10

C H A P T E R

C

O N S U M E R

C

H O I C E

T

H E O R Y

C

O N S U M E R

C

H O I C E

T

H E O R Y

10.1

Consumer Behavior

10.2

The Consumer’s Choice

APPENDIX:

A More Advanced Theory of Consumer

Choice

n this chapter, we discuss how individuals allocate

their income between different bundles of goods.

This decision involves trade-offs—if you buy more

of one good, you cannot afford as much of other

goods. Why do consumers buy more of a product

when the price falls and less of a product when the

price rises? How do consumers respond to rising

income? Falling income? How do we as consumers

choose certain bundles of goods with our available

budget to fit our desires? We address these questions

in this chapter to strengthen our understanding of

the law of demand.

■

I

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:03 PM Page 243

244

M O D U L E 3

Households, Firms, and Market Structure

As you may recall from Chapter 4, the law of demand

is intuitive. Put simply, at a higher price, consumers

will buy less (a decrease in the quantity demanded); at

a lower price, consumers will buy more (an increase

in quantity demanded), ceteris paribus. However, the

downward-sloping demand curve has three other

explanations: (1) the income and substitution effects

of a price change, (2) the law of diminishing marginal

utility, and (3) an interpretation using indifference

curves and budget lines (in the appendix).

Let’s start with out first explanation of a downward-

sloping demand curve—the substitution and income

effects of a price change. For example, if the price of

pizza increases, the quantity of pizza demanded will fall

because some consumers might switch out of pizza

into hamburgers, tacos, burritos, submarine sandwiches,

or some other foods that

substitute for pizza.

This behavior is called

the

substitution effect

of a price change. In

addition, a price increase

for pizza will reduce

the quantity of pizza

demanded because it reduces a buyer’s purchasing

power. The buyer cannot buy as many pieces of pizza

at higher prices as she could at lower prices, which is

called the

income effect

of a price change.

The second explanation for the negative relation-

ship between price and quantity demanded is what

economists call

diminishing marginal utility.

In a

given time period, a buyer will receive less satisfaction

from each successive unit consumed. For example, a

second ice cream cone will yield less satisfaction than

the first, a third less sat-

isfaction than the second,

and so on. It follows

from diminishing mar-

ginal utility that if people

are deriving less satisfac-

tion from successive

units, consumers would

buy added units only if

the price were reduced.

Let’s now take a closer

look at utility theory.

UTILITY

To more clearly define the relationship between con-

sumer choice and resource allocation, economists

developed the concept of

utility

—a measure of the

relative levels of satis-

faction that consumers

get from the consump-

tion of goods and serv-

ices. Defining one

util

as equivalent to one

unit of satisfaction,

S E C T I O N

10.1

C o n s u m e r B e h a v i o r

■

What is the substitution effect?

■

What is the income effect?

■

Can we make interpersonal utility

comparisons?

■

What is diminishing marginal utility?

Economists conducted an experiment with rats to see how they

would respond to changing prices of different drinks (changing

the number of times a rat had to press a bar). Rats responded

by choosing more of the beverage with a lower price, showing

they were willing to substitute when the price changed. That is,

even rats seem to behave rationally—responding to incentives

and opportunities to make themselves better off.

substitution effect

a consumer’s switch to another simi-

lar good when the price of the pre-

ferred good increases

income effect

reduction in quantity demanded of

a good when its price increases

because of a consumer’s decreased

purchasing power

diminishing

marginal utility

a good’s ability to provide less satis-

faction with each successive unit

consumed

utility

a measure of the relative levels of

satisfaction consumers get from

consumption of goods and services

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:03 PM Page 244

C H A P T E R 1 0

Consumer Choice Theory

245

economists can indi-

cate relative levels

of consumer satisfac-

tion that result from

alternative choices.

For example, for a java junkie who wouldn’t dream

of starting the day without a strong dose of

caffeine, a cup of coffee might generate 150 utils

of satisfaction while a cup of herb tea might only

generate 10 utils.

Inherently, utility varies from individual to indi-

vidual depending on specific preferences. For exam-

ple, Jason might get 50 utils of satisfaction from

eating his first piece of apple pie, while Brittany may

only derive 4 utils of satisfaction from her first piece

of apple pie.

In fact, a whole school of thought called utilitar-

ianism, based on utility theory, was developed by

Jeremy Bentham. Bentham believed that society

should seek the greatest happiness for the greater

number (See Bentham’s biography below.).

UTILITY IS A PERSONAL MATTER

Economists recognize that it is not really possible to

make interpersonal utility comparisons. That is, they

know that it is impossible to compare the relative sat-

isfactions of different persons. The relative satisfactions

gained by two people drinking cups of coffee, for

example, simply cannot be measured in comparable

terms. Likewise, although we might be tempted to

believe that a poorer person would derive greater util-

ity from finding a $100 bill than would a richer person,

we should resist the temptation. We simply cannot

prove it. The poorer person may be “monetarily” poor

because money and material things are not important

to her, and the rich person may have become richer

because of his lust for the things money can buy.

util

one unit of satisfaction

g r e a t e c o n o m i c t h i n k e r s

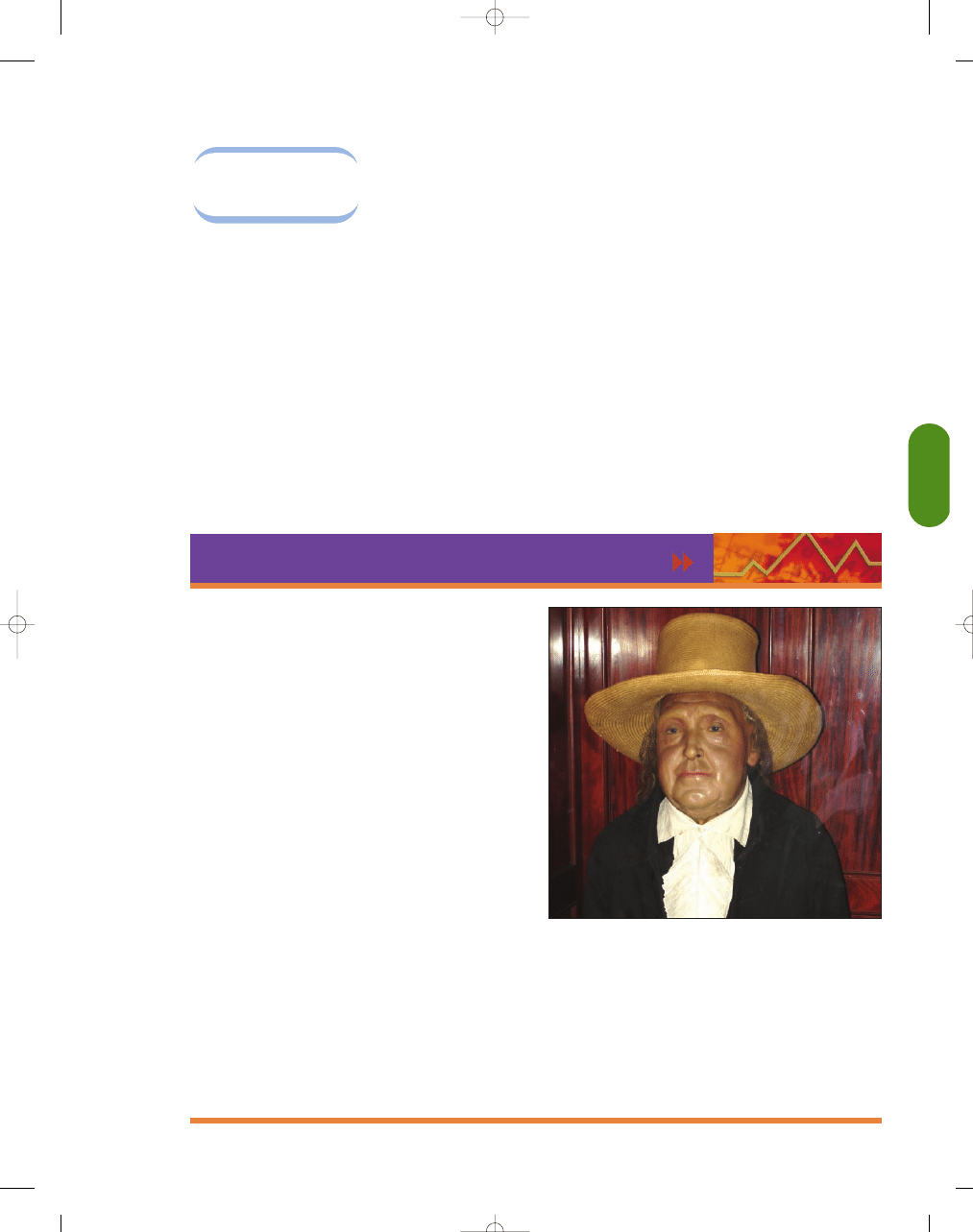

Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832)

Jeremy Bentham was born in London in 1748. He was a gifted child, reading his-

tory and other “serious” books at age 3, playing the violin at age 5, and study-

ing Latin and French when he was only 6. At 12, he entered Queens College,

Oxford, where he studied law. In his late teens, Bentham decided to concen-

trate on his writings. With funding provided by his father, he wrote a series of

books on philosophy, economics, and politics. He would often write for 8 to

12 hours a day, a practice that continued through his life, leaving scholars

material to compile for years to come. Most of his writings were not pub-

lished until well over a century after his death.

According to Bentham, “pain and pleasure are the sovereign masters gov-

erning man’s conduct”: People will tend to pursue things that are pleasurable

and avoid things that are painful. To this day, the rule of rational choice—

weighing marginal benefits against marginal costs—has its roots in the earlier

works of Jeremy Bentham. That is, economists predict human behavior on the

basis of people’s responses to changing incentives; people make choices on the

basis of their expected marginal benefits and their expected marginal costs.

Although Bentham was most well known for utilitarianism, a philosophy

stemming from his rational-choice ideas, he also had much to say on the sub-

jects of prison reform, religion, relief to the poor, international law, and

animal welfare. He was an ardent advocate of equality. Good humored, med-

itative, and kind, he was thought to be a visionary and ahead of his time, and

he attracted the leading thinkers of the day to his company.

Bentham died in London in 1832. He left behind a strange legacy. At his

request, his body was dissected, his skeleton padded and fully clothed, and his

head preserved in the manner of South American headhunters. He asked that

this “auto-icon,” as it is now called, be seated in a glass case at the University

College in London, and that his remains should be present at all meetings for

the board. The auto-icon is still there today, although the mummified head,

which did not preserve well, has been replaced by a wax head. The real head

became an easy target for students and one story has the head being used at

soccer practice! No one is quite sure why Bentham desired such an odd after-

life for his body; explanations range from it being a testament to an inflated

sense of self-worth to a statement about religion or a practical joke.

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:03 PM Page 245

246

M O D U L E 3

Households, Firms, and Market Structure

TOTAL UTILITY AND MARGINAL UTILITY

Economists recognize two different dimensions of

utility: total utility and marginal utility.

Total utility

is the total amount of satisfaction derived from the

consumption of a certain number of units of a good

or service. In comparison,

marginal utility

is the

extra satisfaction generated by an additional unit of a

good that is consumed

in a particular time

period. For example,

eating four slices of

pizza in an hour might

generate a total of 28

utils of satisfaction.

The first three slices of

pizza might generate a

total of 24 utils, while

the last slice generates

only 4 utils. In this case,

the total utility of eating four slices of pizza is 28 utils,

and the marginal utility of the fourth slice is 4 utils.

