Improving primary care treatment of depression among patients with

diabetes mellitus: the design of the Pathways Study

Wayne Katon, M.D.

a,

*, Michael Von Korff, ScD.

b

, Elizabeth Lin, M.D., M.P.H.

b

,

Greg Simon, M.D., M.P.H.

b

, Evette Ludman, Ph.D.

b

, Terry Bush, Ph.D.

b

, Ed Walker, M.D.

a

,

Paul Ciechanowski, M.D., M.P.H.

a

, Carolyn Rutter, Ph.D.

b

a

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA 98195– 6580, USA

b

Center for Health Studies, Group Health Cooperative, Psychiatry Service, University Hospital, Seattle, WA 98195– 6580, USA

Abstract

This paper describes the methodology of a population based study of primary care patients with diabetes mellitus enrolled in a health

maintenance organization. The first goal was to determine the prevalence and impact of depression in patients with diabetes. The second

goal was to randomize approximately 300 patients with diabetes and major depression and/or dysthymia in a trial to test the effectiveness

of a collaborative care intervention in improving quality of care and health outcomes among patients with diabetes and depression. © 2003

Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Diabetes is a common and costly condition that affects 16

million Americans [1]. Patients with diabetes are at increased

risk of kidney disease, peripheral vascular disease, heart dis-

ease, lower extremity ulcers and amputations, retinal disease,

neuropathy, infections, digestive disease and periodontal dis-

ease [2]. The prevalence is as high as 20% in patients who are

65 years and over with significantly higher rates in minority

group members (African Americans, Hispanics and Native

Americans) [3]. The total direct medical costs and indirect

costs in the United States due to diabetes have been estimated

at $102 billion per year [4]. Patients with diabetes appear to

have increased risk of major depression. Depression may ad-

versely affect self-care regimens as well as increase risk of

complications such as diabetic retinopathy [5–7].

Anderson and colleagues’ recent meta-analysis of the

prevalence of major depression or depressive symptoms in

patients with diabetes found a two-fold higher prevalence

rate of depression in diabetics compared to controls in 20

controlled studies [5]. Current major depression was ob-

served in 10 to 15% of diabetics with similar prevalence

rates in Type 1 and Type 2 cases [5].

Both major depression and depressive symptoms have been

shown in most studies to be associated with glucose dysregu-

lation [6 – 8]. This may either be due to the adverse impact of

depression on diabetes self-care (i.e., diet, exercise, checking

blood glucose, and taking medications), [6 – 8] direct adverse

physiologic effects on glucose metabolism, [9] or a combina-

tion of these two mechanisms. Several studies have shown that

depression is associated with poor adherence to self-care reg-

imens such as checking blood glucose, following a special diet

and medication compliance, as well as less sensitivity to insu-

lin effects on lowering blood glucose [6,10].

Two small randomized trials have shown that nortripty-

line [11] and fluoxetine [12] were more efficacious in con-

trolling depressive symptoms than placebo in patients with

major depression and diabetes. One cognitive behavioral

trial also demonstrated enhanced efficacy compared to an

educational diabetes group [13]. One of these 3 trials found

that improved depression outcomes was associated with

improved HbA

1

C levels [13]. These three trials enrolled a

combined total of less than 180 patients and lacked power to

study key outcomes such as the effect of enhanced treatment

of depression on self-care regimens (diet, exercise, refilling

medication), disability, quality of life, and medical costs.

Whether enhanced treatment of depression improves glyce-

mic control is also an unanswered question.

The study that we describe has two arms: 1) a popula-

tion-based epidemiologic investigation of the prevalence

* Corresponding author. Tel.:

⫹1-206-543-7177; fax: ⫹1-206-221-

5414.

E-mail address: wkaton@u.washington.edu (W.J. Katon).

General Hospital Psychiatry 25 (2003) 158 –168

0163-8343/03/$ – see front matter © 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/S0163-8343(02)00013-6

and impact of depression in patients with diabetes enrolled

in a health maintenance organization; and 2) a randomized

controlled trial to test the effectiveness of collaborative care

interventions in improving the quality of care and outcomes

of depression among patients with diabetes in primary care.

This paper describes the design of these research studies and

the rationale for key methodologic decisions. The first part

of the Methods section will describe the recruitment for the

epidemiologic phase of the study, and the second part the

design of the randomized controlled trial.

2. Methods

The Pathways Study was developed by a multidisci-

plinary team in the Department of Psychiatry at the Univer-

sity of Washington and the Center for Health Studies at

Group Health Cooperative. Group Health is a nonprofit

health maintenance organization with 30 primary care clin-

ics in Western Washington State.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental

Health Services (NIMH) Division of Intervention and Ser-

vices Research. The randomized controlled trial proposed to

test the effectiveness of a collaborative care intervention

versus usual care. Collaborative care is a multimodal inter-

vention that includes integration of a “care manager” (often

a nurse or mental health specialist) into primary care. The

“care manager” works with both the patient and primary

care physician and helps with developing a shared definition

of the problem, providing patient education and support,

developing a shared focus on specific problems, targeting

goals and a specific action plan, offering support and prob-

lem-solving to optimize self-management, achieving closer

monitoring of adherence and outcomes, and facilitating ap-

pointments to the primary care physician or specialist for

patients with adverse outcomes or side-effects [14]. The

study protocol was reviewed and approved by institutional

review boards at the University of Washington and Group

Health Cooperative.

2.1. Study setting

Nine Group Health Cooperative primary care clinics in

western Washington were selected for the study. We se-

lected clinics based on 3 criteria: 1) clinics with the largest

number of diabetic patients (to save screening and interven-

tion costs; 2) clinics within a 40-mile geographic radius of

Seattle in order to decrease travel time for nurse “care

managers”; and 3) clinics with the highest percentage of

minority patients. Because minorities have higher rates of

diabetes, we were able to enroll substantial numbers of

minority patients even though the general population was

predominantly Caucasian.

