Published by Soundview Executive Book Summaries, 10 LaCrue Avenue, Concordville, Pennsylvania 19331 USA

©2001 Soundview Executive Book Summaries • All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or part is prohibited.

How to Translate Project Decisions into

Business Success

THE PROJECT

MANAGER’S MBA

THE SUMMARY IN BRIEF

Finishing a project on time and on budget is no longer a project manag-

er’s sole criteria for success, according to authors Dennis J. Cohen and

Robert J. Graham. You are also held accountable for your contributions to

the company’s financial goals. As a project manager, however, you may not

have the business knowledge necessary to make project-based decisions that

lead to bottom-line success.

This summary presents the skills and knowledge you need to link project

success to organizational success. Specifically, you will learn how to:

✓

Take an entrepreneurial approach to managing projects. You will

learn to view each project in light of its contribution to the overall prof-

itability of the company and begin to run projects as if they were business

start-ups.

✓

Understand the basics of accounting and finance. You need to

understand the basics of balance sheets and profit and loss statements and

know how to adapt them to measure the impact of your project on the com-

pany’s profitability.

✓

Understand business strategy. Your projects must be compatible

with your company’s overall business strategy, whether that strategy is to

deliver world class service, provide leading-edge technology, or deliver

operational excellence.

✓

Manage projects for maximum results. You will see what methods

you should use to speed up the project.

✓

Understand the customer. Every project must be designed with

what the customer and end-user want and need to solve a problem.

✓

Calculate project costs and measure project success. You will

soon see exactly what costs must be considered when setting up a project.

You will learn to measure and apply the direct and indirect costs your com-

pany invests in your project. You will also learn how to determine the life

cycle of the end product of the project, and measure the value

created by the project against the cost of producing it.

Concentrated Knowledge

™

for the Busy Executive • www.summary.com

Vol. 23, No. 5 (3 parts) Part 2, May 2001 • Order # 23-12

CONTENTS

An Entrepreneurial Approach

To Managing Projects

Pages 2, 3

Accounting and Finance:

You Must Know the Basics

Pages 3, 4

Corporate Strategy:

It’s Your Business, Too

Page 4

Increase Speed, Quality and

Value of Projects

Page 5

Understand the Customer

and the Competition

Pages 5, 6, 7

Calculate the Project Costs

Pages 7, 8

Why Finance Matters

for Project Managers

Page 8

The Project Venture

Development Process

Page 8

By Dennis J. Cohen and

Robert J. Graham

FILE:

Hands-On Mana

g

ement

®

An Entrepreneurial Approach

To Managing Projects

“Make it fast. Make it good. Make it cheap.” So goes

the project management folklore about what senior

managers always ask for. Traditionally, project man-

agers would reply with, “Pick two.” And almost always,

“Make it cheap” is one of the two project goals chosen.

It might not be the right answer. When project man-

agement and senior management understand the wider

implications, they both realize that “make it cheap”

might not contribute to successful business results as

often as they think. More important than reducing the

costs of a project is increasing its value.

In other words, as a project manager you must devel-

op a framework for thinking about projects based on

business concepts such as increasing economic value,

or Economic Value Added (EVA).

A successful project, for example, might mean creat-

ing a high level of customer satisfaction, which produces

more sales, which, in turn, creates enough cash flow to

cover project and operating expenses, make a profit, and

pay back the cost of the capital used to produce the prod-

uct. At this point, the project begins to produce the eco-

nomic value known as shareholder value.

Creating shareholder value requires project managers

to act like entrepreneurs — treating projects like busi-

nesses — and think like CEOs — viewing each project

as part of a wider organization.

Act Like an Entrepreneur and Think Like a CEO

What does it mean to act like an entrepreneur and

think like a CEO?

First and foremost, it means understanding how

organizations create value for their stakeholders —

shareholders, customers and the business team. For

shareholders, the business creates value when it pro-

vides a rate of return that meets their expectations for

the level of risk they have taken. Cash flow is the fuel

for this satisfaction. It is up to the business team to

manage projects that deliver this necessary cash flow.

The problem is that many projects won’t directly

impact a company’s bottom line. Project managers also

need to consider the project’s overall impact on the

company’s strategy to see where the project creates

value. For example, new product projects often impact

profitability and create high levels of profit, while a

project that focuses on breaking into a new geographic

market might be lucky to break even. But both projects

contribute to the execution of the company’s overall

strategy.

