31

C H A P T E R

conomics is largely about exchange. But up to

this point we have focused on trade between

individuals within the domestic economy. In

this chapter, we extend our coverage to inter-

national trade. Why do countries trade? Hong

Kong has no oil—how are they going to get it?

What is comparative advantage? Bananas could be

grown in the most tropical parts of the United

States or in expensive greenhouses, but wouldn't it

be easier to import bananas from Honduras?

Stop for a moment and imagine a world with-

out international trade. Chocolate is derived from

cocoa beans that are imported from South America

and Africa. There are imported cars from Germany

and Japan, shoes and sweaters from Italy, shirts from

India, and watches and clocks from Switzerland.

Consumers love trade because it provides us with

more choices. It is good for producers, too; and the

speed of transportation and communication has

opened up world markets. In addition, lower costs

are sometimes the result of economies of scale.

Free trade gives firms access to large world mar-

kets. It also fosters more competition, which helps

to keep prices down.

In this chapter, we will study the theoretical rea-

sons for the importance of trade. We will also look at

the arguments for and against trade protection.

■

31.1

The Growth in World Trade

31.2

Comparative Advantage and Gains

from Trade

31.3

Supply and Demand in International

Trade

31.4

Tariffs, Import Quotas, and Subsidies

E

I

N T E R N A T I O N A L

T

R A D E

I

N T E R N A T I O N A L

T

R A D E

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 899

900

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

IMPORTANCE OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE

In a typical year, about 15 percent of the world’s

output is traded in international markets. Of course,

the importance of the international sector varies

enormously from place to place across the world.

Some nations are virtually closed economies (no inter-

action with other economies), with foreign trade equal-

ing only a small proportion (perhaps 5 percent) of total

output, while in other countries, trade is much more

important. In the last three decades, the sum of U.S.

S E C T I O N

31.1

T h e G r o w t h i n W o r l d Tr a d e

■

What has happened to the volume of

international trade over time?

■

Who trades with the United States?

■

What does the United States export? Import?

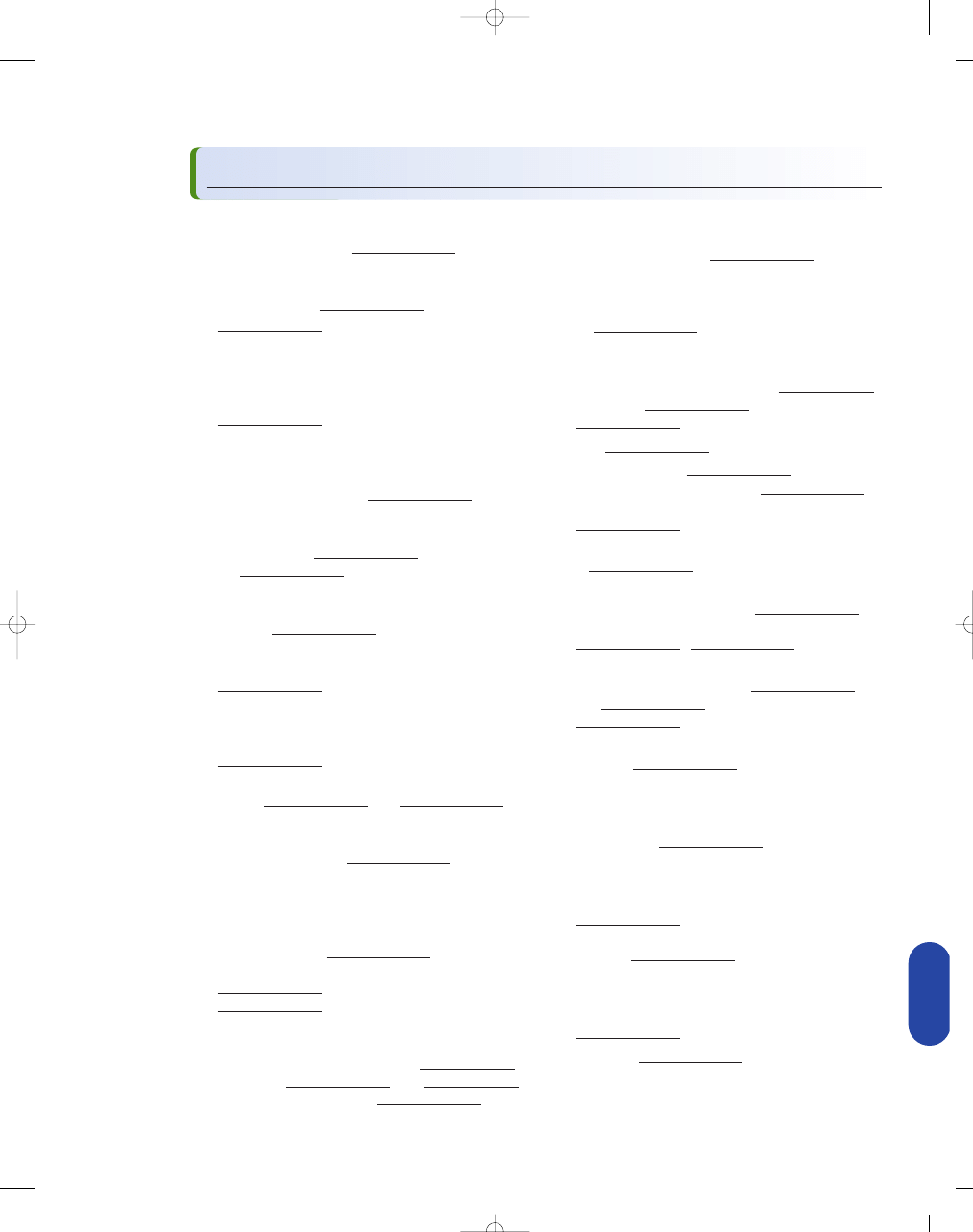

Major U.S. Trading Partners

S E C T I O N

3 1 .1

E

X H I B I T

1

Top Five Trading Partners—Exports of Goods in 2005

Rank

Country

Percent of Total

1

Canada

23.4%

2

Mexico

13.3

3

Japan

6.1

4

China

4.6

5

United Kingdom

4.3

Top Five Trading Partners—Imports of Goods in 2005

Rank

Country

Percent of Total

1

Canada

16.9%

2

China

15.0

3

Mexico

10.0

4

Japan

8.2

5

Germany

5.0

SOURCE: CIA, The World Factbook 2006.

Demand Shifts

S E C T I O N

3 1 .1

E

X H I B I T

2

Top Imports (billions of dollars)

$8.6 Shoes

6.1 Toys

5.6 Input-output units

5.1 Data-processing machine parts

3.2 VCRs

2.6 Wood furniture

2.0 Transmission equipment

1.7 Data-storage units

1.6 Christmas items

1.6 Video games

1.6 Telephone sets

1.4 Sweaters and pullovers

Top Imports (percentage of all imports)

88% Radios

87

Christmas and festive items

83

Toys

70

Leather goods

67

Shoes

67

Handbags

65

Lamps and lights

64

Cases for cameras, eyeglasses, etc.

60

Drills, power tools

56

Household plastics

54

Sporting goods

53

Ceramic kitchenware

The United States Stocking Up on Chinese Goods

©

F

eder

al Reser

v

e Bank of Dallas

You don’t have to shop at Pier 1 Imports to see “Made In China.” A trip to just about any major U.S. retailer—

Wal-Mart, Best Buy, Toys “R” Us, Banana Republic—will turn up troves of Chinese imports that we enjoy in every-

day life. It adds up to roughly 10 percent of overall U.S. imports, up from just 0.5 percent in 1980. The United

States gets 88% of imported radios from China and 83% of imported toys. In 2002, the United States imported

$8 billion worth of shoes from China. What would we do without China? Pay more and have less, that’s for sure.

SOURCE: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Annual Report 2002.

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 900

C H A P T E R 3 1

International Trade

901

imports and exports has increased from 11 percent of

GDP to roughly 30 percent. In addition, incoming

and outgoing investments (capital flows) have risen

from less than 1 percent to roughly 3 percent of GDP.

In Germany, roughly 30 percent of all output pro-

duced is exported, while Ireland and Belgium each

export more than 70 percent of GDP.

U.S. exports include capital goods, automobiles,

industrial supplies, raw materials, consumer goods,

and agricultural products. U.S. imports include crude

oil and refined petroleum products, machinery, auto-

mobiles, consumer goods, industrial raw materials,

food, and beverages.

TRADING PARTNERS

In the early history of the United States, international

trade largely took place with Europe and with Great

Britain in particular. Now the United States trades

with a number of countries, the most important of

which are shown in Exhibit 1. The single most impor-

tant U.S. trading partner is Canada, accounting for

roughly one-fifth of imports and one-fourth of exports.

Trade with Japan, Mexico, Germany, China, Taiwan,

and the United Kingdom is also particularly impor-

tant. Exhibit 2 illustrates the significance of U.S. trade

with China.

S E C T I O N

*

C H E C K

1.

The volume of international trade has increased substantially in the United States over the last 30 years. During

that time, exports and imports have grown from 11 percent to 30 percent of GDP.

2.

Our single most important trading partner, Canada, accounts for roughly one-fourth of our exports and almost

one-fifth of our imports. Trade with Japan, Mexico, China, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Taiwan is also

particularly important to the United States.

3.

U.S. exports include capital goods, automobiles, industrial supplies, raw materials, consumer goods, and agricultural

products. U.S. imports include crude oil and refined petroleum products, machinery, automobiles, consumer goods,

industrial raw materials, food, and beverages.

1.

Why is it important to understand the effects of international trade?

2.

Why would U.S. producers and consumers be more concerned about Canadian trade restrictions than Swedish

trade restrictions?

ECONOMIC GROWTH AND TRADE

Using simple logic, we conclude that the very existence

of trade suggests that trade is economically beneficial.

Our conclusion is true if we assume that people are

utility maximizers and are rational, are intelligent, and

engage in trade on a voluntary basis. Because almost all

trade is voluntary, it would seem that trade occurs

because the participants feel that they are better off

because of the trade. Both participants in an exchange

of goods and services anticipate an improvement in

their economic welfare. Sometimes, of course, anticipa-

tions are not realized (because the world is uncertain);

but the motive behind trade remains an expectation of

some enhancement in utility or satisfaction by both

parties.

S E C T I O N

31.2

C o m p a r a t i v e A d v a n t a g e

a n d G a i n s f r o m Tr a d e

■

Does voluntary trade lead to an improvement

in economic welfare?

■

What is the principle of comparative

advantage?

■

What benefits are derived from

specialization?

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 901

902

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

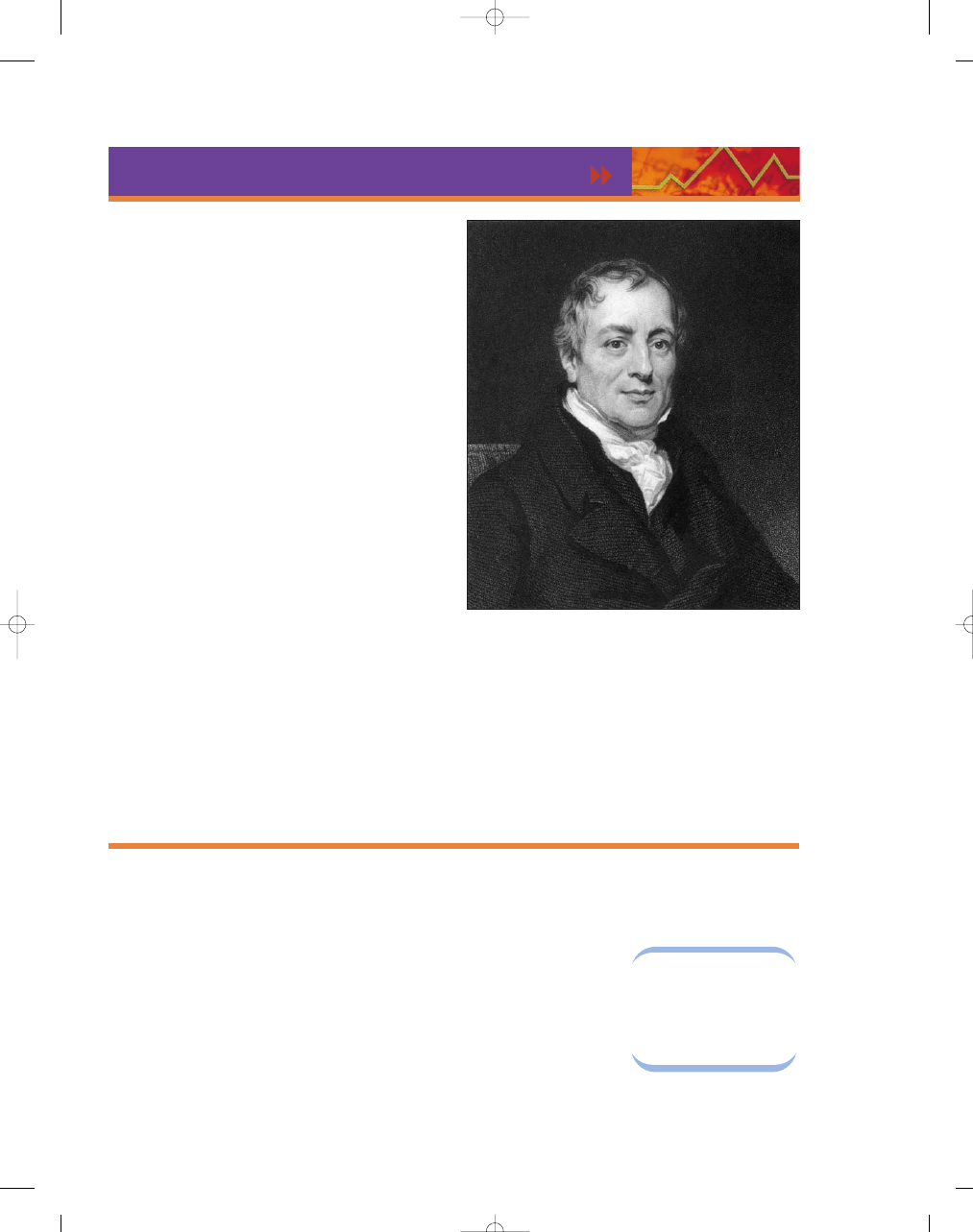

Granted, “trade must be good because people

do it” is a rather simplistic explanation. The classical

economist David Ricardo is usually given most of the

credit for developing the economic theory that more

precisely explains how trade can be mutually beneficial

to both parties, raising output and income levels in

the entire trading area.

THE PRINCIPLE OF COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

Ricardo’s theory of international trade centers on the

concept of comparative advantage. Persons, regions,

or countries can gain by specializing in the production

of the good in which they have a comparative

advantage. That is, if they can produce a good or

service at a lower oppor-

tunity cost than others,

we say that they have a

comparative advan-

tage

in the production

of that good or service.

In other words, a coun-

try or a region should

specialize in producing

and selling those items that it can produce at a lower

opportunity cost than other regions or countries.

David Ricardo (1772–1823)

David Ricardo was born in London to a wealthy, Jewish immigrant stockbro-

ker, the third of 17 children. His father trained him in the stock brokerage

business, which he entered at age 14. At 21, he married a young Quaker

woman, leaving the Jewish faith to become a Unitarian. This upset his

father, who disowned David. The young Ricardo joined a bank and entered

the stock market on his own. He was very successful in this enterprise,

making millions of pounds and quickly surpassing the wealth accumulated

by his father, with whom he later reconciled. Ricardo retired from the stock

exchange business at age 43 and died of an ear infection at 51, leaving

behind a large fortune.