2.2. Sample recruitment

A major methodologic issue was how to best screen and

enroll a representative sample of diabetic patients with ma-

jor depression and dysthymia. The screening was facilitated

by Group Health’s prior development of a population-based

diabetes registry. Patients are added to the diabetes registry

based on: 1) currently taking any diabetic agent; or 2) a

fasting glucose

ⱖ126 confirmed by a second out-of-range

test within one year; or 3) a random plasma glucose

ⱖ200

also confirmed by a second test within one year; or 4) a

hospital discharge diagnosis of diabetes at any time during

GHC enrollment or two outpatient diagnoses of diabetes

[15]. The goal of the epidemiologic survey was to success-

fully screen at least 4,500 primary care patients with diabe-

tes with approximately 630 expected to meet criteria for

major depression and/or dysthymia. The goal of the ran-

domized trial was to enroll approximately 300 depressed

patients in the randomized controlled trial. After consider-

ing mail versus telephone screening for depression, we

decided on mail screening as the most cost effective mech-

anism based on prior studies by members of our study group

that were able to attain 60 to 65% recruitment rates with

mail screening [7,16]. To potentially increase patient re-

sponse rates, we presented the study to each of the 9 clinics

and requested written permission from all primary care

physicians to use a stamp of their signature in the approach

letter describing the study. Among the 113 doctors, 101

(90%) agreed to allow us to use their signature stamp. For

physicians refusing to let us use their signature, we used the

name of the GHC Chief of endocrinology, Dr. David Mc-

Culloch.

Patients were screened by mail in sequential waves with

approximately 700 questionnaires sent per month. A $3 gift

certificate for a local store was included with the mailing to

encourage response. If the patient did not return a mailed

packet by 4 weeks, a second packet was sent. If this second

packet was not returned by 2 weeks, the patient received a

telephone reminder call. The first mail-screen had a re-

sponse rate of approximately 38%, the second mailing in-

creased the response rate to 47%, and the combination of the

telephone reminder and a last mailing 6 months after the

telephone reminder increased the final response rate to

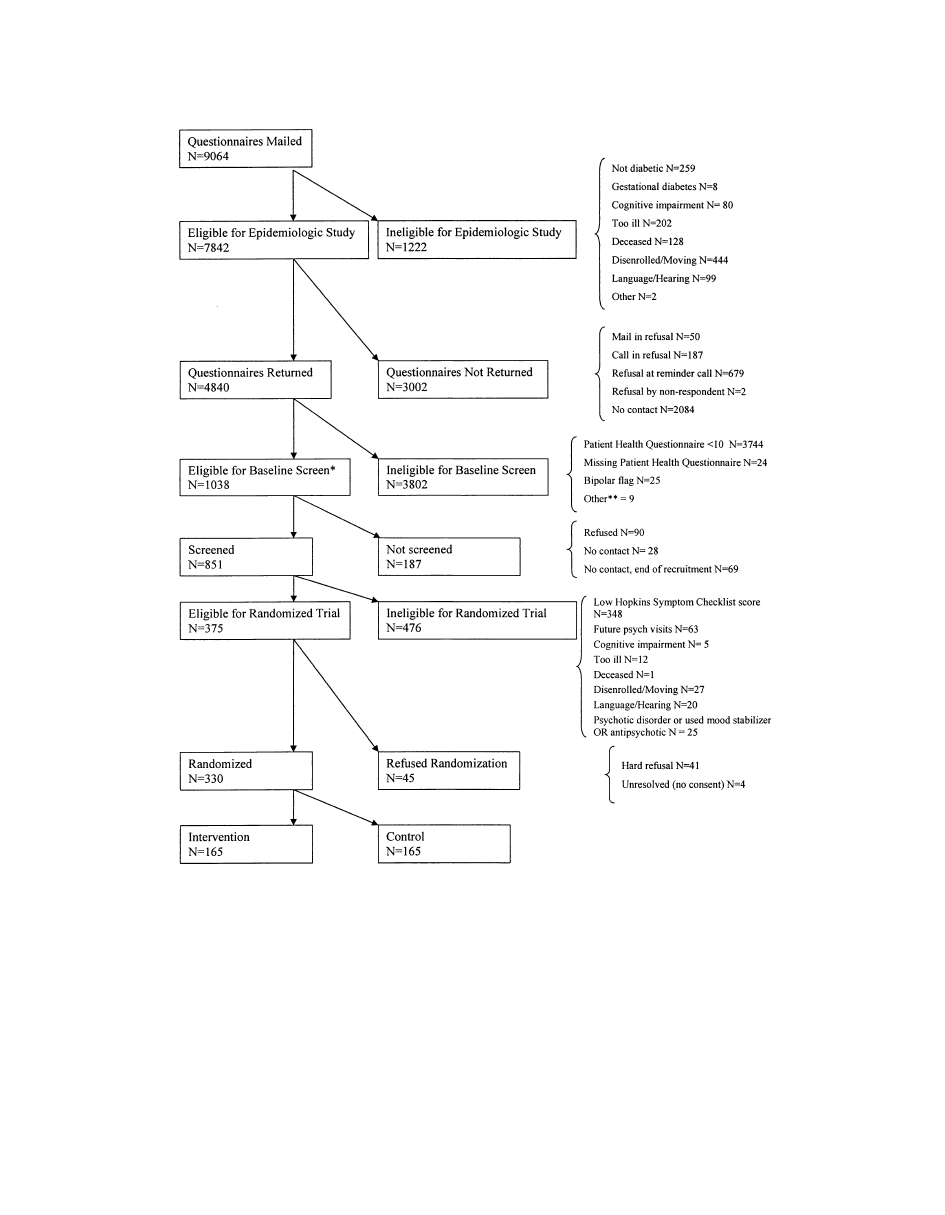

61.7%. Figure 1 describes the recruitment and reasons for

ineligibility or refusal at each phase of the study. The study

team has received permission from the Group Health Co-

operative Institutional Review Board to collect aggregate

data on nonrespondents to ascertain whether there are dif-

ferences in demographic (age, gender) or clinical variables

(health care costs, medical comorbidity, type of diabetes or

depression treatment, and HbA

1

C levels) between respon-

dents and nonrespondents.

A major methodological question was: “What is the best

depression screening tool to use?” Ideally this screen should be

brief, easy to score and provide both a DSM-IV diagnosis and

depression severity score. We elected to use the Patient Health

159

W.J. Katon et al. / General Hospital Psychiatry 25 (2003) 158 –168

Questionnaire (PHQ) based on this questionnaire’s ability to

provide both a dichotomous diagnosis of major depression as

well as a continuous severity score [17]. The PHQ diagnosis of

major depression has been found to have high agreement with

the diagnosis of major depression based on structure psychi-

atric interview [17]. Because we were also interested in the

DSM-IV diagnosis of dysthymia, which is not included in the

PHQ, we added questions from the NIMH Diagnostic Inter-

view Schedule [18] on dysthymia.

