21

20

Sarah Wintle

With its vast horizons, Australia remains mysterious even to its own

inhabitants. The southern and eastern seaboards with their sprawling

hubs of urbanisation are very different to the isolation of Central and

Northern Australia. Indeed in the southern states, people are comfort-

ed by the nostalgia of grazing pastures, boxed hedges and the cottage

garden (now more popularised as the suburban backyard) giving a hint

of European familiarity. However, in the far reaches of the Kimberley

and through the desert, red sand and spinifex create intriguing other-

worldly terrain.

Now enter the grandly titled Australian Garden, a newly created

public garden, thirty kilometres from Melbourne on the city’s southern

fringes, which beckons a journey into the Australian landscape.

The Australian Garden opened in late May 2006. It is the Stage 1

realisation of the Australian Garden Masterplan which won the Aus-

tralian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA) National Overall Award

for Excellence in 1997. The creative landscape direction was again recog-

nised at AILA’s Victorian Award for Excellence in Landscape Architec-

ture in November 2007 some ten years later. It also won the 2006 Victo-

rian Tourism Awards and Australian Tourism Awards (new tourism

development) making it a fitting addition to, “Victoria: The Garden

State”, as the local number plates on cars decree.

Located within the Royal Botanic Gardens of Cranbourne, the Aus-

tralian Garden is the jewel in the crown of this verdant 363-hectare park

containing native bushland, woodland and wetland. The Australian Gar-

den is both a place in which plants are grown, studied and exhibited, and

an “experience” whether it be a family outing or a quiet retreat from the

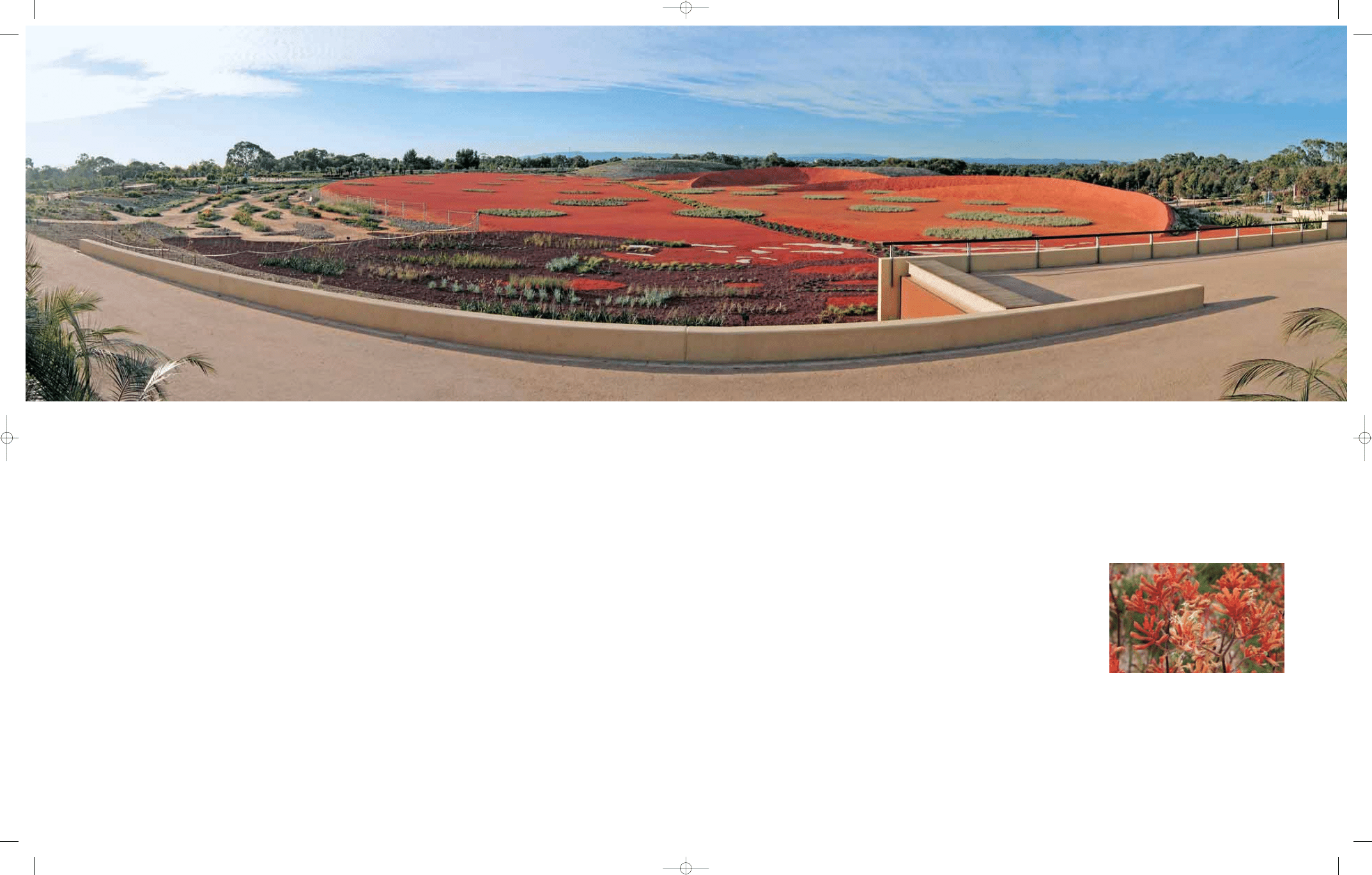

The best view of the heart of the Australian Garden’s Red

Sand Garden is from the Visitor Centre.This part of the

garden is an ode to the vast Australian desert.

Below: Anigozanthos ‘Bush Ranger’ is the result of a cross

between Anigozanthos humilis and Anigozanthos flavidus.

A U S T R A L I A N B Y D E S I G N

The Australian Garden at the Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne, south of Mel-

bourne, displays iconic Australian landscapes in a concept that reflects a country

slowly letting go of its European roots and realising its potential.

020-026.qxd 26.03.2008 12:50 Uhr Seite 20

23

22

