On request from the European Commission, the European Food Safety Authority has

provided guidance on intakes of fats, carbohydrates, fibre and water considering the new

evidence. These dietary reference values establish optimum intakes of nutrients in a

balanced diet which when part of an overall healthy lifestyle, contribute to good health.

Update in progress

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) is currently updating the dietary reference values (DRVs)

published in 1993.

1

This will provide comprehensive nutrition guidelines, for example for food labelling

and for setting public health targets in Europe. After extensive consultation with Member States, the scientific community and

other stakeholders, DRVs for fats, carbohydrates, dietary fibre and water have been published.

2

Those for energy, protein,

vitamins and minerals are still in the pipeline.

Chronic disease considered

In the past, recommended daily intake values were aimed primarily at preventing specific nutrient deficiencies. In recent

decades it has become clear that the nutrient makeup of the diet has a profound impact on the development of chronic

diseases like cancer, diabetes, osteoporosis and heart disease, and therefore on longterm health. This is why DRVs now

include recommendations on intakes for nutrients like carbohydrates, fibre and fats.

Carbohydrate range

Moving away from specific values, EFSA has instead given an acceptable range of carbohydrate intake (sugars and starchy

carbohydrates combined), known as a reference intake range. Diets containing between 4560% of daily energy from

carbohydrates, combined with reduced fat and saturated fat intake, improve metabolic risk factors for chronic disease.

3

No

specific intake or upper limit for intake of total sugars or added sugars is set as available evidence was found insufficient to

link high sugar intakes with weight gain, micronutrient deficiencies or tooth decay. Appropriate oral hygiene measures with

fluoridated toothpaste contribute to caries prevention.

Fibre threshold

The recommendation for fibre intake has been based upon the amount needed to keep the bowels functioning correctly. This

acceptable intake is 25g per day.

3

However, there is evidence that consuming fibrerich foods such as wholegrain cereals,

fruits and vegetables, providing more than 25g of fibre per day, aids weight control and reduces the risk of heart disease and

type 2 diabetes. It is recommended that this is taken into consideration when setting food based targets.

Fat range

The EFSA also decided to set a reference intake range for fat of between 20 and 35% of total daily energy intake.

4

Within this

range, based on observations of dietary intakes, no overt nutritional deficiencies or adverse effects on blood fats or body

weight have been observed. It is also pointed out that higher fat intakes can still be compatible with both good health and

normal body weight, depending on the type of foods eaten and physical activity levels. Saturated fats should be kept as low as

possible within the context of a nutritionally adequate diet as well as trans fats, which are not required by the body. No specific

levels of mono and polyunsaturated fats are given except that they should replace saturated fats where possible. The omega

3 long chain fatty acids, found in oily fish, are of specific benefit to heart health and an adequate intake of 250mg per day was

set. As little as a mean daily intake of 20 grams of salmon would provide this quantity.

5

Water

Sufficient water is vital for practically all functions of the body and in particular for regulating body temperature. A loss of 10%

of body water can be fatal. Water intakes vary; the more physical activity and the hotter the environment, the more fluid is

needed. EFSA set an adequate intake, assuming moderate activity and external temperature, of 2 litres per day for women

and 2.5 litres per day for men.

6

This includes water from all drinks and from food.

Foodbased advice

To be of help to consumers, the DRVs need to be translated into useful advice about what foods to eat, and in what quantities

and proportions. Such foodbased dietary guidelines need to take into account cultural differences in food intake in a region or

country, be practical to implement, and provide straightforward advice about dietary patterns that will maintain good health

and prevent dietrelated diseases.

7

Uncertainties still exist on deciding what are optimum dietary intakes of carbohydrates

(especially sugar), fibre and fats. Therefore, we can expect changes to these guidelines in the future as better evidence of the

relationship between diet and health develops.

