32

C H A P T E R

hen people travel to foreign countries,

they pay for their goods and services in

foreign currencies. For example, if we were

in Italy and were buying Italian shoes, we

would have to pay in euros—and we might

want to know how much that will cost us in U.S.

currency. In this chapter, we will learn how nations

pay each other in world trade and how we meas-

ure how much buying and selling is going on. We

will also learn about exchange rates.

■

32.1

The Balance of Payments

32.2

Exchange Rates

32.3

Equilibrium Changes in the

Foreign Exchange Market

32.4

Flexible Exchange Rates

I

N T E R N A T I O N A L

F

I N A N C E

I

N T E R N A T I O N A L

F

I N A N C E

W

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:50 AM Page 931

932

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

BALANCE OF PAYMENTS

The record of all of the international financial trans-

actions of a nation over a year is called the balance of

payments. The

balance

of payments

is a state-

ment that records all the

exchanges requiring an

outflow of funds to for-

eign nations or an inflow

of funds from other

nations. Just as an exam-

ination of gross domestic

product accounts gives us some idea of the economic

health and vitality of a nation, the balance of pay-

ments provides information about a nation’s world

trade position. The balance of payments is divided

into three main sections: the current account, the cap-

ital account, and an “error term” called the statistical

discrepancy. These are highlighted in Exhibit 1. Let’s

look at each of these components, beginning with the

current account, which is made up of imports and

exports of goods and services.

THE CURRENT ACCOUNT

Export Goods and the Current Account

A

current account

is a record of a country’s imports

and exports of goods and services, net investment

income, and net trans-

fers. Any time a foreign

buyer purchases a good

from a U.S. producer,

the foreign buyer must

pay the U.S. producer

for the good. Usually,

the foreign buyer must

pay for the good in U.S.

dollars, because the producer wants to pay his workers’

wages and other input costs with dollars. Making this

payment requires the foreign buyer to exchange units of

her currency at a foreign exchange dealer for U.S. dol-

lars. Because the United States gains claims for foreign

goods by obtaining foreign currency in exchange for the

dollars needed to buy exports, all exports of U.S. goods

abroad are considered a credit, or plus (

), item in the

U.S. balance of payments. Those foreign currencies are

S E C T I O N

32.1

T h e B a l a n c e o f P a y m e n t s

■

What is the balance of payments?

■

What are the three main components of

the balance of payments?

■

What is the balance of trade?

current account

a record of a country’s imports

and exports of goods and services,

net investment income, and net

transfers

balance of payments

the record of international transac-

tions in which a nation has engaged

over a year

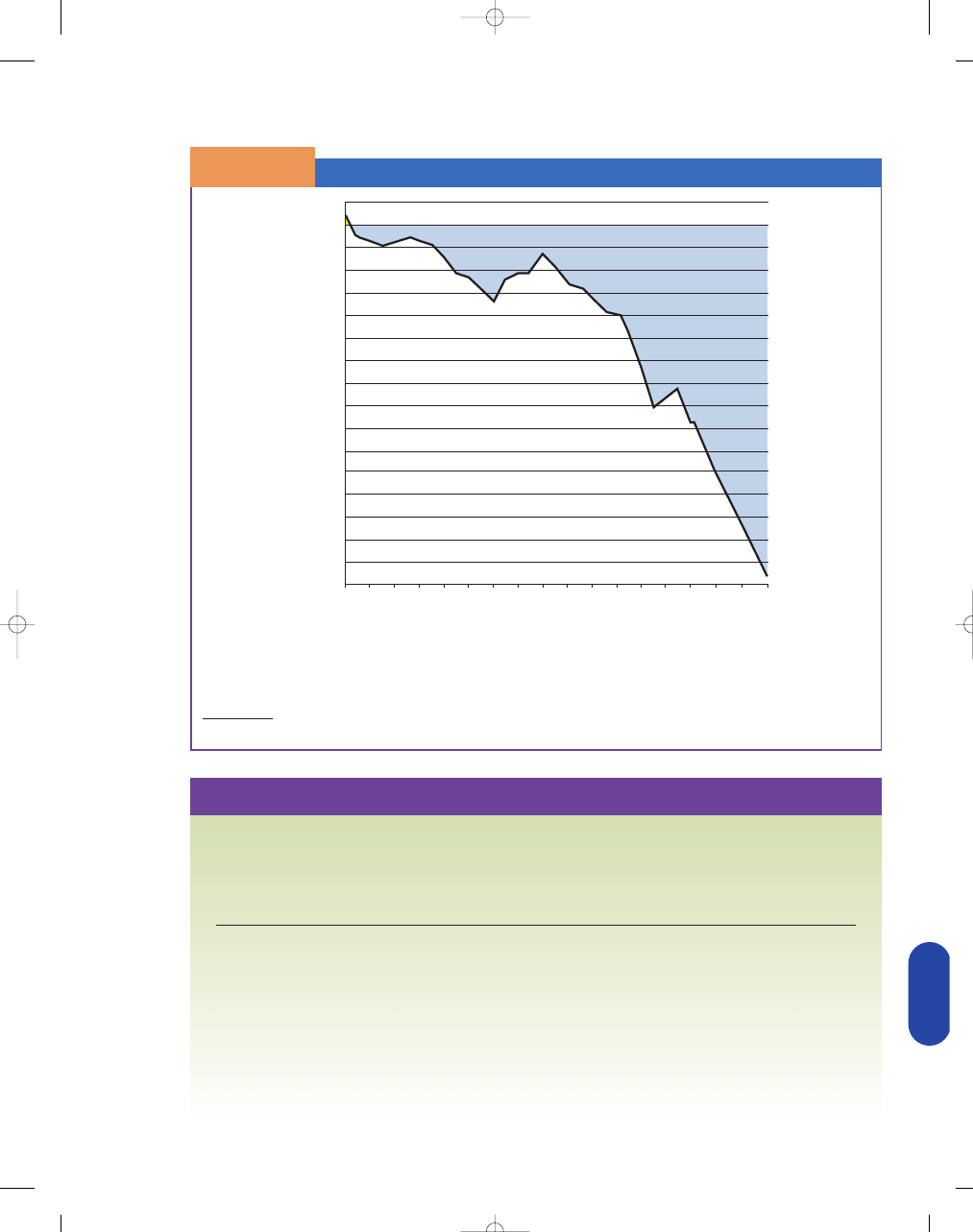

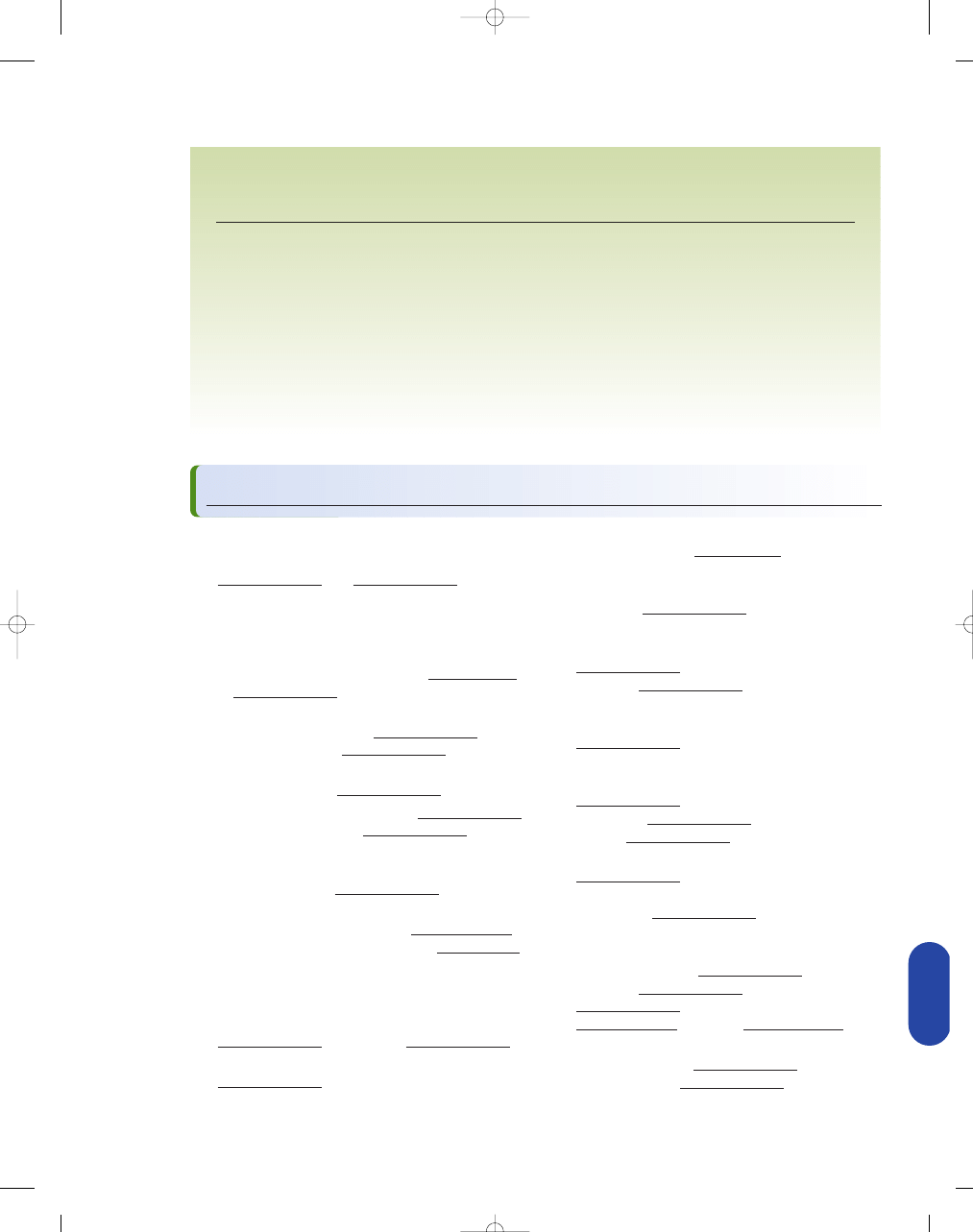

U.S. Balance of Payments, 2005 (billions of dollars)

S E C T I O N

32 .1

E

X H I B I T

1

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 1.

Current Account

1.

Exports of goods

$ 895

2.

Imports of goods

1,677

3.

Balance of trade (lines 1

2)

782

4.

Service exports

381

5.

Service imports

315

6.

Balance on goods and services

716

(lines 3

4 5)

7.

Unilateral transfers (net)

86

8.

Investment income (net)

11

9.

Current account balance

791

(lines 6

7 8)

Capital Account

10.

U.S.-owned assets abroad

$

427

11.

Foreign-owned assets in the

1,212

United States

12.

Capital account balance

785

(lines 10

11)

13.

Statistical discrepancy

6

14.

Net Balance

$0

(lines 9

12 13)

Type of Transaction

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:50 AM Page 932

C H A P T E R 3 2

International Finance

933

later exchangeable for goods and services made in the

country that purchased the U.S. exports.

Import Goods and the Current Account

When a U.S. consumer buys an imported good, how-

ever, the reverse is true: The U.S. importer must pay

the foreign producer, usually in that nation’s currency.

Typically, the U.S. buyer will go to a foreign exchange

dealer and exchange dollars for units of that foreign

currency. Imports are thus a debit (–) item in the bal-

ance of payments, because the dollars sold to buy the

foreign currency add to foreign claims for foreign

goods, which are later exchangeable for U.S. goods

and services. U.S. imports, then, provide the means by

which foreigners can buy U.S. exports.

Services and the Current Account

Even though imports and exports of goods are the

largest components of the balance of payments, they

are not the only ones. Nations import and export serv-

ices as well. A particularly important service is tourism.

When U.S. tourists go abroad, they are buying foreign-

produced services in addition to those purchased by cit-

izens there. Those services include the use of hotels,

sightseeing tours, restaurants, and so forth. In the cur-

rent account, these services are included in imports. On

the other hand, foreign tourism in the United States

provides us with foreign currencies and claims against

foreigners, so they are included in exports. Airline and

shipping services also affect the balance of payments.

When someone from Italy flies American Airlines, that

person is making a payment to a U.S. company.

Because the flow of international financial claims is the

same, this payment is treated just like a U.S. export in

the balance of payments. If an American flies on

Alitalia, however, Italians acquire claims against the

United States; and so it is included as a debit (import)

item in the U.S. balance-of-payments accounts.

