Following the political fallout and damage to consumer confidence and

the food industry caused by the BSE (Bovine Spongiform

Encephalopathy) known as “mad cow disease” crisis of the 1990s, the

EU embarked on a major reform of its policy and regulation in relation to

food safety. Food traceability is the cornerstone of that reform.

What

are

food

traceability

and

product

withdrawal/recall?

Traceability is the ability to track any food, feed, foodproducing animal or

substance that will be used for consumption through all stages of production,

processing and distribution.

1

In the event of a food incident it enables the

identification and subsequent withdrawal or recall of unsafe food from the

market. If the food has not reached the consumer, a trade withdrawal is

undertaken. If the food has reached the consumer, a product recall is

undertaken which includes notification of the consumer through instore notices

and press releases.

Why are traceability and product withdrawal/recall

important?

Traceability and product recall are important as they enable food businesses to

respond quickly to food safety/quality incidents thereby ensuring that consumer exposure to the affected product is prevented

or minimised. A good traceability system ensures that withdrawals/recalls are limited to implicated products, thereby

minimising disruption to trade and company finances.

The recent issues surrounding the undeclared substitution of horse meat in beef products has highlighted the importance of

traceability systems in identifying the source of fraudulent activities. This is essential to ensure that these activities, which are

undertaken by a minority, do not undermine consumer protection, consumer confidence and the integrity of the majority of the

food chain.

What are the legislative requirements?

Regulation 178/2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, requires every food and feed business

in Europe and those bringing food/feed into Europe to have a traceability and recall system in place.

1

All food and feed businesses must be able to identify where their raw materials (e.g. ingredients and packaging) come from

and where their products are going or have gone to, i.e. they must be able to identify one step back and one step forward in

the food chain. The latter however, is not applicable to businesses selling directly to the final consumer.

1

Additionally, there are also legal requirements to keep records, apply traceability information to product and/or documents and

provide this information to the competent authority on demand. Further sectorspecific legislation applies to certain foods

including fruit and vegetables, sprouted seeds, beef, fish, honey, olive oil, genetically modified organisms and live animals.

14

There is no legal requirement to implement internal traceability which tracks food ingredients and products as they move

through the manufacturing process.

1

However, in many instances the food industry have implemented internal traceability to

ensure the integrity of their overall traceability systems.

Development of traceability systems

The type of food traceability system implemented may vary from business to business; however, the overall aim is to

incorporate both legal and voluntary requirements (i.e. internal traceability).

These systems can be as simple as recording the batch codes of ingredients at each stage of production or as sophisticated as

computerised barcoding to track and control the movement of ingredients and finished goods. Many companies in the food

industry have developed such systems and use best practice or voluntary standards such as ISO 22005:2007 to deliver and

enhance on the minimum requirements for traceability and recall.

Moving forward

Systems of traceability and recall continue to develop and improve with advances in technology such as barcoding, radio

frequency identification, global data synchronisation and authenticity testing of foods. Coupled with improving technology is a

continuing process of amending and strengthening legislation in relation to food safety controls. This will allow both the

authorities and the food industry to quickly identify and isolate unsafe foodstuffs and minimise consumer exposure to future

food incidents.

1,5

References:

1.

2.

European Commission (2007). Food Traceability Fact Sheet.

Food traceability: cornerstone of EU food safety policy

3.

Regulation (EU) No 209/2013 of March 2013 amending Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 as regards

microbiological criteria for sprouts and the sampling rules for fresh poultry meat.

4.

Regulation (EU) No 931/2011 of 19 September 2011 on the traceability requirements set by Regulation

(EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council for food of animal origin.

5.

European Commission Q&A on Horsemeat.

2

There is an increasing variety of vegetable oils for cooking and food preparation. How do you decide which one to use?

Considerations include taste, functional properties of the oil, cost, and the health impact. Here is some explanation on oils, as well

as guidance on choosing them according to purpose.

What is in a vegetable oil?

Vegetable oils, also known as plant oils, are derived from seeds, legumes, nuts and some fruits. Basically, vegetable oils are fats that are liquid at

room temperature. All

are made up of triglycerides, which are comprised of fatty acids attached to glycerol. Vegetable oils contain a mix of