References

1. Reports of the scientific committee for food (1993). 31st series. Nutrient and energy intakes for the European

community. European Commission. Luxembourg. Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/food/fs/sc/scf/out89.pdf

2. EFSA sets European dietary reference values for nutrient intakes. Available at:

http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/press/news/nda100326.htm?wtrl=01

3. EFSA panel on dietetic products, nutrition and allergies (2010) Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for

carbohydrates and dietary fibre. EFSA Journal 8(3):1462. Available at:

http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/1462.htm

4. EFSA panel on dietetic products, nutrition and allergies (2010) Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for fats,

including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids and

New nutrition guidelines for Europe, halfway there…

cholesterol. EFSA Journal 8(3):1461. Available at:

http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/1461.htm

5. Food Standards Agency (2002). McCance and Widdowsons’s The Composition of Foods, 6th summary edition.

Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry.

6. EFSA panel on dietetic products, nutrition and allergies (2010) Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for water.

EFSA Journal 8(3):1459. Available at:

http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/1459.htm

7. EFSA panel on dietetic products, nutrition and allergies (2010) Scientific opinion on establishing foodbased dietary

guidelines. EFSA Journal 8(3):1460. Available at:

http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/1460.htm

2

Eggs are a rich source of protein and several essential nutrients. Emerging evidence suggests

that eating eggs is associated with improved diet quality and greater sense of fullness after

meals, and may be associated with better weight management. In addition, substances found

in egg yolk may help to prevent agerelated loss of sight. Recent farm improvements have

raised standards in the safety of eggs, with reductions in Salmonella contamination seen in

many parts of Europe.

Little impact on blood cholesterol

In the past, there were concerns that consuming eggs and other cholesterolrich foods could raise blood

cholesterol levels, thereby increasing the risk of heart disease. However, dietary cholesterol in most

cases does not influence blood cholesterol levels as much as the amount and type of fat eaten, except in

some people who are sensitive to high cholesterol intakes. Current evidence suggests that egg consumption as part of a

healthy balanced diet will not significantly increase blood cholesterol levels in the majority of people. Studies looking at dietary

causes of heart disease have found no link with regular egg consumption (up to six eggs per week), even in people with pre

existing high cholesterol levels.

1,2

Other health aspects

High protein foods are known to boost satiety (the feeling of fullness experienced after eating) and this had led scientists to

investigate whether eggs have a role in satiety and weight management. Two controlled trials reported that eating eggs for

breakfast can promote feelings of satiety and lower daily calorie intake.

3,4

One study found that eating eggs for breakfast at

least 5 days/week for eight weeks enhanced weight loss in overweight subjects on a reducedcalorie diet compared to an

energymatched bagel breakfast.

5

The carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin, found in large amounts in egg yolk, are believed to help cut the risk of agerelated

macular degeneration, a major cause of blindness in older people. One study revealed that eating six eggs weekly for 12

weeks raised blood zeaxanthin levels and increased the optical density of the macular pigment.

6

A higher optical density of the

macular pigment may help reduce the stress of sunlight to the eye (photostress).

