A

t the beginning of the 1990s, Poland became the first country in post-communist Europe

to embrace rapid economic liberalization—a goal implemented by both center–right and

center–left governments. Years of economic transformation have led to deep structural

change and have made Poland’s economy one of the most successful and open in Central

Europe. Banking has been almost completely privatized, with foreign institutions owning 70

percent of total assets. Despite pressures from the Union of Labor and the Peasants Party (pop-

ulist coalition partners in the ruling Democratic Left Alliance) to loosen monetary policies, the

government has maintained its commitment to monetary discipline. The government’s ambi-

tious program to return the country to a path of sustained economic growth, announced in

October 2001, is focused on three major components: job creation for young professionals, sup-

port of medium and small enterprises, and infrastructure development. Exports depend large-

ly on European Union markets; Germany alone accounted for nearly 35 percent of exports in

2001. Therefore, joining the EU has become the overall political and economic priority for

Poland, which is also a member of the World Trade Organization and NATO. In June 2003,

Poles voted in a referendum to join the EU. Poland’s property rights score is 1 point worse this

year; however, its fiscal burden of government score is 0.2 point better, and its monetary poli-

cy score is 1 point better. As a result, Poland’s overall score is 0.02 point better this year.

TRADE POLICY

Score:

3–Stable

(moderate level of protectionism)

According to the World Bank, Poland’s weighted average tariff rate in 2000 (the most recent

year for which World Bank data are available) was 7.3 percent. The government maintains

non-tariff barriers through its issuance of import permits on a growing number of products.

The U.S. Department of State reports that these permit requirements “hamper import

prospects for certain bulk products that might otherwise be shipped in larger quantities on

ocean-going vessels.”

FISCAL BURDEN OF GOVERNMENT

Score—Income Taxation: 4–Stable

(high tax rates)

Score—Corporate Taxation: 3.5–Stable

(high tax rates)

Score—Change in Government Expenditures: 3.5–Better

(low increase)

Final Score:

3.6–Better

(high cost of government)

Poland’s top income tax rate is 40 percent. The top corporate tax rate is 27 percent, down

from the 28 percent reported in the 2003 Index, and is scheduled to fall to 24 percent in 2004.

Government expenditures as a share of GDP increased less in 2002 (0.8 percentage point to

43.2 percent) than they did in 2001 (1.7 percentage points). As a result, Poland’s fiscal bur-

den of government score is 0.2 point better this year.

GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION IN THE ECONOMY

Score:

2–Stable

(low level)

Based on data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the gov-

ernment consumed 15 percent of GDP in 2002. In 2001, according to the International

Monetary Fund, Poland received 3.96 percent of its total revenues from state-owned enter-

prises and government ownership of property.

SCORES

Trade Policy

3

Fiscal Burden

3.6

Government Intervention 2

Monetary Policy

2

Foreign Investment

3

Banking and Finance

2

Wages and Prices

3

Property Rights

3

Regulation

3

Informal Market

3.5

Population: 38,610,000

Total area: 312,685 sq. km

GDP: $166.8 billion

GDP growth rate: 1.3%

GDP per capita: $4,320

Major exports: machinery

and transport equipment,

miscellaneous manufactured

goods, food and live animals

Exports of goods and ser-

vices: $55.8 billion

Major export trading part-

ners: Germany 34.4%, France

5.4%, Italy 5.4%, UK 5.0%

Major imports: machinery

and transport equipment,

mineral fuels and lubricants,

chemicals

Imports of goods and ser-

vices: $56.9 billion

Major import trading part-

ners: Germany 23.9%, Russia

8.8%, Italy 8.2%, France 6.8%

Foreign direct investment

(net): $7.9 billion

POLAND

R

U

S

S

I

A

FINLAND

AUSTRIA

ITALY

SPAIN

SWEDEN

NORWAY

GERMANY

FRANCE

PORTUGAL

HUNGARY

ROMANIA

BULGARIA

TURKEY

DENMARK

POLAND

BELARUS

UKRAINE

CZECH

SLOVAK

GREECE

CYPRUS

NETH.

BELGIUM

IRELAND

ALBANIA

MOLDOVA

LITHUANIA

LATVIA

ESTONIA

LUX.

BOSNIA

CROATIA

SLO.

SWITZERLAND

MACEDONIA

GREENLAND

ICELAND

Canary Islands

ARMENIA

GEORGIA

SYRIA

IRAQ

U. K.

SERBIA/

MONT.

