C

ha

pt

er

60

418

Kerry Bron, MD, and

Avrum N. Pollock, MD

Pediatric Gastrointestinal radioloGy

1. What are the most common causes of small bowel obstruction in a child?

AAIIMM is a mnemonic that makes it easy to remember the causes:

•

A = Adhesions, usually postsurgical

•

A = Appendicitis

•

I = Intussusception

•

I = Incarcerated inguinal hernia

•

M = Malrotation with volvulus or bands

•

M = Miscellaneous, such as Meckel diverticulum or intestinal duplication

2. What is intussusception?

Intussusception is a condition in which a proximal portion of the bowel (intussusceptum) telescopes into the

adjacent distal bowel (intussuscipiens). When the inner loop and its mesentery become obstructed, a small bowel

obstruction occurs.

3. What causes intussusception?

In most cases, intussusception is idiopathic. In less than 5% of cases, the intussusception contains a lead point, such as

a polyp, Meckel diverticulum, or hypertrophic lymphatic tissue. Most intussusceptions are ileocolic.

4. Describe the clinical signs of intussusception.

The classic clinical triad of intussusception is intermittent colicky abdominal pain, current jelly stools, and a palpable

abdominal mass. Less than 50% of patients present with these symptoms, however. Children often cry and are very irritable

during bouts of abdominal pain, and then become drowsy and lethargic. Vomiting and fever may also occur. Intussusception

is most common in children 3 months to 4 years old, with a peak incidence at 3 to 9 months. It is more common in boys.

5. How is intussusception diagnosed radiologically?

The most accurate technique for the diagnosis of intussusception is ultrasound (US). The characteristic US appearance

is a mass that measures 3 to 5 cm, which is easily detectable. On the transverse scan, the mass has a “target”

appearance that contains echogenic fat. The

“pseudokidney” sign appears in the longitudinal

direction. A barium enema can also be used to

diagnose intussusception. Although the plain

film has been used in the past to diagnose

intussusception by detection of a soft tissue mass

in the right upper quadrant and lack of large bowel

gas, particularly in the right upper quadrant, studies

have shown poor interobserver agreement and

predictive value of only approximately 50%.

6. How is an intussusception treated?

An intussusception is treated by air enema with

fluoroscopic guidance or hydrostatic enema

using barium or water-soluble contrast agent

(

). The advantages of the air enema are

that it is quicker, less messy, easier to perform,

and delivers less radiation to the patient. The

only contraindications to enema reduction of

intussusception are pneumoperitoneum or peritonitis.

The air enema can generates pressure of 120 mm Hg

to reduce the intussusception.