Net Transfer Payments and Net Investment Income

Other items that affect the current account are private

and government grants and gifts to and from other

countries. When the U.S. gives foreign aid to another

country, a debit occurs in the U.S. balance of payments

because the aid gives foreigners added claims against the

United States in the form of dollars. Private gifts, such

as individuals sending money to relatives or friends in

foreign countries, show up in the current account as

debit items as well. Because the United States usually

sends more humanitarian and military aid to foreigners

than it receives, net transfers are usually in deficit.

Net investment income is also included in the

current account (line 8)—U.S. investors hold foreign

assets and foreign investors hold U.S. assets. A pay-

ment received by U.S. residents are added to the cur-

rent account and payments made by U.S. residents are

subtracted from the current account. In 2005, a net

flow of $2 billion came into the United States.

The Current Account Balance

The balance on the current account is the net amount

of credits or debits after adding up all transactions of

goods (merchandise imports and exports), services,

and transfer payments (e.g., foreign aid and gifts). If

the sum of credits exceeds the sum of debits, the

nation is said to run a balance-of-payments surplus

on the current account. If debits exceed credits, how-

ever, the nation is running a balance-of-payments

deficit on the current account.

According to hotel and motel records, San Francisco has roughly

4 million visitors annually. This number does not take into

account people who stayed with friends or family or people

who visited the city for the day only. When a foreign tourist

rides a cable car in San Francisco, how does that affect the cur-

rent account? Tourism provides the United States with foreign

currency, which is included in exports.

©

J

an Butchofsky-Houser/CORBIS

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:50 AM Page 933

934

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

The Balance of Trade and the Balance

of the Current Account

The balance of payments of the United States for

2005 is presented in Exhibit 1. Notice that exports

and imports of goods

and services are by far

the largest credits and

debits. Notice also that

U.S. exports of goods

were $782 billion less

than imports of goods.

The import/export goods

relationship is often called the

balance of trade.

The

United States, therefore, experienced a balance-of-trade

deficit that year of $782 billion. However, some of

the $782 billion trade deficit is offset by credits from a

$66 billion surplus in services. This difference leads to

a $716 billion deficit in the balance of goods and serv-

ices. When $86 billion of net unilateral transfers (gifts

and grants between the United States and foreigners)

and $11 billion of investment income (net) from the

United States are added (the foreigners gave more to

the United States than the United States gave to the

foreigners), the total deficit on the current account is

$791 billion. Exhibit 2 shows the balance on the current

account since 1975.

THE CAPITAL ACCOUNT

How was this deficit on the current account financed?

Remember that U.S. credits give us the financial means

to buy foreign goods

and that our credits were

$785 billion less than

our debits from imports

and net unilateral trans-

fers to foreign countries.

This deficit on the cur-

rent account balance is

settled by movements of

financial, or capital, assets. These transactions are

recorded in the capital account, so that a current

account deficit is financed by a capital account surplus.

In short, the

capital account

records the foreign pur-

chases or assets in the United States (a monetary

inflow) and U.S. purchases of assets abroad (a mone-

tary outflow).

What Does the Capital Account Record?

Capital account transactions include such items as inter-

national bank loans, purchases of corporate securities,

government bond purchases, and direct investments

in foreign subsidiary companies. In 2005, the United

States purchased foreign assets of $427 billion, which

was a further debit because it provided foreigners

with U.S. dollars. On the other hand, foreign invest-

ments in U.S. bonds, stocks, and other items totaled

more than $1,212 billion. In addition, the United

States and other governments buy and sell dollars. On

net in 2005, foreign-owned assets in the United States

made about $785 billion more than did U.S. assets

abroad. On balance, then, a surplus (positive credit)

in the capital account from capital movements

amounted to $785 billion, offsetting the $791 billion

deficit on current account.

The Statistical Discrepancy

In the final analysis, it is true that the balance-of-

payments account (current account minus capital

account) must balance so that credits and debits are

equal. Why? Due to the reciprocal aspect of trade, every

credit eventually creates a debit of equal magnitude.

These errors are sometimes large and are entered into

the balance of payments as the statistical discrepancy.

Including the errors and omissions recorded as the

statistical discrepancy, the balance of payments does

balance. That is, the number of U.S. dollars demanded

equals the number of U.S. dollars supplied when the

balance of payments is zero.

Balance of Payments: A Useful Analogy

In concept, the international balance of payments is sim-

ilar to the personal financial transactions of an individ-

ual. Each individual has a personal “balance of

payments,” reflecting that person’s trading with other

economic units: other individuals, corporations, and

governments. People earn income or credits by “export-

ing” their labor service to other economic units or by

receiving investment income (a return on capital serv-

ices). Against that, they “import” goods from other eco-

nomic units; we call these imports consumption. This

debit item is sometimes augmented by payments made to

outsiders (e.g., banks) on loans and so forth. Fund trans-

fers, such as gifts to children or charities, are other debit

items (or credit items for recipients of the assistance).

As individuals, if our spending on consumption

exceeds our income from exporting our labor and cap-

ital services, we have a “deficit” that must be financed

by borrowing or selling assets. If we “export” more

than we “import,” however, we can make new invest-

ments and/or increase our “reserves” (savings and

investment holdings). Like nations, an individual who

runs a deficit in daily transactions must make up for it

through accommodating transactions (e.g., borrowing

or reducing personal savings or investment holdings)

to bring about an ultimate balance of credits and

debits in his or her personal account.

balance of trade

the net surplus or deficit resulting

from the level of exportation and

importation of merchandise

capital account

records the foreign purchases or assets

in the domestic economy (a mone-

tary inflow) and domestic purchases

of assets abroad (a monetary outflow)

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:50 AM Page 934

C H A P T E R 3 2

International Finance

935

S E C T I O N

*

C H E C K

1.

The balance of payments is the record of all the international financial transactions of a nation for any given year.

2.

The balance of payments is made up of the current account and the capital account, as well as an “error term”

called the statistical discrepancy.

3.

The balance of trade refers strictly to the import and export of goods (merchandise) from/to other nations. If our

imports of foreign goods are greater than our exports, we are said to have a balance-of-trade deficit.

1.

What is the balance of payments?

2.

Why must British purchasers of U.S. goods and services first exchange pounds for dollars?

3.

How is it that our imports provide foreigners with the means to buy U.S. exports?

4.

What would have to be true for the United States to have a balance-of-trade deficit and a balance-of-payments surplus?

5.

What would have to be true for the United States to have a balance-of-trade surplus and a current account deficit?

6.

With no errors or omissions in the recorded balance-of-payments accounts, what should the statistical

discrepancy equal?

7.

A Nigerian family visiting Chicago enjoys a Chicago Cubs baseball game at Wrigley Field. How would this expense

be recorded in the balance-of-payments accounts? Why?

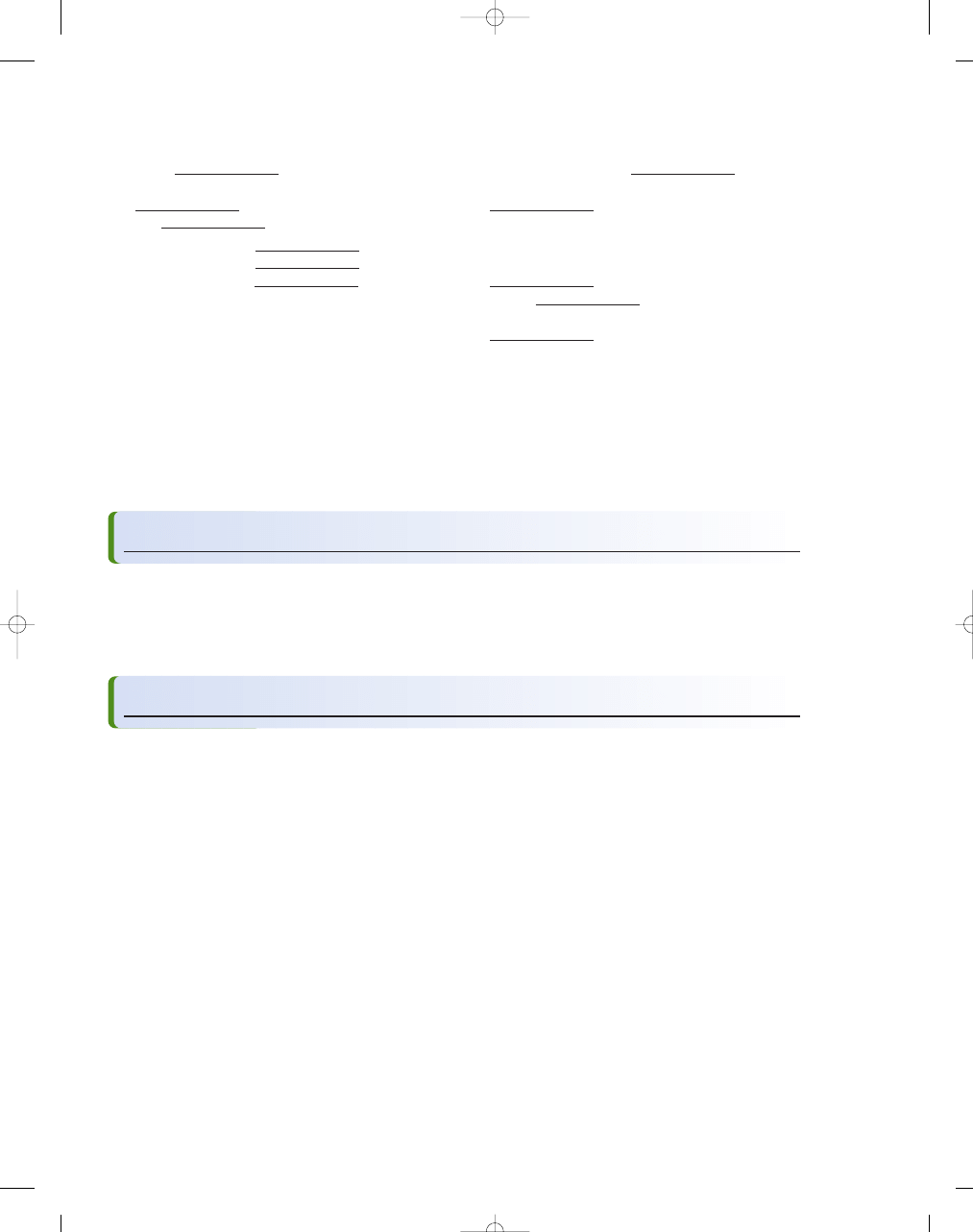

U.S. Balance of Trade on Goods, 1975–2005

S E C T I O N

32 .1

E

X H I B I T

2

50

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

500

550

600

650

700

750

800

1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Year

Surplus

Balance of

T

rade

(billions of dollar

s)

Deficit

In November of 2004, the former Federal Reserve chairman, Alan Greenspan warned policymakers that the large

and consistent trade deficits could sour foreign appetites to invest in the United States. Greenspan speculated that

foreigners may unload their investments or demand higher interest rates. Either scenario could cause problems for

the U.S. economy that is heavily dependent on foreign capital. (Japan, China, and Britain are the biggest foreign

holders of U.S. Treasury securities.)

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2006.

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:50 AM Page 935

936

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

THE NEED FOR FOREIGN CURRENCIES

When a U.S. consumer buys goods from a seller in

another country—who naturally wants to be paid in

her own domestic currency—the U.S. consumer must

first exchange U.S. dollars for the seller’s currency in

order to pay for those goods. American importers

must, therefore, constantly buy yen, euros, pesos, and

other currencies in order to finance their purchases.

Similarly, someone in another country buying U.S.

goods must sell his domestic currency to obtain U.S.

dollars to pay for those goods.

