BEHAVIOR (HOWARD S. KIRSHNER, SECTION EDITOR)

Transient Global Amnesia: A Brief Review and Update

Howard S. Kirshner

Published online: 7 September 2011

# Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011

Abstract Transient global amnesia (TGA) is a transitory

syndrome of memory loss, lasting less than 24 h. Although

there are many known causes of transient amnesia, the

syndrome of TGA remains of unknown etiology. Known

causes of transient amnesia, theories of pathogenesis of

TGA, and recommended evaluation and treatment are

discussed.

Keywords Transient global amnesia . Transient amnesia .

Amnesia . Transient ischemic attack . TIA . Memory loss

Introduction

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is a syndrome of tempo-

rary memory loss, or amnesia. Although earlier descriptions

of transitory memory loss have been cited, especially that

of Benon in 1909 [

], the modern syndrome of TGA was

first described in medical literature in 1956 by Bender [

],

and in the same year by Guyotat and Courjon [

]. Fisher

and Adams [

] gave the syndrome its current name and

described its key features in a 1958 abstract, and in an

extended manuscript with 17 detailed case descriptions in

1964 [

]. Since then, there have been many reports of cases

and series of TGA, and many theories of pathogenesis, yet

to date the precise cause remains unknown.

TGA typically occurs in an elderly or middle-aged

patient, lasts from 1 to 24 h, and then resolves

spontaneously and completely. Precipitating events such

as cold temperature, sexual intercourse, and compromis-

ing situations (e.g., an elderly man in the midst of an

extramarital affair, or bathing in the cold waters of the

North Atlantic) have been reported in some cases. The

key features of the syndrome involve an abrupt onset of

anterograde amnesia, or inability to form new memories,

and retrograde amnesia, a loss of recall of memories for

a variable period of time prior to the onset of symptoms.

During the episode, the patient maintains personal

knowledge, usually knowledge of family members,

preserved remote memories and intellect. Some patients

are disoriented, not knowing the exact time, or place.

They typically ask repetitive questions about where they

are and why they are there. The companion answers

these questions, but the patient then asks them over

again, forgetting the answers. As the patient

’s anterog-

rade memory recovers, at a time less than 24 h, the

period of retrograde amnesia

“shrinks.” After recovery, a

permanent gap in memory remains, equal to the sum of

the brief period of retrograde amnesia before the event,

plus the period of anterograde amnesia after onset.

Hodges and Warlow [

] provided seven diagnostic

criteria for TGA: 1) attacks must be witnessed by a

capable observer; 2) there must be anterograde amnesia

during the attack; 3) clouding of consciousness and loss of

personal identity must be absent, and no other neuro-

behavioral deficits such as aphasia or apraxia can be

present; 4) there should be no other focal neurologic signs

present during or after the attack; 5) evidence of epileptic

seizures must be absent; 6) the attacks must resolve within

24 h; and 7) patients with recent head injury or an active

seizure disorder (or another cause of amnesia) are

excluded.

H. S. Kirshner (

*)

Department of Neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center,

Nashville, TN 37232, USA

e-mail: howard.kirshner@vanderbilt.edu

Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep (2011) 11:578

–582

DOI 10.1007/s11910-011-0224-9

TGA is common in clinical practice. Miller et al. [

reported an overall incidence in Rochester, Minnesota of

about 5 cases per 100,000 of population, although in

patients above the age of 50 years the incidence was more

than 20 per 100,000. Others have estimated an incidence

of about 30 cases/100,000 of population/year [

Recurrent episodes occur in only a minority of cases,

roughly 15% to 30% [

–

]; Miller et al. [

] reported a

recurrence rate of 23.8%.