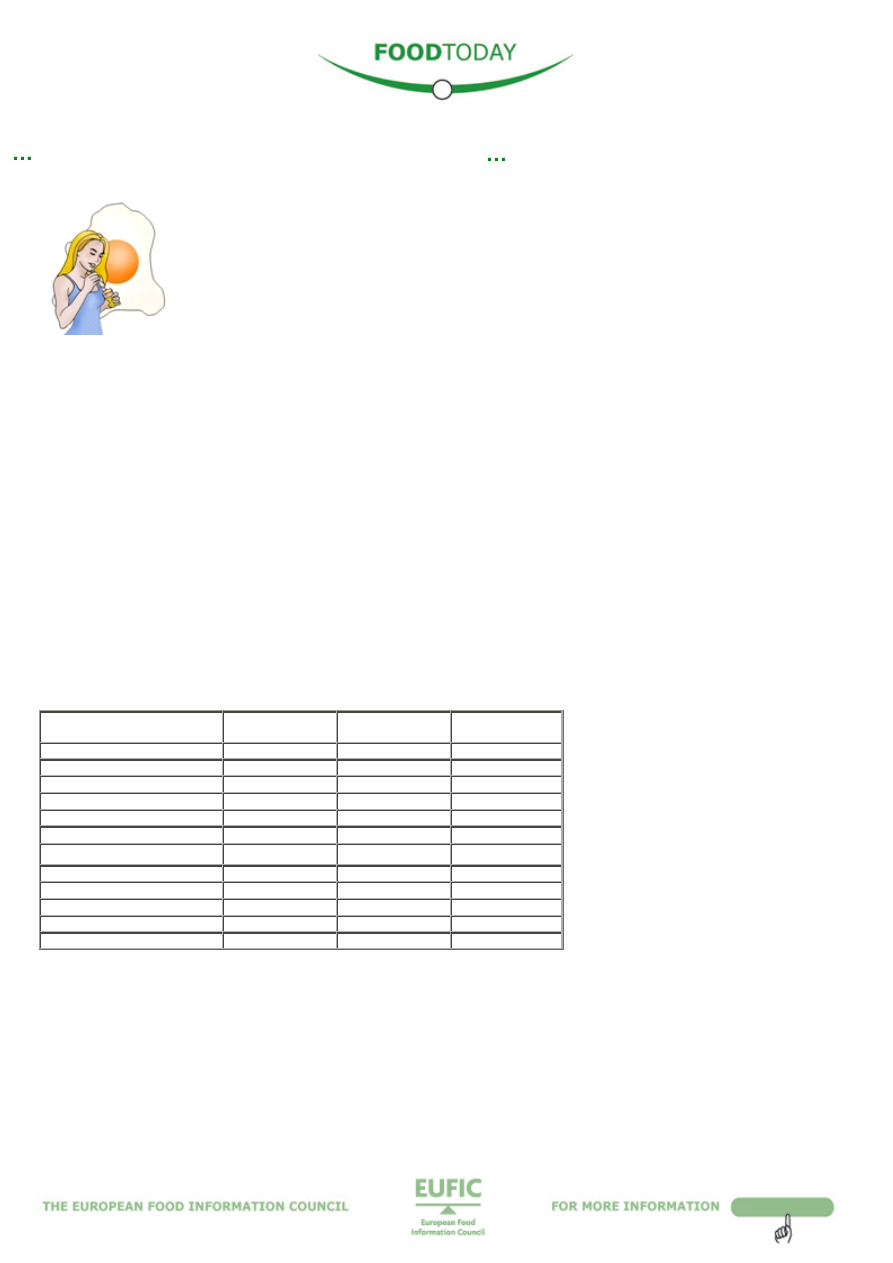

An average chicken egg weighs around 60 grams and is composed of 11% shell, 58% white and 31% yolk.

7

Egg whites are

mainly water (88%) and protein (9%), whereas egg yolks are mainly water (51%), fat (31%) and protein (16%).

7

Key

nutrients found in eggs (Table 1), such as vitamin D, vitamin B

12

, folate, and selenium have been associated with the

prevention of chronic conditions, such as heart disease, raised blood pressure, cognitive decline and birth defects. A UK survey

found that adults who consumed three or more eggs per week had significantly higher intakes of vitamins B

12

, A and D, niacin

(vitamin B

3

), iodine, zinc and magnesium, compared with nonconsumers.

8

The relatively high vitamin D content of eggs is

noteworthy since few foods are recognised vitamin D sources. Overall, the nutrient composition of eggs can be modified

through the feed provided to the chickens. This is the case, for example, with eggs with an enhanced content of

docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), an omega3 polyunsaturated fatty acid important for brain development, normal vision, heart

health and certain other bodily functions.

9,10

Table 1 Major nutrients in raw chicken eggs

Source

7

,

a

sum of niacin (mg) plus tryptophan (mg) divided by 60

Food safety issues

Eggs can contain Salmonella, a bacterium linked with food poisoning outbreaks. In 2008, the European Union saw 131,468

confirmed human cases of infection with Salmonella (salmonellosis) from all sources , which corresponds to less than 1 in 3000

individuals.

11

A 2007 report by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) collated information about Salmonella found in egg

laying farms from 23 European countries.