2.3. Methodology of the Pathways randomized controlled

trial

Patients were required to have a score of

ⱖ10 on the

initial PHQ in the mail screen, which has been found to be

the optimal cut-point in screening for major depression [17]

We required patients to have a second screen by telephone

about two weeks after scoring 10 or greater on the PHQ. On

this second screen, patients were required to have persistent

Fig. 1. Recruitment of epidemiologic study and randomized controlled trial.* Eligibility criteria: PHQ

⫽ 10 or greater.** Patients were categorized as

“Ineligible – Other” if: 1) they were enrolled in another study; 2) their spouse was enrolled in PATHWAYS; 3) they were high risk for self-harm or if they

refused a self-harm assessment; or 4) there were other special circumstances (i.e., – there was one case where the team deemed someone ineligible due to

a recent hospitalization for drug overdose).

160

W.J. Katon et al. / General Hospital Psychiatry 25 (2003) 158 –168

symptoms by having an SCL-20 depression [19] mean item

score of

ⱖ1.1. Double-screening eliminates those with tran-

sient or spontaneously resolving depression. A total of 348

patients were excluded based on an SCL

⬍1.1.

To recruit a representative sample, we had few medical

or psychiatric exclusions. We elected to include diabetics

who were already receiving antidepressant medication or

psychotherapy from nonpsychiatrist clinicians, but who still

had high depression scores. This decision was based on

prior findings that showed that many primary care patients

with depression are exposed to antidepressants at lower than

guideline-recommended dosage and duration [20]. Eligible

patients were ambulatory, English-speaking, with adequate

hearing to complete a telephone interview, and planned to

continue to be enrolled in GHC over the next year. Psychi-

atric exclusions were: 1) currently in care by, or scheduled

to see, a psychiatrist; 2) a diagnosis based on Group

Health’s automated diagnostic data of bipolar disorder or

schizophrenia; 3) use of antipsychotic or mood stabilizer

medication based on Group Health’s automated pharmacy

in the prior year; and 4) mental confusion on the interview

suggesting significant dementia (Fig. 1).

2.4. Randomization

After completion of the baseline telephone interview and

verbal informed consent, participants were informed that

they would be randomly assigned to the Intervention or

Usual Care group through a computer generated number.

Patients were told that if they were assigned to the Inter-

vention group a nurse would call them within one week to

set up an appointment. If they were assigned to the Usual

Care group they would receive a mailed written informed

consent for telephone follow-up calls and HbA

1

C blood

draws to sign and mail back, and the first telephone survey

call in three months.

After the baseline telephone call, the research assistant

handed a face sheet with a study identification number to the

project coordinator to put in an Access data base. The

Access data base then automatically generated a random

assignment number which indicated whether patients were

in the Intervention or Usual Care group. Randomization

allocation occurred in blocks of eight. For those patients in

the intervention group, the computer generated a face sheet

with a patient name and phone number that the project

coordinator delivered to the nurses. For both Intervention

and Usual Care patients the computer then added the patient

identification data to the telephone survey data base with the

specific dates for the series of follow-up interviews.

2.5. Intervention design

The intervention was an individualized, stepped care

depression treatment program provided by a Depression

Clinical Specialist (DCS) nurse in collaboration with the

primary care physician. This intervention design was based

on the intervention developed for the IMPACT Study,

which randomized 1801 elderly primary care depressed

patients to a nurse collaborative intervention or usual care

[21]. A key design question for the team was: “Would this

intervention be designed to enhance treatment of depression

only, or to improve quality of care for both depression and

diabetes?” We elected to design an intervention to improve

quality of care and outcomes of depression but to not di-

rectly intervene to improve diabetes education or care, ex-

cept to the extent that addressing diabetes care issues arose

in the context of treating depression. An example of a

diabetes issue that could have been addressed in problem

solving therapy would be if the patient chose lack of exer-

cise or having problems with diet as a problem she or he

wanted to work on. By improving depression care, we could

then test effects of improved depression outcomes on dia-

betes self-care (diet, exercise, medication adherence), and

glycemic control.

Efficacy studies often ask questions such as “Is this

antidepressant more effective than placebo?” The health

services question for this effectiveness study was: “Is an

innovative method to improve service delivery that provides

guideline level antidepressant treatment or brief psychother-

apy more effective than usual care?” In developing this

intervention, we tried to optimize patient recruitment and

retention by providing an initial choice based on patient

preference of either antidepressant medication or problem

solving therapy (PST). It is controversial whether providing

patient choice of treatment leads to better outcomes, [22]

but choice is more like “real world” treatment decisions that

physicians and patients negotiate. We expected choice to

enhance recruitment and retention of patients. Choice of

treatment is also consistent with the Institute of Medicine’s

emphasis on understanding patients’ beliefs and preferences

in negotiating a treatment plan [23]. Problem solving ther-

apy was chosen because it is patient-centered, brief and

well-accepted by primary care patients due to its psycho-

educational content. Problem solving therapy has been

found to be as effective in randomized trials in primary care

as antidepressants in improving depressive symptoms of

patients with major depression [24]. It was also easier to

train Depression Care Specialists in providing PST than

other forms of psychotherapy.

2.6. What type of professional should be trained as a

Depression Care Specialist (DCS)?

Given the need for the DCS to be proficient in medica-

tion management and PST, to have experience working with

patients with one or more chronic medical illnesses, and to

be comfortable working in a primary care setting, we chose

registered nurses to implement collaborative care treatment.

Registered nurses at GHC were already providing disease

management for diabetes and congestive heart failure.

Therefore, this model would have a greater chance to be

161

W.J. Katon et al. / General Hospital Psychiatry 25 (2003) 158 –168

integrated into the GHC plans for improving disease man-

agement of depression after the study.

We also required a registered nurse (R.N.) degree, not a

nurse practitioner (ARNP), since primary care physicians

would continue to prescribe and this level of training is

more generalizable and cost-effective.

We hired three half-time registered nurses. They each

covered two to four primary care clinics, that were geo-

graphically as far as 25 miles apart, with case loads of 40 to

65 patients each once the study was fully underway.

2.7. Training

Nurses received an initial one-week training course on

diagnosis and pharmacotherapy and an introduction to prob-

lem solving treatment methods. A psychiatrist, primary care

physician and psychologist participated in training. An in-

tervention manual from the IMPACT trial [25] was used to

train nurses on collaborative care, stepped care principles,

pharmacology and problem solving approaches.