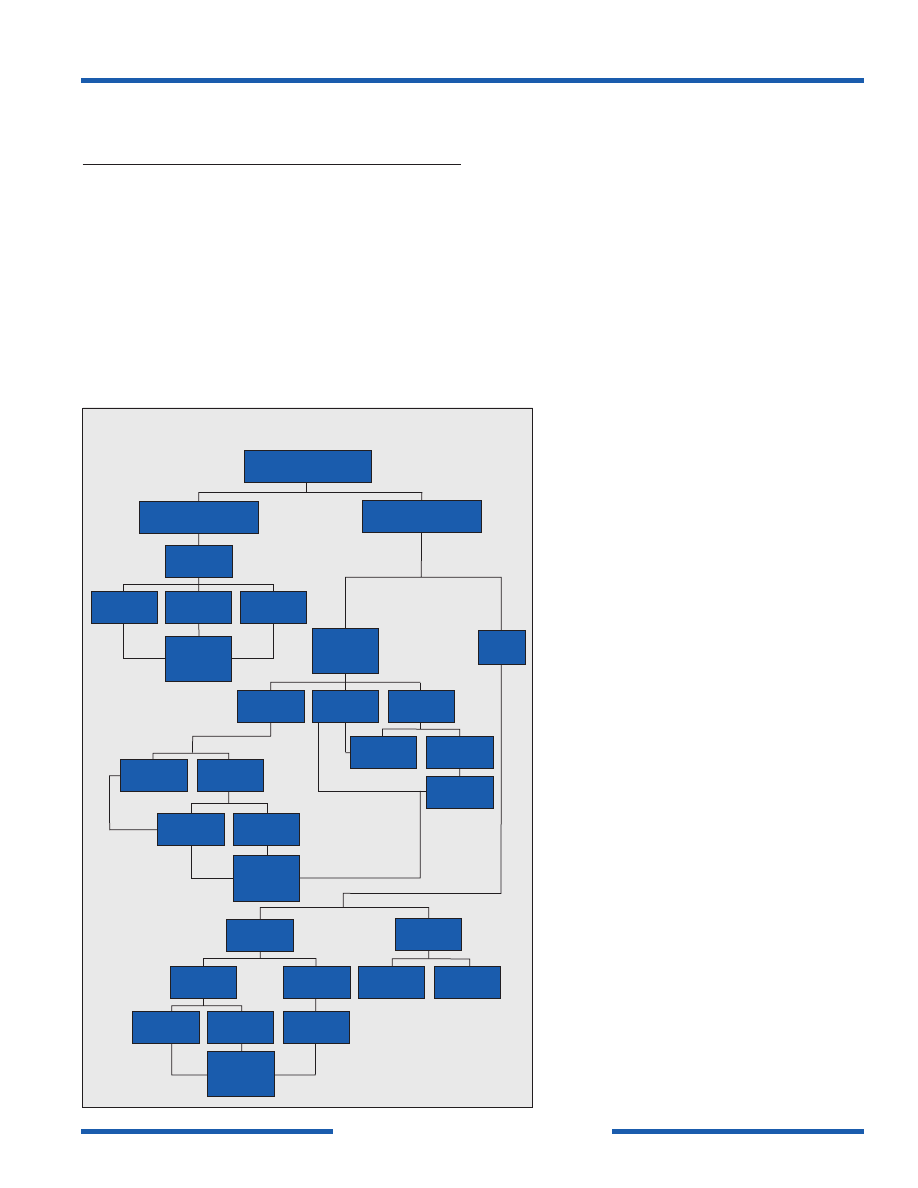

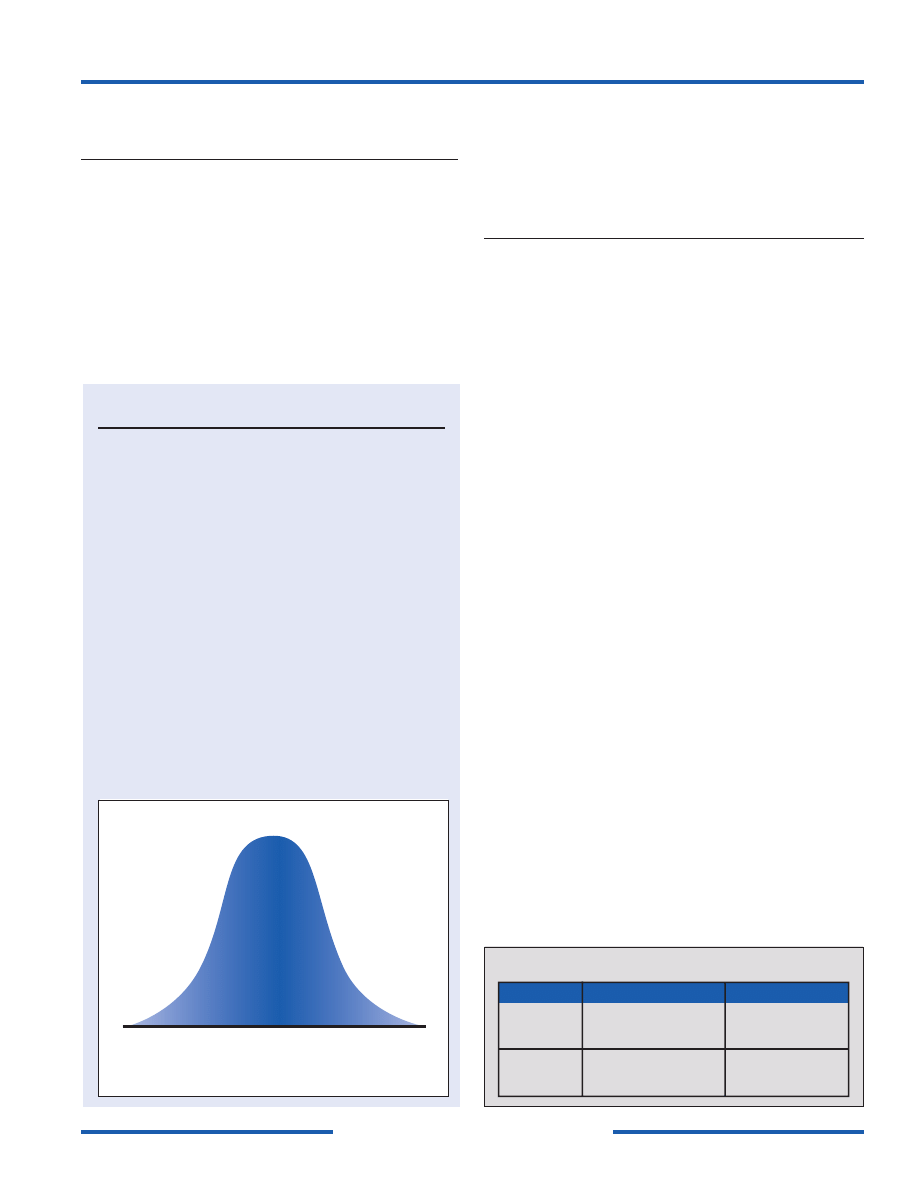

A project’s contribution to overall business success

can be diagrammed and looks something like the chart

on the next page.

