Access Provided by Univ.Lisboa - Fac.Letras e ICS at 09/20/11 2:45PM GMT

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD

M

ARK

A

RONOFF

Stony Brook University

All linguists assume that the meaning of a complexsyntactic expression is determined by its

structure and the meanings of its constituents. Most believe that the meanings of words are

similarly compositionally derived from the meanings of their constituent morphemes. The classical

lexicalist hypothesis holds instead that the central basic meaningful constituents of language are

not morphemes but lexemes. This article supports that hypothesis with evidence from syntax,

lexical semantics, and morphology. Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language (ABSL) is a new language

that is compositional down to its smallest pieces, in which these pieces are lexemes. ABSL shows

that a language can emerge very quickly in which lexemes are basic. Next comes evidence against

the claim that newly derived words diverge from compositionality only because they are stored

in memory. Finally, Hebrew verb roots are shown to have robust morphological properties that

bear no relation to meaning and little to phonology, leaving room for morphemes within a lexeme-

based framework, but not as the basic meaningful atoms of language.*

Linguists have followed two ways in the study of words. One seeks to accommodate

the word, the other to obliterate it. I defend here an approach to language that respects

the autonomy of arbitrary individual words or lexemes and privileges the interaction

between the idiosyncrasies of lexemes and a highly regular linguistic system.

1

Putting

this approach in the context of the history of our field, I show that ‘Chaque mot a son

histoire [Each word has its [own] history]’ (Gillie´ron; see Malkiel 1967:137) in ‘un

syste`me ou` tout se tient [a system where everything hangs together]’ (Meillet 1903:

407), but instead of phonology, which was Gillie´ron’s main concern, I concentrate on

syntax, semantics, and morphology. I am not claiming that the lexeme is the only

idiosyncratic element in language, but that it is the central such element.

1. C

OMPOSITIONALITY

. All linguists assume that natural languages are composi-

tional, which we understand informally to mean that the meaning of a complexsyntactic

expression is determined by its structure and the meanings of its constituents.

2

The main

argument for compositionality of natural language is rooted in syntactic productivity and

was stated succinctly by Frege:

The possibility of our understanding sentences which we have never heard before rests evidently on

this, that we can construct the sense of a sentence out of parts that correspond to words. (Frege 1980

[1914]:79)

* This article is a revised version of my Presidential address, delivered at the annual meeting of the LSA

in January 2006. Much of the content presented here is the result of joint work with Frank Anshen, Robert

Hoberman, Irit Meir, Carol Padden, Wendy Sandler, and Xu Zheng. I am grateful for discussion to my

departmental colleagues at Stony Brook: Christina Bethin, Ellen Broselow, Dan Finer, Alice Harris, Heejeong

Ko, Richard Larson, and Lori Repetti; and to my former colleague Peter Ludlow. Thanks to the members

of my immediate family for providing data and editorial assistance. This research was supported in part by

the US-Israel Binational Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Stony Brook Provost’s

Office.

1

Psycholinguists, for example Levelt (1989), use the term

LEMMA

for the purely syntactic and semantic

aspects of lexemes and the term

LEXEME

for what linguists would call phonological word. I use lexeme to

refer to the entire lexical entry, including syntax, semantics, and forms.

2

For a general overview of compositionality (Frege’s principle), see Szabo 2007. I am not suggesting

that all linguists agree on what the units are over which compositionality operates, only that compositionality

has a role in language.

803

LANGUAGE, VOLUME 83, NUMBER 4 (2007)

804

Exactly what these ‘parts that correspond to words’ are in natural languages has been

debated since the beginning of linguistics (cf. the Ancient Greek grammatical term

MEROS LOGOU

‘piece/part of speech’). Saussure called them (simple) signs, without

being entirely clear about what linguistic units he took to be simple signs, though for

the most part his examples are what modern linguists would call lexemes (de Saussure

1975, Carstairs-McCarthy 2005). A term like

ANTIDECOMPOSITIONALIST

‘opposed to the

view that the meanings of words can be broken down into parts’, for example, can be

analyzed into [[anti [[[de [com

⳱pos-it]

V

]

V

ion]

N

al]

A

]

A

ist]

A

.

3

The standard view is

that the meanings of this word and others like it are compositionally derived from the

meanings of these constituent morphemes, making morphemes, not words, the ‘parts

that correspond to words’ in natural languages. A bit confusing, but linguists like

exoticizing the ordinary.

I am antidecompositionalist by temperament, because I believe that what happens

inside lexemes (Matthews 1972) is qualitatively different from what happens outside

them. My adherence to this classic version of the

LEXICALIST HYPOTHESIS

(Chomsky

1970) is grounded in a simple love of words. As I wrote in my first publication (Aronoff

1972), on the semantics of the English word growth and its relevance to the lexicalist

hypothesis, ‘all a person had to do [in order to notice the peculiar differences in meaning

between the verb grow and the noun growth] was to look the words up in a reputable

dictionary, or think for a long time: grow–growth’ (1972:161). Yet very few modern

linguists either look words up in a reputable dictionary or think about them for a long

time. Philosophers do, but linguists don’t often think much about the subtleties of word

meanings, which is why most linguists are not antidecompositionalists.

The locus classicus of antidecompositionalist lexicalism is Chomsky 1970. This

particular work, however, can be read in a myriad of ways, much in the way that most

of Wittgenstein’s works can be read to support a great number of contradictory positions.

What is beyond dispute is that Chomsky introduced the terms

LEXICALIST

and

LEXICALIST

HYPOTHESIS

in discussing derived nominals like refusal, eagerness, and confusion:

We might extend the base rules to accommodate the derived nominal directly (I will refer to this as

the lexicalist position) . . . [T]here is no a priori insight into universal grammar . . . that bears on this

question, which is a purely empirical one. (Chomsky 1970:88)

Chomsky brings three types of empirical evidence to bear on the issue of whether such

derived nominals ‘are, in fact, transformationally related to the associated propositions’:

restricted productivity, baselike syntax, and the fact that ‘the semantic relations between

the associated proposition and the derived nominal are quite varied and idiosyncratic’

(1970:188). He concludes that they are not transformationally related and that ‘The

strongest and most interesting conclusion that follows from the lexicalist hypothesis is

that derived nominals should have the form of base sentences’ (212), by which he

means that derived nominals are inserted into lexical structures in the same way that

simple base nouns are. This is the original lexicalist hypothesis, the idea that some

members of major lexical categories (lexemes) are not derived by the same apparatus

that derives sentences but are inserted into lexical categories in the base just as simple

lexemes are.

4

What I call the

CLASSICAL LEXICALIST HYPOTHESIS

(Jackendoff 1975, Aro-

3

The form pos-it is the allomorph of the root pose that appears before the suffix -ion.

4

Chomsky provides a sketch of an apparatus that might account for derived nominals nontransformation-

ally, but that apparatus has been very little explored since, except for X-bar theory, which was designed to

express the parallelism between the internal structures of phrasal categories like NP and VP without having

to derive one from the other transformationally.

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD

805

noff 1976) extends the scope of the original hypothesis to all lexemes and lexeme-

internal sign structure (derivational morphology and compounding), though not to in-

flectional morphology (which relates forms of a single lexeme to one another), and

claims that the level of the lexeme or lexical category is significant in the way that the

level of the molecule is significant in chemistry: it has properties that are worth isolating.

A

NTIDECOMPOSITIONALISM

is related to this classical lexicalist hypothesis: it says that

the scope of syntax-based logical compositionality should not be extended below the

lexeme because lexeme-internal structure (however it is described) is different from

lexeme-external structure.

An important and often forgotten point about antidecompositionalism is that, like

Chomsky’s original lexicalist hypothesis, it is an empirical claim, not a theoretical

postulate. Still, we antidecompositionalists do have theoretical obligations that our

opponents do not, because we must account for the internal properties of lexemes in

a different way from how we account for syntax(including inflection).

5

That is what

I have been trying to do for the last thirty-five years.

Also important is the fact that antidecompositionalists do not deny the value of

morphemes, just as chemists do not deny the value of atoms and particles. There is

plenty of evidence, linguistic and psycholinguistic, for morphemes and roots and for

morphological relatedness. But none of this evidence, pace Stockall & Marantz 2006,

supports a purely morpheme-based theory over one that recognizes lexemes but also

recognizes roots and morphemes as morphologically significant elements, albeit not as

reliable Saussurean signs.

6

The rest of my article is divided into three parts. First, I discuss a language that

appears to be completely compositional down to its smallest pieces, Al-Sayyid Bedouin

Sign Language (ABSL). I show that ABSL is an instantiation of Saussure’s picture of

language, with little if any structure below the level of the lexeme. ABSL thus provides

an unusual type of evidence for both compositionality and the lexicalist hypothesis,

showing that very quickly, a language can emerge on its own in which words are indeed

‘the parts that correspond to words’.

I then turn to well-known phenomena from English and present evidence against

one common misunderstanding of the special nature of words, that they diverge from

compositionality only because they are stored in memory. I review old data and present

one new example to show that even productively coined new words can be noncomposi-

tional.

I close with some traditional linguistic analysis and show that Semitic roots, the

original lexeme-internal linguistic units, have robust properties that bear no relation to

meaning and little to phonology. There is thus room for roots within a lexeme-based

framework, but not as the basic meaningful atoms of language.

The approach to morphology that I take here is lexeme-based and realizational,

using the taxonomy of morphological theories elaborated in Stump 2001. Like much

morphological research of the last thirty years it is rooted in the work of P. H. Matthews

(1972, 1974). It also has close affinities to Corbin 1984 and Anderson 1992. Carstairs-

McCarthy 2002, Booij 2005, and Aronoff & Fudeman 2005 are recent introductions

5

Decompositionalists have their own burdens, most vexing among which is the general problem of

recoverability of deletion (Chomsky 1970, n. 11).

6

For definitions and extended discussion of the terms

LEXEME

and

ROOT

, see Aronoff 1994:Ch. 1. I am

using

MORPHEME

in the classic sense of Harris 1951, extended following the discussion in Aronoff 1976:

Ch. 2.