Nurses were also trained using the manual for PST-PC

[26] during a training period following the protocol de-

scribed by Hegel and colleagues [27]. Formal training in-

cluded didactics, role play, observation of a videotaped

demonstration, and review of the treatment manual. Each

nurse was required to treat at least 4 depressed patients with

6 sessions of PST-PC over a 2-month period. Each session

was audiotaped, and sessions 1, 3 and 5 were rated using

Hegel’s PST Adherence and Competency Rating Scale [27].

Nurses were required to meet the criteria of at least 3 tapes

from each of two different patients’ audiotaped treatment

sessions being rated satisfactory by the team psychologist

(Dr. Ludman). During the training period, the nurses met

weekly with the psychologist for review of the audiotaped

sessions. During the course of the study, the nurses met

regularly with the psychologist to review audiotapes and

specific clinical problems arising in PST sessions. Group

supervision sessions were held weekly or twice a month for

the first months of the study, reducing in frequency over

time. During the second year, group supervision occurred

monthly. Individual PST-PC supervision sessions with

nurses occurred on an as-needed basis for review of difficult

sessions.

2.8. Collaborative care

A team of clinicians delivered the treatment for interven-

tion patients. Nurses carried out the majority of treatment

that included an initial one hour visit followed by twice a

month, half-hour appointments (telephone and in-person) in

the acute phase of treatment (0 to 12 weeks). The first

appointment included a semistructured biopsychosocial his-

tory, patient education, development of the therapeutic al-

liance, understanding the patient explanatory model of ill-

ness and negotiation whether to start treatment with an

antidepressant medication or problem solving therapy. Each

nurse had supervision twice a month with a team of a

psychiatrist, psychologist (on PST) and family physician to

review new cases and patient progress. Nurses interacted

regularly (via written notes and verbally) with the primary

care physician treating the patient. On alternative weeks,

nurses reviewed cases by telephone with the psychiatrist

supervisor. The psychiatrist supervisor regularly reviewed

choices and dosages of medication and clinical response,

and recommended changes, which the nurse discussed with

the primary care physician and patient.

A unique clinical monitoring system was developed us-

ing Pendragon software [28] for a hand-held organizer for

the nurses to enter tracking data after each patient contact

including initial PHQ score, initial date of intake, last date

seen and last PHQ score, whether the patient has had a 50%

decrease in PHQ score by 12 weeks, initial treatment (PST

or antidepressants), current treatment and number of outpa-

tient and telephone contacts. This monitoring system al-

lowed nurses and supervisors to easily check which patients

were due for telephone or in-person follow-up visits. Each

week these data were transferred to an Access file and an

updated printout of all cases was used in weekly supervi-

sion. This facilitated each supervisor’s review of the process

and outcomes of care for the large number of cases being

managed.

The printout included an asterisk for cases that had not

decreased 50% or more on the PHQ at 10 weeks. Supervi-

sion started on new cases, progressed to asterisked cases and

then to cases in initial phases of treatment.

2.9. Stepped care algorithm

A stepped care approach was used in which different

patients received different intensity of services based on

their observed outcome (Table 1). Stepped care recognizes

that patients have marked differences in psychiatric and

medical comorbidity as well as differences in response to

antidepressant medication and/or psychotherapy [29]. In the

Pathways trial if patients still had persistent depressive

symptoms (

⬍50% decrease in severity based on the PHQ)

10 to12 weeks after Step 1 level treatment with either PST

or antidepressant medication, they could either: a) switch to

a second antidepressant with a different mechanism or side-

effect profile; b) switch to the alternative treatment (from

PST to medication or vice versa); or c) receive augmenta-

tion of PST or antidepressant medication with the first

treatment they had received. This change in treatment at 10

to 12 weeks was labeled Step 2 care. Another option in Step

2 was a psychiatric consultation to evaluate treatment op-

tions. For patients who received one or more Step 2 inter-

ventions, persistent symptoms (

⬍50% improvement) and

lack of patient and clinician satisfaction with outcome after

a second treatment (8 to 12 weeks) could lead to referral to

the Group Health Cooperative (GHC) mental health system

for longer term follow-up including management by a psy-

chiatrist (Step 3).

162

W.J. Katon et al. / General Hospital Psychiatry 25 (2003) 158 –168

Step 1 included history taking and building the therapeu-

tic alliance, patient choice of initial treatment and behav-

ioral activation. In addition, the depression clinical special-

ist introduced the PHQ depression module as the key

monitoring tool for measuring response to treatment and set

up a schedule of telephone and in-person sessions. Regular

communication occurred with the primary care physician

(PCP). The goal of the intervention was clinical recovery

(

ⱖ50% decrease in PHQ score) and, if possible, remission

(a score of

⬍5 on PHQ) [17] and restoration of social and

vocational function. Once patients reached a significant

decrease in clinical symptoms, the nurse began continuation

phase treatment that involved monthly scheduled telephone

contacts. Nurses also set up optional continuation groups,

which involved a monthly group visit for patients with

persistent symptoms or social isolation instead of the

monthly telephone calls.

2.10. Usual care

Patients were informed prior to randomization that they

were eligible for a new program to help people with diabe-

tes better manage stress and depression. Patients were told

they would be called by the DCS within 10 days if they

were randomized to the intervention. It was also recom-

mended that whether or not they were chosen to receive the

additional services, they should work with their primary

care physician on these clinical issues.

In most cases, usual care for depression provided by

Group Health Cooperative family physicians involves a

prescription of an antidepressant medication, 2 visits over

the first 3 months of treatment and an option to refer to

Group Health Cooperative mental health services. Both

intervention and usual care patients could also self-refer to

a GHC mental health provider. We tracked and will report

these out-of-study mental health referrals and visits. Usual

care for diabetes in Group Health Cooperative is provided

by the primary care physician with occasional support from

diabetes nurses for patients with persistently high HbA

1

C

levels.