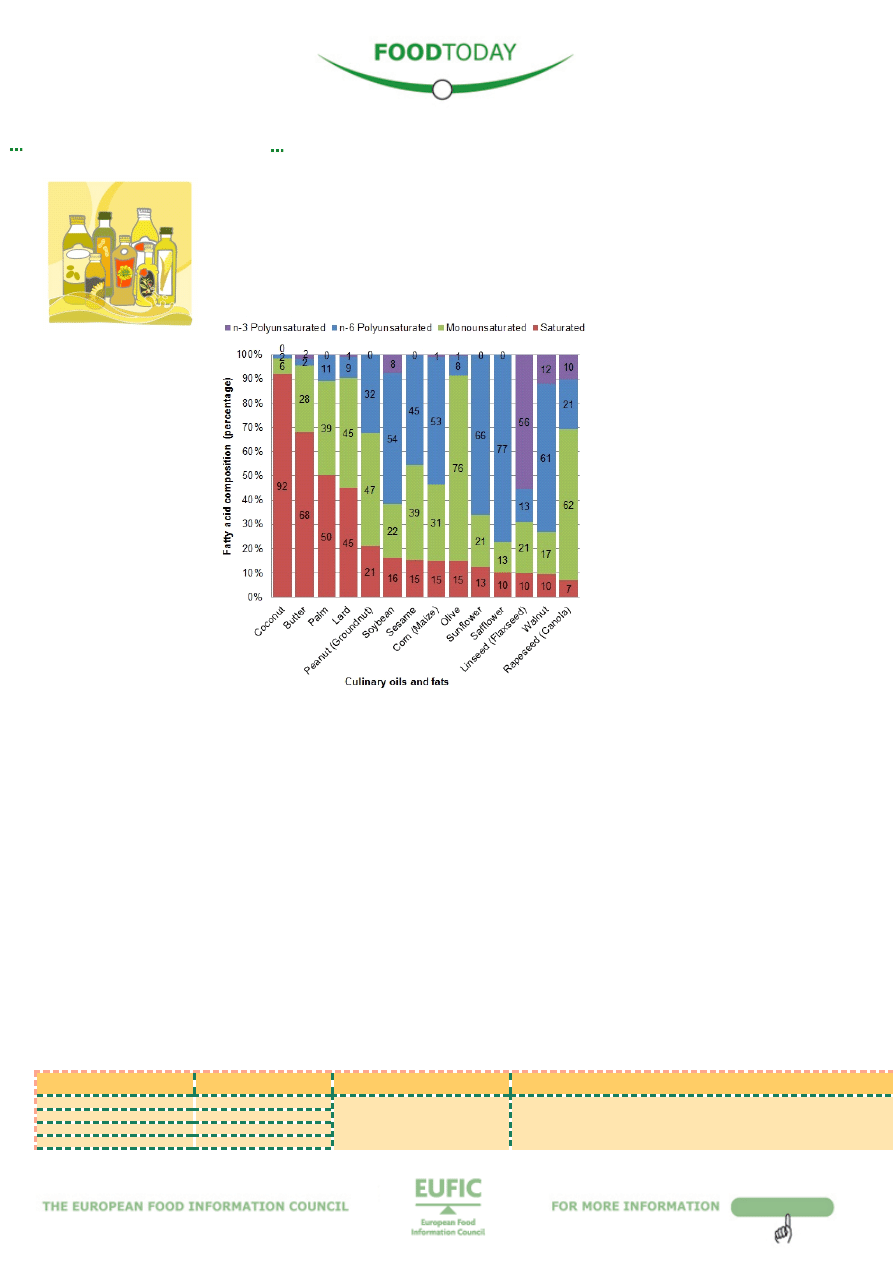

saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, although unsaturated fatty acids (mono and poly) typically predominate (see

Figure 1). In contrast, in animal fats like butter and lard, saturated fatty acids predominate and they are solid at room temperature. There are

also a few plant oils, such as palm oil and coconut oil, which are relatively high in saturated fatty acids and consequently more solid.

Unsaturated fatty acids that vegetable oils are rich in have beneficial effects on markers of cardiovascular health, when used in place of saturated

fatty acids.

1

Olive oils contain mainly monounsaturated fatty acids, and rapeseed oils are a mixture of mono and polyunsaturated fatty acids

(including omega3 fatty acids), whereas sunflower, corn and walnut oils contain mostly polyunsaturated fatty acids. The polyunsaturated fatty

acids in oils may include the omega6 (n6) fatty acid linoleic acid and the omega3 fatty acid (n3) alphalinolenic acid.

Figure 1. Common fatty acid composition of major culinary oils, and butter and lard for comparison

2,3

; this may vary between products.

Vegetable oils may contain fatsoluble vitamins including vitamin E and vitamin K. Oils may also contain varying amounts of beneficial bioactive compounds, such as the antioxidant

polyphenols in virgin and extra virgin olive oil. In addition, plant oils are a natural source of sterols, which are preferentially absorbed by the human body in place of dietary cholesterol

(thereby blocking its absorption).