Ricardo could accredit much of his success in the stock market to his bril-

liant ability to predict human nature and public reaction. As a member of the

House of Commons, he was also an undaunted advocate of government

reform, religious and political freedom, and free trade. A man of firm convic-

tions, he often lobbied for class-leveling policies that conflicted with his per-

sonal interests as a landowner and a man of wealth.

In his late 20s, while vacationing in Bath, England, Ricardo picked up

a copy of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations and became interested in

economics. It was a few years later that Ricardo, who had no formal edu-

cation past age 14, improved upon Smith’s principle of absolute advantage.

Ricardo’s ideas, though difficult for many of his fellow politicians to under-

stand, were ingenious.

Smith argued that two countries should engage in trade if one was

better at producing one good than the other—absolute advantage. For exam-

ple, if one country is better at producing hats and the other at producing

shoes, the two countries can produce more total output by producing those

goods that they can produce best. However, Ricardo demonstrated that even

if one country was absolutely more productive than another in making all

goods and services, it would still be mutually beneficial for the two coun-

tries to engage in trade, as each had a comparative advantage in one of

the goods.

Ricardo argued this point at a time in British history when the wealthy

landowners, who had a clutch on parliament, had a virtual monopoly on grain

in England in the form of the Corn Laws, passed in 1815. These acts prevented

the importation of grain from France, although, as Ricardo argued, France

could afford to feed the British for less than it would cost them to feed them-

selves. Despite Ricardo’s argument and the fact that English laborers were

spending one-fourth of their income on bread, the Corn Laws persisted until

1846. Ricardo did, however, leave behind a remarkable concept that convinced

future economists that free trade is almost always in the best interest of an

economy as a whole.

©

Hulton Archiv

e/Getty Images

g r e a t e c o n o m i c t h i n k e r s

comparative

advantage

occurs when a person or country

can produce a good or service at a

lower opportunity cost than others

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 902

C H A P T E R 3 1

International Trade

903

Comparative advantage analysis does not mean

that nations or areas that export goods will necessarily

be able to produce those goods or services more

cheaply than other nations in an absolute sense. What

is important is comparative advantage, not absolute

advantage. For example, the United States may be

able to produce more cotton cloth per worker than

India can, but this capability does not mean that the

United States should necessarily sell cotton cloth to

India. For a highly productive nation to produce

goods in which it is only marginally more produc-

tive than other nations, the nation must take

resources from the production of other goods in

which its productive abilities are markedly superior.

As a result, the opportunity costs in India of making

cotton cloth may be less than in the United States.

With that, both can gain from trade, despite poten-

tial absolute advantages for every good in the

United States.

COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE AND THE PRODUCTION

POSSIBILITIES CURVE

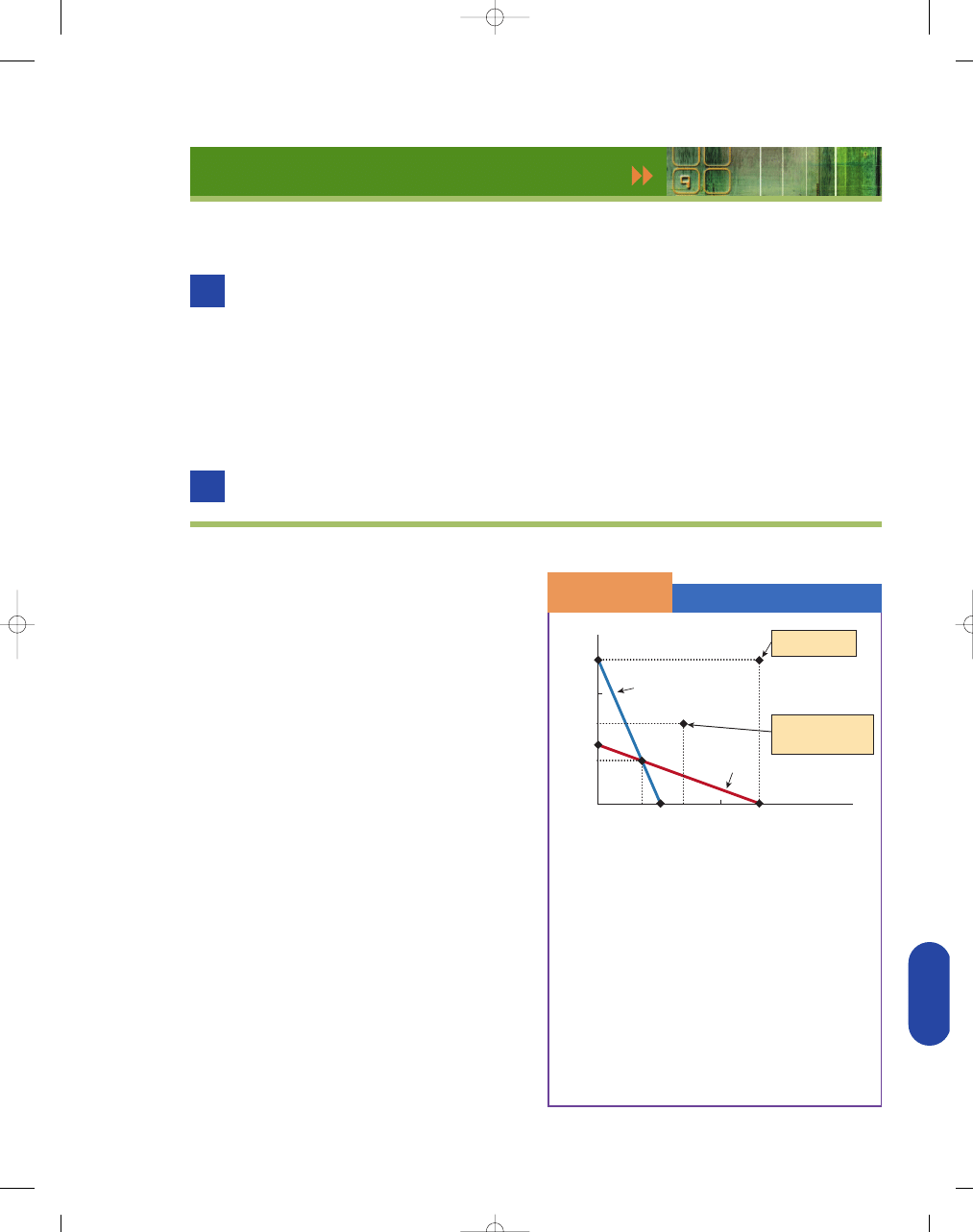

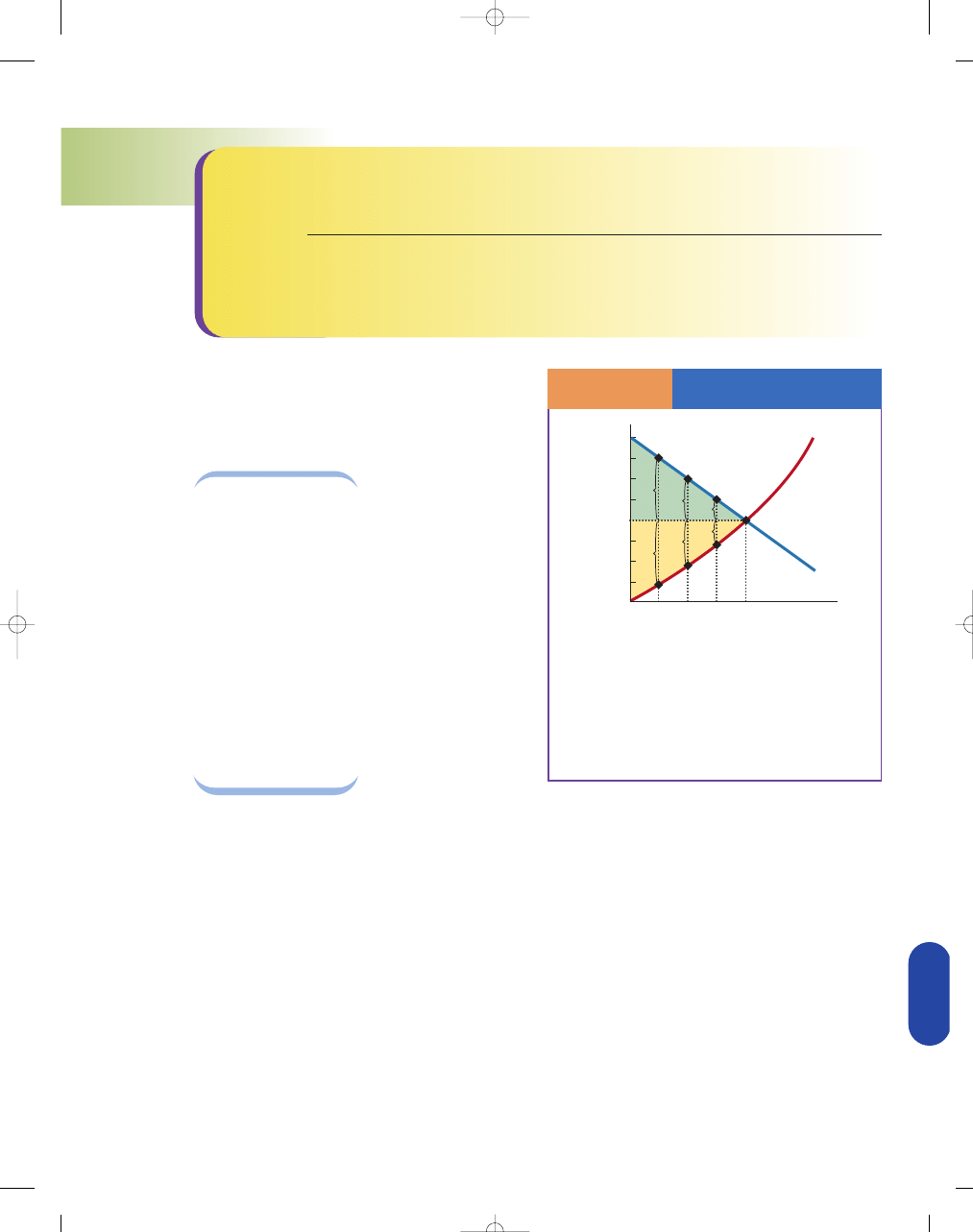

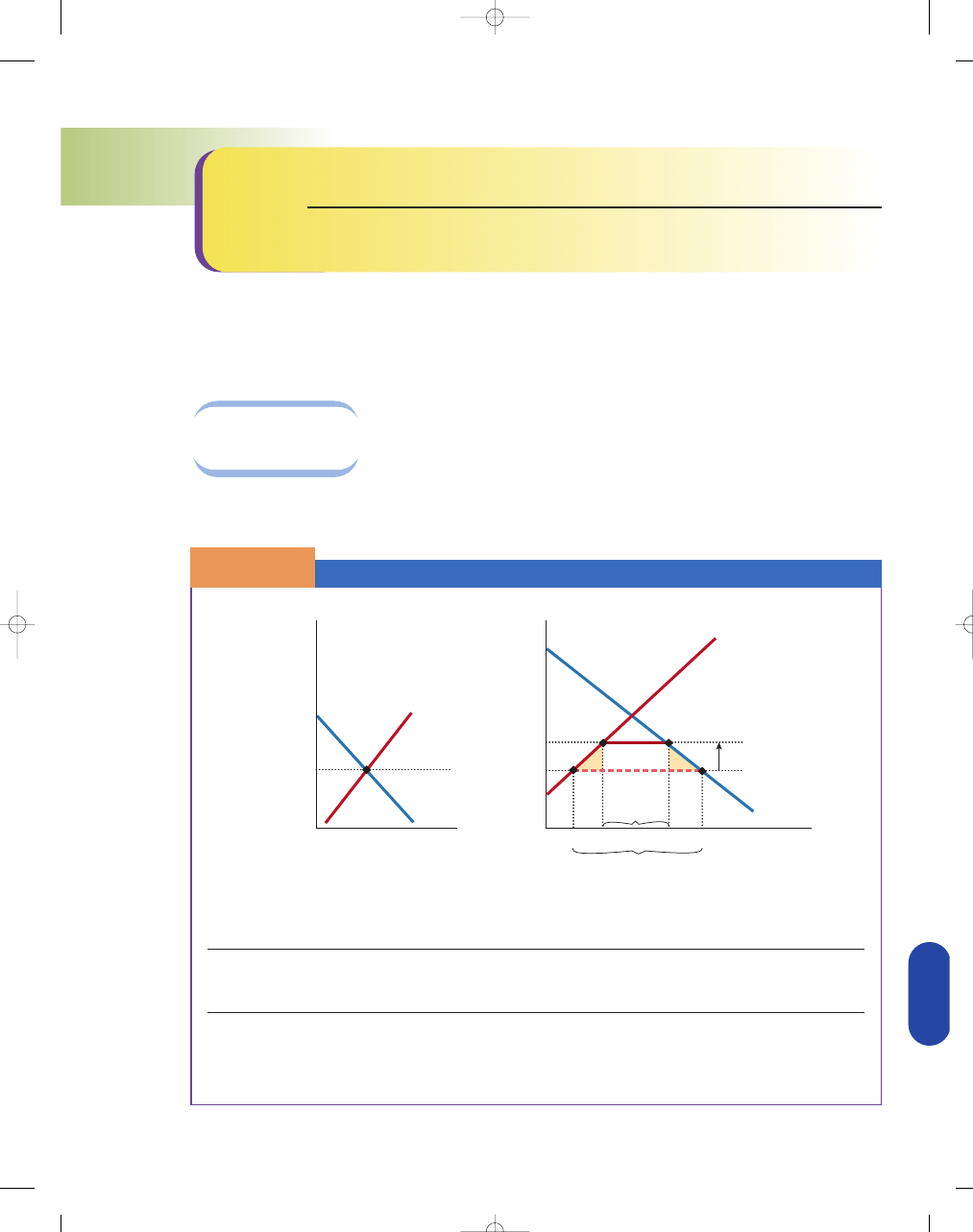

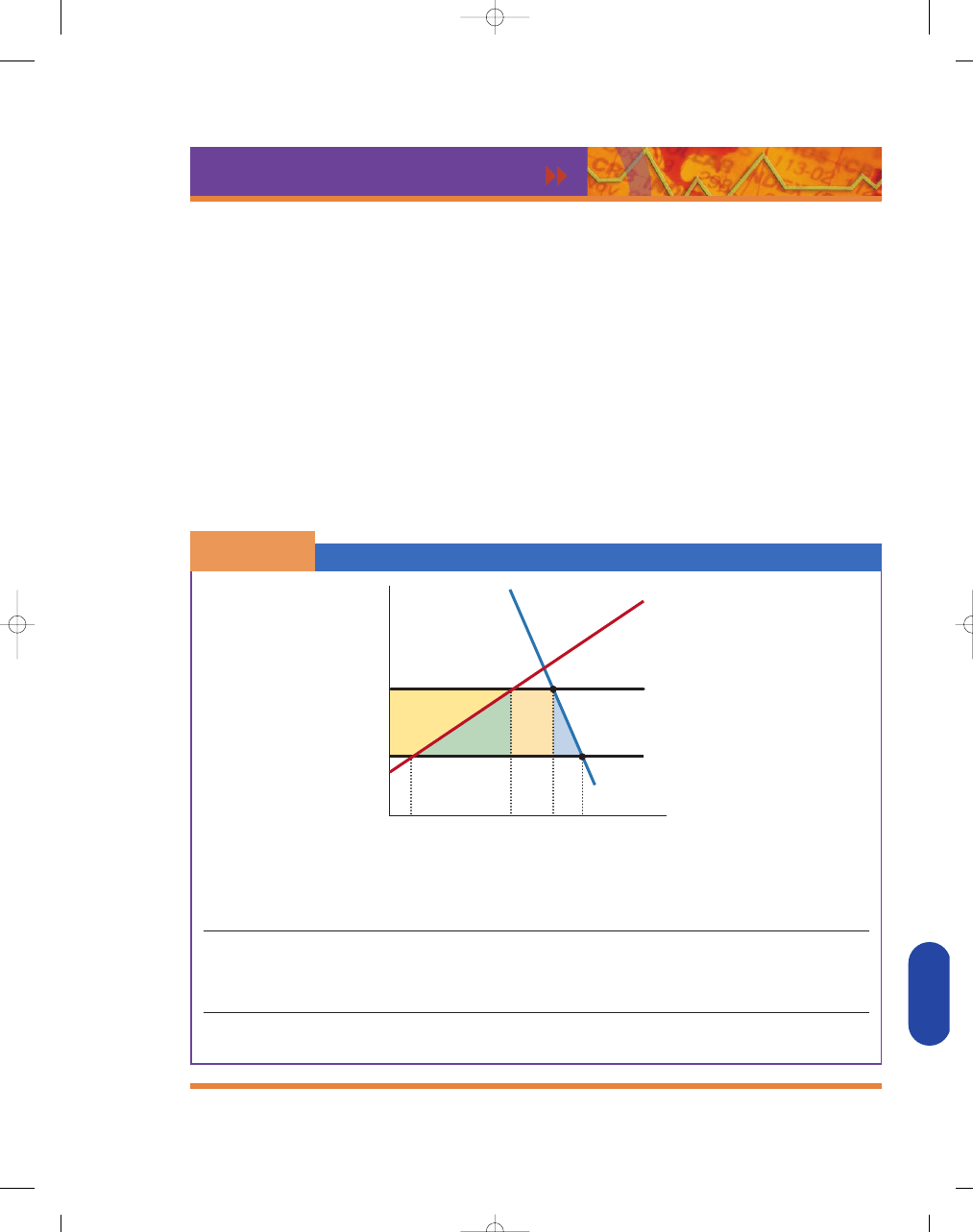

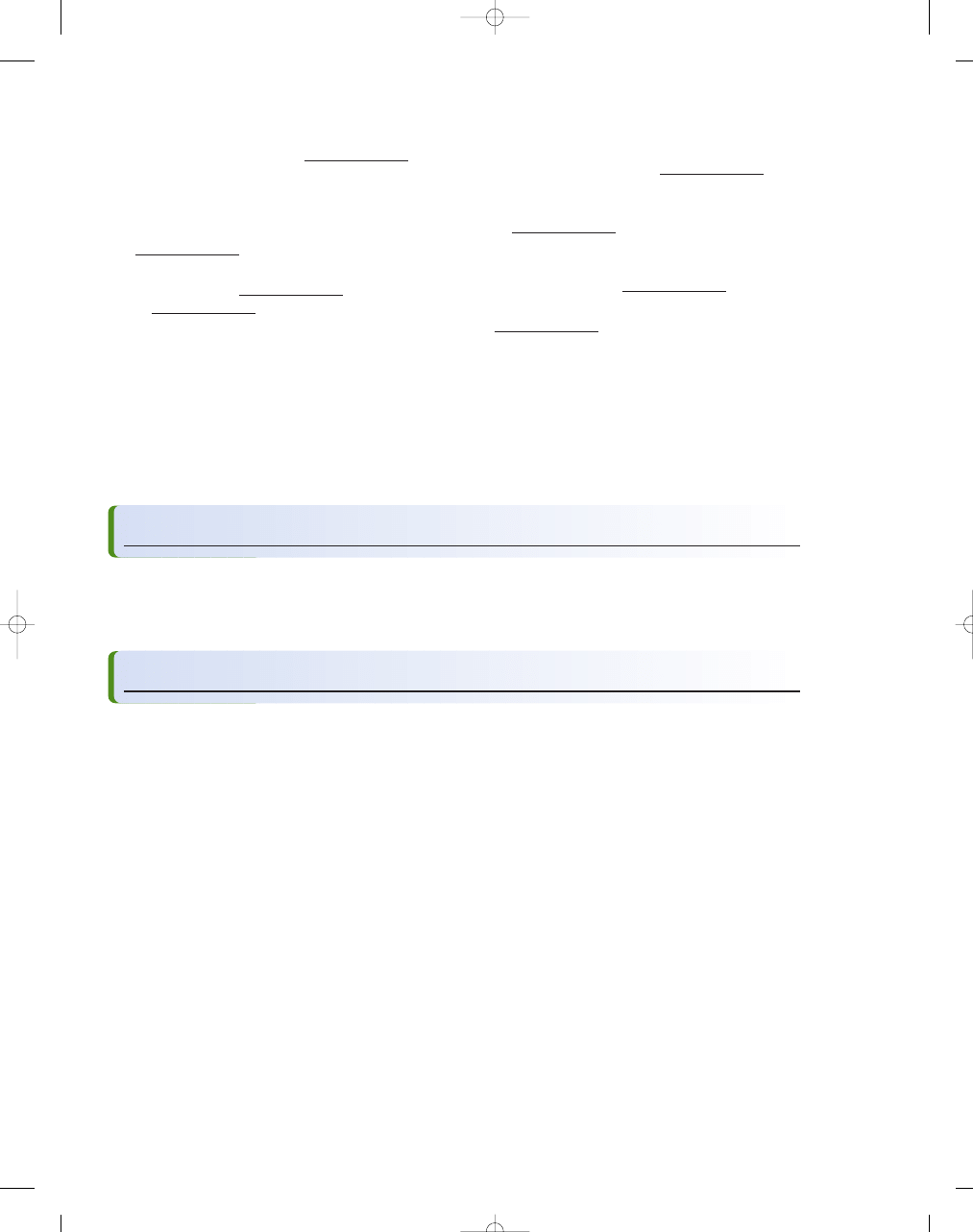

In Exhibit 1, we see the production possibilities

curves for two individuals, Wendy and Calvin. Wendy

and Calvin can produce either food or cloth. We see

that if Wendy devotes all her resources to producing

food, she can produce 30 pounds of food; if she

devotes all her resources to producing cloth, she can

produce 10 yards of cloth. We also see that when

Calvin uses all his resources to produce food, he only

using what you’ve learned

Comparative Advantage

and Absolute Advantage

Renee, a successful artist, can complete one painting in each

40-hour workweek. Each painting sells for $4,000. As a result of her

enormous success, however, Renee is swamped in paperwork. To solve the

problem, Renee hires Drake to handle all the bookkeeping and typing associ-

ated with buying supplies, answering inquiries from prospective buyers and

dealers, writing art galleries, and so forth. Renee pays Drake $300 per week

for his work. After a couple of weeks in this arrangement, Renee realizes that

she can handle Drake’s chores more quickly than Drake does. In fact, she esti-

mates that she is twice as fast as Drake, completing in 20 hours what it takes

Drake 40 hours to complete. Should Renee fire Drake?

Clearly, Renee has an absolute advantage over Drake in both paint-

ing and paperwork, because she can do twice as much paperwork in

40 hours as Drake can and Drake can’t paint well at all. Still, it would be

foolish for Renee to do both jobs. If Renee did her own paperwork, it would

take her 20 hours per week, leaving her only 20 hours to paint. Because each

watercolor takes 40 hours to paint, Renee’s output would fall from one paint-

ing per week to one painting per two weeks.

When Drake works for her, Renee’s net income is $3,700 per week

($4,000 per painting minus $300 in Drake’s wages); when Drake does not

work for her, it is only $2,000 per week (one painting every two weeks).

Even though Renee is both a better painter and better at Drake’s chores

than Drake, it pays for her to specialize in painting, in which she has a

comparative advantage, and allow Drake to do the paperwork. The

opportunity cost to Renee of paperwork is high. For Drake, who lacks

skills as a painter, the opportunity costs of doing the paperwork are

much less.

Q

A

Specialization and Trade

S E C T I O N

3 1 . 2

E

X H I B I T

1

Food (pounds)

Cloth (yards)

0

30

20

15

10

7.5

7.5 10 15

20

30

C

B

A

Wendy's

PPC

Calvin's

PPC

Total production

with specialization

Production per person

after specialization

and trade

Before Trade

Point A—Without specialization, say that Wendy and

Calvin each choose to produce 7.5 pounds of food

and 7.5 yards of cloth.

Specialization and Trade

Point B—Wendy and Calvin’s total production if they

specialize: Wendy produces 30 pounds of food, and

Calvin produces 30 yards of cloth.

Point C—If Wendy and Calvin split equally their

total production after specialization, they will

each have 15 pounds of food and 15 yards

of cloth.

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 903

904

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

produces 10 pounds; but when he uses all his resources

to produce cloth, he can produce 30 yards. In this

example, then, Wendy actually has an absolute advan-

tage in food, while Calvin has an absolute advantage

in cloth. However, as we shall see, it would not affect

the result if Calvin could only produce 2 pounds of

food and 6 yards of cloth.

For simplicity, let’s assume that each producer

operates on a straight-line production possibilities

curve (PPC) and that each initially chooses to divide

her or his productive resources between these products

to produce 7.5 pounds of food and 7.5 yards of

cloth—although any amount of each good within their

respective PPCs could have been produced.

Wendy can produce food at a lower opportunity

cost than Calvin. When Wendy produces 30 pounds

of food, it costs only 10 yards of cloth. However,

when Calvin produces only 10 pounds of food, it

costs 30 yards of cloth. Wendy, then, can produce

food at a lower opportunity cost than Calvin, but

Calvin can produce cloth at a lower opportunity cost

than Wendy. When Calvin produces 30 yards of

cloth, it costs him 10 pounds of food; and when

Wendy produces 10 yards of cloth, it costs 30 pounds

of food. Calvin, then, is the lowest-cost producer

of cloth.

To demonstrate our point about comparative

advantage, we have overlapped the two production

possibility curves in Exhibit 1. At point A, we see that

Wendy produces 7.5 pounds of food and 7.5 yards

of cloth, and Calvin produces 7.5 yards of cloth and

7.5 pounds of food. However, if each specialized and

pursued his or her comparative advantage—the goods

each can produce at the lowest opportunity cost—

then Wendy could produce 30 pounds of food and

Calvin could produce 30 yards of cloth, point B. That

is, by specializing, Wendy and Calvin have produced

30 units of each good rather than 15 units, using the

same amount of total resources. Now if Wendy does

not want all food and Calvin does not want all cloth,

they can trade with each other. In fact, if Wendy

trades half of her food for half of Calvin’s cloth, then

each will have 15 units of food and cloth. This is 7.5

more pounds of food and 7.5 more yards of cloth

than they had before specialization and trade. That is,

if they choose to consume equal amounts of both

products, after specialization and trade, their new

consumption point is at point C—outside their origi-

nal PPCs.

By specializing in products in which they have a

comparative advantage, individuals, regions, and coun-

tries can increase their total production—and it is trade

that allows people to specialize in those activities they

do best. Follow the adage: do what you do best and

trade for the rest.

REGIONAL COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

Using a production possibilities curve, we saw how

Wendy and Calvin could benefit from specialization

and trade. The principle of comparative advantage

can be applied to regional markets as well. In fact,

trade has evolved in large part because different

geographic areas have different resources and there-

fore different production possibilities. The impact of

trade between two areas with differing resources is

shown in Exhibit 2. To keep the analysis simple, sup-

pose two trading areas can produce only two com-

modities, grain and computers. A “trading area” may

be a locality, a region, or even a nation, but for our

example suppose we think in terms of two hypotheti-

cal regions, Grainsville and Techland.

Grainsville and Techland have various potential

combinations of grain and computers that they can

produce. For each region, the cost of producing more

grain is the output of computers that must be forgone,

and vice versa. We see in Exhibit 2 that Techland can

produce more grain (40 bushels) and more comput-

ers (100 units) than Grainsville can (30 bushels and

30 units, respectively), perhaps reflecting superior

Production Possibilities,

Techland and Grainsville

S E C T I O N

3 1 . 2

E

X H I B I T

2

Grain

Computers

Region

(bushels per day)

(units per day)

Techland

0

100

10

75

20

50

30

25

40

0

Grainsville

0

30

6

24

12

18

18

12

24

6

30

0

Before Specialization

Techland

10

75

Grainsville

18

12

Total

28

87

After Specialization

Techland

0

100

Grainsville

30

0

Total

30

100

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 904

C H A P T E R 3 1

International Trade

905

using what you’ve learned

The Secret to Wealth

Do what you do best. Trade for the rest. In other words, specialize and then trade.

The farmer grows wheat, the baker makes bread, the weaver produces

cloth, the tailor sews clothing, the lumberjack harvests wood, the carpenter

builds houses. By exchanging the fruits of their labor in the marketplace, they

all can enjoy more food, clothing and shelter than they could if each tried to

meet his needs in isolation. . . .

It’s a matter of working smarter, not harder.

Societies reaped the benefits of specialization and trade for thousands

of years before English economist David Ricardo (1772–1823) finally demon-

strated why it works. His theory of comparative advantage helps explain why

the United States exports soybeans to China and imports shoes in return.

Suppose an average American worker can produce 100 bushels of soy-

beans or five pairs of shoes and a typical Chinese worker can turn out 8

bushels of soybeans or four pairs of shoes. [See Exhibit 3.]

The United States is more productive than China in both industries, but

consumers in both countries can still gain from specialization and trade.

Shifting a U.S. worker from shoe factory to soybean farm produces a gain of

100 bushels of soybeans at the cost of five pairs of shoes. Shifting two Chinese

workers from farm to factory raises shoe output by eight pairs but cuts soy-

bean production by 16 bushels. The net effect is an increase of 84 bushels of

soybeans and three pairs of shoes.

Total output of both products reaches a maximum when the United

States specializes in soybeans and China in shoes. Through trade, the two

countries can divide the added production between themselves, leaving both

better off than they were on their own.

In the real world, trade isn’t a two-party swap meet. The United States

does business with more than 225 other nations—from Albania to Zimbabwe.

The dizzying number of potential transactions increases the opportunities to

gain from trade.

This potent international division of labor enables America to take advantage

of its expertise in such industries as jet-aircraft manufacturing and financial services

while other countries exploit their edge in oil production or hand assembly.

Specialization and trade arise out of the profit motive. Except when

transaction costs are too high or governments impose barriers, buyers and

sellers will find each other. We’re not meant to go it alone.

SOURCE: W. Michael Cox and Richard Alm “The Secret of Wealth,” 2002 Annual

Report: The Fruits of Free Trade, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The Alchemy of Exchange

S E C T I O N

3 1 . 2

E

X H I B I T

3

Autarky

Free Trade

China

U.S.

China

U.S.

Labor Force

500

100

500

100

Output per worker

Shoes

4

5

4

5

Soybeans

8

100

8

100

Employment

Shoes

125

60

500

0

Soybeans

375

40

0

100

Production

Shoes

500

300

2,000

0

Soybeans

3,000

4,000

0

10,000

Consumption

Shoes

500

300

1,500

500

Soybeans

3,000

4,000

5,000

5,000

Consumption per person

Shoes

1

3

3

5

Soybeans

6

40

10

50

Five hundred Chinese workers can each produce four pairs of shoes or 8 bushels of soybeans. One hundred U.S.

workers can each produce five pairs or 100 bushels—more productive in both jobs but comparatively more so in

farming. Under an autarkic regime—isolated from foreign trade—Chinese workers can afford one pair of shoes

each and 6 bushels of soybeans; Americans, three and 40. Trading freely, China will specialize in shoes and America

in soybeans, raising world production of shoes from 800 to 2,000 pairs and soybeans from 7,000 to 10,000 bushels.

Chinese workers can then afford three pairs of shoes and 10 bushels of soybeans; American workers, five and 50. In

this case, the United States trades 10 bushels of soybeans to China for each pair of shoes.

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 905

906

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

resources (more or better labor, more land, and so on).

These numbers mean that Techland has an absolute

advantage in both products.