hustle and bustle of city life. It enables the visitor to essentially travel to

each corner of Australia and experience an abundant array of plants

sourced from Queensland’s north to Tasmania’s south. It is not a zoolog-

ical garden and yet native animals and birds including koalas, Willie

Wagtails and Superb Fairy-wrens can be spotted during various seasons.

Designed by Taylor Cullity Lethlean and well-known horticultural-

ist Paul Thompson, the Australian Garden is intended to share the

“beauty and diversity of Australian plants” and “explore the connections

that exist between people, plants and landscapes”. Lofty ambitions per-

haps, but Stage 1 of the garden succeeds with an ease of design which

ushers visitors in a circular motion past the centrepiece Red Sand

Garden, a stunning Rockpool Waterway and 90-metre long Escarpment

Wall, and then on to five Exhibition Gardens. The journey then spills out

to an Arid Garden and Dry River Bed recreation before a number of

more familiar garden styles meet at the Visitor Centre and the Booner-

wurrung Cafe. The western side of the Australian Garden, influenced by

“the natural world where free flow forms (and) rich sensory experi-

ences”, is arguably the most engaging aspect of the project.

D

esign Director, Perry Lethlean, said the greater botanical garden

site is abundant with bushland and habitat. “But it had limited

opportunity for more horticultural design.” Lethlean said the

design team wanted visitors to the garden not to see the Red Sand

Garden centrepiece until they were beyond the Visitor Centre.

“Then the garden reveals itself. Looking at the Sand Garden from

above (at the Visitor Centre) creates an almost Zen-like state where peo-

ple can contemplate just how precious the landscape is,” said Lethlean.

And why aren’t people encouraged to walk on it? It is purposefully

confrontational and symbolic says Lethlean. “We were seeking a telling

symbol of the Australian continent and it was important to convey the

scale and grandeur and mystery of the place.”

Inviting the visitor to absorb the Red Sand Garden simply by view-

ing, but not experiencing the special space in a tactile way, is disappoint-

ing to some, especially when many people in this corner of Australia have

never had the opportunity to traverse a desert-like landscape. This is

where the garden retains a traditional approach to the botanical garden

– look but don’t touch.