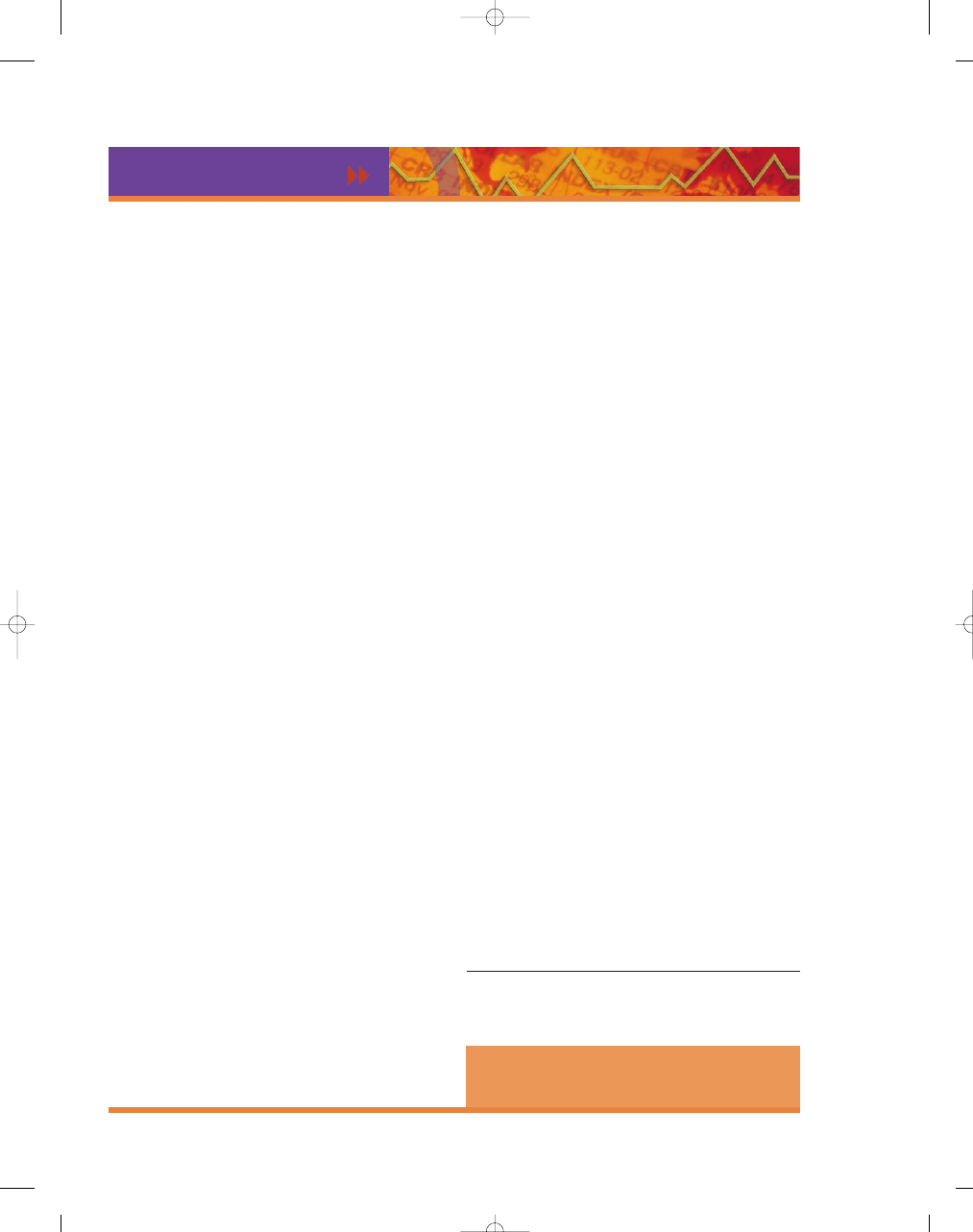

THE EXCHANGE RATE

The price of a unit of one foreign currency in terms

of another is called the

exchange rate.

If a U.S.

importer has agreed to

pay euros (the cur-

rency of the European

Union) to buy a

cuckoo clock made in

the Black Forest in

Germany, she would

then have to exchange

U.S. dollars for euros. If it takes $1 to buy 1 euro,

then the exchange rate is $1 per euro. From the

German perspective, the exchange rate is 1 euro per

U.S. dollar.

CHANGES IN EXCHANGE RATES AFFECT THE

DOMESTIC DEMAND FOR FOREIGN GOODS

Prices of goods in their currencies combine with

exchange rates to determine the domestic price of for-

eign goods. Suppose the cuckoo clock sells for 100

euros in Germany. What is the price to U.S. con-

sumers? Let’s assume that tariffs and other transac-

tion costs are zero. If the exchange rate is $1

1

euro, then the equivalent U.S. dollar price of the

cuckoo clock is 100 euros times $1 per euro, or $100.

If the exchange rate were to change to $2

1 euro,

fewer clocks would be demanded in the United States,

because the effective U.S. dollar price of the clocks

would rise to $200 (100 euros

$2 per euro). The

higher relative value of a euro compared to the dollar

(or, equivalently, the lower relative value of a dollar

compared to the euro) would lead to a reduction in

U.S. demand for German-made clocks.

THE DEMAND FOR A FOREIGN CURRENCY

The demand for foreign

currencies is known as

a

derived demand,

be-

cause the demand for a

foreign currency derives

directly from the demand

for foreign goods and

S E C T I O N

32.2

E x c h a n g e R a t e s

■

What are exchange rates?

■

How are exchange rates determined?

■

How do exchange rates affect the demand

for foreign goods?

derived demand

the demand for an input derived

from consumers’ demand for the

good or service produced with that

input

exchange rate

the price of one unit of a country’s

currency in terms of another coun-

try’s currency

using what you’ve learned

Exchange Rates

Why is a strong dollar (i.e., exchange rate for foreign currencies is

low) a mixed blessing?

strong dollar will lower the price of imports and make trips to

foreign countries less expensive. Lower prices on foreign goods

also help keep inflation in check and make investments in foreign financial

markets (foreign stocks and bonds) relatively cheaper. However, it makes

U.S. exports more expensive. Consequently, foreigners will buy fewer U.S.

goods and services. The net effect is a fall in exports and a rise in imports—

net exports fall. Note that some Americans are helped (vacationers going

to foreign countries and those preferring foreign goods), while others are

harmed (producers of U.S. exports, operators of hotels dependent on for-

eign visitors in the United States). A stronger dollar also makes it more

difficult for foreign investors to invest in the United States.

Q

A

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:50 AM Page 936

C H A P T E R 3 2

International Finance

937

services or for foreign investment. The more that goods

from a foreign country are demanded, the more of that

country’s currency is needed to pay for those goods.

This increased demand for the currency will push up

the exchange value of that currency relative to other

currencies.

THE SUPPLY OF A FOREIGN CURRENCY

Similarly, the supply of foreign currency is provided

by foreigners who want to buy the exports of a par-

ticular nation. For example, the more that foreigners

demand U.S. products, the more of their currencies

they will supply in exchange for U.S. dollars, which

they use to buy our products.

DETERMINING EXCHANGE RATES

We know that the demand for foreign currencies is

derived from the demand for foreign goods, but

how does that affect the exchange rate? Just as in

the product market, the answer lies with the forces

of supply and demand. In this case, it is the supply

of and demand for a foreign currency that deter-

mine the equilibrium price (exchange rate) of that

currency.

THE DEMAND CURVE FOR A FOREIGN CURRENCY

As Exhibit 1 shows, the demand curve for a foreign

currency—the euro, for example—is downward sloping,

just as it is in product markets. In this case, however,

the demand curve has a negative slope because as the

price of the euro falls relative to the dollar, European

products become relatively more inexpensive to U.S.

consumers, who therefore buy more European

goods. To do so, the quantity of euros demanded by

U.S. consumers will increase to buy more European

goods as the price of the euro falls. For this reason,

the demand for foreign currencies is considered to be

a derived demand.

THE SUPPLY CURVE FOR FOREIGN CURRENCY

The supply curve for a foreign currency is upward

sloping, just as it is in product markets. In this case,

as the price, or value, of the euro increases relative

to the dollar, U.S. products will become relatively

less expensive to European buyers, who will thus

increase the quantity of dollars they demand.

Europeans will, therefore, increase the quantity of

euros supplied to the United States by buying more

U.S. products.

Hence, the supply curve is upward sloping.

EQUILIBRIUM IN THE FOREIGN

EXCHANGE MARKET

Equilibrium is reached where the demand and supply

curves for a given currency intersect. In Exhibit 1, the

equilibrium price of a euro is $1.20. As in the prod-

uct market, if the dollar price of euros is higher than

the equilibrium price, an excess quantity of euros will

Equilibrium in the Foreign

Exchange Market

S E C T I O N

32 . 2

E

X H I B I T

1

Dollar Price of Eur

os

Quantity of Euros

0

$1.40

$1.20

$1.00

Excess supply

of euros

Excess demand

for euros

Demand for euros

(U.S. purchases of

European goods

and services)

Supply of euros

(U.S. sales

of goods

and services

to Europeans)

Suppose the foreign exchange market is in equilibrium

at 1 euro

$1.20. At any price higher than $1.20, a

surplus of euros will result. At any price lower than

$1.20, a shortage of euros will result.

On January 1, 1999,

the euro became

the currency in 11

countries: Belgium,

Germany, Spain,

France, Ireland,

Italy, Luxembourg,

the Netherlands,

Austria, Portugal,

and Finland. If the

euro becomes relatively less expensive in terms of dollars

(it now costs less to buy a euro), what will happen to the U.S.

demand for European goods? If the price of the euro falls rela-

tive to the dollar, European products become relatively less

expensive to U.S. consumers, who will tend to buy more

European goods.

©

AP/Wide W

or

ld

Photo

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:50 AM Page 937

938

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

i n t h e n e w s

Euro Beginning to Flex Its Economic Muscles

Its leaders are divided and its economies are distressed, but Europe stands tall

in one respect. The euro, its toddler currency, is growing into a cheeky rival to

the dollar, one of the most visible symbols of America’s power in the world.

After a hapless debut in January 1999, marked by a long, stomach-

churning slide in its value, the euro has made up virtually all the ground it lost

against the dollar. It now trades at an exchange rate of about $1.15 per euro,

only three cents shy of its value on the first day of trading.

More important, the euro has gained stature as a safe haven for investors

and governments.

The dollar remains the world’s default currency—the lingua franca of oil

traders and bond dealers, and the bedrock of foreign reserves held by central

banks from Brussels to Baghdad. But the euro is gaining ground, both as an

attractive currency in which to issue bonds and as an alternative to the dollar

for national foreign exchange reserves, notably in southeast Asian countries

with predominantly Muslim populations.

With the United States piling up vast deficits, economists say the euro

has a chance to consolidate its gains. “U.S. federal finances are coming under

increased strain,” said Niall C. Ferguson, a senior research fellow at Oxford.

“Money that had been invested in dollar-denominated assets is shifting to

euro assets. For the euro to become a little brother to the dollar seems per-

fectly plausible.”

Such a role would vindicate the guardians of the euro, who watch over it

from the European Central Bank’s glass-and-steel tower in Frankfurt. They

have always had grand ambitions for the currency, viewing it as an alternative

to the dollar and an instrument to drive Europe’s integration.

Yet an almighty euro carries risks for champions of a united Europe. It

could supply fresh ammunition to opponents of the monetary union in

Britain, Sweden and prospective members.

It could also open fissures between existing members that depend on

exports and stand to suffer from a currency that rises too far, too fast. Last

week, three euro countries—Germany, Italy and the Netherlands—reported

that they were on the brink of recession.

“If it goes much beyond $1.25, we’ve got a problem,” said Daniel Gros, direc-

tor of the Center for European Policy Studies, a research group in Brussels.

The introduction of euro notes and coins here last year was striking for

how smooth the process seemed. After a noisy buildup, the German mark, the

French franc and the Italian lira faded into history like quaint relics. In the

financial markets, where the euro had traded as a virtual currency since 1999,

the transition was equally seamless, with investors showing prompt accept-

ance of the new currency. . . .

[Barry] Eichengreen [professor of economics at the University of

California, Berkeley] said there was no reason the euro’s influence would not

eventually match the dollar’s. The euro zone already has 300 million people;

it would have more than 450 million if Britain, Sweden and the countries of

Central Europe adopted the currency.

Most are eager to do so, believing it will help their populations.

But the price of belonging to a monetary union—obeying strict fiscal

rules and one-size-fits-all interest rates—has made some Central

Europeans relieved that they will not be allowed to adopt the euro until

at least 2007.

“It would be so easy to sell the concept of the euro if there weren’t

these tough requirements,” the prime minister of Hungary, Peter

Medgyessy, said recently in an interview at a conference in Munich. “That

is why we should be very cautious about setting a date for joining the

euro zone.”

Among Western Europeans, feelings are even more ambivalent. Sweden,

which is scheduled to hold a referendum on joining the monetary union in

September, has historically been pro-Europe. But in recent polls, public senti-

ment has swung narrowly against the euro.

Part of the problem is that Swedes fear a strong euro would cripple

their exports. They also point to neighboring Germany, which has limped

through four years with the euro, in part because the tight monetary

policy of the European bank is arguably ill suited to its faltering

economy.

The same arguments are heard in Britain, where the chancellor of the

exchequer, Gordon Brown, is to deliver a judgment next month on whether

the country has met five economic conditions for entry to the union. His ver-

dict is widely expected to be “not yet.”