Refined and unrefined oils

Vegetable oils of the same type can have different levels of refining. Oils are refined to remove any unwanted taste, smell, colour or impurities. The extent of refining will depend on the

desired usage (for example taste, appearance, or oil stability (see ‘cooking with oils’)). Unrefined oils retain beneficial plant bioactives.

2

For example, nonrefined oils like ‘virgin’ olive oil

and ‘extra virgin’ olive oil are likely to contain more antioxidant polyphenols than refined olive oil. Extra virgin oils are used especially where the olive taste is needed. It is used for

flavouring rather than as a cooking oil.

Cooking with oils

During cooking, oils serve as a medium to transfer heat, but they also gets absorbed by the food. During the cooking process, oils also absorb fat soluble flavour compounds, which

contribute to the taste of food. Foods that have been fried, or oven baked with oil, have a crisp texture and a golden appearance.

Oils should be treated with care. Fatty acids are sensitive to heat, light and oxygen, and overexposure to these during storage or cooking can change the chemical structure of the fatty

acids. This can produce ‘off’ flavours and lead to the destruction of vitamins and loss of nutritional value.

1

Stability of the fatty acids varies between oils.

1

Heat stability is indicated by the ‘smoke point’ the temperature at which decomposition becomes visible as bluish smoke. If the cooking

temperature is too high, the oil will eventually degrade. Generally, the longer it is heated, the more it will deteriorate. On the other hand, if the temperature is too low, cooking time is

extended and more oil will be absorbed. In general, refined oils have higher stability and smoke point.

It is also important to note that the higher the level of unsaturation of the fatty acids, the lower the heat stability of the oil.

1

Refined monounsaturatedrich oils, such as refined, nonvirgin

olive oil, peanut oil, as well as high oleic rapeseed and sunflower oils, are therefore more stable, and can be reused to a greater extent than polyunsaturatedrich oils, such as corn oil and

regular sunflower.

Repeated use of oil, typical for deepfrying, reduces the temperature at which the smoke point occurs, though this effect is much less marked in stable oils such as high oleic rapeseed and

high oleic sunflower oils. If vegetable oils are to be used repeatedly, they should be filtered after frying (when cold), to remove particles. The frying vessel must be carefully cleaned and

fully dried. In practice, oils can be used a few times as long as the sensory characteristics are good. It is generally advised to totally renew the oil after 10 frying cycles.

A recent study indicated that oils and margarines that are rich in essential polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs omega 3 and 6) are also suitable for shallow (pan) frying and baking, with

95% of the PUFAs retained.

4

Margarines are emulsions of plant oils and water (up to 16%).

5

Solid margarines cannot be used safely for hightemperature frying, since water that they

contain causes spattering. However, high fat margarines (i.e. with a fat content above 60%) can be used for shallow frying and sautéing. A relatively new option is bottled liquid

margarines, designed for cooking. They have higher amounts of healthy unsaturated fatty acids than solid ones, and have been developed to have good frying properties, such as even

browning and reduced spattering. With liquid margarines, as with solid margarines and butter, a suitable cooking temperature is attained when the large air bubbles disappear and the

colour becomes transparent.

Which oil to choose

The choice of oil will depend on cost, taste, and purpose. The table below gives a guide.

Table 1. Predominant fatty acid families and recommended uses of common vegetable oils*

How to choose your culinary oil

Oil

Type of fat (predominant

fatty acids)

Qualities

Ideal for

Sunflower

Polyunsaturated

Clear, light coloured with a bland

taste.

Allpurpose oils. Salad dressings and cooking, including multipurpose frying (stir

frying, sautéing, deepfrying). Possibility of repeated use depends on the fried

Corn (maize)

Polyunsaturated

Safflower

Polyunsaturated

Soybean

Polyunsaturated

3

dressings and sautéing, and choose heatstable oils for deep frying and refined oils for baking. To prevent rancidity and offflavours, store oils in a dark, cool, dry place and use within the

defined shelf life of the oil.

2

Remember: all oils are caloriedense, and should be used sparingly. But don’t forget to enjoy your culinary oils!

For more information

•

EUFIC review (2010). The Why, How and Consequences of cooking our food

(explains types of cooking methods and includes smoke points of different fats and oils)

• Tuorila H, Recchia A. Sensory perception and other factors affecting consumer choice of olive oil. In Olive Oil Sensory Science, eds E Monteleone, S Langstaff, WileyBlackwell, Oxford (in

press)

References

1.

(to be updated 2014)

2. Foster R, Williamson CS & Lunn J (2009). BRIEFING PAPER: Culinary oils and their health effects. Nutrition Bulletin 34: 4–47.