At the top of the diagram is the ultimate goal: the pro-

ject’s contribution to business results. The boxes below

2

THE PROJECT MANAGER’S MBA

by Dennis J. Cohen and Robert J. Graham

—

THE COMPLETE SUMMARY

The authors: Dennis J. Cohen is senior vice presi-

dent and managing director of the Project Management

Practice at Strategic Management Group. Robert J.

Graham has developed a consulting practice in project

management and is the author of Project Management

as if People Mattered and Creating an Environment for

Successful Projects.

Copyright© 2001 by Jossey-Bass, Inc. Summarized

by permission of the publisher, Jossey-Bass, Inc., A

Wiley Company, 605 Third Avenue, New York, NY

10158-0012. 242 pages. $34.95. 0-7879-5256-7.

(continued on page 3)

Soundview Executive Book Summaries

®

To subscribe: Send your name and address to the address listed below or call us at 1-800-521-1227. (Outside the U.S. and Canada, 1-610-558-9495.)

To subscribe to the audio edition: Soundview now offers summaries in audio format. Call or write for details.

To buy multiple copies of this summary: Soundview offers discounts for quantity purchases of its summaries. Call or write for details.

Published by Soundview Executive Book Summaries (ISSN 0747-2196), 10 LaCrue Avenue, Concordville, PA 19331 USA, a division of Concentrated Knowledge

Corporation. Publisher, George Y. Clement. Publications Director, Maureen L. Solon. Editor-in-Chief, Christopher G. Murray. Published monthly. Subscription, $89.50 per

year in the United States and Canada; and, by airmail, $95 in Mexico, $139 to all other countries. Periodicals postage paid at Concordville, PA and additional offices.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Soundview, 10 LaCrue Avenue, Concordville, PA 19331. Copyright © 2001 by Soundview Executive Book Summaries.

Project Categories

Most organizations that engage in project planning

categorize these projects into three groups:

New product, service, or facility development

projects. These projects provide something entirely

new in the organization. These projects generate new

or greater income for the organization.

Internal projects. These projects involve infra-

structure development and improvement and include

reorganizations, reengineering, and other change ini-

tiatives as well as software and hardware initiatives.

These projects generally don’t produce new income.

Rather, they produce cost savings and create operat-

ing efficiencies.

Client engagement projects. These projects ben-

efit external customers or clients. Today, those

clients expect more than they ever expected before

and look for measures of increased economic value

as proof of success.

the goal represent the business factors that go into pro-

ducing economic value; the lines connecting the boxes

represent interactions among those factors. The left side

of the chart represents the strategic alignment of the proj-

ect with the company’s overall strategy. The right side

side shows the project’s contribution to economic value.

As you explore the flow chart, you will see that there

is a new project management paradigm developing.

Projects are conceived and executed with an understand-

ing of the dynamics of competition, timed for maximum

cash flow, and represent an investment in competitive

advantage. ■

Accounting and Finance:

You Must Know the Basics

In the past, when project managers were given a proj-

ect and a budget, they could afford to be ignorant of

accounting and finance basics. Not today. To link proj-

ect success to organizational success, project manage-

ment must understand at least the basics of finance and

accounting. This article reviews some of the basics.

Cash Cycle

Each company has a cash cycle. The cycle involves

acquiring cash, using that cash to grow and to operate,

and returning any cash necessary to the creditors and

owners. For example, a company’s cycle begins with a

financing phase where the company must attract funds

from financial institutions and investors to have

the capital needed to start the business. It then

invests the funds in labor and equipment

required to develop the business (the investing

phase.) In the operating phase, the company

uses the funds to operate and adds funds gener-

ated by the business to the pot. Finally, in the

returning phase, creditors and investors are

paid. This is their return on investment.

Projects are just like start-up businesses, fol-

lowing the same cash cycle.

Financial Reports

Financial reports are required of all companies

of any significant size. A company’s financial

reports consists of at least three basic statements:

a balance sheet, an income statement and a cash

flow statement. Each serves a vital function.

A company’s balance sheet shows its assets

and its liabilities. Assets, shown on the left side

of the balance sheet, come in two kinds: cur-

rent assets, which will be converted into cash

in the next year or so, and long-term assets.

The right hand side of the balance sheet tracks

short-term and long-term liabilities as well as a

liability called shareholder’s equity.

Shareholder’s equity consists of stock and

retained earnings, which are profits that could

have been distributed to shareholders as divi-

dends but were kept by the company.

The sheet is called a balance sheet because

the left hand side always equals the right hand

side, and can be represented by the basic

accounting formula: Assets = Liabilities +

Shareholder’s Equity.