Mr. Brown’s obdurate resistance has revived rumors of a rift between him

and Prime Minister Tony Blair, who favors the euro. The two men issued a

statement on Friday denying that they were at loggerheads. In one respect,

the rise of the euro should remove a barrier for Britain. Because the pound,

like the dollar, has lost value against the euro, the danger of converting it into

euros at an inflated rate has been mitigated.

“If you lock in the pound at too strong a rate, you run into some of

the same problems Germany did,” said David Walton, the chief European

economist at Goldman Sachs in London. Still, Mr. Walton said Britain’s

reluctance to join the union was driven less by economics than by politics—

springing from inchoate but deeply held notions of sovereignty and

national identity.

Ultimately, the success of the euro will also depend on politics. That is

why the currency’s creators seem quite satisfied with its rebound. While they

recognize it is mostly a reflection of the dollar’s weakness, they relish the

chance to erase the memory of its stumbling start.

SOURCE: Mark Landler, “Euro Beginning to Flex Its Economic Muscles,” New

York Times, 18 May 2003, p. 17. © 2003 New York Times Company. Reprinted

with permission.

CONSIDER THIS:

The exchange rate as of December 8, 2006, is $1.32 per euro.

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:51 AM Page 938

C H A P T E R 3 2

International Finance

939

be supplied at that price; that is, a surplus of euros

will exist. Competition among euro sellers will push

the price of euros down toward equilibrium.

Likewise, if the dollar price of euros is lower than the

equilibrium price, an excess quantity of euros will be

demanded at that price; that is, a shortage of euros

will occur. Competition among euro buyers will push

the price of euros up toward equilibrium.

S E C T I O N

*

C H E C K

1.

The price of a unit of one foreign currency in terms of another is called the exchange rate.

2.

The exchange rate for a currency is determined by the supply of and demand for that currency in the foreign

exchange market.

3.

If the dollar appreciates in value relative to foreign currencies, foreign goods become more inexpensive to U.S.

consumers, increasing U.S. demand for foreign goods.

1.

What is an exchange rate?

2.

When a U.S. dollar buys relatively more British pounds, why does the cost of imports from England fall in the

United States?

3.

When a U.S. dollar buys relatively fewer yen, why does the cost of U.S. exports fall in Japan?

4.

How does an increase in domestic demand for foreign goods and services increase the demand for those foreign

currencies?

5.

As euros get cheaper relative to U.S. dollars, why does the quantity of euros demanded by Americans increase?

Why doesn’t the demand for euros increase as a result?

6.

Who brings exchange rates down when they are above their equilibrium value? Who brings exchange rates up when

they are below their equilibrium value?

S E C T I O N

32.3

E q u i l i b r i u m C h a n g e s i n t h e F o r e i g n

E x c h a n g e M a r k e t

■

What factors cause the demand curve for a

currency to shift?

■

What factors cause the supply curve for a

currency to shift?

DETERMINANTS IN THE FOREIGN

EXCHANGE MARKET

The equilibrium exchange rate of a currency changes

many times daily. Sometimes, these changes can be quite

significant. Any force that shifts either the demand for

or supply of a currency will shift the equilibrium in the

foreign exchange market, leading to a new exchange

rate. Among such factors are changes in consumer tastes

for goods, income levels, relative real interest rates, and

relative inflation rates, as well as speculation.

INCREASED TASTES FOR FOREIGN GOODS

Because the demand for foreign currencies is

derived from the demand for foreign goods, any

change in the U.S. demand for foreign goods will

shift the demand schedule for foreign currency

in the same direction. For example, if a cuckoo

clock revolution sweeps through the United States,

German producers will have reason to celebrate,

knowing that many U.S. buyers will turn to

Germany for their cuckoo clocks. However,

because Germans will only accept payment in the

form of euros, U.S. consumers and retailers must

convert their dollars into euros before they can

purchase their clocks. The increased taste for

European goods in the United States will, there-

fore, lead to an increased demand for euros. As

shown in Exhibit 1, this increased demand for

euros shifts the demand curve to the right, result-

ing in a new, higher equilibrium dollar price of

euros.

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:51 AM Page 939

940

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

RELATIVE INCOME INCREASES OR REDUCTIONS

IN U.S. TARIFFS

Any change in the average income of U.S. consumers

will also change the equilibrium exchange rate, ceteris

paribus. If on the whole incomes were to increase in

the United States, Americans would buy more goods,

including imported goods, hence more European

goods would be bought. This increased demand for

European goods would lead to an increased demand

for euros, resulting in a higher exchange rate for the

euro. A decrease in U.S. tariffs on European goods

would tend to have the same effect as an increase in

incomes, by making European goods more affordable.

Exhibit 1 shows that it would again lead to an increased

demand for European goods and a higher short-run

equilibrium exchange rate for the euro.

EUROPEAN INCOMES INCREASE, REDUCTIONS

IN EUROPEAN TARIFFS, OR CHANGES IN

EUROPEAN TASTES

If European incomes rose, European tariffs on U.S.

goods fell, or European tastes for American goods

increased, the supply of euros in the euro foreign

exchange market would increase. Any of these changes

would cause Europeans to demand more U.S. goods

and therefore more U.S. dollars to purchase those

goods. To obtain these added dollars, Europeans would

have to exchange more of their euros, increasing the

supply of euros on the euro foreign exchange market.

As Exhibit 2 demonstrates, the result would be a right-

ward shift in the euro supply curve, leading to a new

equilibrium at a lower exchange rate for the euro.

HOW DO CHANGES IN RELATIVE REAL INTEREST

RATES AFFECT EXCHANGE RATES?

If interest rates in the United States were to increase rel-

ative to, say, European interest rates, other things being

equal, the rate of return on U.S. investments would

increase relative to that on European investments.

European investors would then increase their demand

for U.S. investments and therefore offer euros for sale

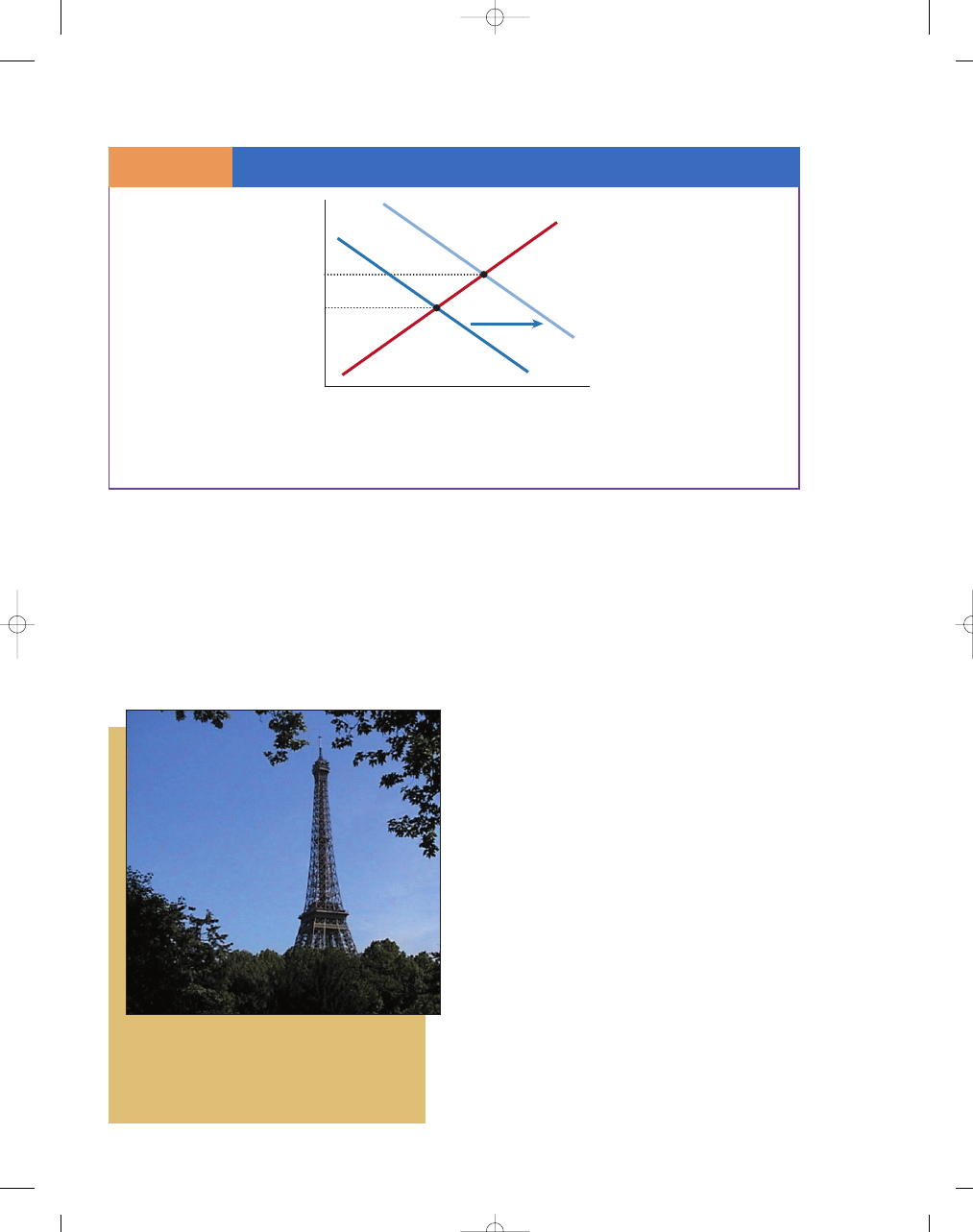

What impact will an increase in travel to Paris by U.S. con-

sumers have on the dollar price of euros? For a consumer to

buy souvenirs at the Eiffel Tower, she will need to exchange

dollars for euros. It will increase the demand for euros and

result in a new, higher dollar price of euros.