2.11. Evaluation

Given that patients entering the trial had evidence of at

least two medical illnesses, i.e., major depression and/or

dysthymia and diabetes mellitus, and that our intervention

was aimed primarily at improvement of depression, the

primary outcome variable was change in depressive symp-

toms. Changes in functioning were identified as important

secondary outcomes. Inherent in this discussion and the

focus of the intervention on depression was that if we

significantly improved depressive symptom and functional

outcomes, this would be considered a positive trial. We also

hypothesized that if the intervention significantly improved

depressive symptoms, we would find improvement on the

diabetes measures, including diabetes symptom burden, di-

Table 1

Stepped care intervention

Step 1: 0–12 weeks

History taking and building therapeutic alliance

Behavior activation based on increasing positive activities

Problem-solving therapy (PST) or antidepressant medication (patient choice)

Introduction of Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) as weekly measure of depressive symptoms

Schedule telephone and in-person follow-ups by Depression Clinical Specialist (DCS)

Regular communication with primary care physician

No Response

Recovery (

ⱖ50% decrease in PHQ OR

Step 2: 12 to 24 weeks

Remission (PHQ of

⬍5)

For patients who had not decreased by at least 50% on the initial PHQ

score and/or were dissatisfied with outcome, the DCS could:

Schedule monthly continuation telephone follow-up

a) switch to an alternative antidepressant medication if no or little

response to first medication

b) add an antidepressant if the patient had not responded to PST or add

PST if little or no response to antidepressant

c) augment with a second antidepressant if partial response to first

d) schedule a psychiatric consultation

Less than 50% Response Based on PHQ

Recovery or Remission

Step 3: 24–52 weeks

Schedule monthly continuation telephone follow-up

If patient has not had decrease by 50% in PHQ or remission:

a) consider referral to Group Health mental health service for longer-

term mental health care;

b) enter patient into DCS continuation/ maintenance phase group.

,

n

,

n

163

W.J. Katon et al. / General Hospital Psychiatry 25 (2003) 158 –168

abetes control and some measures of diabetes self-care

(particularly exercise and diet). The study was adequately

powered to detect a moderate-to-large effect on HbA

1

C. We

also planned a cost-effectiveness analysis (see below).

After randomization, telephone interviews were provided

at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months. Telephone interviews were

completed by interviewers blind to intervention status.

For measuring change in depression, the SCL-20 depres-

sion scale [19] was chosen to be the primary dependent

variable to measure change in affective symptoms based on

previous studies showing it to be sensitive to change

[30,31]. We used the PHQ at baseline, 6, 12 and 24 months

to measure changes in dichotomous diagnosis of major

depression as well as remission status (PHQ

⬍ 5) [17].

We utilized selected scales from the WHO-DAS-II

(Household and Work-Related Activities, Community and

Family Activities, Physical Health, Work Absenteeism and

Cut-Down days, Work Productivity) [32] and SF-36 (Gen-

eral Health, Social Role, Impairment, Emotional Role Im-

pairment) [33] to measure selected domains of function.

These scales were chosen because they are complementary

and responsive to change in depression status. The SF-36

does not capture all functional domains hypothesized to

improve with increased quality of depression care, while the

WHO-DAS-II has not been used in prior randomized trials.

We utilized well-validated, reliable scales to measure

diabetes symptom burden (9 items) [34], diabetes self-effi-

cacy (7 items) [35], and diabetes self-care activities (12

items) [36]. We selected these three scales because they

were shown to have a high correlation with severity of

depression in a prior epidemiologic study [7]. The Diabetes

Symptom Burden Scale inquires about 9 symptoms in the

last month, such as abnormal thirst, and codes the answer on

a Likert Scale of 1 (never) to 5 (qd) [34]. The Diabetes

Self-Efficacy Scale inquires about 7 items, such as how

much control over diabetes the patient believes she or he

has, on a 1 (none at all) to 5 (total control) Likert Scale [35].

The Diabetes Self-Care Activity Scale asks patients to eval-

uate how many of the last 7 days they have followed an

exercise or diet program, checked on their blood sugar level

and completed a foot check. Each answer is coded on a 0

(no days) to 7 (days) Likert Scale [36].

Enrolled patients were asked to agree to blood draws to

measure HbA

1

C at baseline, 6,12 and 24 months and were

reimbursed $25 for their time for each test. Virtually all

enrolled patients were willing to participate in the blood

draws. HbA

1

C measures exposure of red blood cells to

glucose over a 120-day period, and diabetes guidelines

recommend that primary care physicians order this test

twice a year [3]. Lowering HbA

1

C levels has been targeted

in patients with diabetes as a key mechanism to decrease

medical sequelae of poor diabetes control. The Diabetes

Complications and Control Trial demonstrated that inter-

ventions that significantly lowered HbA

1

C levels in patients

with diabetes decreased important medical complications

[37]. Operationally, we required a new HbA

1

C on patients

who had not had one within 14 days of each study scheduled

HbA

1

C.

Group Health’s computerized pharmacy and utilization

records were used to measure adherence to antidepressant

medication, oral hypoglycemic medications as well as am-

bulatory visits and tests and inpatient hospital days and

medical costs. The computerized pharmacy records allowed

examination of refills of antidepressant medications and

whether the patient received an adequate dosage based on

evidence-based guideline standards for 90 days or more

within each 6-month period of time. A recently developed

algorithm for oral hypoglycemic refills also allows measure-

ment of whether or not the patient was overdue in refilling

his or her prescription by 15 or more days and by more than

25% of the intended duration of use [7]. Prior research has

shown that depression is associated with significant gaps in

refills of oral hypoglycemics [7].

Computerized pharmacy records will also be used to

compute a revised chronic disease score (Rx Risk), a mea-

sure of chronic comorbidity based on prescription drug use

over the previous 6 months [38]. After review of the liter-

ature and consultation with diabetes consultants, a diabetes

severity score was developed based on the patient’s self-

rating of the number of complications of diabetes (neurop-

athy, nephropathy, retinopathy and myocardial infarction)

[39] the patient has had, whether the patient’s initial diabe-

tes medication was insulin or an oral hypoglycemic, and the

length of time he or she had diabetes. Both the chronic

disease score and diabetes severity score will be used as

covariates in assessing intervention versus usual care out-

comes. Patients were defined as having Type 1 diabetes

based on an age of onset less than age 30 and on insulin

being their first and current treatment.

Computerized health plan data will be used to identify all

health plan services provided or paid for by Group Health

Cooperative during the 12- and 24-month periods after

randomization (inpatient and outpatient services for mental

health or general medical care). All outpatient and inpatient

services provided by Group Health Cooperative are as-

signed costs based on health plan accounting records (in-

cluding actual personnel, supply and overhead costs). Ser-

vices purchased by GHC from external providers are

assigned costs equal to the amount reimbursed by Group

Health Cooperative for that type of care.