LANGUAGE, VOLUME 83, NUMBER 4 (2007)

806

to morphology within this tradition. Spencer 2000 provides a good brief overview. I

do not think that it is unfair to say that the lexeme-based realizational approach has been

prevalent among practicing morphologists for the last quarter century. Nonpractitioners,

however, seem to prefer morpheme-based approaches. This raises the question of how

much one should trust the experts, but I do not attempt to answer that question here.

2. A

L

-

SAYYID BEDOUIN SIGN LANGUAGE

. For several years, I have been privileged to

be a member of a team, along with Wendy Sandler, Irit Meir, and Carol Padden, working

on Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language (ABSL). ABSL has arisen in the last seventy

years in an isolated endogamous community with a high incidence of nonsyndromic

genetically recessive profound prelingual neurosensory deafness (Scott et al. 1995).

What distinguishes ABSL from all other well-documented new languages are the cir-

cumstances of its creation and use, which show neither discontinuity of social structure

nor the influence of other languages.

In the space of one generation from its inception, systematic word order has emerged

in the language. This emergence cannot be attributed to influence from other languages,

since the particular word orders that appear in ABSL differ from those found both in

the ambient spoken languages in the community and in other sign languages in the

area.

The Al-Sayyid Bedouin group was founded almost two hundred years ago in the

Negev region of present-day Israel. The group is now in its seventh generation and

contains about 3,500 members, all residing together in a single community exclusive

of others. Consanguineous marriage has been the norm in the group since its third

generation. Such marriage patterns are common in the area and lead to very strong

group-internal bonds and group-external exclusion. Within the past three generations,

over one hundred individuals with congenital deafness have been born into the commu-

nity, all of them descendants of two of the founders’ five sons. Thus, the time at which

the language originated and the number of generations through which it has passed can

be pinpointed. All deaf individuals show profound prelingual neurosensory hearing

loss at all frequencies, have an otherwise normal phenotype, and are of normal intelli-

gence. Scott and colleagues (1995) identify the deafness as (recessive) DFNB1 and

show that it has a locus on chromosome 13q12 similar to the locus of several other

forms of nonsyndromic deafness.

The deaf members of the community are fully integrated into its social structure and

are not shunned or stigmatized (Kisch 2004). Both male and female deaf members of

the community marry, always to hearing individuals. The deaf members of the commu-

nity and a significant fraction of its hearing members communicate by means of a sign

language. Siblings and children of deaf individuals, and other members of a household

(which may include several wives and their children), often become fluent signers.

Members of the community generally recognize the sign language as a second lan-

guage of the village. Hearing people in the village routinely assess their own proficiency,

praising those with greater facility in the language. Those who have any familiarity

with Israeli Sign Language, including those who have attended schools for the deaf

outside the village, recognize that the two sign languages are distinct. Nor do Al-Sayyid

signers readily understand the Jordanian sign language used in simultaneous interpreting

on Jordanian television programs received in the area.

Many of the signers in this community are hearing, a highly unusual linguistic situa-

tion, but one that is predicted to arise as a consequence of recessive deafness in a

closed community (Lane et al. 2000). One result of the recessiveness is that there are

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD

807

a proportionately large number of deaf individuals distributed throughout the commu-

nity (over 4 percent). This means that more hearing members of the community have

daily contact with deaf members, and consequently signing is not restricted to deaf

people. Furthermore, each new generation of signers is born into a nativelike environ-

ment with numerous adult models of the language available to them. ABSL thus presents

a unique opportunity to study a new language that has grown inside a stable community

without obvious external influence. We have identified three generations of signers.

The first generation in which deafness appeared in the community (the fifth since the

founding of the community) included fewer than ten deaf individuals, all of whom are

deceased. Information on their language is limited to reports that they did sign and one

very short videotape record of one of these individuals. I report here only on the

language of the second generation.

I discuss the order of signs within sentences and within phrases in the language,

based on a tally of all sentences in a database that consist of more than one sign (Sandler

et al. 2005). Sentences consisting solely of a predicate and utterances consisting solely

of nouns were set aside. We first tallied the order among the major elements of the