Q U I C K S T U DY

331

2002 Data (in constant 1995 US dollars)

POLAND

Rank: 56

Score: 2.81

Category: Mostly Free

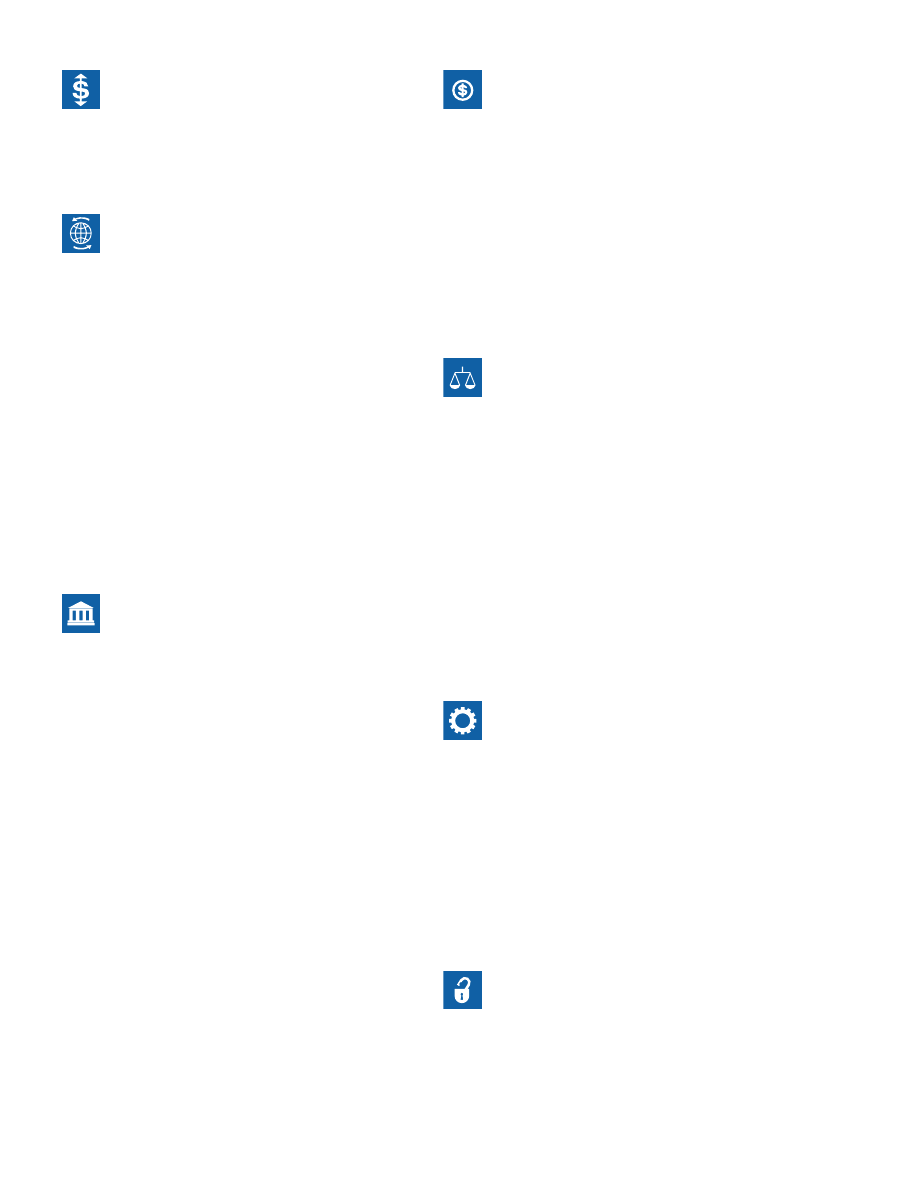

3.46 3.24

3.09 2.91 2.83 2.84

2.64 2.60 2.83

5

4

3

2

1

'04

'03

'02

'01

'00

'99

'98

'97

'96

'95

Present & Past Scores

2.81

(Best)

(Worst)

MONETARY POLICY

Score:

2–Better

(low level of inflation)

From 1993 to 2002, Poland’s weighted average annual rate of

inflation was 3.82 percent, down from the 7.17 percent from

1992 to 2001 reported in the 2003 Index. As a result, Poland’s

monetary policy score is 1 point better this year.

CAPITAL FLOWS AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

Score:

3–Stable

(moderate barriers)

Polish law allows 100 percent foreign ownership of domestic

businesses with such notable exceptions as broadcasting,

insurance, and aviation services. The government lifted the

cap on foreign ownership of telecommunications on January

1, 2001. Foreign purchase of land over a set area requires gov-

ernment approval. According to the U.S. Department of State,

foreign and domestic investors face considerable red tape. All

public procurement bids must contain a 50 percent domestic

material and labor content minimum clause, and the U.S.

