The new European Union (EU) law on chemicals and their safe use, known as

REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals), came

into effect on the 1

st

June 2007. The aims of this new law are to improve the

protection of human health and the environment from the risks that can be posed

by chemical substances, to promote alternative safety testing methods and to

improve the safe handling and use of substances across all sectors of industry.

A switch in responsibility

Prior to REACH, regulatory bodies were largely responsible for evaluating the risks posed

by chemicals and providing safety information on substances. Under the new EU law, that

responsibility now lies within industry.

Manufacturers and importers of chemicals must now collate information on the properties

of their chemical substances and register this information as of 1

st

June 2008 into a

central database managed by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), based in Helsinki.

Safety information about a registered chemical on the database can then be accessed by experts as well as the general public,

improving the safe handling and use of the substance. Furthermore, under this new system, manufacturers will be able to

check for what uses a particular substance has been registered as being safe, enabling them to replace any substances

recognised as being unsafe with a safer alternative.

Increased safety

As well as improving the protection of human health and the environment from the risks that can be posed by chemical

substances, and improving the safe handling and use of substances across all sectors of industry, the REACH regulations also

aim to promote alternative safety testing methods, stating that the development of alternatives should be prioritised in future

EU research. Once alternative testing methods which do not involve the use of animals have been validated, the REACH

regulations will be adapted to phase out animal testing as soon as possible.

Implications of REACH

In the EU, health and safety tests on chemicals did not become mandatory until 1981. As a consequence, under the new

REACH regulations, over 100,000 substances placed on the market prior to 1981 will have to be registered onto the new

database. Consequently, over the next 10 years thousands of preexisting and new chemicals will be registered by the ECHA

as the new REACH regulation is slowly phased in.

Companies that manufacture or import 1 tonne or more of any chemical substance per year, or who expect to do so over the

REACH timings should preregister the substance with the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) between 1

st

June and 1

st

December 2008. Failure to meet this deadline means that they cannot continue producing or importing the substance until they

have submitted a full registration dossier. With preregistration, companies can benefit from staggered registration deadlines

depending on the substance and the tonnage (2010, 2013 or 2018).

REACH does not require that all chemicals be registered. The use of substances in some sectors of industry, such as the food

industry, have been exempted as they are already covered by other EU laws. For instance, food ingredients, which are already

covered by the EU General Food Law Regulation 178/2002, do not have to be registered under the new REACH legislation.

However, the use of other substances in the food industry such as in packaging and in cleaning materials does.

Measurement of impact

In time, the impact of REACH on the food industry sector will be evaluated by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the

forefront of EU food safety risk assessment. It is possible that the initiation of REACH may result in a change in how risks in the

food industry are assessed at the European level.

Implications for consumers

For the consumer, the implications of the REACH system will develop gradually as more and more chemicals are phased into

the new law. It is hoped that the registration of substances and their safe use will reassure those consumers who may be

concerned about product safety, and that the replacement of chemicals with safer alternatives will improve the safety of both

human health and the environment.

References

1.

Food Quality News, News articles section

2.

European Commission, Chemicals section:

3.

European Chemicals Agency, Publications section

New European Union law REACH regulating the use of chemical substances

Physical activity is related to health and lifestyle status and should be part of

everyone’s daily routine. With growing rates of obesity and its associated health

problems, physical activity is now more important than ever.

It is well known that the amount and type of exercise that an individual takes part in plays

a significant role in health and weight. Excess body fat is harmful to the body in that it puts

more strain on the joints and surrounding tissues, and it increases the risk of certain

cancers (including bowel, breast and kidney cancer), diabetes and heart disease.

Consequently, those individuals who exercise regularly can not only maintain a healthier

weight but also reduce their risk of developing chronic diseases and have healthier bones

and joints.

Healthy body weight

Body weight can be categorised into underweight, normal, overweight or obese based on

the Body Mass Index (BMI). The BMI is calculated by dividing body weight (kg) by the

square of body height (m

2

). For example, an individual who is 1.82 m tall and weighs 75

kg will have a BMI of 75/(1.82)

2

= 22.64 kg/m

2

. This figure is then used to assess where

the individual sits on a scale of body sizes.