2.12. Data analysis

The study was powered using three different hypothe-

sized differences between Intervention and Usual Care pa-

tients including depressive symptoms, function and HbA

1

C

levels. Based on previous studies in which interventions and

controls had a 0.31 difference on the SCL-20 at 6 months

with a standard deviation for the SCL-20 of 0.7 (an effect

size of approximately 0.4), the study design had 80% power

to detect a 0.23 difference between groups, assuming ran-

domization of 300 patients and 85% patient retention in the

164

W.J. Katon et al. / General Hospital Psychiatry 25 (2003) 158 –168

study at 12 months. Based on previous primary care depres-

sion studies we expected both the SF-36 Social Role Func-

tioning and Emotional Role Functioning Scales to have a

standard deviation of 30. Based on the sample size of 300

and 85% retention, we calculated that we would have 80%

power to detect a 10-point difference in SF-Social or Emo-

tion Role Function scores, which is considered clinically

significant. Based on a recent study of depression and dia-

betes in primary care [7] we assumed a standard deviation

of HbA

1

C levels of 1.65 and a correlation between baseline

and follow-up levels of 0.6 (our actual estimates are

⬎0.7).

With a sample size of 145 in each group we will have 82.2%

power to detect a 0.5 difference between Intervention and

Controls. Given that we expect an 85% follow-up rate at 12

months, we projected needing 162 per group or a total

sample size of 324 to be able to detect a HbA

1

C difference

of 0.5.

The analyses of outcome differences between interven-

tion and control patients will follow an intent-to-treat ap-

proach. We will use random regression models to estimate

effects of the intervention relative to usual care, on the

primary dependent variables: depressive symptoms (contin-

uous SCL-20 outcomes as well as percent achieving recov-

ery based on

ⱖ50% decrease on SCL-20 and the patient

achieving remission based on a score of

⬍5 on PHQ or

⬍0.5 on SCL) and function (WHO-DAS and SF-36 sub-

scales). We will test two interaction terms in the model to

examine possible differences in intervention effects: out-

comes for insulin-dependent versus noninsulin-dependent

diabetics and outcomes for patients with HbA

1

C levels less

than and greater than guideline recommended levels. Pre-

vious studies suggest that depression may have a greater

impact on HbA

1

C levels in insulin-dependent diabetic pa-

tients [40] and change in depression should have the most

benefit in patients with high HbA

1

C levels. We will also use

random regression models to compare intervention versus

usual care effects on important secondary outcomes: diabe-

tes symptom burden, diabetes self-efficacy, diabetes self-

care, and HbA

1

C. In these models, we will adjust for dif-

ferences in patient demographics and clinical characteristics

across intervention and control patients.

2.13. Health care costs and cost effectiveness

We will follow patient costs over a 2-year period after

randomization (the initial patient was randomized on 4/27/

2001 and the last patient was randomized on 5/8/02), Pre-

vious data on health care costs in patients with depression

and diabetes for a 6-month period were estimated at $3,654

⫾ $4,258 in patients with depression and $2,094 ⫾ $3,052

in patients without depression [7]. Methodologic issues ad-

dressed by the skewed distribution of heath care costs in-

clude: using two-part models [41] which first uses logistic

regression to compare the percent of patients utilizing any

health care services. Linear regression techniques are then

used to compare health care costs among users of services.

Methods to correct for possible heteroscedasticity in cost

data such as “smearing” techniques [42] or gamma regres-

sion may be utilized [43]. The randomized trial will have

adequate power to detect a $1,000 reduction in ambulatory

costs per year from a projected base of $5,000 per year. This

reduction is greater than what we expect to observe in the

intervention group. However, descriptive trends in health

care costs in intervention and control groups may be im-

portant. If depression and/or diabetes outcomes were im-

proved without evidence of increased health care costs be-

tween intervention and usual care groups, this would be of

interest. We plan to attempt to obtain a better understanding

of the effect of the interventions on inpatient hospitalization

in two analyses. After controlling for age, gender, chronic

disease score and diabetes severity, we will examine the

effect of the intervention on the number of hospitalizations

using a negative binominal regression model. We will also

examine the effect of the intervention on time to first hos-

pitalization in the first year period using survival models.

Costs and effectiveness of the intervention will be com-

pared with incremental cost-effectiveness ratios following

guidelines developed by Gold and colleagues [44]. We will

take a societal perspective and, in the numerator, will esti-

mate the one-year differences in total ambulatory costs and

time off work due to medical or mental health visits. In the

denominator we will use the method by Lave et al. [45] to

estimate differences in depression free days between inter-

vention and control patients over a 12-month period. Boot-

strap resampling with 1,000 draws using bias correction will

be used to estimate confidence intervals for both incremen-

tal cost measures and depression-free days and the ratio of

incremental costs to incremental depression-free days [46].

The bootstrap method will allow us to document the prob-

ability of this intervention being in each of the four quad-

rants in Fig. 2. Most new interventions are in the upper left

quadrant (costs more, but more effective), however, there is

also a possibility that, if improved depression care is asso-

ciated with improved diabetes care, there may be savings in

medical costs that partially or completely make-up for in-

creased depression costs inherent in the collaborative care

model. Because depression costs are mostly increased in the

first 6 months and medical cost savings may be delayed, we

will carry out follow-ups over a 2-year period.

3. Results

Upon completing enrollment, 330 primary care patients

with diabetes were randomized to the intervention or usual

care conditions. Table 2 presents demographic and clinical

characteristics of the randomized subjects. Approximately

23% of subjects are of minority ethnicity which is higher

that the rates in the Group Health system. This is because of

selecting clinics with high minority rates and the higher

percentage of non-Caucasians with diabetes. A substantial

number of patients have comorbid medical disorders in

165

W.J. Katon et al. / General Hospital Psychiatry 25 (2003) 158 –168

addition to diabetes and are from low socioeconomic status

both of which have been found to be risk factors for poor

depression outcomes [47,48].

The importance of choice in treatment was shown by the

exposure to prior treatment and the actual choices patients

initially made for treatment. Of the 165 patients randomized

to the collaborative care intervention, 48 (29.0%) initiated

treatment with PST only, 65 (39.4%) initiated treatment

with medication only, 48 (29.0%) initiated treatment with

PST and medication (because they were already on an

antidepressant, but still had significant depressive symp-

toms based on a screening PHQ score of

ⱖ10 and baseline

SCL of

ⱖ1.1), and only 4 (2.4%) never initiated treatment.