A company’s income statement attempts to

match revenues with the expenses associated

3

The Project Manager’s MBA —

SUMMARY

Soundview Executive Book Summaries

®

An Entrepreneurial Approach

to Managing Projects

(continued from page 2)

(continued on page 4)

Business Systems Diagram

PROJECT CONTRIBUTION

TO BUSINESS RESULTS

Project

Cost

Project

Outcome

Cash Flow

from Project

Enterprise

Project Contribution to

Business Strategy

Strategic

Alignment

Project

Duration

Project

Management

Practices

Project Contribution to

Economic Value EVA

Capital

Charge

Depreciation

Operating

Expenses

Project

Cost

Project

Outcome

POL

Revenue

Price

Market Share

(Volume)

Project

Duration

Project

Outcome

WACC

Capital

POL

Expenses

Investor’s

Expectation

Lender’s

Expectation

POL Use

of Capital

Project Use

of Capital

Project

Outcome

Project

Duration

Project

Cost

Project

Management

Practices

Project

Management

Practices

with those revenues. A company’s revenue minus its

expenses equals its net income. If the net income is posi-

tive, the company has made a profit. If it is negative, the

company has suffered a loss. That’s why the income

statement is also referred to as a profit and loss state-

ment. Income statements are important for project man-

agers because they match the cost of the project with the

revenue or cost savings produced by the project.

A cash flow statement completes the basic financial

statements. It tells someone examining the company

from the outside where cash needed to run the business

has come from and where it has gone. Internally, man-

agement can use the cash flow statement to see how

much cash is free for use in the business. This free cash

flow is the net cash generated by the operations of the

business minus the cash used for investment activities.

If free cash flow is positive, the company does not need

to obtain additional investments; if it is negative, the

company must find additional investments in either

stock or bank financing to continue operations. ■

Corporate Strategy:

It’s Your Business, Too

All organizations have a strategy, explicit or implied,

that upper management uses to guide decision-making.

In the past, top management acted as if strategic plan-

ning was a ritual rain dance. Every year a strategic plan-

ning process took place, with each upper manager

scouting out threats and opportunities. These were then

analyzed and became part of the strategic plan to be

locked in a drawer until next year.

Today, change is happening too fast to rely on old

methods of strategic planning. Now strategic plans must

change as rapidly as your company’s environment

changes — which means everyone at the company must

be aware of the strategic plan and take part in it. Project

managers must understand their company’s strategy and

how their projects fit into it.

In its most basic form, strategy is the way a company

orients itself toward the market in which it operates, and

toward other companies in that market. Strategy

answers the question of how the company will position

itself in the market over the long run to secure a sustain-

able competitive advantage.

Most project managers are too involved in the day-to-

day management of their projects to pay much attention

to that strategy. This is a mistake. Project managers

need to align their projects with the strategic choices

made by the company.

For example, if the company chooses to emphasize

product leadership, projects to develop new products

will focus on innovation and speed, not customer serv-

ice. If project managers don’t buy into or understand

company strategy, they might run the project with a

focus inappropriate to the company’s strategy and thus

miss making a significant contribution to the execution

of that strategy and the creation of economic value. ■

4

The Project Manager’s MBA —

SUMMARY

Soundview Executive Book Summaries

®

Accounting and Finance:

You Must Know the Basics

(continued from page 3)

Why Project Managers Need to

Understand Strategy

✓

Management is evaluating project managers on

how well they implement company strategy.

✓

Understanding company strategy will let you make

decisions during the project that match strategy. If

the strategy is to be first to market, that’s how you

will manage your project, for example.

✓

Understanding your company’s strategy will help

you develop a team with common goals.

✓

Aligning your project with company strategy will

help protect it from being canceled, since you can

demonstrate the project’s importance and rele-

vance. And if the project does not match company

strategy, you can understand why it is cancelled.

✓

Understanding strategy lets your project stay

focused and on track.

Approaches to Company Strategy

Below are three basic approaches a company can

take to developing a sustained competitive advantage.

Choose one as your company’s strategic focus, but

make sure that your practices in the other two at least

meet the industry average.

Customer Intimacy: Companies who choose this

strategic focus aim to develop long-term relationships

with their customers. Customers expect the best serv-

ice and get it. Examples of companies taking this tack

are Nordstrom’s and Home Depot.

Operational Excellence: Other companies build

their strategies around high efficiency and high vol-

ume. For example, a McDonald’s anywhere in the

world is likely to be virtually identical to other loca-

tions. Customers expect it, and McDonald’s delivers.

Product Leadership: Companies that practice prod-

uct leadership must be creative because they are tar-

geting the segment of the population that consists of

early adopters. These want the latest and best prod-

ucts and are willing to pay for them.

Increase Speed, Quality

and Value of Projects

Project cycle time, or how long it takes a project to go

from idea to completion, is crucial. Proper project man-

agement practices will shorten that time.

The sooner the project is completed, the sooner it can

begin to produce its value and begin to pay back the

investment used to produce it. Thus, reduced cycle time

adds to cash flow, reduces the project’s capital require-

ments, and increases economic value. Don’t reduce

cycle time by increasing manpower and working people

overtime until they drop (a common method). A better

approach is to increase the budget for good management

practices.

How to Reduce Cycle Time

The following six practices will decrease the duration

of a project, increase quality and decrease total costs:

1. Have one well-trained project manager. He or

she should be enthusiastic and trained to manage proj-

ects. Don’t appoint someone just because of technical

expertise or availability. The designated project manager

is the only person the team reports to; team members

must know that he or she has the authority to make

decisions and direct the project.

