-

ment, whereas for women it may reduce it.

2. Anthropology texts often note that some cultures have a male-

castration complex. By not offering an alternative explanation, however,

it is often tacitly implied that the male fear of castration is cross-culturally

ubiquitous. Although we did not specifically look for tales of castration, it

is significant that out of 78 sample cultures, only 1, Yanomamo, dealt with

sexual castration (Chagnon, 1992). Our findings suggest that the male

castration complex, at least as it is manifested in a culture’s folklore, is a

localized rather than pan-human concern.

Jankowiak, Ramsey / FEMME FATALE

67

TABLE 3

Motives for Involvement

Sex

Love

Both

Not Clear

Femme fatale

3

16

19

34

Status fatale

3

6

13

11

Male beauty fatale

1

7

2

10

Total

7

29

24

55

References

Allen, J. B., Kenrick, D. T., Linder, D. E., & McCall, M. A. (1989, July).

Arousal and attraction: A response-facilitation alternative to misattri-

bution and negative reinforcement models. Paper presented at the Hu-

man Behavior and Evolution Conference, Santa Barbara, CA.

Barnouw, V. (1985). Culture and personality (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wad-

sworth.

Bascom, W. (1975). African dilemma tales. Chicago: Mouton Publishers;

The Hague Press.

Boas, F. (1964). The central Eskimo. Lincoln: University of Nebraska.

Buss, D. (1992). The evolution of desire. New York: Basic Books.

Chagnon, N. (1992). Yanomamo. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Cohen, A. (1990). A cross-cultural study of the effects of environmental un-

predictability on aggression in folktale. American Anthropologist, 92,

474-479.

Collier, J. F., & Rosaldo, M. Z. (1981). Politics and gender in simple socie-

ties. In S. B. Ortner & H. Whitehead (Eds.), Sexual meanings: The cul-

tural construction of gender and sexuality (pp. 275-329). Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

Deng, F. (1974). Dinka folktales. New York: Africana.

Dutton, D. G., & Aron, A. P. (1974). Some evidence for heightened sexual

attraction under conditions of high anxiety. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 30(4), 510-517.

Gregor, T. (1985). Anxious pleasures. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

Harney, B. (1959). Tales from the Aborigines. London: Robert Hale

Limited.

Hays, T. (1988). Myths of matriarchy and the sacred flute complex of the

Papua New Guinea highlands. In D. Gewertz (Ed.), Myths of matriarchy

reconsidered (pp. 98-119). Sydney, Australia: University of Sydney

Press.

Herdt, G. (1981). Guardians of the flutes. New York: McGraw Hill.

Jankowiak, W. (1993). Sex, death and hierarchy in a Chinese city. New

York: Columbia University Press.

Jankowiak, W., & Fisher, T. (1992). Cross-cultural perspective on roman-

tic love. Ethnology, 31, 149-156.

Kenrick, D. T., & Johnson, G. A. (1979). Interpersonal attraction in aver-

sive environments: A problem for the classical conditioning paradigm.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 572-579.

Linder, D., Lewis, B., & Kenrick, D. (1995, July). The arousal-attraction

relationship revisited: An evolutionary interpretation of empirical gen-

der differences. Paper presented at the Human Behavioral and Evolu-

tionary Society Meetings, Santa Barbara, CA.

Lindholm, C. (1982). Generosity and jealousy. New York: Columbia Uni-

versity Press.

Lipset, D. (1997). Mangrove man. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

68

Cross-Cultural Research / February 2000

Mathews, H. (1992). The directive force of morality tales in a Mexican

community. In R. d’Andrade and C. Strauss (Eds.), Human motives and

cultural models.

McClelland, D. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton, NJ: Van Nos-

trand.

McLaren, A. (1994). The Chinese femme fatale. Sydney, Australia: The

University of Sydney.

Murdock, G. P., & White, D. (1969). Standard cross-cultural sample. Eth-

nology, 8, 329-369.

Ortner, S. B. (1978). The virgin and the state. Feminist Studies, 4, 19-37.

Ortner, S. B. (1981). Gender and sexuality in hierarchical societies: The

case of Polynesia and some comparative implications. In S. B. Ortner &

H. Whitehead (Eds.), Sexual meanings: The cultural construction of

gender and sexuality (pp. 275-329). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Ramanujan, A. K. (1991). Folktales from India: A selection from twenty-

two languages. New York: Pantheon.

Smuts, B. (1992). Male aggression against women. Human Nature, 3(1),

1-44.

Symons, D. (1979). Human sexuality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Townsend, J. (1998). What women want—what men want. New York: Ox-

ford University Press.

Tuzin, D. (1994). The forgotten passion: Sexuality and anthropology in the

ages of Victorian Bronislaw. Journal of the History of Behavioral Sci-

ence, 9, 114-135.

Wilbert, J., & Simonean, K. (Eds.). (1988). Folk literature of the Mocovi In-

dians. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center Publications.

William Jankowiak is an associate professor of anthropology at the Uni-

versity of Nevada, Las Vegas. He received his Ph.D. from the University of

California, Santa Barbara. He has conducted extensive field research in

China, Inner Mongolia, and North America. He is the author of numerous

scientific publications, including Romantic Passion, (Columbia University

Press, 1996) and Sex, Death, and Hierarchy in a Chinese City, (Columbia

University Press, 1993). He is presently working on a book focusing on sac-

rifice and affection in a contemporary American polygamous community.

Angela Ramsey earned her master’s degree in anthropology at the Univer-

sity of Nevada, Las Vegas in 1998. She is presently rewriting for publica-

tion her master’s thesis; it explored how strippers use a type of performance

psychology to overcome culturally inspired inhibitions.

Jankowiak, Ramsey / FEMME FATALE

69

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

10 M3 JankowskiM MuszyńskiA ZAD10

samosprawdzenie, pedagogika uczelnia warszawaka, podstawy psychologii ogólnej, wykłady Maria Jankows

Psychologia ogólna - ćwiczenia , Szkoła - studia UAM, Psychologia ogólna, Konwersatorium dr Barbara

NOWY JANKOW 5 DZIALKI id 323922

Projekt oczyszczalni sciekow Lukasz Jankowsk-Kate made, Technologia Wody i Ścieków

jankowe przepisywanie

Obrobka skrawaniem egzamin jankowiak

PROJEKTOWANIE BELKI270, Skrypty, PK - materiały ze studiów, I stopień, SEMESTR 7, Konstrukcje stalow

22 jankowiak1

NOWY JANKÓW 5 PLAN Z OBIEKTAMI

NOWY JANKÓW 5 DO DRUKU(1)

Jankowski- pytania na egzamin dyplomowy, PEDAGOGIKA, egzamin dyplomowy ogólne

NOWY JANKÓW 5, DO DRUKU

NOWY JANKÓW 5 PLAN

vetrenoe serdce femme fatale

Rozrywkowy biznes prałata Jankowskiego

Instr. nowy typ-Jankowice, Instrukcje w wersji elektronicznej

Definicja i przedmiot psychologii, pedagogika uczelnia warszawaka, podstawy psychologii ogólnej, wyk

Zadania Materialy na ćwiczenia- rachunkowość mgr Edyta kamont jankowska collegium mazovia, Szkoła, R

więcej podobnych podstron