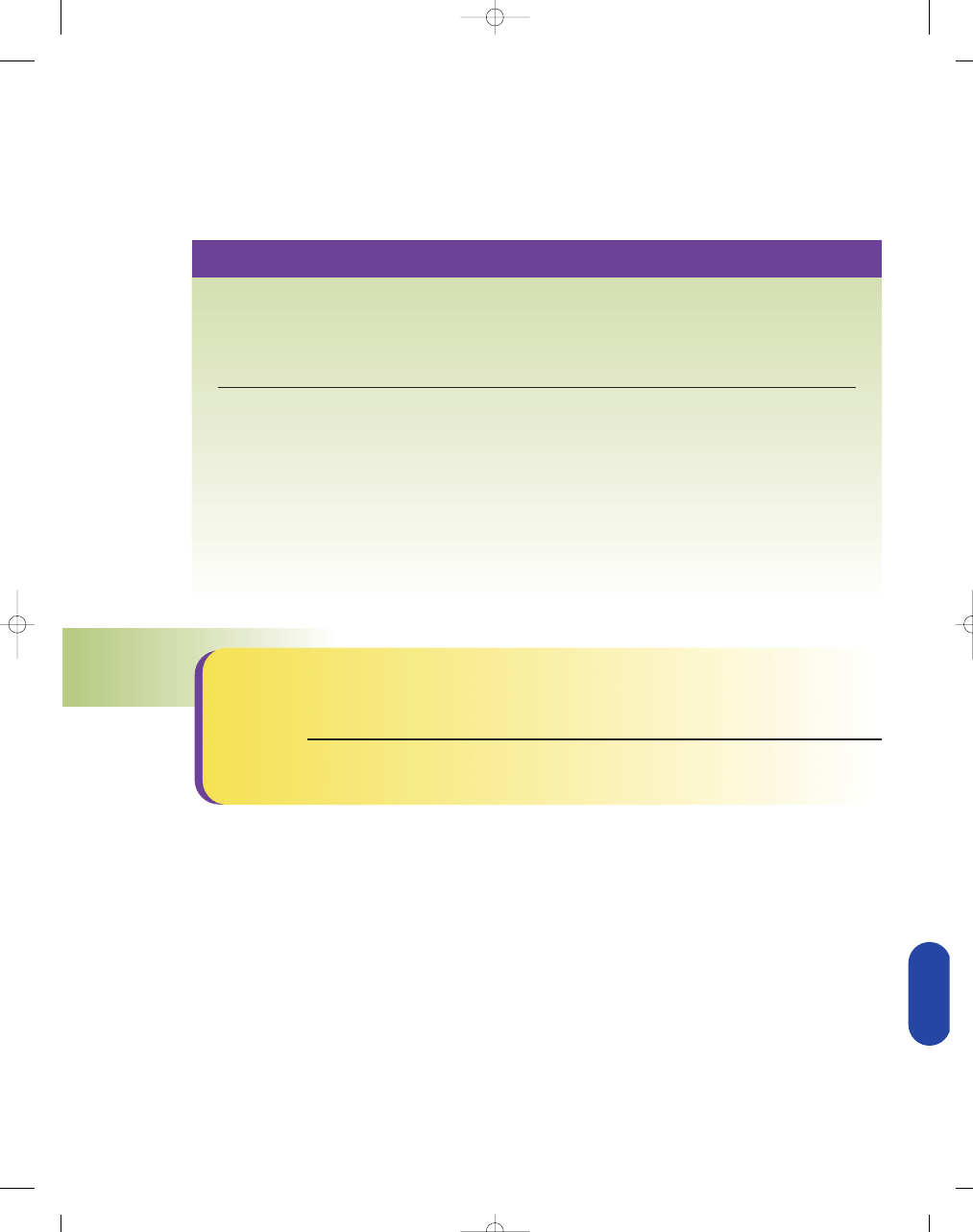

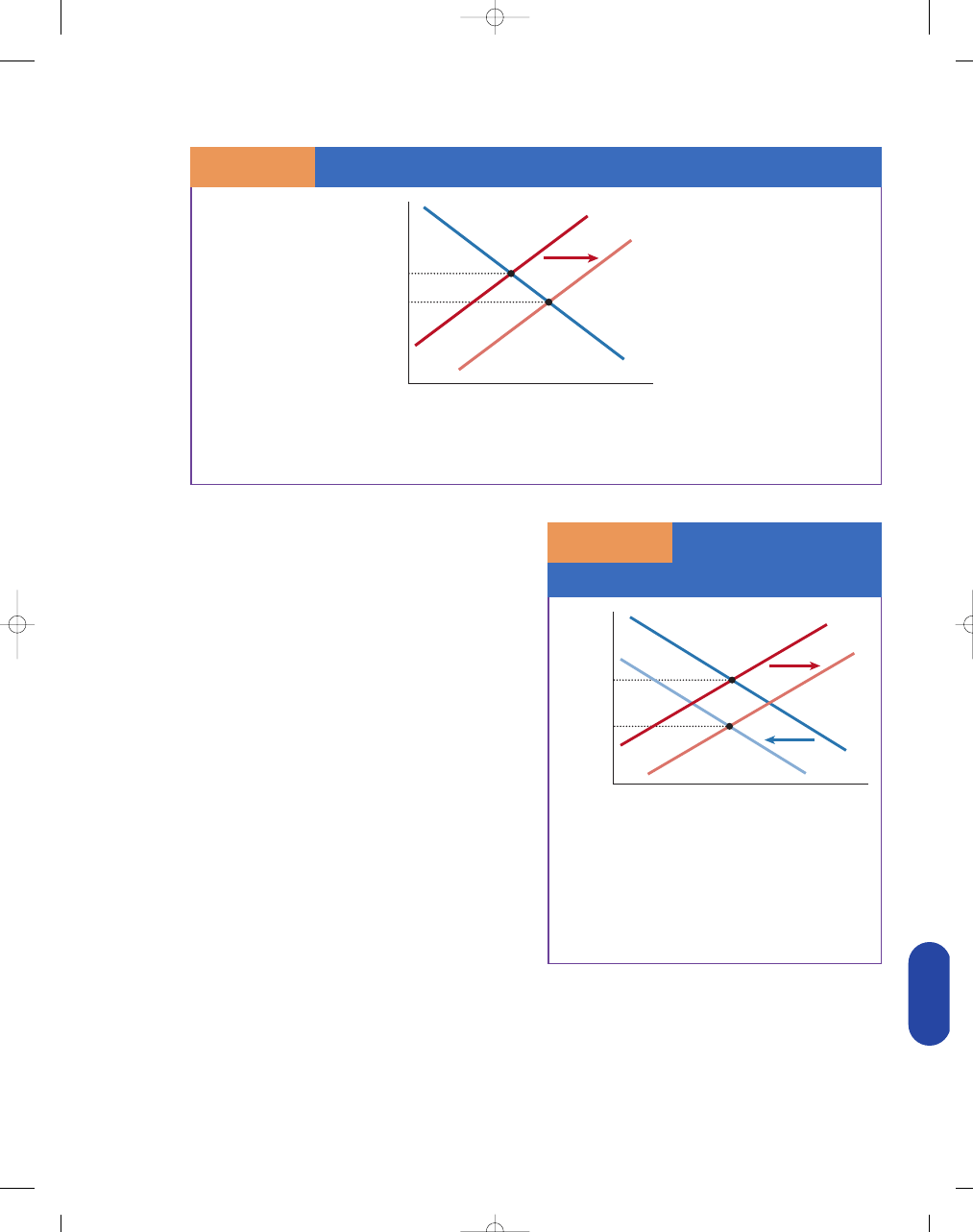

An increase in the taste for European goods, an increase in U.S. incomes, or a decrease in U.S. tariffs can cause an

increase in the demand for euros, shifting the demand for euros to the right from D

1

to D

2

and leading to a higher

equilibrium exchange rate.

Dollar Price of Eur

os

Quantity of Euros

0

$1.50

$1.00

E

2

E

1

D

2

D

1

Supply of euros

Impact on the Foreign Exchange Market of a U.S. Change in Taste,

Income Increase, or Tariff Decrease

S E C T I O N

32 . 3

E

X H I B I T

1

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:51 AM Page 940

C H A P T E R 3 2

International Finance

941

in order to buy dollars to buy U.S. investments, shift-

ing the supply curve for euros to the right, from S

1

to

S

2

in Exhibit 3.

In this scenario, U.S. investors would also shift

their investments away from Europe by decreasing

their demand for euros relative to their demand for dol-

lars, from D

1

to D

2

in Exhibit 3. A subsequent, lower

equilibrium price ($1.50) would result for the euro as a

result of the increase in U.S. interest rates. That is, the

euro would depreciate, because euros could now buy

fewer units of dollars than before. In short, the higher

U.S. interest rates would attract more investment to the

United States, leading to a relative appreciation of the

dollar and a relative depreciation of the euro.

CHANGES IN THE RELATIVE INFLATION RATE

If Europe experienced an inflation rate greater than that

experienced in the United States, other things being

equal, what would happen to the exchange rate? In this

case, European products would become more expensive

to U.S. consumers. Americans would then decrease the

quantity of European goods demanded and thus

decrease their demand for euros. The result would be a

leftward shift of the demand curve for euros.

On the other side of the Atlantic, U.S. goods would

become relatively cheaper to Europeans, leading

Europeans to increase the quantity of U.S. goods

demanded and thus to demand more U.S. dollars. This

increased demand for dollars would translate into an

increased supply of euros, shifting the supply curve for

euros outward. Exhibit 4 shows the shifts of the supply

and demand curves and the new lower equilibrium price

for the euro resulting from the higher European rate.

EXPECTATIONS AND SPECULATION

Every trading day, roughly a trillion dollars in cur-

rency trades hands in the foreign exchange markets.

Suppose currency traders believe that in the future,

the United States will experience more rapid inflation

than will Japan. If currency speculators believe that

the value of the dollar will soon be falling because of

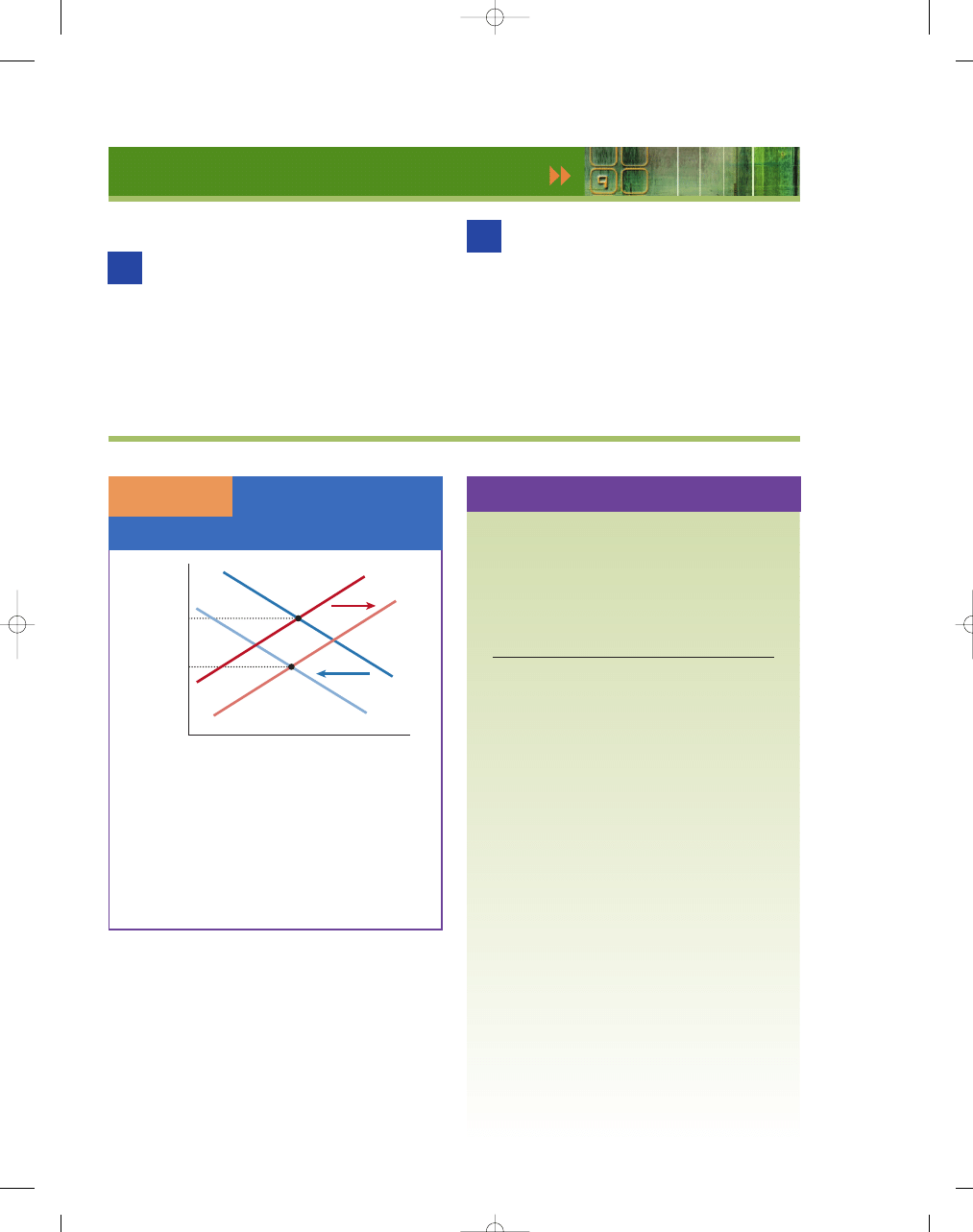

If European incomes increase, European tariffs on U.S. goods fall, or European tastes for American goods increase,

the supply of euros increases. The increase in demand for dollars causes an increase in the supply of euros, shifting

it to the right, from S

1

to S

2

.