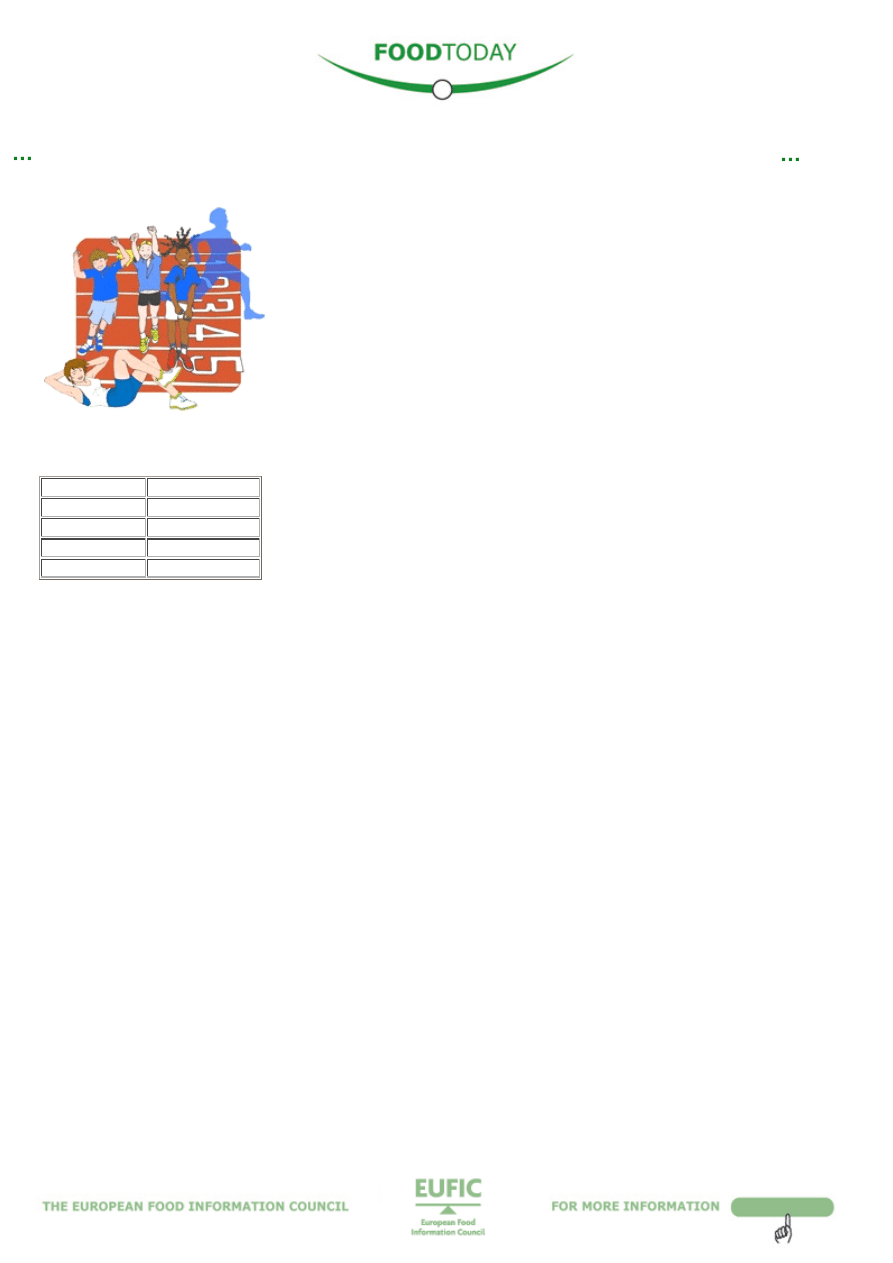

The categories of BMI for adults are as follows:

An important point to remember when using BMI is that it does not take into account how much of the individual is muscle or

fat. Those who are physically fit with a large amount of muscle mass could in fact be classified as obese while their higher

weight is actually due to having more muscle as opposed to high levels of body fat. Researchers tend to agree that body fat

rather than total weight is a better indicator of health status and disease risk. That is why the BMI can be complemented by

measuring waist circumference, which gives an indication of abdominal body fat. Abdominal fat is closely related to various

diseases. The higher the amount of abdominal fat, the higher the risk of getting type II diabetes, hypertension (increased

blood pressure) and coronary heart disease. A healthy male should have a waist circumference below 102 cm whilst a healthy

female should have a waist circumference below 80 cm.

