Teacher Ratings of ADHD Symptoms in Ethnic Minority Students:

Bias or Behavioral Difference?

Shelley J. Hosterman and

George J. DuPaul

Lehigh University

Asha K. Jitendra

University of Minnesota

Disproportionate placement of African American and Hispanic students into disability

and special education categories may result from true behavioral and cognitive differ-

ences, bias in assessment and referral, or some combination of the two. Studies of

commonly used ADHD rating scales suggest teacher bias may contribute to placement

discrepancies. This investigation compared teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms on the

Conner’s Teacher Rating Scale—Revised Long Version (CTRS-R:L; Conners, 1997)

and the ADHD-IV: School Version (DuPaul, Power, Anastopoulous, & Reid, 1998),

with objective classroom observations from the Behavioral Observation of Students in

Schools code (BOSS; Shapiro, 2003). Participants were first through fourth grade

students (N

⫽ 172; 120 male) classified as Caucasian (n ⫽ 112) or ethnic minority (17

African American, 38 Hispanic, 5 African American and Hispanic). Contrary to

hypothesis, results showed teacher ratings of ethnic minority students were more

consistent with direct observation data than were ratings of Caucasian students.

Findings suggest teacher ratings of ethnic minority students may more accurately

reflect true behavioral levels.

Keywords:

ADHD, ethnicity, teacher ratings, direct observations, bias

African American and Hispanic students are

disproportionately diagnosed and placed into

categories of special education in the United

States (Coutinho & Oswald, 2000; Oswald,

Coutinho, Best, & Singh, 1999). Government

education data show overrepresentation of Af-

rican American students in categories of emo-

tional disturbance (ED) and mental retardation

(MR) for each year since 1968 (Donovan &

Cross, 2002; Hosp & Reschly, 2004). Among a

group of one million American students,

160,000 more African Americans students than

Caucasian students will be placed in special

education (Hosp & Reschly, 2004).

Higher rates of identification among ethic

minority students may stem from true cognitive

or behavioral differences, bias in the referral

and assessment process, or some combination

of these two. For the purposes of the current

investigation, “bias” is defined as variation in

teacher ratings of behavior based on student

ethnicity (Chang & Stanley, 2003). If teachers’

perceptions of “typical” and “atypical” behavior

vary across ethnic groups, resulting in different

appraisals or actions based on the same behav-

ior sample, then “bias” is present (Chang &

Stanley, 2003).

Teacher referrals and ratings are central de-

terminants in special education evaluations. Ev-

idence shows referral may represent one source

of placement differences as the majority of stu-

dents referred to special education are ulti-

mately classified and placed (Artiles & Trent,

1994; Ysseldyke, Vanderwood, & Shriner,

1997). Hosp and Reschly (2003) found that 132

African American and 106 Hispanic students

are referred for every 100 Caucasian students.

Studies also show that teacher tolerance is a

primary indicator for identification of behavior

problems and teachers are less tolerant of be-

haviors that are inconsistent with their cultural

expectations (Gerber & Semmel, 1984; Lam-

bert, Puig, Lyubansky, Rowan, & Winfrey,

Shelley J. Hosterman and George J. DuPaul, Department

of Education and Human Services, Lehigh University; and

Asha K. Jitendra, Department of Educational Psychology,

University of Minnesota.

The preparation of this article was supported by NIMH

Grant R01-MH62941.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed

to Shelley Hosterman, Lehigh University, Department of Ed-

ucation and Human Services, Iacocca Hall, 111 Research

Drive, Bethlehem, PA 18015. E-mail: sjh6@lehigh.edu

School Psychology Quarterly

Copyright 2008 by the American Psychological Association

2008, Vol. 23, No. 3, 418 – 435

1045-3830/08/$12.00

DOI: 10.1037/a0012668

418

2001). Because 90% of teachers in the U.S. are

Caucasian, it is important to explore the possi-

ble influence of cultural bias on identification of

behavior problems (U.S. Department of Educa-

tion, Office of Educational Research & Im-

provement, 1998).

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

is among the most common childhood disorders. In

fact, an estimated 3% to 5% of children exhibit

symptoms of ADHD (APA, 2000). Almost 50%

of children with ADHD are eventually placed in

special education programs for behavioral dis-

orders or learning disabilities (Reid, Maag,

Vasa, & Wright, 1994). Students with ADHD

are also assigned to the growing category of

“other health impaired” (National Center for

Education Statistics, 2001).

Evaluations of ADHD symptoms typically

employ a behavioral assessment approach uti-

lizing multiple methods of data collection

across settings and informants (e.g., Anastopou-

los & Shelton, 2000; Barkley, 2006). Major

components include parent and teacher inter-

views, rating scales completed by parents and

teachers, and observations of the child in mul-

tiple settings and task situations (DuPaul &

Stoner, 2003). Thus, responsible diagnosis and

placement decisions rely on a comprehensive

and complex collection of data rather than a

single source (Shapiro & Kratochwill, 2000).

Teacher ratings are a valued aspect of ADHD

assessment because they summarize extensive,

accumulated observations of child behavior

from individuals who are familiar with devel-

opmental expectations (Busse & Beaver, 2000).

These ratings contribute to diagnostic decision-

making by clarifying whether ADHD symp-

toms are inconsistent with developmental level

and associated with impairment across two or

more settings (APA, 2000). Teacher ratings of

behavior are among the most commonly used

methods in school-based assessment of ADHD

(Barkley, 2006; DuPaul & Stoner, 2003). If bias

occurs in teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms,

this may be one source of incongruity in special

education placements across ethnic groups.

Three cross-cultural studies using videotaped

vignettes of scripted ADHD symptoms and dis-

ruptive behaviors have demonstrated the influ-

ence of rater culture on perceptions of ADHD

symptoms. Mann et al. (1992) showed that Chi-

nese and Indonesian clinicians rated hyperac-

tive-disruptive behaviors more severely than

did their Japanese and American colleagues. In

a second study, American and Japanese teachers

rated student behavior more moderately than

did teachers from China, Indonesia, and Thai-

land (Meuller et al., 1995). Similarly, teachers

and student teachers from mainland China

rated videotaped samples of ADHD symp-

toms higher than did teachers from Hong

Kong and the United Kingdom (Alban-

Metcalfe, Cheng-Lai, & Ma, 2002). These

studies emphasize variation in standards for

child behavior across cultures and highlight

the influence of rater’s culture on perception

of ADHD symptoms. A teacher’s personal

history and culture may impact their view of

student behavior.

Other investigations have highlighted the in-

fluence of student ethnicity on teacher percep-

tions of behavior concerns. Stevens (1980)

found teacher ratings of both positive and neg-

ative student characteristics were more influ-

enced by student ethnicity and SES than by

observable behaviors. Results of Prieto and

Zucker (1981) showed that teachers rated a stu-

dent with symptoms of emotional disturbance

as appropriate for services more often when the

student was Mexican American than Caucasian.

Similarly, African American students described

as “difficult to teach” were rated more appro-

priate for special education referral than their

Caucasian peers, regardless of teacher ethnicity

(Bahr, Fuchs, Stecher, & Fuchs, 1991). Middle

school teachers rated students with movement

styles common in African American culture

(e.g., a nonstandard “stroll” style of walking

with a swagger and knees bent) lower in

achievement, higher in aggression, and more in

need of special education than students with

standard movement styles (Neal, McCray,

Webb-Johnson, & Bridgest, 2003). In contrast,

two recent investigations showed that neither

teacher recommendations for placement (Frey,

2002) nor rating scale reports (Cullinan &

Kauffman, 2005) for students with emotional

and behavioral disorders demonstrated bias to-

ward overrepresentation of ethnic minority stu-

dents after SES was controlled. Nonetheless,

evidence suggests student ethnicity may influ-

ence teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms.

Two studies, each examining the correspon-

dence between teacher ratings and direct obser-

vations of varied problem behaviors in cross-

cultural settings, suggested congruence between

419

TEACHER RATINGS OF ADHD IN ETHNIC MINORITY STUDENTS

teacher and student cultures as a key influence.

Puig et al. (1999) compared teacher ratings with

direct observation data in a sample of African

American students and Jamaican students of

African descent. Although Jamaican students

displayed significantly higher levels of observ-

able problem behaviors, teacher ratings of Af-

rican American students were nearly double

those of their Jamaican peers. Puig et al. sug-

gested that Caucasian teachers working in the

U.S. may have lower thresholds of tolerance for

problem behaviors in African American stu-

dents and provide exaggerated reports of these

symptoms. In a second study, direct observa-

tions showed that levels of problem and off-task

behavior in American students were nearly

twice those of Thai students, but reports of

problem behaviors from Thai teachers nearly

doubled those of American teachers (Weisz,

Chaiyasit, Weiss, Eastman, & Jackson, 1995).