Dollar Price of Eur

os

Quantity of Euros

0

$1.50

$1.00

E

2

E

1

S

1

S

2

Demand for euros

Impact on the Foreign Exchange Market of a European Change in Taste,

Income Increase, or Tariff Decrease

S E C T I O N

32 . 3

E

X H I B I T

2

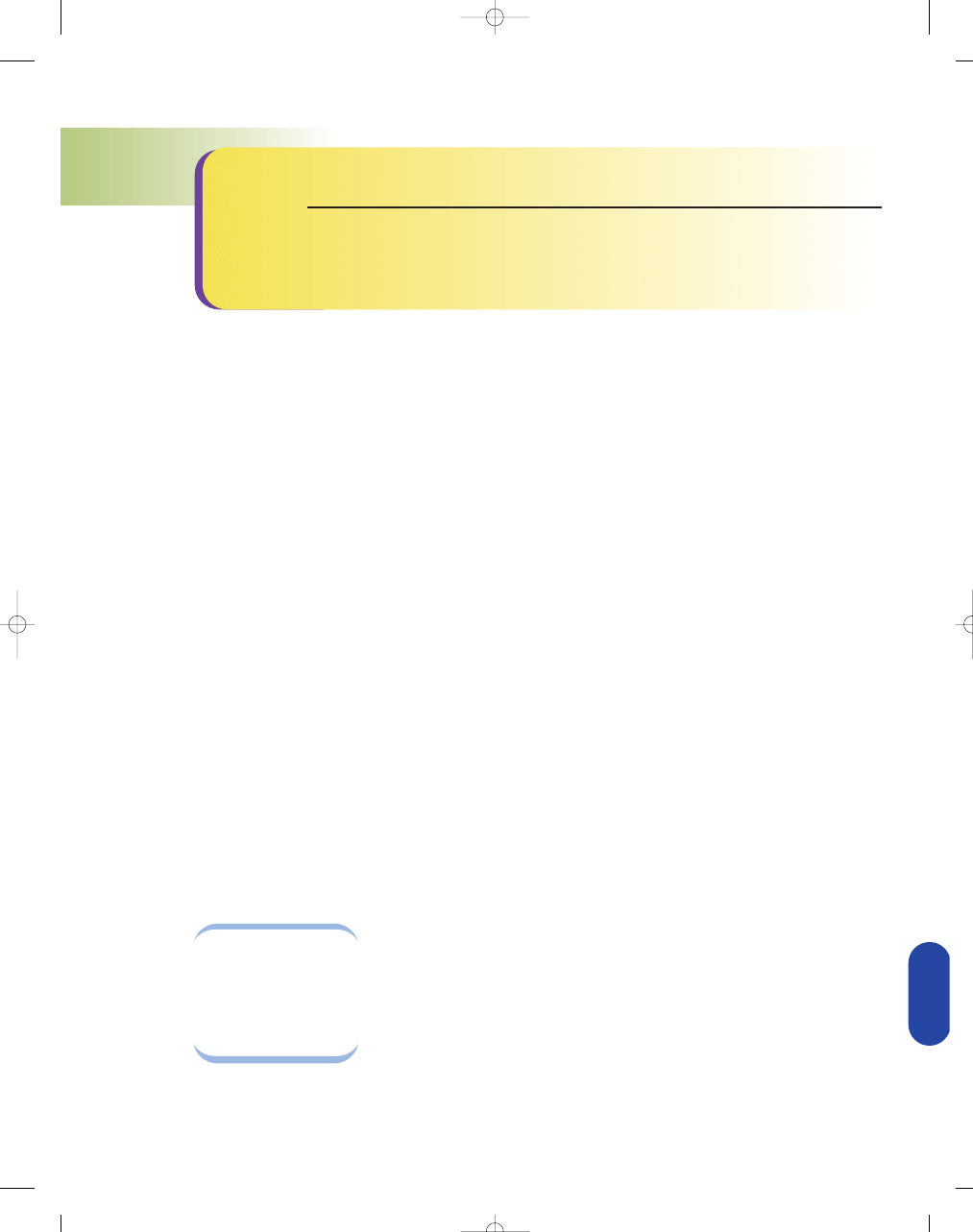

Impact on the Foreign

Exchange Market from

an Increase in the U.S.

Interest Rate

S E C T I O N

32 . 3

E

X H I B I T

3

Dollar Price of Eur

os

Quantity of Euros

0

$1.90

$1.50

E

2

E

1

S

1

S

2

D

1

D

2

When U.S. interest rates increase, European investors

increase their supply of euros to buy dollars—the

supply curve of euros increases from S

1

to S

2

. In addi-

tion, U.S. investors shift their investments away from

Europe, decreasing their demand for euros and shift-

ing the demand curve from D

1

to D

2

. This shift leads

to a depreciation of the euro; that is, euros can now

buy fewer units of dollars.

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:51 AM Page 941

942

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

the anticipated rise in the U.S. inflation rate, those

who are holding dollars will convert them to yen.

This move will lead to an increase in the demand for

yen—the yen appreciates and the dollar depreciates

relative to the yen, ceteris paribus. In short, if

speculators believe that the price of a country’s cur-

rency is going to rise, they will buy more of that cur-

rency, pushing up the price and causing the country’s

currency to appreciate.

using what you’ve learned

Determinants of Exchange Rates

How will each of the following events affect the foreign exchange

market?

a. American travel to Europe increases.

b. Japanese investors purchase U.S. stock.

c. U.S. real interest rates abruptly increase relative to world interest

rates.

d. Other countries become less politically and economically stable relative

to the United States.

a. The demand for euros increases (demand shifts right in the euro

market), the dollar will depreciate, and the euro will appreciate,

ceteris paribus.

b. The demand for dollars increases (demand shifts right in the dollar market), the

dollar will appreciate, and the yen will depreciate, ceteris paribus. Alternatively,

you could think of it as an increase in supply in the yen market.

c. International investors will increase their demand for dollars in the dollar

market to take advantage of the higher interest rates. The dollar will

appreciate relative to other foreign currencies, ceteris paribus.

d. More foreign investors will want to buy U.S. assets, resulting in an increase

in demand for dollars.

Q

A

S E C T I O N

*

C H E C K

1.

Any force that shifts either the demand or the

supply curves for a foreign currency will shift

the equilibrium in the foreign exchange market

and lead to a new exchange rate.

2.

Any changes in tastes, income levels, relative real

interest rates, or relative inflation rates will cause

the demand for and supply of a currency to shift.

1.

Why will the exchange rates of foreign curren-

cies relative to U.S. dollars decline when U.S.

domestic tastes change, reducing the demand

for foreign-produced goods?

2.

Why does the demand for foreign currencies

shift in the same direction as domestic income?

What happens to the exchange value of those

foreign currencies in terms of U.S. dollars?

3.

How would increased U.S. tariffs on imported

European goods affect the exchange value of

euros in terms of dollars?

4.

Why do changes in U.S. tastes, income levels, or

tariffs change the demand for euros, while simi-

lar changes in Europe change the supply of

euros?

5.

What would happen to the exchange value of

euros in terms of U.S. dollars if incomes rose in

both Europe and the United States?

6.

Why does an increase in interest rates in

Germany relative to U.S. interest rates increase

the demand for euros but decrease their supply?

7.

What would an increase in U.S. inflation relative

to Europe do to the supply and demand for

euros and to the equilibrium exchange value

(price) of euros in terms of U.S. dollars?

Impact on the Foreign

Exchange Market from

an Increase in the

European Inflation Rate

S E C T I O N

32 . 3

E

X H I B I T

4

Dollar Price of Eur

os

Quantity of Euros

0

$1.50

$1.00

E

2

E

1

S

1

S

2

D

1

D

2

If Europe experiences a higher inflation rate than does

the United States, European products become more

expensive to U.S. consumers. As a result, those con-

sumers demand fewer euros, shifting the demand for

euros to the left, from D

1

to D

2

. At the same time, U.S.

goods become relatively cheaper to Europeans, who

then buy more dollars by supplying euros, shifting the

euro supply curve to the right, from S

1

to S

2

. The result: a

new, lower equilibrium price for the euro.

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:51 AM Page 942

C H A P T E R 3 2

International Finance

943

THE FLEXIBLE EXCHANGE RATE SYSTEM

Since 1973, the world has essentially operated on a

system of flexible exchange rates. Flexible exchange

rates mean that currency prices are allowed to fluctu-

ate with changes in supply and demand, without gov-

ernments stepping in to prevent those changes. Before

that, governments operated under what was called the

Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system, in which

they would maintain a stable exchange rate by buying

or selling currencies or reserves to bring demand and

supply for their currencies together at the fixed

exchange rate. The present system evolved out of the

Bretton Woods fixed-rate system and occurred by

accident, not design. Governments were unable to

agree on an alternative fixed-rate approach when the

Bretton Woods system collapsed, so nations simply let

market forces determine currency values.

ARE EXCHANGE RATES MANAGED AT ALL?

To be sure, governments sensitive to sharp changes in

the exchange value of their currencies do still intervene

from time to time to prop up their currency’s exchange

rate if it is considered to be too low or falling too rap-

idly, or to depress its exchange rate if it is considered to

be too high or rising too rapidly. Such was the case

when the U.S. dollar declined in value in the late 1970s,

but the U.S. government intervention appeared to have

little if any effect in preventing the dollar’s decline.

However, present-day fluctuations in exchange rates

are not determined solely by market forces. Economists

sometimes say that the current exchange rate system is

a

dirty float system,

meaning that fluctua-

tions in currency values

are partly determined

by market forces and

partly influenced by

government interven-

tion. Over the years,

however, such govern-

mental support attempts have been insufficient to dra-

matically alter exchange rates for long, and currency

exchange rates have changed dramatically.

WHEN EXCHANGE RATES CHANGE

When exchange rates change, they affect not only the

currency market but the product markets as well. For

example, if U.S. consumers were to receive fewer and

fewer British pounds and Japanese yen per U.S. dollar,

the effect would be an increasing price for foreign

imports, ceteris paribus. It would now take a greater

number of dollars to buy a given number of yen or

pounds, which U.S. consumers use to purchase those

foreign products. It would, however, lower the cost of

U.S. exports to foreigners. If, however, the dollar

increased in value relative to other currencies, then the

relative price of foreign goods would decrease, ceteris

paribus. But foreigners would find that U.S. goods were

more expensive in terms of their own currency prices,

and, as a result, would import fewer U.S. products.

THE ADVANTAGES OF FLEXIBLE RATES

As mentioned earlier, the present system of flexible

exchange rates was not planned. Indeed, most central

bankers thought that a system where rates were not

fixed would lead to chaos. What in fact has hap-

pened? Since the advent of flexible exchange rates,

world trade has not only continued but expanded.

Over a one-year period, the world economy adjusted

to the shock of a four-fold increase in the price of its

most important internationally traded commodity,

oil. Although the OPEC oil cartel’s price increase cer-

tainly had adverse economic effects, it did so without

paralyzing the economy of any one nation.

The most important advantage of the flexible-rate

system is that the recurrent crises that led to specula-

tive rampages and major currency revaluations under

the fixed Bretton Woods system have significantly

diminished. Under the fixed-rate system, price changes

in currencies came infrequently, but when they came,

they were of a large magnitude: 20 percent or 30 percent

changes overnight were fairly common. Today, price

changes occur daily or even hourly, but each change is

much smaller in magnitude, with major changes in

exchange rates typically occurring only over periods

of months or years.

S E C T I O N

32.4

F l e x i b l e E x c h a n g e R a t e s

■

How are exchange rates determined today?

■

How are exchange rate changes different

under a flexible-rate system than in a fixed

system?

■

What major problems exist in a fixed-rate

system?

■

What are the major arguments against

flexible rates?