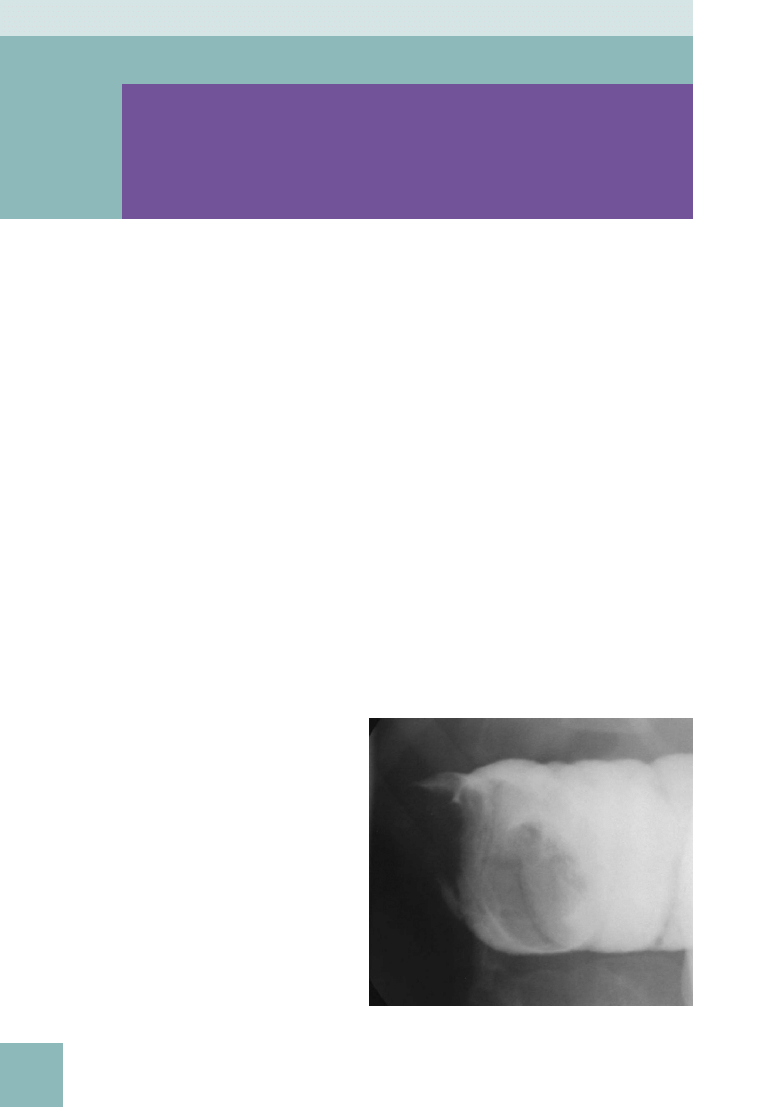

Figure 60-1.

Spot radiograph from a contrast enema examination

shows intussusception, with the lead point outlined by the barium.

419

7. How can one tell that an intussusception has been successfully reduced?

If a successful air reduction has been performed, fluid with air bubbles should be seen passing through the ileocecal

valve into the terminal ileum. If a successful reduction with contrast agent has been performed, contrast agent must

reflux into multiple loops of small bowel. If reflux into the small bowel is not seen, the intussusception may not have

been completely reduced, and a distal lead point may have been overlooked.

8. Describe the “double bubble” sign,

and name the conditions in which it

is found.

The “double bubble” sign is found on plain

radiographs and represents an air-filled or fluid-

filled distended stomach and duodenal bulb (

). It is seen in malrotation, duodenal atresia,

and jejunal atresia.

9. What is malrotation of the

intestines?

Malrotation of the intestines is a misnomer because

it is really nonrotation or incomplete rotation of

the bowel. To understand malrotation, one must

first consider normal embryologic rotation of the

intestines. During normal embryologic development

in the first trimester, the midgut leaves the

abdominal cavity, travels into the umbilical cord, and

returns to the abdominal cavity. As the intestines

return, the proximal and distal parts of the midgut

rotate around the superior mesenteric artery axis

270 degrees in a counterclockwise direction. The

ligament of Treitz (duodenojejunal junction) lands in

the left upper quadrant, and the cecum comes to

rest in the right lower quadrant. In malrotation, this

intestinal rotation and fixation occur abnormally. If

normal rotation does not occur, the cecum is not

anchored in the right lower quadrant and may be

midline or in the upper abdomen. The small bowel is

not anchored in the left upper quadrant and may lie

entirely in the right abdomen.

10. What are Ladd bands?

Ladd bands are dense peritoneal bands that develop as an attempt to fix the bowel to the abdominal wall in malrotation.

They may extend from the malpositioned cecum across the duodenum to the posterolateral abdomen and porta hepatis

in either incomplete rotation or nonrotation and can cause extrinsic duodenal obstruction.

11. How does a midgut volvulus occur, and why is this an emergency?

Lack of attachment of the midgut to the posterior abdominal wall allows the midgut to twist on a shortened root

mesentery, which results from lack of complete rotation (

). This twisting is called a volvulus, and it causes

small bowel obstruction with concomitant obstruction to the lymphatic and venous supply of the bowel and eventually

to the arterial supply, which leads to ischemia and necrosis. If it is not repaired within several hours, all of the intestine

supplied by the superior mesenteric artery undergoes infarction.

12. Does a patient with malrotation always present with clinical symptoms.

Not all patients with malrotation are symptomatic because not all develop a midgut volvulus or extrinsic duodenal

obstruction from Ladd bands.