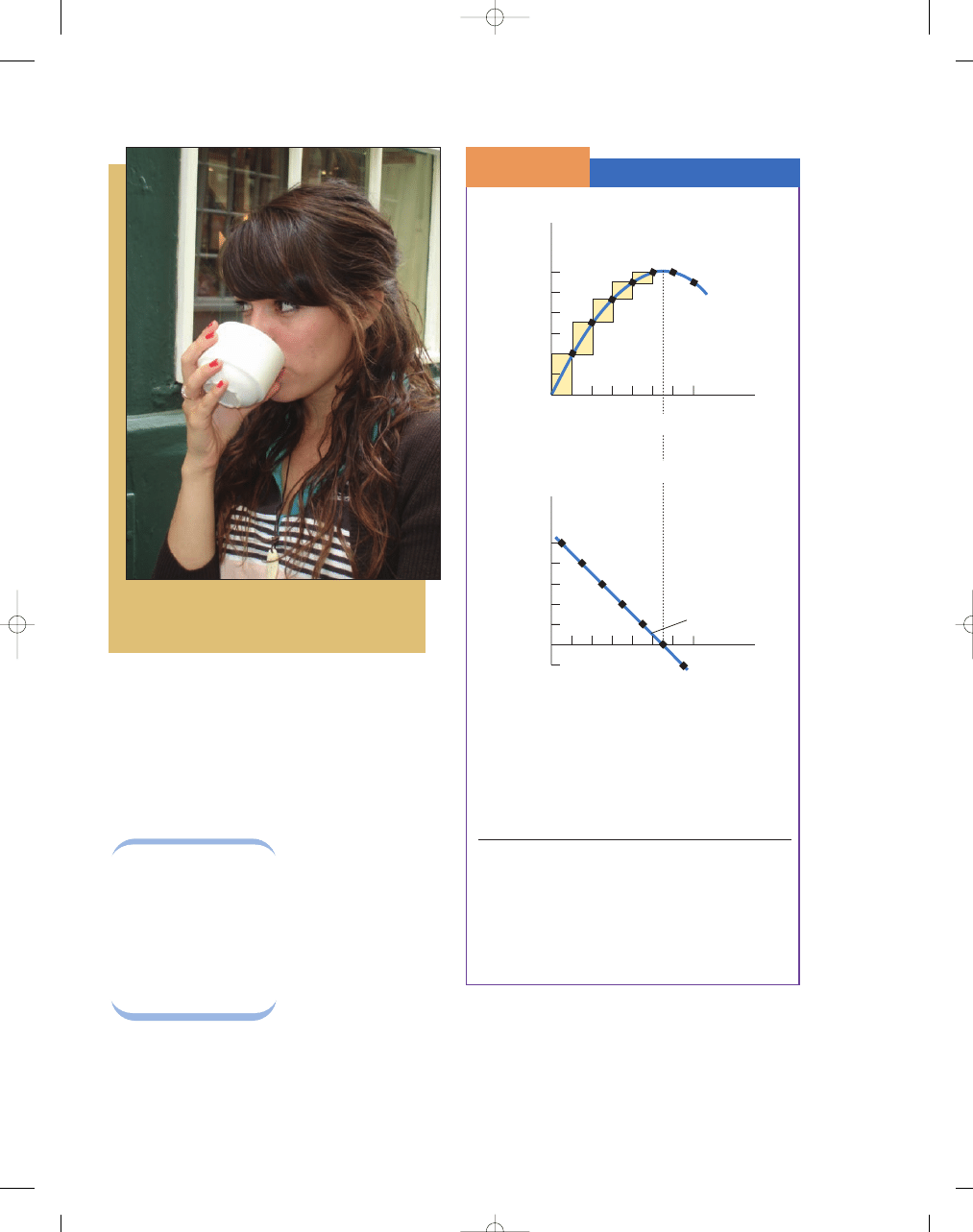

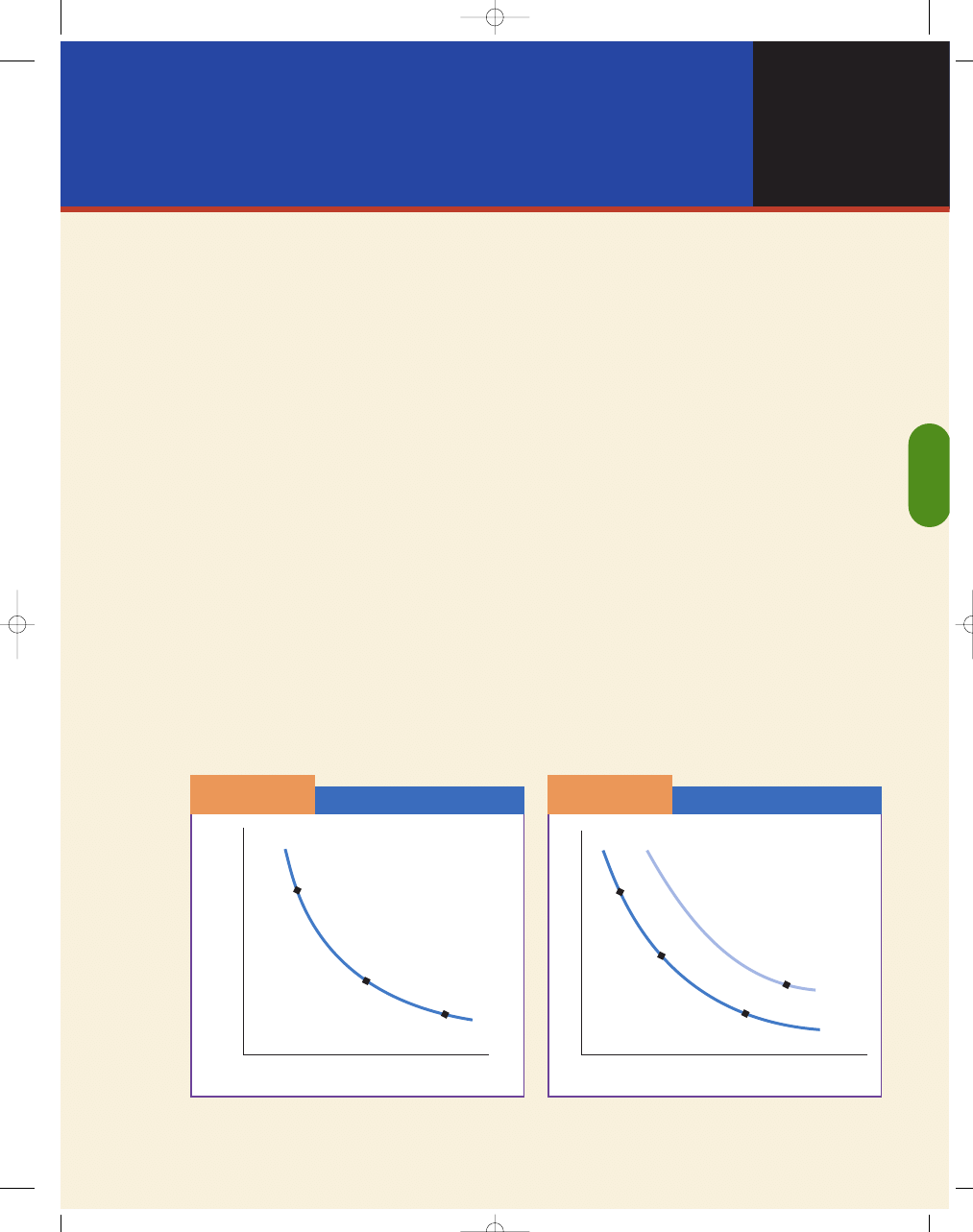

Notice in Exhibit 1(a) how total utility increases as

consumption increases (we see more total utility after

the fourth slice of pizza than after the third). But

notice, too, that the increase in total utility from each

additional unit (slice) is less than the unit before,

which indicates the marginal utility. In Exhibit 1(b)

we see how the marginal utility falls as consumption

increases.

How many utils is she deriving from this cup of coffee? Can we

accurately compare her satisfaction of a cup of coffee with

another person’s?

total utility

total amount of satisfaction derived

from the consumption of a certain

number of goods or services

marginal utility

extra satisfaction generated by con-

sumption of an additional good or

service during a specific time period

Total and Marginal Utility

S E C T I O N

1 0 .1

E

X H I B I T

1

As you can see in a, the total utility from pizza

increases as consumption increases. In b marginal util-

ity decreases as consumption increases. That is, as you

eat more pizza, your satisfaction from each additional

slice diminishes.

Slices of Pizza

Total Utility

Marginal Utility

(per day)

(utils)

(utils)

0

0

1

10

10

2

18

8

3

24

6

4

28

4

5

30

2

6

30

0

7

28

−2

1

10

20

30

2

3

4

5

Total

Utility

Marginal Utility

T

otal Utility (utils)

Q

6

7

5

2

Mar

ginal Utility (utils)

0

0

–2

1

2

4

6

8

10

3

4

6

7

a. Total Utility

b. Marginal Utility

Pizza Slices (consumed per hour)

Q

Pizza Slices (consumed per hour)

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:03 PM Page 246

C H A P T E R 1 0

Consumer Choice Theory

247

DIMINISHING MARGINAL UTILITY

Although economists believe that total utility

increases with additional consumption, they also

argue that the incremental satisfaction—the marginal

utility—that results from the consumption of addi-

tional units tends to decline as consumption increases.

In other words, each successive unit of a good that is

consumed generates less satisfaction than did the pre-

vious unit. This concept is traditionally referred to as

the

diminishing marginal utility.

Exhibit 1(b)

demonstrates this graphically, where the marginal

utility curve has a negative slope.

It follows from the

law of diminishing mar-

ginal utility that as a

person uses more and

more units of a good to

satisfy a given want, the

intensity of the want,

and the utility derived

from further satisfying

that want, diminishes. Think about it: If you are starv-

ing, your desire for that first piece of pizza will be great,

but as you eat, you gradually become more and more

full, reducing your desire for yet another piece.

diminishing

marginal utility

the concept that states that as an

individual consumes more and

more of a good, each successive

unit generate less and less utility

(or satisfaction)

using what you’ve learned

Diminishing Marginal Utility

Why do most individuals take only one newspaper from covered,

coin-operated newspaper racks when it would be so easy to take

more? Do you think potato chips, candy, or sodas could be sold profitably in

the same kind of dispenser? Why or why not?

Although ethical considerations keep some people from taking

additional papers, the law of diminishing marginal utility is also

at work here. The second newspaper adds practically zero utility to most

individuals on most days, so they typically feel no incentive to take more

than one. The exception to this case might be on Sundays, when supermar-

ket coupons are present. In that instance, while the marginal utility is still

lower for the second paper than for the first, the marginal utility of the

second paper may be large enough to tempt some individuals to take addi-

tional copies.

On the other hand, if putting money in a vending machine gave access

to many bags of potato chips, candy bars, or sodas, the temptation to take

more than one might be too great for some people. After all, the potato

chip bags would still be good tomorrow. Therefore, vending machines with

foods and drinks only dispense one item at a time, because it is likely that,

for most people, the marginal utility gained from another unit of food or

drink is higher than for a second newspaper.

Q

A

©

Dennis MacDonald/PhotoEdit

Why are newspaper racks different from vending machines?

using what you’ve learned

The Diamond-Water Paradox:

Marginal and Total Utility

“Nothing is more useful than water: but it will not purchase scarce any-

thing. . . . Diamond, on the contrary, has scarce any value in use; but a very

great quantity of other goods may frequently be had in exchange for it.”

—Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations, 1776

Use the concept of marginal utility to evaluate the social value of

water versus diamonds.

The classic diamond-water paradox is the observation that some-

times those things that are necessary for life, like water, are inex-

pensive, and those items that are not necessary for life, like diamonds, are

expensive. This paradox puzzled philosophers for centuries. The answer

Q

A

(continued)

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:03 PM Page 247

248

M O D U L E 3

Households, Firms, and Market Structure

using what you’ve learned (cont.)

lies in making the distinction between total utility and marginal utility.

The amount of total utility is indeed higher for water than for diamonds

because of its importance for survival. But price is not determined by

total utility, it is determined by marginal utility. Total utility measures the

total amount of satisfaction someone derives from a good, whereas mar-

ginal utility determines the price. Market value—the value of the last, or

marginal, unit traded—depends on both supply and demand. Thus, the

limited supply of diamonds relative to the demand generates a high price,

but an abundant supply of water relative to the demand results in a low

price. The total utility (usefulness) for water is very large compared to the

marginal utility. Because the price of water is so low, we use so much

water that the marginal utility we receive from the last glass of water is

small. Diamonds have a much smaller total utility (usefulness) relative to

water, but because the price of diamonds is so high, we buy so few dia-

monds they have a high marginal utility. Could water ever have a higher

marginal utility than diamonds? Yes, if you had no water and no dia-

monds, your first cup of water would give you a much higher marginal

value than your first cup of diamonds. Furthermore, what if diamonds

were very plentiful and water was very scarce, which would have the

higher marginal utility? In this case, water would be expensive and dia-

monds would be inexpensive.

Why is water, which is so critical to life, priced lower than diamonds

which are less useful?

©

PhotoDisc Green/Getty Imeges

, Inc.

S E C T I O N

*

C H E C K

1.

A substitution effect occurs when a consumer switches to another similar good when the price of the preferred

good increases.

2.

The income effect occurs when there is a reduction in quantity demanded of a good when its price increases

because of a consumer’s decreased purchasing power.

3.

Utility is the amount of satisfaction an individual receives from consumption of a good or service.

4.

Economists recognize that it is not possible to make interpersonal utility comparisons.

5.

Total utility is the amount of satisfaction derived from all units of goods and services consumed. Total

utility increases as consumption increases.

6.

Marginal utility is the change in utility from consuming one additional unit of a good

or service.

7.

According to the law of diminishing marginal utility, as a person consumes additional units of a given

good, marginal utility declines.

1.

What is the substitution effect of a price change?

2.

What is the income effect of a price change?

3.

How do economists define utility?

4.

Why can’t interpersonal utility comparisons be made?

5.

What is the relationship between total utility and marginal utility?

6.

Why could you say that a millionaire gets less marginal utility from a second piece of pizza than from

the first piece, but you couldn’t say that the millionaire derives more or less marginal utility from a second

piece of pizza than someone else who has a much lower level of income?