dirty float system

a description of the exchange

rate system that means that

fluctuations in currency values

are partly determined by govern-

ment intervention

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:51 AM Page 943

944

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

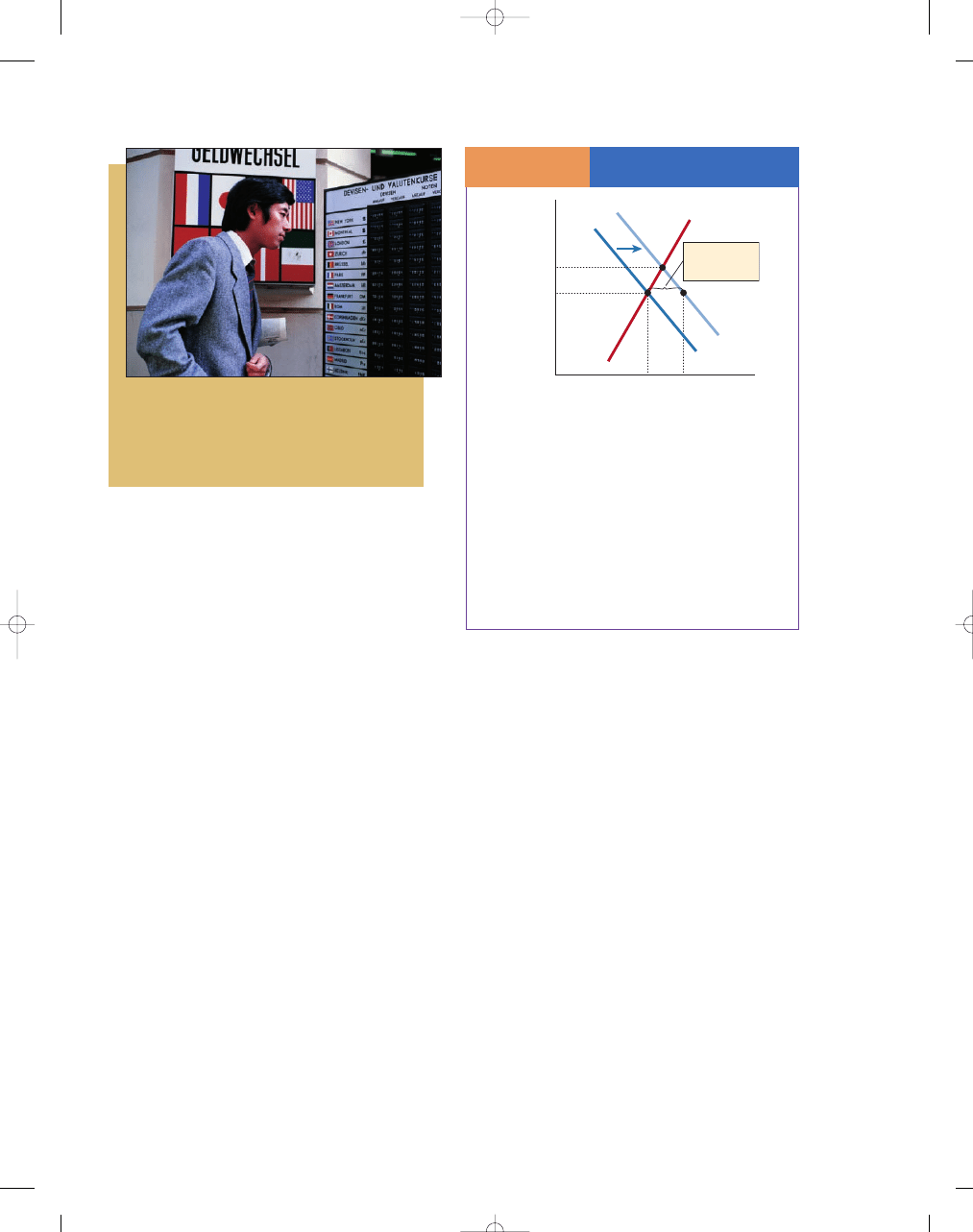

FIXED EXCHANGE RATES CAN RESULT IN

CURRENCY SHORTAGES

Perhaps the most significant problem with the fixed-

rate system is that it can result in currency shortages,

just as domestic price and wage controls lead to short-

ages. Suppose we had a fixed-rate system with the

price of one euro set at $1.00, as shown in Exhibit 1.

In this example, the original quantity of euros

demanded and supplied is indicated by curves D

1

and

S, so $1.00 is the equilibrium price. That is, at a price

of $1.00, the quantity of euros demanded (by U.S.

importers of European products and others wanting

euros) equals the quantity supplied (by European

importers of U.S. products and others).

Suppose that some event happens to increase U.S.

demand for Dutch goods. For this example, let us

assume that Royal Dutch Shell discovers new oil

reserves in the North Sea and thus has a new product

to export. As U.S. consumers begin to demand Royal

Dutch Shell oil, the demand for euros increases. That is,

at any given dollar price of euros, U.S. consumers want

more euros, shifting the demand curve to the right, to

D

2

. Under a fixed exchange rate system, the dollar price

of euros must remain at $1, where the quantity of

euros demanded (Q

2

) now exceeds the quantity sup-

plied, Q

1

. The result is a shortage of euros—a short-

age that must be corrected in some way. As a solution

to the shortage, the United States may borrow euros

from the Netherlands, or perhaps ship the

Netherlands some of its reserves of gold. The ability

to continually make up the shortage (deficit) in this

manner, however, is limited, particularly if the deficit

persists for a substantial time.

FLEXIBLE RATES SOLVE THE CURRENCY

SHORTAGE PROBLEM

Under flexible exchange rates, a change in the supply or

demand for euros does not pose a problem. Because

rates are allowed to change, the rising U.S. demand for

European goods (and thus for euros) would lead to a

new equilibrium price for euros, say at $1.50. At this

higher price, European goods are more costly to U.S.

buyers. Some of the increase in demand for European

imports, then, is offset by a decrease in quantity

demanded resulting from higher import prices.

Similarly, the change in the exchange rate will make U.S.

goods cheaper to Europeans, thus increasing U.S.

exports and, with that, the quantity of euros supplied.

For example, a $40 software program that cost

Europeans 40 euros when the exchange rate was $1 per

euro costs less than 27 euros when the exchange rate

increases to $1.50 per euro ($40 divided by $1.50).

FLEXIBLE RATES AFFECT

MACROECONOMIC POLICIES

With flexible exchange rates, the imbalance between

debits and credits arising from shifts in currency

demand and/or supply is accommodated by changes

How Flexible Exchange

Rates Work

S E C T I O N

32 . 4

E

X H I B I T

1

As increase in demand for euro shifts the demand

curve to the right, from D

1

to D

2

. Under a fixed-rate

system, this increase in demand results in a shortage of

euros at the equilibrium price of $1, because the quan-

tity demanded at this price, Q

2

, is greater than the

quantity supplied, Q

1

. If the exchange rate is flexible,

however, no shortage develops. Instead, the increase in

demand forces the exchange rate higher, to $1.50. At

this higher exchange rate, the quantity of euros

demanded doesn’t increase as much, and the quantity

of euros supplied increases as a result of the now rela-

tively lower cost of imports from the United States.

Dollar Price of Eur

os

0

$1.50

$1.00

S

D

2

D

1

Q

2

Q

1

Quantity of Euros

Payment

deficit with fixed

exchange rate

The exchange rate is the rate at which one country’s currency

can be traded for another country’s currency. Under a flexible-

rate system, the government allows the forces of supply and

demand to determine the exchange rate. Changes in exchange

rates occur daily or even hourly.

©

Photodisc/Getty Images

, Inc.

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:51 AM Page 944

C H A P T E R 3 2

International Finance

945

using what you’ve learned

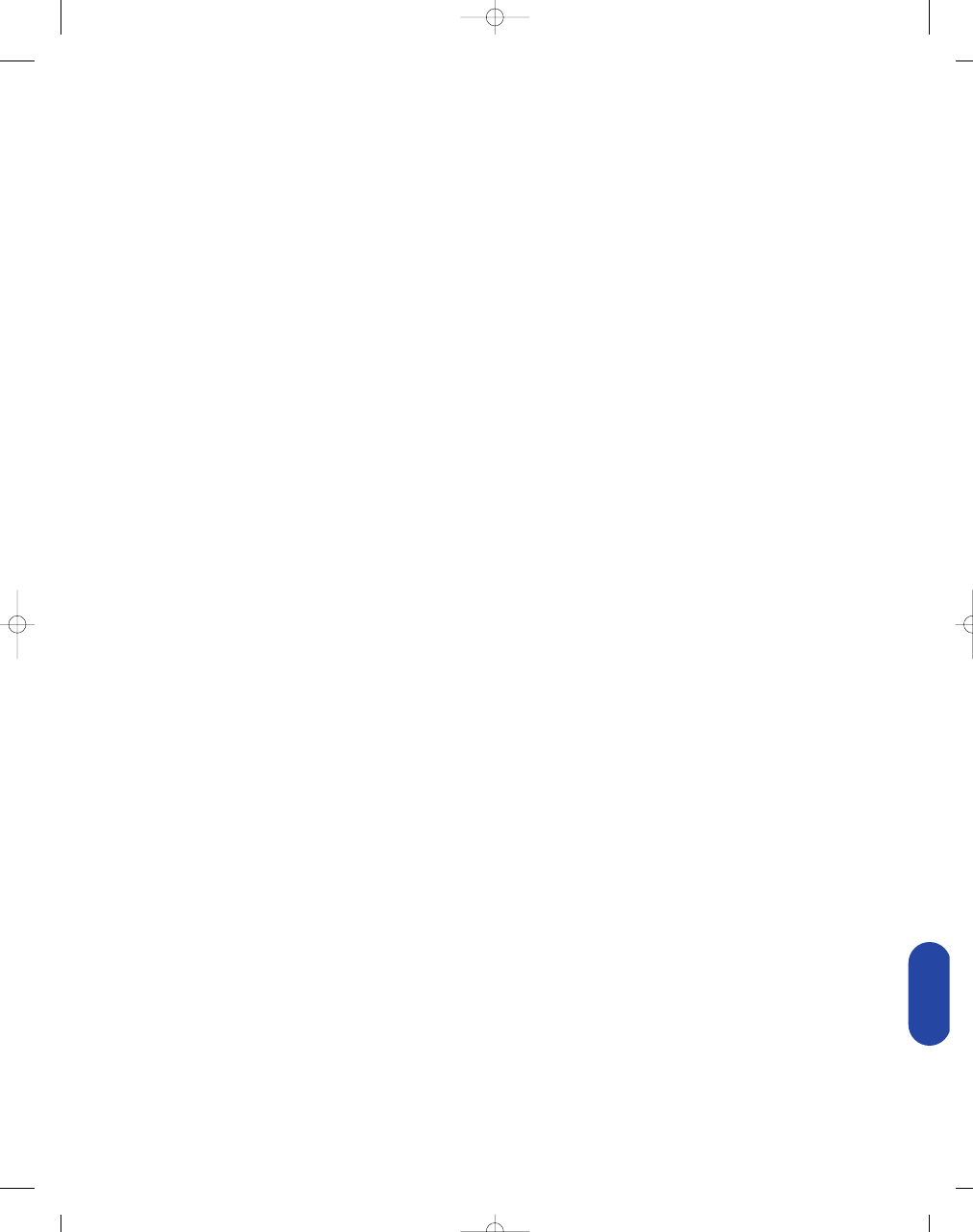

Big Mac Index

The Big Mac index is an informal way of measuring the purchasing power

parity (PPP) between two currencies and provides a test of the extent to

which market exchange rates result in goods costing the same in different

countries.

The Big Mac index was introduced by The Economist newspaper in

September 1986 as a humorous illustration and has been published by that

paper more or less annually since then. The index also gave rise to the word

burgernomics.

One suggested method of predicting exchange rate movements is

that the rate between two currencies should naturally adjust so that a

sample basket of goods and services should cost the same in both cur-

rencies. In the Big Mac index, the “basket” in question is considered to

be a single Big Mac as sold by the McDonald’s fast food restaurant chain.

The Big Mac was chosen because it is available to a common specifica-

tion in many countries around the world, with local McDonald’s fran-

chisees having significant responsibility for negotiating input prices. For

these reasons, the index enables a comparison between many countries’

currencies.

The Big Mac PPP exchange rate between two countries is obtained by

dividing the cost of a Big Mac in one country (in its currency) by the cost of a

Big Mac in another country (in its currency). This value is then compared with

the actual exchange rate; if it is lower, then the first currency is under-valued

(according to PPP theory) compared with the second, and conversely, if it is

higher, then the first currency is over-valued.

For example, suppose a Big Mac costs $2.50 in the United States and

£2.00 in the United Kingdom; thus, the PPP rate is 2.50/2.00

1.25. If, in fact,

the U.S. dollar buys £0.55 (or £1

$1.81), then the pound is over-valued

(1.81

>

1.25) with the respect to the dollar by 44.8% in comparison with the

costs of the Big Mac in both countries (information as of 2005).

In January 2004, The Economist introduced a sister Tall Latte index. The

idea is the same, except that the Big Mac is replaced by a cup of Starbucks

coffee, acknowledging the global spread of that chain in recent years. In a sim-

ilar vein, in 1997, the newspaper drew up a “Coca-Cola map” that showed a

strong positive correlation between the amount of Coke consumed per capita

in a country and that country’s wealth.

The burger methodology has limitations in its estimates of the PPP. In

many countries, eating at international fast food chain restaurants such as

McDonald’s is relatively expensive in comparison to eating at a local restau-

rant, and the demand for Big Macs is not as large in countries like India as in

the United States. Whereas low income Americans may eat at McDonald’s a

few times a week, low income Malaysians probably never eat Big Macs. Social

status of eating at fast food restaurants like McDonald’s, local taxes, levels of

competition, and import duties for burgers may not be representative of the

country’s economy as a whole. In addition, there is no theoretical reason why

non-tradable goods and services such as property costs should be equal in dif-

ferent countries. Nevertheless, the Big Mac index has become widely cited by

economists.

SOURCE: From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

©

T

err

i Miller/E-Visual Comm

unications Inc.

in currency prices, rather than through the special

financial borrowings or reserve movements necessary

with fixed rates. In a pure flexible exchange rate

system, deficits and surpluses in the balance of pay-

ments tend to disappear automatically. The market

mechanism itself is able to address world trade imbal-

ances, dispensing with the need for bureaucrats

attempting to achieve some administratively deter-

mined price. Moreover, the need to use restrictive

monetary and/or fiscal policy to end such an imbal-

ance while maintaining a fixed exchange rate is allevi-

ated. Nations are thus able to feel less constraint in

carrying out internal macroeconomic policies under flex-

ible exchange rates. For these reasons, many economists

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:51 AM Page 945

946

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

welcomed the collapse of the Bretton Woods system

and the failure to arrive at a new system of fixed or

quasi-fixed exchange rates.