Clearly, the match between student and teacher

cultures must be considered when interpreting

rating scale data.

Studies of common ADHD rating scales re-

veal patterns of overidentifying students from

certain ethic minority backgrounds. Initial re-

search in this area emerged after early versions

of scales were developed and interest recently

resurged in response to concerns about cultur-

ally fair assessment and overrepresentation.

Langsdorf, Anderson, Waechter, Madrigal, and

Juarez (1979) examined distributions of scores

on an early version of the Abbreviated Conner’s

Teacher Rating Scale (CTRS; Conners, 1973)

across a large (n

⫽ 1719) sample. Results

showed that in schools with non-Caucasian ma-

jorities, African American students were signif-

icantly more, and Mexican American students

significantly less likely to be rated hyperactive

compared to Caucasian peers. Both SES and

ethnicity had significant effects on CTRS rat-

ings, with poor African American students far-

ing the worst (Langsdorf et al., 1979). Epstein,

March, Conners, and Jackson (1998) found that

African American children were rated higher on

CTRS-R (Conners, 1997) externalizing problem

factors, including conduct disorder and hyper-

activity problems, compared to Caucasian

peers. A third study (Reid, Casat, Norton, Anas-

topoulos, & Temple, 2001) found African

American students would screen positive for

ADHD on the IOWA Conner’s (Pelham,

Milich, Murphy, & Murphy, 1989) at levels

twice those of Caucasian peers. These three

studies provide evidence of potential bias in

teacher ratings of ADHD but cannot distinguish

rater effects from true behavioral variation

across ethnic groups.

The commonly used ADHD-IV Rating

Scale-School Version (DuPaul, Power, Anasto-

poulos, & Reid, 1998) has also been examined

across ethnicity with similar results. In a large

sample of males ages 5 to 18, Reid et al. (1998)

found teachers rated African American students

higher on all symptoms relative to their Cauca-

sian peers. Results showed that screening all

students using norms based on a primarily Cau-

casian standardization sample would lead to

twice as many positive screenings in African

American students. Reid et al. (2000) found an

interaction effect for gender and ethnicity; Af-

rican American males received the most severe

and Caucasian females the least severe ratings.

One additional study (Arnold et al., 2003) found

that African American students scored signifi-

cantly higher on the Swanson, Nolan, and Pel-

ham Rating Scale-IV (SNAP-IV; Swanson,

1992) compared to their Hispanic and Cauca-

sian peers, even after controlling for SES.

The studies discussed above establish that

mean scores on common teacher rating scales of

ADHD vary across ethnic groups. However, the

possibility remains that such ratings may be

accurate reflections of behavioral variation.

Several investigators have suggested comparing

teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms with more

objective direct observations to explore the im-

pact of student ethnicity relative to true behav-

ior difference (Epstein et al., 1998; Langsdorf

et al., 1979; Reid et al., 2001, 1998). Only three

studies in the literature have used this method to

investigate the possibility of ethnic bias in

teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms.

Ramirez and Shapiro (2005) examined the

effects of both teacher and student ethnicity on

ratings of ADHD symptoms. Caucasian and

Hispanic teachers completed ADHD-IV rating

scales after viewing videotaped vignettes of stu-

dents exhibiting similar levels of overactive,

inattentive, or disruptive behaviors. Results

showed effects of teacher ethnicity, specifically

that Hispanic teachers may hold students of

their own culture to stricter standards of behav-

ior. Student ethnicity had no effect on the rat-

ings of Caucasian teachers in this analog situa-

tion. Although this study provided excellent

420

HOSTERMAN, D

U

PAUL, AND JITENDRA

controls of ethnicity and behavior, it may not

accurately represent the use of ADHD rating

scales in school settings, where teachers typi-

cally base behavioral ratings on accumulated

interaction with students rather than discrete

samples.

Working in the United Kingdom, Sonuga-

Barke, Minocha, Taylor, and Sandberg (1993)

compared teacher reports from interviews and

questionnaires with direct observations and me-

chanical data on student behavior in analog and

regular classroom settings. Teacher reported hy-

peractivity levels of Asian (parents from India,

Pakistan, or Bangladesh) students were overes-

timates as compared to objective measures of

student behavior. In fact, direct observations

showed the behavior of Asian students rated

“hyperactive” was comparable to that of En-

glish students in the control group. This study

suggests that comparisons of subjective teacher

ratings to more objective systematic observa-

tions may reveal teacher bias toward certain

ethnic groups (Sonuga-Barke et al., 1993).

The third study, Epstein et al. (2005), com-

pared teacher ratings on three common scales to

observation data of African American and Cau-

casian students. Results showed that overall,

teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms were

higher for the African American group (Epstein

et al., 2005). However, direct observation data

revealed a similar pattern, with African Amer-

ican students exhibiting higher levels of observ-

able ADHD symptoms than their Caucasian

peers (Epstein et al., 2005). Correlations of

teacher ratings and observation data were sim-

ilar for both groups. Thus, unlike Sonuga-Barke

et al. (1993), these results did not evidence bias

in teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms for stu-

dents from ethnic minority backgrounds.

Clearly, the literature examining the question

of bias in teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms

by comparing teacher rating scale data with

direct observations of classroom behavior is

both sparse and inconclusive. The purpose of

the current study was to expand this literature

by comparing teacher ratings on two commonly

used ADHD ratings scales to direct observation

data from a well-established observational code.

The study aimed to extend the work of Sonuga-

Barke et al. (1993) to a sample of American

students. Also, it extended the U.S. based work

of Epstein et al. (2005) by including a sample

with an ethnic composition more representative

of the U.S. population.

The current study aimed to answer the ques-

tion: Are teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms in

African American and Hispanic students less

consistent with objective observations than are

teacher ratings of Caucasian students? The hy-

pothesis was that teacher ratings of ADHD

symptoms would correlate more strongly with

behavioral observations for Caucasian students

than for a group comprised of African American

and Hispanic students.

Method

Participants

Sample of Larger Investigation

Participants were selected from a larger study

examining academic interventions for elemen-

tary school students with ADHD (for details,

see DuPaul, Jitendra et al., 2006). All partici-

pants met several initial inclusion criteria. Re-

cruited from schools in eastern Pennsylvania,

all students were enrolled in a first through

fourth grade, general or special education class-

room in the public school system. Participants’

families also indicated that they did not plan to

move from the area within 2 years following the

start of the study.

Students in the ADHD group met four addi-

tional inclusion criteria. Children were consid-

ered for the ADHD group if they either had a

previous ADHD diagnosis from an outside ser-

vice provider or were reported by a teacher to

exhibit significant problems with inattention,

impulsivity and/or hyperactivity. All potential

participants were then screened based on the

following criteria. All students in the ADHD

group scored at or above the 90th percentile on

one or both of the Inattention or Hyperactivity-

Impulsivity subscales of the ADHD-IV (DuPaul

et al., 1998) across both parent and teacher

ratings. Higher ratings and percentiles on the

ADHD-IV represent more severe ADHD symp-

toms. Each student also met DSM–IV (APA,

2000) criteria for one of the three ADHD sub-

types based on a parent interview with the

NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Chil-

dren-IV (DISC-IV; Shaffer, Fisher, & Lucas,

1998), administered by trained graduate stu-

dents. This interview was used to ensure that

421

TEACHER RATINGS OF ADHD IN ETHNIC MINORITY STUDENTS

students met a sufficient number of individual

symptoms to warrant diagnosis. Finally, each

child was also experiencing achievement prob-

lems in either math or reading, according to

teacher report. Inclusion in the ADHD group

was based on reports from multiple respondents

and settings. These criteria addressed symptom

severity by using stringent cut-points on the

ADHD-IV and ensuring that participants met

DSM–IV criteria for ADHD.

Students in the non-ADHD control group

were recruited from the same schools, but from

different classrooms than children in the ADHD

group. Their teachers indicated that these stu-

dents were experiencing no behavioral or aca-

demic problems. Each student in the control

group scored below the 90th percentile on all

subscales of the ADHD-IV (DuPaul et al.,

1998) and did not meet criteria for ADHD,

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), or Con-

duct Disorder (CD) based on the DISC-IV par-

ent version (Shaffer, Fisher, & Lucas, 1998).

These students were also matched to those in

the ADHD group by grade and gender.

For the purpose of the current investigation,

all Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic

participants from both the ADHD and non-

ADHD control groups of the larger study were

considered for inclusion. That is, the current

study considered students classified into both

the ADHD (n

⫽ 175) and non-ADHD control

(n

⫽ 66) groups of the larger investigation for

inclusion, working from a combined original

sample of 241 students. The sample of the

larger study represented the ethnic composition

of the geographic area and included students

classified as Caucasian (n

⫽ 146), African

American (n

⫽ 22), Hispanic (n ⫽ 64), and

other (n

⫽ 6).