Suppose that, before specialization, Techland

chooses to produce 75 computers and 10 bushels of

grain per day. Similarly, suppose Grainsville decides

to produce 12 computers and 18 bushels of grain.

Collectively, then, the two areas are producing 87 com-

puters (75

12) and 28 bushels of grain (10 18) per

day before specialization.

Now, suppose the two nations specialize. Techland

decides to specialize in computers and devotes all its

resources to making that product. As a result, com-

puter output in Techland rises to 100 units per day,

some of which is sold to Grainsville. Grainsville, in

turn, devotes all its resources to grain, producing

30 bushels of grain per day and selling some of it to

Techland. Together, the two areas are producing more

of both grain and computers than before—100

instead of 87 computers and 30 instead of 28 bushels

of grain. Both areas could, as a result, have more of

both products than before they began specializing and

trading.

How can this happen? In Techland, the opportu-

nity cost of producing grain is high—25 computers

must be forgone to get 10 more bushels of grain. The

cost of one bushel of grain, then, is 2.5 computers (25

divided by 10). In Grainsville, by contrast, the oppor-

tunity cost of producing six more units of grain is

six units of computers that must be forgone; so the

cost of one unit of grain is one unit of computers.

In Techland, a unit of grain costs 2.5 computers, while

in Grainsville the same amount of grain costs only

one computer. Grain is more costly in Techland in

terms of the computers forgone than in Grainsville,

so Grainsville has the comparative advantage in the

production of grain, even though Techland has an

absolute advantage in grain.

With respect to computers, an increase in output

by 25 units, say from 25 to 50 units, costs 10 bushels

of grain forgone in Techland. The cost of one more

computer is 0.4 bushel of grain (10 divided by 25). In

Grainsville, an increase in computer output of

six units, say from 12 to 18, is accompanied by a

decrease in grain production by 6 bushels, as

resources are converted from grain to computer man-

ufacturing. The cost of one computer is 1 bushel of

grain. Computers are more costly (in terms of oppor-

tunity cost) in Grainsville and cheaper in Techland,

so Techland should specialize in the production of

computers.

Thus, by specializing in products in which it has

a comparative advantage, an area has the potential of

having more goods and services, assuming it trades

the additional output for other desirable goods and

services that others can produce at a lower opportu-

nity cost. In the scenario presented here, the people in

Techland would specialize in computers, and the

people in Grainsville would specialize in farming

(grain). We can see from this example that specializa-

tion increases both the division of labor and the inter-

dependence among groups of people.

S E C T I O N

*

C H E C K

1.

Voluntary trade occurs because the participants feel that they are better off as a result of

the trade.

2.

A nation, geographic area, or even a person can gain from trade if the good or service is produced

relatively cheaper than anyone else can produce it. That is, an area should specialize in producing

and selling those items that it can produce at a lower opportunity cost than others.

3.

Through trade and specialization in products in which it has a comparative advantage, a country can

enjoy a greater array of goods and services at a lower cost.

1.

Why do people voluntarily choose to specialize and trade?

2.

How could a country have an absolute advantage in producing one good or service without also having a

comparative advantage in its production?

3.

Why do you think the introduction of the railroad reduced self-sufficiency in the United States?

4.

If you can wash the dishes in two-thirds the time it takes your younger sister to wash them, do you have a

comparative advantage in washing dishes with respect to her?

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 906

C H A P T E R 3 1

International Trade

907

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADE: PRODUCER

AND CONSUMER SURPLUS

Recall from Chapter 7 that the difference between the

most a consumer would be willing to pay for a quantity

of a good and what a

consumer actually has to

pay is called

consumer

surplus.

The difference

between the lowest price

for which a supplier

would be willing to

supply a quantity of a

good or service and the

revenues a supplier actu-

ally receives for selling it

is called

producer sur-

plus.

With the tools of

consumer and producer

surplus, we can better

analyze the impact of

trade. Who gains? Who

loses? What happens to

net welfare?

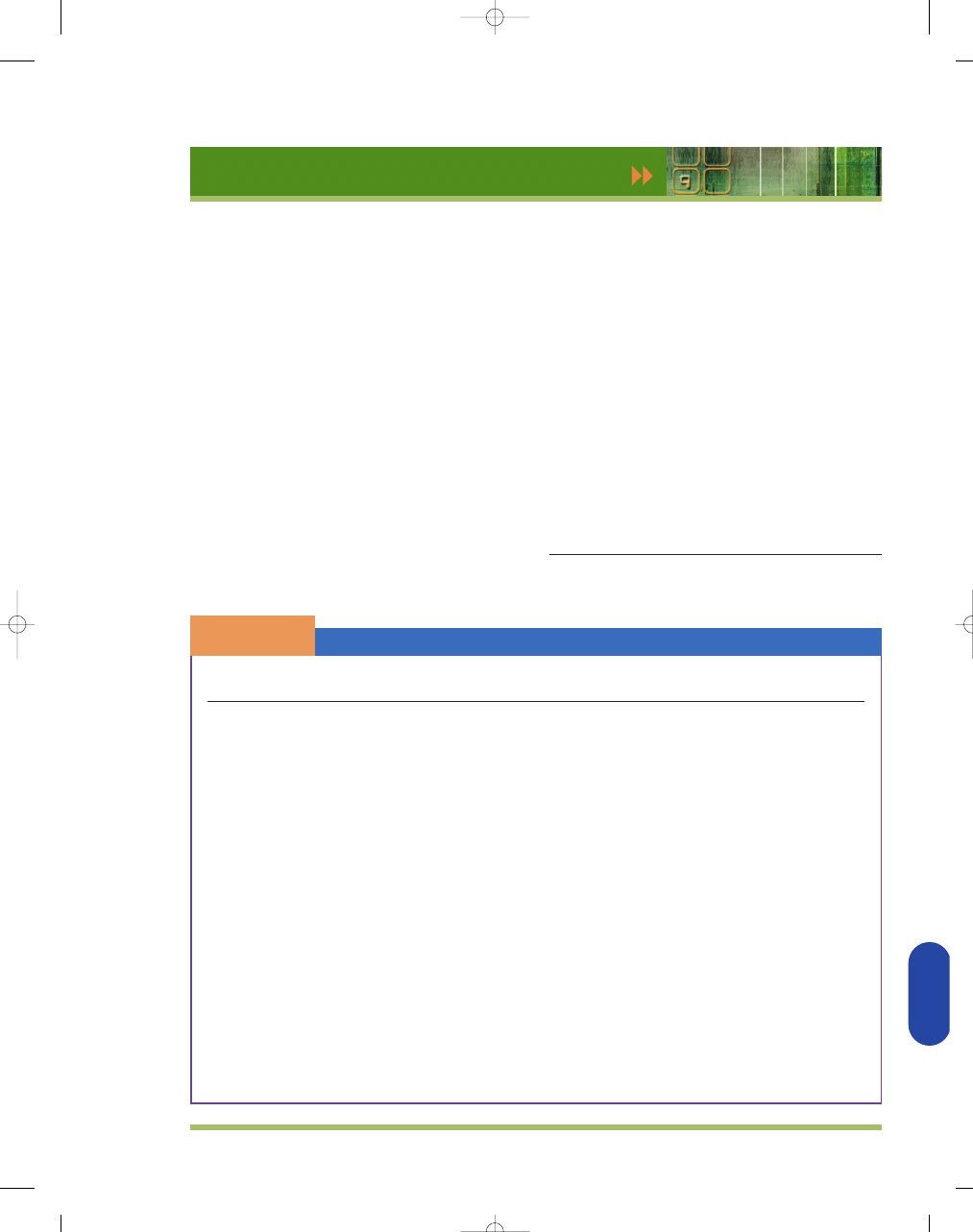

The demand curve represents the maximum prices

that consumers are willing and able to pay for different

quantities of a good or service; the supply curve repre-

sents the minimum prices suppliers require to be will-

ing to supply different quantities of that good or

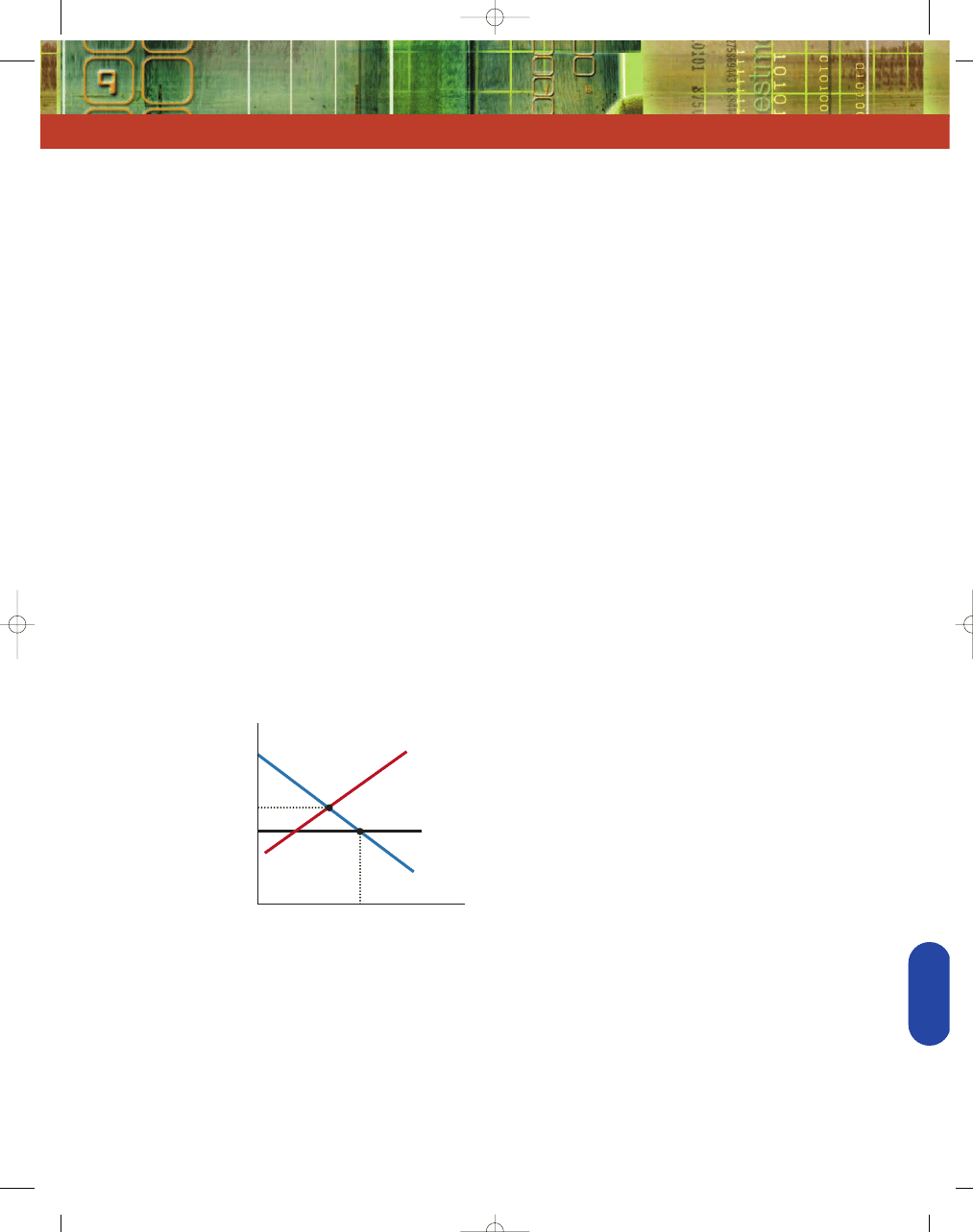

service. For example, in Exhibit 1, the consumer is will-

ing to pay up to $7 for the first unit of output and the

producer would demand at least $1 for producing that

unit. However, the equilibrium price is $4, as indicated

by the intersection of the supply and demand curves. It

is clear that the two would gain from getting together

and trading that unit, because the consumer would

receive $3 of consumer surplus ($7

$4), and the pro-

ducer would receive $3 of producer surplus ($4

$1).

Both would also benefit from trading the second and

third units of output—in fact, from every unit up to the

equilibrium output. Once the equilibrium output is

reached at the equilibrium price, all the mutually

beneficial opportunities from trade between suppliers

and demanders will have taken place; the sum of con-

sumer surplus and producer surplus is maximized.

It is important to recognize that the total gain to the

economy from trade is the sum of the consumer and the

producer surpluses. That is, consumers benefit from

additional amounts of consumer surplus, and producers

benefit from additional amounts of producer surplus.

FREE TRADE AND EXPORTS—DOMESTIC PRODUCERS

GAIN MORE THAN DOMESTIC CONSUMERS LOSE

Using the concepts of consumer and producer sur-

plus, we can graphically show the net benefits of free

trade. Imagine an economy with no trade, where the

S E C T I O N

31.3

S u p p l y a n d D e m a n d i n

I n t e r n a t i o n a l Tr a d e

■

What is consumer surplus?

■

What is producer surplus?

■

Who benefits and who loses when a country

becomes an exporter?

■

Who benefits and who loses when a coun-

try becomes an importer?

consumer surplus

the difference between the price a

consumer is willing and able to pay for

an additional unit of a good and the

price the consumer actually pays; for

the whole market, it is the sum of all

the individual consumer surpluses—

the area below the market demand

curve and above the market price

producer surplus

the difference between what a pro-

ducer is paid for a good and the cost

of producing that unit of the good; for

the market, it is the sum of all the

individual sellers’ producer surpluses—

the area above the market supply

curve and below the market price

Consumer and Product

Surplus

S E C T I O N

3 1 . 3

E

X H I B I T

1

Price

$8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

Quantity

0

S

D

1

2

3

4

CS

PS

CS

PS

CS

PS

Consumer surplus is the difference between what a

consumer has to pay ($4) and what the consumer is will-

ing to pay. For unit 1, consumer surplus is $3 ($7

$4).

Producer surplus is the difference between what a seller

receives for selling a good or service ($4) and the price

at which the seller is willing to supply that good or

service. For unit 1, producer surplus is $3 ($4

$1).