12

While the average figure for the detection of Salmonella species relevant to public

health was 20%, figures ranged from 8% to more than 60% in major eggproducing countries. Since then, industry action,

including the introduction of standards, flock vaccination, and improved poultry welfare across Europe have been instrumental in

helping to bring about large reductions in Salmonella contamination.

The way that eggs are stored and used in the home also influences food safety. Traces of Salmonella can be found on egg shells,

thus hand washing is essential after handling eggs to prevent any microorganisms being transferred to cooked food. However,

egg shells should not be washed as they are covered by a protective layer, the cuticle or bloom, which prevents bacteria from

entering through pores in the shell.

13

If the eggs are soiled and therefore need to be washed, immediate use is recommended.

14

Broken eggs and eggshells should be disposed of immediately and not retained in the same tray as unbroken eggs.

Eggs revisited nutritious and safe to eat

Whole egg

per 100 g

Egg white

(per 100 g)

Egg yolk

(per 100 g)

Water (g)

75.1

88.3

51.0

Protein (g)

12.5

9.0

16.1

Fat (g)

11.2

Traces

30.5

Vitamin A (µg)

190

0

535

Vitamin D (µg)

1.8

0

4.9

Niacin equivalents (mg)

a

3.8

2.7

4.8

Vitamin B

12

(µg)

2.5

0.1

6.9

Folate (µg)

50

13

130

Selenium (µg)

11

6

20

Zinc (mg)

1.3

0.1

3.1

Iodine (µg)

53

3

140

Magnesium (mg)

12

11

15

3

Keeping eggs refrigerated throughout the food chain reduces growth of Salmonella, but whether it further lowers the risk of human

salmonellosis remains to be evaluated.

15

It seems important that repeated changes in storage temperature be avoided as they

might lead to water condensation on the shell, which in turn could promote bacterial growth and penetration into the egg.

Since Salmonella is killed by heat, proper cooking, i.e. a minimum temperature of 70°C in all parts of the food, further adds to

eggs being safe to eat.

14

For vulnerable groups, such as the frail elderly, the sick, infants, small children and pregnant women,

eggs and egg dishes must always be cooked thoroughly. The World Health Organization (WHO) discourages the consumption of

foods containing raw or undercooked eggs, examples of which are mayonnaise, hollandaise sauce, icecream or certain desserts

such as mousses, particularly if prepared at home and from unpasteurised eggs.

14

It is strongly advised to clean and disinfect

surfaces after whisking raw egg mixtures and to ensure that uncovered readytoeat foods are not standing close by during

whisking.

Food safety advice commonly includes using pasteurised egg products rather than raw shell eggs. Special hygiene requirements

for manufacturing egg products are laid down in the respective regulation by the European Commission.

16

Conclusions

Eggs can make a valuable contribution to a healthy, balanced diet in that they provide high quality protein and a number of

vitamins and minerals. In Europe, measures are constantly being improved to ensure farming and processing practices result in

eggs and eggcontaining foods that are safe to eat. Combined with consumers adhering to a few food safety guidelines in the

home, these make for a safe and nutritious addition to the menu. Overall, the negligible food safety risk posed by eggs is far

outweighed by their contribution to healthy diets for all age groups.

References

1. Hu FB et al. (1999). A prospective study of egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease in men and women.

Journal of the American Medical Association 281:13871394.

2. Song WO & Kerver JM. (2000). Nutritional contribution of eggs to American diets. Journal of the American College of

Nutrition 19:556S562S.

3. Vander Wal JS et al. (2005). Shortterm effect of eggs on satiety in overweight and obese subjects. Journal of the

American College of Nutrition 24:510515.

4. Ratliff J et al. (2010). Consuming eggs for breakfast influences plasma glucose and ghrelin, while reducing energy

intake during the next 24 hours in adult men. Nutrition Research 30(2):96103.

5. Vander Wal JS et al. (2008). Egg breakfast enhances weight loss. International Journal of Obesity 32:15451551.

6. Wenzel AJ et al. (2006). A 12wk egg intervention increases serum zeaxanthin and macular pigment optical density in

women. The Journal of Nutrition 136:25682573.