Sample of Current Investigation

Using this sample, two groups were created:

a Caucasian group and an ethnic minority group

comprised of all African American and His-

panic students in the sample. Inclusion was fur-

ther limited to ensure independence of raters.

That is, if a classroom teacher had two or more

students enrolled in the larger study, one student

was randomly selected for the current investi-

gation. Inclusion was also limited by teacher

completion of behavior rating scales. For exam-

ple, data obtained from a direct observation in

math were included only if the student’s math

teacher completed the behavior ratings scales.

Because separate analyses were conducted for

reading and math, the same student could be

represented in analyses for both academic areas.

Table 1 displays demographic data for the

final sample of the current study. These data are

shown separately for the Caucasian (n

⫽ 112)

and ethnic minority (n

⫽ 60) groups. The ethnic

minority group consisted of 17 (28.3%) African

American, 38 (63.3%) Hispanic, and 5 (8.3%)

students of both African American and Hispanic

descent. The Caucasian group was 75% (n

⫽

85) male and the ethnic minority Group 90%

male (n

⫽ 54). At enrollment, 21% of partici-

pants were taking psychotropic medication (pri-

marily psychostimulants). Based on results of

the DISC-IV (Shaffer et al., 1998), 17.7% of

participants met criteria for ADHD: Inattentive

subtype, 6.9% for ADHD Hyperactive-Impul-

sive subtype, 46% for the combined subtype,

and the remainder were control students.

Among the 171 students included in the reading

analyses, 54 (31.6%) displayed academic difficul-

ties in reading only, 35 experienced difficulty in

both reading and math (20.4%), and 82 (48%)

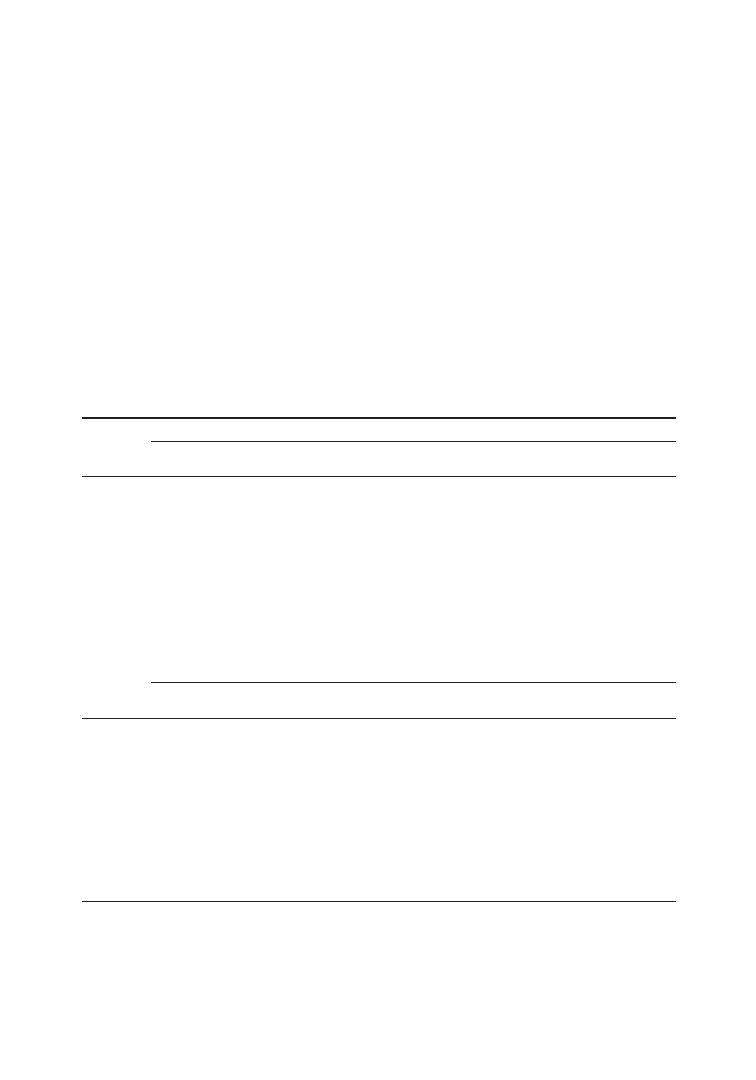

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics of the Caucasian and Ethnic Minority Groups

Measure

Group

Caucasian (n

⫽ 112)

Ethnic minority (n

⫽ 60)

t(170) or

2

(1)

p

Age (in years)

8.48

a

(1.25)

b

8.49 (1.13)

⫺.052

0.959

Male (%)

75

90

5.543

.019

ⴱ

SES

59.71 (22.62)

43.62 (26.90)

⫺2.596

.010

ⴱ

Group (% ADHD group)

69.6

76.7

.958

.328

Note.

SES

⫽ social economic status determined by highest Hollingshead parent occupation; ADHD ⫽ attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder.

a

Mean.

b

Standard deviation.

ⴱ

p

⬍ .05.

422

HOSTERMAN, D

U

PAUL, AND JITENDRA

displayed difficulty in either math alone or in

neither academic area. Among the 167 students

included in the math analyses, 26 (15.6%) had

difficulties in math only, 35 (21.0%) had diffi-

culties in both reading and math, and 106

(63.5%) had difficulties either exclusively in

reading or in neither academic area.

Among students receiving academic inter-

ventions, teacher ratings of academic perfor-

mance in reading and mathematics on the Aca-

demic Competence Evaluation Scales (ACES;

DiPerna & Elliott, 2000) shared significant cor-

relations with student performance on reading

and math subtests of the Woodcock-Johnson III

Test of Achievement (WJ-III; Woodcock,

McGrew, & Mather, 2001). Teacher ratings of

student reading ability on the ACES accounted

for 19.8% of variance (r

⫽ .445, p ⬍ .001) in

standard scores on the WJ-III Reading Fluency

subscale and 22.8% of variance (r

⫽ .477, p ⬍

.001) in standard scores on the WJ-III Passage

Comprehension subscale. Teacher ratings of

mathematics ability on the ACES accounted

for 11.4% of variance (r

⫽ .338, p ⫽ .003) in

standard scores on the WJ-III Calculation

subtest and 10.5% of variance (r

⫽ .324, p ⫽

.005) in standard scores on the Math Fluency

subtest. At baseline, students in the math inter-

vention group earned standard scores in the low

average range on the Calculation (M

⫽ 92.15,

SD

⫽ 13.81) and Math Fluency (M ⫽ 86.66,

SD

⫽ 13.39) subtests of the WJ-III. Students

receiving reading intervention scored in the low

average range on the Reading Fluency

(M

⫽ 81.33, SD ⫽ 21.04) and Reading Com-

prehension (M

⫽ 88.30, SD ⫽ 11.56) subtests

of the WJ-III. Independent sample t tests re-

vealed no significant differences between the

Caucasian and ethnic minority groups on WJ-III

scores or ACES ratings.

Teacher demographic data were only avail-

able for teachers of students in the ADHD group

of the larger study (70% of included cases). Of

these teachers (n

⫽ 120), 92% were fe-

male, 95.5% were Caucasian, 90.9% taught in

regular education classrooms, and 47.7% pos-

sessed a master’s degree. Teachers aver-

aged 10.90 (SD

⫽ 9.13) years of experience.

Demographics of teachers with students in the

control group are expected to be similar, given

that they were teaching in the same school settings

as those in the ADHD group. Because teacher

referral and ratings were part of the screening

process, teachers were not blind to group mem-

bership or purpose of the larger study. However,

teachers were unaware that questions related to

student ethnicity would be investigated.

Procedures

Data for the current investigation came from

the initial (pretreatment) collection phase of the

larger study. Trained graduate students col-

lected direct observation data for each partici-

pant during 15 minutes of both a regular reading

and regular math class. All participants were

observed in both reading and math, regardless

of academic performance. Observations typi-

cally occurred during January or February. Ob-

servers were kept blind to group membership

(ADHD vs. non-ADHD control) in the larger

study. A significant portion of all observations

were collected by two raters simultaneously to

monitor interobserver agreement (IOA). Occur-

rence, nonoccurrence, and overall IOA values

were calculated by dividing the number of

agreements by the sum of the number of agree-

ments plus the number of disagreements, and

multiplying this value by 100%. Kappa values

were calculated to examine the level of agree-

ment beyond chance.