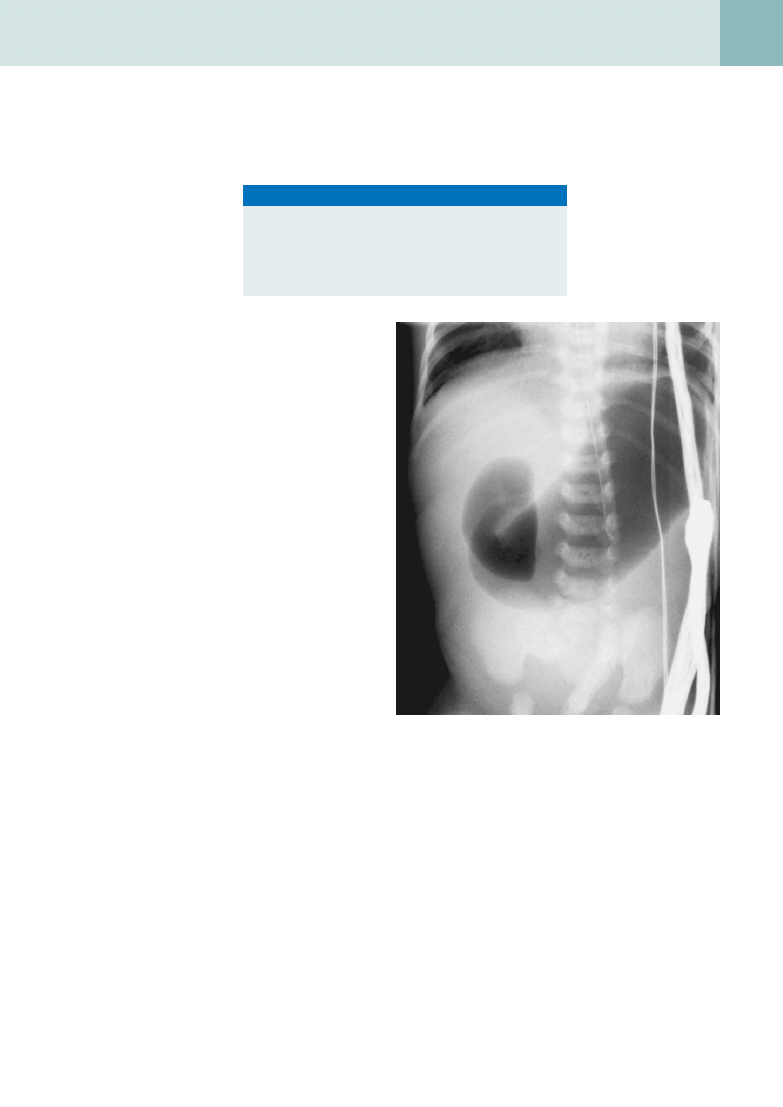

Figure 60-2.

Plain film of the abdomen in a child with duodenal

atresia, showing a dilated stomach and duodenal bulb—the “double

bubble” sign.

Key Points: Intussusception

1. Common cause of small bowel obstruction in children

2. Idiopathic in children, in contrast to in adults

3. Usually ileocolic

4. Diagnosed by US

5. Treated with air enema or contrast barium enema

pediatric radiology

420

pediatric gastrointestinal radiology

13. What is the clinical presentation of

malrotation?

Patients with incomplete rotation who have intestinal

obstruction usually present within the first week or first

month of life (75% of patients). They present with an acute

onset of bilious vomiting, which is a surgical emergency.

Some patients present later in childhood with intermittent

mechanical obstruction, which manifests as cyclic

vomiting. Malrotation in the remaining patients is often

found incidentally when the patients are studied for other

complaints.

14. Which study is the gold standard for

diagnosing malrotation?

The upper gastrointestinal (GI) examination is the gold standard

for diagnosing malrotation. To confirm normal rotation of the

bowel, the ligament of Treitz, which attaches the third and

fourth parts of the duodenum, must be visualized to the left of

midline. If there is malrotation, the ligament of Treitz may be

located to the right of midline or in the midline. Often, there is

inversion of the superior mesenteric artery and vein, which can

be visualized on computed tomography (CT).

15. List other anomalies that are associated with

malrotation.

•

Duodenal atresia or stenosis

•

Meckel diverticulum

•

Omphalocele

•

Gastroschisis

•

Polysplenia/asplenia syndromes

•

Situs ambiguus

•

Bochdalek hernia

•

Renal anomalies

16. Describe the clinical presentation of pyloric stenosis.

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, which is the most common GI surgical disease of infancy in the United States, manifests

most commonly during the second to sixth weeks of life, with a peak incidence at 3 weeks of age and rare presentation

after age 3 months. The major symptom is progressive nonbilious vomiting, which starts as simple regurgitation and

progresses to projectile vomiting. This progressive vomiting leads to dehydration and hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis

and weight loss. The condition is more common in boys. A palpable “olive” representing the thickened pylorus muscle is

present in the right upper quadrant approximately 80% of the time if the infant can be examined in a calm manner with

decreased stomach distention.

17. If the “olive” cannot be palpated, how can pyloric stenosis be diagnosed with

radiologic studies?

The evaluation can begin with a supine or prone plain film of the abdomen, which can exclude other diagnoses

that could be causing similar obstructive symptoms. The plain film would also reveal a markedly dilated stomach,

soft tissue mass projecting into the gastric antrum, and paucity of gas in the distal bowel. The suspicion of pyloric

stenosis can be confirmed with either US or fluoroscopy. US is the imaging test of choice because it directly

visualizes the hypertrophied pylorus muscle without radiation (

), whereas an upper GI series infers the

presence of pyloric stenosis indirectly. With US, the pylorus muscle is seen as a hypoechoic structure greater than 4

mm thick surrounding an echogenic compressed pyloric channel. Although less sensitive, the pyloric channel length

is another measurement used to make the diagnosis. A length greater than 17 mm is considered diagnostic for

pyloric stenosis.