“Australia’s inland is still a bit untouched. We don’t need to occupy

it,” says Lethlean. And while Stage 1 is a journey inland to the continen-

tal edge, Lethlean promises Stage 2 will be “more immersive”.

An additional 10 hectares of major landscape features including a

lake, an events space, hill-top viewing area, and picnic facilities are due to

commence development in mid-2008 and be opened in 2011.

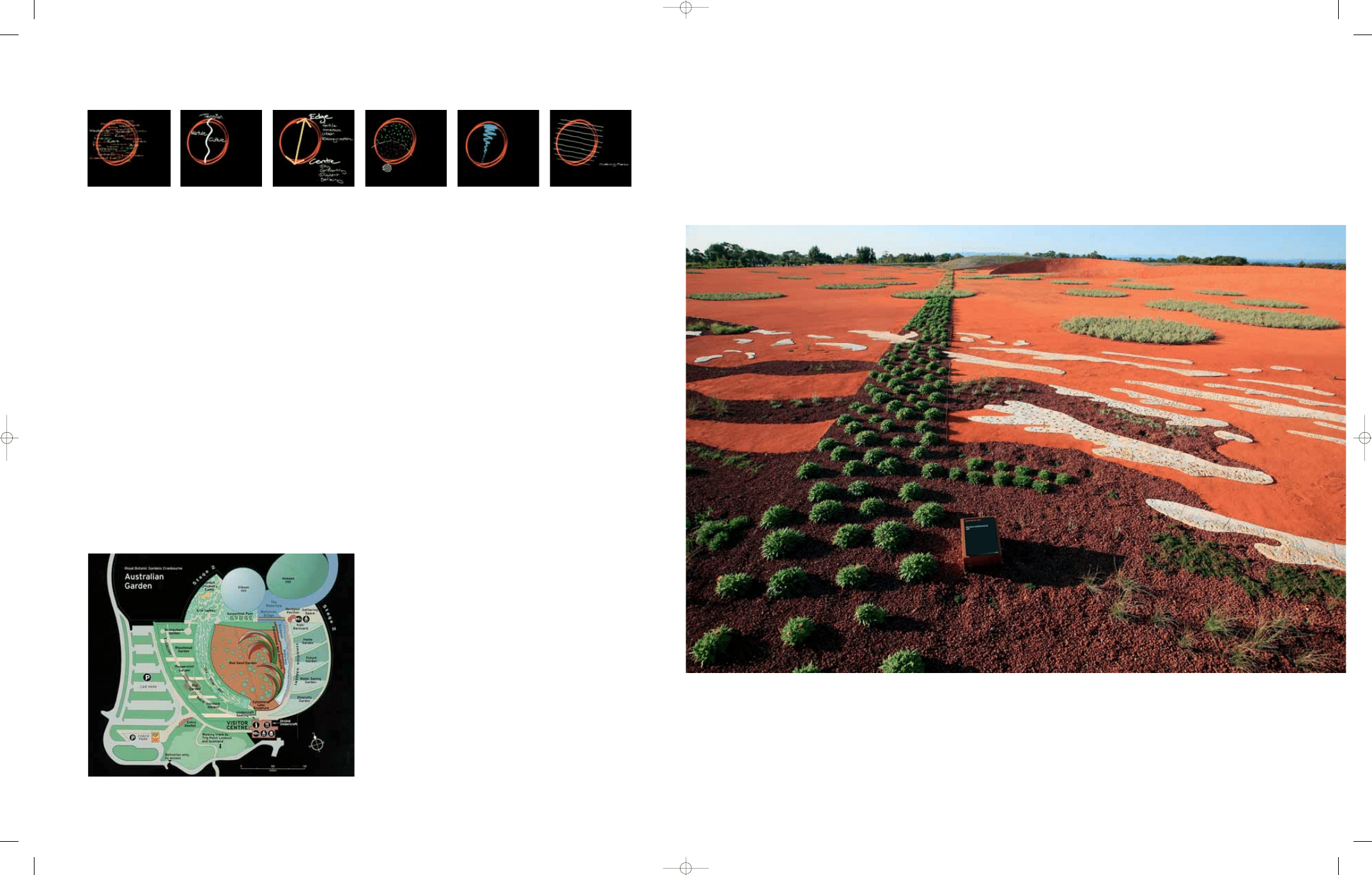

The vast central Red Sand Garden blends with the flat dry

river environment. Biomorphical ceramic elements, a sculp-

tural work by Mark Stoner and Edwina Kearney called

Ephemeral Lake, reflect the shapes of ephemeral pools.