Adipose tissue and physical activity

Adipose tissue is made of fat cells. Due to hormonal influences, males are more likely to accumulate excess body fat around

their waist area, whereas females are more likely to store excess fat in a thin layer under the skin and in the hip and thigh

regions. The more excess body fat that is accumulated, particularly around the waistline, the higher an individual’s risk of

developing health problems.

The physical activity level (PAL) of an individual is calculated as the ratio of their total energy expenditure and their resting

energy expenditure over the course of a day (24 hours). In short, the more active an individual, the higher their PAL. A low

PAL is defined as <1.49, a medium PAL is ~1.5 and a high PAL is >1.9.

Being involved in vigorous physical activity is clearly linked to weight stability.

1,2

Vigorous exercise is any type of exercise

which elevates the heart rate and breathing rate (feeling out of breath) and requires a substantial effort. Examples of vigorous

activities are: running, fast cycling, aerobics and competitive sports such as football, hockey, and volleyball.

Children and adolescents who participate in relatively large amounts of physical activity have lower levels of body fat than

those who do not.

3,4

European children aged 910 years who engaged in vigorous physical activity for more than 40 minutes a

day had lower levels of body fat than those who only engaged in 1018 minutes of vigorous physical activity a day.

2

Studies suggest that a PAL of ~1.8 is needed for minimising any weight gain.

1

This PAL of 1.8 is consistent with moderate

activity, i.e., predominantly standing or walking work such as that seen with housewives, salespersons, waiters, mechanics,

and traders.

5,6

To equate this with the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendation of 30 minutes of physical activity on

most days of the week, most individuals need to include some extra physical activity in their day. Those who vigorously

exercise will have a higher PAL as they are expending more energy.

In contrast, it has been shown that low and medium PALs are significantly related to an increase in body fat in both males and

females. Accordingly, an individual may need 6090 minutes of walking (briskly) or an equivalent amount of activity a day to

expend enough energy for weight stability.1 Although reducing calorie intake may also help maintain energy balance, it does

not provide the health benefits associated with physical activity.

In conclusion

To reduce levels of body fat and to get the health benefits seen in those who exercise regularly, we should try to make

physical activity a part of everyday living. The WHO recommends at least 30 minutes of regular, moderateintensity physical

The link between intense physical activity and a healthy body weight

BMI

Category

< 18.5

Underweight

18.5 – 24.9

Normal

25 – 29.9

Overweight

30+

Obese

3

activity on most days to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, colon cancer and breast cancer.

7

More activity

may be required for weight control.

To provide a greater understanding of the important roles played by energy intake and expenditure, EUFIC has developed a

new Energy Balance section on its website where you can learn about your specific energy and physical activity needs.

www.eufic.org/block/en/show/energybalance/

References

1. Erlichman J, Kerbey AL, James WP. (2002). Physical activity and its impact on health outcomes. Paper 2: Prevention of

unhealthy weight gain and obesity by physical activity: an analysis of the evidence. Obesity Reviews 3:273287.

2. Ruiz JR, Rizzo NS, HurtigWennlöf A, Ortega FB, Wärnberg J, Sjöström M. (2006). Relations of total physical activity and

intensity to fitness and fatness in children: the European Heart Health Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 84

(2):299303.

3. Ekelund U, Sardinha LB, Anderssen SA, Harro M, Franks PW, Brage S, Cooper AR, Andersen LB, Riddoch C, Froberg K.

(2004). Associations between objectively assessed physical activity and indicators of body fatness in 9 to 10yold

European children: a populationbased study from 4 distinct regions in Europe (the European Youth Heart Study).

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 81(6):1449–50.

4. Gutin B, Humphries MC, Barbeau P. (2005). Relations of moderate and vigorous physical activity to fitness and fatness

in adolescents. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 81(4):746 –50.