Department of State reports that foreign firms “face potential

discrimination in public procurement contracts.” The

International Monetary Fund reports that both residents and

non-residents may hold foreign exchange accounts, subject to

certain restrictions. Payments, transactions, and transfers

over a specified amount must be conducted through a

domestic bank. Most capital transactions require foreign

exchange permits or central bank approval.

BANKING AND FINANCE

Score:

2–Stable

(low level of restrictions)

Until the late 1980s, Poland’s banking system was geared to

supporting the state-run economy. The National Bank of

Poland was established as the central bank in 1989 and oversaw

the creation of nine independent regional banks, which subse-

quently were privatized and joined by a number of new private

banks in the 1990s. The banking sector is now open and com-

petitive. There are 83 private banks, and foreign banks account

for 70 percent of assets. The Economist Intelligence Unit reports

that the government retains control of four state-owned banks

and intends to hold “a majority share in any sale involving

PKO BP [the largest Polish bank], raising concerns that PKO BP

will be used by the authorities to direct credit to chosen, ‘strate-

gic’ sectors.” Nevertheless, according to the U.S. Department of

State, “The majority of Polish banks have been privatized….

The majority of the Polish banking sector’s assets, deposits, and

equity are in the hands of the private sector. Foreign companies

do not have special restrictions on access to local finance as long

as funds are used for activities in Poland.” The insurance sector

is still dominated by the communist-era monopoly provider,

which is now partially privatized.

WAGES AND PRICES

Score:

3–Stable

(moderate level of intervention)

The government has removed a number of price controls but

continues to influence the prices of some products. According

to the Economist Intelligence Unit, “Official prices apply

under the following conditions and products: (1) to goods or

services when there are substantial threats to the proper func-

tioning of the economy as specified by the Council of

Ministers; (2) to pharmaceutical and medical materials that

are covered by health insurance; and (3) to prices for taxi ser-

vices…. [U]tility prices [are subject to] supervision if the

provider is market dominating….” A mandated minimum

wage is adjusted every three months through negotiations

involving the government, the unions, and employers.

PROPERTY RIGHTS

Score:

3–Worse

(moderate level of protection)

The threat of expropriation is low, but recent corruption

scandals have revealed serious weaknesses in Poland’s judi-

cial system. The transformation from communism to

democracy, reports the Financial Times, did not guarantee

that democratic institutions would function properly.

“Institutions were imported from the west without making

sure they could function. For example, the courts are nomi-

nally independent, but, in practice, underpaid officials are

often subject to corrupt influences.” According to the U.S.

Department of State, “Many investors—foreign and domes-

tic—complain about the slowness of the judicial system….

[I]nvestors often voice concern about frequent or unexpect-

ed issuance of or changes in laws and regulations.” Based

on new evidence of corruption in the judiciary, Poland’s

property rights score is 1 point worse this year.

REGULATION

Score:

3–Stable

(moderate level)

According to the U.S. Department of State, “The government

acknowledges that its policies are not as transparent as they

ought to be and that bureaucratic requirements continue to

impose a burden on investors.… [U]neven and unpredictable

regulatory treatment and a generally high level of adminis-

trative ‘red tape’ are recurring complaints of investors….” In

addition, “investors must comply with a variety of laws con-

cerning…taxation, labor practices, health and safety, and the

environment. Complaints about these laws, especially the tax

system, center on the lack of clarity and often-draconian

penalties for minor errors.”

INFORMAL MARKET

Score:

3.5–Stable

(high level of activity)

Transparency International’s 2001 score for Poland is 4.

Therefore, Poland’s informal market score is 3.5 this year.

332

2004 Index of Economic Freedom

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Education in Poland

Kodeks Etyki ICOM poland

poland07 Medycyna komórkowa

Introduction to Lean for Poland

Instrukcja IEF Algorytmy i struktury danych lab2

DIMENSIONS OF INTEGRATION MIGRANT YOUTH IN POLAND

Hinduizm made in Poland, EDUKACJA różne...)

Lecture POLAND Competitiv2008

pdf poland pilkington

cw 7 skrypt fizjo ifmsa poland

Poland and?lsifications of Polish History

Images of Poland

The Solidarity movement in Poland

The?ginning of World War II German Invasion of Poland

Chopin Poland's Greatest Composer

Lekturki, Internet in Poland - Lekturka

więcej podobnych podstron