2. Develop a rapid prototyping process. Prototypes

need to be developed quickly, even if they are not per-

fect. Presenting imperfect prototypes helps highlight

problems and facilitates solutions to those problems.

Customers have an opportunity to look at prototypes and

offer suggestions for improvement. Today, prototypes are

not specifications driven. Instead, prototypes drive specs.

3. Establish a core team for the duration of the

project. Projects need an interdisciplinary core team of

people from important departments who stick with the

project from beginning to end. Core members typically

come from engineering and information technology,

marketing, production, customer and technical support,

quality assurance, and the finance department. The team

should also include customers or end users. A core team

thus has access to a range of technical expertise, and

can minimize handoff problems since every key depart-

ment is involved.

4. Ensure that the team members work full time on

one project. For the sake of speed, the core team —

and other team members who join in — should work

exclusively on one project before moving on to other

projects.

5. Co-locate core team and other team members,

especially on new product development projects. The

more communication there is between team members,

the better. Communication is easier if everyone is work-

ing in the same location. Some organizations like

Chrysler and General Motors have even constructed spe-

cial development centers for that purpose.

6. Develop upper management support. Project fail-

ure is often caused by lack of upper-management sup-

port. Once committed, upper management should con-

tinue to support the project through completion.

To the degree that these practices are optimized, cycle

time will be reduced. ■

Understand the Customer

and the Competition

No matter what type of project you are directing, the

project outcome will end up in the marketplace. This

holds true, obviously, for new product development

projects. It also holds true for internal projects, as they

ultimately benefit the end user. Perhaps, for example,

the project leads to more efficient operations or better

5

The Project Manager’s MBA —

SUMMARY

(continued on page 6)

Soundview Executive Book Summaries

®

The Folly of Multitasking

Multitasking, which requires people to work on

more than one project at a time, is a sure way to

decrease focus, decrease output and increase cycle

time. Despite this, many organizations have embraced

multitasking. The problem: It doesn’t work. People are

not so easily divisible. It takes time to shift from one

project to another and back again. That time quickly

adds up in a typical workweek, and can actually

increase the amount of time it takes to complete proj-

ects because the time required to switch between

projects is non-productive. If two-way multitasking is

a minor folly, asking people to work on three or more

tasks borders on absurdity.

Cost Overruns Aren’t Always Bad

Sometimes it makes sense to pour extra money

into a project in order to finish it on time. According

to a 1989 McKinsey and Company study, if a project

is late for an amount of time equal to 10 percent of

the projected life of the product, there will be a loss

of about 30 percent of potential profit. But if the proj-

ect budget is over by 50 percent, yet the product

launched on time, there will be a loss of only about 3

percent of the potential profit. The advantage of being

first to market offsets the additional cost. In other

words, most companies will be better off pouring

additional money into the project to get it out the

door on time than they will be sticking to the old

budget and finishing later.

trained sales and service staff.

As a project manager, you must understand the cus-

tomer and deliver a result he or she wants and will buy —

thus generating revenue for the company. The key is to

understand the competitive forces at work in the market.

Build It and They Still Might Not Come

The first step to generating revenue is to design prod-

ucts, services and processes that help customers solve

problems and meet or exceed customer expectations.

Unfortunately, the traditional project manager’s thinking

has been that selling the product was not his problem,

but the marketing department’s. The implicit message

was that, “if we build it, they will buy it.”

That approach has proven wrong. Consider the ill-fated

Iridium project, which aimed to use satellite technology

to provide global telephone service. It turned out there

was no market for the service once it was developed.

One way to avoid this mistake is to try to get a mem-

ber of the marketing department on the project team.

Most important, however, is for you as a project director

to have a clear understanding of market needs. You

should be able to identify what the customer or end-user

really wants, understand the competition, make trade-

offs between features and price or cost, and determine

the timing of the product introduction.

Understanding the Market

Project managers need to look at the market for their

end product or service. That analysis must include:

Size. How big is the market? For new product proj-

ects, the size of the market is the total annual sales of

this type of product to all market segments. For in-

house projects, it is the total number of end-users who

will be affected by the project results. For client engage-

ment projects, it is the number of client customers who

will be affected by the project outcome.

Segmentation. What part of the market is the target?

All markets are composed of segments, which are

defined by customer attributes. For example, the cloth-

ing market is divided into male or female, young and

old, high fashion and casual, and so on. Select a seg-

ment and stick with it. Companies that try to serve every

segment tend to serve none well. Choose your cus-

tomers, narrow your focus, and dominate your market

segment.

Competition: Who is in pursuit of the same segment?

The relevant competition consists of organizations that

are aiming at the same segment with a similar strategy

and with solutions to the same problems. You must

know the competition, rate how your solution to cus-

tomers’ problems compare, and figure out how to con-

vey the superiority of your product to customers.

Understanding the Customer

Project managers and team members must take time

to understand the customer so that they can provide

what the customer wants.

A customer is the person who actually pays for the

product or service you are developing. That customer

might not be the end-user — the person who actually

benefits from the product or service. For example, moth-

ers might buy condensed soup to be eaten by a child.

The mother is the customer, but the child ultimately ben-

efits from the production of the soup. You must please

the end-user, not just the customer. If the child refuses to

eat the soup, the mother will not buy it again. More like-

ly, she will buy the brand of soup the child will eat.