5. Black AE, Coward WA, Cole TJ, Prentice AM. (1996). Human energy expenditure in affluent societies: an analysis of 575

doublylabelled water measurements. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 50:72–92.

6. German Nutrition Society, Austrian Nutrition Society, Swiss Society for Nutrition Research, Swiss Nutrition Association.

(2002). Reference values for nutrient intake. Frankfurt/Main: Umschau/Braus: German Nutrition Society.

7.

http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/pa/en/index.html

4

Cholesterol often gets a bad press and, in a way, that is right because a high

level of bad cholesterol in your blood is a major risk factor for heart disease. A

healthy balanced lifestyle and diet can help reduce the risk of heart disease, but

cholesterol also plays a vital role in keeping the body healthy.

What is cholesterol?

Cholesterol is a waxlike substance, which together with fats and oils belongs to the family

of lipids. It is essential to all our body cells and has a special role in the formation of brain

cells, nerve cells and certain hormones. Although some foods contribute readymade

cholesterol, the majority of cholesterol in the body is manufactured by the liver.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has estimated that amongst Europeans the average

total cholesterol levels in men vary from 4.5 mmol/l (millimoles per litre) in Turkey to 6.2

mmol/l in Serbia and Montenegro, and in women, average total cholesterol levels range

from 4.6 mmol/l in Turkey to 6.1 mmol/l in Norway.

1

For most people, the recommended

total cholesterol level is <5.0 mmol/l, but for people who already have some degree of cardiovascular disease, this

recommended level is <4.5 mmol/l.

2

Cholesterol and Health

Too much cholesterol in the blood (hypercholesterolaemia) is a major risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD), which can

lead to a heart attack or stroke. Together, these are the main cause of death in Europe.

3

There are two main types of cholesterol: low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and high density lipoprotein (HDL)

cholesterol.

LDL cholesterol, often referred to as ‘bad’ cholesterol, carries fat around the body and is big, fluffy and sticky. If circumstances

are favourable, LDL cholesterol gets stuck in the walls of the arteries making them narrower (a process called atherosclerosis).

Such changes, in turn, lead to a higher tendency of the blood to clot. If a clot (thrombus) forms and blocks the narrowed artery

(thrombosis), this can result in a heart attack or stroke. Although LDL is made naturally by the body, some people make too

much. The diet can also affect the amount of LDL cholesterol.

HDL cholesterol, or ‘good’ cholesterol, scavenges for fat and returns it to the liver. Having plenty of HDL cholesterol means that

fatty deposits are less likely to build up in the arteries. A high HDL:LDL ratio, i.e. high levels of HDL cholesterol relative to LDL

cholesterol, protects against heart disease. Being physically active and eating healthier fats can help to raise HDL cholesterol

levels.

Diet, lifestyle and cholesterol

There are several factors that influence blood cholesterol levels. Eating a balanced diet, being of healthy weight and keeping

physically active, in particular, can help to keep cholesterol levels normal.

Dietary cholesterol

Some foods (eggs, liver, kidney and prawns) naturally contain cholesterol (dietary cholesterol). The cholesterol found in foods

in most cases does not influence blood cholesterol levels as much as the amount and type of fat eaten, but some people might

be sensitive to high cholesterol intakes.

Dietary fats

Dietary fat is often divided into saturated and unsaturated fat. In general, most types of saturated fat raise total and LDL

cholesterol levels. Saturated fats are found in butter, lard (and foods made from these including pastries, cakes and biscuits),

meat products (e.g., salami, pies and sausages), cream, cheese and foods containing coconut or palm oils. Some unsaturated

fats can help reduce LDL cholesterol levels, and generally it is a good idea to replace saturated fats with unsaturated fats.

Foods containing unsaturated fats include vegetable and seed oils and spreads (e.g., rapeseed oil, olive oil, soya spread), oily

fish (e.g., mackerel, salmon and herring), nuts and avocado.