7.

Are you likely to get as much marginal utility from your last piece of chicken at an all-you-can-eat restaurant as at

a restaurant where you pay $2 per piece of chicken?

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:04 PM Page 248

C H A P T E R 1 0

Consumer Choice Theory

249

WHAT IS THE “BEST” DECISION FOR CONSUMERS?

We established the fact that marginal utility dimin-

ishes as additional units of a good are acquired. But

what significance does this idea have for consumers?

Remember, consumers try to add to their own total

utility, so when the marginal utility generated by the

purchase of additional units of one good drops too

low, it can become rational for the consumer to pur-

chase other goods rather than purchase more of the

first good. In other words, a rational consumer will

avoid making purchases of any one good beyond the

point at which other goods will yield greater satisfac-

tion for the amount spent—the “bang for the buck.”

Marginal utility, then, is an important concept in

understanding and predicting consumer behavior, espe-

cially when combined with information about prices. By

comparing the marginal utilities generated by units of

the goods that they desire as well as the prices, rational

consumers seek the combination of goods that maxi-

mizes their satisfaction for a given amount spent. In the

next section, we will see how this concept works.

CONSUMER EQUILIBRIUM

To reach consumer equilibrium, consumers must allo-

cate their incomes in such a way that the marginal util-

ity per dollar’s worth of any good is the same for every

good. That is, the “bang for the buck” must be equal

for all goods at consumer equilibrium. When this goal

is realized, one dollar’s worth of additional gasoline

will yield the same marginal utility as one dollar’s

worth of additional bread or apples or movie tickets

or soap. This concept will become clearer to you as we

work through an example illustrating the forces pres-

ent when consumers are not at equilibrium.

Given a fixed budget, if the marginal utilities per

dollar spent on additional units of two goods are not

the same, you can increase total satisfaction by

buying more of one good and less of the other. For

example, assume that the price of a loaf of bread is

$1, the price of a bag of apples is $1, the marginal

utility of a dollar’s worth of apples is 1 util, and the

marginal utility of a dollar’s worth of bread is 5 utils.

In this situation, your total satisfaction can be

increased by buying more bread and fewer apples,

because bread is currently giving you greater satisfac-

tion per dollar than apples—5 utils versus 1 util, for a

net gain of 4 utils to your total satisfaction. By buying

more bread, though, you alter the marginal utility of

both bread and apples. Consider what would happen

if, next week, you buy one more loaf of bread and one

less bag of apples. Because you are consuming more

of it now, the marginal utility for bread will fall, say

to 4 utils. On the other hand, the marginal utility for

apples will rise, perhaps to 2 utils, because you now

have fewer apples.

A comparison of the marginal utilities for these

goods in week 2 versus week 1 would look something

like this:

Week 1

MU

bread

/$1

> MU

apples

/$1

5 utils/$1

> 1 util/$1

Week 2

MU

bread

/$1

> MU

apples

/$1

4 utils/$1

> 2 utils/$1

Notice that although the marginal utilities of bread

and apples are now closer, they are still not equal.

Because of this difference, it is still in the consumer’s

interest to purchase an additional loaf of bread rather

than the last bag of apples; in this case, the net gain

would be 2 utils (3 utils for the unit of bread added at

a cost of 1 util for the apples given up). By buying yet

another loaf of bread, you once again push further

down your marginal utility curve for bread, and as a

result, the marginal utility for bread falls. With that

change, the relative value to you of apples increases

again, changing the ratio of marginal utility to dollar

spent for both goods in the following way:

Week 3

MU

bread

/$1

= MU

apples

/$1

3 utils/$1

= 3 utils/$1

S E C T I O N

10.2

T h e C o n s u m e r ’s C h o i c e

■

How do consumers maximize satisfaction?

■

What is the connection between the law

of demand and the law of diminishing

marginal utility?

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:04 PM Page 249

250

M O D U L E 3

Households, Firms, and Market Structure

What this example shows is that, to achieve

maximum satisfaction—

consumer equilibrium

—

consumers have to allocate income in such a way that

the ratio of the mar-

ginal utility to the price

of the goods is equal

for all goods pur-

chased. In other words,

in a state of consumer

equilibrium,

MU

1

/P

1

= MU

2

/P

2

= MU

3

/P

3

= . . . MU

N

/P

N

In this situation, each good provides the consumer

with the same level of marginal utility per dollar spent.

THE LAW OF DEMAND AND THE LAW

OF DIMINISHING MARGINAL UTILITY

The law of demand states that when the price of a

good is reduced, the quantity of that good

demanded will increase. But why is this the case? By

examining the law of diminishing marginal utility in

action, we can determine the basis for this relation-

ship between price and quantity demanded. Indeed,

the demand curve merely translates marginal utility

into dollar terms.

For example, let’s say that you are in consumer

equilibrium when the price of a personal-sized pizza is

$4 and the price of a hamburger is $1. Further, in

equilibrium, the marginal utility on the last pizza con-

sumed is 40 utils, and the marginal utility on the last

hamburger is 10 utils. So in consumer equilibrium,

the MU/P ratio for both the pizza and the hamburger

is 10 utils per dollar:

MU

pizza

(40 utils)/$4

= MU

hamburger

(10 utils)/$1

Now suppose the price of the personal-sized

pizza falls to $2, ceteris paribus. Instead of the

MU/P ratio of the pizza being 10 utils per dollar, it

is now 20 utils per dollar (40 utils/$2). This calcula-

tion implies, ceteris paribus, that you will now buy

more pizza at the lower price because you are getting

relatively more satisfaction for each dollar you

spend on pizza.

MU

pizza

(40 utils)/$2

> MU

hamburger

(10 utils)/$1

In other words, because the price of the personal-

sized pizza fell, you are now willing to purchase more

pizzas and fewer hamburgers.

using what you’ve learned

Marginal Utility

A consumer is faced with choosing between hamburgers and milkshakes

that are priced at $2 and $1, respectively. He has $11 to spend for the week.

The marginal utility derived from each of the two goods is as follows:

If you did not have a budget constraint, you would choose 5 hamburg-

ers and 5 milkshakes because you would maximize your total utility (68

+

34

= 102); that is, adding up all the marginal utilities for all hamburgers (68

utils) and all milkshakes (34 utils). And that would cost you $15; $10 for the

5 hamburgers and $5 for the 5 milkshakes. However, you can only spend $11;

so what is the best way to spend it? Remember economic decisions are

made at the margin. This idea is the best “bang for the buck” principle, we

must equalize the marginal utility per dollar spent. Looking at the table, we

accomplish this at 4 hamburgers and 3 milkshakes per week.

Or

MU

H

/P

H

= MU

M

/P

H

10/$2

= 5/$1

(Q

H

× P

H

)

+ (Q

M

× P

M

)

= $11

(4

× $2) + (3 × $1) = $11

Marginal Utility from

Quantity of Hamburgers

Last Hamburger

Consumed Each Week

(MU

H

/P

H

)

20

1

10

16

2

8

14

3

7

10

4

5

8

5

4

Marginal Utility from

Quantity of Milkshakes

Last Milkshake

Consumed Each Week

(MU

M

/P

M

)

12

1

12

10

2

10

5

3

5

4

4

4

3

5

3

consumer

equilibrium

allocation of consumer income that

balances the ratio of marginal util-

ity to the price of goods purchased

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:04 PM Page 250

C H A P T E R 1 0

Consumer Choice Theory

251

C H A P T E R 1 0

Consumer Choice Theory

i n t h e n e w s

Behavioral Economics

Today there is a growing school of economists who are drawing on a vast range

of behavioural traits identified by experimental psychologists which amount

to a frontal assault on the whole idea that people, individually or as a group,

mostly act rationally.

A quick tour of the key observations made by these psychologists would

make even Mr Spock’s head spin. For example, people appear to be dispro-

portionately influenced by the fear of feeling regret, and will often pass up

even benefits within reach to avoid a small risk of feeling they have failed.

They are also prone to cognitive dissonance: holding a belief plainly at odds

with the evidence, usually because the belief has been held and cherished for

a long time. Psychiatrists sometimes call this “denial”.

And then there is anchoring: people are often overly influenced by outside

suggestion. People can be influenced even when they know that the suggestion

is not being made by someone who is better informed. In one experiment, vol-

unteers were asked a series of questions whose answers were in percentages—

such as what percentage of African countries is in the United Nations? A wheel

with numbers from one to 100 was spun in front of them; they were then asked

to say whether their answer was higher or lower than the number on the wheel,

and then to give their answer. These answers were strongly influenced by the

randomly selected, irrelevant number on the wheel. The average guess when the

wheel showed 10 was 25%; when it showed 65 it was 45%.

Experiments show that most people apparently also suffer from status

quo bias: they are willing to take bigger gambles to maintain the status quo

than they would be to acquire it in the first place. In one common experiment,

mugs are allocated randomly to some people in a group. Those who have them

are asked to name a price to sell their mug; those without one are asked to

name a price at which they will buy. Usually, the average sales price is consid-

erably higher than the average offer price.

Expected-utility theory assumes that people look at individual decisions

in the context of the big picture. But psychologists have found that, in fact,

they tend to compartmentalise, often on superficial grounds. They then

make choices about things in one particular mental compartment without

taking account of the implications for things in other compartments.

There is also a huge amount of evidence that people are persistently, and

irrationally, over-confident. Asked to answer a factual question, then asked to

give the probability that their answer was correct, people typically overestimate

this probability. This may be due to a representativeness heuristic: a tendency

to treat events as representative of some well-known class or pattern. This gives

people a sense of familiarity with an event and thus confidence that they have

accurately diagnosed it. This can lead people to “see” patterns in data even where

there are none. A closely related phenomenon is the availability heuristic:

people focus excessive attention on a particular fact or event, rather than the big

picture, simply because it is more visible or fresher in their mind.

Another delightfully human habit is magical thinking: attributing to one’s

own actions something that had nothing to do with them, and thus assuming that

one has a greater influence over events than is actually the case. For instance, an

investor who luckily buys a share that goes on to beat the market may become

convinced that he is a skilful investor rather than a merely fortunate one. He may

also fall prey to quasi-magical thinking—behaving as if he believes his thoughts

can influence events, even though he knows that they can’t.

Most people, say psychologists, are also vulnerable to hindsight bias:

once something happens, they overestimate the extent to which they could

have predicted it. Closely related to this is memory bias: when something hap-

pens people often persuade themselves that they actually predicted it, even

when they didn’t.

Finally, who can deny that people often become emotional, cutting off

their noses to spite their faces. One of the psychologists’ favourite experi-

ments is the “ultimatum game” in which one player, the proposer, is given a

sum of money, say $10, and offers some portion of it to the other player, the

responder. The responder can either accept the offer, in which case he gets the

sum offered and the proposer gets the rest, or reject the offer in which case

both players get nothing. In experiments, very low offers (less than 20% of the

total sum) are often rejected, even though it is rational for the responder to

accept any offer (even one cent!) which the proposer makes. And yet respon-

ders seem to reject offers out of sheer indignation at being made to accept

such a small proportion of the whole sum, and they seem to get more satis-

faction from taking revenge on the proposer than in maximising their own

financial gain. Mr Spock would be appalled if a Vulcan made this mistake.

The psychological idea that has so far had the greatest impact on eco-

nomics is “prospect theory”. This was developed by Daniel Kahneman of

Princeton University and the late Amos Tversky of Stanford University. It

brings together several aspects of psychological research and differs in crucial

respects from expected-utility theory—although, equally crucially, it shares

its advantage of being able to be modelled mathematically. It is based on the

results of hundreds of experiments in which people have been asked to

choose between pairs of gambles.

What Messrs Kahneman and Tversky claim to have found is that people are

“loss averse”: they have an asymmetric attitude to gains and losses, getting less

utility from gaining, say, $100 than they would lose if they lost $100. This is not

the same as “risk aversion”, any particular level of which can be rational if con-

sistently applied. But those suffering from loss aversion do not measure risk

consistently. They take fewer risks that might result in suffering losses than if

they were acting as rational utility maximisers. Prospect theory also claims that

people regularly miscalculate probabilities: they assume that outcomes which

are very probable are less likely than they really are, that outcomes which are

quite unlikely are more likely than they are, and that extremely improbable, but

still possible, outcomes have no chance at all of happening. They also tend to

view decisions in isolation, rather than as part of a bigger picture.

Several real-world examples of how this theory can explain human deci-

sions are reported in a forthcoming paper, “Prospect Theory in the Wild”, by

Colin Camerer, an economist at the California Institute of Technology∗. Many

New York taxi drivers, points out Mr Camerer, decide when to finish work

each day by setting themselves a daily income target, and on reaching it they

stop. This means that they typically work fewer hours on a busy day than on

(continued)

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:04 PM Page 251

252

M O D U L E 3

Households, Firms, and Market Structure

i n t h e n e w s ( c o n t . )

a slow day. Rational labour-market theory predicts that they will do the

opposite, working longer on the busy day when their effective hourly wage-

rate is higher, and less on the slow day when their wage-rate is lower. Prospect

theory can explain this irrational behaviour: failing to achieve the daily

income target feels like incurring a loss, so drivers put in longer hours to avoid

it, and beating the target feels like a win, so once they have done that, there

is less incentive to keep working.