Both customers and end-users want you to solve prob-

lems for them with your product or service. The best

way to solve customer problems is to create a prototype

and put it into customer and end-user hands. Never rely

on market data alone.

6

The Project Manager’s MBA —

SUMMARY

Soundview Executive Book Summaries

®

Understand the Customer and the

Competition

(continued from page 5)

(continued on page 7)

Pinpointing the Competition

In order to compete, you have to know who your

competitors are. That may sound obvious, but in

practice it is harder than you think. Follow these

steps to size up the competition:

1. Draw up a list of competitors in the market

you have defined for yourself. For example, Coke

could list only Pepsi as a competitor if it defined its

market as the cola drinking public. If it defined the

market as soft drink buyers, the list of competitors

grows. If that market is expanded further to include

all beverages, the list of competitors grows even

longer.

2. Next, the project team agrees on who should

be on the competitor list and then assigns team

members to monitor specific competitors. Keep up

with your assigned competitor’s technological

advances.

3. Finally, try to envision how new competitors

might look and how likely they are to appear on

the horizon. What are the barriers to entry? Are

those barriers changing? You must also think like a

new competitor. Whatever you could do to compete

is probably what a potential competitor is doing out

there right now.

The problem, of course, is that customers don’t

always know what they want. In order to reach them,

you may have to have technical members of the team sit

down with them. Here are some practical ways to get

customer and end-user involvement:

1. Put customers and end-users on the core team.

2. Directly observe end-users’ problems. Get out in

the field and see the problems from their point of

view.

3. Develop focus groups to explain problems.

4. Develop prototypes to give end-users experience.

A good understanding of the market will help the core

team set the price. For new product development projects,

that price is a reflection of the features, the competition,

and the time of market entry. Features that customers

want and need add to the price, while unwanted or

unneeded features don’t translate into a higher price. ■

Calculate the Project Costs

Cash flow, break-even analysis, and return to share-

holders are important concepts for project managers.

Profit equals revenue minus costs. Thus, the revenue

from a project must exceed its development and produc-

tion costs. Today, much more so than in the past, project

managers are responsible for calculating the cost of

their projects rather than being the victims of an

assigned budget that may not be in the company’s long-

term interest.

There are four types of costs that project managers

need to be familiar with: variable direct costs, variable

indirect costs, fixed direct costs and fixed indirect costs.

Variable direct costs are costs for the parts used to

make a product. They are direct costs because they go

directly into the production of the product. They are

variable because they increase or decrease depending on

the volume of the product you produce.

Variable indirect costs also increase or decrease

depending on production levels, but they cannot be

attributed directly to a product. For example, the plastic

used to create a doll would be a variable direct cost, but

the electricity used in the factory that makes the doll is

a variable indirect cost because it cannot practically be

assigned to a specific doll.

Fixed direct costs are incurred to run projects or pro-

duction. For example, the computer hardware needed to

work on a project is a fixed direct cost. The cost is fixed

because it does not matter whether the company is using

the computer or not.

A fixed indirect cost also does not change with produc-

tion levels, but remains the same. It also cannot be directly

tied to a product. An example of a fixed indirect cost is

7

The Project Manager’s MBA —

SUMMARY

Soundview Executive Book Summaries

®

Understand the Customer and the

Competition

(continued from page 6)