In math, IOA data were available for 27.5% of

observations. Reported in the order of occurrence,

nonoccurrence, total, and kappa, IOA values for

each observational code in math were as follows:

Active Engaged Time (0.95, 0.96, 0.98, 0.95),

Passive Engaged Time (0.94, 0.96, 0.98, 0.94),

Off-Task Motor (0.91, 0.97, 0.98, 0.93), Off-

Task Verbal (0.88, 0.99, 0.99, 0.90), and Off-

Task Passive (0.90, 0.99, 0.99, 0.93). For read-

ing observations, paired IOA observations were

collected for 31% of all observations. IOA val-

ues for each code in reading were as follows:

Active Engaged Time (0.95, 0.98, 0.98, 0.96),

Passive Engaged Time (0.93, 0.94, 0.97, 0.93),

Off-Task Motor (0.89, 0.98, 0.98, 0.92), Off-

Task Verbal (0.89, 0.99, 0.99, 0.91), and Off-

Task Passive (0.85, 0.99, 0.99, 0.89).

Each student’s teacher also completed the

two behavior rating scales detailed in the

measures section. Teachers did not receive

explicit training on completion of rating

scales but were provided with a contact num-

ber for any questions or clarifications. It was

expected that teachers would appropriately

follow the standardized written instructions

423

TEACHER RATINGS OF ADHD IN ETHNIC MINORITY STUDENTS

on each scale. Forms were given to teachers

on the day of the direct observation with

instructions to return ratings promptly. How-

ever, the large sample size and geographic

area of the study impacted the latency be-

tween observations and return of rating

scales. Scales were returned at teacher con-

venience or after a reminder call but were

typically received within 4 to 8 weeks of the

observation.

Measures

SES

SES was measured using the parental occu-

pation portion of the 4-factor index of social

status (Hollingshead, 1976), a common measure

of SES. This measure collects participant gen-

erated, open-ended descriptions of each parent’s

occupation. Occupations were translated into

values between 0 and 90, where higher numbers

indicate more financially lucrative occupations

and a higher overall level of SES. For the pur-

pose of the current study, SES was represented

by selecting the parental occupation (e.g., either

mother or father) with the highest value on the

Hollingshead list. The full range of scores rep-

resenting parental occupation (rather than col-

lapsed categories of similar occupations) was

used to capture the complete range of variability

in SES.

CTRS-R:L

The CTRS-R:L (Conners, 1997) is a common

teacher rating assessment of behavior problems

in the classroom. The scale has two indexes,

DSM–IV: Inattentive and DSM–IV: Hyperac-

tive-Impulsive, each comprised of 9, 4-point

Likert style items. High scores on each index

correspond with DSM–IV diagnostic criteria for

the ADHD subtypes. The DSM–IV: Inattentive

Index has internal consistency from 0.87 to 0.96

across age ranges and gender, and test–retest

reliability (over 6 to 8 weeks) of 0.70. For the

DSM–IV: Hyperactive-Impulsive Index, inter-

nal consistency is between 0.82 and 0.95, and

test–retest reliability (over 6 to 8 weeks) is 0.47

(Conners). The CTRS-R:L provides T scores

based on age and gender.

ADHD-IV School Version

The ADHD-IV School Version (DuPaul et

al., 1998) is adapted from the ADHD symptom

list specified in the DSM–IV (APA, 2000) and

consists of 18, 4-point Likert style items. The

two, 9-item subscales, Inattention and Hyperac-

tivity-Impulsivity, correspond to DSM–IV diag-

nostic categories. Each subscale has excellent

psychometric properties. The Inattention scale

has an internal consistency coefficient of 0.96

and a 4-week test–retest reliability of 0.89. The

Hyperactivity-Impulsivity scale has an internal

consistency coefficient of 0.88 and a 4-week

test–retest reliability of 0.88. The ADHD-IV

does not provide T scores, thus raw scores were

used in this study.

Behavioral Observation System for

Schools (BOSS)

The BOSS (Shapiro, 2003) provides direct

observations of behavioral symptoms of ADHD

in the classroom setting. Observations are seg-

mented into 15-sec intervals and four randomly

selected classroom peers provide periodic com-

parison data. Five BOSS behavior codes were

used for the current study: Active Engaged Time

(AET), Passive Engaged Time (PET), Off Task

Motor (OFT-M), Off Task Verbal (OFT-V), and

Off Task Passive (OFT-P). Two of the behaviors,

AET and PET, are recorded through momentary

time sampling. The remaining three codes are

observed by partial interval recording. Each be-

havior is reported by the percentage of intervals in

which it is observed.

Data Analyses

Chi-square tests and independent samples

t tests were conducted on key demographic vari-

ables (gender, SES, age) to uncover any be-

tween group differences. Any statistically sig-

nificant differences in these variables across

groups were then accounted for by treating the

variable as a covariate in the final analyses.

Separate analyses were computed with data

from reading class and math class. Thus, each of

the analyses described below was conducted

separately for each of the two academic areas.

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated

between the hyperactivity-impulsive indexes of

both the CTRS-R:L (Conners, 1997) and the

424

HOSTERMAN, D

U

PAUL, AND JITENDRA

ADHD-IV School version (DuPaul et al., 1998)

and the Off-Task Motor and Off-Task Verbal

behaviors off the BOSS (Shapiro, 2003). A sec-

ond set of Pearson correlation coefficients was

computed between the inattentive indexes of

both the CTRS-R:L and the ADHD-IV School

version and each of the following BOSS codes:

Active Engaged Time, Passive Engaged Time,

and Off-Task Passive.

In order to obtain power of 0.80 for a large

effect size (assuming an alpha level of 0.05) in

the selected data analyses, each group (Cauca-

sian and ethnic minority) must contain 33 stu-

dents (n

⫽ 66). Thus, the current sample was

sufficient to detect large effects.

Finally, comparisons of corresponding corre-

lation coefficients from the Caucasian and eth-

nic minority groups were made to determine if

accuracy in teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms

differed based on student ethnicity. To make

this comparison, all correlation coefficients

were first transformed with a Fisher’s z

⬘ Trans-

formation (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). Values for

Fisher’s r to z

⬘ transformation were obtained

directly from a standard table for this conver-

sion (Appendix Table B; Cohen & Cohen,

1983). With these z

⬘ values, the normal curve

deviate was computed using formula 2.8.5 from

Cohen and Cohen. The normal curve deviate

provides a test of the significance of the differ-

ence between correlation coefficients obtained

on two independent samples (Cohen & Cohen,

1983). The generated z-scores were then eval-

uated for significance using a Standard Normal

Distribution table (e.g., Appendix Table C.; Co-

hen & Cohen, 1983). Values meeting the two-

tailed

␣ ⫽ .05 criteria were considered signifi-

cant differences.

In addition to evaluating statistically signifi-

cant difference, effect sizes for differences in

corresponding correlation coefficients were also

computed as indicated in Cohen (1988). That is,

the effect size value of q

⫽ z

1

⫺ z

2

, where z

n

is

the Fisher’s z

⬘ transformation of the relevant

correlation coefficient, was used. Table 4.2.2

was used to covert each r to z

⬘ via Fisher’s z⬘

Transformation. Next, the absolute difference

(q) between each corresponding pair of z

⬘ val-

ues was compared against Cohen’s standards

for small (q

⫽ .10), medium (q ⫽ .30), and

large (q

⫽ .50) effect sizes.

Results

Demographic Comparisons

Results of chi-square tests and independent

samples t test comparisons revealed statistically

significant differences in both gender and SES

between the Caucasian and ethnic minority

groups. The ethnic minority group contained a

significantly higher proportion of male students,

2

(1)

⫽ 5.543, p ⫽ .019, than did the Caucasian

group. Students in the Caucasian group

(M

⫽ 59.71) came from households with sig-

nificantly higher levels of SES, t(170)

⫽

⫺2.596, p ⫽ .01, as compared to students in the

ethnic minority group (M

⫽ 43.62). However,

the two groups were equivalent in both age,

t(170)

⫽ ⫺.052, p ⫽ .959, and proportions of

students belonging to the ADHD and control

groups of the larger study,

2

(1)

⫽ .958, p ⫽

.328. Significant differences between groups

were addressed using covariates and T scores

during later analyses.