RACING AND THE EQUITY PREMIUM

People betting on horse races back long-shots over favourites far more often

than they should. Prospect theory suggests this is because they attach too low

a probability to likely outcomes and too high a probability to quite unlikely

ones. Gamblers also tend to shift their bets away from favourites towards

long-shots as the day’s racing nears its end. Because of the cut taken by the

bookies, by the time later races are run most racegoers have lost some money.

For many of them, a successful bet on an outsider would probably turn a

losing day into a winning one. Mathematically, and rationally, this should not

matter. The last race of the day is no different from the first race of the next

day. But most racegoers close their “mental account” at the end of each racing

day, and they hate to leave the track a loser.

Perhaps the best-known example of prospect theory in action is in sug-

gesting a solution to the “equity-premium puzzle”. In America, shares have long

delivered much higher returns to investors relative to bonds than seems justi-

fied by the difference in riskiness of shares and bonds. Orthodox economists

have ascribed this simply to the fact that people have less appetite for risk than

expected. But prospect theory suggests that if investors, rather like racegoers,

are averse to losses during any given year, this might justify such a high equity

premium. Annual losses on shares are much more frequent than annual losses on

bonds, so investors demand a much higher premium for holding shares to com-

pensate them for the greater risk of suffering a loss in any given year.

A common response of believers in homo economicus is to claim that

apparently irrational behaviour is in fact rational. Gary Becker, of the

University of Chicago, was doing this long before behavioural economics came

along to challenge rationality. He has won a Nobel prize for his work, which

has often shed light on topics from education and family life to suicide, drug

addiction and religion. Recently, he has developed “rational” models of the

formation of emotions and of religious belief.

Rationalists such as Mr Becker often accuse behaviouralists of picking

whichever psychological explanation happens to suit the particular alleged

irrationality they are explaining, rather than using a rigorous, consistent sci-

entific approach. Caltech’s Mr Camerer argues that rationalists are guilty of

exactly the same error. For instance, rationalists explain away people’s fond-

ness for betting on long-shots in horse races by claiming that most are simply

more risk-loving than expected, and then claim precisely the opposite about

investors to explain the equity premium. Both are possible, but as explana-

tions they leave something to be desired.

Being irrational may even be rational, according to some rationalists.

Irrationality can be a good to be consumed like any other, argues Bryan Caplan, an

economist at George Mason University—in the sense that the less it costs a person,

the more of it they buy. A peculiar feature of beliefs about politics and religion, he

says, is that the costs to an individual of error are “virtually non-existent, setting

the private cost of irrationality at zero; it is therefore in these areas that irrational

views are most apparent.” Maybe, although Mr Caplan may grow sick of having

those views read back to him for eternity should he ever end up in hell.

In his book, “Alchemies of the Mind: Rationality and the Emotions”, Jon

Elster of New York’s Columbia University prefers to look at the other side of

the same coin. Observing that “those who are most likely to make unbiased

cognitive assessments are the clinically depressed,” he argues that the “emo-

tional price to pay for cognitive rationality may be too high.”

In fact, the battle between rationalists and behaviouralists may be

largely in the past. Those who believe in homo economicus no longer rou-

tinely ignore his emotional and spiritual dimensions. Nor do behaviouralists

any longer assume people are wholly irrational. Instead, most now view them

as “quasi-rational”: trying as hard as they can to be rational but making the

same mistakes over and over.

Robert Shiller, an economist at Yale who is writing a book on psychology

and the stockmarket, and is said to have prompted Mr Greenspan’s “irrational

exuberance” remark, argues that “conventional efficient-markets theory is

not completely out the window . . . Doing research that is sensitive to lessons

from behavioural research does not mean entirely abandoning research in the

conventional expected-utility framework.”

Mr Kahneman, the psychologist who inspired much of the economic

research on irrationality, goes further: “as a first approximation, it makes

sense to assume rational behaviour.” He believes that economists cannot give

up the rational model entirely. “They will be doing it one assumption at a

time. Otherwise the analysis will very soon become intractable; the great

strength of the rational model is that it is very tractable.”

RATIONAL TAXI DRIVERS!

What seems certain is that economics will increasingly embrace the insights

of other disciplines, from psychologists to biologists. Andrew Lo, an econo-

mist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is hopeful that natural scien-

tists will help social scientists by discovering the genetic basis for different

attitudes to risk-taking. Considerable attention will be paid to discoveries

about how people form their emotions, tastes and beliefs. Understanding

better how people learn will also be a priority. Strikingly, even New York taxi

drivers seem to become less irrational over time: with experience, they learn

to do more work on busy days and less when things are slow. But how repre-

sentative are they of the rest of humanity?

Richard Thaler was an almost lone pioneer in the use of psychology in

financial economics during the 1980s and early 1990s. Today he is a professor

at the University of Chicago, the high temple of rational economics. He

believes that in future, “economists will routinely incorporate as much

‘behaviour’ into their models as they observe in the real world. After all, to do

otherwise would be irrational.” Mr Spock could not have said it better.

SOURCE: “Rethinking Thinking,” The Economist, 16 December 1999. © The Economist

Newspaper, Ltd. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission. Further reproduc-

tion prohibited. Http://www.economist.com.

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:04 PM Page 252

C H A P T E R 1 0

Consumer Choice Theory

253

C H A P T E R 1 0

Consumer Choice Theory

I n t e r a c t i v e S u m m a r y

Fill in the blanks:

1. The _____________ effect explains why the quantity

of pizza demanded decreases as its price goes up,

because some people switch to substitute goods that

become relatively cheaper as a result.

2. The _____________ effect explains why the quantity

of pizza demanded decreases as its price goes up,

because it reduces buyers’ purchasing power.

3. _____________ utility implies that people will derive

less satisfaction from successive units.

4. You would expect a third ice cream cone to

provide _____________ additional utility, or satisfac-

tion, on a given day, than the second ice cream cone

the same day.

5. _____________ is the satisfaction or enjoyment

derived from consumption.

6. The relative satisfaction gained by two people drink-

ing cups of coffee _____________ be measured in

comparable terms.

7. _____________ is the total amount of satisfaction

derived from the consumption of a certain number of

units of a good.

8. _____________ utility is the extra satisfaction gener-

ated by an additional unit of a good that is consumed

in a given time period.

9. If the first of three slices of pizza generates 24 utils

and four slices of pizza generates 28 utils, then the

marginal utility of the fourth slice of pizza is

_____________ utils.

10. Marginal utility _____________ as consumption

increases, which is called the law of _____________.

11. Market prices of goods and services are determined

by _____________ utility.

12. If total utility fell for consuming one more unit of

a good, the marginal utility for that good would

be _____________.

13. To reach _____________, consumers must allocate

their incomes in such a way that the marginal utility

per dollars’ worth of any good is the same for every

good.

14. If the last dollar spent on good A provides

more marginal utility per dollar than the last

dollar spent on good B, total satisfaction would

increase if _____________ was spent on good A

and _____________ was spent on good B.

15. As an individual approaches consumer equilibrium,

the ratio of marginal utility per dollar spent on

different goods gets ____________ apart across goods.

16. In consumer equilibrium, if the price of a good A is

three times that of the price of good B, then the

S E C T I O N

*

C H E C K

1.

To maximize consumer satisfaction, income must be allocated so that the ratio of the marginal utility to the price

is the same for all goods purchased.

2.

If the marginal utility per dollar of additional units is not the same, a person can increase total satisfaction by

buying more of some goods and less of others.

1.

What do economists mean by consumer equilibrium?

2.

How could a consumer raise his total utility if the ratio of his marginal utility to the price for good A was greater

than that for good B?

3.

What must be true about the ratio of marginal utility to the price for each good consumed in consumer

equilibrium?

4.

How does the law of demand reflect the law of diminishing marginal utility?

5.

Why doesn’t consumer equilibrium imply that the ratio of total utility per dollar is the same for

different goods?

6.

Why does the principle of consumer equilibrium imply that people would tend to buy more apples when

the price of apples is reduced?

7.

Suppose the price of walnuts is $6 per pound and the price of peanuts is $2 per pound. If a person

gets 20 units of added utility from eating the last pound of peanuts she consumes, how many utils

of added utility would she have to get from eating the last pound of walnuts in order to be in

consumer equilibrium?

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:04 PM Page 253

254

M O D U L E 3

Households, Firms, and Market Structure

marginal utility from the last unit of good A will

be _____________ times the marginal utility from the

last unit of good B.

17. Starting in consumer equilibrium, when the price of

good A falls, it makes the marginal utility per dollar

spent on good A _____________ relative to that of

other goods, leading to a _____________ quantity of

good A purchased.

K e y Te r m s a n d C o n c e p t s

substitution effect 244

income effect 244

diminishing marginal utility 244

utility 244

util 245

total utility 246

marginal utility 246

diminishing marginal

utility 247

consumer equilibrium 250

S e c t i o n C h e c k A n s w e r s

10.1 Consumer Behavior

1. What is the substitution effect of a price change?

The substitution effect of a price change occurs when

a consumer switches to another similar good when

the price of the preferred good increases.

2. What is the income effect of a price change?

The income effect of a price change occurs when

there is a reduction in the quantity demanded of a

good when its price increases because of a consumer’s

decreased purchasing power.

3. How do economists define utility?

Economists define utility as the level of satisfaction or

well being an individual receives from consumption of

a good or service.

4. Why can’t interpersonal utility comparisons be made?

We can’t make interpersonal utility comparisons

because it is impossible to measure the relative satis-

faction of different people in comparable terms.

5. What is the relationship between total utility and

marginal utility?

Marginal utility is the increase in total utility from

increasing consumption of a good or service by one

unit.

6. Why could you say that a millionaire gets less mar-

ginal utility from a second piece of pizza than from

the first piece, but you couldn’t say that the millionaire

derives more or less marginal utility from a second

piece of pizza than someone else who has a much

lower level of income?

Both get less marginal utility from a second piece of

pizza than from the first piece because of the law of

diminishing marginal utility. However, it is impossi-

ble to measure the relative satisfaction of different

people in comparable terms, even when we are com-

paring rich and poor people, so we cannot say who

got more marginal utility from a second slice of

pizza.

7. Are you likely to get as much marginal utility from

your last piece of chicken at an all-you-can-eat restau-

rant as at a restaurant where you pay $2 per piece of

chicken?

No. If you pay $2 per piece, you only eat another

piece as long as it gives you more marginal utility

than spending the $2 on something else. But at an all-

you-can-eat restaurant, the dollar price of one more

piece of chicken is zero, so you consume more

chicken and get less marginal utility out of the last

piece of chicken you eat.

10.2 The Consumer’s Choice

1. What do economists mean by consumer equilibrium?

Consumer equilibrium means that a consumer is con-

suming the optimum, or utility maximizing, combina-

tion of goods and services, for a given level of income.

A

nswers: 1

. substitution

2.income

3.Diminishing marginal

4.less

5.Utility

6.cannot

7.T

otal utility

8.Marginal

9.4

10.declines; diminishing marginal utility

11.marginal

12.negative

13.consumer equilibrium

14.more; less

15.less far

16.three

17.rise; larger

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:04 PM Page 254

C H A P T E R 1 0

Consumer Choice Theory

255

2. How could a consumer raise his total utility if the

ratio of his marginal utility to the price for good A

was greater than that for good B?

Such a consumer would raise his total utility by spend-

ing less on good B, and more on good A, because a

dollar less spent on B would lower his utility less than

a dollar more spent on A would increase it.

3. What must be true about the ratio of marginal util-

ity to the price for each good consumed in consumer

equilibrium?

In consumer equilibrium, the ratio of marginal

utility to price for each good consumed must be

the same, otherwise the consumer could raise his

total utility by changing his consumption pattern

to increase consumption of those goods with higher

marginal utility per dollar and decrease consump-

tion of those goods with lower marginal utility

per dollar.

4. How does the law of demand reflect the law of dimin-

ishing marginal utility?

In consumer equilibrium, the marginal utility per

dollar spent is the same for all goods and services

consumed. Starting from that point, reducing the

price of one good increases its marginal utility per

dollar, resulting in increased consumption of that

good. But that is what the law of demand states—that

the quantity of a good demanded will increase, the

lower its price, ceteris paribus.

5. Why doesn’t consumer equilibrium imply that the ratio

of total utility per dollar is the same for different goods?

It is the additional, or marginal utility per dollar spent

for different goods, not the total utility you get per

dollar spent, that matters in determining whether con-

suming more of some goods and less of others will

increase total utility.

6. Why does the principle of consumer equilibrium

imply that people would tend to buy more apples

when the price of apples is reduced?