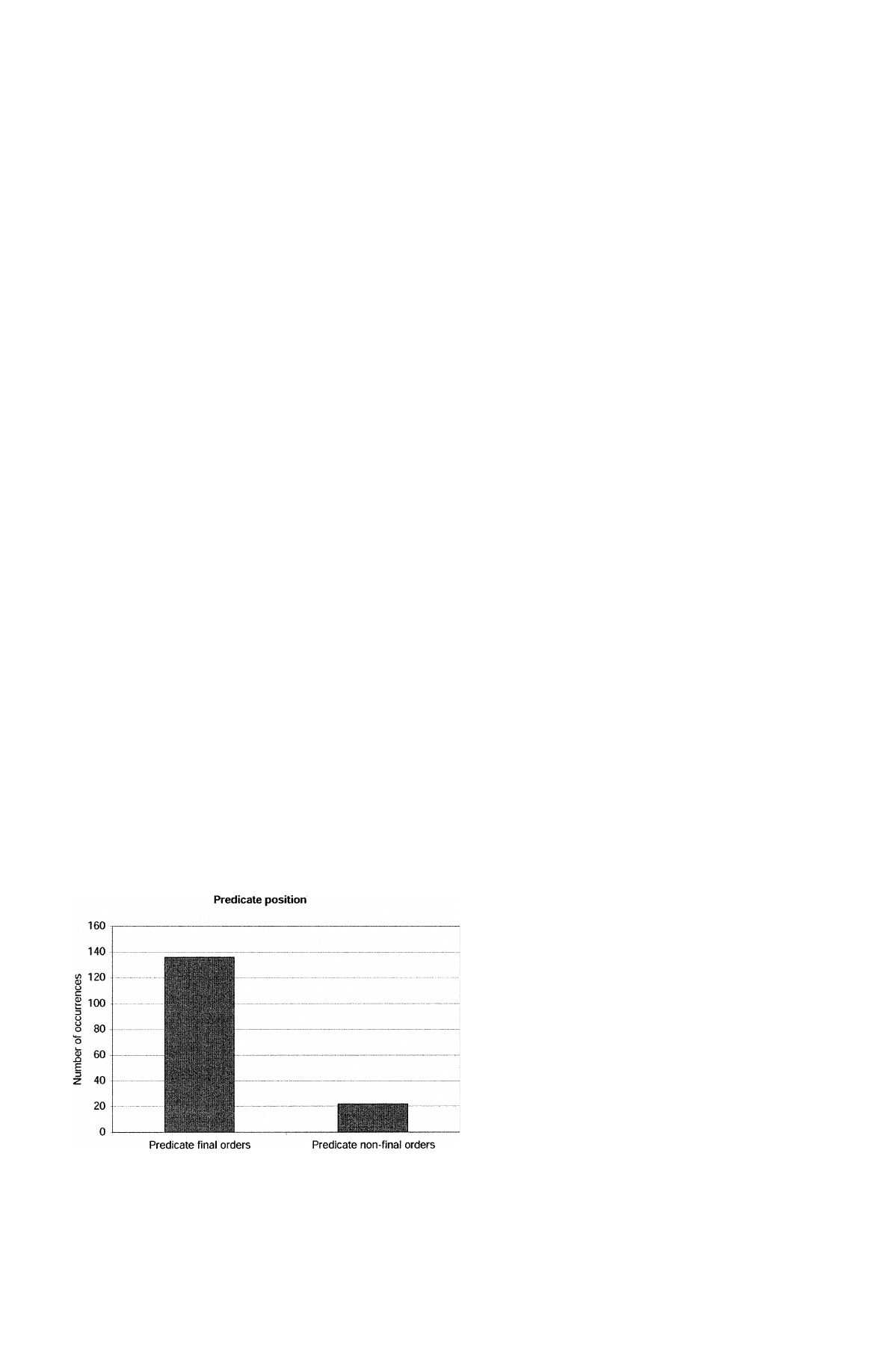

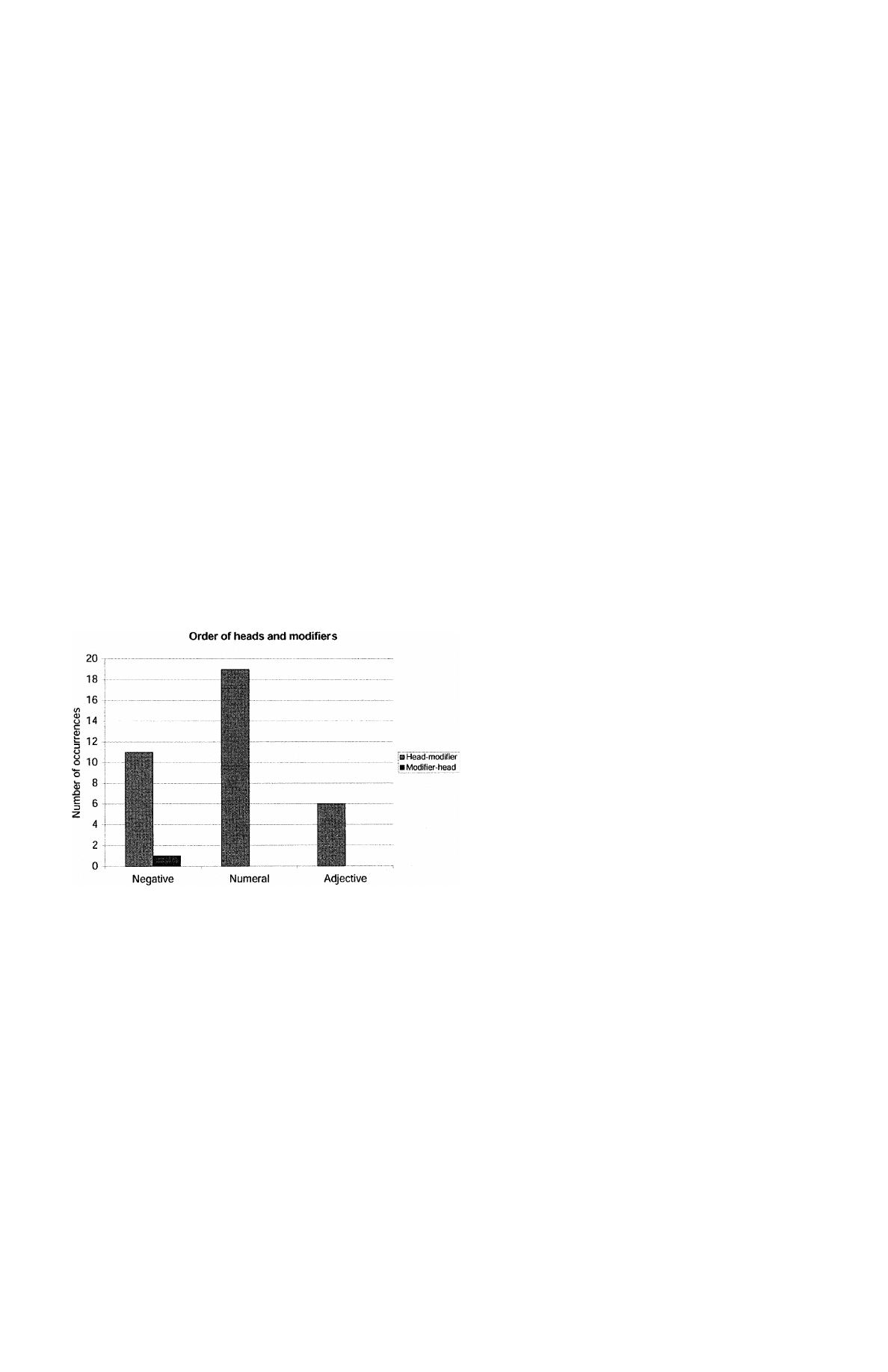

remaining clauses, the predicate (henceforth V) and its arguments. Figure 1 shows the

order of predicates relative to arguments within the clauses considered in our count.

Out of 158 clauses, 136 are predicate-final.

F

IGURE

1. ABSL is predicate-final.

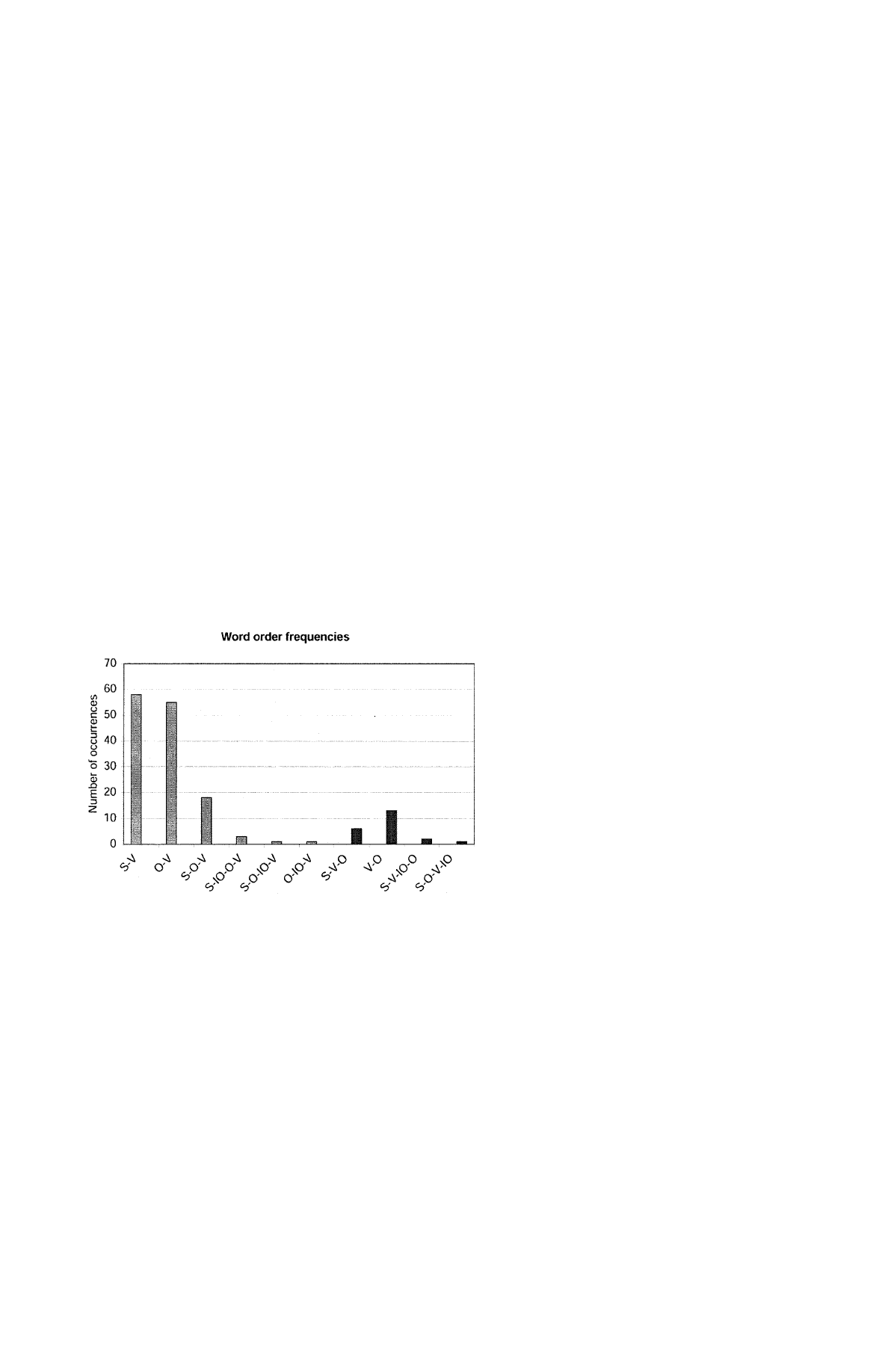

Figure 2 shows the frequency of the relative orders of S, O, IO, and V within the

data (following standard practice, we lump together O and IO unless a clause contains

both). One hundred and twenty-sixclauses contain only one noun, of which fifty-eight

contain S and V, and sixty-eight O and V. Where two nouns are mentioned in a clause,

S precedes O (in all thirty-two cases). S never follows V. Thus we conclude that the

prevalent word order for ABSL sentences is SOV. A binomial test yields statistically

reliable p-values of less than 0.00001 for this and all other word-order effects reported

here.

LANGUAGE, VOLUME 83, NUMBER 4 (2007)

808

F

IGURE

2. Major constituent orders in ABSL data.

We next considered the order of modifier elements within phrases (adjectives, nega-

tives, and numerals) relative to their head nouns and verbs. As shown in Figure 3, in

all instances but one, the modifier follows its head.

Overall, we find structural regularities in the order of signs in the language: SOV

order within sentences, and Head-Modifier order within phrases.

7

These word orders

cannot be attributed to the ambient spoken language. The basic word order in the spoken

Arabic dialect of the hearing members of the community, as well as in Hebrew, is

SVO. This generation of signers had little or no contact with Israeli Sign Language,

whose word order appears to vary more widely in any case. Nor can the Head-Modifier

order be ascribed to the ambient colloquial Arabic dialect of the community. In this

dialect, and in Semitic languages generally, although adjectives do follow nouns, numer-

als precede nouns; and negative markers only rarely follow their heads. Hence the

robust word-order pattern exhibited by the data is all the more striking, since it cannot

be attributed to the influence of other languages; rather, this pattern should be regarded

as an independent development within the language.

This remarkable structural clarity breaks down entirely when we look inside words,

where we find very little structure, either morphological or phonological. The language

does have a fair number of compounds, but compounds are not morphological in the

strict sense, since they are composed entirely of words and do not contain any bound

elements.

8

Sign languages are known for their robust inflectional morphology, espe-

7

The two orders are not symmetrical, but claims about symmetry in this domain have not stood up well

over time (Croft 2003).

8

Better candidates for morphological structure are the size and shape classifiers that are found in some

signs in ABSL. These are limited in complexity and productivity, but may be precursors of the rich and

productive classifier constructions found in more established sign languages (Emmorey 2003).

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD

809

F

IGURE

3. Relative orders of a modifier and its head in ABSL.

cially their complexverb agreement systems, which arise very quickly in the history

of individual languages (Aronoff, Meir, & Sandler 2005). Our team was therefore

surprised to discover that ABSL has no agreement morphology, indeed no inflectional

morphology at all (Aronoff, Meir, Padden, & Sandler 2005). Nor does it appear to have

a phonological system of the kind we are familiar with in other sign languages.

Phonology is an instantiation of what Hockett (1960) calls duality of patterning, or

what others have called double articulation (Martinet 1957). When we say that a sign

language has phonology, we are saying that it has a set of discrete meaningless con-

trastive elements (handshapes, locations, and movements) that form their own system,

with constraints on their combination, constituting a second articulation independent

of the first articulation of meaningful elements. This system of contrastive elements

makes up the signifiant of the Saussurean sign. It was the existence of such a system

in American Sign Language that first led William Stokoe to proclaim its legitimacy as

a language (Stokoe 1960).

ABSL appears not to have a system of discrete meaningless elements within words.