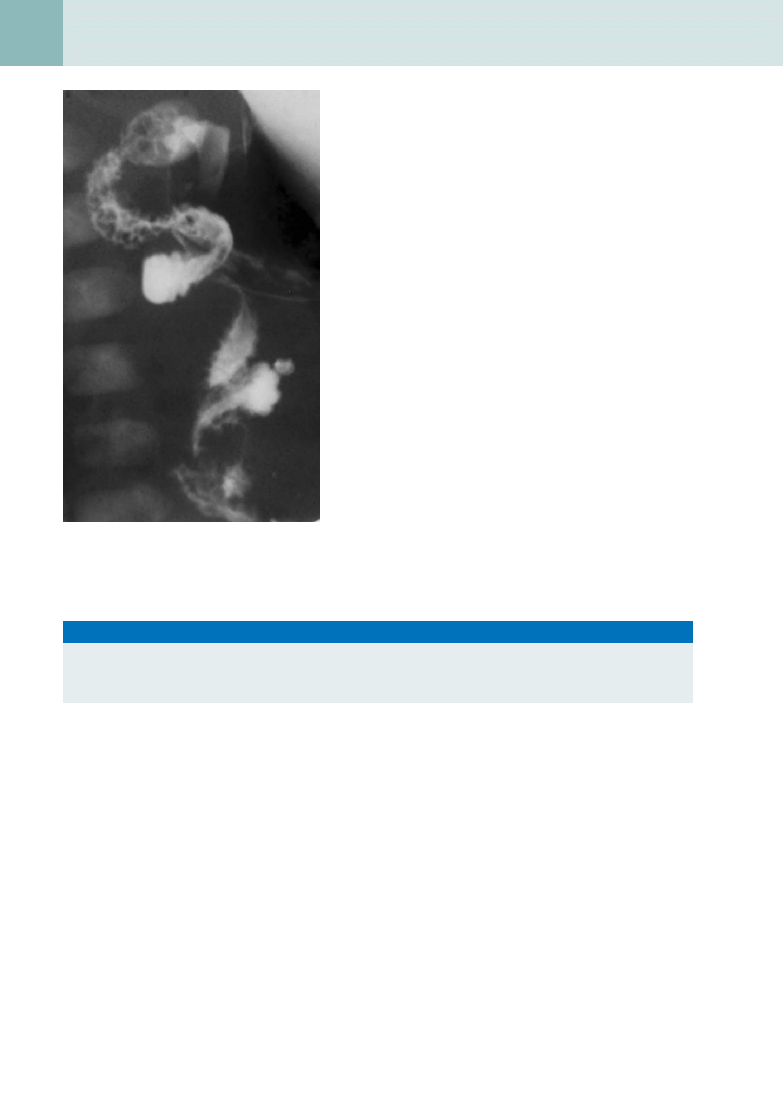

Figure 60-3.

Spot radiograph from an upper GI

examination showing the “corkscrew” finding of a midgut

volvulus.

Key Points: Malrotation of the Intestines

1. Malrotation causes small bowel obstruction through a midgut volvulus and Ladd bands.

2. Malrotation causes altered GI anatomy, with the ligament of Treitz not situated in the left upper quadrant and the

cecum not in the right lower quadrant.

pediatric gastrointestinal radiology

421

pediatric radiology

18. What is Meckel diverticulum?

Meckel diverticulum is the most common

anomaly of the GI tract. It is a persistence of the

omphalomesenteric duct at its junction with the

ileum. It can be remembered by the rules of 2:

It occurs in 2% of the population, 2% develop

complications, complications usually occur before

2 years of age, and it is located within 2 feet of the

ileocecal valve. The most common complication

of Meckel diverticulum is painless GI bleeding,

which occurs secondary to irritation or ulceration

from production of hydrochloric acid by the gastric

mucosa that lines it.

19. How is Meckel diverticulum

diagnosed?

Meckel diverticulum is detected by a nuclear

medicine scan with technetium (Tc)-99m

pertechnetate. The tracer accumulates within the

diverticulum, usually appearing at or approximately

at the same time as activity in the stomach, with

gradually increasing intensity, which verifies the

presence of ectopic gastric mucosa.