A fall in the price of apples will increase the marginal

utility per dollar spent on the last apple a person was

willing to buy before their price fell. This means a

person could increase his or her total utility for a

given income by buying more apples and less of some

other goods.

7. Suppose the price of walnuts is $6 per pound and

the price of peanuts is $2 per pound. If a person gets

20 units of added utility from eating the last pound

of peanuts she consumes, how many utils of added

utility would she have to get from eating the last

pound of walnuts in order to be in consumer

equilibrium?

Since consumer equilibrium requires that the marginal

utility per dollar spent must be the same across goods

that are consumed, the last pound of walnuts would

have to provide 60 units of added or marginal utility

in this case (60/6

= 20/2).

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:04 PM Page 255

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:04 PM Page 256

True or False

1. Utility is the satisfaction or enjoyment derived from consumption.

2. Economists do not think it is possible to compare the relative satisfaction derived from consumption across

individuals.

3. Marginal utility is the satisfaction received from all units of a good that are consumed.

4. When marginal utility begins to diminish, total utility always diminishes.

5. If a consumer is maximizing utility, she will purchase quantities of output to the point where the marginal utility

per dollar spent on consumption is equal across all goods.

6. As long as the marginal utility of the last unit consumed is positive, total utility will fall if a person consumes

less of a good.

7. As long as a person had to pay a positive price for a good, he would never consume to the point where his

marginal utility was falling with additional consumption.

8. A person could receive a higher marginal utility from the last diamond she purchases than from the last ounce of

water she purchases, yet receive less total utility from diamonds than from water.

9. If total utility from consuming five cups of cocoa is 13, 25, 35, 44, and 52 utils, respectively, the marginal utility

of the fourth cup of coffee is 9.

10. If Phil says, “You would have to pay me to eat another cookie now,” it would imply that his marginal utility from

consuming one more cookie now was negative.

Multiple Choice

1. The increase in total utility that one receives from eating an additional piece of sushi is called

a. marginal utility.

b. interpersonal utility.

c. marginal cost.

d. average utility.

e. average cost.

2. Marginal utility is

a. the total satisfaction derived from consuming all goods.

b. always the total satisfaction derived from consuming the first unit of a good.

c. always positive.

d. always negative.

e. the change in total satisfaction derived from consuming one more unit of a particular good.

3. As one eats more and more oranges

a. his total utility falls, but the marginal utility of each orange rises.

b. his marginal utility rises as long as the total utility derived from the oranges remains positive.

c. his total utility rises, as does the marginal utility of each orange.

d. his total utility rises as long as the marginal utility of the oranges is positive, but the marginal utility of each

additional orange likely falls.

4. The marginal utility from a hot fudge sundae

a. is always increasing.

b. is always greater than the average utility derived from all hot fudge sundaes consumed.

c. generally depends on how many hot fudge sundaes the consumer has already consumed.

d. is always equal to the price paid for the hot fudge sundae.

5. Total utility will decline when

a. marginal utility is falling.

b. marginal utility is rising.

C

H A P T E R

1 0

S T U D Y

G U I D E

257

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:04 PM Page 257

c. marginal utility equals zero.

d. marginal utility is constant.

e. marginal utility is negative.

6. When total utility is at its maximum

a. marginal utility is negative.

b. marginal utility is positive.

c. marginal utility is at its maximum.

d. marginal utility equals zero.

e. marginal utility stops decreasing and starts increasing.

7. The total utility from consuming five slices of pizza is 11, 18, 24, 29, and 32 utils, respectively. The marginal utility

of the third slice of pizza is

a. 11.

b. 7.

c. 18.

d. 6.

e. 53.

8. The total utility from consuming five sushi rolls is 12, 23, 33, 42, and 45 utils, respectively. Marginal utility begins

to diminish after consuming the ____________ sushi roll.

a. first

b. second

c. third

d. fourth

e. None of the above are correct; marginal utility does not diminish.

9. The law of diminishing marginal utility implies that the more of a commodity you consume, the

a. more you value additional units of output.

b. less you value additional units of output.

c. happier you are.

d. higher the price that is paid for the commodity.

10. When a consumer spends her income on goods and services in such a way that her utility is maximized, she reaches

a. monetary equilibrium.

b. market equilibrium.

c. consumer equilibrium.

d. marginal equilibrium.

11. Hamburgers cost $2 and hot dogs cost $1, and Juan is in consumer equilibrium. What must be true about the

marginal utility of the last hamburger Juan consumes?

a. The marginal utility of the last hamburger consumed must be less than that of the last hot dog.

b. The marginal utility of the last hamburger consumed must be equal to that of the last hot dog.

c. The marginal utility of the last hamburger consumed must be greater than that of the last hot dog.

d. The marginal utility of the last hamburger consumed must be equal to zero.

12. Melissa spent the week at an amusement park and used all of her money on rides and popcorn. Both rides and bags

of popcorn are priced at $1 each. Melissa realizes that the last bag of popcorn she consumed increased her utility by

40 utils, while the marginal utility of her last ride was only 20 utils. What should Melissa have done differently to

increase her satisfaction?

a. reduced the number of bags of popcorn she consumed and increased the number of rides

b. increased the number of bags of popcorn she consumed and reduced the number of rides

c. decreased both the number of bags of popcorn and rides consumed

d. increased both the number of bags of popcorn and rides consumed

e. nothing, as her utility was maximized

258

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:05 PM Page 258

13. The fact that a gallon of gasoline commands a higher market price than a gallon of water indicates that

a. gasoline is a scarce good but water is not.

b. the total utility of gasoline exceeds the total utility of water.

c. the marginal utility of a gallon of gasoline is greater than the marginal utility of a gallon of water.

d. the average utility of a gallon of gasoline is greater than the average utility of a gallon of water.

14. The total utility derived from consuming scoops of ice cream can be found by

a. multiplying the marginal utility of the last scoop consumed by the number of scoops consumed.

b. multiplying the marginal utility of the last scoop consumed by the price of a scoop of ice cream.

c. dividing the marginal utility of the last scoop consumed by its price.

d. summing the marginal utilities of each scoop consumed.

e. multiplying together the marginal utilities of each scoop of ice cream consumed.

15. In consumer equilibrium

a. the marginal utility from consumption is the same across all goods.

b. individuals consume so as to maximize their total satisfaction, given limited income.

c. the ratio of the marginal utility of each good divided by its price is equal across all goods consumed.

d. all of the above are true.

e. all of the above are generally true except a.

Problems

1. Suppose it is “All You Can Eat” Night at your favorite restaurant. Once you’ve paid $9.95 for your meal, how do

you determine how many helpings to consume? Should you continue eating until your food consumption has yielded

$9.95 worth of satisfaction? What happens to the marginal utility from successive helpings as consumption increases?

2. Suppose you currently spend your weekly income on movies and video games such that the marginal utility per dollar

spent on each activity is equal. If the price of a movie ticket rises, how will you reallocate your fixed income between

the two activities? Why?

3. Brandy spends her entire weekly budget of $20 on soda and pizza. A can of soda and a slice of pizza are priced at $1

and $2, respectively. Brandy’s marginal utility from soda and pizza consumption is 6 utils and 4 utils, respectively.

What advice could you give Brandy to help her increase her overall satisfaction from the consumption of soda and

pizza? What will happen to the marginal utility per dollar from soda consumption if Brandy follows your advice?

The marginal utility per dollar from pizza consumption?

4. Suppose you were studying late one night and you were craving a Papa John’s pizza. How much marginal utility

would you receive? How much marginal utility would you receive from a pizza that was delivered immediately after

you finished a five-course Thanksgiving dinner? Where would you be more likely to eat more pizza in a single setting,

at home or at a crowded party (particularly if you are not sure how many pizzas have been ordered)? Use marginal

utility analysis to answer the last question.

259

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:05 PM Page 259

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:05 PM Page 260

261

A P P E N D I X

A More Advanced Theory of Consumer Choice

261

In this appendix, we will develop a slightly more

advanced set of tools using indifference curves and

budget lines to aid in our understanding the theory of

consumer choice. These approaches allow us to express

our total utility as a function of two goods. The tools

developed here allow us to see how the optimal combi-

nation changes in response to changing prices and

income. Let’s begin with indifference curves.

INDIFFERENCE CURVES

On the basis of their tastes and preferences, con-

sumers must subjectively choose the bundle of goods

and services that yield the highest level of satisfaction

given their money income and prices.

What Is an Indifference Curve?