7. Food Standards Agency (2002). McCance and Widdowsons’s The Composition of Foods, 6th summary edition.

Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry.

8. Ruxton CHS et al. (2010). Nutritional and health benefits of consuming eggs. Nutrition & Food Science 40:263279.

9. European Food Safety Authority (2010). Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to

docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and maintenance of normal (fasting) blood concentrations of triglycerides (ID 533, 691,

3150), protection of blood lipids from oxidative damage (ID 630), contribution to the maintenance or achievement of a

normal body weight (ID 629), brain, eye and nerve development (ID 627, 689, 704, 742, 3148, 3151), maintenance of

normal brain function (ID 565, 626, 631, 689, 690, 704, 742, 3148, 3151), maintenance of normal vision (ID 627, 632,

743, 3149) and maintenance of normal spermatozoa motility (ID 628) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No

1924/20061. EFSA Journal 2010;8(10):1734

10. European Food Safety Authority (2010). Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to

eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) and maintenance of normal

cardiac function (ID 504, 506, 516, 527, 538, 703, 1128, 1317, 1324, 1325), maintenance of normal blood glucose

concentrations (ID 566), maintenance of normal blood pressure (ID 506, 516, 703, 1317, 1324), maintenance of normal

blood HDLcholesterol concentrations (ID 506), maintenance of normal (fasting) blood concentrations of triglycerides

(ID 506, 527, 538, 1317, 1324, 1325), maintenance of normal blood LDLcholesterol concentrations (ID 527, 538, 1317,

1325, 4689), protection of the skin from photooxidative (UVinduced) damage (ID 530), improved absorption of EPA

and DHA (ID 522, 523), contribution to the normal function of the immune system by decreasing the levels of

eicosanoids, arachidonic acidderived mediators and proinflammatory cytokines (ID 520, 2914), and

“immunomodulating agent” (4690) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA Journal 2010;8

(10):1796

11. European Food Safety Authority (2009). The Community Summary Report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic

agents and foodborne outbreaks in the European Union in 2008. Available at:

http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/scdocs/scdoc/1496.htm

12. European Food Safety Authority (2007). Report of the Task Force on Zoonoses Data Collection on the Analysis of the

Baseline Study on the Prevalence of Salmonella in Holdings of Laying Hen Flocks of Gallus gallus. Available at:

http://www.efsa.europa.eu/EFSA/Report/zoon_report_ej97_finlayinghens_summary_en,0.pdf

13. Food Science. 5th revised edition. Ed. NN Potter, JH Hotchkiss. Chapman & Hall, New York, 1995.

14. WHO website, Food Safety Section. Food safety measures for eggs and foods containing eggs. Available at:

http://www.who.int/entity/foodsafety/publications/consumer/en/eggs.pdf

15. European Food Safety Authority (2009). Special measures to reduce the risk for consumers through Salmonella in table

eggs – e.g. cooling of table eggs. Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Biological Hazards. The EFSA Journal 957:129.

16. Corrigendum to Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 laying

down specific hygiene rules for food of animal origin. Official Journal of the European Union L 226 of 25 June 2004.

Available at:

http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2004:226:0022:0082:EN:PDF

4

Public health interventions aim to reduce the burden of disease and increase the quality of life of

populations. But which are the most pressing health problems? Which interventions are most likely

to be successful? Do they provide good value for money? Two metrics abbreviated as QALY and

DALY, can aid such assessments.

Introduction

Average life expectancy has increased but are these additional years healthy, productive and enjoyable? To evaluate and

compare, health interventions undergo costeffectiveness analysis to measure the impact on both the length and the quality of

life. QALYs (QualityAdjusted Life Year) and DALYs (DisabilityAdjusted Life Year) are common terms used within this

framework. QALYs are a measure of years lived in perfect health gained whereas DALYs are a measure of years in perfect

health lost. They are the most frequently cited metrics for riskbenefit assessment.

QualityAdjusted Life Year (QALY)

The QALY was invented in the 1970’s and has become an internationally recognised standard tool since the mid1990s.