THE DISADVANTAGES OF FLEXIBLE RATES

Despite the fact that world trade has grown and deal-

ing with balance-of-payments problems has become

less difficult, flexible exchange rates have not been

universally endorsed by everyone. Several disadvan-

tages of this system have been cited.

Flexible Rates and World Trade

Traditionally, the major objection to flexible rates

was that they introduce considerable uncertainty

into international trade. For example, if you order

some perfume from France with a commitment to

pay 1,000 euros in three months, you are not cer-

tain what the dollar price of euros, and therefore of

the perfume, will be three months from now,

because the exchange rate is constantly fluctuating.

Because people prefer certainty to uncertainty and

are generally risk averse, this uncertainty raises the

costs of international transactions. As a result, flex-

ible exchange rates can reduce the volume of trade,

thus reducing the potential gains from international

specialization.

Proponents of flexible rates have three answers

to this argument. First, the empirical evidence

shows that international trade has, in fact, grown in

volume faster since the introduction of flexible

rates. The exchange rate risk of trade has not had

any major adverse effect. Second, it is possible to, in

effect, buy insurance against the proposed adverse

effect of currency fluctuations. Rather than buying

currencies for immediate use in what is called the

“spot” market for foreign currencies, one can con-

tract today to buy foreign currencies in the future at

a set exchange rate in the “forward” or “futures”

market. By using this market, a perfume importer

can buy euros now for delivery to her in three

months; in doing so, she can be certain of the dollar

price she is paying for the perfume. Since floating

exchange rates began, booming futures markets in

foreign currencies have opened in Chicago, New

York, and in foreign financial centers. The third

argument is that the alleged certainty of currency

prices under the old Bretton Woods system was fic-

titious, because the possibility existed that nations

might, at their whim, drastically revalue their currencies

to deal with their own fundamental balance-of-

payments problems. Proponents of flexible rates,

then, argue that they are therefore no less disruptive

to trade than fixed rates.

Flexible Rates and Inflation

A second, more valid criticism of flexible exchange

rates is that they can contribute to inflationary pres-

sures. Under fixed rates, domestic monetary and fiscal

authorities have an incentive to constrain their domes-

tic prices, because lower domestic prices increase the

attractiveness of exported goods. This discipline is not

present to the same extent with flexible rates. The con-

sequence of a sharp monetary or fiscal expansion

under flexible rates would be a decline in the value of

one’s currency relative to those of other countries. Yet

even that may not seem to be as serious a political con-

sequence as the Bretton Woods solution of an abrupt

devaluation of the currency in the face of a severe

balance-of-payments problem.

Advocates of flexible rates would argue that infla-

tion need not occur under flexible rates. Flexible rates

do not cause inflation; rather, it is caused by the expan-

sionary macroeconomic policies of governments and

central banks. Actually, flexible rates give government

decision makers greater freedom of action than fixed

rates; whether they act responsibly is determined not

by exchange rates but by domestic policies.

S E C T I O N

*

C H E C K

1.

Today, rates are free to fluctuate based on market transactions, but governments occasionally intervene to increase

or depress the price of their currencies.

2.

Changes in exchange rates occur more often under a flexible-rate system, but the changes are much smaller than

the drastic, overnight revaluations of currencies that occurred under the fixed-rate system.

3.

Under a fixed-rate system, the supply and demand for currencies shift, but currency prices are not allowed to shift

to the new equilibrium, leading to surpluses and shortages of currencies.

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:51 AM Page 946

C H A P T E R 3 2

International Finance

947

4.

The main arguments presented against flexible exchange rates are that international trade levels will be

diminished due to uncertainty of future currency prices and that the flexible rates would lead to inflation.

Proponents of flexible exchange rates have strong counter-arguments to those views.

1.

What are the arguments for and against flexible exchange rates?

2.

When the U.S. dollar starts to exchange for fewer Japanese yen, other things equal, what happens to U.S. and

Japanese imports and exports as a result?

3.

Why is the system of flexible exchange rates sometimes called a dirty float system?

4.

Were exchange rates under the Bretton Woods system really stable? How could you argue that exchange rates

were more uncertain under the fixed-rate system than with floating exchange rates?

5.

What is the uncertainty argument against flexible exchange rates? What evidence do proponents of flexible

exchange rates cite in response?

6.

Do flexible exchange rates cause higher rates of inflation? Why or why not?

I n t e r a c t i v e S u m m a r y

Fill in the blanks:

1. A current account is a record of a country’s current

and of

goods

and services.

2. Because the United States gains claims over foreign

buyers by obtaining foreign currency in exchange for

the dollars needed to buy U.S. exports, all exports of

U.S. goods abroad are considered a(n)

or

item in the U.S. balance of

payments.

3. Nations import and export

, such

as tourism, as well as

(goods).

4. The merchandise import/export relationship is often

called the balance of

.

5. Foreigners buying U.S. goods must

their currencies to obtain

in order

to pay for exported goods.

6. The price of a unit of one foreign currency in terms of

another is called the

.

7. A change in the euro-dollar exchange rate from

$1 per euro to $2 per euro would

the U.S. price of German goods, thereby

the number of German goods that would be demanded

in the United States.

8. The demand for foreign currencies is a derived demand

because it derives directly from the demand for foreign

or for foreign

.

9. The more foreigners demand U.S. products, the

of their currencies they will supply

in exchange for U.S. dollars.

10. The supply of and demand for a foreign currency deter-

mine the equilibrium

of that currency.

11. The quantity of euros demanded by U.S. consumers

will increase to buy more European goods as the price

of the euro

.

12. As the price, or value, of the euro increases relative to

the dollar, American products become relatively

expensive to European buyers,

which will

the quantity of dollars

they will demand.

13. The supply curve of a foreign currency is

sloping.

14. If the dollar price of euros is higher than the equilib-

rium price, an excess quantity of euros will be

at that price, and competition

among euro

will push the price

of euros

toward equilibrium.

15. An increased demand for euros will result in a(n)

equilibrium price (exchange value)

for euros, while a decreased demand for euros will

result in a(n)

equilibrium price

(exchange value) for euros.

16. Changes in a currency’s exchange rate can be

caused by changes in

for goods,

changes in

, changes in relative

rates, changes in relative

rates, and

.

17. An increase in tastes for European goods in the

United States would

the demand

for euros, thereby

the equilibrium

price (exchange value) of euros.

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:51 AM Page 947

948

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

A

nswers: 1.

imports; exports

2.credit; plus

3.services; merchandise

4.trade

5.sell; U.S. dollars

6.exchange rate

7.increase; reducing

8.goods and services; capital

9.more

10.exchange rate

11.falls

12.less; increase

13.upward

14.supplied; sellers; down

15.higher;

lower

16.tastes; income; real interest; inflation; speculation

17.increase; increasing

18.decrease; decrease; lower

19.rose; increased

increased

20.increase; increasing

21.more; decreasing; decreasing

K e y Te r m s a n d C o n c e p t s

balance of payments 932

current account 932

balance of trade 934

capital account 934

exchange rate 936

derived demand 936

dirty float system 943

S e c t i o n C h e c k A n s w e r s

32.1 The Balance of Payments

1. What is the balance of payments?

The balance of payments is the record of all the

international financial transactions of a nation—both

those involving inflows of funds and those involving

outflows of funds—over a year.

2. Why must British purchasers of U.S. goods and

services first exchange pounds for dollars?

Since U.S. goods and services are priced in dollars, a

British consumer who wants to buy U.S. goods must

first buy dollars in exchange for British pounds

before he can buy the U.S. goods and services with

dollars.

3. How is it that our imports provide foreigners with the

means to buy U.S. exports?

The domestic currency Americans supply in exchange

for the foreign currencies to buy imports also supplies

the dollars with which foreigners can buy American

exports.

4. What would have to be true for the United States

to have a balance-of-trade deficit and a balance-of-

payments surplus?

A balance-of-trade deficit means that we imported

more merchandise (goods) than we exported. A balance-

of-payments surplus means that the sum of our goods

and services exports exceeded the sum of our goods

and services imports, plus funds transfers from the

United States. For both to be true would require a

larger surplus of services (including net investment

income) and/or net fund transfer inflows than our

trade deficit in merchandise (goods).

5. What would have to be true for the United States to

have a balance-of-trade surplus and a current account

deficit?

A balance-of-trade surplus means that we exported

more merchandise (goods) than we imported. A cur-

rent account deficit means that our exports of goods

and services (including net investment income) were

less than the sum of our imports of goods and

18. A decrease in incomes in the United States

would

the amount of European

imports purchased by Americans, which would

the demand for euros, resulting in

a(n)

exchange rate for euros.

19. If European incomes

, European

tariffs on U.S. goods

, or European

tastes for U.S. goods

, Europeans

would demand more U.S. goods, leading them to

increase their supply of euros to obtain the added dol-

lars necessary to make those purchases.

20. If interest rates in the United States were to

increase relative to European interest rates,

other things being equal, the rate of return on

U.S. investments would

relative to that on European investments, thereby

Europeans’ demand for U.S.

investments.

21. If Europe experienced a higher inflation rate than the

United States, European products would become

expensive to U.S. consumers,

thereby

the quantity of European

goods demanded by Americans, and thus

the demand for euros.

95469_32_Ch32_p931-960.qxd 5/1/07 10:51 AM Page 948

C H A P T E R 3 2

International Finance

949

services, plus net fund transfers. For both to happen

would require that the sum of our deficit in services

plus net transfers must be greater than our surplus in

merchandise (goods) trading.

6. With no errors or omissions in the recorded balance-of-

payments accounts, what should the statistical discrep-

ancy equal?

If there were no errors or omissions in the recorded

balance-of-payments accounts, the statistical discrep-

ancy should equal zero, since when properly recorded,

credits and debits must be equal because every credit

creates a debit of equal value.

7. A Nigerian family visiting Chicago enjoys a Chicago

Cubs baseball game at Wrigley Field. How would

this expense be recorded in the balance-of-payments

accounts? Why?

This would be counted as an export of services,

because it would provide Americans with foreign

currency (a claim against Nigeria) in exchange for

those services.

32.2 Exchange Rates

1. What is an exchange rate?

An exchange rate is the price in one country’s cur-

rency of one unit of another country’s currency.

2. When a U.S. dollar buys relatively more British

pounds, why does the cost of imports from England

fall in the United States?

When a U.S. dollar buys relatively more British

pounds, the cost of imports from England falls in

the United States because it takes fewer U.S. dollars

to buy a given number of British pounds in order

to pay English producers. In other words, the price

in U.S. dollars of English goods and services has

fallen.

3. When a U.S. dollar buys relatively fewer yen, why

does the cost of U.S. exports fall in Japan?

When a U.S. dollar buys relatively fewer yen, the cost

of U.S. exports falls in Japan because it takes fewer

yen to buy a given number of U.S. dollars in order to

pay American producers. In other words, the price in

yen of U.S. goods and services has fallen.

4. How does an increase in domestic demand for foreign

goods and services increase the demand for those

foreign currencies?

An increase in domestic demand for foreign goods

and services increases the demand for those foreign

currencies because the demand for foreign currencies

is derived from the demand for foreign goods and

services and foreign capital. The more foreign goods

and services are demanded, the more of that foreign

currency that will be needed to pay for those goods

and services.

5. As euros get cheaper relative to U.S. dollars, why

does the quantity of euros demanded by Americans

increase? Why doesn’t the demand for euros increase

as a result?

As euros get cheaper relative to U.S. dollars,

European products become relatively more inexpen-

sive to Americans, who therefore buy more European

goods and services. To do so, the quantity of euros

demanded by U.S. consumers will rise to buy them, as

the price (exchange rate) for euros falls. The demand

(as opposed to quantity demanded) of euros doesn’t

increase because this represents a movement along the

demand curve for euros caused by a change in

exchange rates, rather than a change in demand for

euros caused by some other factor.

6. Who brings exchange rates down when they are

above their equilibrium value? Who brings exchange

rates up when they are below their equilibrium value?

When exchange rates are greater than their equi-

librium value, there will be a surplus of the cur-

rency, and frustrated sellers of that currency will

bring its price (exchange rate) down. When