Instead, each word has a conventionalized form, with tokens roughly organized around

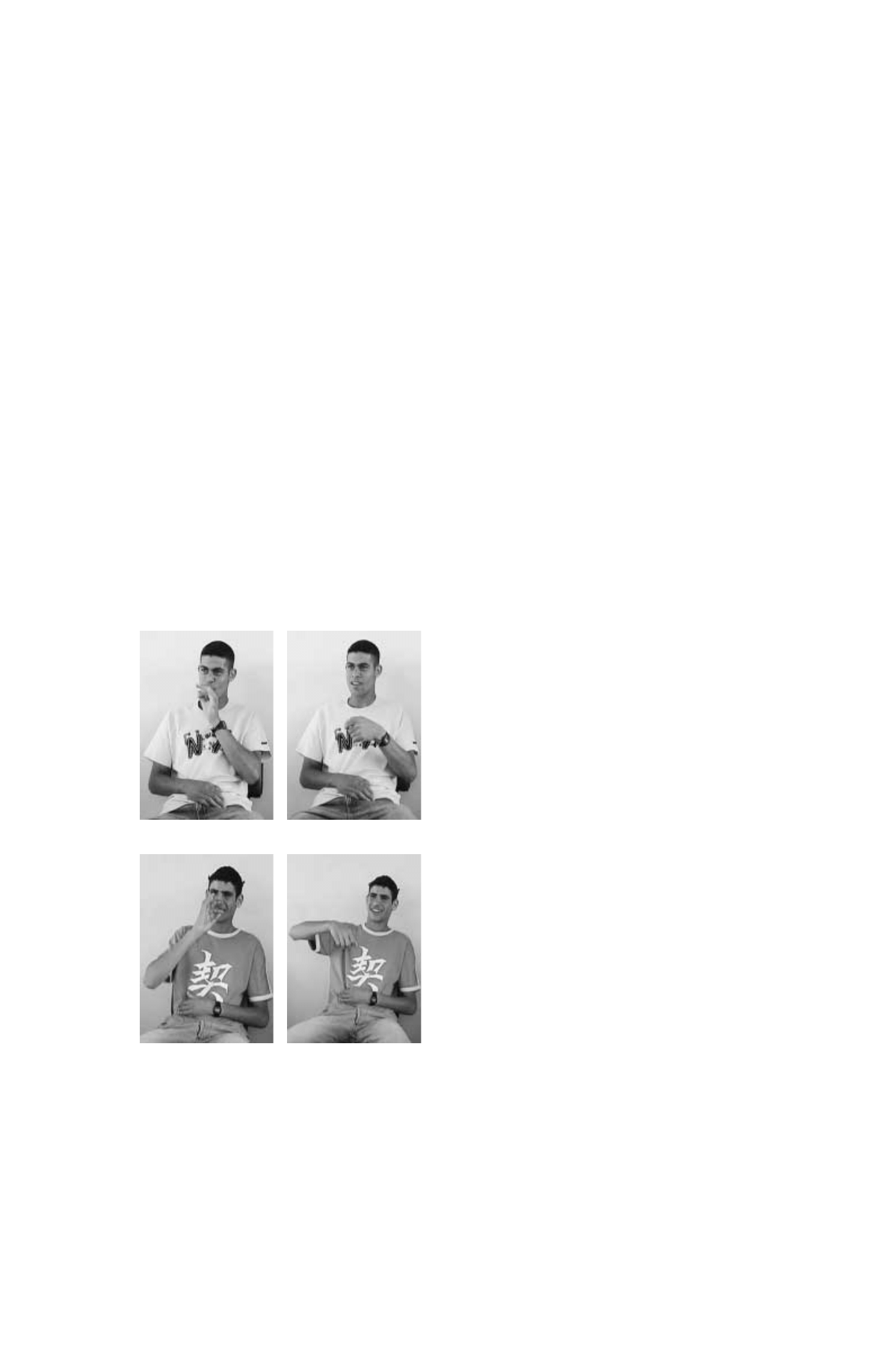

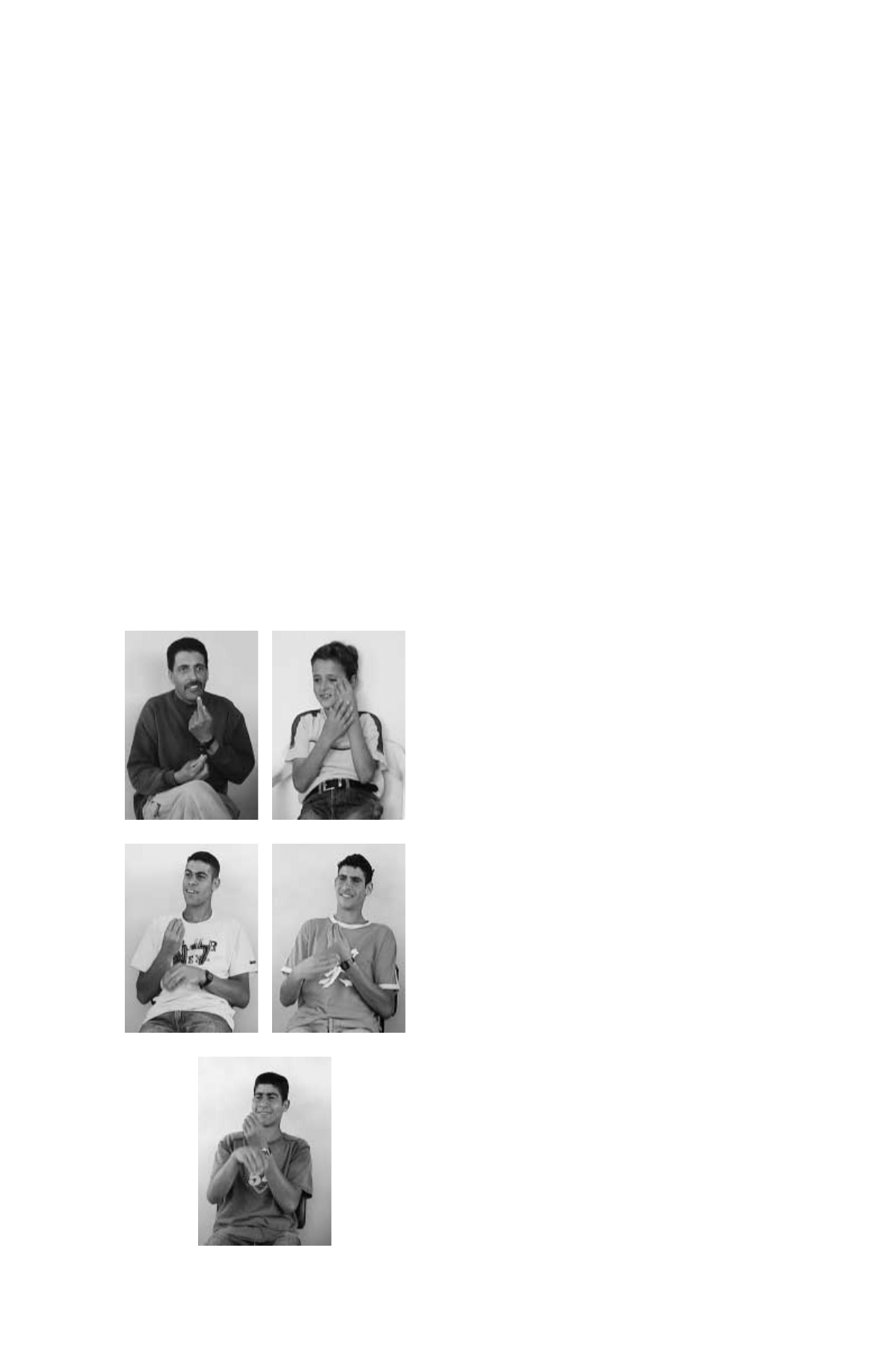

a prototype, but no internal structure, as the following illustrations of the ABSL signs

KETTLE (Figure 4) and BANANA (Figure 5) illustrate. KETTLE is a compound, of

which the first component is CUP and the second either POUR or BOIL. For lack of

space, it is impossible to show more than a few examples of each, but in both, and

especially in BANANA, there is considerable variation among individual signers. The

variation found among signers in many words in our data (of which BANANA is a

good example) lies precisely along the parameters that create contrasts in other sign

languages. The difference in the amount of variance between KETTLE and BANANA

may also be taken as an indication that certain signs, like KETTLE, are becoming

more conventionalized, but conventionalization does not equal phonology. It is also

LANGUAGE, VOLUME 83, NUMBER 4 (2007)

810

F

IGURE

4a. KETTLE (CUP

Ⳮ POUR).

F

IGURE

4b. KETTLE (CUP

Ⳮ POUR).

noteworthy that the signers in Figures 5c–e, whose sign for BANANA is very similar,

are brothers. We do find much more similarity in sign form within single families.

ABSL has been able to develop into a full-fledged linguistic system without benefit

of phonology because of the visual medium of signing, which has many more dimen-

sions than sound does and which allows for direct iconicity (Aronoff, Meir, & Sandler

2005). As Hockett notes (1960:95):

There is excellent reason to believe that duality of patterning was the last property to be developed,

because one can find little if any reason why a communicative system should have this property unless

it is highly complicated. If a

VOCAL-AUDITORY SYSTEM

[emphasis added—MA] comes to have a larger

and larger number of distinct meaningful elements, those elements inevitably come to be more and

more similar to one another in sound. There is a practical limit, for any species or any machine, to the

number of distinct stimuli that can be discriminated, especially when the discriminations typically have

to be made in noisy conditions.

It may be that ABSL will develop phonology as it ages, perhaps simply as a function

of the size of its vocabulary, as Hockett suggests (see Nowak & Krakauer 1999 for a

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD

811

5a.

5b.

5c.

5d.

5e.

F

IGURE

5. BANANA.

LANGUAGE, VOLUME 83, NUMBER 4 (2007)

812

mathematical model). Indeed, our team is currently investigating questions of just this

sort. For the moment, though, ABSL is a language with a compositional syntax, but

very little word-internal structure of any kind. It is, from a certain perspective, a perfect

language (Chomsky 1995, 2000, Eco 1995).

3. T

HE MEANINGS OF MORPHOLOGICALLY COMPLEX WORDS

. The tenet that every natural

language is a unitary compositional system of sentences whose basic building blocks

are morphemes has an intellectual sister in the notion that the meaning and structure

of morphologically complexwords cannot merely be represented in terms of their

sentential paraphrases but should be formally reduced to these paraphrases, so that the

words themselves are reduced to sentences or propositions and morphology to syntax.

To proponents of this method, words and sentences really are the same kinds of things,

because words are sentences in miniature, linguistic munchkins. This idea dates back

at least to Pa¯n

ខini and it has been popular among generativists almost from the beginning;

not a surprise, since the most successful early generative analyses, notably those of

Chomsky 1957, make no distinction between syntaxand morphology, at least inflec-

tional morphology.