3. National Food Institute. Danish Food Composition Database, version 7.01, March 2009

4. Hrncirik K & Zeelenberg M (2013). Stability of essential fatty acids and formation of nutritionally undesirable compounds in baking and shallow frying. Journal of the American Oil

Chemists' Society DOI 10.1007/s1174601324012.

5.

Codex Standard for Margarine (CODEX STAN 321981)

Temperature stability varies.

product, frying time and frying temperature.

Peanut (Groundnut)

Monounsaturated (and 30%

polyunsaturated)

Rapeseed (Canola)

Monounsaturated (and 30%

polyunsaturated)

High oleic (omega9) versions

of

Rapeseed,

Sunflower,

Safflower

Monounsaturated

High heat stability.

Multipurpose frying. Cooking at high temperatures.

Repeated frying (frequent with deep frying).

Mayonnaise and salad dressings.

Cold pressed oils Extra virgin

olive oil/Extra virgin rapeseed

Monounsaturated

Cloudy with a green/amber hue,

distinctive taste, typically more

expensive.

Salad dressings, sautéing, and drizzling.

Virgin olive

Monounsaturated

Distinctive taste.

Dressings, sautéing, simmering.

Regular and light refined olive

Monounsaturated

Clear, light coloured, high heat

stability.

Cooking at high temperatures.

Linseed (Flaxseed)

Polyunsaturated

Heat sensitive.

Salad dressings and drizzling.

Walnut

Polyunsaturated

Distinctive taste, typically more

expensive.

Refined varieties are heat stable.

Salad dressings, drizzling.

Stir frying (refined varieties)

Sesame

Monounsaturated (and 40%

polyunsaturated)

Hazelnut

Monounsaturated

Palm

Saturated

Reddish colour, semisolid, long

shelflife.

Commercial frying and baking.

Coconut

Saturated

Semisolid, long shelflife.

Commercial frying.

4

Fructose has undergone a lot of scrutiny recently regarding its impact on metabolic

indicators of health. We looked at how fructose is metabolised and the current

evidence of how this affects health.

What is fructose and where does it come from?

Fructose is the main naturally found sugar in honey and fruits (e.g. dates,

raisins, figs, apples, and fruit juices) and in small amounts in some vegetables

(e.g. carrots). Fructose is also bound to glucose in table sugar (sucrose) which

is half (50%) fructose and half (50%) glucose. Table sugar is used at home, ‘at

the table’ and for cooking and baking, and is used as a sweetening agent in the

manufacturing of foods and nonalcoholic beverages. Another source of fructose

is

, which are made from maize and wheat and

used as sweeteners in a variety of foods such as jams, preserves and

confectionary. The fructose content can range from 5% to 50%. If the fructose

makes up more than 50% of the syrup, the name on the ingredient listing

should read “FructoseGlucose Syrup”. Fructose provides the same caloric

energy per gram as any other sugar or digestible carbohydrate, i.e. 4 kcal/g.

Fructose metabolism

Ingested fructose is metabolised in the liver to produce mainly glucose (~50%),

and minor amounts of glycogen (>17%), lactate (~25%) and the small

remainder to fatty acids; the latter via a process called de novo lipogenesis.

1

Glucose travels through the bloodstream to all the tissues, and cells transform

glucose into energy. Lactate and fatty acids are also energy sources.

In comparison to glucose, fructose provides a lower glycaemic response, as it has a very low

.

Therefore, the consumption of foods in which fructose, replaces glucose, sucrose, or starches, leads to a lower blood glucose

rise compared to foods containing only glucose and sucrose. A reduced glycaemic response may be beneficial to people with

impaired glucose tolerance (high glucose levels).

2

Blood glucose fluctuations are also influenced by the chemical and physical

nature of foods/drinks consumed, and by individual factors.

Some studies show, however, that high intakes of fructose may lead to metabolic disturbances. Many of these studies are done

in animals, or are shortterm overfeeding trials in humans, with levels of fructose much higher than normally consumed (for

example 100150 g pure fructose/day). This approach called hyperdosing provides energy above normal needs. For example,

a recent study found that 7day overfeeding with high levels of either fructose, glucose, or saturated fat, all increased fat in the

liver to the same extent, and that both fructose and glucose overfeeding decreased liver insulin sensitivity (making the liver

less sensitive to insulin).

3

Many shortterm overfeeding trials have also shown that fructose can raise triglycerides (fats in the

blood), within the normal range in healthy people.

4,5

When fructose replaces other carbohydrates (containing similar levels of

energy), it does not appear to cause more weight gain than the other carbohydrates, adversely affect blood pressure, or raise

blood triglycerides.