1

A

QALY is the arithmetic product of life expectancy combined with a measure of the quality of lifeyears remaining. The

calculation is relatively straightforward; the time a person is likely to spend in a particular state of health is weighted by a

utility score from standard valuations. In such valuation systems, ‘1’ equates perfect health and ‘0’ equates death. Since

certain health states that are characterised by severe disability and pain are regarded as worse than death, they are assigned

negative values.

2

If an intervention provided perfect health for one additional year, it would produce one QALY. Likewise, an intervention

providing an extra two years of life at a health status of 0.5 would equal one QALY. This effect is related to cost; cost per

QALY. For example, if a new treatment gave an additional 0.5 QALYs and the cost of the new treatment per patient is a5,000

then cost per QALY would be a10,000 (5,000/0.5).

2

DisabilityAdjusted Life Year (DALY)

The DALY is an alternative tool which emerged in the early 90s, as a means of quantifying the burden of disease. DALYs sum

years of life lost (YLL) due to premature mortality and years lived in disability/disease (YLD).

1

YLL are calculated as the number of deaths at each age multiplied by the standard life expectancy for each age. YLD represent

the number of disease/disability cases in a period multiplied by the average duration of disease/disability and weighted by a

disease/disability factor. As an example, a woman with a standard life expectancy of 82.5 years and dying at age 50 would

suffer 32.5 YLL. If she additionally turned blind at aged 45, this would add 5 years spent in a disability state with a weight

factor of 0.33, resulting in 0.33 x 5 = 1.65 YLD. In total, this would amount to 34.15 DALYs.

For DALYs, the scale used to measure health state is inverted to a ‘severity scale’, whereby ‘0’ equates perfect health and ‘1’

equates death. The weight factors are ageadjusted to reflect social preference towards life years of a young adult (over an

older adult or young child). Furthermore, they are discounted with time, thus favouring immediate over future health benefits.

3

It is important to understand the differences between QALYs and DALYs, they are not interchangeable. The two measures can

produce different results dependent on age at onset and duration of disease, and whether age and disability are weighted.

Limitations of DALYs and QALYs

QALYs and the DALYs can be applied to a wide range of diseases and interventions in different population settings, however

both face criticisms. Neither measure fully captures the wider effects that stem from interventions: emotional and mental

health, impact on carers and family, or nonhealth effects such as economic and social consequences (e.g. loss of work).

1,4

QALYs can lack sensitivity and may be difficult to apply to chronic disease and preventative treatment. The derivation of ‘health

state utilities’, i.e. defining weighting factors for specific health states, is subjective and controversial. Diseasespecific

measures may be used, but must be interpreted with caution.

2

Similarly, standard life expectancy figures may overestimate

DALYs saved when actual (local) life expectancy is shorter.

1

Lastly, social preference weighting and discounting of DALYs present certain ethical issues: are young adults and nondisabled

more productive and valuable to society? Does the value of health decrease over time?

Conclusion

QALYs and DALYs are tools, providing a single measure of mortality and morbidity, used internationally for assessing health

care interventions and treatments. Their application in the realm of Public Health enables policy makers to make informed

decisions, and countries to choose vital, costeffective health solutions.

1

References

1. Sassi F. (2006). Calculating QALYs, comparing QALY and DALY calculations. Health Policy Plan 21(5):402408.

2. Phillips C, Thompson G. (2009). Health economics (2nd edition):

http://www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/painres/download/whatis/QALY.pdf

3. World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Disease concept. Available at:

http://www.who.int/quantifying_ehimpacts/publications/en/9241546204chap3.pdf

4. Anand S, Hanson K. (1997). Disabilityadjusted life years: A critical review. J Health Econ 16:685702.

Measuring burden of disease the concept of QALYs and DALYs

5

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

FOOD TODAY #62 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #71 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #90 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #64 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #66 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #75 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #80 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #73 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #91 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #86 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #83 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #69 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #70 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #74 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #56 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #84 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #67 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #63 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #79 EUFIC

więcej podobnych podstron