20. What are the most common causes of GI bleeding in children?

The differential diagnosis depends on the age of the patient (

21. What causes necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)?

NEC is a multifactorial condition that has traditionally been thought to be caused by hypoxia, infection, and enteral

feeding. The pathology of NEC resembles that of ischemic necrosis. It may be that the main pathologic trigger in NEC

is injury to the intestinal mucosa, which can be caused by different factors in different patients.

22. Who develops NEC?

Approximately 80% of patients who develop NEC are premature infants. Older infants who develop NEC usually have

severe underlying medical problems, such as Hirschsprung disease or congenital heart disease. Patients with this

condition present with abdominal distention, vomiting, increased gastric residuals, blood in the stool, lethargy, apnea,

and temperature instability.

23. What findings of NEC can be seen on plain x-ray film, and what is the role of the

radiologist?

The radiographic findings of NEC are nonspecific when the condition is first suspected. Films are obtained serially; the

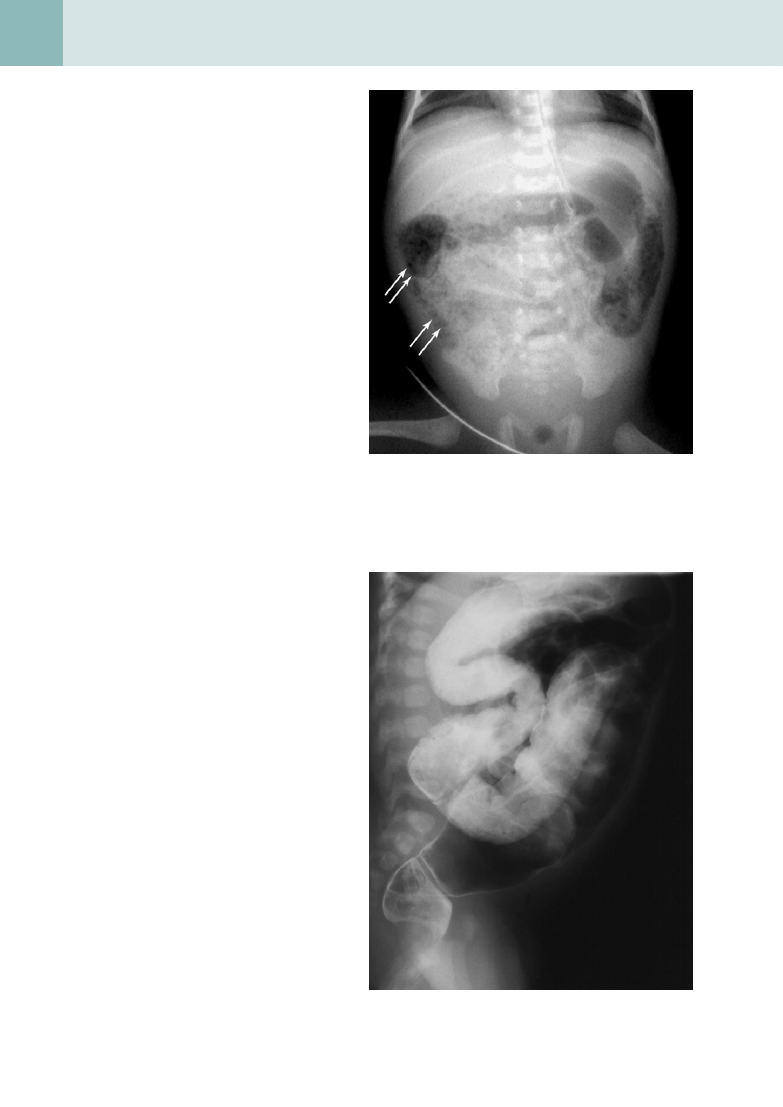

role of the radiologist is to try to diagnose the condition before bowel perforation occurs. In early NEC, the most commonly

detected abnormality is diffuse gaseous distention of the intestine. A more useful sign of early NEC is loss of the normal

symmetric bowel gas pattern, with a resulting disorganized or asymmetric pattern. In more advanced NEC, the finding