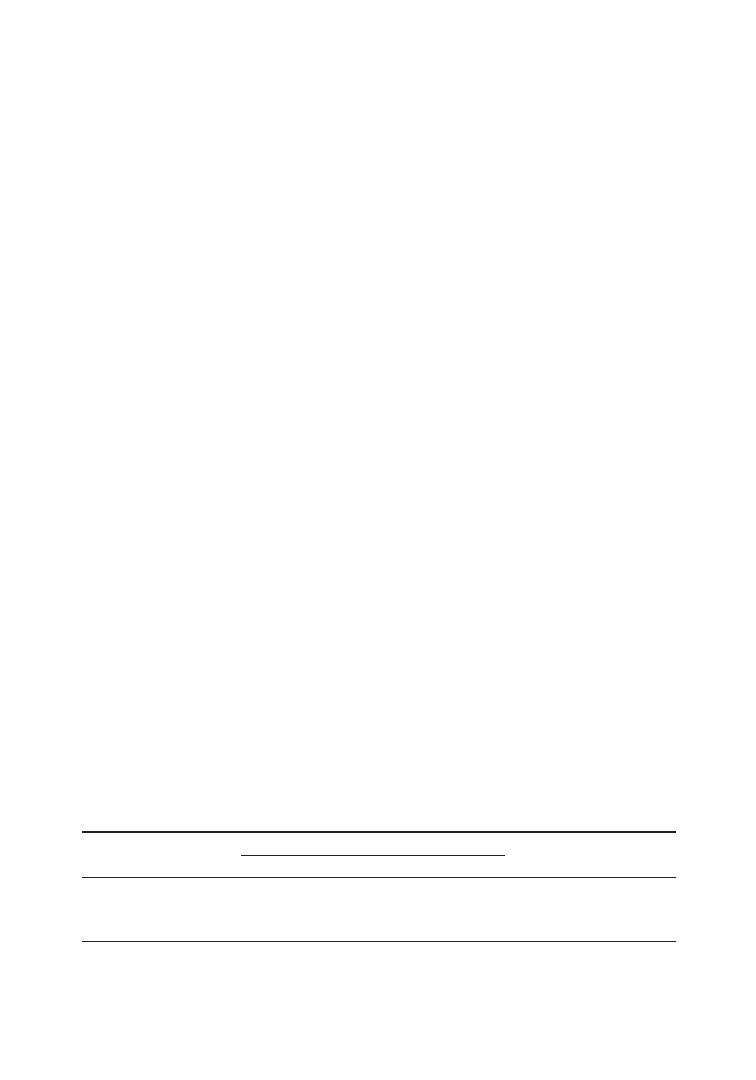

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for all indicators are

summarized in Table 2 along with t test com-

parisons between the Caucasian and ethnic mi-

nority groups. Only one statistically significant

between-groups difference occurred in direct

observation (BOSS) data. Specifically, com-

pared to students in the Caucasian group, stu-

dents in the ethnic minority group displayed

significantly higher levels of off-task verbal be-

havior during direct observations in both read-

ing, t(169)

⫽ ⫺2.818, p ⫽ .006, and math,

t(166)

⫽ ⫺2.28, p ⫽ .025, classes. Levels of the

remaining direct observation behaviors were

equivalent across groups in both reading and

math settings.

Values on one of the four teacher rating

scale indicators differed significantly between

groups. Teacher ratings on the ADHD-IV Hy-

peractive-Impulsive Index were significantly

higher for students in the ethnic minority

group in both reading, t(155)

⫽ ⫺2.368, p ⫽

.019, and math, t(153)

⫽ ⫺2.177, p ⫽ .031.

No significant differences between groups

were uncovered on the three remaining

teacher indicators in either reading or math.

425

TEACHER RATINGS OF ADHD IN ETHNIC MINORITY STUDENTS

Table

2

Descriptive

and

Comparison

Statistics

Across

Groups

Measure

Reading

Math

BOSS

data

(%

intervals)

Caucasian

Ethnic

minority

t(169)

p

Caucasian

Ethnic

minority

t(166)

p

OFT-M

15.1%

a

(16.0)

b

17.5%

(16.9)

⫺

.922

.358

19.7%

(19.1)

20.7%

(17.6)

⫺

.338

.736

OFT-V

5.0%

(7.2)

9.4%

(10.9)

⫺

2.818

.006

ⴱ

6.2%

(8.6)

10.2%

(11.9)

⫺

2.28

.025

ⴱ

OFT-P

7.4%

(8.4)

7.2%

(8.0)

.157

.875

7.7%

(8.2)

6.9%

(7.4)

.656

.513

AET

26.6%

(16.1)

24.9%

(18.9)

.624

.533

28.5%

(17.2)

29.9%

(14.7)

⫺

.274

.785

PET

49.8%

(19.3)

45.9%

(23.1)

1.106

.271

44.0%

(20.2)

38.8%

(18.7)

1.612

.109

Reading

Math

Teacher

rating

scale

data

Caucasian

Ethnic

minority

t(155)

p

Caucasian

Ethnic

minority

t(153)

p

CTRS:Hyperactive-Impulsive

59.80

c

(14.06)

63.56

(14.26)

⫺

1.589

.114

59.66

(14.07)

63.23

(14.19)

⫺

1.501

.135

ADHD

⫺

IV:Hyperactive-Impulsive

11.03

d

(9.01)

14.75

(9.91)

⫺

2.368

.019

ⴱ

11.06

(9.08)

14.52

(9.86)

⫺

2.177

.031

ⴱ

CTRS:Inattentive

61.79

c

(13.96)

61.83

(12.24)

⫺

.019

.985

61.55

(13.97)

61.58

(12.22)

⫺

.015

.988

ADHD

⫺

IV:Inattentive

15.28

d

(10.30)

16.62

(9.60)

⫺

.791

.430

15.23

(10.34)

16.42

(9.58)

⫺

.693

.489

Note.

BOSS

⫽

behavioral

observation

of

students

in

the

schools

code;

OFT-M

⫽

off-task

motor

behavior;

OFT-V

⫽

off-task

verbal

behavior;

OFT-P

⫽

off-task

passive

behavior;

AET

⫽

active

engaged

time;

PET

⫽

passive

engaged

time;

CTRS

⫽

Conners

Teacher

Rating

Scale

Revised:

Long

Form;

ADHD-IV

⫽

ADHD-IV

School

Version.

a

Mean.

b

Standard

deviation.

c

T-score.

d

Raw

score.

ⴱ

p

⬍

.05.

426

HOSTERMAN, D

U

PAUL, AND JITENDRA

Intercorrelations Between Direct

Observation Data and Teacher Ratings

Table 3 displays Pearson correlation coef-

ficients between each direct observation be-

havior and the corresponding teacher rating

scale indicators. Correlations are presented

separately by group and academic subject.

Because both gender and SES differed signif-

icantly between the Caucasian and ethnic mi-

nority groups, it was necessary to control for

these two variables in all correlations. For

CTRS-R:L indicators, T score values (ad-

dressing gender) were used within partial cor-

relations controlling for SES. Because T

scores are not available for the ADHD-IV,

raw scores were used within partial correla-

tions controlling for both SES and gender.

Intercorrelations in Reading Data

Results indicated several statistically signifi-

cant associations between direct observations in

reading and teacher ratings of ADHD symp-

toms. For the Caucasian group, off-task motor

behavior accounted for 7.6% of variance on the

CTRS-R:L DSM–IV: Hyperactive-Impulsive in-

dex (r

⫽ .276, p ⫽ .006) and 12.7% of variance

Table 3

Intercorrelations Between Observed Behaviors and Teacher Rating Indexes

Reading

CTRS: Hyperactive-

Impulsive

a

ADHD-IV: Hyperactive-

Impulsive

b

CTRS: Inattentive

a

ADHD-IV: Inattentive

b

Caucasian students (n

⫽ 98)

OFT-M

.276

ⴱ

.356

ⴱⴱ

—

—

OFT-V

.092

.111

—

—

AET

—

—

.014

.000

PET

—

—

⫺.271

ⴱ

⫺.254

ⴱ

OFT-P

—

—

.246

ⴱ

.266

ⴱ

Ethnic minority students (n

⫽ 43)

OFT-M

.438

ⴱⴱ

.434

ⴱ

—

—

OFT-V

.231

.237

—

—

AET

—

—

⫺.330

ⴱ

⫺.350

ⴱ

PET

—

—

.055

.043

OFT-P

—

—

.252

.300

Math

CTRS: Hyperactive-

Impulsive

ADHD-IV: Hyperactive-

Impulsive

CTRS: Inattentive

ADHD-IV: Inattentive

Caucasian students (n

⫽ 99)

OFT-M

.254

ⴱ

.293

ⴱⴱ

—

—

OFT-V

.068

.108

—

—

AET

—

—

⫺.099

⫺.114

PET

—

—

⫺.121

⫺.077

OFT-P

—

—

.172

.208

ⴱ

Ethnic minority students (n

⫽ 43)

OFT-M

.413

ⴱ

.491

ⴱⴱ

—

—

OFT-V

.470

ⴱⴱ

.556

ⴱⴱ

—

—

AET

—

—

⫺.219

⫺.267

PET

—

—

⫺.390

ⴱ

⫺.462

ⴱⴱ

OFT-P

—

—

.383

ⴱ

.399

ⴱ

Note.