9

Precisely those morphologically complexword types that have seemed most akin to

sentences in the structure of their meanings, however, when studied in more detail,

provide empirical support for just the opposite conclusion: morphologically complex

words are not sentences and their meanings are arrived at in an entirely different fashion.

Almost all the evidence that I review is over twenty-five years old and much of the

field has successfully ignored it, so I am very much in the minority. Nonetheless, I

would like to take advantage of the occasion to make a new plea for what, to my mind

at least, have been very important findings.

The founding generative work in the enterprise of reducing words to sentences, as

Chomsky notes (1970:188), is Lees 1960.

10

The details of Lees’s analysis have been

forgotten, but his idea has flourished on and off ever since, more on than off, largely

unchanged except in notation. I offer two examples of Lees’s analysis. The first is what

he calls action nominals. Here are two samples of such nouns and their sentential

sources, according to Lees.

(1)

The committee appoints John

→ John’s appointment by the committee

(2)

The committee objects to John

→ The committee’s objection to John

These and others with different morphology are produced by means of a single

action nominal transformation. The second example is nominal compounds. Here Lees

discusses eight types, which include subject-predicate, subject-verb, verb-object, and

others, all based on syntactic relations. His discussion of these types takes up fifty

pages, so I can’t paraphrase it here, but a few samples are given below.

(3)

The plant assembles autos

→ auto assembly plant

(4)

The cap is white

→ white cap

(5)

The artist has a model

→ artist’s model

(6)

The sheep has a horn. The horn is like a prong

→ pronghorn

9

Synactic structures itself has a prescient short section (7.3) showing that the adjective interesting is not

derived from a sentence containing the verb interest, for precisely the sorts of reasons that I outline below.

10

One indicator of its popularity at the time is the fact that it was reprinted four times by 1966, the date

of issue of my own copy, no mean feat when one takes into account the size of the community of linguists

in the early 1960s.

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD

813

Linguists are tempted to try to reduce the structures and meanings of complexwords

to those of sentences because they have a good set of tools for studying the syntaxand

semantics of sentences, which they apply to words. But words have much less apparent

internal structure. This difference is both a blessing and a curse: we can transfer with

ease what we know about the internal structure and meanings of sentences to words,

but we have no direct way of finding out the actual extent of the isomorphism between

the two domains. We may very well be deluding ourselves.

A second problem is that, unlike sentences, words are not essentially ephemeral

objects. As Paul Bloom has shown, though syntactic development stops fairly early,

certainly before puberty, individual speakers of a language continue to accumulate

words at an astonishing rate throughout their lives and retain them in memory (Bloom

2000). They do not accumulate sentences. Because sentences are ephemeral, their mean-

ings must be compositional sums of the meanings of their parts. This was Frege’s main

argument for the compositionality of sentences in natural languages. By the same token,

because words are not so ephemeral, and more often than not retained in memory and

society, complexwords do not have to be compositional. Words that have been around

for any time at all develop idiosyncrasies that are passed on to their new learners.

There have been two lines of response to this obvious noncompositionality of some

complexwords. The more common response is to say that complexwords are composi-

tional at heart and that the departures from regularity accrete precisely because words

are stored and used. The semantic differences between sentences and complexwords

are thus purely accidental on this view, the result of nonlinguistic or noncomputational

factors.

One example in support of the position that words aren’t born with noncompositional

meaning but have it thrust upon them is the trio of words cowboy, refugee, and skinner,

which are curiously synonymous in one sense: ‘one of a band of loyalist guerillas and

irregular cavalry that operated mostly in Westchester County, New York, during the

American Revolution’ (Webster’s third new international dictionary, henceforth WIII).

Explaining why these three words came to be used to denote this particular group is

a philological adventure of precisely the sort that gives linguists a bad taste for etymol-

ogy, but it is obvious that that story has nothing to do with the compositional meaning

of any of them. Instead, this peculiar meaning arose for all three words under certain

very particular historical circumstances. The fact that this meaning of these words is

not compositional is, linguistically speaking, an accident. The meaning itself is no

more than a curiosity. This analysis allows us to preserve the intuition that words are

compositional at birth, just like sentences, but that they lose their compositional mean-

ings and acquire idiosyncratic meanings like this one just because they are stored and

used.

I followed this well-trodden road at first firm in the faith that the meanings of

productively formed words would turn out to be compositional if we could ever catch

the words at their moment of birth. But I found that road too easy and so I took the

one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference. This less traveled road follows

a Miesian method, taking the surface structure of complexwords at face value and

replacing the analogy to sentences with a very sparse nonsentential syntaxthat mirrors

this simple structure. The semantics of this sparse syntaxfor complexwords is composi-

tional, but only because it accounts for much less of the actual meaning of even newborn

words than other semantic systems attempt to cover, leaving the rest to pragmatics

(Aronoff 1980). This bifurcating treatment rests on the assumption that words have

complexmeanings precisely because neither words nor their meanings are entirely

LANGUAGE, VOLUME 83, NUMBER 4 (2007)

814

linguistic objects, but rather the bastard offspring of language and the real or imagined

world; it is this union of sparse linguistic resources with the vastness of the nonlinguistic

universe that makes all words so rich from birth. Noncompositionality, on this account,

follows from the nature of words, not from their nurture. Of course, new complex

words cannot be entirely arbitrary in meaning, because, except for Humpty Dumpy,

we use them expecting our interlocutors to understand us.

11

Some are more predictable

than others, but new complexwords are never entirely the product of language.

As James McClelland has kindly pointed out to me, on this view the meanings of words

may be compositional just in case the world that these words and their meanings intersects

with is itself a logical world. A good example is chemical terminology. It is well known

that this terminological system is compositional, but this follows directly from the fact

that the system is itself entirely determined by the scientific principles of chemistry.

Indeed, the name of any chemical compound is governed by the principles of the Inter-

divisional Committee on Terminology, Nomenclature, and Symbols (ICTNS) of the

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Not surprisingly, this terminology

can yield very long words, the longest one attested in print in English being the name

for a strain of tobacco mosaic virus: acetylseryltyrosylserylisoleucylthreonylseryl

prolylserylglutaminylphenylalanylvalylphenylalanylleucylserylserylvalyltryptophylala

nylaspartylprolylisoleucylglutamylleucylleucylasparaginylvalylcysteinylthreonylseryl

serylleucylglycylasparaginylglutaminylphenylalanylglutaminylthreonylglutaminylglu

taminylalanylarginylthreonylthreonylglutaminylvalylglutaminylglutaminylphenylalanyl

serylglutaminylvalyltryptophyllysylprolylphenylalanylprolylglutaminylserylthreonylvalylargi

nylphenylalanylprolylglycylaspartylvalyltyrosyllysylvalyltyrosylarginyltyrosylasparagi

nylalanylvalylleucylaspartylprolylleucylisoleucylthreonylalanylleucylleucylglycylthreo

nylphenylalanylaspartylthreonylarginylasparaginylarginylisoleucylisoleucylglutamylva

lylglutamylasparaginylglutaminylglutaminylserylprolylthreonylthreonylalanylglutamyl

threonylleucylaspartylalanylthreonylarginylarginylvalylaspartylaspartylalanylthreonyl

valylalanylisoleucylarginylserylalanylasparaginylisoleucylasparaginylleucylvalylaspa

raginylglutamylleucylvalylarginylglycylthreonylglycylleucyltyrosylasparaginylglutami

nylasparaginylthreonylphenylalanylglutamylserylmethionylserylglycylleucylvalyltryp

tophylthreonylserylalanylprolylalanylserine.

My point is that chemical terminology is compositional, not for linguistic reasons,

but because the terminology mirrors chemical theory, which is a logical world. But

when the world that the words reflect is not entirely logical (and few are), then neither

are the meanings of the words.

To show what motivates this bifurcating treatment of the meanings of words, I return

to one of our trio of Revolutionary words, skinner, the one that appears to have traveled

furthest from its compositional roots to arrive at this peculiar meaning. I do not attempt

11

‘There’s glory for you!’

‘I don’t know what you mean by ‘‘glory,’’ ’ Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. ‘Of course you don’t—till I tell you. I meant ‘‘there’s a

nice knock-down argument for you!’’ ’

‘But ‘‘glory’’ doesn’t mean ‘‘a nice knock-down argument,’’ ’ Alice objected.

‘When I use a word’, Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose

it to mean—neither more nor less.’

‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master—that’s all.’

Lewis Carroll, Through the looking glass

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD

815

to elucidate the meaning under consideration, whose origin is entirely opaque, but look

only at the meaning that seems to be most rooted in language and least tied to language-

external context. It quickly becomes apparent that even that simple attempt comes to

grief.

A skinner is transparently ‘one who skins’ and it is easy to derive the most common

meaning of the noun skinner from that of the verb skin via just about any syntactic or

semantic theory. So far, so good, but move one step further back to the meaning of

the verb and the going gets tough. This verb skin is derived from the noun skin, whose

Old Norse origin tells us it has been around for over a millennium. How are the two

related semantically? Here are a few of the twenty-sixsenses of the verb listed in WIII.

I have omitted all those that are apparent extensions of others.

(7)

a. To cover with or as if with skin

具fuselages and wings will be skinned

with steel . . . or titanium alloys—Werner von Braun

典

b. To heal over with skin

c. To strip, scrape, or rub off the skin, peel, rind, or other outer coverings

of: to remove a surface layer from

具huge catfish are skinned and dressed

by hand

典

d. To remove (skin or other outer covering) from an object: pull or strip off

具too late to skin out the hide that night—Corey Ford典

e. To chip, cut, or damage the surface of

具skinned his hand on the rough

rock

典

f. To outdistance or defeat in a race or contest

g. To equalize the thickness of adhesive on (a pasted or glued surface) by

placing a sheet of wastepaper over it and rapidly rubbing or pressing

h. To become covered with or as if by skin

具these inks won’t dry in the

press . . . nor will they skin in the can

典—usually used with over.

i.