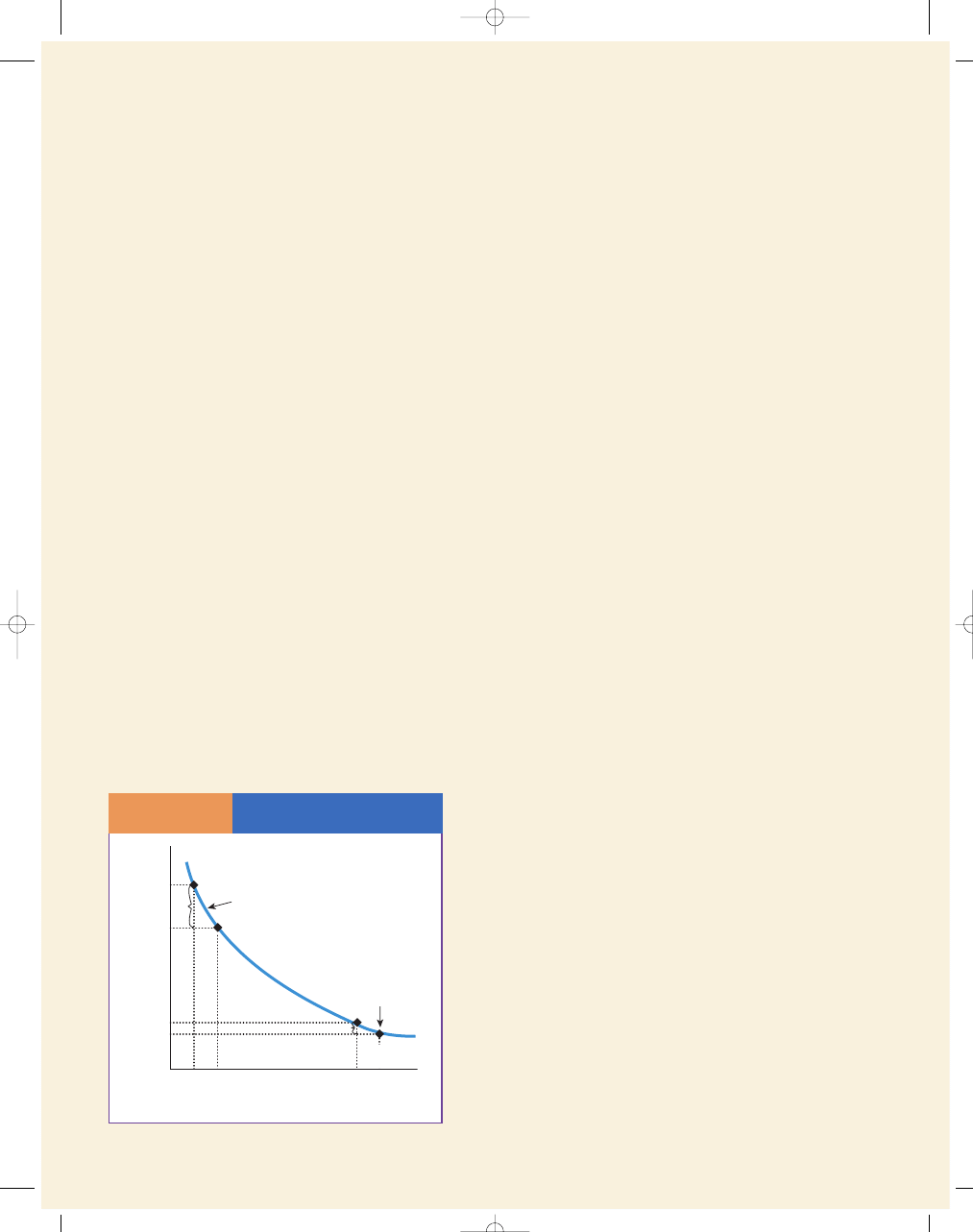

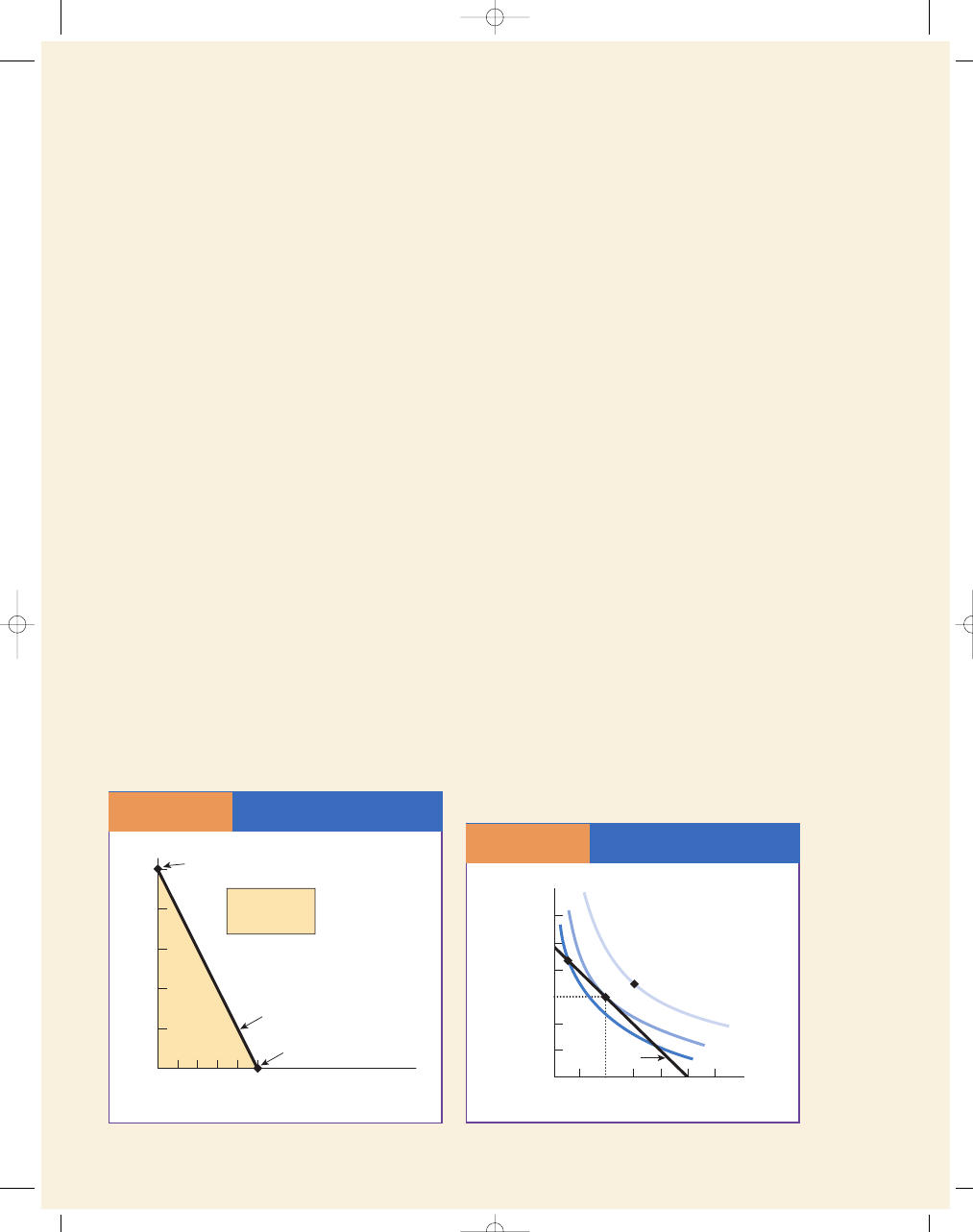

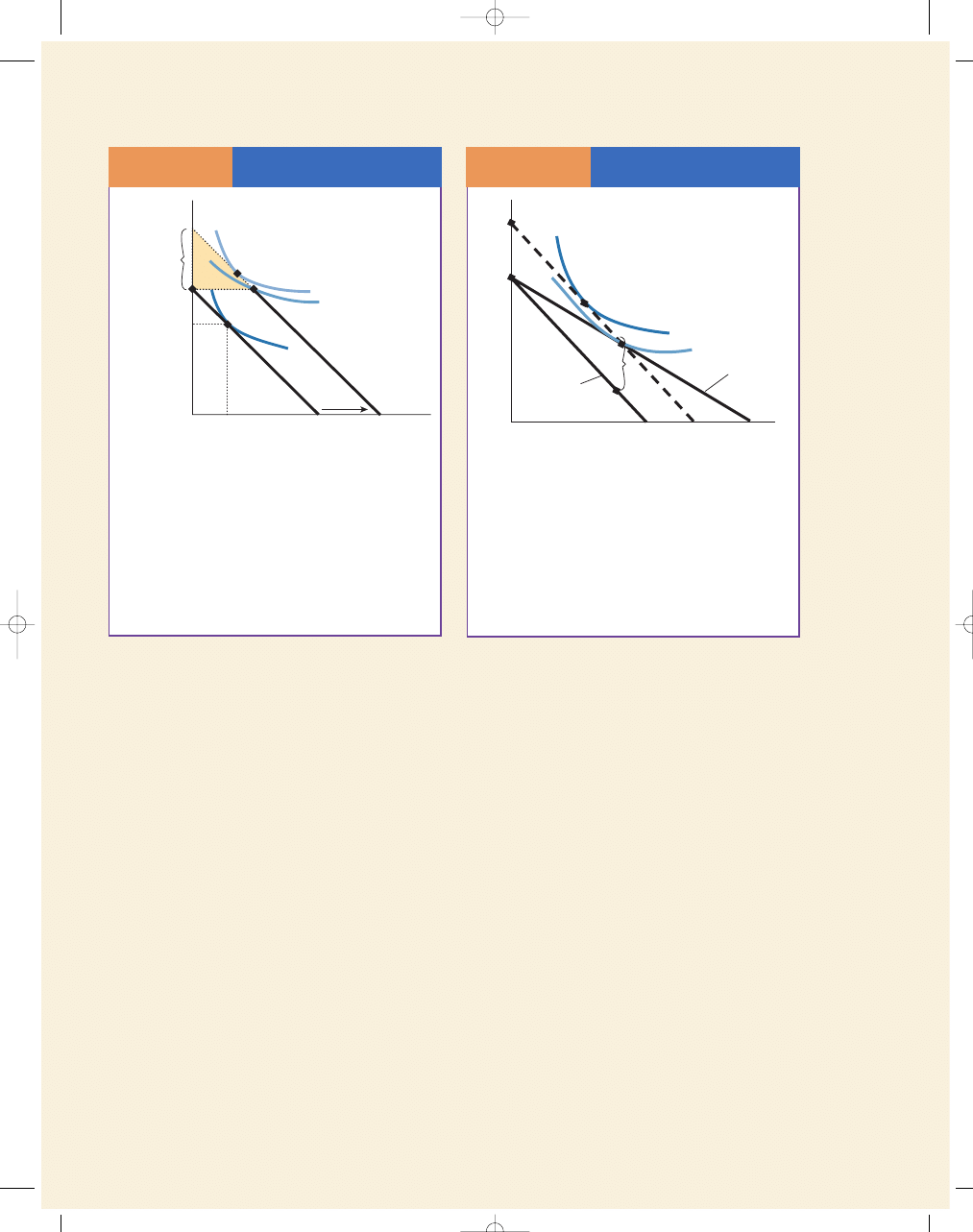

A consumer’s indifference curve, shown in Exhibit 1,

contains various combinations of two commodities,

and each combination of goods (like points A, B, and C)

on the indifference curve will yield the same level of

total utility to this consumer. The consumer is said to be

indifferent between any combination of the two goods

along an individual indifference curve because she

receives the same level of satisfaction from each bundle.

THE PROPERTIES OF THE INDIFFERENCE CURVE

Indifference curves have the following three properties:

(1) Higher indifference curves represent greater satis-

faction, (2) they are negatively sloped, and (3) they

are convex from the origin.

Higher Indifference Curves Represent

Greater Satisfaction

Although consumers are equally happy with any

bundle of goods along the indifference curve, they

prefer to be on the highest indifference curve possible.

This preference follows from the assumption that

more of a good is preferred to less of a good. For

example, in Exhibit 2, the consumer would prefer I

2

to I

1

. The higher indifference curve represents more

satisfaction. As you can see in Exhibit 2, bundle D

gives the consumer more of both goods than does

bundle C, which is on a lower indifference curve.

Bundle D is also preferred to bundle A because there

is more than enough extra food to compensate the

consumer for the loss of clothing; total utility has

risen because the consumer is now on a higher indif-

ference curve.

An Indifference Curve

A P P E N D I X

E

X H I B I T

1

B

Indifference

Curve

C

A

Quantity of Clothing

Quantity of Food

0

Indifference Curves

A P P E N D I X

E

X H I B I T

2

B

C

D

A

Quantity of Clothing

Quantity of Food

0

I

2

I

1

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:05 PM Page 261

262

M O D U L E 3

Households, Firms, and Market Structure

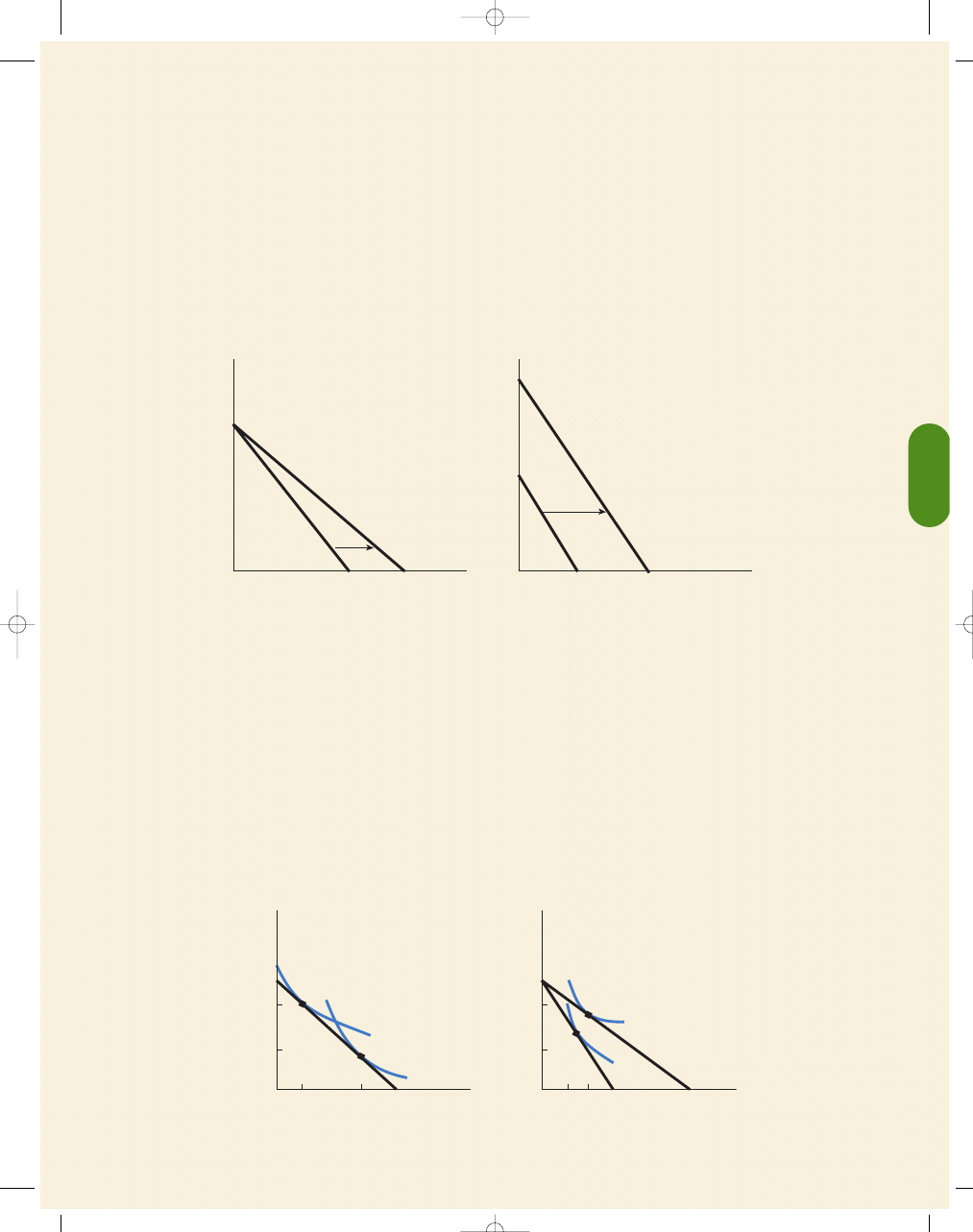

Indifference Curves Are Negatively Sloped

Indifference curves must slope downward from left to

right if the consumer views both goods as desirable. If

the quantity of one good is reduced, the quantity of

the other good must be increased to maintain the

same level of total satisfaction.

Indifference Curves Are Convex from the Origin

The slope of an indifference curve at a particular

point measures the marginal rate of substitution

(MRS), the rate at which the consumer is willing to

trade one good to gain one more unit of another

good. If the indifference curve is steep, the marginal

rate of substitution is high. The consumer would be

willing to give up a large amount of clothing for a

small amount of food because she would still main-

tain the same level of satisfaction; she would remain

on the same indifference curve, as at point A in

Exhibit 3. If the indifference curve is flatter, the mar-

ginal rate of substitution is low. The consumer is only

willing to give up a small amount of clothing in

exchange for an additional unit of food to remain

indifferent, as seen at point B in Exhibit 3. A con-

sumer’s willingness to substitute one good for another

depends on the relative quantities he consumes. If he

has lots of something, say food relative to clothing, he

will not value the prospect of getting even more food

very highly, which is just the law of demand, which is

based on the law of diminishing marginal utility.