Identification of TGA requires the exclusion of other

causes of amnesia. The etiologies of transient amnesia are

numerous. All of these syndromes of transient amnesia

have in common a temporary disruption of the memory

system secondary to either generalized brain dysfunction or

focal disruption of the Papez

’s circuit, a pathway in each

hemisphere with connections from the hippocampus, to the

mammillary body, to the dorsomedial thalamus, to the

cingulate gyrus, and then back to the hippocampus. Papez

’s

circuit is also called the

“medial temporal-diencephalic

memory circuit

” [

••]. Head trauma or concussion is a

common cause of transient amnesia [

]. Epileptic

seizures, especially of the complex partial type involving

the medial temporal structures, frequently disrupt memory

[

–

]. If the seizure itself is not witnessed, the patient

may present with the clinical problem of an unexplained

episode of amnesia. Usually recurrent seizure episodes

make the diagnosis clear. Electroconvulsive therapy produ-

ces temporary amnesia by a similar mechanism. Transient

ischemia of the posterior cerebral artery territory can

produce a temporary amnesia [

]. Gorelick et al. [

reported a patient with three episodes of amnesia, the first

two transient, and the third persistent. The patient then had

an infarction in the left thalamus. Bogousslavsky and Regli

[

] also reported four cases of TGA associated with

strokes, two in the medial temporal lobe, one in the left

lentiform nucleus, and one in the left thalamus. Cases of

transient amnesia during coronary arteriography may result

from either unilateral or bilateral ischemia of the hippo-

campal complex [

].

Transient amnestic states in patients with migraine,

usually followed by severe headache, also likely reflect an

ischemic mechanism [

–

], although cortical spreading

depression has also been cited as a possible mechanism

[

]. The syndrome of confusional migraine in children

resembles TGA [

]. Drug intoxications, especially those

with benzodiazepines [

,

], are among the more

common causes of transient amnesia, presumably by

temporarily depressing the activity of the memory system.

Of course, physicians use this property of benzodiazepines

deliberately in pre-anesthesia with midazolam (Versed®;

Roche Laboratories, Basel, Switzerland) before esophago-

gastroscopies and similar procedures. Three neuroscientists

reported their own transient amnesia following airplane

travel in which they took triazolam (Halcion®; Pfizer, New

York, NY) for sleep and also consumed alcoholic beverages

[

]. Another more contemporary cause of transient

amnesia is the hypnotic zolpidem (Ambien®; Sanofi-

Aventis, Bridgewater, NJ) [

“Alcoholic blackouts”

have a similar mechanism [

]. Inebriated individuals may

appear awake and engage in activities for which they have

no recollection the following day. Occasionally, transient

amnesia occurs in patients with pituitary or brain tumors,

perhaps on the basis of seizures [

]. Finally, transient

amnesia can be of psychogenic cause, as in hysterical

fugue states.

Once the known causes of transient amnesia are

excluded, most cases of the idiopathic syndrome of

TGA remain of unknown etiology. Fisher and Adams

[

] initially favored an epileptic cause, but seizure

activity is not witnessed during or after the episode.

The low recurrence rate of TGA also argues against an

epileptic etiology. Electroencephalogram (EEG) record-

ings have been normal even during the episode [

Unwitnessed epileptic seizures would be a possible cause

of transient amnesia, however, and such cases are more

likely than typical TGA patients to have recurrent

attacks.

A second theory of TGA is vascular, or focal

ischemia [

]. As mentioned above, transient amnesia

can occur in migraine [

] and with presumed

transient ischemic attacks [

,

]. Migraine-associated

transient amnesia, like epilepsy, is more likely to be

recurrent than idiopathic TGA.

Typical TGA tends to occur in middle-aged and

elderly patients, who frequently have risk factors for

cerebrovascular disease, but follow-up studies have not

indicated a high incidence of transient ischemic attacks

or stroke [

,

,

]. Kushner and Hauser [

] used a

case

–control method and confirmed a higher incidence of

vascular risk factors in patients with TGA versus neuro-

logic controls, but most of the association went away

when patients with known ischemic attacks were exclud-

ed. Also contrary to the vascular hypothesis is the absence

of focal neurologic signs, such as visual field defects,

during the TGA episode.