BOSS

⫽ behavioral observation of students in the schools code; OFT-M ⫽ off-task motor behavior; OFT-V ⫽

off-task verbal behavior; OFT-P

⫽ off-task passive behavior; AET ⫽ active engaged time; PET ⫽ passive engaged time;

CTRS

⫽ Conners Teacher Rating Scale Revised: Long Form; ADHD-IV ⫽ ADHD-IV School Version; ADHD-IV ⫽

ADHD-IV School Version.

a

Partial correlations controlling for SES and using T-scores on CTRS.

b

Partial correlations

controlling for SES and gender and using raw scores on ADHD-IV.

ⴱ

p

⬍ .05;

ⴱⴱ

p

⬍ .005.

427

TEACHER RATINGS OF ADHD IN ETHNIC MINORITY STUDENTS

on the ADHD-IV Hyperactive-Impulsive index

(r

⫽ .356, p ⬍ .001). The same correlations

were also significant in the ethnic minority

group, with off-task motor behavior accounting

for 19.2% of variance in CTRS-R:L DSM–IV:

Hyperactive-Impulsive ratings (r

⫽ .438, p ⫽

.004) and 18.8% of variance in ratings on the

ADHD-IV Hyperactive-Impulsive index (r

⫽

.434, p

⫽ .005).

In contrast, teacher ratings of Inattentive

symptoms related to distinct sets of direct

observation behaviors for each of the two

groups. For the Caucasian group, passive en-

gaged time (r

⫽ ⫺.271, p ⫽ .007) accounted

for 7.3% of variance in the CTRS-R:L DSM–

IV: Inattentive scale, and off-task passive be-

havior (r

⫽ .246, p ⫽ .015) accounted for 6%

of the variance in this scale. Similarly, pas-

sive engaged time accounted for 6.5% of the

variance in ratings on the ADHD-IV Inatten-

tive scale (r

⫽ ⫺.254, p ⫽ .013) and off-task

passive behavior accounted for 7% of the

variance in this scale (r

⫽ .266, p ⫽ .009) for

the Caucasian group.

None of these associations were significant

in the ethnic minority group. For this group,

active engaged time was the only variable

significantly associated with ratings of Inat-

tentive behavior. Active engaged time ac-

counted for 10.9% of variance in teacher rat-

ings on the CTRS-R:L DSM–IV: Inattentive

scale (r

⫽ ⫺.330, p ⫽ .033) and 12.3% of

variance in ratings on the ADHD-IV Inatten-

tive scale (r

⫽ ⫺.350, p ⫽ .025).

Intercorrelations in Math Data

In math analyses, a greater proportion of the

hypothesized correlations were statistically signif-

icant for the ethnic minority group as compared to

the Caucasian group. Only 3 of the 10 hypothe-

sized associations were significant in the latter

group. As in the reading analyses, off-task motor

behavior was significantly correlated with teacher

ratings of hyperactive behavior in both groups.

For the Caucasian group, off task motor behavior

accounted for 6.5% of variance on the CTRS-R:L

DSM–IV: Hyperactive-Impulsive scale (r

⫽ .254,

p

⫽ .011) and 8.6% of variance on the ADHD-IV

Hyperactive-Impulsive scale (r

⫽ .293, p ⫽ .004).

Only one additional correlation was significant for

the Caucasian group. Specifically, off-task passive

behavior accounted for 4.3% of variance in the

ADHD-IV Inattentive scale (r

⫽ .208, p ⫽ .043).

In the ethnic minority group, 8 of the 10

hypothesized correlations between direct obser-

vation data and teacher ratings were significant.

Off task motor behavior accounted for 17.1% of

variance on the CTRS-R:L DSM–IV: Hyperac-

tive-Impulsive scale (r

⫽ .413, p ⫽ .007)

and 24.1% of variance on the ADHD-IV Hy-

peractive-Impulsive scale (r

⫽ .491, p ⫽ .001).

Off-task verbal behavior was also significantly

correlated with these scales, accounting

for 22.1% of variance on the CTRS-R:L DSM–

IV: Hyperactive-Impulsive scale (r

⫽ .470, p ⫽

.002) and 30.9% of variance on the ADHD-IV

Hyperactive-Impulsive scale (r

⫽ .556, p ⬍

.001).

Both passive engaged time and off-task

passive time were significantly correlated

with teacher ratings of Inattentive behavior in

the ethnic minority group. Passive engaged

time accounted for 15.2% of variance on the

CTRS-R:L DSM–IV: Inattentive scale (r

⫽

⫺.390, p ⫽ .011) and 21.3% of variance on

the ADHD-IV Inattentive scale (r

⫽ ⫺.462,

p

⫽ .002). Finally, for the ethnic minority

group, off-task passive behavior was signifi-

cantly correlated with the CTRS-R:L DSM–

IV: Inattentive scale (r

⫽ .383, p ⫽ .012) and

the ADHD-IV Inattentive scale (r

⫽ .399,

p

⫽ .01) accounting for 14.7% and 15.9% of

variance in the two ratings respectively.

Differences in Strength of Correlations

Between Groups

The strength of corresponding correlation co-

efficients from the Caucasian and ethnic minor-

ity groups were compared using both tests of

statistical significant and effect sizes. For statis-

tical comparisons, an online calculator (Univer-

sity of Amsterdam Faculty of Humanities, n.d.),

which automatically completes the transforma-

tions and comparisons detailed in the methods

section, was used to make these comparisons.

Results revealed several pairs of correlations

that differed significantly between the Cauca-

sian and ethnic minority groups.

In math, the positive correlation between off-

task verbal behavior and the CTRS-R:L DSM–

IV: Hyperactive-Impulsive scale was signifi-

cantly higher ( p

⫽ .02) for the ethnic minority

group (r

⫽ .470) as compared to the Caucasian

428

HOSTERMAN, D

U

PAUL, AND JITENDRA

group (r

⫽ .068). Similarly, correlations be-

tween off-task verbal behavior and the

ADHD-IV Hyperactive-Impulsive scale were

significantly higher ( p

⫽ .009) in the ethnic

minority group (r

⫽ .556) than the Caucasian

group (r

⫽ .108). Finally, negative correlations

between passive engaged time and the

ADHD-IV Inattentive scale were significantly

larger ( p

⫽ .03) for the ethnic minority (r ⫽

⫺.462) group when compared to the Caucasian

group (r

⫽ ⫺.077). Other correlation pairs

showed a similar (but nonsignificant) pattern

between groups in the math analyses. In fact,

the magnitude of all 10 hypothesized correla-

tions of direct observation behavior and teacher

ratings in math was greater in the ethnic minor-

ity group as compared to the Caucasian group.

However, none of these differences were statis-

tically significant. In reading analyses, compar-

isons revealed no statistically significant differ-

ences in corresponding correlations between the

two groups.

Effect sizes were computed to measure the

magnitude of difference in corresponding correla-

tions between the ethnic minority and Caucasian

groups. Effect sizes q

⫽ z

1

⫺ z

2

were computed

by subtracting the Fisher’s z

⬘ transformation for

the Caucasian group (z

2

) from the corresponding

value for the ethnic minority group (z

1

). Thus, a

positive effect size indicates a more positive asso-

ciation between two variables within the ethnic

minority group as compared to the Caucasian

group. Similarly, a negative q value indicates a

stronger negative correlation in the ethnic minor-

ity group relative to the Caucasian group.

In reading, three medium (

兩q兩 ⱖ .30) effects

were observed. Medium effect sizes for ethnic-

ity were found when comparing the strength of

correlations between active engaged time and

both the CTRS-R:L: Inattentive subscale (q

⫽

⫺.353) and ADHD-IV: Inattentive subscale

(q

⫽ ⫺.365). Significant negative correlations

between active engaged behavior and ratings

of inattention were observed in the ethnic minority

group (r

⫽ ⫺.33 to ⫺.35), but corresponding

correlations for Caucasian students were near zero

(r

⫽ 0 to .014). A medium effect (q ⫽ .337) for

ethnicity was also found between correlations of

passive engaged time and the CTRS-R:L Inatten-

tive subscale. That is, passive engaged behaviors

shared a significant negative correlation with rat-

ings of inattention for Caucasian students (r

⫽

⫺.271) but were not significantly correlated (r ⫽

.055) with teacher ratings on the CTRS-R:L: In-

attentive subscale for ethnic minority students.

Effect sizes for the remaining reading compari-

sons were either small or negligible.

In math, a large effect size (q

⫽ .523) for

ethnicity was found for the difference in mag-

nitude of correlations between off-task verbal

behavior and the CTRS-R:L: Hyperactive-

Impulsive scale. These variables shared a sig-

nificant positive correlation (r

⫽ .470) for eth-

nic minority students, but were not significantly

correlated (r

⫽ .068) for Caucasian students.