The western side of the Australian Garden takes its cues

from nature, like the woodland, sand garden, chasm and

marsh gardens.The eastern side is more contrived: exhibi-

tion gardens line the promenade.

The challenge was how to provide a conceptual framework

and visitor orientation strategy: the garden should express

the tension between natural and human-made landscapes

and reflect a journey from the arid centre to the fertile parts

of Australia. Principal orientation devices are the waterways

and ordering marks running across the garden.

The Challenge

The Tension

The Journey

The First Impression

The Water Journey

The Ordering Marks

020-026.qxd 26.03.2008 12:50 Uhr Seite 22

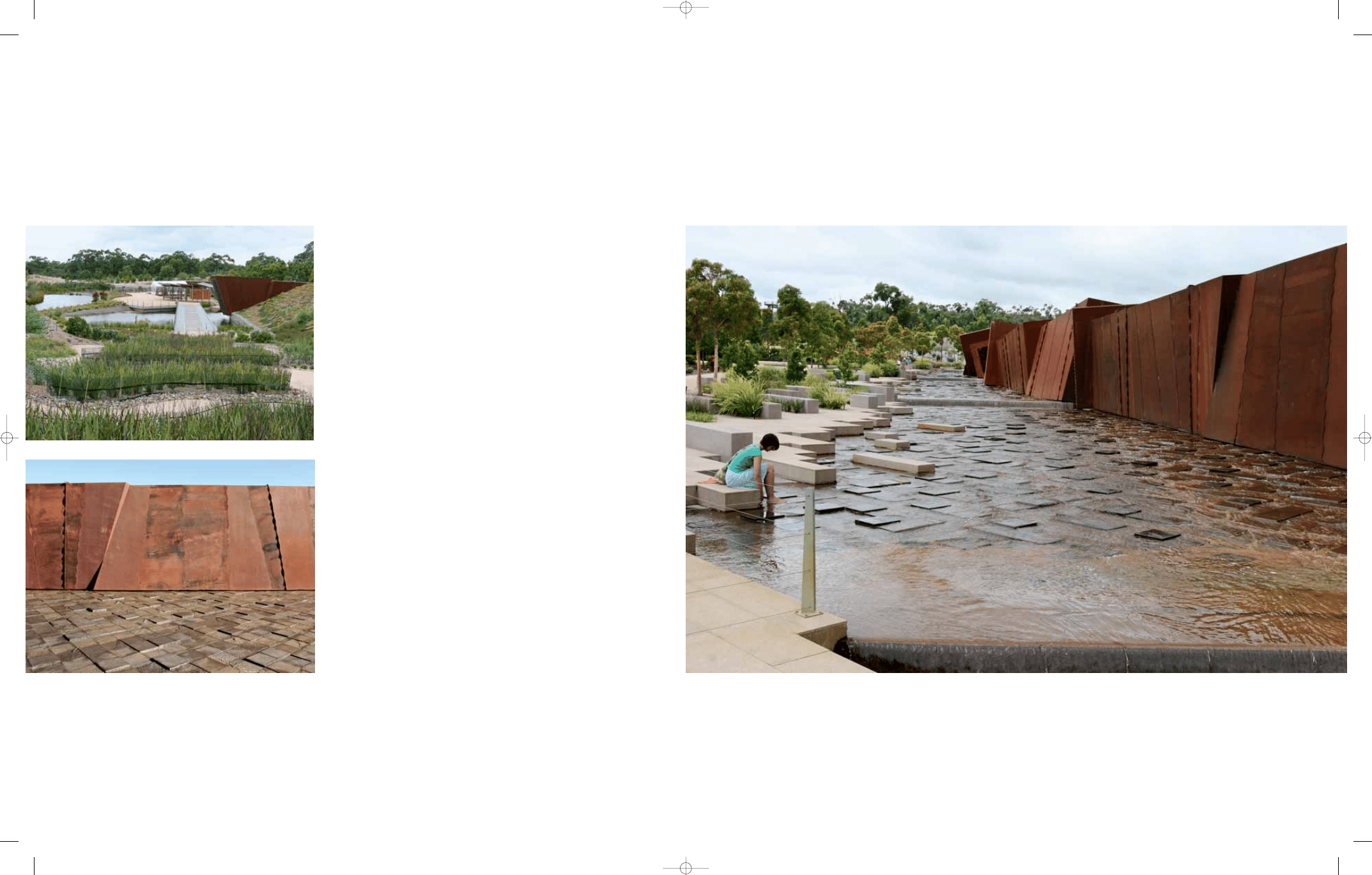

At the Rockpool Waterway, the pavers, some raised to bench

height, populate the staggered shoreline and continue below

the surface of the waterway as a variegated pattern.

The Australian Garden displays creativity through the interpretation

and recreation of iconic Australian landscapes, from the amber interi-

ors to plunging sandstone escarpments, like that found at King’s Canyon

in the Northern Territory and Purnululu (Bungle Bungle) National Park

in Western Australia. Interactivity within the space is aided by the obvi-

ous – plant labels and signage – and the subtle and intelligent layout

which effectively guides garden-goers through each facet of design. Fur-

thermore, the Australian Garden is educational with Volunteer Master

Gardeners on hand, and regular tours including Aboriginal Dreaming

guided walks by Wurundjeri elders.

P

icking up on the trend for Australian’s fervent home improve-

ment and renovation desires, the Australian Garden markets to

the masses with the call card of providing “inspiration to home

gardeners”. The Exhibition Gardens provide examples of how Australian

plants can be used in the home garden. Beyond this, the Australian Gar-

den is a place to connect with earth, sky and the bounty of Australia’s