To climb or descend—used with up or down

具skinned down inside ladders

from the bridge deck—K. M. Dodgson

典

j.

To pass with scant room to spare: traverse a narrow opening—used with

through or by

具the big ship barely skinned through the open draw典

Rest assured I did not choose this word because of its many senses. Truthfully, I did

not choose it at all, and the whole excursion that led to the curious incident of the

Westchester synonyms began quite by accident, during the course of a conversation

about a group the country later chose to call Hurricane Katrina evacuees, on the grounds

that the term first used, refugee, was pejorative. Such rich variety of senses is sim-

ply typical of zero-derived denominal verbs in English (henceforth zero-verbs). Clark

and Clark (1979) provide a catalog of the major categories of sense types for zero-

verbs, based on their paraphrases, which number in the dozens. A synopsis is given in

Table 1.

In the face of such a wealth of sense types, the syntactically inclined explainer has

no choice but to deny all the best Ockhamite tendencies and resort to a multiplicity of

tree-types, each with the noun or root in a different configuration. Lees would have

done so, as he did for compounds, and as have more recent scholars, notably Hale and

Keyser (1993) and their followers.

12

Even if we ignore the problem of unrecoverable

12

Incidentally, an example like skin demonstrates on its face the wrongheadedness of approaches to

conversion pairs based on roots or underspecification, in which the meanings of both the verb and the noun

are derived from some third category that is neither a verb nor a noun: the direction of the semantic relation

LANGUAGE, VOLUME 83, NUMBER 4 (2007)

816

LOCATUM VERBS

GOAL VERBS

a. on/not-on

grease

a. human roles

widow

b. in/not-in

spice

b. groups

gang up

c. at, to

poison

c. masses

heap

d. around

frame

d. shapes

loop

e. along

hedge

e. pieces

quarter

f. over

bridge

f. products

nest

g. through

tunnel

g. miscellaneous

cream

h. with

trustee

word

SOURCE VERBS

LOCATION AND DURATION VERBS

INSTRUMENT VERBS

LOCATION VERBS

a. go

bicycle

a. on/not-on

ground

b. fasten

nail

b. in/not in

lodge

c. clean

mop

c. at, to

dock

d. hit

hammer

summer

e. cut, stab

harpoon

DURATION VERBS

f. destroy

grenade

g. catch

trap

h. block

dam

i.

follow

track

j.

musical instruments

fiddle

k. kitchen utensils

ladle

l.

places

farm

m. body parts

eyeball

n. simple tools

wedge

o. complextools

mill

p. miscellaneous

ransom

AGENT AND EXPERIENCER VERBS

MISCELLANEOUS VERBS

AGENT VERBS

a. meals

lunch

a. occupations

butcher

b. crops

hay

b. special roles

referee

c. parts

wing

c. animals

parrot

d. elements

snow

witness

e. other

house/s/

EXPERIENCER VERBS

T

ABLE

1. Categories of zero-verbs from Clark & Clark 1979.

deletion that plagues these analyses, the proliferation of syntactic and semantic types

assembled under a single morphological construction is embarrassing.

But how can one unite all these types of senses? Jespersen is prescient, as he often

is. In the volume on morphology of A modern English grammar on historical principles

(1943, vol. 6), he says the following about the meanings of compounds:

Compounds express a relation between two objects or notions, but say nothing of the way in which

the relation is to be understood. That must be inferred from the context or otherwise. Theoretically,

this leaves room for a large number of different interpretations of one and the same compound . . . The

analysis of the possible sense-relations can never be exhaustive. (137–38)

The only method that has been used successfully to simultaneously avoid and explain

this choice among an infinity of senses removes both the complexity and the variance

from the linguistic to the pragmatic realm, as Jespersen suggests and as I am advocating.

Pamela Downing pioneered it in her 1977 article on English nominal compounds. As

is clearly one way, from noun to verb. The different senses of the verb are all readily traceable to the sense

of the noun, but there is no inverse relation for any sense of the verb, so that the verb must be derived from

the noun. If we start from some third point, we can’t account for the directionality. The opposite derivation,

from verb to noun, holds for instance or result nouns like hit.

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD

817

Downing puts it, echoing Jespersen: ‘Indeed, because of the important differences in

the functions served by compounds, as opposed to the sentence structures which more

or less accurately paraphrase them, attempts to characterize compounds as derived

from a limited set of such structures can only be considered misguided. A paraphrase

relationship need not imply a derivational one’ (1977:840–41). She concludes that

there are ‘no constraints on the N

Ⳮ N compounding process itself’ (1977:841). The

constraints lie instead in how people categorize and refer.

English zero-verbs show a similarly rich and varied set of interpretations, as we have

seen in the case of skin. Eve and Herb Clark come close to an account like Downing’s

for these verbs, but they confine themselves to innovations, which they call contextuals.

In my response to the Clarks (Aronoff 1980), I suggested that it is possible to account

uniformly for all zero-verbs, not just the innovations, by a conversion (rule) of the

simple form N

→ V, and that the meaning of the innovative verb always comprises

what I call an

EVALUATIVE DOMAIN

of the noun’s denotation (essentially a dimension

along which the denotation of the noun can be evaluated: a knife is good if it cuts well;

a mother is good if she does well what mothers do; a club is good for clubbing, etc.).

For most nouns or other lexical items, there is no fixed evaluative domain, so that what

the meaning of the novel zero-verb will be depends on the context of its use. Of course,

any word’s meaning will become fixed lexically with enough use and time, but that

fixing should be of no interest to a linguist. This story holds most remarkably for verbs

like boycott and lynch, which are derived from proper nouns and whose meanings are

traceable to very specific incidents in which the named person, here Boycott or Lynch,

played an important role. There is nothing else to say about the semantics of zero-

verbs. Even the notion of an evaluative domain is superfluous, since Gricean principles

dictate that the verb have something to do with the noun, no more and no less than

what needs to be said to account for the range of data. On this analysis, then, all that

the grammar of English contains is the noun-to-verb conversion.

The beauty of this kind of account is that it leaves the words largely untouched,

freeing them to vary as much as speakers need or want them to. Critics have replied

that this variance is no beauty and that people like me who advocate such a sparse

account, few though we may be, are simply irresponsible and should be purged from

the field. These critics, though, ignore the most important point about Downing’s con-

clusion and mine, which is that they are not theoretical but empirical. When we look

at the actual meanings that speakers attribute to novel compound nouns under experi-

mental conditions, as Downing did, we find that they vary in ways that are formless

and void. ‘The constraints on N

Ⳮ N compounds in English cannot be characterized

in terms of absolute limitations in the semantic or syntactic structures from which they

are derived’ (1977:840). Words have idiosyncratic meanings not just because they

are preserved in memory and society but because words categorize and refer outside

language.

I offer one more English zero-verb to buttress my point. The verb is friend, which

has been cited on and off for at least a century, but has never caught on much until

very recently. The one definition given in WIII is ‘to act as the friend of’ and WIII

cites a line from A Shropshire lad (1896):

具and I will friend you, if I may, in the dark

and cloudy day—A. E. Housman

典. In the last couple of years, though, friend has

reemerged as a common term among the myriads who use the websites friendster.com

and facebook.com, both of which crucially involve individual members maintaining

lists of ‘friends’. Though the term seems to have originated with the earlier Friendster,

I concentrate on Facebook, which began, by its own definition, as ‘an online directory

LANGUAGE, VOLUME 83, NUMBER 4 (2007)

818

that connects people through social networks at school’, because I have the best ethno-

graphic sources of data for it (three children of the right age and their friends). Facebook

was inaugurated only in late 2003, but the community of members is quite large and

active and has been the subject of articles in major media outlets. To friend someone

within the Facebook community is not to act as a friend to that person, but to invite

someone to be your Facebook friend, which you do by trying to add that person to

your list of Facebook friends. Here is how that works, according to the Facebook help

page (from late 2005).

13

You can invite anyone that you can see on the network to be your friend. Just use the ‘Search’ page

to find people you know and then click on the ‘Add to Friends’ button on the right side of the screen.

A friend request will be sent to that person. Once they confirm that they actually are friends with you,

they will show up in your friends list.

Here are some uses of friend in this sense.

14

(8)

a. Eeew! This guy from my London seminar who’s a total ASS just friended

me!

b. All these random people from high school have been friending me this

week!

c. Should I friend that dude we were talking to at 1020 last night? I don’t

want him to think I’m a stalker.

The invitation is crucial to the meaning of friend

V

, because the reciprocity of the friend

relation in Facebook is enforced by the system: your invitee is not added to your list

of friends unless he or she accepts the invitation. Oddly, if the invitee does not accept,

‘the [inviter] will not be notified. They also will not be able to send you [the invitee]

another friend request for some amount of time, so to them, it will just seem as if you

haven’t confirmed their friendship yet’. The creators of Facebook may see this as a

polite method of rejection. I find it odd, but I am not twenty years old, so I guess I

just don’t understand.

The point of all this is that the meaning of friend x cannot just be ‘act as a friend

of x’, as it clearly is in the Housman citation (note the use of the modal may there),

but the invitation, which we may think of as conative aspect, must be built into the

meaning. To friend xin this world is ‘to try to become a friend of x’ or ‘to ask xto

be one’s friend’, in the special sense of the noun friend that applies in this world. Of

course, we know why the extra predicate is part of the meaning of the verb: it is built

into the program and therefore into the social community that surrounds the program!

One could try to amend the Clarks’ list or its syntactic equivalent to allow for multipredi-

cate or aspectual meanings, but that would avoid the underlying problem, that the

meaning depends on extralinguistic factors from the very first moment of the coining

of the word, which is precisely Downing’s empirical point.

15

4. L

EXICAL ROOTS

. The lexeme-centric view of word meaning, where lexical-seman-

tic information is at least partly nonlinguistic and does not reside in morphemes, has

implications for the meanings of roots. If I am right about how lexical semantics works,

13

The verb friend never appears in official Facebook text, only among users.