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 907

908

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

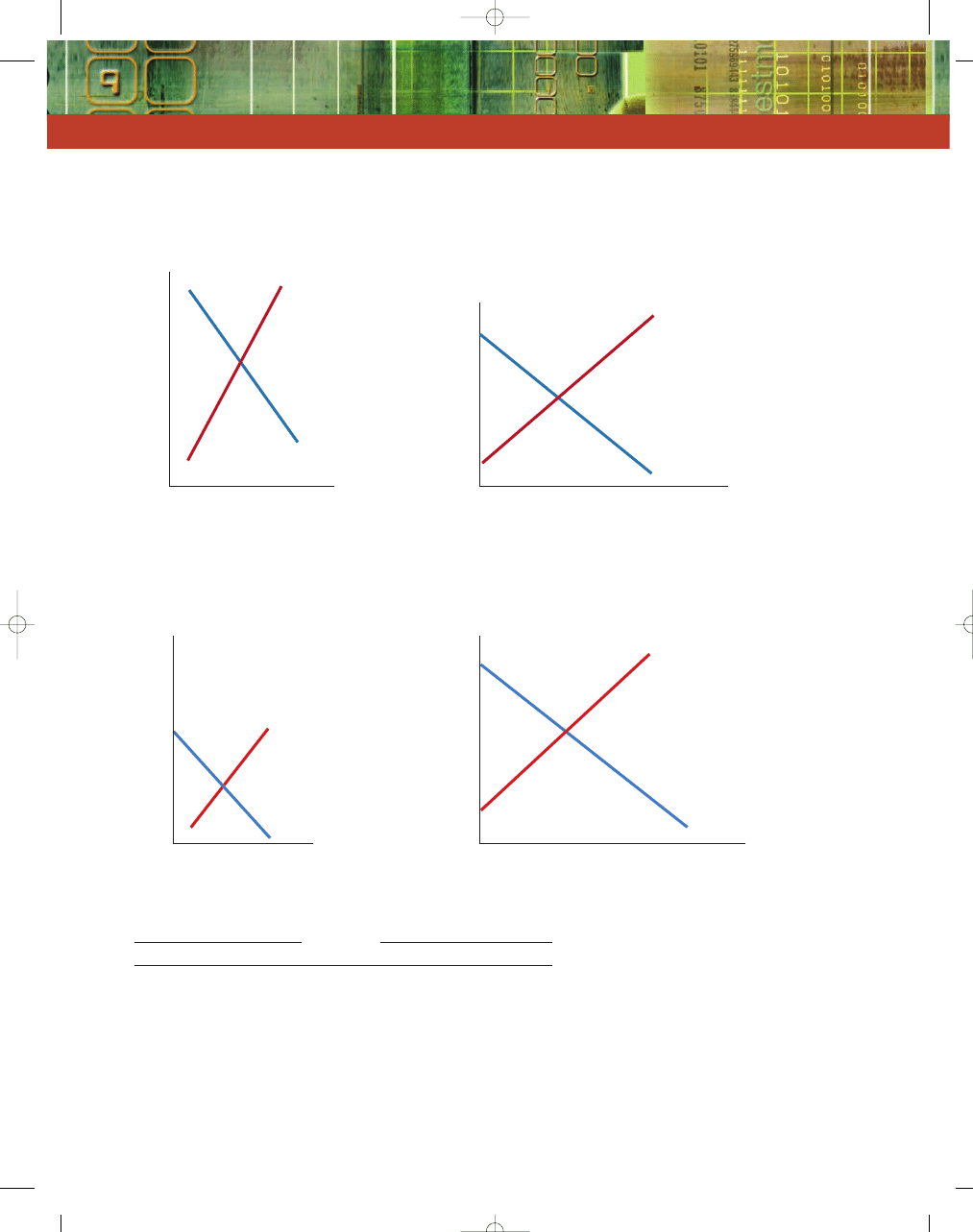

equilibrium price, P

BT

, and equilibrium quantity, Q

BT

,

of wheat are determined exclusively in the domestic

economy, as shown in Exhibit 2. Suppose that this

imaginary economy decides to engage in free trade. You

can see that the world price (established in the world

market for wheat), P

AT

, is higher than the domestic price

before trade, P

BT

. In other words, the domestic econ-

omy has a comparative advantage in wheat, because it

can produce wheat at a lower relative price than the rest

of the world. So this wheat-producing country sells

some wheat to the domestic market and some wheat to

the world market, all at the going world price.

The price after trade (P

AT

) is higher than the price

before trade (P

BT

). Because the world market is huge,

the demand from the rest of the world at the world

price (P

AT

) is assumed to be perfectly elastic. That is,

domestic wheat farmers can sell all the wheat they

want at the world price. If you were a wheat farmer

in Nebraska, would you rather sell all your bushels of

wheat at the higher world price or the lower domes-

tic price? As a wheat farmer, you would surely prefer

the higher world price. But this preference is not good

news for domestic cereal and bread eaters, who now

have to pay more for products made with wheat

because P

AT

is greater than P

BT

.

Graphically, we can see how free trade and

exports affect both domestic consumers and domestic

producers. At the higher world price, P

AT

, domestic

wheat producers are receiving larger amounts of pro-

ducer surplus. Before trade, they received a surplus

equal to area e

f; after trade, they received surplus

b

c d e f, for a net gain of area b c d.

However, part of the domestic producers’ gain comes

at domestic consumers’ expense. Specifically, consumers

had a consumer surplus equal to area a

b c

before the trade (at P

BT

), but they now have only area

a (at P

AT

)—a loss of area b

c.

Area b reflects a redistribution of income,

because producers are gaining exactly what con-

sumers are losing. Is that good or bad? We can’t say

objectively whether consumers or producers are

more deserving. However, the net benefits from

allowing free trade and exports are clearly visible in

area d. Without free trade, no one gets area d. That

is, on net, members of the domestic society gain

when domestic wheat producers are able to sell their

wheat at the higher world price. Although domestic

wheat consumers lose from the free trade, those neg-

ative effects are more than offset by the positive gains

captured by producers. Area d is the net increase in

Free Trade and Exports

S E C T I O N

3 1 . 3

E

X H I B I T

2

World Market

Domestic Market

P

AT

P

BT

Q

BT

Q

S

AT

Q

D

AT

S

DOMESTIC

D

DOMESTIC

Price of

Wheat (domestic)

Price of

Wheat (w

orld)

Quantity of Wheat (domestic)

Exports

a

b

d

e

c

f

World Price

Net domestic gain

from trade

P

WORLD

S

WORLD

D

WORLD

Quantity of Wheat (world)

0

0

Domestic Gains and Losses from Free Trade (exports)

Area

Before Trade

After Trade

Change

Consumer Surplus (CS)

a

b c

a

b c

Producer Surplus (PS)

e

f

b

c d e f

b c d

Total Welfare from Trade (CS

PS)

a

b c e f

a

b c d e f

d

Domestic producers gain more than domestic consumers lose from exports when free trade takes place. On net,

domestic wealth rises by area d.

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 908

C H A P T E R 3 1

International Trade

909

domestic wealth (the welfare gain) from free trade

and exports.

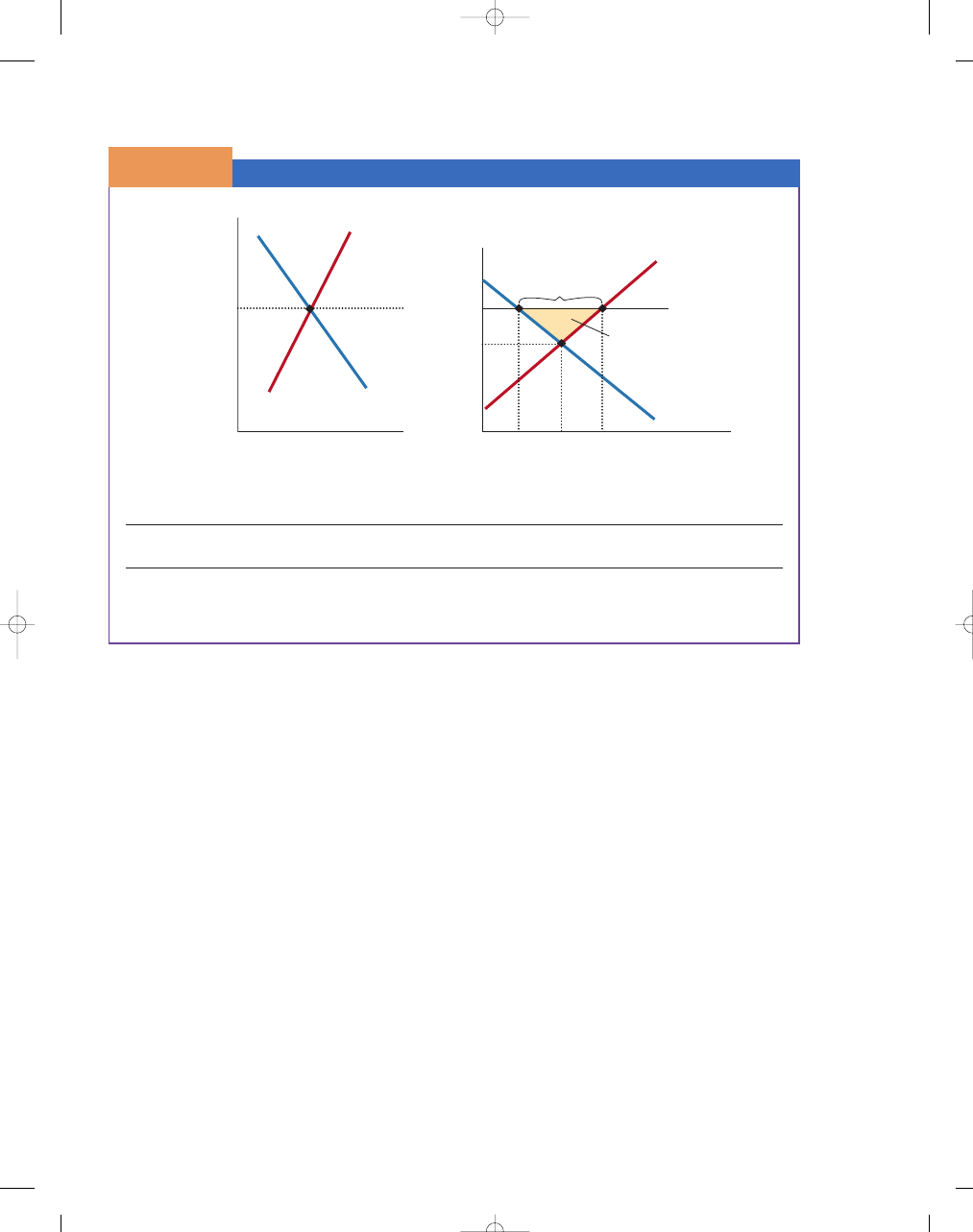

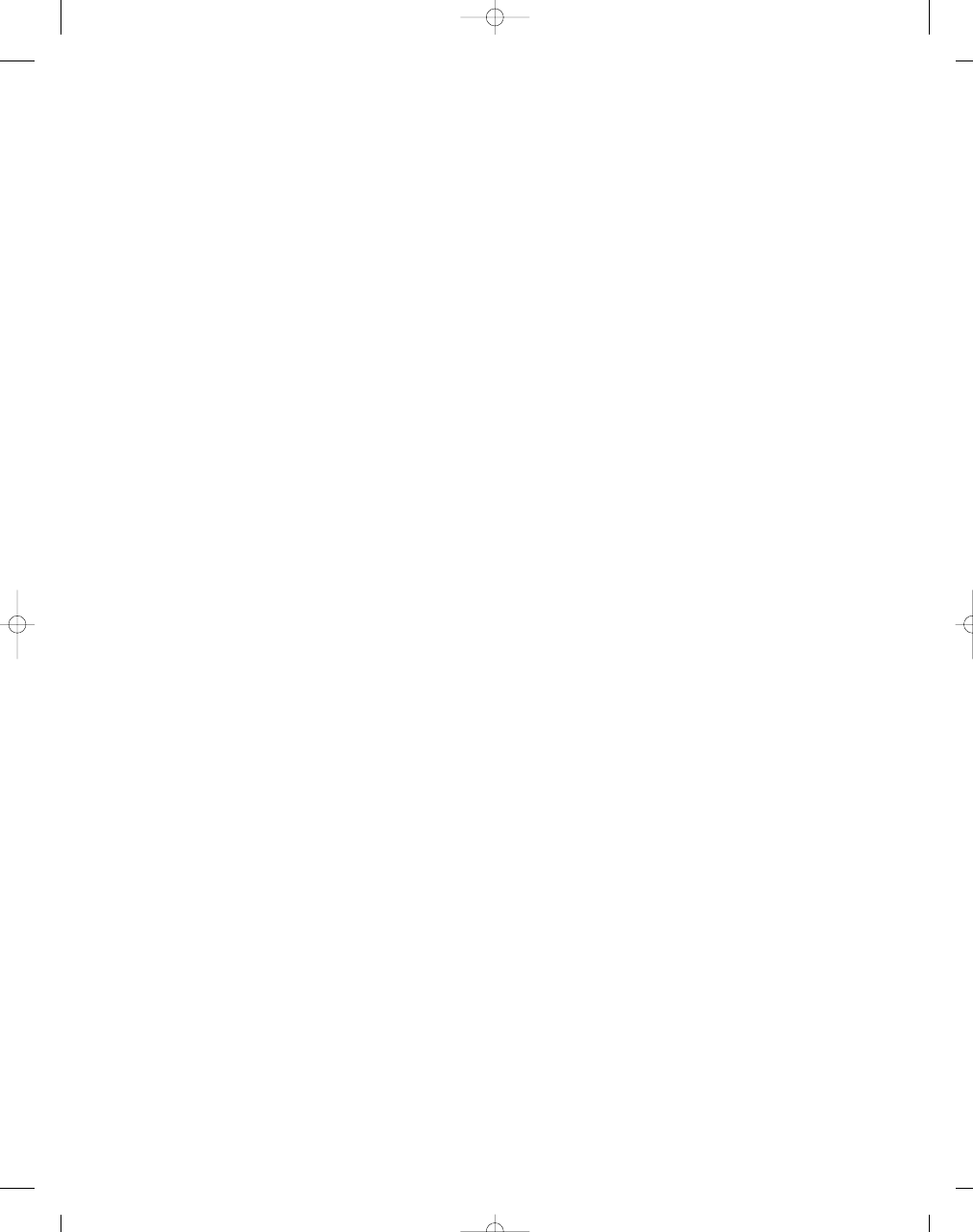

FREE TRADE AND IMPORTS—DOMESTIC

CONSUMERS GAIN MORE THAN DOMESTIC

PRODUCERS LOSE

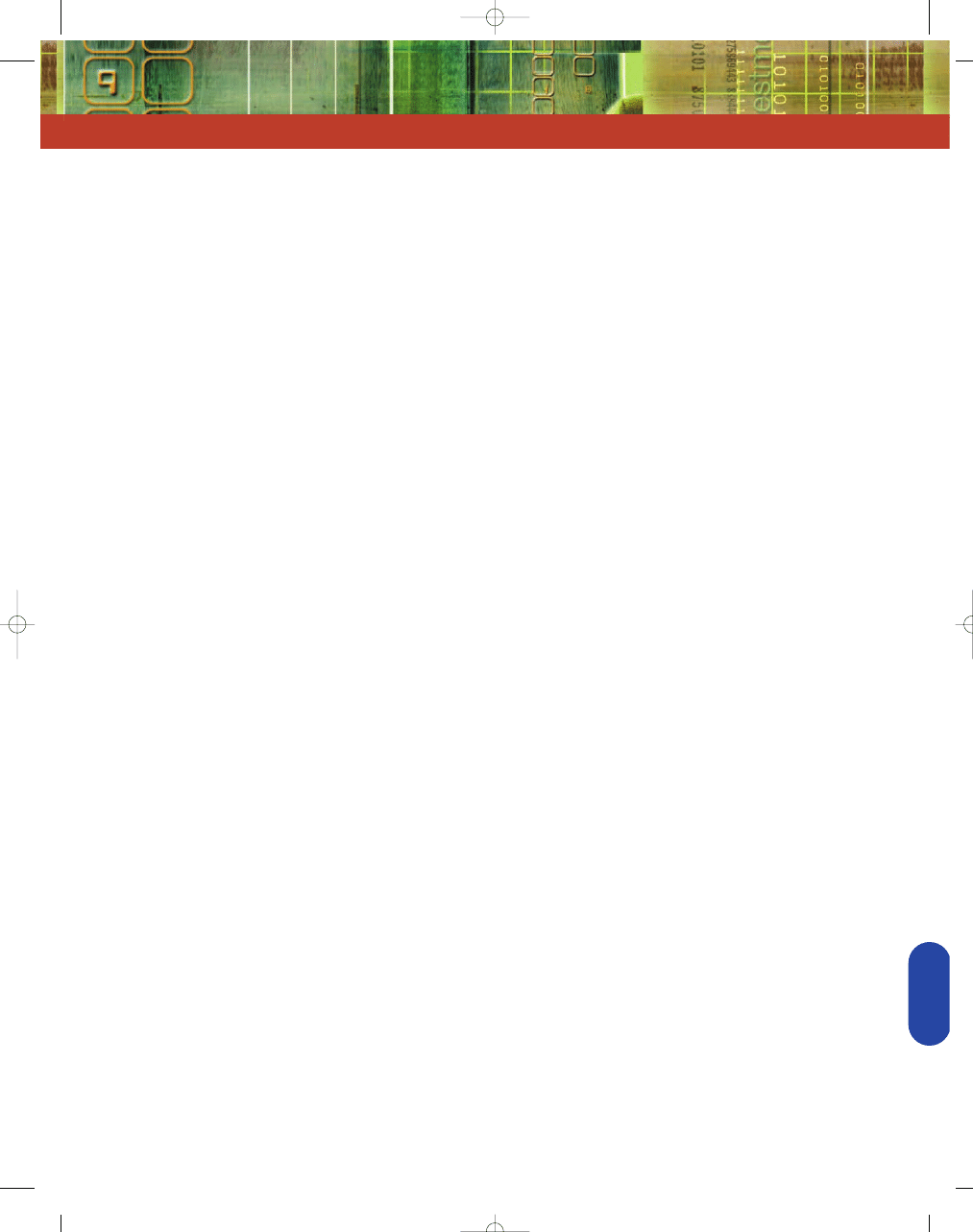

Now suppose that our economy does not produce

shirts as well as other countries of the world. In

other words, other countries have a comparative

advantage in producing shirts, and the domestic

price for shirts is above the world price. This sce-

nario is illustrated in Exhibit 3. At the new, lower

world price, the domestic producer will supply

quantity Q

S

AT

. However, at the lower world price,

the domestic producers will not produce the entire

amount demanded by domestic consumers, Q

D

AT

. At

the world price, reflecting the world supply and

demand for shirts, the difference between what is

domestically supplied and what is domestically

demanded is supplied by imports.