68

These effects, may therefore not be unique to fructose and may in fact be due to excess energy intake.

9

Increased dietary intake from any energy source above energy needs will eventually lead to weight gain, unless balanced by

increased physical activity. Obesity, particularly excess abdominal fat, is clearly associated with metabolic disease.

Interestingly, the effect of very high fructose intake on blood fat levels was not seen in a study in healthy young men that

cycled two times 30minutes a day, which highlights the benefits of exercise.

10

Studies on fructose typically use pure fructose, rather than in combination with glucose as would be ingested within a food or

beverage. Further research is clearly needed to determine the consequence of high dietary fructose intake in humans, in the

longterm, and the differences between individuals and between different population groups, i.e. overweight/obese.

4

Fructose and athletes

Sport drinks are designed to support athletic performance by replacing fluids, salt and carbohydrates lost during physical

activity of high intensity or long duration. High concentrations of fructose are slowly absorbed, resulting in reduced plasma

volume, and higher occurrence of gastrointestinal distress. However, fructose ingested in small amounts in combination with

sucrose and/or glucose does not delay fluid absorption.

11

Solutions that contain both glucose and fructose appear to improve

sodium and fluid absorption better than those containing either glucose or fructose alone.

11,12

The combination of glucose and

fructose also increases fructose uptake by the body.

12

It has been shown that when athletes consume fructose and glucose in

combination, energy is released at relatively high rates and thus beneficial effects on exercise performance and reduced

fatigue were observed.

13

Athletes often have a higher than normal fructose intake but tend to have less metabolic and

cardiovascular disease than sedentary individuals.

4

Metabolic health advice

There is currently little evidence that fructose itself causes metabolic diseases when consumed in amounts consistent with

current average dietary habits in Europe.

4

There is need for a better understanding of the factors, such as genetics, which may

regulate the effect of high fructose intake on health. To protect metabolic health, avoiding excessive energy intake, engaging

in regular physical activity, maintaining a healthy body weight and eating a healthy, varied diet is still the best advice. Also do

not hesitate to ask your doctor or healthcare professional for precise advice that fits your personal health condition.

References

1. Tappy L & Le KA (2010). Metabolic effects of fructose and the worldwide increase in obesity. Physiol Rev 90:2346.

2.

related to fructose and reduction of postprandial glycaemic responses. EFSA Journal 9(6):2223.

3. Lecoultre V, Egli L, Carrel G, et al. (2013). Effects of fructose and glucose overfeeding on hepatic insulin sensitivity and

intrahepatic lipids in healthy humans. Obesity 21(4):782785.

4.

Tappy L (2012). Q&A ‘Toxic’ effects of sugar: should we be afraid of fructose. BMC Biology. 10:4.

5. Silbernagel G, Machann J, Unmuth S, et al. (2011). Effects of 4week veryhighfructose/glucose diets on insulin

sensitivity, visceral fat and intrahepatic lipids: an exploratory trial. British Journal of Nutrition 106(1):7986.

Fructose and metabolic health

5

6. Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ, Mirrahimi A, et al. (2012). Effect of fructose on body weight in controlled feeding trials: a

systematic review and metaanalysis. Annals of Internal Medicine 156(4):291304.

7. Ha V, Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ, et al. (2012). Effect of fructose on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta

analysis of controlled feeding trials. Hypertension 59:787795.

8. Wang DD, Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ et al. (2014). Effect of fructose on postprandial triglycerides: A systematic

review and metaanalysis of controlled feeding trials. Atherosclerosis 232(1):125133.

9. Johnston RD, Stephenson MC, Crossland H, et al. (2013). No difference between highfructose and highglucose diets on

liver triacylglycerol. Gastroenterology 145(5):10161025.e2. Doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.012.

10. Egli L, lecoultre V, Thevtaz F, et al. (2013). Exercise prevents fructoseinduced hypertriglyceridemia in healthy young

subjects. Diabetes 62(7):22592265.

11. Currell K & Jeukendrup AE (2008). Superior endurance performance with ingestion of multiple transportable

carbohydrates. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 40(2):275281.

12. Johnson RJ & Murray R (2010). Fructose, exercise and health. Current Sports Medicine Reports 9(4):253258.

13. Jeukendrup AE (2013). Multiple transportable carbohydrates and their benefits. Sports Science Exchange 26(108):15.

6

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

FOOD TODAY #62 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #77 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #71 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #90 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #64 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #66 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #75 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #80 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #73 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #86 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #83 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #69 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #70 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #74 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #56 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #84 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #67 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #63 EUFIC

FOOD TODAY #79 EUFIC

więcej podobnych podstron