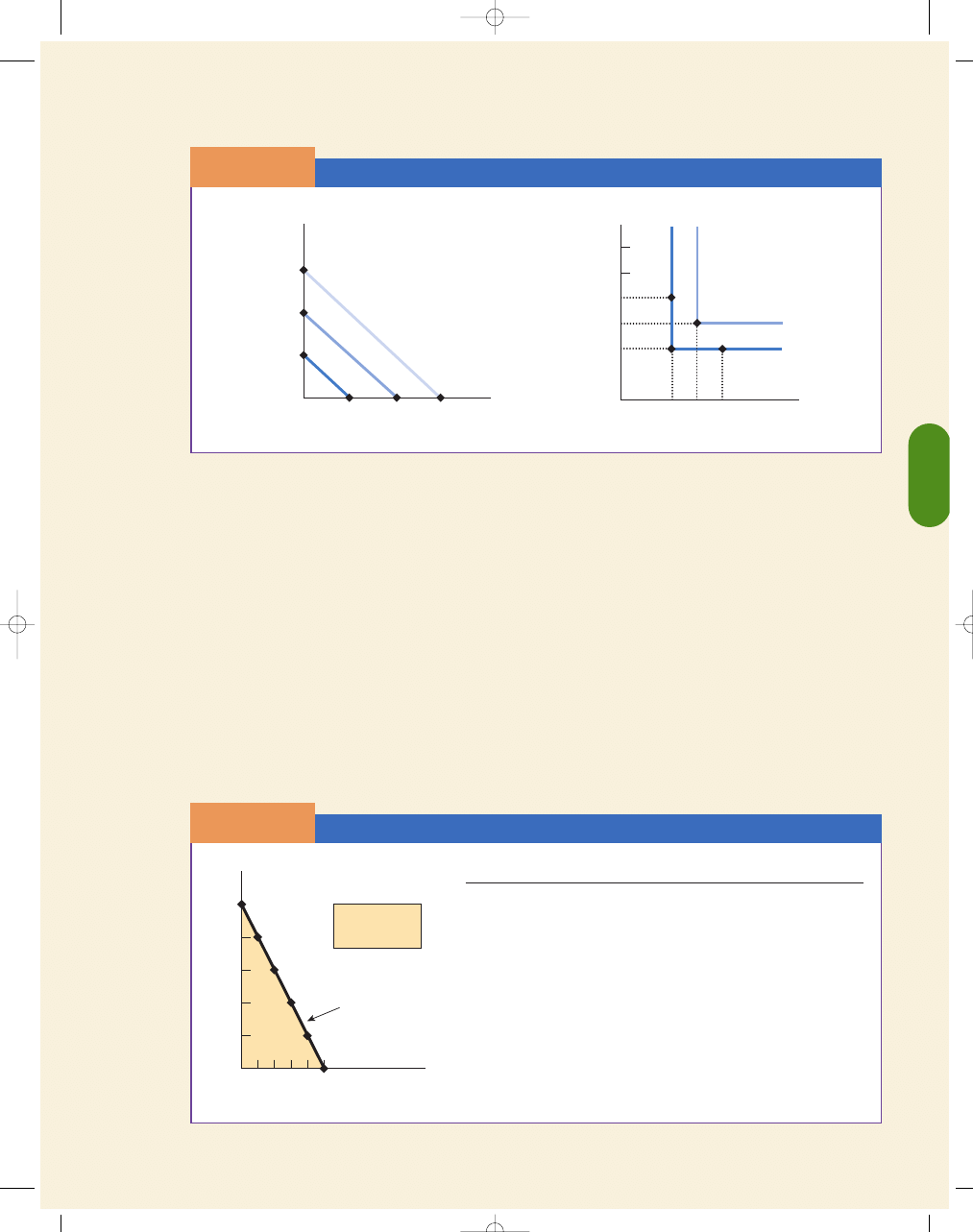

Complements and Substitutes

As we learned in Chapter 4, many goods are comple-

ments to each other; that is, the use of more units of

one encourages the acquisition of additional units of

the other. Gasoline and automobiles, baseballs and

baseball bats, snow skis and bindings, bread and

butter, and coffee and cream are examples of comple-

mentary goods. When goods are complements, units

of one good cannot be acquired without affecting the

want-satisfying power of other goods. Some goods

are substitutes for one another; that is, the more you

have of one, the less you desire the other. (The rela-

tionship between substitutes is thus the opposite of

the relation between complements.) Examples of sub-

stitutes include coffee and tea, sweaters and jackets,

and home-cooked and restaurant meals.

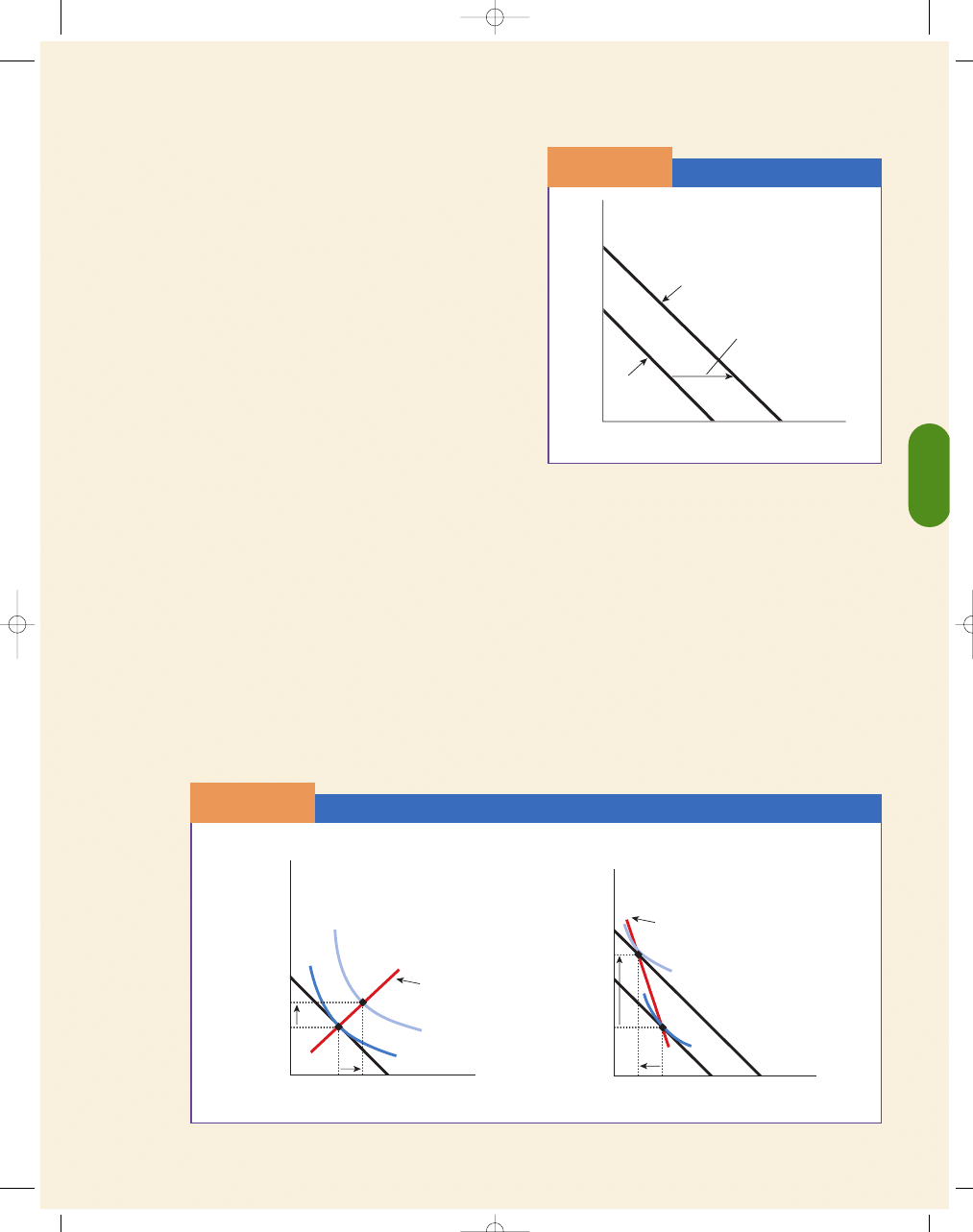

The degree of convexity of an indifference

curve—that is, the extent to which the curve deviates

from a straight line—depends on how easily the two

goods can be substituted for each other. If two com-

modities are perfect substitutes—one $10 bill and two

$5 bills, for example—the indifference curve is a

straight line (in this case, the line’s slope is

−1). As

depicted in Exhibit 4(a), the marginal rate of substi-

tution is the same regardless of the extent to which

one good is replaced by the other.

At the other extreme are two commodities that are

not substitutes but are perfect complements, such as

left and right shoes. For most people, these goods are

never used separately but are consumed only together.

Because it is impossible to replace units of one with

units of the other and maintain satisfaction, the mar-

ginal rate of substitution is undefined; thus, the indif-

ference curve is a right angle, as shown in Exhibit 4(b).

Because most people only care about pairs of shoes, 4

left shoes and 2 right shoes (bundle B) would yield the

same level of satisfaction as 2 left shoes and 2 right

shoes (bundle A). Two pairs of shoes (bundle A) are

also as good as 4 right shoes and 2 left shoes (bundle

C). That is, bundles A, B, and C all lie on the same

indifference curve and yield the same level of satisfac-

tion. But the combination of three right shoes and

three left shoes (bundle D) is preferred to any combi-

nation of bundles on indifference curve I

1

.

If two commodities can easily be substituted for

one another, the nearer the indifference curves will

approach a straight line; in other words, it will maintain

more closely the same slope along its length throughout.

The greater the complementarity between the two

goods, the nearer the indifference curves will approach

a right angle.

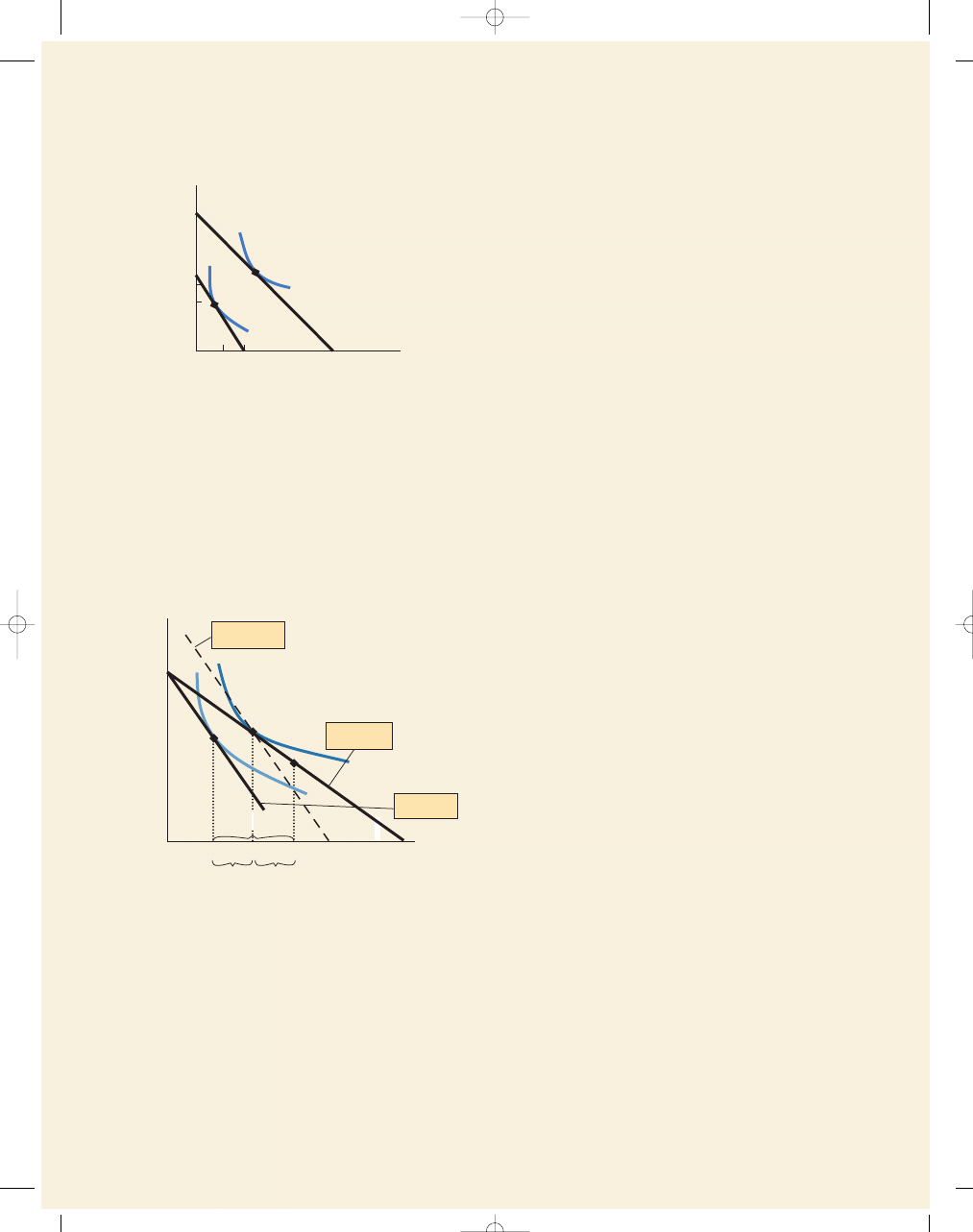

THE BUDGET LINE

A consumer’s purchase opportunities can be illustrated

by a budget line. More precisely, a budget line repre-

sents the various combinations of two goods that a

Indifference Curves Are

Convex from the Origin

A P P E N D I X

E

X H I B I T

3

4

Quantity of Clothing

Quantity of Food

0

20

15

5

A

B

10

5

1

MRS

= 5

MRS

= 1

1

1

4

2

6

8

10

1

3

5

7

9

Indifference

Curve

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:05 PM Page 262

C H A P T E R 1 0

Consumer Choice Theory

263

consumer can buy with a given income, holding the

prices of the two goods constant. For simplicity, we

only examine the consumer’s choices between two

goods. We recognize that this example is not com-

pletely realistic, as a quick visit to the store shows con-

sumers buying a variety of different goods and services.