At the world price (established in the world

market for shirts), we assume that the world supply to

the domestic market curve is perfectly elastic—that

the producers of the world can supply all that domestic

consumers are willing to buy at the going price. At the

world price, Q

S

AT

is supplied by domestic producers,

and the difference between Q

D

AT

and Q

S

AT

is imported

from other countries.

Who wins and who loses from free trade and

imports? Domestic consumers benefit from paying a

lower price for shirts. In Exhibit 3, before trade, con-

sumers only received area a in consumer surplus. After

trade, the price fell and quantity purchased increased,

causing the area of consumer surplus to increase from

area a to area a

b d, a gain of b d. Domestic pro-

ducers lose because they are now selling their shirts at

the lower world price, P

AT

. The producer surplus before

trade was b

c. After trade, the producer surplus falls

to area c, reducing producer surplus by area b. Area b,

then, represents a redistribution from producers to con-

sumers; but area d is the net increase in domestic wealth

(the welfare gain) from free trade and imports.

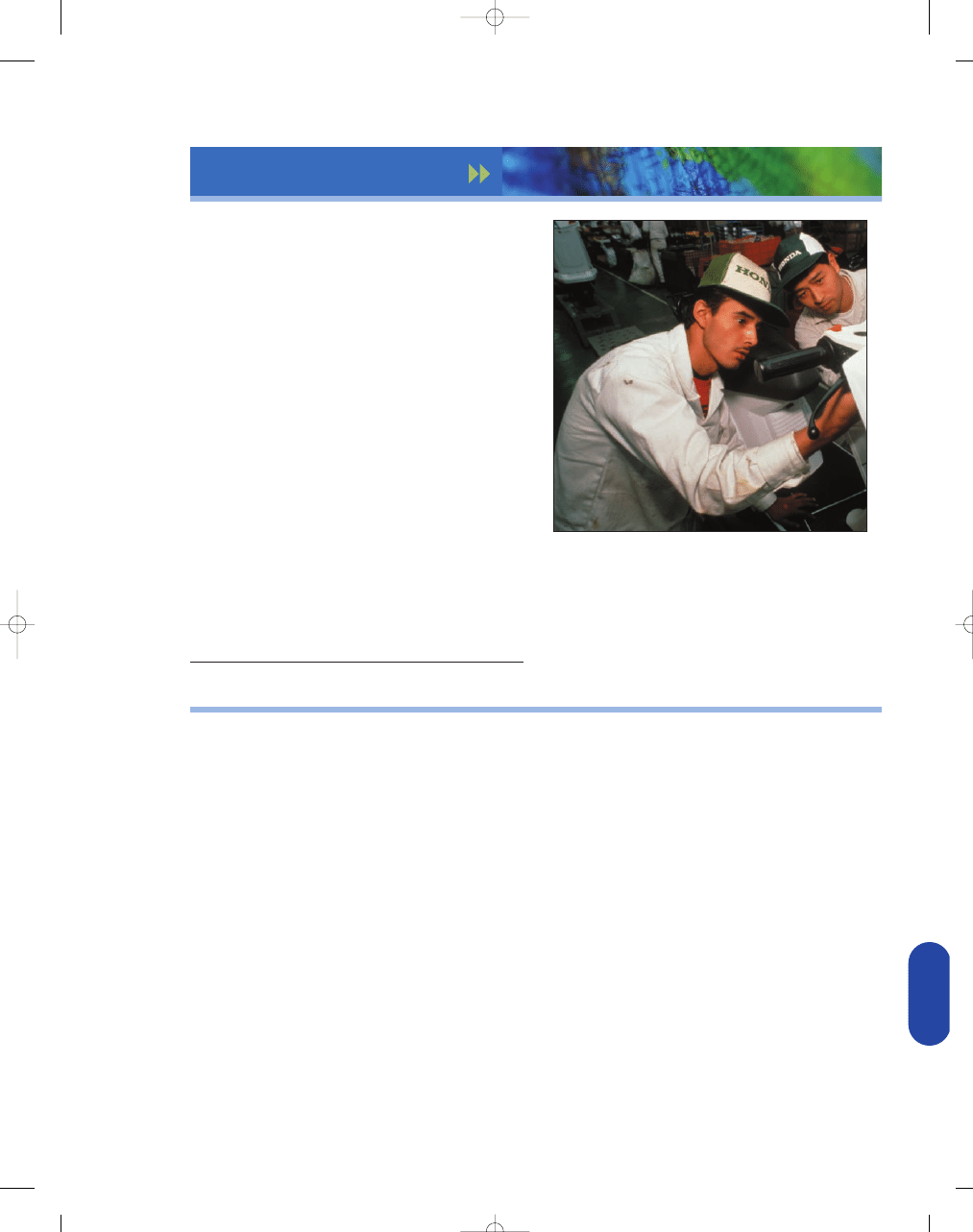

Big Gains for Mexico from Free Trade

The $229 billion worth of trade between the United States and Mexico result-

ing from NAFTA has improved life on both sides of the border.

■

Wages have grown 150 percent for Mexican truck drivers and overall

unemployment has fallen below 2 percent.

■

Recent elections in Mexico installed a new leadership that wants to

improve U.S.–Mexico political and social relations.

■

Mexico has made it possible to extradite drug traffickers to face criminal

charges in the United States.

■

Mexico has pledged to stop publicly defending Cuba’s poor human rights

record.

■

Although Mexican officials have pledged to find solutions to immigration

problems, it is predicted that within 10 years the rising prosperity in

Mexico resulting from free trade will reduce illegal immigration to the

United States anyway.

■

More than 200,000 new jobs have been created in the U.S. economy as a

direct result of NAFTA, surpassing Clinton administration predictions.

■

Americans also benefit from low-priced Mexican goods, such as produce,

computers, and cars.

■

Legislation is under way to allow private investment in electricity produc-

tion—meaning new power plants and potential gains for power-starved

areas of the United States.

SOURCE: Editorial, “Bush Border Crossing Salutes U.S.-Mexican Trade Gains,” USA

Today, 16 February 2001; and National Center for Policy Analysis, http://www.ncpa.org.

g l o b a l w a t c h

©

K

eith Dannemiller/CORBIS Saba

In 1993, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was

passed. This lowered the trade barriers between Mexico, Canada, and

the United States. Proponents of freer trade, especially economists,

viewed the agreement as a way to gain greater wealth through spe-

cialization and trade for all three countries. Opponents thought the

agreement would take away U.S. jobs and lower living standards or,

in the words of former presidential candidate Ross Perot, it would

cause “a giant sucking sound.”

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 909

910

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

Free Trade and Imports

S E C T I O N

3 1 . 3

E

X H I B I T

3

World Market

Domestic Market

P

BT

P

AT

Price of Shir

ts (domestic)

Quantity of Shirts (domestic)

0

a

b

d

c

0

Imports

S

DOMESTIC

D

DOMESTIC

World

Net domestic gain

from trade

Price of Shir

ts (w

orld)

P

WORLD

S

WORLD

D

WORLD

Quantity of Shirts (world)

Q

S

AT

Q

D

AT

Domestic Gains and Losses from Free Trade (imports)

Area

Before Trade

After Trade

Change

Consumer Surplus (CS)

a

a

b d

b

d

Producer Surplus (PS)

b

c

c

b

Total Welfare from Trade (CS

PS)

a

b c

a

b c d

d

Domestic consumers gain more than domestic producers lose from imports when free trade is allowed. On net,

domestic wealth rises by area d.

S E C T I O N

*

C H E C K

1.

The difference between what a consumer is willing and able to pay and what a consumer actually has

to pay is called consumer surplus.

2.

The difference between what a supplier is willing and able to supply and the price a supplier actually

receives for selling a good or service is called producer surplus.

3.

With free trade and exports, domestic producers gain more than domestic consumers lose.

4.

With free trade and imports, domestic consumers gain more than domestic producers lose.

1.

How does voluntary trade generate both consumer and producer surplus?

2.

If the world price of a good is greater than the domestic price prior to trade, why does it imply that

the domestic economy has a comparative advantage in producing that good?

3.

If the world price of a good is less than the domestic price prior to trade, why does it imply that the

domestic economy has a comparative disadvantage in producing that good?

4.

When a country has a comparative advantage in the production of a good, why do domestic producers

gain more than domestic consumers lose from free international trade?

5.

When a country has a comparative disadvantage in a good, why do domestic consumers gain more than

domestic producers lose from free international trade?

6.

Why do U.S. exporters, such as farmers, favor free trade more than U.S. producers of domestic products

who face competition from foreign imports, such as the automobile industry?

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 910

C H A P T E R 3 1

International Trade

911

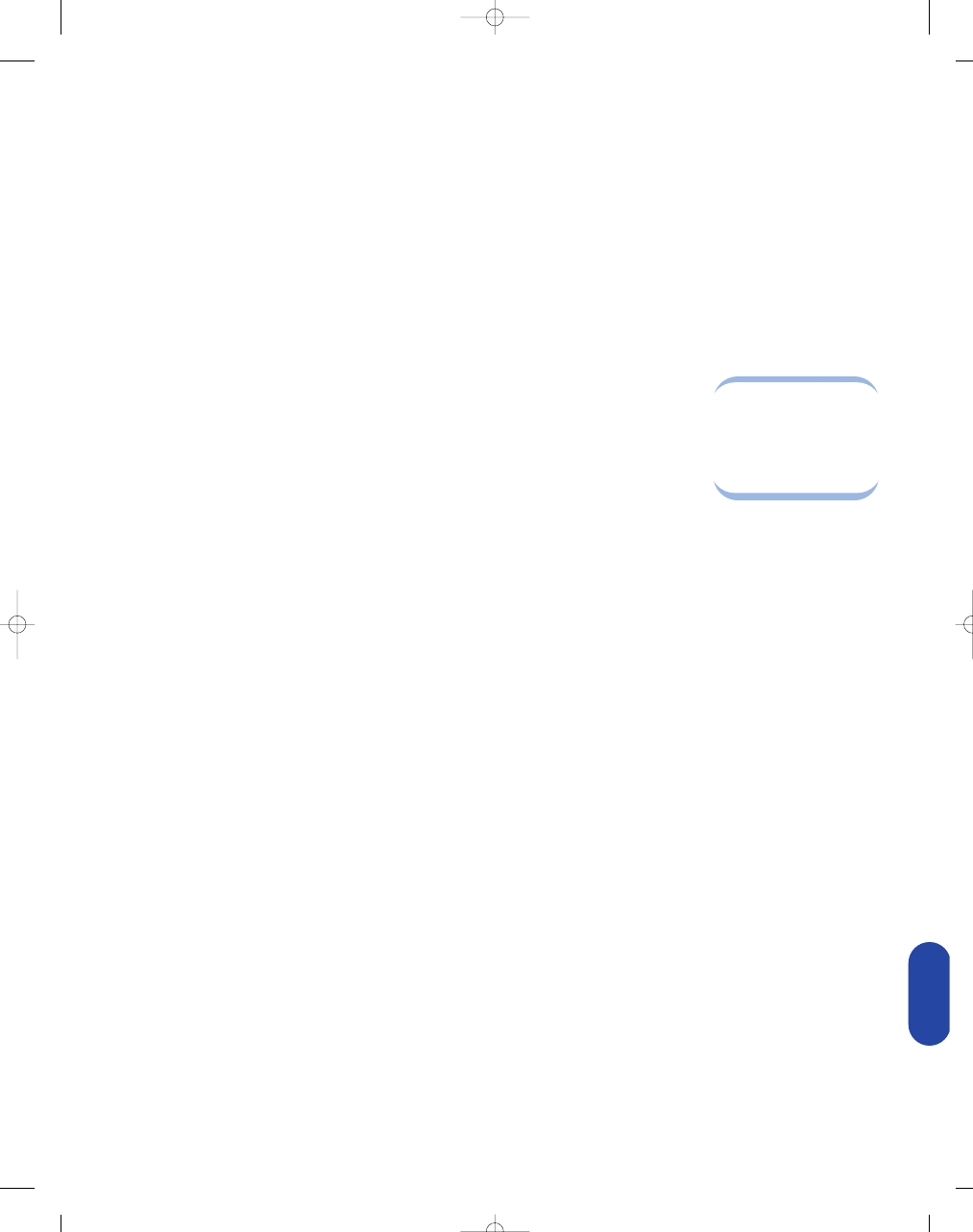

TARIFFS

A

tariff

is a tax on imported goods. Tariffs are usually

relatively small revenue producers that retard the

expansion of trade. They bring about higher prices

and revenues for

domestic producers,

and lower sales and

revenues for foreign

producers. Moreover,

tariffs lead to higher

prices for domestic consumers. In fact, the gains to

producers are more than offset by the losses to con-

sumers. With the aid of a graph we will see how the

gains and losses from tariffs work.

THE DOMESTIC ECONOMIC IMPACT OF TARIFFS

The domestic economic impact of tariffs is presented

in Exhibit 1, which illustrates the supply and demand

curves for domestic consumers and producers of shoes.

S E C T I O N

31.4

Ta r i f f s , I m p o r t Q u o t a s , a n d S u b s i d i e s

■

What is a tariff?

■

What are the effects of a tariff?

■

What are the effects of an import quota?

■

What is the economic impact of subsidies?

tariff

a tax on imports

Free Trade and Tariffs

S E C T I O N

3 1 . 4

E

X H I B I T

1

World Market

Domestic Market

Price of Shoes (w

orld)

Quantity of Shoes (world)

0

0

P

W+T

Q

S

Q

S

Q

D

Q

D

P

W

Price of Shoes (domestic)

Imports before tariff

Quantity of Shoes (domestic)

Imports after

tariff

c

d

e

f

a

b

g

S

DOMESTIC

S

WORLD+TARIFF

S

WORLD

D

WORLD

S

WORLD

P

WORLD

D

DOMESTIC

Gains and Losses from Tariffs

Area

Before Tariffs

After Tariffs

Change

Consumer Surplus (CS)

a

b c d e f

a

b

c d e f

Producer Surplus (PS)

g

c

g

c

Government Revenues (Tariff)

0

e

e

Total Welfare from Tariff

a

b c d e f g

a

b c e g

d f

(CS

PS Tariff Revenues)

In the case of a tariff, we see that consumers lose more than producers and government gain. On net, the dead-

weight loss associated with the new tariff is represented by area d

f.