4. Discussion

The Pathways project has demonstrated the feasibility of

recruiting a population-based primary care sample of pa-

tients with diabetes and depression for an epidemiologic

study and a randomized controlled trial. The mail survey

coupled with telephone reminder calls successfully screened

61.7% of the population. We will be able to compare non-

respondents to respondents on multiple variables in the

GHC database (i.e., prior utilization and costs, medical

comorbidity, HbA

1

C levels) to ascertain respondent bias.

The Pathways intervention offers patients and providers

the necessary resources to increase the use of evidence-

based depression treatments. The nurse collaborative care

model exemplifies a system of care that both supports the

primary care delivery system and provides patient-centered

care. This intervention was modeled from the IMPACT

study where patients in the intervention arm were signifi-

cantly more satisfied with care over the first 3 months than

those treated in usual care [49]. The provision of choice of

treatments may have helped with speed of recruitment and

retention. Many patients had negative feelings about one of

the two treatments. For instance, some patient stated they

were already on multiple medications and wouldn’t take

another, whereas others were not interested in counseling

but agreed to try a medication. Choice mirrors how patients

and providers work together in “real world” systems and

should provide more realistic estimates of the feasibility and

effectiveness of such treatments in primary care.

The stepped care model is more complex than most

treatment protocols and targets scarce mental health re-

Fig. 2. Incremental cost effectiveness quandrant

Table 2

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients with diabetes and

depression

Intervention

N

⫽ 165

Control

N

⫽ 165

Age (mean

⫾ SD)

58.6

⫾ 11.8

58.1

⫾ 12.0

% Female

64.7%

64.7%

% 1 year of college

80.0%

77.6%

% White

75.3%

81.1%

% Employed full- or part-time

53.9%

45.2%

SCL-depression (mean

⫾ SD)

34.15

⫾ 10.2

32.5

⫾ 9.1

% Lifetime dysthymia

67.7%

70.3%

% Major depression

62.8%

69.1%

% Current panic disorder

9.6%

11.9%

Years with diabetes (mean

⫾ SD)

9.6

⫾ 8.7

10.2

⫾ 10.1

Total diabetes symptoms (0–10)

(mean

⫾ SD)

4.6

⫾ 2.6

4.7

⫾ 2.3

HbA

1

C (mean

⫾ SD)

8.1

⫾ 1.6

8.0

⫾ 1.5

166

W.J. Katon et al. / General Hospital Psychiatry 25 (2003) 158 –168

sources to patients with the most persistent symptoms. This

is not a trial of PST versus medication versus usual care;

instead it is a trial of a health services intervention that

provides a choice of evidence-based depression treatments

versus usual care. We will not be able to analyze which

components of this multifaceted intervention are most im-

portant in improving outcomes; however, reviews of

chronic disease interventions that have successfully im-

proved patient-level outcomes have shown that interven-

tions aimed at multiple levels of care, including the patient,

physician and process of care are most effective [50].

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants #MH 4 –1739 and #MH 016473

from the National Institute of Mental Health Services Di-

vision, Bethesda, MD (Dr. Katon).

References

[1] Chipkin SR, Gottlieb P, Bogorad DD, Parker F. Diabetes mellitus. In:

Noble J, editor. Textbook of primary care medicine. 2

nd

ed. St. Louis,

Mosby-Yearbook, 1996, p. 476 – 498.

[2] Lustman P, Clouse R, Freedland K. Management of major depression

in adults with diabetes: implications of recent trials. Sem Clin Neu-

ropsych 1998;3:102–114.

[3] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes aware-

ness month, Nov 1997, MMWR, Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 46:1013,

1997.

[4] American Diabetes Association, Direct and indirect costs of diabetes

in the United States in 1992, Alexandria, VA, 1992.

[5] Gavard JA, Lustman PJ, Clouse PE. Prevalence of depression in

adults with diabetes. An epidemiologic evaluation. Diabetes Care

1992;16:1167–78.

[6] de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland K, et al. Association of depres-

sion and diabetes complications: meta-analysis. Psychosom Med

2001;63:619 –30.

[7] Anderson R, Freedland K, Clouse R, Lustman P. Prevalence of

comorbid depression in adults with diabetes. A meta-analysis. Dia-

betes Care 2001;24:1069 –78.

[8] Lustman PJ, Anderson R, Freedland K, et al. Depression and poor

glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes

Care 2000;23:934 – 42.

[9] Winokur A, Maislin G, Phillips J, Amsterdam J. Insulin resistance

after glucose tolerance testing in patients with major depression. Am J

Psychiatry 1988;145:325–30.

[10] DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor

for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the ef-

fects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med

2000;160:2101–7.

[11] Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Clouse RE, et al. Effects of nortriptyline on

depression and glucose utilization in diabetes: results of a double-

blind placebo controlled trial. Psychosom Med 1997;59:241–50.

[12] Lustman PJ, Freedland KE, Griffith LS, Clouse RE. Fluoxetine for

depression in diabetes: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled

trial. Diabetes Care 2000;23:618 –23.

[13] Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Freedland KE, et al. Cognitive behavior

therapy for depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized

controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:613–21.

[14] Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, et al. Collaborative management

of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:1097–1102.

[15] McCulloch D, Price M, Hindmarsh M, Wagner E. A population-

based approach to diabetes management in a primary care setting:

early results and lessons learned. Eff Clin Pract 1998;1:12–22.

[16] Walker E, Unutzer J, Rutter C, et al. Costs of health care use by

women HMO members with a history of childhood abuse and neglect.

Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56:609 –13.

[17] Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief

depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606 –13.

[18] Robins L, Helzer J. Diagnostic interview schedule (DIS): version

III-A. St Louis, MO, Washington University School of Medicine,

1985.

[19] Derogatis L, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth E, Coui C. The Hopkins Symptom

Checklist: a measure of primary symptom dimensions. In: Pichot

(editor), Psychological measurement in psychopharmacology: prob-

lems in psychopharmacology. Basel, Switzerland: Kargerman, 1974,

p. 79 –110.

[20] Simon G. Evidence review: efficacy and effectiveness of antidepres-

sant treatment in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2002;24:213–24.

[21] Unu¨tzer J, Katon W, Williams J Jr, et al. Improving primary care for

depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial.

Med Care 2001;39:785–99.

[22] Ward E, King M, Lloyd M, et al. Randomized trial of nondirected

counseling, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and usual general practitio-

ner care for patients with depression. clinical effectiveness. BMJ

2000;321:1383– 88.