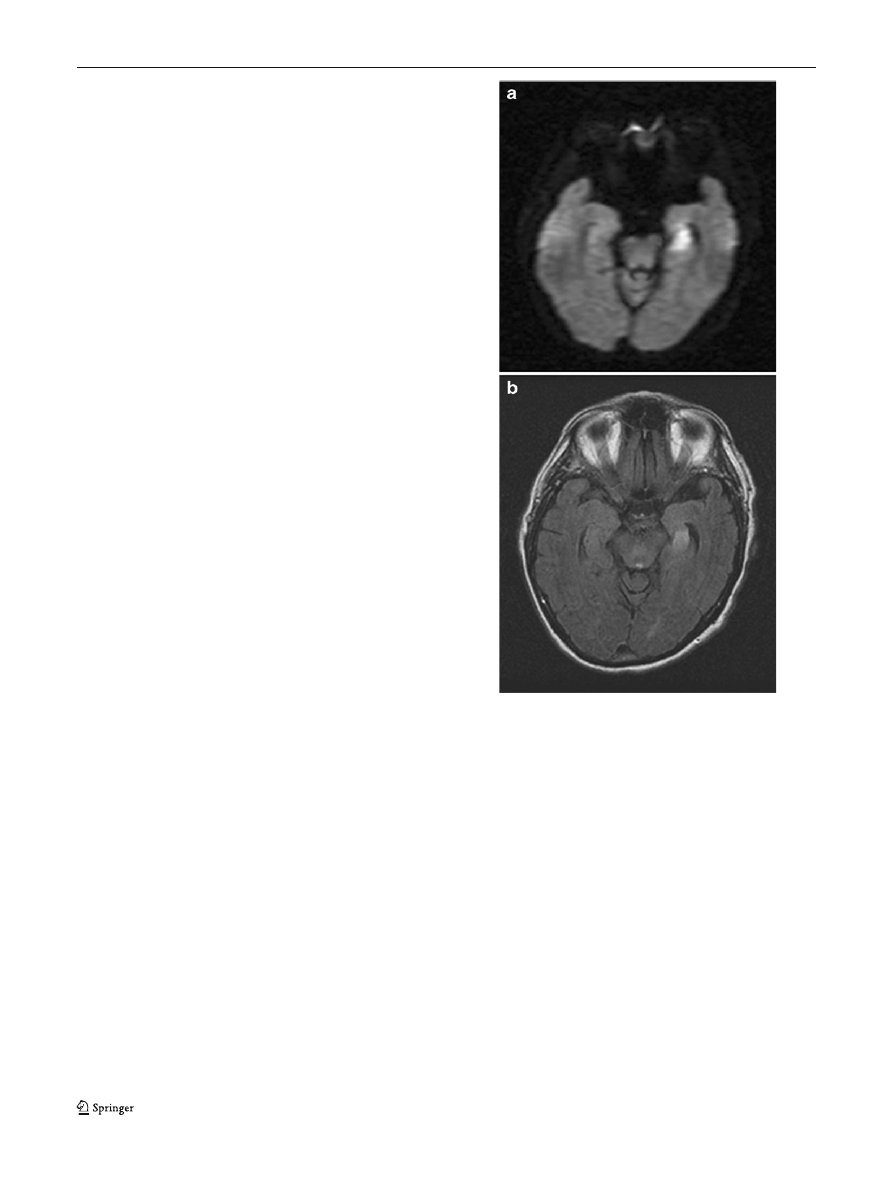

Proponents of the ischemic theory of TGA have been

supported by reports of diffusion bright lesions in the

hippocampus on MRI. Recently, ultrasensitive brain imag-

ing modalities such as diffusion-weighted MRI and positron

emission tomography (PET) have been performed in

patients with TGA. Strupp et al. [

] reported that 7 of 10

patients imaged during TGA episodes showed abnormal

diffusion MRI signal in the left hippocampus; of these

seven cases, three had bilateral hippocampal abnormalities.

Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep (2011) 11:578

–582

579

The authors postulated that reduced extracellular space

caused by edema or spreading depression might be the

cause; permanent infarctions were not found. Other inves-

tigators have found frontal lobe abnormalities by diffusion-

weighted MRI [

] or PET imaging [

]. Several reports

have described diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) lesions

in a high proportion of TGA cases, especially hippocampal

abnormalities [

]. The last article cited reported a

higher detection rate, 11/32 compared with 0/32 with 3 T

MRI, compared with 1.5 T. The experience in our hospital

has been less positive, in that most patients have had

negative DWI MRI scans. However, some investigators

have discovered such lesions several days after onset, and

our practice has been to obtain the scan immediately upon

hospitalization for the event. Two cases in whom we saw

left medial temporal DWI lesions have had lasting, and not

transient amnesia; an example is shown in Fig.

. In

addition to the lack of other stroke signs in these patients,

and their low incidence of stroke in follow-up, diffusion

bright lesions may occur in association with seizures,

spreading depression, and other non-stroke causes. These

studies do not prove an ischemic etiology for TGA; rather,

they indicate transient dysfunction in either the hippocam-

pal system or its connections (Papez

’s circuit), as would be

expected.

A recent, vascular theory of TGA holds that venous

stasis may cause transitory ischemia in the hippocampus.

Several reports have emerged of incompetent valves in the

jugular vein, with back pressure [

–

•]. Proponents

of this theory point out that many cases of TGA appear to

be precipitated by events associated with the Valsalva

maneuver, such as severe stressors, sexual intercourse, and

so forth. Cejas et al. [

•] found valvular insufficiency by

Doppler ultrasound on at least one jugular vein in 113/142

patients with TGA. These accounts fail to explain the very

low recurrence rate of TGA, given that the individuals

always have venous incompetence and frequently do

Valsalva maneuvers.

Despite all of the theories, case series, and studies, the

etiology of TGA remains elusive. As stated by Altamura

and Vernieri [

],

“Investigating the case of TGA, we have

definitely identified the suspects, but we still have to prove

them guilty.

”

The evaluation of a patient with transient amnesia should

include observation of the patient until the symptoms have

passed. Brain imaging with CT or MRI is usually performed

to exclude other causes of memory loss. Ultrasound

evaluation of the jugular veins could be considered, if this

theory of TGA gains traction in the years ahead. EEG and

drug screening should also be performed if there is clinical

suspicion of seizures or drug abuse. There is no clear

evidence regarding treatment, and reassurance is the most

appropriate stance. Treatment of vascular risk factors, and

perhaps a baby aspirin daily, constitutes usual therapeutic

maneuvers.

Conclusions

TGA is a syndrome of unknown cause, or perhaps multiple

causes, although it is closely mimicked by transient

amnesia caused by migraine, ischemia, seizures, or trauma.

Fig. 1 Shows a 69-year-old man with history of hypertension and

hyperlipidemia, presented with sudden onset of memory difficulty,

repeatedly asking his wife questions about where they were and why

they were there. MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) shows

acute infarction of the left hippocampus. The memory loss did not

resolve completely. a DWI sequence MRI in patient with amnesia,

which persisted. b Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)

sequence, same patient with amnesia

580

Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep (2011) 11:578

–582

A thorough evaluation is appropriate, to exclude more

serious and potentially recurrent causes of transient amne-

sia. Reassurance is the usual treatment for the idiopathic

syndrome of TGA.

Disclosure

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article

was reported.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been

highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

1. Benon R. Les ictus amnesiques dans les demences

‘organiques’.

Ann Med Psychol. 1909;67:2007

–19.

2. Bender MB. Syndrome of isolated episode of confusion with

amnesia. J Hillside Hosp. 1956;5:212

–5.

3. Guyotat MM, Courjon J. Les ictus amnesiques. J Med Lyon.

1956;37:697

–701.

4. Fisher CM, Adams RD. Transient global amnesia. Trans Am

Neurol Assoc. 1958;83:143

–6.

5. Fisher CM, Adams RD. Transient global amnesia. Acta Neurol

Scand. 1964;40 Suppl 9:1

–83.