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 911

912

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

In a typical international supply and demand illus-

tration, the intersection of the world supply and

demand curves would determine the domestic market

price. However, with import tariffs, the domestic

price of shoes is greater than the world price, as in

Exhibit 1. We consider the world supply curve (S

W

)

for domestic consumers to be perfectly elastic; that

is, we can buy all we want at the world price (P

W

).

At the world price, domestic producers are only will-

ing to provide quantity Q

S

, but domestic consumers

are willing to buy quantity Q

D

—more than domestic

producers are willing to supply. Imports make up the

difference.

As you can see in Exhibit 1, the imposition of the

tariff shifts the perfectly elastic supply curve from for-

eigners to domestic consumers upward from S

WORLD

to S

WORLD

TARIFF

, but it does not alter the domestic

supply or demand curve. At the resulting higher

domestic price (P

W

T

), domestic suppliers are willing

to supply more, Q'

S

, but domestic consumers are will-

ing to buy less, Q'

D

. At the new equilibrium, the

domestic price (P

W

T

) is higher and the quantity of

shoes demanded (Q'

D

) is lower. But at the new price,

the domestic quantity demanded is lower and the

quantity supplied domestically is higher, reducing the

quantity of imported shoes. Overall, then, tariffs lead

to (1) a smaller total quantity sold, (2) a higher price

for shoes for domestic consumers, (3) greater sales of

shoes at higher prices for domestic producers, and

(4) lower sales of foreign shoes.

Although domestic producers do gain more sales

and higher earnings, consumers lose much more. The

increase in price from the tariff results in a loss in con-

sumer surplus, as shown in Exhibit 1. After the tariff,

shoe prices rise to P

W

T

, and, consequently, consumer

surplus falls by area c

d e f, representing the

welfare loss to consumers from the tariff. Area c in

Exhibit 1 shows the gain to domestic producers as a

result of the tariff. That is, at the higher price, domes-

tic producers are willing to supply more shoes, repre-

senting a welfare gain to producers resulting from the

tariff. As a result of the tariff revenues, government

gains area e. This is the import tariff—the revenue

government collects from foreign countries on imports.

However, we see from Exhibit 1 that consumers lose

more than producers and government gain from the

tariff. That is, on net, the deadweight loss associated

with the tariff is represented by area d

f.

ARGUMENTS FOR TARIFFS

Despite the preceding arguments against trade restric-

tions, they continue to be levied. Some rationale for

their existence is necessary. Three common arguments

for the use of trade restrictions deserve our critical

examination.

Temporary Trade Restrictions Help

Infant Industries Grow

A country might argue that a protective tariff will

allow a new industry to more quickly reach a scale of

operation at which economies of scale and production

efficiencies can be realized. That is, temporarily

shielding the young industry from competition from

foreign firms will allow the infant industry a chance

to grow. With early protection, these firms will even-

tually be able to compete effectively in the global

market. It is presumed that without this protection,

the industry could never get on its feet. At first hear-

ing, the argument sounds valid, but it involves many

problems. How do you identify “infant industries”

that genuinely have potential economies of scale and

will quickly become efficient with protection? We do

not know the long-run average total cost curves of

industries, a necessary piece of information. Moreover,

if firms and governments are truly convinced of the

advantages of allowing an industry to reach a large

scale, would it not be wise to make massive loans to

the industry, allowing it to begin large-scale produc-

tion all at once rather than slowly and at the expense

of consumers? In other words, the goal of allowing

the industry to reach its efficient size can be reached

without protection. Finally, the history of infant indus-

try tariffs suggests that the tariffs often linger long

after the industry is mature and no longer in need of

protection.

Tariffs Can Reduce Domestic Unemployment

Exhibit 1 shows how tariffs increase output by

domestic producers, thus leading to increased employ-

ment and reduced unemployment in industries where

tariffs have been imposed. Yet the overall employment

effects of a tariff imposition are not likely to be pos-

itive; the argument is incorrect. Why? First, the

imposition of a tariff by the United States on, say,

foreign steel is going to be noticed in the countries

adversely affected by the tariff. If a new tariff on steel

lowers Japanese steel sales to the United States, the

Japanese will likely retaliate by imposing tariffs on

U.S. exports to Japan, say, on machinery exports.

The retaliatory tariff will lower U.S. sales of machin-

ery and thus employment in the U.S. machinery

industries. As a result, the gain in employment in the

steel industry will be offset by a loss of employment

elsewhere.

Even if other countries did not retaliate, U.S.

employment would likely suffer outside the industry

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 912

C H A P T E R 3 1

International Trade

913

gaining tariff protection. The way that other countries

pay for U.S. goods is by getting dollars from sales to

the United States—imports to us. If new tariffs lead to

restrictions on imports, fewer dollars will be flowing

overseas in payment for imports, which means that

foreigners will have fewer dollars available to buy our

exports. Other things being equal, this situation will

tend to reduce our exports, thus creating unemploy-

ment in the export industries.

Tariffs Are Necessary for Reasons

of National Security

Sometimes it is argued that tariffs are a means of pre-

venting a nation from becoming too dependent on

foreign suppliers of goods vital to national security.

That is, by making foreign goods more expensive, we

can protect domestic suppliers. For example, if oil is

vital to operating planes and tanks, a cutoff of foreign

supplies of oil during wartime could cripple a nation’s

defenses.

The national security argument is usually not

valid. If a nation’s own resources are depletable, tariff-

imposed reliance on domestic supplies will hasten

depletion of domestic reserves, making the country

even more dependent on imports in the future. If we

impose a high tariff on foreign oil to protect domestic

producers, we will increase domestic output of oil in

the short run; but in the process, we will deplete the

stockpile of available reserves. Thus, the defense argu-

ment is of questionable validity. From a defense stand-

point, it makes more sense to use foreign oil in

peacetime and perhaps stockpile “insurance” supplies

so that larger domestic supplies would be available

during wars.

Are Tariffs Necessary to Protect

against Dumping?

Dumping occurs when a foreign country sells its prod-

ucts at prices below their costs or below the prices for

which they are sold on the domestic market. For

example, the Japanese government has been accused

for years of subsidizing Japanese steel producers as

they attempt to gain a greater share of the world steel

market and greater market power. That is, the short-

term losses from selling below cost may be offset by

the long-term economic profits from employing this

strategy. Some have argued that tariffs are needed to

protect domestic producers against low-cost dumpers

because they will raise the cost to foreign producers

and offset their cost advantage.

The United States has antidumping laws; if a

foreign country is found guilty of dumping, the United

States can impose antidumping tariffs on that country’s

products, thereby raising the price of the foreign goods

that are being dumped. In practice, however, it is

often difficult to prove dumping; foreign countries

may simply have lower steel production costs. So

what may seem like dumping may in fact be compar-

ative advantage.

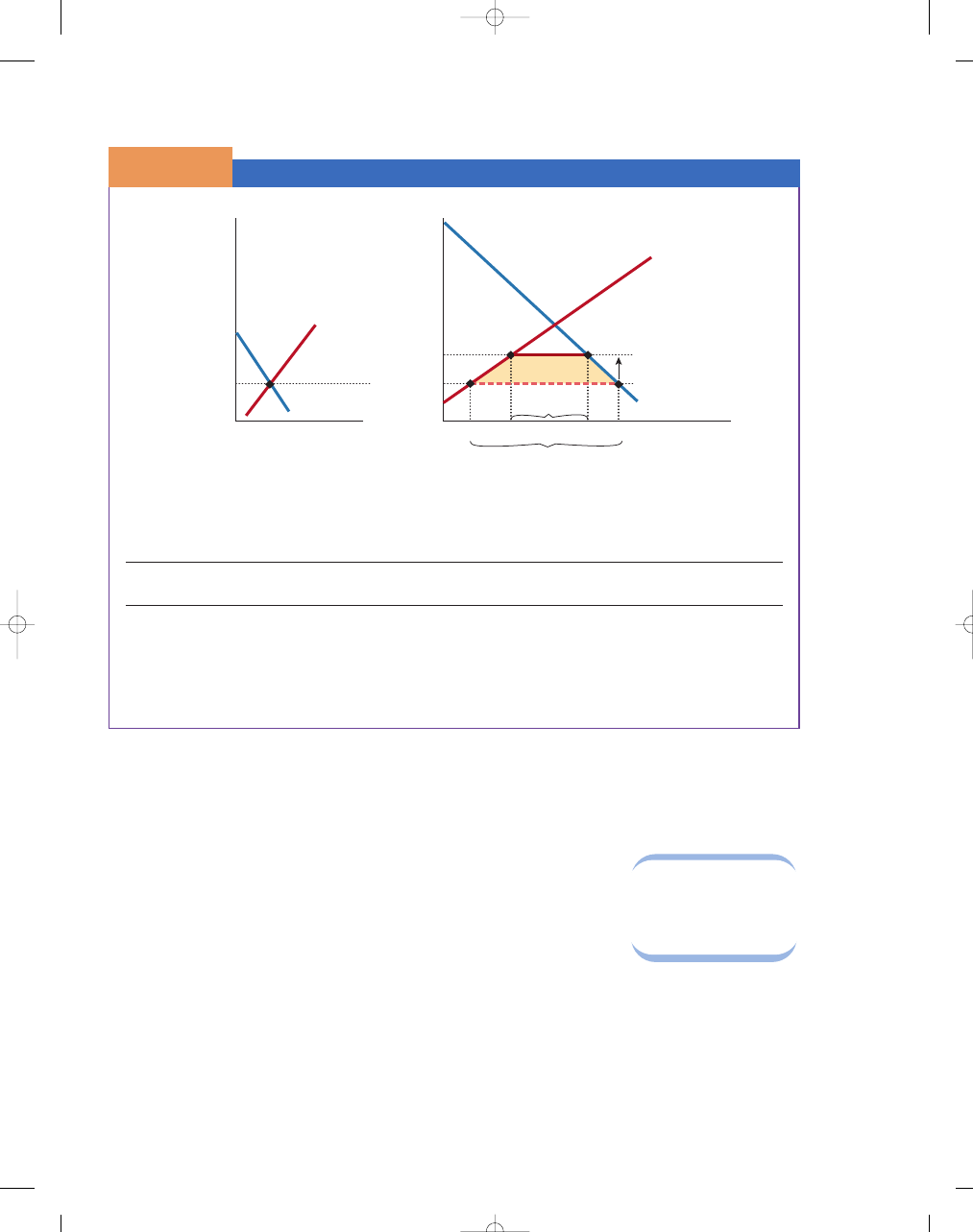

IMPORT QUOTAS

Like tariffs,

import quotas

directly restrict imports,

leading to reductions in trade and thus preventing

nations from fully real-

izing their comparative

advantage. The case for

quotas is probably even

weaker than the case

for tariffs. Unlike what

occurs with a tariff, the

U.S. government does

not collect any revenue

as a result of the import quota. Despite the higher

prices, the loss in consumer surplus, and the loss in

government revenue, quotas come about because

people often view them as being less protectionist

than tariffs—the traditional, most-maligned form of

protection.

Besides the rather blunt means of curtailing

imports by using tariffs and quotas, nations have

devised still other, more subtle means of restricting

international trade. For example, nations sometimes

impose product standards, ostensibly to protect con-

sumers against inferior merchandise. Effectively, how-

ever, those standards may be simply a means of

restricting foreign competition. For example, France

might keep certain kinds of wine out of the country

on the grounds that they are made with allegedly infe-

rior grapes or have an inappropriate alcoholic con-

tent. Likewise, the United States might prohibit

automobile imports that do not meet certain stan-

dards in terms of pollutants, safety, and gasoline

mileage. Even if these standards are not intended to

restrict foreign competition, the regulations may

nonetheless have that impact, restricting consumer

choice in the process.

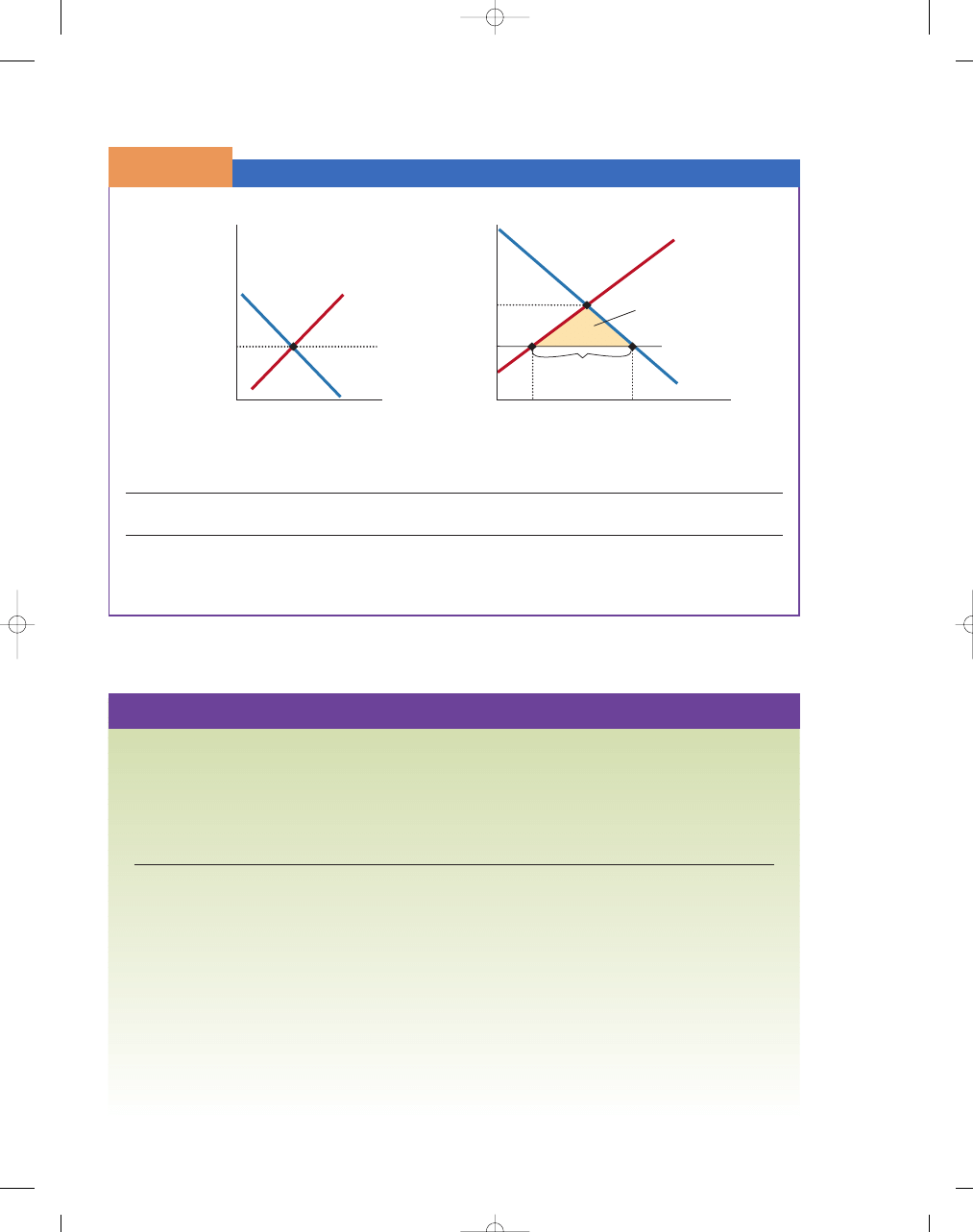

THE DOMESTIC ECONOMIC IMPACT

OF AN IMPORT QUOTA

The domestic economic impact of an import quota on

autos is presented in Exhibit 2. The introduction of an

import quota increases the price from the world price,

P

W

(established in the world market for autos) to P

W

Q

.