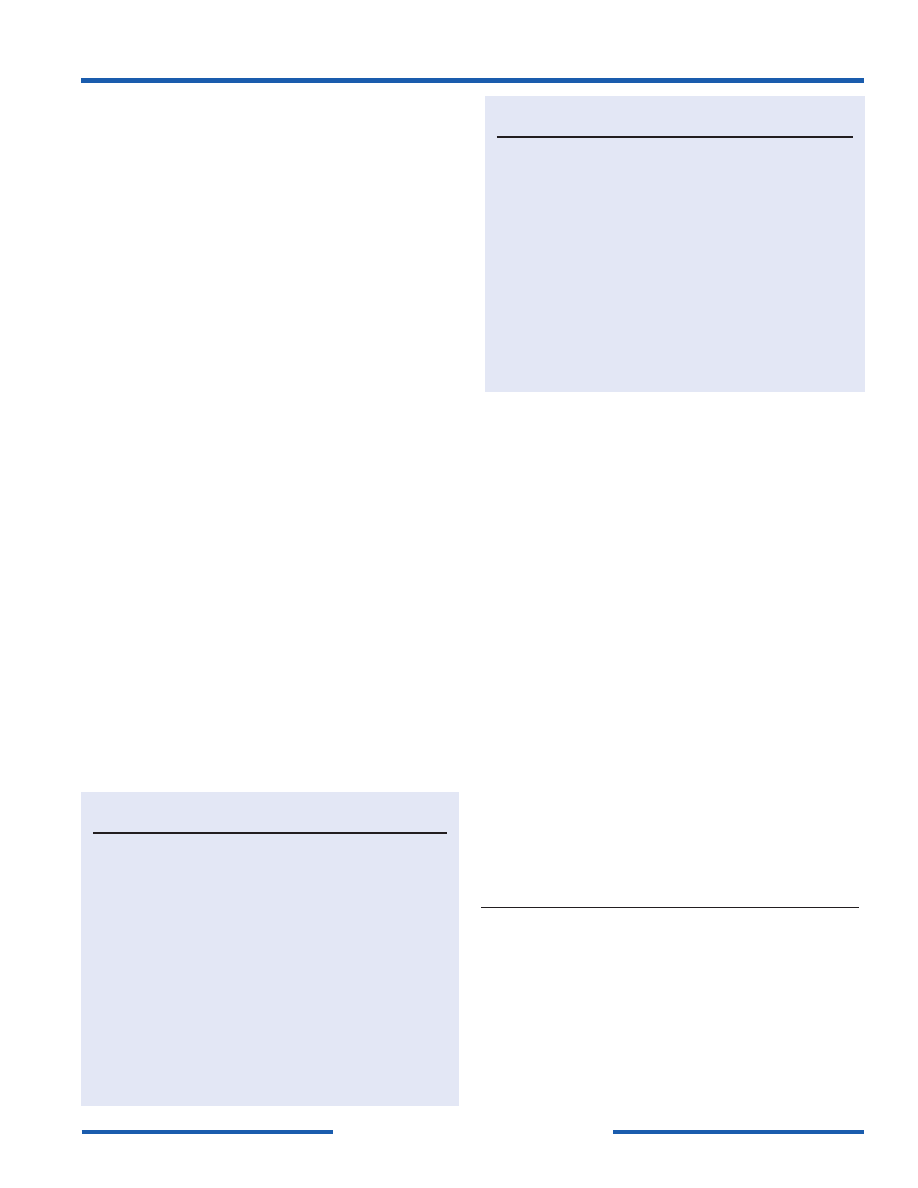

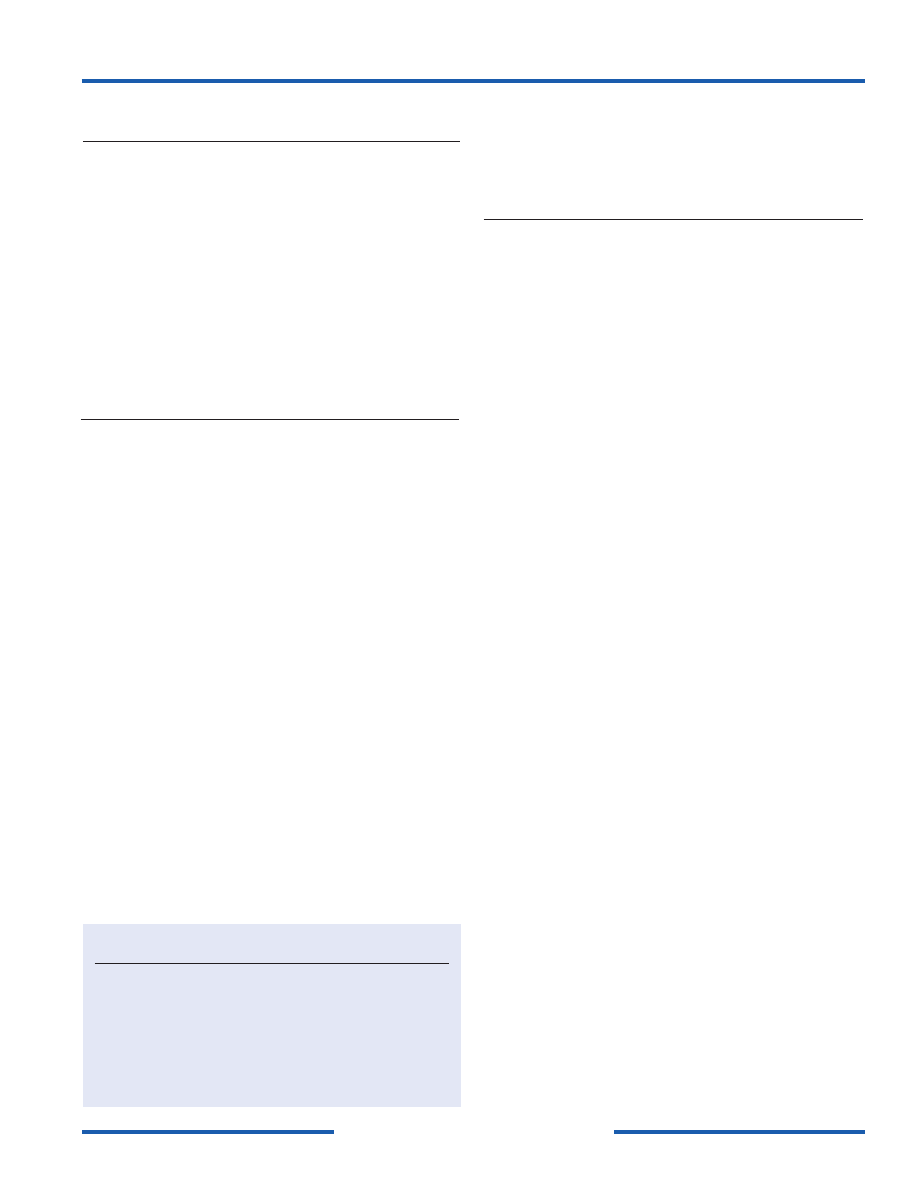

Concept Lifecycle

Each product or service a company produces to

solve a problem has a concept lifecycle. For exam-

ple, take putting words on paper. Words can be

committed to paper with a pen, a printing press, a

typewriter, a dot matrix printer, an inkjet printer and

a laser printer. Each of these concepts for commit-

ting words to paper has a lifecycle. If your company

tried producing and selling a typewriter today, you

would be too late in the product lifecycle to benefit.

If you are selling a pen, you are probably still early

enough in the lifecycle to make a profit.