6. Hodges JR, Warlow CP. The aetiology of transient global amnesia:

a case control study of 114 cases with prospective follow-up.

Brain. 1990;113:639

–57.

7. Miller JW, Peterson RC, Metter EJ. Transient global amnesia:

clinical characteristics and prognosis. Neurology. 1987;37:733

–7.

8. Zorzon M, Antonutti L, Mase G, et al. Transient global

amnesia and transient ischemic attack. Natural history, vascu-

lar risk factors, and associated conditions. Stroke.

1995;26:1536

–42.

9. Hodges JR, Warlow CP. Syndromes of transient amnesia: towards

a classification. A study of 153 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatr. 1990;53:834

–43.

10. Nausieda PA, Sherman IC. Long-term prognosis in transient

global amnesia. JAMA. 1979;241:392

–3.

11. Olesen J, Jorgensen MB. Leao

’s spreading depression in the

hippocampus explains transient global amnesia: a hypothesis. Acta

Neurol Scand. 1986;73:219

–20.

12. Shuping JR, Rollinson RD, Toole JF. Transient global amnesia.

Ann Neurol. 1980;7:281

–5.

13.

•• Bartsch T, Deuschl G. Transient global amnesia: functional

anatomy and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:205

–14.

This is a good review of the syndrome, with discussion of the

neuroanatomy of memory pathways.

14. Lynch S, Yarnell PR. Retrograde amnesia: delayed forgetting after

concussion. Am Psychol. 1973;86:643

–50.

15. Haas DC, Ross GS. Transient global amnesia triggered by mild

head trauma. Brain. 1986;109:251

–7.

16. Gilbert GJ. Transient global amnesia: manifestation of medial

temporal lobe epilepsy. Clin Electroencephalogr. 1978;9:147

–

52.

17. Dugan TM, Nordgren RD, O

’Leary P. Transient global amnesia

associated with bradycardia and temporal lobe spikes. Cortex.

1981;17:633

–8.

18. Bilo L, Meo R, Ruosi P, et al. Transient epileptic amnesia: an emerging

late-onset epileptic syndrome. Epilepsia. 2009;50 Suppl 5:58

–61.

19. Poser CM, Ziegler DK. Temporary amnesia as a manifestation of

cerebrovascular insufficiency. Trans Am Neurol Assoc.

1960;85:221

–3.

20. Gorelick PB, Amico LL, Ganellen R, Benevento LA. Transient

global amnesia and thalamic infarction. Neurology. 1988;38:496

–9.

21. Bogousslavsky J, Regli F. Transient global amnesia and stroke.

Eur Neurol. 1988;28:106

–10.

22. Shuttleworth EC, Wise GR. Transient global amnesia due to

arterial embolism. Arch Neurol. 1973;29:340

–2.

23. Gilbert JJ, Benson DF. Transient global amnesia: report of two

cases with definite etiologies. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1972;154:461

–4.

24. Olivarius B, Jensen TS. Transient global amnesia in migraine.

Headache. 1979;19:335

–8.

25. Caplan L, Chedru F, Lhermitte F, Mayman C. Transient global

amnesia and migraine. Neurology. 1981;31:1167

–70.

26. Olesen J, Jørgensen MB. Leao

’s spreading depression in the

hippocampus explains transient global amnesia. A hypothesis.

Acta Neurol Scand. 1986;73:219

–20.

27. Ehyai A, Fenichel GM. The natural history of acute confusional

migraine. Arch Neurol. 1978;35:368

–9.

28. Schmidtke K, Ehmsen L. Transient global amnesia and migraine.

A case control study. Eur Neurol. 1998;40:9

–14.

29. Morris HH, Estes ML. Traveler

’s amnesia. Transient global

amnesia secondary to Triazolam. JAMA. 1987;258:945

–6.

30. Tsai MY, Tsai MH, Yang SC, et al. Transient global amnesia-like

episode due to mistaken intake of zolpidem: drug safety concern

in the elderly. J Patient Saf. 2009;5:32

–4.