Similarly, a medium effect size (q

⫽ .44) for

ethnicity emerged in comparisons of correla-

tions between off-task verbal behavior and rat-

ings on the ADHD-IV: Hyperactive-Impulsive

scale between the ethnic minority (r

⫽ .47) and

Caucasian (r

⫽ .068) groups. Comparisons of

correlations between both active engaged and

passive engaged time and the ADHD-IV: Inat-

tentive subscale revealed a medium effect sizes

(q

⫽ ⫺.387 and q ⫽ ⫺.427) for ethnicity with

significant negative correlations for ethnic mi-

nority students (r

⫽ ⫺.267 and r ⫽ ⫺.462)

compared to nonsignificant correlations for

Caucasian students (r

⫽ ⫺.114 and r ⫽ ⫺.077).

Finally, a medium effect (q

⫽ ⫺.291) for eth-

nicity was observed when the magnitude of

correlations between passive engaged time and

the CTRS-R:L: Inattentive subscale was com-

pared across ethnic minority (r

⫽ ⫺.39) and

Caucasian (r

⫽ ⫺.077) groups.

1

Discussion

The current study explored how associa-

tions between teacher ratings of ADHD

symptoms and direct behavioral observations

differ in ethnic minority and Caucasian stu-

dent groups. Results showed significant vari-

ation in this association across student ethnic-

ity. However, the influence of student ethnicity

was contrary to prediction. Teacher ratings re-

flecting ADHD symptoms and on-task behavior

1

Effect size data for magnitude of differences in corre-

lations between individual ethnic groups (e.g., Caucasian,

Hispanic, and African American) were computed as post

hoc analyses. Results were similar to those of the planned

analyses. That is, correlations between observational data and

teacher ratings were stronger in both African-American and

Hispanic sub-samples relative to the Caucasian sample.

Results of these analyses did not change the general con-

clusions of this investigation.

429

TEACHER RATINGS OF ADHD IN ETHNIC MINORITY STUDENTS

in ethnic minority students were more consistent

with direct observation data than were ratings of

Caucasian students. These results suggest

teacher ratings of both hyperactive-impulsive

and inattentive symptoms may more accurately

reflect directly observable behaviors in ethnic

minority students as opposed to Caucasian stu-

dents. It appears teacher reports on the CTRS-

R:L and ADHD-IV may be more sensitive to

“true” behavior levels of ethnic minority stu-

dents than those of their Caucasian peers. Prior

studies in this area have focused on issues of

true behavioral difference, influence of student

ethnicity, rater effects, and instrument bias.

These four concepts will guide discussion and

explanation of the current results.

Observable Behavioral Difference

Comparison of teacher ratings must consider

the possibility of true behavioral difference. Ep-

stein et al. (2005) found teachers’ elevated rat-

ings of ADHD symptoms in African American

students were accurate reflections of directly

observed behavior differences. This earlier

study used an ADHD composite code combin-

ing verbal, motor, and inattentive behaviors,

which did not permit examination of specific

behaviors that might underlie group differences.

In the current study, comparisons of more spe-

cific direct observation data revealed only one

statistically significant difference. That is, eth-

nic minority students exhibited higher levels of

off-task verbal behavior in both reading and

math. Results of the current study must consider

whether variations in teacher ratings reflect this

difference in observed verbal behavior.

Student Ethnicity

Prior investigations examining the influence

of student ethnicity on teacher ratings of ADHD

symptoms have produced mixed conclusions.

Sonuga-Barke et al. (1993) found teacher rat-

ings of ADHD symptoms in minority (“Asian”

students in the U.K.) students overestimated

true levels of behavior and provided evidence of

teacher bias. Similarly, Puig et al. (1999)

showed teacher ratings of overall problem be-

havior in African American students greatly

exaggerated observed levels of problem behav-

ior. In contrast, results of the current study did

not show signs of teacher bias manifested in

elevated ratings of ethnic minority students.

However, the current investigation differed

from Sonuga-Barke et al. in several important

ways, including the cultural context, ethnic

groups examined, and measures utilized. Evi-

dence of biased ratings from a U.K.-based study

may not generalize to United States culture.

Indeed, a recent U.S.-based study conducted

by Ramirez and Shapiro (2005) showed student

ethnicity (Hispanic or Caucasian) had no effect

on ADHD-IV ratings completed by Caucasian

teachers in an analog setting. Not only did the

current investigation provide further evidence

that ratings of Caucasian teachers (95.5% of

sample) are not biased against ethnic minority

(African American and Hispanic) students, it

also suggested teacher rating scale data may

more accurately reflect true behavioral levels of

these students as compared to their Caucasian

peers. Although only two studies comparing

teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms to direct

observations have been conducted in the U.S.,

neither has produced evidence of bias against

minority students in the form of inflated teacher

reports of ADHD symptoms.

Rater Effects

Numerous cross-cultural studies (e.g., Alban-

Metcalfe, Cheng-Lai, & Ma, 2002; Mueller et al.,

1995) have demonstrated the influence of rater

culture on perceptions of ADHD symptoms.

Ramirez and Shapiro (2005) provided evidence

for rater effects across ethnicities in the United

States. Specifically, their investigation showed

Hispanic teachers rated the behavior of His-

panic students more severely, suggesting they

hold stricter standards for behavior in students

of their own cultural background (Ramirez &

Shapiro, 2005). Unfortunately, the homogenous

sample of teachers in the current study does not

permit statistical analysis of effects of teacher

ethnicity. Nonetheless, the current results could

be explained by variation in teachers’ standards

for student behavior. One possible explanation

for results of the current study is that Caucasian

teachers hold students of their own ethnicity

to different behavioral standards. Significant

differences in correlations across student eth-

nicity suggest that observable ADHD symp-

toms of ethnic minority students are more

likely to be reflected in rating scale reports of

Caucasian teachers, whereas observable

430

HOSTERMAN, D

U

PAUL, AND JITENDRA

symptoms of Caucasian students may less

often manifest in teacher ratings.

This pattern is likely a mechanism of subtle

cultural perspectives. Past studies have demon-

strated that teachers are less tolerant of behav-

iors contrasting their own cultural expectations

(Gerber & Semmel, 1984; Lambert et al., 2001).

For example, it is possible that Caucasian teach-

ers are more sensitive and attuned to behaviors

of their ethnic minority students because the

movement styles, speech patterns, or manner-

isms of these students differ from their own.

This explanation is consistent with results of the

current study, in which off-task motor and off-

task verbal behaviors of ethnic minority stu-

dents explained significantly higher amounts of

variance in teacher’s ratings of hyperactive-

impulsive symptoms. Indeed, results of Puig

et al. (1999) showed teachers in the United

States may have a lower threshold of toler-

ance for behavior of African American stu-

dents. Ramirez and Shapiro (2005) describe

an adult threshold hypothesis in which teach-

ers from a certain culture will tolerate a range

of student behavior that remains within so-

cially established limits, but perceive any be-

haviors violating cultural standards as abnor-

mal. In other words, Caucasian teachers may

be habituated to off-task behaviors common

in children from their own culture. Behaviors

blending easily into a teacher’s familiar cul-

tural landscape may not feature prominently

during reflections on accumulated past expe-

riences with a target student. However, results

of this study do not suggest this heightened

sensitivity applies only to inappropriate class-

room behaviors, but show teachers are also

more likely to notice appropriate classroom

behaviors of ethnic minority students (e.g.,

active engagement).

Instrument Bias

Large scale studies of the CTRS and

ADHD-IV suggest these scales form similar

constructs and factors across ethnicities. How-

ever, this research also shows ratings of stu-

dents in certain ethnic groups are more likely to

fall in clinical ranges and be influenced by fac-

tors like SES, gender, and ethnicity (e.g., Reid

et al., 2000, 2001). Several investigators have

suggested separate norms may be needed for

gender and ethnicity, but all recognize the need

to rule out true behavioral difference through

direct observation (e.g., Epstein et al., 1998;

Reid et al., 2001). Within the current study, only

one significant difference between groups

emerged among the four ADHD indicators.

That is, students in the ethnic minority group

received significantly higher scores on the

ADHD-IV Hyperactive-Impulsive subscale in

both reading and math. However, direct obser-

vation data also showed that ethnic minority

students exhibited significantly higher levels of

off-task verbal behaviors, which are captured by

this scale. Thus, it appears this difference in

rating scale scores is likely rooted in true be-

havioral difference.

Although results of the current study do not

produce any evidence of inherent bias against

ethnic minority students in the CTRS and

ADHD-IV, the current data and sample are

clearly not sufficient to answer this question.