Another type of fat, trans fat, is sometimes found in foods that contain partially hydrogenated fats (e.g., some pastry and

biscuits), although many companies in Europe have reduced levels of trans fats in their products to a minimum. Trans fats can

raise LDL (bad) cholesterol levels. Unlike saturated fats, trans fats also lead to a fall in HDL (or good) cholesterol and raise

blood triglyceride levels, both of which are associated with an increased risk of CHD. These negative effects may occur with

longterm intakes of trans fats of 510 g per day.

4,5

Apart from consuming the right fats, it is sensible to try to reduce the amount of fat overall as well, by baking, grilling, boiling,

poaching or steaming foods instead of frying them, and cutting down on foods that are high in fat. Look at the nutrition

information on food labels to compare the fat types and levels, especially saturated fats, in products.

A ‘portfolio’ of foods

In addition to the type of fat we eat, other foods can also help to keep cholesterol levels healthy. Eating plenty of fruits and

vegetables, foods containing soluble fibre (e.g., oats, lentils, beans and peas), tree nuts (e.g., almonds) and soya can be

useful. Note that products on the market containing added plant stanols or plant sterols are designed for people who have

excessive cholesterol levels and are not necessary for people with healthy cholesterol levels. Scientists have found that eating

a healthy lowfat diet, including a ‘portfolio’ of the foods mentioned above, can reduce cholesterol levels by up to 20%.

6

References

Cholesterol: the good, the bad and the average

5

1. WHO (2006). WHO global infobase online. Available at:

http://www.who.int/infobase/report.aspx?

2. Policy Analysis Centre (2007). European Cholesterol Guidelines Report.

Available at:

http://www.policycentre.com/downloads/EuropeanCholesterolGuidelines07.pdf

3. European cardiovascular disease statistics; 2008 edition. European Heart Network, Brussels, 2008.

Available at:

http://www.ehnheart.org/ files/EU%20stats%202008%20final155843A.pdf

4. Hunter JE. (2006). Dietary trans fatty acids: review of recent human studies and food industry responses. Lipids 41

(11):96792.

5. Stender S, Dyerberg J, Astrup A. (2006). High levels of trans fat in popular fast foods. New England Journal of Medicine

354:16501652.

6. Jenkins DJA, Kendall CWC, Marchie A, Faulkner DA, Wong JMW, de Souza R, Emam A, Parker TL, Vidgen E, Trautwein

EA, Lapsley KG, Josse RG, Leiter LA, Singer W, Connelli PW. (2005). Direct comparison of a dietary portfolio of

cholesterol lowering foods with a statin in hypercholesterolemic participants. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

81:3807

6

Parents’ lack of money, time for cooking, and motivation are some of the

important barriers to achieving a healthy diet in children. Similarly, lack of sports

facilities, intolerant neighbours, and not having a garden can act as barriers to

being more physically active. These are the first results of the European IDEFICS

study (Identification and Prevention of Dietary and LifestyleInduced Health

Effects in Children and Infants).

Contributing to the prevention of childhood obesity in Europe

Childhood obesity and its related health problems are an increasing phenomenon in

Europe. Consequently, the IDEFICS study was set up to improve knowledge about dietary

factors, social environment, and lifestyle affecting children’s health in Europe. This

knowledge will be used to develop, implement, evaluate, and validate specific

interventions for reducing the prevalence of diet and lifestylerelated diseases.

As part of the IDEFICS study, focus groups were held at the child and parent level in eight

countries to gain insight into the factors that affect children’s nutrition and physical

activity. The focus groups’ participants comprised:

l

155 children aged 68 years (81 boys, 74 girls) split into 20 groups of 517 participants

l

106 parents of 24 year old and 83 parents of 68 year old children (28 men, 161 women) split into 36 groups of 512

participants

Barriers to a healthy diet

Not enough time for cooking, lack of money, limited motivation, little time available to spend with the children (to control what

they are eating), grandparents breaking food rules, and the wide availability of energydense, nutrientpoor foods were among

the factors mentioned that can hamper children eating healthily. Lowincome families are more likely to have diets that are

less healthy, where shopping is more influenced by price and taste preferences of the children and food choice rules are less

strict. There are large differences between countries in school rules on food consumption. Sweden has strict and clear rules,

nutritious meals are provided to children and vending machines are regulated. The absence of clear rules is, however,

common in other countries. Generally, there is a lack of nutrition education (except for Belgium and Spain), and eating fruit at

school is not facilitated.