Different customers will buy your product depend-

ing on where the product or service is in the cycle.

Some customers are innovators, buying up the

product very early. Others are early adopters, part of

the early majority, the late majority, or laggards. The

innovators are the first to buy a new product, while

the laggards wait until everyone else has one. The

concept adoption life cycle looks like this:

(continued on page 8)

Concept Adoption Curve

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

Early

Majority

Early

Adopters

Innovators

Late

Majority

Laggards

Direct costs

Indirect costs

Types of Costs

1. Variable direct costs

(example: cost of goods sold)

2. Variable indirect costs

(example: depreciation)

3. Fixed direct costs

(example: building rent)

4. Fixed indirect costs

(example: SG&A)

Variable Fixed

the computer center a large company might make avail-

able for its project managers. A fee is charged each month

to the project managers according to the size of their proj-

ect, but the amount of use does not change the charge.

Cost of Goods Sold

One set of costs that project managers should be

familiar with are the “cost of goods sold.” To calculate

the cost of goods, you must add the cost of materials

needed to make the product, the direct manufacturing

labor costs, and the manufacturing overhead cost. These

costs could be assigned directly to a project, but it

would be too costly to break them down enough to

place with the right project. ■

Why Finance Matters

for Project Managers

Projects develop assets that produce a return to the

company and its shareholders. Unless a business

demonstrates its ability to return cash, it will not get the

cash it needs to invest in and operate the business. No

cash to invest means no new projects and no business.

If projects are investments, managers need to under-

stand how they are financed. Unfortunately, too many

project managers ignore the cost of capital — that is, the

cost of acquiring the cash that makes the project possible.

The money to finance a project can be acquired in two

ways: through lenders or shareholders — those who buy

the company’s stocks. Neither lets companies use their

money for free. The cost of capital consists of the amount

of money that companies have to pay their lenders or

shareholders to compensate them for their investment and

satisfy their expected return on that investment.

When companies turn to lenders for capital, they

know exactly what the lender expects in return for the

loan. The interest charges can readily be added to proj-

ect cost. Shareholder expectations are not so easily con-

verted into project cost because their specific expecta-

tions are not stated. Nonetheless, managers should

attempt to estimate it when calculating project costs.

Before a project launches, there should be a careful

investment analysis made. A project must return at least

the amount of capital invested in the project plus the

cost of that capital. If it does not, it will not add value

for shareholders. ■

The Project Venture

Development Process

Good projects don’t just happen; they are well

planned and executed. If you want your project to add

economic value to the company and further its strategic

vision, you must plan accordingly. Here are the steps

you need to take for each project:

Develop a Business Case. Begin by developing a

business case for each project. The business case

process forces you to focus on the desired outcome.

State where the numbers in your projections come from,

including anticipated sales volumes, and the production

and operating costs. Make sure the assumptions that

drive the numbers are realistic. Clarify why this project

is a sound investment for the company.

Think Strategically. Consider projects in their wider

context. How does the project fit into the company’s

long-term strategy? Does it support an existing sustain-

able competitive advantage, or does it create a new one?

Describe the big picture and link the project to other

projects for an overall view of how it all fits together.

Create a Business Plan. Before starting the project,

develop a business plan. Do market research and scope

out the competition. Be sure to assemble the core team

and include them in this stage. Identify major mile-

stones at which you will stop and check your assump-

tions and progress.

Execute and Control the Project through the

Business Plan. Don’t put away the business plan once

the project has begun. Use it all along to guide the proj-

ect and check your assumptions.

Transition Smoothly to the Project Outcome

Lifecycle. The end of the project is the beginning of its

implementation. Core team members should be along as

guides. The team should also produce a final report with

numbers, projections and assumptions about the success

of the product or service the project created. These can

then be checked against what really happens as a learn-

ing experience.

Operate and Evaluate. The project isn’t over until

the end of the project outcome lifecycle. Once the life-

cycle is over, evaluate how well expectations were met.

This serves as a way of celebrating success and learning

from failure. ■

8

The Project Manager’s MBA —

SUMMARY

Soundview Executive Book Summaries

®

Calculate the Project Costs

(continued from page 7)

Projects Make the Business

Financially, a company is a portfolio of assets pro-

duced through projects. The present operations of

any company were developed by past projects and

improved and supported by current projects. Future

projects will lead to the strategic implementation of

future operations. If project outcomes do not meet

investor expectations, then neither will the company.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Project Management Six Sigma (Summary)

The story of an hour summary and analisisdocx

the lame shall enter first summary and analisisdocx

cohen the strength of weak ties summary

9781933890517 Appendix F Summary of Project Management

The Golden Rules Of Project Management Shaw

Serge Charbonneau Software Project Management A Mapping Between Rup And The Pmbok

Tom Gilb The Evolutionary Project Managers Handbook

Tom Gilb The Evolutionary Project Managers Handbook

Agile Project Managemnet

ZPT 02 Project management processes V2 odblokowany

Business 10 Minute Guide to Project Management

2003 formatchain and network management gilda project

BYT 2006 Communication in Project Management

PROJECT MANAGEMENT 2008 NEW

project-management-jako-rozwojowa-koncepcja-wykorzystywana-w-innowacyjnosci, Chrzest966, MAP

Project Manager, Chrzest966, MAP

Fundamentals of Project Management 4th ed J Heagney (AMACOM, 2012)

1 Project Management Basics

więcej podobnych podstron