[23] Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health

system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C., National Academy

Press, 2001.

[24] Mynors-Wallis L, Gath D, Lloyd-Thomas A, Tomlinson D. Random-

ized controlled trial comparing problem solving treatment with ami-

triptyline and placebo for major depression in primary care. BMJ

1995;310:441–5.

[25] Unu¨tzer J. The IMPACT study investigators: IMPACT intervention

manual. Los Angeles, CA, Center for Health Services Research,

UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute, 1999.

[26] Hegel MT, Barrett JE, Oxman TE Problem-solving treatment for

primary care (PST-PC): A treatment manual for depression, Hanover

NH: Dartmouth University, 1999.

[27] Hegel MT, Barrett JE, Oxman TE. Training United States therapists

in problem-solving treatment of depressive disorders in primary care

(PST-PC): lessons learned from the treatment effectiveness project.

Families Systems Health 2000;18(4):423–35.

[28] Pendragon Forms, Version 3.2. Pendragon Software Corporation,

Libertyville, IL 60048. www.Pendragonsoftware.com.

[29] Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G. Rethinking practitioner

roles in chronic illness: the specialist, primary care physician, and the

practice nurse. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2001;23:138 – 44.

[30] Katon W, Von Koff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to

achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care.

JAMA 1995;273:1026 –31.

[31] Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al. A multi-faceted interven-

tion to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen

Psychiatry 1996;53:924 –32.

[32] Epping-Jordan J, Chatterji S, Ustun T. The World Health Organiza-

tion. Disability assessment schedule II (WHO-DAS II) a tool for

measuring clinical outcomes. Presented at NIMH Health Services

Research Meeting. Washington, D.C., July 2000.

[33] Ware J, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item Short Form Health Survey

(SF-36). Med Care 1992;30:473– 83.

[34] Whitty P, Steen N, Eccles M, et al. A new completion outcome

measure for diabetes: is it responsive to change? Qual Life Res

1997;6:407–13.

[35] Carey MP, Jorgenson RS, Weinstock, et al. Reliability and validity of

the appraisal of diabetes scale. J Behav Med 1991;14:43-51.

[36] Toobert D, Hampson S, Glascow R. The summary of the Diabetes

Self-Care Activities Measure: results from 7 studies and a revised

scale. Diabetes Care 2000;23:943–50.

167

W.J. Katon et al. / General Hospital Psychiatry 25 (2003) 158 –168

[37] The DCCT Research Group. Influence of intensive diabetes treatment

on quality-of-life outcomes in the Diabetes Control and Complica-

tions Trial. Diabetes Care 1996;19:195–203.

[38] Fishman P, Goodman M, Hornbrook M. Risk adjustment using auto-

mated pharmacy data: the Rx Risk Model. Med Care 2003;41:84 –99.

[39] Jacobson A, de Grout M, Samson J. The effects of psychiatric dis-

orders and symptoms on quality of life in patients with type 1 and

type 2 diabetes mellitus. Qual Life Res 1997;6:11–20.

[40] Ciechanowski P, Katon W, Russo J, Hirsch I. The relationship of

depressive symptoms to symptom reporting, self-care and glucose

control in diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychatry (In Press).

[41] Diehr R, Yanez D, Ash A, et al. Methods for analyzing health care

utilization and costs. Ann Rev Public Health 1999;20:125–144.

[42] Duan N. Smearing estimate: a nonparametric retransformation

method. J Am Statistical Assoc 1983;78:605–10.

[43] Manning WG. The logged dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, and

the retransformation problem. J Health Econ 1998;17:283–95.

[44] Gold M, Siegel J, Russel L, et al. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and

Medicine. New York, NY, Oxford University Press, 1996.

[45] Lave J, Frank R, Schulberg H, Kamlet M. Cost-effectiveness of

treatments for major depression in primary care practice. Arch Gen

Psychiatry 1998;55:645–51.

[46] O’Brien B, Drummond M, Labelle R, Williams A. In search of

power and significance: issues in the design and analysis of sto-

chastic cost-effectiveness studies in health care. Med Care 1994;

32:150 – 63.

[47] Weich S, Churchill R, Lewis G, et al. Do socioeconomic factors

predict the incidence and maintenance of psychiatric disorders in

primary care. Psychol Med 1997;27:73– 80.

[48] Cole M, Bellavance F, Mansour A. Prognosis of depression in elderly

community and primary care populations: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1182–9.

[49] Unu¨tzer J, Katon W, Williams J Jr, et al. The IMPACT trial: collab-

orative care management improves treatment and outcomes of late-

life depression. JAMA 2002;288:2836 – 45.

[50] Haynes R, McDonald H, Garg A, Montague P. Interventions for

helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2002;(2):CD00011.

168

W.J. Katon et al. / General Hospital Psychiatry 25 (2003) 158 –168

Document Outline

- Improving primary care treatment of depression among patients with diabetes mellitus: the design of the Pathways Study

- Introduction

- Methods

- Study setting

- Sample recruitment

- Methodology of the Pathways randomized controlled trial

- Randomization

- Intervention design

- What type of professional should be trained as a Depression Care Specialist (DCS)

- Training

- Collaborative care

- Stepped care algorithm

- Usual care

- Evaluation

- Data analysis

- Health care costs and cost effectiveness

- Results

- Discussion

- Acknowledgments

- References

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Leczenie depresji - farmakologia, LECZENIE DEPRESJI:

cukrzyca, LECZENIE NIEFARMAKOLOGICZNE PACJENTÓW Z CUKRZYCĄ, LECZENIE NIEFARMAKOLOGICZNE PACJENTÓW Z

depresja w ciazy z leczeniem

Depresja zimowa epidemiologia, etiopatogeneza, objawy i metody leczenia

LECZENIE CUKRZYCY II

Stopa cukrzycowa rozpoznanie i leczenie mp pl

Standardy leczenia cukrzycy

LECZENIE DEPRESJI

FARMAKOLOGIA wykład 07, FARMAKOLOGIA wykład 7 (26 XI 01) LECZENIE CUKRZYCY cz

LECZENIE DEPRESJI

Światło spolaryzowane w leczeniu stopy cukrzycowej opis przypadku

Leki wspomagajce leczenie cukrzycy

leczenie otyłości i cukrzycy monograf 2009

Problemy leczenia dzieci z cukrzycą

Leczenie cukrzycy

Cukrzyca typu 2 leczenie

więcej podobnych podstron