14

These examples were supplied by my daughter Katy.

15

I am not denying that noncausative individual verbs can have multipredicate meaning. The verb propose

‘to make an offer of marriage’ (WIII) is similar to friend in involving an invitation. The question is whether

there is a systematic multipredicate syntactic relation between nouns and their derivative zero-verbs involving

conative or similar aspect.

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD

819

then two words can have the same root and not share much lexical meaning. There is

little relation in meaning, for example, between the name Bork and the verb bork, yet

they are as closely related morphologically as any two words can be and must share

a root, if the term

ROOT

is to have any content. What does one say then about lexical

roots, which are supposed to be the atomic meaningful units of language, if two instances

of the same root can share so little meaning? The simplest ploy is to deny the linguistic

reality of roots entirely, what my colleague Robert Hoberman calls the antirootarian

position. But there is a middle ground, where words have morphological structure

even when they are not compositionally derived, and where roots are morphologically

important entities, though not particularly characterized by lexical meaning.

4.1. L

ATIN VERB ROOTS

. In the first piece of morphological analysis I ever did (pub-

lished in Aronoff 1976), I showed that certain Latin-derived roots in English verbs

can be active morphologically even when they are obviously meaningless: each root

conditions a certain set of affixes and alternations that is peculiar to that root alone.

Some examples are given in Table 2.

WORD

-

FINAL ROOT

SAMPLE VERB

ROOT

Ⳮ ion

ROOT

Ⳮ ive

sume

resume

resumption

resumptive

mit

permit

permission

permissive

pel

repel

repulsion

repulsive

ceive

receive

reception

receptive

duce

deduce

deduction

deductive

scribe

prescribe

prescription

prescriptive

pete/peat

compete

competition

competitive

cur

recur

recursion

recursive

T

ABLE

2. Some Latinate roots in English with their alternations.

These Latinate roots in English are the historical reflexes, through a complex borrowing

process, of the corresponding verb roots in Latin. Even for Classical Latin, the alterna-

tions exhibited by at least some of these verb roots were not phonologically motivated.

But in Latin, these same roots were morphologically active in other ways too that are

independent of syntaxor semantics. Perhaps most intriguing is the role of roots in

determining whether a given verb was deponent.

The traditional Latin grammatical term

DEPONENT

is the present participle of the

Latin verb deponere ‘set aside’. Deponent verbs have set aside their normal active

forms and instead use the corresponding passive forms (except for the present participle)

in active syntactic contexts. The verb admetior ‘measure out’, for example, is transitive

and takes an accusative object, but is passive in form, because it is deponent. Similarly

for obliviscor ‘forget’ (oblitus sum omnia ‘I have forgotten everything’ [Plautus]),

scrutor ‘examine’, and several hundred other Latin verbs. There are even semideponent

verbs, which are deponent only in forms based on the perfect stem.

For some time, Xu Zheng, Frank Anshen, and I have been working on a comprehen-

sive study of Latin deponent verbs, using a database of all the main-entry deponent

verbs in the Oxford Latin dictionary, which covers the period from the first Latin

writings through the end of the second century

AD

(Xu et al. 2007). I report here on

only one small part of our research, that involving deponent roots.

We show in Xu et al. 2007, based on an exhaustive analysis of all the senses of all

deponent verbs, that neither syntaxnor semantics is the best predictor of deponency,

though both are factors. Our database contains 287 deponent verbs not derived from

another lexical category (about half the total number of deponent verbs), the great

LANGUAGE, VOLUME 83, NUMBER 4 (2007)

820

majority of them consisting of either a bare root or a root and a single prefix. The

senses of all deponent verbs are about evenly divided between transitive and intransitive

values and a given root may appear in both transitive and intransitive verbs. Of these

287 verbs not derived from another lexical category, 85 percent (244) have deponent

roots, which we define as a verb root that occurs only in deponent verbs. There are

fifty-two deponent roots, twenty-two of which occur in four or more distinct verbs.

Table 3 is a list of these roots. Thus, whether a given verb is deponent is determined

to a great extent by its root, independent of the meaning of either. In other words,

besides the alternations that have survived in English and the Romance languages,

deponent Latin verb roots have at least one other important morphological property

(their mere deponency) that is independent of either syntaxor semantics.

LATIN DEPONENT

NO

.

OF VERBS

EXAMPLE

ROOT

WITH SUCH ROOT

VERB

GLOSS

gradi

22

gradior

‘proceed’

la:b

16

la:bor

‘glide’

sequ

15

sequor

‘follow’

min

11

comminor

‘threaten’

loqu

10

loquor

‘talk’

nasc

10

nascor

‘be born’

mo:li

9

mo:lior

‘build up’

mori

9

morior

‘die’

ori

8

orior

‘rise’

tue

8

tueor

‘look at’

f(or)

7

affor

‘address’

hor(t)

7

hortor

‘encourage’

luct

7

luctor

‘wrestle’

me:ti

7

me:tior

‘measure’

fate

5

fateor

‘concede’

prec

5

precor

‘ask for’

quer

5

queror

‘regret’

apisc

4

apiscor

‘grasp’

fru

4

fruor

‘enjoy’

fung

4

fungor

‘perform’

medit

4

meditor

‘contemplate’

spic

4

conspicor

‘see’

u:t

4

u:tor

‘make use of’

T

ABLE

3. Latin deponent verb roots.

4.2. H

EBREW ROOTS

. I now turn to the role of the root in the morphology of Modern

Hebrew verbs.

16

For more than a millennium, traditional grammarians have character-

ized Semitic languages as being morphologically grounded in meaningful

ROOTS

, each

root consisting usually of three consonants, with some number of lexemes (verbs, nouns,

and adjectives) built on each root.

But not every Modern Hebrew root has a constant meaning.

17

Tables 4 and 5 each

contain a single root with an apparently constant meaning.

18

The meanings of the

16

I say

MODERN HEBREW

because the transcription in this article is of Modern Hebrew, but in fact the

patterns I discuss are largely identical in the earliest attested forms of the language. I use

BIBLICAL HEBREW

to refer to the language of the unpointed text of the Bible, dating between about 800 and 100

BC

. I use

MASORETIC HEBREW

to refer to the pointed text of the Bible, dating from about 600

AD

.

17

Earlier stages of Hebrew or related Semitic languages do not show much more regularity in this regard.

18

Even these examples are a little forced, since some of the lexical items are very infrequent, obsolete,

or even artificial. In the early days of Modern Hebrew, linguistic zealots coined numerous words that never

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD

821

ROOT

⳱

ZLP

‘sprinkle, spray, drip’

NOUNS

zelef

‘sprinkling fluid (perfume)’

zalfan

‘sprinkler’

mazlef

‘watering can, sprayer’

hazlafa

‘sprinkling’

ziluf

‘sprinkling’

zlifa

‘sprinkling’

VERBS

zalaf

‘to pour, spray, sprinkle’

zilef

‘to drip’

hizlif

‘to sprinkle’

zulaf

‘to be sprinkled’

huzlaf

‘to be sprinkled’

ADJECTIVE

mezulaf

‘sprinkled’

T

ABLE

4. Lexemes formed on the Modern Hebrew root

ZLP

.

ROOT

⳱

SKR

‘pay, rent, lease’

NOUNS

saxar

‘hire, wages, profit’

soxer

‘tenant’

saxir

‘hired laborer, employee’

sxirut

‘rent’

sxira

‘hiring, renting’

haskara

‘lease’

histakrut

‘wages, profit, renting’

maskir

‘landlord’

maskoret

‘salary’

VERBS

saxar

‘to hire, rent’

niskar

‘to be hired, rewarded, paid’

histaker

‘to earn wages, make profit’

hisker

‘to lease, let’

huskar

‘to be leased’

ADJECTIVES

saxur

‘rented’

musxar

‘let, leased’

niskar

‘hired, benefited’

T

ABLE

5. Lexemes formed on the Modern Hebrew root

SKR

.

individual nouns, verbs, and adjectives in these tables can be predicted reasonably

well if each morphological pattern is associated with its own compositional semantic

function. This is what we expect from the traditional account. Table 6, though, quickly

brings such an enterprise to grief. What do pickles (kvu+im) have to do with highways

(kvi+im)? The story of how these two words are related is quite simple. Paved roads

in early modern Palestine were macadamized: made of layers of compacted broken

stone bound together with tar or asphalt. Modern roads are still built by pressing layers,

but in a more sophisticated manner. Traditional pickling also involves pressing: what-

ever is to be pickled is immersed in brine and pressed down with a weight, but the

caught on; many of these survive in dictionaries, and only a sensitive native speaker can distinguish them

from words in everyday use.

LANGUAGE, VOLUME 83, NUMBER 4 (2007)

822

container should not be sealed. If it is, it may explode (as I know from personal experi-

ence). But pressing alone without brine does not constitute pickling. Every cook worth

his or her salt knows that beef brisket should be pressed after it is cooked and before

it is sliced, regardless of whether it is pickled (corned) or not. Modern industrial pickling

does away with pressing in various ways and not every paved road in Israel is called

a kvi+, only a highway is, so while it is clear why pickles and highways both originate

in pressing, there is nothing left of pressing in the meanings of these Hebrew words

today. One who points out their related etymologies to a native speaker of the language

is rewarded with the tolerant smile reserved for pedants, as I also know from personal

experience.

ROOT

⳱

KB+

‘press’

NOUNS

keve+

‘gangway, step, degree, pickled fruit’

kvi+

‘paved road, highway’

kvi+a

‘compression’

kiv+on

‘furnace, kiln’

maxbe+

‘press, road roller’

mixba+a

‘pickling shop’

VERBS

kava+

‘to conquer, subdue, press, pave, pickle, preserve, store, hide’

kibe+

‘to conquer, subdue, press, pave, pickle, preserve’

hixbi+

‘to subdue, subjugate’

ADJECTIVES

kavu+

‘subdued, conquered, preserved, pressed, paved’

kvu+im

‘conserves, preserves, pickles’

mexuba+

‘pressed, full’

T

ABLE

6. Lexemes formed on the Modern Hebrew root

KB+

.