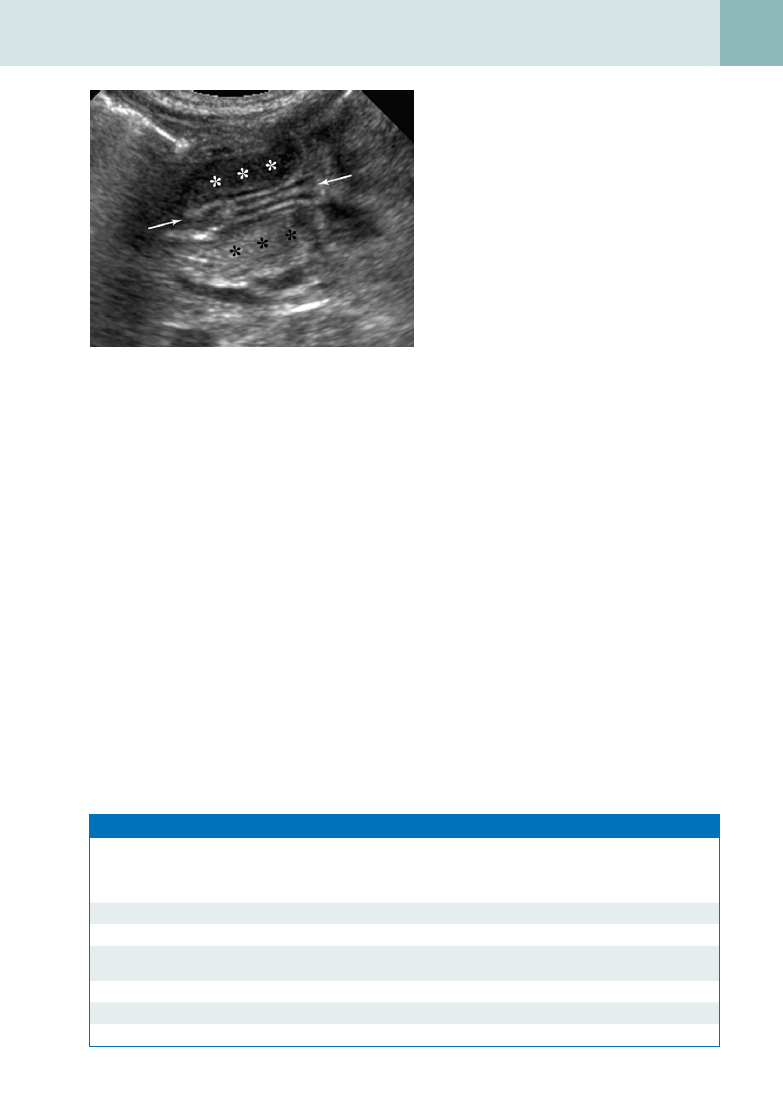

Figure 60-4.

US examination of the pylorus shows hypertrophic

pyloric stenosis. The thickened walls of the pylorus (asterisks) surround

the central lumen (arrows).

Table 60-1. Common Causes of Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Children

NEWBORN AND

NEONATE (<1 MO)

YOUNG INFANT

(1-3 MO)

OLDER INFANT

(3 MO–1 YR)

CHILD (1-10 YR)

Swallowed maternal blood

Esophagitis

Esophagitis

Esophagitis

Anal fissure

Intussusception

Anal fissure

Esophageal varices

Necrotizing enterocolitis

Anal fissure

Colon polyp

Colon polyp

Hemorrhagic disease of the

newborn

Gangrenous bowel

Intussusception

Anal fissure

Allergic or infectious colitis

Meckel diverticulum

Gangrenous bowel

Foreign body

Foreign body

Crohn disease

Ulcerative colitis

422

pediatric gastrointestinal radiology

of pneumatosis intestinalis (intramural gas) is

pathognomonic for the condition (

). Gas in

the portal venous system is another pathognomonic

finding in NEC, which occurs in 10% to 30% of

cases. Infants at risk for imminent perforation

often have portal venous gas. They may have the

persistent loop sign, which is a dilated loop of

intestine that remains unchanged over 24 to 36

hours. Another grave sign is a shift from a pattern

of generalized dilation to asymmetric bowel dilation.

Ascites is another sign of impending perforation.

When pneumoperitoneum develops, this is a definite

sign that the bowel has perforated, and the infant

must have surgery.

24. What are other causes of

pneumoperitoneum in infants and

children?

The most common causes are surgery and

instrumentation. Pneumoperitoneum can be

found after laparotomy, after paracentesis, or

after resuscitation. Also, distal bowel obstruction

from conditions such as Hirschsprung disease

or meconium ileus and dissection of air from

pneumomediastinum, a ruptured ulcer, or Meckel

diverticulum can cause pneumoperitoneum.

25. What is Hirschsprung disease?

Hirschsprung disease is a condition of distal

aganglionic bowel that results from the lack

of Auerbach (intermuscular) and Meissner

(submucosal) plexuses. Functional obstruction

of the distal bowel results. Hirschsprung disease

usually manifests in the first 48 hours of life with

the failure to pass meconium, or it may manifest

with abdominal distention, bilious vomiting, or

diarrhea. More than 80% of patients present in the

first 6 weeks of life.