31. Goodwin DW, Crane JB, Guze SB. Alcoholic

“blackouts”: a

review and clinical study of 100 alcoholics. Am J Psychiatr.

1969;126:191

–8.

32. Hartley TC, Heilman KM, Garcia-Bengochia F. A case of a

transient global amnesia due to a pituitary tumor. Neurology.

1974;24:998

–1000.

33. Lisak RP, Zimmerman RA. Transient global amnesia due to a

dominant hemisphere tumor. Arch Neurol. 1977;34:317

–8.

34. Jaffe R, Bender MB. E.E.G. studies in the syndrome of isolated

episodes of confusion with amnesia

“transient global amnesia”. J

Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1966;29:472

–4.

35. Mathew NT, Meyer JS. Pathogenesis and natural history of

transient global amnesia. Stroke. 1974;5:303

–11.

36. Kushner M, Hauser W. Transient global amnesia: a case-control

study. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:684

–91.

37. Strupp M, Bruning R, Wu RHH, et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI in

transient global amnesia: elevated signal intensity in the left mesial

temporal lobe in 7 of 10 patients. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:164

–70.

38. Ay H, Furie KL, Yamada K. Diffusion-weighted MRI characterizes

the ischemic lesion in transient global amnesia. Neurology.

1998;51:901

–3.

39. Eustache F, Desgranges B, Petit-Taboue MC. Transient global

amnesia: implicit/explicit memory dissociation and PET assess-

ment of brain perfusion and oxygen metabolism in the acute stage.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1997;63:357

–67.

40. Yang Y, Kim S, Kim JH. Ischemic evidence of transient global

amnesia: location of the lesion in the hippocampus. J Clin Neurol.

2008;4:59

–66.

41. Alberici E, Pichiecchio AE, Caverzasi E, et al. Transient global

amnesia: hippocampal magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities.

Funct Neurol. 2008;23:149

–52.

42. Lee SY, Kim WJ, Suh SH, et al. Higher lesion detection by 3.0 T

MRI in patients with transient global amnesia. Yonsei Med J.

2009;50:211

–4.

43. Lewis SL. Aetiology of transient global amnesia. Lancet.

1998;352:397

–9.

44. Sander D, Winbeck K, Etgen T, et al. Disturbance of venous flow

patterns in patients with transient global amnesia. Lancet.

2000;356:1982

–4.

Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep (2011) 11:578

–582

581

45. Schrieber SJ, Doepp F, Klingebiel R, Valdueza JM. Internal

jugular vein valve incompetence and intracranial venous anatomy

in transient global amnesia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr.

2005;76:509

–13.

46. Chung C, Hsu H, Chao A, et al. Detection of intracranial venous

reflux in patients with transient global amnesia. Neurology.

2006;66:1873

–7.

47.

• Cejas C, Cisneros LF, Lagos R, et al. Internal jugular vein valve

incompetence is highly prevalent in transient global amnesia. Stroke.

2010;41:67

–71. This article contains an up-to-date summary on the

evidence for jugular vein incompetence as a cause of TGA.

48. Altamura C, Vernieri F. Internal jugular vein valve incompetence

in transient global amnesia. More circumstantial evidence or the

proof solving the mystery? Stroke. 2010;41:1

–2.

582

Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep (2011) 11:578

–582

Document Outline

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

grupa 1 pamiec Zakieta

grupa 1 pamiec Schudy

grupa 1 pamiec Zochowska

KOLOSY, Kolos-pamięć,6, grupa A

03 Odświeżanie pamięci DRAMid 4244 ppt

wykład 12 pamięć

8 Dzięki za Pamięć

06 pamięć proceduralna schematy, skrypty, ramyid 6150 ppt

test poprawkowy grupa 1

19 183 Samobójstwo Grupa EE1 Pedagogikaid 18250 ppt

Pamięć

PAMIĘĆ 3

Architektura i organizacja komuterów W5 Pamięć wewnętrzna

Grupa 171, Podstawy zarządzania

więcej podobnych podstron