The quota causes the price to rise above the world

import quota

a legal limit on the imported

quantity of a good that is produced

abroad and can be sold in domestic

markets

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 913

914

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

price. The domestic quantity demanded falls and the

domestic quantity supplied rises. Consequently, the

number of imports is much smaller than it would

be without the import quota. Compared with free

trade, domestic producers are better off but domestic

consumers are worse off. Specifically, the import

quota results in a gain in producer surplus of area c and

a loss in consumer surplus of area c

d e f.

However, unlike the tariff case, where the government

gains area e in revenues, the government does not

gain any revenues with a quota. Consequently, the

deadweight loss is even greater with quotas than with

tariffs. That is, on net, the deadweight loss associated

with the quota is represented by area d

e f. Recall

that the deadweight loss was only d

f for tariffs.

If tariffs and import quotas hurt importing

countries, why do they exist? The reason they exist

is that producers can make large profits or “rents”

from tariffs and import quotas. Economists call these

efforts to gain profits from government protection

rent seeking.

Because this money, time, and effort

spent on lobbying could

have been spent pro-

ducing something else,

the deadweight loss

from tariffs and quotas

will likely understate

the true deadweight

loss to society.

THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF SUBSIDIES

Working in the opposite direction, governments

sometimes try to encourage exports by subsidizing

producers. With a subsidy, revenue is given to

Free Trade and Import Quotas

S E C T I O N

3 1 . 4

E

X H I B I T

2

World Market

Domestic Market

P

W+Q

S

WORLD

D

WORLD

P

WORLD

Q

S

Q

S

Q

D

Q

D

P

W

Price of A

utos (domestic)

Price of A

utos (w

orld)

Imports before quota

Quantity of Autos

(world)

Quantity of Autos

(domestic)

0

0

Imports after

quota

a

b

c

d

f

e

g

S

DOMESTIC

S

WORLD

QUOTA

S

WORLD

D

DOMESTIC

Gains and Losses from Import Quotas

Area

Before Quota

After Quota

Change

Consumer Surplus (CS)

a

b c d e f

a

b

c d e f

Producer Surplus (PS)

g

c

g

c

Total Welfare (CS

PS)

a

b c d e f g

a

b c g

d e f

from Quota

With an import quota, the price rises from P

W

to P

W

Q

. Compared with free trade, consumers lose area c

d e f,

while producers gain area b. The deadweight loss from the quota is area d

e f. Under quotas, consumers lose

and producers gain. The difference in deadweight loss between quotas and tariffs is area d, which the government

is not able to pick up with import quotas.

rent seeking

efforts by producers to gain profits

from government protections such

as tariffs and import quotas

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:43 AM Page 914

C H A P T E R 3 1

International Trade

915

p o l i c y a p p l i c a t i o n

The Sugar Quota

The world price of sugar is much lower than the U.S. price. For example, in

recent years, the U.S. price of sugar has been as high as 25 cents per pound

while the world price was less than a nickel per pound. Why? The reason is

that a sugar import quota protects the domestic sugar industry, by con-

trolling how much foreign sugar can enter the country. This policy raised

the price of U.S. sugar and helps both domestic producers and those for-

eign producers who have lobbied successfully for quota allotment. In 2006,

five of the largest producing Caribbean nations received increases in their

quota because of the devastation done to the sugar plantations in

Louisiana by Hurricane Katrina.

The sugar quota impacts the price of everything from beverages to birth-

day cakes. As we can see graphically in Exhibit 3, this policy may be good for

domestic sugar producers but it is clearly bad for consumers (and those

producers who use sugar as an input to further production such as candy

makers, several of whom have moved out of the United States). Even

though the numbers are hypothetical for ease of quantifying, they are

close enough to reality that you can see the monetary impact of the

quota.

Notice the cost to consumers of this policy is area a

+ b + c + d, or

$2.1 billion a year. But, part of what consumers lose, producers gain. U.S.

producers gain area a, or $850 million, and foreign producers with quota

allotments for the U.S. market received $600 million (remember they

would have had to sell their sugar for $0.10, instead of $0.20, on the

world market). Areas b and d represent the deadweight loss from this

policy—$65 billion.

The Sugar Quota

S E C T I O N

3 1 . 4

E

X H I B I T

3

0

3

14

20

22

Demand

Domestic

Supply

Domestic

U.S. Price (with quota)

World Price

a

b

c

d

0.08

0.10

$0.20

Quantity of Sugar

(billions of pounds)

Price

(dollars per Pound)

E

2

E

1

Q

S

Q

′

S

Q

′

D

Q

D

Gains and Losses Associated with Sugar Quota

Loss of Consumer Surplus

Area a

b c d $2.1 billion

Gain to U.S. Producers of Sugar

Area a

$850 million

Gain to Foreign Sugar Producers with Quota Allotments

Area c

$600 million

Deadweight Loss

Area b

d $650 million

Area a

$850 million ($0.10 11 billion 0.5) ($0.10 3 billion) Area c $600 million ($0.10 6 billion)

Area b

$550 million ($0.10 11 billion 0.5)

Area d

$100 million ($0.10 2 billion 0.5)

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:44 AM Page 915

916

M O D U L E 8

International Trade and Finance

i n t h e n e w s

Do What You Do Best, Outsource the Rest?

International trade generates higher overall output by redirecting jobs to

those who create the most added values—that is, to those who maximize their

productive abilities. Put simply, the benefits of free trade can be summarized

as: “Do what you do best. Trade for the rest.” But times are changing, and so

are many traded commodities.

The newest U.S. trade commodity is skilled white-collar work, with an

estimated 60 percent of these outsourced jobs going to India. As with most

traded commodities, outsourcing work abroad is the product of lower foreign

labor costs and potentially higher future profits. And like free trade, out-

sourcing has become controversial.

Outsourcing’s critics see only the elimination of work previously done in

the United States and view outsourcing as exporting white-collar jobs to

other countries. What they fail to recognize is that attempting to protect

these jobs would mean higher prices for consumers and the unrealized poten-

tial for more productive jobs in new industries.

What is outsourcing? Why is India the leading country in attracting out-

sourced work? And what are the economic and political implications as firms

do what they do best and outsource the rest?

OUTSOURCING: WHAT IT IS AND WHY IT IS DONE

Outsourcing occurs when an organization transfers some of its tasks to an out-

side supplier. In many recent cases, businesses in India have served as suppliers.

A variety of jobs are being outsourced, including routine office work,

computer-related work, business (accounting and finance), architecture, legal,

art and design, and sales (Chart 1 ). The availability of real-time information

via the Internet, satellite and transoceanic communications allows businesses

to be sustained instantaneously around the globe. New information tech-

nologies let fewer people do more work and also help quickly bring new skills

to learners everywhere.

Specialized tasks—such as software development, financial research and

call centers—can often be accomplished elsewhere in the world at a fraction

of U.S. costs. Through outsourcing, it is not uncommon for companies to real-

ize net cost savings of 30 to 50 percent (Chart 2 ). As a result, it is often in a

firm’s best interest to outsource certain tasks and use the abilities of its

remaining workers in other, more productive activities.

WHY INDIA?

Many countries offer low production and labor costs. But to make outsourc-

ing viable, other business-promoting factors must be considered as well, such

as the number and quality of skilled workers, maturity of the outsource

market, government support, the legal system, political stability, location and

accessibility, education, infrastructure, time differentials, technological

modernity and English language skills.

For myriad services, India has emerged as the most appealing country in

many of these areas. India has the second-largest English-speaking population

in the world (after the United States) and an educated technical workforce

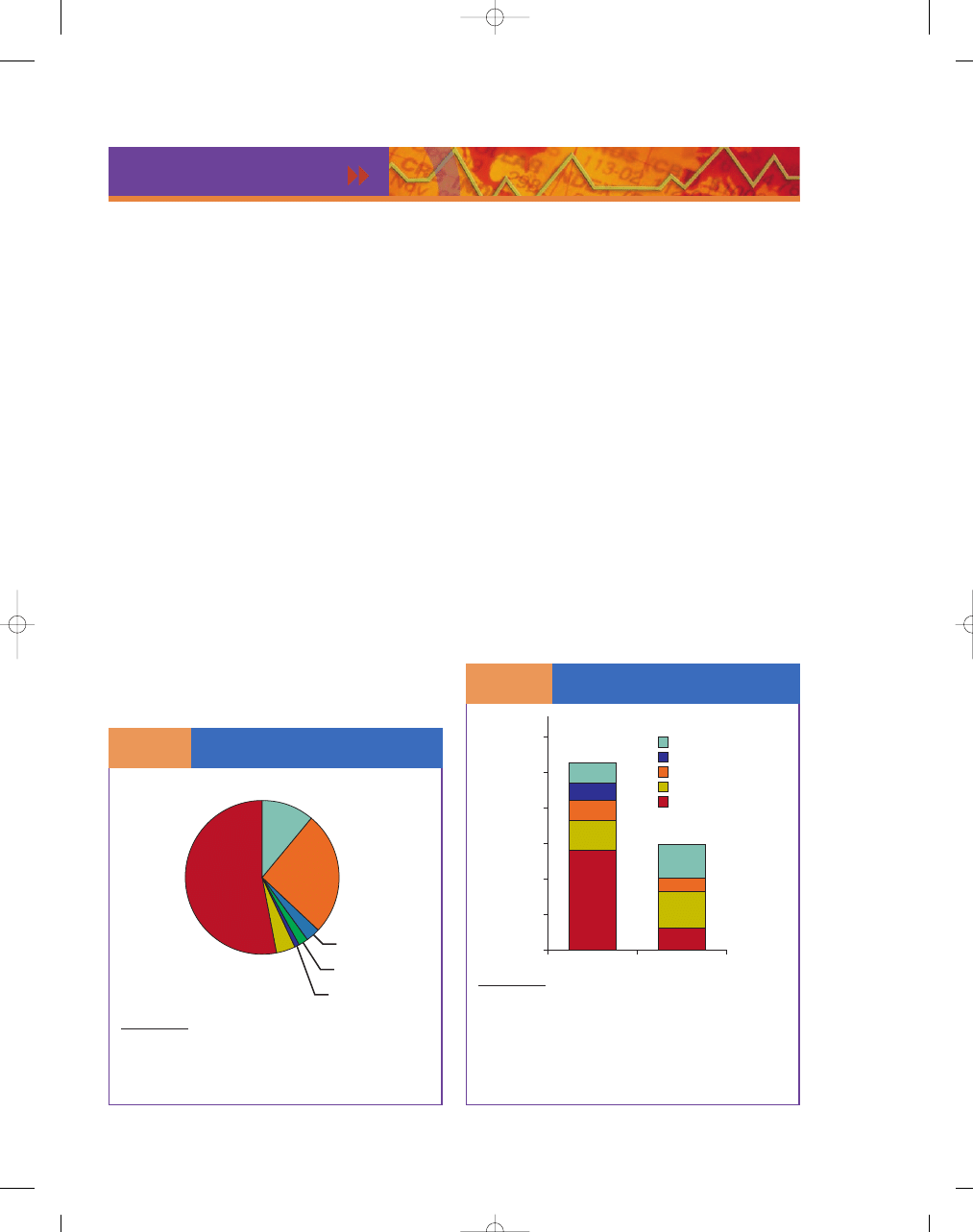

A Variety of Jobs

Being Outsourced

C

H A RT

1

Computer

26%

Business

11%

Office

53%

Architecture

3%

Legal

2%

Art, design

1%

Sales

4%

NOTE: Percentages computed on estimates for 2000.

SOURCE: John C. McCarthy (2002), “3.3 Million U.S. Services Jobs

to Go Offshore,” TechStrategy Research Brief, Forrester Research

Inc., November 11.

Outsourcing to India

Can Net Large Savings

C

H A RT

2

Profit

Tax*

Overhead

Telecom/Network

Wages

0

United States

India

1

2

3

4

5

6

U

.S.

dollar

s (in millions)

*India exempts taxes for exports, including call centers for

foreign businesses.

NOTE: This comparison is based on annual costs for a 100-seat call

center.

SOURCE: Antonio Riera, Janmejaya Sinha, and Alpesh Shah (2002),

“Passage to India: The Rewards of Remote Business Processing,”

The Boston Consulting Group.

(continued)

95469_31_Ch31-p897-930.qxd 5/1/07 10:44 AM Page 916

C H A P T E R 3 1

International Trade

917

i n t h e n e w s ( c o n t . )

pool of more than 4.1 million workers. In addition, the outsourcing market in

India—especially for information technology (IT) services—has had time to

mature and gain support from U.S. businesses.

India’s 1991 Statement on Industrial Policy facilitated foreign direct

investment and technology transfers, ushering in a new era with fewer of

the regulatory burdens that had previously kept foreign firms from estab-

lishing business operations there. In the decade since this policy reform,

foreign direct investment in India has increased more than fiftyfold. And

even though India’s basic infrastructure is among the worst in the world,

businesses in India have found ways to compete globally in the IT arena,

making India one of the world’s leaders in software exports. The city of

Bangalore—home to many IT outsourcing firms and U.S. corporations—

contributed $2.5 billion last year to India’s total software exports of

$9.5 billion.

Furthermore, promoting IT is one of the Indian government’s top priori-

ties. The Ministry of Information Technology was established in October 1999

to accelerate the implementation of IT projects in government, education and

the private sector. India has many universities dedicated to maintaining state-

of-the-art IT curriculums, and more than 70,000 software engineers graduate

annually from Indian institutes.

OUTSOURCING’S IMPLICATIONS

As long as there are workers in India (or elsewhere) willing and able to

perform the same work for less pay, U.S. firms will increasingly examine

outsourcing as an option to hold the line on costs and remain globally

competitive. Forrester Research estimates that the number of out-

sourced jobs will increase to nearly 600,000 by 2005 and to 3.3 million

by 2015, including jobs requiring management and life science skills. This

is unwelcome news to U.S. workers whose jobs will be lost. But history

suggests that this phenomenon will also generate many better, higher-

paying jobs at home as long as the United States can keep its competi-

tive advantage in innovation. Entrepreneurship and innovation depend

on a broadly educated workforce committed to continuous learning and

risk-taking.

Even though these are anxious times for U.S. workers, consumers are

sure to benefit from outsourcing. In 1776, Adam Smith emphasized that

“it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker,

that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”

1

Following Smith’s ideas, modern companies participate in the international

1

Adam Smith, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of

Nations (1776), reprint, ed. Edwin Cannan (New York: Modern Library), 1937,

p. 14.

market and pursue their own interests by making the most productive

use of their resources. By pursuing profit maximization, firms remain

competitive.

For U.S. consumers, competition leads to more and better economic

choices. And the desire to meet consumer demand is the reason for all

productive activity. Competition sustained through outsourcing has posi-

tively affected the well-being of consumers and producers. By participat-

ing in international trade, we increase our ability to consume the goods

and services we value most, and we can do so at lower cost. If firms did

not pursue outsourcing, or if governments placed barriers or limits on

outsourcing in an attempt to “help” American workers, there would be

less motivation to produce (because of lower profit potential) and higher

prices for consumers.

International competition is often blamed for job losses and

depressed sales. But protecting lost jobs is always harmful to consumers.

Even so, several states are contemplating legislation that would prohibit

their state government from contracting with foreign firms to perform

services. Such actions cost taxpayers more by taking away opportunities

for significant savings.

THINK GLOBALLY, ACT GLOBALLY

With specialization comes trade. Work once sheltered from faraway competi-

tion is no longer secure. Innovations that create economic growth simultane-

ously destroy specific jobs as new technologies replace older ones. The fact is,

the Internet creates jobs and the Internet destroys jobs.

Businesses in India and elsewhere are developing an important com-

petitive advantage in outsourcing by providing quality services at low costs.