However, the two-good model allows us to focus on

the essentials, with a minimum of complication.

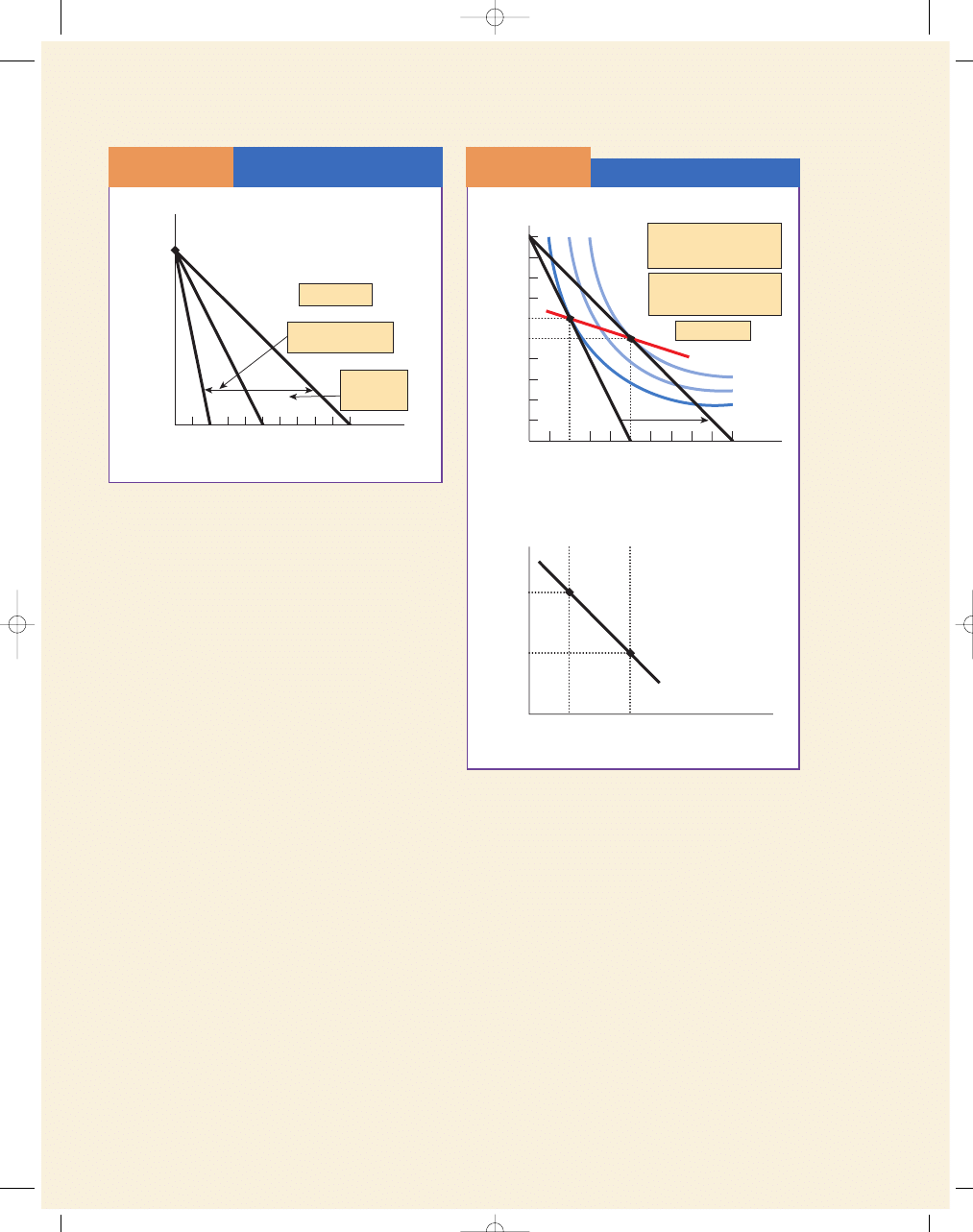

First, let’s look at a consumer who has $50 of

income a week to spend on two goods—food and

clothing. The price of food is $10 per unit, and the

price of clothing is $5 per unit. If the consumer

spends all her income on food, she can buy 5 units

of food per week ($50/$10

= 5). If she spends all her

income on clothing, she can buy 10 units of clothing

per week ($50/$5

= 10). However, it is likely that she

will spend some of her income on each. Six of the

affordable combinations are presented in the table in

Exhibit 5. In the graph in Exhibit 5, the horizontal

axis measures the quantity of food and the vertical

axis measures the quantity of clothing. Moving

along the budget line we can see the various combi-

nations of food and clothing the consumer can pur-

chase with her income. For example, at point A, she

could buy 10 units of clothing and 0 units of food;

at point B, 8 units of clothing and 1 unit of food;

and so on.

Of course, any other combination along the budget

line is also affordable. However, any combination of

goods beyond the budget line is not feasible.

Perfect Substitutes and Perfect Complements

A P P E N D I X

E

X H I B I T

4

4

2

6

I

3

I

2

I

1

$10 Bills

$5 Bills

0

3

2

1

I

2

I

1

2

1

B

A

D

3

Left Shoes

Right Shoes

0

3

4

5

6

2

1

4

5

6

C

a. Perfect Substitutes

b. Perfect Complements

The Budget Line

A P P E N D I X

E

X H I B I T

5

10

8

6

4

2

1 2 3 4

X

Y

A

B

C

D

E

F

Budget

Line

Not

Affordable

Affordable

Quantity of Clothing

0

5

Quantity of Food

Income

$50

P

X

(Food)

$10

P

Y

(Clothing)

$5

Consumption

Clothing

Food

Total

Opportunities

Clothing

Food

Expenditures

Expenditures

Expenditures

A

10

0

$50

$ 0

$50

B

8

1

40

10

50

C

6

2

30

20

50

D

4

3

20

30

50

E

2

4

10

40

50

F

0

5

0

50

50

95469_10_Ch10-p241-270.qxd 29/12/06 12:05 PM Page 263

264

M O D U L E 3

Households, Firms, and Market Structure

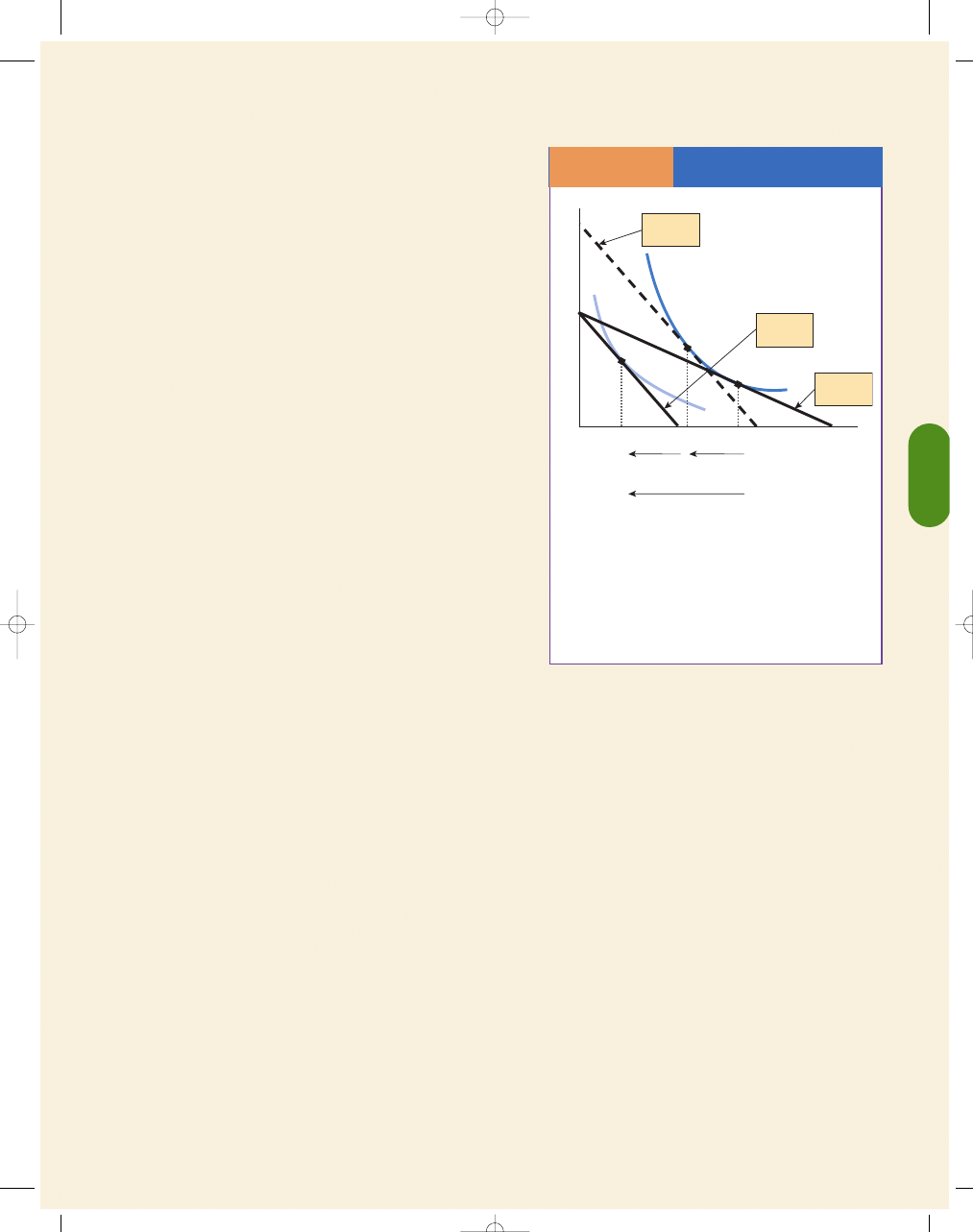

Finding the X- and Y-Intercepts of the Budget Line

The intercept on the vertical Y-axis (the clothing axis)

and the intercept on the horizontal X-axis (the food

axis) can easily be found by dividing the total income

available for expenditures by the price of the good in

question. For example, if the consumer has a fixed

income of $50 a week and clothing costs $5 per unit,

we know that if he spends all his income on clothing,

he can afford 10 (Income/P

Y

= $50/$5 = 10); so 10 is

the intercept on the Y-axis. Now if he spends all his

$50 on food and food costs $10 per unit, he can

afford to buy 5 (Income/P

X

= $50/$10 = 5); so 5 is the

intercept on the X-axis, as shown in Exhibit 6.

Finding the Slope of the Budget Line

The slope of the budget line is equal to

−P

X

/P

Y

. The neg-

ative coefficient of the slope indicates that the budget

line is negatively sloped (downward sloping), reflecting

the fact that you must give up some of one good to get

more of the other. For example, if the price of X (food)

is $10 and the price of Y (clothing) is $5, then the slope

is equal to

−10/5, or −2. That is, 2 units of Y can be

obtained by forgoing the purchase of 1 unit of X; hence,

the slope of the budget line is said to be

−2 (or 2, in

absolute value terms) as seen in Exhibit 6.

CONSUMER OPTIMIZATION

So far, we have seen a budget line, which shows the

combinations of two goods that a consumer can afford,

and indifference curves, which represent the con-