26. What are the plain x-ray film

findings of Hirschsprung disease?

The most typical plain film finding of Hirschsprung

disease is a dilated colon proximal to the distal and

smaller aganglionic segment. Radiographs may also

show high-grade distal bowel obstruction. Radiologic

diagnosis of Hirschsprung disease requires a

). Spot radiographs are

obtained in the lateral and oblique projections, and

the examination is stopped after a transition zone

has been identified. The barium enema can show

the transition zone, which is situated between a

narrowed aganglionic segment and the distended

proximal bowel. The x-ray transition zone may be

visualized more distally than the histologic transition

zone secondary to stool dilating the proximal part of

the aganglionic segment.

27. Is Hirschsprung disease diagnosed

definitively by imaging?

To make a definitive diagnosis of Hirschsprung

disease, a rectal biopsy specimen must be obtained

that shows lack of ganglion cells.

Figure 60-5.

Plain film radiograph of the abdomen in a patient

with NEC. The mottled pattern of air in the bowel wall (arrows) is

typical of NEC.

Figure 60-6.

Lateral spot radiograph from a barium enema

examination in a patient with Hirschsprung disease shows transition

zone (from dilated to nondilated bowel) in the distal colon.

pediatric gastrointestinal radiology

423

pediatric radiology

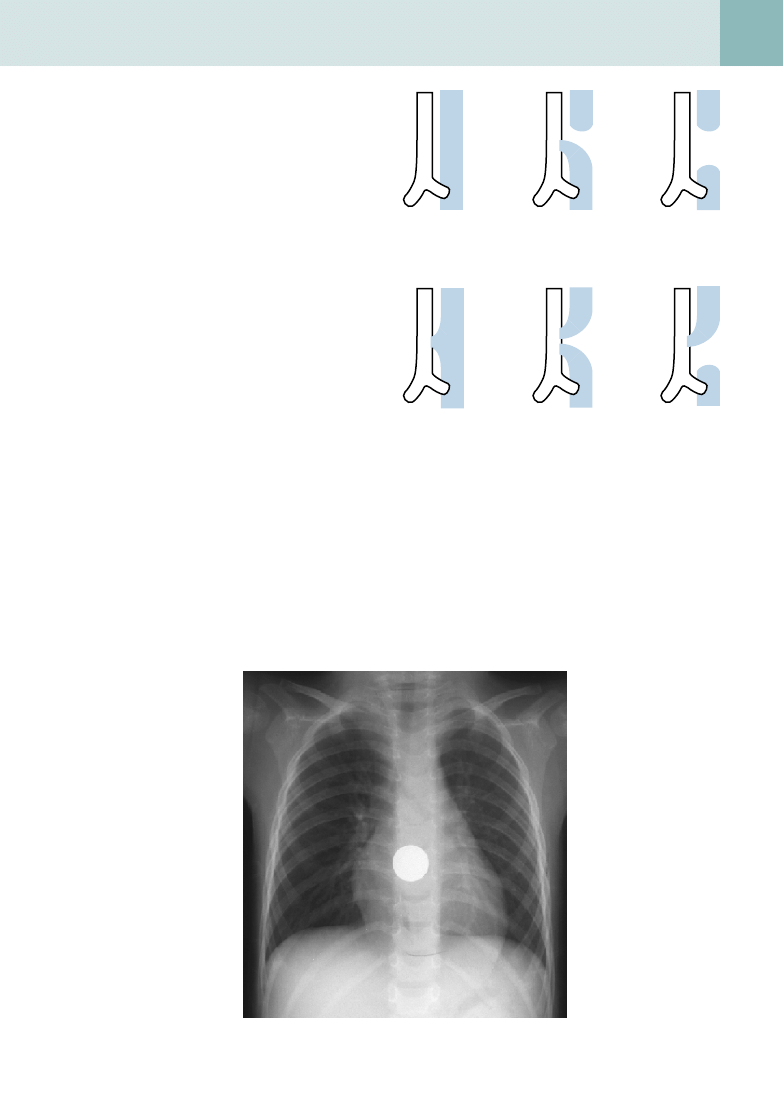

28. Name the types of tracheoesophageal

fistulas (TEF). How common is each

type?

•

The most common type of TEF is esophageal

atresia with distal esophageal communication

with the tracheobronchial tree (

). This

accounts for more than 80% of cases.

•

The next most common type is esophageal atresia

without a TEF, which accounts for almost 10% of

cases.

•

H-type fistulas occur between an otherwise

intact trachea and esophagus and account for

approximately 5% of cases.