diverse plant life. The Australian Garden boasts approximately 100,000

plants, including 1,000 trees in an impressive 15 different landscape dis-

plays and exhibition gardens. While drawing inspiration from the Aus-

tralian landscape may seem obvious, it has only recently become “main-

stream” with the past tendency coming from European cues. People

have been more likely to plant roses than native Australian orchids or

Kangaroo-paw wild flowers.

The Australian Garden is different from other botanical gardens dis-

playing indigenous plants because of its visionary design and recreation

of typically “northern Australian” landscapes such as the Red Sand Gar-

den, evoking the arid red centre of the continent. Typically Australian

botanical gardens are arboretums in design, as opposed to freeform

replications of the sometimes unruly but often subtle Australian land-

scape. Entering the site, visitors may be struck by how the long entrance

with rugged scrub either side resembles national parks further afield in

Gippsland. Signs like “Slow down for the lizards” and “Slow down for

bandicoots” add to the effect.

The sounds of the Rockpool Waterway, swerves of sand and soil and

the touch of stone certainly reinforce a sense of connectedness with the

land. Organic land formations dramatized in the landscape architecture

tell the story of a continent shaped by inland seas and huge shifts of land

plates in times gone by. Greg Clark’s Escarpment Wall sculpture (2005)

was a personal favourite for its audacious interplay between nature and

geometry, much like gorges in the faraway Northern Territory.

Just beyond the Escarpment Wall, there are recycled edged garden

beds and a meandering Serpentine Path that showcases plants like Stiff

25

24

The Serpentine Path leads visitors from the Arid Garden to

the Rockpool Waterway and the Escarpment Wall sculpture.

The 90-metre long corten steel wall was designed by sculp-

tor Greg Clark with Taylor Cullity Lethlean.