Barriers to physical activity

Common environmental barriers include the lack of facilities, such as playgrounds, gyms, sporting grounds, swimming pools,

green spaces or cycle lanes, as well as safety issues that include too much traffic, the presence of teenage gangs, no or

unclear traffic signs and bad condition of cycle lanes and footpaths. Conditions at school, although variable from country to

country, are not optimal either, due to too short breaks and lack of space to play.

Lack of organised activities for younger children and lack of sports organisations contribute to children doing little physical

activity. Lowincome families regarded the price of doing sports in a sports club as a major obstacle, although they would see

the participation of their children in organised activities as a way to keep them in a safe environment. Generally, the children

were more active during spring and summer.

Tearing down the barriers

Parents most often perceive school as an important facilitator for healthy diet and lifestyles. This is due to the fact that children

spend a significant amount of daytime at school. Nutrition education should thus be included since children from all socio

economic classes could be reached this way. It is also necessary to have a well elaborated and consistent school food policy

that is endorsed by the parents. This is important as parents need to become more aware of their responsibility for improving

their children’s diet and lifestyle.

Environmental changes like the creation of trafficfree zones, or safe streets with footpaths and cycle lanes will help increase

physical activity in children. Organising affordable activities for children will not only take them away from sedentary lifestyles,

but also keep them out of trouble, especially in lowincome families. Schools should make appropriate accommodation and

sports materials available, include active breaks, organise extracurricular activities, and motivate teachers to act as role

models. In Sweden, day care schools already offer such activities for younger children during and after school hours, and in

Hungary schools open their playgrounds for families to do sports activities together. Playing together is highly motivating for

children to go outdoors and be active.

The IDEFICS study continues

The results of the focus groups have been used to develop a communitybased lifestyle strategy that addresses nutrition and

physical activity interventions and is centred around primary and nursery schools. The nutrition intervention will include

education as well as training to develop cooking and shopping skills. For the intervention on physical activity, structured

activities and an environment that supports activity both at school and in the community will be necessary. Improving safety in

the neighbourhood, and largescale actions such as increasing the number of playgrounds or parks or family days, should be

part of a community programme and the focus of negotiations with community leaders. Finally, a healthy parental lifestyle

supporting physical activity and the availability of healthy foods will contribute to a healthier diet and higher activity levels in

their children.

Further information:

Breaking barriers to healthy food choice and physical activity in young

children

7

References

1. Ahrens W, Bammann K, de Henauw S, Halford J, Palou A, Pigeot I, Siani A, Sjostrom M. (2006) Understanding and

preventing childhood obesity and related disorders—IDEFICS: A European multilevel epidemiological approach.

Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 16(4):302308.

2. Identification and prevention of Dietary and lifestyleinduced health EFfects In Children and infantS (IDEFICS).

European Commission Sixth Framework Programme. Contract n° 016181 (FOOD)

.

3. Haerens L, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Barba G, Eiben G, Fernandez J, Hebestreit A, Konstabel K, Kovács É, Lasn H, Regber S,

Shiakou M, De Henauw S, on behalf of the IDEFICS consortium (in press). Developing the IDEFICS community based

intervention program to enhance eating behaviors in 28 year old children: findings from focus groups with children and

parents. Health Education Research.

4. Haerens L, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Eiben G, Barba G, Bel S, Keimer K, Kovács E, Lasn H, Regber S, Shiakou M, Maes L on

behalf of the IDEFICS consortium (submitted). Formative research to develop the IDEFICS physical activity intervention

component: findings from focus groups with children and parents. IJBNPA.

5. EUFIC Food Today n°58 (May 2007) Learning Healthy Living – Development of a European Prevention Strategy.

Available at:

www.eufic.org/article/en/artid/Learnhealthylivingeuropeaninterventionstrategy/

8

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

FOOD TODAY #62 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #77 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #71 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #90 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #64 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #66 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #75 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #80 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #73 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #91 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #86 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #83 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #69 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #70 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #74 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #56 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #84 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #67 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #79 EUFIC

więcej podobnych podstron