•

Esophageal atresias occurring with proximal and

distal communication with the trachea are found

in less than 2%

of cases, and esophageal atresia with proximal

communication is rare.

TEF is associated with VACTERL syndromes

(in which affected patients manifest at least

three of the following: vertebral anomalies, anal

atresia/imperforate anus, cardiac anomalies,

tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb

anomalies).

29. What are the plain film findings in

TEF?

In a patient with esophageal atresia (and no fistula

or a proximal fistula), plain film may reveal a gasless

abdomen. A nasogastric tube may be seen coiled in the proximal esophagus. Patients with esophageal atresia with a distal

TEF or H-type fistula may present with a distended abdomen. Aspiration is a risk for all patients with esophageal atresia.

30. How can a plain film help to differentiate a coin in the esophagus from a coin in the

trachea?

On a plain chest film, a coin in the esophagus is visualized as a round object en face (a full circle can be seen)

(

). A coin in the trachea lies sagittally and appears end-on in a posteroanterior film.

A

B

C

D

E

F

Figure 60-7.

Different types of TEF.

A, Normal relationship of

esophagus anterior to trachea—no atresia or fistula.

B, Esophageal

atresia with distal TEF—most common (>80%).

C, Esophageal atresia

with no TEF (approximately 10%).

D, H-type fistula with no esophageal

atresia (approximately 5%).

E, Esophageal atresia with proximal and

distal fistulas (<2%).

F, Esophageal atresia with a proximal fistula (1%).

Figure 60-8.

Posteroanterior plain film of the chest shows a coin in the esophagus.

424

pediatric gastrointestinal radiology

B

iBliography

[1] C. Buonomo, The radiology of necrotizing enterocolitis, Radiol. Clin. North Am. 37 (1999) 1187–1197.

[2] A. Daneman, D. Alton, Intussusception: issues and controversies related to diagnosis and reduction, Radiol. Clin. North Am. 34 (1996)

743–755.

[3] K. Hayden, Ultrasonography of the acute pediatric abdomen, Radiol. Clin. North Am. 34 (1996) 791–806.

[4] M. Hernanz-Schulman, Imaging of neonatal gastrointestinal obstruction, Radiol. Clin. North Am. 37 (1999) 1163–1185.

[5] D.R. Kirks, Practical Pediatric Imaging: Diagnostic Imaging of Infants and Children, third ed., Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, 1997.

[6] W. McAlister, K. Kronemer, Emergency gastrointestinal radiology of the newborn, Radiol. Clin. North Am. 34 (1996) 819–844.

[7] D. Merten, Practical approaches to pediatric gastrointestinal radiology, Radiol. Clin. North Am. 31 (1993) 1395–1407.

Document Outline

- Pediatric Gastrointestinal Radiology

- What are the most common causes of small bowel obstruction in a child?

- What is intussusception?

- What causes intussusception?

- Describe the clinical signs of intussusception

- How is intussusception diagnosed radiologically?

- How is an intussusception treated?

- How can one tell that an intussusception has been successfully reduced?

- Describe the “double bubble” sign, and name the conditions in which it is found

- . What is malrotation of the intestines?

- . What are Ladd bands?

- How does a midgut volvulus occur, and why is this an emergency?

- Does a patient with malrotation always present with clinical symptoms

- What is the clinical presentation of malrotation?

- Which study is the gold standard for diagnosing malrotation?

- List other anomalies that are associated with malrotation

- Describe the clinical presentation of pyloric stenosis

- If the “olive” cannot be palpated, how can pyloric stenosis be diagnosed with radiologic studies?

- What is Meckel diverticulum?

- How is Meckel diverticulum diagnosed?

- What are the most common causes of GI bleeding in children?

- What causes necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)?

- Who develops NEC?

- What findings of NEC can be seen on plain x-ray film, and what is the role of the radiologist?

- What are other causes of pneumoperitoneum in infants and children?

- What is Hirschsprung disease?

- What are the plain x-ray film findings of Hirschsprung disease?

- Is Hirschsprung disease diagnosed definitively by imaging?

- Name the types of tracheoesophageal fistulas (TEF). How common is each type?

- What are the plain film findings in TEF?

- How can a plain film help to differentiate a coin in the esophagus from a coin in the trachea?

- Bibliography

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

C20090551288 B9780323067942000420 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000055 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000407 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000225 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000432 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000547 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000298 main

C20090551288 B978032306794200047X main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000250 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000638 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000316 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000286 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000560 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000341 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000390 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000766 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000754 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000122 main

C20090551288 B9780323067942000626 main

więcej podobnych podstron