AUSTRALIAN GARDEN, ROYAL BOTANIC GARDENS

CRANBOURNE, AUSTRALIA

Client: Royal Botanic Gardens, Cranbourne

Landscape architects: Taylor Cullity Lethlean with Paul

Thompson

Architects: Gregory Burgess Architects (Rockpool Shelter);

Kirsten Thompson Architects (Visitor Centre)

Sculpture: Mark Stoner and Edwina Kearney (Ephemeral

Lake); Greg Clark (Escarpment Wall)

Lighting: Barry Webb and Associates

Exhibition Gardens: Site Office (Future Garden); Site Office

and Particle (Diversity Garden); MDG Landscape Architects

(Water Saving Garden); Coomes Landscape Architecture and

Urban Design (Home Garden); Marc McWha Landscape

Architects (Kid’s Backyard)

Construction: 1995 - ongoing

Area: 25 hectares

Costs: 8 million Australian dollars

020-026.qxd 26.03.2008 12:50 Uhr Seite 24

26

Raiper Sedge and Eremophilia longifolia, a pretty shrub with pea-like

pink flowers. A visitor can just imagine emus wandering around the

nearby Arid Garden, such is the authenticity. In the garden’s north west,

the textural dimension of native bushes comes to the fore in a series of

patchwork-like gardens, aptly named Peppermint, Box and Ironbark

Gardens.

There’s a refreshing acceptance of messiness within the Australian

Garden and only the toughest plants survive due to the ever-present

drought conditions. Mass plantings are very Australian in their casual-

ness and yet surprisingly sophisticated. And in this sense, the garden is

unlike others with a “kept” look. Natural materials are well utilised to

serve the garden’s practicalities: corten steel is used for signage cubes,

recycled plastics create the garden beds and, in other instances, gardens

are demarcated by rope.

E

co principles are embedded in the whole ethos of the garden with

plants chosen for their low water requirements and local mate-

rials with low embodied energy used without compromising the

high quality of the built outcome. Says Lethlean: “We were looking for a

big impact using low impact materials.” Future botanical gardens will

have to demonstrate similar environmental aptitude with the effects of

climate change being felt countrywide.

Essentially, the Australian Garden is youthful, reflecting a relatively

new nation (in post-colonised terms) and the gradual acceptance and,

indeed embracing, of native plants. Although Australia is not yet a repub-

lic, this garden reflects an Australia slowly letting go of the European

motherland and realising its potential. Visitors talk animatedly in awe of

the diversity. “I’ve never seen that!” said one middle-aged woman. “It’s

terrific: I can’t get over the native plants!” said another.

Taylor Cullity Lethlean, collaborating with Paul Thompson, has envis-

aged this project with the client, Royal Botanic Gardens, as a departure

from the traditional – a brief that was also taken by participating design

outfits which conceived the exhibition gardens. With a seemingly blank

canvas, Taylor Cullity Lethlean have paid homage to the Australian land-

scape and, in turn, re-energised a new confidence in the soil.

The mood for change in Australia is strong as the recent 2007 Fed-

eral election result showed. And the Australian Garden has been devel-

oped at an important time in the country’s development when solutions

to the drought are sought, an apology to the Stolen Generation has

recently been made in Parliament and reconciliation with the Aborigi-

nal and Torres Strait Islander people is more compelling. It is a positive

garden, a garden for change and, as such, cements a uniquely Australian

identity.

Groups of Xanthoreas are a focal point in the Nothern Sand

Garden. Bottom: the Eucalypt Walk leads visitors through

woodland “fingers” separated by narrow clearings.The photo

shows the entrance of the walk.

020-026.qxd 26.03.2008 12:50 Uhr Seite 26

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

fizyka by lesnik id 176590 Nieznany

kompendium by Vaz id 242918 Nieznany

proj sygnalizacja by JJ id 3975 Nieznany

podnosnik A2 by Arti id 365542 Nieznany

LOW EMI PCB DESIGN id 273292 Nieznany

Antologia wstep by AG id 18051 Nieznany (2)

lecture 9 robust design id 2643 Nieznany

fizyka by lesnik id 176590 Nieznany

kompendium by Vaz id 242918 Nieznany

proj sygnalizacja by JJ id 3975 Nieznany

lepiaro by Wiola & me id 267144 Nieznany

obe w 9 tygodni [up by Esi] id Nieznany

p szczegolowe by lsz v1 2 id 34 Nieznany

pole placement robot design id Nieznany

(Zobowiazania by A)id 1486 Nieznany (2)

Abolicja podatkowa id 50334 Nieznany (2)

4 LIDER MENEDZER id 37733 Nieznany (2)

katechezy MB id 233498 Nieznany

więcej podobnych podstron