The reflexresponse to problems like this is to posit an ‘underspecified’ core meaning

for the root, which is supplemented idiosyncratically in each lexical entry. It is logically

impossible to show that underspecification is wrong, but trying to find a common

meaning shared by pickles and highways brings one close to empirical emptiness and

this methodological danger recurs frequently in any Semitic language. In any case,

there is no need to find a common meaning in order to relate the two words morphologi-

cally, as I show. In fact, Hebrew verb roots can be identified on the basis of alternation

classes remarkably similar in type to those that operate on Latinate roots in English,

without reference to meaning or regular phonology. This observation is nothing new;

these alternation classes are the bane of Hebrew students.

19

First, one must know a few basics of Hebrew verb morphology. Hebrew has a set

of what are traditionally called

BINYANIM

, seven in number, often called conjugations

in the recent theoretical literature. Each binyan rigidly assigns to each cell of the verb

paradigm a stem pattern containing a prosodic shape complete with vowels. A stem

pattern may also include a prefix. The hif’il binyan, for example, has a prefix hi- or

ha-, and the pattern CCiC (e.g. higdil ‘grew’). The pi’el binyan has the stem pattern

CiCeC in the past, meCaCeC in the present, and CaCeC in the future (e.g. megadel

‘grow’). Traditionally, each binyan (like each root) is said to have a constant meaning

19

I confine my discussion to verbs, both because there are fewer verb patterns than noun patterns and

because it is easier to believe that verb roots are related semantically, so if we can talk about verb roots

without recourse to meaning, then all the more so for nouns and adjectives, whose meanings show much

greater variety.

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD

823

or syntactic structure. Some modern scholars have questioned that claim, but whether

binyanim have meaning is orthogonal to the matter at hand, which is roots.

Besides being determined by binyanim, verb forms depend on the alternation class of

their root. Root alternation classes, except for the (default) regular class, are traditionally

identified in terms of one of the consonants that occupy the three canonical root conso-

nant positions, which I call R

1

, R

2

, and R

3

.

20

The term

FULL

is used for regular roots

because they do not alternate except for more general phonological phenomena that

are not root-dependent, like spirantization (the alternation of stops and fricatives). For

example, the root alternation class R

3

h is so named because the third consonant of the

root is h; in a root of alternation class R

3

n the third consonant is n. These alternation

classes, named in this way, figure prominently in traditional Hebrew grammar.

At some point in the early history of the language, the differences in verb forms

among root alternation classes were undoubtedly predictable from the phonology of

the consonant that defined each type. R

1

n verbs, which I discuss in some detail below,

pattern the way they do because of the phonology of n in some very early stage of

Hebrew (long before the original consonantal text of the Bible or any other existing

Hebrew text was written down). The passage of time, however, made these phonological

conditions opaque, so that two verbs with identical consonants in the same position

could show different alternation patterns even in Biblical Hebrew. This differential

patterning proves that the alternation classes were no longer predictable phonologically,

even in Biblical Hebrew, but are more like verb classes of the sort found, for instance,

in Germanic languages, where the classes are defined by distinctions in ablaut and

verbs must be marked for membership in a given

STRONG

class.

21

In Hebrew, similar

sorts of idiosyncratic alternations to those of Germanic are determined by the alternation

class of a verb’s root (which also appears to be true in Germanic), a fact that gives

roots their linguistic reality.

The root alternation classes and binyanim of Semitic constitute two dimensions of

a four-dimensional matrix, the others of which are person/number/gender combination

(ten are possible) and tense (in Modern Hebrew: past, present, future, and imperative,

though the last is becoming increasingly rare). All the possible regularities of any given

individual verb form are thus exhausted by four specifications: its root class, its binyan,

its person/number/gender value, and its tense. Lest it be thought that this matrixis

trivial, a reasonably complete traditional table of verbs (Tarmon & Uval 1991) lists

235 distinct combinations of root class and binyan alone, what they call verb types, of

which only nine contain just a single root. Multiplying 235 by the ten person/number/

gender values in all of the tenses (a total of twenty-six) yields a little more than six

thousand distinct form types into which any verb form in the language must fall.

22

Not

all of these sixthousand types must be learned individually, only what alternation class

a verb root belongs to (if it is not regular) and what binyanim a root may occur in.

In this article, I look only at the roots whose R

1

is a coronal sonorant: R

1

n, R

1

y, and

R

1

l. My task is to identify the marked alternation classes that such roots belong to,

those alternation classes whose member roots must be listed (weeding out, along the

20

There are roots with more than three consonants, but these are not germane to this conversation.

21

Not even the most abstract of phonological representations could save the Hebrew system from being

morphologized. In the case of n, for instance, one would have to posit n

1

and n

2

, without any phonetic way

to distinguish them beyond the fact that they pattern differently.

22

Finkel and Stump (2007) adopt a similar approach in their computational approach to Hebrew verb

forms.

LANGUAGE, VOLUME 83, NUMBER 4 (2007)

824

way, those coronal sonorant-initial roots that do not belong to any marked class and

are hence regular). Only the class of full roots is regular. It constitutes the default class

for Hebrew roots. And just like default classes in other languages, it includes those

roots that exceptionally do not pattern with a marked class, although they meet the

criteria for membership in that class (Aronoff 1994). For example, there are two mor-

phologically distinct sets of R

1

n roots and they cannot be distinguished by their phono-

logical makeup, which means that the R

1

n roots in one set must be marked as belonging

to a marked alternation class. Because one set patterns exactly like regular full verbs,

the other set constitutes the marked alternation class. Any root that belongs to a marked

class alternation must be flagged as such, in precisely the same way that a verb is

flagged for its conjugation in a classical Indo-European language.

To a great extent, root alternation classes resemble the conjugation classes of classical

Indo-European languages more than binyanim do, even though theoretical linguists

usually call the latter conjugations. One might say that there are two dimensions to the

conjugation of a Semitic verb, the root class and the binyan. This is certainly close to

the traditional view of Hebrew grammar.

To demonstrate the validity of this claim, I show first that there are two sets of R

1

n

roots and that one set behaves just like regular roots, making the other set a marked

class of roots. I then show that there are three sets of R

1

y roots, one of which patterns

identically to the marked R

1

n alternation class, leading to the conclusion that the so-

called R

1

n alternation class contains verbs with both initial n and y (and one with initial

l), not news to traditional grammarians. In other words, the alternation class of roots

that includes marked R

1

n roots also includes roots whose R

1

is not n. This alternation

class has thus become morphological rather than phonological. One might wish to give

the alternation class formerly known as R

1

n a more general label: the class of marked

R

1

coronal sonorant roots, but the existence of a distinct class of R

1

y roots makes that

label unenlightening. The main point is that the class has become morphological, even

by the earliest attestation of Biblical Hebrew.

The two morphologically distinct sets of R

1

n roots are those in which the n is deleted

between the vowel of a prefixand R

2

, which are traditionally termed

MISSING

R

1

n roots,

and those in which the n is not deleted. The latter pattern exactly as do completely

regular roots, and thus are actually full roots, not members of a marked alternation

class, exactly as predicted generally for exceptions to marked classes (Aronoff 1994).

Originally, the difference in patterning was phonologically motivated: an n went missing

because it was assimilated to a following nonguttural R

2

consonant, which was thereby

geminated and, if a stop, consequently exempt from spirantization (realization as a

fricative).

23

The root npl, for example, when prefixed with the first-person plural imper-

fect prefix ni-, would lose its initial n, so that the actual Masoretic form was nippol

‘we (will) fall’.

24

In roots with guttural (pharyngeal or laryngeal) R

2

, the n was not

assimilated, being somehow protected by the guttural. The root nhg, for example, when

prefixed with the first-person plural imperfect prefix ni-, would not lose its initial n,

so that the actual Masoretic and Modern form is ninhag ‘we (will) drive’. The assimila-

tion of n has been unproductive in recorded history, however, so that, in a good number

of roots with a nonguttural R

2

, the R

1

n remains intact even in the assimilation context.

Whether R

1

n is missing is a property of individual verb roots, not lexemes: npl is a

23

There are no longer any geminate consonants in the language, but former geminates are still exempt

from spirantization.

24

In Modern Hebrew, the corresponding form is nipol.

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD

825

missing R

1

n root; ngd is not.

25

This is the principal empirical analytical evidence for

the linguistic reality of Hebrew roots. We even find etymologically distinct homopho-

nous roots, one of which is a missing R

1

n root, and the other not. Compare hibit ‘look’

with hinbit ‘sprout’.

26

Importantly, individual lexemes belonging to the same root do

not vary. Examples of missing R

1

n roots are given in Table 7; full R

1

n roots are

exemplified in Table 8. Individual verb forms in which the n is missing are italicized;

those in which it is phonologically eligible to be missing but is not are boldfaced.

ROOT

BINYAN

PAST

FUTURE

INFINITIVE

GLOSS

REMARKS

ntp

pa’al

nataf

yi-tof

li-tof

‘drip (intr.)’

n drops before R

2

(t)

ntp

hif’il

hi-tif

ya-tif

le-ha-tif

‘drip (tr.)’

ncl

nif’al

ni-cal* (cf.

yi-nacel

le-hi-nacel

‘arrive’

*would be nincal if n were

nixtav)

not assimilated

npl

pa’al

nafal

yi-pol

li-pol

‘fall’

npl

hif’il

hi-pil

ya-pil

le-ha-pil

‘cause to fall’

npl

huf’al

hu-pal

ju-pal

NA

‘be thrown down’

nbt

hif’il

hi-bit*

ya-bit*

le-ha-bit*

‘look’

*b would be v if n were not

assimilated

ntn

pa’al

natan

yi-ten

la-tet*

‘give’

*infinitive is irregular,

should be liten

ntn

nif’al

nitan* (cf.

yi-naten

le-hi-naten

‘be given’

*would be nintan if n were

nixtav)

not assimilated

lkxpa’al

lakax

yi-kax

la-kaxat

‘take’

only example of initial l that

behaves like missing R

1

n