One study of the CTRS showed that when com-

pared to Caucasian students, African American

students received elevated scores, and Hispanic

students received lower scores (Langsdorf et al.,

1979). Analyses that combine these two groups,

as in the present study, cannot address the need

for separate norms for ethnicity. Further re-

search on the question of instrument bias and

need for ethnicity-specific norms is needed. Re-

search should also attend to the question of

whether ethnic differences impact a student’s

probability of meeting the clinical cutoff for

ADHD.

Disproportionate Referral and Placement

The hypothesis of bias in teacher ratings was

based on data showing that African American

and Hispanic students are referred for evalua-

tion and placed into special education at dispro-

portionately high rates (Coutinho & Oswald,

2000; Hosp & Reschly, 2003; Oswald,

Coutinho, Best, & Singh, 1999). Although con-

trary to the original hypothesis, results of the

current investigation are still consistent with

this referral pattern. This study does not sug-

gest teachers are likely overreferring ethnic

minority students by exaggerating their symp-

toms but may actually report behavior of

these students with greater accuracy. Instead,

results suggest disproportionate placement

may arise from underidentification and refer-

ral of Caucasian students relative to true lev-

431

TEACHER RATINGS OF ADHD IN ETHNIC MINORITY STUDENTS

els of observable symptoms. Similar results

were obtained in VanDerHeyden and Witt

(2005), who found teacher referrals of Cau-

casian students to the problem solving team

were less accurate than referrals of ethnic

minority students. Uneven distributions of re-

ferral across ethnicities may be influenced by

the tendency of Caucasian teachers to less

aptly identify problem behaviors in students

of their own culture. Because Caucasian

teachers are more likely to notice ADHD

symptoms in ethnic minority students, those

students may more often be referred and

placed into special education.

Limitations and Directions for

Future Research

The results and conclusions of the current

study must be considered in the context of sev-

eral limitations inherent in the design and sam-

ple. Results of this study have limited external

validity and may not generalize to schools in

other geographical areas, students of other eth-

nic backgrounds, or schools and classrooms

with different ethnic compositions (e.g., non-

Caucasian majorities). Nor can results be ex-

tended to teacher reports of different types of

student behaviors (e.g., internalizing symptoms)

or referrals (e.g., for academic concerns). It is

important that future investigations examine

whether similar patterns emerge in schools with

varying characteristics.

Construct validity must also be considered.

Although SES was treated as a covariate in this

study, other variables correlated with student

ethnicity (e.g., academic performance and im-

pact of a novel observer) may play a significant

role in influencing teacher ratings. Future stud-

ies should consider a broader range of student

characteristics and use statistical methods to

account for the influence of variables that vary

significantly across ethnic groups and may im-

pact teacher ratings. Similarly, ethnic composi-

tion of the school should be considered in future

studies because it can influence the impact of

SES (Hodgkinson, 1995).

A third and significant limitation of the cur-

rent study is the combination of African Amer-

ican and Hispanic students into a single ethnic

minority group. In this design, no conclusions

can be drawn for either ethnic group indepen-

dently, although it is very likely that teacher

perceptions of these two groups may differ sig-

nificantly. In fact, past research shows variation

in base rates of ADHD across Hispanic and

African American groups. The original research

question for this study focused on comparing

African American and Caucasian groups exclu-

sively. Because participants were drawn from

an existing sample of a larger study, combining

ethnic minority groups was necessary to obtain

sufficient power. This design also fails to ad-

dress the unique heterogeneity within each eth-

nic group. For example, within the Hispanic

population, influence of acculturation level, lan-

guage dominance, and country of origin may be

particularly salient. Cultural factors such as re-

ligion, parenting styles, and behavioral stan-

dards may also vary within groups and influence

teacher ratings. Future research should examine

similar questions in samples large enough to

support distinct groups of African American

and Hispanic students, and eventually examine

the unique dynamics within each ethnic group.

Thus, results of the current study can only sug-

gest presence of ethnic variation in accuracy of

teacher ratings but cannot inform specific

knowledge of between or within group differ-

ence and subtle cultural mechanisms.

A fourth limitation of this study was homo-

geneity in teacher ethnicity. Although the vast

majority of teachers across the nation are Cau-

casian, analyzing effects of other teacher per-

spectives is important to gaining a full under-

standing of the cultural dynamics involved in

teacher ratings of ADHD. Future investigations

should examine effects of varied combinations

of teacher and student ethnicities on accuracy of

rating scale data. The current study also did not

account for the ethnicities of individuals col-

lecting direct observation data. Although obser-

vation data are often assumed to be the gold

standard for measuring behavior, it is possible

that correlations between direct observation

data and teacher ratings were an artifact of

shared perspectives of teachers and raters from

common backgrounds. Future research should

systematically vary observer ethnicity and in-

clude IOA comparisons across raters of differ-

ent ethnicities to investigate the influence of this

variable and ensure objective observation data.

Future studies should be improved by closer

control and attention to several additional vari-

ables. Efforts should be made to minimize the

latency between direct observations and com-

432

HOSTERMAN, D

U

PAUL, AND JITENDRA

pletion of teacher ratings to ensure that interim

behaviors do not influence teacher perspectives.

Ideally, teachers would also remain blind to

student factors such as ADHD status and aca-

demic levels. Given the large number of com-

parisons completed in this study, the potential

influence of family wise (Type I) error rate

represents another limitation. Results would be

strengthened by greater statistical control for

family wise error rate. Finally, the effect of

teacher efficacy, a teacher’s beliefs that she can

influence a student’s learning ability and behav-

ior (Frey, 2002) warrants attention in future

investigations. Frey (2002) found teachers’ per-

ceptions of their classroom management and

discipline skills significantly predicted place-

ment referrals for behavior problems.

Implications for Practice

This investigation has several important im-

plications for practitioners in school and clinical

settings. Most importantly, results of this study

suggest school psychologists should interpret

ADHD rating scale data and teacher referrals

with caution. When interpreting these data, school

psychologists must consider the influence of eth-

nicity on teacher ratings. If results of the current

study are confirmed in later replications, practitio-

ners may lend more credence to Caucasian teach-

ers’ ratings of ethnic minority students. In con-

trast, knowing the same teacher’s rating of ADHD

symptoms in a Caucasian student may be less

sensitive to observable symptoms; the practitioner

may devote more time and consideration to direct

observation data.

These results also emphasize the importance

of using observational codes that compare be-

haviors of the target student to those of an average

peer. Use of local, within-classroom comparisons

will show whether the student’s behaviors are

truly unique among those of their classmates.

Such comparisons should also consider local ex-

pectations for student behavior and ethnic compo-

sitions of the classroom. Practitioners must also

attend to the possible influence of the rater’s eth-

nicity when reflecting on new referrals and inter-

preting rating scale data. These results emphasize

the importance of utilizing multimodal behavioral

assessment including varied approaches to mea-

surement, perspectives from multiple reporters

(including parents), and information on student

behavior across settings to ensure bias in any

single aspect of the assessment does not dominate

the final conclusion. In sum, knowledge of cul-

tural issues related to teachers’ reports of ADHD

symptoms is important to ensuring accurate diag-

noses of ADHD in different ethnic groups.

Conclusions

Contrary to the original hypothesis, results of

the current study suggested teacher’s ratings of

ADHD symptoms in ethnic minority students

are more accurate reflections of true behavioral

levels, based on direct observation data, than are

ratings of Caucasian students. Considering

Chang and Stanley’s (2003) definition of bias as

differing perceptions of “typical” and “atypical”

behavior across ethnic groups that results in

varying appraisal or actions based on the same

behavior sample, these findings suggest pres-

ence of “bias” in teacher ratings of ADHD

symptoms. However, this “bias” does not man-

ifest as the hypothesized exaggeration of symp-

toms in ethnic minority students, but rather as

possible underidentification of ADHD symp-

toms in Caucasian students.

Variation in teacher ratings of ADHD symp-

toms across student ethnicity is best explained

by an interaction between rater and student eth-

nicities. The question of teacher bias and varied

standards for student behavior will only be re-

solved through more studies of this nature. Fur-

ther research is needed to determine how accu-

racy of rating scale data is impacted by varied

combinations of teacher and student ethnicities.

References

Alban-Metcalfe, J., Cheng-Lai, A., & Ma, T. (2002).

Teacher and student teacher ratings of Attention-

Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in three cultural

settings. International Journal of Disability, De-

velopment and Education, 49, 281–298.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnos-

tic and statistical manual of mental disorder. (4th

ed., text revision) Washington, DC: Author.

Anastopoulos, A. D., & Shelton, T. L. (2001). As-

sessing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press.

Arnold, L. E., Elliott, M., Sachs, L., Bird, H., Krae-